Nava Atlas's Blog, page 48

December 11, 2020

To Flush, My Dog by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806 – 1861), the British poet, accomplished what few women writers did in her time — and that was gaining the respect and admiration of the literary world. In fact, she was far better known than her husband, fellow poet Robert Browning, in their lifetime.

Mary Russell Mitford, another writer, gave Elizabeth the cocker spaniel she named Flush as solace after the death of her brother in 1840.

From the start, Elizabeth adored Flush, so much so that she dedicated this poem to him. However, Flush wasn’t always on board with Robert Browning, his rival for Elizabeth’s affection, as detailed in this article. Browning even endured a few mean bites during their legendary courtship.

Though Flush wasn’t in attendance at the Brownings’ secret wedding, he was part of their escape to Florence, Italy, where they settled in 1847. It was fortunate that he was safely at home at this juncture, as poor Flush had been stolen three times.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Literary Love Story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning

. . . . . . . . . .

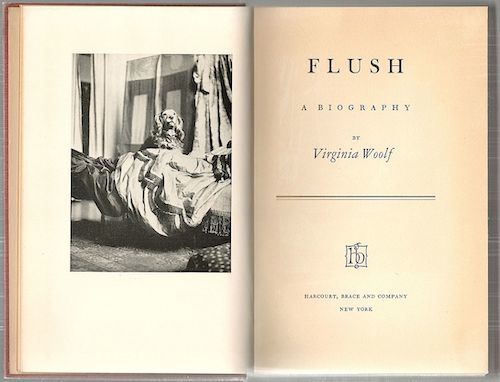

Flush may not have become as famous as his mistress, but no subsequent depiction of her life story would have been complete without him. He featured in the 1934 film, The Barretts of Wimpole Street, and in Flush, a “biography” of him written by Virginia Woolf (and illustrated by her sister, Vanessa Bell), published in 1933.

It’s unclear when exactly the poem “To Flush, My Dog” was written, but it seems safe to surmise that it was sometime between when Elizabeth received him in 1840 and 1847 when she departed with him and Robert to Italy.

More on Elizabeth and Flush

Then and There Flush with Love

“Too Caninely Noble” — On Elizabeth’s life with Flush and Virginia Woolf’s biography

Analysis of “To Flush, My Dog”

More poetry by Elizabeth Barrett Browning on this site

“A Dead Rose”: An Ecocritical Reading

“To George Sand: A Desire”

. . . . . . . . . .

Norma Shearer as Elizabeth Barrett Browning

in the 1934 film, The Barretts of Wimpole Street

. . . . . . . . . .

To Flush, My Dog

LOVING friend, the gift of one,

Who, her own true faith, hath run,

Through thy lower nature;

Be my benediction said

With my hand upon thy head,

Gentle fellow-creature!

Like a lady’s ringlets brown,

Flow thy silken ears adown

Either side demurely,

Of thy silver-suited breast

Shining out from all the rest

Of thy body purely.

Darkly brown thy body is,

Till the sunshine, striking this,

Alchemize its dulness, —

When the sleek curls manifold

Flash all over into gold,

With a burnished fulness.

Underneath my stroking hand,

Startled eyes of hazel bland

Kindling, growing larger, —

Up thou leapest with a spring,

Full of prank and curvetting,

Leaping like a charger.

Leap! thy broad tail waves a light;

Leap! thy slender feet are bright,

Canopied in fringes.

Leap — those tasselled ears of thine

Flicker strangely, fair and fine,

Down their golden inches.

Yet, my pretty sportive friend,

Little is ‘t to such an end

That I praise thy rareness!

Other dogs may be thy peers

Haply in these drooping ears,

And this glossy fairness.

But of thee it shall be said,

This dog watched beside a bed

Day and night unweary, —

Watched within a curtained room,

Where no sunbeam brake the gloom

Round the sick and dreary.

Roses, gathered for a vase,

In that chamber died apace,

Beam and breeze resigning —

This dog only, waited on,

Knowing that when light is gone,

Love remains for shining.

Other dogs in thymy dew

Tracked the hares and followed through

Sunny moor or meadow —

This dog only, crept and crept

Next a languid cheek that slept,

Sharing in the shadow.

Other dogs of loyal cheer

Bounded at the whistle clear,

Up the woodside hieing —

This dog only, watched in reach

Of a faintly uttered speech,

Or a louder sighing.

And if one or two quick tears

Dropped upon his glossy ears,

Or a sigh came double, —

Up he sprang in eager haste,

Fawning, fondling, breathing fast,

In a tender trouble.

And this dog was satisfied,

If a pale thin hand would glide,

Down his dewlaps sloping, —

Which he pushed his nose within,

After, — platforming his chin

On the palm left open.

This dog, if a friendly voice

Call him now to blyther choice

Than such chamber-keeping,

Come out! praying from the door, —

Presseth backward as before,

Up against me leaping.

Therefore to this dog will I,

Tenderly not scornfully,

Render praise and favour!

With my hand upon his head,

Is my benediction said

Therefore, and for ever.

And because he loves me so,

Better than his kind will do

Often, man or woman,

Give I back more love again

Than dogs often take of men, —

Leaning from my Human.

Blessings on thee, dog of mine,

Pretty collars make thee fine,

Sugared milk make fat thee!

Pleasures wag on in thy tail —

Hands of gentle motion fail

Nevermore, to pat thee!

Downy pillow take thy head,

Silken coverlid bestead,

Sunshine help thy sleeping!

No fly ‘s buzzing wake thee up —

No man break thy purple cup,

Set for drinking deep in.

Whiskered cats anointed flee —

Sturdy stoppers keep from thee

Cologne distillations;

Nuts lie in thy path for stones,

And thy feast-day macaroons

Turn to daily rations!

Mock I thee, in wishing weal? —

Tears are in my eyes to feel

Thou art made so straightly,

Blessing needs must straighten too, —

Little canst thou joy or do,

Thou who lovest greatly.

Yet be blessed to the height

Of all good and all delight

Pervious to thy nature, —

Only loved beyond that line,

With a love that answers thine,

Loving fellow-creature!

. . . . . . . . . . . .

More about Virginia Woolf’s biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s spaniel, Flush

The post To Flush, My Dog by Elizabeth Barrett Browning appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 9, 2020

Margaret Fuller, Trailblazing Journalist and Reformer

Margaret Fuller (born Sarah Margaret Fuller; later Margaret Fuller Ossoli; 1810 – 1850) was a well-known figure in her lifetime as a women’s rights advocate, abolitionist, editor, and journalist. For a time, she was considered the best-read person in New England and became the first woman to gain access to Harvard’s library.

In 1844, Margaret joined the New York Herald Tribune as America’s first full-time book reviewer. In 1846, she became the Tribune’s first woman editor and first female foreign correspondent. After spending four tumultuous and productive years in Europe, Fuller died tragically in a ship accident upon returning to America, leaving a legacy that was controversial as it was unique.

A staunch advocate of women’s rights (especially in the areas of education and employment), she was also active in the areas of prison reform and was an abolitionist before the Civil War. Many reformers who came after her, including Susan B. Anthony, cited Margaret Fuller as an inspiration.

Because her life was cut short, she didn’t have time to publish many full-length works (and devoted much of her career to being an editor, journalist, and teacher), but her 1845 book, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, was her magnum opus. Though her renown and reputation faded shortly after her death, her life and work are certainly deserving of reconsideration.

The following biography of Margaret Fuller has been adapted from Lives of Girls Who Became Famous by Sarah Knowles Bolton, 1886/1914, hence the somewhat florid language.

A precocious child

Margaret Fuller, in some respects the most remarkable of American women, lived a pathetic life and died a tragic death. Without money or beauty, she became the idol of an immense circle of friends; men and women were alike her devotees. It is the old story: that the woman with brains makes lasting conquests of hearts, while the pretty face holds its sway only for a month or a year.

Margaret, born in Cambridgeport, Massachusetts on May 23, 1810, was the oldest child of a scholarly lawyer, Mr. Timothy Fuller, and of a sweet-tempered, devoted mother. The father, with small means, had one absorbing purpose in life—to see that each of his children was finely educated. To do this, and make ends meet, was a struggle.

Very fond of his oldest child, Margaret, the father determined that she should be as well educated as his boys. In those days there were no colleges for girls and none where they might enter with their brothers, so Mr. Fuller was obliged to teach his daughter after the wearing work of the day.

