Nava Atlas's Blog, page 43

April 4, 2021

The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë by Daphne du Maurier

The three Brontë sisters — Charlotte, Emily, and Anne — cherished literary ambitions from an early age, and despite lives cut short by illness, earned a prominent place in the English literary canon. The same can’t be said for their brother, Branwell Brontë (1817 – 1848), whose dissipated life ended at age thirty-one, with little to show for his early talent other than thwarted ambition.

The children of Maria Branwell Brontë and Reverend Patrick Brontë, the Brontë siblings grew up in Haworth, England, located in Yorkshire. Maria Branwell Brontë died while the children were still very young, and the two oldest sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, died of illness before reaching adolescence.

The three surviving sisters and Branwell with primarily one another for company, put on plays, told stories, and created journals and magazines about the make-believe realm. Branwell was very much the ringleader. In their teens, they created an imaginary world called Angria.

Branwell’s poetry and drawings display an incipient talent that was never fully developed. With one failure after another as he entered young adulthood, his his promise faded, and he descended into the world of addiction and dissipation.

. . . . . . . . .

Self-portrait by Branwell Brontë, ca.1840 (The Brontë Society)

. . . . . . . . .

“It’s Time to Bring Branwell, the Dark Brontë, into Light” a 2017 article in The Guardian, looked to bring more clarity into this shadowy figure, in the year of his 200th birthday:

“Although his influence was not always positive, Branwell remained a primary muse for his sisters, and we should remember him as a major cog in the Brontë writing machine – even if his own work was always ‘minor.’ And the story of a young, talented fantasist failing to make his way in the world resonates with our experiences of hardship and lost dreams.”

Enter Daphne du Maurier

There is still no full-scale biography of Branwell Brontë, so Daphne du Maurier’s The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë (1960) remains the only serious study of his brief and difficult life.

Du Maurier is best remembered for the half a dozen or so books and stories that were adapted to film, notably, Rebecca, My Cousin Rachel, Jamaica Inn, and others. Her publishing credits went well beyond her more famous works to include nearly forty novels, short story collections, nonfiction works, and plays.

It’s no secret that du Maurier was inspired by the Brontë sisters, — Rebecca, in particular, pays homage to Jane Eyre. It’s fitting, then, that among her nonfiction titles is The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë (1960), a portrait of the troubled brother of the literary sisters that she so admired.

Chapter one of The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë begins:

He died on Sunday morning, the 24th of September, 1848. He was thirty-one years old. He died in the room which he had shared with his father for so long, and in which, as a little boy, he had awakened to find the moon shining through the curtainless windows and his father upon his knees, praying.

The room, for too many months now, had been part refuge and part prison-cell. It had been refuge from the accusing or indifferent eyes of his sisters, refuge from the averted gaze of his father … Eternal reproach, eternal accusation.

“I know only that it is time for me to be something when I am nothing. That my father cannot have long to live, and that when he dies my evening, which is already twilight, will become night. That I shall then have a constitution still so strong that art will keep me years in torture and despair when I should every hour era that I might die.” (Branwell, from a letter to a friend, a year or two before his death)

The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë in brief

From the original 1960 edition (Doubleday and Company):

Branwell Brontë, brother of the celebrated Charlotte, Emily, and Anne, as a child showed the most promise of all the Brontë’s — precocious and exceptionally brilliant, it was his imagination and wild unfettered spirit that led the others. He was worshipped by his sisters and widowed father, and it was Branwell that they all looked for literary success.

And yet, Branwell was the only one who was unable to bridge the gap from childhood fantasy to adulthood, the only one who did not produce a finished, mature book. Daphne du Maurier has written a full-length portrait of the mysterious, elusive Branwell Brontë and of the infernal world of his inner torment which killed him a the age of thirty-one from excessive laudanum and alcohol.

As a child, Branwell fed the willing imaginations of his sisters with the wild, fantastic stories of his mythical, self-invented Kingdom of Angria. There is no question that he was a great influence on the writings of his sisters and that Emily drew on her brother for her portrait of Hindley Earnshaw in Wuthering Heights, as did Anne, for Arthur Huntington in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

Failing to be admitted to the Royal Academy of Art when he was eighteen, Branwell turned to alcohol and a life of dissipation which he followed fitfully until his life ended in bitterness and despair, conscious of his sisters’ growing success and of his own monumental failure. Haunted by illness and disappointment most of his life, Branwell preferred the wild and joyous world of his own imagination to the world of harsh reality and responsibility.

Miss du Maurier has drawn on the early secret writings of the four Brontës, letters, and other sources and has written a penetrating and revealing study of “the eloquent unpublished poet” that was Branwell Brontë.

. . . . . . . . .

The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

When Mrs. Gaskell published her Life of Charlotte Brontë in 1857, she painted so vivid a picture of life at Haworth parsonage, and of the talented, short-lived family who dwelt within its walls, that every Brontë biography written since has been based upon it.

After a hundred years had gone by, the biography was still unsurpassed, but during the intervening time much had come to light about the early writings of the young Brontës, proving that from childhood and on through adolescence they lived a life of quite extraordinary fantasy, creating an imaginary world of their own, peopled with characters more real to them than the inhabitants of their father’s parish.

Charlotte’s Jane Eyre, Emily’s Wuthering Heights, and Anne’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall were all famous novels and their authoresses dead when Mrs. Gaskell came to write about them. What she did not realize was that none of these novels would have come into being had not their creators lived, during childhood, in this fantasy world, which was largely inspired and directed by their only brother, Patrick Branwell Brontë.

Neither Mrs. Gaskell nor the elder Mr. Brontë suspected that under the parsonage roof there were manuscripts, written by Branwell and Charlotte, which ran into many hundreds of thousands of words far— more than the published works of Charlotte, Emily and Anne.

Although, on examination, Branwell’s manuscripts show that he did not possess the amazing talent of his famous sisters, they prove him to have had a boyhood and youth of almost incredible productivity, so spending himself in the process of describing the lives and loves of his imaginary characters that invention was exhausted by the time he was twenty-one.

Mr. Brontë, their father, writing to Mrs. Gaskell after she had published the biography of his daughter Charlotte, told her: “The picture of my brilliant and unhappy son is a masterpiece.”

He did not understand, any more than Mrs. Gaskell, that the “brilliance” existed to a great extent in his own imagination, the pride of a lonely widower in the extraordinary precocity and endearing liveliness of a boy whose supposed genius disintegrated with the coming of manhood; whose unhappiness was caused, not by the abortive love-affair described by Mrs. Gaskell with such gusto, but by his inability to distinguish truth from fiction, reality from fantasy; and who failed in life because it differed from his own “infernal world.”

One day, perhaps, all the manuscripts which poured from Branwell’s pen will be transcribed, not for the Brontë student only, but for the general reader. One day the definitive biography of this tragic young man will be published.

Meanwhile, many years of interest in the subject, and much reading, have prompted the present writer to attempt a study of his life and work which may serve as an introduction to both.

If it brings some measure of understanding for a figure long maligned, neglected and despised, and helps to reinstate him in his original place in the Brontë family, where he was, until the last years of disintegration, so loved a person, then this book will not have been written in vain. ( — Daphne du Maurier, Cornwall, 1960)

. . . . . . . . .

Brontë’s Mistress on Bookshop.org*

Brontë’s Mistress on Amazon*

Branwell Brontë has yet to be the subject of a full biography, but his illicit love affair with the wife of an employer has been given fictional treatment in Brontë’s Mistress by Finola Austin.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë by Daphne du Maurier appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 31, 2021

Hangsaman by Shirley Jackson, 1951 — an Analysis

This analysis of Hangsaman, Shirley Jackson’s chilling and thought-provoking 1951 novel, is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

In a 1956 book called Sex Variant Women in Literature, the academic critic, Jeanette H. Foster referred to Hangsaman as “an eerie novel about lesbians.’ This is a bizarre reading of the novel and Shirley Jackson was incensed. Her biographer, Judy Oppenheimer, quoted her as saying:

“I happen to know what Hangsaman is about. I wrote it. And dammit it is about what I say it is about and not some dirty old lady at Oxford. Because (let me whisper) I don’t really know anything about stuff like that. And I don’t want to know… I am writing about ambivalence but it is an ambivalence of the spirit or the mind, not the sex. My poor devils have enough to contend with without being sex deviates along with being moral and romantic deviates.”

