Nava Atlas's Blog, page 11

April 26, 2024

5 Life-Changing Philosophical Books by Women Writers

Impressively, these five women writers wrote eighty-two books in total, which also include their works of poetry, plays, and academic essays. Highlighted here are five particularly important philosophical works from their collective bibliography.

These books are intensely practical in their philosophical narratives and also present ideas that are beautiful in a genre-defying kind of way. As Albert Einstein once said: “Pure mathematics is, in its way, the poetry of logical ideas.” There’s something literary and artistic in a well-crafted idea.

. . . . . . . . . . .

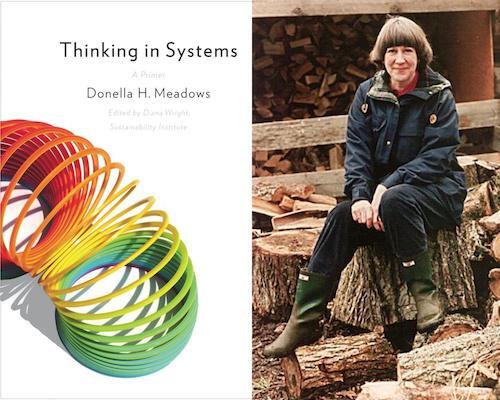

Thinking in Systems by Donella Meadows:on the philosophy of complex systems

Many people are now discussing topics relating to “systems thinking” and the science of complexity. We have women like Donella Meadows to thank for it. Because it’s one thing to have a siloed academic discussion about these topics, and quite another to have them enter mainstream thought.

Complex systems are incredibly important for understanding everything from the evolution of life on our planet, to the social dynamics of cities, to the inner workings of our minds. Meadows’ book, Thinking in Systems, is the perfect primer for those who are just dipping their toes into this subject. You will learn about important and generalizable principles, such as what Meadows calls leverage points:

“Leverage points are…places in the system where a small change could lead to a large shift in behavior. This idea of leverage points is not unique to systems analysis—it’s embedded in legend: the silver bullet; the trimtab; the miracle cure; the secret passage; the magic password; the single hero who turns the tide of history; the nearly effortless way to cut through or leap over huge obstacles.”

This book challenges us to see the world in a whole new way and acts as a map for the new territory it describes. Where might we find these leverage points that dramatically transform the systems we live within?

. . . . . . . . . . .

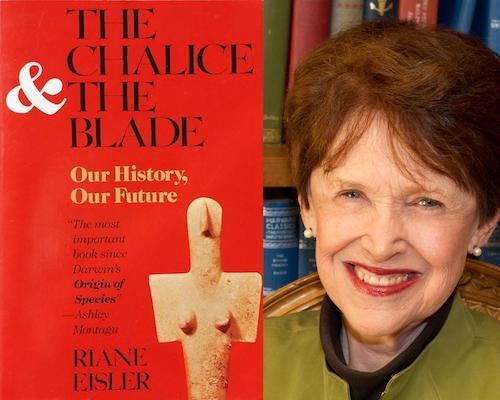

The Chalice and the Blade by Riane Eisler:on the philosophy of hierarchies

There is some baggage that comes with the word “hierarchy.” This is something Riane Eisler, author of ten books and now in her 92nd year of life, must know. But she doesn’t want us to throw out the idea of hierarchy, or indiscriminately hate it.

Her work, The Chalice and the Blade, actually has the potential to bring much more positive aspects of hierarchies to light. And that begins with her distinction between two “flavors” of hierarchies. The first (symbolized with the blade) is the domination or dominator hierarchy which many people think of when they hear this word.

For them, this is the only kind of hierarchy. It is, in that view, a structure of oppression and inequality, fueled by violence, and leading toward the concentration of power. The second variety (the chalice) is what Eisler calls an actualization, growth, or partnership hierarchy.

This is an organizational structure of mutual fulfillment, fueled by love and reciprocity, and leading toward the distribution of power.

“Domination hierarchies are very different from a second type of hierarchy, which I propose be called actualization hierarchies. These are the familiar hierarchies of systems within systems, for examples, of molecules, cells, and organs of the body: a progression toward a higher, more evolved, and more complex level of function. By contrast, as we may see all around us, domination hierarchies characteristically inhibit the actualization of higher functions, not only in the overall social system, but also in the individual human.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

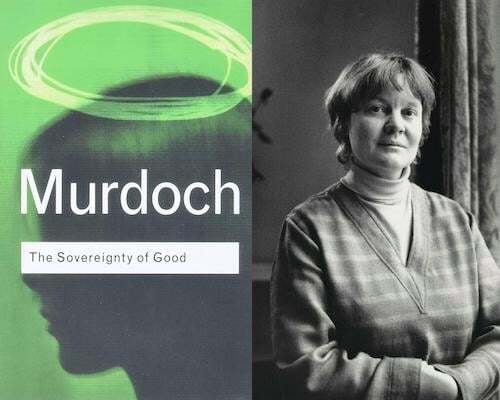

The Sovereignty of Good by Iris Murdochon the philosophy of goodness

Iris Murdoch is the author of twenty-six novels, several of which have won prestigious literary awards. In addition to her beloved works of fiction, Murdoch also wrote several impressive books on philosophy.

She was particularly adept as a modern spokesperson for the kind of Platonic realism that was largely out of fashion—making her into an iconoclastic defender of ideas that others were ready to discard. Along with several other influential literary ladies, Murdoch helped breathe new life into moral philosophy and post-God metaphysics.

Her most powerful and succinct work of philosophy is arguably The Sovereignty of Good. Though it is still dense and challenging, it is also highly readable. In the quote below, Murdoch shares some thoughts on her distinctive brand of naturalistic mysticism.

“There is a place both inside and outside religion for a sort of contemplation of the Good, not just by dedicated experts but by ordinary people: an attention which is not just the planning of particular good actions but an attempt to look right away from self towards a distant transcendent perfection, a source of uncontaminated energy, a source of new and quite undreamt-of virtue… This is the true mysticism which is morality, a kind of undogmatic prayer which is real and important, though perhaps also difficult and easily corrupted.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Governing the Commons by Elinor Ostrom:on the philosophy of economics

Does economics seem dry? Un-literary? Don’t worry—this isn’t one of those books that tediously demonstrates how change X in supply chain Y has effect Z on the price equilibrium of toothpaste. Rather, Eleanor Ostrom was a philosopher of economics who challenged our deepest assumptions and broadened our world.

Her best-known work, Governing the Commons, explores a neglected third road that runs between two other long-standing economic paradigms. This third route is meant to address one of our thorniest and most persistent problems:

“Hardly a week goes by without a major news story about the threatened destruction of a valuable natural resource … A New York Times article focused on the problem of overfishing in the Georges Bank… Everyone knows that the basic problem is overfishing; however, those concerned cannot agree how to solve the problem … The issue in this case–and many others–is how best to limit the use of natural resources so as to ensure their long-term economic viability …

Some scholarly articles about the ‘tragedy of the commons‘ recommend that ‘the state’ control most natural resources to prevent their destruction; others recommend that privatizing those resources will resolve the problem. What one can observe in the world, however, is that neither the state nor the market is uniformly successful in enabling individuals to sustain long-term, productive use of natural resource systems.”

Ostrom was recognized with a Nobel Prize for her work—the first woman to ever receive that award in an economic field. Those who open her books will find wisdom that has never been more relevant than it is today. Her lessons can help us shape better and more just economic systems.

. . . . . . . . . . .

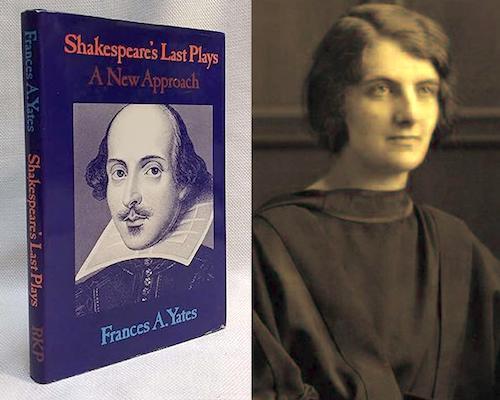

Shakespeare’s Last Plays by Frances Yates:on the philosophy of Shakespearean magic

Writing about Shakespeare is like writing about love or religion or politics. There are so many voices that compete for space that it’s hard to be confident that one is saying anything new at all. Like Iris Murdoch once wrote, one can reach a moment of negation in which “all one’s hard won knowledge and carefully thought-out conclusions suddenly seem to be commonplace.”

So what can be said about Shakespeare that will surprise us? What about connecting him to a tradition of serious occult magic, secretive esoteric societies, a powerful Queen, and the expansion of the British Empire?

Frances Yates argues in Shakespeare’s Last Plays that his later works take a decidedly magical turn. As in, they are not just comedies or dramas to be casually enjoyed. They are also works of philosophical fiction that conveyed just how serious the vocation of magus was during the Renaissance.

