Nava Atlas's Blog, page 44

March 18, 2021

Elizabeth Cary, Early English Poet, Dramatist, and Scholar

Elizabeth Cary, also known as Viscountess Falkland (1585–1639), was an English poet, dramatist, and scholar. Thought to be the first woman to have written and published a play in English (The Tragedy of Mariam, detailed below), she was acknowledged as an accomplished scholar in her lifetime. This introduction to Elizabeth Cary’s life and work is excerpted from Killing the Angel: Early Transgressive British Woman Writers by Francis Booth ©2021, reprinted by permission.

According to the biography of Elizabeth Cary (née Tanfield, Viscountess Falkland, written by one of her daughters after her death, was quite highly educated, though largely self-taught. Although she had some distinguished tutors she taught herself mainly from books.

. . . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Cary, Viscountess Falkland

. . . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth did get a tutor in French at the age of five and according to her biographer-daughter she was speaking it fluently just a few weeks later; she then taught herself Spanish, Italian, Latin, and Hebrew.

Elizabeth nevertheless seems to have been an obedient rather than a transgressive daughter and having been married off young, to have been an obedient wife, initially at least; she had eleven children by her husband. She was only fifteen at the time of the marriage and it seems that Henry, Viscount Falkland only married her because she was an heiress.

She had read very exceeding much; poetry of all kinds, ancient and modern, in several languages, all that ever she could meet; history very universally, especially all ancient Greek and Roman historians; all chroniclers whatsoever in her own country, and the French histories very thoroughly; of most other countries something, though not so universally; of the ecclesiastical history very much, most especially concerning its chief pastors.

Of books treating of moral virtue or wisdom (such as Seneca, Plutarch’s Morals, and natural knowledge, as Pliny, and of late ones such as French, Montaigne, and English, Bacon), she had read very many when she was young, not without making her profit of them all. (The Lady Falkland: Her Life)

In her husband’s many absences – Henry was at various times Gentleman of the Bedchamber, Member of Parliament for Hertfordshire, a Justice of the Peace, Master of the Jewels, Comptroller of the Household, and a Privy Councillor – Elizabeth was forced to live with her mother-in-law, who took away all her books.

Since she was not allowed to read books anymore, she decided to transgress her mother-in-law’s, her husband’s, and society’s will and write her own books instead; according to Her Life, Cary was one of the most prolific female authors of her time. She wrote two plays, a life of Tamburlaine and biographies in verse of Saint Mary Magdalene, Saint Agnes and Saint Elizabeth of Portugal.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Killing the Angel on Amazon US*

Killing the Angel on Amazon UK*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Cary’s most famous work is The Tragedy of Mariam, printed in 1613 but written earlier, which may be the first original English play to have been published by a woman. It is what became known as a ‘closet drama,’ implying that it was not intended to be performed on a stage, but perhaps to be read out loud by friends; such things regularly happened in Mary Sidney’s Wilton House circle.

Mariam is written in formal, rhyming iambic pentameter, a relatively new form at the time, and a specifically English form, different from the classical and French metres. Marlowe had first perfected iambic pentameter, followed by Shakespeare, but they mostly used unrhymed lines, known as blank verse; Shakespeare’s Sonnets though, published together in 1609, do use rhyming iambic pentameter.

Mariam is the wife of King Herod from the Bible and the central character; it is very unusual for a play of the time to have a female as the sole title character – very unusual for a play of any time. Even more unusually, there are two strong female leads: Mariam and her sister-in-law, Salome – in this case, Herod’s sister not his stepdaughter as in Oscar Wilde’s play.

As in Wilde’s version, Salome is the bad girl, though not in a lustful, sexual sense; John the Baptist’s head does not appear. Salome here is more like Iago in Othello, 1604, telling lies to a jealous, dark-skinned husband about his pale-skinned wife, seeding suspicion, leading to him having her killed. In contrast, Mariam is the good girl, though she is rather too proud of her own famous beauty and she has earlier taken Herod away from his previous wife, Doris, in adulterous transgression of what was then accepted as the laws of God.

DORIS

I’heaven? Your beauty cannot bring you thither.

Your soul is black and spotted, full of sin;

You in adultery lived nine years together,

And heaven will never let adultery in.

Although she does not do the dance of the seven veils, Salome is in her own way quite transgressive, plotting against her sister-in-law and insisting on a woman’s equality; the following passage sounds like a cry from the author’s own heart.

Why should such privilege to man be given?

Or, given to them, why barred from women then?

Are men than we in greater grace with heaven?

Or cannot women hate as well as men?

I’ll be the custom-breaker and begin

To show my sex the way to freedom’s door

Again, very unusually for the time – or any time – Cary writes powerful scenes involving two strong, opposed women, with no men involved. Salome resents Mariam for having married her brother; Mariam looks down on Salome for her low birth and resents her interference in her marriage.

At one point in the play, both women believe that Herod has died abroad; Salome thinks Mariam is pleased to be rid of her husband and ‘hopes to have another King; her eyes do sparkle joy for Herod’s death.’

SALOME

You durst not thus have given your tongue the rein

If noble Herod still remained in life.

Your daughter’s betters far, I dare maintain,

Might have rejoiced to be my brother’s wife.

MARIAM

My ‘betters far’? Base woman, ‘tis untrue!

You scarce have ever my superiors seen,

For Mariam’s servants were as good as you

Before she came to be Judea’s queen.

SALOME

Now stirs the tongue that is so quickly moved;

But more than once your choler have I borne,

Your fumish words are sooner said than proved,

And Salome’s reply is only scorn.

MARIAM

Scorn those that are for thy companions held!

Though I thy brother’s face have never seen,

My birth thy baser birth so far excelled,

I had to both of you the princess been.

Thou parti-Jew and parti-Edomite,

Thou mongrel, issued from rejected race!

Typical antisemitism and racism

The casual anti-Semitism here is probably no worse than in Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta, 1590 or Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, first performed in 1605. There were very few Jews living in England at the time, probably all in London and mostly of Mediterranean descent, a small diaspora escaping Catholic France and Spain (the Spanish Inquisition had begun in the 1480s; in 1483, Jews were expelled from all of Andalusia and royal decrees were issued in 1492 and 1502 ordering Muslims and Jews to convert to Catholicism or leave Castile).

In England, Jews were not welcome either, but English Protestants mostly saw Jews as lost souls waiting to be converted rather than burned in autos da fé (not that the English were averse to burning heretics, as we saw with Anne Askew). John Foxe, famous as the author of The Book of Martyrs, 1563 also published A Sermon Preached at the Christening of a Certain Jew at London, 1578.

The introduction says that it contains ‘a refutation of the obstinate Jews, and lastly touching the final conversion of the same.’ Some people in England went even further in their anti-Semitism though: a 1569 book called Certaine secrete wonders of Nature had accused Jews of poisoning Christian wells and in 1594, Queen Elizabeth’s Portuguese Jewish doctor was accused of plotting to poison her in collaboration with the Spanish.

As for the racism that equates Salome’s slipperiness with her dark skin, echoed by her own husband’s comparison of her to Mariam: ‘you are to her as a sunburnt blackamoor,’ Cary was reflecting the racism and xenophobia of her time.

A draft of a Royal Proclamation of 1601 under Elizabeth I commands expulsion of all ‘negroes and blackamoors,’ many of them Muslims who, like the Jews, were escaping persecution in the Catholic countries of Europe; Elizabeth’s government blamed immigrants for their economic problems, as governments will, and a German merchant had been hired to track them down and deport them.

WHEREAS the Queen’s majesty, tendering the good and welfare of her own natural subjects, greatly distressed in these hard times of dearth, is highly discontented to understand the great number of Negroes and blackamoors which (as she is informed) are carried into this realm since the troubles between her highness and the King of Spain . . . These shall therefore be to will and require you and every one of you to . . . taking such Negroes and blackamoors to be transported as aforesaid as he shall find within the realm of England.

. . . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

5 Early English Women Writers to Discover

. . . . . . . . . . .

In 1625, Elizabeth Cary herself converted to Catholicism, a deeply transgressive act, against both her husband’s will and the laws of the land; Catholics were still treated with extreme suspicion twenty years after the Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

The Act for Restraining Popish Recusants (Catholics who refused to attend Church of England services) to Some Certain Place of Abode had been passed in 1593; then in 1606 a law had been passed requiring all persons to ‘receive the sacrament in the church of the parish where his abroad is, or if there be no such Parish Church then in the church of the next Parish.’

Elizabeth’s husband took away everything from her, including her children, just leaving her with one servant and tried to divorce her; since she had been disinherited by her father, Elizabeth had to apply to the Privy Council to try to force her husband to maintain her financially, but he refused, hoping to make her recant. She won in the end, though: after his death, she converted most of her children to Catholicism; four of the girls became nuns, and one of her sons became a priest.

Along with Mary Sidney, Elizabeth Cary was praised at length by John Davies – he and Michael Drayton were probably her tutors as a girl – in the dedication to his The Muses Sacrifice, 1612 (before Mariam was printed, implying he had read it in manuscript).

CARY (of whom Minerva stands in fear,

lest she, from her, should get ART’S Regency)

Of ART so moues the great-all-moving Sphere,

that every Ore of Science moves thereby.

Thou makest Melpomen proud, and my Heart great

of such a Pupil, who, in Buskin fine,

With Feet of State, dost make thy Muse to mete

the Scenes of Syracuse and Palestine.

Art, Language; yea; abstruse and holy Tongues,

thy Wit and Grace acquired thy Fame to raise;

And still to fill thine own, and others Songs;

thine, with thy Parts, and others, with thy praise

Such nervy Limbs of Art, and Strains of Wit

Times past ne’er knew the weaker Sex to have;

And Times to come, will hardly credit it,

if thus thou give thy Works both Birth and Grave.

More about Elizabeth Cary

More biographical information on Wikipedia More about The Tragedy of Mariam The Tragedy of Mariam (full text) Catalog of English Literary Manuscripts. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

The Matchless Orinda: Early English Poet & Playwright Katherine Philips

. . . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Elizabeth Cary, Early English Poet, Dramatist, and Scholar appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 17, 2021

The Matchless Orinda — Early English Poet & Playwright Katherine Philips

Known as the “Matchless Orinda,” Katherine Philips (1631/2 – 1664; née Fowler) was the author of the first English-language play written by a woman to be performed on the professional stage and she may also have been the first published lesbian poet in the English language; this seems to be a love poem from her to fellow poet Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea, whose pseudonym was Ardelia.

This introduction to Katherine Philips’ life and work is adapted from Killing the Angel: Early Transgressive British Woman Writers by Francis Booth ©2021, reprinted by permission.

Come, my Ardelia, to this bower,

Where kindly mingling Souls awhile,

Let’s innocently spend an hour

and at all serious follies smile. . .

Why should we entertain a fear?

Love cares not how the world is turned:

If crowds of dangers should appear,

Yet friendship can be unconcerned.

We wear about us such a charm,

No horror can be our offence;

For mischief’s self can do no harm

To friendship and to innocence.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Killing the Angel on Amazon US*

Killing the Angel on Amazon UK*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Born to a cloth merchant in the City of London, England, Katherine Philips was a precocious learner; it was said that she could read the Bible by the age of four. From the age of around eight to sixteen she was sent to a boarding school in Hackney in East London, a centre for women’s education at the time, where she learned several languages.

At sixteen Katherine was married to an older, Welsh parliamentarian; he died only eight years later but the couple had two children, only one of whom survived.

Philips’ home in Cardiff became the centre of the Society of Friendship, which Philips founded in 1651 based on the ideals of platonic friendship from French pastoral romance; the members all gave themselves suitably pastoral names.

The Society was a literary association made up mostly of women, though there were also male members, including the poet Henry Vaughan: Philips’ first published work was a preface to his poems in 1651. It is not certain exactly who the members were, since they all used their pastoral pseudonyms; using these names of course meant that the women were not publishing under either their husband’s or their father’s name and could choose to stay anonymous.

. . . . . . . . .

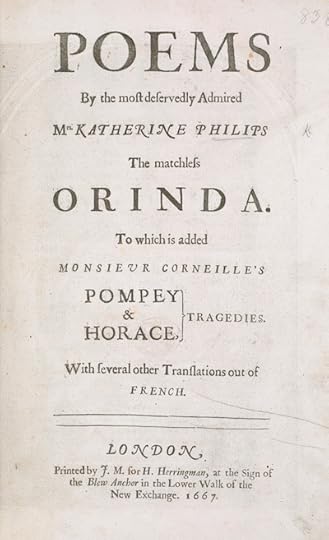

Poems by Mrs Katherine Philips, the Matchless Orinda

. . . . . . . . .

We do, however, know of the membership of Mary Awbrey (Rosania), Elizabeth Boyle (Celimena) and of Anne Owen, called Lucasia, to whom many of Philips’ poems are dedicated. This next poem is called, “To the Excellent Mrs. Anne Owen, upon her receiving the name Of Lucasia, and Adoption into our Society, December 28, 1651.”

WE are complete, and Fate hath now

No greater blessing to bestow;

Nay, the dull World must now confess,

We have all worth, all happiness.

Annals of State are trifles to our fame,

Now ‘tis made sacred by Lucasia’s name.

Although the society was founded on platonic ideals, Philips’ feelings for Lucasia seem to go beyond the platonic in many of the poems, including ‘To My Excellent Lucasia, on Our Friendship.’

I did not live until this time

Crowned in my felicity,

When I could say without a crime,

I am not thine, but thee. . .

For thou art all that I can prize,

My joy, my life, my rest.

No bridegroom’s nor crown-conqueror’s mirth

To mine compared can be:

They have but pieces of the earth,

I’ve all the world in thee.

Although she was only possibly the first published lesbian poet in English, Philips was certainly the author of the first English-language play written by a woman to be performed professionally, even though it was only a translation; earlier ‘closet dramas’ like Elizabeth Cary’s Mariam were not written for public performance.

While living in Dublin, the francophone Philips translated Pierre Corneille’s play Pompée, which was staged successfully in 1663 in Dublin’s Smock Alley Theatre, founded the previous year; the play was printed in both Dublin and London under the title Pompey. Although other women had translated or written dramas before, Philips’ translation of Pompée broke new ground as the first rhymed version of a French tragedy to be published in English.

. . . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

5 Early English Women Writers to Discover

. . . . . . . . . . .

In 1664, an edition of Philips’ poetry entitled Poems by the Incomparable Mrs. K.P. was published but it was not authorized by her and was full of errors; Philips died of smallpox that year and the City of London church in which she was buried was destroyed two years later in the Great Fire of London.

It was not until 1667 that an authorized edition of her poems was published posthumously, entitled Poems by the Most Deservedly Admired Mrs. Katherine Philips, the Matchless Orinda. This included both Pompey and a nearly completed translation of Corneille’s Horace: Philips died before she had chance to finish it. In his preface, Philips’ friend Sir Charles Cotterell is appreciative but patronizing, saying that some of her poems:

“… would be no disgrace to the name of any Man that amongst us is most esteemed for his excellency in this kind, and there are none that may not pass with favour, when it is remembered that they fell hastily from the pen but of a woman. We might well have called her the English Sappho, she of all the female Poets of former Ages, being for her Verses and her Virtues both, the most highly to be valued.”

. . . . . . . . .

