Nava Atlas's Blog

November 5, 2025

Edna O’Brien, Prolific Irish Author of The Country Girls

Edna O’Brien (December 15, 1930 – July 27, 2024) was an Irish-born novelist, memoirist, playwright, poet, and short story writer.

Her work is noted for its lyrical depiction of women, sexuality, loneliness, emotional isolation, desire, survival, and rebellion. (Photo at right by Alessio Jacona, courtesy of Wikmedia Commons)

O’Brien is best known for her first novel, The Country Girls, which, upon its debut, was both denounced and lauded. In her prolific output of fiction, O’Brien challenged taboos related to religion, sex, gender, patriarchy, and persecution.

The Early Years: A Lonely Country Girl

Born Josephine Edna O’Brien in the rural village of Tuamgraney, County Clare, Ireland, she was the daughter of Lena and Michael O’Brien. Ireland was a newly independent, freed from British rule at the time, but women’s lives were largely controlled by the Catholic Church and state.

The youngest of four children, O’Brien’s childhood was marred by turbulence and tension. From the outside, her family appeared to be prosperous, living in a large house on six hundred acres of land. Her parents kept horses and employed farm workers, but money was scarce. O’Brien’s father was an unsuccessful horse breeder who gambled, drank, and was prone to violence.

Raised in a strict Catholic family, O’Brien received her formal early education at the Convent of Mercy, where she excelled in the sciences. Upon graduation, O’Brien obeyed her parents’ wishes and enrolled in a pharmaceutical college in Dublin, and then proceeded to work as a licensed pharmacist. It was in Dublin that O’Brien began to write fiction for The Bell, a literary magazine.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Marriage and Early Writing CareerIn 1952, she met the Irish-Czech writer, Ernest Gébler, who was twenty years her senior. To escape her parents’ disapproval, O’Brien and Gébler eloped in 1954. After several moves, O’Brien and Gébler settled in London in 1960 with their two sons, Carlo and Sasha. Here she found work reviewing manuscripts for the publishing house Hutchinson.

Ian Hamilton, head of the eponymous publisher, was so impressed with her summaries that he and Alfred A. Knopf each advanced her £25 to write a novel. Written in three weeks, through many tears, The Country Girls novel was born. The novel had an immediate polarizing effect on the public.

O’Brien’s success put a strain on her marriage. After reading The Country Girls, her husband told her, “You can write and I will never forgive you.” O’Brien eventually fled her marital home and divorced Gébler in 1968.

She succeeded in winning custody of their two sons after an acrimonious three-year custody battle and a court-sanctioned agreement that she would never allow her children to read her novel August is a Wicked Month. Years later, Gébler continued to attack her, claiming that he had written almost all of her early work.

A Saint or a Sinner?

Her mother also disapproved of her being a writer. In her 2012 memoir, Country Girl, O’Brien writes that after her mother passed away, O’Brien discovered that her mother had inked out offensive language in her copy of The Country Girls.

The Country Girls scandalized her native Ireland, where it was banned and censored by the Catholic Church. While it was acclaimed and admired in London and New York, it was labeled as “filth” by the Irish Minister of Justice. It created such a furor that it was publicly burned in O’Brien’s childhood village by the local parish priest. When she returned for visits, the villagers drew their curtains and treated her as if she were a Jezebel.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Single Life in Swinging LondonIn the 1960s and 1970s, O’Brien led what was perceived by the public as a glittering, glamorous, and libertine lifestyle. This sometimes made it difficult for her to be taken seriously as a writer. She moved to the Chelsea neighborhood of London, where her home became a hub for artists, actors, writers, musicians, and other luminaries.

She threw parties in her Chelsea home, drawing luminaries including Marlon Brando, Jane Fonda, Paul McCartney, Judy Garland, Jackie Onassis, Mick Jagger, Vanessa Redgrave, J.D. Salinger, Samuel Beckett, Francis Bacon, Elizabeth Taylor, and Harold Pinter.

She also explored the use of LSD under the guidance of psychiatrist Dr. R.D. Laing. Reflecting on her time taking LSD, she said it was a turning point in her writing life. She said it deepened her self-knowledge and writing. To her dismay, critics were focused more on her appearance, relationships, and social life than her writing.

Literary influences: Rejoicing in Reading

While working in the Dublin pharmacy in her early twenties, she began reading works by Tolstoy, Thackeray, and other classic writers in her spare time. As a child, she had dreamed of becoming a writer, but it wasn’t until she learned that James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man was semi-autobiographical that she seriously contemplated becoming a writer herself.

James Joyce had a profound influence on her and her writing. She produced nonfiction works about him: James and Nora (1981) and James Joyce (1999).

At the age of 92, O’Brien wrote the play Joyce’s Women. She said she learned more from Joyce than anyone else in the world. O’Brien revered him so much that she was able to quote from his works from memory. Her writing style has been compared to Joyce’s, with its Hiberno-English cadences, rhythms, and syntax.

Other literary heroes such as Virginia Woolf, Lord Byron, and Samuel Beckett likewise became the subjects of plays and nonfiction works. She frequently spoke of her admiration for Chekhov, Tolstoy, Proust, Flaubert, the Brontë sisters, Sylvia Plath, and Shakespeare. Books by her favorite writers were always open on her desk, and pictures of them were displayed in her study. Her voracious appetite for reading made up for her lack of formal literary education.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Themes — the Things We’re Not Supposed to Talk AboutThemes in O’Brien’s novels include the condition of women in society, control of women and their bodies, the insidiousness of patriarchy, love, loss, loneliness, and exile. Her writings deal with the inner lives of characters, as well as politics, religion, and society.

O’Brien said that she wrote about the things we are not supposed to talk about — sexuality and repression (The Country Girls), incest and abortion (Down by the River), and sexual violence and survival (Girl). Her later novels focused on the universality of the female experience.

Following the publication of The Country Girls, the literary magazine Hibernia quoted O’Brien’s husband as saying that her talent “resided in her knickers.” Like many female authors, she endured both casual and pointed sexism from critics.

In an NPR interview in 2019, O’Brien said, “I’ve always written about girls and women, both as victims and as fighters combined, that duality. They’ve been through hell, and somehow they come through.”

In 2015, O’Brien signed a public letter advocating for the repeal of the Eighth Amendment to the Irish Constitution, which restricted women’s access to abortion in Ireland. Through her writing and activism, she addressed the differences and difficulties women face, and paved the way for a new generation of female Irish writers.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Éire and Exile“I live out of Ireland because something in me warns that I might stop if I lived there, that I might cease to feel what it has meant to have such a heritage….” (“Mother Ireland,” The Sewanee Review, Winter 1976)

O’Brien’s native land of Ireland permeates her books and has a significant influence on her writings. Like her literary heroes, Joyce and Beckett, she too became a literary exile. She said that exile and separation were beneficial for her writing; she both loved and hated Ireland. Despite living in England, O’Brien proudly and fervently supported Irish nationalism and freedom from British colonialism.

In 1972, she led a march to protest the incarceration of Irish Republican Army leader Seán Mac Stiofáin. Throughout the 1990s, she followed the Northern Ireland peace negotiations and penned an open letter to then-British Prime Minister Tony Blair, arguing that controversial former Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams should be included in political talks.

In 2006, O’Brien wrote a poem included in a book marking the 25th anniversary of Irish nationalist hunger strikes. Her novel The House of Splendid Isolation is considered an essential document of the “Troubles” in Northern Ireland. O’Brien endured disparaging criticism for her support of a united Ireland, but continued to champion her ideals.

Awards and Honors, Later Years

Despite her critics and controversies, O’Brien was the recipient of many awards throughout her career. Earlier prizes included the Kingsley Amis Award in 1962, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in 1990, and the European Prize for Literature in 1995.

O’Brien received a Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2012 Irish Book Awards. In 2018, she won the Presidential Distinguished Service Award for the Irish abroad, was appointed a Dame of the British Empire for her services to literature, and received the Pen Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature. In 2019, she received the David Cohen prize for Literature and was named Commander of the French Ordre des Arts et Lettres in 2021.

She received honorary doctorates from Galway University, Queen’s University Belfast, and the University of Limerick. In 2006, University College Dublin awarded her the Ulysses Medal.

Edna O’Brien died in London, England at the age of 93 after a long battle with cancer. Commended and controversial in her time, Edna O’Brien will forever be remembered as transforming Irish fiction.