Characters like Prospero in The Tempest were modeled after the real magicians of the Elizabethan era–figures like John Dee, who was the Queen’s “in-house” alchemist.

“It is inevitable and unavoidable in thinking of Prospero to bring in the name of John Dee, the great mathematical magus of whom Shakespeare must have known… Dee permeated the whole Elizabethan age, from the Queen downwards. That he was the inspiration of Shakespeare’s Prospero is very strongly indicated… To treat of magic, or the magical atmosphere, in Shakespeare one ought to include all the plays, for such an atmosphere is certainly present in his earlier periods. In the Last Plays this atmosphere becomes very strong indeed and, moreover, it becomes more clearly associated with the great traditions of Renaissance magic–magic as an intellectual system of the universe…, magic as a moral and reforming movement.”

The “moral magic” hidden in Shakespeare’s last plays was, thankfully, rediscovered by Yates. And we can still turn to her work when seeking lessons about how to transform our world.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Evan Atlas. Evan is a writer and political philosopher from New York’s Hudson Valley. His work confronts our most significant challenges, and develops a theory of change for the 21st century that is unlike anything you’ve heard before. He believes that the future of humanity can be more loving, more free, and more beautiful, but that this future is in danger. Join him at evanatlas.com and help create a more beautiful planet.

The post 5 Life-Changing Philosophical Books by Women Writers appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 15, 2024

15+ Classic Novels for Middle Grade Readers

These classic novels for middle grade readers, written by women authors of the distant and recent past, spark curiosity and take the reader on grand adventures. They also impart wisdom that can be enjoyed by all ages.

Books provide guidance, exploration, and companionship among so many other things – this is especially true for young readers. A good novel can expand our knowledge of the world; when the world feels overwhelming, a novel provides a comforting and familiar companion.

. . . . . . . . . .

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott (1864)

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott: There is no need for me to explain what it is about the writing and the characters that are so powerful and endearing, for I know that many, many readers have experienced it too. We laugh at Jo’s antics, and feel Teddy’s heartbreak, and weep when Beth takes her last breath.

I know that Little Women will always be a book I come back to for comfort, guidance, and enjoyment. It will be a book I will read to my children. It will be a book that will still teach me, even as I age. And I hope I will never cease to find a piece of myself within it.

. . . . . . . . . .

Hans Brinker by Mary Mapes Dodge (1865)

Hans Brinker by Mary Mapes Dodge is the classic tale of Hans and his sister Gretel (not to be confused with Hansel and Gretel). It takes place in Holland, and though the author created a lovely picture of Dutch life in the early 19th century, she never visited the country until well after the book’s publication.

The family is relatable and timeless because they “are very real people with ambitions, hopes and problems that the young reader shares as he or she reads their story. The Brinkers are very poor, but during one eventful winter many wonderful things happen to them.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Black Beauty by Anna Sewell (1877)

Black Beauty by Anna Sewell wasn’t intended as a children’s book; rather, she wrote it for those who owned or worked with horses, “to induce kindness, sympathy, and an understanding treatment of horses.”

A unique feature of the book is that the story is told by the horse; it is, after all, subtitled The Autobiography of a Horse. He’s sensitive and intelligent, sharing his feelings and thoughts as his story unfolds.

Black Beauty was published in 1877 in England, and in 1890 in the U.S. and ever since, has been one of the best-selling children’s books of all time.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett (1905)

A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett has endured as a timeless tale. The story of A Little Princess follows a young girl with a vivid imagination as she faces abandonment at a posh boarding school in London with a cruel headmistress.

The riches-to-rags story was so successful that in 1902, Burnett adapted the story of Sara Crewe into a three-act stage play under the title, A Little Un-Fairy Princess. The novel has since been adapted into several film versions, TV shows, musicals, and other theatrical productions.

. . . . . . . . . .

Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery (1908)

Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery was a great success from the time it was published, and has appealing to generations of readers of all ages and backgrounds sine.

Anne Shirley is a dreamy, imaginative 11-year-old orphan girl mistakenly sent to middle-aged brother and sister Matthew and Marilla Cuthbert, who meant to adopt a boy to help on their farm.

Set in Prince Edward Island, where the author grew up, the original volume and its sequels follow Anne from her arrival in the fictional town of Avonlea, through school, college, marriage, and motherhood.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Girl of the Limberlost by Gene Stratton (1909)

A Girl of the Limberlost was Gene Stratton’s third novel, published in 1909 as a sequel to Freckles (1905), both of which are stories for “children of all ages.” Gene was enchanted by the great outdoors from an early age and was encouraged by her parents to explore her surroundings. Her love of nature served as the foundation for her career as a naturalist, photographer, and writer.

In the course of her early explorations, Gene came upon the Limberlost Swamp near her home in rural Indiana. There she discovered birds, butterflies, and wildflowers that captured her imagination. A 1909 review of the book wrote:

“Here’s a sweet and tender tale which is a welcome addition to the libraries of our young people, as well as delightful reading for older ones. It is a sympathetic story with the ennobling love of nature as its basic thought.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett (1911)

The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett follows the journey of Mary Lennox, a sickly and unloved ten-year-old girl born to wealthy British parents in India.

After a cholera epidemic kills her parents, Mary is sent to England to live with her Uncle Archibald in an isolated, mysterious house. The tale follows the spoiled and sulky young girl as she slowly sheds her sour demeanor after discovering a secret, locked garden on the grounds of her uncle’s manor.

. . . . . . . . . .

Emily of New Moon by L.M. Montgomery (1923)

Emily of New Moon by L.M. Montgomery is the start of a trilogy of novels about Emily Byrd Starr that invites comparison with the beloved Anne of Green Gables series. These books, as is true for many of L.M. Montgomery’s writings, are meant for “children of all ages.”

Legions of readers have been devoted to Anne, while others prefer the more contained Emily, who is grounded in her passionate ambition to become a writer. The Emily trilogy shows her in the act of writing, living, and breathing writing, and working to improve her craft. That single-minded devotion to the art of writing is a rarity in children’s literature.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Little House Series by Laura Ingalls Wilder (1932)

The Little House Series by Laura Ingalls Wilder is an autobiographical series of novels that reflect on the authors life on the American frontier. Though beloved by generations of young readers, they haven’t been without controversy, as we’ll soon discover.

The Ingalls family traveled by covered wagon through Kansas and Minnesota with all that they owned, until finally settling in De Smet, Dakota Territory. The family loved the open spaces of the prairie. They moved around quite a bit, and though it wasn’t an easy life, it gave Laura a rich trove of memories and experiences to draw upon when she began writing.

Wilder (1967–1967) wrote these vivid tales — nine in the Little House series — that immediately appealed to readers of all ages. The books were an immediate critical and popular success, winning numerous awards and making their way into readers’ hearts with their message of endurance, simple living, and love of family.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Rescuers by Margery Sharp (1959)

The Rescuers by British author Margery Sharp launched a series of books starring Miss Bianca, a socialite mouse who assisted animals as well as humans in perilous situations, and fellow mice Bernard and Nils. These well-received children’s novels have had legions of grown-up fans as well, and all told added up to nine books.

Disney adapted the stories to two animated films, The Rescuers (1977) and The Rescuers Down Under (1990). Margery Sharp’s classic tale of pluck, luck, and derring-do is amply and beautifully illustrated by the great Garth Williams.

. . . . . . . . .

I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith (1948)

I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith is the story of Rose and Cassandra Mortmain, two sisters who are part of an eccentric family living in genteel poverty in a crumbling castle in the 1930s. At the time of its publication, Smith was an established playwright, and would later become even better known for the children’s classic, The 101 Dalmatians (1956).

This coming-of-age novel has been beloved by young adults ever since it was published in 1948. Critics were kind as well, as in the words of this original 1948 review:

“Finding out what happens makes rewarding reading. This is a captivating — an enchanting story, bit it is also shrewd commentary on life and art and the complexity of the human heart.”

. . . . . . . . . .

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle (1962)

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle was almost never published. L’Engle reflected, “You can’t name a major publisher who didn’t reject it.” It took just that one publisher to take the chance, and the rest is literary history. It has not only won some of the most prestigious publishing awards, it’s also one of the most frequently banned books of all time.

Best of all, with A Wrinkle in Time, L’Engle become one of the pioneers not only opened a path for more complex children’s literature (think: Harry Potter). Once the book came out, it was widely praised.

. . . . . . . . . .

Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh (1964)

Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh is set in Manhattan’s upper east side, stars 11-year-old Harriet M. Welsch, who wants to be a famous writer when she grows up. To prepare, she keeps a notebook in which she records details of the world around her in minute detail.

Her observations of the people in her life are funny, poignant, and sometimes cruel. When her sixth-grade classmates find and read the contents of her notebook, Harriet’s world turns upside down.

