Nava Atlas's Blog, page 12

March 6, 2024

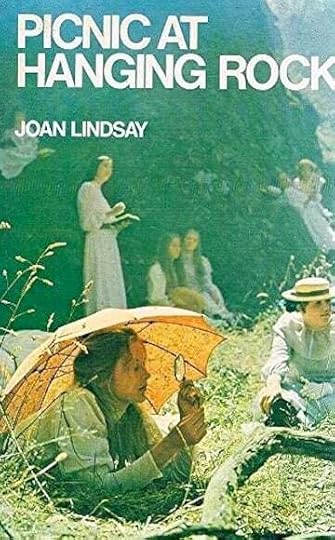

Joan Lindsay, Author of Picnic at Hanging Rock

Joan Lindsay (November 16, 1896 – December 23, 1984) was an Australian author, essayist, and visual artist, best known for her mystic novel Picnic at Hanging Rock.

She began her literary career at forty years old when Through Darkest Pondelayo (1936) was published. Picnic at Hanging Rock (1966) was published when she was seventy-one.

Early Life

She was born Joan à Beckett Weigall in East St Kilda in Victoria to an upper-class Edwardian family. Her father Sir Theyre à Beckett Weigall was a judge and her mother Annie Sophie Henrietta was the daughter of Sir Robert Hamilton, the governor of Tasmania.

She attended Clyde Girls Grammar School, a private girls’ school, which she used as inspiration for the Appleyard College in Picnic at Hanging Rock.

Joan describes herself as having an “extraordinary memory of her youth” and recounts her first word, “beautiful,” as she stood in a garden of pansies at only three years old. Her “gloriously eccentric” childhood was filled with fascinating visitors to her home like the anthropologist Baldwin Spencer, literary scholar Sir Archibald Strong, and her cousins Panleigh and Merric Boyd who both went on to be celebrated artists.

Joan studied painting at the National Gallery of Victoria Art School. While she continued to paint throughout her life, she never pursued it professionally. In part, this decision was made because she felt she could not express herself well enough through painting. This realization sparked her decision to become a writer – a medium in which she could better express herself.

. . . . . . . . . .

Joan in 1914

. . . . . . . . . .

From a young age, Joan knew she wanted to marry into the Lindsay family. Irish-born Dr. Robert Lindsay and his wife Jane had ten children. Five of those ten brought the family to prominence because of their careers in art and literature.

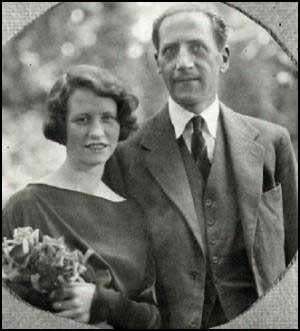

Joan got her wish when she eloped with Daryl Lindsay in London on St. Valentine’s Day 1922. Their marriage made waves . Those in her milieu could not understand why she would marry such a bohemian, but Joan was not phazed. She likened herself more to the Bloomsbury Group than her establishment family.

Eccentric Beliefs

St. Valentine’s Day was special to Joan. In addition to it being her anniversary, it’s the same day that she set the events in her novel, Picnic at Hanging Rock.

“Daryl and I were married in London on St Valentine’s Day nineteen hundred and twenty-two – the only date I have ever remembered, except 1066 and Waterloo,” said Joan. She even had an extensive collection of intricately handmade Valentine’s Day cards.

Joan had an unconventional, free-spirited, attitude toward time, often disregarding it completely. Time was often a theme she played with in her writing. In a 1973 interview, she said, “I have an extraordinary gift, you might call it a very sinister one of stopping people’s watches just by sitting beside them.” She elaborated on her relationship with time:

“I’ve been terribly interested in time, always; I always felt that it was something that was all around one. Not just in a long line in a calendar. I feel that one’s in the middle of time and that the past, present, and future is all around and I’m in the middle of it.”

Joan balanced her eccentricities with the demeanor of a high-society woman of the early 1900s. In interviews, she can be seen wearing pearls, and had a polite and measured way of speaking. Yet at the same time, she had an air of mystery and youthfulness.

Janelle McCullough, author of Beyond the Rock: The Life of Joan Lindsay said in an ABC radio interview, “She was enigmatic, she loved a mystery, she was herself a mystery … she was a mystic. She was able to see things we can’t.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Joan and Daryl Lindsay

. . . . . . . . . .

Her first novel, Through Darkest Pondelayo (1936), tells the story of two women on a fantastic adventure to the eponymous fictional cannibal island. Written in the style of journal entries or letters back home, the novel was published under a pseudonym, adding to the immersive experience.

The satirical novel featured photographs of the characters in comical situations and intentional errors in the writing to give the feeling of a real travelogue. A review of the novel wrote that the publishers “entered fully into the spirit of the thing, presenting the book on exaggeratedly thick paper in the true manner of offering a book of tremendous importance.”

There were no other novels until Time Without Clocks (1962) and Facts Soft and Hard (1964), but in these intervening years Joan was a prolific essayist and contributor to journals.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Picnic at Hanging Rock (1967)Picnic at Hanging Rock was her biggest success and became a cult classic. In the year 1900, students at Appleyard College set out on a Valentine’s Day picnic at the geologic wonder, Hanging Rock.

The book is an ode to femininity, with men only featured as secondary characters, as well as to the natural world. The mood shifts after the disappearance of three of the girls who wandered further up the rock.

The novel follows the aftermath and ripple effect of this event on the school, the other students, and the rural town that neighbors the school. The book was met with much praise but also some confusion, as Joan offers no satisfying ending to her mystery, but instead invites readers to indulge in mystery itself.

In 1975 Peter Weir directed the iconic, stunning film version of Picnic at Hanging Rock.

Before publishing Hanging Rock, Joan removed the final chapter of the book on an editor’s suggestion. This chapter displays her fascination with space and time as she explains the girls’ disappearance through a supernatural hole in time. This chapter was published posthumously as The Secret of Hanging Rock (1987).

Later Life

Joan continued writing and living in her beloved Victoria home, Mulberry Hill. Syd Sixpence (1982), a children’s book published when she was eighty-six, was her last full-length work.

After she died of stomach cancer in 1984, her home was gifted to the National Trust. Today, people can visit, as well as take the writing workshops at the house that inspired Time Without Clocks.

“In the studio at Mulberry Hill we discovered that cut flowers have an astonishing range of movement, turning their heads, slipping in and out of water, drooping, straightening, flinging themselves clean out of the container. Buds open and shut while you wait, or drop off, leaves uncurl. Certain flowers placed in the same vase with incompatibles will keel over and die, while the gentle lily, well known to painters for its persistence in following the light, can wreck a carefully arranged bunch overnight, unless it is stored in a darkened room.” (—Time Without Clocks, 1962)

More about Joan LindsayMajor works by Joan Lindsay

Through Darkest Pondelayo (1936)Time Without Clocks (1962)Picnic at Hanging Rock (1967)Syd Sixpence (1982)The Secret of Hanging Rock (1987)Further reading

Australian Dictionary of Biography University of Queensland Interview with Joan Lindsay Beyond the Rock: The Life of Joan Lindsay by Janelle McCullochThe post Joan Lindsay, Author of Picnic at Hanging Rock appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 1, 2024

Madame de Staël, French Political Theorist & Woman of Letters

Madame de Staël (April 22, 1766 – July 14, 1817) was a French intellectual, writer, and political theorist. She was a staunch supporter of freedom of speech, democracy, women’s rights as well as a political enemy of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Looking at Germaine’s portrait, with her grandiose turban, silk gown, and shawl draped over her arms, the last thing she brings to mind is an 18th-century French revolutionary, but that is precisely what she was.

The author Francine du Plessix Gray called Germaine “the first modern woman.”

Early Life

She was born Anne Louise Germaine Necker in Paris to wealthy Swedish parents Jacques Necker and Suzanne Curchod. Her father was Louis XVI’s Minister of Finance; her mother hosted a salon where she entertained guests including Edward Gibbon, Voltaire, and Diderot.

A precocious only child, Germaine was allowed to attend her mother’s salons. Protestant and forward-thinking for their day, her parents believed she should be educated in all subjects, and allowed for the influence of Dante, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Shakespeare in her studies.

At the age of twenty, she began to publish her work, starting with the novels Sophie (1786), Jeanne Grey (1790), and Lettres sur J.J. Rousseau (1788).

It was a time of political turbulence in France. Germaine’s father was forced into exile due to financial mistakes, political opposition, and Marie Antoinette’s animosity. While most would have been sent to prison for such offenses, it’s likely he was given the lesser punishment of exile because he had loaned the national treasury 2.5 million livres. The family fled to their chateau, Coppet, on Lake Geneva in Switzerland.