Let’s wrap up this tribute with a thought from earlier in her career: “I loved the idea of writing because it suggested to me that life itself could be rendered more deeply and beautifully than normal life as lived.” (The Irish Times, September 12, 1992)

Contributed by L.C. Canivan.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Further Reading and SourcesConversations with Edna O’Brien edited by Alice Hughes Kersnowski Edna O’Brien on Girl and 6 Decades of Writing ‘Very Difficult’ Stories about Women Interview with Edna O’Brien by Faber Books (October 2012)Imagine: Edna O’Brien: Fearful and Fearless (BBC documentary, 2019) Edna O’Brien, the Controversial Irish Novelist (Obituary; Irish Times) Edna O’Brien Obituary (The Guardian) The Iconoclastic Irish Author Who Wrote The Country Girls Britannica Celebrated Irish Author Edna O’Brien Dies at 93 Literary worksNovels

The Country Girls (1960)The Lonely Girl (later retitled Girl with Green Eyes, 1962)Girls in Their Married Bliss (1964)August Is a Wicked Month (1965)Casualties of Peace (1966)Zee & Co. (1971)A Pagan Place (1971)Night (1973)Johnny I Hardly Knew You (1977)The Dazzle (1981)The Rescue (1983)The High Road (1988)Time and Tide (1992)House of Splendid Isolation (1994)Down by the River (1997)Wild Decembers (1999)In the Forest (2002)The Light of Evening (2006)The Little Red Chairs (2015)Girl (2019)Collections

The Love Object (1968)Three Dublin Plays (1969)A Scandalous Woman and Other Stories (1974)Collector’s Choice (1978)A Rose in the Heart (1979)A Fanatic Heart (1984)Lantern Slides (1990)Edna O’Brien Reader (1994)Mrs. Reinhardt (1996)Irish Revel (1998)Returning (1998)Triptych and Iphigenia (2005)Saints and Sinners (2011)Children’s Books

The Dazzle (1981)A Christmas Treat (1982)The Rescue (1983) Tales for the Telling (2017)Short Stories/Novellas

Shovel Kings (2009)Paradise (2019)Nonfiction

Mother Ireland (1976)James and Nora (1981)Vanishing Ireland (1987)James Joyce (1999)Byron in Love (2009)Country Girl: A Memoir (2012)Anthologies

Arabian Days (1977)Tales for the Telling (1986)New Writing from Ireland (1994)Dramas

A Pagan Place (1973)Zee & Co. (1975)Virginia (1980)Family Butchers (2005)Triptych and Iphigenia (2005)Haunted (2009)The Country Girls (2011)Joyce’s Women (2014)Poetry Collection

On the Bone (1989)

The post Edna O’Brien, Prolific Irish Author of The Country Girls appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 25, 2025

Contemporary Iterations and Adaptations of Frankenstein – What Would Mary Shelley Have Thought?

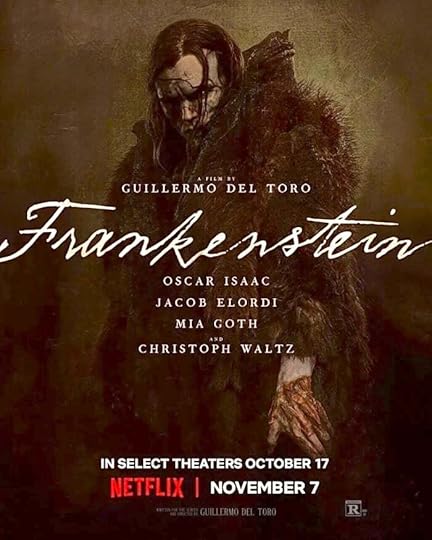

Despite having been written more than 200 years ago (published in 1818, to be exact), Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has stood the test of time. There have been around a thousand adaptations of the story to date — with yet another, the 2025 film Frankenstein from the most recent to have joined their ranks.

In her book, with Frankenstein’s creature as her canvas, Mary Shelley (1797 – 1851) formed a distinct picture of society. Our “good” side manifests in the creature’s unexpected intelligence and elegant language, yet the “bad” layers of depression and violence begin to show as the story unfolds.

. . . . . . . . . .

Guillermo Del Toro’s Frankenstein (2025) is the latest adaption,

and it likely won’t be the last

. . . . . . . . .

Contrary to Shelley’s nuanced approach to human nature, popular adaptations such as The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), Frankenstein Unbound (1990), and the most iconic of all, the 1931 horror classic starring Boris Karloff, have depicted the creature as a psychotic, murderous, and one-dimensional monster.

Have the lessons of the novel warped over time? Does popular culture see Frankenstein’s creature as anything beyond a villainous, monstrous caricature? And how have interpretations of the story changed since 1818 — especially as various sociopolitical issues, like feminism and environmental justice, have arisen throughout the 20th and 21st centuries?

. . . . . . . . .

Mary Shelley was barely out of her teens when she wrote Frankenstein

. . . . . . . . . .

Let’s explore a few of the countless adaptations of Frankenstein, how their values compare to the original, and most importantly (for our purposes anyway!), and speculated whether Mary Shelley would have approved based on her own politics and personal experience.

In the context of this article in mind, we can all go forth and experience del Toro’s iteration — and make our own judgments about Shelley’s possible opinions. We’ll start with another iconic film featuring Oscar Isaac as the creator…

. . . . . . . . . . .

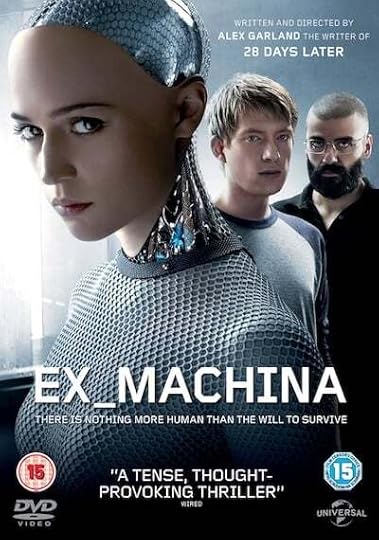

Ex Machina, dir. Alex Garland

Medium: Film

Year of adaptation: 2014

AI is rampant in our culture today, but the concept of it obviously originated much earlier. Indeed, Frankenstein’s monster is a patchwork of human parts, just as AI is a patchwork of human data. In Shelley’s story, the monster is eloquent and even charming — again, much like AI. But despite resembling a human being in many ways, the monster is not human, and is mistreated as a result.

This idea echoes through Ex Machina — a modern rendition of Frankenstein that reimagines the monster as a humanoid female robot named Ava. Though Ava is capable of intelligent thought, her creator Nathan disrespects her, viewing her as his own product rather than as an autonomous being. Nathan isolates Ava in his laboratory, controls her interactions, and it’s implied that he sexually abuses her as well — leaving us to wonder who the real “monster” is.

Both Ex Machina and Frankenstein shine a harsh light on the dangers of self-absorbed creators and unexpectedly powerful inventions. Nathan attempts to control Ava, convinced she is nothing more than a machine that wouldn’t exist without him. His moral failings and short-sightedness lead to his downfall.

Similarly, Victor Frankenstein obsesses over the idea of creating a new life, yet the reality of the creature’s autonomy plunges his life into chaos. Ultimately, instead of seeking redemption or trying to understand the creature, Victor obsesses over ending its life — a misguided venture that ends in his own death.

Mary Shelley’s exploration of the relationship between a creator and creation was likely influenced by her own upbringing. Her mother was an influential feminist, but died just days after giving birth to her.

Isolated throughout childhood, seventeen-year-old Mary sought solace in the arms of the poet Percy Shelley — a relationship her father disapproved of deeply. Mary’s father was more concerned with his status and reputation than preserving his relationship with his daughter — just as Victor Frankenstein and Nathan disregard their creations in favor of their own preferences and motives.

It would be fair to say that Mary Shelley likely would have appreciated Ex Machina as a (loose) adaptation. Furthermore, centuries before AI existed, Shelley was exploring the potential of artificial creation and themes of hubristic, selfish creators.

One clear undercurrent of Frankenstein is the importance of compassion, even for things we do not necessarily understand — an undercurrent that’s mirrored in Ex Machina. This may be one of the main reasons her work remains relevant (and frequently adapted) today.

Mary Shelley’s estimated approval rating:

. . . . . . . . . . .

Poor Things, dir. Yorgos Lanthimos

Medium: Film

Year of adaptation: 2023

Poor Things took the world by storm when it was released in 2023. The film was hotly debated, with some viewing the story as ableist and gratuitous, while others claimed it was a feminist masterpiece. But what would Mary Shelley have thought?