More about Katherine Philips

The Matchless Orinda on JSTOR Katherine Philips – British Library. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Matchless Orinda — Early English Poet & Playwright Katherine Philips appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Diana: A Strange Autobiography by Diana Frederics (1939)

Frances V. Rummell, an American writer and educator, published Diana: A Strange Autobiography (1939) under the pseudonym Diana Frederics. More of an autobiographical novel than an actual memoir, nonetheless draws upon the author’s life. The story details the title heroine’s discovery of her lesbian sexuality.

Positive portrayal of lesbians was considered shocking when the book was published. It’s now considered groundbreaking as one of the first works of gay fiction to have a happy outcome.

Published squarely between The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall (1928) and the lesbian pulp novels that emerged in the early 1950s, Diana is a worthy, yet often overlooked addition to the genre. This analysis and appreciation is excerpted from Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission:

“This is the unusual and compelling story of Diana, a tantalizingly beautiful woman who sought love in the strange by-paths of Lesbos. Fearless and outspoken, it dares to reveal that hidden world where perfumed caresses and half-whispered endearments constitute the forbidden fruits in a Garden of Eden where men are never accepted.”

This was the blurb for the 1952 paperback edition – republished right at the beginning of the lesbian pulp fiction movement – of Diana: A Strange Autobiography by the pseudonymous Diana Frederics, who kept her identity secret until it was finally revealed on a PBS documentary in 2010.

Long after her death, it was revealed that the author was Frances V Rummell (1907-1969), a teacher of French at Stevens College, a women-only college in Columbia, Missouri (the second-oldest college in America to have remained all-female).

Diana was originally published by Dial Press in 1939 and republished in hardback by City Press of New York in 1948. Both editions contained an introduction by the sexologist Victor Robinson, explaining that lesbianism was:

“… Ancient in the days of Sappho of Lesbos. Yet such is our immunity to information, that when Havelock Ellis collected his various studies on Sexual Inversion (1897), he states that before his first cases were published, not a single British case, unconnected with the asylum or the prison, had ever been recorded.”

Robinson added: “I welcome any book which adds to the understanding of the lesbians in our midst. Among these books, I definitely place the present autobiography.” Unlike Dusty Answer and The Well of Loneliness, both the introduction and the main text use the word “lesbian,” quite astonishing for 1939; it would not be used in a published novel again for years.

Although it purports to be an autobiography and may well reflect the author’s own experiences, Diana is structured much like a novel. It is similar in many ways to Dusty Answer and to Vin Packer’s Spring Fire. Here also the heroine is unsure of her sexuality until she falls in love with a girl at college, but unlike Judith in Dusty Answer she does not subsequently try to revert to heterosexuality and end up alone and miserable.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

Girls in Bloom on Amazon UK*

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . . . .

Diana has always been a tomboy: “I had always played with boys instead of girls, and growing older made no difference; I still did. Girls frankly bored me … I was scarcely conscious of being a girl. The boys accepted me as one of them as tacitly as I assumed that position.” No one, not even her parents, considers her to be a problem, she is just a regular tomboy to them.

“My mother and father had always taken my antics as they came, hopeful that time and age would season my tomboyish nature. Of course, they were indulgent with me; I was their only girl. I was a healthy young animal, full of energy and devilry, and tomboys were common enough. They mature into just as feminine young women as did the little girls who preferred dolls to BB guns.”

Like Carson McCullers’ tomboy Frankie Addams, Diana is very musical; her mother is not sure that her daughter should be attending music theory classes with boys but the music teacher convinces her to let Diana go; he says rightly that age and gender have nothing to do with musical ability, though by the time she is in her senior year her teacher is telling her that her very ‘clean touch’ on the keyboard is “masculine.”

A brief flirtation with a boy

In these classes, as well at home, Diana, like many tomboys, is surrounded by boys – including her brothers and young men from the college who rent rooms in her house – from the age of twelve to sixteen, when she goes to college. All these boys are of course protective of her and she is of course not the slightest bit seductive or provocative but one day, when she is “a hopelessly naïve child of thirteen,” it becomes obvious to her that she is not just one of the boys.

“One boy, a newcomer to our home, called me into his room one rainy Sunday afternoon to admire some snapshots. I hesitated a moment, since I never entered the guest rooms, but, reluctant to appear rude, I went. Ignorant as I was, his intentions were too abrupt to be misunderstood.

I recall only my fury; in spite of my years, it was enough to upset a blundering collegian. Like many people who manage to keep their heads in a tight predicament, I suffered repercussions. For weeks afterward I felt the full impact of sordidness. Despite the sudden exit of the collegian from our home, with no more explanation to my mother on my part than on his, this scene remained indelible.

It is almost incredible to me now to recall the extent of the effects of this assault on my innocence. I was made too abruptly aware that life amounted to something more than front yard games and school and camp.

My would-be seducer had said something to me which made me think more than I had ever honestly thought in my young life. I even got out my dictionary to find out what he’d meant by saying I was ‘seductive-looking.’ What a disturbing thought to one who until that very moment was completely unconscious of her body, despite a maturing physique.

I spent days brooding over the fact that I had been born a girl. I didn’t want to grow up. I didn’t want to be ‘seductive -looking.’ I hated the expression, I hated the vague meaning. Oh, the horror of becoming an adult!

Shocked into the realization that I was growing up in spite of myself, I turned suddenly into an antisocial, introspective, melancholy bookworm. Life took on the proportions of a pitiless hoax. In the diary I kept at this time is entered, in the handwriting of a fourteen-year-old, such a penetrating observation as this: ‘It is cruel of parents to read fairy tales to children. The transition from the delicate fantasy of the fairy tale to real life is painful. Life bumps into children as they grow up.’”

This coming-of-age moment turns her against boys, “for no reason except that they were growing up too. And some of them wrote notes to me in school that seemed silly and embarrassed me.” Diana retreats into her reading and music, though she does attend the school prom with the older boy Gil, whom she allows to kiss her, but that is far as it goes.

Enter Ruth

Gil is swept aside when Ruth enters the school; Diana is smitten with her. ‘She was too thin and her mouth was too large, but she had lovely titian hair, worn in braids around her head, solemn blue eyes, and such a sweet smile that I wondered if anyone could possibly be as angelic as she seemed.’ Ruth and Diana, among others, are invited to a Christmas house party. “I knew I would contrive in every way possible to share a room with her.” She manages it.

“That night when we went to bed alone, tired and happy with the day, Ruth’s thoughtless intimacy and good-night embrace almost took my breath away. I had been surprised to feel curious sensations of longing the few times I had ever touched her, but I could never have imagined the exquisite thrill of feeling her body close to mine. Now I was amazed.

Then, before I knew it, I realized I wanted to caress her. Then I became terrified by a nameless something that froze my impulse. The pain of resisting was torture, but the touch of her hand holding mine against her side was so infinitely sweet that I tensed for fear my slightest movement would make her turn away from me. Long hours I lay awake after she had gone to sleep, scarcely daring to breathe for fear she might move, not daring to hope that I might kiss her lips without startling her …

I never spoke to Ruth of my feelings. Fear restrained me. I had enough sense of proportion to realize that what I felt was extraordinary. I was afraid she would not understand my affection. I did not understand myself.”

Grace: A lost opportunity

Diane later goes to college to study French, and meets Grace, with whom we are expecting her to have an affair; “I had been rather awed by her cool charm and by her oft-repeated refusals to go out on dates with the boys who invited her.”

They read Baudelaire and Verlaine together – very heavy, decadent stuff for two college girls at that time; Baudelaire, of course, wrote The Flowers of Evil, and Verlaine, one of his followers, was the lover of Rimbaud. “Suddenly, inspired no doubt by Verlaine, she began to talk about homosexuality. Obviously, she was trying to sound out my reactions to the subject, and my self-consciously evasive replies made me blush with embarrassment.”

Diana is unprepared for this line of questioning; “As it was, my confusion was my defense. Extremely sensitive, Grace interpreted my awkwardness for reluctance, and, humiliated for having ‘misunderstood,’ she left.”

Considering marriage … to a man?

