Nava Atlas's Blog, page 8

October 10, 2024

The Mother of Social Science: The Works of Harriet Martineau

As a social scientist, Harriet Martineau (1802–1876) published at least fifteen book titles, some of them spanning several volumes.

As a journalist, Martineau made a living by writing for mid-19th century journals and newspapers, encouraging intellectual and social debates across her native England and around the world.

As a writer, she engaged readers of novels, travelogues, biographies, and much more – she probably would have a book in every section of the library if her work were still in print today.

How did Martineau come to be known as the mother of social science, and even more curiously, how did she manage to support herself with the writing of her philosophic and social opinions and observations in a time when the role of women was assigned to the household sphere?

It was an age when, according to Regan Penaluna in How to Think Like a Woman, women were allowed, even encouraged, to work as writers as long as they confined themselves to novels, reviews, translations, and home and hearth. They were encouraged to leave the heavy ideas to male journalists.

How did such a prolific, insightful, and relevant writer become nearly obscure, her work lost in the shadow of the acknowledged great thinkers such as Rousseau, Kant, and her contemporary social scientists?

Harriet Martineau was born in 1802, the sixth of eight children born to textile manufacturer Thomas Martineau and his wife, Elizabeth Rankin Martineau. Harriet’s father’s work provided a middle-class upbringing for the family, but she suffered from things a comfortable lifestyle could not cure.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Harriet Martineau

. . . . . . . . . .

She endured debilitating fears and panic attacks, chronic stomach ailments, an increasing hearing loss, and had no sense of smell. She wrote in her autobiography:

“Sometimes, I was panic-struck at the head of the stairs, and was sure I could never get down; and I could never cross the yard into the garden without flying and panting, and fearing to look behind, because a wild beast was after me. The starlight sky was the worst; it was always coming down to stifle and crush me, and rest upon my head.”

Martineau also makes mention in her autobiography, of her “daily pain from chronic inflammation of the stomach.” And that “my education was considerably advanced before my hearing began to go.” Also, because she suffered with having no sense of smell, her sense of taste was “exceedingly imperfect.”

She was largely educated at the family’s home in Norwich. Despite her painful stomach discomforts, crippling fears (which she never told anyone about), and her increasing hearing loss which would render her almost totally deaf by the age of twenty — Martineau was able to attend a private school for two years. She also spent a year in a boarding school for girls, where her parents felt the country air would benefit her health.

Women were not allowed to study at a university level, but Martineau continued the self-study she’d practiced since childhood; reading books, asking questions, writing arguments and essays in search of answers, in all subjects she could think of, including those normally taught only to males.

First published writings

Having grown up with strong Unitarian influences, Martineau’s natural first writing endeavor was a submission to the Monthly Respository, a unitarian magazine. Under the pen name of “V. of Norwich,” her first article was published and, along with the praise from her esteemed older brother, swelled her heart with pride at becoming an “authoress.”

She was nineteen years old, and this success sent her back to the empty pages of her notebooks, excited to fill each page with her thoughts. She did not spend a lot of time and effort in revising her work, committing herself to a single copy, as “distinctness and precision must be lost if alterations were made in a different state of mind from that which suggested the first utterance.”

Tragedy struck when Martineau’s older brother, her biggest supporter, died of consumption (tuberculosis). Soon after, her father’s business began to flounder, which landed the family in tenuous financial straits. Her father died in 1826, and though the manufacturing business provided a livable income for the Martineau mother and daughters, its failure in 1829 sent them scrambling to maintain their home.

The industrious Martineau women rose from tragedy like worker bees to a vacant hive, and Harriet was the most tireless of all. She produced needlework by day and did her studying and writing at night. Her spirit soared under these circumstances of seemingly crushing hours and responsibility. In her autobiography, she wrote that the exertion of all her faculties made her very happy and gave her a “deep-felt sense of progress and expansion.”

Illustrations of Political Economy

Spending all those late nights writing into the wee hours paid off when Martineau won £45 in an essay contest sponsored by the Unitarians. She entered and won all three categories: arguments of Unitarianism to the notice of Catholics, Jews, and Mohammedans. Such success spurred her to write her famous series Illustrations of Political Economy, which was itself a great feat in publishing.

The presses at the time (1832) were concerned with a couple of pretty hot political topics — first, that the reform bill was causing much raucousness among citizens, clergy, and politicians alike, and second, that cholera was becoming like a plague from the Middle Ages, decimating the population at an alarming rate.

It was no small victory when Martineau negotiated an agreement with a publisher which stipulated that once 500 subscribers were obtained, the book would go to print. Her success was tremendous with Illustrations of Political Economy, the fictionalized tales illustrating the concept of the new political science.

Subscribers signed up in droves, and the publisher wrote to ask her to make any needed corrections, for Illustrations of Political Economy was going to be sent for a second printing of 5,000 copies. Letters poured in from readers who wanted her to include their hobby or work in the next installment in the series. She began receiving offers from many publishers who wanted to be a part of her future work.

Illustrations of Political Economy grew into a 9-volume series of short stories intended to illustrate the social and political activities taking place in a free market economy. Martineau published these volumes between 1832 and 1834, hoping to make political economy an accessible study for readers of all stripes.

The series is a marriage of politics, economics, social structure, and literature that heralds the birth of Martineau as a philosopher and a much sought after social/political commentator, which is evidenced in the 1836 publication of Miscellanies.

Martineau moved herself and her mother to London in order to better meet the demands of the incoming requests for her increasingly popular work, but almost immediately her desire for writing her observations took her to the United States. From 1834 to 1836 she toured the U.S. for Society in America (1837 ) and Retrospect of Western Travel (1838) and How to Observe Morals and Manners (also 1838) was published. The latter is considered the first systematic methodological writing in sociology.

Persevering through poor health

Since childhood, Martineau’s stomach pains were chronic, and she learned to live with the ailment as best she could. But from the time she arrived home from the United States until 1842, her pain was such that she stayed on her couch, desperately hoping the doctor could find a cure.

During this sick time, she wrote a collection of endearing whimsical children’s stories including The Crofton Boys, The Peasant and the Prince, The Settlers at Home, and Feats on the Fiord.

Although she was under the care of some of the best doctors available, it was believed that her condition would not improve, and Martineau accepted that she would never get any better. When her brother suggested that she give mesmerism a try, Martineau agreed, having run the gamut of local doctors and all other remedies.

Mesmerists were, in many circles, considered quacks, but even today some of their techniques using magnetism and hypnosis are used in the treatment of modern ailments. After a successful treatment with magnetism, she rose from her sick bed and wrote:

“For my part, if any friend of mine had been lying in a suffering and hopeless state for nearly six years, and if she had fancied she might get well by standing on her head instead of her heels, or reciting charms, or bestriding a broomstick, I should have helped her to try; and thus was I aided by some of my family and by a further sympathy in others, but two or three of them were induced to regard my experiment and recovery as an unpardonable offence, and by them I never was pardoned.” (Autobiography, Volume 2)

A fevered pitch of writing and translationUpon healing from her illness, Martineau moved to the countryside, where her writing took on a fevered pitch, as if making up for lost time (though her work only slowed down during her illness and she never did fully stop writing). After publishing several popular books and articles, she translated Auguste Comte’s famous social work, and titled it The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte, Freely Translated and Condensed, 2 volumes, (1853).

Her translation won her great esteem, even from Compte himself, and made a significant contribution to the scholarly conversation on positivism in Britain. Having often been referred to as the Father of Social Science, Martineau’s translation of Comte’s work, coupled with her own social commentary, earned her the title of Mother of Social Science.

For the next twenty-three years, Martineau worked her land, kept her house, and published more books, writing her thoughts and observations up to the very day she died and amassing quite an extensive bibliography. In part:

1832–1834. Illustrations of Political Economy. 25 nos. in 6 vols1836. Miscellanies. 2 vols.1837. Society in America. 3 vols. London: Saunders & Otley. Abridged ed. by Seymour Martin Lipset1838. Retrospect of Western Travel. 2 vols.1838. How to Observe Morals and Manners.1839. Deerbrook. A novel1840 The Hour and the Man (a novel)1841 The Playfellow. (a series of children’s stories)1844. Life in the Sick-Room. 1848. Eastern Life, Present and Past1859. England and Her Soldiers1861. Health, Husbandry, and Handicraft1877. Harriet Martineau’s Autobiography, edited by Maria Weston Chapman. 2 vols.1983. Harriet Martineau’s Letters to Fanny Wedgewood, edited by Elisabeth S. Arbuckle(In addition, more than 1,500 newspaper columns, and several magazine articles. Not listed)

Co-wrote/translated:

Atkinson, Henry George, and Harriet Martineau. 1851.Letters on the Laws of Man’s Nature and DevelopmentComte, Auguste. The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte,

translated and condensed by Harriet Martineau. 1853 Harriet Martineau’s legacy

Martineau wrote about such topics as Unitarianism, abolitionism, feminism, disability, social science, atheism, and more. She was a biographer and critic who spared nothing from the printing press as she wrote about education, history, husbandry, legislation, manufacturing, mesmerism, occupational health, philosophy, political economy, religion, slavery, and travel.

