Nava Atlas's Blog, page 10

June 3, 2024

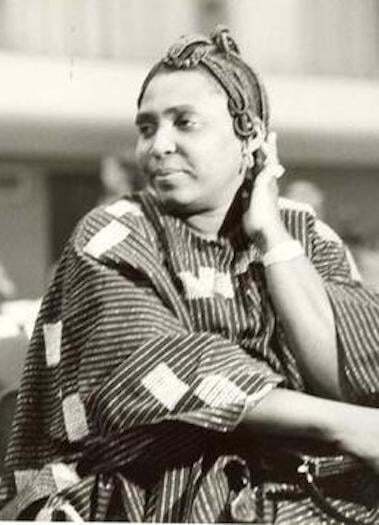

Mariama Bâ, Senegalese Feminist Author and Poet

Mariama Bâ (April 17, 1929 – August 17, 1981) was a Senegalese novelist, poet, teacher, and feminist. Her best-known works, So Long a Letter and Scarlet Song, both written from a woman’s perspective, explored themes of multiculturalism, polygamy, oppression, interpersonal relationships, and grief.

These two novels are among the most widely translated and studied African works of the twentieth century, according to Cambridge University Press.

Early life

Mariama Bâ was born in Dakar, Senegal to middle-class parents in 1929. Senegal was still controlled by colonial rules and laws. Her father was a civil servant, and later became the Minister of Health (1956). Her mother passed away when Mariama was still young.

Mariama was raised by her extended family, which included her father and grandparents. Her grandmother insisted that she assume a traditional household role; however, her father insisted that she attend school.

Mariama attended a girls’ boarding school, achieving the highest exam score for her area at age fourteen. She graduated from a teaching institution in 1947 and taught at École Normale de Rufisque until the school’s closure in the late fifties.

According to The Paris Review, Mariama first wanted to become a secretary. However, a teacher encouraged her to pursue teaching instead.

She was raised Muslim and studied the Quran extensively during her school holidays, something that is reflected throughout her works,

Mariama was married three times, which was considered unusual for a Muslim woman, and her experiences somewhat helped to shape her views on feminism and freedom.

Later, Mariama worked as a regional educational inspector, where her friends encouraged her writing. She was also part of several rights organizations, according to The Paris Review, which included Soroptimist International.

According to The Paris Review, Mariama critiqued traditional African-Islamic female roles. In an interview, she said:

“I had to know how to cook, do dishes, pound millet, make flour into couscous. I had to know how to wash clothes, iron ceremonial boubous [the colorful wide-sleeved robe worn by both sexes in West Africa], and when the right time came, with or without my consent, fall into another family — that of a husband.”

Two Novels by Mariama Bâ

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

So Long a Letter: Mariama Bâ published works of fiction that explored a woman’s traditional role, unique challenges, and interpersonal relationships. Her works have been translated into more than twenty languages from their original French, becoming part of worldwide curricula.

Her first work, Une si longue lettre, was translated into English as So Long a Letter in 1979. The work won the inaugural Noma Award (1980), a prize that has also gone to Marlene van Niekerk’s novel Triomf (1995) and Walter and Albertina Sisulu: In Our Lifetime (2003).

Mariama gave a speech at the 1980 Frankfurt Book Fair, approximately one year before her death, when she said: “In all cultures, the woman who makes demands or protests is devalued.”

Une si longue lettre is written as a series of letters from a woman to her best friend. Ramatoulaye writes to her childhood friend, a girl named Aissatou, who now lives in the United States.

The letters unpack Ramatoulaye’s relationship with her husband, and her changing journey after his death. Aissatou relays her own story, which also involved her relationship with her husband. Polygamy is one of the book’s strongest themes, explored through the characters’ different choices.

Many consider So Long a Letter semi-autobiographical; Mariama was married three times and had nine children. The novel also quotes from the Quran and identifies the narrator as Muslim, traits shared by the real-life author.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Scarlet Song: Un Chant écarlate (Scarlet Song) was Mariama’s second novel. It was published after her death in 1981, with an English translation appearing in 1986. Like Mariama’s prior novel, Scarlet Song explores interpersonal relationships from an African woman’s eyes.

The story introduces us to Mireille, whose father is a French diplomat: she marries Ousmane, who breaks off the relationship for Ouleymatou. In this story, the narrator struggles with her traditional values that clash against strict Christian, colonial morality.

Scarlet Song is believed to be more of a commentary and less autobiographical than Mariama’s first novel.

Other writings

Though Mariama was best known for the two novels above, she also wrote a widely translated essay, short story, and poem.

Her essay “The Political Functions of Written African Literatures, ” described the African author’s role as highly influential, having a position to speak up about injustice and misogyny.

The short story “Rejection” was published in several collections. It speaks out about abusive relationships and gender-based violence, using the story’s narrator.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Later discoveryRecent studies by UC Davis have unearthed a rare, previously undiscovered poem by Mariama Bâ. The poem is titled “Memories of Lagos” and was originally published in the newspaper L’Ouest Africain (The West African).

The newspaper’s editorial team was run by Mariama’s husband Obèye Diop, a politician, and the father of five children. He also served as the Senegalese Minister of Information.

LegacyMariama’s daughter published a 2007 biography of her mother’s life, entitled Mariama Bâ ou les allées d’un destin (The Alleys of a Destiny) by Mame Coumba Ndiaye.

She was named for the Senegalese water goddess Mame Coumba Bang, who is strongly connected to Saint-Louis area. Mame Coumba Bang is associated with powerful female figures, comparable to Maman Brigitte.

An eponymous boarding school in Gorée was also named after Mariama Bâ. A 10-minute documentary for Women in African History explores her life and influence, and it can be found here.

Further reading and sources

Mariama Bâ is considered one of the most influential female authors from Africa, and certainly one of the most widely translated Senegalese female authors. Here is more information, links, and further reading:

South African History Online Cambridge University Press The Paris Review – Feminize Your Canon: Mariama Bâ – The Paris Review Encylopedia.comContributed by Alex Coyne, a journalist, author, and proofreader. He has written for a variety of publications and websites, with a radar calibrated for gothic, gonzo and the weird. His features, posts, articles and interviews have been published in People Magazine, ATKV Taalgenoot, LitNet, The Citizen, Funds for Writers, and The South African, among other publications.

More by Alex Coyne on this site

Nadine Gordimer, South African Author and Activist 8 Essential Novels by South African Author Nadine Gordimer Jeanne Goosen, Author of We’re Not All Like That 6 Notable South African Women Poets The Banning of Nadine Gordimer’s Anti-Apartheid Novels Olive Schreiner, Author of The Story of a South African Farm 10 Unforgettable Books by South African Women Writers Ingrid Jonker, South African Poet and Anti-Apartheid ActivistThe post Mariama Bâ, Senegalese Feminist Author and Poet appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 2, 2024

4 Fascinating Museums that Were Founded by Women

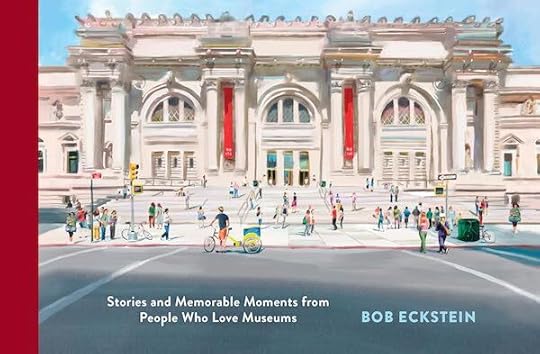

Bob Eckstein’s 2024 book, Footnotes from the Most Fascinating Museums: Stories and Memorable Moments from People Who Love Museums (Princeton Architectural Press) is a fantastic addition to the body of work by this talented writer, illustrator, and cartoonist.

A love letter to museums mainly around the U.S., it’s an eclectic collection that features Bob’s distinctive artwork. It was interesting to discover that several important museums were founded by women, and that’s what we’ll focus on here.

You’ll find plenty of art museums, of course, but other types of museums are well represented as well. Science, culture, transportation, history, and historic homes are represented. The entries offer basic info, but what really makes them shine are the personal stories from visitors to each venue.

