Nava Atlas's Blog, page 45

March 1, 2021

Susanna Centlivre, English Poet and Playwright

This introduction to Susanna Centlivre (1669 – 1723), the English poet, playwright, and actress, is excerpted from Killing the Angel: Early British Transgressive Women Writers ©2021 by Francis Booth. Reprinted by permission:

Very much as Virginia Woolf wrote about Aphra Behn, the anonymous author of the introduction to Susanna Centlivre’s collected works wished that Centlivre had been buried as a national treasure in Westminster Abbey.

To entertain this bustling busy Age,

Our Author now brings Business on the Stage;

She plots, contrives, embroils, foments Confusion,

And yet to Politicks makes not the least Allusion.

— Susanna Centlivre, Prologue to The Perplex’d Lovers

A prolific & successful female playwright

Aphra Behn’s reputation was, as Woolf said, a major bar to later women making a living as a playwright but not a complete one: the poet, actor and prolific playwright Susanna Centlivre, née Freeman and known professionally as Susanna Carroll, was said to be financially the most successful female playwright of the eighteenth century, even more than Behn herself.

Be it known that the Person with Pen in Hand is no other than a Woman, not a little piqued to find that neither the Nobility nor Commonalty of the Year 1722, had Spirit enough to erect in Westminster Abbey, a monument justly due to the Manes of the never to be forgotten Mrs Centlivre.

Between 1700 and 1723 she wrote nineteen plays, some of which had long and successful stage careers. In the preface to her most successful play The Busie Body, 1709, Centlivre respectfully addresses the Lord President of the Privy council, as was customary and she does it with the customary combination of self-deprecation and grovelling.

May it please Your Lordship,

As it’s an Established Custom in these latter Ages, for all Writers, particularly the Poetical, to shelter their Productions under the Protection of the most Distinguished, whose Approbation produces a kind of Inspiration, much superior to that which the Heathenish Poets pretended to derive from their Fictitious Apollo: So it was my Ambition to Address one of my weak Performances to Your Lordship, who, by Universal Consent, are justly allowed to be the best Judge of all kinds of Writing.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

However, towards the end of all this obsequiousness Centlivre suddenly switches tack, pleading feminine inadequacies, implying that all the foregoing had perhaps been intended ironically and that she is here slyly transgressing the norms of these fawning dedications to pompous men.

And here, my Lord, the Occasion seems fair for me to engage in a Panegyric upon those Natural and Acquired Abilities, which so brightly Adorn your Person: But I shall resist that Temptation, being conscious of the Inequality of a Female Pen to so Masculine an Attempt; and having no other Ambition, than to Subscribe myself, My Lord,

Your Lordship’s Most Humble and

Most Obedient Servant,

Susanna Centlivre.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Killing the Angel on Amazon US*

Killing the Angel on Amazon UK*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Not much is known about Centlivre’s early life but it is likely that her father died early, her mother remarried, then also died, after which stepfather died too. She probably then left home to join a company of strolling actors at around the age of fifteen, playing breeches roles – the male parts – and marrying another actor at the age of sixteen. He died less than a year later, she married again, an army officer named Carroll, but he died in a duel year after that.

Then, while performing at Windsor Castle, she met Joseph Centlivre and married him, though he was only a cook in the Castle kitchen. This one seems to have lived rather longer than the previous two, but presumably Susanna needed the money from her writing to sustain them.

In the play The Perjur’d Husband, 1700, Centlivre playfully subverts with the conventions of male characters complaining about women; her characters say the same things about the joy of being free from women as those in male-authored plays but they can be read as ironic because they were written by a woman.

Oh! happy he

Who lives secure and free from Love’s Alarms.

But happier far, who, Master of himself,

Ranges abroad without that Clog, a Wife.

Oh! rigorous Laws imposed on Free-born Man!

On Man, by bounteous Nature first designed

The Sovereign Lord of all the Universe!

Why must his generous Passion thus be starved,

And be confined to one alone?

The Woman, whom Heaven sent as a Relief,

To ease the Burden of a tedious Life,

And be enjoyed when summoned by Desire,

Is now become the Tyrant of our Fates.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Plays continued to be performed beyond her lifetimeCentlivre’s plays continued to be popular and were performed regularly until well after her death; in 1762 her collected works were published in three volumes. However, in the introduction (written by an anonymous woman) it is made clear that audiences initially stayed away from her plays, knowing they were by a woman; only when word of mouth spread did the audiences increase.

Her play of the Busy Body, when known to be the Work of a Woman, scarce defrayed the expenses of the First Night. The thin Audience were pleased, and caused a full House the Second; the Third was crowded and so on to the Thirteenth, then it stopped, on account of the advanced season; but the following Winter successively, was acted by rival Players, both at Drury Lane, and at the Hay-Market Houses. See here the Effect of Prejudice, a Woman who did Honour to the Nation, suffered because she was a Woman. Are these things fit and becoming a free born People, who call themselves polite and civilised!

The author of the introduction is at pains to make sure that we understand the problems facing a woman writer at that time.

Some Authors have had a Shandeian Knack of ushering in their own Praises, sounding their own Trumpet, calling Absurdity Wit, and boasting when they ought to blush; but our Poetess had Modesty, the general Attendant of Merit. She was even ashamed to proclaim her own great Genius, probably because the Custom of the Times discountenanced poetical Excellence in a Female. The Gentlemen of the Quill published it not, perhaps envying her superior Talents; and her Bookseller, complying with national Prejudices, put a fictitious name to her Love’s Contrivance, through fear that the work should be condemned, if known to be Feminine.

. . . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

5 Early English Women Writers to Discover

. . . . . . . . . . .

Centlivre did blow her own trumpet on occasion though, and certainly knew the mechanics of playwriting; she refers to Aristotle’s three dramatic unities: time, space and action. Another early English author, Elizabeth Montagu, in her praise of Shakespeare, condemned French authors for sticking too closely to them.

Centlivre understands these things but also understands that audiences simply want entertainment, to suspend disbelief for an evening. In her Preface to Loves Contrivance, 1703, Centlivre makes it clear that she knows the classics but does not seek to emulate them.

Writing is a kind of Lottery in this fickle Age, and Dependence on the Stage as precarious as the Cast of a Die; the Chance may turn up, and a Man may write to please the Town, but ’tis uncertain, since we see our best Authors sometimes fail. The Critics cavil most about Decorums, and cry up Aristotle’s Rules as the most essential part of the Play. I own they are in the right of it; yet I dare venture a Wager they’ll never persuade the Town to be of their Opinion, which relishes nothing so well as Humour lightly tossed up with Wit, and dressed with Modesty and Air. . . This I dare engage, that the Town will ne’er be entertained with Plays according to the Method of the Ancients, till they exclude this Innovation of Wit and Humour, which yet I see no likelihood of doing.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Susanna Centlivre

Wikipedia List of works Reader discussion on Goodreads Encyclopedia.com. . . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Susanna Centlivre, English Poet and Playwright appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 24, 2021

Regiment of Women by Clemence Dane (1917)

This introduction to Regiment of Women (1917), a proto-lesbian novel by the pseudonymous Clemence Dane, is is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in mid-20th Century Women’s Fiction by Francis Booth, reprinted with permission:

The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall (1928 ), usually said to be the first English-language novel containing veiled lesbianism was just beaten to the title by Rosamond Lehmann’s Dusty Answer, 1927. But ten years before even that was Regiment of Women, 1917, the debut novel of Clemence Dane, the pseudonym of Winifred Ashton (1888-1965), London-born novelist, playwright, and early feminist.

Clemence Dane’s 1921 play, A Bill of Divorcement, was made into a film three times and Dane went on to write screenplays herself, including Anna Karenina, starring Greta Garbo.

. . . . . . . . .

Winifred Ashton (AKA Clemence Dane)

. . . . . . . . . . .

As she was thirty years old in 1918, Ashton was one of the first women to be allowed to vote under the new Representation of the People Act – it was not until ten years later that women aged twenty-one and over were allowed to vote. Ashton joined the Six Point Group, founded in 1921 to press for equality for women in six areas: political, occupational, moral, social, economic, and legal. In 1927, writing as Clemence Dane, she published The Women’s Side.