The bright child began to read Latin at age six, but was necessarily kept up late for the recitation. When a little later she was walking in her sleep, and dreaming strange dreams, he did not see that he was overtaxing both her body and brain.

When not reading, Margaret enjoyed her mother’s little garden of flowers: “I loved to gaze on the roses, the violets, the lilies, the pinks; my mother’s hand had planted them, and they bloomed for me. I kissed them, and pressed them to my bosom with passionate emotions. An ambition swelled my heart to be as beautiful, as perfect as they.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A studious teen

Margaret grew to fifteen with an exuberance of life and affection, which the chilling atmosphere of that New England home somewhat suppressed, and with an increasing love for books and cultured people.

“I rise a little before five,” she wrote, “walk an hour, and then practice on the piano till seven, when we breakfast. Next, I read French — Sismondi’s Literature of the South of Europe — till eight; then two or three lectures in Brown’s Philosophy. About half-past nine I go to Mr. Perkins’s school, and study Greek till twelve, when, the school being dismissed, I recite, go home, and practice again till dinner, at two. Then, when I can, I read two hours in Italian.”

And why all this hard work for a girl of fifteen? The “all-powerful motive of ambition,” she claimed. “I am determined on distinction, which formerly I thought to win at an easy rate; but now I see that long years of labor must be given.”

Two years after, at seventeen, she wrote: “I am studying Madame de Staël, Epictetus, Milton, Racine, and the Castilian ballads, with great delight … I am engrossed in reading the elder Italian poets, beginning with Berni, from whom I shall proceed to Pulci and Politian.”

A well-loved figure

Witty, learned, imaginative, she was conceded to be the best conversationist in any circle. She possessed the charm that every woman may possess — appreciation of others, and interest in their welfare.

This sympathy unlocked every heart to her. All loved her. Now it was a serving girl who told Margaret her troubles and her cares; now it was a distinguished man of letters. She was always an inspiration. Men never talked idle, commonplace talk with her; she could appreciate the best of their minds and hearts, and they gave it. She was fond of social life, and no party seemed complete without her.

Starting to teach and a breakdown in health

At age twenty-two, she began to study German, and in three months was reading with ease Goethe’s Faust, Tasso and Iphigenia, Körner, Richter, and Schiller. She greatly admired Goethe, desiring, like him, “always to have some engrossing object of pursuit.” Besides all this study she was teaching six little children, to help bear the expenses of the household.

The family at this time moved to Groton, a great privation for Margaret, who enjoyed and needed the culture of Boston society. The teaching was continued because her brothers must be sent to Harvard College, and this required money; not the first nor the last time that sisters have worked to give their brothers an education superior to their own.

At last, the constitution, never robust, broke down, and for nine days Margaret lay hovering between this world and the next.

While Margaret recovered, her father was taken suddenly with cholera and died after two days’ illness. He was sadly missed, for at heart he was devoted to his family. When the estate was settled, there was little left for each; so for Margaret life would be more laborious than ever.

She had expected to visit Europe with Harriet Martineau, who was just returning home from a visit to this country, but the father’s death crushed this long-cherished and ardently-prayed-for journey. She must stay at home and work for others.

Margaret now obtained a situation as a teacher of French and Latin in Bronson Alcott‘s school. Here she was appreciated by both master and pupils. Mr. Alcott said, “I think her the most brilliant talker of the day. She has a quick and comprehensive wit, a firm command of her thoughts, and a speech to win the ear of the most cultivated.” She taught advanced classes in German and Italian, besides having several private pupils.

She was passionately fond of music and art, saying, “I have been very happy with four hundred and seventy designs of Raphael in my possession for a week.” She loved nature like a friend, paying homage to rocks and woods and flowers. She said, “I hate not to be beautiful when all around is so.”

Beginning as a speaker and editor

After teaching with Mr. Alcott, she became the principal teacher in a school at Providence, R.I. Here, as ever, she showed great wisdom both with children and adults. After two years in Providence she returned to Boston, and in 1839 began a series of parlor lectures, or “conversations,” as they were called.

This seemed a strange thing for a woman, when public speaking by her sex was almost unknown. These talks were given weekly, from eleven o’clock till one, to twenty-five or thirty of the most cultivated women of the city.

Now the subject of discussion was Grecian mythology; now it was fine arts, education, or the relations of a woman to the family, the church, society, and literature. In these gatherings, Margaret was at her best — brilliant, eloquent, charming.

During this time a few gifted men, Emerson, Channing, and others, decided to start a literary and philosophical magazine called the Dial. Probably no woman in the country would have been chosen as the editor, save Margaret Fuller. She accepted the position, and for four years managed the journal ably, writing for it some valuable essays.

Some of these were published later in her book on Literature and Art. Her Woman in the Nineteenth Century, a learned and vigorous essay on woman’s place in the world, first appeared in part in the Dial.

Of this work, she said, in closing it, “After taking a long walk, early one most exhilarating morning, I sat down to work, and did not give it the last stroke till near nine in the evening. Then I felt a delightful glow, as if I had put a good deal of my true life in it, and as if, should I go away now, the measure of my footprint would be left on the earth.”

A writer and translator

Margaret Fuller had published, besides these works, two books of translations from German, and a sketch of travel called Summer on the Lakes. Her experience was like that of most authors who are beginning—some fame, but no money realized. All this time she was frail in health, overworked, struggling against odds to make a living for herself and those she loved.

Margaret was now thirty-four. Her sister was married, the brothers had finished their college course, and she was about to accept an offer from the New York Tribune to become one of its constant contributors, an honor that few women would have received. Early in December 1844, Margaret moved to New York and became a member of Horace Greeley‘s newspaper family. Her literary work here was that of “the best literary critic whom America has yet seen.”

A European journey

A year and a half later an opportunity came for Margaret to go to Europe. Now, at last, she would see the art galleries of the old world, and places rich in history, like Rome. Still, there was the trouble of scanty means and poor health from overwork.

She said, “A noble career is yet before me if I can be unimpeded by cares. If our family affairs could now be so arranged that I might be tolerably tranquil for the next six or eight years, I should go out of life better satisfied with the page I have turned in it than I shall if I must still toil on.”

In Paris, Margaret attended the Academy lectures, saw much of George Sand, waded through melting snow at Avignon to see Laura’s tomb, and at last was in Italy, the country she had longed to see.

Here she settled down to systematic work, trying to keep her expenses for six months within four hundred dollars. Still, when most cramped for means herself, she was always generous. Once, when living on a mere pittance, she loaned fifty dollars to a needy artist.

In New York she gave an impecunious author five hundred dollars to publish his book, and, of course, never received a dollar in return. Yet the race for life was wearing her out. So tired was she that she said, “I should like to go to sleep, and be born again into a state where my young life should not be prematurely taxed.”

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Falling in love in Italy

Margaret befriended Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini, and was enthusiastic for Roman liberty. All those dreadful months she ministered to the wounded and dying in the hospitals, and was their “saint,” as they called her. But there was another reason why Margaret Fuller loved Italy.

Soon after her arrival in Rome, as she was attending vespers at St. Peter’s with a party of friends, she became separated from them. Failing to find them, seeing her anxious face, a young Italian came up to her, and politely offered to assist her.

Unable to regain her friends, Angelo Ossoli walked with her to her home, though he could speak no English, and she almost no Italian. She learned afterward that he was of a noble and refined family; that his brothers were in the Papal army, and that he was highly respected.

After this, he saw Margaret once or twice when she left Rome for some months. On her return, he renewed the acquaintance, shy and quiet though he was, for her influence seemed great. His father, the Marquis Ossoli, had just died, and Margaret, with her large heart, sympathized with him.

Finally, he confessed to Margaret that he loved her and that he “must marry her or be miserable.” She refused to listen to him as a lover, said he must marry a younger woman—she was thirty-seven, and he but thirty—but she would be his friend. For weeks he was dejected and unhappy.

She debated the matter with her own heart. Should she, who had had many admirers, now marry a man her junior, and not of surpassing intellect, like her own? If she married him, it must be kept a secret till his father’s estate was settled, for marriage with a Protestant would spoil all prospect of an equitable division.

Love conquered, and she married the young Marquis Ossoli in December 1847. He gave Margaret the kind of love which lasts after marriage, veneration of her ability and her goodness.