Before things with Grace have a chance to go anywhere, Diane meets Carl, an older man, who falls in love with her and asks her to marry him. “My first feeling was one of dismay.” She is flattered but confused, thinking she must accept, but “I could not force myself suddenly to end the happiest friendship I had ever known” – with, presumably, Grace.

Nevertheless, when he gives her his fraternity pin and kisses her she feels a “pale emotion – the first I had ever felt for a man.” But even this pale shadow of a feeling is enough to make her feel that perhaps she is after all normal. “When I left him I ran to my room giddily happy. Oh, dear God, it had happened. It was going to be all right.”

But then, the thought of having to have physical sex with Carl enters her head. “I have every possible reason but one to be convinced that Carl and I would be happily married – I did not know whether I loved him physically.” She has heard women talk and has read books on sexology which led her to believe that, even if she does not like having sex with him at first, she will come around. Diane tells Carl that she will live with him but not marry him. At first, all goes well.

“Some indescribable emotion pulled at me as I looked at him, and all I could think of was something I had read – of a woman happy that her lover need no longer sigh with unrest; she would give him ecstasy. I understood that now. Suddenly I gloried in an unexpected sense of possession. It seemed to me that I had never been so happy. There was no need to question. My place was with Carl.

It did not matter that first physical intimacy had been disappointing. I could not expect a miracle of chemistry to follow the mere act of defloration; I understood that it frequently took some little time for a woman to become adjusted, for her to learn rhythm, to grow together. At least I had managed the first pain. Now I could look forward.”

For some time, Diana feels as though she is becoming “normal,” though never in their time together had “physical intimacy meant anything to me but the giving of pleasure to Carl… the very words ‘desire,’ ‘passion,’ ‘ecstasy,’ were but fugitive words to me, symbols of unscented experience.”

Looking inwardDiana has become “a slave to dissimulation,” as she knows many married women are, whether or not they have lesbian tendencies.

When she goes to a women’s college in Massachusetts to take a Masters in German, the “number of lesbians I met there impressed me not only because my consciousness of them was sharpened, but because they were unmistakably frequent.” But even in this environment, she decides to hide her feelings: she learns “the grace of a lie and a new admiration for hypocrisy;” she vows that “no one would ever have such an easy clue to my own lesbianism.”

This self-imposed isolation of course makes her lonely. “I was approaching a future whose peculiar loneliness I could already understand.” What Diana cannot understand is what it would be like to indulge her preferences. “What was lesbian love like? Its intellectual pleasures were easy enough to guess at, but what physical pleasure did women achieve of one another… Vaguely I wondered how I would learn to know all the things I needed to know.”

Then she meets Elise and has her first physical experience with another woman. But Elise is already spoken for.

“I was released of all feeling, submerged in a glorious lethargy, timeless and in a dream. I could make no effort to open my eyes. I hadn’t expected it to be something like dying… I told her a little wildly that she had been my first; that she could not leave me, could not. Very gently she told me she had known, and that she had known all the while that Katherine was coming so soon. Now I knew why she had left me. For Elise that had been a gesture of fidelity – lesbian fidelity. I had made no difference.”

Diana reacts to these twin experiences – her first physical experience with a woman and her first emotional experience of betrayal – by leaving that night for Paris, wiser if not much older. “I realized that the incident with Elise had, for all its humiliation, given me a kind of assurance that I had needed desperately. Before Elise I had not known whether women could have sexual gratification of one another … Elise had completed my knowledge.”

Coming of age physically and emotionally

Diana has come of age physically and emotionally, and her next relationship, with Jane, is much more straightforward. “We wanted a normal domestic life and we wanted our happiness together. We asked nothing of anyone. We hurt no one. We were mature, free, and perfectly sure of ourselves.” Diana now realizes that to accept her “lesbianism and my circumstances without fear, without distaste, would be my ultimate freedom.”

Unfortunately, even though she is free within herself and she and Jane are free within their relationship, the outside world intrudes. After her first term teaching, her relationship with Jane is remarked upon and she is offered the choice between moving by herself into the single women’s accommodation or leaving the college. She chooses to leave. But Jane is not her final lover; she meets Leslie and leaves Jane – physically, though not emotionally, until the end of the book, when Leslie finally replaces Jane.

“I knew that Jane had been swept into time, into the forgotten. Even the thought of her seemed obscure. Leslie and I extricated ourselves; no longer need there be anything at all to remind us of Jane. I could feel how it had happened, but I could not have foreseen it. Slowly, half-prayerful, half-exultant, it had come to me – the testimony of her patience was enough – I could turn toward Leslie and know that her loyalty was no less than my own.”

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Diana: A Strange Autobiography by Diana Frederics (1939) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 13, 2021

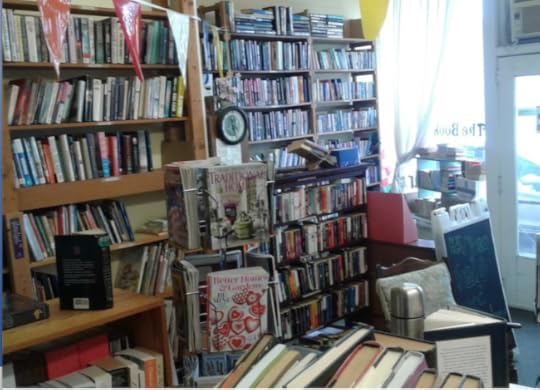

The Only Bookstore in the County: The Book End, Blackstone, Virginia

This musing on The Book End, a used book shop in Blackstone Virginia, highlights the importance of a local bookstore, even a modest one, to a town’s cultural life. Contributed by Tyler Scott:

Two years ago my husband and I realized we needed a change. We had grown tired of city life after raising our children in Richmond, Virginia, our hometown, so one Sunday we drove southside to go antiquing in Blackstone, where my mother-in-law spent part of her childhood.

We met a distant cousin for the first time, and explained we were looking for a small place to move not too far away from family and friends; she took us around to look at real estate, and a week later we put a contract on a Queen Anne Revival built in 1896. By fall, we had put our house on the market and rented a residence while we renovated the Victorian. I also had to explain to several people we were not getting a divorce.

Adjusting to small-town lifeGranville and I moved from a city with a metro area population of 1,105,000 to a town of 3,400 plus a National Guard base. The change took some getting used to, yet we acclimated quickly. Our adventure had begun.

At a certain time of day, under a smoke-blue sky, if you drive down Blackstone’s Main Street, it looks like the 1950s – other than the traffic. The welcoming stark white spire of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church; the monotonous brick façade of the Wedgewood Motor Inn; and turn-of-the-century homes, some showplaces, some mummified and depressing.

This is a town where most people drive pickup trucks and we all wave to each other, strangers included. A contractor told me Blackstone was so small they would all know what I was going to do before I did, and he was right. I learned it may only take fifteen minutes to do my errands whereas I needed an extra half hour so I could talk to everyone I met. This is just what we do.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Book End in Blackstone, VA

. . . . . . . . . . .

One of the best parts about Blackstone is our bookstore, The Book End (gently used books), on Maple Street, next door to the Sanitary Barber Shop and down the way from our newspaper the Courier Record. My husband and I frequent the store more than Amazon or the library and I am sure he is one of their best customers since he buys at least eight books a month.

The prices haven’t changed since they opened in 2007; unless you buy a first edition online, the in-store prices range from 25 cents to 4 dollars. The store, 15 by 15 feet, is so small that I must move the coffeepot if I want to look at the biographies.

Finding treasures to read

Pat Conroy called a bookstore “a wonderland” and a “portal to the world” and I agree with him one hundred percent. One of my favorite pastimes is to browse. The moment I walk through the front door, I can feel life’s stress lift from my shoulders.