Her most popular work in the United States today is Society in America, an exploration of the political economy of America with special interest in the slavery of the South. After a biographical introduction detailing Martineau’s travels and social interactions (unencumbered by her ear trumpet), page 3 states,

“The United States have indeed been useful in proving these two things, before held impossible; the finding of a true theory of government, by reasoning from the principles of human nature, as well as from the experience of governments; and the capacity of mankind for self-government.”

After that assent, the rest of the book measures and probes the prisons, schools, factories, plantations, farms, tribal establishments, and literary and scientific institutions, from north to south and east to west of the United States in order to find if life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness were actively apparent among everyone in equal measure.

Finding this not to be the case, Martineau aligned herself with the abolitionist movement. She sold embroidery to donate money to abolition and worked for the the Anti-Slavery Standard until the end of the Civil War. It was in the United States, too, where Martineau was further inspired to reveal gender inequality and its effects on society, championing women’s suffrage.

In 1846 Martineau toured Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, focusing her analytical eye on religion and customs. Her later writings reflect that she became an atheist during this time.

One of Martineau’s most downloaded works on Project Gutenberg is Life in the Sick-room: Essays. In this work, Martineau reaches out to encourage others: “We know and feel, to the very centre of our souls, that there is no hurry, no crushing, no devastation attending Divine processes.” (Dedication).

Harriet Martineau’s vast compilation of work, opinions ranging from politics, to philosophy, to pain, was, and still is, sought after reading fodder among many social scientists. We might not find Martineau’s work among the scholars while browsing the philosophy section at the bookstore, but some of her books can be found at online books stores and her many of her titles have been made into e-books as well.

It is indeed is a glaring slight that her work is not readily found in the library stacks among the great thinkers, but its digital availability can be seen as a social redemption of sorts. I’m sure we have the social scientists to thank for that.

Contributed by Tami Richards, a history enthusiast and freelance writer living in the Pacific Northwest. More of her work can be found here.

Further reading and sourcesHarriet Martineau’s Autobiography, Volume 1, 1855Penaluna, Regan. How to Think Like a Woman, Grove Press, 2024Harriet Martineau on Project GutenbergInternetarchive.org, Harriet Martineau,by Miller, Florence Fenwick Miller, 1887Openlibrary.orgThe post The Mother of Social Science: The Works of Harriet Martineau appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 1, 2024

Five women translators to celebrate on International Translation Day

International Translation Day falls on September 30 each year, but translators should be celebrated year round for what they contribute to how literature becomes a common thread between cultures.

Here are five women translators of the past whose work was groundbreaking, contributing to gender equality, education for all, abolitionism and scientific knowledge across borders and languages.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

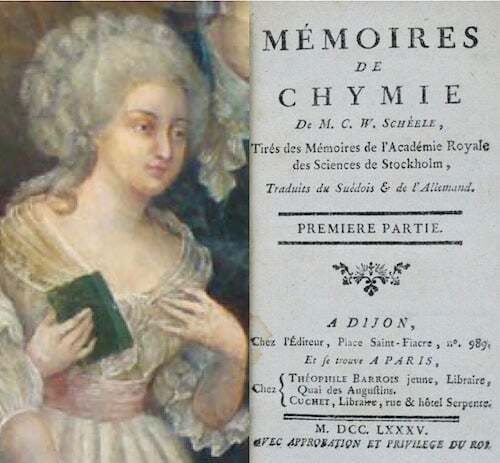

Claudine Picardet,chemist and scientific translator

Claudine Picardet (1735–1820) was a French chemist, mineralogist and meteorologist living in Dijon, a town in eastern France. She was the only woman at the Dijon Academy, and the only scientist who was proficient in five foreign languages (Latin, English, Italian, German, Swedish).

Claudine decided to translate a number of books and articles into French that were written by leading scientists of her time, for the benefit of her colleagues.

She translated three books and dozens of scientific papers originally written in Swedish (works by Carl Wilhelm Scheele and Torbern Bergman), in English (works by John Hill, Richard Kirwan and William Fordyce), in German (works by Johann Christian Wiegleb, Johann Friedrich Westrumb, Johann Carl Friedrich Meyer and Martin Heinrich Klaproth) and in Italian (works by Marsilio Landriani).

Claudine Picardet’s translations were essential for the dissemination of scientific knowledge during the Chemical Revolution, a movement led by French chemist Antoine Lavoisier, often called the Father of modern chemistry.

She also hosted renowned scientific and literary salons in Dijon and in Paris, where she moved later on, and actively participated in the collection of meteorological data.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Sarah Austin, tireless advocateof public education for all

As a child, Sarah Austin (1793–1867) studied Latin, French, German and Italian in her native England. After marrying legal philosopher John Austin in 1819, she became a translator and editor, and corresponded extensively with many writers. The couple moved from London to Bonn, Germany, in 1827, living largely on Sarah’s income.

Sara translated into English a few works written by her German and French contemporaries, for example Characteristics of Goethe from the German of Falk, von Müller, etc., with notes, original and translated, illustrative of German literature (in 1833), as well as books by German philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Carové (in 1834), German historian Leopold von Ranke (in 1840) and French historian François Guizot (in 1850).

One of her translations was the Report on the State of Public Instruction in Prussia, written in 1832 by French philosopher Victor Cousin for the French Minister of Public Education.

In the preface to her translation (published in 1834), she personally pleaded for the cause of public education. She also advocated for a national system of education in England in a pamphlet published in 1839 in the Foreign Quarterly Review.

She regularly stood for her intellectual rights as a translator, writing that “It has been my invariable practice, as soon as I have engaged to translate a work, to write to the author of it, announcing my intention, and adding that if he has any correction, omission, or addition to make, he might depend on my paying attention to his suggestions” (in “Sarah Austin,” Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 2, 1885).

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Clémence Royer (1830-1902),translator of Charles Darwin’s seminal book

Clémence Royer (1830–1902) was a self-taught French scholar who undertook the major task of translating English naturalist Charles Darwin’s seminal book On the Origin of Species (first published in 1859). His concept of evolutionary adaptation through natural selection was attracting widespread interest outside Britain, and Darwin was eager to have his book translated into French.

In the first French edition (1862), based on the third English edition, Clémence Royer went beyond her role as a translator, with a 60-page preface expressing her own views and many detailed explanatory footnotes.

Her own views had more in common with French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s ideas than with Darwin’s ideas. After reading her translation, Darwin was unhappy with her preface and footnotes and, according to him, her lack of knowledge in natural history.

Darwin requested the correction of some errors and inaccuracies in the second French edition (1866). The third French edition (1873) was produced without Darwin’s consent, with a second preface that also made Darwin unhappy, and an appendix that forgot the additions to the fourth and fifth English editions and only included the additions to the sixth English edition (published in 1872).

After three French editions (1862, 1866, 1873) published by Guillaumin, the fourth French edition (1882) was published by Flammarion the year of Darwin’s death, and stayed popular until 1932. Her controversial translation brought fame to Clémence Royer, who extensively wrote and lectured on philosophy, feminism and science, including on Darwinism.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Mary Louise Booth, translator of major booksby anti-slavery advocates

Born in Millville (now Yaphank) in the State of New York, Mary Louise Booth (1831–1899) was of French descent on her mother’s side.

After moving to New York City at the age of 18, she wrote many pieces for various newspapers and magazines, and translated around 40 books from French into English, including works by writers Joseph Méry and Edmond François Valentin About, and by philosopher Victor Cousin.

She assisted Orlando Williams Wight, a fellow American translator, in producing a series of translations of French classics. She also wrote a History of the City of New York (1859) that became a bestseller.