“Such tender, unselfish love,” recalled a friend of Margaret’s. “I have rarely before seen; it made green her days, and gave her an expression of peace and serenity which before was a stranger to her. When she was ill, he nursed and watched over her with the tenderness of a woman. No service was too trivial, no sacrifice too great for him. ‘How sweet it is to do little things for you,’ he would say.”

To her mother, Margaret wrote, though she did not tell her secret, “I have not been so happy since I was a child, as during the last six weeks.”

The horrors of war

But days of anxiety soon came, with all the horrors of war. Ossoli was constantly exposed to death in that dreadful siege of Rome. Then Rome fell, and with it the hopes of Ossoli and his wife. There would be neither fortune nor home for a Liberal now — only exile. Very sadly Margaret said goodbye to the soldiers in the hospitals, brave fellows whom she honored, who in the midst of death itself, would cry “Viva l’Italia!”

But before leaving Rome, a day’s journey must be made to Rieta, at the foot of the Umbrian Apennines. And for what? The most precious thing of Margaret’s life was there — her baby. The fair child, with blue eyes and light hair like her own, had already been named by the people in the house, Angelino, from his beauty.

. . . . . . . . . .

Books by and about Margaret Fuller on Bookshop.org*

Books by and about Margaret Fuller on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Becoming a mother

Margaret had always been fond of children, and now a new joy had come into her heart, a child of her own.

She wrote to her mother: “In him, I find satisfaction, for the first time, to the deep wants of my heart. Nothing but a child can take the worst bitterness out of life, and break the spell of loneliness. I shall not be alone in other worlds, whenever Eternity may call me … I wake in the night — I look at him. He is so beautiful and good, I could die for him!”

When Ossoli and Margaret reached Rieta, what was their horror to find their child worn to a skeleton, half-starved through the falsity of a nurse. For four weeks the distressed parents coaxed him back to life, till the sweet beauty of the rounded face came again, and then they carried him to Florence, where, despite poverty and exile, they were happy.

Considering a return to America

Margaret’s friends now urged her to return to America. She had nearly finished a history of Rome in this trying time, 1848, and could better attend to its publication in this country. Ossoli, though coming to a land of strangers, could find something to help, support the family.

To save expense, they started from Leghorn, May 17, 1850, in the Elizabeth, a sailing vessel, though Margaret dreaded the two months’ voyage, and had premonitions of disaster. She wrote:

“I have a vague expectation of some crisis — I know not what. But it has long seemed that, in the year 1850, I should stand on a plateau in the ascent of life, when I should be allowed to pause for a while, and take more clear and commanding views than ever before. Yet my life proceeds as regularly as the fates of a Greek tragedy, and I can but accept the pages as they turn …

I shall embark, praying fervently that it may not be my lot to lose my boy at sea, either by unsolaced illness, or amid the howling waves; or, if so, that Ossoli, Angelo, and I may go together, and that the anguish may be brief.”

For a few days, all went well on shipboard. Then the noble Captain Hasty died of small-pox, and was buried at sea. Angelino took this dread disease, and for a time his life was despaired of, but he finally recovered and became a great pet with the sailors. Margaret was putting the last touches to her book. Ossoli and young Sumner, brother of Charles, gave each other lessons in Italian and English, and thus the weeks went by.

A tragedy in the making

On Thursday, July 18, after two months, the Elizabeth stood off the Jersey coast, between Cape May and Barnegat. Trunks were packed, good nights were spoken, and all were happy, for they would be in New York on the morrow.

At nine that night a gale arose; at midnight it was a hurricane; at four o’clock, Friday morning, the ship struck Fire Island beach. The passengers sprung from their berths. “We must die!” said Sumner to Mrs. Hasty. “Let us die calmly, then!” was the response of the widow of the captain.

One of the sailors suggested that if each passenger would sit on a plank, holding on by ropes, they would attempt to push him or her to land. Margaret was urged, but she hesitated, unless all three could be saved. Every moment the danger increased.

Margaret had finally been induced to try the plank. The steward had taken Angelino in his arms, promising to save him or die with him, when a strong sea swept the forecastle, and all went down together.

Ossoli caught the rigging for a moment, but Margaret sank at once. When last seen, she was seated at the foot of the foremast, still clad in her white nightdress, with her hair fallen loose upon her shoulders. Angelino and the steward were washed up on the beach twenty minutes later, both dead, though warm. Margaret’s prayer was answered—that they “might go together, and that the anguish might be brief.”

The pretty boy of two years was dressed in a child’s frock taken from his mother’s trunk, which had come to shore, laid in a seaman’s chest, and buried in the sand, while the sailors, who loved him, stood around, weeping. His body was finally removed to Mt. Auburn, and buried in the family lot.

Bodies never recovered

The bodies of Margaret and Ossoli were never recovered. The only papers of value that came to shore were their love letters, now deeply prized. The book ready for publication was never found.

When those on shore were asked why they did not launch the life-boat, they replied, “Oh! if we had known there were any such persons of importance on board, we should have tried to do our best!”

Thus, at forty, died one of the most gifted women in America, when her work seemed just begun. To us, who see how the world needed her, her death is a mystery. She filled her life with charities and her mind with knowledge, and such are ready for the progress of Eternity.

More about Margaret Fuller

Major Works

Summer on the Lakes (1844)

Woman in the Nineteenth Century (1845)

Papers on Literature and Art (1846)

Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli (1852)

At Home and Abroad (1856)

Life Without and Life Within (1858)

Biographies

Margaret Fuller (Marchesa Ossoli) by Julia Ward Howe (1883)

The Essential Margaret Fuller by Jeffrey Steele, 1992

Margaret Fuller: An American Romantic Life by Charles Capper, 2010

The Lives of Margaret Fuller by John Matteson, 2012

Margaret Fuller: A New American Life by Megan Marshall, 2014

More about Margaret Fuller

Wikipedia

“An unfinished woman: The desires of Margaret Fuller” by Judith Thurman

Margaret Fuller and Her Conversations

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Margaret Fuller, Trailblazing Journalist and Reformer appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 4, 2020

Sonnets from the Portuguese by Elizabeth Barrett Browning (full text)

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806 – 1861) was immensely accomplished and respected in her own lifetime, no small accomplishment for a female poet. Following is the full text of what is arguably her best-known work, Sonnets from the Portuguese, a fragment of one of her major collections, Poems (1844/1850).

Born in County Durham, England, Elizabeth Barrett grew up in an atmosphere of privilege and culture, which allowed her to develop a precocious talent in poetry.

After having a collections of her poetry published while still in her teens, Elizabeth was introduced to British literary society in the 1830s. Her individual poems were becoming known and respected in these circles.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Elizabeth Barrett Browning

. . . . . . . . . .

Her first collection, Poems (1844) was an immediate success in Europe and the U.S. and made her famous. A Drama of Exile: and Other Poems (1845) cemented her reputation.

In 1850, her collection, Poems, was published in a new and expanded edition. It contained what is now considered one of her masterpieces, Sonnets from the Portuguese, the collection of forty-four love poems she wrote in secret to her husband, Robert Browning, presented here.

The title alludes to one of his pet names for her, when he called her ‘my Portuguese.’ The couple had one of the most romantic of love stories between two major literary figures. Sonnets from the Portuguese is in the public domain.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Literary Love Story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning

. . . . . . . . . .

According to her biography on Poetry Foundation:

“Among all female poets of the English-speaking world in the 19th century, none was held in higher critical esteem or was more admired for the independence and courage of her views than Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

During the years of her marriage to Robert Browning, her literary reputation far surpassed that of her poet-husband; when visitors came to their home in Florence, she was invariably the greater attraction. She had a wide following among cultured readers in England and in the United States.”

More about Sonnets from the Portuguese

Encyclopedia

Jstor: The Female Poet and the Embarrassed Reader

Analysis of Sonnet 43, “How do I love thee?”

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Sonnets from the Portuguese by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

I

I thought once how Theocritus had sung

Of the sweet years, the dear and wished-for years,

Who each one in a gracious hand appears

To bear a gift for mortals, old or young:

And, as I mused it in his antique tongue,

I saw, in gradual vision through my tears,

The sweet, sad years, the melancholy years,

Those of my own life, who by turns had flung

A shadow across me. Straightway I was ’ware,

So weeping, how a mystic Shape did move

Behind me, and drew me backward by the hair;

And a voice said in mastery, while I strove,—

“Guess now who holds thee!”—“Death,” I said, But, there,

The silver answer rang, “Not Death, but Love.”