In addition to those highlighted below, I hadn’t realized that the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in NYC was founded by three women collectively known as “the Ladies” — Abby Rockefeller, Lillie P. Bliss, and Mary Quinn Sullivan.

Footnotes from the Most Fascinating Museums is a book to treasure and dip into. I love it, and I think any art and culture aficionado will, too! Make sure to scroll down to read a Q & A with Bob.

Footnotes from the Most Fascinating Museums by Bob Eckstein

is available on Bookshop*, Amazon*, and wherever books are sold

From the publisher: We already know and love Bob Eckstein’s New York Times bestselling Footnotes from The World’s Greatest Bookstores. Now, Footnotes from the Most Fascinating Museums looks at the most beloved museums in North America. More than 75 museums are featured here (full list below) including those specializing in art, natural history, academia, science, and more.

Profiles from curators and museum workers appear alongside 155 original pieces of whimsical artwork that illustrate a story about the museum or showcase a particular work of art in its collection. This is a thought-provoking, inspiring reminder of why we go to museums and in the first place why we love them so much.

Artists, art lovers, students, travelers, and adventurers of all ages will delight in this highly giftable book. The following entries on the four museums are adapted from Footnotes from The World’s Greatest Bookstores, by permission of the author.

. . . . . . . . . .

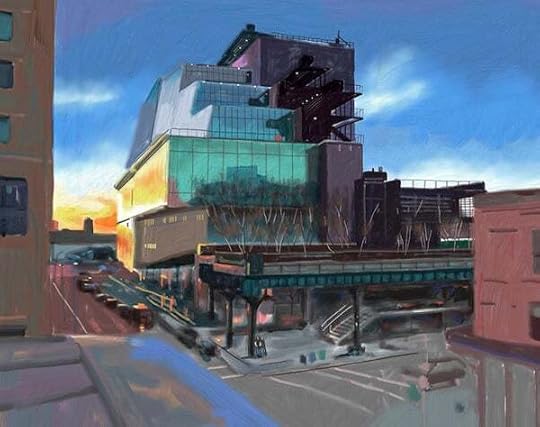

Whitney Museum of American ArtNew York City, Est. 1930

The Whitney, or officially the Whitney Museum of American Art, was founded by socialite Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney in 1930. The museum is most famous for its Whitney Biennial exhibition which showcase up-and-coming artists.

Its latest location is in the Meatpacking District in Manhattan. Its eight stories and two-hundred-thousand square feet consist of New York City’s largest column-free exhibit spaces. The museum includes an education center, library, theater, a conservation laboratory, and observation decks.

Their famed Independent Study Program, which boasts a list of accomplished artists, curators, and art historians as their alumni, is free and located in Roy Lichtenstein’s Greenwich Village studio. Michelle Obama attended the ceremonial ribbon-cutting of the new Renzo Piano–designed building in 2015 with Mayor Bill de Blasio.

. . . . . . . . . .

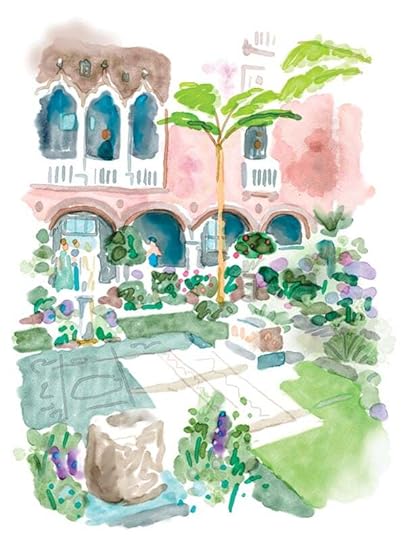

Isabella Stewart Gardner MuseumBoston, Massachusetts, Est. 1903

Built in 1901, Fenway Court was the former home of Isabella Stewart Gardner. Two years later it became the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, a must-see attraction in Boston filled with excellent examples of European, Asian, and American paintings, sculpture, tapestries, and decorative arts.

“We were a very young country and had very few opportunities of seeing beautiful things, works of art. I decided that the greatest need in our country was art. . . . So, I was determined to make it my life’s work if I could.”

The new wing of the museum, designed by Renzo Piano Building Workshop, opened in 2012 and will help preserve the original historic building by hosting all the museum’s public performances and events.

The museum highlight is a magnificent fifteenth-century Venetian palace courtyard. The courtyard has a glass roof that illuminates the museum’s galleries by diffusing the natural light. Gardner purchased eight Venetian stone balconies which overlook an exceptional Roman tile mosaic for the parameter of the center sanctuary.

. . . . . . . . . .

American Visionary Art MuseumBaltimore, Maryland, Est. 1995

Fifi, 2001, Theresa Segreti

One eight-year-old was brought by her grandparents. She loved AVAM so much she sat in our gallery floor and refused to move, declaring, ‘I am going to live here.’ They reasoned, ‘Where are you going to sleep?’ ‘What will you eat?’ She had plausible answers for all. The museum store had snacks, she could bathe in our sinks, and there’s a water fountain in the basement.” (—Rebecca Hoffberger, retired founder, director, and curator)

American Visionary Art Museum (AVAM) specializes in outsider art, also known as “intuitive art” or “raw art.” Baltimore granted the land to the museum under the condition it would remove the pollution from the copper paint factory and whiskey warehouse that was there previously. Congress has designated it America’s national museum for self-taught art.

The one-acre campus contains sixty-seven thousand square feet of exhibits, features three floors of space, the Tall Sculpture Barn, the Wildflower Garden, and the Jim Rouse Visionary Center. The museum uses guest curators for its shows and focuses on themed exhibitions with titles like Wind in Your Hair and High on Life.

The museum’s founder, Rebecca Alban Hoffberger, ran AVAM “pretty un-museumy” and, at the time of its 1995 opening, rejected academic scholarship and museum “tradition,” reportedly upsetting prominent members of the art world. But the museum has since won the support of collectors, critics, and the public.

. . . . . . . . . .

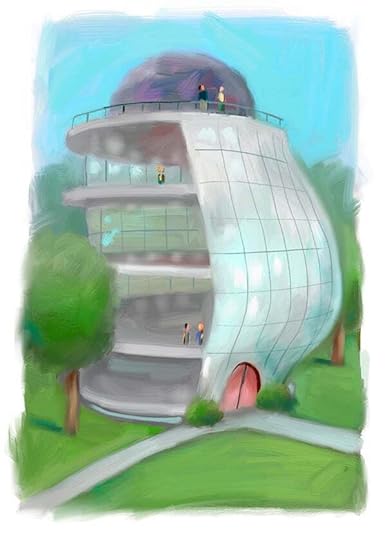

Museum of MotherhoodSt. Petersburg, Florida, Est. 2002

Museum of Motherhood is the first of its kind—a museum and educational center devoted to mothers, mothering, and motherhood in the world, covering the art, science, and history of mothers.

“By understanding the complex nature of family and women’s place in society, we become more compassionate and inspired in everything we do,” said Martha Joy Rose, the founder.

“I watched a couple of kids from the local high school try on the pregnancy vests and then waddle around groaning. Within five minutes they begged to take them off. One of the kids lamented how much they weighed. ‘Can you imagine doing that for nine months?’ the one asked. Is that how long they take to cook?’ the friend replied.”

The founder’s vision of the new building is that it will be in the shape of a womb with a front entrance symbolizing where motherhood all begins.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Bob Eckstein, a New York Times bestselling author. He has written for the New Yorker, New York Times, Reader’s Digest, Playboy, GQ, Wall St. Journal, and publications worldwide. He is also a Contributing Editor at Writer’s Digest and his newest book is Footnotes from the Most Fascinating Museums. Visit his website and connect with him on Substack.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop.org and Amazon affiliate links. If a product is purchased after linking through, Literary Ladies receives a modest commission, which helps us to keep growing.

The post 4 Fascinating Museums that Were Founded by Women appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 27, 2024

Harriet Martineau, Social Theorist and Novelist

Harriet Martineau (June 12, 1802 – June 27, 1876) was an English social theorist, lecturer and novelist. She was also an ardent supporter of women’s suffrage.