When conditions are evil it is not your duty to submit . . . when conditions are evil, your duty, in spite of protests, in spite of sentiment, your duty, though you trample on the bodies of your nearest and dearest to do it, though you bleed your own heart while your duty is to see that those conditions are changed.

If your laws forbid you, you must change your laws. If your church forbids you, you must change your church. And if your God forbids you, you must change your God.

. . . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon US*

Girls in Bloom on Amazon UK*

. . . . . . . .

The word ‘Regiment’ in the title Regiment of Women means ‘rule by,’ and is a reference to John Knox’s pamphlet The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women, 1558, published at the time of Queen Elizabeth I; Knox argued that rule by women was against the teachings of the Bible.

Dane’s title is obviously ironic but at least two of the book cover designers completely misunderstood the title, or more likely had not read the book: one has a picture of a woman in uniform, depicting a female member of a military regiment, and the other has a picture of a boys’ school.

Clare, Alwynne, and Louise

The two ostensible main characters of the novel are teachers at a private girls’ boarding school: Clare Hartill, in her thirties, deputy headmistress but in practice the person who runs the school, and nineteen-year-old Alwynne Durand. The two women are very close and go abroad together in the summer holidays, implying though never explicitly stating a lesbian relationship.

However, for our purposes, the most interesting character is their fourteen-year-old pupil Louise Denny, who adores Clare more even than the average boarding school girl loves a teacher, though both teachers dote on her in return. There is no explicit suggestion that their interest in Louise is sexual, though the symbolism of calyx and blossom is certainly suggestive.

Clare could be exquisitely tender, could keep all-patient vigil over an unfolding mind, provided that the calyx concealed a rare enough blossom. Louise was encouraged, her shyness swept aside, her ideas developed, her knowledge tested; she was fed, too, cautiously, on richer and richer food – stray evening lectures, picture galleries with Alwynne, headiest of cicerones; the freedom of the library and long talks with Clare.

At home, Louise had no elder sister and unsympathetic parents. When she was sent to boarding school at the age of twelve, ‘She was unaccustomed to companions of her own age and sex and, quite simply, did not know how to make friends.’ Clare’s effect on Louise is shattering; she becomes something between a goddess, a mother, and a sister.

With Clare’s intervention, the world was changed for Louise; she had her first taste of active pleasure. It is difficult to realize what an effect a woman of Clare’s temperament must have had on the impressionable child. In her knowledge, her enthusiasms, her delicate intuition, and her keen intellectual sympathy, she must have seemed the embodiment of all dreams, the fulfillment of every longing, the ideal made flesh.

A wanderer in an alien land, homesick, hungry, for whom, after weary days, a queen descends from her throne, speaking his language, supplying his unvoiced wants, might feel something of the adoring gratitude that possessed Louise. She rejoiced in Clare as a vault-bred flower in sunlight.

Both Clare and Alwynne are blissfully unaware of the impact they are having on the literally-cloistered, naive fourteen-year-old girl, though they should of course know better. Even Louise’s school friend Cynthia can see the disaster coming. Cynthia also admires Clare but not in the way that Louise does. ‘I don’t worship her like you do,’ says Cynthia.

‘I don’t! – I just love her.’ Louise glowed.

Cynthia laughed jollily. ‘Oh, well! You’ll get over that. Wait till you get a best boy.’

‘If you think I’d look at any silly man, after knowing her –’

‘My dear girl! Has it never occurred to you that you’ll marry some day?’

Louise shook her head. ‘I’ve thought it all out. I never could love anybody as much as I do Miss Hartill. I know I couldn’t.’

‘But it’s not the same! Falling in love with a man –’

‘Love’s love,’ said Louise with finality. ‘Where’s the difference?’

Cynthia knows the difference between men and women, or at least claims to. She attempts to tell Louise. ‘Shall I tell you? Would you like to know? You ought to – you’re fourteen – it’s absurd – not knowing about things – shall I tell you?’ But Louise is not interested, she is not yet ready to come of age. ‘I don’t think I want to know anything. It’s awfully sweet of you.’

And Louise, eating chocolates, was not long in forgetting the conversation and all the curious discomfort it had aroused. If a leaf had fallen on the white garment of her innocence – a leaf from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil – she had brushed it aside, all unconscious, before it could leave a stain.

No happy endings allowed

This idyll cannot last, and it doesn’t. One evening Clare has invited Louise to a very grown-up function; Louise believes she has behaved appropriately but Clare is annoyed with her. She begs Clare not to be cross.

‘I can’t bear it. It’s killing me. Couldn’t you stop being angry?’

Clare, ignoring her, wrenched open the door. Louise, flung sideways, slipped on the polished floor. She crouched where she fell, and caught at Clare’s skirts. She was completely demoralised.

‘Miss Hartill! Oh, please – please – if you would only understand. You hurt me so. You hurt me so.’

Clare stood looking down at her. ‘Once and for all, Louise, I dislike scenes. Let me go, please.’

This rejection literally tips the fragile Louise over the edge. She goes up to the top of the big old house and leans out of the window, contemplating what it would be like to fall to the ground. ‘She imagined the sensation of the impact, and shuddered. But at least they would kill one outright….’ Louise hesitates, pulls back, but then she hears a knocking at the door.

They would break open the door … They would find her … They would stop her … Coward that she was – fool and coward … One instant’s courage – one little movement!

She stiffened herself anew. Poised on the extreme edge of the outer sill, she pushed her two hands through the belt of her dress, lest they should save her in her own despite. She stood an instant, her eyes closed.

Then she sprang …

Poor Louise never lives to come of age. There were no happy endings allowed in lesbian novels for a long time after Regiment of Women.

. . . . . . . . .

More by Francis Booth on this site

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

More about Regiment of Women by Clemence Dane Review in Stuck in a Book Reader discussion on Goodreads Read Regiment of Women (full text)*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Regiment of Women by Clemence Dane (1917) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 22, 2021

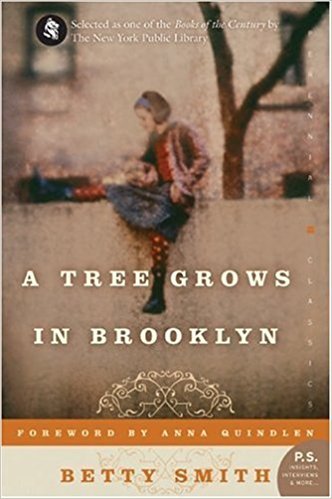

Francie Nolan: Coming of Age in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

The coming of age of a strong female protagonist was a surprisingly common theme in mid-20-century literature by women authors. At a time when women’s progress suffered setbacks, perhaps the pages of books were an outlet for repressed ambitions and desires. Francie Nolan, the gentle, relatable heroine of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith is considered in this excerpt from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in mid-20th Century Women’s Fiction by Francis Booth. Reprinted with permission:

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1943), the first published novel by Betty Smith (1896-1971) is a wonderful example of the female bildungsroman, following the central character Francie Nolan in an epic sweep from age eleven to seventeen. Beginning in summer 1912, the story centers around Francie and her Irish immigrant family, living in a Brooklyn slum where the children pick rags to make a few cents.

Learning about the world through books

Like Cassandra Mortmain of I Capture the Castle and like some other girls in this genre – Natalie Waite in Shirley Jackson’s Hangsaman is another example – Francie is perhaps unreasonably literate, even more so given her poor background. She loves the local public library.

Francie thought that all the books in the world were in that library and she had a plan about reading all the books in the world. She was reading a book a day in alphabetical order and not skipping the dry ones. She remembered that the first author had been Abbott. She had been reading a book a day for a long time now and she was still in the B’s.

Already she had read about bees and buffaloes, Bermuda vacations and Byzantine architecture. For all of her enthusiasm, she had to admit that some of the B’s had been hard going. But Francie was a reader. She read everything she could find: trash, classics, timetables and the grocer’s price list. Some of the reading had been wonderful; the Louisa May Alcott books, for example. She planned to read all the books over again when she had finished with the Z’s.

