Nava Atlas's Blog, page 13

January 29, 2024

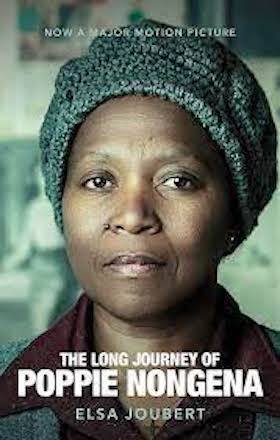

The Long Journey of Poppie Nongena by Elsa Joubert

The Long Journey of Poppie Nongena by Elsa Joubert has been called one of the most important novels to emerge from the African continent. Published in 1979, the book has been translated into thirteen languages and was adapted to screen for the film Poppie Nongena (2009).

Author Elsa Joubert was known for her travelogues, poetry, news features, and groundbreaking novels. She is considered part of the Sixtiers literary movement, which also included authors Ingrid Jonker, Breyten Breytenbach, and André Brink.

Here’s more about the author, and why The Long Journey of Poppie Nongena is a story about struggle more readers should know.

About Elsa Joubert

Elsa Joubert (October 19, 1922) was born in Paarl, Cape Town, South Africa. She first studied for a Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree, working as a teacher in Cradock. After this, she achieved her Master’s in Dutch-Afrikaans Literature.

From 1946 to 1948, she worked as an editor for the lifestyle magazine Huisgenoot.

Her first travelogue is born from a trip to the Egyptian Nile with her husband (1948). The results of her trip were published in 1957. Joubert mentions during an interview that her initial research at the African Library in Johannesburg brought her closer to Africa and its people.

We’re Waiting on the Captain (1963) is Joubert’s debut novel, inspired by the story of a murder trial she had read about in The Transvaler. Joubert’s husband translates her next book The Die at Sunset (1964/1982) from Afrikaans into English.

The 1964 travelogue The Staff of Monomotapa explored Mozambique the book was cited as an inspiration to Nelson Mandela (2002). During a phone call to the author, Mandela would say the book was the first time he had seen an Afrikaner “who considered the possibility of a partially black-and-white government in South Africa.” Reportedly when Mandela met Graça Machel, he knew only of her homeland Mozambique from what he had read about in Joubert’s book.

Joubert continued writing full-time, becoming known for her travel stories documenting more trips, often via ocean, to Uganda, Cairo, Angola, and Indonesia.

A South African government tribute praises Joubert for “lifting the veil” of Apartheid’s difficulties and injustices with her writing. She begins the Afrikaans Writers Guild, chairing it during the mid-eighties.

Collected short stories (Milk, 1980) appeared the same year as The Long Journey of Poppie Nongena’s translation. In 1995, she published The Long Journey of Isobelle: this time, telling the 100-year story of an Afrikaans family and their own struggles. A Lion on the Landing: Memories of a South African Youth explores Jourert’s childhood.

Joubert’s last work of fiction Twee vroue (Two women) published in 2002, with two books contained in one volume. The first tale, Pampas, explores the remnants of Boer-colonies in Argentina seen during her travels with her husband in the eighties.

Elsa Joubert passed away in June 2020 from COVID-related complications. Before her passing, she wrote a letter asking the government to relax lockdown restrictions: “Humanely speaking, we are in the last weeks and days of our lifetimes. Us living in homes or institutions, however wonderful, are totally cut off from our family members.”

A New York Times obituary remembers Joubert as an “Afrikaans writer who explored black reality.”

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

The Long Journey of Poppie NongenaThe Long Journey of Poppie Nongena was first published in 1979. Since publication, it has been translated into thirteen languages, with the author translating it into English herself. From 1982 to 1984, the story was performed as a stage play (co-written with Sandra Kotzé).

The Long Journey of Poppie Nongena tells the story of Poppie, who is considered an illegal citizen once her husband, Stone, becomes too ill for his job. The journey was a rare look at the circumstances and often difficulties associated with township life – including the harsh consequences of Pass Laws.

Unusually, the novel explored themes that had hardly been touched upon by other Afrikaans, white authors of the time – much more typical of the Sixtiers-movement which Joubert was considered part of.

The Longer Story of Ntombizodumo

Poppie’s story was inspired by Joubert’s domestic assistant, Ntombizodumo Eunice Msutwana-Ntsata. Joubert wrote that she started the story after, one evening, Ntombizodumo told her of “a night of terror in the townships.”(Interview, Red Roses/Rooi Rose) The real Poppie’s identity stayed hidden and was only revealed in 2009. The same year, the tale was adapted to screen for Poppie Nongena.

Elements of Ntombizodumo and her life story were intertwined through The Long Journey of Poppie Nongena. Both were isiXhosa and spoke Afrikaans, with Ntombizodumo having learned the language as a child – but was reportedly discouraged from speaking it by her own elders.

As part of Joubert’s research, she would have lengthy conversations with Ntombizodumo. She would also, according to LitNet, travel to the townships herself – and sat in during legal proceedings investigating the 1976 Soweto uprising.

According to The Citizen, surviving family members raised concerns that Ntombizodumo was not adequately compensated for the use of her life story. Her daughter Roto said, that her mother was “an unsung hero who had been humiliated by the apartheid government.”

A LitNet biography says, “Elsa gave half of her writing royalties from the sales of The Long Journey of Poppie Nongena to the woman who she heard the story from, with which the lady bought herself a home in the Transkei and gave her two children an education.”

An IOL article says that the author and publisher “lost touch” with Ntombizodumo after her death in the nineties. The story concludes by saying the movie’s producers have set up a meeting with family members to discuss the adaptation and its consequences.

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

Poppie Nongena, the 2009 filmThe 2009 film Poppie Nongena stars Clementine Mosimane in the titular role, with Anna-Mart van der Merwe and Chris Gxalaba in supporting roles. When Stone (Chris Gxalaba) is unable to work, Poppie becomes an illegal citizen of South Africa who must maintain her family life with much difficulty.

It has become one of the most acclaimed Afrikaans-language films to date, winning a total of twelve awards at the Silwerskerm Festival. Watch the trailer with English subtitles for Poppie Nongena here.

The post The Long Journey of Poppie Nongena by Elsa Joubert appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 25, 2024

Classic Uncanny Stories by British Women Writers

Asked to name uncanny authors, most readers would come up with names like Edgar Allan Poe, M.R. James, H.P. Lovecraft, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu – all male. But a surprising number of women authors, some of whom may be better known for writing more homelike novels, also wrote very “unhomelike” short stories.

Sigmund Freud’s famous essay about weird literature is usually translated as The Uncanny. But the German word “unheimlich” literally means “unhomelike.”

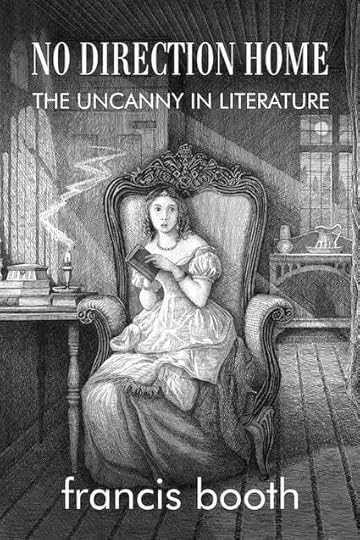

No Direction Home: The Uncanny in Literature by Francis Booth (©2023, from which this essay is excerpted by permission) traces how uncanny literature takes us from the familiar, the reassuring, the homelike, into a world of the unfamiliar, the unsettling, and the unhomelike.

The American author Edith Wharton understood that before leading us into the world of the tense and unsettling, the author first has to make us feel calm and settled; she says that this can be done by starting with a modern clean, electric-lit environment at least as well as with a gloomy old castle. This will be discussed further in Two Uncanny Stories by Edith Wharton.

. . . . . . . . .

No Direction Home by Francis Booth

is available on Amazon U.S*. and Amazon U.K.

. . . . . . . . .

This contrast between the bright, modern, recognizably homelike and the strange unhomelike encroaching on it is also perfectly encapsulated in a story by another Edith: Edith Nesbit, an English political activist and co-founder of the Fabian Society, best known for her children’s books as E. Nesbit, including most famously The Railway Children.

Nesbit was also the author of several collections of uncanny stories, including Grim Stories, Something Wrong and Fear.

