Nava Atlas's Blog, page 14

December 13, 2023

Praisesong for the Widow by Paule Marshall (1983)

Praisesong for the Widow is widely regarded as Paule Marshall’s most eloquent statement of the need for African Americans to understand and embrace their heritage even as they pursue equality and success.

Praisesong was initially published in 1983 and reissued in 2021 in a handsome edition by McSweeney’s as the second volume in its Diaspora series.

Praisesong is the first of Marshall’s novels to feature a middle-class Black American woman at its center, a woman who experiences what was also a defining moment in Paule Marshall’s own life: the Big Drum ceremony on the tiny Caribbean island of Carriacou.

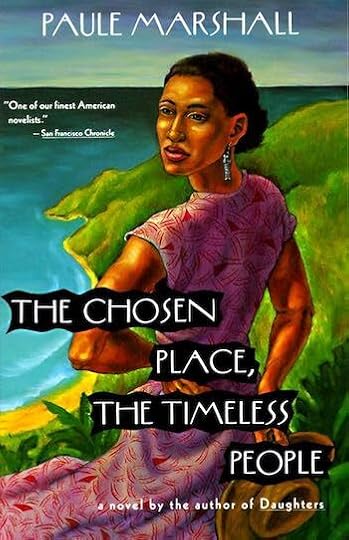

The witnessing of the Big Drum ceremony, recounted in Triangular Road, Marshall’s 2009 memoir, allowed her to break through writer’s block to write The Chosen Place, The Timeless People (1969). It constitutes the climactic moment in Praisesong for the Widow.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Paule Marshall

. . . . . . . . . .

Compared with Marshall’s earlier novel, The Chosen Place, The Timeless People, which has a broad array of characters with complex interrelationships and an intricate plot that unfolds over a period of months, the plot of Praisesong is a simple one.

Avey Williams Johnson, the protagonist, is a middle-aged African American widow with adult children. She lives in a large and comfortable suburban home in prosperous North White Plains, a suburb of New York City. A supervisor in the state motor vehicle department, she dresses well, eats well, and enjoys all the pleasures of a hard-won upper-middle-class lifestyle.

Avey embarks on an expensive Caribbean cruise on the Bianca (white) Pride with two friends, also widows, and six pieces of matched luggage filled with her well-chosen wardrobe, but a few days into the cruise she succumbs to her feeling of increasing unease and decides, for reasons she cannot explain, to jump ship off the coast of the island of Grenada. She plans to fly back to New York as soon as possible.

A few days earlier, she had dreamt about her great-aunt, whom Avey visited on Tatem Island in North Carolina during childhood summers. The old woman told stories of the landing of enslaved people. Avey is disturbed by the dream, but she doesn’t connect it to her sudden impulse to abandon her cruise and the ship.

Arrival on Grenada

Avey arrives in Grenada to find “a crowd of perhaps two hundred men, women and children … clearly from the more respectable element on the island” who pay her no attention as they stream onto a waiting line of schooners and sloops. She learns that there are no more flights to New York until late the next day; her taxi driver tells her that the people she saw boarding boats were headed for Carriacou, an island “so small scarcely anybody has ever heard of it.”

Avey checks into the best tourist hotel in Grenada and the next day she goes for a walk along the beach. Finding herself disoriented and lost, she encounters an old man, Lebert Joseph, who is about to embark on the same expedition to Carriacou as the people she saw the day before.

Although Avey insists she is a tourist, the old man recognizes something in her that she has yet to discover in herself and he eventually overcomes her resistance and convinces her to join him on the trip to Carriacou to witness the Big Drum ceremony.

Journey to Carriacou

Despite her objections, Avey delays her flight again and makes the journey to Carriacou with a boatload of people, including two old women who nurse her through a bout of vomiting that she attributes to seasickness, but which readers will recognize as a metaphorical purging.

Once on the island of Carriacou, she is initially disappointed when she sees the “large denuded dirt yard” where the dance is to be held. But as the dance proceeds, women from different “nations,” or ethnic groups, take their turns to dance. Avey begins to “feel the reverberation” of the dancers’ powerful tread.

Eventually, “…an arm made up of many arms” reaches out to draw her in and soon she is also “doing the flatfooted glide and stomp with aplomb … in the company of these strangers who had become one and the same with people in Tatem.” Later, Lebert Johnson and his daughter Rosalie tell Avey that after watching the way she danced and after considering her height and the way she carries herself, they have determined that she is descended from the Arada people.

Avey has a history, and the costs of her success

By the time she heads back to New York, Avey knows what she is going to do: she will pass this history along to the “young, bright, fiercely articulate token few for whom her generation had worked the two and three jobs,” sell her house in North White Plains, and restore her great aunt’s house.

She makes plans to turn it into a place where she can bring her grandchildren to tell them the stories of their people.

An immensely readable and straightforward story, Praisesong for the Widow takes place over just a couple of days. Yet Marshall incorporates so much into this account: Avey and her husband Jerome’s endless work to move from a cramped and cold apartment in Brooklyn to the comfortable home in North White Plains; the costs of that striving to her marriage and relationship with her children; the brutality of the racism that always surrounds them as she and her husband watch helplessly (in this era before cell phone cameras) from the window of their Brooklyn apartment as police drag a Black man from his car and beat him until he bleeds; the joyous childhood outings among her Harlem neighbors setting out for a summer picnic.

We see the yearning of Avey’s youngest child, Marion, to share her struggle for equality and the history of their people with her mother and Avey’s refusal to acknowledge that history for fear of losing what she and her husband have worked so hard to attain.

. . . . . . . . .

The Chosen Place, the Timeless People

. . . . . . . . .

Much of this story is mirrored in Marshall’s own life. Though she wasn’t on a cruise, in 1962 she was living on the island of Grenada, having gone there as a single mother intending to write after receiving a Guggenheim grant.

Despite her preparations for the opportunity—stacks of research—and the ideal conditions—Grenada’s beauty and the money that allowed her to hire a housekeeper, a cook, and a nanny, and rent a house with large rooms and tall windows—she found herself suffering, for the first time in her life, from a paralyzing case of writer’s block.

When a couple of friends insisted that she make the trip to Carriacou (a smaller island two hours away by schooner) to witness The Big Drum/Nation Dance, she reluctantly agreed to go.

“The drums,” she wrote, “were nothing more than a few hollowed-out logs with a drumhead of goatskin. The drummers themselves were elderly men who couldn’t possibly, it seemed, open their stiff, work-swollen hands to beat a drum.”

The men drum throughout the night as aged women dance. “Who we is, oui!” the dance caller cries. “Where we’s from in truth! Our true-true nation: Manding, Arada, Cromanti, Congo, Yoruba, Igbo, Chamba.”

As Marshall watched the dance, she recalled James Weldon Johnson’s description of the Ring Shout in his memoir of growing up in segregated Florida, Along This Way. Inspired, Marshall joined the dancers, and when she returned to her study the next morning, she packed up her steno pads of research notes and locked them away.

It was only then that she was able to begin writing the novel that would become The Chosen Place, the Timeless People:

“… finally understanding, fledgling that I still was, that as a fiction writer, a novelist, a storyteller, a fabulist … my responsibility first and foremost was to the story … the old verities of people, plot and place; a story that if honestly told and well-crafted would resonate with the historical truths contained in the steno pads.”

Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.

You may also enjoy Lynne’s piece, Inspiration from Classic Caribbean Women Writers.

. . . . . . . . . .