Where books there is fellowship so I can study the shelves to my heart’s content and talk to anyone nearby. I rarely go with a list of hope-to-finds and all those inexpensive books make me feel heady; stories of love and triumph, heartbreak and devastation, the glories of victory and the results of despair, not to mention just good old-fashioned storytelling at its best. This is a trip to a foreign land and you never know what you will stumble upon.

. . . . . . . . . . .

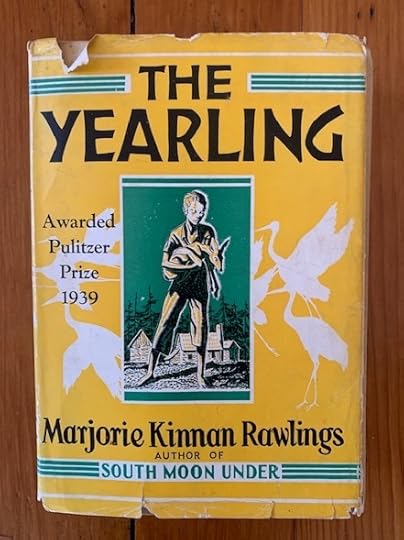

A well-loved copy of The Yearling found at The Book End

. . . . . . . . . . .

The last time I visited The Book End, I bought To Begin Again, one of M.F.K. Fisher’s early memoirs; Blue Nights by Joan Didion (which I will return because I can’t bring myself to read about the tragedy of losing a daughter); and a 1939 copy of The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings with illustrations— Thoreauian-toned prints by Edward Shenton. The inside cover of the Rawlings is inscribed as follows: “To Courtney – on her 11th Birthday- written over 60 years ago and enjoyed by millions of young people just like you— With love, Grandma”

And what have the volunteers (who are paid a book each day they work) found in donated books? “Bookmarks, letters, airline tickets, and bills,” remembers volunteer Arrol Lund, Secretary of the Friends, and reported to know the inventory thoroughly. Granville had the biggest find of all: a one hundred dollar bill that was being used as a bookmark. He promptly donated this to the library.

How it all began

Volunteers opened the bookstore to serve the Louis Spencer Epes Memorial Library and encourage school-aged children to read. At the time, the library needed to expand and wanted to sell books they no longer needed; they had no money or space, so a group of volunteers organized Friends of the Library and decided to open a used bookstore.

A benevolent businessman, Bobby Daniels, offered the building for free and the ladies had a contest where people submitted names like The Bookshelf, The Book Depot, Unwinders Books, The Dusty Page, and the Book End. Hence, a paradise was born for readers.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Mission and community supportAccording to the Friends of the Library pamphlet, the mission is to generate community support; volunteer at the library when needed; operate and maintain The Book End; conduct book sales and special events like discussions and storytellers; buy necessary equipment and books the library may need; cultivate donors; and host special events and book giveaways.

Projects have been extensive – $10,000 was given to the library a few years ago for carpet and computers and last year the Friends split the cost of online services like hoopla and OverDrive with Crewe, a neighboring town. Every year the Friends host several children’s book giveaways including Halloween and the Grand Illumination event at Christmas.

Customers like the once-a-month Purple Bag Sale: a bag of books for $5. Moreover, on a sweet note, every third grader in Blackstone has received an inscribed dictionary from The Friends of the Library. (If I had been one of those students, I would still have my dictionary.)

A loyal following

The Book End can count on customers like my husband. His study is a sea of murder mysteries with titles like Bad Business, The Skull Beneath the Skin, and Wicked Prey. (For a mild-mannered man he certainly does have violent tastes in reading.) I asked him once what made The Book End unique and he says it’s local and easy to drop in on: “I can go through the entire store in ten minutes and the stock turns over quickly.”

Granville considers this a way of giving back, calling it “penny philanthropy. I can buy a book for a dollar,” he explains as he puts down the Robert Parker mystery he is reading, and “the dollar goes over to the library and then I will take it back and they can sell it for another dollar. Every time I go, I donate twice.”

The Book End sells mostly westerns, science fiction, and romance. The hours are generous, though if you call and leave a message, they’ll open just for you. They put their best books on the website Alibris, where they list nearly one thousand books; the rest of the inventory, about 4,500 books, comes from not only donations but also library purges.

Dedicated volunteers

Any non-profit reflects the dedication of its volunteers and The Book End is run by a core of women of a certain hallowed age. According to Lauren Watkins, Treasurer of the Friends and a neighbor, “running The Book End would be impossible without them.”

Tilly Conley is a longtime volunteer and current Vice President of the Friends who helps with pricing and does most of the computer work. A former English, theater arts, and photojournalism high school teacher, she is loquacious on the phone and interviews herself for the most part. “I like to read so much I’ll read the back of a cereal box,” she chuckles. Books have been a part of her life growing up in Blackstone (she lives in her childhood home) and she reminisces about the town librarian Mrs. Franny Jones who would take a book away from you if she thought you were too young for it.

What does the future hold for The Book End? The building has been sold to Molly Black, owner of the Sanitary Barbershop, and the good news is the store will remain as tenants and the rent will not be increased from $200 a month.

The Friends are still discussing financial details with Blackstone and Nottoway County and they plan on holding more fundraisers. The shop is also looking for volunteers because many of them have cut back on responsibilities like manning booths, baking to raise money, and carrying hundreds of heavy books. Or sadly, they have died.

Support local bookstores

The day draws to a close and Main Street is starting to quiet down. The horizon has a lilac tint – spring is on the way – and I see a few people walking towards the Farmer’s Café for an early supper. I turn left on Maple Street and park in front of The Book End to gaze at the books beckoning from the windows. Who would have thought such a modest place could have an impact on so many? In life, I have learned, sometimes it is the small endeavors that are inspirational.

Please support your local used bookstores and consider a donation to The Book End. Make checks payable to Friends of the Library, Blackstone. Mail to The Book End, 102 Maple Street, Blackstone, Virginia 23824.

Contributed by Tyler Scott. Tyler lives in Blackstone, Virginia with her husband and Norfolk Terrier. Her essays and articles have appeared in numerous magazines and newspapers and her novel The Excellent Advice of a Few Famous Painters* is available on Amazon.

*This is an Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Only Bookstore in the County: The Book End, Blackstone, Virginia appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 10, 2021

10 Poems by Elinor Wylie

Elinor Wylie (1885 – 1928) was a popular American poet and novelist in the 1920s and 1930s. Also widely known for her tumultuous personal life, many of her works offered insight into the difficulties of marriage and the impossible expectations that come with womanhood.

Though Wylie is no longer widely read, she was a celebrated author in her lifetime, with a cult following in her pinnacle years. She was known for her passionate writing, fueled by ethereal descriptors, historical references, and feminist undertones.

Born Elinor Hoyt in Somerville, New Jersey; she was raised in a distinguished family. Though she never pursued higher education, Elinor had a natural talent as a writer. She first began to write seriously and considered publishing during her time in England. This was followed by a scandalous elopement with Horace Wylie, a much older man who had been practically stalking her for years.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Elinor Wylie

. . . . . . . . . .

Wylie anonymously self-published her first collection of poems, Incidental Numbers, in 1912. Soon after, she moved back to the states and began pursuing a serious writing career. Nets to Catch the Wind, was her first traditionally published poetry collection, appeared in 1921, it is heavily anthologized to this day.

During her short span of eight years as a writer, Wylie published four volumes of poetry and four novels, all garnering praise. She died of a stroke at age forty-three, her untimely death coming at the height of her career.

American poet Louis Untermeyer once described Wylie’s writing as “a passion frozen at its source.” Her literary force transcends the marital scandals that once marked her reputation. As subtle as she was bold, her ability to blend contemporary themes within a traditionalist writing style contributed to the developing aesthetic of modernism.

Here are the poems in this listing:

Wild Peaches A Crowded Trolley CarVelvet ShoesEpitaphCold Blooded CreaturesWinter SleepSea LullabyValentineFull MoonLittle Elegy. . . . . . . . . .