Because she had children of her own, and wrote innocuous books and magazine pieces about her charming but chaotic family life, Shirley Jackson presumably found it quite difficult to write about sex. So she didn’t. Does Natalie Waite in Hangsaman go the whole hog? If so, with whom: is it with an older man, one of her father’s friends, or even perhaps her father himself? We don’t know.

As in Heinrich von Kleist’s The Marquise of O there is a lacuna around Natalie’s first – possible – experience of sex; perhaps the experience was so awful that she has erased from her mind and Jackson has erased it from the novel.

It feels almost as if some clumsy censor has excised a whole section that would have described her experience. But neither at the time it happens nor later in the novel are we given any idea of what actually happened; we know Natalie has been irrevocably changed but not by what exactly.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Shirley Jackson

. . . . . . . . . .

The critics at the time were not always kind to Hangsaman: The Saturday Review, May 5, 1951, compared Hangsaman to Jackson’s notorious short story The Lottery, where villagers choose one person a year to be stoned to death, which had been published not long before and caused an enormous – almost entirely negative – response.

“Now in the novel Hangsaman and on its much larger scale Miss Jackson again proceeds from realism to symbolic drama. Here the method fails. The tones do not flow into one another … Like many another story, this one is about the maturing of an adolescent. Natalie Waite, though, is a very special seventeen; not so much in her un-adult trick of occasionally blurting out exactly what she is thinking as in the quality of her thinking and in her literary background.

Natalie is an exceptionally talented, intellectual child, already supervised by her father, who is apparently a sort of critic and certainly an egotistical fool … Natalie was raped or seduced offstage at her father’s cocktail party.

Presumably the emotional effects were profound, but we don’t know any more about them than we know, for instance, about the effects of a flock of martinis Natalie absorbed one afternoon and for the first time. Miss Jackson’s method of not-quite-telling begins to show its disadvantages.”

Another review of the time, in The Age, from Melbourne Australia, February 1952, was titled “A Novel of Emotional Bewilderment”:

“Shirley Jackson, with the acuteness of a surgeon, lays bare the tissue and nerves of adolescent emotions in her novel, Hangsaman. She portrays the period between childhood and maturity in the life of an American girl when self assumes immense proportions and demands constant dramatization, gaining importance and size in these imaginary flights …

This story is one to bring terror to the heart of a parent sending an unadaptable child out among her fellows. One would think that it must surely be autobiographical, so deeply has the author plunged in her description of the cruelty girls can deal one to another and of the brutality with which the can win a place in the mob.

It is a harrowing and particularly vicious picture and not an easily assimilated one. Incidents are part of the general emotional bewilderment of scenes that build to a climax, leaving the reader to wonder to the last moment whether Natalie will escape.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

Girls in Bloom on Amazon UK*

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

Despite the critics, the writing in Hangsaman is controlled and masterly; it is one of the finest of all coming of age novels. There is a wonderful passage where Jackson describes the crucial moment of adolescence where the girl becomes the woman, with her own will and a personality separate from that of her parents and family. For Jackson, naturally, this transition is effected by creativity, in this case, as in Jackson’s, the creativity of writing.

There was a point in Natalie, only dimly realized by herself, and probably entirely a function of her age, where obedience ended and control began; after this point was reached and passed, Natalie became a solitary functioning individual, capable of ascertaining her own believable possibilities.

Sometimes, with a vast aching heartbreak, the great, badly contained intentions of creation, the poignant searching longings of adolescence overwhelmed her, and shocked by her own capacity for creation, she held herself tight and unyielding, crying out silently something that might only be phrased as, “Let me take, let me create.”

If such a feeling had any meaning to her, it was as the poetic impulse which led her into such embarrassing compositions as were hidden in her desk; the gap between the poetry she wrote and the poetry she contained was, for Natalie, something unsolvable.

Along the same lines, one of Natalie’s father’s friends says to her: “Little Natalie, never rest until you have uncovered your essential self. Remember that. Somewhere, deep inside you, hidden by all sorts of fears and worries and petty little thoughts, is a clean pure being made of radiant colors.” This is “so much like the things that Natalie sometimes suspected about herself,” that she asks, “how do you ever know?”

. . . . . . . . . .

Hangsaman by Shirley Jackson: A Review

Hangsaman on Bookshop.org*

Hangsaman on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Like a true creative spirit, Natalie lives mainly in her head, in a fantasy world which includes, as the novel opens, a kind of noir detective story where she is a suspect. Whatever she is doing, the story keeps playing out in her mind and in the narrative, a story where she is the central figure, the protagonist, the heroine.

This is a very common adolescent fantasy and Natalie’s character in her own story is rather like the many girl detective stories of the time, though at seventeen she is rather too old for this kind of fiction, at which her writer father would no doubt sneer.

“Natalie, fascinated, was listening to the secret voice which followed her. It was the police detective and he spoke sharply, incisively, through the gentle movement of her mother’s voice. ‘How,’ he asked pointedly, ‘Miss Waite, how do you account for the gap in time between your visit to the rose garden and your discovery of the body?’”

This particular fantasy stops when she goes to college, to be replaced by another, her imaginary friend Tony (female, despite her name); more of her shortly. Natalie is about to leave for college as the novel opens; she is “desperately afraid,” even though the college is only thirty miles away and is the one that her father has chosen for her. Here Jackson describes the unbridgeable gulf between a teenager and her parents:

“Natalie Waite, who was seventeen years old but who felt that she had been truly conscious only since she was about fifteen, lived in an odd corner of a world of sound and sight past the daily voices of her father and mother and their incomprehensible actions. For the past two years – since, in fact, she had turned around suddenly one bright morning and seen from the corner of her eye a person called Natalie, existing, charted, inescapably located on a spot of ground, favored with sense and feet and a bright-red sweater, and most obscurely alive – she had lived completely by herself, allowing not even her father access to the farther places of her mind.”

The father-daughter dynamic

Nevertheless, like other teenage girls in Girls in Bloom, she is close to her father, a writer, who critiques her writing as if he were her mentor rather than her father. In this she is very close to Cassandra Mortmain in I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith, a novel which also prefigures Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle. Her father is kindly but patronizing towards Natalie, who he says is ‘too untaught for literature and too young for drink.”

Natalie’s father is also no doubt to some extent a portrait of Jackson’s husband, Edgar Hyman, a critic and book reviewer whose relationship with Jackson is presumably in some ways portrayed in Natalie’s relationship with her father. “Do you realize I’m two weeks behind in my work?’ he asks his wife. ‘I’ve got to review four books by Monday; four books no one in this house has read but myself… Not to mention the book.”

At the mention of his book, “his family glanced at him briefly, in chorus, and then away;” no doubt Hyman and Jackson’s family reacted similarly. Hyman’s heavyweight The Armed Vision: A Study in the Methods of Modern Literary Criticism was published in 1947, his next book, The Critical Performance: An Anthology of American and British Literary Criticism in Our Century was published in 1956, nine years later and his third, Poetry and Criticism: Five Revolutions in Literary Taste in 1961.

Shirley Jackson’s life in the period of this novel

In this period, Jackson published five novels (with another in 1962), two collections of her lightweight – as both she and Hyman saw them – magazine pieces, a collection of short stories and numerous individual stories in magazines.

But this was at a time when a woman’s place was in the kitchen and her role was, as Virginia Woolf said, to magnify her man’s reflection in the mirror of her self; no doubt both Hyman and their friends saw his work as the most important thing, as do Natalie’s family.

Unlike Woolf, Jackson did not have a room of her own and had to be Woolf’s ‘angel in the house,’ though she was hardly the soft, gentle, beautiful, radiant type of angel. In the introduction to Just an Ordinary Day, a posthumous collection of Jackson’s stories, two of her children wrote about how she balanced domesticity and creativity.

“Our mother tried to write every day, and treated writing in every way as her professional livelihood. She would typically work all morning, after all the children went off to school, and usually again well into the evening and night. There was always the sound of typing. And our house was more often than not filled with luminaries in literature and the arts. There were legendary parties and poker games with visiting painters, sculptors, musicians, composers, poets, teachers, and writers of every leaning. But always there was the sound of her typewriter, pounding away into the night.”

This is very much a description of the literary garden parties that Natalie’s father hosts on Sundays, which are rather reminiscent of the Ramsay’s dinner party in Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, whose modernist pretensions Jackson nicely deflates. It is after one of these parties that Natalie – probably – has her first sexual experience; it is foreshadowed when her father says to her: “Daughter mine … has anyone yet corrupted you?”