I told him I thought the house was very pretty, and fresh, and homelike — only a little too new — but that fault would mend with time. He said:

“It is new: that’s just it. We’re the first people who’ve ever lived in it. If it were an old house, Margaret, I should think it was haunted.”

I asked if he had seen anything. “No,” he said, “not yet.”

“Heard then?” said I.

“No — not heard either,” he said, “but there’s a sort of feeling: I can’t describe it — I’ve seen nothing and I’ve heard nothing, but I’ve been so near to seeing and hearing, just near, that’s all. And something follows me about — only when I turn round, there’s never anything, only my shadow. And I always feel that I shall see the thing next minute — but I never do — not quite — it’s always just not visible. (Edith Nesbit, The Shadow, 1905)

The new, fresh, homelike home has been made unhomelike by the mysterious shadow, which the narrator also sees. “It was crouching there; it sank, and the black fluidness of it seemed to be sucked under the door of Mabel’s room.”

When the narrator goes in, Mabel is dead but her baby is alive. At the funeral, another shadow appears.

“Between us and the coffin, first grey, then black, it crouched an instant, then sank and liquefied—and was gathered together and drawn till it ran into the nearest shadow. And the nearest shadow was the shadow of Mabel’s coffin.” Then Mabel’s daughter dies too. “I had never been able to forget the look on her dead face.”

At the start of her story The Shadow, Edith Nesbit had warned us, as many uncanny authors do at the start, that it will make no sense; it will have no easy, rational explanation.

This is not an artistically rounded off ghost story, and nothing is explained in it, and there seems to be no reason why any of it should have happened. But that is no reason why it should not be told. You must have noticed that all the real ghost stories you have ever come close to, are like this in these respects — no explanation, no logical coherence.

Another Nesbit story, from the collection Grim Tales, also begins with a similar disclaimer: the narrator is presenting the reader a version of events which they will not believe, but washing her hands of it, fending off the skeptics, disarming any doubters in the first paragraph:

Although every word of this story is as true as despair, I do not expect people to believe it. Nowadays a “rational explanation” is required before belief is possible. Let me then, at once, offer the “rational explanation” which finds most favour among those who have heard the tale of my life’s tragedy. It is held that we were “under a delusion,” Laura and I, on that 31st of October; and that this supposition places the whole matter on a satisfactory and believable basis. The reader can judge, when he, too, has heard my story, how far this is an “explanation,” and in what sense it is “rational.” (Edith Nesbit, Man-Size in Marble, 1893)

Reality or Delusion? by Ellen Wood (1868)

Following are a couple more examples of openings of stories that start with disclaimers that the reader will not believe what is to come, even though it is all true. The first is from the British novelist Ellen Wood, better known at the time as Mrs. Henry Wood, most famous for the novel East Lynne, which is best remembered for the phrase, “dead and never called me mother.”

“This is a ghost story. Every word of it is true. And I don’t mind confessing that for ages afterwards some of us did not care to pass the spot alone at night. Some people do not care to pass it by.” (Ellen Wood, Reality or Delusion? )

In fact, as the title hints, it may well have been a mass delusion, and may be explicable without recourse to supernatural explanations. “If I say that I believe in it too, I shall be called a muff and a double muff. But there is no stumbling-block too difficult to be got over.”

The Open Door by Charlotte Riddell (1882)

Another example of this kind of opening disclaimer comes from the Irish novelist Charlotte Riddell, known at the time as Mrs. J. H. Riddell. As in the previous case, and as with many stories by female authors of uncanny stories, the narrator is male.

Some people do not believe in ghosts. For that matter, some people do not believe in anything. . . That is the manner in which this story, hitherto unpublished, has been greeted by my acquaintances. How it will be received by strangers is quite another matter. I am going to tell what happened to me exactly as it happened, and readers can credit or scoff at the tale as it pleases them. It is not necessary for me to find faith and comprehension in addition to a ghost story, for the world at large. If such were the case, I should lay down my pen. (The Open Door, 1882)

And again, as with the previous story, the mystery, of a “haunted” and unhomelike house in which there is a door that will not stay closed – those pesky doors again – turns out not to be a haunting at all but merely someone continually opening the door to scare away the superstitious in order to claim the house for themselves.

The Nature of the Evidence by May Sinclair (1923)

The frame story is a very common device in uncanny stories, where sometimes the tale is presented by the “author” as having been found in a diary or in letters by someone who is now dead and cannot explain further. Or perhaps the story has been told to the narrator by a friend; this allows the first-person narrator to present the story as “true” without having to vouch for it.

And sometimes the “friend” may be presented as an unimpeachable source, as in one of the stories in May Sinclair’s collection Uncanny Stories. Like the other female authors we have looked at, Sinclair was a “serious” novelist as well as a writer of uncanny stories and was also a political activist, being an active suffragist and member of the Woman Writers’ Suffrage League.

This is the story Marston told me. He didn’t want to tell it. I had to tear it from him bit by bit. I’ve pieced the bits together in their time order, and explained things here and there, but the facts are the facts he gave me. There’s nothing that I didn’t get out of him somehow.

Out of him—you’ll admit my source is unimpeachable. Edward Marston, the great K.C., and the author of an admirable work on “The Logic of Evidence.” (The Nature of the Evidence, 1923)

Lady Farquhar’s Old Lady: A True Ghost Story by Mrs. Molesworth (1873)

As well as presenting a story as coming from a scientific, rational source, the provenance of the uncanny tale may be presented as unimpeachable by virtue of the “facts” being from the upper classes, in the days when the aristocracy were seen to be trustworthy, as in the following opening paragraphs from a story by a British writer best known for her children’s books, published under the name Mrs. Molesworth, and her adult novels published under the gender-neutral name Ennis Graham.

I myself have never seen a ghost (I am by no means sure that I wish ever to do so), but I have a friend whose experience in this respect has been less limited than mine. Till lately, however, I had never heard the details of Lady Farquhar’s adventure, though the fact of there being a ghost story which she could, if she chose, relate with the authority of an eye-witness, had been more than once alluded to before me.

Living at extreme ends of the country, it is but seldom my friend and I are able to meet; but a few months ago I had the good fortune to spend some days in her house, and one evening our conversation happening to fall on the subject of the possibility of so-called “supernatural” visitations or communications, suddenly what I had heard returned to my memory.

“By the bye,” I exclaimed, “we need not go far for an authority on the question. You have seen a ghost yourself, Margaret. I remember once hearing it alluded to before you, and you did not contradict it. I have so often meant to ask you for the whole story. Do tell it to us now.”

Lady Farquhar hesitated for a moment, and her usually bright expression grew somewhat graver. When she spoke, it seemed to be with a slight effort. “You mean what they all call the story of ‘my old lady,’ I suppose,” she said at last.

“Oh yes, if you care to hear it, I will tell it you. But there is not much to tell, remember.”

“There seldom is in true stories of the kind,” I replied. “Genuine ghost stories are generally abrupt and inconsequent in the extreme, but on this very account all the more impressive. Don’t you think so?”

“I don’t know that I am a fair judge,” she answered. “Indeed,” she went on rather gravely, “my own opinion is that what you call true ghost stories are very seldom told at all.”

“How do you mean? I don’t quite understand you,” I said, a little perplexed by her words and tone.

“I mean,” she replied, “that people who really believe they have come in contact with—with anything of that kind, seldom care to speak about it.”

What Victorian reader could question the veracity of a woman called Lady Farquhar? Lords in Victorian literature may be rogues and roués but Ladies are always beyond reproach.

The Old Nurse’s Story by Elizabeth Gaskell (1852)

A nice twist on the first-person narration is provided in a ghost story by Elizabeth Gaskell, another female writer of uncanny tales who is best known for “serious” novels including Mary Barton, North and South and Wives and Daughters that tackled the social issues of her time. Mrs. Gaskell, as she was known, also wrote a biography of Charlotte Brontë.

Gaskell also regularly published uncanny stories in collaboration with Charles Dickens for his Household Words. Here the tale purports to be told to children by their mother’s former nurse and is about the ghost of a child that their mother saw when she was herself a child. It seems that this tale has been told to them before and has become a favorite.