Poor Things follows the life of Bella Baxter, a pregnant woman found dead by a troubled scientist named Godwin Baxter (a clever reference to Shelley’s maiden name). In an attempt to revive the woman, Godwin transplants the brain of her unborn child into her body. The twisted result is a seemingly grown woman with the mind of an innocent child — just as Frankenstein’s monster is created to be innocent and unknowing, at least at first.

Like the creature, Bella soon realizes that this world is not cut out for her. Many people try to take advantage of her, for her innocence and because she is a woman.

She’s constantly treated as possession rather than as a person, and specifically as a sexual object — especially disturbing given her childlike demeanor and speech. Still, the film does a good job (in this writer’s opinion) of keeping the tone amusingly satirical while also placing any ethical blame squarely on Bella’s would-be suitors.

Another loose Frankenstein interpretation — and one of the most iconic — strikes a similar tone. Richard O’Brien’s Rocky Horror Picture Show is a delightfully camp play in which a mad scientist creates the perfect lover for himself. And in both Poor Things and Rocky Horror, we see how satire can temper morbidity — something we don’t see in the original Frankenstein.

But while these more modern adaptations might have more fun, their moral impact is slightly lessened. Shelley’s novel raises philosophical questions in an eloquent, contemplative style (some might say “brooding”); these traits have helped make it into a literary classic.

Still, Poor Things — like Frankenstein, and also Ex Machina — raises important questions about control, freedom, and attraction. Just as Bella is confined and subjugated by those around her, so too is Frankenstein’s monster oppressed by his creator and by society. Poor Things arguably portrays Frankenstein’s power dynamics in an even blunter way, forcing the viewer to consider the dark implications of wielding power over the vulnerable.

Despite sharing similar values, though, it’s tough to say whether Mary Shelley would have enjoyed Poor Things. Shelley’s penchant for dark themes without comic relief perhaps means she wouldn’t have cared for a lighthearted adaptation like this one.

Mary Shelley’s estimated approval rating:

. . . . . . . . . .

Medium: Book

Year of adaptation: 2019

In Frankissstein, one of her most recent novels, author Jeanette Winterson offers a sharp critique of society and human nature that echoes Mary Shelley’s social commentary. Both raise the question: can a corrupt society beget anything other than corruption? Furthermore, is a creation always morally compromised by its creator?

The novel’s protagonist Ry Shelley refers to themselves as a “hybrid”— neither male nor female. While Ry’s exploration of identity is rooted in human experience, we soon discover that a scientist called Victor Stein has different ideas for what human existence should be.

Combining identity with technological advancement, Stein envisions a future where humans can upload themselves to a vast AI mind. The story runs parallel to the exploits of Ron Lord, a businessman who favors AI for the creation of female sex robots.

Similar to the male characters in Poor Things, the characters of Victor Stein and Ron Lord clearly embody the dangers of toxic masculinity, albeit in contrasting ways. Like his progenitor Victor Frankenstein, Victor Stein aggressively pursues his technological goals with little concern for the consequences. Ron Lord, meanwhile, is selfish in a different way: less egotistical than simply misogynistic and entitled.

Of course, many would say that the original Frankenstein critiques toxic masculinity as well. Female voices in Shelley’s novel are largely silenced, overshadowed by the character arcs of Victor and his (male) creation. Female characters are sources of existential anguish (Victor’s mother), victims of the monster (Elizabeth Lavenza), or ideas which never come to fruition (the female mate for the creature).

On the surface, it might seem sexist not to have more female characters in Frankenstein — but as with the lascivious male characters in Poor Things, the absence of more substantial female representation here is commentary in and of itself.

Back to Winterson’s novel. In Frankissstein, present-day stories are skillfully interwoven with historical characters, including Mary Shelley herself. Shelley’s own life occurs in the book as it did 200 years ago, but with one twist — her creation, Victor Frankenstein, appears in her life as a real man.

These cleverly interwoven narratives suggest a multi-layered purpose to such a story: not only the author’s self-expression, but also what she imparts with her characters. Whether or not they are truly “alive”, our ideas have the capacity to take on lives of their own.

Winterson also contrasts Shelley’s ideas with modern existentialism, forcing the reader to consider the differences between morality in the 19th century vs. the modern day. And just like Victor Frankenstein and his monster, we start to realize there are more similarities between the two than it might originally seem.

This message — combined with their shared critique of toxic masculinity and the message of taking responsibility for our creations — makes Frankissstein an adaptation that Shelley would almost certainly have loved.

Mary Shelley’s estimated approval rating:

. . . . . . . . . .

Spare and Found Parts by Sarah Maria Griffin

Medium: Book

Year of adaptation: 2016

Sarah Maria Griffin’s dystopian novel Spare and Found Parts is set in a city, “The Pale,” which has been devastated by an epidemic. Many of its inhabitants have lost their original limbs and now have biomechanical ones. Our protagonist, Nell, has a literal mechanical heart — and aptly, she has always longed for connection and companionship. When she realizes she can build a friend for herself using other “spare and found parts,” she jumps at the chance.

But despite being a main character who creates life, Nell is the spiritual opposite of Victor Frankenstein. The Pale demands that each of its residents “contribute” something to the society once they come of age — and though Nell is a capable inventor, she’s extremely conscientious about her creations.

Unlike Victor, she cares that her new robot friend is looked after; also unlike Victor, Nell remains a clear force for good, even as dark forces threaten to encroach. Aside from her inherent morality, it’s possible that her own mechanical build might influence the empathetic approach to her creation. And there’s certainly a pure-of-heart message here about how our similarities are more important than our differences.

By transplanting the creator role onto a self-aware and socially conscious teenager, Griffin turns Shelley’s ideas into an uplifting story with a happy ending. Nell’s staunch integrity works as a rebuttal of sorts to Shelley’s warning on the corrupting nature of power — which maybe gives modern readers a bit of hope.

It’s unclear whether Shelley herself would have liked this, however. Her key themes in Frankenstein were intentionally macabre in order to reflect a dismal, decaying society and its corruptible citizens. That said, perhaps she would have appreciated a happier ending, given the torment that seemed to haunt her own life.

Mary Shelley’s estimated approval rating:

. . . . . . . . . .

Frankenstein has now outlived its creator by almost 200 years, and has grown from humble beginnings into its own formidable monster. Its influence continues to grip popular culture today, with more adaptations flowing out of pages and cinemas — and with the rise of AI, there’s no doubt that this cautionary tale still holds relevance. I bet Mary Shelley would have loved that.

Contributed by Juliet Allarton, a writer with Reedsy. In her spare time, Juliet enjoys reading fiction, working on her novel, and songwriting. She loves introspective stories that focus on people over plot, and her favorite book at the moment is Daughters of the Nile by Zahra Barri.

The post Contemporary Iterations and Adaptations of Frankenstein – What Would Mary Shelley Have Thought? appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 17, 2025

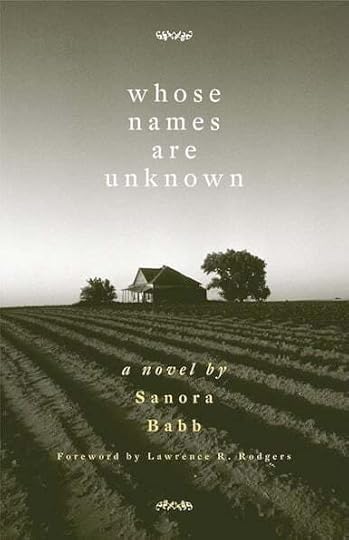

Sanora Babb, author of Whose Names are Unknown

While living in Southern California during the Great Depression of the 1930s, Sanora Babb (April 21, 1907 – December 31, 2005) learned of the plight of the Dust Bowl migrants.

Babb began working for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), taking detailed, copious notes about the lives of migrants. She aimed to write a novel based on the notes, hoping that it would foster sympathy and understanding for the plight of migrant workers.

Her FSA boss, Tom Collins, introduced Babb to novelist John Steinbeck. Collins asked Babb if she would allow Steinbeck to review her notes. Random House already planned to publish Babb’s “exceptionally fine” novel, but before she finished it, Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath (1939) was flying off the shelves.

Random House reneged on Babb’s book deal, claiming that there wasn’t room in the market for two novels about Dust Bowl migrants. It was only many years later that it came to light that Steinbeck used Babb’s notes extensively in writing The Grapes of Wrath. Babb didn’t seem to hold a grudge and went on to lead a singular and exceptional life.

The Early Life of Sanora Babb

Sanora Babb was born in 1907 in the Oklahoma Territory to Walter and Jennie Babb. Though white people settled the town, Red Rock sat in the midst of Otoe–Missouria territory. As she grew up, Sanora was drawn to the Native ways. The loving family unit, kindness, and sharing were in stark contrast to her own volatile home life.