We are not told what Francie thought of Jane Austen or whether she has yet reached the Brontës. Francie lives out the metaphor of the tree growing in Brooklyn of the title, which grows outside her window. “An eleven-year-old girl sitting on this fire escape could imagine that she was living in a tree. That’s what Francie imagined every Saturday afternoon in summer.”

Her mother, who is herself only twenty-nine at the start of the story, says: “Look at that tree growing up there out of that grating. It gets no sun, and water only when it rains. It’s growing out of sour earth. And it’s strong because its hard struggle to live is making it strong. My children will be strong that way.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

And Francie is strong that way. She thrives at school, and particularly loves her school supplies: “a notebook and tablet and a pencil box with a sliding top filled with new pencils, an eraser, a little tin pencil sharpener made in the shape of a cannon, a pen wiper, and a six-inch, softwood, yellow ruler.”

In a long flashback to when Francie is younger and just starting school, the magic of the discovery of reading and the worlds to which it gives even the poorest girl access, is beautifully captured.

Oh, magic hour when a child first knows it can read printed words!

For quite a while, Francie had been spelling out letters, sounding them and then putting the sounds together to mean a word. But one day, she looked at a page and the word ‘mouse’ had instantaneous meaning. She looked at the word and the picture of a grey mouse scampered through her mind… She read a few pages rapidly and almost became ill with excitement. She wanted to shout it out. She could read! She could read!

From that time on, the world was hers for the reading. She would never be lonely again, never miss the lack of intimate friends. Books became her friends and there was one for every mood. There was poetry for quiet companionship. There was adventure when she tired of quiet hours. There would be love stories when she came into adolescence and when she wanted to feel a closeness to someone she could read a biography. On that day when she first knew she could read, she made a vow to read one book a day as long as she lived.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith

. . . . . . . . . .

Francie keeps a diary, like many girls in this genre. One day, when she is thirteen she writes: “Today, I am a woman.” It’s not clear whether this is because her periods have started. “She looked down on her long thin and as yet formless legs. She crossed out the sentence and started over. ‘Soon, I shall become a woman.’ She looked down on her chest which was as flat as a wash board and ripped the page out of the book. She started fresh on a new page.”

That same Saturday she sees her name in print for the first time, a story of hers having been printed in the school magazine as the best story in her composition class. But her composition teacher looks down on her family and her way of life and consequently looks down on the stories that Francie writes about them.

“I honestly believe that you have promise. Now that we’ve talked things out, I’m sure you will stop writing those sordid little stories.” Francie is appalled to be called sordid: she loves her mother and father, who do their best for her and her brother. She uncharacteristically lashes out at her teacher. “Don’t you ever dare use that word about us!”

Francie has plans to publish the book when it is finished and has even worked out in her mind a fantasy of the dialogue she will have with her delighted teacher when she sees it. “It was such a rosy dream that Francie started the next chapter in a fever of excitement. She’d write and write and get it done quickly so the dream could come true.”

But there is no food in the apartment, just some stale bread and she can hardly write for hunger. Reading what she has written, she realizes that she has been simply inverting her own poverty: she is writing about a heroine spoilt by a surfeit of rich food because her own hunger has made her obsessed.

Furious with the novel, she ripped the copy-book apart and stuffed it into the stove. When the flames began licking on it, her fury increased and she ran and got her box of manuscripts from under her bed … She was burning all her pretty “A” compositions.’

. . . . . . . . .

How Betty Smith Came to Write A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

. . . . . . . . .

After her father dies, Francie’s mother cannot afford for both her and her brother to go to school and favors the boy. Francie starts working in a factory at the age of fourteen, lying about her age to make herself older so that she can get a job. Soon, though, she improves her situation enormously, working as a reader in a newspaper office and earning what by her family’s standards is an enormous amount of money while reading for a living.

Even after she loses this job, she falls on her feet and gets a job working a teletype. “She thought it a wonderful miracle that she could sit at that machine and type and have the words come out hundreds of miles away.’” She works the night shift which takes care of her “lonely evenings,” and allows her to sit outside in the sun during the day. Francie is still only fifteen. Her mother suggests that she could go to college while working the night shift.

But what in the world could I learn in high school now? Oh, I’m not conceited or anything, but after all, I read eight hours a day for almost a year and I learned things. I got my own ideas about history and government and geography and writing and poetry. I read too much about people – what they do and how they live. I’ve read about crimes and about heroic things.

Mama, I’ve read about everything. I couldn’t sit still now in a classroom with a bunch of baby kids and listen to an old maid teacher drool away about this and that. I’d be jumping up and correcting her all the time. Or else, I’d be good and swallow it all down and then I’d hate myself for . . . well, . . . eating mush instead of bread. So I will not go to high school. But I will go to college some day.

. . . . . . . . . .

More by Francis Booth on this site

. . . . . . . . . .

When Francie is sixteen, she meets Lee, a soldier who is about to go off to the war – this is 1917. He admits she means nothing to him but tries to persuade Francie to spend the night with him. She resists but promises to write to him every day while he is away and marry him when he comes back. And if he doesn’t come back she promises never to marry, or even kiss anyone else.

“And he asked for her whole life as simply as he’d ask for a date. And she promised away her whole life as simply as she’d offer a hand in greeting or farewell.”

Soon afterward, Francie gets a letter from Lee’s mother thanking her for being a good friend to him while he was in New York and telling her that Lee has got married. “I read the letter you sent Lee. It was mean of him to pretend to be in love with you and I told him so. He said to tell you he’s dreadfully sorry.” Francie confides in her mother, Katie.

“Mother, he asked me to be with him for the night. Should I have gone?”

Katie’s mind darted around looking for works.

“Don’t make up a lie, Mother. Tell me the truth.”

Katie couldn’t find the right words.

“I promise you that I’ll never go with a man without being married first – if I ever marry. And if I feel that I must – without being married, I’ll tell you first. That’s a solemn promise. So you can tell me the truth without worrying that I’ll go wrong if I know it.”

“There are two truths,” said Katie finally.

“As a mother, I say it would have been a terrible thing for a girl to sleep with the stranger – a man she had known less than forty-eight hours. Horrible things might have happened to you. Your whole life might have been ruined. As a mother, I tell you the truth.

“But as a mother …” she hesitated. “I will tell you the truth as a woman. It would have been a very beautiful thing. Because there is only once that you love that way.”

Francie thought, “I should have gone with him then. I’ll never love anyone as much again. I wanted to go and I didn’t go and now I don’t want him that way anymore because she owns him now. But I wanted to and I didn’t and now it’s too late.”

She put her head down on the table and wept.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Francie Nolan: Coming of Age in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 19, 2021

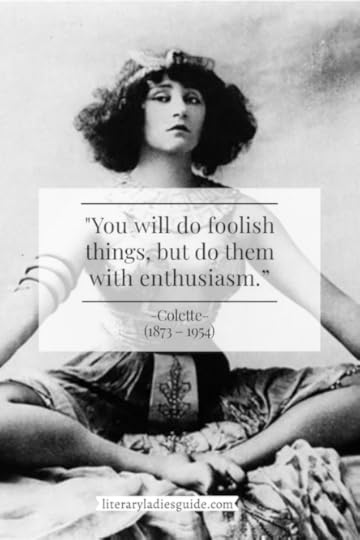

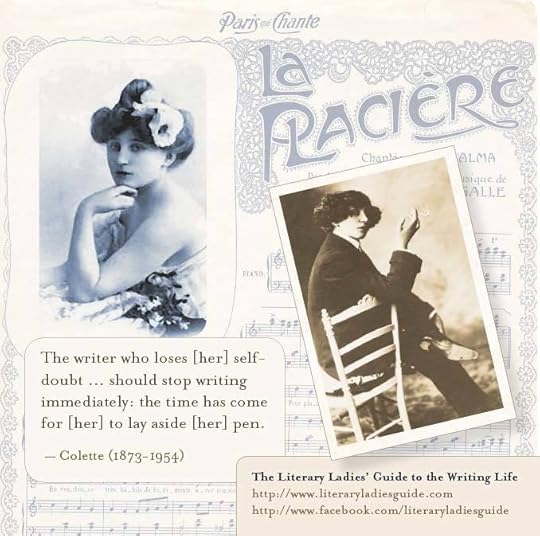

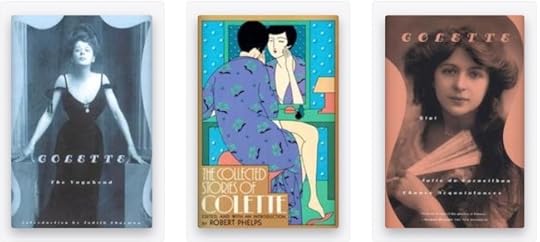

Merci, Colette: How the Legendary French Author Continues to Inspire

This heartwarming essay by Tyler Scott is an homage to Colette (1873 – 1954), the bold and fearless French author, and discusses how she continues to inspire writers at any stage of practice:

In the fraught year of 2020, I had been too addled and worried to write very much. After a career as a freelancer, I started to wonder if things had ground to a halt. Was this the end of the line for me? After all that work? All that research? All those accolades? As Claudia Emerson, the late Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and onetime classmate told me, “Sometimes it’s just easier to quit.”