When the book was first published, critical reaction was quite positive. Harriet is relatable and though quite flawed, she’s also evidently lovable and memorable.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Arm of the Starfish by Madeleine L’Engle (1965)

The Arm of the Starfish by Madeleine L’Engle is a tense, well-plotted story of suspense which, while having much to say about basic values and human loyalties, moves to an extraordinary and satisfying conclusion. Young Adam Eddington, a brilliant student specializing in marine biology, secures a summer job as assistant to the world-famous Dr. O’Keefe, who’s laboratory is situated on Gaea, a small island off the coast of Portugal.

Before the plane takes off from Kennedy International Airport, Adam makes the acquaintance of Caroline Cutter, an attractive girl whose father has business interests in Portugal.

Caroline is going to Lisbon, too, but on another airline. Caroline warns Adam inn a hurried and unclear manner against a certain Canon Tallis who, along with a 12-year-old redheaded child, is to be a passenger on Adam’s flight.

. . . . . . . . . .

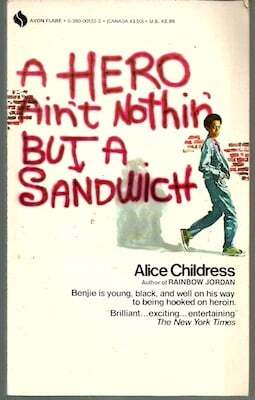

A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ But a Sandwichby Alice Childress (1975)

A contemporary classic by Alice Childress, this book was adapted to a film of the same name. Her concern about reaching young people led to her writing this books. This searing novel about a young heroin addict was highly praised as a “surprisingly exciting” use of the author’s “considerable dramatic talents to expose a segment of society seldom spoken of above a whisper” in the New York Times.

Feminist literary critic Susan Koppelman Cornillon (Images of Women in Fiction) said that Hero “revolutionized writing for young adults by introducing the nitty-gritty realities of urban life.” The American Library Association named Hero best Young Adult Book of 1975 and it was made into a feature film starring Paul Winfield and Cicely Tyson in 1977.

. . . . . . . . . .

Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt (1975)

Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt is a remarkable novel about mortality and immortality that rewards young and adult readers alike. Originally intended for middle grade children, it’s a gracefully written story that has resonated with readers of all ages. It explores the idea of eternal life, and its flip side, mortality.

When 10-year-old Winnie Foster inadvertently comes upon the Tuck family, she learns that they became immortal when they drank from a spring on her family’s property.

They tell Winnie how they’ve watched life go by for decades, while they themselves never grow older. Winnie must decide if she’ll keep the Tucks’ secret, and whether she wants to join them on their immortal path.

The post 15+ Classic Novels for Middle Grade Readers appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

15 Classic Novels for Middle Grade Readers

These classic novels for middle grade readers spark curiosity, take the reader on grand adventures, and impart wisdom that can be enjoyed by all ages.

Books provide guidance, exploration, and companionship among so many other things – this is especially true for young readers. A good novel can expand our knowledge of the world or when the world feels too big a novel provides us with a comforting and familiar companion.

. . . . . . . . . .

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott (1864)

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott: There is no need for me to explain what it is about the writing and the characters that are so powerful and endearing, for I know that many, many readers have experienced it too. We laugh at Jo’s antics, and feel Teddy’s heartbreak, and weep when Beth takes her last breath.

I know that Little Women will always be a book I come back to for comfort, guidance, and enjoyment. It will be a book I will read to my children. It will be a book that will still teach me, even as I age. And I hope I will never cease to find a piece of myself within it.

. . . . . . . . . .

Hans Brinker by Mary Mapes Dodge (1865)

Hans Brinker by Mary Mapes Dodge is the classic tale of Hans and his sister Gretel (not to be confused with Hansel and Gretel). It takes place in Holland, and though the author created a lovely picture of Dutch life in the early 19th century, she never visited the country until well after the book’s publication.

The family is relatable and timeless because they “are very real people with ambitions, hopes and problems that the young reader shares as he or she reads their story. The Brinkers are very poor, but during one eventful winter many wonderful things happen to them.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Black Beauty by Anna Sewell (1877)

Black Beauty by Anna Sewell wasn’t intended as a children’s book; rather, she wrote it for those who owned or worked with horses, “to induce kindness, sympathy, and an understanding treatment of horses.”

A unique feature of the book is that the story is told by the horse; it is, after all, subtitled The Autobiography of a Horse. He’s sensitive and intelligent, sharing his feelings and thoughts as his story unfolds.

Black Beauty was published in 1877 in England, and in 1890 in the U.S. and ever since, has been one of the best-selling children’s books of all time.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett (1905)

A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett has endured as a timeless tale. The story of A Little Princess follows a young girl with a vivid imagination as she faces abandonment at a posh boarding school in London with a cruel headmistress.

The riches-to-rags story was so successful that in 1902, Burnett adapted the story of Sara Crewe into a three-act stage play under the title, A Little Un-Fairy Princess. The novel has since been adapted into several film versions, TV shows, musicals, and other theatrical productions.

. . . . . . . . . .

Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery (1908)

Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery was a great success from the time it was published, and has appealing to generations of readers of all ages and backgrounds sine.

Anne Shirley is a dreamy, imaginative 11-year-old orphan girl mistakenly sent to middle-aged brother and sister Matthew and Marilla Cuthbert, who meant to adopt a boy to help on their farm.

Set in Prince Edward Island, where the author grew up, the original volume and its sequels follow Anne from her arrival in the fictional town of Avonlea, through school, college, marriage, and motherhood.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Girl of the Limberlost by Gene Stratton (1909)

A Girl of the Limberlost was Gene Stratton’s third novel, published in 1909 as a sequel to Freckles (1905), both of which are stories for “children of all ages.” Gene was enchanted by the great outdoors from an early age and was encouraged by her parents to explore her surroundings. Her love of nature served as the foundation for her career as a naturalist, photographer, and writer.

In the course of her early explorations, Gene came upon the Limberlost Swamp near her home in rural Indiana. There she discovered birds, butterflies, and wildflowers that captured her imagination. A 1909 review of the book wrote:

“Here’s a sweet and tender tale which is a welcome addition to the libraries of our young people, as well as delightful reading for older ones. It is a sympathetic story with the ennobling love of nature as its basic thought.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett (1911)

The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett follows the journey of Mary Lennox, a sickly and unloved ten-year-old girl born to wealthy British parents in India.

After a cholera epidemic kills her parents, Mary is sent to England to live with her Uncle Archibald in an isolated, mysterious house. The tale follows the spoiled and sulky young girl as she slowly sheds her sour demeanor after discovering a secret, locked garden on the grounds of her uncle’s manor.

. . . . . . . . . .

Emily of New Moon by L.M. Montgomery (1923)

Emily of New Moon by L.M. Montgomery is the start of a trilogy of novels about Emily Byrd Starr that invites comparison with the beloved Anne of Green Gables series. These books, as is true for many of L.M. Montgomery’s writings, are meant for “children of all ages.”

Legions of readers have been devoted to Anne, while others prefer the more contained Emily, who is grounded in her passionate ambition to become a writer. The Emily trilogy shows her in the act of writing, living, and breathing writing, and working to improve her craft. That single-minded devotion to the art of writing is a rarity in children’s literature.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Little House Series by Laura Ingalls Wilder (1932)

The Little House Series by Laura Ingalls Wilder is an autobiographical series of novels that reflect on the authors life on the American frontier. Though beloved by generations of young readers, they haven’t been without controversy, as we’ll soon discover.

The Ingalls family traveled by covered wagon through Kansas and Minnesota with all that they owned, until finally settling in De Smet, Dakota Territory. The family loved the open spaces of the prairie. They moved around quite a bit, and though it wasn’t an easy life, it gave Laura a rich trove of memories and experiences to draw upon when she began writing.

Wilder (1967–1967) wrote these vivid tales — nine in the Little House series — that immediately appealed to readers of all ages. The books were an immediate critical and popular success, winning numerous awards and making their way into readers’ hearts with their message of endurance, simple living, and love of family.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Rescuers by Margery Sharp (1959)

The Rescuers by British author Margery Sharp launched a series of books starring Miss Bianca, a socialite mouse who assisted animals as well as humans in perilous situations, and fellow mice Bernard and Nils. These well-received children’s novels have had legions of grown-up fans as well, and all told added up to nine books.

Disney adapted the stories to two animated films, The Rescuers (1977) and The Rescuers Down Under (1990). Margery Sharp’s classic tale of pluck, luck, and derring-do is amply and beautifully illustrated by the great Garth Williams.

. . . . . . . . .

I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith (1948)

I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith is the story of Rose and Cassandra Mortmain, two sisters who are part of an eccentric family living in genteel poverty in a crumbling castle in the 1930s. At the time of its publication, Smith was an established playwright, and would later become even better known for the children’s classic, The 101 Dalmatians (1956).

This coming-of-age novel has been beloved by young adults ever since it was published in 1948. Critics were kind as well, as in the words of this original 1948 review:

“Finding out what happens makes rewarding reading. This is a captivating — an enchanting story, bit it is also shrewd commentary on life and art and the complexity of the human heart.”