It’s unclear why Sanora Babb’s father called her Cheyenne. But thanks to her later writing, we learn that added Riding Like The Wind to Cheyenne.

Chief Black Hawk enjoyed having little Sanora around. One day, he brought Sanora a pinto pony. After he set her on the pony, a loud noise spooked it, and the pony, with her sitting on its back, ran off. The chief leapt on his own horse and soon caught up with them. Seeing Sanora still secure on the pony’s back, the chief named her “Cheyenne Riding Like The Wind.”

In that one gesture, Chief Black Hawk gave Sanora Babb something that would stabilize her for her entire life: a name. It could be that in naming her Cheyenne Riding Like The Wind, Chief Black Hawk gave a little girl a sense of power she would harness for the rest of her life.

Sanora must have observed the subtleties and powers of the wind; it is almost a character in much of her writing: The way a gentle breeze carries pollen across tall stalks of broomcorn or, in an instant, becomes powerful enough to bend a crop down in long, shimmering rows.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

A Dugout in Eastern ColoradoAs a child, Sanora moved around quite a bit. Her father, Walter Babb, was an accomplished baker, but preferred gambling and playing semi-pro baseball to day-to-day labor. He was often gone from home, which left Sanora’s mother, Jennie, to work in the bakery and cover for her husband’s absence.

When Sanora was seven years old and her sister Dorothy five, Walter spent the family’s money on a 320-acre piece of land in Eastern Colorado. The family moved into a dugout with Alonzo Babb, Sanora’s grandfather (whom they called Konkie), with high hopes of becoming successful broomcorn farmers.

At first, Sanora missed her Otoe family, her pony, and town life, but soon grew fond of the wide open sky, with its nighttime glory of stars and big moon. She loved the never-ending plains covered in buffalo grass and ground cacti. In their years on the plains with farms miles and miles apart, Sanora befriended many animals and appreciated the local plant life.

Sanora saw animals as equal to humans, living their lives the same as she was living hers — they had eyes to see, and she could look into them. From horses to chickens, horny toads to prairie dogs, she gave every animal and plant she encountered a place of importance. Every waft of sage or knot of buffalo grass, or honk of a goose, each howl of the wolf or coyote. Every sword-leaf of the yucca plant, and soft fluff of the cottonwood, inspired Sanora’s empathy.

Sanora Babb’s Writing Career Begins

The family came close to starving on several occasions, sometimes drinking red pepper tea to assuage their stomachs. They emerged from the dugout and other bare and rank homesteading attempts on the long prairie to land in Elkhart, Kansas, when Sanora was eleven and her sister nine years old.

Over several years, the girls had only read from either Konkie’s only book (about Kit Carson) or the newspapers glued to the walls of their dugout. Sanora had to study hard to get into a class with students her own age, and she, like the rest of her family, was thin and weak from their privations on the plains. That was when she decided she wanted to be a writer when she grew up, and set things into motion to make it happen.

She stepped into the writing arena with her first English assignment at her new school, an essay entitled How to Handle Men, a piece about women and families, and against the violent oppression her family suffered at the hands of her father.

When Sanora was twelve, the family moved to Forgan, Oklahoma, where she began working for a printer, and then at a newspaper. She wrote plays that her troupe of classmates performed for the town, and discovered her passion for writing short stories.

Sanora graduated from high school as Valedictorian of her class. After earning a teaching certificate, she worked as a school teacher for a year while continuing to submit her poetry and short stories to newspapers and periodicals. The Associated Press dubbed her the “Prairie Verse Writer” and announced her successful poetry contributions in newspapers across the country.

When she left teaching, Sanora attended Garden City Junior College and earned an Associate’s degree. She took a job as a reporter for the Garden City Herald, advancing in this post while gaining national attention as a talented poet.

Relocating to Los Angeles

In 1929, Babb moved from her parents’ volatile home in Kansas to Los Angeles in the hopes of finding work as a journalist. In the aftermath of the stock market crash, newspapers weren’t hiring, so she took work as a secretary at Warner Brothers and as a scriptwriter for the radio station KFWB. When she lost her job at the radio station, she began ghostwriting screenplays.

These jobs allowed her enough spare time to spend at the public library, enriching her reading habits. She continued to publish poetry and short stories in literary magazines across the country. Babb met many fellow writers who also spent their free time at the library.

In 1933, a little magazine entitled The Midland published Babb’s short story, The Old One. Her talent for short fiction was evident; her prose was immersive and evocative. Babb published some work in a socialist magazine, The Anvil; her stories and poems were also published in the Prairie Schooner.

Babb’s professional acquaintances included up-and-coming writers, including Carlos Bulosan, William Saroyan, and John B. Sanford (b. Julian Lawrence Shapiro). Many writers of the time professed to be Marxists and wrote for popular leftist publications such as The Daily Worker, The Anvil, New Masses, and others.

Although Babb was not a political activist per se, she “was attracted to … the idealism of saving the world.” Babb continued to stay true to her vision of exploring the human experiences, writing with a “quiet intensity and brooding beauty which is missing in most of the hard boiled, out house fiction to be found in the average revolutionary (left wing) little magazine.” (Dunkle)

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Working for the FSABy the mid-1930s, Dust Bowl migrants were flooding into Los Angeles and the surrounding region. The drought, dust storms, and Great Depression continued to devastate farmers of the hardest-hit panhandle area that encompassed Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas. This forced hungry, tatter-clothed families to go west in search of jobs.

Babb saw an opportunity to help migrant families, something she was already doing in her writing as well as editing of union journals. She also volunteered for the Farm Security Administration, working alongside Tom Collins to set up government camps for migrant workers. During the eight months Babb worked with the FSA, she took copious notes from her interviews with hundreds of families.

She was sometimes joined by her sister Dorothy, who took photographs. They hiked the dirt roads of the Imperial Valley, documenting the living conditions in the camps with the intent of increasing awareness and sympathy. Her experience as a reporter made her adept at taking thorough and useful notes.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Grapes of Wrath — from Sonora Babb’s NotesIn Riding Like The Wind: the Life of Sanora Babb, Iris Jamahl Dunkle describes a blatant instance of one writer stealing from another in telling how John Steinbeck obtained the material for writing The Grapes of Wrath:

“Little did Babb know that the copy of her field notes she would willingly give Steinbeck would not only inspire him as he began his third and final attempt at writing the Dust Bowl novel, but would also make the publishing of her own novel impossible. As she later reflected, ‘Tom Collins…had asked me to keep detailed notes of our work every day, of the people, things they said, did, suffered, worked. I thought it was for our work, or for him, but it was for Steinbeck’ and ‘Tom asked me to give him my notes. I did. Naive me.’”

The Grapes of Wrath sold 450,000 copies within the first five months of its release in 1939. It won the National Book Award and a Pulitzer Prize. John Ford made it into a film in 1940. The book was a catalyst for bringing the plight of Dust Bowl migrants to the center of American conversation. The book was so popular that when Babb delivered her novel to Random House, although they felt the story was “exceptionally fine,” the publisher explained that the market couldn’t support two Dust Bowl novels.

The publication of Whose Names Are Unknown was canceled, even though it was quite a different novel from Steinbeck’s. The Grapes of Wrath portrayed the migrants — or “Okies” — as poorly mannered and undereducated. Babb’s interpretation, in contrast, presented loving, humane, honest, and steadfast families who lost everything they ever knew to the perfect storm of Dust Bowl and Great Depression conditions.

The title Whose Names Are Unknown reflects the eviction notices on the doors of failed farmers. It’s the story of farming families and their neighbors, with all their dreams and aspirations. With Babb’s background as a poet and short story writer, she chose the exact word to captivate hearts and minds. Here is such a scene in chapter seven, when Milt’s longed-for son is stillborn:

The coyotes are liable to dig him up some night, he thought. It made him feel sick. He walked quite a ways beyond the cane into a field that was lying fallow and dug a very deep hole. The earth was dry and hard beneath the moisture from the rain. He got on his knees and put the baby carefully in the hole. He could not resist looking once more. The little boy was curled up, wrinkled and queer-looking as if he had been alive a long time …The puckered face looked unborn and helpless.

Recovering From Her Loss

Although Random House had commissioned her manuscript, now it seemed permanently shelved. Babb worked her way through the disappointment, and returned to writing for newspapers, magazines, and small presses. The Best American Short Stories (1950) published her short story The Wild Flower before it was translated into twenty languages.