Someone is about to:

“… She was almost sure of this, the preliminary faint stirrings of something about to happen. The idea once born, she knew it was true; something incredible was going to happen, now, right now, this afternoon, today; this was going to be a day she would remember and look back upon, thinking, That wonderful day … the day when that happened.”

An older man, who is not named and whom she does not seem to know, asks her to sit down: “He was old, she could see now, much older than she had thought before. There were fine disagreeable little lines around his eyes and mouth, and his hands were thin and bony, and even shook a little.”

He tells Natalie that her father has described her as “quite the little writer … Obviously meaning to make her sound less like her mother and more like a frightened girl not yet in college.”

Natalie is hurt by this and responds, “I suppose you probably want to write too?” Natalie tries to get up to leave but he holds onto her. “A little chill went down Natalie’s back at his holding her arm, at the strange unfamiliar touch of someone else.” In Natalie’s head the detective says to her: “This you will not escape.” The “strange man” leads Natalie away. She has been telling him about “how wonderful I am.”

They end up in the woods where Natalie used to play when she was a child: “The trees were really dark and silent, and Natalie thought quickly. The danger is in here, in here, just as they stepped inside and were lost in the darkness.”

They sit down the grass. Oh my dear God sweet Christ, Natalie thought, so sickened she nearly said it aloud, is he going to touch me? If he does, Jackson does not tell us.

The next paragraph has Natalie waking up the next morning, “to bright sun and clear air,” before burying her head in the pillow and saying:

“‘No, please no’.

‘I will not think about it, it doesn’t matter,’ she told herself, and her mind repeated idiotically, It doesn’t matter, it doesn’t matter, it doesn’t matter, it doesn’t matter, until, desperately, she said aloud, ‘I don’t remember, nothing happened, nothing that I remember happened.’

Slowly she knew she was sick; her head ached, she was dizzy, she loathed her hands as they came toward her face to cover her eyes. ‘Nothing happened,’ she chanted, ‘nothing happened, nothing happened, nothing happened, nothing happened.’

… Someday, she thought, it will be gone. Someday I will be sixty years old, sixty-seven, eighty, and, remembering, will perhaps recall that something of this sort happened once (where? when? who?) and will perhaps smile nostalgically thinking, What a sad silly girl I was, to be sure.’”

Before whatever happened, happened, the detective in Natalie’s head had said to her: ‘No one can live through such things and not remember them,’ but Natalie is determined not to remember and Jackson is determined not to tell us.

She does tell us that “the most horrible moment of that morning or any morning in her life, was when she first looked at herself in the mirror, at her bruised face and her pitiful, erring body,” but none of her family notice anything wrong with her face and perhaps the bruising is entirely internal. Later, at college, she writes in her private journal, where she splits off a separate personality and talks to herself in the third person:

“Perhaps, you thought, Natalie is frightened and perhaps she even thinks sometimes about a certain long ago bad thing that she promised me never to think about again. Well, that’s why I am writing this now. I could tell, my darling, that you are worried about me. I could feel you being apprehensive, and I knew what you were thinking about was you and me.

And I even knew that you thought I was worried about that terrible thing, but of course – I promise you this, I really do – I don’t think about it at all, ever, because both of us know that it never happened, did it? And it was some horrible dream that caught up with us both. We don’t have to worry about things like that, you remember we decided we didn’t have to worry.”

She does leave for college, where, unlike her mother and her author, Natalie has a room of her own, “the only room she had ever known where she would be, privately, working out her own salvation.” The college is described as being very much like the liberal, girls-only Bennington College in Vermont where Jackson’s husband Edgar Hyman taught.

There Natalie meets a professor, Arthur Langdon, who seems to be another portrait of Hyman (even their names are concordant). Langdon has a wife who, like Natalie’s mother but completely unlike Jackson herself is entirely subsumed under her husband’s ego and has, as Hyman undoubtedly did, a circle of young, devoted female admirers. Langdon soon steps into the role that had been filled by Natalie’s father, and gives Jackson another chance to muse on the absurdity of being a writer.

“‘I find your criticisms very helpful,’ Natalie said demurely. ‘My father discusses my work with me very much as you do.’ She thought of her father with sudden sadness; he was so far away and so much without her, and here she was speaking to a stranger.

‘Do you plan to be a writer?’

A what? Natalie thought; a writer, a plumber, a doctor, a merchant, a chief; the best-laid plans of; a writer the way I might plan to be a corpse? ‘A writer?’ she repeated, as though she had never heard the word before.”

Natalie make some friends at the college and fits in well enough, though she is never part of any crowd, too bookish and self-sufficient for the rest of the girls. One friend says that the other girls accuse her of sitting in her room all day and never going out; “They say you’re crazy. You sit in your room all day and all night and never go out and they say you’re crazy… you’re spooky.”

Natalie’s answer to this comes in her own private journal, which Jackson allows us limited access to:

“Dearest dearest darling most important dearest darling Natalie – this is me talking, your own priceless own Natalie, and I just wanted to tell you one single small thing: you are the best and they will know it someday, and someday no one will ever dare laugh again when you are near, and no one will dare even speak to you without bowing first. And they will be afraid of you. And all you have to do is wait, my darling, wait and it will come, I promise you.”

Later it seems that Natalie has split herself into two in a different way: by inventing a female friend named Tony. It’s not entirely clear at first that Tony is imaginary but after much romantic talk – not romantic in the lesbian sense, despite what Jackson’s Oxford critic said – about traveling the world together they end up alone in a dark wood, where Tony disappears.

This time, nothing bad happens to Natalie in the woods and a friendly couple in a car pick her up and take her back to town, drop her off at the bridge where she appears for a moment to contemplate suicide. But then, one with herself again, she heads back to the college; she has come of age. “As she had never been before, she was now alone, and grown-up, and powerful, and not at all afraid.”

More about Hangsaman by Shirley Jackson

Reader discussion on Goodreads You Might Never Find Your Way Back: Shirley Jackson’s Hangsaman Shirley Jackson’s Hangsaman — what does it mean?. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop.org and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Hangsaman by Shirley Jackson, 1951 — an Analysis appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 30, 2021

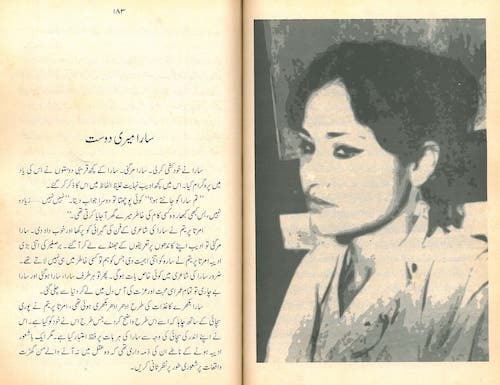

9 Classic Pakistani Women Novelists And Poets to Discover

Discover some of the best-known classic women Pakistani novelists and poets who challenged society’s norms and made invaluable contributions to literature.

Many classic Pakistani women authors were born before the partition and lived through the horrors of migration. They had to adjust to a new life in the new country, and these extraordinary life experiences seep into their writings. (Pictured here, Fahmida Riaz.)

With their fiery words, they bent social norms and challenged patriarchy and debauchery long before the concept of feminism or human rights became a part of living room discussions.

“Words can be like x-rays. If you use them properly – they’ll go through anything. You read, and you’re pierced.” (Aldous Huxley, Brave New World)

The authors and poets have been listed in chronological order of their birth.

. . . . . . . . . .

Ada Jafri

Ada Jafri (1924 – 2015) is regarded as the pioneer of Urdu poetry. She is known as The First Lady of Urdu Poetry. Her preferred genre was ghazal, but she also experimented with free verse poetry. Her notable works include Main Saaz Dhundti Rahi and Shahr-i-Dard under the pen name Ada.

Jazib Qureshi, the famous Urdu poet, and critic once said, “Ada Jafarey is the first and only lady poet who carries in her poetry the eternal colors of Ghalib, Iqbal, and Jigar.”

Ada Jafri expressed herself in Urdu. Though her works were never formally translated into English, some die-hard fans translated a few of her poems to English and compiled them with other renowned poets. Ada Jafri’s poetry revolves around feminism, gender discrimination, and the dehumanization of women in society.

. . . . . . . . .

Altaf Fatima

Altaf Fatima (1927 – 2018) was an Urdu novelist, short story writer, and teacher. She lived a life of penmanship, devoting every moment towards the progress of Urdu literature. She left behind a formidable amount of creative and thought-provoking writings.