The post Praisesong for the Widow by Paule Marshall (1983) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 11, 2023

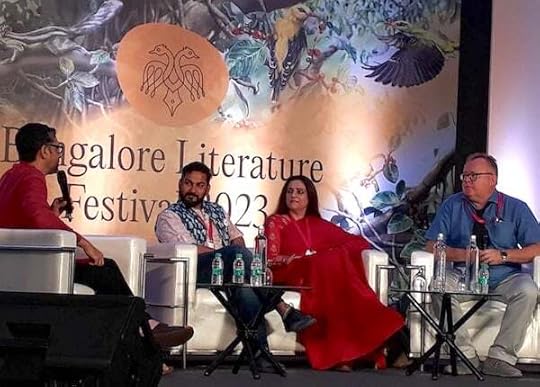

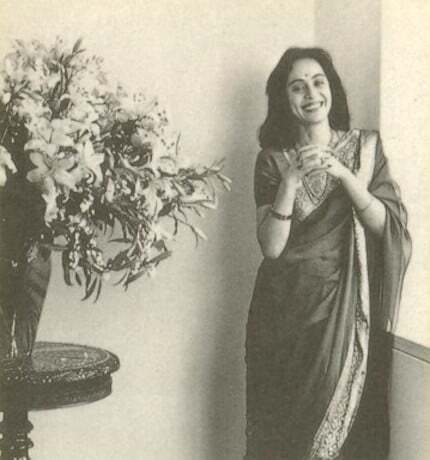

Bangalore Literature Festival 2023 – Observations and Inspiration

It’s such a wonderful feeling to be part of the Bangalore Literature Festival, to know that you’re among kindred spirits — devoted book lovers. Here are some observations and personal reflections on Bangalore Literature Festival 2023.

We are all smiling at one other and find ourselves sharing thoughts with whomever is sitting next to you. It’s enchanting being at the sessions and as the authors talk about their books, you feel that you want to read each and every one of them.

And more than ever, you’re thinking of that book sitting inside your head waiting to be written and feeling inspired to give it a go.

. . . . . . . . . .

Our correspondent Melanie Kumar

at Bangalore Literature Festival 2023

. . . . . . . . . .

From the Festival organizers:

“The Bangalore Literature Festival celebrates the creative spirit of Bengaluru and commemorates the literary diversity it offers, bringing it in conversation with the best minds in the world of literature. The 2023 edition of the Bangalore Literature Festival is a two-day literary extravaganza that will bring together some of the biggest names in literature – within and outside India.

The objective of the Bangalore Literature Festival is to put together a literary experience that brings writers – both established and aspiring, readers, publishers, students and young professionals and other stakeholders of the city together on a common platform and create a compelling space for engaging and thought-provoking discussions on literature and life.”

Stories from Everywhere (parts 1, 2, & 3): The Moderator, Nilanjan Choudhury, is brilliant in the way he draws in the authors and makes them speak about their stories. These are an eclectic bunch of writers drawn from across the country who have employed the short story format, which according to Nilanjan encapsulates brevity at its best.

The Kashmiri author who has translated from her uncle Harikrishna Kaul’s stories says that the stories come out of one square mile of space and deal with abandonment, alienation, repression of female sexuality and could be termed every person’s story.

The author who has been translated from the Telugu comes from an agricultural family of Dalits (oppressed class and lowest in India’s caste hierarchy) is an activist and feminist and hence is able to look at gender and caste through a different lens.

Another author in the panel says that she opted for a different genre, involving fantasy elements, which she wrote based on her family stories. She says that the emotional impact of these stories, poured out from her in fiction form, over a decade. She did not stress too much about how they would link together in an anthology.

The author from Orissa was different in that she is a serving bureaucrat. Coming from a family where both parents wrote in Oriya, she says that she is better known for her writing than her profession. She says that she thinks that stories are love affairs and she wants to be in one all the time.

The Manipuri author hailing from a conflict zone says that she needs to tell stories that combine genres and also reflect the reality of the society that she lives in. Her very pertinent observation is about how she feels a connection with all the authors in the panel, as if she knows them all from their stories.That to me is the magic of storytelling.

Not Above the Law Session: The journalist/author Manoj Mitta is known to do painstaking research and his latest book on caste brings out the structural inequality of judgements in India and the impunity with which upper castes get away with crimes including rape. The denial of justice to marginalized communities is the thrust of his findings and one can feel the empathy in his arguments.

The others on the panel are lawyers and academics and, in their views, occasionally sound like how they may be speaking in the courts. This panel leaves one with a feeling of disappointment, as they don’t seem to hold out much hope for ordinary citizens in an authoritarian regime.

Meter and Magic, Poetry Reading Session: This is a different kind of session, as the poets come up and perform, some doing so with a great deal of aplomb. Some of the interesting lines that I jotted down:

“Spotless in lifeless.”

“Their hold is real, much more than words reveal.”

“I protest metaphors of love … I protest the question, ‘why do I write’?”

“Your strength is in your silence, mine in my words.”

“Weighed down by the cargo of the past … a room that is not weighed down by yesterday’s conversations.”

“What is the point of it all?”

“What you call reality, is virtual reality?”

“Why are words like this?”

“What if I had no skin, what if I am the barometer?”

“Poetry silenced–died of a heart attack.”

Winners and runners-up of the Deodar Prize: A new prize was instituted this year in partnership with the Bangalore Literature Festival, The Bombay Literary Magazine and Hammock.

Winner: Srividya Tadepalli for “Funeral for a Demon.”

Runners-Up: Samruddhi Ghodgaonkar- “Bats of Paradise.”

Ratul Ghosh: “Ants.”

Plotting Emotion; the Alchemy of Words: The Moderator, Udayan Mitra of Harper Collins, said that his panel had four of the most exciting authors to read.

A first-time woman author in her non-fiction book based on interviews said that she discovered that politics in India is not about binaries and that she wrote keeping these complexities in mind.

The doctor author in the panel said that she started with writing for children and then short stories. She had no idea about publishing and her then Editor had no notion about Coorg, the place that she first located her stories in.

A senior author cum academic spoke about her early struggles when she had to deal with rejections and learnt to pare down her words till Faber finally accepted her novel. She also spoke that whilst being at publicity events was unavoidable, her greatest joy lay in sitting in a room and writing and that she never wrote with a readership in mind but because she had something to say.

A U.S.-based academic and author, spoke about how he tries to blur the lines between fiction and non-fiction and how each day of one’s life is a little story.

Ad Man/Mad Man: Prahlad Kakkar, who had a very successful career in advertising launched his autobiography at BLF 2023. The interview was irreverent, and the book promises to be a laugh riot. “Learn to laugh at yourself,” is the advice that he doled out to the audience.

I Hate Love Stories: The most interesting thing that emerged from this panel is the changing landscape of the characterization of an Indian woman. A sports journalist author spoke about how the right mentor can lift up your writing, while the opposite can happen too.

Another author in this panel lamented on how authoritarianism is crushing society and how digital connectivity has made one realize the similarities that exist across the world. An author who has written about a bisexual woman spoke about how writing this book helped her to have this difficult conversation with her own orientation.

One author spoke about how she liked to challenge herself by bringing in aspects like French philosophy or magical realism. One interesting comment on character formation brought in this line “wanted to kill the Alpha male forever.”

The authors also spoke about creating grey women characters and even having a woman protagonist, who is disliked — quite a change from the earlier days of creating women who had to be liked by all, just as it is in real life.

Mirch Masala: On the Indian food trail: All the authors here seemed to agree that authenticity in cooking is a fraught term, as recipes travel from borders to kitchens and across states too and evolve in the process. Another interesting focus was on how foods that are used in India presently like red chilies and potatoes are actually imports.

Creating Worlds: Curating Art and Literature: The curators in this panel, narrated their experiences with bringing forth aspects of India, which is a land of stories and telling these stories employing different formats.

What emerged also was the need to showcase the raw edges of art, without the need for camouflage and application of an inter-disciplinary approach. There was also a valid suggestion to not let festival panels become TikTok memes by restricting the time to just half an hour.

Listen, I Will Tell You: This session involved a free-flowing chat with award-winning Author and Academic, the 87-year-old, Chandrashekhara Kambar with fellow academic and author, Basavaraj Kalgudi. Kambar read excerpts from his novel with a great deal of emotion.

Fields of Fire: Conflicts around the world are discussed, with retired diplomats and an academician in conversation with a journalist. Understandably, with two retired diplomats and an academic on the panel, a lot of heat was generated on this panel.

The conflict in Gaza seemed to hold sway with Israel coming in for a huge amount of criticism over its pounding of Palestine’s civilian population. The international community has no fig leaf to protect itself from the flouting of all established laws and norms.

The Secret History, On Writing Fiction: Lead on by an accomplished Moderator, the feminist publisher, Urvashi Butalia, this panel served up many insights. The vulnerabilities of women who write and their courage came up for discussion.