II

But only three in all God’s universe

Have heard this word thou hast said,—Himself, beside

Thee speaking, and me listening! and replied

One of us . . . that was God, . . . and laid the curse

So darkly on my eyelids, as to amerce

My sight from seeing thee,—that if I had died,

The death-weights, placed there, would have signified

Less absolute exclusion. “Nay” is worse

From God than from all others, O my friend!

Men could not part us with their worldly jars,

Nor the seas change us, nor the tempests bend;

Our hands would touch for all the mountain-bars:

And, heaven being rolled between us at the end,

We should but vow the faster for the stars.

III

Unlike are we, unlike, O princely Heart!

Unlike our uses and our destinies.

Our ministering two angels look surprise

On one another, as they strike athwart

Their wings in passing. Thou, bethink thee, art

A guest for queens to social pageantries,

With gages from a hundred brighter eyes

Than tears even can make mine, to play thy part

Of chief musician. What hast thou to do

With looking from the lattice-lights at me,

A poor, tired, wandering singer, singing through

The dark, and leaning up a cypress tree?

The chrism is on thine head,—on mine, the dew,—

And Death must dig the level where these agree.

IV

Thou hast thy calling to some palace-floor,

Most gracious singer of high poems! where

The dancers will break footing, from the care

Of watching up thy pregnant lips for more.

And dost thou lift this house’s latch too poor

For hand of thine? and canst thou think and bear

To let thy music drop here unaware

In folds of golden fulness at my door?

Look up and see the casement broken in,

The bats and owlets builders in the roof!

My cricket chirps against thy mandolin.

Hush, call no echo up in further proof

Of desolation! there’s a voice within

That weeps . . . as thou must sing . . . alone, aloof.

V

I lift my heavy heart up solemnly,

As once Electra her sepulchral urn,

And, looking in thine eyes, I over-turn

The ashes at thy feet. Behold and see

What a great heap of grief lay hid in me,

And how the red wild sparkles dimly burn

Through the ashen greyness. If thy foot in scorn

Could tread them out to darkness utterly,

It might be well perhaps. But if instead

Thou wait beside me for the wind to blow

The grey dust up, . . . those laurels on thine head,

O my Belovëd, will not shield thee so,

That none of all the fires shall scorch and shred

The hair beneath. Stand further off then! go!

VI

Go from me. Yet I feel that I shall stand

Henceforward in thy shadow. Nevermore

Alone upon the threshold of my door

Of individual life, I shall command

The uses of my soul, nor lift my hand

Serenely in the sunshine as before,

Without the sense of that which I forbore—

Thy touch upon the palm. The widest land

Doom takes to part us, leaves thy heart in mine

With pulses that beat double. What I do

And what I dream include thee, as the wine

Must taste of its own grapes. And when I sue

God for myself, He hears that name of thine,

And sees within my eyes the tears of two.

VII

The face of all the world is changed, I think,

Since first I heard the footsteps of thy soul

Move still, oh, still, beside me, as they stole

Betwixt me and the dreadful outer brink

Of obvious death, where I, who thought to sink,

Was caught up into love, and taught the whole

Of life in a new rhythm. The cup of dole

God gave for baptism, I am fain to drink,

And praise its sweetness, Sweet, with thee anear.

The names of country, heaven, are changed away

For where thou art or shalt be, there or here;

And this . . . this lute and song . . . loved yesterday,

(The singing angels know) are only dear

Because thy name moves right in what they say.

VIII

What can I give thee back, O liberal

And princely giver, who hast brought the gold

And purple of thine heart, unstained, untold,

And laid them on the outside of the wall

For such as I to take or leave withal,

In unexpected largesse? am I cold,

Ungrateful, that for these most manifold

High gifts, I render nothing back at all?

Not so; not cold,—but very poor instead.

Ask God who knows. For frequent tears have run

The colours from my life, and left so dead

And pale a stuff, it were not fitly done

To give the same as pillow to thy head.

Go farther! let it serve to trample on.

IX

Can it be right to give what I can give?

To let thee sit beneath the fall of tears

As salt as mine, and hear the sighing years

Re-sighing on my lips renunciative

Through those infrequent smiles which fail to live

For all thy adjurations? O my fears,

That this can scarce be right! We are not peers

So to be lovers; and I own, and grieve,

That givers of such gifts as mine are, must

Be counted with the ungenerous. Out, alas!

I will not soil thy purple with my dust,

Nor breathe my poison on thy Venice-glass,

Nor give thee any love—which were unjust.

Beloved, I only love thee! let it pass.

X

Yet, love, mere love, is beautiful indeed

And worthy of acceptation. Fire is bright,

Let temple burn, or flax; an equal light

Leaps in the flame from cedar-plank or weed:

And love is fire. And when I say at need

I love thee . . . mark! . . . I love thee—in thy sight

I stand transfigured, glorified aright,

With conscience of the new rays that proceed

Out of my face toward thine. There’s nothing low

In love, when love the lowest: meanest creatures

Who love God, God accepts while loving so.

And what I feel, across the inferior features

Of what I am, doth flash itself, and show

How that great work of Love enhances Nature’s.

XI

And therefore if to love can be desert,

I am not all unworthy. Cheeks as pale

As these you see, and trembling knees that fail

To bear the burden of a heavy heart,—

This weary minstrel-life that once was girt

To climb Aornus, and can scarce avail

To pipe now ’gainst the valley nightingale

A melancholy music,—why advert

To these things? O Belovëd, it is plain

I am not of thy worth nor for thy place!

And yet, because I love thee, I obtain

From that same love this vindicating grace

To live on still in love, and yet in vain,—

To bless thee, yet renounce thee to thy face.

XII

Indeed this very love which is my boast,

And which, when rising up from breast to brow,

Doth crown me with a ruby large enow

To draw men’s eyes and prove the inner cost,—

This love even, all my worth, to the uttermost,

I should not love withal, unless that thou

Hadst set me an example, shown me how,

When first thine earnest eyes with mine were crossed,

And love called love. And thus, I cannot speak

Of love even, as a good thing of my own:

Thy soul hath snatched up mine all faint and weak,

And placed it by thee on a golden throne,—

And that I love (O soul, we must be meek!)

Is by thee only, whom I love alone.

XIII

And wilt thou have me fashion into speech

The love I bear thee, finding words enough,

And hold the torch out, while the winds are rough,

Between our faces, to cast light on each?—

I drop it at thy feet. I cannot teach

My hand to hold my spirits so far off

From myself—me—that I should bring thee proof

In words, of love hid in me out of reach.

Nay, let the silence of my womanhood

Commend my woman-love to thy belief,—

Seeing that I stand unwon, however wooed,

And rend the garment of my life, in brief,

By a most dauntless, voiceless fortitude,

Lest one touch of this heart convey its grief.

XIV

If thou must love me, let it be for nought

Except for love’s sake only. Do not say

“I love her for her smile—her look—her way

Of speaking gently,—for a trick of thought

That falls in well with mine, and certes brought

A sense of pleasant ease on such a day”—

For these things in themselves, Belovëd, may

Be changed, or change for thee,—and love, so wrought,

May be unwrought so. Neither love me for

Thine own dear pity’s wiping my cheeks dry,—

A creature might forget to weep, who bore

Thy comfort long, and lose thy love thereby!

But love me for love’s sake, that evermore

Thou may’st love on, through love’s eternity.

XV

Accuse me not, beseech thee, that I wear

Too calm and sad a face in front of thine;

For we two look two ways, and cannot shine

With the same sunlight on our brow and hair.

On me thou lookest with no doubting care,

As on a bee shut in a crystalline;

Since sorrow hath shut me safe in love’s divine,

And to spread wing and fly in the outer air

Were most impossible failure, if I strove

To fail so. But I look on thee—on thee—

Beholding, besides love, the end of love,

Hearing oblivion beyond memory;

As one who sits and gazes from above,

Over the rivers to the bitter sea.

XVI

And yet, because thou overcomest so,

Because thou art more noble and like a king,

Thou canst prevail against my fears and fling

Thy purple round me, till my heart shall grow

Too close against thine heart henceforth to know

How it shook when alone. Why, conquering

May prove as lordly and complete a thing

In lifting upward, as in crushing low!