Though she never received any recognition for her immense dedication and contributions to Urdu literature, she was too dignified to care for awards and continued with her struggle for its progress and revival.

Having experienced the partition herself, Altaf Fatima had tons of stories to tell. Her writings explore the post-partition struggles, especially how women became a solid shield to protect their children and themselves against the horrendous atrocities during migration.

Her best work, Dastak Na Do, was translated into English as The One Who Did Not Ask by Heinemann, and Herald also published its abridged version. In the early days after the partition, the novel was also televised by Pakistan Television Corporation (PTV).

. . . . . . . . . . .

Khadija Mastoor

Khadija Mastoor (1927 – 1982) was one of the leading Pakistani novelists who made a prominent mark on Urdu literature. She started her journey by inscribing short stories. Her five short stories and two novels have been published and recognized all over the world to date.

Khadija Mastoor is known for her incredible writing style and themes based on observation and experience. She wrote from her life experiences, whether they be about politics, society, or morals.

Among her many novels, Aangan (translated to English as The Women’s Courtyard ) was her most significant work, which was also dramatized for Pakistan Television. The novel won her the prestigious Adamjee Literary Award and is considered one of Urdu’s most prominent literacy achievements. Many of her other books have been translated into English.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Bano Qudsia

Bano Qudsia (1928 – 2017) is one of the most renowned Pakistani novelists, playwrights, and spiritualists. Recipient of multiple awards, including Sitara-i-Imtiaz, Hilal-i-Imtiaz, and Lifetime Achievement Award, Bano Qudsia is considered the epitome of classic Urdu literature. She wrote many thought-provoking short stories, incredible novels, and provocative dramas.

The wife of renowned author Afshaq Ahmed, Bano Qudsia, credits her husband for her success and wide recognition. Her five-decade marriage empowered her to devote her life to writing. Her words take a jab at the uneven distribution of power across genders and encourage women to stand against oppression and find their voice.

Though every piece of writing by Bano Qudsia is laudable, Raja Gidh (King Buzzard) gave her true success and recognition. Raja Gidh is such a significant literary piece that it has been a basis of research by the University of North Texas scholars.

. . . . . . . . . .

Afzal Tauseef

Afzal Tauseef (1936 – 2014), the Pride of Performance award recipient, was a Punjabi language writer, columnist, and journalist. She served as Vice President of the Punjabi Adabi Board (PAB) as well.

From political stigma to social issues, and art and literature, Tauseef’s words are a revolution for the people of Pakistan against the oppressive landowners aided by bureaucracy and games played by corrupt politicians.

She was born in Hoshiarpur (India) before the partition. Although she migrated to Pakistan, her writings influenced both countries’ literature. Therefore, many of her books were translated into Gurmukhi for the Indian audience. Amrita Pritam from India gave Afzal Tauseef the title of True Daughter of Punjab due to her bold stance against the treason accusations and self-proclaimed status of a revolutionary freedom fighter.

. . . . . . . . . .

Khalida Hussain

Khalida Hussain (1937 – 2019) is regarded as one of Pakistan’s finest fiction writers who blurs the line between political and aesthetic writing. Recipient of the Pride of Performance award, Khalida Hussain started her writing career with short stories and focused on them primarily. However, it was her first and only novel Kaghazi Ghat that brought her the recognition she deserved.

What makes Khalida Hussain unique is that her writing defies any boundaries. Her stories revolve around the exploration and interrogation of themes that are predominantly political and revolutionary. Her writings are imbued in the fluidity of time and life, genderless, and in harmony with the outer and the inner world.

. . . . . . . . . .

Fahmida Riaz

Fahmida Riaz (1946 – 2018) was a phenomenal poet, writer, feminist, and human rights activist. The Pride of Performance Award recipient, Riaz, had been the center of controversies throughout her lifetime. Her poetry is believed to be ahead of her time. She was accused of using sensual and erotic expressions in her poetry, the themes that were taboo at that time (and even today).

Despite all the hardships and accusations, Fahmida Riaz has a powerful presence in the literary world. Her prominence stands alongside Jean-Paul Sartre, Pablo Neruda, Simone de Beauvoir, and Nazim Hikmet.

Riaz is also credited for translating Shaikh Ayaz and Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai’s work from Sindhi to Urdu and Maulana Jalaluddin Rumi’s work from Persian to Urdu.

Read her poetry translated into English in Four Walls and a Black Veil and The Body Torn and Spanish in Es Una Mujer Impura: Antología Poética.

. . . . . . . . . .

Parveen Shakir

Parveen Shakir (1952 – 1994) became one of the greatest poets of Pakistan in her short life span. She rose to prominence due to her incredible feminine voice, which won her the prestigious Adamjee Literary Award and Pride of Performance Award. What makes Parveen Shakir stand out is her distinctive feminine voice that explores and expresses the world and all the experiences from a girl’s eyes, pure and innocent in her visage.

Parveen Shakir was loved and celebrated for her soulful poetry in the ghazal and free verse style. Her poetry’s central theme has always been a woman sharing the female perspective on life, love, marriage, motherhood, repression, and social restraints. Her poetry explored beauty, separation, intimacy, distances, heartbreaks, infidelity, and adultery with a rare mystical perfection.

An unfortunate accident took away her life, but her life, poetry, and charisma are celebrated all over Pakistan to date. Naima Rashid translated some of her selected poems and compiled them under the cover, Defiance of the Rose.

. . . . . . . . . .

Sara Shagufta

Sara Shagufta (1954 – 1984) was a beautiful poet who lost her life to suicide at an early age. She was a 20th-century postmodern poet, feminist, visionary, and revolutionist whose polemic work frequently attracted criticism.

Mubarak Ali, a known Pakistani historian, and activist hailed her as Ghalib’s better half while Amrita Pritam, an Indian novelist, called her Sylvia Plath of the Subcontinent.

She gained posthumous recognition when her poetry compilation was published. To make sure her voice was heard far and wide, Asad Alvi translated her poetry into the English language. You can read many of Sara Shagufta’s translated poetry in Columbia Journal, at The Blank Garden, and in We Sinful Women published by The Women’s Press to celebrate the lives of badass Pakistani women poets.

Contributed by Sonia Ahmed. Sonia is a short story writer and editor of Penslips Magazine. She is an avid reader and loves a good story that inspires readers and challenges their core beliefs. A dreamer at heart, she writes tales of the ordinary people of the society and believes that every story is worth telling. She also writes non-fiction on subjects ranging from eco-friendly lifestyle to religion, science, and healthy living.

Explore more roundups of global literature:

10 Classic Indian Women Authors 10 Classic Cuban Women Authors to Discover 10 Classic Latina Poets to Discover and ReadThe post 9 Classic Pakistani Women Novelists And Poets to Discover appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 29, 2021

Solitude vs Self-Isolation: Women Authors and the Sacred Inner Space

Most artists and writers keep their inner space sacred and inviolate. It’s the core from where their creativity springs. Some keep their inner world more private than others.

While plenty of male writers have suffered from (or have preferred) isolation, this musing will focus on well known female writers. Confinement periods can be an advantage for women writers, as their extra-curricular activities may slow down.

Seeking solitude doesn’t make a writer antisocial. Perhaps periods of quarantines made it easier for writers to carve out specific periods of time where they can work in blissful solitude. A brief look at women authors of the past shows that self-imposed sequestration isn’t such a crazy thing to do, after all.

. . . . . . . . . .

Jane Austen

Though Jane Austen (1775 – 1817) had a portable desk on which she would scratch away with her quill, it was hidden from most visitors to her home. Even if Jane had shared her juvenile writings with her family, when it came to novels, the act of creating them was a private affair. Except for her sister Cassandra, most of her family were unaware of the contents of her novels while she was penning them in a secluded corner of her childhood home at Steventon.

After losing the love of her life, and having subsequently rejected a potential husband because she didn’t care for him (like her most famous character, Elizabeth Bennet of Pride and Prejudice) Jane must have experienced not just emotional loneliness, but possibly an intellectual one as well.

Though her family was quite well-educated, perhaps she lacked the stimulus that mingling with other writers, in London, for example, might have sparked her bright mind. Except for the fact that there were few women writers in those days, anyway.

There weren’t any other brains around as sharp as hers with whom she could have shared her keen observations on society, even if she’d wanted to. Her main confidante was her sister Cassandra, (who burnt most of Jane’s letters after the latter’s death). Reduced to genteel poverty after her father retired, Jane couldn’t write in Bath in houses that kept getting increasingly smaller, and dingy, as they had to move around a lot.