Also of importance was mention of international award-winning writers like Salman Rushdie, Arundhati Roy, and Kiran Desai, who helped to gain acceptance for writing Indian English that no longer needed foot-noting to explain local nuances and expressions.

Sakina’s Kiss: Kannada author and English translator interviewed- An informative session on the conversation between a successful Kannada novel being translated into English and the process that actually creates two different novels.

The Tharoor Connection: Author/politician in conversation with his sister. This session had the audience lapping up every word, as author/diplomat and Member of Parliament, Shashi Tharoor, chatted with his sister, Smitha, about their love for the English language and the written word.

They claimed that their father was the original inventor of the popular Wordle game, as he threw clues at them on long car journeys. The hall was jam-packed with people squatting on the floor and on the aisle, making Shashi the rock-star author of BLF 2023.

Hindi bole toh bole ke ganwar hai: Translating as “If I speak Hindi. I am considered a bumpkin.” A singing performance in Hindi by Kavish Seth, with funny and philosophical lyrics and a reminder of the diversity of India with its many languages of which English is just one.

Contributed by Melanie P. Kumar: Melanie is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

The post Bangalore Literature Festival 2023 – Observations and Inspiration appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Bangalore Literary Festival 2023 — Observations and Inspiration

It’s such a wonderful feeling to be part of the Bangalore Literary Festival, to know that you’re among kindred spirits — devoted book lovers. Here are some observations and personal reflections on Bangalore Literary Festival 2023.

We are all smiling at one other and find ourselves sharing thoughts with whomever is sitting next to you. It’s enchanting being at the sessions and as the authors talk about their books. You feel that you want to read each and every one of them.

And more than ever, you’re thinking of that book sitting inside your head waiting to be written and feeling inspired to give it a go.

. . . . . . . . . .

Our correspondent Melanie Kumar

at Bangalore Literary Festival 2023

. . . . . . . . . .

From the Festival organizers:

“The Bangalore Literature Festival celebrates the creative spirit of Bengaluru and commemorates the literary diversity it offers, bringing it in conversation with the best minds in the world of literature. The 2023 edition of the Bangalore Literature Festival is a two-day literary extravaganza that will bring together some of the biggest names in literature – within and outside India.

The objective of the Bangalore Literature Festival is to put together a literary experience that brings writers – both established and aspiring, readers, publishers, students and young professionals and other stakeholders of the city together on a common platform and create a compelling space for engaging and thought-provoking discussions on literature and life.”

Stories from Everywhere (parts 1, 2, & 3): The Moderator, Nilanjan Choudhury, is brilliant in the way he draws in the authors and makes them speak about their stories. These are an eclectic bunch of writers drawn from across the country who have employed the short story format, which according to Nilanjan encapsulates brevity at its best.

The Kashmiri author who has translated from her uncle Harikrishna Kaul’s stories says that the stories come out of one square mile of space and deal with abandonment, alienation, repression of female sexuality and could be termed every person’s story.

The author who has been translated from the Telugu comes from an agricultural family of Dalits (oppressed class and lowest in India’s caste hierarchy) is an activist and feminist and hence is able to look at gender and caste through a different lens.

Another author in the panel says that she opted for a different genre, involving fantasy elements, which she wrote based on her family stories. She says that the emotional impact of these stories, poured out from her in fiction form, over a decade. She did not stress too much about how they would link together in an anthology.

The author from Orissa was different in that she is a serving bureaucrat. Coming from a family where both parents wrote in Oriya, she says that she is better known for her writing than her profession. She says that she thinks that stories are love affairs and she wants to be in one all the time.

The Manipuri author hailing from a conflict zone says that she needs to tell stories that combine genres and also reflect the reality of the society that she lives in. Her very pertinent observation is about how she feels a connection with all the authors in the panel, as if she knows them all from their stories.That to me is the magic of storytelling.

Not Above the Law Session: The journalist/author Manoj Mitta is known to do painstaking research and his latest book on caste brings out the structural inequality of judgements in India and the impunity with which upper castes get away with crimes including rape. The denial of justice to marginalized communities is the thrust of his findings and one can feel the empathy in his arguments.

The others on the panel are lawyers and academics and, in their views, occasionally sound like how they may be speaking in the courts. This panel leaves one with a feeling of disappointment, as they don’t seem to hold out much hope for ordinary citizens in an authoritarian regime.

Meter and Magic, Poetry Reading Session: This is a different kind of session, as the poets come up and perform, some doing so with a great deal of aplomb. Some of the interesting lines that I jotted down:

“Spotless in lifeless.”

“Their hold is real, much more than words reveal.”

“I protest metaphors of love … I protest the question, ‘why do I write’?”

“Your strength is in your silence, mine in my words.”

“Weighed down by the cargo of the past … a room that is not weighed down by yesterday’s conversations.”

“What is the point of it all?”

“What you call reality, is virtual reality?”

“Why are words like this?”

“What if I had no skin, what if I am the barometer?”

“Poetry silenced–died of a heart attack.”

Winners and runners-up of the Deodar Prize: A new prize was instituted this year in partnership with the Bangalore Literature Festival, The Bombay Literary Magazine and Hammock.

Winner: Srividya Tadepalli for “Funeral for a Demon.”

Runners-Up: Samruddhi Ghodgaonkar- “Bats of Paradise.”

Ratul Ghosh: “Ants.”

Plotting Emotion; the Alchemy of Words: The Moderator, Udayan Mitra of Harper Collins, said that his panel had four of the most exciting authors to read.

A first-time woman author in her non-fiction book based on interviews said that she discovered that politics in India is not about binaries and that she wrote keeping these complexities in mind.

The doctor author in the panel said that she started with writing for children and then short stories. She had no idea about publishing and her then Editor had no notion about Coorg, the place that she first located her stories in.

A senior author cum academic spoke about her early struggles when she had to deal with rejections and learnt to pare down her words till Faber finally accepted her novel. She also spoke that whilst being at publicity events was unavoidable, her greatest joy lay in sitting in a room and writing and that she never wrote with a readership in mind but because she had something to say.

A U.S.-based academic and author, spoke about how he tries to blur the lines between fiction and non-fiction and how each day of one’s life is a little story.

Ad Man/Mad Man: Prahlad Kakkar, who had a very successful career in advertising launched his autobiography at BLF 2023. The interview was irreverent, and the book promises to be a laugh riot. “Learn to laugh at yourself,” is the advice that he doled out to the audience.

I Hate Love Stories: The most interesting thing that emerged from this panel is the changing landscape of the characterization of an Indian woman. A sports journalist author spoke about how the right mentor can lift up your writing, while the opposite can happen too.

Another author in this panel lamented on how authoritarianism is crushing society and how digital connectivity has made one realize the similarities that exist across the world. An author who has written about a bisexual woman spoke about how writing this book helped her to have this difficult conversation with her own orientation.

One author spoke about how she liked to challenge herself by bringing in aspects like French philosophy or magical realism. One interesting comment on character formation brought in this line “wanted to kill the Alpha male forever.”

The authors also spoke about creating grey women characters and even having a woman protagonist, who is disliked — quite a change from the earlier days of creating women who had to be liked by all, just as is it real life/

“Merch Masala” and “On the Indian food trail”: All the authors here seemed to agree on authenticity in cooking is a fraught term, as recipes travel from borders to kitchens and across states too and evolve in the process. Another interesting focus was on how foods that are used in India presently like red chilies and potatoes are actually imports.

Creating Worlds: Curating Art and Literature: The curators in this panel, narrated their experiences with bringing forth aspects of India, which is a land of stories and telling these stories employing different formats.

What emerged also was the need to showcase the raw edges of art, without the need for camouflage and application of an inter-disciplinary approach. There was also a valid suggestion to not let festival panels become TikTok memes by restricting the time to just half an hour.

Listen, I Will Tell You: This session involved a free-flowing chat with award-winning Author and Academic, the 87-year-old, Chandrashekhara Kambar with fellow academic and author, Basavaraj Kalgudi. Kambar read excerpts from his novel with a great deal of emotion.

Fields of Fire: Conflicts around the world are discussed, with retired diplomats and an academician in conversation with a journalist. Understandably, with two retired diplomats and an academic on the panel, a lot of heat was generated on this panel.