And as a vanquished soldier yields his sword

To one who lifts him from the bloody earth,

Even so, Belovëd, I at last record,

Here ends my strife. If thou invite me forth,

I rise above abasement at the word.

Make thy love larger to enlarge my worth!

XVII

My poet, thou canst touch on all the notes

God set between His After and Before,

And strike up and strike off the general roar

Of the rushing worlds a melody that floats

In a serene air purely. Antidotes

Of medicated music, answering for

Mankind’s forlornest uses, thou canst pour

From thence into their ears. God’s will devotes

Thine to such ends, and mine to wait on thine.

How, Dearest, wilt thou have me for most use?

A hope, to sing by gladly? or a fine

Sad memory, with thy songs to interfuse?

A shade, in which to sing—of palm or pine?

A grave, on which to rest from singing? Choose.

XVIII

I never gave a lock of hair away

To a man, Dearest, except this to thee,

Which now upon my fingers thoughtfully

I ring out to the full brown length and say

“Take it.” My day of youth went yesterday;

My hair no longer bounds to my foot’s glee,

Nor plant I it from rose- or myrtle-tree,

As girls do, any more: it only may

Now shade on two pale cheeks the mark of tears,

Taught drooping from the head that hangs aside

Through sorrow’s trick. I thought the funeral-shears

Would take this first, but Love is justified,—

Take it thou,—finding pure, from all those years,

The kiss my mother left here when she died.

XIX

The soul’s Rialto hath its merchandize;

I barter curl for curl upon that mart,

And from my poet’s forehead to my heart

Receive this lock which outweighs argosies,—

As purply black, as erst to Pindar’s eyes

The dim purpureal tresses gloomed athwart

The nine white Muse-brows. For this counterpart, . . .

The bay crown’s shade, Belovëd, I surmise,

Still lingers on thy curl, it is so black!

Thus, with a fillet of smooth-kissing breath,

I tie the shadows safe from gliding back,

And lay the gift where nothing hindereth;

Here on my heart, as on thy brow, to lack

No natural heat till mine grows cold in death.

XX

Belovëd, my Belovëd, when I think

That thou wast in the world a year ago,

What time I sat alone here in the snow

And saw no footprint, heard the silence sink

No moment at thy voice, but, link by link,

Went counting all my chains as if that so

They never could fall off at any blow

Struck by thy possible hand,—why, thus I drink

Of life’s great cup of wonder! Wonderful,

Never to feel thee thrill the day or night

With personal act or speech,—nor ever cull

Some prescience of thee with the blossoms white

Thou sawest growing! Atheists are as dull,

Who cannot guess God’s presence out of sight.

XXI

Say over again, and yet once over again,

That thou dost love me. Though the word repeated

Should seem a “cuckoo-song,” as thou dost treat it,

Remember, never to the hill or plain,

Valley and wood, without her cuckoo-strain

Comes the fresh Spring in all her green completed.

Belovëd, I, amid the darkness greeted

By a doubtful spirit-voice, in that doubt’s pain

Cry, “Speak once more—thou lovest!” Who can fear

Too many stars, though each in heaven shall roll,

Too many flowers, though each shall crown the year?

Say thou dost love me, love me, love me—toll

The silver iterance!—only minding, Dear,

To love me also in silence with thy soul.

XXII

When our two souls stand up erect and strong,

Face to face, silent, drawing nigh and nigher,

Until the lengthening wings break into fire

At either curvëd point,—what bitter wrong

Can the earth do to us, that we should not long

Be here contented? Think! In mounting higher,

The angels would press on us and aspire

To drop some golden orb of perfect song

Into our deep, dear silence. Let us stay

Rather on earth, Belovëd,—where the unfit

Contrarious moods of men recoil away

And isolate pure spirits, and permit

A place to stand and love in for a day,

With darkness and the death-hour rounding it.

XXIII

Is it indeed so? If I lay here dead,

Wouldst thou miss any life in losing mine?

And would the sun for thee more coldly shine

Because of grave-damps falling round my head?

I marvelled, my Belovëd, when I read

Thy thought so in the letter. I am thine—

But . . . so much to thee? Can I pour thy wine

While my hands tremble? Then my soul, instead

Of dreams of death, resumes life’s lower range.

Then, love me, Love! look on me—breathe on me!

As brighter ladies do not count it strange,

For love, to give up acres and degree,

I yield the grave for thy sake, and exchange

My near sweet view of heaven, for earth with thee!

XXIV

Let the world’s sharpness like a clasping knife

Shut in upon itself and do no harm

In this close hand of Love, now soft and warm,

And let us hear no sound of human strife

After the click of the shutting. Life to life—

I lean upon thee, Dear, without alarm,

And feel as safe as guarded by a charm

Against the stab of worldlings, who if rife

Are weak to injure. Very whitely still

The lilies of our lives may reassure

Their blossoms from their roots, accessible

Alone to heavenly dews that drop not fewer;

Growing straight, out of man’s reach, on the hill.

God only, who made us rich, can make us poor.

XXV

A heavy heart, Belovëd, have I borne

From year to year until I saw thy face,

And sorrow after sorrow took the place

Of all those natural joys as lightly worn

As the stringed pearls, each lifted in its turn

By a beating heart at dance-time. Hopes apace

Were changed to long despairs, till God’s own grace

Could scarcely lift above the world forlorn

My heavy heart. Then thou didst bid me bring

And let it drop adown thy calmly great

Deep being! Fast it sinketh, as a thing

Which its own nature does precipitate,

While thine doth close above it, mediating

Betwixt the stars and the unaccomplished fate.

XXVI

I lived with visions for my company

Instead of men and women, years ago,

And found them gentle mates, nor thought to know

A sweeter music than they played to me.

But soon their trailing purple was not free

Of this world’s dust, their lutes did silent grow,

And I myself grew faint and blind below

Their vanishing eyes. Then thou didst come—to be,

Belovëd, what they seemed. Their shining fronts,

Their songs, their splendours, (better, yet the same,

As river-water hallowed into fonts)

Met in thee, and from out thee overcame

My soul with satisfaction of all wants:

Because God’s gifts put man’s best dreams to shame.

XXVII

My own Belovëd, who hast lifted me

From this drear flat of earth where I was thrown,

And, in betwixt the languid ringlets, blown

A life-breath, till the forehead hopefully

Shines out again, as all the angels see,

Before thy saving kiss! My own, my own,

Who camest to me when the world was gone,

And I who looked for only God, found thee!

I find thee; I am safe, and strong, and glad.

As one who stands in dewless asphodel,

Looks backward on the tedious time he had

In the upper life,—so I, with bosom-swell,

Make witness, here, between the good and bad,

That Love, as strong as Death, retrieves as well.

XXVIII

My letters! all dead paper, mute and white!

And yet they seem alive and quivering

Against my tremulous hands which loose the string

And let them drop down on my knee to-night.

This said,—he wished to have me in his sight

Once, as a friend: this fixed a day in spring

To come and touch my hand . . . a simple thing,

Yet I wept for it!—this, . . . the paper’s light . . .

Said, Dear I love thee; and I sank and quailed

As if God’s future thundered on my past.

This said, I am thine—and so its ink has paled

With lying at my heart that beat too fast.

And this . . . O Love, thy words have ill availed

If, what this said, I dared repeat at last!

XXIX

I think of thee!—my thoughts do twine and bud

About thee, as wild vines, about a tree,

Put out broad leaves, and soon there’s nought to see

Except the straggling green which hides the wood.

Yet, O my palm-tree, be it understood

I will not have my thoughts instead of thee

Who art dearer, better! Rather, instantly

Renew thy presence; as a strong tree should,

Rustle thy boughs and set thy trunk all bare,

And let these bands of greenery which insphere thee,

Drop heavily down,—burst, shattered everywhere!

Because, in this deep joy to see and hear thee

And breathe within thy shadow a new air,

I do not think of thee—I am too near thee.

XXX

I see thine image through my tears to-night,

And yet to-day I saw thee smiling. How

Refer the cause?—Belovëd, is it thou

Or I, who makes me sad? The acolyte

Amid the chanted joy and thankful rite

May so fall flat, with pale insensate brow,

On the altar-stair. I hear thy voice and vow,

Perplexed, uncertain, since thou art out of sight,

As he, in his swooning ears, the choir’s amen.