Marriages and Children

When the family returned to France in 1785, their focus was on a marriage for Germaine. Even as a teenager, she had received marriage proposals, which were promptly turned down by her family.

She was married off to Eric Magnus, Baron of Staël-Holstein, an attaché of the Swedish government who had been promised an ambassadorship to France and a pension by the King of Sweden. Together they had three children – sons August and Albert and a daughter Albertine (though is widely believed that Albertine was actually the daughter of Benjamin Constant, rather than of Baron Staël-Holstein)

Young Germaine had the money, and the Baron had the political stature. It wasn’t a match made in heaven, though it was mutually beneficial to their social status. This marriage ended when Baron Staël-Holstein died in 1802.

She then started a serious relationship with political activist and author Benjamin Constant. Though they never married, they were a politically-minded power couple. Constant once wrote about her, “If she knew how to rule herself, she would rule the world.” It is widely believed that Albertine, was actually Constant’s daughter rather than Baron Staël-Holstein’s. Germaine and Constant separated when he married Charlotte von Hardenberg in 1808.

She remarried in 1816 to the much younger Swiss soldier Albert Jean Michel de Rocca. Together they had a son, Louis-Alphonse de Rocca.

. . . . . . . . . .

Germaine and her daughter, Albertine

. . . . . . . . . .

In the early days of the revolution, Germaine lived in Paris, attending the National Assembly, writing, and cheering the fall of Louis XVI.

She hosted an influential salon whose guests included Thomas Jefferson, Marquis de Lafayette, and the philosopher Thomas Paine. Politically, she sided with the radical Jacobins who wanted a parliamentary monarch. However, she gradually moved toward the more moderate Girondists.

In 1793 the Reign of Terror began with mass killings as the Jacobins purged the Girondists. With the help of her father, she escaped to the chateau in Switzerland. In 1795, when the political climate relaxed she returned to Paris.

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte assumed power in 1799. From the start, Germaine and Napoleon disliked one another. The future self-crowned emperor took issue with her political work, partly because she opposed him, and also because he didn’t like outspoken women in political roles. He once told a colleague he wished she would stick to her knitting.

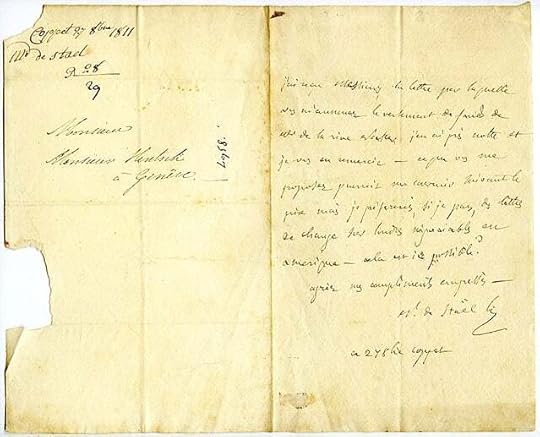

The pas de deux between the two lasted for a dozen years, as she was forced into exile from time to time. She was always writing, always influencing, always lambasting his tyranny and despotism; perhaps she contributed to his eventual downfall. Germaine was the thorn in Napoleon’s side.

Napoleon censored her books Corinne or Italy and De l’Allemagne after she published them in France. He then exiled her from Paris and further retaliated by banishing anyone who visited her in Switzerland.

Exile and InfluenceEven in exile, Germaine was highly influential. Her salon at Coppet, which Stendhal said was the “general headquarters of European thought,” was visited by Francois-Rene de Chateaubriand, Lord Byron, and Prince Augustus of Prussia.

In her years of exile, she traveled to Austria, Germany, Russia, Sweden, England, Italy, and Turkey – always writing, always socializing. She met with Czar Alexander to talk politics, influencing treaties between Russia and Sweden as well as England and Prussia. After the English defeated France at Waterloo, she convinced the Duke of Wellington to decrease the presence of his Army of Occupation in France.

. . . . . . . . . .

Letter written by Germaine de Staël

. . . . . . . . . .

Germaine was a major talent and has been nearly forgotten, unlike her contemporary, Jane Austen. She epitomized romanticism in French literature — the emotional, the lyrical, and the autobiographical. She wrote essays, plays, political treatises, and travelogues, and a memoir of her years in exile. Her novels were often translated and read widely.

In addition to politics, she wrote on controversial topics like adultery, suicide, and even a defense of Marie Antoinette. Over time, she influenced writers like Henrik Ibsen, Herman Melville, Harriet Beecher Stowe, George Eliot, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, to name a few.

By 1814 the Bourbons had been restored to power and Louis XVIII was on the throne. By then, she returned to Paris, converted to Catholicism, and after a seizure, was paralyzed.

Madame Germaine de Staël died on July 14, 1817, of a brain hemorrhage. Poetically, her death came on Bastille Day, a holiday that marks the beginning of the French Revolution — when the people triumphed over tyranny.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Tyler Scott, who has been writing essays and articles since the early 1980s for various magazines and newspapers. In 2014 she published her novel The Excellent Advice of a Few Famous Painters. She lives in Blackstone, Virginia where she and her husband renovated a Queen Anne Revival house and enjoy small town life.

. . . . . . . . .

Memorable quotes by Madame Germaine de Staël“Love is the whole history of a woman’s life; it is but an episode in a man’s.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Happiness is a wondrous commodity. The more you give, you more you have.”

. . . . . . . . .

“A religious life is a struggle and not a hymn.”

. . . . . . . . .

“One must choose in life between boredom and suffering.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Exile: A tomb in which you can get mail.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Intellect does not attain its full force unless it attacks power.”

. . . . . . . . .

“The more I see of men the more I like dogs.”

. . . . . . . . .

Further reading

Fairweather, Maria. Madame de Stael. London: Constable, 2005. Du Plessix Gray, Francine. Madame de Stael: The First Modern Woman. New York: Atlas, 2009. De Stael, Germaine. Corinne, or Italy, available in Oxford Word’s Classics, Oxford University Press.Sources

The Encyclopedia Britannica, Chicago, 1952.Watkin, Amy. Germaine de Stael: Napoleon’s Worst Enemy. McSweeney’s, Nov. 19, 2015.Halstead, Susan. Coppet, Constant, and Corinne: The Colorful Life of Madame de Stael. British Library Blog, July 2017.Holmes, Richard. The Great de Stael, The New York Review, May 2009.Schiff, Stacy. The Secret of Madame de Stael’s Success, Slate, Oct. 2008.Bedell, Geraldine. Napoleon’s Nemesis (review of Madame de Stael by Maria Fairweather). The Guardian, Feb. 2005.Escarpit, Robert. Germaine de Stael, French-Swiss Author. Britannica (online).A Short History of Germaine de Stael, The Connexion, Dec. 2020.Wiener, James Blake. Madame de Stael- Enemy of Napoleon, Swiss National Museum blog, May 2021.The post Madame de Staël, French Political Theorist & Woman of Letters appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 15, 2024

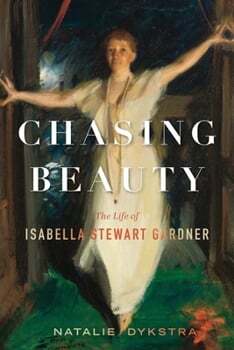

10 Fascinating Facts About Isabella Stewart Gardner

Chasing Beauty: The Life of Isabella Stewart Gardner (Mariner Books, March 2024), award–winning author Natalie Dystra delivers the definitive biographical portrait of the ambitious and innovative—and until now misunderstood—woman behind one of America’s most important art collections.

With access to all archival holdings at the Isabella Stewart Garner Museum—including thousands of digitized and newly accessible letters and other unpublished records—as well as original sources in Paris, Venice, and more. Dykstra brings Isabella to life as never before.

An incredible achievement of storytelling and scholarship, Chasing Beauty illuminates the fascinating ways the museum and its holding can be seen as a kind of living memoir—how Isabella “put herself on display… her taste, her passions, her sorrow, her nerve, her capacious curiously, relationships,” Dykstra reveals.

Isabella’s meticulous curation of the exhibits became her voice, enabling her story to be told through the objects she cherished most.

Enjoy the following fascinating facts about the life of the American art collector Isabella Stewart Gardner, excerpted from material provided by Mariner Books, the publisher of Chasing Beauty by Natalie Dykstra.

. . . . . . . . . .

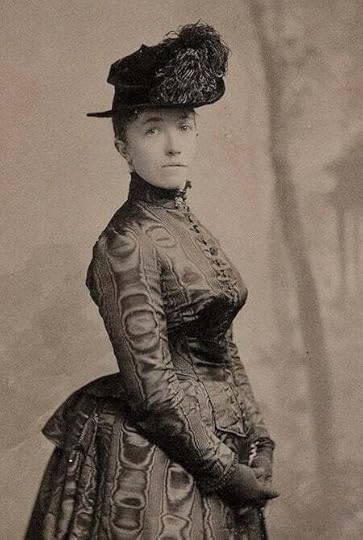

Isabella Stewart Gardner in 1888

. . . . . . . . . .