When the American Civil War started in 1861, she translated French anti-slavery advocate Agénor de Gasparin’s book Uprising of a Great People (just published in France) in a very short time by working twenty hours a day for one week. Her translation was published in a fortnight by American publisher Scribner’s and widely distributed.

Then she translated Gasparin’s America before Europe (translation published in 1861), as well as books by other anti-slavery advocates, including Pierre-Suzanne-Augustin Cochin’s Results of Emancipation and Results of Slavery (1862) and Édouard René de Laboulaye’s Paris in America (1865).

She received praise and encouragement from President Abraham Lincoln, Senator Charles Sumner and other statesmen for her invaluable contribution towards the abolition of slavery.

She also translated other books by the same authors, including Gasparin’s religious works (written with his wife) and Laboulaye’s Fairy Book, as well as Fairy Tales by educator Jean Macé, History of France by historian Henri Martin, and Provincial Letters by philosopher Blaise Pascal.

She became the first editor-in-chief of the newly created magazine Harper’s Bazaar from 1867 until her death in 1899. Under her leadership, the magazine steadily increased its circulation and influence to become a household name. After struggling financially for decades as a writer and translator, she finally earned a larger salary than any woman in America.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Alix Strachey,translator of Freud’s complete works

Alix Strachey (1892–1973), an American-born English psychoanalyst, spent her whole life working alongside her husband, James Strachey, who was a fellow English psychoanalyst. Shortly after getting married in 1920, they left for Vienna, Austria, and spent two years studying psychology with famed Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud.

At Freud’s request, they first translated some of his articles from German into English. Then they worked tirelessly for many years (from 1953 to 1966) to translate his complete works (written between 1886 to 1939), in collaboration with Anna Freud, Freud’s youngest daughter, and with the help of English musicologist and translator Alan Tyson.

The 24-volume translation was published in 1953-74 by Hogarth Press in London under the title The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, with James Strachey as its editor. Also known to scholars as The Standard Edition (SE), it included introductions to Freud’s various works and extensive bibliographical and historical footnotes, It quickly became the reference edition of Freud’s works in English, and a reference work for translations into other languages.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

More women translators are celebrated in the ebook Some Women Translators of the Past (July 2024)

Also by Marie Lebert: 10 Lost Ladies of Literary Translation

Article written by Marie Lebert (edited by Nava Atlas). Marie Lebert is a French translator and librarian who has worked for international organizations and global projects in several countries. She is currently based in Australia. She writes about translation and translators – past and present — with a focus on women translators.

Women translators have been forgotten for too long before being recently acknowledged in Wikipedia thanks to its many contributors. Marie holds a PhD in linguistics (digital publishing) from the Sorbonne, Paris. Her articles, essays and ebooks are available online in English, French and Spanish at Marie Lebert.

The post Five women translators to celebrate on International Translation Day appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 30, 2024

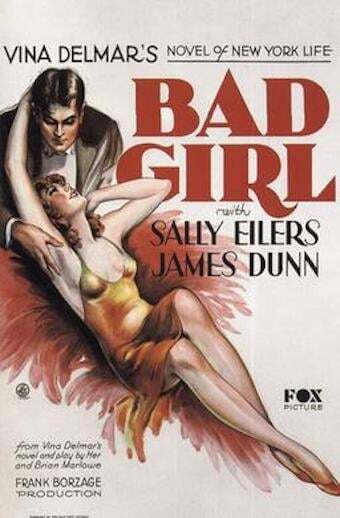

Bad Girl by Viña Delmar, a 1928 Novel That Was “Banned in Boston”

In the 1920s, urban American women experimented with sexual freedom more openly than ever. Popular novels by writers — male and female — held up a mirror to the times. Despite its provocative title, the forgotten bestselling 1928 novel, Bad Girl by Viña Delmar, wasn’t one of them.

Dorothy, or “Dot,” as she’s familiarly called, has one instance of premarital sex, marries the guy (who’s not a bad sort, but not very bright), and after a respectable period of time, becomes pregnant. The novel is then preoccupied with her pregnancy and childbirth. The cover of a later edition, at right, sensationalizes the contents, as was typical of pulp novels.

There’s nothing scandalous about this middling novel, but the realities of a young wife’s pregnancy and her experiences in a birthing hospital were enough to catch the eyes of The New England Watch and Ward Society.

This New England-based organization whose mission was censorship of books and the performing arts was most active from the late nineteenth century through the 1920s.

For the most part, publishers welcomed a book being “banned in Boston,” as this kind of controversy boosted sales. Winning these censorship cases in court, however, really did mean that the books in question couldn’t be sold in Massachusetts under severe penalty of law.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Being banned in Boston drove Bad Girl onto national bestseller lists and helped make its 23-year-old author an overnight sensation. The 1931 pre- Hayes Code film adaptation received great reviews, making the most of its thin material and breathing new life into the novel’s notoriety just a few years later.

“Bad Girl is Popular” read the headline of a brief blurb that was syndicated to several newspapers in 1928:

Vina Delmar’s novel, “Bad Girl” which attracted so much attention before and after it was “banned in Boston,” has reached (so its publishers, Harcourt, Brace and Company announce) its seventh large printing, not including the 40,000 to the Literary Guild. During the last two weeks in has been reported to be the best selling novel in the country, supplanting, at least for the present, “The Bridge of San Luis Rey.”

Reviewers were, if not bowled over, generally kind to the novel and its young author. Following is a fairly typical review from the period, after which are two articles about its banning in Massachusetts.

. . . . . . . . . .

Another sensationalized cover of Bad Girl. See also —

Her First Time: Seduction and Loss of Innocence in 1920s Women’s Novels

. . . . . . . . . .

Bad Girl is a Poignant Transcript of LifeTulsa Daily World, Tulsa, Oklahoma, June 17, 1928: Viña Delmar has written a rough and honest tale of loving. Bad Girl by Viña Delmar has been so widely heralded as a precocious first novel that a cautious reader is to be pardoned if it has been catalogued among books that can wait. And yet caution, in this instance, is totally unnecessary.

A first novel it may be, but it is free from the taint of precocity, and from the blight of conscious straining for style. It is a spontaneous and honest piece of writing. It concerns the meeting, mating, and marriage. It depicts one year of married life of two young people from that strata whose constituents consider themselves educated and ready for life when the eighth grade is behind them.

Mrs. Delmar’s Dorothy is an eager, slim, pliable young thing exactly like all the other millions of lipsticked, bobbed, silk-stockinged young women whose bright eyes shone with life. Her Eddie is an unbelievably sensitive, consistently staunch youth, outwardly like all the other swaggering boys who seek and accept the challenge of bright eyes.

Eddie and Dorothy (often referred to as Dot) pick each other up on an excursion boat. For all the shield of their rude, self-protective banter they understand one another. They marry and have a child.

Dorothy and Eddie are real people. So is Edna, the strange girl who Dorothy’s brother loved, so far as he could love. And so are the sly-eyed, perfumed Maude, the noisy Sue, the kind, matter-of-fact doctors who took Dorothy through the hell of labor into the blessed haven of her motherhood.

Viña Delmar has written a poignant, moving story of honest thought and action. There’s no reticence in Bad Girl. Perhaps that’s why Boston banned it. But its frankness is that of reality, and is not offensive. The book takes its its title form Dot and Eddie’s prenuptial adventure, out of which she emerged panic-stricken an afraid, and Eddie came out of grim and purposeful.

There’s something intensely appealing about Eddie. He is sullen, he is rude, he is profane, but underneath this rough exterior is a man who is tender, wonderfully kind, oddly wistful, and ready to sacrifice anything for the little flame of a girl he married.

When Dot found out she was to have a baby, she trembled for fear that Eddie didn’t want it. She was ready to go any lengths if he didn’t. And Eddie, interpreting her fear as an aversion to the baby, thought that it was Dot who didn’t want it. He feigned disgust at the thought of a third member coming into the family. Love makes such strange tangles sometimes!

Anyone who could produce such a vital book as this one will go a long way. The reader feels that Viña Delmar knows what she’s writing about in this, her first book — that she has felt the pain and joy that color it. And knowing and feeling as she does, she was able to write about simple and elemental things.

Bad Girl isn’t, from any standpoint, an important book. But it is a true one, which makes it good.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Viña Delmar in 1928

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Springfield Daily Republican (Springfield, Massachusetts), May 4, 1928: Literary Guild selection novel by Viña Delmar, former actress, held by booksellers to be “Actionable” under Massachusetts. “Obscenity” ignores truth, says author.