You know, my dears, that your mother was an orphan, and an only child; and I dare say you have heard that your grandfather was a clergyman up in Westmoreland, where I come from. I was just a girl in the village school, when, one day, your grandmother came in to ask the mistress if there was any scholar there who would do for a nurse-maid; and mighty proud I was, I can tell ye, when the mistress called me up, and spoke to my being a good girl at my needle, and a steady, honest girl, and one whose parents were very respectable, though they might be poor.

I thought I should like nothing better than to serve the pretty young lady, who was blushing as deep as I was, as she spoke of the coming baby, and what I should have to do with it. However, I see you don’t care so much for this part of my story, as for what you think is to come, so I’ll tell you at once. (Elizabeth Gaskell, The Old Nurse’s Story, 1852)

The story is about a young orphan with no direction home. Miss Rosamond, the mother of the children to whom the story is being told, had been sent as a child, with her nurse, the narrator, to live in a big house with distant relatives. The enormous house has no homelike qualities, “and the hall, which had no fire lighted in it, looked dark and gloomy.”

It is so large that the nurse never even sees all of it and is so grand it has:

“… an organ built into the wall, and so large that it filled up the best part of that end. Beyond it, on the same side, was a door; and opposite, on each side of the fire-place, were also doors leading to the east front; but those I never went through as long as I stayed in the house, so I can’t tell you what lay beyond.”

As a child, lonely young Rosamond had found an imaginary friend outside the unhomelike big house who she insists is a real girl, though the nurse has seen Rosamond’s footprints in the snow and knows she has been alone. But the other “child” may not be imaginary and may be a ghost with bad intentions; one of the servants tells the nurse, “keep her from that child! It will lure her to her death! That evil child! Tell her it is a wicked, naughty child.”

But the ghost child is not evil, she has had evil done to her, by her father, watched by her sister, who is still alive and now an old woman. Reminded of this years later she sees, as does the nurse, an apparition of the scene where the ghost girl was killed all those years ago, while she watched on. So, this story does have a resolution and an explanation, though the rational explanation is that the ghost was real.

Hauntings by Vernon Lee (1890)

We were talking last evening—as the blue moon-mist poured in through the old-fashioned grated window, and mingled with our yellow lamplight at table—we were talking of a certain castle whose heir is initiated (as folk tell) on his twenty-first birthday to the knowledge of a secret so terrible as to overshadow his subsequent life. It struck us, discussing idly the various mysteries and terrors that may lie behind this fact or this fable, that no doom or horror conceivable and to be defined in words could ever adequately solve this riddle; that no reality of dreadfulness could seem caught but paltry, bearable, and easy to face in comparison with this vague we know not what.

Vernon Lee is most famous now for her story collection Hauntings, though, like May Sinclair a generation later, she was a feminist campaigner. Lee also played the harpsichord and wrote several influential essays and books on art and aesthetics, especially concerning Renaissance Italy.

Lee herself was the epitome of the unhomelike: born to British parents in France, she lived most of her life in Italy, changed her name from the feminine Violet to the gender-neutral Vernon, dressed à la garçonne – as a boy – and may have had affairs with women at a time when women weren’t supposed to.

Lee continues the above thought, from the introduction to Hauntings, agreeing with writers of the genre that a supernatural story should not contain too much explanation:

And this leads me to say, that it seems to me that the supernatural, in order to call forth those sensations, terrible to our ancestors and terrible but delicious to ourselves, sceptical posterity, must necessarily, and with but a few exceptions, remain enwrapped in mystery.

Indeed, ‘tis the mystery that touches us, the vague shroud of moonbeams that hangs about the haunting lady, the glint on the warrior’s breastplate, the click of his unseen spurs, while the figure itself wanders forth, scarcely outlined, scarcely separated from the surrounding trees; or walks, and sucked back, ever and anon, into the flickering shadows.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture: Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth-Century Literary Eroticism; Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938; High Collars & Monocles: 1920s Novels by British Female Couples; and A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young Adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

The post Classic Uncanny Stories by British Women Writers appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 18, 2024

The Shadow in the Corner by Mary Elizabeth Braddon (1879)

A fairly common trope in uncanny stories is that of a shadow. An example of this is the short story “The Shadow in the Corner” by Mary Elizabeth Braddon (1879), a serious, if rather sensationalist, female novelist who wrote ghost stories. Braddon is most famous for the 1862 novel, Lady Audley’s Secret.

As in other such stories, one of the characters is an educated, responsible man, in this case a scientist, who seeks to disprove what he sees as local superstition. This time we start with a spooky and unhomelike old house, which is believed to be haunted by the restless spirit of a previous owner who had hanged himself in one of the top floor servants’ rooms.

This discussion is excerpted from No Direction Home: The Uncanny in Literature by Francis Booth (©2023, by permission). Read “The Shadow in the Corner” in full.

. . . . . . . . .

No Direction Home by Francis Booth

is available on Amazon U.S*. and Amazon U.K.

. . . . . . . . .

Wildheath Grange stood a little way back from the road, with a barren stretch of heath behind it, and a few tall fir-trees, with straggling wind-tossed heads, for its only shelter. It was a lonely house on a lonely road, little better than a lane, leading across a desolate waste of sandy fields to the sea-shore; and it was a house that bore a bad name among the natives of the village of Holcroft, which was the nearest place where humanity might be found.

It was a good old house, nevertheless, substantially built in the days when there was no stint of stone and timber — a good old grey stone house with many gables, deep window-seats, and a wide staircase, long dark passages, hidden doors in queer corners, closets as large as some modern rooms, and cellars in which a company of soldiers might have lain perdu.

This large, dilapidated house is occupied only by three elderly people: two old retainers in the form of the butler and his wife, and the rational, detached, scientist owner Michael, whose family home it has always been and who now lives there in peaceful solitude; “it would not have been difficult to have traced a certain affinity between the dull grey building and the man who lived in it.

Both seemed alike remote from the common cares and interests of humanity; both had an air of settled melancholy, engendered by perpetual solitude; both had the same faded complexion, the same look of slow decay.”

The butler has recently insisted that his wife must have a maid to help her in her old age; the owner has agreed though the butler complains that they will not be able to engage anyone local because of the house’s gloomy reputation.

They do find a young woman, recently orphaned (as we will discuss at length later, orphans have no home; everywhere is unhomelike) and gone to live with a distant relative, like many other literary orphans. She has been “educated above her station” by her late father but seems happy to find a “place,” literally and metaphorically.

Maria is innocent and attractive, as even the unworldly owner can see. Ostensibly because all the other rooms on the servant’s floor are damp, though probably because of his natural curmudgeonliness, the butler puts Maria in the room where the suicide of the present owner’s great uncle had taken place. Even the shy Maria has to say something to her new, skeptical master.

“I felt weighed down in my sleep as if there were some heavy burden laid upon my chest. It was not a bad dream, but it was a sense of trouble that followed me all through my sleep; and just at daybreak — it begins to be light a little after six — I woke suddenly, with the cold perspiration pouring down my face, and knew that there was something dreadful in the room.”

“What do you mean by something dreadful. Did you see anything?”

“Not much, sir; but it froze the blood in my veins, and I knew it was this that had been following me and weighing upon me all through my sleep. In the corner, between the fireplace and the wardrobe, I saw a shadow — a dim, shapeless shadow —” “Produced by an angle of the wardrobe, I daresay.” “No, sir; I could see the shadow of the wardrobe, distinct and sharp, as if it had been painted on the wall. This shadow was in the corner — a strange, shapeless mass; or, if it had any shape at all, it seemed —”

“What?” asked Michael eagerly.

“The shape of a dead body hanging against the wall!”

Michael looks for a rational explanation, even if it is a psychological one. He examines the room and spends the night there.

“Yes; there was the shadow: not the shadow of the wardrobe only—that was clear enough, but a vague and shapeless something which darkened the dull brown wall; so faint, so shadow, that he could form no conjecture as to its nature, or the thing it represented.”

Then he finds a hook high up in the wall that he cannot explain; he does not know that his great uncle had hanged himself from it, though the butler probably does. Michael tells the butler to move Maria to a room on a lower floor, but he ignores the instruction and tells Maria she must go back.

The next morning Maria does not come downstairs, and her room is locked. Breaking down the door, “Maria was hanging from the hook in the wall.”

Although Braddon’s sensational Lady Audley’s Secret is by no means either Gothic or uncanny, it does contain the dichotomy we have been looking at between the homelike and the unhomelike.