Before her marriage to Jack, her childhood was spent in New York and Paris where she studied art, music, dance, French, and Italian. Provided with a picture of her childhood, one begins to understand why the spirted, original, sophisticated young Isabella (known then as Belle) was not later embraced by Boston society.

She had a competitive, simpatico relationship with John Singer Sargent

Together Gardner and Sargent—considered the most successful portrait painter of his time—constructed quite the scandal surrounding his iconic 1888 portrait. Jack Gardner said to his wife at the time. “It looks like hell, but it looks like you.”

Isabella was an entrepreneur

Much attention has been devoted to how Isabella used glamour and even scandal to assert her cultural position. Chasing Beauty shows how the public performance was in many ways a screen for her more serious, radical work of competing as a connoisseur/collector in order to create her sui generis museum.

. . . . . . . . . .

“Mrs. Gardner in White” by John Singer Sargent (1922)

. . . . . . . . . .

She had a fraught but essential relationship with Bernard BerensonJack Gardner came to mistrust Berenson, the brilliant historian of the Italian Renaissance, for his lack of transparency in business matters. Isabella, however, knew how to parry with Berenson but not keep him close, as she relied on him to secure her greatest art purchases.

Jack Gardner was a loving and supportive husband

Jack showcased Isabella’s moves, supported her ambitions—and forgave her after one notable affair of the heart. Jack’s parents, typically Bostonian in most ways, were fiercely loyal to her as well, which bolstered her nerve. They were married for 38 years.

Isabella was friends with Henry James

Isabella’s friendship with Henry James textured one his novels – elusive and complicated; but the friends understood each other. James compared her to a shining jewel in a magnificent setting and finding in her character inspiration for his fiction.

Isabella was a spiritual woman

Isabella turned to the spiritual as a means of healing. Later in life she paid attention to social causes, particularly those helping women, children, and others in need— she gave substantial funds, for example, towards the building of an African American Episcopal church on Beacon Hill.

. . . . . . . . . .

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Courtyard Boston, MA

. . . . . . . . . .

The museum was performance art for IsabellaIt acted as a kind of “Isabellaland,” as a memoir using objects instead of words. She juxtaposed the life and movement of the dancer in Sargent’s El Jaleo with grief and memory at the other side of the Spanish Gallery, in the small chapel, a memorial to her only child who died before the age of two.

Radically, she placed Titian’s great Europa above a framed section of satin taken from one of her own Charles Fredrick Worth-designed gowns. She also filled the Raphael Room with objects that show or fill a woman’s life: paintings depicting—her collections most frequent motif—Madonna and Child; cassoni filled with luxurious fabrics; fine old Italian furniture arranged as if for a parry.

Isabella was a “late bloomer”

Isabella’s later decades are often skimmed over, despite having compelling and moving accomplishments as she aged. Isabella opened her museum in 1903, as she was about to turn sixty-three. She became more expansive and curious as she got older.

She found family-like relationships with artists and writers, designers and activists. Her relationship with in her sixties with Okakura Kakuzō, Japanese art expert living in Boston for a time, was especially intense and remarkable.

. . . . . . . . . .

Chasing Beauty is available on Bookshop.org*, Amazon*,

and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . . .

Natalie Dykstra is the author of Clover Adams: A Gilded and Heartbreaking Life. Her work on Isabella Stewart Gardner has won a Public Scholars Award from the National Endowment for the Humanities and an inaugural Robert and Ina Caro Research/Travel Fellowship sponsored by the Biographers International Organization (BIO). Dykstra, emerita professor of English at Hope College in Michigan, lives with her husband in Waltham, MA.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop.org and Amazon affiliate links. If a product is purchased after linking through, Literary Ladies receives a modest commission, which helps us to keep growing.

The post 10 Fascinating Facts About Isabella Stewart Gardner appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Trouble in Mind by Alice Childress – Playwright, Novelist & Activist

Alice Childress’s first full-length play, Trouble in Mind, premiered in 1955 at an interracial theater co-sponsored by a Presbyterian church and a synagogue in Greenwich Village.

According to accounts at the time, the audience “applauded and shouted bravos, and would not leave their seats until the author was brought on stage.” Despite initial audience enthusiasm, decades would pass before the play received the recognition it has today as a classic of American theater.

The show received an Obie Award for best original off-Broadway play that season and was slated to open on Broadway in 1957, but Childress herself pulled the plug on that production.

Childress said she spent two years rewriting the play, especially the ending, to satisfy the would-be producers with a “heart-warming little story.” But in the end, Childress found she could not write a version that pleased her backers and that also met her own demands.

A Portrayal of White-Dominated Theater

Childress’s struggles with Trouble mirror the play itself. Set backstage, it presents the behind-the-scenes banter and rehearsals of the cast and crew as they prepare to perform a play called Chaos in Belleville, meant to be an anti-lynching play.

Childress was very familiar with the challenges for Black actors. She was a co-founder of the American Negro Theatre and performed and directed with that company for a decade. She also worked in white-controlled venues, including on Broadway and for radio and television.

Often told she was “too light” for Black roles and “too Black” for other roles, she began writing herself because she wanted to create a wider range of opportunities for Black performers. She also felt some satisfaction in taking up a pen, noting that African Americans were the only racial group ever barred from literacy in the United States.

Enter Wiletta, Our Hero

The central figure in Trouble is Wiletta, a middle-aged Black woman who has a starring role for the first time in her long career. Previously, she has played “character parts,” or stereotypes—“mammy” roles, mothers talking their sons out of demanding equality, wives of men who keep them “laughin’ all the time” despite their refusal to work or come home at night.

“You ever hear of a lazy, no-good, two-timin’ man keepin’ a woman laughin’ all the time?” Wiletta asks Al Manners, the white director of the play.

Manners sees himself as a liberal. He believes he should be congratulated for being willing to work with Black performers on a show that is critical of lynching, though the play was written by a white man who distorts the attitudes of those involved. Manners tries to elicit a stronger performance from Wiletta, claiming he wants “truth.”

“Truth,” he explains, “is simply whatever you can bring yourself to believe.”

Yet Wiletta finds herself unable to inhabit her role as a mother who urges her adult son, who has committed the “crime” of voting, to turn himself in to the authorities who promise to keep him safe from a lynch mob by putting him in jail. She knows what the outcome will be. “I don’t see why the boy couldn’t get away… something’s wrong,” she objects.

Manners dismisses her concerns, telling her that they don’t “want to antagonize the audience.” “It’ll make ‘em mad if he gets away?” Wiletta asks.

Manners asks Sheldon, an elderly Black actor who is desperate for work as he faces housing insecurity, whether he finds the script offensive. Sheldon assures Manners that the script is fine, but then he goes on to describe a lynching he witnessed as a child in Virginia. Manners responds that such accounts make him feel “wretched, so guilty.”

Wiletta seizes the opportunity to suggest changes in the script. Rather than passively urging her son to turn himself in, she wants to say, “Run for it!” pointing out that she would rather he died while seeking his freedom rather than walking to his own destruction.

Manners rejects her suggestions. Her objections become more heated, and the rest of the cast—both Black and white—begin to fear for their own jobs.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Broadway and RevivalsTrouble in Mind ends with no clue as to whether “Chaos in Belleville” will go forward or not. We do know that nearly twenty-five years would pass before Trouble in Mind had another significant production, this time by the New Federal Theatre Project in 1979.

Further productions followed, but at a slow pace. There was a London premier in 1992, and then New York’s Negro Ensemble Company mounted a production in 1998.

While the play contains references to events of the 1950s—the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Little Rock school desegregation riots—it has only been in the 21st century that its importance has been recognized by the mainstream theatrical world. Yale Repertory Theater produced it in 2007 and 2019; the Arena Stage produced it in Washington, D.C. in 2011.

After a 2010 production in San Francisco, there were numerous productions in Chicago, Seattle, Ontario, North Carolina, and New Jersey. The play’s long-delayed Broadway premiere in was in 2021.

That production was nominated for four Tonys, including Best Revival, Best Actress (LaChanze as Wiletta), Best Featured Actor (Chuck Cooper as Sheldon), and Best Costume Design. Since then, there have been further opportunities to see this work, including in London, Chicago, Winnipeg, Hartford, and Boston.

. . . . . . . . . .

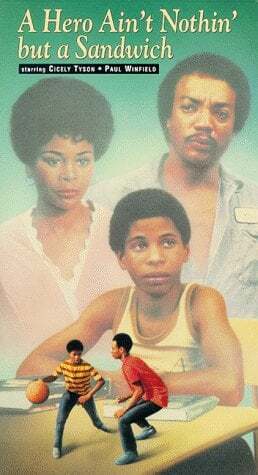

A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ But a Sandwich

is one of Alice Childress’s best-known works

. . . . . . . . . .