Bad Girl, a novel that raised Vina Delmar to literary fame at the age of 23, has been banned from sale in Boston. Harcourt, Brace & Co.. the publishers. received notice today from the Boston Booksellers’ association that the book is “actionable.”

The association. by agreement with the district attorney. has the power to rule on the counters of its members any books which it believes violate the Massachusetts “obscenity” law.

When Miss Delmar was informed of the action. she said Boston ignores the truth. Propagation is evidently obscene, The Lord was less cautious in his personal contacts than the Boston book banners in their reading. They are witch burners, truth hiders, and killers of the seeds of sincerity.

Bad Girl, by being barred from Boston. now joins the company of Elmer Gantry, An American Tragedy, The Plastic Age, and other recent novels that have won praise elsewhere.

Bad Girl was selected by the Literary Guild as its book for the month of April. This made Miss Delmar. a former actress and writer of short stories. famous overnight. She contends that Bad Girl is true to the lives or the people in her neighborhood” and that she took all the characters from her acquaintances.

The heroine in the book was married at the age of seventeen and the story goes on with her married life until the first baby is born.

Boston Bans New Novel, Bad Girl; Editor Is Angry

The Dispatch (Moline, Illinois). May 12, 1928: Bad Girl. a new novel by Viña Delmar, has been banned in Boston, The Watch and Ward Society having disapproved it. The Boston Booksellers’ association has sent word to Harcourt. Brace & Co. of New York that they will not handle the book.

“The book has one pretty strong chapter in it,” said a leading Boston publisher, “and the Watch and Ward society, I’m frank to say, under Massachusetts statutes anyone who sold it could be prosecuted. We care neither to push out such books, nor to furnish our contemporaries over in New York with just much free advertising.

“We read the book, of course, before submitting it to the Watch and Ward society. The banning by the society didn’t cause even a ripple among us. Dare say we will sell plenty of books without adding this one to our stock.”

“The exploitation of ‘Banned in Boston’ or ‘puritan Boston’ gives any such book a certain boost in New York. I suppose. but the New York publishers are welcome to it.”

Silly, says editor

A letter from the Boston Booksellers’ association was received by Harcourt, Brace & Co. publishers. notifying them that Viña Delmar’s novel, Bad Girl was actionable. No other reason was given by the association for its refusal to handle the book in Boston.

The author of the book is twenty-three, a former usher, stenographer, and vaudeville actress. Its banning was termed an act of “a crazy bunch of madmen” by Harrison Smith, editor for Harcourt, Brace & Co.

“What’s the use?” he said. Asked if the prohibition from sale would be contested. “It’s incredible that the book should be thought obscene, even in Boston. A baby is born in it; can’t babies be born in books Boston reads?”

The theme of the novel—Mrs. Delmar’s first—is pregnancy. A Bronx stenographer, Dot, flirts with a “white Harlem” radio mechanic, Eddie. on board a steamer. They marry, and Dot, believing her husband does not want a baby, suffers in silence because she is pregnant, Eddie, too, thinking his wife dreads childbirth, suffers quietly. The birth, it’s hinted at the very end, will clear up these misunderstandings.

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Bad Girl by Viña Delmar

Full text on Internet Archive

Viña Delmar, Flapper Fiction, and Snappy Stories Magazine

The post Bad Girl by Viña Delmar, a 1928 Novel That Was “Banned in Boston” appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 7, 2024

Flora Thompson, Author of Lark Rise to Candleford

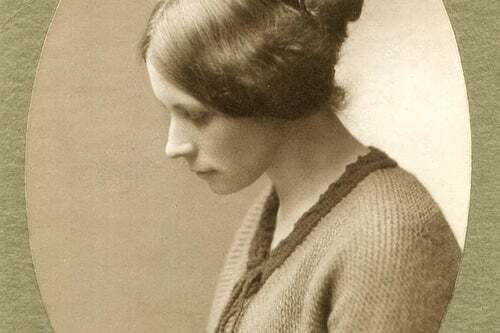

Flora Thompson (December 5, 1876 – May 21, 1947), was an English novelist and poet, best known for her semi-autobiographical trilogy Lark Rise to Candleford.

The commercial and critical success of the books — Lark Rise, Over to Candleford, and Candleford Green — is such that they have never been out of print, and were adapted by the BBC for a four-season series in 2008.

Early life: The origins of Candleford

Flora Jane Timms was born in the rural hamlet of Juniper Hill, near Brackley, Oxfordshire. Her father, Albert, was a stonemason, whose ambitions to become a sculptor had been thwarted by his drinking and gambling.

Flora later remembered him as “a terrible spendthrift … he never seemed to grasp the fact that he was responsible for our upbringing … He had all of the bad qualities of genius and a few of the good ones.”

Her mother, Emma, had gone into service at an early age and had worked as a nursemaid before she married Albert. She gave birth to ten children between 1875 and 1898, but only six survived beyond the age of three. Despite her challenging life, Emma was a talented storyteller and delighted in creating imaginary worlds for her children through songs, games, and stories.

When Flora was growing up, Juniper Hill was barely touched by the Industrial Revolution that was sweeping across England. It was still a place where farm laborers earned a subsistence wage, and where women still drew water from a communal well.

Later, in the first of her famous trilogy, Lark Rise, Flora described it as “bare, brown, and windswept for eight months out of the twelve … only for a few weeks in later summer had the landscape real beauty.”

Reading, writing, and the post office

Flora attended school in Cottisford, a mile-and-a-half walk away from Juniper Hill. On those walks, she developed an intimate knowledge of the natural world that surrounded her, which she would later use in her writing. She left school at age twelve, like the other children in the hamlet, expected to go into service.

Her mother assumed that Flora would become a nursemaid like herself and was quietly disappointed when Flora showed no interest in babies. Instead, she preferred to read and write.

Flora left home at age fourteen to work in the Post Office in nearby Fringford, where her duties included selling stamps, working the new telegraph machine, and sorting letters.

Despite the lack of formal education, writing was already central to her life. Later, she would say that she “could not remember the time when [she] did not wish or mean to write,” and that she “never left off writing essays for the pleasure of writing.” She was also a voracious reader, and while lodging in Fringford took out a library ticket at the Mechanics Institute in a nearby town and read her way through Austen, Trollope, Scott, and Dickens.

In 1898 Flora left Fringford to work at the post office in Grayshott, Hampshire, where she served some of the well-known literary figures of the time who lived in the area, including George Bernard Shaw and Arthur Conan Doyle. Overawed by their celebrity, she nearly abandoned her own writing. It was likely here that she met her future husband, John William Thompson, a post office clerk and telegraphist from Aldershott (also in Hampshire).

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Marriage (and writing in secret)By 1902 Flora was working at the post office in Twickenham. She married John Thompson on January 7, 1903, at the local St Mary’s Church. The couple then moved to Winton on the outskirts of Bournemouth, where two of their three children (Basil and Winifred) were born.

There they stayed there until 1916 when John became Postmaster at Liphook in Hampshire. Their third child, Peter, was born there as well, when Flora was forty-one. Another move followed in 1928, to Dartmouth in Devon, where the family settled.

Flora realized that her husband’s family did not approve of her “cottage origins” and regarded her passion for reading and writing as a waste of time. John did not encourage her writing either, so when the children were past infancy, she took to writing in secret.

Nature writing, literary essays, and poetry

In 1911, Flora had her first writing success when her essay on Jane Austen won a women’s newspaper competition. She subsequently sent the same newspaper another article and a short story, both of which were accepted and for which she received payment.

This seemed to precipitate a change of heart by her husband: so long as her writing paid and didn’t interfere with her responsibilities at home, then it could be tolerated.

She went on to write several short stories and newspaper articles, and when she was living in Liphook contributed two long series of articles to the Catholic Fireside magazine. One of these comprised literary essays, and the other consisted of nature writing.

Both series came from her own enthusiasm and dedication: she was a self-taught naturalist from childhood, and her literary essays were also the result of her own private study, carried out mainly in the newly established free public library system. These nature articles later went on to be collected in Margaret Lane’s A Country Calendar (1979) and in Julian Shuckburgh’s The Peverel Papers (1986).

Flora’s true real ambition was to be a poet. She lacked confidence — partly, perhaps, because of her childhood poverty and lack of formal education. She later said, “To be born in poverty is a terrible handicap to a writer. I often say to myself that it has taken one lifetime for me to prepare to make a start. If human life lasted two hundred years, I might hope to accomplish something.”