Her writings, which earned enough to support herself (very rare for a woman of her time) were proto-feminist and discusses aspects of culture pertaining to religion, politics, economics, and social institutions.

Harriet lost her senses of taste and smell from an early age and was partially deaf. Other health issues hindered her, yet she persevered in bringing her theories to a receptive audience.

The following biography was adapted From The Encyclopedia Britannica, 1911.

Early life

Harriet Martin was born in Norwich, England. where her father, Thomas Martineau, was a textile manufacturer. Her mother, Elizabeth, was the daughter of a sugar refiner. The family was of French Huguenot extraction and held Unitarian views.

The atmosphere of the home was industrious, intellectual, and austere. Harriet was clever, but sickly and unhappy. Her loss of taste and smell, and early deafness made her path to young adulthood challenging. She was, however, very well educated at home and developed early interests in political economy, philosophy, history, and the writings of Shakespeare.

At the age of fifteen, the state of her health and nerves led to a prolonged visit to her father’s sister, Mrs. Kentish, who kept a school in Bristol. Here, in the companionship of amiable and talented people, her life became happier.

She also improved under the influence of the Unitarian minister, Dr Lant Carpenter, from whose instructions, she says, she derived “an abominable spiritual rigidity and a truly respectable force of conscience strangely mingled together.”

In 1819, at age seventeen, she returned to Norwich. Around her twentieth year, her deafness was confirmed.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A need to earn her way and first writingsIn 1821, Harriet began to write anonymously for the Monthly Repository, a Unitarian periodical, and in 1823 she published Devotional Exercises and Addresses, Prayers and Hymns.

When Thomas Martineau died in 1826, he left scant inheritance to his wife and daughters. His death had been preceded by that of his eldest son (Harriet’s bother). Soon after, Harriet’s fiancé died as well.

Mrs. Martineau and her daughters after lost all their means of support by the failure of the bank where their money had been placed.

Harriet now had to earn her living. Unable to teach due to her deafness, she took up authorship in earnest. In addition to reviewing for the Repository, she wrote stories (afterwards collected as Traditions of Palestine), and in one year (1830) won three essay prizes from the Unitarian Association. She supplemented her income with needlework.

In 1831 she was sought a publisher for a series of tales designed as Illustrations of Political Economy. After many failures, she accepted less than ideal terms from Charles Fox, to whom she was introduced by his brother, the editor of the Repository.

The sale of the first of the series was hugely successful. The demand increased with each new edition; from that time her literary earnings were secured.

A move to London and a visit to America

She moved to London, where she made the acquaintance of many literary figures of the time including Hallam, Milman, Malthus, Monckton Milnes, Sydney Smith, Bulwer, and later, Carlyle.

She continued to be occupied with her political economy series and a supplemental series of Illustrations of Taxation. Four stories dealing with the poor law came out about the same time. These tales, direct, lucid, written without any appearance of effort, and yet practically effective, display the characteristics of her style.

In 1834, when the series was complete, Harriet paid a long visit to America. Here, her open support of the Abolitionist party, then small and very unpopular gave great offense, which was deepened by the publication, soon after her return, of Society in America (1837) and a Retrospect of Western Travel (1838).

An article in the Westminster Review, “The Martyr Age of the United States,” introduced English readers to the struggles of the Abolitionists.

The American books were followed by a novel, Deerbrook (1839), a story of middle-class country life. At the same time she produced a few little handbooks, forming parts of a Guide to Service.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A period of ill health and prolific writingsIn 1839, during a visit to the Continent, Harriet’s health broke down. She retired to solitary lodgings in Tynemouth, and remained an invalid for some years.

In that time of relative confinement, she wrote The Hour and the Man (1840), Life in the Sickroom (1844), and the Playfellow (1841). She also published a series of tales for children containing some of her most popular work: Settlers at Home, The Peasant and the Prince, and Feats on the Fiord.

During this period of illness she was offered a pension on the civil list but declined it, fearing to compromise her political independence. Her letter on the subject was published, and some of her friends raised a small annuity for her soon after.

In 1844 Miss Martineau underwent a course of mesmerism, and in a few months was restored to health. She eventually published an account of her case, which had caused much discussion, in sixteen Letters on Mesmerism.

After her recovery she removed to Ambleside, where she built herself “The Knoll,” the house in which she spent a great portion of her remaining years.

Mature writings in philosophical and social theory

In 1845 she published three volumes of Forest and Game Law Tales. In 1846 she made a tour with some friends in Egypt, Palestine and Syria, and on her return published Eastern Life, Present and Past (1848).

This work showed that as humanity passed through one after another of the world’s historic religions, the conception of the Deity and of Divine government became at each step more and more abstract and indefinite.

The ultimate goal Harriet believed in was philosophic atheism, but she didn’t expressly this belief openly. She published Household Education, expounding the theory that freedom and rationality, rather than command and obedience, are the most effectual instruments of education.

Her interest in schemes of instruction led her to start a series of lectures, addressed at first to the school children of Ambleside, but afterwards extended, by request, to their parents. The subjects were sanitary principles and practice, the histories of England and North America, and the scenes of her Eastern travels.

At the request of Charles Knight she wrote, in 1849, The History of the Thirty Years’ Peace, 1816–1846 — an excellent popular history written from the point of view of a “philosophical radical.”

In 1851 Harriet edited a volume of Letters on the Laws of Man’s Nature and Development. Its form is that of a correspondence between herself and H. G. Atkinson, and expanded the doctrine of philosophical atheism in which she had depicted the course of human belief in Eastern Life.

Atkinson was a zealous exponent of mesmerism. The prominence given to the topics of mesmerism and clairvoyance heightened the general disapproval of the book, which caused a lasting division between Harriet and some of her friends.

She published a condensed English version of the Philosophie Positive (1853). Her Letters from Ireland, written during a visit to that country in the summer of 1852, appeared in serial form. She was a contributor to the Westminster Review for many years and was one of the band of supporters whose financial assistance prevented its extinction or forced sale.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Final yearsIn the early part of 1855, Harriet found herself suffering from heart disease. She now began to write her autobiography, but her life, which she supposed to be so near its close, lasted for another twenty years.

Harriet cultivated a tiny farm at Ambleside with success, and her poorer neighbors owed much to her. Her busy life demonstrated two leading characteristics — industry and sincerity. The verdict she recorded on herself in the autobiographical sketch left to be published by the Daily News has been endorsed by posterity. She wrote, speaking of herself in the third person:

“Her original power was nothing more than was due to earnestness and intellectual clearness within a certain range. With small imaginative and suggestive powers, and therefore nothing approaching to genius, she could see clearly what she did see, and give a clear expression to what she had to say. In short, she could popularize while she could neither discover nor invent.”

Harriet Martineau died at The Knoll on June 27, 1876 at the age of 74.

. . . . . . . . . .

Further reading

Published works (an extensive bibliography) Harriet Martineau’s archive , University of Birmingham, England, at the Cadbury Research Center The Martineau Society , UKAutobiography, with Memorials by Maria Weston Chapman (1877) Public domain works on Project GutenbergThe post Harriet Martineau, Social Theorist and Novelist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 26, 2024

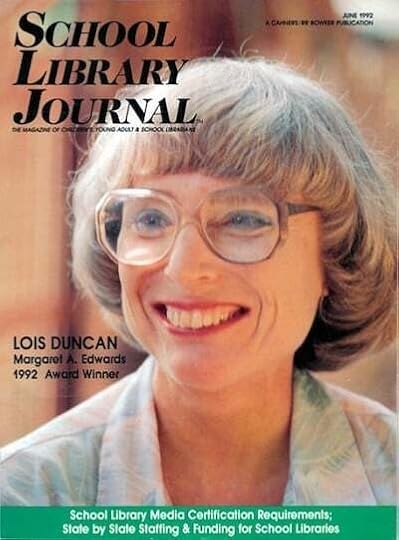

Lois Duncan, Author of I Know What You Did Last Summer

Lois Duncan (April 28, 1934 – June 15, 2016) published more than fifty books, beginning with romance novels for adults and ending with picture books for children—but her name is synonymous with the teen thrillers that have remained her best-known works.