The version of Trouble in Mind generally mounted today offers an ending that is far from happy—yet not without hope.

According to Judith E. Barlow, in her introduction to Plays by American Women, 1930–1960, Childress’s ending implies “a bond among all oppressed peoples,” as Wiletta finds a sympathetic, though relatively powerless, ally in Henry, the elderly and overlooked Irish doorman, after everyone else in the cast and crew has abandoned her.

Present-day renditions of Trouble in Mind are hailed for their timeliness. Yet, according to Katy Perkins, who knew Childress well and edited an anthology of her plays, Childress “hated the saying ‘ahead of your time.’ Her thing was that people aren’t ahead of their time; they’re just choked during their time, they’re not allowed to do what they should be doing.”

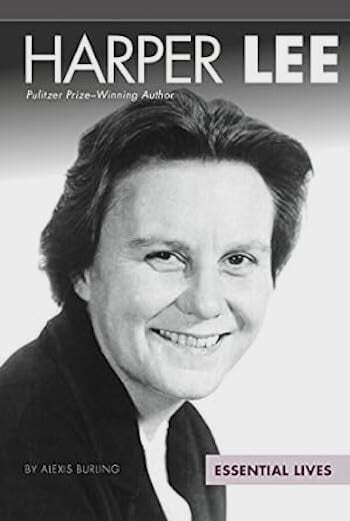

Ahead of her time or not, Childress, who lived into the late 20th century (1916–1994), went on to write numerous plays and novels, most famously, A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ but a Sandwich (1973). She did not live long enough to see this renewed interest in her theatrical work, but one suspects it wouldn’t have mattered to her.

Like her character Wiletta, Childress looked into herself to find her truth. And then she said what she wanted to say when she wanted to say it. That it has taken the rest of the world decades to listen was not her concern. Time has vindicated the realism of her play and the truth of her message.

Sources:

Barlow, Judith E. Plays by American Women 1930-1960. Applause Theatre Books, 2001Green, Jesse. “Review: ‘ Trouble in Mind,’ 66 Years Late and Still On Time ,” The New York Times, 18 Nov. 2021Phillips, Maya. “ Alice Childress Finally Gets to Make ‘Trouble’ on Broadway ,” The New York Times, 3 Nov. 2021Rule, Sheila. “ Alice Childress, 77, a Novelist; Drew Themes From Black Life ,” The New York Times, 19 Aug. 1994Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.

You may also enjoy: 8 Black Women Playwrights of the Early 20th Century

The post Trouble in Mind by Alice Childress – Playwright, Novelist & Activist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 12, 2024

The Friendship of Edna St. Vincent Millay and Elinor Wylie

When one thinks of Jazz Age literature, novels by F. Scott Fitzgerald or D. H. Lawrence might come to mind. Lyrical and provocative poetry was also part of Roaring Twenties culture. Two of the most beloved, and provocative, poets during the 1920s were Edna St. Vincent Millay and Elinor Wylie.

Both Millay and Wylie were dedicated lyrists and writers, despite their tempestuous personal lives. They both navigated the pitfalls of fame, scandal, and illness – all while leaving an indelible mark on American poetry.

Elinor WylieThe poet and novelist Elinor Wylie was born in Somerville, New Jersey on September 7, 1885. She was born into an affluent family marred by personal tragedy. Her parents’ marriage was deeply unhappy, and two of Elinor’s siblings committed suicide, with a third sibling attempting it.

Elinor’s father was a high-profile lawyer who became Solicitor General of the United States in 1897. Elinor grew up in Washington, D.C. from the age of twelve.

Elinor’s godfather was a Shakespeare scholar named Henry Howard Furness. Unusually for the time, he insisted that his goddaughter have the best education possible, including European governesses.

A beloved Irish maid instilled a love of folk tales in Elinor, and a teacher at her private school introduced her to the poetry of William Blake, John Donne, and Percy Bysshe Shelley; the latter would remain her greatest inspiration and favorite poet.

When Elinor showed an inclination towards being a “blue-stocking” (a common pejorative for an intellectual or career-minded woman) her parents were horrified. Elinor was supposed to be a debutante and have a dazzling society marriage.

In 1905, Elinor married an aspiring poet named Phillip Hichborn, but soon after the marriage he began falling into rages and displaying signs of mental illness. Sadly, he committed suicide in 1916. Many years later his and Elinor’s only child—also named Phillip, also a hopeful poet, and also possibly suffering from mental illness—met the same end as an adult.

A prominent, and married, Washington lawyer named Horace Wylie pursued Elinor. The two ran away in 1910, leaving behind their spouses and children. The two were condemned by society, and knowingly or not, Elinor had followed in Shelley’s footsteps. For the rest of her life her literary achievements were rarely noted without also mentioning this scandal.

. . . . . . . . . .

Elinor Wylie

. . . . . . . . . .

The poet and playwright Edna St. Vincent Millay was born in Rockland, Maine on February 22, 1892. Her parents separated when she was young, and her father gave little financial support to the three children he left behind.

Millay’s mother, Cora, was a strong-willed woman and supported her daughters by her work as a traveling nurse and occasional wigmaker. “The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver” was one of the poems that contributed to Millay’s eventual Pulitzer Prize, and it is a moving tribute to her sacrificial mother. It was one of the favorite poems of singer Johnny Cash, and he recited it from memory on his television show in 1970.

Cora frequently had to take work away from home, leaving her three daughters alone for days at a time in their seaside home in Camden, Maine. Due to their mother’s absences, Millay and her younger sisters, Norma and Kathleen, were extremely close knit. All three were musically gifted, with great charm, intense inner lives, and varying shades of red hair.

Despite being a voracious reader and a precocious writer, Millay’s first ambition was to be a concert pianist. She was eventually told that her hands were too small, she then shifted her focus to writing poetry, both as a means to support her family and as a way to make a mark on the world.

She wrote: “Life is brown and tepid for many of us. I want to write so that those who read me will say… ‘Life can be exciting and free and intense.’”

In 1912, at the young age of twenty and hitherto very isolated, Millay was able to write the long poem “Renascence” with its lines of startling boldness, maturity, and emotional depth:

Mine was the weight

Of every brooded wrong, the hate

That stood behind each envious thrust,

Mine every greed, mine every lust.

The poem was entered into a national competition to be included in an upcoming anthology, the Lyric Year. Although she did not win first prize, the poem skyrocketed Millay into the literati of the period. With the help of a patron, she attended the prestigious Vassar College. While there, Millay studied classical poetry, racked up broken hearts among her younger classmates, and nearly got expelled just before graduation. Afterwards, she headed for New York City.

. . . . . . . . . .

Edna St. Vincent Millay in her college days

. . . . . . . . . .

Elinor married Horace Wylie in 1916 after he obtained a divorce from his wife. Due to her lover’s encouragement, Wylie anonymously published her first book of poetry in England in 1912, Incidental Numbers. After the outbreak of World War I in Europe, the disgraced couple returned to the United States, frequently moving due to social ostracism.

Wylie’s poetry began to be published in multiple magazines, and early admirers of her poetry were novelists Bram Stoker, the author of Dracula, and the young Ernest Hemingway. She befriended writers John Peale Bishop and Edmund Wilson, who were also devoted friends of Millay. She also met the widowed poet William Rose Benét.

Both Benet and his brother Stephen Vincent would later win Pulitzer Prizes for poetry, William in 1942 and Stephen in 1944. William took it upon himself to advance Wylie’s literary career, and the two fell in love, which led to the end of Wylie’s second marriage.

Wylie’s brother Morton Hoyt married and divorced Eugenia Bankhead, the sister of the controversial actress Tallulah, a total of three times. When Bankhead once asked Wylie if she had had many lovers, the latter icily replied that “she was conservative about love and had simply married when she had experienced it.”

Wylie struggled to be taken seriously as a poet, which was made even more difficult by her unconventional past. She possessed great determination and once responded to her critics with, “I have a typewriter and a better brain them all of them, and they won’t succeed. I’ll beat them all yet!”

In 1921, Nets to Catch the Wind was published, Wylie’s first volume of poetry printed in the United States. The writer Babbette Deutsch called Nets “almost one uninterrupted cry to escape.” It is generally considered to contain many of her greatest poems, particularly “The Eagle and the Mole” and “A Proud Lady.”

“The Eagle and the Mole” is one of Wylie’s most beloved and anthologized poems, and vividly describes conformity (“The huddled warmth of crowds / Begets and fosters hate”) while offering a balm for the nonconformist’s inevitable rejection by their peers:

Avoid the reeking herd,

Shun the polluted flock,

Live like that stoic bird,

The eagle of the rock.