She was encouraged by Ronald Campbell Macfie, a Scottish physician and poet who had admired her writing in The Literary Monthly. This was an important friendship — the only real literary friendship she ever had — and it resulted in her first published book, a collection of poems titled Bog Myrtle and Peat, in 1921.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Lark Rise to CandlefordFlora continued to write through the family’s move to Dartmouth. From 1925 until the outbreak of war in 1939 she ran a mail-based writing club called the Peverel Society, in which members shared their own work and critiqued the work of others.

It wasn’t until 1935 that she began to write about her Oxfordshire childhood — a vanishing world of rural and agricultural traditions — with the intention of giving “a true picture of the people and time … to describe things exactly as they were, without sentimentalizing or dramatizing.”

She sent the result to Oxford University Press, who accepted it for publication. Lark Rise was published in 1939, Over to Candleford in 1941, and Candleford Green in 1942. They were first issued together as a trilogy in 1945 under the title Lark Rise to Candleford.

The books tell the lightly fictionalized story of three closely-related Oxfordshire communities — a hamlet, a nearby village, and a small market town (based on Juniper Hill, Cottisford and Fringford) — and have often been used as sources for the social history of the period. Gillian Lindsay has written that “Few works better or more elegantly capture the decay of Victorian agrarian England.”

This success came relatively late in Flora’s life — she was by then in her sixties, and she claimed that by that point she was “too old to care much for the bubble reputation.” She had never been a part of any literary circles, preferring to keep to the fringes, and was surprised at how popular the trilogy was when so much of her writing had long been ignored.

She continued to write, although no further books were published until after her death. Heatherley, an account of her time in Grayshott and seen as a sequel to Lark Rise to Candleford, was unpublished until Margaret Lane included it in A Country Calendar. Her final book, Still Glides the Stream, was published after her death in 1948.

Her later work never achieved the popularity of Lark Rise to Candleford. The trilogy has never been out of print and has been adapted for both stage and television: two musicals based on the books, Lark Rise and Candleford, were performed at London’s National Theatre in 1978 and 1979, and a four-season series was produced by the BBC starting in 2008.

Last years

In 1940, Flora’s husband John retired from the post office, and the couple moved to a cottage in Brixham, Devon. By this time their oldest son Basil had left England for Australia, while their daughter Winifred was a nurse in Bristol. Their youngest son Peter was killed in 1941 while serving in the merchant navy, when his ship was torpedoed in the Atlantic.

Flora never recovered from the loss of her son. She died of a heart attack at home in 1947, and her ashes are buried at the Longcross cemetery, Dartford, Devon.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Flora ThompsonMajor Works

Poetry

Bog Myrtle and Peat (1921)Novels

Lark Rise (1939)Over to Candleford (1941)Candleford Green (1943)Lark Rise to Candleford (1945 — the three novels published as a trilogy)Still Glides the Stream (1948, posthumous)Heatherley (1944, posthumous)Nature writing

The Peverel Papers (abridged,1986; complete, 2008)Biography

Dreams of the Good Life: The Life of Flora Thompson and the Creation of

Lark Rise to Candleford by Richard Mabey (2015)

The post Flora Thompson, Author of Lark Rise to Candleford appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 3, 2024

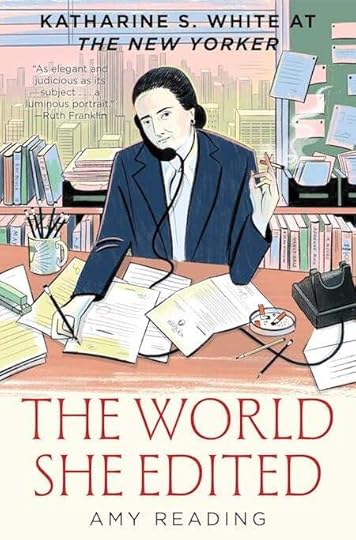

The World She Edited: Katharine S. White at The New Yorker

In the summer of 1925, Katharine Sergeant Angell walked into The New Yorker’s midtown office and left with a job as an editor. The magazine was only a few months old. Over the next thirty-six years, White would transform the publication into a literary powerhouse.

This towering but behind-the scenes figure in the history of 20th-century literature finally gets the first-rate biography she deserves in The World She Edited: Katharine S. White at The New Yorker by Amy Reading (Mariner Books, September 3, 2024; thanks to Mariner Books for supplying the content of this post).

In The World She Edited, Amy Reading brings to life the remarkable relationships White fostered with her writers and how these relationships nurtured an astonishing array of literary talent.

She edited a young John Updike, to whom she sent seventeen rejections before a single acceptance, as well as Vladimir Nabokov, with whom she fought incessantly, urging that he drop needlessly obscure, confusing words.

White’s biggest contribution, however, was her cultivation of women writers whose careers were made at The New Yorker—Janet Flanner, Mary McCarthy, Elizabeth Bishop, Jean Stafford, Nadine Gordimer, Elizabeth Taylor, Emily Hahn, Kay Boyle, and more.

She cleared their mental and financial obstacles, introduced them to each other, and helped them create now classic stories and essays. She propelled these women to great literary heights and, in the process, reinvented the role of the editor, transforming the relationship to be not just a way to improve a writer’s work but also their life.

Based on these years of scrupulous research, acclaimed author Amy Reading creates a rare and deeply intimate portrait of a prolific editor—through both her incredible tenure at The New Yorker, and her famous marriage to E.B. White—and reveals how she transformed our understanding of literary culture and community.

About Amy Reading: Amy Reading is the recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment of the Humanities and the New York Public Library. She is the author of The Mark Inside: A Perfect Swindle, a Cunning Revenge, and a Small History of the Big Con. She lives in upstate New York, where she has served on the executive board of Buffalo Street Books, an indie cooperative bookstore, since 2018.

Fascinating facts about Katharine S. White

She hired E.B. White; then reader, she married him

Katharine hired E.B. White (who went by Andy all his life) as a staff writer at The New Yorker in 1926, a year after the magazine was founded and she joined as an editor. They began an affair in 1928, and in 1929, less than three months after Katharine divorced Ernest Angell, they eloped and would stay together until her death in 1977.

It was Katharine’s role as children’s book reviewer at The New Yorker and her encouragement and industry connections that led Andy to try his hand at children’s books, thus giving the world classics such as Charlotte’s Web.

Katharine was the only woman on the The New Yorker masthead for thirty years

Katharine was 32 and the magazine was a few months old when she walked in and asked for a job. She was hired as a very part-me manuscript reader but within weeks was promoted to full-time editor. She invented her job out of nothing, at a magazine which was struggling to survive.

From the summer of 1925, when she joined the magazine a few months after its founding, to the summer of 1956, a few years before her retirement when she hired Rachel Mackenzie to replace her, Katharine White was the only woman on the masthead at The New Yorker.

Katharine cultivated many women writers

Katherine brought many women authors into the New Yorker fold, including Janet Flanner, Louise Bogan, Kay Boyle, Sally Benson, Nancy Hale, and Emily Hahn.

She adored the stories of Mary McCarthy and exerted a major campaign to get and keep her for The New Yorker; their inmate relationship was crucial for McCarthy to develop the reminiscences that first published in the magazine and eventually collected as Memories of a Catholic Girlhood. Katharine acquired and edited the works of poets Elizabeth Bishop, Adrienne Rich, and Phyllis McGinley.

She brought to American readers the Indian-born writer Christine Weston and the South African writer Nadine Gordimer, and she persuaded British authors Rumer Godden, Sylvia Townsend Warner, and Elizabeth Taylor to write for the magazine. One of her closest friendships was with Jean Stafford; she published Stafford just as she was recovering from her violent marriage to Robert Lowell, thus saving her artistic life, and continued to support her emotionally for years.

Katharine impacted numerous male authors as well

Katharine edited many of the New Yorker’s most recognizable authors, including James Thurber, John O’Hara, Ogden Nash, and Alexander Woollcott in the early years. She discovered authors who would become New Yorker names, like John Cheever, Brendan Gill, and Morley Callaghan.

She published a range of poets including Theodore Roethke and W.H. Auden. She brought a just-graduated John Updike into the magazine and they began an intense, loving, playful relaonship over words and commas and semicolons.