The conflict in Gaza seemed to hold sway with Israel coming in for a huge amount of criticism over their pounding of Palestine’s civilian population. The international community has no fig leaf to protect themselves from the flouting of all established laws and norms.

The Secret History, On Writing Fiction: Lead on by an accomplished Moderator, the feminist publisher, Urvashi Butalia, this panel served up many insights. The vulnerabilities of women who write and their courage came up for discussion.

Also of importance was mention of international award-winning writers like Salman Rushdie, Arundhati Roy, and Kiran Desai, who helped to gain acceptance for writing Indian English that no longer needed foot-noting to explain local nuances and expressions.

Sakina’s Kiss: Kannada author and English translator interviewed- An informative session on the conversation between a successful Kannada novel being translated into English and the process that actually creates two different novels.

The Tharoor Connection: Author/politician in conversation with his sister. This session had the audience lapping up every word, as author/diplomat and Member of Parliament, Shashi Tharoor, chatted with his sister, Smitha, about their love for the English language and the written word.

They claimed that their father was the original inventor of the popular Wordle game, as he threw clues at them on long car journeys. The hall was jam-packed with people squatting on the floor and on the aisle, making Shashi the rock-star author of BLF 2023.

Hindi bole toh bole ke ganwar hai: Translating as “If I speak Hindi. I am considered a bumpkin.” A singing performance in Hindi by Kavish Seth, with funny and philosophical lyrics and a reminder of the diversity of India with its many languages of which English is just one.

Contributed by Melanie P. Kumar: Melanie is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

The post Bangalore Literary Festival 2023 — Observations and Inspiration appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 10, 2023

South African Author Dalene Matthee: A Daughter’s Tribute

South African author Dalene Matthee (1938 – 2005) was best known for her four “Forest novels” presenting stories of the Cape Knysna Forest and its inhabitants. In 2023, I had the good fortune of interviewing Hilary Matthee, one of Dalene Matthee’s three daughters, for an issue of the Afrikaans magazine Taalgenoot.

Matthee’s writings have been translated into multiple languages, including French, German, Icelandic, and English. Matthee would usually translate the first versions of her work into English, believing that it was important to make sure the emotion came across in a “reserved” language.

In 1970, Matthee published her debut children’s novel The Twelve o’ Clock Stick. She published a collection of short stories next, The Judas Goat, in 1982. Several of her works have been adapted to film, including Circles in a Forest (1989), Fiela’s Child (1988 and 2019), and Dreamforest.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

An interview with Hilary Matthee, daughter of Dalene MattheeParts of this interview were translated into English, and then kept in the original language for the piece. Presented here is a reworked version of the original interview.

Dalene Matthee began writing children’s stories for broadcast on radio, sometime after getting married at 18, says Hilary. “Later, she started writing short stories for Sarie and Huisgenoot to fill in the family’s income.”

“She wanted to write a short story like Jack London’s To Build a Fire. Charles Kingsley’s Water-babies also had a large impact on her, and she considered it a large metaphysical work.”

Dalene wrote a series for the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), but it was rejected by the television network. “She reworked the two series’ into books, which became Petronella van Aarde, Mayor and A House for Nadia.”

At this time, Matthee found a tree in the middle of the forest – here, the Circles in a Forest that would form the inspiration for the first of four Forest Novels. According to Hilary, Matthee would call the first Forest novel her attempt to write a “glorified fairy tale.”

Hilary remembers sitting around the kitchen table, asking her mother what her favorite characters might have gotten up to today. For 15 years, Hilary joined Matthee assisting in research and odd jobs.

“Dalene always said that writing is an incredibly lonely job; nobody can help you, and you have to be very disciplined,” says Hilary. “Her study had to be organized and clean.”

Matthee also refused the presence of alcohol anywhere near her study. “She used to say that she doesn’t get driven by whims like many other writers, getting up to write in the middle of the night with a glass of wine in hand.”

She wrote her first three forest books by hand, says Hilary. “It had to be a yellow pencil, inlined classroom books. After this, she typed out the manuscript.”

The manuscript for Circles in a Forest was typed on a portable Olivetti typewriter in the days before computers, Hilary notes.

After publishers rejected the original title (Where the Loerie Cries), they settled on Circles in a Forest instead. Loeries, for their call, are also named “go-away birds” — the Knysna Lourie is a prominent feature in the forest that formed much of her inspiration. The Circles in a Forest hiking trail is named in Matthee’s honor, with a memorial to her located at one of her favorite spots in the forest.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Dalene Matthee’s “Forest Novels”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Dalene Matthee had once studied music; at Graaff-Reinet she spent time as a music teacher. She also happened to be an avid golfer. Hilary says that her mother never touched a piano again after writing Circles in a Forest – the association between ivory keys and elephants, one would guess.

“Dalene’s research would take an incredible amount of time, up to three years for one book,” Hilary explained.

Fiela’s Child published in 1985, tells the story of Benjamin Koemoetie, an Afrikaner boy adopted by a coloured woman from the Cape, first portrayed by actress Shaleen Surtie-Richards for the 1988 film.

Hilary remembers the process would start with interviews. The interviews would be recorded, after which Dalene would start making notes.

“She spent a lot of time in the Cape Archives, museums, old newspaper clippings, ship records, and letters.” Some of her research took her abroad, such as a trip to Italy (for The Mulberry Forest), or Mauritius (for Pieternella, Daughter of Eva).

The Mulberry Forest (1987) is set in the 1800s, when immigrants from Italy settle in the Knysna Forest in what soon becomes a struggle for their survival against very unfamiliar elements.

“She said research is like gambling: you just can’t stop. Because you never know quite when you’ll find the piece of information that’s worth gold.”

Facts mattered: “Dalene wanted to be known as a responsible researcher. She checked all sources to make sure, because if someone could doubt one fact, they could easily cast doubt on the entire novel.”

The same opinion carried into her personal life. “She could handle a lot, but you could never lie to her. She would always say truth is stronger than lies – and the truth plays a huge role in her stories.”

She never considered herself “famous,” even though her work sold millions of copies internationally. According to Hilary, she once remarked when asked about her fame: “What does it help having the world at my feet, but losing my soul – when my soul is what I’m writing with?”

Dalene donated her life’s work and notes to the National Afrikaans Literary Museum and Research Centre (NALN) in Bloemfontein.

Today, the Circles in a Forest Hiking Trail is a monument to her memory – one of Dalene’s favourite places, and the creative spring that gave rise to many of her thoughts. “It takes you to the heart of the indigenous forest, going past Outeniqua–yellowwood trees that are hundreds of years old.”

Further reading

Dalene Matthee Official Website Visit Knysna: Dalene Matthee Hiking TrailContributed by Alex Jansen, a journalist, author, and proofreader. He has written for a variety of publications and websites, with a radar calibrated for gothic, gonzo and the weird. His features, posts, articles and interviews have been published in People Magazine, ATKV Taalgenoot, LitNet, The Citizen, Funds for Writers, and The South African, among other publications.

The post South African Author Dalene Matthee: A Daughter’s Tribute appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 3, 2023

Dalene Matthee’s South African “Forest Novels”

A lifelong advocate for environmental rights, South African author Dalene Matthee is renowned for her “Forest novels” series. These four books, originally written in Afrikaans, present narratives set in the country’s Knysna Forests.

Dalene Matthee’s (1938 – 2005) books have achieved international acclaim. They have been translated into multiple languages, including English, Icelandic, French, and German. More than a million copies of her works have sold.

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Dalene Mathee

Photo: Uitgewers Publishers

. . . . . . . . . . .

Dalene Matthee, born Dalena Scott, was born in Riversdale in the Southern Cape (South Africa). She studied at the local high school, from which she graduated in 1957.

That same year, Dalene married Larius Matthee. Her studies continued in Oudtshoorn, where she studied music until she moved to the Holy Cross Convent in Graff-Reinet.

Matthee published her first novel in 1970, a children’s story called Die Twaalfuur-stokkie (which translates to English as The Twelve o’ Clock Stick).

This debut wasn’t translated until 1991, with Matthee in charge of the first translation of her work into English. She called English “beautifully reserved” in an interview for The Daily News, saying that she found it important to translate the emotion from one language to another.