Similarly, in “A Proud Lady” she describes the “hate in the world’s hand,” a scornful hate she was well acquainted with, and a hate she defied with her poems:

But you have a proud face

Which the world cannot harm,

You have turned the pain to a grace

And the scorn to a charm.

You have taken the arrows and slings

Which prick and bruise

And fashioned them into wings

For the heels of your shoes.

Millay—who by now had weathered stormy relationships with both men and women and was likewise committed to pursuing her art at any cost—undoubtedly found much in Wylie’s verses that resonated with her struggle for artistic freedom.

In her poem “Weeds” she described the hateful outside world as “The baying of a pack athirst.” She enthusiastically reviewed Nets to Catch the Wind in the Literary Review.

“The book is an important one,” Millay wrote, “important in itself as it contains some excellent and distinguished work and…because it is the first book of its author, and thus marks the opening of yet another door by which beauty may enter the world.”

Millay’s biographer Daniel Mark Epstein writes that Millay’s glowing review “launched Wylie’s career in the 1920s as a love poet second only to Millay herself, who proved memorably generous to spirits with whom she felt artistic kinship such as Wylie.”

A Few Figs from Thistles, Millay’s second collection of poetry published in 1920, contained some of Millay’s most enduring poems, including “Recuerdo,” “I think I should have loved you presently,” and “First Fig,” which encapsulated the devil-may-care attitude that the flappers and “New Women” of the 1920s personified:

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—

It gives a lovely light!

In four lines, Millay took a sledgehammer to the last remnants of Victorianism and became one of the most quoted poets of her generation. It was inevitable that Millay and Wylie, two lovers of beauty (and flagrant rule-breakers) would eventually become friends as they swam against the current of public opinion.

The Friendship of Millay and WileyIn 1922 the literary critic and writer Edmund Wilson introduced Wylie to Millay, who was a former girlfriend he was still pining for. Epstein writes that “From the day Millay met Wylie, the two women were devoted to each other, corresponded, and visited each other’s homes.”

Unfortunately, there appear to be no color photographs of Wylie and Millay, and no photographs of the two women together. They would have made a striking pair: Millay, petite, freckled and gamine with red-gold hair and Wylie, tall, aloof, and regal with dark auburn hair. Both were known for their tousled bobs and preference for simply cut gowns in rich fabrics.

Both poets briefly wrote for the popular magazine Vanity Fair, and both published their first poetry collections after leaving the place of their births. Millay publishing Renascence and Other Poems after moving to the bohemian Greenwich Village, and Wylie publishing Incidental Numbers after her shocking elopement to England.

Along with having heartbreak, rejection, and red hair in common, the two writers shared similar themes and techniques in their poetry oeuvre. Both belonged to the lyric genre of poetry, which was known for its focus on nature and loyal adherence to the more traditional forms of poetry such as elegies, odes, and sonnets.

They were not always in agreement with each other. Millay strongly disapproved of Wylie’s imitation of the Irish poet William Butler Yeats in her poem “Madman’s Song.” Both writers, despite this the two had much in common, such as their social backgrounds.

Poetry was their preferred medium, but they also wrote in other genres to support themselves. While living in Greenwich Village, Millay also acted in the Provincetown Players (which included writers Djuna Barnes and Susan Glaspell) and wrote several plays, including the very successful Met Opera libretto The King’s Henchman.

Wylie wrote four novels, including The Venetian Glass Nephew, set in Renaissance Italy, and The Glass Angel, in which she decided to give her beloved Shelley a different fate than his untimely death (the novel is undoubtedly a very poetic work of fan fiction).

Wylie adored Shelley so much that she purchased several of his personal effects with her royalties from The Orphan Angel, and Benét wrote that his wife was “spontaneous and baffled [like Shelley] by the matter-of-factness of the world.” After Wylie’s death Millay wrote in a poem dedicated to her friend: “I think that…Shelley died with you–) / He live[s] on paper now, another way.”

In 1923 Wylie saw the publication of both her novel Jennifer Lorn and her poetry collection, Black Armour. 1923 was also a big year for Millay: she married the wealthy, handsome, and supportive Dutch merchant Eugen Boissevain.

After the wedding (donning a stunning green dress with mosquito netting for an impromptu veil) Millay promptly entered the hospital for appendicitis surgery. Soon afterwards she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for poetry, becoming the first woman recipient of the newly established honor.

In 1927, the League of American Penwomen asked Wylie to be a guest of honor at an author’s breakfast in Washington, D.C. They later canceled their invitation due to Wylie’s personal history, and an incensed Millay wrote them a letter, sending a copy of it to Wylie.

Millay was invited to the same event and wrote to the League of her decision to decline: “It is not in the power of an organizations which has insulted Elinor Wylie to honor me…I too am eligible for your disesteem. Strike me too from your lists, and permit me, I beg you, to share with Elinor Wylie a brilliant exile from your fusty province.”

In her diary, Millay raged against the insult to her friend, writing “I wished I had been a Fifth Avenue street sparrow yesterday—or in other words:

I wish to God I might have shat

On Mrs. Grundy’s Easter hat.

“Mrs. Grundy” was a popular term at the time for a priggish, prudish person—similar to today’s usage of the name “Karen” to describe a middle-class woman who polices behavior. Millay, with her own colorful past, despised women who judged or undermined other women.

In gratitude for Millay’s solidarity, Wylie responded: “My darling—A thousand thanks for your brilliant and noble defense…I have written you a ballad—to you—which perhaps you’ll like. Hope so, at least.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“To Hold Secure the Province of Pure Art”:Shared Poetry Subjects

In her writing, Millay aspired “To hold secure the province of pure art” and to craft “the deeply loved, the labored polished line,” and these were undoubtedly Wylie’s aspirations as well. They pursued the writing of poetry with unwavering commitment, and refused to associate with those who did not take their work seriously. It also appears that, commendably, they were not jealous of each other’s achievements.

Wylie was an aesthetic writer, which critics frequently and disparaging commented on, and she labored to craft indelible images with her verse. Delicate objects d’art was a frequent motif in her poetry, and lavishly described colors and textures.

Millay crafted haunting descriptions of nature as well but appeared more dedicated to crafting a poem that resonated with musicality, perhaps fitting for a failed concert pianist. The few recordings available of Millay reading her poetry bring out the musical nature of her verses, and with her deep voice her poems sound like songs.

Holly Peppe, a former president of the Millay Society, wrote that “Whether her subject was nature, love, loss, spiritual rebirth, personal freedom, women’s sexuality, or the state of the world, Millay was always conscious of how musicality in poetry would help deliver its message.”

Both Wylie and Millay gravitated to poems with short lines and stanzas, and both frequently wrote about the beauties of nature and about love affairs that were less than satisfactory, but these were not the only poetry subjects that they shared.

Fully aware that their own singular looks and allure would fade Wylie and Millay had ambivalent views about beauty, which they both painted as possessing human characteristics.

Wylie wrote of beauty in the eponymous poem:

O, she is neither good nor bad,

But innocent and wild!

Enshrine her and she dies, who had

The hard heart of a child.

In her poem “Assault” Millay writes of beauty:

I am waylaid by Beauty. Who will walk

Between me and the crying of the frogs?

Oh, savage Beauty, suffer me to pass,

That am a timid woman, on her way

From one house to another!

Both meditated on the inevitability of death with quiet reflection; both appear to have regarded it as natural a fact as sleep.

When I am dead, or sleeping

Without any pain

My soul will stop creeping

Through my jewelled brain. (Wylie’s poem “Song”)

And here a while, where no wind brings

The baying of a pack athirst,

May sleep the sleep of blessèd things,

The blood too bright, the brow accurst. (Millay’s poem “Weeds”)

However, Millay also memorably protested against death in one of her most emotionally charged poems “Dirge Without Music”:

Down, down, down into the darkness of the grave

Gently they go, the beautiful, the tender, the kind;

Quietly they go, the intelligent, the witty, the brave.

I know. But I do not approve. And I am not resigned.

Although it appears Wylie and Millay did not refer to themselves as flappers, both were unabashedly avant-garde, and both wrote honestly about women and their experiences in a beautiful and dangerous world.

As if singing in a duet, Millay wrote in her poem “I, being born a woman and distressed / By all the needs and notions of my kind” and Wylie echoed the thought, “I am, being woman, hard beset;/ I live by squeezing from a stone / What little nourishment I get.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“The Blood too Bright, the Brow Accurst”:Death Comes for the Poets

Both Wylie’s and Millay’s poetry was wildly popular among the public, which may have been a reason that critics frequently took aim at their women-centric verse. Another reason for criticism was likely due to their uncompromising unconventionality.

Neither Wylie or Millay believed in compromising their hunger for passion, or with subduing their ambition to be great poets. Both women were identical in their belief that love was worth pursuing, no matter what convention and society decreed, no matter the personal cost.