She avidly sought out Vladimir Nabokov, using their mutual friend Edmund Wilson as go-between, and advanced him money before he’d even published a story with her. As with Updike, she exerted a strong hand over his prose for the first few years of their association, before giving him the reins, and two of his books, Pnin and Speak, Memory began as New Yorker serials.

She defined iconic genres for The New Yorker

Katharine invented the term “casual” for a quintessential New Yorker genre, a light or humorous personal essay which could be fiction or memoir. This became a pillar of the New Yorker appeal, and it grew into the serialized reminiscences that also came to define the magazine.

She was a pioneer of Work From Home

In 1938, Andy White decided to move the family to their summer home in Maine, for his mental health and for his ability to keep wring. Katharine had a choice to make about her work-life balance.

She solved a tremendously tense problem by moving with Andy to Maine and stepping down as head of the fiction department but reinventing her job as a consulting editor who worked via the twice-daily delivery of giant mailbags full of manuscripts and letters.

She was so crucial to The New Yorker that Harold Ross and the other editors flexed to accommodate her and keep her experience and critical eye trained on their work. It would have been easy to fire her, but instead she played an enormous role in editing this urban magazine from a saltwater farm in Maine, until the war brought both Whites back to the city.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The World She Edited is available on Bookshop.org*, Amazon*,

and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . . . .

Praise for The World She Edited“As elegant and judicious as its subject, The World She Edited draws a luminous portrait of Katharine White and her life’s work: making The New Yorker into the cultural powerhouse it would become. White’s creative brilliance as an editor, the care with which she nurtured challenging personal and professional relationships (including with her equally brilliant but sometimes unstable husband), and her central place in the history of American letters have been too little recognized—an injustice that Amy Reading’s essential book has finally corrected.” —Ruth Franklin, author of Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life

“Amy Reading has recreated a lost, gilded literary world in her smart and evocative biography of Katharine White, the longtime editor at The New Yorker who helped shape postwar American literature. As we read over White’s shoulder, we gain deeper insight into the lives and work of the women writers White cultivated—Elizabeth Bishop, Mary McCarthy, May Sarton, Djuna Barnes, Nadine Gordimer, Jean Stafford, Adrienne Rich, and many others—and that of her husband, E. B. White.

One finishes this book with enormous gratitude for Katharine White’s quiet but fierce commitment to reading, writing, and women, and for Amy Reading’s determination to recognize White’s achievement. Gratitude, too, for all the drama, humor, and literary gossip that make The World She Edited the next best thing to cocktails at the Algonquin.” —Heather Clark, Pulitzer Prize winning author of Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath

“Harold Ross, James Thurber, and E. B. White usually get all the credit for the creation and shaping of The New Yorker magazine. Amy Reading’s book, carefully researched and lucidly written, makes a powerful case that Katharine White was every bit as important. They gave the magazine a tone and a style. She gave it a brain.” —Chip McGrath, former deputy editor of The New Yorker

“This beautifully written book elegantly demonstrates the vital role hidden figures play in shaping cultural taste. New Yorker editor Katharine White encouraged a world of writers – women writers especially – to produce their finest work. This sensitive, compelling book does White justice, revealing the remarkable labor of pulling something better from those who believe they’ve already done their best. American literature as we know it owes Katharine White.” —Carla Kaplan, author of Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters and Miss Anne in Harlem

*These are Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate links. If a product is purchased after linking through, Literary Ladies Guide will receive a modest commission, which helps us to keep growing.

The post The World She Edited: Katharine S. White at The New Yorker appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 2, 2024

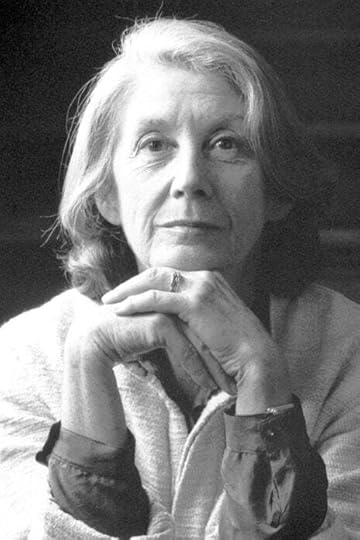

Fascinating Facts About Nadine Gordimer, South African Author & Activist

Nadine Gordimer (1923–2014) was one of South Africa’s foremost authors and anti-apartheid activists. Gordimer’s writing is internationally known for providing a rare window into politics, the human condition, and how they intersect. Mentions of her work can still spark fiery discussions today.

Following are some fascinating facts about Nadine Gordimer, whose work was recognized with the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1991.

Gordimer published her first short story collection, Face to Face, in 1949; her debut semi-autobiographical novel, The Lying Days, was published in 1953. She continued writing prolifically until her death.

Gordimer’s mother founded a daycare in apartheid South Africa

Gordimer found her political and activist roots early in life, starting with her upbringing by parents who had immigrated to South Africa. Her mother, Hannah Gordimer, was a Jewish immigrant from London who had seen her fair share of discrimination.

Hannah Gordimer founded a daycare that accepted children of color, something that was highly unusual — and illegal — for its time.

Growing up in an environment where discrimination and racism held less authority was pivotal in forming Gordimer’s worldview, and eventually inspired much of her work and political activism.

Gordimer started publishing as a teenager

By the time she was a teenager, Gordimer was writing children’s stories for several newspapers, finding her literary beginnings long before her debut stories and novels were published.

Her first short story, “The Quest for Seen Gold,” was published in the Children’s Sunday Express in 1937. Perhaps her upbringing in Springs, a small mining town, had an impact on writing about quests for gold.

She reportedly also drew from her own life for her debut novel The Lying Days (1953), which is considered autobiographical. Like the story’s protagonist, Gordimer moved outside her small hometown to “the big city” later in her life.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Nadine Gordimer

(photo from the Nobel Prize Archive)

. . . . . . . . . . .

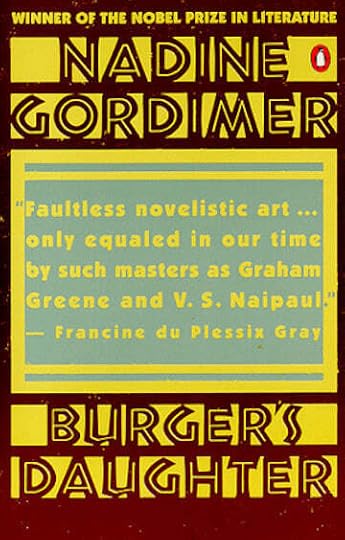

Gordimer was one of the authors subjected to apartheid book banning, which made reading or owning any of the listed books a criminal offense.

The Late Bourgeois World was the first book to be banned in 1976, the same year in which the violent Soweto Uprising took place. The apartheid government also banned Burger’s Daughter (1979) and July’s People (1981) soon after their publication.

Gordimer protested the book bans together with other authors, leading to their unbanning just months after the books had been placed on the list. According to the then-government, Gordimer’s books were too ’one-sided’ to continue being controversial. See more in The Banning of Nadine Gordimer’s Anti-Apartheid Novels.

Gordimer maintained a close friendships with Nelson Mandela

Gordimer moved in anti-apartheid and political circles, which formed the foundation for some of her stories. Allies and friendships were especially important to her, as she mentioned the arrest of friends as pivotal to her more serious political activism. That includes one of the reasons she joined the African National Congress (ANC) when it was still a banned organization.

Her friendships with Nelson Mandela’s attorneys, Bram Fischer and George Bizos, would also form a direct inspiration for her later novels.

Gordimer remained connected with Nelson Mandela during the time of his 1962 trial, and advised him on his 1964 trial defense speech. Upon Nelson Mandela’s release from prison, Gordimer was one of the first people he requested to see.

Gordimer’s personal life was the subject of an unauthorized biography

Nadine Gordimer was married twice in her life, first to Gerald Gavron (1949 to 1950), and then to Reinhold Cassirer (1951 to 2001). Her marriages generated plenty of controversy later in her life, becoming the subject of an unauthorized biography.

The biography claimed an affair by Gordimer in the 1950s as well as further claims regarding her second husband’s death: Gordimer immediately pulled her approval for the manuscript, though it was still published as an account of her life in 2006.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Gordimer wrote about post-apartheid South Africa in her “transitional period”Nadine Gordimer went from writing about apartheid to exploring the possibilities within a free and unoppressed South Africa. With a career spanning several decades, Gordimer saw enormous changes in the country.