Both Jane and Cassandra had to cope with all attendant problems that come from descending the economic ladder, whilst trying to keep up appearances of social gentility. How many novels were lost in the years when Jane couldn’t find that safe secure unmoving shell where she could retreat and produce her warm characters whose brilliant wit continues to delight readers even today?

Though her desk was portable, (gifted to her by her father), perhaps she needed that still, silent point where she could find her center, and from where she could start exploring the minutiae and intricate web of her characters, and the complex social rules that they had to follow.

Her pen started flying again when her oldest brother Edward finally bestowed a cottage at Chawton to his mother and unmarried sisters, and where they could settle down without having fears of moving yet again due to financial constraints. There’s a story (which may be a myth) that Jane wouldn’t let the hinges of the door to her room be greased; whenever anyone entered it, the sound alerted her to that fact, and she could quickly hide her manuscript from prying eyes. Whether this is true or not, it’s a good metaphor for the woman writer’s desire for privacy.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Brontë sisters

The Brontë sisters toiled away at their oeuvres in relative secrecy in Haworth, in the West Riding area of Yorkshire in England. Though their cooperative ventures in childhood produced the Empire of Angria, and Gondal along with minute maps, sketches, and schemes, they grew increasingly apart even in the cramped quarters of the Parish house at Haworth.

Charlotte, the eldest Brontë, was the first to propose venturing into the world of publishing, but her younger sister Emily at first resisted. Emily, the middle and most reclusive of the three sisters (the youngest was Anne) has remained the most mysterious one as well. Ironically, she sought seclusion in the open moors near Haworth where she found solace far away from the confines of the tightly-knit, family web with its tangled and complicated emotional life. Her dog, Keeper, was perhaps her closest companion.

In modern times, perhaps the Brontë sisters might be called word nerds and social misfits. Aware of the fact that they were different from the ordinary folks surrounding them, possibly they suffered from emotional and increasingly intellectual loneliness as they grew more competitive with age.

In Charlotte Brontë’s most well-known novel, Jane Eyre, the madwoman in the attic, Bertha Mason could personify one part of the author’s own psyche which could have become increasingly complex after her unrequited love for Professor Héger in Brussels (where she taught at his school) ended with bitterness on her part.

. . . . . . . . . .

Jean Rhys

In her 1966 novel Wide Sargasso Sea, Jean Rhys (1890 – 1979) speculates as to who this mad woman, Bertha Mason, might have been. As it turns out, Antionette Cosway, a Creole heiress from West Indies (another misfit due to being mixed) was gradually driven into insanity by the excesses of her British husband — the young Mr. Rochester — due to his negligence, cruelty, displacement, and racism towards her.

Bertha wasn’t just socially isolated, but physically, emotionally, and spiritually as well. Was Bertha Mason in Jane Eyre Charlotte’s shadow double (as a Jungian analyst would have surmised)?

. . . . . . . . . .

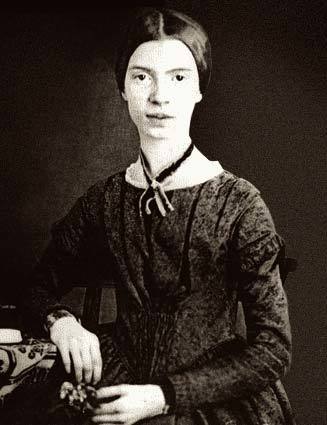

Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson (1830 – 1886) was an extreme case, the epitome of the solitary brilliant poet, as she spent nearly the last two decades of her short life as a recluse in her own home. Only around eleven of her poems (out of about 1,800) were published in her lifetime. Even if women authors weren’t exactly encouraged in those days, she deliberately kept hundreds of poems hidden even from her own family until these gems were discovered after her death.

It’s impossible to know why Emily Dickinson kept her work so secret, though usually, artists tend to be much more sensitive than the ordinary (wo)man on the street, and therefore, any kind of criticism can be taken too much to heart. Perhaps her writings didn’t fall on ears that were appreciative enough. Or perhaps writing these poems was an intensely personal experience, which couldn’t be shared by others.

Emily might be called a Highly Sensitive Person (HSP) now, and perhaps her life and work should be examined by this lens. Perhaps all the authors mentioned here were HSPs to varying degrees.

. . . . . . . . . .

Virginia Woolf

Dickinson was already living Virginia Woolf’s famous lines illustrating the concept that “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” Apart from the feminist slant given to Woolf’s well-known statement, perhaps a woman didn’t need just independence, but also a degree of privacy in which to create.

Despite belonging to the Bloomsbury Group, and living a relatively social life, some of Woolf’s inner aloneness may have bled onto the page, and found an echo in Clarissa Dalloway’s inner despondent landscape.

Woolf (1882 – 1941), best known for taking the stream of conscious style of writing to exquisite heights, held onto the idea of keeping a part of her inner core inviolate, as a writer can’t possibly share all her thoughts with the public, or even with those who are close to her. Though she suffered from mental illness, partly due to her mother’s premature death, partly due to the abuse she endured at the hands of her stepbrother), and/or chemical imbalances, her bipolar disorder may have been augmented by her overly sensitive nature.

One sign of her insanity was that she believed that birds were speaking to her in ancient Greek. If only she’d been able to note down whatever it was that they’d said. Existential issues (inherent to the human condition) could have started looming like huge grey clouds. Her increasing emotional and spiritual loneliness could have pushed her to commit suicide.

. . . . . . . . . .

Colette

Unlike the other writers mentioned here, Colette (1873 – 1954) who had an outgoing, exuberant personality, delighted in swirling through the artistic and intellectual circles of Paris, when her much older husband, Henry Gauthier-Villars (Willy) brought her there in 1893.

The couple lived together from 1893 to 1906. Colette was literally locked into a room by Willy to compel her to produce writings that he could sell (these turned out to be the Claudine stories). If anything, this proves that writing tends to be a solitary exercise, even under duress — unless one is part of a purposeful duo or team.

For many years, Willy passed the Claudine novels off as his own writings. In the end, he took credit and royalties for these books that Colette had written originally. However, after she left him, due to her straitened circumstances, Colette must have finally learned to resist the temptation of the stage and bright lights and sit down to write, as she produced numerous major works, with Cheri and The Last of Cheri being among the best known.

. . . . . . . . . .

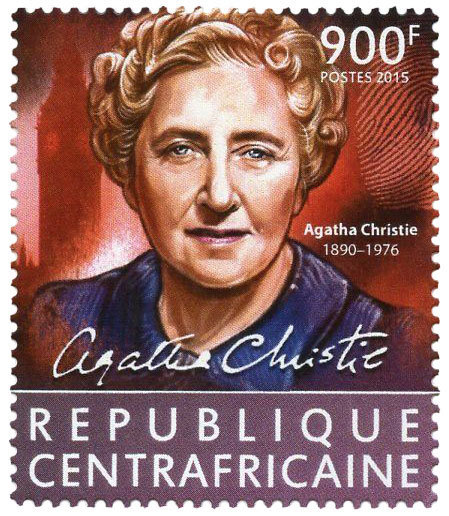

Agatha Christie

Was Agatha Christie’s (1890 – 1976) need for privacy so great that in December of 1926, she disappeared for about ten days? This lead to a nationwide hunt, and furor in the press. Perhaps Christie wasn’t expecting that. But she didn’t step forward. Instead, she was discovered at a hotel in Harrogate. Perhaps she was growing so lonely in her marriage due to her husband’s affair that she preferred to run away.

It’s not clear whether it was to punish him, take some personal time off, or if she’d staged her own disappearance to humiliate her spouse, or for publicity, or if she’d genuinely lost her memory. In any case, sequestration was preferable for her at that period of her life.

She then took refuge in her sister’s house, and early next year went to the Canary Isles to recuperate. She’d find fodder for her books during her travels in subsequent years. She would remain unattached until 1930, when she met her second husband.

. . . . . . . . . .

Daphne du Maurier

Known for being reclusive and even frosty, Daphne du Maurier (1907 – 1989), was supposedly quite cold towards her two daughters, but warmer towards her son. Perhaps her complicated relationships, which may have led to a double life, and accusations of plagiarism may not have been conducive to being gregarious.

Given the balancing act that her emotional and professional lives may have been, du Maurier must have preferred that some equations of her life remain unsolved, like the character of Rachel in My Cousin Rachel.

. . . . . . . . . .