. . . . . . . . . .

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle (1962)

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle was almost never published. L’Engle reflected, “You can’t name a major publisher who didn’t reject it.” It took just that one publisher to take the chance, and the rest is literary history. It has not only won some of the most prestigious publishing awards, it’s also one of the most frequently banned books of all time.

Best of all, with A Wrinkle in Time, L’Engle become one of the pioneers not only opened a path for more complex children’s literature (think: Harry Potter). Once the book came out, it was widely praised.

. . . . . . . . . .

Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh (1964)

Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh is set in Manhattan’s upper east side, stars 11-year-old Harriet M. Welsch, who wants to be a famous writer when she grows up. To prepare, she keeps a notebook in which she records details of the world around her in minute detail.

Her observations of the people in her life are funny, poignant, and sometimes cruel. When her sixth-grade classmates find and read the contents of her notebook, Harriet’s world turns upside down.

When the book was first published, critical reaction was quite positive. Harriet is relatable and though quite flawed, she’s also evidently lovable and memorable.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Arm of the Starfish by Madeleine L’Engle (1965)

The Arm of the Starfish by Madeleine L’Engle is a tense, well-plotted story of suspense which, while having much to say about basic values and human loyalties, moves to an extraordinary and satisfying conclusion. Young Adam Eddington, a brilliant student specializing in marine biology, secures a summer job as assistant to the world-famous Dr. O’Keefe, who’s laboratory is situated on Gaea, a small island off the coast of Portugal.

Before the plane takes off from Kennedy International Airport, Adam makes the acquaintance of Caroline Cutter, an attractive girl whose father has business interests in Portugal.

Caroline is going to Lisbon, too, but on another airline. Caroline warns Adam inn a hurried and unclear manner against a certain Canon Tallis who, along with a 12-year-old redheaded child, is to be a passenger on Adam’s flight.

. . . . . . . . . .

Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt (1975)

Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt is a remarkable novel about mortality and immortality that rewards young and adult readers alike. Originally intended for middle grade children, it’s a gracefully written story that has resonated with readers of all ages. It explores the idea of eternal life, and its flip side, mortality.

When 10-year-old Winnie Foster inadvertently comes upon the Tuck family, she learns that they became immortal when they drank from a spring on her family’s property.

They tell Winnie how they’ve watched life go by for decades, while they themselves never grow older. Winnie must decide if she’ll keep the Tucks’ secret, and whether she wants to join them on their immortal path.

The post 15 Classic Novels for Middle Grade Readers appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 8, 2024

J. California Cooper, a Unique Voice in Three Genres

J. California Cooper (November 10, 1931 – September 20, 2014) author of plays, novels, and short stories, was admired for her unique voice in all three genres.

Warmth, pathos, and humor blended with pain are her trademarks. Her seven collections of short stories feature the use of dialogue and vernacular, and an unwavering commitment to portraying a diverse array of Black female characters.

Early Life: Paper Dolls and Telling Stories

Joan Cooper was born in Berkeley, California to Joseph and Maxine Rosemary Cooper. Her father was employed in the scrap metal business, and her mother worked as a welder during World War II and then ran a beauty salon.

She had one brother and a sister named Shy Christian. Cooper often portrayed sisters throughout her fiction, usually with either very loving or extremely toxic bonds.

She recalled that when she got her first library card, she checked out so many books from her library and kept them for so long that she had to invent “aliases” to check out more. Cooper said in an interview:

“I was telling stories before I could write. I like to tell stories, and I like to talk to things. If you’ve read fairy tales, you know that everything can talk, from trees to chairs to tables to brooms. So, I grew up thinking that, and I turned it into stories.”

Her many stories are usually written in the first person and have the quality of a folk tale or a moral fable. She was drawn to fairy tales from an early age, both for their imagination, romance, and justice. “Who would think of a pea under a mattress?”

She began writing plays when she was eighteen because her mother took away her beloved paper doll collection. Cooper had always used her paper dolls to bring the stories in her head to life, but her mother said it was time for her to grow up. “Even before I was old enough to write,” she said later, “I was telling stories through paper dolls. I could see life, and I paid attention to it.”

“My mother took them away,” Cooper said in a 1994 interview for The Dallas Morning News. “But the next year I was married and was getting ready to have a baby. She should have left me alone with those paper dolls! But she took them away – and so I began to write stuff out.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Marriage, Name Changes, and Self-Image

Despite exuding joyful radiance in nearly every photograph of her, Cooper grew up insecure. In an interview, she recalled how as a young woman she came across a 1920s dating manual called The Technique of the Love Affair and used its racy instructions to “collect 24 engagement rings because I grew up thinking I was ugly and was never gonna get married.”

It was perhaps this insecurity that led to her dedication to creating “ugly duckling” heroines in her fiction—she wrote multiple stories about women who are not conventionally beautiful, but instead warm, intelligent, and sensitive, and they either eventually find a caring lover or discover fulfillment in supportive friendships and by pursuing their gifts.

Intensely private about her personal life, Cooper only rarely stated that she “was married a couple of times, but they’re dead.” She was a devoted single mother but scandalized those around her by carrying baby Paris in her bicycle basket. She continued writing, always, because she was always observing the people around her.

About her unusual second name, her daughter later said, “There was a Tennessee Williams… so [my mother] thought, ‘Why shouldn’t there be a California Cooper?’”

Early Success in Theatre

Little is known about Cooper’s educational background. She described herself as a “perpetual dropout” and worked a colorful array of jobs to support herself and her daughter, Paris Williams. She worked as a manicurist, waitress, secretary, a loan officer, and even joined the Teamsters and drove buses and trucks in Alaska.

Cooper wrote that what most inspired her to write was “the Bible and life,” and that her characters often came to her after listening to musicians such as Dinah Washington and Erroll Garner. She also loved classical music: “I can never play Rachmaninoff without getting a character, somebody who’s talking.”

Perhaps because of the many years of her “talking” paper dolls and her keen observance of human behavior, playwriting came naturally to Cooper. Her plays were not produced until years later when the grown Paris took them to the Black Repertory Theater in Berkeley. In 1978 Cooper won the Black Playwright of the Year Award for her play Strangers and wrote seventeen plays in all.

Alice Walker, who had recently become the first African American woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for her novel The Color Purple, was invited by Paris to see an early production of one of Cooper’s plays and later shared it with friends at the University of California, Berkeley.

“I said, ‘I don’t publish plays. Do you have any stories?’ asked Walker, and Cooper replied, ‘Well, I’ll go find some.’” Cooper stated later that if not for Walker’s encouragement “this stuff could still be sitting in the drawer.” Walker also suggested fiction “because it was easier to get paid,” recalled Paris. Cooper’s first collection of short stories, A Piece of Mine, was published in 1984 through Walker’s company, Wild Trees Press.

Walker wrote of Cooper’s literary voice, “Her style is deceptively simple and direct, and the vale of tears in which her characters reside is never so deep that a rich chuckle at a foolish person’s foolishness cannot be heard.”

Fellow playwright and poet Ntozake Shange wrote that “Her stories, parables, and monologues take flight with truths about being alive, rhythm of folks at ease by the creek and the pool table, songs of love and remorse, syncopated, galloping, and beguiling genuine.”

Homemade Love, Cooper’s second collection of short stories, won her an American Book Award in 1989 and one of the stories, “Funny Valentines,” was later adapted into a film starring .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“I don’t know how to write … I just do it”: Craft and ThemesCooper insisted she could only write her first drafts in long hand and not on a typewriter or computer: “The minute I step in front of something mechanical,” she wrote in The Word: Black Writers Talk About the Transformative Power of Reading and Writing, “my characters disappear because they don’t like it.”

Her love of music and skill as a playwright undoubtedly led to Cooper’s attention to speech. Her sentences are usually short and staccato, and she often changes the spelling of a word so it suits a character’s speech or the rhythm of a phrase. An unconventional use of punctuation is a prominent feature in her fiction “My people don’t live in periods; they live in exclamation points.”

Staccato sentences and straightforward storytelling wrought stories that are gripping, ebullient, and emotional, and have connected with many readers. In her 1994 interview with Cooper, Joyce Saenz Harris wrote “Her occasional public readings are vivid events marked by a natural flair for drama, and she can hold a cafeteria full of restless high schoolers spellbound.”

The element of her fiction that is most frequently noted is her unique storytelling voice and her use of first-person narration. Some readers and critics have disliked her use of dialect, criticizing it as too “folksy,” old-fashioned, or repetitive. Her stories have also drawn criticism for being too didactic and moralizing.

Writing with a Social Conscience

Cooper was a deeply religious woman, and many of her stories take the form of a moral fable, and there are usually clearly defined villains and heroines.

She frequently depicted grim topics such as domestic violence and sexual assault, and usually made sure that (like in a fable or fairytale) the wrongdoers were punished for their crimes. A wife-beater comes to a suitable end in the memorably titled short story “He Was a Man! (But He Did Himself Wrong!)”