Her later writing went beyond apartheid themes, including how legal changes affected the average household. In The House Gun, she explored what would happen if a household firearm killed someone — and the novel greatly used the mindset of gun ownership in a political environment as a storytelling tool.

Her further transitional writing explored themes like romance and immigration, branching into the politically-loaded international love story The Pickup (2001).

July’s People was briefly censored again in 2001

Gordimer’s writing wasn’t just banned during apartheid years, but also became a source of controversy in later years: July’s People was removed from school reading lists by the Department of Education in 2001.

According to the department, the book was too controversial for the provincial school curriculum. However, Gordimer was quick to protest the ban, like she had done previously.

. . . . . . . . .

8 Essential Novels by Nadine Gordimer

. . . . . . . . .

Nadine Gordimer spent time as lecturer outside the boundaries of Southern Africa, though she never left the country permanently. She didn’t wish to be cut off from her country of origin.

In the early 2000s, she briefly left Southern Africa and lectured at Massey College at the University of Toronto. However, she eventually returned to South Africa, and continued to live in her Parktown, Johannesburg home until her passing.

No Cold Kitchen is an unauthorized biography of Gordimer’s life

No Cold Kitchen (2006) by Ronald Suresh Roberts is considered an unauthorized biography of Nadine Gordimer’s life. However, it was originally supposed to be a biography written alongside the author, and with her final approval.

Gordimer withdrew her approval for the manuscript’s draft, citing disputes about a 1950s affair and further disagreements about her husband (Kassimer’s) illness and death. In her accounts, Gordimer claimed the book’s author had breached their trust agreement, and refused to grant her approval. However, Roberts went ahead and published the unauthorized biography.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Alex J. Coyne, a journalist, author, and proofreader. He has written for a variety of publications and websites, with a radar calibrated for gothic, gonzo and the weird. His features, posts, articles and interviews have been published in People Magazine, ATKV Taalgenoot, LitNet, The Citizen, Funds for Writers, and The South African, among other publications.

Further Reading & Sources Britannica Nobel Prize: Nadine Gordimer Facts University of Johannesburg Special Collections Nadine Gordimer obituary in The Guardian Nadine Gordimer: 5 Essential Reads from the Award-Winning Author Encyclopedia.comThe post Fascinating Facts About Nadine Gordimer, South African Author & Activist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 27, 2024

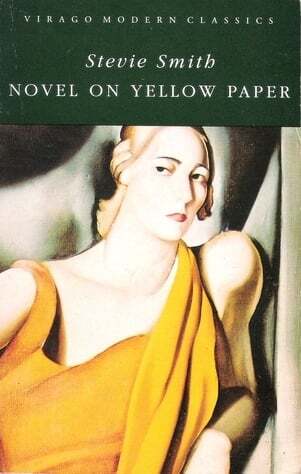

Stevie Smith, English Poet and Author of Novel on Yellow Paper

Stevie Smith (September 20, 1902 – March 7, 1971) was known for satirical poetry as well as novels (including her best known, Novel on Yellow Paper) suffused with black humor, acid wit, and unorthodox contemplations of death.

Vastly different cultural epochs bookended her life. She was born the year after the end of the conservative Victorian Era and died the year after the turbulent “Me Decade”of the 1970s, as author Tom Wolfe dubbed it. (Photo above courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

As The British Empire lost its colonies and women gained independence, Smith’s poetry tapped into the era’s emotional and societal upheaval.

Early lifeFlorence Margaret Smith was born in Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, England in 1902. Her father was a shipping agent, and her maternal grandfather was a maritime engineer. Her parents’ marriage was disastrous, and the year Stevie turned three, her father abandoned the family to pursue a career at sea.

Stevie’s father occasionally appeared on 24-hour leaves or sent the briefest of postcards. She and her older sister Molly refused to meet him in later life or attend his funeral. Stevie later described the rupture with characteristic levity that couldn’t disguise her inner pain:

I sat upright in my baby carriage

And wished mama hadn’t made such a foolish marriage,

I tried to hide it, but it showed in my eyes unfortunately

And a fortnight later papa ran away to sea.

( “Papa Love Baby”)

Another major event in Stevie’s childhood was a diagnosis of tubercular peritonitis at age five, and she was sent to a nursing home for tubercular children, per the custom of the time. When she recovered and returned home three years later, she was thankfully enveloped once again in what she described as a secure “house of female habitation.”

For the rest of her life, Stevie vividly described the terrors of childhood without a whiff of sentimentality. In her persona as a poet, she combined the forlorn air of a “little girl lost” with the cool-headed cynicism necessary to survive as a woman writer.

Stevie, Molly, and their mother moved to a house in the suburb Palmer’s Green in North London, along with their maternal aunt Madge Spear, who was soon dubbed “Lion Aunt.” As their mother declined from the heart disease that killed her the year Stevie turned sixteen, Madge raised her nieces with fierce pride and devotion, even if she did not always understand her niece’s literary bent.

There wasn’t much money, but Lion Aunt insisted on her nieces attending excellent schools, and Smith and her sister enjoyed theatricals, the hymns at church, and trips to the country. The nickname “Stevie” was acquired in her late teens when she was riding with a friend and was compared to legendary horse jockey Steve Donoghue. She kept the moniker for the rest of her life.

. . . . . . . . . .

Stevie Smith in 1966 (fair use image)

. . . . . . . . . .

Young adulthood and the start of a career

Stevie described herself as “nervy, bold, and grim.” Her friend and literary executor James MacGibbon described her singular appearance:

“She … dressed with some care in a style of her own which had, at first sight, and specially when she aged, a ‘little girl’ look; but one soon saw that it was perfectly appropriate and never without dignity … her fine-boned features were of a striking beauty that was never more apparent than when death approached.”

Stevie memorably described her appearance in her poem “The Actress”:

I have a poet’s mind, but a poor exterior,

What goes on inside me is superior.

Instead of attending university, Stevie worked as a secretary in a magazine publishing company, where she remained for the next thirty years. She later supplemented her salary by writing book reviews for The Observer, among other prestigious publications. The undemanding job ensured she had time to entertain visiting friends in her office with tea, buttered toast, and strawberry jam, as well as write acerbic poems on the sly.

Stevie remained in the same house for the rest of her life and devotedly cared for her aunt until her death at age ninety-six.

. . . . . . . . .

Novel on Yellow Paper (1936)

. . . . . . . . . .

Stevie didn’t gain notice with her first printed poems, and an editor told her to try to write a novel instead. In six weeks, she finished her first, Novel on Yellow Paper, published in 1936. Her first poetry collection, A Good Time Was Had By All, arrived a year later.

When Novel on Yellow Paper was published, it caused a minor furor in the London literary scene. She had come out of nowhere and written a heroine—Pompey Casmilus—who, like Stevie, was a secretary with very determined opinions about seemingly everything that affected an independent young woman in interwar England. Pompey even has opinions about her countrymen and their views:

“One of the greatest qualities which have made the English a great people is their eminently sane, reasonable, fair-minded inability to conceive that any viewpoint save their own can possibly have the slightest merit.”

The London Times Literary Supplement described the debut novel as “a curious, amusing, provocative and very serious piece of work.” Stevie’s subsequent novels, Over the Frontier (1938) and The Holiday (1949), never achieved her original notoriety or varied readership, and Smith appeared happy to return to poetry.

In 1962, Stevie received a letter from another poet, another young woman chafing at society’s expectations, who was looking forward to finally getting to read the novel nearly thirty years after it was first published:

“I better say straight out that I am an addict of your poetry, a desperate Smith-addict. I have wanted for ages to get hold of A Novel on Yellow Paper (I am jealous of that title, it is beautiful, I’ve just finished my first, on pink, but that’s no help to the title I fear) … I am hoping by a work of magic, to get myself and the babies to a flat in London by the New Year and would be very grateful in advance to hear if you might be able to come to tea or coffee when I manage my move—to cheer me up a bit. I’ve wanted to meet you for a long time.”

The letter was from Sylvia Plath, the now-iconic poet and author of The Bell Jar. Sadly, Plath never got to have tea with Stevie — she took her own life less than three months later.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Stevie Smith’s poetry, style, and themesWith a typical dry understatement, Stevie detailed her unique views on the craft of poetry in her essay “My Muse”:

“All poetry has to do is to make a strong communication. All the poet has to do is to listen. The poet is not an important fellow. There will always be another poet.”