Belovëd, dost thou love? or did I see all

The glory as I dreamed, and fainted when

Too vehement light dilated my ideal,

For my soul’s eyes? Will that light come again,

As now these tears come—falling hot and real?

XXXI

Thou comest! all is said without a word.

I sit beneath thy looks, as children do

In the noon-sun, with souls that tremble through

Their happy eyelids from an unaverred

Yet prodigal inward joy. Behold, I erred

In that last doubt! and yet I cannot rue

The sin most, but the occasion—that we two

Should for a moment stand unministered

By a mutual presence. Ah, keep near and close,

Thou dove-like help! and when my fears would rise,

With thy broad heart serenely interpose:

Brood down with thy divine sufficiencies

These thoughts which tremble when bereft of those,

Like callow birds left desert to the skies.

XXXII

The first time that the sun rose on thine oath

To love me, I looked forward to the moon

To slacken all those bonds which seemed too soon

And quickly tied to make a lasting troth.

Quick-loving hearts, I thought, may quickly loathe;

And, looking on myself, I seemed not one

For such man’s love!—more like an out-of-tune

Worn viol, a good singer would be wroth

To spoil his song with, and which, snatched in haste,

Is laid down at the first ill-sounding note.

I did not wrong myself so, but I placed

A wrong on thee. For perfect strains may float

’Neath master-hands, from instruments defaced,—

And great souls, at one stroke, may do and doat.

XXXIII

Yes, call me by my pet-name! let me hear

The name I used to run at, when a child,

From innocent play, and leave the cowslips plied,

To glance up in some face that proved me dear

With the look of its eyes. I miss the clear

Fond voices which, being drawn and reconciled

Into the music of Heaven’s undefiled,

Call me no longer. Silence on the bier,

While I call God—call God!—so let thy mouth

Be heir to those who are now exanimate.

Gather the north flowers to complete the south,

And catch the early love up in the late.

Yes, call me by that name,—and I, in truth,

With the same heart, will answer and not wait.

XXXIV

With the same heart, I said, I’ll answer thee

As those, when thou shalt call me by my name—

Lo, the vain promise! is the same, the same,

Perplexed and ruffled by life’s strategy?

When called before, I told how hastily

I dropped my flowers or brake off from a game.

To run and answer with the smile that came

At play last moment, and went on with me

Through my obedience. When I answer now,

I drop a grave thought, break from solitude;

Yet still my heart goes to thee—ponder how—

Not as to a single good, but all my good!

Lay thy hand on it, best one, and allow

That no child’s foot could run fast as this blood.

XXXV

If I leave all for thee, wilt thou exchange

And be all to me? Shall I never miss

Home-talk and blessing and the common kiss

That comes to each in turn, nor count it strange,

When I look up, to drop on a new range

Of walls and floors, another home than this?

Nay, wilt thou fill that place by me which is

Filled by dead eyes too tender to know change

That’s hardest. If to conquer love, has tried,

To conquer grief, tries more, as all things prove,

For grief indeed is love and grief beside.

Alas, I have grieved so I am hard to love.

Yet love me—wilt thou? Open thy heart wide,

And fold within, the wet wings of thy dove.

XXXVI

When we met first and loved, I did not build

Upon the event with marble. Could it mean

To last, a love set pendulous between

Sorrow and sorrow? Nay, I rather thrilled,

Distrusting every light that seemed to gild

The onward path, and feared to overlean

A finger even. And, though I have grown serene

And strong since then, I think that God has willed

A still renewable fear . . . O love, O troth . . .

Lest these enclaspëd hands should never hold,

This mutual kiss drop down between us both

As an unowned thing, once the lips being cold.

And Love, be false! if he, to keep one oath,

Must lose one joy, by his life’s star foretold.

XXXVII

Pardon, oh, pardon, that my soul should make

Of all that strong divineness which I know

For thine and thee, an image only so

Formed of the sand, and fit to shift and break.

It is that distant years which did not take

Thy sovranty, recoiling with a blow,

Have forced my swimming brain to undergo

Their doubt and dread, and blindly to forsake

Thy purity of likeness and distort

Thy worthiest love to a worthless counterfeit.

As if a shipwrecked Pagan, safe in port,

His guardian sea-god to commemorate,

Should set a sculptured porpoise, gills a-snort

And vibrant tail, within the temple-gate.

XXXVIII

First time he kissed me, he but only kissed

The fingers of this hand wherewith I write;

And ever since, it grew more clean and white.

Slow to world-greetings, quick with its “O, list,”

When the angels speak. A ring of amethyst

I could not wear here, plainer to my sight,

Than that first kiss. The second passed in height

The first, and sought the forehead, and half missed,

Half falling on the hair. O beyond meed!

That was the chrism of love, which love’s own crown,

With sanctifying sweetness, did precede

The third upon my lips was folded down

In perfect, purple state; since when, indeed,

I have been proud and said, “My love, my own.”

XXXIX

Because thou hast the power and own’st the grace

To look through and behind this mask of me,

(Against which, years have beat thus blanchingly,

With their rains,) and behold my soul’s true face,

The dim and weary witness of life’s race,—

Because thou hast the faith and love to see,

Through that same soul’s distracting lethargy,

The patient angel waiting for a place

In the new Heavens,—because nor sin nor woe,

Nor God’s infliction, nor death’s neighbourhood,

Nor all which others viewing, turn to go,

Nor all which makes me tired of all, self-viewed,—

Nothing repels thee, . . . Dearest, teach me so

To pour out gratitude, as thou dost, good!

XL

Oh, yes! they love through all this world of ours!

I will not gainsay love, called love forsooth:

I have heard love talked in my early youth,

And since, not so long back but that the flowers

Then gathered, smell still. Mussulmans and Giaours

Throw kerchiefs at a smile, and have no ruth

For any weeping. Polypheme’s white tooth

Slips on the nut if, after frequent showers,

The shell is over-smooth,—and not so much

Will turn the thing called love, aside to hate

Or else to oblivion. But thou art not such

A lover, my Belovëd! thou canst wait

Through sorrow and sickness, to bring souls to touch,

And think it soon when others cry “Too late.”

XLI

I thank all who have loved me in their hearts,

With thanks and love from mine. Deep thanks to all

Who paused a little near the prison-wall

To hear my music in its louder parts

Ere they went onward, each one to the mart’s

Or temple’s occupation, beyond call.

But thou, who, in my voice’s sink and fall

When the sob took it, thy divinest Art’s

Own instrument didst drop down at thy foot

To harken what I said between my tears, . . .

Instruct me how to thank thee! Oh, to shoot

My soul’s full meaning into future years,

That they should lend it utterance, and salute

Love that endures, from life that disappears!

XLII

My future will not copy fair my past—

I wrote that once; and thinking at my side

My ministering life-angel justified

The word by his appealing look upcast

To the white throne of God, I turned at last,

And there, instead, saw thee, not unallied

To angels in thy soul! Then I, long tried

By natural ills, received the comfort fast,

While budding, at thy sight, my pilgrim’s staff

Gave out green leaves with morning dews impearled.

I seek no copy now of life’s first half:

Leave here the pages with long musing curled,

And write me new my future’s epigraph,

New angel mine, unhoped for in the world!

XLIII

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of Being and ideal Grace.

I love thee to the level of everyday’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candlelight.

I love thee freely, as men strive for Right;

I love thee purely, as they turn from Praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints,—I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life!—and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

XLIV

Belovëd, thou hast brought me many flowers

Plucked in the garden, all the summer through,

And winter, and it seemed as if they grew

In this close room, nor missed the sun and showers.

So, in the like name of that love of ours,

Take back these thoughts which here unfolded too,

And which on warm and cold days I withdrew

From my heart’s ground. Indeed, those beds and bowers

Be overgrown with bitter weeds and rue,

And wait thy weeding; yet here’s eglantine,

Here’s ivy!—take them, as I used to do

Thy flowers, and keep them where they shall not pine.

Instruct thine eyes to keep their colours true,

And tell thy soul, their roots are left in mine.

The post Sonnets from the Portuguese by Elizabeth Barrett Browning (full text) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 29, 2020

Helen Hunt Jackson

Helen Hunt Jackson (born Helen Maria Fiske, October 15, 1830 – August 12, 1885), was an American novelist, poet, and writer of nonfiction. She gained fame as an advocate of Native Americans, using her pen and her voice to expose their disgraceful treatment by the U.S. government.