Had I concealed my love

And you so loved me longer,

Since all the wise reprove

Confession of that hunger

In any human creature,

It had not been my nature. (Wylie, “Love Song”)

It well may be that in a difficult hour,

Pinned down by pain and moaning for release,

Or nagged by want past resolution’s power,

I might be driven to sell your love for peace,

Or trade the memory of this night for food.

It well may be. I do not think I would. (Millay, Sonnet XXX)

Even some of Wylie’s poet contemporaries, including Sara Teasdale, could not or would not separate Wylie’s tangled personal life from her polished writing. Despite her own unconventional personal life, the poet Amy Lowell threatened Wylie shortly before marrying Benét. “But if you marry again, [I] shall cut you dead‐and I warn you all Society will do the same. You will be nobody.”

There was a notable double standard. Wylie’s career was damaged, while her near contemporary Ernest Hemingway who, despite a catastrophic personal life, is still regarded as an extraordinary writer and soundly admired for his iconoclasm.

After marrying Benét, he and Wylie frequently visited Steepletop, the home of Millay and the devoted Boissevain. The lovely country abode in upstate New York, which is currently not open to visitors, was named after the pink steeplebush wildflower that bloomed on the property.

The two women read poetry in front of a fire, intensely discussing the poems “St. Agnes Eve” and “Epipsychidion.” Wylie read Shelley’s poem the “West Wind” aloud and cried out to her friend, “The best poem ever written!”

The next day Wylie read her own novel Mortal Image (perhaps with a critical eye, hoping for reassurance from a fellow writer) while Millay played “first Chopin, then Bach, then Beethoven on the piano. I play so badly. But not too badly, I think, to be not allowed to play them. It was fun, Elinor there reading, & listening too.”

The uplifting literary friendship would soon end. Millay once wrote to her mother, “You see, I am a poet, and not quite right in my head, darling.” She was increasingly troubled by “extravagant depression” and a plethora of health problems. Likewise, Wylie suffered from extremely high blood pressure all her life, which caused crippling migraines, and eventually her death.

On December 16th, 1928, Wylie, who had just finished proofreading her last volume of poems, Angels and Earthly Creatures, asked aloud “Is that all it is?” and suddenly died of a stroke.

The day after, Millay was casually told of her friend’s passing right before she was to give a poetry reading. “Stunned, shaken, Millay made her way to the podium and, waving aside the fanfare and applause, began reciting Wylie’s verses, poem after poem, from memory.”

Millay’s next book was dedicated to her friend:

When I think of you,

I die too.

In my throat, bereft

Like yours, of air,

No sound is left,

Nothing is there

To make a word of grief.

Wylie was “so gay and splendid about tragic things, so comically serious about silly ones,” wrote Millay, “Oh, she was lovely! there was nobody like her at all.” Millay attended Wylie’s funeral, and the latter was buried in her favorite silver gown by Poiret.

Judith Farr, the poet and Emily Dickinson scholar wrote that, “the career of Elinor Wylie is remarkable for what might be called intensity of performance.” Her poetry likely influenced Millay’s collection Fatal Interview, a collection of sonnets that was published three years after Wylie’s death and was dedicated to her. Fatal Interview relates the history of a tragic love affair just as in Wylie’s “one person” sonnet sequence in Angels and Earthly Creatures.

Oh, she was beautiful in every part!

The auburn hair that bound the subtle brain;

The lovely mouth cut clear by wit and pain,

Uttering oaths and nonsense, uttering art…

The soaring mind outstripped the tethered heart.

After sustaining a severe back injury in a car accident in 1936, Millay became addicted to morphine, as well as alcohol. However, she did successfully break her addiction and resumed writing.

Her husband died in 1949 after, like Wylie, suffering from a stroke following lung surgery. Millay spent the next year preparing a new volume of poetry but passed away in 1950 after suffering a heart attack. Mine the Harvest was published posthumously four years later.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The Legacy of Two Red-Headed RebelsThe verse of Millay and Wylie was largely separate from the Modernist movement, which included the poets T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. This earned criticism from both contemporary and subsequent literary critics, who frequently accused Millay and Wylie’s poetry as being too old-fashioned or “sentimental.”

In retrospect, their poetry has aged better than some by the lionized Modernist poets Eliot and Pound, who were both notoriously anti-Semitic and often chauvinist. Much of Millay’s poetry written during the 1940s fervently condemned fascism and championed democracy, and she often recited her verses on the radio during World War II.

Millay and Wylie were dedicated to portraying the varied experiences of women in a man’s world, and many of their poems, both lyrical and grimly realistic, are still relevant today.

In 1931, three years after Wylie’s death, Millay wrote about women’s’ struggle in pursuing careers in the arts, words that her friend would likely have agreed with:

“What you produce, what you create must stand on its own feed regardless of your sex. We are supposed to have won all the battles for our rights to be individuals, but in the arts women are still put in a class by themselves, and I resent it, as I have always rebelled against discriminations or limitations of a woman’s experience on account of her sex.”

Further Reading and Sources

Poetry Foundation – Edna St. Vincent Millay Steepletop Museum What Lips My Lips Have Kissed: The Loves and Love Poems of Edna St. Vincent Millayby Daniel Mark EpsteinSavage Beauty by Nancy MilfordThe Life and Art of Elinor Wylie by Judith FarrA Private Madness: The Genius of Elinor Wylie by Evelyn HivelyElinor Wylie: A Life Apart by Stanley Olson Poetry Foundation – Elinor Wiley

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Katharine Armbrester, who graduated from the MFA creative writing program at the Mississippi University for Women in 2022. She is a devotee of Flannery O’Connor and Margaret Atwood, and loves periodicals, history, and writing.

The post The Friendship of Edna St. Vincent Millay and Elinor Wylie appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 5, 2024

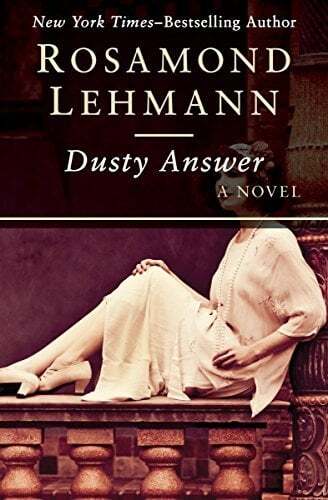

Rosamond Lehmann, Author of Dusty Answer

Rosamond Lehmann (February 3, 1901 – March 12, 1990) was an English novelist known for her sensitive portrayal of the emotional fabric of women’s lives and was part of the famous Bloomsbury Group in 1920s London.

Her first novel, Dusty Answer, caused a scandal for its subtle portrayal of lesbian characters, and is still her best-known work. Her novels as well as some of her non-fiction have been reissued by Virago and are now back in print.

Early Life

Rosamond Nina Lehmann was born in Bourne End, Buckinghamshire, the second of four children. Her father, Rudolph, was the editor of Punch magazine and became a Liberal MP in 1906. Her mother, Alice Davis, was originally from Boston, MA.

Rosamond had three siblings, John, Helen, and Beatrix. John would later become a writer and editor himself, working with Leonard Woolf at the Hogarth Press. Beatrix would become a well-known writer and actress.

Her childhood was spent in an idyllic setting, in a large Edwardian-style house on the banks of the Thames. She and her siblings were largely raised by nannies and governesses, only “coming down after tea” to see their parents.

Later, Rosamond would say that she always had the sense that she wanted to write. Remembering her first poem, written while sitting in a walnut tree and eating toffee she said, “I wrote all about fairies, and moonbeams, and nature, and it all poured out in rhymes.”

Her mother, who Rosamond remembered as “very puritanical and upright” (and who she once drew swiping at the air with a tennis racquet shouting in a speech bubble, “I HATE everybody”) was not encouraging of her efforts, saying to a friend that “Rosie writes doggerel.” Her father, however, was much more encouraging.

First (Hasty) Marriage

In 1919 Rosamond achieved a place at Girton College, Cambridge, to read English, and graduated with an honors degree.

She met her first husband Leslie Runciman, later Lord Runciman, the Methodist head of a ship-owning family in 1924. They married the same year, but the relationship was not a success. Rosamond was obliged to move to Newcastle to be with her husband, which she hated. She would later call this her “bleak period of exile in the detested North of England.”

Leslie was determined not to have children and pressured Rosamond into an illegal abortion in London. She later wrote about this experience in her 1936 novel The Weather in the Streets. The two separated and divorced in 1927.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Dusty Answer: Scandal and SuccessDuring this disastrous marriage, however, Rosamond wrote her first novel Dusty Answer about a young girl’s first experiences of love. The book explored what would become classic Lehmann themes of betrayal and romantic disappointment.