In 1982, Matthee published a short story collection called The Judas Goat (Afrikaans: Die Judasbok) and a novel titled A House for Nadia (in Afrikaans: `n Huis vir Nadia). She also wrote short stories for many local magazines, including Huisgenoot and Vrouekeur.

Dalene Matthee’s lifelong love of the Knysna Forest inspired the series of four Forest novels: Circles in a Forest, Fiela’s Child, The Mulberry Forest, and Dream Forest.

The first, Circles in a Forest, was published in 1984. After years of painstaking research in archives and libraries, it launched the series that reflected her lifelong love for the forest and its inhabitants.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Circles in a Forest (1984)

Circles in a Forest is a story of conservation, following the life of a woodcutter named Saul Barnard. An outcast from his community, he heads into the forest and gets to know the legendary Old Foot – an elephant roaming the forest on the verge of being destroyed.

According to the book’s description, “Matthee focuses on conservation and strongly speaks out against the reckless destruction of the indigenous forest.” Matthee was known for her intensive research, even providing a map of Saul’s route through the forest.

The book’s title is drawn from one of Matthee’s personal experiences. Unsure what to write about, she took a walk through the forest; when she stopped at circles on a walking trail, she also had the core thoughts of the novel.

The book was adapted to film in 1989, starring Ian Bannen, Arnold Vosloo, and Judi Trott.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Fiela’s Child (1985)

Fiela’s Child is the second of the Forest novels, starting with the story of Fiela Komoetie who adopts an Afrikaner boy named Benjamin.

Soon the interracial adoption begins a legal standoff, where Fiela is placed on trial and put against an opposing white family – who are convinced that Benjamin is their son.

The book’s tagline is a good description of its storyline: “God forgives many things, but God never forgives us the wrong we do to a child.” Lives are torn apart when Benjamin is seized and forced to live with the van Rooyen family, where he is never quite at home.

Fiela’s Child was adapted to film in 1988, and again in 2019.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Mulberry Forest (1989)

The Mulberry Forest continues the story of the forest’s inhabitants, telling the tale of immigrant mulberry farmers establishing a colony in the middle of the forest setting. This novel introduces the character of Silas Miggel.

Things don’t go as planned when the mulberry trees refuse to grow in harsh conditions. The story becomes a fight for survival.

Matthee said that she chose the name Silas Miggel over several days – ultimately choosing the name from the Bible, like many forest inhabitants of the time would have done. The name Silas, she said, translated to “of the forest.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Dream Forest (2003)

Dream Forest is the last book in the series, written two years before the author’s passing. In this book, nature conservation and the preservation of natural resources remain important themes – this time, expressed as a romance that plays out amidst the Knysna forest setting.

The novel follows its heroine, Karoliena Kapp, a beautiful young woman who knows the forest better than anyone.

Karoliena is soon married off to Johannes, a well-to-do man from the city – but she soon discovers that she hates the thought of leaving the forest and everything she knows behind. Karoliena makes a daring escape, fleeing back into the Knysna forest.

This final novel in the series was, like its predecessors, adapted to film, marking South Africa’s film entry for the 2021 Oscars.

. . . . . . . . . .

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . .

Matthee died in 2005. She had donated her life’s work and papers to the National Afrikaans Literary Museum and Research Centre (NALN).

Her efforts made such an impact that a Dalene Matthee Memorial dedicated to her memory is situated in the Knysa Forest. Also located there is the Dalene Matthee Big Tree – one of the oldest and largest trees still found in this area.

The walking trail in Knysna is also named for her first forest novel, following much of her story’s locations.

With the Forest books, Dalene Matthee forever changed the way people view the Knysna forest, having spent a lifetime dedicated to telling stories that delve deep into nature and human consciousness.

You may also enjoy South African Author Dalene Mathee: A Daughter’s Tribute.

Contributed by Alex Jansen, a journalist, author, and proofreader. He has written for a variety of publications and websites, with a radar calibrated for gothic, gonzo and the weird. His features, posts, articles and interviews have been published in People Magazine, ATKV Taalgenoot, LitNet, The Citizen, Funds for Writers, and The South African, among other publications.

The post Dalene Matthee’s South African “Forest Novels” appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Dalene Matthee’s South African “Forest Books” Novels

A lifelong advocate for environmental rights, South African author Dalene Matthee is renowned for her “Forest books” series. These four novels, originally written in Afrikaans, present narratives set in the country’s Knysna Forests.

Dalene Matthee’s (1938 – 2005) books have achieved international acclaim. They have been translated into multiple languages, including English, Icelandic, French, and German. More than a million copies of her works have sold.

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Dalene Mathee

Photo: Uitgewers Publishers

. . . . . . . . . . .

Dalene Matthee, born Dalena Scott, was born in Riversdale in the Southern Cape (South Africa). She studied at the local high school, from which she graduated in 1957.

That same year, Dalene married Larius Matthee. Her studies continued in Oudtshoorn, where she studied music until she moved to the Holy Cross Convent in Graff-Reinet.

Matthee published her first novel in 1970, a children’s story called Die Twaalfuur-stokkie (which translates to English as The Twelve o’ Clock Stick).

This debut wasn’t translated until 1991, with Matthee in charge of the first translation of her work into English. She called English “beautifully reserved” in an interview for The Daily News, saying that she found it important to translate the emotion from one language to another.

In 1982, Matthee published a short story collection called The Judas Goat (Afrikaans: Die Judasbok) and a novel titled A House for Nadia (in Afrikaans: `n Huis vir Nadia). She also wrote short stories for many local magazines, including Huisgenoot and Vrouekeur.

Dalene Matthee’s lifelong love of the Knysna Forest inspired the series of four Forest novels: Circles in a Forest, Fiela’s Child, The Mulberry Forest, and Dream Forest.

The first, Circles in a Forest, was published in 1984. After years of painstaking research in archives and libraries, it launched the series that reflected her lifelong love for the forest and its inhabitants.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Circles in a Forest (1984)

Circles in a Forest is a story of conservation, following the life of a woodcutter named Saul Barnard. An outcast from his community, he heads into the forest and gets to know the legendary Old Foot – an elephant roaming the forest on the verge of being destroyed.

According to the book’s description, “Matthee focuses on conservation and strongly speaks out against the reckless destruction of the indigenous forest.” Matthee was known for her intensive research, even providing a map of Saul’s route through the forest.

The book’s title is drawn from one of Matthee’s personal experiences. Unsure what to write about, she took a walk through the forest; when she stopped at circles on a walking trail, she also had the core thoughts of the novel.

The book was adapted to film in 1989, starring Ian Bannen, Arnold Vosloo, and Judi Trott.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Fiela’s Child (1985)

Fiela’s Child is the second of the Forest novels, starting with the story of Fiela Komoetie who adopts an Afrikaner boy named Benjamin.

Soon the interracial adoption begins a legal standoff, where Fiela is placed on trial and put against an opposing white family – who are convinced that Benjamin is their son.

The book’s tagline is a good description of its storyline: “God forgives many things, but God never forgives us the wrong we do to a child.” Lives are torn apart when Benjamin is seized and forced to live with the van Rooyen family, where he is never quite at home.

Fiela’s Child was adapted to film in 1988, and again in 2019.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Mulberry Forest (1989)

The Mulberry Forest continues the story of the forest’s inhabitants, telling the tale of immigrant mulberry farmers establishing a colony in the middle of the forest setting. This novel introduces the character of Silas Miggel.

Things don’t go as planned when the mulberry trees refuse to grow in harsh conditions. The story becomes a fight for survival.

Matthee said that she chose the name Silas Miggel over several days – ultimately choosing the name from the Bible, like many forest inhabitants of the time would have done. The name Silas, she said, translated to “of the forest.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Dream Forest (2003)

Dream Forest is the last book in the series, written two years before the author’s passing. In this book, nature conservation and the preservation of natural resources remain important themes – this time, expressed as a romance that plays out amidst the Knysna forest setting.

The novel follows its heroine, Karoliena Kapp, a beautiful young woman who knows the forest better than anyone.

Karoliena is soon married off to Johannes, a well-to-do man from the city – but she soon discovers that she hates the thought of leaving the forest and everything she knows behind. Karoliena makes a daring escape, fleeing back into the Knysna forest.

This final novel in the series was, like its predecessors, adapted to film, marking South Africa’s film entry for the 2021 Oscars.