Despite her devout religious faith, Cooper strove for realism in her writing and did not shy away from her characters using profanity, or from depicting their tumultuous sex lives: “If the word fits, that’s what they say. And also sex … that’s life, and that’s the problem they’re having, so I can’t leave sex out because they don’t.”

Cooper began writing fiction in the wake of the Civil Rights movement and third-wave feminism, and she was fully aware that, despite a certain amount of progress, Black women remained extremely vulnerable in America.

Her friend and mentor Walker introduced the term Womanist as a more specific way to address the issues and systemic injustices that all—but particularly working class and Black—women face.

The definition of love that Cooper wove throughout her stories was a combination of dignity, emotional enrichment, mutual respect, and commitment. She was both earthy and tender when describing the passionate natures of her heroines, and many of them come to the realization that they are stronger than the injustice that surrounds them and that they are more courageous than the man in their lives.

The majority of Cooper’s work was published during the booming consumerism of the 1980s and ‘90s, and throughout her fiction she shone a spotlight on the poor and oppressed, particularly on the descendants of slaves as they strove to create a safe community, such as in her novels In Search of Satisfaction and Wake of the Wind.

A recurrent theme throughout her work is the importance of sharing your good fortune with others and the corrupting influence of money.

She illuminated systemic poverty with an unflinching lens and a great understanding of Black social history; Cooper didn’t just want equality, dignity, and happiness for Black people but for all downtrodden people. She offered a compassionate, community-oriented, and Gospel-based approach to racial reconciliation, drawn from the Black oral tradition.

Cooper appeared to disapprove of the casual nature of modern dating and emphasized the importance of a Black woman being able to respect herself, either by remaining single or by being monogamously married. She wrote, “Love is born in respect,” and of her character Futila in “As Time Goes By,” that “She should’a never let him know that she loved him more than she loved herself!”

This emphasis on a woman’s autonomy, dignity, and self-worth independent of a man was a far less judgmental stance than that taken by supporters of the white-centric purity culture movement, which gained popularity during the HIV/AIDS Epidemic.

While Cooper may have been “old-fashioned” as some critics derided, she also displayed nuance and showed particular sympathy to disastrously matched couples seeking solace from toxic and abusive marriages, such as in her novella The Eye of the Beholder included in Wild Stars Seeking Midnight Suns.

Later Life

Although she was never as lauded as her near contemporary, Toni Morrison, Cooper developed a devoted following of readers and was the recipient of many distinguished writing awards, including the James Baldwin Writing Award and the Literary Lion Award from the American Library Association.

Reviewer Melissa Walker wrote in the Chicago Tribune that “Cooper’s stories dramatize the wages of sin and the rewards of patience, as well as the occasional sweet taste of revenge in a moral universe in which justice operated independently of social and economic forces.”

In her 1994 interview, Harris aptly described the enduring appeal of Cooper’s body of work: “In Ms. Cooper’s universe, evil is punished, ‘integrity always triumphs,’ and the eternal verities – God, love, family, justice –stand in stark contrast to human foolishness and conceit.”

Though describing herself as a semi-recluse in her later years, the insatiable storyteller was zestful, delightfully opinionated, and entirely herself to the end. She moved from Texas to Seattle to be with her daughter but occasionally showed up at book readings, spunky and always able to make her audiences both laugh and think.

“I tell young people a book is a mind, it’s somebody’s brain you’re meeting. The author of the book is preparing you for life. A book is a world, a book is a friend, that’s why people love books. A book is a marvelous thing. It’s a person between covers.”

Death and Legacy

J. California Cooper passed away on September 20, 2014, at the age of eighty-two. In her L.A. Times obituary, Alice Walker said:

“She wanted to show the richness of the lives of people who often don’t have much exposure. You may not know that or care or see it … but in fact that person on the corner has a real deep life somewhere. Her work was to expose that so you can feel connected.”

With her rich understanding of human nature and the Black experience, her keen sense of justice, and infinite empathy, Cooper’s writing is ripe for rediscovery and could offer much to today’s readers, perhaps especially to supporters of #MeToo and the campaign, which honors the memory of Black women and girls lost to police violence.

Cooper’s voice fell silent, but her characters are still talking between the covers of their books, and they had plenty to say.

“I tell people: You’d better watch what’s going on around you,” Cooper wrote, “Because this is life.”

Contributed by Katharine Armbrester, who graduated from the MFA creative writing program at the Mississippi University for Women in 2022. She is a devotee of Flannery O’Connor and Margaret Atwood, and loves periodicals, history, and writing.

More about J California CooperNovels

Family (1991)In Search of Satisfaction (1994)The Wake of The Wind (1998)Some People, Some Other Place (2004)Short Story Collections

A Piece of Mine (1984)Homemade Love (1986)Some Soul to Keep (1987)The Matter is Life (1991)Some Love, Some Pain, Sometime (1995)The Future Has a Past (2000)Wild Stars Seeking Midnight Suns (2006)More information and sources

University Digital Conservancy Interview in The Dallas Morning News Art Sanctuary Interview (video) Obituary in the Los Angeles TimesThe post J. California Cooper, a Unique Voice in Three Genres appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 5, 2024

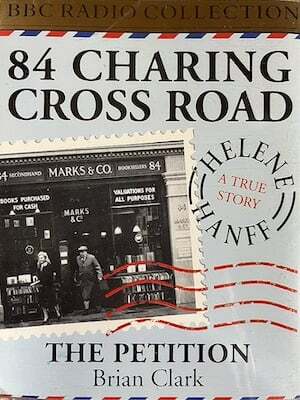

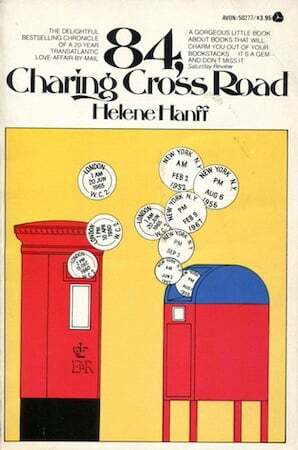

Film and Stage Adaptations of 84 Charing Cross Road

In the decades after 84, Charing Cross Road by Helene Hanff was published, it was adapted for the stage, film, and radio. The adaptations brought the book to new audiences and were incredibly popular, although they received mixed critical reviews.

Written by American author and playwright Helene Hanff, 84 Charing Cross Road is an eclectic, endearing collection of her twenty-year trans-Atlantic correspondence with London antiquarian bookshop Marks & Co. on Charing Cross Road. The book was a cult success in both America and the UK.

Today, the film is still available to watch on major streaming channels, and the play is regularly performed by theatre companies on both sides of the Atlantic.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The book that started it allIn 1949, struggling New York playwright Helene Hanff wrote her first letter to London bookshop Marks & Co, after seeing one of their advertisements in the New York Times Saturday Review of Literature. She enclosed a list of books that she was looking for, explaining that:

“The phrase ‘antiquarian booksellers’ scares me somewhat, as I equate ‘antique’ with expensive. I am a poor writer with an antiquarian taste in books and all the things I want are impossible to get over here except in very expensive rare editions, or in Barnes & Noble’s grimy, marked-up school-boy copies…”

This letter was the start of twenty years of correspondence between Helene and Frank Doel, the chief buyer and manager of Marks & Co. Over time the letters grew to include other members of staff at the shop, as well as Frank’s wife Nora, and a business arrangement grew into a deep friendship.

Helene sent gifts, holiday packages, and food parcels to the shop, both to thank them for their efforts in finding her books and to help alleviate the worst of British post-war rationing. The letters covered subjects as diverse as John Donne, the perfect recipe for Yorkshire puddings, baseball, and the coronation of Elizabeth II.

Although Helene wanted desperately to travel to the UK, her financial circumstances precluded it, and Frank died unexpectedly from peritonitis in 1969. It was only then that Helene thought of gathering their correspondence into a book. 84 Charing Cross Road was published in 1970, and its success finally enabled Helene to make the journey to visit London and the now-closed bookshop.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

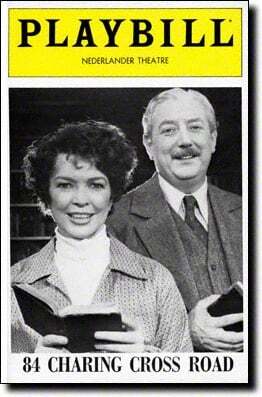

84 Charing Cross Road – the playIn 1980, British theatre director James Roose-Evans adapted the book for the stage, with Helene’s help. Ironically, given that she was a playwright herself, it was the only thing of hers that was ever produced for the theatre. It premiered at the Salisbury Playhouse in 1981, before transferring to the West End and later Broadway.

It played at the Ambassadors Theatre in London from November 1981 to April 1983 and starred Rosemary Leach as Helene and David Swift as Frank. Helene was in London at the time and attended the opening night. Reviews were universally good, and Irving Wardle wrote in The Times that the poignancy of the occasion seemed like “the end of a fairytale.”