As Elaine Showalter summarized it, “Braddon’s bigamous heroine deserts her child, pushes husband number one down a well, thinks about poisoning husband number two and sets fire to a hotel in which her other male acquaintances are residing.”

“A glorious old place. A place that visitors fell in raptures with; feeling a yearning wish to have done with life, and to stay there forever, staring into the cool fish-ponds and counting the bubbles as the roach and carp rose to the surface of the water. A spot in which peace seemed to have taken up her abode, setting her soothing hand on every tree and flower, on the still ponds and quiet alleys, the shady corners of the old-fashioned rooms, the deep window-seats behind the painted glass, the low meadows and the stately avenue.” (Mary Elizabeth Braddon, Lady Audley’s Secret, 1862)

All these dark events are based around an idyllic, homelike, and peaceful country estate, which makes them seem even more uncanny.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture: Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth-Century Literary Eroticism; Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938; High Collars & Monocles: 1920s Novels by British Female Couples; and A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young Adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Shadow in the Corner by Mary Elizabeth Braddon (1879) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 16, 2024

All Souls’ & The Eyes: Two Uncanny Stories by Edith Wharton

A surprising number of women authors, some of whom may be better known for writing more homelike novels, also wrote very “unhomelike” short stories. One was Edith Wharton, who understood that before leading us into the world of the tense and unsettling, the author first has to make us feel calm and settled.

Wharton said that this can be done by starting with a modern clean, electric-lit environment at least as well as with a gloomy old castle.

Sigmund Freud’s famous essay about weird literature is usually translated as The Uncanny. But the German word “unheimlich” literally means “unhomelike.”

No Direction Home by Francis Booth (©2023, from which this essay is excerpted, by permission) traces how uncanny literature takes us from the familiar, the reassuring, the homelike, into a world of the unfamiliar, the unsettling and the unhomelike.

Following is an introduction to Edith Wharton’s uncanny short stories, “All Souls’” and “The Eyes.”

. . . . . . . . .

No Direction Home by Francis Booth

is available on Amazon U.S*. and Amazon U.K.

. . . . . . . . .

I read the other day in a book by a fashionable essayist that ghosts went out when electric light came in. What nonsense! The writer, though he is fond of dabbling in a literary way, in the supernatural, hasn’t even reached the threshold of his subject. As between turreted castles patrolled by headless victims with clanking chains, and the comfortable suburban house with a refrigerator and central heating where you feel, as soon as you’re in it, that there’s something wrong, give me the latter for sending a chill down the spine!

Edith Wharton story “All Souls’” starts, as does Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Black Cat” and many other uncanny tales do, by claiming to contain just simple facts related by a friend or relative of the person to whom the uncanny experience happens.

Queer and inexplicable as the business was, on the surface it appeared fairly simple — at the time, at least; but with the passing of years, and owing to there not having been a single witness of what happened except Sara Clayburn herself, the stories about it have become so exaggerated, and often so ridiculously inaccurate, that it seems necessary that someone connected with the affair, though not actually present — I repeat that when it happened my cousin was (or thought she was) quite alone in her house — should record the few facts actually known. . . So I have written down, as clearly as I could, the gist of the various talks I had with cousin Sara, when she could be got to talk — it wasn’t often — about what occurred during that mysterious weekend.

[“All Souls” is not yet in the public domain, so it’s difficult to find in full online. It’s part of several anthologies, and the lead story in Ghosts, a collection of her spooky stories collected by Wharton herself, not long before her death in 1937, the same year this story was written.]“The Eyes” by Edith Wharton (1910)

In another, earlier Edith Wharton story, “The Eyes” is a tale presented as having been told by a member of a group of educated, rational friends sitting round a convivial but spooky fireplace in the dark, swapping ghost stories, which perhaps refers to the “dark and stormy night” when Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and John Polidori’sThe Vampyre were both conceived. Read “The Eyes” in full.

We had been put in the mood for ghosts, that evening, after an excellent dinner at our old friend Culwin’s, by a tale of Fred Murchard’s — the narrative of a strange personal visitation. Seen through the haze of our cigars, and by the drowsy gleam of a coal fire, Culwin’s library, with its oak walls and dark old bindings, made a good setting for such evocations; and ghostly experiences at first hand being, after Murchard’s brilliant opening, the only kind acceptable to us, we proceeded to take stock of our group and tax each member for a contribution. There were eight of us, and seven contrived, in a manner more or less adequate, to fulfill the condition imposed. It surprised us all to find that we could muster such a show of supernatural impressions.

The first person perspective in uncanny stories

Uncanny stories – including virtually all of Poe’s – are often told in the first person, rather than by an omniscient narrator, because no individual can ever know the whole truth and can never offer a complete, rationalised version of events seen from all points of view.

A Jane Austen-style omniscient, judgemental narrator would have to come down off the fence. This authorial judging is why her Northanger Abbey is not uncanny (nor is it meant to be: it is meant as a spoof of the uncanny).

“Alas! If the heroine of one novel be not patronized by the heroine of another, from whom can she expect protection and regard? I cannot approve of it.”

Edith Wharton’s novels of manners, except for the rather uncanny Ethan Frome, with its frame narrative, are told in the third person with as stern a moral tone as Austen’s, whereas her uncanny short stories are mostly first-person. Uncanny stories are often told in the first person, because a single narrator cannot know everything as an omniscient narrator purports to.

. . . . . . . . .

See also: Classic Uncanny Stories by British Women Writers

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture: Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth-Century Literary Eroticism; Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938; High Collars & Monocles: 1920s Novels by British Female Couples; and A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young Adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post All Souls’ & The Eyes: Two Uncanny Stories by Edith Wharton appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

All Souls & The Eyes: Two Uncanny Stories by Edith Wharton

A surprising number of women authors, some of whom may be better known for writing more homelike novels, also wrote very “unhomelike” short stories. One was Edith Wharton, who understood that before leading us into the world of the tense and unsettling, the author first has to make us feel calm and settled.

Wharton said that this can be done by starting with a modern clean, electric-lit environment at least as well as with a gloomy old castle.

Sigmund Freud’s famous essay about weird literature is usually translated as The Uncanny. But the German word “unheimlich” literally means “unhomelike.”

No Direction Home by Francis Booth (©2023, from which this essay is excerpted, by permission) traces how uncanny literature takes us from the familiar, the reassuring, the homelike, into a world of the unfamiliar, the unsettling and the unhomelike.

Following is an introduction to Edith Wharton’s uncanny short stories, “All Souls’” and “The Eyes.”

. . . . . . . . .

No Direction Home by Francis Booth

is available on Amazon U.S*. and Amazon U.K.

. . . . . . . . .

I read the other day in a book by a fashionable essayist that ghosts went out when electric light came in. What nonsense! The writer, though he is fond of dabbling in a literary way, in the supernatural, hasn’t even reached the threshold of his subject. As between turreted castles patrolled by headless victims with clanking chains, and the comfortable suburban house with a refrigerator and central heating where you feel, as soon as you’re in it, that there’s something wrong, give me the latter for sending a chill down the spine!

Edith Wharton story “All Souls’” starts, as does Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Black Cat” and many other uncanny tales do, by claiming to contain just simple facts related by a friend or relative of the person to whom the uncanny experience happens.

Queer and inexplicable as the business was, on the surface it appeared fairly simple — at the time, at least; but with the passing of years, and owing to there not having been a single witness of what happened except Sara Clayburn herself, the stories about it have become so exaggerated, and often so ridiculously inaccurate, that it seems necessary that someone connected with the affair, though not actually present — I repeat that when it happened my cousin was (or thought she was) quite alone in her house — should record the few facts actually known. . . So I have written down, as clearly as I could, the gist of the various talks I had with cousin Sara, when she could be got to talk — it wasn’t often — about what occurred during that mysterious weekend.

[“All Souls” is not yet in the public domain, so it’s difficult to find in full online. It’s part of several anthologies, and the lead story in Ghosts, a collection of her spooky stories collected by Wharton herself, not long before her death in 1937, the same year this story was written.]“The Eyes” by Edith Wharton (1910)

In another, earlier Edith Wharton story, “The Eyes” is a tale presented as having been told by a member of a group of educated, rational friends sitting round a convivial but spooky fireplace in the dark, swapping ghost stories, which perhaps refers to the “dark and stormy night” when Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and John Polidori’sThe Vampyre were both conceived. Read “The Eyes” in full.