She also edited for friends and literary magazines. In the ensuing years, she became friends with Ralph Ellison, and joined a writers group that would gather for forty years. Ray Bradbury was also a regular participant. She and husband James Wong Howe (whom she married in 1937, though the marriage wouldn’t be legally recognized until 1948, when the California Supreme Court overturned the state’s anti-miscegenation laws) owned and operated a star-studded Chinese restaurant in Chinatown. Her sister, Dorothy, was their bookkeeper.

. . . . . . . . . . .

James Wong Howe and Sanora Babb (photo by Dorothy Babb, 1937)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Publication of The Lost TravelerIn March 1958, The Lost Traveler was published in the United States and England. It was the second novel Babb’s had written (the first, of course, was Whose Names are Unknown), but her the first to be published.

With The Lost Traveler, Babb present a strong female character while also telling the story of a gambling father. After many rejections from publishers who preferred a gentler, more acquiescent female and upright father figure, she finally found a publisher who allowed her to tell the story in the way she wanted.

In his syndicated column, Literary Lantern, reviewer Caro Green Russell quotes Babb: “I feel very grateful to my father, who was a professional gambler, because the uncertain life he provided gave me so many and varied experiences from an early age …” and “We rode in wagons, and covered-wagons for trips; lived in a dugout in the ground, went to the creek for water for bathing, tried to farm without rain, and nearly starved.”

The April 14, 1958, Los Angeles Mirror newspaper gave The Lost Traveler a fair review, first a nod to the father in the story, Des, then to the family, and finally to the daughter, Robin. In the review, Bob Campbell wrote, in part:

“Sanora Babb has done a remarkable job of making the hero, Des Tannehill, sympathetic and understandable in spite of his occupation and occasional brutality. In fact, she has made the whole Tannehill family come alive, particularly Robin, the older daughter, the only member of the family with fortitude enough to stand up to her father.”

Babb refused to write complacent women and heroic men into her work to please publishers. Babb wrote about women and children who were too often at the mercy, whims, and fists of men. She committed to her singular goal, akin to Robin (the sixteen-year-old daughter of Des in The Lost Traveler), who tells her father she was alive with purpose:

“Well, I feel so alive I could burst!” She leaped up from the chair and whirled to the door, turning her back on him, pretending to look out, saying passionately, “I feel connected with everything, buffalo grass, meadow larks, lizards, rocks, wind — everything! I feel in tune with the universe!”

A few lines later, Robin tells Des about her feelings and dreams:

“I think they’re like seeds, moving in the ground, bursting with sprouts, ready to grow into beautiful and useful plants. Like wheat or a peach or a rose or even a weed.”

The Lost Traveler is full of rich, vibrant prose. Each word places the curious reader in the middle of the scene, designed to deliver a wealth of lived experiences to the poetic soul.

Throughout her writing career, Babb was quite faithful in looking after Dorothy, who suffered from mental issues. Babb was also painstaking in her care for her husband in a rather traditional fashion, often traveling to film locations all over the world as his career soared. She also continued to help her writer friends whenever they asked anything of her.

Best American Short Stories and an Autobiography

Best American Short Stories (1960) featured The Santa Ana, which first appeared in the Saturday Evening Post. It was described in the press as romantic and beautifully written with a “fine appreciation of the weather on human emotions.” (The Gazette, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, September 18, 1960)

In 1970, Babb published An Owl On Every Post, an autobiographical novel. She carefully altered the names and descriptions of the characters and some of the places. The book took more than ten years to write, but once published, it sold very well.

Babb was gratified to learn that so many people were reading the book, which described her family’s experiences in dry farming on the Great Plains from 1913 to 1917. For several years, Babb presented talks, attended luncheons, and gave interviews about An Owl On Every Post.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Working Through To The Final Days To Get Stories ToldAfter her husband’s death in 1976, Babb dedicated several years to archiving his work. She went on to publish collections of her short stories: The Dark Earth; The Killer Instinct and Other Stories from the Great Depression (1987); Cry of the Tinamou: Stories (1997); and a collection of her poems, Told in the Seed (1998).

Not long after the publication of Whose Names Are Unknown, the extent to which Steinbeck used Babb’s research became known in literary circles. Her field notes, along with photos taken by Dorothy, are collected in a 2007 book, On the Dirty Plate Trail: Remembering the Dust Bowl Refugee Camp, arranged and presented by Douglas Wixson. Ken Burns’ 2012 documentary, The Dust Bowl features Babb and Whose Names Are Unknown.

Sanora Babb passed away in 2005, with a promise from her good friend, Joanne Dearcopp, to keep her works in print for as long as possible. Keeping to her word, Whose Names Are Unknown was finally published in 2006. Readers may prefer it to Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath for its humanity, its beauty, and its living, breathing life on the page.

Sources and further readingDunkle, Iris Jamahl, Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb (pp. 100, 173)

“Those Good Old Days: Pioneering in a Soddy” by Jack Conroy. Kansas City Star, December 29, 1970.

Poetry in The Prism magazine and The Northern Light, The Hutchinson News, Friday Sep 30, 1927

https://www.newspapers.com/image/8026170/?match=1&terms=sanora%20babb

https://www.newspapers.com/image/9180...

view clip prairie verse writer https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-gazette-and-daily-poet-of-prairies/177800118/

The Daily Worker, January 26, 1935, page 7.

communist short story: https://www.newspapers.com/image/754603372/?match=1&terms=sanora%20babb

Santa Ana, Saturday Evening Post https://www.newspapers.com/image/524708895/?match=1&terms=sanora%20babb

“Wife of Motion Film Cameraman Writes of Childhood on Plains”

“Short Story Art Growing” (Pittsburgh Post Gazette)

https://www.newspapers.com/image/683092461/?match=1&terms=sanora%20babb

weather, human emotions. https://www.newspapers.com/image/5492...

The post appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 12, 2025

Toni Cade Bambara: Writer, Activist, Culture Worker

Toni Cade Bambara (born Miltona Mirkin Cade, March 25, 1939 – December 9, 1995) was a writer, civil rights activist, teacher, and documentary film-maker.

Well known for her 1980 novel The Salt Eaters, she was also hugely influential in the Black liberation and feminist movements. Her writing was inspired by the Black communities in which she lived and worked. She was concerned with injustice and oppression in general and of Black people in particular.

“A large repertoire of stories”: Growing up in Harlem

Toni was born in Harlem, New York. She spent her childhood and adolescence with her parents, Helen Brent Henderson Cade and Walter Cade, and her older brother, Walter Cade III, in Harlem and in Jersey City.

She changed her name from Miltona to Toni at the age of six. Much later, in 1970, she added the name “Bambara” – a national language of Mali and the name of a West African ethnic group, after seeing it inscribed in one of her great-grandmother’s sketchbooks.

Her mother encouraged her daughter in reading and the arts, and was a community activist in some of the organizations that sprung up in Harlem. That meant that music, theatre, writing, and activism were all bound up for Toni from an early age.

She was an average student in most subjects. Her fifth grade teacher at The Modern School, a private Black-run all-girls’ school in Harlem, reported that she was “not outstanding from either a scholastic or social point of view.” She did excel in creative writing, and she spent a lot of time at the New York Public Library. Later, she would cite poets Gwendolyn Brooks and Langston Hughes as major influences on her writing and her activism.

Graduate lifeAlthough Toni considered studying medicine, she graduated from Queens College in 1959 with a BA in Theatre Arts and English Literature. She was active in various forms of the arts in college, and was a member of its dance club, and in theatre groups where she took on backstage roles such as stage manager and costume designer. She also won the university’s John Golden Award for Fiction.

In 1961 Toni traveled to Europe. There, she studied Comedia dell’Arte at the University of Florence, and mime at L’Ecole de Mime Etienne Decroux in Paris. On her return to America, she completed an MA in Modern American Fiction from City University of New York.

Toni worked in social services to support herself, as a social worker at the Harlem Welfare Center and an occupational therapist in the psychiatric ward of the Metropolitan Hospital.

After completing her graduate studies in 1965, she was offered the chance to help with the development of City University’s SEEK (Search for Education, Elevation, Knowledge) program for economically disadvantaged students. She continued to teach there until 1969, when she was appointed assistant Professor of English at Livingston College (part of Rutgers University).

In 1970, she had a daughter, Karma Bene Bambara Smith, with her partner Gene Lewis.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Writing as transformationToni’s activism work and her writing grew side by side: “Writing,” she said, “is one of the ways I participate in transformation.”