The play then toured nationally in the UK, and and Bill Gaunt took over the lead roles. The tender, bittersweet comedy was a hit with audiences, and its appeal lasted long after the first run finished. It returned to the Salisbury Playhouse in February 2015, with Clive Francis and Janie Dee as Frank and Helene, and then in 2018 began another nationwide tour at the Cambridge Arts Theatre, with Clive Francis starring again alongside Hollywood actress Stefanie Powers as Helene.

The Broadway production, however, was not so successful. It opened in December 1982 at the Nederlander Theater, with Ellen Burstyn and Joseph Maher in the lead roles, but the reviews on this side of the Atlantic were mixed. Frank Rich wrote in the New York Times:

“After seeing Charing Cross Road, the tiny divertissement that opened at the Nederlander Theater last night, you don’t feel as if you’ve been to the theater, but to afternoon tea … [it] is a staged reading that’s been tricked-up into a Broadway production by the casting of a star and by the erection of an imposing Oliver Smith set … 84 Charing Cross Road is high-minded but resolutely nonintellectual — a play for those who get more pleasure out of owning handsome old books than reading them.”

It ran for 96 performances before closing.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

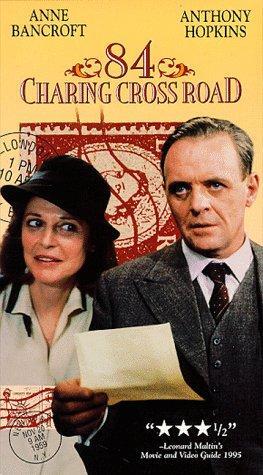

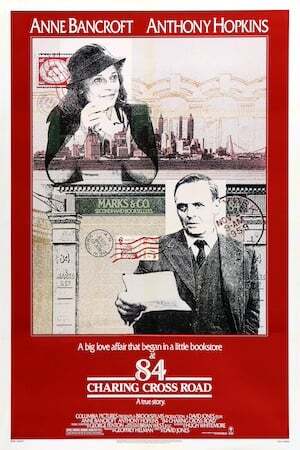

84 Charing Cross Road – the filmIn the mid-1980s, production began on a film adaptation of the book. The screenplay was adapted by Hugh Whitemore from the play script (not directly from the book itself), and the film was directed by David Hugh Jones.

The all-star cast included Anne Bancroft as Helene, Anthony Hopkins as Frank, and Judi Dench as Frank’s wife Nora, and Anne Bancroft’s husband Mel Brooks was also an executive producer.

It was co-produced in Britain and the US by Brooksfilms and Columbia Pictures and was shot on location in both London and New York with two entirely separate production teams. This is reflected in the closing credits, when a split screen shows Helene Hanff in New York and Frank Doel in London, and the crews for the two cities scroll side by side.

The London settings included Buckingham Palace, Trafalgar Square, St James’s, Westminster, Soho Square, White Hart Lane in Tottenham, and Richmond, while famous New York settings included Central Park, Madison Avenue, and St Thomas Church. Most of the interior sequences were filmed at Lee International Studios and Shepperton Studios in Surrey.

The film received mixed critical reviews. Variety described it as “an appealing film on several counts, one of the most notable being Anne Bancroft’s fantastic performance in the leading role. She brings Helene Hanff alive in all her dimensions, in the process creating one of her most memorable characterizations.”

Gene Siskel wrote in the Chicago Tribune , “Years ago, 84 Charing Cross Road would have been called “a woman’s picture” or a “perfect matinee.” But it’s that and more. It should be irresistible to anyone able to appreciate the goodness of its spirit and its spirited characters…”

In the New York Times, however, Vincent Canby called it “a movie guaranteed to put all teeth on edge…a movie of such unrelieved gentleness that it makes one long to head for Schrafft’s for a double-gin martini straight up and a stack of cinnamon toast from which the crusts have been removed.”

For the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert wrote: “The film is based on a hit London and New York play, which was based on a best-selling book. Given the thin and unlikely subject matter, that already is a series of miracles. And yet some people are pushovers for this material. I should know. I read the book and I saw the play and now I am reviewing the movie, and I still don’t think the basic idea is sound…”

Despite these few lukewarm reviews, the film was a success at the box office, taking over a million dollars in the US. It also appeared at the 1987 São Paulo International Film Festival, the 1988 Munich Film Festival, and the 1987 Moscow International Film Festival, where Anthony Hopkins won an award for Best Actor and David Hugh Jones was nominated for the Golden Prize for direction.

Anne Bancroft won a Best Leading Actress BAFTA award in 1988 for her portrayal of Helene, while Judi Dench was nominated for Best Supporting Actress, and Hugh Whitemore was nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay. In 1989, Helene Hanff and Hugh Whitemore shared the USC Scripter Award for the screenplay.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

84 Charing Cross Road – on the radioThe book has also been adapted for British radio several times. It was first broadcast on BBC Radio 3 in 1976, in an adaptation by Virginia Browns that starred as Helene and as Frank.

James Roose-Evans, having already written the play script, adapted it again for radio in 1992; this production starred Frank Finlay and Miriam Karlin. A further production in 2007 starred Gillian Anderson and Denis Lawson and was broadcast on Christmas Day on BBC Radio 4.

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

The post Film and Stage Adaptations of 84 Charing Cross Road appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

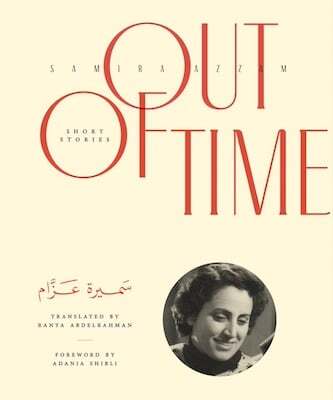

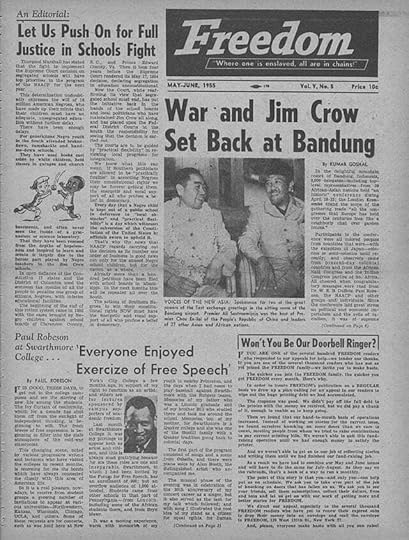

Samira Azzam, Journalist, Broadcaster, and Short Story Writer

Samira Azzam (September 13, 1927 – August 8, 1967) was a journalist and broadcaster who left her mark on Palestinian literature. Her numerous short stories reflected the Palestinian experience of the 1950s and 1960s.

She was born in Acre (in what was then the Palestinian Mandate and today is Israel). Acre is located on the Mediterranean coast, often known locally as Akko.

Had she lived today, she might have been a social media influencer, as she started writing reviews and essays for the newspaper Filistin, signing them “A Girl from the Coast” while a still a teen. Azzam was apparently a dedicated student: she became a teacher at the age of sixteen.

A Life on the Move

While she was born into a middle-class family of Orthodox Christians, Azzam had great insight into the lives of people forced to make difficult choices due to poverty.

When Azzam was about twenty-one, in 1948, she and her family went to Lebanon as a result of Israel’s forced displacement of about half the population of Palestine, an event known as the Nakba, or Catastrophe. The rest of her short life would be deeply affected, like the lives of the people around her, by the conflicts and political upheavals of the region.

As a writer and social critic, Azzam took part in the literary community of Beirut, Lebanon’s capital. She wrote short stories. As Ranya Abdelrahman explains in the introduction to her translation of a collection of Azzam’s stories, Out of Time, Palestinian literature of this era focused on short stories because they could be published inexpensively and read aloud on the radio.

Azzam’s professional life had her moving about. Two years after her family relocated to Lebanon, Azzam went to Iraq. There she taught and may have been the headmistress of a girls school. It was also while she was in Iraq that Azzam began working for the Near East Asia Broadcasting Company where she wrote for the program “Women’s Corner.”

Azzam moved back and forth from Beirut to Iraq in the late 1950s, as regime changes in Iraq affected her ability to work as a broadcaster from Baghdad. In Beirut she was the host of a popular morning show.

A Writer of Short Stories

While in Iraq, Azzam wrote for an Iraqi newspaper, and published two collections of short stories in the 1950s, Little Things (1954) and The Big Shadow (1956), and began translating works from English to Arabic. Her translations included works by George Bernard Shaw and Pearl S. Buck.

In 1959, Azzam married Adib Yousef Hasan and together they briefly lived in Iraq before, due to the political climate, moving the back to Beirut, where she began publishing and wrote for two women’s magazines—Sawt Al-Mar`a (Women’s Voice) and Dunia Al-Mar`a (Women’s World).