So, what opened my eyes, jolted my imagination, made me grab a pen and pick up my dusty journal? Colette. Thanks to a famous French author, I am writing again for the first time in months.

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Colette

. . . . . . . . .

How would a belletrist most people in the United States have never heard of help me heal? Because her prose is voluptuous, wistful, and sometimes saucy and when I read her, she reminds me to slow down, study, and take more pains with my writing. To paint with words layer by layer.

I may look out my dining room window and see a bed of green moss yet with her ghostly hand guiding me, I realize the moss is greyish, forlorn, and striped with sunlight. And look! The mayor next door is heading to work at the newspaper (I live in a small town where people wear several hats). And why is Mr. So-and-So walking his retriever so quickly this morning? Is it really that cold?

A writer like Colette encourages you to take the extra step and look for the art in the scenery as well as the people. Find the beauty in the simple and the simple in the beauty. Our world is a prism of detail.

Discovering Colette in Paris

Like many Southern girls way back when (I am a woman of a certain age), my parents sent me on Junior Year Abroad in 1977 to learn a language, broaden my horizons, and learn some Old-World etiquette. I chose Paris.

In my French program, I had a chic teacher named Pascal who one day assigned a passage from Colette as well as a pastiche. I had never heard of either and can’t remember what we read, but whatever it was, the floodgates opened. Colette has influenced me ever since. Her prose = poetry.

“Always up at dawn and sometimes before day, my mother attached particular importance to the cardinal points of the compass, as much for the good as for the harm they might bring. It is because of her and my deep-rooted love for her that first thing every morning, and while I am still snug in bed, I always ask: ‘Where is the wind coming from?’ only to be told in reply: ‘It’s a lovely day,’ or ‘The Palais-Royal’s full of sparrows,’ or ‘The weather’s vile’ or ‘seasonable.’ So nowadays I must rely on myself for the answer, by watching which way a cloud is moving, listening for ocean rumblings in the chimney.” (From Sido, Colette’s tribute to her mother)

. . . . . . . . . .

Secrets of the Flesh, a Life of Colette

. . . . . . . . . .

Sidonie Gabrielle Colette was born in 1873 in Saint-Sauveur-en-Puisaye in Burgundy. Daughter of a retired soldier and politician and a strong-willed mother, she was a typical mischievous girl turned loose with her friends and family in the countryside, all of which would play major roles in her writing.

Her style was distinct, discreet: remember: she was a product of La Belle Epoque. I recommend Judith Thurman’s biography, Secrets of the Flesh, a Life of Colette, for an excellent overview of this remarkable woman’s life.

Colette was prolific – she created about 80 works, including books, reportage, plays, short stories, essays, movie scripts, criticism, a libretto for Ravel – a veritable library. A feminist who often wrote autobiographically, Colette did not shy away from sexual themes, to borrow from Tolstoy, she wrote about “man’s most tormenting tragedy – the tragedy of the bedroom” – all with Mother Nature as a backdrop.

At twenty, she was swept off her feet by an older boulevardier from Paris, Henri Gauthier-Villars, Willy, who was also a publisher, editor and managed a stable of ghostwriters writing potboilers. During their early years together, Willy figured that Colette had entertaining schoolgirl tales, so he had her write them down, being sure to add some spice.

. . . . . . . . .

How Colette Came to Write the Claudine Stories

. . . . . . . . .

Thus, was born the Claudine series: Claudine at School; Claudine in Paris; Claudine Married; and Claudine and Annie, all bestsellers. The bad news was these books were published under Willy’s name, not to mention he also locked Colette in her room so she would toil away – after all he was making money off her talent and his editing. (“And that is how I became a writer,” she once recalled.) In 1904 she published Dialogue des Bêtes under her husband’s pen name Colette Willy.

Two years later, miserable, fed up with his philandering, she finally divorced Willy and struck out on her own, publishing La Retraite Sentimentale under her surname. The following years gave her plenty of material: a career in musical theater; affairs with both sexes; another marriage to the editor in chief of the newspaper Le Matin; an affair with her stepson (!); two world wars; motherhood late in life; opening two beauty shops; receiving the Legion of Honor and Prix de Goncourt; and enduring the Nazis in Occupied Paris with her Jewish third husband who was interred for a period.

Colette wrote her novel, Gigi, in 1944 and later chose an unknown actress named Audrey Hepburn to star in the Broadway adaption in 1951.

The Vagabond, Cheri, The Last of Cheri, The Tender Shoot and Other Stories are some of my favorite tomes as well as editor and translator Robert Phelps’s Earthly Paradise, where he pieced together parts of her prose to tell her autobiography. This was the first book I bought of Colette’s and my copy is so well-worn that the dust jacket is in four pieces and I use them as bookmarks. I don’t think there is such thing as a bad book by Colette. She was masterful and if the truth be known, her writing is so smooth and heady she is one of the few writers I can read before I go to sleep. The style is a true lull of words, a song.

Colette gives writers a sense of hope

“To write, to be able to write, what does that mean? It means spending long hours dreaming before a white page, scribbling unconsciously, letting your pen play round a blot of ink and nibble at a half-formed word, scratching it, making it bristle with darts and adorning it with antennae and paws until it loses all resemblance to a legible word and turns into a fantastic insect or a fluttering creature, half butterfly, half fairy.” (From The Vagabond, a story of a young woman who is torn between love, independence, and art)

A writer like Colette gives us a sense of hope and pride and after such a tough and sad year as 2020 was, I think all of us need rejuvenation. Moreover, I understand why, long ago, my teacher assigned the reading and pastiche; Colette’s style is descriptive and easy to imitate and I think writing bad Colette is better than not writing at all.

Nowadays, I read her in English and the translations are excellent. Given she was penning a century ago, she had a rich vocabulary, so I usually keep a list of words I don’t know. Words like superannuated, Ortolan, and melopoeia are building blocks and I’ve always had the rule that each time I write an article, I must use a new word.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Colette’s advice to writersHow does else does Colette influence me? She wrote until her last days, even though she was bedridden and crippled with arthritis and she never let poverty, heartbreak, war, an abusive husband, celebrity, motherhood, or bad health get in the way of her trade. This reminds me not to turn into a wannabe who talks about writing more than she writes.

She had many key words of advice:

“Writing only leads to more writing.”“Look long and hard at the things that please you, even longer and harder at what causes you pain.”“Sit down and put down everything that comes into your head and then you’re a writer. But an author is one who can judge one’s own stuff’s worth, without pity, and destroy most of it.”“Nobody asked you to be happy. Work. Do you hear me complaining?”And my favorite:

“Hope costs nothing.”Next time you hit a wall in your writing, choose a book from one of your favorite authors. Peruse, take notes, read and revel: remember these writers suffered most of the same challenges you and I have. Dry spells, penury, distractions, too many responsibilities, family and friends who rolled their eyes and patted us on our shoulders, enough rejection to paper a bedroom wall. Turning to a favorite wordsmith for guidance is a lot cheaper than therapy.

The death of a legend, and a legacyOn August 3, 1954, Colette, after a sip of champagne, died at her apartment in Palais Royale. She was, as ever, surrounded by her beloved cats. The onetime schoolgirl from Burgundy had become a beloved national treasure with the same stature as Proust and considered a female Montaigne.