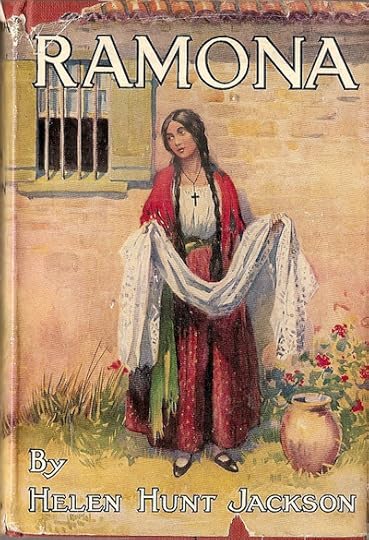

Her best-known novel, Ramona (1884), called attention to the mistreatment of Native Americans, much as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1882) raised awareness of the evils of slavery.

Though Ramona is no longer as widely known as the latter, it was hugely successful in its time, going through hundreds of editions. And though the intent behind both Ramona and Uncle Tom’s Cabin could smack of white saviorism, they were the most widely read “moral novels” of the 19th century. The two authors fervently believed in the causes that propelled their writings.

Born and raised in Amherst, MA, Helen was a girlhood friend (and neighbor) of Emily Dickinson, who wouldn’t become a world-renowned poet until after both women had died. Today, the home in which she spent her early life is at 249 South Pleasant Street, is part of Amherst College.

The following excellent (if somewhat sentimental) biography has been adapted from Lives of Girls Who Became Famous by Sarah K. Bolton, 1914:

Thousands were saddened when, Aug. 12, 1885, it was flashed across the wires that Helen Hunt Jackson was dead. The Nation said, “The news will probably carry a pang of regret into more American homes than similar intelligence in regard to any other woman, with the possible exception of Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe.”

Mrs. Jackson’s literary work will be abiding, but her life, with its dark shadow and bright sunlight, its deep affections and sympathy with the oppressed, will furnish a rich setting for the gems of thought which she gave to the world.

Childhood

Born Helen Maria Fiske in the cultured town of Amherst, Massachusetts, she inherited from her mother a sunny, buoyant nature, and from her father, Nathan W. Fiske, professor of languages and philosophy in the college, a strong and vigorous mind.

When Helen was in her early teens, both her father and mother died of tuberculosis, leaving her to the care of a grandfather. She was soon placed in the school of the author Reverend J.S.C. Abbott, of New York, and here some of her happiest days were passed. She grew to womanhood, frank, merry, impulsive, brilliant in conversation, and fond of society.

Young womanhood

At twenty-one, Helen married a young army officer, Captain (and later Major) Edward B. Hunt, whom his friends called “Cupid” Hunt from his handsome looks and curling hair. He was a brother of Governor Washington Hunt of New York, an engineer of high rank, and a man of fine scientific attainments.

They lived much of their time at West Point and Newport. The young wife moved in a fashionable social circle and won hosts of admiring friends. Now and then, when he read a paper before some learned society, he was proud to take his vivacious and attractive wife with him.

Their first baby died when he was eleven months old, but another beautiful boy came to take his place, named after two friends, Warren Horsford, but familiarly called “Rennie.” He was an uncommonly bright child, and Mrs. Hunt was passionately fond and proud of him. Life seemed full of pleasures. She dressed handsomely, and no wish of her heart seemed ungratified.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A shattered life

Suddenly, like a thunderbolt from a clear sky, the happy life was shattered. Major Hunt was killed Oct. 2, 1863, while experimenting in Brooklyn with a submarine gun of his own invention.

The young widow still had her eight-year-old boy, and she clung to him more tenderly than ever. But in less than two years, she stood by his dying bed. Seeing the agony of his mother, and forgetting his own even in that dread destroyer, diphtheria, he said, almost at the last moment, “Promise me, mamma, that you will not kill yourself.”

She promised, and exacted from him also a pledge that if it were possible, he would come back from the other world to talk with his mother. He never came, and Mrs. Hunt could have no faith in spiritualism because what Rennie could not do, she believed to be impossible.

For months she shut herself into her room, refusing to see her nearest friends. “Anyone who really loves me ought to pray that I may die, too, like Rennie,” she said. Her physician thought she would die of grief; but when her strong, earnest nature had wrestled with itself and come off conqueror, she came out of her seclusion, cheerful as of old. The pictures of her husband and boy were ever beside her, and these doubtless spurred her on to the work she was to accomplish.

A bereaved mother’s poem

Three months after Rennie’s death, her first poem, Lifted Over, appeared in the Nation:

As tender mothers, guiding baby steps,

When places come at which the tiny feet

Would trip, lift up the little ones in arms

Of love, and set them down beyond the harm,

So did our Father watch the precious boy,

Led o’er the stones by me, who stumbled oft

Myself, but strove to help my darling on:

He saw the sweet limbs faltering, and saw

Rough ways before us, where my arms would fail;

So reached from heaven, and lifting the dear child,

Who smiled in leaving me, He put him down

Beyond all hurt, beyond my sight, and bade

Him wait for me! Shall I not then be glad,

And, thanking God, press on to overtake!”

The poem was widely copied, and many mothers were comforted by it. The kind letters she received in consequence were the first gleam of sunshine in the darkened life. If she were doing even a little good, she could live and be strong.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The start of a literary career

Then began, at thirty-four, absorbing and painstaking literary work. She studied the best models of composition and found it most helpful to study the works of Wentworth Higginson.

Her first prose sketch, “A Walk Up Mt. Washington from the Glen House,” appeared in the Independent, Sept. 13, 1866; and from this time she wrote for that able journal three hundred and seventy-one articles.

She worked rapidly, writing usually with a lead-pencil, on large sheets of yellow paper, but she pruned carefully. Her first poem in the Atlantic Monthly, entitled Coronation, delicate and full of meaning, appeared in 1869, being taken to Mr. Fields, the editor, by a friend.

At this time she spent a year abroad, principally in Germany and Italy, writing home several sketches. In Rome, she became so ill that her life hung by a thread. When she was partially recovered and went away to regain her strength, her friends insisted that a professional nurse should go with her; but she took a hard-working young Italian girl of sixteen, to whom this vacation would be a blessing.

First publications

In 1870, on Helen’s return from Europe, a little book of Verses was published. Like most beginners, she was obliged to pay for the stereotyped plates. The book was well received. Ralph Waldo Emerson liked especially her sonnet, Thought. He ranked her poetry above that of all American women, and most American men.

Some persons praised the “exquisite musical structure” of “Gondoliers,” and others read and re-read her beautiful “Down to Sleep.” But the world’s favorite was “Spinning”:

Like a blind spinner in the sun,

I tread my days;

I know that all the threads will run

Appointed ways;

I know each day will bring its task,

And, being blind, no more I ask.

But listen, listen, day by day,

To hear their tread

Who bear the finished web away,

And cut the thread,

And bring God’s message in the sun,

“Thou poor blind spinner, work is done.’

After this came two other small books, Bits of Travel and Bits of Talk about Home Matters. She paid for the plates of the former. Fame did not burst upon Helen Hunt; it came after years of work after it had been fully earned. The road to authorship is a hard one, and only those should attempt it who have courage and perseverance.

A second marriage

Eleven years after the death of Major Hunt, in 1876, Helen married Mr. William Sharpless Jackson, a Quaker and a cultured banker. Their home in Colorado Springs, became an ideal one, sheltered under the great Manitou, and looking toward the Garden of the Gods, full of books and magazines, of dainty rugs and dainty china gathered from many countries, and richly colored Colorado flowers.

The new Mrs. Jackson loved flowers almost as though they were children. She wrote:

“I bore on this June day a sheaf of the white columbine — one single sheaf, one single root; but it was almost more than I could carry. In the open spaces, I carried it on my shoulder; in the thickets, I bore it carefully in my arms, like a baby …

There is a part of Cheyenne Mountain which I and one other have come to call ‘our garden.’ When we drive down from ‘our garden,’ there is seldom room for another flower in our carriage. The top thrown back is filled, the space in front of the driver is filled, and our laps and baskets are filled with the more delicate blossoms.