Wild Peaches1

When the world turns completely upside down

You say we’ll emigrate to the Eastern Shore

Aboard a river-boat from Baltimore;

We’ll live among wild peach trees, miles from town,

You’ll wear a coonskin cap, and I a gown

Homespun, dyed butternut’s dark gold colour.

Lost, like your lotus-eating ancestor,

We’ll swim in milk and honey till we drown.

The winter will be short, the summer long,

The autumn amber-hued, sunny and hot,

Tasting of cider and of scuppernong;

All seasons sweet, but autumn best of all.

The squirrels in their silver fur will fall

Like falling leaves, like fruit, before your shot.

2

The autumn frosts will lie upon the grass

Like bloom on grapes of purple-brown and gold.

The misted early mornings will be cold;

The little puddles will be roofed with glass.

The sun, which burns from copper into brass,

Melts these at noon, and makes the boys unfold

Their knitted mufflers; full as they can hold

Fat pockets dribble chestnuts as they pass.

Peaches grow wild, and pigs can live in clover;

A barrel of salted herrings lasts a year;

The spring begins before the winter’s over.

By February you may find the skins

Of garter snakes and water moccasins

Dwindled and harsh, dead-white and cloudy-clear.

3

When April pours the colours of a shell

Upon the hills, when every little creek

Is shot with silver from the Chesapeake

In shoals new-minted by the ocean swell,

When strawberries go begging, and the sleek

Blue plums lie open to the blackbird’s beak,

We shall live well—we shall live very well.

The months between the cherries and the peaches

Are brimming cornucopias which spill

Fruits red and purple, sombre-bloomed and black;

Then, down rich fields and frosty river beaches

We’ll trample bright persimmons, while you kill

Bronze partridge, speckled quail, and canvasback.

4

Down to the Puritan marrow of my bones

There’s something in this richness that I hate.

I love the look, austere, immaculate,

Of landscapes drawn in pearly monotones.

There’s something in my very blood that owns

Bare hills, cold silver on a sky of slate,

A thread of water, churned to milky spate

Streaming through slanted pastures fenced with stones.

I love those skies, thin blue or snowy gray,

Those fields sparse-planted, rendering meagre sheaves;

That spring, briefer than apple-blossom’s breath,

Summer, so much too beautiful to stay,

Swift autumn, like a bonfire of leaves,

And sleepy winter, like the sleep of death.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Crowded Trolley CarThe rain’s cold grains are silver-gray

Sharp as golden sands,

A bell is clanging, people sway

Hanging by their hands.

Supple hands, or gnarled and stiff,

Snatch and catch and grope;

That face is yellow-pale, as if

The fellow swung from rope.

Dull like pebbles, sharp like knives,

Glances strike and glare,

Fingers tangle, Bluebeard’s wives

Dangle by the hair.

Orchard of the strangest fruits

Hanging from the skies;

Brothers, yet insensate brutes

Who fear each others’ eyes.

One man stands as free men stand

As if his soul might be

Brave, unbroken; see his hand

Nailed to an oaken tree.

. . . . . . . . . .

Velvet ShoesLet us walk in the white snow

In a soundless space;

With footsteps quiet and slow,

At a tranquil pace,

Under veils of white lace.

I shall go shod in silk,

And you in wool,

White as white cow’s milk,

More beautiful

Than the breast of a gull.

We shall walk through the still town

In a windless peace;

We shall step upon white down,

Upon silver fleece,

Upon softer than these.

We shall walk in velvet shoes:

Wherever we go

Silence will fall like dews

On white silence below.

We shall walk in the snow.

. . . . . . . . . .

EpitaphFor this she starred her eyes with salt

And scooped her temples thin,

Until her face shone pure of fault

From the forehead to the chin.

In coldest crucibles of pain

Her shrinking flesh was fired

And smoothed into a finer grain

To make it more desired.

Pain left her lips more clear than glass;

It colored and cooled her hand.

She lay a field of scented grass

Yielded as pasture land.

For this her loveliness was curved

And carved as silver is:

For this she was brave: but she deserved

A better grave than this.

. . . . . . . . . .

Cold Blooded CreaturesMan, the egregious egoist,

(In mystery the twig is bent,)

Imagines, by some mental twist,

That he alone is sentient

Of the intolerable load

Which on all living creatures lies,

Nor stoops to pity in the toad

The speechless sorrow of its eyes.

He asks no questions of the snake,

Nor plumbs the phosphorescent gloom

Where lidless fishes, broad awake,

Swim staring at a night-mare doom.

. . . . . . . . . .

Winter SleepWhen against earth a wooden heel

Clicks as loud as stone on steel,

When stone turns flour instead of flakes,

And frost bakes clay as fire bakes,

When the hard-bitten fields at last

Crack like iron flawed in the cast,

When the world is wicked and cross and old,

I long to be quit of the cruel cold.

Little birds like bubbles of glass

Fly to other Americas,

Birds as bright as sparkles of wine

Fly in the nite to the Argentine,

Birds of azure and flame-birds go

To the tropical Gulf of Mexico:

They chase the sun, they follow the heat,

It is sweet in their bones, O sweet, sweet, sweet!

It’s not with them that I’d love to be,

But under the roots of the balsam tree.

Just as the spiniest chestnut-burr

Is lined within with the finest fur,

So the stoney-walled, snow-roofed house

Of every squirrel and mole and mouse

Is lined with thistledown, sea-gull’s feather,

Velvet mullein-leaf, heaped together

With balsam and juniper, dry and curled,

Sweeter than anything else in the world.

O what a warm and darksome nest

Where the wildest things are hidden to rest!

It’s there that I’d love to lie and sleep,

Soft, soft, soft, and deep, deep, deep!

. . . . . . . . . .

Sea LullabyThe old moon is tarnished

With smoke of the flood,

The dead leaves are varnished

With colour like blood,

A treacherous smiler

With teeth white as milk,

A savage beguiler

In sheathings of silk,

The sea creeps to pillage,

She leaps on her prey;

A child of the village

Was murdered today.

She came up to meet him

In a smooth golden cloak,

She choked him and beat him

To death, for a joke.

Her bright locks were tangled,

She shouted for joy,

With one hand she strangled

A strong little boy.

Now in silence she lingers

Beside him all night

To wash her long fingers

In silvery light.

. . . . . . . . . .

ValentineToo high, too high to pluck

My heart shall swing.

A fruit no bee shall suck,

No wasp shall sting.

If on some night of cold

It falls to ground

In apple-leaves of gold

I’ll wrap it round.

And I shall seal it up

With spice and salt,

In a carven silver cup,

In a deep vault.

Before my eyes are blind

And my lips mute,

I must eat core and rind

Of that same fruit.

Before my heart is dust

At the end of all,

Eat it I must, I must

Were it bitter gall.

But I shall keep it sweet

By some strange art;

Wild honey I shall eat

When I eat my heart.

O honey cool and chaste

As clover’s breath!

Sweet Heaven I shall taste

Before my death.

. . . . . . . . . .

Full MoonMy bands of silk and miniver

Momently grew heavier;

The black gauze was beggarly thin;

The ermine muffled mouth and chin;

I could not suck the moonlight in.

Harlequin in lozenges

Of love and hate, I walked in these

Striped and ragged rigmaroles;

Along the pavement my footsoles

Trod warily on living coals.

Shouldering the thoughts I loathed,

In their corrupt disguises clothed,

Morality I could not tear

From my ribs, to leave them bare

Ivory in silver air.

There I walked, and there I raged;

The spiritual savage caged

Within my skeleton, raged afresh

To feel, behind a carnal mesh,

The clean bones crying in the flesh.

. . . . . . . . . .

Little ElegyWithouten you

No rose can grow;

No leaf be green

If never seen

Your sweetest face;

No bird have grace

Or power to sing;

Or anything

Be kind, or fair,

And you nowhere.