Feature films based on her books, like Down a Dark Hall (2018) and I Know What You Did Last Summer (2021), have continued to sustain her readership.

Just as her thrillers took ordinary people and thrust them into dark places, her personal life was profoundly impacted by her teenage daughter’s murder. In 1992, Lois Duncan was back in the headlines some six years after her death, when charges were brought against the man who confessed to the 1989 murder of her youngest daughter.

Early life and the beginning of a writing career

Lois Duncan Steinmetz was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on April 28, 1934, where she lived with her mother, also named Lois, and her father, Joseph. Theirs was a “loving, gentle home” as she describes it in Chapters: My Growth as a Writer. (Quotations are from this memoir unless otherwise stated.)

After her brother Billy was born, the family resettled in Florida—a suitable location for her parents’ careers in photojournalism, where they worked for magazines like Life, Time, and Collier’s.

Lois loved spending time outdoors, playing in the woods or on the beaches, and although she enjoyed tormenting her brother, she enjoyed her own company too.

“I cannot remember a time when I did not consider myself a writer,” she said. By the time she was thirteen, she’d accumulated so many rejection slips that her mother forbade her from saving them. She wrote adventures and fairy tales: “What I couldn’t accomplish in real life, I could do on paper. All of my stories were written from a boy’s viewpoint.”

At her father’s urging, she showed a neighbor (who was a writer) a recent rejection from the Saturday Evening Post, and he advised her to write about what she knew instead. She began to transform her own experiences into fiction. The first story she wrote about an ordinary little girl, with braces on her teeth, earned her a twenty-five dollars. From then on, her own life informed her storytelling.

. . . . . . . . . .

Lois Duncan Steinmetz in her teens, photo by Joseph Steinmetz

courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . .

Quintessentially bookish, Lois was the high school yearbook editor and the managing editor of the newspaper (the best position available for a girl—only a boy could be the editor-in-chief).

She continued to value her solitude: “I ran with a crowd and enjoyed many people in a surface way, but I have seemed to form those deep all-consuming friendships that most teenage girls make such an important part of their lives.” Even then, she was dedicated to her work.

Lois’s parents supported her creativity. Her father was a Princeton and her mother had attended Smith as one of the first class of exchange students to graduate in Paris. So, there was no question that Lois would continue her studies.

“Education was a tradition in our family, and I moved automatically from high school into the college of my choice,” Duncan writes. That was Duke University, in 1952. Although she enjoyed her English and History classes, dorm life didn’t suit her; there was no opportunity for the solitude that propelled her writing, and she craved something more.

Handsome husband, cute house – what’s missing?

Lois married Joseph “Buzz” Cardozo, a pre-law student, just a few days after her nineteenth birthday in 1952 and shortly before his graduation. For the next two years she was an air force wife, until her husband was discharged and continued to law school.

Partly from loneliness and uncertainty. Lois began working on her first novel for the Seventeenth Summer Literary Contest. Married life wasn’t what she had expected. But after she won the contest, she could call herself an author — her romance Debutante Hill was published in 1958.

Lois wasn’t content. “I had a handsome husband, a cute little house to fuss around in, all the trappings that went with the role of an adult woman. Why did I feel so empty and dissatisfied? Something was missing, but what was it? I settled upon the same answer as millions of other young women. I had a baby.”

Independent and ambitious

Lois and Buzz were married for nine years before he met someone else. In an interview with Roger Sutton, she describes how unthinkable this was. “I’d never known a divorced person my whole life.” Not only did this disrupt her identity, but the six books she’d published by then weren’t enough to support three children.

Lois moved to New Mexico to be near her brother, along with her three children (Robin, Kerry, and Brett). She found administrative work in an advertising agency. Full-time work and caregiving sapped her energy and she set aside her writing. However, she began to submit photographs to contests, which paid off.

Soon she was able to arrange for childcare, which afforded her time to write. “I taught myself kinds of writing I had never before attempted. I wrote for women’s magazines, confession magazines, newspapers, and religious publications; I wrote verse and advertising copy.’

Lois developed a pattern of beginning a confession story on a Monday and submitting it on a Wednesday. Most were published and Duncan’s confidence—and income—grew.

. . . . . . . . . .

I Know What You Did Last Summer (1973)

remains one of Lois Duncan’s best-known works

. . . . . . . . . .

Lois met her second husband Don Arquette through her brother, and they married in 1965. He urged her to set aside the confession stories and consider submitting work to the top-tier women’s magazines, some of which had rejected her when she was starting out.

Once more, a return to stories based on her personal experiences brought her success. Good Housekeeping accepted her story about having won a photography contest. (Who could resist a story about winning a porpoise?)

Moving into another tier of journalism justified her return to novel writing. Back when Lois submitted her first novel for publication, an editor required that her nineteen-year-old narrator drink a Coca-Cola instead of a beer (anticipating pushback) but now, the YA genre was burgeoning. She studied the market and recognized the opportunity for innovation in realistic and challenging stories for teens.

Her original publisher was unconvinced that her move into suspense writing would suit her existing audience, but Ransom (1966), her story about schoolchildren kidnapped on a school bus, was a finalist for the Edgar Allan Poe Award. So was her next novel, about teen boys who go missing on a hiking trip, They Never Came Home.

Lois’s decision to change publishers demonstrates how fervently she believed in her stories, but she remained flexible when editors warned of a misstep.

With Down a Dark Hall (1974), for instance, she was warned that having male ghosts terrorizing female students at a boarding school would rankle readers in an era when women’s rights were gaining traction; instead, she transformed one of the artist-and-writer specters into Emily Brontë.

Inspiration and Endurance

In 1982, the Times Literary Supplement described Lois Duncan’s work as popular “not only with the soft underbelly of the literary world, the children’s book reviewers, but with its most hardened carapace, the teenage library book borrower.”

When asked about her decision to write for teens, Duncan joked that she had been one herself.

It’s a more revealing response than it seems, given the key role that Duncan’s personal experiences played in her fiction. In her freshman year at Duke, in 1952, the ESP study that her class participated in inspired A Gift of Magic (1971), anticipating the popularity of paranormal stories.

Some of her main characters were based on acquaintances and family members, including each of her five children: “The character of Mark in Killing Mr. Griffin is based on Robin’s horrible first boyfriend. Kit, in Down a Dark Hall, is Kerry, and the mischievous Brendon in A Gift of Magic is Brett. Young Don and Kate [the younger children from her second marriage] are Neal and Megan in Stranger with My Face.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Who Killed My Daughter? (1992)

. . . . . . . . . .

One of her most notable books, written for adults but embraced by younger readers, is the non-fiction volume about her youngest daughter’s murder, Who Killed My Daughter? (1992). It was continued in One to the Wolves (2013).

After her daughter’s murder, Lois began to move away from suspense writing. She returned to a series begun decades earlier with Hotel for Dogs; News for Dogs and Movies for Dogs are light and witty stories for younger readers, in which the main character is “a carbon copy [of herself]… not only a dog lover but an aspiring writer, already submitting stories to magazines at age ten” complete with a little brother like Billy (Andi’s brother, Bruce).

Hotel For Dogs and I Know What You Did Last Summer (about the teens in a vehicle that strikes a cyclist on the road, and who leave the scene of their crime) remain her bestselling novels. Her teen suspense novels were never out of print in her lifetime, and she was active in the process of readying ten of those novels for reissue in 2010.

Speaking about the updates with Valerie O. Patterson, Lois described taking out the polyester pantsuits, updating hairstyles, and adding electronics.

The phones were the most challenging aspect to change because many of the plots turned on characters being unable to call for help: “I dropped them into toilets and rivers, had their batteries run down, had them loaned to friends who didn’t return them.”

Though her stories are renowned for their compelling plot lines, Lois credited their endurance to the energy she invested in character development: styles change more than human nature.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Recognition and legacyIn 1971, Lois joined the journalism faculty at The University of New Mexico, where she taught for eleven years. At the same time, she took courses herself and in 1977 completed the degree she had begun many years before. Of course, she wrote about it: she submitted the story to Good Housekeeping and her payment covered the cost of her tuition.