The novel had a slow start until it was hailed as “quite the most striking first novel of this generation” by the writer Alfred Noyes, and it became a bestseller.

Rosamond said that the subsequent reviews and publicity “made me feel as if I’d exposed myself nude on the platform of Albert Hall.”

Not all the attention was positive. Leonard Woolf’s National and Athenaeum accused Lehmann of the “clumsiness and lack of economy…[which] so often accompanies freshness and exuberance in the work of inexperienced novelists.” In addition, the coding of some characters as gay and lesbian was not subtle enough for some readers. One mother wrote, “Before consigning your book to the flames, [I] would wish to inform you of my disgust that anyone should pen such filth…”

As in all her later novels, Rosamond demonstrated an uncanny empathy for women’s experiences, so much so that she often received letters from women and teenage girls saying, “How did you know? This is my story.”

This empathy, however, would not always be well-received or understood by male critics. The Manchester Guardian’s reviewer complained of Rosamond’s 1953 novel The Echoing Grove that “so prolonged a voyage in an exclusively emotional and sexual sea afflicts a male reader at least with a sense of surfeit.”

The New Yorker’s reviewer went one step further, claiming that The Echoing Grove was fundamentally flawed because it attempted to blame women’s troubles on men, when the problem was actually “destiny.” The reviewer wrote, “Women, especially women writers have no use for destiny; they wouldn’t compose a Hamlet if they could.”

Second Marriage

In 1928 Rosamond married again, to Wogan Philipps, later Lord Milford, an aspiring artist and baron’s son. They had two children: a son, Hugo and a daughter, Sally.

With the success of Dusty Answer, Rosamond, and by extension Wogan too, found themselves at the heart of glamorous 1920s London. “Ros and Wog,” as the couple were known, mingled with Bloomsbury stalwarts such as Lytton Strachey, Vanessa and Clive Bell, and Leonard and Virginia Woolf. The couple lived an apparently charmed life at Ipsden House in Oxfordshire.

Virginia Woolf praised Rosamond’s work, and her “clear hard mind beating up now & again to poetry,” although Rosamond was never entirely sure how to respond to Virginia’s blend of teasing and flattery.

As Rosamond’s work became ever more successful, Wogan began a string of affairs, and later disappeared to the Spanish Civil War. Rosamond, meanwhile, began an affair with Goronwy Rees, whom she met at a visit to Elizabeth Bowen’s house in 1936, and only ended it when she read of his engagement in the newspaper. She divorced Wogan in 1944.

Professional Success and Personal Tumult

During the 1930s Rosamond wrote prolifically. Her second novel A Note in Music (1930), about two women trapped in loveless marriages in a northern town, was less warmly received than Dusty Answer but still sold well.

She then wrote Invitation to the Waltz (1932) and The Weather in the Streets (1936), both of which were bestsellers and featured the same main character, Olivia Curtis. The Ballad and The Source followed in 1945.

She also contributed a number of short stories to the magazine New Writing, edited and run by her brother John.

During World War II she lived in the country with her two children, and in 1941 began an intense relationship with the married poet Cecil Day-Lewis — so intense that he called it his “double marriage.” Although he never left his wife for her, he eventually left them both for the actress Jill Balcon in 1950.

Rosamond’s heartbreak and bitterness was echoed in her 1953 novel The Echoing Grove, about the reunion of two sisters after the death of a man who was husband to one and lover to the other. The drama of the split also spilled over to her friends and social acquaintances, all of whom were exhorted to take sides, intervene with Day Lewis on her behalf, or simply to sit and listen to her anger and upset.

Tragedy and SpiritualismIn 1958 Rosamond’s daughter Sally died at the age of twenty-four. Grief-stricken, Rosamond doubted whether she would ever write again.

She became interested — some said to the point of obsession — in spiritualism, believing that Sally was still alive and helping St. Francis of Assisi to teach unborn birds to sing. Her beliefs were derided by her friends. Laurie Lee called them “self deception on such a moving scale,” and many people blamed spiritualism for Rosamond’s retreat from social and public life and from fiction writing.

In 1967 The Swan in the Evening was published, a fragmented autobiography and spiritual insights, focused psychic experiences after Sally’s death. This was followed by A Sea-Grape Tree in 1977, in which she further explored psychic phenomena.

Rosamond later became vice-president of the Kensington College of Psychic Studies and the editor of their magazine Light.

Last Years and LegacyFor most of her later life Rosamond lived alone in a house in Kensington, London.She was known as a difficult and demanding woman who played “destructive emotional games,” but also as a courageous writer who was committed to her work at PEN International, which she joined in 1942. She was also made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1982.

Her books, which had fallen out of print, were republished by Penguin and Virago in the early 1980s. The BBC produced television dramatizations of Invitation to the Waltz and The Weather in the Streets, and a radio version of The Echoing Grove.

Rosamond was pleased with the renewed attention, calling it her “reincarnation.” However, she had problems with her eyesight and general health, and when she died at home on March 12, 1990, she was almost blind from cataracts.

Many of her books remain in print, and in 2002 The Echoing Grove was made into a film called Heart of Me, starring Helena Bonham Carter, Paul Bettany and Olivia Williams.

Dusty Answer, Invitation to the Waltz, The Ballad and the Source, The Weather in the Streets, The Echoing Grove, The Swan in the Evening, A Note in Music are all back in print, published by Virago.

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Rosamond LehmannMajor Works

Dusty Answer (1927)A Note in Music (1930)Invitation to the Waltz (1932)The Weather in the Streets (1936)No More Music (1939)The Ballad and the Source (1944)The Gypsy’s Baby & Other Stories (1946)The Echoing Grove (1953)The Swan in the Evening: Fragments of an Inner Life (1967; nonfiction)A Sea-Grape Tree (1976)Moments of Truth (1986; nonficition anthology)Biographies

Rosamond Lehmann by Diana E Lestourgeon (1965)Rosamond Lehmann by Judy Simons (1992)Rosamond Lehmann: A Life by Selina Hastings (2002)Rosamond Lehmann and Her Critics by Wendy Pollard (2004)Rosamond Lehmann: a Thirties Writer by Ruth Siegel (1990)More information

The Art of Fiction, No. 88 (The Paris Review) Doom and Bloomsbury (The Guardian) The Swan in the Evening (English Pen)The post Rosamond Lehmann, Author of Dusty Answer appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Precious Bane by Mary Webb, the 1926 novel

Precious Bane, the 1926 novel by English author Mary Webb, is a coming–of–age novel set in the English countryside. Our heroine, Prue Sarn, is a sharply observant young woman of Shropshire during the Napoleonic Era who has been born with a disfigured lip.

Her harelip leads the others in her superstitious village to treat her as an outsider due to the association it shares with witchcraft. Despite the hardships of rural life, her disfiguration and its resulting perceptions Prue endearingly finds beauty and compassion for all around her.

The colorful cast of Precious Bane includes Prue’s brother Gideon, whose temperament is the of polar opposite of hers. Gideon, the inheritor of the family farm, cannot see anything in his environment outside of its potential to be exploited for personal monetary gain.

In contrast Prue’s romantic interest Kester Woodseaves, a skilled weaver, shares a profound empathy for his world and sees this same beauty in.

English traditions and folklore fill out the world around Prue as her disfigurement encourages the suspicion of her community and ultimately the false accusation of murder and witchcraft to which Prue must defend. Ultimately Mary gifts her audience with a happy ending deserved by such a kind hearted and empathetic protagonist.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1929 review of Precious Bane by Mary WebbFrom an original review in The Hartford Courant, April 7, 1929. Mary Webb’s Precious Bane is a Charming Novel with Shropshire Background

Perhaps the first dominant thought of any sensitive reader as he lays down these two books after perusal, is that of rebellion and protest against the baffling cruelty of a fate which sends such a writer as Mary Webb to her untimely death and permits the continued existence of the myriad literary pigmies who supply their futile grist to the vast mill of contemporary fiction.

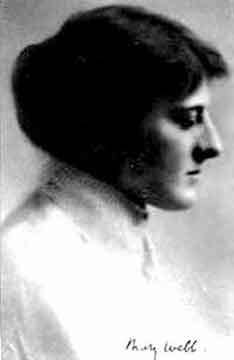

A portrait of Mrs. Webb faces the title page of Armour Wherein He Trusted. Like the fabled Lady of Shalott, who worked her spells so close to the scenes of Precious Bane Mary Webb had a lovely face – intellectual, thoughtful, and sweet. Not bearing any actual likeness to the face of Anne Douglas Sedgwick, but of the same type-sensitive, delicate, and fine.

Of mixed Welsh and Scottish ancestry, Mrs. Webb (Mary Meredith) spend the greater part of her life in her native Shropshire, at one time working with her husband as a market gardener, and with him selling their produce at their own stall in Shrewsbury market. In 1921, however, the Webbs came to London, making their home at Hamstead.