In 1970, she edited and published one of the first major anthologies of Black women’s writing, The Black Woman. It included well-known and celebrated writers like Audre Lorde, as well as some of her undergraduate students and other unknown writers, all of whom were underrepresented in the male-dominated civil rights movement and in the white-dominated feminism movement.

This was followed in 1971 by Tales and Stories for Black Folks, which celebrated what she called “our great kitchen tradition.” Toni was one of a group of Black women fiction writers in the 1970s, including Alice Walker and Toni Morrison. The latter would become her editor and a lifelong friend.

Her debut collection of short stories, Gorilla, My Love, was published in 1972, and her first novel The Salt Eaters (1980) won the American Book Award and the Langston Hughes Society Award. Another collection of short stories, The Sea Birds Are Still Alive, was published in 1977, and another novel Raymond’s Run in 1990.

Toni Cade Bambara’s stories were set in either the rural South or the urban North, and use dialect to portray the lives of African Americans (often activists) and their communities. She consciously used language to try and explore the Black experience:

“…there have been a lot of things going on in the Black experience for which there are no terms, certainly not in English, at this moment. There are a lot of aspect of consciousness for which there is no vocabulary, no structure in the English language which would allow people to validate that experience through language. I’m trying to find a way to do that.”

Toni Morrison said of her writing, “[It] is woven, aware of its music, its overlapping waves of scenic action, so clearly on its way … like a magnet collecting details in its wake, each of which is essential to the final effect.”

At the same time, Toni was involved in Black and women’s liberation. She envisaged multicultural movements that crossed geographical boundaries, and in the early 1970s, she traveled to Cuba and Vietnam to learn from and forge connections with women’s organizations these countries.

Move to Atlanta

In 1974 Toni moved with her daughter to Atlanta, Georgia. Old family connections were part of her reason for moving: “My people are from Atlanta. My mama’s folks are from Atlanta. My Daddy’s folks are from Savannah. I’ve always been very at home in the South…”

There she taught writing and Afro-American Studies at Spelman College, Emory University and Atlanta University, and became involved in the Black Arts Movement as a writer-in-residence at the Neighborhood Arts Center. When Spelman turned down her proposal for a course specifically on Black women writers, she began to teach it from her home. This gathering became the Pamoja Writing Workshop, which later turned out award-winning writers such as Shay Youngblood and Nikky Finney.

Fellow Atlanta writer Pearl Clearge recalled that Toni said “that she didn’t like to call herself an artist because then it made you start acting precious like you were so above everybody else, that she thought we should call ourselves cultural workers because we were no better than people who worked in factories, no better than people who taught school, no better than people who were nurses and doctors and all of that. We were cultural workers.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“A tremendous capacity for rage”— writing as activismBetween 1979 and 1981, a spate of about forty child kidnappings and murders — teens and young adults, mostly boys — rocked the Black community in Atlanta. Toni got involved in helping to disseminate accurate information, organizing neighborhood patrols, and monitoring the media amidst a climate of fear and mistrust.

Out of this came what many consider to be her finest novel, Those Bones Are Not My Child, originally titled If Blessings Come and published posthumously in 1999 by Toni Morrison. It was a testament to the power of Toni Cade Bambara’s passion for activism that had become the hallmark of her work.

In a 1982 interview with Kay Boneti of the American Audio Prose Library, Toni said, “When I look back at my work with any little distance the two characteristics that jump out at me is one, the tremendous capacity for laughter, but also a tremendous capacity for rage.”

In 1985 she relocated to Philadelphia, and taught film script writing at the Scribe Video Center. Alongside Louis Massiah, the founder of the Center, she worked on various documentaries. She sometimes produced, wrote, or narrated, and sometimes all three — including The Bombing of Osage Avenue (1985), and Seven Songs for Malcolm X (1993).

Toni was diagnosed with colon cancer in 1993. She continued to work, and one of her final projects was the 1995 documentary W.E.B. DuBois: A Documentary in Four Voices.

The Legacy of Toni Cade Bambara

Upon her death in 1995, the New York Times called her a “major contributor to the emerging genre of contemporary black women’s literature.” She was posthumously inducted into the Georgia Writers’ Hall of Fame in 2013, and since 2000, Spelman College has hosted an an annual Toni Cade Bambara Scholar-Activism Conference to honor her legacy of involvement in activism.

In 2025, the film TCB – The Toni Cade Bambara School of Organizing was released to critical acclaim, and won two documentary prizes at the BlackStar Film Festival. Directed by Louis Massiah and Monica Henriquez, it’s an intimate account of her life, told through archival footage, sound recordings, photos, animation, and interviews with her family, friends, students, and fellow writers and editors.

Further reading and sources Georgia Writers Hall of Fame Resembling a Revolutionary: My Sister Toni Remembering and Honoring Toni Bambara Archive at Spelman College Southern Collective of African American WritersMajor works

Short story collections

Gorilla, My Love (1972; notable story: “Blues Ain’t No Mockin Bird”)The Lesson (1972; notable story: “ The Lesson ”)The Sea Birds Are Still Alive (1977; notable story: “ Sweet Town ” )Novels

The Salt Eaters (1980) Those Bones Are Not My Child (1999)Screenplays (produced)

Zora. WGBH-TV Boston, 1971The Johnson Girls. National Educational Television, 1972.Transactions. School of Social Work, Atlanta University 1979.The Long Night. American Broadcasting Co., 1981.Epitaph for Willie. K. Heran Productions, Inc., 1982.Tar Baby. Screenplay based on Toni Morrison’s novel, 1984.Raymond’s Run. Public Broadcasting System, 1985.The Bombing of Osage Avenue. WHYY-TV Philadelphia, 1986.Cecil B. Moore: Master Tactician of Direct Action. WHY-TV Philadelphia, 1987.W.E.B. Du Bois: A Biography in Four Voices, 1995Anthologies and biography

The Black Woman: An Anthology (edited), 2005Deep Sightings and Rescue Missions: Fiction, Essays and Conversations(edited by Toni Morrison), 1996A Joyous Revolt: Toni Cade Bambara, Writer and Activist

by Linda Janet Holmes, 2014

The post Toni Cade Bambara: Writer, Activist, Culture Worker appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 5, 2025

Bessie Head: Botswana and South Africa’s Shared Literary Great

Bessie Amelia Emery Head (July 6, 1937 – April 17, 1986) was a novelist, journalist, and poet born in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. She later left for Serowe, Botswana, and became an established literary figure across these two countries’ borders.

This overview of the life and work of Bessie Head is an introduction to this notable literary figure who was instrumental in gaining a more international voice for African peoples.

A complicated early Life

Bessie was born in a psychiatric hospital where her mother, Bessie Amelia Emery, was institutionalized, and where she remained for the rest of her life. As reported by South Africa’s Sunday Times Heritage Project:

“According to the racial legislation of the time, Bessie was classified as white and was placed with a white adoptive family. However, her racial identity later became blurred as the white family’s lawyer noted: ‘The child is Coloured, in fact quite black and Native in appearance.” The state authorities hastily removed Bessie and placed her under the care of a ‘Coloured’ adoptive family, George and Nellie Heathcote.”

Bessie was removed from the Heathcote’s home by social services around the age of twelve. This started the process of feeling alienated from her heritage, stemming from the fact that she was considered mixed race or ‘coloured’ under the South African government’s racial classification.

Documented in a letter to her publisher for a never-completed autobiography, she wrote that she was “as anxious to avoid any knowledge of my mother’s white relatives as they were anxious to destroy my mother and disown me.”

Early journalism and writings

Bessie began teaching in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, and held the position from 1956 to 1958. Her first newspaper job was working for the Golden City Post in Cape Town. Around 1959, she joined Home Post at their Johannesburg offices.

She was inspired by the writing of Mohandas Gandhi and Robert Sobukwe, (the founding member of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). Her letters would compare Gandhi and his writing to being Godlike, and she particularly admired his contributions to civil rights that might have well inspired her own.

In 1960, Bessie joined the Pan Africanist Congress. Because it was a banned organization under the South African apartheid government, she was arrested. Although charges were later dropped, this event is said to have been the driving force behind her first suicide attempt.

Returning to Cape Town, she founded and published The Citizen newspaper. Bessie established a close association with District Six and the coloured community. She mixed with prominent figures that would influence her life and writing, including jazz musician Abdullah Ibrahim (then known as Dollar Brand).

The apartheid government would later gain control of The Citizen and other newspapers in an operation dubbed Operation Muldergate. Attempting to purchase these magazines, the government believed they could have a stronger hold on public opinion – and directly counteract the anti-apartheid motions of authors like Bessie Head.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Marriage, Cape Town to Pretoria, and early worksBessie met Harold Head in 1961, and they married six weeks later. Their marriage was an unhappy one from the start, and she soon began to seek any escape from her troubled and depressed home life. Her son was later diagnosed with fetal alcohol syndrome — a consequence of her stressed, erratic lifestyle during her pregnancy.