Because of her two divorces, the Catholic Church denied her a Christian burial, but France had other ideas. She was given a state funeral with full honors, the first for a woman, and buried with much pomp and respect. A kind soul mounted this plaque on a wall in her garden: Ici vecut, ici mourut Colette, dont l’oeuvre est est une fenetre grande ouverte sur la vie. (Here lived, here died Colette, whose work is a window wide-open on life.)

Many years ago, my husband and I owned a sailboat, a 29-foot sloop, sails trimmed in navy blue, teak interior, dingy dragging along behind. When I close my eyes, I see the boat cutting through the choppy waves of the Chesapeake Bay and I hear the sounds of happiness from family and friends, all under a beamy sun and watchful seagulls. We were surrounded by nature and joy, memories we all hold so dear now.

The name of the sailboat was Colette.

Contributed by Tyler Scott. Tyler lives in Blackstone, Virginia with her husband and Norfolk Terrier. Her essays and articles have appeared in numerous magazines and newspapers and her novel The Excellent Advice of a Few Famous Painters* is available on Amazon.

Sources

Introduction, My Mother’s House & Sido, The Modern Library, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, Inc., New York, 1995.Earthly Paradise, An Autobiography, compiled by Robert Phelps, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, Inc., New York, 1966.Introduction, Short Novels of Colette, The Dial Press, New York, 1951.

Books by Colette on Bookshop.org*

Colette page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Merci, Colette: How the Legendary French Author Continues to Inspire appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 15, 2021

The Scandalous, Sexually Explicit Writings of Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn (1640 – 1689), was far ahead of her time as the first Englishwoman to earn a living by the pen as a playwright, poet, and novelist. She was also considered scandalous not just for thriving in a profession generally closed to women, but for the sexually explicit nature of her writing. This aspect of her artistry is explored in this excerpt from Killing the Angel: Early British Transgressive Women Writers ©2021 by Francis Booth. Reprinted by permission:

In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf espoused Aphra Behn’s cause as the great precursor of free women writers — though the first book in English was written by Julian of Norwich, the first autobiography was written by Margery Kempe, the first playwright and female poet since antiquity was Hrotsvitha and the first professional woman writer was probably Christine of Pizan.

“All women together ought to let flowers fall upon the tomb of Aphra Behn which is, most scandalously but rather appropriately, in Westminster Abbey, for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Aphra Behn

. . . . . . . . . .

Woolf argued that it was not the fact that Behn succeeded artistically that was her transgression, but the fact that she succeeded commercially. Because of this, rather than helping the women writers who followed her, Behn may have made it worse for them precisely because of her public transgressiveness, not just as a writer but as a woman.

Aphra Behn . . . made, by working very hard, enough to live on. The importance of that fact outweighs anything that she actually wrote . . . for here begins the freedom of the mind, or rather the possibility that in the course of time the mind will be free to write what it likes. For now that Aphra Behn had done it, girls could go to their parents and say, You need not give me an allowance; I can make money by my pen. Of course the answer for many years to come was, Yes, by living the life of Aphra Behn! Death would be better!

The reason for the parents’ horror would have been Behn’s very public views on free sexual relations for both men and women. She was not only a friend of the poet John Dryden but of the notorious libertine John Wilmot, Lord Rochester; that friendship alone would have ruined her reputation.

. . . . . . . . . .

Killing the Angel on Amazon US*

Killing the Angel on Amazon UK*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Behn wrote quite freely about sex: her poem The Disappointment is very explicit and concerns male impotence, a highly transgressive theme for a woman, then and now.

He saw how at her length she lay,

He saw her rising Bosom bare,

Her loose thin Robes, through which appear

A Shape design’d for Love and Play;

Abandon’d by her Pride and Shame,

She do’s her softest Sweets dispense,

Offering her Virgin-Innocence

A Victim to Loves Sacred Flame ;

Whilst th’ or’e ravish’d Shepherd lies,

Unable to perform the Sacrifice.

In this so Am’rous cruel strife,

Where Love and Fate were too severe,

The poor Lisander in Despair,

Renounc’d his Reason with his Life.

Now all the Brisk and Active Fire

That should the Nobler Part inflame,

Unactive Frigid, Dull became,

And left no Spark for new Desire ;

Not all her Naked Charms could move,

Or calm that Rage that had debauch’d his Love.

Writing as Astrea

Subsequent generations were even more prudish than Behn’s and were generally unkind to Behn’s transgressiveness: Alexander Pope said of her, “The stage how loosely does Astrea tread, Who fairly puts all characters to bed!”

Behn wrote her scandalous, sex-filled plays under a pseudonym – Astrea – as did many of her contemporaries and successors (often beginning with A: Anne Finch called herself Ardelia and George Sand used the name Aurore); it would be a long time before transgressive women writers published under their own name. Some women published works with no name at all attached; as Virginia Woolf said, ‘I would venture to guess that Anonymous, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.’

Love Letters Between a Nobleman and his Sister (1684)

Behn’s novels were as sexually frank as her plays. In Love Letters Between a Nobleman and his Sister (1684) – a transgressive title in itself – first printed anonymously, innocent young Silvia has given herself to Philander (the clue is in his name, Silvia) and now regrets it. Her letter to him is highly erotic; Behn as Silvia is here transgressing the bounds of what an ‘innocent’ young girl is supposed to say. This is one of the first descriptions of a woman’s sexual desires to be published by a woman since Margery Kempe and far more explicit.

I own, for I may own it, now heaven and you are witness of my shame, I own with all this love, with all this passion, so vast, so true, and so unchangeable, that I have wishes, new, unwonted wishes, at every thought of thee I find a strange disorder in my blood, that pants and burns in every vein, and makes me blush, and sigh, and grow impatient . . .

What though I lay extended on my bed, undressed, unapprehensive of my fate, my bosom loose and easy of access, my garments ready, thin and wantonly put on, as if they would with little force submit to the fond straying hand: what then, Philander, must you take the advantage?

Must you be perjured because I was tempting? It is true, I let you in by stealth by night, whose silent darkness favoured your treachery; but oh, Philander, were not your vows as binding by a glimmering taper, as if the sun with all his awful light had been a looker on? I urged your vows as you pressed on, – but oh, I fear it was in such a way, so faintly and so feebly I upbraided you, as did but more advance your perjuries.

Your strength increas’d, but mine alas declin’d; ‘till I quite fainted in your arms, left you triumphant lord of all: no more my faint denials do persuade, no more my trembling hands resist your force, unregarded lay the treasure which you toil’d for, betrayed and yielded to the lovely conqueror– but oh tormenting, – when you saw the store, and found the prize no richer, with what contempt, (yes false, dear man) with what contempt you view’d the unvalu’d trophy: what, despised!

Having had his way with Silvia, Philander immediately treats her with contempt; Behn writes of this as if from personal experience. It is easy to see why her frankness would upset the parents of aspiring female authors.

. . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

5 Early English Women Writers to Discover

. . . . . . . . .

But Behn’s transgressiveness was not only in relation to sex: her late novel Oroonoko (1688) is critical of both colonialism and slavery and is sympathetic towards its eponymous, noble African hero. It is set in the recently founded Dutch colony of Surinam, whose economy depended totally on slavery and which Behn herself had visited; she became a staunch opponent of slavery herself. “I was myself an Eye-witness to a great Part of what you will find here set down; and what I could not be Witness of, I receiv’d from the Mouth of the chief Actor in this History, the Hero himself.”

Unusually for this time, the narrator is female, giving Behn an opportunity to set out her feelings and opinions in a way that women authors were not expected to. Behn believed herself to be a writer of the first rank and commercially at least she certainly was, but she constantly felt she had to justify herself as a woman writer.