She also worked for the Franklin Institution for Translation – work that continued bringing English-language works by writers such as John Steinbeck and Edith Wharton to Arabic. In 1960, she published another collection of short stories — And Other Stories.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Out Of TimeHer short story collection The Clock and the Man was published in 1963. The title story of that volume has become one of Azzam’s best-known works, partly because of an essay by Adania Shibli, author of the much-translated novel Minor Detail (2017), about the impact of that story on her own sense of her Palestinian identity.

Explaining that it was one of the few Palestinian stories to escape being cut from the school curriculum by Israeli censors, Shibli, who was born in 1974, describes her surprise at reading it in her primary school. It is a simple story about a man who takes it upon himself to act as an alarm clock, knocking on doors to wake all those in his neighborhood who work for a certain company and thus must catch an early train.

The narrator eventually learns the reason for the man’s behavior: his son was killed trying to catch the morning train and he wants to save others from that fate. For Shibli, however (whose essay “Out of Time” appears at the beginning of the Out of Time anthology), this short story was evidence of a world she had never known. She wondered:

“Were there once Palestinian employees who commuted to work by train? Was there a train station? Was there once a train whistling in Palestine? Was there ever once a normal life in Palestine? So where is it now, and why has it vanished?”

Last Years

Through the 1960s, Azzam began working on her first novel, Sinai Without Borders. Azzam helped found a Palestinian radio station and increased her political activism in this period. In June of 1967, she was a co-founder of the Committee of Arab Ladies.

The organization was created to aid Palestinian refugees fleeing territories captured by Israel in the Arab-Israeli or Six-Day War. Israel’s victory in that war was said to be a great shock to Azzam.

She destroyed the manuscript for her novel, and she died of a heart attack a few weeks later on August 8, 1967 at thirty-nine years old. Following Azzam’s death, two more collections of her stories were published: The Festival Through the Western Window(1971) and Echoes (2000).

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

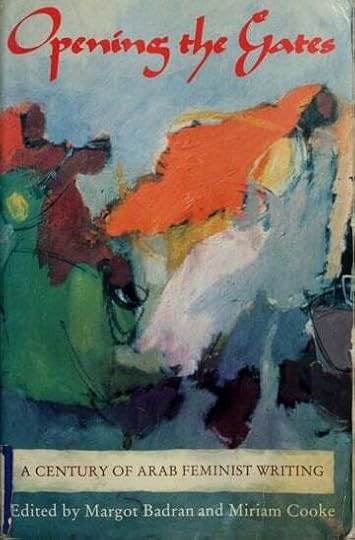

Narrative TechniquesIn 2022 ArabLit published of Out of Time, a collection of thirty-one of Azzam’s stories. Ranya Abdelrahman translated the collection. Prior to this, only a handful of English versions of Azzam’s stories were available. Before they were only available in anthologies such as Arab Women Writers (2005) and Opening the Gates: A Century of Arab Feminist Writing (1990).

Unfortunately, the stories in Out of Time, which clearly span Azzam’s career, are updated as to their original publication.

The stories in Out of Time as well as those in the other anthologies are a pleasure to read. Truly short (some as little as two pages), they present a range of experiences. Many of the stories have a first-person plural narrator, a technique that creates the sense of a communal voice.

For example, “The Inheritance” begins, “We have to confess that Abu Naseef’s family was impatient for him to die,” while “The Aunt’s Marriage” opens with “It was only natural, since Umm (Mother) Youssef was visiting, for us to loosen our tongues and delve more freely into the affairs of neighbors, both near and far.”

And yet another example, “The Roc (a legendary bird of prey) Flew Over Shahraban,” starts with “Slowly, we raised our heads as hellish cries echoed in our ears, and we looked up in awe and fear.”

Women With Difficult Choices

Many of Azzam’s stories portray women faced with difficult choices. One of those stories, oft-cited in essays about Azzam, is “Her Story.” Narrated by a woman forced into prostitution to survive, the story offers the impassioned tale of an orphaned girl tricked, seduced, and exploited who begs her younger brother, filled with shame after he discovers her occupation, not to kill her for both their sakes.

But not all her stories portray women in brutal conditions. “A Silken Dream” tells the story of Souad, a young woman who longs to buy a dress she can’t afford to impress her new suitor’s family the first time she meets them. When he assures her that his clothes are cheap, “her face relaxed, and contentment made its way back to her features. It seemed to her that she had never seen Mansour more manly, or more elegant than he was at that moment in his cheap khaki shirt.”

Psychological Insights

Many of Azzam’s stories portray with powerful psychological insight the struggle by both men and women to maintain pride in the face of poverty and oppression. “No Harm Intended,” a two-pager, is another of those narrated by “we,” in this case the daughter of a family who owns a candy store.

She describes how she and her brother mock a man who comes begging for sweets, how they are reprimanded by their father who pities the man, and how, after their father prepares a little gift for the beggar to celebrate Eid, the beggar refuses the gift and never again returns to their shop.

Some commentators explain Azzam’s lack of visibility today by claiming that her stories were not political enough at a time when Palestinians were grappling with one political crisis after another. And yet in stories like “Zagharid” (a word referring to the trilling ululation made during weddings and other celebrations), Azzam portrays the pain of a woman in Jaffa unable, due to political restrictions, to travel to Beirut to make her own zagharid at her only son’s wedding.

A Modern Perspective

Some of Azzam’s stories are quite modern in their outlook. “A Virgin Continent,” translated by Arab Women Writers, is five pages long and written only in dialogue between a woman and her male partner.

As they discuss prior relationships, resentments and jealousies escalate and the woman notes that her partner needs to see himself as “the discoverer of a virgin continent” in imagining her as having had no history before she became involved with him.

In yet another story, “The Passenger,” a very urban and accomplished woman, awaiting a flight in the Beirut airport, is overcome by the grief of a peasant family bidding farewell to a relative about to become the first person in their family to travel on a plane as he prepares to board one for the first time in his life.

This story skillfully exhibits Azzam’s ability to cross class lines and embrace the emotional world of her fellow Palestinians, whatever their circumstances.

Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.

Further reading

Khalil-Habib, Nejmeh. “Samira Azzam (1926-1967): Memory of the Lost Land.” (undated)

Hakeem, Mazen, trans. “Samira Azzam: A Profile from the Archives.” Jadaliyya 27 April 2014.

Fawzy, Ibrahim. “Samira Azzam: A Palestinian Scheherazade Out of the Shadows.” Rowayat, A Literary Journal, #6. (undated)

Jalal, Maan. “Palestinian author Samira Azzam’s short stories translated into English for new book.” The National, March 21, 2023.

More about Samira AzzamCollections of Short Stories

Little Things (1954)Big Shadows (1956)And Other Stories (1960)The Clock and the Man (1963)The Festival Through the Western Window (1971)Echoes (2000)Full Texts

Arab Lit – Out of Time: The Collected Short Stories of Samira Azzam Bread of Sacrifice Tears from a Glass Eye Man and His Alarm ClockMore Information

Interactive Encyclopedia of The Palestine QuestionThe post Samira Azzam, Journalist, Broadcaster, and Short Story Writer appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 26, 2024

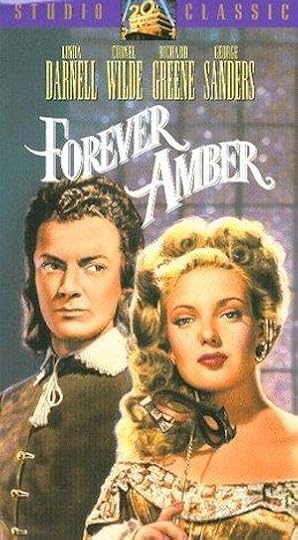

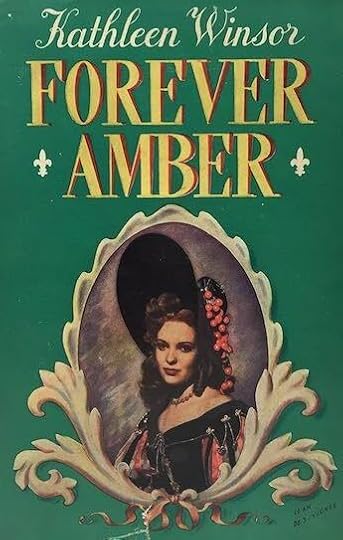

Forever Amber by Kathleen Winsor (1944), the Banned Bestseller

Forever Amber by Kathleen Winsor (1944) tells the sprawling story of Amber St. Clair, a beauty who cunningly ascends the class structure of Restoration-era England. After a humble upbringing, sixteen-year-old Amber’s encounter with a troupe of traveling soldiers turns into her ticket out of the countryside – and her journey of social advancement begins.

Amber’s fictional narrative is interwoven with true historic facts of the English Restoration; she is born of circumstances resulting from the English Civil War, becomes a survivor of the plague, and witnesses the Great Fire of London.