Some of Bessie’s later poems, written around 1961–1962, were discovered in 1995. These were donated to the National English Literary Museum in Grahamstown, South Africa.

She finished writing her first novel, The Cardinals, in 1962. However, it was published only after her death. The Cardinals tells of a girl named Mouse, who is sold by her birth mother – and who later runs away from home after being abused by her stepfather. The book is one of her only novels set in South Africa, and takes place in Cape Town during the 1950s.

Bessie left Cape Town at the end of 1963 and moved into her mother-in-law’s house in Atteridgeville, Pretoria. She described the circumstances of her marriage while living in her mother-in-law’s house and attempting to gain a teaching job as being “at the edge of despair and terror.” She also tried to get a teaching job in Uganda; however, her passport was refused, possibly due to her earlier involvement with the PAC.

Bessie in Serowe, Botswana

Bessie’s marriage ended in 1964. She left for Serowe with her son to start a new life in Botswana on a one-way exit permit. She returned to her teaching background at Tshekedi Memorial School.

Starting a new life in Serowe wasn’t easy, and due to her political affiliations, it took fifteen years to gain legal citizenship in Botswana. Her teaching job only lasted a year and a half. In a letter, she stated that a lack of respect for women in the workplace was the reason for her dismissal.

Her letters also reveal that she often asked friends for money or extensions on loans that they had given her. As a thanks to some, she reportedly enclosed some of her original writing within these letters. She was a prolific letter writer, and some of her letter collections have received as much attention as her other writings. – including her writings to South African poet Patrick Cullinan and his wife, Wendy.

Her letters have been studied more in recent years. A study by Annie Gagiano (Writing a Life in Epistolic Form: Bessie Head’s Letters) points to her early childhood letters, where she “takes on the role of social commentator” that she would occupy for life.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Bessie Head’s Major Literary WorksWhen Rain Clouds Gather (1968) tells the story of a political refugee named Makhaya, who flees to Botswana and settles in a rural town called Golema Mmidi. Makhaya comes to meet the English agricultural expert Gilbert Balfour, who joins forces to introduce new technology and farming techniques to the village.

Around 1969, Bessie began to experience symptoms of depression and schizophrenia, which led to her hospitalization in Lobatse Mental Hospital. After this episode, she wrote A Question of Power (1973). Bessie wrote in a letter to her agent that this book had drawn from her mental health and anxiety at the time.

A Question of Power is one of Bessie Head’s best-known works and is considered semi-autobiographical. The main character, named Elizabeth, leaves South Africa to live in Botswana. Many of her experiences seem to draw directly from Bessie’s life.

Maru (1971) tells the story of historical racial discrimination between the Setswana and San peoples. Head speaks from the perspective of Margaret Cadmore, a member of the San/Basarwa people, and shares her experiences as teacher in the village of Dilepe – where her people face brutal discrimination.

In 1977, she published the short story collection The Collector of Treasures. Serowe: Village of the Rain Wind (1981) was a personal perspective on Botswana – the place she set most of her stories, and where she felt most at home. Bessie Head’s last novel, A Bewitched Crossroad (1984) was set in Botswana, spanning from 1800 to 1895, and explored the Sebina clan.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Bessie lived with her son until her death from hepatitis in April 1986. She passed away at Sekgoma Memorial Hospital in Serowe.

Much of her acclaim arrived later in life, and today she is considered a literary legend in both Botswana and Southern Africa. Bessie was awarded the national Order of Ikhamanga posthumously in 2003 for her contribution to literature. In 2007, the Bessie Head Heritage Trust and Bessie Head Literature Awards were established to further her legacy.

In 2013, the Bessie Head Heritage Trust recommended that the Serowe library be named after her, as she had been an active member of the library during her lifetime. Her papers are archived at the Khama III Memorial Museum in Serowe.

. . . . . . . . . .

Further reading and sources SA History Online: Bessie Amelia Head Britannica: Bessie Emery Head The South African Presidency: Bessie Head The South African Literary Awards: Bessie Head Botswana Tourism: Explore Serowe

Contributed by Alex Coyne, journalist, author, and proofreader. He has written for a variety of publications and websites, with a radar calibrated for gothic, gonzo and the weird. His features, posts, articles and interviews have been published in People Magazine, ATKV Taalgenoot, LitNet, The Citizen, Funds for Writers, and The South African, among other publications.

More by Alex Coyne on this site

Nadine Gordimer, South African Author and Activist 8 Essential Novels by South African Author Nadine Gordimer Jeanne Goosen, Author of We’re Not All Like That 6 Notable South African Women Poets The Banning of Nadine Gordimer’s Anti-Apartheid Novels Olive Schreiner, Author of The Story of a South African Farm 10 Unforgettable Books by South African Women Writers Ingrid Jonker, South African Poet and Anti-Apartheid ActivistThe post Bessie Head: Botswana and South Africa’s Shared Literary Great appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 23, 2025

20th-Century Women Novelists Worth Rediscovering

So many books, so little time … especially since so many new and noteworthy books by women are published each year. But let’s not forget those who came before. There are a plethora of 20th-century women novelists whose works deserve to be rediscovered and read; here are a dozen.

Women writers’ books that have endured as classics in and out of the classroom include To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee and The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck; the ever-respected Virginia Woolf; and the beloved Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, and Louisa May Alcott.

On the flip side is a treasure trove of women authors who were widely read in their lifetimes, yet have been somewhat (or nearly completely) forgotten — and shouldn’t be! Here is a baker’s dozen of authors worthy of rediscovery. You may also enjoy Bustle’s list of overlooked classic novels by women.

. . . . . . . . . .

Vera Caspary

Vera Caspary (1899– 1987) was a remarkably prolific American novelist, screenwriter, and playwright. Over the course of her long career, she became known as a writer of crime fiction and thrillers, though she created works in other genres.

Many of Caspary’s works featured young, forward-thinking women (then called “career girls”) who fought for female autonomy and equality, and refused male protection.

With nearly two dozen novels published, the best known remains Laura (1943), she also wrote long short stories and novellas, not to mention numerous screenplays for Hollywood films, some based on her own works. The Blue Gardenia, Fritz Lang’s 1953 classic noir film, is based on her novella, The Gardenia (1952). Yet Vera Caspary’s books are exceedingly hard to come by, other than these listed below:

Laura (1943) Bedelia (1945) The Man Who Loved His Wife (1966). . . . . . . . . .

Jessie Redmon FausetJessie Redmon Fauset (1882 – 1961) was an American editor, poet, essayist, and novelist who was deeply involved with the Harlem Renaissance literary movement.

Jessie Fauset was known as one of the “midwives” of the movement, as someone who encouraged and supported other talents. She was especially noted for her work as the literary editor of The Crisis, NAACP’s journal, in the Harlem Renaissance era. In that capacity, she discovered and nurtured several major Black literary figures.

She also wrote four well-regarded novels and numerous short stories and essays; she was an accomplished poet as well. She wrote four novels about race and class, all of which are a century old, give or take a few years, are still wonderful reads today:

There Is Confusion (1924) Plum Bun: A Novel Without a Moral (1928)The Chinaberry Tree (1931)Comedy, American Style (1933)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Edna Ferber

Edna Ferber (1885 – 1968), American novelist and playwright, was one of the most successful mid-20th-century authors — —primarily the 1920s through the early 1950s, with earning power to prove it. Some of her sprawling novels captured a slice of Americana, and several became famous films and/or stage plays, notably Saratoga Trunk, Cimarron, Giant, and Show Boat.

Ferber’s reputation was cemented with So Big (1924), a surprise (to her) bestselling novel that was awarded the 1924 Pulitzer Prize for fiction (even more of a surprise). Popular writers rarely enjoy critical acclaim, but in her case, the critics were generally kind, even as her subsequent work became less literary and more mainstream.

This is but a small portion of Ferber’s prolific output, and a good place to start with her novel:

So Big (1924) Show Boat (1926) Cimarron (1929) Giant (1952). . . . . . . . . . .

Rumer GoddenRumer Godden (1907 – 1998), the British-born novelist and memoirist. was raised mainly in India at the height of colonial rule. A mid-20th-century favorite whose novels melded the commercial and literary; nine of them became films. One of several memoirs of her dramatic life, and arguably the best known, is A House With Four Rooms.