‘Tis not fit for the Ladys

In the preface to The Lucky Chance, quoted above, Behn wrote:

… They charge it with the old never failing Scandal—That ‘tis not fit for the Ladys: As if (if it were as they falsly give it out) the Ladys were oblig’d to hear Indecencys only from their Pens and Plays and some of them have ventur’d to treat ‘em as Coursely as ‘twas possible, without the least Reproach from them; and in some of their most Celebrated Plays have entertained ‘em with things, that if I should here strip from their Wit and Occasion that conducts ‘em in and makes them proper, their fair Cheeks would perhaps wear a natural Colour at the reading them: yet are never taken Notice of, because a Man writ them, and they may hear that from them they blush at from a Woman – But I make a Challenge to . . . any unprejudic’d Person that knows not the Author, to read any of my Comedys and compare ‘em with others of this Age, and if they find one Word that can offend the chastest Ear, I will submit to all their peevish Cavills; but Right or Wrong they must be Criminal because a Woman’s.

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

More information about Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn and the Beginnings of a Female Narrative Voice Poetry Foundation Behn on Writers Inspire Reader discussion on Goodreads. . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Scandalous, Sexually Explicit Writings of Aphra Behn appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 14, 2021

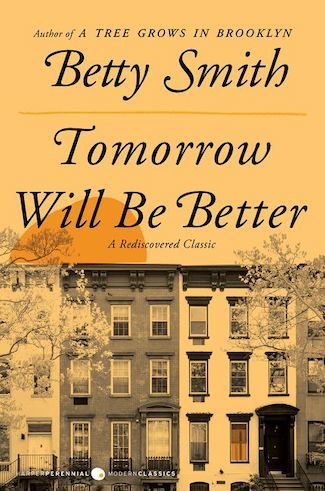

Tomorrow Will Be Better by Betty Smith (1948)

Betty Smith’s first novel, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1943), was a tough act to follow. And while her subsequent novels were all solid efforts, they didn’t achieve the phenomenal success of her debut. Tomorrow Will Be Better (1948), Smith’s second novel, is still very much worth discovering.

The families depicted in Tomorrow Will Be Better — the Shannons and the Malones — might be fictional neighbors of the Nolan family of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Set in the tenements of Brooklyn in the 1920s, it’s a quintessentially American tale of pursuing dreams in the face of obstacles — not the least of which is poverty.

Margy Shannon, a young woman filled with hope, is central to the narrative. In search of happiness and a better life, she faces disappointment with fortitude and dignity. As the review that follows noted, “Miss Smith has written a quiet, warm book about people she obviously knows and loves well.”

In a tribute to this novel in Vol. 1 Brooklyn (“Playing Checkers in Brooklyn: Hope and Resilience in Betty Smith’s Wartime Fiction”), Marcie McCauley comments:

“With HarperCollins’ November 2020 reprint of Betty Smith’s second novel, Tomorrow Will Be Better (1948), readers are reminded how infrequently working-class readers have seen their lives represented in fiction. More than seven decades after the launch of Betty Smith’s writing career, her focus on low-wage and no-wage families in fiction still stands out.

Even more remarkable, contemporary journalism echoes some of the story elements of Betty Smith’s historical novels. Many aspects of financial hardship in the 20th century are consistent with financial hardship in the 21st century.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Betty Smith

. . . . . . . . . .

In late 2020, HarperPerennial Modern Classics reissued Tomorrow Will Be Better for a new generation of readers. From the publisher:

From Betty Smith, author of the beloved classic A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, comes a poignant story of love, marriage, poverty, and hope set in 1920s Brooklyn.

Tomorrow Will Be Better tells the story of Margy Shannon, a shy but joyfully optimistic young woman just out of school who lives with her parents and witnesses how a lifetime of hard work, poverty, and pain has worn them down.

Her mother’s resentment toward being a housewife and her father’s inability to express his emotions result in a tense home life where Margy has no voice. Unable to speak up against her overbearing mother, Margy takes refuge in her dreams of a better life.

Her goals are simple—to find a husband, have children, and live in a nice home—one where her children will never know the terror of want or the need to hide from quarreling parents. When she meets Frankie Malone, she thinks her dreams might be fulfilled, but a devastating loss rattles her to her core and challenges her life-long optimism.

As she struggles to come to terms with the unexpected path her life has taken, Margy must decide whether to accept things as they are or move firmly in the direction of what she truly wants.

Rich with the flavor of its Brooklyn background, and filled with the joys and heartbreak of family life, Tomorrow Will Be Better is told with a simplicity, tenderness, and warmhearted humor that only Betty Smith could write.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like: A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review in The Times of San Mateo, CA, August 1948: A Tree Grows in Brooklyn has produced a shoot in Betty Smith’s second novel, Tomorrow Will Be Better. In fact, the Shannons and the Malones might be neighbors of those who peopled her first book.

It is a simple, authentic story of people’s stubborn pursuit of their dreams, their refusal to recognize a stern reality as anything but temporary. She writes with meticulous care and sympathetic skill of people faced with poverty a step above grinding, and clinging to hope a cut above pretensions.

Seeking love and plenty

Gentle, shy Margy Shannon wanted happiness — a husband, children, and a home which would know good humor, peace, love, and plenty. It is a story of Margy’s search for happiness, half understanding it had slipped away from her, but never giving up hope of it.

The Shannon home was dominated by nagging, frustrated Flo, bitter, irascible, and yet with a pent-up core of real love for her daughter. Her husband, Henny, feeling his own inadequacy, fought back a little. But Margy, loving and somewhat understanding her parents, thought only of escaping.

Facing the disappointments of marriage

So she married he first boy who “dated” her, Frankie Malone. Frankie came from the same poverty and the same way of life. It wasn’t the kind of marriage that Margy dreamed about — but she never lost hope that it would be, one day. Miss Smith has written a quiet, warm book about people she obviously knows and loves well.

. . . . . . . . . .

Tomorrow Will Be Better on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Tomorrow Will Be Better

Reader discussion on Goodreads Review on Kirkus Reviews Playing Checkers in Brooklyn: Hope and Resilience in Betty Smith’s Wartime Fiction Betty Smith’s “Tomorrow Will Be Better” Is Indeed a Rediscovered Classic. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Tomorrow Will Be Better by Betty Smith (1948) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 12, 2021

Elinor Wylie

Elinor Wylie (September 7, 1885 – December 16, 1928) was a popular American poet and novelist in the 1920s and 1930s. She was a celebrated author in her lifetime, with a cult following in her pinnacle years. She was well known for her passionate writing, fueled by ethereal descriptors, historical references, and feminist undertones.

During her short span of eight years as a writer, Elinor published four volumes of poetry and four novels, all garnering praise.

She was also widely known for her tumultuous personal life, which often made its way into her writings. Many of her works offered insight into the difficulties of marriage and the impossible expectations that come with womanhood.

A privileged upbringingBorn Elinor Hoyt in Somerville, New Jersey to Henry Martyn Hoyt, Jr and Anne Morton McMichael. Elinor was raised in a distinguished family. Her grandfather, Henry Hoyt, was the governor of Pennsylvania. Her aunt, Helen Hoyt, was also a poet.

By the time Elinor turned twelve, her family had moved to Washington, D.C., where her father became Solicitor General of the United States. She and her family often rubbed shoulders with D.C.’s political elite.

Elinor was educated in multiple private schools, but didn’t pursue a higher education. Raised in a privileged background, she was expected to be a debutante.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Marriages and scandalsAt age twenty, Elinor married Philip Simmons Hichborn. Though the marriage was unstable, they had a son together. Elinor alluded to Hichborn being volatile and abusive.

Elinor’s mother didn’t believe in divorce, and meddled in her marital decisions. Because of this, Elinor stayed in the marriage for longer than she had wished.

In the midst of her troubled marriage, Elinor found herself being stalked by Harvard Law graduate and prominent attorney Horace Wylie. He stalked her for years, though he was a married man with three children and seventeen years her senior.

In a shocking turn of events, Elinor left her husband and son, and eloped with Wylie. The incident became a widely-known scandal that was covered in the press. After being socially exiled by friends and family, the couple moved to England and changed their last name. Elinor’s ex-husband ended up committing suicide in 1916.

This wasn’t the end of Elinor’s tumultuous private life — she later left Wylie for her literary confidante, William Rose Benét. And after living with Benét for some years, they separated. Elinor ended up falling for her close friend’s husband, Henry de Clifford Woodhouse.