. . . . . . . . . .

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . .

Matthee died in 2005. She had donated her life’s work and papers to the National Afrikaans Literary Museum and Research Centre (NALN).

Her efforts made such an impact that a Dalene Matthee Memorial dedicated to her memory is situated in the Knysa Forest. Also located there is the Dalene Matthee Big Tree – one of the oldest and largest trees still found in this area.

The walking trail in Knysna is also named for her first forest novel, following much of her story’s locations.

With the Forest books, Dalene Matthee forever changed the way people view the Knysna forest, having spent a lifetime dedicated to telling stories that delve deep into nature and human consciousness.

Contributed by Alex J. Coyne, a journalist, author, and proofreader. He has written for a variety of publications and websites, with a radar calibrated for gothic, gonzo and the weird. His features, posts, articles and interviews have been published in People Magazine, ATKV Taalgenoot, LitNet, The Citizen, Funds for Writers, and The South African, among other publications.

The post Dalene Matthee’s South African “Forest Books” Novels appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 28, 2023

Maria Edgeworth, prolific and influential English novelist

Maria Edgeworth (January 1, 1767 – May 22, 1849), was an Anglo-Irish author whose work has lately been considered deserving of reconsideration. She is best known for novels of Irish life and children’s stories.

Now overshadowed by her contemporaries, Jane Austen and the Brontë sisters, there are compelling arguments in favor of why her work still matters.

The following biography was adapted from the entry in Dictionary of National Biography, 1885–1900, by Leslie Stephen (who happened to be Virginia Woolf’s father):

Early years and education

The daughter of Richard Lovell Edgeworth and his first wife, Anna Maria Elers, Maria was born in Black Bourton, Oxfordshire, England on January 1, 1767, and spent her infancy there.

According to Britannica:

“She lived in England until 1782, when the family moved to Edgeworthstown, County Longford, in midwestern Ireland, where Maria, then 15 and the eldest daughter, assisted her father in managing his estate. In this way she acquired the knowledge of rural economy and of the Irish peasantry that was to be the backbone of her novels.

Domestic life at Edgeworthstown was busy and happy. Encouraged by her father, Maria began her writing in the common sitting room, where the 21 other children in the family provided material and audience for her stories.

She published them in 1796 as The Parent’s Assistant. Even the intrusive moralizing, attributed to her father’s editing, does not wholly suppress their vitality, and the children who appear in them, especially the impetuous Rosamond, are the first real children in English literature since Shakespeare.”

Maria suffered from attempts to increase her growth by mechanical devices, including hanging by the neck. In spite of this contrivance, she always remained small.

She learned to dance, though she could never learn music; she had given early proofs of talent at her first school; she was a good French and Italian scholar, and, like Scott, won credit as a storyteller from her schoolmates.

Some of her holidays were spent with Thomas Day, her father’s great friend, at Anningsley, Surrey. He dosed her with tar water for an inflammation of the eyes, which had threatened a loss of sight, but encouraged her studies, gave her good advice, and won her permanent respect.

Gaining responsibilities in young womanhood

In 1782, she accompanied her father and his third wife to Edgeworthstown, and at his suggestion began to translate Mme. de Genlis’s Adèle et Théodore.

Though still very shy, she saw some good society; she was noticed by Lady Moira, who often stayed with her daughter, Lady Granard, at Castle Forbes, and was frequently at Pakenham Hall, belonging to Lord Longford, a connection and a close friend of Mr. Edgeworth’s.

Her father employed her in keeping accounts and in dealing with his tenants. The education of her little brother Henry was entrusted to her care.

She thus acquired the familiarity with fashionable people and with the Irish peasantry which was to be of use in her novels, as well as a practical knowledge of education.

Her father made her a confidential friend, and though timid on horseback, she delighted in long rides with him for the opportunity of conversation. He became her adviser and to some extent her collaborator in the literary work which for some years was her main occupation.

Maria began to write stories on a slate, which she read to her sisters, and copied out if approved by them. She wrote the “Freeman Family,” afterward developed into “Patronage,” for the amusement of her stepmother, Elizabeth, when convalescing in 1787.

In 1791 her father took his wife to England, and Maria was left in charge of the children, with whom she joined the parents at Clifton in December.

First published writings

They returned to Edgeworthstown at the end of 1793. Here, while taking her share in the family life, she first made her appearance as an author. The “Letters to Literary Ladies,” a defense of female education, came out in 1795.

In 1796, the first volume of the “Parent’s Assistant” was published. In 1798 the marriage of her father to his fourth wife, to whom she had at first a natural objection, brought her an intimate friend in her new stepmother.

For fifty-one years their affectionate relations were never even clouded. The whole family party, which included, besides the children, two sisters of the second Mrs. Edgeworth, Charlotte Sneyd, and Mary Sneyd, lived together on the most affectionate terms.

In 1798 she published, in conjunction with her father, two volumes of Practical Education, presenting in a number of discursive essays a modification of the theories started by Rousseau’s Émile and adopted by Mr. Edgeworth and Thomas Day.

. . . . . . . . . .

Of Maria Edgeworth’s many novels,

Belinda (1801) is best known today

. . . . . . . . . .

In 1800, Maria began her novels for adult readers with Castle Rackrent. It was published anonymously, and written without her father’s assistance. Its vigorous descriptions of Irish character made it a quick success, and the second edition appeared with her name credited.

Belinda followed in 1801, followed in 1802 by Essay on Irish Bulls,, a collaboration with her father. Maria had now achieved fame as an author.

Practical Education had been translated by M. Pictet of Geneva, who also published translations of the Moral Tales in his Bibliothèque Britannique. He visited the Edgeworths in Ireland; and she soon accompanied her father on a visit to France during the peace of Amiens, receiving many civilities from distinguished literary people.

Turning down marriage for a literary life

In Paris, Maria met a Swedish count, Edelcrantz, who made her an offer. As she could not think of retiring to Stockholm, and he felt bound to continue there, the match failed.

Her spirits suffered for a time, and though all communication dropped she remembered him through life, and directly after her return wrote ‘Leonora,’ a novel intended to meet his tastes.

The party returned to England in March 1803, and, after a short visit to Edinburgh, to Edgeworthstown, where Maria set to work upon her stories. She wrote in the common sitting-room, amidst all manner of domestic distractions, and submitted everything to her father, who frequently inserted passages of his own.

Popular Tales and the Modern Griselda appeared in 1804, Leonora in 1806, the first series of Tales of Fashionable Life (containing “Eunice”’ “The Dun,” “Manœuvring,” and “Almeria”) in 1809. The second series (“Absentee,” “Vivian,” and “Mme. de Fleury”) in 1812.

She finished Patronage, which she had begun in 1787. It finally came out in 1814. She set to work on Harrington and Ormond, published together in 1817. She received a few sheets in time to give them to her father on his birthday in May 1817. He had been especially interested in Ormond, to which he had contributed a few scenes. He wrote a short preface to the book and died the following June.

Family and health troubles

After Mr. Edgeworth’s death, his unmarried son Lovell kept up the house. Mr. Edgeworth had left his Memoirs to his daughter, with an injunction to complete them and publish his part unaltered.

She had prepared the book for press in the summer of 1818, though in much depression, due to family troubles, sickness among the peasantry, and an alarming weakness of her eyes.

She gave up reading, writing, and needlework almost entirely for two years, when her eyes completely recovered. Her sisters, meanwhile, acted as amanuenses. She visited Bowood in the autumn of 1818, chiefly to take the advice of her friend Dumont on the Memoirs.

The Memoirs were published during her absence in 1820 and were bitterly attacked in the Quarterly Review. Still, they reached a second edition in 1828, and a third in 1844, when she rewrote her own part.

More literary endeavors

Maria continued settling into her domestic and literary occupations. For the rest of her life, Edgeworthstown continued to be her residence, though she frequently visited London, and made occasional tours.

The most remarkable was a visit to Scotland in the spring of 1823. Sir Walter Scott welcomed her most heartily, and, after seeing her in Edinburgh, received her in Abbotsford. She had read the Lay of the Last Minstrel on its first appearance during her convalescence from a fever in 1805.