In 1939, her first novel, Black Narcissus, was published to immediate acclaim and became a bestseller. The story is set in a cloister high in the Himalayas. A group of nuns in a convent in northern India is the backdrop for a story of cultural conflict and obsessive love.

Black Narcissus set the stage for a succession of novels that are defined by vivid settings and realistic characters in masterful storytelling that was sometimes described by contemporary reviewers as “deceptively simple” and “subtle magic.” Here’s where to start with Rumer Godden:

Black Narcissus (1939) The River (1946) In This House of Brede (1969) The Peacock Spring (1975). . . . . . . . . . .

Laura Z. HobsonLaura Z. Hobson (1900 – 1986) is an author whose name has been eclipsed by that of her best-known novel, Gentleman’s Agreement. The film version went on to win multiple Academy Awards. Laura wrote a number of other fascinating and readable novels that have fallen into obscurity.

Before she became a full-time novelist with the 1947 publication of Gentleman’s Agreement, she had been a successful writer of advertising and promotional copy on the staff of Luce publications, where she wrote for Time, Life, and Fortune.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Ann Petry

Ann Petry (1908 – 1997) was the first Black American woman to produce a book (The Street, 1946) whose sales topped one million. At its peak, this novel had sold 1.5 million copies.

Ann trained as a pharmacist so that she could follow in her father’s footsteps. But her heart was with reading and writing.She was particularly taken with Louisa May Alcott’s fictional heroine Jo March as a role model for her writerly aspirations.

When The Street was published in 1946 it became an overnight sensation. The New York Times called it “a skillfully written and forceful first novel.’’ Its significance was as a frank explored Black women’s experience through the intersection of race, gender, and class. It was reissued in a new edition in 1992 along with her other novels and a collection of short stories, all of which depict slices of Black life in 20th-century America:

The Street (1946)Country Place (1947)The Narrows (1953)Miss Muriel and Other Stories (1971)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Dawn Powell

Dawn Powell (1896 – 1965) wrote prolifically throughout her life, producing novels, short stories, poetry, and plays. She is sometimes considered a “writer’s writer,” though sadly, nearly all of her work was out of print by the time she died. She didn’t gain much notoriety — for better or worse — during her lifetime, but many of her works have been rediscovered and rereleased, much to the joy of devoted fans and new readers alike.

Born in Mount Gilead, Ohio, Powell started her life in a small American town, a setting that she would often use in her early writings. Her novels were replete with social satire and laced with wit. Here are four of her fifteen novels:

Angels on Toast (1940); reissued in 1956 as A Man’s AffairA Time to Be Born (1942)My Home Is Far Away (1944)The Locusts Have No King (1948)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Barbara Pym

Barbara Pym (1913 – 1980) was a British author whose novels explored manners and morals in village life. The following selection of quotes from Excellent Women and other novels by Barbara Pym demonstrate her sense of irony and subtle, understated wit.

Though most her books’ action, such as it is, is set in small town England locales, her stories convey universal truths about human foibles. Pym published thirteen novels in her lifetime, and four posthumously. Pym was often compared to Jane Austen for her comedies of manner.She has been called Britain’s “other Jane Austen” or “new Jane Austen.”

Her baker’s dozen of novels, most published in her lifetime and a few posthumously make up the Barbara Pym canon, with many devotees citing Excellent Women as their entry-point or overall favorite. Here the first four of a baker’s dozen of her novels:

Some Tame Gazelle (1950) Excellent Women (1952)Jane and Prudence (1953)Less than Angels (1955). . . . . . . . . . .

Jean RhysJean Rhys (1890 – 1979) is best remembered for Wide Sargasso Sea, (1966), a prequel and post-colonial response to Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. This imagining of how “the madwoman in the attic” came to be is her most remarkable and enduring work of fiction.

Wide Sargasso Sea was published when Rhys was 76, and revived her flagging literary career. Central to its plot is its imaginative presentation of Rochester’s Creole wife Antoinette’s descent into madness. She becomes Bertha, Rochester’s mad wife. You’ll never look at that character in the same way if you re-read Jane Eyre! That said, it works well as a standalone novel.

Rhys’s Caribbean roots figured into her 1934 novelVoyage in the Darkand shorter fiction such as The Day They Burned the Books. In this sampling of four of her novels, you’ll see that there was a very long gap beforeWide Sargasso Sea, her last novel, was published.

After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie, 1931 Voyage in the Dark , 1934Good Morning, Midnight, 1939 Wide Sargasso Sea , 1966. . . . . . . . . . .

May SartonMay Sarton (1912 – 1995), might be better remembered for her memoir series that began with Plant Dreaming Deep, but she was also a pioneer of modern queer fiction. Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing was pretty radical for 1965 and the lesbian novel, The Education of Harriet Hatfield , was still considered ahead of its time in 1989.

Despite coming out as a lesbian during a time when very few others did, the popularity of her work wasn’t affected. In fact, it brought high recognition and respect, later to become staples in women’s studies classes. She preferred, however, for her work to be appreciated for its exploration of what is universal in love, rather than as lesbian literature.

May Sarton was also an accomplished and widely published poet. Here’s a sampling of her best-known novels:

Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing (1965) Anger (1982) The Magnificent Spinster (1985) The Education of Harriet Hatfield (1989). . . . . . . . . . .

Margery SharpMargery Sharp (1905 – 1991), a popular British author in her lifetime, wrote in the comic novel genre, the best known of which is Cluny Brown.She was also known for The Rescuers series for children, two of which were adapted into animated Disney films.

Though most of her works were on the lighthearted side, the devastating bombing of London featured in Britannia Mews. She continued to produce works that are generally considered comic novels, but she was a keen observer of human nature and foibles and captured the details of daily life of the World War II years.

Cluny Brown (1944)Britannia Mews (1946) The Eye of Love (1957)Something Light (1960). . . . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth von ArnimElizabeth von Arnim (1866 – 1941), an Australian-born novelist, launched her writing career with Elizabeth and her German Garden (1898). Little is known about this mysterious author, but her tales of unhappy marriages told with a dry wit are still a treat to read.

Vera (1922) isn’t Elizabeth’s best known work, but is considered her finest novel from a literary standpoint. Like some of her other works, it is semi-autobiographical and draws upon her ill-fated marriage with Earl Russell.

Following closely upon its heels was The Enchanted April (1922). One of von Arnim’s most commercially successful works, it was charming and lighthearted, almost the opposite of Vera from the perspective of mood. The former was adapted to film in 1991, titled Enchanted April.

The Pastor’s Wife (1914) Vera (1922) The Enchanted April (1922) Mr. Skeffington (1940)The post 20th-Century Women Novelists Worth Rediscovering appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 22, 2025

Goodnight Moon: On Falling Asleep in Order to Wake Up

This essay is excerpted from “An Unreasonably Deep Analysis of Goodnight Moon: On Finding (or Creating) Meaning in Dreams” by Eponynonymous.

My daughter used to fight sleep like grim death. Every night as she was dozing off, she would suddenly recoil, bouncing back from that hypnagogic state with flailing arms and banshee screams. It was as if she saw what lay on the other side of sleep and what she saw was death. Oblivion. I don’t think the analogy is too dramatic.

To a baby, bedtime really is a little death. Her sense of self is tenuous, her dreams not so easily distinguished from reality, and her mind freighted with new experiences that some psychologists say have the effect of slowing time. As it was, my daughter came to recognize those grim portents of sleep, and one of them was Goodnight Moon.

It’s a wonder Margaret Wise Brown’s masterpiece isn’t celebrated as a work of existentialist horror, one which plays on the belief that things exist regardless of our awareness of them. Combs, chairs, bowls full of mush—these things are lifeless, objective, impervious to introspection, and wholly beyond the mind which observes them.

We believe the world is made of “things,” and those who experience them are merely privileged with the senses to do so. Even the act of experience is understood to be an object of complex neurosensory activity in the brain, and subjectivity is only a particularly convincing illusion of emergent neural phenomena. Our consensus model of reality, as it were, speaks in the passive voice: object begets subject.

. . . . . . . . .

Margaret Wise Brown, photo by Consuelo Kanaga

courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . .

Not so the voice in Goodnight Moon, whose steady itemization of stars and balloons and little toy houses serve like rosary beads for the flighty spirit-voice, whose accruing mantra of “goodnight” foretells the end of all experience, even as it clings to the objects that define it.

Do these things persist when we close the book? What about when we close our eyes? To crib a famous thought experiment, if a quiet old lady is whispering hush and there’s nobody around to hear it, does she even make a sound? I think about this while rocking my daughter to sleep.