A brief but prolific writing career

Elinor first began to write seriously and considered publishing during her time in England. She published her first poems anonymously in 1912 in Incidental Numbers, a compilation of poems she had been working on for ten years.

After World War I broke out, Elinor returned to the U.S. with Horace Wylie, settling back in Washington, D.C. There, she frequented literary circles, befriending writers John Peale Bishop, Sinclair Lewis, and her future husband, William Rose Benét. Her literary friends encouraged her to publish.

She submitted poems to Poetry magazine, which published four of her pieces. One of the poems published was “Velvet Shoes,” her most widely anthologized piece.

After this taste of literary success, Elinor moved to New York City and continued making inroads into the literary scene. She published Nets to Catch the Wind in 1921, a collection that contains some of her best poems, including “Velvet Shoes,” “Wild Peaches,” and “Winter Sleep.”

Following Nets to Catch the Wind, she published another successful collection titled Black Armour (1923). It garnered glowing reviews, including one in the New York Times stating, “There is not a misplaced word or cadence in it. There is not an extra syllable.”

Angels and Earthly Creatures, which also received positive reviews, was published in 1925. This collection included nineteen sonnets dedicated to Henry de Clifford Woodhouse, her friend’s husband.

Elinor Wylie published four novels in addition to her poetic work: Jennifer Lorn (1923), The Venetian Glass Nephew (1925), and The Orphan Angel (1926), all of which had rave reviews. Jennifer Lorn’s publication even prompted a torchlight parade in Manhattan to celebrate its release. In all, she published some ten collections of poetry.

Elinor also worked as the poetry editor of Vanity Fair magazine from 1923 to 1925, and edited for The Literary Guild and The New Republic in her later years.

Elinor had suffered from dangerously high blood pressure for much of her life. In the winter of 1928, Elinor died of a stroke. At age forty-three, her untimely death came at the height of her career.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Taking a deep dive into Elinor Wylie’s workElinor often used her own complicated private life to fuel her works. In many ways, she was a master of subtlety.

Her poems were often rebellious in nature, using her continually failing marriages as a framework for her dissatisfaction with femininity and the expectations that come with it. In that same vein of rebellion, she often expressed her distaste for the wealthy environment in which she was raised.

She expressed these things quietly, through vivid and romantic descriptions. A perfect example of this can be seen in her popular poem “Wild Peaches”:

Down to the Puritan marrow of my bones

There’s something in this richness that I hate.

I love the look, austere, immaculate,

Of landscapes drawn in pearly monotones.

There’s something in my very blood that owns

Bare hills, cold silver on a sky of slate …

Within this dense, romantic poem, Elinor delves into her internal battle with her upbringing. She cloaks these insurgent perspectives by utilizing rich, pastoral details that are oftentimes seen in more traditional works. In this way, Elinor Wylie was a part of a vanguard of women poets, creating a path for feminist literature.

Elinor Wylie’s legacy

Elinor Wylie appealed to general audiences as well as literary critics. Her ability to create writing that was universally enjoyable made her famous.

Today, Elinor is praised by feminist theorists and literary critics. During her lifetime, her marital scandals were notorious and looked down upon. Many of her pieces offer clear insight into the deceptive trap of marriage and the impossible expectations that come with womanhood.

American poet Louis Untermeyer once described Elinor’s writing as “a passion frozen at its source.” Elinor’s literary force transcends the marital scandals that once marked her reputation. She was as subtle as she was bold. Her ability to blend more modern themes within a traditionalist writing style contributed to the developing aesthetic of modernism.

. . . . . . . . .

Elinor Wylie page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Jess Mendes, a 2021 graduate of SUNY-New Paltz with a major in Digital Media Management, and a minor in Creative Writing.

More About Elinor WylieMajor Works

Poetry

Incidental Numbers (1912) Nets to Catch the Wind (1921)Black Armour. New York: Doran, (1923).Trivial Breath. New York, London: Knopf, (1928.Angels and Earthly Creatures: A Sequence of Sonnets (1928)Birthday Sonnet. New York: Random House, 1929.Collected Poems of Elinor Wylie. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, (1932)Selected Works of Elinor Wylie (Evelyn Helmick Hively, ed. 2005)Fiction

Jennifer Lorn: A Sedate Extravaganza (1923)The Venetian Glass Nephew (1925)The Orphan Angel (1926)Mr. Hodge & Mr. Hazard (1928)Collected Prose of Elinor Wylie (1933)Biography

A Private Madness: The Genius of Elinor Wylie by Evelyn Hively (2003)More information and sources

Wikipedia The Poetry Foundation Elinor Wylie: A Sordid Life – Owlcation Britannica Listen to Elinor Wylie’s poetry on Librivox. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Elinor Wylie appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 10, 2021

Advice to Young Ladies on Reading Novels — From Early Female Authors

Is it possible that early female authors actually warned their target audience —female readers —against the practice of reading novels? It’s not only possible, but seemed to be a fairly common occurrence.

When Madame Bovary first commits adultery, Flaubert tells us that it was her early reading of novels that was to blame: “she recalled the heroines of the books that she had read, and the lyric legion of these adulterous women began to sing in her memory with the voice of sisters that charmed her.”

In his A Plan for the Conduct of Female Education of 1797, Erasmus Darwin warns that ‘many objectionable passages’ are to be found in novels and Rousseau said ‘no chaste girls ever read a novel.’ But even groundbreaking literary ladies who wrote novels themselves were in two minds about letting their daughters, granddaughters and nieces read them. Here’s a sampling:

. . . . . . . . . . .

Perhaps, were it possible to effect the total extirpation of novels, our young ladies in general, and boarding-school damsels in particular, might profit from their annihilation; but since the distemper they have spread seems incurable, since their contagion bids defiance to the medicine of advice or reprehension, and since they are found to baffle all the mental art of physic, save what is prescribed by the slow regimen of Time, and bitter diet of Experience; surely all attempts to contribute to the number of those which may be read, if not with advantage, at least without injury, ought rather to be encouraged than condemned.

— Fanny Burney (1752 – 1840), from the preface to Evelina (1778)

. . . . . . . . . . .

I can’t forbear saying something in relation to my granddaughters, who are very near my heart. If any of them are fond of reading, I would not advise you to hinder them (chiefly because it is impossible) seeing poetry, plays, or romances; but accustom them to talk over what they read, and point out to them, as you are very capable of doing, the absurdity often concealed under fine expressions, where the sound is apt to engage the admiration of young people.

I was so much charmed, at fourteen, with the dialogue of Henry and Emma, I can say it by heart to this day, without reflecting on the monstrous folly of the story in plain prose, where a young heiress to a fond father is represented falling in love with a fellow she had only seen as a huntsman, a falconer, and a beggar, and who confesses, without any circumstances of excuse, that he is obliged to run his country, having newly committed a murder.

She ought reasonably to have supposed him, at best, a highwayman; yet the virtuous virgin resolves to run away with him, to live among the banditti, and wait upon his trollop, if she had no other way of enjoying his company. This senseless tale is, however, so well varnished with melody of words and pomp of sentiments, I am convinced it has hurt more girls than ever were injured by the lewdest poems extant.

— Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, (1689 – 1752) from a letter to her daughter

. . . . . . . . . . .

With respect to sentimental stories, and books of mere entertainment, we must remark, that they should be sparingly used, especially in the education of girls. This species of reading, cultivates what is called the heart prematurely; lowers the tone of the mind, and induces indifference for those common pleasures and occupations which, however trivial in themselves, constitute by far the greatest portion of our daily happiness.

Stories are the novels of childhood. We know, from common experience, the effects which are produced upon the female mind by immoderate novel reading. To those who acquire this taste, every object becomes disgusting which is not in an attitude for poetic painting; a species of moral picturesque is sought for in every scene of life, and this is not always compatible with sound sense, or with simple reality.

— Maria Edgeworth (1767 – 1849), Practical Education, 1798

. . . . . . . . . . .

I would by no means exclude the kind of reading, which young people are naturally most fond of; though I think the greatest care should be taken in the choice of those fictitious stories, that so enchant the mind – most of which tend to inflame the passions of youth, whilst the chief purpose of education should be to moderate and restrain them.