We had been put in the mood for ghosts, that evening, after an excellent dinner at our old friend Culwin’s, by a tale of Fred Murchard’s — the narrative of a strange personal visitation. Seen through the haze of our cigars, and by the drowsy gleam of a coal fire, Culwin’s library, with its oak walls and dark old bindings, made a good setting for such evocations; and ghostly experiences at first hand being, after Murchard’s brilliant opening, the only kind acceptable to us, we proceeded to take stock of our group and tax each member for a contribution. There were eight of us, and seven contrived, in a manner more or less adequate, to fulfill the condition imposed. It surprised us all to find that we could muster such a show of supernatural impressions.

The first person perspective in uncanny stories

Uncanny stories – including virtually all of Poe’s – are often told in the first person, rather than by an omniscient narrator, because no individual can ever know the whole truth and can never offer a complete, rationalised version of events seen from all points of view.

A Jane Austen-style omniscient, judgemental narrator would have to come down off the fence. This authorial judging is why her Northanger Abbey is not uncanny (nor is it meant to be: it is meant as a spoof of the uncanny).

“Alas! If the heroine of one novel be not patronized by the heroine of another, from whom can she expect protection and regard? I cannot approve of it.”

Edith Wharton’s novels of manners, except for the rather uncanny Ethan Frome, with its frame narrative, are told in the third person with as stern a moral tone as Austen’s, whereas her uncanny short stories are mostly first-person. Uncanny stories are often told in the first person, because a single narrator cannot know everything as an omniscient narrator purports to.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture: Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth-Century Literary Eroticism; Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938; High Collars & Monocles: 1920s Novels by British Female Couples; and A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young Adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

The post All Souls & The Eyes: Two Uncanny Stories by Edith Wharton appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 14, 2024

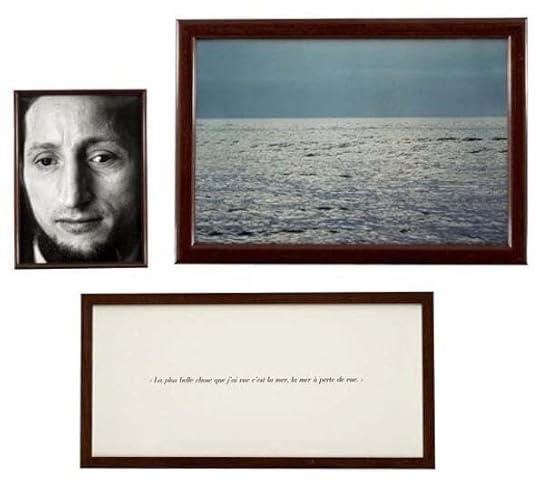

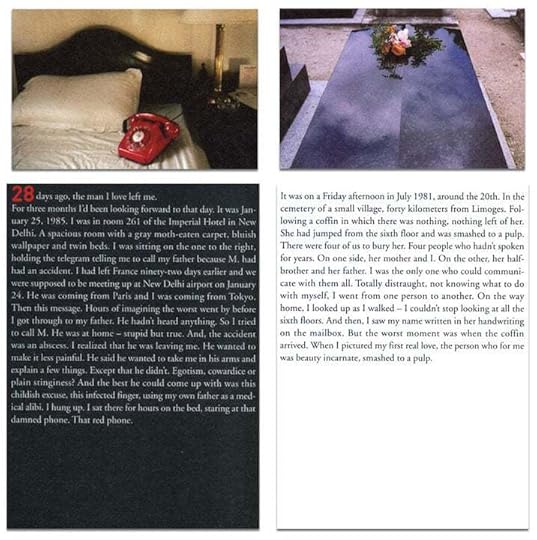

Sophie Calle and Double Game: Is Artistic Voyeurism Ethical and Relevant?

In 1992, the American writer Paul Auster used the French conceptual artist Sophie Calle as a thinly disguised character in his novel, Leviathan. Unlike Calle, who famously plunders the lives of others in service of her art, he asked her permission to do so. Delighted to be a character in a novel, she agreed.

And so this became a kind of game that ultimately takes the cliché of art imitating life — and vice versa — to dizzying new heights.

In his description of the character, who he calls Maria, Auster accurately describes some of Calle’s real life projects, and in other cases, he makes up projects that sound as if they could have been done by here. His description of the fictional Maria gives the viewer insight into the real Sophie Calle:

“Maria was an artist, but the work she did had nothing to do with creating objects commonly defined as art. Some people called her a photographer, others referred to her as a conceptualist, still others considered her a writer, but none of these description was accurate and in the end I don’t think she can be pigeonholed in any way.

Her work was too nutty for that, too idiosyncratic, too personal to be though of as belonging to any particular medium or discipline. Ideas would take hold of her, she would work on projects, there would be concrete results that could be shown in galleries, but this activity didn’t stem so much from a desire to make art so much as from a need to indulge her obsessions, to live her life precisely as she wanted to live it.”

Calle decided to turn Auster’s writings into a project as well as a kind of game — she collected all the projects she had actually done, and that he described, into an exhibit as well as a book, juxtaposing the pages, with the appropriate paragraphs outlined in red, with the projects, and in other cases, where Auster himself made up the projects, she took his cues and executed the project as a new undertaking.

Life imitates art imitates life …

The result is a provocative blend of fact, fantasy, and fiction with a unique twist — though it does not encompass all of Calle’s important projects (notably absent are Exquisite Pain and The Appointment). It becomes a retrospective of diverse works in one neat package.

Fascinated by the relationship between public and personal lives — her own and others’ — Calle has often crossed boundaries of privacy. Frances Morris, commenting in Art Now, wrote that this fascination (or obsession):

“… Has led Calle to investigate patterns of behavior using techniques akin to those of a private investigator, a psychologist, or a forensic scientist. It has also led her to investigate her own behavior so that her live, as lived and as imagined, as informed many of her most interesting works.”

I like to imagine that Sophie Calle fictionalizes her life in some ways — not to dupe the viewer, but to gain the courage to behave in ways to advance her art. She may well have an alter ego — though the alter ego’s name is still Sophie Calle — that allows her to play a stripper, poke through strangers’ belongings, stalk acquaintances and then publicize the results, or create performances based on the private lives of others.

“Voyeurism, exhibitionism, and a needling strain of sadism course through Calle’s work, which is inescapably fascinating even as it’s ethically disturbing — and often quietly melancholic. She’s the artist as stalker, delving fearlessly into the minutiae of other people’s lives long before popular culture took up similar material in “reality” TV shows …” (David Rimanelli, Artforum)

The question becomes whether an artist who is so inventive and bold can remain relevant in the era of social media, in which everyone puts their own life up for grabs — or, as noted by David Rimanelli, above — reality TV, blogs, Instagram, TikTok, and other spaces in which private and public lives blur in today’s times.

Calle’s diaristic impulses foreshadowed the kind of self-revelation common to personal blogs and visual platforms like Instagram. These forms of social media allow anyone who wishes to participate to be both voyeur and exhibitionist; and they’ve become so pervasive in our culture that the subtle shock value of work like Calle’s, or any other artist whose works or performances deal in self-revelation may not seem like such a big deal to a new generation of viewers.

Of course, one might argue that blogs aren’t art, and appeal to a different audience, but they do epitomize the blurring of the private and public. Then, when art is presented purportedly doing the same thing, it may not seem as unique or thought-provoking as it once was.

It’s Calle’s aesthetic as a conceptualist that keeps her work stimulating for me. I love the bold grids of framed text juxtaposed with images, whether in installation or in the pages of a book. The idea matters, particularly in conceptual art, but ideas can become dated once their initial freshness, uniqueness, or even shock value diminishes.

The Detective, The Blind, and Exquisite Pain

The Detective, for example, doesn’t resonate with me as much as it did when I first encountered the series. That the arrangement of reams of text and pictures aren’t strikingly arranged doesn’t help. There’s little engagement to be had apart from the project’s concept, which, frankly, seems trivial and lacking in emotional content.

I react differently to the series of The Blind, however. There’s something compelling in the display of the words and images, and so much compassion in the photography of the sightless subjects. The concept of beauty, as presented in this series, comes off as simple, soothing, and universal.