Many of her books were recognized differently, having been banned in various schools and libraries. She speaks of Killing Mr. Griffin in particular (about students who kidnap their English teacher as a prank that goes wrong). She hypothesized that the title alone could have been problematic. Some challengers cited a violent scene from I Know What You Did Last Summer, which only appears in the film—not in the book.

As a young writer, Lois Duncan won Seventeen Magazine’s short story contest three times. Many of her novels were cited as ALA Best Books and claimed readers’ choices awards. She also received the 1992 Margaret Edwards Award from the American Library Association (for a body of young adult literature).

In 2015, she received the Lifetime Achievement (Grand Master) award from the Mystery Writers of America.

Lois died on June 15, 2016 at the age of 82. Her obituaries emphasized her focus on realistic characters struggling to resolve moral dilemmas and taking responsibility for their decisions. “Without being didactic,” The Guardian wrote, her characters “showed readers the necessity of facing up to the consequences of their actions.”

In Publishers’ Weekly, Beverly Horowitz wrote that “Lois Duncan’s thriller suspense novels led the charge for expanding the YA market, not only in terms of the honesty of her portrayals of teen characters, but also in terms of opening up YA.”

Lois Duncan was proud of her literary accomplishments, but her response to her youngest daughter’s murder took her in an entirely different direction. Through her work to uncover the facts of her daughter’s case, she connected with other families who navigated the complex system for seeking justice for lost loved ones. In tandem with her literary accomplishments, she contributed to the creation of a research center to investigate cold cases, which evolved into the non-profit Resource Center for Victims of Violent Deaths.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

Further reading

Lois Duncan’s bibliography works in multiple genres is vast;see her list of works in full here . Film and theatrical adaptations Remembering Lois Duncan, the Queen of Teen Suspense (NPR) Obituary in The Guardian

The post Lois Duncan, Author of I Know What You Did Last Summer appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 25, 2024

“Violets” – a short story by Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1875 – 1935) was a poet, short story writer, essayist, and journalist often associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Violets and Other Tales (1895), her first collection, combined poetry and prose in the same volume. “Violets,” the story that opens the book, is presented here in full.

Published when she was just twenty years old and going by her original name of Alice Ruth Moore, Violets and Other Tales includes short stories interspersed with the poems. This early work hints at feminism and social justice, predicting of the types of themes that would become her hallmark.

Her mixed heritage of Black, Creole, European, and Native American gave her a broad perspective on race. She explored racial issues in tandem with the varied and complex issues faced by women of color.

As her reputation grew she continued to explore sexism, racism, women’s work, and sexuality in the various genres in which she wrote. Alice Dunbar-Nelson would later become at least as well known for her short stories and searingly honest essays as for her poetry, if not more so. More of her short stories, which have come to be known as the Creole stories, have recently come to light.

. . . . . . . . . .

Early Poems from Violets and Other Tales

A Selection of Poems by Alice Dunbar-Nelson highlights some of her later poetry

. . . . . . . . . .

VIOLETS a short story by Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1895)

I.

“And she tied a bunch of violets with a tress of her pretty brown hair.”

She sat in the yellow glow of the lamplight softly humming these words. It was Easter evening, and the newly risen spring world was slowly sinking to a gentle, rosy, opalescent slumber, sweetly tired of the joy which had pervaded it all day.

For in the dawn of the perfect morn, it had arisen, stretched out its arms in glorious happiness to greet the Saviour and said its hallelujahs, merrily trilling out carols of bird, and organ and flower-song. But the evening had come, and rest.

There was a letter lying on the table, it read:

“Dear, I send you this little bunch of flowers as my Easter token. Perhaps you may not be able to read their meaning, so I’ll tell you. Violets, you know, are my favorite flowers. Dear, little, human-faced things! They seem always as if about to whisper a love-word; and then they signify that thought which passes always between you and me.

The orange blossoms—you know their meaning; the little pinks are the flowers you love; the evergreen leaf is the symbol of the endurance of our affection; the tube-roses I put in, because once when you kissed and pressed me close in your arms, I had a bunch of tube-roses on my bosom, and the heavy fragrance of their crushed loveliness has always lived in my memory.

The violets and pinks are from a bunch I wore to-day, and when kneeling at the altar, during communion, did I sin, dear, when I thought of you? The tube-roses and orange-blossoms I wore Friday night; you always wished for a lock of my hair, so I’ll tie these flowers with them—but there, it is not stable enough; let me wrap them with a bit of ribbon, pale blue, from that little dress I wore last winter to the dance, when we had such a long, sweet talk in that forgotten nook.

You always loved that dress, it fell in such soft ruffles away from the throat and bosom,—you called me your little forget-me-not, that night. I laid the flowers away for awhile in our favorite book,—Byron—just at the poem we loved best, and now I send them to you.

Keep them always in remembrance of me, and if aught should occur to separate us, press these flowers to your lips, and I will be with you in spirit, permeating your heart with unutterable love and happiness.”

II.

It is Easter again. As of old, the joyous bells clang out the glad news of the resurrection. The giddy, dancing sunbeams laugh riotously in field and street; birds carol their sweet twitterings everywhere, and the heavy perfume of flowers scents the golden atmosphere with inspiring fragrance. One long, golden sunbeam steals silently into the white-curtained window of a quiet room, and lay athwart a sleeping face.

Cold, pale, still, its fair, young face pressed against the satin-lined casket. Slender, white fingers, idle now, they that had never known rest; locked softly over a bunch of violets; violets and tube-roses in her soft, brown hair, violets in the bosom of her long, white gown; violets and tube-roses and orange-blossoms banked everywhere, until the air was filled with the ascending souls of the human flowers.

Some whispered that a broken heart had ceased to flutter in that still, young form, and that it was a mercy for the soul to ascend on the slender sunbeam. To-day she kneels at the throne of heaven, where one year ago she had communed at an earthly altar.

III.

Far away in a distant city, a man, carelessly looking among some papers, turned over a faded bunch of flowers tied with a blue ribbon and a lock of hair. He paused meditatively awhile, then turning to the regal-looking woman lounging before the fire, he asked:

“Wife, did you ever send me these?”

She raised her great, black eyes to his with a gesture of ineffable disdain, and replied languidly:

“You know very well I can’t bear flowers. How could I ever send such sentimental trash to any one? Throw them into the fire.”

And the Easter bells chimed a solemn requiem as the flames slowly licked up the faded violets. Was it merely fancy on the wife’s part, or did the husband really sigh,—a long, quivering breath of remembrance?

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Poetry Foundation

Modern American Poetry

Georgetown University: Classroom Issues and Struggles

Women Writers You Should Know

This Harlem Renaissance Writer Seemed to Live an Ordinary Life

Alice Ruth Moore Dunbar-Nelson on BlackPast

The post “Violets” – a short story by Alice Dunbar-Nelson appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 21, 2024

Literary Orphan Girls: Plucky Heroines Melting Hearts, Overcoming Adversity

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the plucky literary orphan girl became a favorite trope in children’s literature. Perhaps it’s because children were indeed commonly orphaned in those days, or that parents got in the way of exciting narratives.

Here are seven of the most enduring orphan girls in classic children’s literature: The eponymous Heidi (does she have a last name?), Rebecca Randall (Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm); Sara Crewe (A Little Princess); Anne Shirley (Anne of Green Gables); Pollyanna Whittier (Pollyanna); Mary Lennox (The Secret Garden); and Emily Byrd Starr (Emily of New Moon).

These girls are on the cusp of adolescence, a vulnerable stage in the best of circumstances. Orphaned and foisted on spinster aunts, unrelated caretakers, distant relatives, and indifferent schoolmistresses, these girls learn to navigate the world on their own terms.

A shout-out must goto Jane Eyre, who came along in the mid-1800s, and though we do suffer along with her in her orphaned childhood, much of the story concerns her young womanhood and quest for love and independence.

There’s also Judy of Daddy-Long-Legs, whose story takes place mainly during her college years, and in which we learn of her maturation with the support of a magnanimous, anonymous benefactor.

. . . . . . . . . .