. . . . . . . . . .

More About Elinor Wylie Wikipedia The Poetry Foundation Owlcation BritannicaContributed by Jess Mendes, a 2021 graduate of SUNY-New Paltz with a major in Digital Media Management, and a minor in Creative Writing.

The post 10 Poems by Elinor Wylie appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 8, 2021

Olympe de Gouges: An Introduction to Her Life and Work

The French playwright, pamphleteer, women’s rights advocate, abolitionist, and early feminist Olympe de Gouges (1748 – 1793), author of over thirty plays, was savagely criticized by the male French literary establishment for the liberalism of her dramas. She was unrepentant in her response, an open letter To the French Littérateurs.

“What crimes have I committed to merit such infamous treatment: how have I transgressed; how have I wronged anyone in any way? What? A dramatic work, a text full of humanity, sensibility and justice has provoked people unknown to me? Has incited the blackest calumny, has encouraged my enemies, renewed their vigour.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“MY DEAREST SISTERS, it is to you that I dedicate all the failings that teem within my works. May I flatter myself that you will have the generosity or the prudence to defend them, or should I fear from you more rigour, more severity, than from the most austere of our Savants, who wish to invade everything and only allow us the right to please. Men insist that we are fit only to manage a household: women who are perceptive and aspire to take up Literature are Beings that society cannot tolerate.” (Preface Pour les Dames)

De Gouges wrote the seminal pre-feminist text Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen during the French Revolution in 1791 – the same year as Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man and the year before Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. It was written in response to the French revolutionary document Declaration of the Rights of Man of 1789.

This document begins: ‘Man, are you capable of being fair? A woman is asking: at least you will allow her that right. Tell me? What gave you the sovereign right to oppress my sex?’

“Woman, wake up! The toxin of reason is being heard throughout the whole universe; discover your rights. The powerful empire of nature is no longer surrounded by prejudice, fanaticism, superstition, and lies. The flame of truth has dispersed all the clouds of folly and usurpation. Enslaved man has multiplied his strength and needs recourse to yours to break his chains. Having become free, he has become unjust to his companion. Oh, women, women! When will you cease to be blind? What advantage have you received from the Revolution?”

In language similar to the American Declaration of Independence of 1776, de Gouge’s Declaration sets out seventeen articles that form possibly the first coherent and comprehensive statement of the equality of the sexes.

The sex that is as superior in beauty as it is in courage during the sufferings of maternity recognizes and declares in the presence and under the auspices of the Supreme Being, the following Rights of Woman and of Female Citizens.

Article 1. Woman is born free and lives equal to man in her rights. Social distinctions can be based only on the common utility.

Article 2. The purpose of any political association is the conservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of woman and man; these rights are liberty, property, security, and especially resistance to oppression.

Women were subject to the same laws and punishments as men but did not enjoy the same rights, said de Gouges. “Women have the right to mount the scaffold, they must also have the right to mount the speaker’s rostrum.”

This was very prescient of de Gouges: she was accused of treason and executed by guillotine for writing the pamphlet. Many women have been criticized for writing and publishing their views but few have been executed for it.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

On November 3, 1793, Olympe de Gouges was sentenced to death by the French Revolutionary Tribunal for seditious behavior and attempting to reinstate the monarchy. She was to die by the guillotine. Her last hours were described by an anonymous Parisian:

“Yesterday, at seven o’clock in the evening, a most extraordinary person called Olympe de Gouges who held the imposing title of woman of letters, was taken to the scaffold, while all of Paris, while admiring her beauty, knew that she didn’t even know her alphabet …

She approached the scaffold with a calm and serene expression on her face, and forced the guillotine’s furies, which had driven her to this place of torture, to admit that such courage and beauty had never been seen before …

That woman had thrown herself in the Revolution, body and soul. But having quickly perceived how atrocious the system adopted by the Jacobins was, she chose to retrace her steps. She attempted to unmask the villains through the literary productions which she had printed and put up. They never forgave her, and she paid for her carelessness with her head.”

Quotes from A Declaration of the Rights of Women (1791)“Woman is born free and lives equal to man in her rights. Social distinctions can be based only on the common utility.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Marriage is a tomb of trust and love. The married woman can with impunity give bastards to her husband, and also give them the wealth which oes not belong to them. The woman who is unmarried has only one feeble right; ancient and inhuman laws refuse to her for her children the right to the name and the wealth of their father; no new laws have been made in this matter. If it is considered a paradox and an impossibility on my part to try to give my sex an honorable and just consistency, I leave it to men to attain glory for dealing with this matter; but while we wait, the way can be prepared through national education, the restoration of morals, and conjugal conventions.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Man, are you capable of being just? It is a woman who poses the question, you will not deprive her of that right at least. Tell me, what gives you sovereign over empire to oppress my sex? Your strength? Your talents?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Man alone has raised his exceptional circumstances to a principle. Bizarre, blind, bloated with science and degenerated — in a century of enlightenment and wisdom – into the crassest ignorance, he wants to command as a despot a sex which is in full possession of its intellectual faculties; he pretends to enjoy the Revolution and to claim his rights to equality in order to say nothing more about it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Male and female citizens, being equal in the eyes of the law, must be equally admitted to all honors, positions, and public employment according to their capacity and without other distinctions besides those of their virtues and talents.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The laws must be the expression of the general will; all female and male citizens must contribute either personally or through their representatives to its formation; it must be the same for all: male and female citizens, being equal in the eyes of the law, must be equally admitted to all honors, positions, and public employment according to their capacity and without other distinctions besides those of their virtues and talents.”

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

The post Olympe de Gouges: An Introduction to Her Life and Work appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 7, 2021

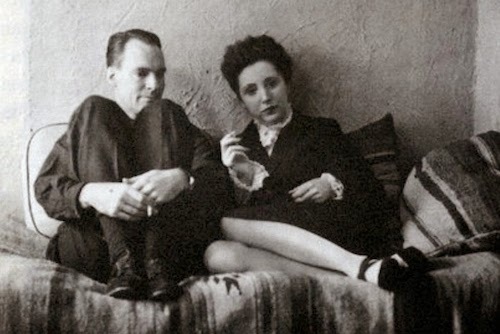

When Anaïs Met Henry: Nin’s Tumultuous Affair with Henry and June Miller

In late 1931, the author and diarist Anaïs Nin met Henry Miller and his wife, June. She first fell in love with Henry’s writing, and then with the man himself before being seduced by his wife, June. This excerpt from Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde by Francis Booth recounts what would be a fateful, formative affair:

Henry Miller was the author of banned, erotic novels like Tropic of Cancer and Black Spring, originally published by Jack Kahane’s Obelisk Press in 1934 and 1936 respectively. Henry was married at the time he met Anaïs Nin, to June Anderson, the second of his five wives (Nin wasn’t, and would not be, one of the five). Nin was married at the time also, to Hugo Parker Guiler (sometimes known as Ian Hugo).

Even before she met Henry, Anaïs and Hugo already had a stormy relationship after seven years of marriage. “We have never been as happy or as miserable. Our quarrels are portentous, tremendous, violent. We are both wrathful to the point of madness: we desire death.” Anaïs discussed her marriage with her lover and cousin Eduardo, and notes his advice in her diary for October 1931.

“We talked for six hours. He reached the conclusion I have come to also: that I needed an older mind, a father, a man stronger than me, a lover who will lead me in love, because all the rest is too much a self-created thing. The impetus to grow and live intensely is so powerful in me I cannot resist it. I will work, I will love my husband, but I will fulfill myself.”

. . . . . . . . .

Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin

. . . . . . . . .

So when Anaïs met Henry she was ready for him and he was ready for anything. She describes their first meeting in her journal for December 1931.

“I’ve met Henry Miller. He came to lunch with Richard Osborn, a lawyer I had to consult on the contract for my DH Lawrence book.