We look as if we were on our way to the ceremonies of Decoration Day. So we are. All June days are decoration days in Colorado Springs, but it is the sacred joy of life that we decorate — not the sacred sadness of death.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A budding novelist and advocate for Native Americans

But Mrs. Jackson, with her pleasant home, could not rest from her work. Two novels came from her pen, Mercy Philbrick’s Choice and Hetty’s Strange History. It is probable also that she helped to write the beautiful and tender Saxe Holm Stories.

The time had now come for her to do her last and perhaps her best work. She could not write without a definite purpose, and now the purpose that settled down upon her heart was to help the defrauded Indians.

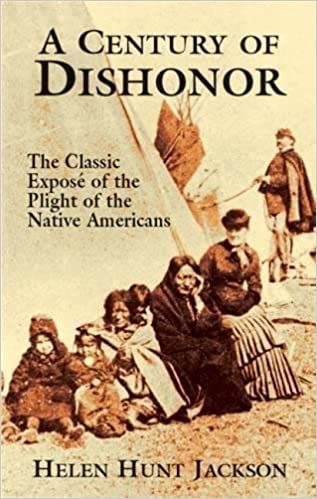

She left her home and spent three months in the Astor Library of New York, writing her Century of Dishonor, showing how we have despoiled the Indians and broken our treaties with them. She wrote to a friend, “I cannot think of anything else from night to morning and from morning to night.” So untiringly did she work that she made herself ill.

At her own expense, she sent a copy to each member of Congress. Its plain facts were not relished in some quarters, and she began to taste the cup that all reformers have to drink; but the brave woman never flinched in her duty. So much was the Government impressed by her earnestness and good judgment, that she was appointed a Special Commissioner with her friend, Abbott Kinney, to examine and report on the condition of the Mission Indians in California.

Could an accomplished, tenderly reared woman go into their adobe villages and listen to their wrongs? What would the world say of its poet? Mrs. Jackson did not ask; she had a mission to perform, and the more culture, the more responsibility. She brought cheer and hope to the Native American men and their wives, and they called her “the Queen.” She wrote able articles about them in the Century.

The report made by Mr. Kinney and herself, which she prepared largely, was clear and convincing. How different all this from her early life! Mrs. Jackson had become more than a poet and novelist; even the leader of an oppressed people.

At once, in the winter of 1883, she began to write her wonderfully graphic and tender Ramona, and into this, she said, “I put my heart and soul.” The book was immediately reprinted in England, and has had great popularity. She meant to do for the American Indian what Mrs. Stowe did for the slave, and she lived long enough to see the great work well in progress.

An injury and last letters

In June 1884, falling on the staircase of her Colorado home, she severely fractured her leg and was confined to the house for several months. Then she was taken to Los Angeles for the winter. The broken limb mended rapidly, but malarial fever set in, and she was carried to San Francisco. Her first remark was, as she entered the house looking out upon the broad and lovely bay, “I did not imagine it was so pleasant! What a beautiful place to die in!”

To the last, her letters to her friends were full of cheer. She wrote:

“You must not think because I speak of not getting well that I am sad over it,” she wrote. “On the contrary, I am more and more relieved in my mind, as it seems to grow more and more sure that I shall die. You see that I am growing old [she was but fifty-four], and I do believe that my work is done.

You have never realized how, for the past five years, my whole soul has been centered on the Indian question. Ramona was the outcome of those five years. The Indian cause is on its feet now; powerful friends are at work.”

To another, she wrote:

“I am heartily, honestly, and cheerfully ready to go. In fact, I am glad to go. My Century of Dishonor and Ramona are the only things I have done of which I am glad now. The rest is of no moment. They will live, and they will bear fruit. They already have. The change in public feeling on the Indian question in the last three years is marvelous; an Indian Rights Association in every large city in the land.”

She had no fear of death. She said, “It is only just passing from one country to another … My only regret is that I have not accomplished more work; especially that it was so late in the day when I began to work in real earnest.”

A peaceful departure

Four days before she died, she wrote to President Cleveland:

“From my death-bed I send you a message of heartfelt thanks for what you have already done for the Indians. I ask you to read my Century of Dishonor. I am dying happier for the belief I have that it is your hand that is destined to strike the first steady blow toward lifting this burden of infamy from our country, and righting the wrongs of the Indian race.

With respect and gratitude, Helen Jackson”

That evening, Aug. 8, after saying farewell, she placed her hand in her husband’s, and went to sleep. After four days, mostly unconscious ones, she wakened in eternity.

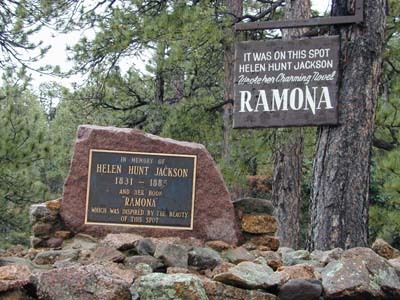

On her coffin were laid a few simple clover-blossoms, flowers she loved in life; and then, near the summit of Cheyenne Mountain, four miles from Colorado Springs, in a spot of her own choosing, she was buried.

Do not adorn with costly shrub or tree

Or flower the little grave which shelters me.

Let the wild wind-sown seeds grow up unharmed,

And back and forth all summer, unalarmed,

Let all the tiny, busy creatures creep;

Let the sweet grass its last year’s tangles keep;

And when, remembering me, you come some day

And stand there, speak no praise, but only say,

‘How she loved us! It was for that she was so dear.’

These are the only words that I shall smile to hear.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Helen Hunt Jackson’s legacy

All honor a woman who, with a happy home, was willing to leave it to make other homes happy; who, having suffered, tried with a sympathetic heart to forget herself and keep others from suffering; who, being famous, gladly took time to help unknown authors to win fame; who, having means, preferred a life of labor to a life of ease.

Helen Hunt Jackson’s work was republished in numerous editions, reaching generations of readers, especially with Century of Dishonor and Ramona. Zeph, a touching story of frontier life in Colorado, which she finished in her last illness, was also widely read. Her sketches of travel have been gathered into Glimpses of Three Coasts, and a posthumous volume of poems, Sonnets and Lyrics, was published.

. . . . . . . . . .

Helen Hunt Jackson Memorial in Seven Falls, Colorado

More about Helen Hunt Jackson

Schools, libraries, portions of parks, and more, have been named in honor of Helen Hunt Jackson’s legacy. A majority of her papers are archived at Colorado College, and some of her papers are also archived in the NY Public Library, She was inducted into the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame in 1985

Selected works

Bits of Travel (1872)

Bits about Home Matters (1873)

Saxe Holm’s Stories (1874)

The Story of Boon (1874)

Mercy Philbrick’s Choice (1876)

Hetty’s Strange History (1877)

Bits of Talk in Verse and Prose for Young Folks (1876)

Bits of Travel at Home (1878)

Nelly’s Silver Mine: A Story of Colorado Life (1878)

Letters from a Cat (1879)

A Century of Dishonor (1881)

Ramona (1884)

Zeph: A Posthumous Story (1885)

Glimpses of Three Coasts (1886)

Between Whiles (1888)

A Calendar of Sonnets (1891)

Ryan Thomas (1892)

The Hunter Cats of Connorloa (1894)

Poems by Helen Jackson Roberts Bros, Boston (1893)

Pansy Billings and Popsy: Two Stories of Girl Life (1898)

Glimpses of California (1914)

Biographies

Helen Hunt Jackson by Ruth Webb O’Dell, 1939

Helen Hunt Jackson by Evelyn I. Banning, 1973

Helen Hunt Jackson: A Lonely Voice of Conscience by Antoinette May, 1987

Valerie Sherer Mathes, Helen Hunt Jackson and Her Indian Reform Legacy, 1992

Helen Hunt Jackson: Selected Colorado Writings, Mark I. West., ed., 2002

Helen Hunt Jackson: A Literary Life, Kate Phillips, 2003

Indian Reform Letters of Helen Hunt Jackson, 1879 – 1885, Valerie Sherer Mathes, ed., 2015

Read and listen online

Helen Hunt Jackson’s works on Project Gutenberg

Listen to audio versions on Librivox

More information and Sources

Wikipedia

Poetry Foundation

Reader discussion of Helen Hunt Jackson’s works on Goodreads

Helen Hunt Jackson papers at Colorado College

. . . . . . . . . .

The post Helen Hunt Jackson appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 25, 2020

Nets to Catch the Wind by Elinor Wylie (1921) – full text