Stevie trusted her instincts, and early on, she knew which poetry subjects interested her the most and which her style best suited. She rarely wrote of pressing political subjects (although her poem The Leader is a powerful and frighteningly relevant portrait of a Fascist dictator).

She also rarely wrote about romance or happy relationships, finding the travails of modern courtships and marriages — both in the isolated suburbs and crowded cities — more intriguing. In a letter, she bluntly confided, “I don’t much like the ding dong theme of love, love, love.”

Many of her poems are flavored with spiky, biting, black humor. Smith was not interested in sugar-coating anything, and she knew that a laugh or a punchline could get an unpleasant point across. In her (typically cheeky) poem “To an American Publisher,” she retorts:

You say I must write another book? But

I’ve just written this one.

You like it so much that’s the reason?

Read it again then.

Peruse a handful of Stevie Smith’s poems, and you’ll see that, like Emily Dickinson, she flagrantly used hymn meter to structure many of her poems. This stylistic choice enabled many of her poems to have a deceptive simplicity and sense of urgency and make them easier to remember.

I am not God’s little lamb

I am God’s sick tiger.

And I prowl about at night

And what most I love I bite.

from “Little Boy Sick”

Though she appeared very secure in her choice of themes and writing style, Smith still needed reassurance from friends and fellow writers. She once wrote to author Rosamond Lehmann: “I wish there was some litmus paper test you could have for your poems, blue for bad and pink for good.”

Two of the most recurring themes in her poetry are God and death, which are often intertwined in the poems. “You are quite potty about death,” says one of her characters to another in her novel The Holiday. Despite her nearly lifelong agnosticism, she didn’t appear to be afraid of death. Musing on it was a good copy of her poems and the siren call to return to the faith.

“I’m a backslider as a non-believer,” she once described herself. In her poem “God the Eater,” she described the pull of faith:

There is a god in whom I do not believe

Yet to this god my love stretches.

Reverend Gerard Irvine, an unlikely longtime friend, described Smith’s religious beliefs thus:

“In religion, Stevie was ambivalent: neither a believer, an unbeliever nor agnostic, but oddly all three at once…She was scornful of what she considered watered-down reformulations of the faith, and disgusted by their liturgical expression. One could say she did not like the God of Christian orthodoxy, but she could not disregard Him nor ever quite bring herself to disbelieve in him.”

The year before her death, Smith wrote a scathing review of the publication of the New English Bible, describing its translators as “smudgers and meddlers.” She often expressed to friends her love of the King James Version. Again and again, she appears to approach Christianity, only to recoil once again due to the condemnatory doctrine of hell and the hypocritical behavior of many of its followers.

In her poem “Thought About the Christian Doctrine of Eternal Hell,” which is part of her extended essay “Some Impediments to Christian Commitment,” she described her overwhelmingly adverse reaction to organized religion—including its history of using violence to quell dissent and the moral hypocrisy of many of its followers—as such:

The religion of Christianity

Is mixed of sweetness and cruelty…

This God the Christians show

Out with him, out with him, let him go.

Repeatedly, Stevie attested to her love of the figure of Jesus Christ and the stately church ceremonies, but she always withdrew, writing of her conflict with the brutal honesty and reluctant awe of Gerard Manley Hopkins. After the publication of Harold’s Leap (1950), Michael Tatham described her as “one of the few religious poets of our time.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Illustrations by Stevie SmithStevie loved decorating her poems with her simple line illustrations. They look deceptively like juvenile stick-figure doodles, but she can ably and disconcertingly depict confusion, malice, and despair in just a few pen strokes.

In his preface to her Collected Poems, James MacGibbon described her poetry as “embroidered” by her illustrations. He said, “If Stevie had taken them more seriously, no doubt these drawings would have made her a renowned cartoonist.”

Stevie was in good company when it came to her unconventional illustrations: William Blake and Ogden Nash often illustrated their poems, and Flannery O’Connor (also eccentric, mordant-witted, and intensely critical of religious hypocrites) seriously considered a career as a cartoonist before turning to fiction.

As it happens often with lifelong unmarried women authors, there are speculations about Stevie’s personal life, and if her writing fulfilled her as much as marriage and children would have done. Regarding children, she once wrote: “I’m very fond of children. Why I admire children so much is that I think all the time, ‘Thank heaven they aren’t mine.’”

There are also lingering questions about whether she had a relationship with George Orwell when they briefly worked together during World War II. (And her book of illustrations—Some Are More Human Than Others—obviously references Orwell’s Animal Farm.) However, Smith had this to say of speculating about the dead who cannot explain or defend themselves:

“Read the stories and the poems the sinners write, but leave their private lives (as we should like our own sinning lives to be left—remembering that equation which cannot truly be cast by any human being) to heaven. So one feels. One may be wrong.”

“Unique and cheerfully gruesome” — success as a poet

In 1953, Stevie attempted to take her own life, and doctors encouraged intensive physical rest. She retired from her publishing job with a good pension and settled into book reviewing and writing poetry full time, with her aunt guarding the door from unwelcome distractions.

A second attempt never occurred, and increasing stature as a poet brought more color and friendships into her life at Palmers Green.

Stevie’s flagrant depiction of friends and acquaintances in her poetry and novels often lost those people as a result, but many more remained. Although devoted to her aunt, Smith enjoyed her jaunts into sophisticated London literary circles and invitations to some of England’s most splendid country houses.

When asked about her motivation for writing, she told her friend John Hayward: “It’s not the fame, dear, it’s the company.”

Her near brush with death gave her plenty of material to draw from, and in 1957, the title poem of her collection Not Waving but Drowning became her most famous and anthologized.

Nobody heard him, the dead man,

But still he lay moaning:

I was much further out than you thought

And not waving but drowning.

Read the rest of this poem here.

In her analysis for the Poetry Foundation, Caitlin Kimball writes that the poem is a “twelve-line punch to the gut” and “one of her most sober and plainly nihilistic pieces…It’s a grim premise: Life is a series of opportunities to be misunderstood.”

For the rest of her career, Stevie wrote about death, viewing it dispassionately as an inevitable conclusion to her life rather than with existentialist trepidation.

Augmented with jabs of humor and unassuming illustrations, Stevie knew that her poems, simple at first glance, could pack a punch. This often resulted in mixed reviews from her contemporaries, but most were cautiously admiring.

“One turns to Stevie Smith and enjoys her unique and cheerfully gruesome voice,” wrote the American poet Robert Lowell.

Critic Linda Rahm Hallett wrote that “the apparent geniality of many of her poems is in fact more frightening than the solemn keening and sentimental despair of other poets, for it is based on a clear-sighted acceptance, by a mind neither obtuse nor unimaginative, but sharp and serious, innocent but far from naive.”

In 1966, Stevie Smith was awarded the Cholmondeley Award for Poets. Along with her poetry collections, she enjoyed having a radio play produced by the BBC and increasing notoriety as a poetic voice for disgruntled nonconformists.

Final years

A doctor once told Stevie that her life “was a failure,” presumably due to her being unmarried and childless. She wrote of loneliness, often the inevitable companion of a writer who willfully rows against the cultural grain. She frequently pointed out the loneliness in mismatched marriages and unhappy families.

Anthony Thwaite, a fellow poet and critic, wrote of her “vast succession of friends, male and female, single and married, literary and non-literary…She was also a copious letter and postcard writer, a keeper-in-touch.”

Her letters reveal the pleasure she took in encouraging and promoting fellow writers’ work, as she wrote to one of them: “I hope you are flourishing and writing like stink.”

In her later years, Stevie gave unusual readings at literary societies and in schools, often chanting her poems in a sing-song voice. She attended a “Psychedelic Feast” poetry event in 1967 alongside much younger Beat poets and was a hit with those in attendance.

In 1968, Stevie lost her “Lion Aunt.” She had left her job to nurse her Aunt Madge and was happy to return the devotion her aunt had showered on her for so long. In Novel on Yellow Paper, Stevie paid tribute to the most steadfast love in her life. “Darling Auntie Lion … You are yourself like shining gold.” Sadly, soon after their aunt’s passing, Stevie’s older sister Molly suffered a stroke.

A year later, Stevie was awarded the Gold Medal for Poetry by Queen Elizabeth II; her friends were amused by varying preposterous descriptions of the royal encounter.

She saw the publication of her ninth poetry collection, The Best Beast, but was soon after diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor. The battle was mercifully brief, and she passed away on March 7, 1971, at the age of sixty-eight.