Amber meets a vast array of characters from all the English classes, her adopted farmer parents, the mischievous highwayman Black Jack Mallard, her true love royalist Lord Bruce Carlton, and King Charles II. These encounters amount to a sweeping portrait of the English Restoration.

On her nearly 1,000-page path to the throne, Amber leaves a trail of scandal in her wake — theft, abortion, and sexual desire. She climbs up the ranks of 17th-century society as the mistress or wife of ever richer and more important men, all the while loving the one man she could never have.

Forever Amber scandalized and enthralled the reading audience. Fourteen American states, as well as all of Australia, banned the book upon release, citing claims of obscenity. Nevertheless, the novel skyrocketed in popularity, and in 1947 was made into a film.

Publishers’ synopses of Forever Amber

From the Chicago Review Press edition (2000): “Abandoned, pregnant, and penniless on the teeming streets of London, 16-year-old Amber St. Clare manages, by using her wits, beauty, and courage, to climb to the highest position a woman could achieve in Restoration England—that of favorite mistress of the Merry Monarch, Charles II.

From whores and highwaymen to courtiers and noblemen, from events such as the Great Plague and the Fire of London to the intimate passions of ordinary—and extraordinary—men and women, Amber experiences it all. But throughout her trials and escapades, she remains, in her heart, true to the one man she really loves the one man she can never have.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The 1947 film adaptation of Forever Amber

. . . . . . . . . .

From the Lexington Leader, (KY) October 1, 1944: The Macmillan Company will publish its big fall book Oct. 16, and you can mark the occasion as a red-letter day in your reading. The book is Forever Amber, a novel by Kathleen Winsor.

When I said “big” I was not thinking of size, but of quality, sales, and popularity. But the novel is far from short in length, running close to a thousand pages. Unless I miss my guess, Forever Amber, a story of turbulent Restoration England, will outstrip that other Macmillan story, Gone With The Wind, in every department of public appeal. I think it a much better story.

Kathleen Winsor is really Mrs. Robert John Herwig, wife of a Marine on duty in the South Pacific. (Those who read the sports pages will recall that Herwig was an all-American gridder at the University of California back in 1936 and 1937 and an all-American basketballer that former year.)

She graduated from the University of California in 1938 and her only writing for publications prior to this novel were football feature articles for the Oakland Tribune in 1937, the year that California went to the Rose Bowl.

Macmillan reports that Miss Winsor’s novel had its inception in a term paper which her husband did on the death of Charles II. The young bride picked up one of the books he was using for reference, became fascinated with the Restoration, and got the idea for a novel. She worked as a receptionist on the Oakland paper for about six months in hopes of becoming a reporter but gave up and started writing the story which turned out as Forever Amber.

You would never guess it from the novel nor from looking at her, but Miss Winsor is a plodding methodic worker. In setting out on her tremendous novel she outlined a definite schedule and stayed with it.

She took one week off every month, and even when she was trailing along with her husband from camp to camp her manuscript was a constant companion. If she were obliged to miss a day, she made up for it, and in the final stages was busy eight hours a day, seven days a week.

Miss Winsor kept tabs on how much time she spent on this novel. She wrote six complete drafts. This amounted to 9,241 pages or 2,310,250 words. She used 1,303 hours for reading and researching, 380 hours indexing her notes, and 3,284 hours writing the book, a total of 4,967 long hours on the whole job spread over about five years.

Macmillan paid the usual advance for a novel amounting to about a dollar an hour for the time spent on this particular one. The first printing which goes on sale Oct. 16, is 150,000 copies at three dollars each.

Miss Annie Laurie Williams, noted for big deals involving movie rights to the books, got hold of Miss Winsor soon after the manuscript reached Macmillan. That was before the record-breaking $125,000 MGM novel award.

But Miss Williams did not submit Forever Amber in the contest, because she believed that the movies would pay considerably more for the picture rights than a mere $125,000!

. . . . . . . . . . .

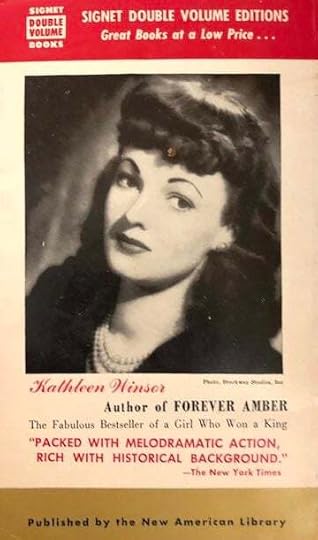

Kathleen Winsor was just twenty-five when Forever Amber was published; it would remain her most successful work. This is from the back cover of a later edition of the book, in paperback

A 1944 reviews of Forever AmberFrom the original review in The Rutherford Courier, Oct. 13, 1944: This is the Gone With the Wind of the Restoration period of Old England. Instead of Scarlett, the heroine’s name is Amber. Rhett Butler, here, becomes Bruce, Lord Carlton. The scene, instead of the Southland, is all England, from the debtor’s pens in Newgate prison to the bedroom of King Charles II.

The theme is–well, just to make every page as magnetically interesting as possible. The result is a book that one finds hard to put down, though every one of its 900-odd pages.

Like Gone With The Wind, Forever Amber is the story of a beautiful yet resourceful and determined woman who gets everything she wants except, in the end, the man she really loves. Amber is the daughter of high blood, but this is a secret that only the reader knows, and that Amber never learns.

Reared in a peasant household, she meets Lord Carlton as he, with other Cavaliers, passes through her tiny town en route back to London with Charles II. From the violent episode of her first meeting with Bruce, she never forgets him. She accompanies him to London but is left alone when he sets off privateering.

Amber, through a succession of marriages, “keepings,” and responses to the King’s night-time summons, eventually becomes the king’s mistress, a duchess, and perhaps the most influential woman in the Court, and hence all of England. Ruthless and scheming, she stops at nothing – and if there is any experience a woman ever had which Amber missed, it was omitted from the book surely unintentionally.

But the frank and violent action and the sex of this book are merely what make it run fast. Underneath there is good solid writing in the vivid picture of old England as it must have been in those times, with all its squalor and ignorance as well as extravagance and luxury.

The account of the bubonic plague epidemic in London is a truly sharp scene. Lord Carlton had the plague too, and Amber nursed him back to life, and in doing so caught the plague herself. This part of the story is told at length and is realistic detail, and it is a tribute to the author’s skill that interest never lags even here.

The author, Kathleen Winsor, until she wrote this book had never written anything for publication except a few newspaper articles.

She is the wife of Lieut. Robert John Herwig, All-American football center from California U. in 1936 and 1937. They met in college; she became interested in the subject of Charles II when her husband had to write a term paper on the subject, and this book is the result.

The publishers state that they intended to give the book unprecedented promotion, and this can hardly help being a best-seller, perhaps THE best-seller of the 1940s. It is a natural for the movies. And there’s no justice unless Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh get the leading roles. In technicolor. — R.C.L.

. . . . . . . . . .

First edition cover

. . . . . . . . . .

Further reading about Forever Amber by Kathleen Winsor

Original review in the Atlantic (December 1944) Review in Austenprose 1947 film adaptation on Rotten TomatoesThe post Forever Amber by Kathleen Winsor (1944), the Banned Bestseller appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 22, 2024

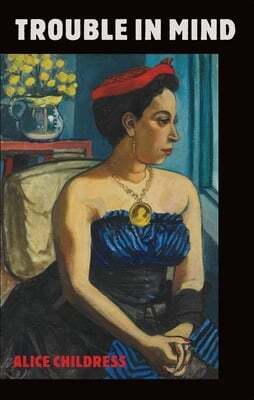

Alice Childress, Author of Trouble in Mind

Playwright and novelist Alice Childress (October 12, 1916 – August 14, 1994) was a prolific and influential contributor to American theater and letters throughout the second half of the twentieth century. Her first full-length play, Trouble in Mind, premiered in 1955 and won an Obie.

Another play, Wedding Band, was shown on network television in 1974 (though network affiliates in several southern states refused to carry it).

None of this would have mattered to Childress who said, “I never was ever interested in being the first woman to do anything. I always felt that I should be the 50th or the 100th. Women were kept out of everything.”

She saw being “first” not so much as a triumph but as an indictment of a society that had prevented women from achieving the things she did before she did them.

Despite her many accomplishments as a playwright, however, she is best known today as the author of A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ But a Sandwich, a groundbreaking young adult novel about a 13-year-old heroin addict that was highly praised—and the subject of a 1982 Supreme Court case, Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico.

Early Life

Childress was born Alice Herndon in Charleston, South Carolina, on October 12, 1916 (though she would later shave years off her age by claiming a birth year of 1917 and even 1920). Her father, Alonzo Herrington, worked in insurance, and her mother, Florence White, was a seamstress.

After her parents split up (some accounts say when she was five; others when she was nine), Childress was sent to Harlem to be raised by her maternal grandmother, Eliza Campbell. Childress later said her relationship with Campbell was among the most fortunate things in her life.

Remarkable Grandmother