Heidi (1881)

Johanna Spyri (1827 – 1901), the author of Heidi, has been called the “Swiss Louisa May Alcott.” Tens of millions of copies of this classic children’s novel (first published in 1881) have sold worldwide in translations of more than forty languages.

Heidi is a simple and rather sentimental tale of an orphan girl (of course) who is left by her aunt Dete, who has been caring for her, with her gruff grandfather, a veritable hermit living in the Swiss Alps with a few goats.

Heidi wins him over (of course) and grows to love him, the mountains, and the little goat herd Peter, her only friend. After a time, Dete comes back for Heidi, over Grandfather’s objections, having secured a place for her as a companion to the disabled young daughter of a wealthy businessman.

Heidi grows attached to the girl, and vice versa, but can’t shake her homesickness. She is returned to Grandfather, and, after some turmoil, all is well that ends well.

More about Heidi.

. . . . . . . . . .

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1903)

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm by Kate Douglas Wiggin, published in 1903, is a classic American tale of an orphan girl coming into her own and finding her way in a world that’s indifferent to her plight.

Rebecca Rowena Randall comes to live with her two aunts in the fictional village of Riverboro, Maine. Rebecca’s spirit tries the patience of the more stern of her aunts but ultimately uplifts and inspires them. She faces many challenges, but along the way, learns from all of them on the road to young adulthood.

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm was a great success from the start. It was adapted for the the theater starting in 1910, and was filmed several times. The best-known film adaptation starred Shirley Temple (1938), with a plot rather freely altered from that of the book.

More about Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Little Princess (1905)

A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett follows a young girl with a vivid imagination as she faces abandonment at a posh boarding school in London. The novel is an expansion of Burnett’s novella, Sara Crewe: or, What Happened at Miss Minchin’s Boarding School, first published in December 1887.

When Sara Crewe first arrived at the boarding school, she was indeed treated like a princess. She was given the prettiest room, her own pony, a maid to wait on her, and the fawning attention of the headmistress, Miss Minchin.

Then news arrives that changes Sara’s life entirely. She is now an orphan alone in the world. Now she was compelled to work in the school and live as a servant.

But Sarah remains her kind, courageous self. Abused by Miss Minchin and tormented by jealous students, she never wavers in her firm belief in her worth. Instead, Sarah supposes herself a real princess and uses her vivid imagination to make over in her mind her bleak surroundings and even bleaker life.

More about A Little Princess.

. . . . . . . . . .

Anne of Green Gables (1908)

Anne of Green Gables is a the first novel in a series by beloved Canadian author L. M. (Lucy Maud) Montgomery (1874 – 1942). Her first full-length book, it was a great success from the the time it was published, and has appealing to generations of readers of all ages and backgrounds sine.

Anne Shirley is a dreamy, imaginative 11-year-old orphan girl mistakenly sent to middle-aged brother and sister Matthew and Marilla Cuthbert, who meant to adopt a boy to help on their farm.

Set in Prince Edward Island, where the author grew up, the original volume and its sequels follow Anne from her arrival in the fictional town of Avonlea, through school, college, marriage, and motherhood.

More about Anne of Green Gables.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Secret Garden (1911)

The Secret Garden, another classic by Frances Hodgson Burnett was published in 1911 after an original version was first serialized in The American Magazine in 1910. The story follows the journey of Mary Lennox, a sickly and unloved ten-year-old girl born to wealthy British parents in India.

After a cholera epidemic kills her parents, Mary is sent to England to live with her Uncle Archibald in an isolated, mysterious house. The tale follows the spoiled and sulky young girl as she slowly sheds her sour demeanor after discovering a secret, locked garden on the grounds of her uncle’s manor.

Mary befriends Dickon, one of the servant’s brother, a free spirit who was able to communicate with animals, and Colin, her uncle’s son, a neglected invalid. The Secret Garden has remained a timeless classic for its themes of friendship and the power of nature to heal the body and spirit.

More about The Secret Garden.

. . . . . . . . . .

Pollyanna (1913)

The 1913 novel Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter (1868 – 1920) is perhaps less familiar now than the lasting expression that grew from its sentimental story. Most everyone knows what defines a “Pollyanna” — someone who looks at the bright side of things no matter how dire, or who paints an overly optimistic picture of any situation.

Pollyanna, subtitled “The Glad Book,” was incredibly successful from the start, and inspired many adaptations in other media. Though intended as a children’s novel, it appealed to all ages.

Eleven-year-old Pollyanna Whittier is sent to live with her aunt Polly, an icy spinster. Pollyanna and her departed father had devised a “glad game,” wherein they would try to find the silver lining in any situation, no matter how dire. So when Pollyanna got a pair of crutches for Christmas instead of the doll she longed for, she decided to be glad that she didn’t actually need the crutches. You get the picture!

More about Pollyanna.

. . . . . . . . . .

Emily of New Moon (1923)

Emily of New Moon by L.M. Montgomery is the start of a trilogy of novels about Emily Byrd Starr. It invites comparison with the Anne of Green Gables series by the same author. These books, as is true for many of L.M. Montgomery’s writings, are meant for “children of all ages.”

When Emily’s father dies of consumption (what is now called tuberculosis), she is orphaned. She is sent to live at New Moon Farm to live with her aunts, Elizabeth and Laura Murray (typical literary spinsters) and cousin Jimmy.

There she makes friends with Ilse, Perry, and Teddy, each of whom has a dream based on their particular gift. Emily wishes passionately to be a writer; Ilse wants to be a speaker, Perry seems destined to be a politician, and Teddy is a talented artist.

Emily has a conflict with her Aunt Elizabeth, who’s not on board with her desire to write. Each of her friends is having an issue with a parent. Emily finds an ally in an elderly schoolteacher, who encourages her writing while being a helpful and honest critic.

More about Emily of New Moon.

More about literary orphans

Why Do We Write About Literary Orphans so Much? 50+ Orphans in Literature 10 Orphans from LiteratureThe post Literary Orphan Girls: Plucky Heroines Melting Hearts, Overcoming Adversity appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 15, 2024

10 Novels by Vera Caspary, Prolific Writer of Fiction & Screenplays

Vera Caspary (1899– 1987) was a remarkably prolific American novelist, screenwriter, and playwright. Over the course of her long career, she became known as a writer of crime fiction and thrillers, though she created works in other genres as well. Widely praised in her lifetime, this roundup of ten Vera Caspary novels illuminates the work of a writer who has been unjustly forgotten.

Caspary had more than twenty novels published (plus others left unpublished), the best known of which remains Laura (1943). She also wrote long short stories and novellas, not to mention numerous screenplays for Hollywood films, some based on her own works.

Many Caspary works featured young, forward-thinking women (then called “career girls”) who fought for female autonomy and equality, and refused male protection. Though most of her work is out of print, many of her books can still be found. She’s an iconic writer whose work deserves rediscovery.

According to her autobiography, Vera considered herself lucky to have lived during the “century of the woman,” and to have been part of the struggle that led to greater equality. Her work paved the way for the strong female characters we celebrate in contemporary fiction, and her own life story serves as inspiration for women who strive for equality today.

. . . . . . . . . . .

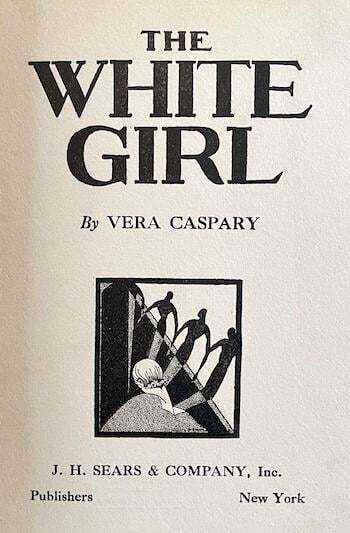

The White Girl (1929)

The White Girl came out in January 1929 to very enthusiastic reviews and had run into a sixth edition by March of the same year, the month in which Nella Larsen published Passing to much more tepid reviews and poor sales.

Passing belatedly staked an important place as a classic fictional work of race, class, sexuality, and identity. Thematically similar, and published the same year, The White Girl was published earlier that same year and is all but forgotten.