Interest in artist’s books and fine editions is certainly strong and in this context, Calle’s work shines. Books on her work are a unique blend of monograph and finely produced limited edition. As described by Anna Gerber in The International Review of Graphic Design, the book version of Double Game “was that rare thing, an artist’s monograph that was actually a work of art in and of itself, a furthering of Calle’s vision rather than ‘just’ another exhibition spin-off.”

The book version of the conceptual exhibit Exquisite Pain can be described similarly. Photos I’ve seen of the exhibition installation seem quite striking, but it’s equally pleasurable to hold this chronicle of a broken heart in one’s hands. Yes, it’s a confessional, but like The Blind, has a sends of universality — who among us has not suffered a broken heart, and felt awfully sorry for ourselves over it? Calle’s interviews of people detailing the moment when they most suffered doesn’t trivialize the pain of a broken heart, but helps put it in perspective for herself and the viewer.

Delving into Double Game was for me a very rich and stimulating experience, but since it covers so much ground, it can be rather overwhelming to consider as a whole.

It’s more satisfying to think about Calle’s projects individually; less so through the all-encompassing lens of “Maria.” Though Maria comes off as bizarre and compulsive, Calle seems completely delighted to complete a circle of life imitating art that imitates life. Or vice versa.

Sophie Calle’s Double Game and Beyond

As that is somewhat the point: In Double Game, it’s hard to tell where life leaves off and art begins, and at what point art and life merge. In hear art and life Calle plays characters, some of whom are not who she is, but at other times, she’s playing a character whose persona is Sophie Calle. She’s not trying to dupe the viewer, but simply shooing different aspects of herself.

In a New York Times review of the Double Game exhibit, Grace Glueck wrote that “as a diarist, Ms. Calle’s amusingly deadpan, obsessively detailed reports on her activities have a certain fascination. But unfortunately she is no great shakes as a photographer, and the long sequences of shots documenting her actions are less than compelling.”

The latter, I suspect, describes The Detective, and Suite Venetienne, which I agree aren’t her strongest concepts or presentations. Other critics have described her photography as unremarkable, but then, Calle doesn’t pretend to be an accomplished photographer.

Glueck also suggests that someone who lives so vicariously is to be pitied, perhaps momentarily forgetting that this is not Calle’s life but her art, and that sometimes her life is her art. It’s as if there is no longer a real Sophie Calle, but merely a Sophie Calle simulacrum.

If Calle’s work can be put in a nutshell, it might be the exploration of public lives and private selves. Though an age-old idea, it resonates because we all long to connect with other human stories. Much as I admire her work, I found myself a bit more uncomfortable with some of her projects than I was when I first encountered them.

At a time when all of us are faced with disturbing governmental and corporate intrusions into privacy, somehow, I didn’t findThe Address Book,Suite Venetienne, or The Hotel as clever and amusing as I once did. I don’t want the government prying into my private life; why is it better when done in the name of Art?

I haven’t kept up with Sophie Calle for some time, aside from retrospectives and the continuing travels of Exquisite Pain. I’m curious to see what will come next, as she is a great talent and remarkably inventive.

Has she had to step back and pause to consider how to proceed in an era when self-revelation is commonplace and spying is considered reprehensible? More likely, she’s working on a way to reinvent the persona of Sophie Calle so that she can do what she seems to love best — indulge in her obsessions.

Find views and lives outside the strictly literary realm in Other Voices on this site.

The post Sophie Calle and Double Game: Is Artistic Voyeurism Ethical and Relevant? appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 7, 2024

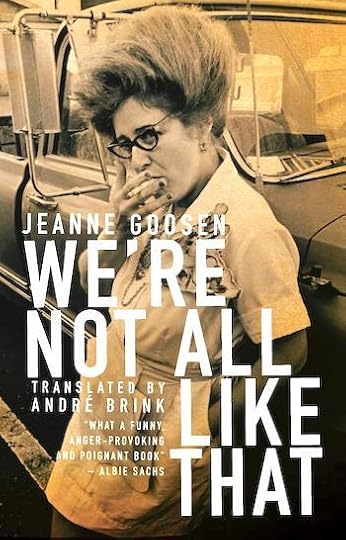

Jeanne Goosen, Author of We’re Not All Like That

Jeanne Goosen (July 13, 1938 – June 3, 2020) was a South African author, poet, and journalist. Her novel We’re Not All Like That (1990) explored the average Afrikaner household, pushing the boundaries of what could be said in fiction through the lead character of Doris van Greunen.

At the age of twelve, Goosen published her first short fiction in the Afrikaans lifestyle magazine Rooi Rose (Red Roses).

Goosen cited Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky as her first writing inspiration; she said that this book shook her deeply.

Jeanne Goosen’s first publicationsIn 1971, Goosen published her debut poetry collection An Owl Flies Away (`n Uil vlieg weg), followed by Organ Pipes (Orrelpunte) in 1974. At the same time, she worked as a journalist for the Paarl Post, Tempo, and other local newspapers.

Goosen also worked in fishing and on a citrus farm to supplement her writing income. In the 1980s, she moved to the coastal Kwazulu-Natal province. She was also a frequent traveler and spent a substantial amount of time in Gauteng and the Cape.

A Cat in the Bag (`n Kat in die sak) collected approximately a decade’s worth of stories in 1986, including the eponymous story of a stray cat foundling in a tied up bag.

Many of her stories explored human life from an animal perspective, or from people living around animals. Animals were integral to her life, and she was almost always surrounded by her pets. Goosen would say that dogs are kind enough to “trade their souls for a piece of dried sausage.”

We’re Not All Like That (1990) is her only fully translated work. The novel “tells the story of how Doris van Greunen tries to break free of her world: with her job as an usherette at the bioscope, with her Cavallas, with friends like Aunt Mavis and Uncle Tank – and with Barnie, the swank.”

The book describes life in a small, average Afrikaner family, a topic seldom touched upon even for Afrikaans authors of the time. About the novel, she said:

“I almost laughed myself to death over the manuscript, because I thought that it was funny. Because I thought how people are going to react to it, with this that it thundered against everything written in Afrikaans literature at the time.”

Goosen loved pushing boundaries with her work, developing a love for surreal situations intermingled with relationships between friends, families, and their pets.

Goosen’s publications in the 1990s

Goosen was an award-winning author throughout her career but found herself conflicted about literary prizes. In 1991, she won R50,000 (approximately 2,700 USD) for the M-Net Prize, calling it “horribly wonderful.”

She also admitted that literary prizes came with an edge, and gave “others an excuse to shit on your head.”

In 1992, she received the Helen Martins Prize, using the money to live in playwright Athol Fugard‘s home in Nieu-Bethesda for thirty days. (Sarie, 2021) Next, Goosen wrote the one-act play Kitchen Blues (Kombuisblues), which was performed internationally in London, Brussels, and other locations.

Goosen was known for eccentricities and quirks by friends and literary acquaintances. In an interview for Vrye Weeksblad, she was greeted by the interviewing journalist – and a six-pack of Amstel Lager beers.

Daantjie Dreamer (1993) was her next work of longer fiction, academically praised for its focus on liminality (or transitional stories, like coming-of-age tales). Again, Goosen returned to the setting of an average Afrikaner family, this time in the 1950s, through the perspective of Bubbles, who questions the values and traditions of her household.

She continued writing poetry and essays in her lined notebooks, including the translated “Hoedlied” (“Hat Song”).

. . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

6 Notable South African Poets

. . . . . . . . . .

In 2001, Goosen moved “between Brits and Pretoria North,” seeking a pet-friendly home to accommodate her beloved dogs.

Goosen had learned the piano at eight years old, and later the clarinet, though would only continue playing for her own entertainment (and once or twice for a friend’s book release as a rare appearance). Music remained an important part of authorship. She co-wrote a cabaret titled Thief of Hearts (Hartedief) with Deborah Steinmair, performed in 2004. Thief of Hearts explored the story of conjoined twins who could both carry a tune.

A Pawpaw for My Darling (`n Pawpaw vir my darling), published in 2006, explored the suburb of “Damnville.” It was based on the real-life area of Danville in Pretoria. Bits of the story are told through the perspective of the family dog, who gives its thoughts as an external observer.

In a 2007 interview, Goosen noted, “Humor is part of a person’s survival kit. It makes everything more tolerable.” In the same interview, she quipped that she “liked animals more than people” because they cheered her up.