Scott declared (in the last chapter of Waverley, and later in the preface to the collected novels) that her descriptions of Irish character had encouraged him to make a similar experiment on Scottish character in the Waverley novels. He sent her a copy of Waverley on its first publication, though without acknowledging the authorship, and she replied with enthusiasm.

During the commercial troubles of 1826, Maria resumed the management of the estate for her brother Lovell, having given up receiving the rents on her father’s death. She showed great business talent and took a keen personal interest in the poor on the estate.

Although greatly occupied by such duties, she again took to writing, beginning her last novel, Helen, about 1830. It didn’t appear until 1834, and soon reached a second edition. It had scarcely the success of her earlier stories. Her style had gone out of fashion.

Later years and legacy

Amidst her various occupations, Maria’s intellectual vivacity remained. She began to learn Spanish at the age of seventy. She kept up a correspondence which in some ways gives even a better idea of her powers than her novels. She paid her last visit to London in 1844.

She knew more or less most of the eminent literary persons of her time, including Joanna Baillie, with whom she stayed at Hampstead, Bentham’s friend, Sidney Smith, Dumont, and Ricardo, whom she visited at Gatcombe Park, Gloucestershire.

Jane Austen sent her Emma soon after its first publication. Maria admired her work, though it doesn’t appear that they had any personal relations.

During the famine of 1846, Maria did her best to relieve the sufferings of the people. Some of her admirers in Boston, Massachusetts, sent one hundred and fifty barrels of flour addressed to “Miss Edgeworth for her poor.” The porters who carried it ashore refused to be paid, and she sent to each of them a woolen comforter knitted by herself.

The deaths of her brother Francis in 1846 and of her favorite sister Fanny in 1848 tried her severely, and she was already weakened by attacks of illness.

Summing up the life and work of Maria Edgeworth

Maria Edgeworth was of diminutive stature, and few portraits of her exist. It seems from Scott’s descriptions that her appearance faithfully represented the combined vivacity, good sense, and amiability of her character. No one had stronger family affections, and the lives of very few authors have been as useful and honorable.

The didacticism of the stories for children has not prevented their permanent popularity. Her more ambitious efforts are injured by the same tendency. She has not the delicacy of touch of Miss Austen, more than the imaginative power of Scott.

But the brightness of her style, her keen observation of character, and her shrewd sense and vigor make her novels still readable, despite obvious artistic defects. Though her puppets are apt to be wooden, they act their parts with spirit enough to make us forgive the perpetual moral lectures.

She died in the arms of her stepmother on May 22, 1849.

More about Maria EdgeworthMajor works

In addition to the works for adult readers listed following, Maria Edgeworth’s books for children have been reprinted in innumerable forms, and often translated. The first collective edition of her novels appeared in fourteen volumes, 1825, others 1848, 1856.

Letters to Literary Ladies, 1795.Parent’s Assistant, first part, 1796; published in 6 vols. in 1800Practical Education, 1798Castle Rackrent, 1800Early Lessons, 1801Belinda, 1801.Moral Tales, 1801Irish Bulls, 1802Popular Tales, 1804Modern Griselda, 1804Leonora, 1806Tales from Fashionable Life (first series), 1812.Patronage, ca.1814Harrington, 1817Ormond, 1817Comic Dramas, 1817Memoirs of R. L. Edgeworth (vol. ii. by Maria), 1820.Sequels to Harry and Lucy, Rosamond, and Frank, from the Early Lessons, 1822–5.Helen, 1834Orlandino, 1834More information

The Case of Maria Edgeworth Britannica Public domain works on Project Gutenberg Audio editions on LibrivoxThe post Maria Edgeworth, prolific and influential English novelist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 22, 2023

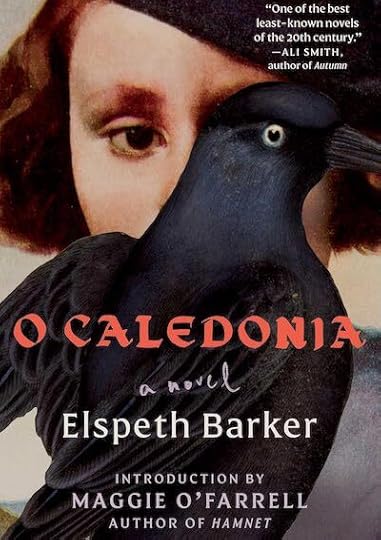

Elspeth Barker, Author of O Caledonia

Elspeth Barker (November 16, 1940 – April 21, 2022) was a Scottish novelist and journalist. Her only novel, O Caledonia, published in 1991 and reissued in 2021, has been hailed as a classic of modern Scottish literature.

Darkly humorous, skillful, lyrical, and somewhat autobiographical, it tells the story of the life and death of a young girl named Janet. It won several awards on its first publication and remained Elspeth Barker’s only published work of fiction.

Early life in Scotland and Oxford

Elspeth Barker was born Elspeth Roberta Cameron Langlands in Edinburgh, Scotland to Robert and Elizabeth Langlands, who had married in 1939. Robert was enlisted in the Royal Scots for the duration of World War II. In addition to Elspeth, the couple had three other daughters – Finella, Alison, and Flora, and a son, David.

For the first years of Elspeth’s life, the family lived in Edinburgh, with a holiday home in Elie. Elizabeth in particular loved the beach and swam in the sea no matter the weather or season.

When Elspeth was seven the family moved to Drumtochty Castle in Aberdeenshire, a Neo-Gothic castle reputedly purchased by her father from the King of Norway.

Elizabeth was a talented and dedicated teacher, especially of English, and together with Robert, she ran the castle as a boys’ prep school. Elspeth (and presumably her siblings) attended classes along with the paying pupils.

Much like her heroine Janet in O Caledonia, Elspeth later remembered the torment of being surrounded by boys who pulled her braids, poked her chest, and threw cricket balls at her. She took refuge in books and a love of animals.

Elspeth marked the passage of adolescence with the coming and going of pets: “I remember being 18 and the dog that had been there all my life – a golden retriever called Rab — died. And I remember that, far more than being allowed a gin and tonic or going to university, the death of that dog signaled the end of my childhood.”

Elspeth later went to boarding school at St Leonard’s in Fife, and then to Somerville College, Oxford in 1958, where she read the classics.

She never graduated, however; she fell asleep in her final exam, and didn’t realize that her father had persuaded the principal to allow her to retake it. Her failure to even attend the rescheduled exam led to her being “sent down” with no degree.

Marriage, children, and a Bohemian Lifestyle

After the disaster at Oxford, Elspeth moved to London, where she worked in a bookshop, and as a waitress. At age twenty-two, she was introduced to poet George Barker (then fifty years old) by his former lover, the Canadian author Elizabeth Smart. Smart was the author of By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept.

George Barker was married, though estranged from his Roman Catholic wife Jessica, and already had ten children — including four with Elizabeth.

Despite initially saying that she found George to be “incredibly rude,” Elspeth began a love affair with him that would last for the rest of his life. Later she became what she described as a “co-wife” with Elizabeth. She was unable to marry George until 1989, after Jessica died.

In the 1960s, the couple took a loan from playwright Harold Pinter and moved to Bintry House, a 17th-century farmhouse in Itteringham, Norfolk, which was owned by the National Trust. There, George wrote poetry while Elspeth taught classics at Renton Hill School for Girls. They had five children together — Raffaella, Lily, Sam, Roderick, and Alexander.

They led a bohemian lifestyle with a steady stream of visitors, and infamous Saturday night drinking parties that could sometimes turn violent.

Elspeth was known as an erudite, witty, and eccentric character: later, many of her friends would remember how she had no driving license, having repeatedly failed her test, but insisted on driving anyway while wearing a wig and sunglasses to fool the police.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

O CaledoniaElspeth’s first writing was commissioned by her daughter, Raffaella, who was then an editor at Harper’s Bazaar. The magazine was assembling a farm-themed issue, and Raffaella asked her mother to write something about her fondness for hens.

Elspeth then secured a contract for a novel after a submission of only a few pages. The resulting book, O Caledonia, was published in 1991, when she was fifty-one.

It was later described by novelist Ali Smith in a New York Times interview as “the best least-known novel of the 20th century…a sparkly, funny work of genius about class, romanticism, social tradition, and literary tradition.”