As all the reading worlds knows now, the grand vogue for Mrs. Webb’s novels was started when Mr. Stanley Baldwin, himself of Shropshire descent, became so impressed with Precious Bane that he wrote a warmly appreciative letter to its author. Precious Bane had, however, already won the Femina Vie Heureuse Prize for 1924-5, this prize being given annually, for “the best work of imagination in prose or verse descriptive of English life by and author who had not attained sufficient recognition.”

A Sweet CharacterLike Mrs. Webb’s other novels, Gone to Earth, Seven for a Secret, and the rest, Precious Bane is a tale of remote country life, and it is a story so beautiful in spirit, so exquisitely told, so instinct with a sort of spiritual exaltation, that the sense aches at it. There is a quality of high nobility in all of Mrs. Webb’s novels, uneven as they are in point of literary excellence, but her whole splendid gift crystalizes in Precious Bane which stands like a tall tower among its fellows.

Precious Bane is the story, related in the first person of a farmer’s daughter, Prudence Sarn, who was born with a disfigured lip, the result, so the neighbors believe, of a crossing of her mother’s path by a hare; the child is always looked at askance in the little community, and is even suspected of witchcraft.

Very skillfully and beautifully does Mrs. Webb contrive to convey, through Prudence’s own narrative, the impression of the girl’s lovely nature; of her innate loving kindness toward all creation, her loyalty, her sweet, sound, trustworthiness.

And, interwoven inextricably with the tale of Prue’s personal experience, are the threads of strange superstitions, folk lore, weather wisdom, homely philosophy, ingrained custom, stark brutalities, and the sounds, sights and scents of the farmstead and the woods and fields at all seasons of the revolving year.

Sympathetic Introduction

Mr. Baldwin has written a deeply sympathetic and a really penetrating introduction to Precious Bane, in which he truly notes that the strength of the book lies “in the fusion of the elements of a nature and man, observed in this remote countryside by a woman even more alive to the changing moods of nature than of man.”

And again, Mr. Baldwin writes – “Her sensibility is so acute and her power of words so sure and swift that one who reads some passages in Whitehall has almost the physical sense of being in Shropshire cornfields.”

There is something in Prue Sarn’s telling of her own story which will remind certain readers of Geoffrey Dennis’s splendid and unappreciated novel, of a poignant childhood. Mary Lee, a book which one hopes may someday come into its rightful heritage of fame; and there are country folk in Precious Bane who will inevitably suggest their Wessex prototypes – the uncanny figure of the local wizard, Beguildy, for example and many of the farm people.

The strange burial customs, the games, such as “The Game of the Costly Colors,” in playing which the village women indulge their love for gambling, the “Love Spinning,” reminiscent of the old-time New England quilting-bee, the hiring fair, with those waiting to be hired each carrying a sign of his trade.

The bull-baiting, the romance of the traveling weaver – all of these combine in a rich tapestry of sound and color, which sets us in the very core and center of remote rural Shropshire in the first quarter of the n ineteenth century.

The book fairly demands quotation, for every page is spangled with shrewd pithy sayings, descriptions of a breath-taking beauty, and quaint expressions which come to the reader with a sense of curious sub-conscious familiarity, seeming to link him with the past in which he shared.

There is the expressive work – “tuthree,” – “there’s a tuthree people know you, Prue,” says Kester Woodseaves the gallant weaver; and again, Prue writing of Beguildy’s house, notes that –“all was dimmery in the room.”

Precious Bane comes naturally and simply to a “happy ending,” for which one is glad; it is a book which arouses a sense of reverence, a book brimming with beauty, plain-spoken tender, a book for which to be devoutly grateful.

More about Precious Bane by Mary Webb

Precious Bane – a review Precious Bane full textPrecious Bane (1989) movieThe post Precious Bane by Mary Webb, the 1926 novel appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Precious Bane by Mary Webb (1926)

Precious Bane, the 1926 novel by English author Mary Webb, is a coming–of–age novel set in the English countryside. Our heroine, Prue Sarn, is a sharply observant young woman of Shropshire during the Napoleonic Era who has been born with a disfigured lip.

Her harelip leads the others in her superstitious village to treat her as an outsider due to the association it shares with witchcraft. Despite the hardships of rural life, her disfiguration and its resulting perceptions Prue endearingly finds beauty and compassion for all around her.

The colorful cast of Precious Bane includes Prue’s brother Gideon, whose temperament is the of polar opposite of hers. Gideon, the inheritor of the family farm, cannot see anything in his environment outside of its potential to be exploited for personal monetary gain.

In contrast Prue’s romantic interest Kester Woodseaves, a skilled weaver, shares a profound empathy for his world and sees this same beauty in.

English traditions and folklore fill out the world around Prue as her disfigurement encourages the suspicion of her community and ultimately the false accusation of murder and witchcraft to which Prue must defend. Ultimately Mary gifts her audience with a happy ending deserved by such a kind hearted and empathetic protagonist.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1929 review of Precious Bane by Mary WebbFrom an original review in The Hartford Courant, April 7, 1929. Mary Webb’s Precious Bane is a Charming Novel with Shropshire Background

Perhaps the first dominant thought of any sensitive reader as he lays down these two books after perusal, is that of rebellion and protest against the baffling cruelty of a fate which sends such a writer as Mary Webb to her untimely death and permits the continued existence of the myriad literary pigmies who supply their futile grist to the vast mill of contemporary fiction.

A portrait of Mrs. Webb faces the title page of Armour Wherein He Trusted. Like the fabled Lady of Shalott, who worked her spells so close to the scenes of Precious Bane Mary Webb had a lovely face – intellectual, thoughtful, and sweet. Not bearing any actual likeness to the face of Anne Douglas Sedgwick, but of the same type-sensitive, delicate, and fine.

Of mixed Welsh and Scottish ancestry, Mrs. Webb (Mary Meredith) spend the greater part of her life in her native Shropshire, at one time working with her husband as a market gardener, and with him selling their produce at their own stall in Shrewsbury market. In 1921, however, the Webbs came to London, making their home at Hamstead.

As all the reading worlds knows now, the grand vogue for Mrs. Webb’s novels was started when Mr. Stanley Baldwin, himself of Shropshire descent, became so impressed with Precious Bane that he wrote a warmly appreciative letter to its author. Precious Bane had, however, already won the Femina Vie Heureuse Prize for 1924-5, this prize being given annually, for “the best work of imagination in prose or verse descriptive of English life by and author who had not attained sufficient recognition.”

A Sweet CharacterLike Mrs. Webb’s other novels, Gone to Earth, Seven for a Secret, and the rest, Precious Bane is a tale of remote country life, and it is a story so beautiful in spirit, so exquisitely told, so instinct with a sort of spiritual exaltation, that the sense aches at it. There is a quality of high nobility in all of Mrs. Webb’s novels, uneven as they are in point of literary excellence, but her whole splendid gift crystalizes in Precious Bane which stands like a tall tower among its fellows.

Precious Bane is the story, related in the first person of a farmer’s daughter, Prudence Sarn, who was born with a disfigured lip, the result, so the neighbors believe, of a crossing of her mother’s path by a hare; the child is always looked at askance in the little community, and is even suspected of witchcraft.

Very skillfully and beautifully does Mrs. Webb contrive to convey, through Prudence’s own narrative, the impression of the girl’s lovely nature; of her innate loving kindness toward all creation, her loyalty, her sweet, sound, trustworthiness.

And, interwoven inextricably with the tale of Prue’s personal experience, are the threads of strange superstitions, folk lore, weather wisdom, homely philosophy, ingrained custom, stark brutalities, and the sounds, sights and scents of the farmstead and the woods and fields at all seasons of the revolving year.

Sympathetic Introduction

Mr. Baldwin has written a deeply sympathetic and a really penetrating introduction to Precious Bane, in which he truly notes that the strength of the book lies “in the fusion of the elements of a nature and man, observed in this remote countryside by a woman even more alive to the changing moods of nature than of man.”

And again, Mr. Baldwin writes – “Her sensibility is so acute and her power of words so sure and swift that one who reads some passages in Whitehall has almost the physical sense of being in Shropshire cornfields.”

There is something in Prue Sarn’s telling of her own story which will remind certain readers of Geoffrey Dennis’s splendid and unappreciated novel, of a poignant childhood. Mary Lee, a book which one hopes may someday come into its rightful heritage of fame; and there are country folk in Precious Bane who will inevitably suggest their Wessex prototypes – the uncanny figure of the local wizard, Beguildy, for example and many of the farm people.

The strange burial customs, the games, such as “The Game of the Costly Colors,” in playing which the village women indulge their love for gambling, the “Love Spinning,” reminiscent of the old-time New England quilting-bee, the hiring fair, with those waiting to be hired each carrying a sign of his trade.