As Caspary wrote in her autobiography, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, “There was a rumor that I was a Black girl who had written an autobiography.” She wasn’t.

Despite the many strongly autobiographical elements in The White Girl, its heroine Solaria Cox isn’t Jewish like the author. Rather, she is transposed to a light-skinned young Black woman, her “camellia-toned skin” pale enough to allow her to pass as white, which she does, as did many young Black women in Chicago and New York, the settings for both The White Girl and Passing.

More about The White Girl.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Music in the Street (1929)

Music in the Street was one of three novels by Caspary released in 1929, the same year as The White Girl and Ladies and Gents. Mae Thorpe moves away from her small-town family into a working girls’ home in Chicago, where at first, she is one of the unpopular girls with no boyfriend who stays home on a Saturday night.

Mae finds a man, though he is by no means the kind of boy the popular girls would envy: Olyn is an artist, an intellectual, shy, socially awkward, and worst of all, poor and living at the YMCA.

But then someone far more romantic comes along – Boyd Wheeler, a salesman. He has been coming into the drugstore where Mae works on a regular basis and she has always liked him, but never had the courage to talk to him. Eventually one of her friends from Rolfe House introduces them. He takes her out – to a theatre and a restaurant rather than an art gallery. Boyd wastes no time, even though this is the first date.

More about Music in the Street.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Ladies and Gents (1929)

Soon after Anita Loos’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was released, and well before Caspary’s Ladies and Gents was published, the death of the flapper was being widely announced. An article in the New York Times of February 16, 1928, was titled “No More Flappers.”

But unlike Lorelei Lee, unlike Janet Oglethorpe, unlike F. Scott Fitzgerald’s flapper heroines Isabelle Borgé and Daisy Buchanan and indeed unlike Fitzgerald’s wife Zelda, whom he named “the first American flapper,” Rosina in Ladies and Gents does not come from money or from high society.

Rosina is somewhat similar to Magnolia from Edna Ferber’s Show Boat (1926), who “learned to strut and shuffle the buck-and-wing from the Negroes whose black faces dotted the boards of the southern wharves,” and her daughter Kim, who becomes a famous actress in New York City.

More about Ladies and Gents

. . . . . . . . .

Laura (1942)

Laura, a noir detective novel/murder mystery published in 1943, has remained Vera Caspary’s best-known work, partially thanks to the well-regarded film adaptation that followed. It is considered a film noir classic.

The slim yet action-packed story was first serialized in Collier’s magazine in 1942 as Ring Twice for Laura.

In the excellent afterword for the 2005 Feminist Press edition of this book, A.B. Emrys writes:

“Caspary’s fairy tale for working women takes place in a world of men who use women for advancement and self-reflection. The potential darkness of this world places Laura into the noir category and shadows even Caspary’s non-crime fiction … ‘Who can you trust’ was a game working women had to play frequently, and Laura makes evident that women might be labeled femmes fatales because they worked in the male-dominated business world.”

More about Laura.

. . . . . . . . .

Bedelia (1945)

“She seduces men … but does she kill them? A mystery about the wickedest woman who ever loved.” (from the front cover blurb from the 2012 paperback edition published in the Femmes Fatales series by the Feminist).

If you had bought any of the paperback editions with their unsubtle front cover blurbs giving the game away, by page one hundred you might be starting to feel disappointed — no one has yet died.

Earlier on though, Caspary would have teased you with the doctor’s suspicion that Charlie Horst’s recent illness may have been caused by poison – a poison that was perhaps given to him by his new wife Bedelia. But Charlie doesn’t believe it and we’re not sure either. Bedelia does seem like the perfect wife for Charlie, and they do seem to be in love. Or are they?

More about Bedelia.

. . . . . . . . .

The Gardenia (1952)

Even by her usual standards, Vera Caspary’s slim novel The Gardenia had a very quick route to the screen. Published in early 1952, producer Alex Gottlieb bought the film rights on September 3, 1952, and engaged Fritz Lang to direct (Caspary had no input into the script).

On the surface, this is a murder mystery and fits best in the psycho-thrillers section. But deep down it’s also an existential coming-of-age story, a female bildungsroman just as much as Jane Eyre, Agnes Grey, Fanny Burney’s Evelina, Maria Edgeworth’s Belinda, or Elizabeth Gaskell’s Ruth.

Unlike the typical Caspary woman, Agnes is not a highflying career success, but works with many other women in a telephone exchange as a long-distance operator. And unlike her predecessors, Agnes does not have her own apartment but shares a bungalow with a roommate, divorcee Crystal. Shy, modest Agnes does not stand out among these many women, nor does she want to; her closest precursor is Mae in Music in the Street.

More about The Gardenia .

. . . . . . . . .

Evvie (1960)

Evvie is a sophisticated thriller described here succinctly by its original publisher:

“This big, bursting novel of the roaring Twenties – and of two girls who believed that love and art could save the world, if not themselves – is in our view the best book that Vera Caspary has ever written, not forgetting Laura.”

Evvie Ashton and Louise Goodman shared a studio in Chicago in 1928, the age of “the girl.” Louise was a successful advertising copywriter in love with her boss. Evvie, married and divorced at seventeen, beautiful, artistic, was living on her “alimony.” Men found her irresistible – just as she found men. She painted, she danced, she read a great deal, and could discuss anything by repeating what her admirers had said.

But, in the midst of all the gaiety, Evvie and Louise found their lives becoming desperately complicated. Yet neither sensed that tragedy was to strike, until a horrible crime involving friends and families, strays and unknowns, the cream and the dregs of Chicago, gave the newspapers a field day.

The reader, mesmerized by the constantly mounting suspense, follows the involvements, the revelations and the shocking relationships of all those touched by the crime. But it is Evvie herself who will haunt the reader’s memory for a long, long time.”

More about Evvie.

. . . . . . . . .

Bachelor in Paradise (1961)

The newly built Los Angeles suburb of Paradise in Vera Caspary’s 1961 novel is rather like the aspirational estate of Northridge in Caspary’s earlier story “Stranger in the House” (1943).

“It is one of those suburbs distinguished in real-estate advertisements by the word exclusive. The residents spend large sums to separate themselves from neighbors whom they meet as often as possible at the Country Club . . . Pedestrians are seldom seen.”

With Caspary’s Laura, Bedelia, Evvie and Elizabeth X we had women at the center of a mystery pursued by multiple men, here we have a man who is himself a mystery pursued by multiple women: Dolores, Linda, Rosemary and her siren teenage daughter Patty. Divorces ensue, jealousy and envy are everywhere. One night, in his own house, Adam is assaulted by three separate jealous men.

More about Bachelor in Paradise.

. . . . . . . . .

The Man Who Loved Hs Wife (1966)

From the 1966 Dell books edition:

“This is a brilliantly thrilling novel about a sick man who keeps a secret diary in which he records all the suspicions and highly charged emotions he feels for his beautiful young wife. The story reaches its climax when the wife, refusing to lie, admits to one act of infidelity.

Her confession induces in her husband fresh ravages of distrust and mental agony. Shortly afterwards he is found dead of suffocation … With absolute mastery of her theme, and in an atmosphere of mounting suspense, Vera Caspary builds up to a surprise climax with all the enchantment and skill for which she is famous.”

More about The Man Who Loved His Wife.

. . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth X / The Secret of Elizabeth (1966)

Vera Caspary’s last published novel, Elizabeth X, was released first in the U.K. in 1978, the year before her autobiography, The Secrets of Grown-ups. It was reissued in the U.S. the following year as The Secret of Elizabeth.

We are in familiar Wilkie Collins territory, with multiple narrators telling the same story from different angles. As with Collins’ The Woman in White and Caspary’s own Stranger Than Truth, but unlike Laura and Final Portrait, the narrators are listed in the contents at the beginning of the book, so we know in advance what to expect.

In Elizabeth X, a couple is driving down a road through a forest near Westport, Connecticut late at night when the wife sees a young woman in white wandering unsteadily; she wants to stop the car to help the distressed woman, but the husband is suspicious, thinking it may be a trap.