Glittering and darkly humorous, it opens with the death of a young girl, Janet. But rather than focusing on “whodunnit,” the novel tells the story of Janet’s short life in a bleak Scottish castle.

Clever and awkward, and a social and familial misfit, Janet learns poetry by heart and keeps a jackdaw as a pet. She assumes a certain semblance of outward conformity. The descriptions of the Highland landscape are vividly beautiful, and the novel as a whole is a lyrical showcase of Elspeth’s love of words and language.

O Caledonia has often been described as a coming-of-age novel, but this is a limiting view of a book that skillfully defies genre. It takes inspiration from the Gothic, classical myth, Shakespeare, nature writing, Scottish tradition, and what would now be termed auto-fiction.

The central theme — ostensibly that of a young girl growing up in trying circumstances — reaches into the universal struggle of the individual against authority; the forging and maintaining of an individual identity when everyone around you has their own ideas of what you should be.

It won the Winifred Holtby Prize, the David Higham Prize, the Angel Fiction Prize, and the Scottish Book Prize, as well as being shortlisted for the Whitbread First Novel Award (now the Costa Award).

A shift to journalism

George died not long after the publication of O Caledonia. Elspeth remained in Bintry House with her daughters nearby and several animals in residence, including her beloved pot-bellied pig Portia.

She turned to journalism, becoming a regular contributor to the Independent on Sunday, the London Review of Books, the Times Literary Supplement, the Guardian, the Observer, Country Living, and Vogue.

She had a reputation for filing perfect copy that needed little to no editing, and would usually either relay her articles over the phone or send them handwritten, often with shopping lists scribbled on the envelopes in which they were enclosed.

Elspeth also taught creative writing at Norwich University of the Arts alongside poet George Szirtes. She was a visiting professor of Fiction at Kansas University and tutored at the Arvon Foundation.

In 1997 she edited Loss: An Anthology, which included extracts from writers as wide-ranging as Ovid, Sylvia Plath, Carol Ann Duffy, John Donne, Rilke, Yeats, and Dylan Thomas. In 2012, an edition of her collected journalism called Dog Days was published.

Later years

Elspeth married again in 2007, to Bill Troop; they were divorced six years later. However, she was philosophical:

“At this interesting point of life, one may be whoever and whatever age one chooses. One may drink all night, smash bones in hunting accidents, travel the spinning globe. One may teach one’s grandchildren rude rhymes and Greek myths. One may also move very slowly round the garden in a shapeless coat, planting drifts of narcissus bulbs for later springs.”

O Caledonia was republished in 2021 with an introduction by Maggie O’Farrell (who had, coincidentally, worked on one of the book desks when Elspeth submitted her handwritten copy and often had to phone Elspeth for clarification when her handwriting proved elusive).

In this new introduction, O’Farrell summed up the sentiments of devoted readers on O Caledonia: “This book … is the equivalent of a literary phoenix – rare, thrilling, one of a kind. Read it, please, with that knowledge.”

As dementia gradually took hold, Elspeth moved into a care home in Aylsham, Norfolk. She died in April 2022 of old age.

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Elspeth BarkerMajor works

O Caledonia (1991; new edition 2021)Loss (1998)Notes from the Hen House: Collected Essays by Elspeth Barker (2023)More information

Podcast episode on Lost Ladies of Lit Noir for the Anthropocene: On Elspeth Barker’s O Caledonia Obituary in The Guardian Obituary in the New York Times Tribute in The Book HiveThe post Elspeth Barker, Author of O Caledonia appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 16, 2023

Elinor Glyn, a Biography by Anthony Glyn (1955)

Elinor Glyn (October 17, 1864 – September 23, 1943) was best known as the author of the scandalous 1907 novel Three Weeks and for coining the expression “It Girl.” The following is adapted from a review of Elinor Glyn, a biography by Anthony Glyn (her grandson).

Elinor Glyn: A Portrait of the Woman Who Gave IT a new meaning — and of the fabulous world in which she lived originally appeared in the Orlando Sentinel, July 17, 1955:

Elinor Glyn is the writer who made the word IT synonymous with sex appeal. That was ’s idea, though Mrs. Glyn had a much more involved definition.

Glyn was a legend in her own time. Born on the Isle of Jersey (UK), she died a few weeks before her seventy-ninth birthday.

Marriage, affairs, and good living

She was a young woman in the reign of Queen Victoria, a welcome guest at the house parties at the fabulous estates during the high-living Edwardian era. The object of these festivities was good living, good food, good company, exclusive society, sport, and discreet philandering.

Elinor, a slim, queenly, green-eyed red-haired beauty, had fastidiously refrained from love affairs, for she was determined to make an advantageous marriage. At the age of twenty-eight, in April 1892, at a fashionable wedding at St. George’s, Hanover Square, she married Clayton Glyn, “The most perfect grand seigneur that I have ever met.”

Clayton Glyn was a descendant of Sir Richard Carr Glyn, banker and Lord Mayor of London. he had no business interests and lived the life of a wealthy country gentleman. He was a fine sportsman, a connoisseur of food and wine, a great traveler, and absolutely irresponsible about money. He had a dry, caustic sense of humor.

Elinor’s beauty enchanted him and her pretensions and romantic silliness amused him for a time. Although they soon became indifferent to each other, they remained married until his death in 1915.

She consoled herself with other love affairs, the most famous being her eight-year romance with Lord Curzon. He evidently tired of her possessiveness and probably to avoid the dramatic scene of which he knew she was capable, let her read of his coming marriage to another woman without any advance preparation.

Elinor Glyn was an intimate of famous statesmen as well as of the nobility of Great Britain and the continent. She was a celebrated hostess and a war correspondent at the front in World War I.

A darling of the Jazz Age, she was a contradictory creature. Having inherited from her indomitable grandmother (the daughter of an Irish peer set down in the Canadian wilderness) an intense regard for the importance of aristocratic lineage.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Hollywood of the 1920s and beyondGlyn was a dazzling figure in Hollywood of the twenties. She could yet have a wonderful time among her something less than aristocratic colleagues in the movie business — Charlie Chaplin, Clara Bow, Sam Goldwyn, Gloria Swanson, William Randolph Hearst, Marion Davies, Aileen Pringle, Rudolph Valentino, and others.

When she learned that her husband’s considerable fortune was gone, she could turn out bestsellers, articles, and short stories by the dozen. Even when almost destitute, her normal entourage consisted of a personal maid and chauffeur.

She rented or bought big houses in England, France, and the U.S., decorating them with her favorite color, purple. Willfully uneducated, except in the classics, she consorted with some of the brainiest men of the era.

Bestsellers that were pure tripeGlyn’s writings were purest tripe, erotic and as fruitfully purple as her favorite color scheme. Yet Three Weeks sold five million copies and many of her other books were also bestsellers.

Remember when Paul, the titled Englishman in Three Weeks, is enchanted by the mysterious royal stranger at a hotel in lucern, is invited to her rooms, and in a dizzy perfume of tuberoses, lilies of the valley, and roses, roses, roses, falls madly in love?

His queen reclines on a couch covered with a tiger skin. (Elinor Glyn liked tiger skins. She received five as gifts, one from Lord Curson and one from Lord Milner.)

“Then a madness of tender caressing seized her. She purred as a tiger might have done, while she undulated like a snake. She touched him with her fingertips, she kissed his throat, his wrists, the palms of his hands, his eyelids, his hair. Strange subtle kisses, unlike the kisses of women. And often, between her purring she murmured love-words in some fierce language of her own, brushing his ears and his eyes with her lips the while.”

Literally thousand of people, including American men and women, wrote Glyn for advice on love. She found that even Rudolph Valentino had a lot to learn in the art of making love convincingly before a camera.

“Do you know,” she would murmur, “he had never even thought of kissing the palm, rather than the back of a women’s hand, until I made him do it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Vain, willful, courageous, spiritedGlyn was a beautiful woman until the day she died. She worked at it. Two of her startling aids to beauty: To scrub the face hard with a dry nailbrush until the skin glowed crimson (Not recommended!), and to sleep with one’s head to the magnetic north (pure common sense, she said).

She was always impeccably, fashionably gowned in clothes designed by her sister Lucile, Lady Duff-Gordon.