More poetry appeared in 2007, called on duty elsewhere (elders aan diens). On rare occasions, the poem My Mum’s Bonkers (My ma is bossies) has been translated and adapted.

A Pawpaw for My Darling was adapted to film in 2015. The film is in Afrikaans, but subtitled for English-speaking viewership (Review, News24).

Plants Can Talk (Plante kan praat, 2010) continued her exploration of surrealist themes blended with everyday situations. She joked that some critics had been gossiping about her mental state after its publication: “First, Jeanne’s animals started talking, and now her plants!”

Loose Thoughts (Los Gedagtes) was compiled by Petrovna Metelerkamp in 2019 from some of her most personal writing notebooks.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The legacy of Jeanne GoosenJeanne Goosen died in 2020 at age 81, in Melkbosstrand, Cape Town. After her death, some of her notebooks were discovered and published as Snow in the Karoo. The volume also contains writings by her aid Agnes Morao, published alongside the novel as Agnes’ Book. Research on publication showed that Agnes died in 2003.

Goosen was also a prolific letter writer; some of her correspondence and photographs were compiled by Petrovna Metelerkamp for A Life Full of Sentences (`n Lewe vol sinne).

Today, Jeanne Goosen remains one of the most prominent surrealist authors and poets in South African literature.

Contributed by Alex Coyne, a journalist, author, and proofreader. He has written for a variety of publications and websites, with a radar calibrated for gothic, gonzo and the weird. His features, posts, articles and interviews have been published in People Magazine, ATKV Taalgenoot, LitNet, The Citizen, Funds for Writers, and The South African, among other publications.

The post Jeanne Goosen, Author of We’re Not All Like That appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 31, 2023

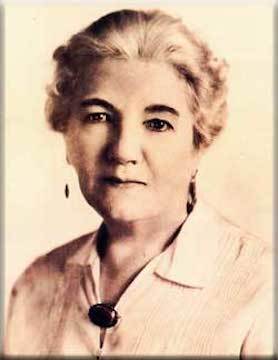

Enid Blyton’s Top 5 Series: Mystery, Adventure & More

Enid Blyton (1897 – 1968) is one of the world’s most successful and prolific children’s authors. She wrote some seven hundred full-length books, many of which have never been out of print. Here is a selection of Blyton’s top 5 series.

Despite controversy over the literary merit of some of her work, including the use of outdated and offensive language, she remains one of the world’s most popular fiction authors, coming sixth in an all-time bestselling list by estimated sales (behind William Shakespeare, Agatha Christie, Danielle Steel, Harold Robbins, and Dr. Seuss, and well ahead of J.K. Rowling at number 10).

Her books were intended for children between the ages of about three and twelve, and many were part of a series — one of the most popular being “The Famous Five.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Enid Blyton

. . . . . . . . . . .

Blyton aficionados will have personal favorites; these are some of the many titles continuing to be reprinted and enjoyed today (and are a good place to start if you’re new to Blyton’s books).

. . . . . . . . . . .

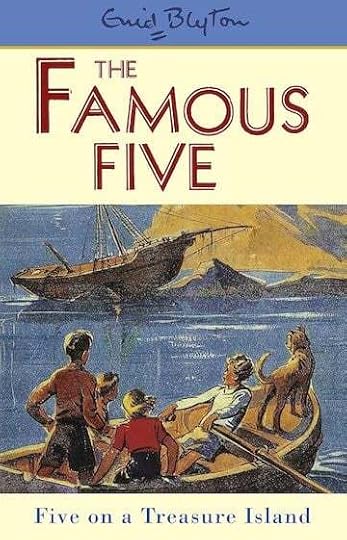

The Famous Five

“The Famous Five” are Julian, Dick, Anne, and their cousin George (full name Georgina — but don’t ever call her that!), along with Timmy the dog.

Their adventures began in 1942 with Five on a Treasure Island, and a further twenty thrilling escapades followed until the final book in the series, Five Are Together Again, was published in 1963. Blyton also wrote several short stories featuring the same characters.

The children spend their holidays camping and exploring by themselves, finding plenty of mysteries along the way — and, of course, always with a good supply of sandwiches and ginger beer.

The places in the books are based largely in the southwest of England, from Dorset to Cornwall, and feature Kirrin Island, Smuggler’s Top, Demon’s Rocks, as well as remote farms, ruined castles, and caves.

The original books were illustrated by Eileen Soper; more recent editions have been illustrated by Pippa Curnick and Sir Quentin Blake.

Minor amendments have been made to the text over the years as part of an editorial process aimed at eliminating or altering the offensive and outdated language in the original versions (especially with regard to race and gender). Still, the books have never been out of print, and the series still sells around 250,000 copies per year.

Several television adaptations have also been made, and a new miniseries based on the books (titled The Curse of Kirrin Island) was broadcast on the BBC in December 2023. In addition, continuation novels have been written by Claude Vollier and Mary Danby; in 2000, six “Just George” books were published, written by Sue Welford.

Other spin-offs include The Famous Five Adventure File, The Famous Five Diary, and The Famous Five’s Survival Guide, along with various puzzles and games and a Famous Five Treasury.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Secret Seven

The Secret Seven Society is made up of Peter and his sister Janet, along with their friends Jack, Colin, George, Pam, and Barbara (and golden spaniel Scamper).

Together they investigate unusual goings-on in the local community— burglaries, missing people, and stolen animals. They’re experts in hunting for clues, shadowing suspicious people, and keeping watch.

All Secret Seven meetings take place in a shed with S.S. on the door; admission is only granted with the correct password, and membership badges must be worn.

The first in the official series of fifteen books, The Secret Seven, was published in 1949, although Peter and Janet had appeared in two earlier stories, At Seaside Cottage (1947) and The Secret of the Old Mill (1948).

In the 1970s and 1980s, Evelyne Lallemand wrote several continuation novels, and in 2019–2020 two new Secret Seven mysteries were published, written by Pamela Butchart: The Mystery of the Skull and The Mystery of the Theatre Ghost.

Original illustrations were by George Brook, Bruno Kay, and Burgess Sharrocks. Since 2013, editions have been released by Hachette with illustrations by Tony Ross.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Malory Towers

This ever-popular school series was first published in 1946. The original series consisted of six books, one for each year of heroine Darrell River’s time at Malory Towers boarding school. A further six continuation novels were published in 2009, written by Pamela Cox.

Malory Towers is a girls’ school set on the cliffs in Cornwall: a picturesque castle with four round towers, a courtyard, and a seawater-filled swimming pool surrounded by the rocks.

Darrell (named after Enid Blyton’s second husband, Kenneth Darrell Waters) desperately wants to make a success of her time at the school, but between her hot temper and the antics of her classmates — clever and funny Alicia, spiteful Gwendoline, dependable Sally, and meek Mary-Lou — things don’t always go as planned.

It’s a world of midnight feasts in the dorms, lacrosse games, practical jokes, friendship and rivalry, and the challenges of school.

In 2019, Hachette published a book called New Class at Malory Towers containing four short stories by different authors (Narinder Dhami, Patrice Lawrence, Lucy Mangan, and Rebecca Westcott). In 2020, CBBC produced a television adaptation of the original books.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Noddy

Noddy is still probably the most famous character to be associated with Enid Blyton, although he admittedly does have something of the ‘Marmite effect’ — people either seem to love him or loathe him.

Noddy is a little wooden toy created by Old Man Carver. He’s sent off to Toyland, where his adventures promptly begin along with other toys: Big Ears, Tessie Bear, Bumpy Dog, and PC Plod. Noddy has a house of his own and a stylish little red and yellow car, while his best friend Big Ears lives under a perfect spotted toadstool.

The first Noddy book, Noddy Goes to Toyland, was published in 1949 (illustrated by Harmsen Van Der Beek), and a further 24 original books were published before the last, Noddy and the Aeroplane, appeared in 1963.

Over the years, there has been a wealth of Noddy merchandise including Noddy soap, Noddy bedlinen, Noddy toothbrushes and toothpaste, Noddy pajamas, and Noddy bedside lights, as well as varying spin-off books including hard books and pop-up books.

There have also been several television series made (the image of which generally bears little resemblance to Blyton’s original work and the original illustrations).

Like “The Famous Five” the Noddy books have never been out of print, but have undergone a clean-up process of changing or eliminating some of the racist and sexist language in the originals.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Faraway Tree

The Faraway Tree is a huge tree in the middle of the Enchanted Wood, laden with fruit of all kinds and home to the fairy folk. The uppermost branches of the tree lead to the ever-changing magical lands above the clouds.