P.L. Travers

Though P.L. Travers (1899-1966) maintained she didn’t know how Mary Poppins had popped onto her pages, at least she knew where these stories had evolved. In 1934, since she was suffering from pleurisy, she retreated to a cottage in Sussex to recover. Since she started making up a story to entertain two visiting children during this period of semi-confinement, she ended up with the first book of Mary Poppins.

For most of her life, Travers kept her personal life under wraps, as in her youth, many of her acquaintances in London didn’t even know she was Australian. At age forty she adopted a son, Camillus Hone, but that relationship didn’t go well. Was her solitude alleviated somewhat because of this relationship? While only Travers might answer to that question, she drew a lot of flak for her adopted son’s subsequent problems with alcoholism.

The TV documentary, The Secret Life of Mary Poppins: A Culture Show Special touches upon her turbulent relationship with Camillus. On the one hand, she’s been justifiably criticized for not telling him that he had a twin brother, only finding out when his twin tracked him down.

On the other hand, the Hone family has not been held responsible for allowing her to adopt just one twin, and for leaving Camillus in her supposedly incompetent hands, despite his many problems. Just because she wrote about a magical nanny, Mary Poppins, does that mean she should’ve had those excellent child-rearing skills herself?

Writing can be exhausting and draining for some writers, as it can be an emotionally demanding, and soul-searching activity. It leaves little room for “normal” family life. While most male writers can conveniently leave the rearing of their off-springs to their spouses, or other female relatives, women writers are held more accountable for how they bring up their children. This is not an easy job in the best of circumstances.

. . . . . . . . .

Conclusion: The solitary female writerThe solitary female has traditionally been stigmatized as being either problematic or undesirable. Perhaps that’s the reason female writers struggle with loneliness more. However, the quarantine may have liberated some from the need to socialize to fit better into society.

Since writers are a part of society, they have to keep a foot in it. However, if they’re going to depict humanity and associated social structures in all their myriad forms in their work, authors have to be somewhat removed from them. Not just to be able to observe society, but also to comment on it via their creative endeavors.

So, is the unconscious act of self-isolation a necessary part of the creative process? Not to mention that not many “normal” people have trouble understanding writers and artists, and where they’re coming from in the first place. These kinds of solitary activities may even arouse some sort of suspicion in their entourage.

On one hand, the act of writing is necessarily a solitary one. On the other, if the artist is to portray, or critique, or comment on society through their work, they must observe social phenomena to recreate a version of it in their texts. Some of us prefer to live in seclusion or tend to lead semi-sequestered lives under normal circumstances.

According to Barbara Sher (1935 – 2020), author of Refuse to Choose, “Isolation is the dream killer, not your attitude.” So it’s a question of creating a balancing act as away to succeed as a writer. Though many extrovert writers do well in their lifetimes — being good at networking, and building their images — it’s the quality of the work that ensures a long shelf life.

The quarantines of the year 2020 proved to be a blessing in disguise for many artists and writers, as it offered quiet time to create, write, edit, or submit their works for publication. Yet, it was difficult to keep one’s sanity through the many uncertainties that arose during this worrisome time. At the same time, every major change in the social, economic, and political climate can provide fuel for the writer’s imagination, which constantly needs to be ignited.

This piece originally ran on Literary Yard

Contributed by Sultana Raza: Of Indian origin, Sultana Raza’s creative non-fiction has appeared in countercurrents.org, Litro, Gnarled Oak, Kashmir Times, and A Beautiful Space. Her 100+ articles (on art, theatre, film, and humanitarian issues) have appeared in English and French. An independent scholar, Sultana Raza has presented many papers related to Romanticism (Keats) and Fantasy (Tolkien & GRR Martin) in international conferences.

Her poems have appeared in numerous journals, including Columbia Journal, The New Verse News, London Grip, Classical Poetry Society, spillwords, Poetry24, Dissident Voice, and The Peacock Journal. Her fiction has received an Honorable Mention in Glimmer Train Review (USA), and has been published in Coldnoon Journal, Szirine, apertura, Entropy, and ensemble (in French). She has read her fiction/poems in India, Switzerland, France, Luxembourg, England, Ireland, the U.S.

The post Solitude vs Self-Isolation: Women Authors and the Sacred Inner Space appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 23, 2021

6 Classic Early- to Mid-20th Century Lesbian Novels

Though the classic lesbian novels surveyed here – published from the early through mid-twentieth century – seemed truly groundbreaking in their time, they certainly weren’t the first of this genre of literature. From the poetry of Sappho to the secret diaries of Anne Lister to queer re-evaluations of many classic women authors, the books listed here had plenty of forerunners.

The difference? Though some were more forthright than others, there was less of the thinly veiled allusions, and more overt same-sex love and romance. Though by no means the only fine examples of the genre, the six novels presented here were hugely impactful.

. . . . . . . . .

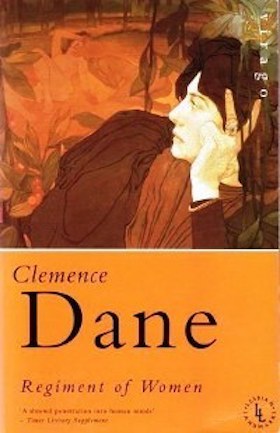

Regiment of Women by Clemence Dane (1917)

The Well of Loneliness, usually said to be the first English-language novel containing veiled lesbianism, was just beaten to the title by Rosamond Lehmann’s Dusty Answer, 1927. But ten years before even that was Regiment of Women, 1917, the debut novel of Clemence Dane, the pseudonym of Winifred Ashton (1888-1965), London-born novelist, playwright, and early feminist.

Dane’s title is obviously ironic but at least two of the book cover designers completely misunderstood the title, or more likely had not read the book: one has a picture of a woman in uniform, depicting a female member of a military regiment, and the other has a picture of a boys’ school. Read more about Regiment of Women.

. . . . . . . . . .

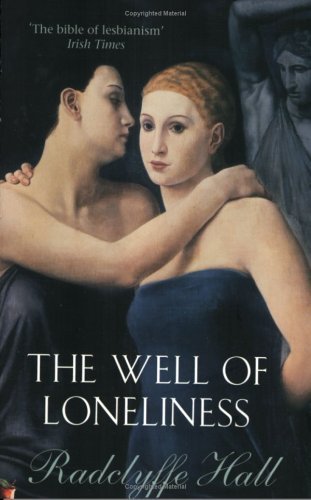

The Well of Loneliness by Radclyff Hall (1928)

Since its first appearance in 1928, The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall (1880 – 1943) has spurred much discussion and controversy. The semi-autobiographical novel about a young woman’s coming to terms with her lesbian identity caused a furor when first published in England. Widely banned, it also went to trial for obscenity.

Once denounced as immoral, it has also been praised as a courageous work of literature. It shocked some members “proper” society and served as an awakening to others who felt isolated by repressive social mores. At the time it was published, it told the story of same-sex love between women, a topic that was rarely written about outside of scientific textbooks. Read more about The Well of Loneliness.

. . . . . . . . . .

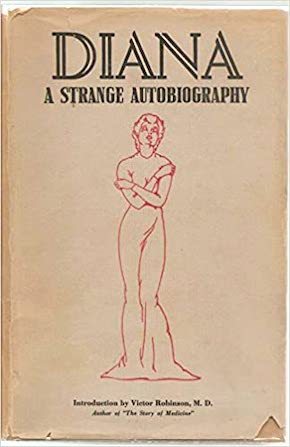

Diana by Diana Fredericks (Frances V. Rummell, 1939)

Frances V. Rummell, an American writer and educator, published Diana: A Strange Autobiography (1939) under the pseudonym Diana Frederics. More of an autobiographical novel than an actual memoir, nonetheless draws upon the author’s life. The story details the title heroine’s discovery of her lesbian sexuality.

Positive portrayal of lesbians was considered shocking when the book was published. It’s now considered groundbreaking as one of the first works of gay fiction to have a happy outcome.

Published squarely between The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall (1928) and the lesbian pulp novels that emerged in the early 1950s, Diana is a worthy, yet often overlooked addition to the genre. More about Diana: A Strange Autobiography.

. . . . . . . . . .