When he first stepped out of the car and walked towards the door where I stood waiting, I saw a man I liked. In his writing he is flamboyant, virile, animal, magnificent. He is a man whom life makes drunk, I thought. He is like me. . .

We talked for hours. Henry said the truest and deepest things, and he has a way of saying “hmmm” while trailing off on his own introspective journey. . .

A few days later I met Henry. I was waiting to meet him, as if that would solve something, and it did. When I saw him, I thought, here is a man I could love. And I was not afraid.”

Hugo knew all about her relationship with Henry and feared he would lose Anaïs to him. ‘Hugo admires him. At the same time he worries. He says justly, “you fall in love with people’s minds. I’m going to lose you to Henry.”‘

He did lose her, even though they stayed married. But he lost her to June at least as much as to Henry. Henry had met the dark, exotic June Mansfield, fictionalized in his novels as Mona or Mara (and played by Uma Thurman in the 1992 film Henry and June) in Times Square in 1923.

“It must have been a Thursday night when I met her for the first time at the dance hall,” he wrote in Sexus. She was 21, he was 31 and married. June was born Juliet Smerth in 1902 in Bukovina, a region now divided between Romania and Ukraine, and came to America in 1907.

. . . . . . . . .

June and Henry Miller

June and Henry Miller

. . . . . . . . . . .

It was June who first took Henry to Paris, having saved the money for the trip; and it was June who encouraged him to write full time and supported him by driving taxis; she also gave him the money she got from other men, though she was at least as interested in women. In 1926 June moved a young poet – the woman she called Jean Kronski, but who was probably really named Martha Andrews – in with them. Miller hated Jean, whom he called Thelma in his short book on Rimbaud, The Time of the Assassins.

Though Rimbaud was the all-engrossing topic of conversation between Thelma and my wife, I made no effort to know him. In fact, I fought like the very devil to put him out of my mind; it seemed to me then that he was the evil genius who had unwittingly inspired all my trouble and misery.

I saw that Thelma, whom I despised, had identified herself with him, was imitating him as best she could, not only in her behaviour but in the kind of verse she wrote … In that state of despair and sterility I was naturally highly sceptical of the genius of a seventeen-year-old poet. All that I heard about him sounded like an invention of crazy Thelma’s. I was then capable of believing that she could conjure up subtle torments with which to plague me, since she hated me as much as I did her.

Henry also fictionalized June’s relationship with Jean in Crazy Cock, the central novel of his autobiographical series, written in 1930, but not published until 12 years after his death. June and Jean left together for Paris in April 1927 but by July their relationship fell apart and June moved back to live with Henry. Perhaps two-way relationships couldn’t satisfy her.

. . . . . . . . . .

Henry and June by Anaïs Nin

. . . . . . . . . . .

Henry left June to go to Paris in 1930; June followed him in 1931 and met Anaïs when she visited him. June seduced Anaïs; whether physically or just psychologically isn’t clear: Nin’s diaries don’t refer to any physical relationship with June, just a passionate, emotional one.

She was as smitten by June as she had been by Henry, but in a completely different way; her passion for June was physical, whether consummated or not, where her passion for Henry was certainly consummated but was mainly intellectual: ‘I am already devoted to Henry’s work, but I separate my body from my mind. I enjoy his strength, his ugly, destructive, fearless, cathartic strength’. If Henry was ugly, June was irresistibly beautiful. Anaïs Nin made their first meeting seem like a stroke of fate.

A startlingly white face, burning eyes. June Mansfield, Henry’s wife. As she came towards me from the darkness of my garden into the light of the doorway I saw for the first time the most beautiful woman on earth. Years ago, when I tried to imagine a pure beauty, I had created an image in my mind of just that woman.

I had even imagined she would be Jewish. I knew long ago the color of her skin, her profile, her teeth. Her beauty drowned me. As I sat in front of her I felt that I would do anything she asked of me. Henry faded, she was color, brilliance, strangeness.

A tangled love triangle

The relationship between Anaïs and Henry became three-way: the controlling June seducing the passionate Anaïs. Ironically, though Henry fictionalized June and even Jean, he didn’t write about Anaïs, fictionally or factually; all we know of their relationship is what Anaïs writes about it in her journals, which is quite a lot and often explicit, though entirely from her point of view.

She said in her journal: ‘I want to do [write] June better than Djuna Barnes did Nightwood.‘ But that is a novel. Barnes understood the difference between fiction and non-fiction: her early reportage of New York is totally objective and her fiction, even if closely drawn from the people she knew, totally fictional. Anaïs never did draw that line; the journals are a product of her imagination as much as her novels. Henry and June ends:

Last night I wept. I wept because the process by which I have become woman was painful. I wept because I was no longer a child with the child’s blind faith. I wept because my eyes were opened to reality – to Henry’s selfishness, June’s love of power, my insatiable creativity which must concern itself with others and cannot be insufficient to itself. I wept because I could not believe any more and I love to believe. I can still love passionately without believing. That means I love humanly. I wept because from now on I will weep less. I wept because I have lost my pain and I am not yet accustomed to its absence.

So Henry is coming this afternoon, and tomorrow I am going out with June.

. . . . . . . . . .

Everybody I Can Think of Ever on Amazon U.S.*

Everybody I Can Think of Ever on Amazon U.K*

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post When Anaïs Met Henry: Nin’s Tumultuous Affair with Henry and June Miller appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 5, 2021

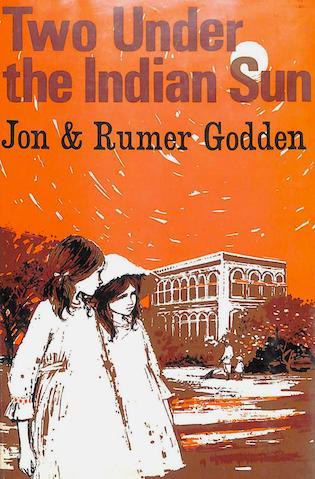

Two Under the Indian Sun: A Memoir by Jon and Rumer Godden

It’s not often that you find two sisters collaborating on a joint memoir, as is the case with Two Under the Indian Sun (1966). That Jon and Rumer Godden did so after becoming successful authors in their own right is all the more interesting.

Among Rumer’s successes were her bestselling novels Black Narcissus and The River, as well as her memoirs, A Time to Dance, No Time to Weep and A House with Four Rooms. Jon’s works include The Bird Escaped, The House by the Sea, and A Winter’s Tale. The two sisters also collaborated on other highly acclaimed works like Shiva’s Pigeon and Indian Dust.

What is remarkable about this memoir is that though it was published in adulthood, the Godden sisters are able to pick up the sheer joy of being two little girls, growing up in India, in a small place called Narayangunj, in undivided Bengal/India, where their father is employed in a shipping company.

The tone of immediacy is so striking that one can almost believe that these two sisters are still children, with their lives still ahead of them, where they could become authors or whatever else that they chose to be.

A happy childhood in India

For a few years, the sisters had been sent away to England to school there and be brought up “properly.” This memoir explores the happiness of their return to India, in contrast to their dull and austere time with their very British Quaker aunts, in England.

The Foreword by the Indian author, Paro Anand describes this memoir “as purely an experiential story of little girls who revel in the colour, flavour and chaos that was and still is India.” This memoir is all about the freedom and warmth of their Indian years, where they can just be children, enjoying the moment and free of any great responsibility:

“Then everything was clear, each thing was only itself: joy was joy, hope was hope, fear and sorrow were fear and sorrow; pain was simply pain; they had not yet trespassed into one another, not merged. Afterwards, life inevitably thickened, became hazed and alloyed, but then it was clear.”

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Rumer Godden

. . . . . . . . .

Some of the interesting aspects of this book are that the authors refer to one or the other’s name throughout so much so that one wonders whether the narrator is a third person, until you chance upon the “we,” when it dawns on the reader that Jon and Rumer are speaking of themselves.