When Jo, Bessie, and Fanny come to live at the edge of the wood, they discover the Faraway Tree and make friends with Moon-Face, Mister Watzisname, Silky the Fairy and the Saucepan Man.

Days are spent climbing the tree – which involves avoiding the dirty water that Dame Washalot pours down the trunk, and trying to ignore the Angry Pixie – and exploring the Land of Take-What-You-Want, the Land of Topsy-Turvy, the Land of Spells, and the Land of Goodies.

The Faraway Tree made its first appearance in The Yellow Fairy Book (now published as The Magic Faraway Tree: Adventure of the Goblin Dog) in 1936, and the first in the main trilogy, The Enchanted Wood, was published in 1939. It was followed by The Magic Faraway Tree in 1943, and The Folk of the Faraway Tree in 1946.

At some point in the editorial process, the names of the children were changed from Jo, Bessie, and Fanny (and their cousin Dick) to Joe, Beth, Frannie, and cousin Rick. These changes have been kept throughout subsequent editions of the books.

In 2022, celebrated children’s author Jacqueline Wilson wrote a new book in the series, The Magic Faraway Tree: A New Adventure, featuring three contemporary children Milo, Mia and Birdy, who follow in Jo, Bessie, and Fanny’s footsteps in discovering the Faraway Tree.

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

A few more Enid Blyton series

Enid Blyton wrote an enormous number of series for different ages, so if none of the above takes your fancy then maybe another will! Others still in print include:

The St, Clare’s books, which follow the school adventures of twins Pat and Isabel O’Sullivan.The Naughtiest Girl books, in which spoiled Elizabeth is sent away to Whyteleafe school, and makes up her mind to be the naughtiest pupil ever.The Mystery Series, in which Fatty, Larry, Daisy, Pip, Bets, and Buster the dog solve mysteries much like the Secret Seven.The Secret Series, in which adventure and mystery go hand in hand for Jack and his friends Mike, Peggy and Nora.More about the Blyton controversies

Why it’s Important to Note Enid Blyton’s Failings, Not Erase Her Work When the Past Clashes with the Present: Reminiscences of Enid Blyton English Heritage Has No Plans to Remove PlaqueThe post Enid Blyton’s Top 5 Series: Mystery, Adventure & More appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 27, 2023

The Little House books by Laura Ingalls Wilder

The Little House books by Laura Ingalls Wilder are autobiographical series of novels for children reflecting her life on the American frontier. Though beloved by generations of young readers, they haven’t been without controversy, as we’ll soon discover.

Wilder (1967–1967) wrote these vivid tales — nine in the Little House series — that immediately appealed to readers of all ages. The books were an immediate critical and popular success, winning numerous awards and making their way into readers’ hearts with their message of endurance, simple living, and love of family.

Born in a log cabin on the edge of an area called “Big Woods” in Pepin, Wisconsin, Laura’s real-life experiences were the inspiration for her novels, and richly informed her memoirs as well.

The Ingalls family traveled by covered wagon through Kansas and Minnesota with all that they owned, until finally settling in De Smet, Dakota Territory. The family loved the open spaces of the prairie. They moved around quite a bit, and though it wasn’t an easy life, it gave Laura a rich trove of memories and experiences to draw upon when she began writing.

The first of the Little House books, Little House in the Big Woods, was published in 1932; Laura was in her mid-sixties at the time. The best known volume of the series, Little House on the Prairie, was published soon after.

The family depicted in the stories was an idealized version of the one she grew up in. The Little House books tell of this family, not unlike her own, pioneering the Great Plains in the mid-1800s.

In the 1920s, Laura got encouragement from her daughter Rose as well as the time she needed to start writing.Though presented as fiction, the author insisted, “I lived everything I wrote.”

The books were the basis of the long-running TV series titled Little House on the Prairie.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Laura Ingalls Wilder

. . . . . . . . . . .

Accusations of racial insensitivity have been leveled at the Little House books and their author. In an article in Smithsonian magazine timed for Laura’s 150th birthday — “Little House on the Prairie was Built on Native American Land” —it’s suggested that “It’s time to take a critical look at her work.”

Many readers are unhappy about this, suggesting that she was merely “a woman of her time.” But the article argues:

“Portrayals of Native American characters in this book and throughout this series have led to some calls for the series to not be taught in schools.

In the late 1990s, for instance, scholar Waziyatawin Angela Cavender Wilson approached the Yellow Medicine East school district after her daughter came home crying because of a line in the book, first attributed to Gen. Phil Sheridan, but a common saying by the time: ‘The only good Indian is a dead Indian.’ Her story gained national attention.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Photo by Anna Fiore

. . . . . . . . . .

Here are the books in the series, described by the publisher, Harper Trophy, in order of publication:

Little House in the Big Woods (1932)

Meet the Ingalls family—Laura, Ma, Pa, Mary, and baby Carrie, who all live in a cozy log cabin in the big woods of Wisconsin in the 1870s. Though many of their neighbors are wolves and panthers and bears, the woods feel like home, thanks to Ma’s homemade cheese and butter and the joyful sounds of Pa’s fiddle.

Little House on the Prairie (1935)

When Pa decides to sell the log house in the woods, the family packs up and moves from Wisconsin to Kansas, where Pa builds them their little house on the prairie! Living on the farm is different from living in the woods, but Laura and her family are kept busy and are happy with the promise of their new life on the prairie.

On the Banks of Plum Creek (1937)

The Ingalls family lives in a sod house beside Plum Creek in Minnesota until Pa builds them a new house made of sawed lumber. The money for the lumber will come from their first wheat crop. But then, just before the wheat is ready to harvest, a strange glittering cloud fills the sky, blocking out the sun. Millions of grasshoppers cover the field and everything on the farm, and by the end of a week, there is no wheat crop left.

By the Shores of Silver Lake (1939)

Pa Ingalls heads west to the unsettled wilderness of the Dakota Territory. When Ma, Mary, Laura, Carrie, and baby Grace join him, they become the first settlers in the town of De Smet. Pa starts work on the first building of the brand new town, located on the shores of Silver Lake.

The Long Winter (1940)

The first terrible storm comes to the barren prairie in October. Then it snows almost without stopping until April. With snow piled as high as the rooftops, it’s impossible for trains to deliver supplies, and the townspeople, including Laura and her family, are starving. Young Almanzo Wilder, who has settled in the town, risks his life to save the town.

Little Town on the Prairie (1941)

De Smet is rejuvenated with the beginning of spring. But in addition to the parties, socials, and “literaries,” work must continue. Laura spends many hours sewing shirts to help Ma and Pa get enough money to send Mary to a college for the blind. But in the evenings, Laura makes time for a new caller, Almanzo Wilder.

These Happy Golden Years (1943)

Laura must continue to earn money to keep Mary in her college for the blind, so she gets a job as a teacher. It’s not easy, and for the first time she’s living away from home. But it gets a little better every Friday, when Almanzo picks Laura up to take her back home for the weekend. Though Laura is still young, she and Almanzo are officially courting, and she knows that this is a time for new beginnings.

The First Four Years (1971))

Laura Ingalls and Almanzo Wilder have just been married! They move to a small prairie homestead to start their lives together. But each year brings new challenges—storms, sickness, fire, and unpaid debts. These first four years call for courage, strength, and a great deal of determination. And through it all, Laura and Almanzo still have their love, which only grows when baby Rose arrives.

Often added to the series is this entry, based on her husband’s early years, which was actually the second book published:

Farmer Boy (1933)

As Laura Ingalls is growing up in a little house in Kansas, Almanzo Wilder lives on a big farm in New York. He and his brothers and sisters work hard from dawn to supper to help keep their family farm running. Almanzo wishes for just one thing—his very own horse—but he must prove that he is ready for such a big responsibility.

. . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

Caroline: Little House, Revisited by Sarah Miller

The post The Little House books by Laura Ingalls Wilder appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 18, 2023

Kathleen Raine – British Poet, Scholar, and Mystic

Kathleen Raine (June 14, 1908 – July 6, 2003) was a British poet, scholar, and mystic. She is also remembered as a William Blake scholar, and wrote extensively on W.B. Yeats and Thomas Taylor as well.