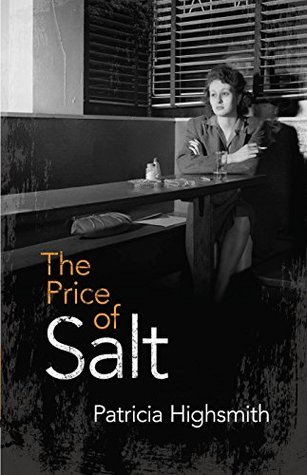

The Price of Salt by Claire Morgan (Patricia Highsmith, 1952)

When The Price of Salt was published in 1952, it was a rarity in lesbian literature. Lesbian pulp novels were quite a thing, but in order to pass censors, one of the two protagonists had to either come to a bad end or realize that she was straight, after all. The Price of Salt by Patricia Highsmith was published under the pseudonym Claire Morgan.

Highsmith was at the start of a career writing thrillers about sociopaths (such as the one in her first book, Strangers on a Train, the basis for the 1951 Hitchcock film). The Price of Salt was an early departure from what was to be her preferred genre — psychological thrillers; it would remain an outlier among her works. The novel was adapted as the 2015 film, retitled Carol (2015 film version of The Price of Salt). More about The Price of Salt.

. . . . . . . . . .

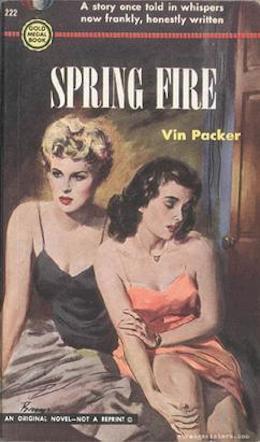

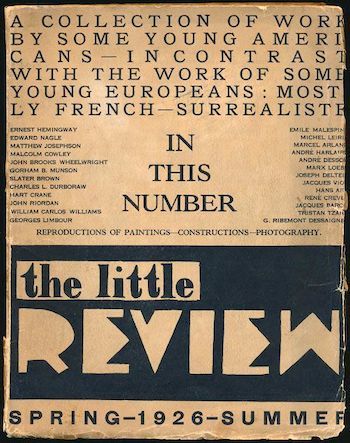

Spring Fire by Vin Packer (Marijane Meaker, 1952)

1952 was something of an annus mirabilis for the lesbian coming of age novel, seeing the paperback republication of the aforementioned Diana, and the original publication of The Price of Salt and Spring Fire by Vin Packer, the pen name of Marijane Meaker. Spring Fire has the distinction of being the first lesbian paperback-original novel (The Price of Salt was issued as a Bantam paperback in 1953, but this was after the release of the hardback).

The central character of Spring Fire, Susan (Mitch) Mitchell is rich. “She was not lovely and dainty and pretty, but there was a comeliness about her that suggested some inbred strength and grace.” She has been to several different boarding schools over a period of six years with no apparent romantic or any other kind of interest in or from other girls. This changes, of course, as the novel progresses. More about Spring Fire.

. . . . . . . . . .

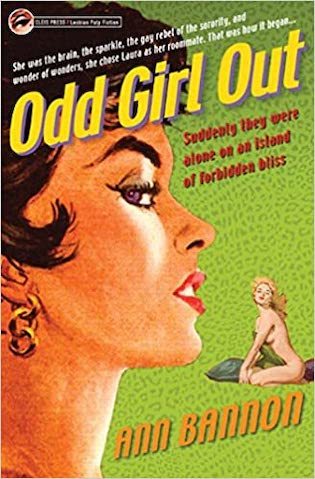

Odd Girl Out by Ann Bannon (Ann Weldy, 1957)

Odd Girl Out by Ann Bannon (the pseudonym of Ann Weldy), came a bit later in the group of the influential and enduring lesbian pulp novels of the 1950s. Odd Girl Out was the first of what became The Beebo Brinker Chronicles: five linked novels from 1957 to 1962, following the same character, Laura, into maturity. Weldy was a very unlikely pioneer of lesbian fiction. She recalled:

“I must have been the most naïve kid who ever sat down at the age of 22 to write a novel. I was a young housewife living in the suburbs of Philadelphia, college graduation just behind me, and utterly unschooled in the ways of the world… To my continuing astonishment, the books have developed a life of their own. They were born in the hostile era of McCarthyism and rigid male/female sex roles, yet still speak to readers in the twenty-first century.” More about Odd Girl Out.

Other notable titles in 20th-Century Lesbian LiteratureDusty Answer by Rosamond Lehmann (1927)Nightwood by Djuna Barnes (1937)The Friendly Young Ladies by Mary Renault (1944)Olivia by Dorothy Strachey (1949)The post 6 Classic Early- to Mid-20th Century Lesbian Novels appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Odd Girl Out by Ann Bannon (Ann Weldy), 1957

Odd Girl Out by Ann Bannon (the pseudonym of Ann Weldy), was one of several hugely influential lesbian pulp novels of the 1950s. This appreciation and analysis is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

In the introduction to her anthology Lesbian Pulp Fiction, the author Katherine V. Forrest remembers how a book she found in a bookshop in Detroit in 1957 changed not only her writing but her life:

“Overwhelming need led me to walk a gauntlet of fear up to the cash register. Fear so intense that I remembered nothing more, only that I stumbled out of the store in possession of what I knew I must have, a book as necessary to me as air. The book was Odd Girl Out by Ann Bannon. I found it when I was eighteen years old. It opened the door to my soul and told me who I was. It led me to other books that told me who some of us were, and how some of us lived.

Finding this book back then, and what it meant to me, is my touchstone to our literature, to its value and meaning. Yet no matter how many times I try to write or talk about that day in Detroit, I cannot convey the power of what it was like. You had to be there. I write my books out of the profound wish that no one will ever have to be there again.”

Bannon was really Anne Weldy; she had the same editor, Dick Carroll, and the same publisher, Gold Medal Books, as Vin Packer/Marijane Meaker, author of Spring Fire. As Bannon had changed Forrest’s life, so Meaker had changed Bannon/Weldy’s.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

Girls in Bloom on Amazon UK*

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

Weldy had been in a sorority at college like the characters in Spring Fire and thought she could write a similar kind of novel. She wrote Meaker “a kind of a fan letter.” Even though Meaker had been getting hundreds of fan letters she responded, inviting Bannon to meet her and Carroll, who looked at her novel and saw both problems and promise in it.

“In the view of Dick Carroll, the twinkly old Irishman who was running that show, the manuscript was twice as long as they wanted. He also felt that I hadn’t recognized my story. I had told a kind of straightforward coming of age type novel, and rather cautiously and timidly put a small romance between two young women in the corners of the background. He said cut the length by half and tell the story of the two young women, Beth and Laura, and then maybe we’ll have something.”

Unlike Meaker, Weldy was allowed to write the ending she wanted. In a later interview she said that Meaker “was constrained very heavily in having to end her book on a very negative note. Writing five years later, I found things had loosened up. I was able to, in a sense, have a happy ending.”

Weldy told the same interviewer how difficult life was for homosexuals and lesbians in the early 1950s, in the middle of the Cold War, the McCarthyite anti-communist witch hunts and the paranoia that surrounded them.

“It was a very repressed and frightening time. After World War Two ended, the country had made a frightening turn and embraced the most conservative and traditional roles. All the girls were supposed to be home having babies and making soup and casseroles. Everyone was supposed to be as conventional as is possible to imagine.

People whose nature led them to a same-sex attraction were forced to put up a conventional façade. The danger was very severe, and gay attraction was frankly illegal in a lot of places. You could be jailed, you could certainly be publicly humiliated and everything could be thrown into jeopardy in terms of your job and your family.

You were treated almost as if you had a disease, and if you were known to be gay then your friends had to abandon you because they might catch it too.”

Marijane Meaker put it in a very similar way in a later introduction to a reprint of We Walk Alone.

“In the 50s, we felt no entitlement, and most of us were wary of any organizations. The 50s was famous for its witch-hunts and congressional investigations. In the eyes of the law we were illegal, and religions viewed us as anathema. I wanted to write about what it was like to live in one of the most sophisticated cities in the world, and find yourself unacceptable because of your sexual orientation.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Ann Bannon (Ann Weldy) in 1983

. . . . . . . . . .

Odd Girl Out was the first of what became The Beebo Brinker Chronicles: five linked novels from 1957 to 1962, of which the second, I Am a Woman, 1959 and third, Women in the Shadows 1959, follow the same character, Laura into maturity. But Weldy was a very unlikely pioneer of lesbian fiction.

“I must have been the most naïve kid who ever sat down at the age of 22 to write a novel. It was the mid-1950s. Not only was I fresh from a sheltered upbringing in a small town, I had chosen a topic of which I had literally no practical experience.