Add to this, that both the writing and sentiments of most novels and romances are such as are only proper to vitiate your style, and to mislead your heart and understanding. The expectation of extraordinary adventures – which seldom ever happen to the sober and prudent part of mankind – and the admiration of extravagant passions and absurd conduct, some of the usual fruits of this kind of reading; which, when a young woman makes it her chief amusement, generally renders her ridiculous in conversation, and miserably wrongheaded in her pursuits and behavior.

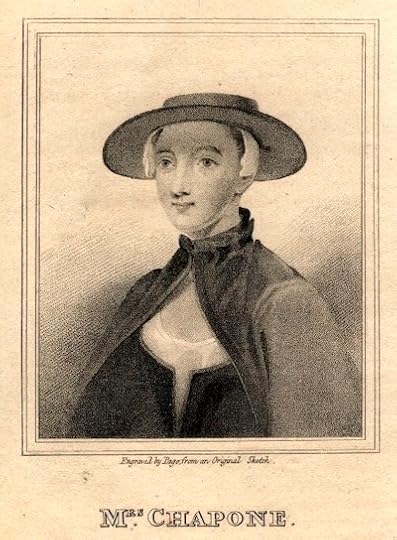

— Hester Chapone (1727 – 1801), Letters on the Improvement of the Mind, Addressed to a Young Lady, 1773

. . . . . . . . . . .

When she was seven years of age, he chose her such books to read in as might make her wise, not amorous, for he never suffered her to read in romances, nor such light books; but moral philosophy was the first of her studies, to lay a ground and foundation of virtue, and to teach her to moderate her passions, and to rule her affections.

The next, her study was in history, to learn her experience by the second hand, reading the good fortunes and misfortunes of former times, the errors that were committed, the advantages that were lost, the humour and dispositions of men, the laws and customs of nations, their rise, and their fallings, of their wars and agreements, and the like. The next study was in the best of poets, to delight in their fancies, and to recreate in their wit; and this she did not only read, but repeat what she had read every evening before she went to bed.

— Margaret Cavendish, (1623 – 1673) The Contract, 1756

. . . . . . . . . . .

She soon became a perfect Mistress of the French and Italian Languages, under the Care of her Father; and it is not to be doubted, but she would have made a great Proficiency in all useful Knowledge, had not her whole Time been taken up by another Study. From her earliest Youth she had discovered a Fondness for Reading, which extremely delighted the Marquis; he permitted her therefore the Use of his Library, in which, unfortunately for her, were great Store of Romances, and, what was still more unfortunate, not in the original French, but very bad Translations.

Charlotte Lennox (1730 – 1804), The Female Quixote, 1752

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Advice to Young Ladies on Reading Novels — From Early Female Authors appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 9, 2021

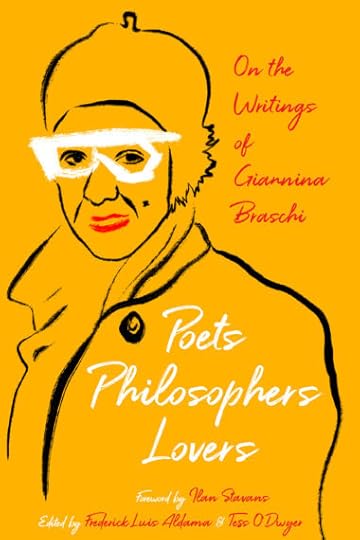

Giannina Braschi in the World of Contemporary Latinx Literature

This introduction to Latinx literary figure Giannina Braschi is excerpted from Poets, Philosophers, Lovers: On the Writings of Giannina Braschi, edited by by Frederick Luis Aldama and Tess O’Dwyer. © 2020 University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved, reprinted by permission.

Scholar, playwright, spoken-word performer, award-winning poet, and avant-garde fiction author, since the 1980s Giannina Braschi has been creating up a storm in and around a panoply of Latinx hemispheric spaces.

Her creative corpus reaches across different genres, regions, and historical epochs. Her critical works cover a wide range of subjects and authors, including Miguel de Cervantes, Garcilaso de la Vega, Juan Ramón Jiménez, Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, Antonio Machado, César Vallejo, and García Lorca.

. . . . . . . . . .

Giannina Braschi

. . . . . . . . . .

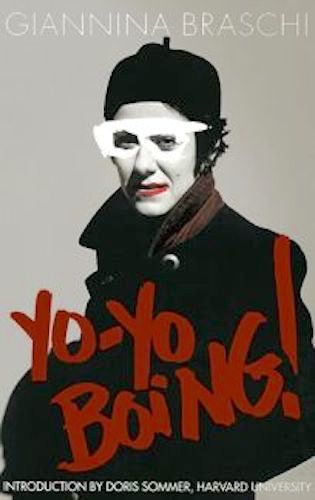

Braschi’s dramatic poetry titles in Spanish include Asalto al tiempo (1981) and La comedia profana (1985). Her radically experimental genre-bending titles include El imperio de los sueños (1988), the bilingual Yo-Yo Boing! (1998), and the English-penned United States of Banana (2011). With national and international awards and works appearing in Swedish, Slovenian, Russian, and Italian, she is recognized as one of today’s foremost experimental Latinx authors.

Her vibrant bilingually shaped creative expressions and innovation spring from her Latinidad, her Puerto Rican-ness that weaves in and through a planetary aesthetic sensibility. We discover as much in her work about US/Puerto Rico sociopolitical histories as we encounter the metaphysical and existential explorations of a Cervantes, Rabelais, Diderot, Artaud, Joyce, Beckett, Stein, Borges, Cortázar, and Rosario Castellanos, for instance.

With every flourish of her pen Braschi reminds us that in the distillation and reconstruction of the building blocks of the universe there are no limits to what fiction can do. And, here too, the black scratches that form words and carefully composed blank spaces shape an absent world; her strict selection out of words and syntax is as important as the precise insertion of words and syntax to put us into the shoes of the “complicit reader” (Julio Cortázar’s term) to most productively interface, invest, and fill in the gaps of her storyworlds.

. . . . . . . . . .

Poets Philosophers Lovers on Bookshop.org*

Poets Philosophers Lovers on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Braschi reminds us of the power of lexis—asking us to deep-dive into the metaphorical, subtextual, and allegorical layers of meaning. No subject remains untouched in her fiction making. She draws from Latinx realities as well as metaphysics— even historical archive, sociopolitical, and judicial discourses. Indeed, Braschi invents new forms to express polyvalent Latinx sensibilities that shape-shift across time, place, and identity categories.

In many ways, as a contemporary Latinx author Braschi stands apart. Her radically experimental works continue to grow a genealogy of Latinx letters, but they do so from the avant-garde margins. Taken as a whole her work extends and complicates a trajectory of Latinx experimental fiction that has not received the same critical attention as, perhaps, the work of a more straightforward realist writer such as an Esmeralda Santiago or a Piri Thomas.

Sidestepping the easily consumable, Braschi’s creative work puts pressure on and radically bends a Latinx literary canon, and with this she calls attention to the self-within-the-collective of nation and diasporic community. She converses with Isabel Rios (Victuum, 1976), Cecile Pineda (Face, 1985), Guillermo Gomez-Peña (Codex Espangliensis, 1998), Alejandro Morales (Waiting to Happen, 2001), Salvador Plascencia (The People of Paper, 2005), or Sesshu Foster (Atomik Aztex, 2005).

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

And today we see Braschi joined by a growing number of Latinx canon-benders such as Carmen María Machado, Elizabeth Acevedo, Monica de la Torre, and Naomi Ayala. More globally, Braschi’s works extend and complicate a genealogy of avant-garde women of color authors such as Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Claudia Rankine, and Audre Lorde, and she joins with other planetary cutting-edge contemporaries such as Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi, Pamela Lu, Zinzi Clemmons, and Sumana Roy.

Although standing apart, Braschi as creator clearly doesn’t exist ex nihilo. Indeed, we see her build on and redeploy the work of feminist and queer fore-figures, including Cristina Peri Rossi, Alejandra Pizarnik, Clarice Lispector, Luce Irigaray, Helene Cixous, Marguerite Duras, and Gertrude Stein. She does so less from an identity perspective and more from a theoretical practice perspective.