I was a young housewife living in the suburbs of Philadelphia, college graduation just behind me, and utterly unschooled in the ways of the world… To my continuing astonishment, the books have developed a life of their own. They were born in the hostile era of McCarthyism and rigid male/female sex roles, yet still speak to readers in the twenty-first century.”

Originally introduced to it by Marijane Meaker, Weldy spent time in New York’s Greenwich Village. “It was love at first sight. Every pair of women sauntering along with arms around waists or holding hands was an inspiration.”

Odd Girl Out: A brief synopsis

Weldy’s debt to Meaker extends to the plot of Odd Girl Out, which, like Spring Fire, concerns an inexperienced girl, Laura, going to college and falling in love with an older member of her sorority, Beth, but being unsure what her feelings mean and what to do about them.

“There was a vague, strange feeling in the younger girl that to get too close to Beth was to worship her, and to worship was to get hurt.” Beth is a larger-than-life character; Laura “had never met or read or dreamed a Beth before.” One of Beth’s eccentricities is that she never wears underwear. Laura’s “whole upbringing revolted at this… Nobody was a more rigid conformist, farther from a character, than Laura Landon.”

Sharing a room together, Laura is very shy about getting undressed in front of another person, feeling that “Beth’s bright eyes were doting on every button.” Beth makes up the bed for her.

“She helped Laura under the covers and tucked her in, and it was so lovely to let herself be cared for that Laura lay still, enjoying it like a child. When Beth was about to leave her, Laura reached for her naturally, like a little girl expecting a good-night kiss. Beth bent over and said, ‘what is it, honey?’

With a hard shock of realization, Laura stopped herself. She pulled her hands away from Beth and clutched the covers with them.

‘Nothing.’ It was a small voice.

Beth pushed Laura’s hair back and gazed at her and for a heart-stopping moment Laura thought she would lean down and kiss her forehead. But she only said, ‘Okay. Sleep tight, honey.’ And climbed down.”

Laura knows nothing of lesbianism and is simply “fuzzily aware of certain extraordinary emotions that were generally frowned upon and so she frowned upon them too, with no very good notion of what they were or how they happened, and not the remotest thought that they could happen to her.”

She had had crushes on girls in high school but “they were all short and uncertain and secret feelings and she would have been profoundly shocked to hear them called homosexual.” Laura of course considers herself normal even though she “wasn’t attracted to men. She thought simply that men were unnecessary to her. That wasn’t unusual; lots of women live without men.”

Like Mitch in Spring Fire, Laura has to fight off the unwanted attentions of a boy from college who will not take no for an answer; in this case he does not go so far as to rape her, but still, like Mitch, her first experience with a boy is very bad.

Also like Mitch, Laura’s love object Beth has a boyfriend; Laura, as she begins to understand her true nature – as she comes of age – knows she has to give Beth up to him; “you need a man, you always did.”

“‘I’m not wrong about myself, not any more. And not about you, either.’

‘Oh, Laura, my dear –’

‘We haven’t time for tears now, Beth. I’ve grown up emotionally as far as I can. But you can go farther, you can be better than that. And you must, Beth, if you can. I’ve no right to hold you back.’ Her heart shrank inside her at her own words…

‘You taught me what I am, Beth. I know now, I didn’t before. I understand what I am, finally.’”

. . . . . . . . .

Odd Girl Out on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Odd Girl Out by Ann Bannon (Ann Weldy), 1957 appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 22, 2021

Margaret C. Anderson, Founder of The Little Review

Margaret C. Anderson (November 24, 1886 – October 18, 1973) was a daring, headstrong writer, editor, and founder of the modernist literary magazine, The Little Review. This modernist journal, published from 1914 to 1929, was dedicated to the best writing and art of the early twentieth century.

Margaret was later known as one of “The Women of the Rope,” a group of writers and artists who studied with the famous Russian mystic Gurdjieff, part of a group seeking transformation and possible enlightenment.

Early life and escape to ChicagoMargaret was born in Indianapolis, Indiana to Arthur Anderson and Jessie Shortridge. The oldest of three girls in an upper-middle-class family, she grew up in a bourgeois household from which she was eager to escape.

She studied at Western College for Women in Oxford Ohio, and afterward convinced her family to allow her to go to Chicago with her sister. Chicago, a bustling city, was so different from Indianapolis, and Margaret loved it. She spent her allowance on coffee, chocolate, and fine clothes.

She bought flowers, books, and beautiful furniture; she attended concerts and performances with the best seats in the house. There were performances of Mary Garden, Isadora Duncan, Arturo Toscanini, and others that opened Margaret’s consciousness to the highest aspirations in art.

Clara Laughlin, a well-known writer and editor, gave Margaret her first writing job. She started meeting writers, artists, anarchists, and bohemians who lived for art and ideas. Her dream came crashing down when her parents demanded that she move her back to Indiana because she was spending all their money. Margaret argued, and her parents finally consented to let her move back to Chicago if she could support herself.

Margaret found work at The Dial magazine, but eventually grew restless and depressed. She knew she needed inspiration. That’s when the idea of a journal dedicated to all the arts came to her. Hers would be a life of service to the highest literature and beauty.

The Little Review was launched in 1914, headquartered in the beautiful Chicago Fine Arts building with many obstacles — not the least of which was finding funding and help in getting it published. After publishing writings in praise of Emma Goldman, the controversial anarchist and feminist, Margaret lost backers and funding.

Margaret never compromised and became resourceful. She convinced her sister to live with her on the shores of Lake Michigan in tents with wooden floors. Writers and artists would pin their works on the tent flaps if they weren’t home. Margaret and her sister swam in the mornings, then drink coffee and have breakfast on the beach. They camped on the shores until November when the cold rains came.

. . . . . . . . .

Margaret C. Anderson, 1930 (photo by Man Ray)

. . . . . . . . . .

Jane Heap, a talented cross-dressing artist, joined the staff of The Little Review. She had short hair, dressed like Oscar Wilde, and had the wit to match. Margaret was enthralled when she met her; it felt like destiny, and they became lovers. Jane helped edit the journal; she and Margaret were different, yet they complemented each other.

Margaret had found the one person that understood her ideas. She felt Jane had an incredible mind and utilized it for The Little Review. They discussed and argued ideas, chiefly about art. Margaret found a wick for her flame and Jane sent her ablaze with new energy. The two women had high standards for what they would publish in The Little Review. For one issue, they weren’t happy with the submissions, so they published 64 pages of blank white paper.

Many prominent writers such as Carl Sandburg, T.S Eliot, Ezra Pound contributed their writings to The Little Review for no payment. Some of the notable women who contributed to The Little Review include Djuna Barnes, Gertrude Stein, Mina Loy, and Dorothy Richardson, among many others.

. . . . . . . . . .

Jane Heap (photo by Berenice Abbot)

. . . . . . . . . .

In 1917, the expatriate poet Ezra Pound joined The Little Review. He was able to get contributions from writers such as Aldous Huxley, William Butler Yeats, James Joyce, among others. Margaret and Jane loved Joyce’s Ulysses and published segments of the novel in the magazine from 1918 to 1920. America wasn’t ready for Joyce, which led to a charged of obscenity.

Margaret and Jane didn’t worry about censors and felt Ulysses should be published for its innovative stream of consciousness technique. Margaret recognized the genius in Ulysses and tried to battle what she felt was the public’s ignorance. She grew discouraged with people who had no taste for beauty.

Women of the Rope

After editing and publishing The Little Review for eleven years, Margaret eventually left, exhausted from the fight to publish great literature. Jane Heap became the sole editor and writer for many years.

Margaret moved to France with the singer Georgette Le Blanc. They struck up a tremendous friendship and became lovers. Georgette was the former mistress of the writer Maurice Maeterlinck, author of The Blue Bird.

Margaret, Georgette, and later Jane became part of a group known as The Women of the Rope. These were woman writers and artists searching for enlightenment by studying the teachings of the great mystic G. I. Gurdjieff in Paris and Fontainebleau France. Other members included Solita Solano, Kathryn Hulme, Alice Roher, and Elizabeth Gordon.

Gurdjieff’s teachings seemed to appeal to women artists. He could be very strict but had a sly sense of humor. Solita Salano had written a detailed, fascinating book about their experience with the famous mystic called Gurdjieff and the Woman of the Rope: Notes of meetings in Paris and New York.

“You are going on a journey under my guidance, an inner-world journey like a high mountain climb where you must be roped together for safety, where each must think of the others on the rope, all for one and one for all.” (— Gurdjieff And The Women Of The Rope)