More about Elizabeth X/The Secret of Elizabeth

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

The post 10 Novels by Vera Caspary, Prolific Writer of Fiction & Screenplays appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 10, 2024

“A Pair of Silk Stockings” – a 1897 short story by Kate Chopin

Presented here is the full text of “A Pair of Silk Stockings,” a short story by Kate Chopin published in 1897 in Vogue magazine. The story follows Mrs. Sommers, a young mother, who decided to spend an unexpected windfall of fifteen dollars on herself, rather than on her children.

Kate Chopin liked contributing to Vogue because she believed that the magazine was uncharacteristically “fearless and truthful” for in its depiction of women’s lives. in that era. This story has been reprinted in later collections of Kate Chopin’s short works.

The following supplementary material is adapted from Wikipedia, under their share-and-share alike license:

Plot summary

Mrs. Sommers comes into the small fortune of fifteen dollars. After a few days of reflection, she decides to use the money to purchase clothing for her children so they may look “fresh and dainty and new for once in their lives.”

That narrative suggests that Mrs. Sommers had been before her marriage a wealthy woman, but now “needs of the present absorbed her every faculty.”

An exhausted Mrs. Sommers rests at a counter where she will begin her shopping adventure. There she finds a pair of silk stockings for sale and is entranced by their smoothness. “Not thinking at all,” she disregards her plans to obtain clothes for her children and instead spends her money and her afternoon for herself.

She purchases boots to go with her stockings, buys fitted kid gloves, reads expensive magazines while lunching at a high-class restaurant, and ends her day sharing chocolates with a fellow theatre goer.

After the play ends, she boards the cable car to return home with “a poignant wish, a powerful longing that the cable car would never stop anywhere, but go on and on with her forever.”

Brief analysis of “A Pair of Silk Stockings”

Allen Stein (in Mississippi Quarterly, summer 2004) argues that serpentine silk stockings represent the empty consumerism that Mrs. Sommers uses to try to escape her life. Chopin critic and biographer Barbara Ewell (author of Kate Chopin, 1986) concurs, and calls the story “a small masterpiece.” She posits that “the power of money to enhance self-esteem and confidence is the core” of the narrative.”

Describing Mrs. Sommers as “little,” Chopin refers to more than her physical stature. The neighbors are all aware of what Mrs. Sommers’ social standing had been before her marriage, and see how her marriage has reduced her.

On the day of her shopping trip, Mrs. Sommers’ physical exhaustion also mirrors the weakening of her self resolve. Until she finds the stockings, Mrs. Sommers has been able to maintain her selflessness. But the temptation proves too much and she succumbs to the “mechanical impulse that directed her actions and freed her of responsibility” —words which prefigure Edna Pontellier in Chopin’s later novella The Awakening, which would be published two years later, in 1899.

Mrs. Sommers’ sojourn into a materialistic world brings her confidence, but her experience, just like the matinee she finds there, is ultimately transient. Mrs. Sommers’ brief moment of happiness, Ewell suggests, must end as it does for many of Chopin’s characters.

“A Pair of Silk Stockings” is in the public domain. Following is the original text in full. No changes have been made other than breaking up long paragraphs for better viewability.

. . . . . . . . . .

“A Pair of Silk Stockings” by Kate Chopin (full text)Little Mrs. Sommers one day found herself the unexpected possessor of fifteen dollars. It seemed to her a very large amount of money, and the way in which it stuffed and bulged her worn old porte-monnaie gave her a feeling of importance such as she had not enjoyed for years.

The question of investment was one that occupied her greatly. For a day or two she walked about apparently in a dreamy state, but really absorbed in speculation and calculation. She did not wish to act hastily, to do anything she might afterward regret. But it was during the still hours of the night when she lay awake revolving plans in her mind that she seemed to see her way clearly toward a proper and judicious use of the money.

A dollar or two should be added to the price usually paid for Janie’s shoes, which would insure their lasting an appreciable time longer than they usually did. She would buy so and so many yards of percale for new shirt waists for the boys and Janie and Mag. She had intended to make the old ones do by skillful patching. Mag should have another gown.

She had seen some beautiful patterns, veritable bargains in the shop windows. And still there would be left enough for new stockings — two pairs apiece — and what darning that would save for a while! She would get caps for the boys and sailor-hats for the girls. The vision of her little brood looking fresh and dainty and new for once in their lives excited her and made her restless and wakeful with anticipation.

The neighbors sometimes talked of certain “better days” that little Mrs. Sommers had known before she had ever thought of being Mrs. Sommers. She herself indulged in no such morbid retrospection. She had no time – no second of time to devote to the past. The needs of the present absorbed her every faculty. A vision of the future like some dim, gaunt monster sometimes appalled her, but luckily to-morrow never comes.

Mrs. Sommers was one who knew the value of bargains; who could stand for hours making her way inch by inch toward the desired object that was selling below cost. She could elbow her way if need be; she had learned to clutch a piece of goods and hold it and stick to it with persistence and determination till her turn came to be served, no matter when it came.

But that day she was a little faint and tired. She had swallowed a light luncheon – no! when she came to think of it, between getting the children fed and the place righted, and preparing herself for the shopping bout, she had actually forgotten to eat any luncheon at all!

She sat herself upon a revolving stool before a counter that was comparatively deserted, trying to gather strength and courage to charge through an eager multitude that was besieging breast-works of shirting and figured lawn. An all-gone limp feeling had come over her and she rested her hand aimlessly upon the counter.

She wore no gloves. By degrees she grew aware that her hand had encountered something very soothing, very pleasant to touch. She looked down to see that her hand lay upon a pile of silk stockings.

A placard near by announced that they had been reduced in price from two dollars and fifty cents to one dollar and ninety-eight cents; and a young girl who stood behind the counter asked her if she wished to examine their line of silk hosiery.

She smiled, just as if she had been asked to inspect a tiara of diamonds with the ultimate view of purchasing it. But she went on feeling the soft, sheeny luxurious things – with both hands now, holding them up to see them glisten, and to feel the glide serpent-like through her fingers.

Two hectic blotches came suddenly into her pale cheeks. She looked up at the girl. “Do you think there are any eights-and-a-half among these?”

There were any number of eights-and-a-half. In fact, there were more of that size than any other. Here was a light-blue pair; there were some lavender, some all black and various shades of tan and gray. Mrs. Sommers selected a black pair and looked at them very long and closely. She pretended to be examining their texture, which the clerk assured her was excellent.

“A dollar and ninety-eight cents,” she mused aloud. “Well, I’ll take this pair.” She handed the girl a five-dollar bill and waited for her change and for her parcel. What a very small parcel it was. It seemed lost in the depths of her shabby old shopping-bag.

Mrs. Sommers after that did not move in the direction of the bargain counter. She took the elevator, which carried her to an upper floor into the region of the ladies’ waiting-rooms. Here, in a retired corner, she exchanged her cotton stockings for the new silk ones which she had just bought.

She was not going through any acute mental process or reasoning with herself, nor was she striving to explain to her satisfaction the motive of her action. She was not thinking at all. She seemed for the time to be taking a rest from that laborious and fatiguing function and to have abandoned herself to some mechanical impulse that directed her actions and freed her of responsibility.

How good was the touch of the raw silk to her flesh! She felt like lying back in the cushioned chair and reveling for a while in the luxury of it. She did for a little while. Then she replaced her shoes, rolled the cotton stockings together and thrust them into her bag. After doing this she crossed straight over to the shoe department and took her seat to be fitted.

She was fastidious. The clerk could not make her out; he could not reconcile her shoes with her stockings, and she was not too easily pleased. She held back her skirts and turned her feet one way and her head another way as she glanced down at the polished, pointed-tipped boots.

Her foot and ankle looked very pretty. She could not realize that they belonged to her and were a part of herself. She wanted an excellent and stylish fit, she told the young fellow who served her, and she did not mind the difference of a dollar or two more in the price so long as she got what she desired.

It was a long time since Mrs. Sommers had been fitted with gloves. On rare occasions when she had bought a pair they were always “bargains,” so cheap that it would have been preposterous and unreasonable to have expected them to be fitted to the hand.

Now she rested her elbow on the cushion of the glove counter, and a pretty, pleasant young creature, delicate and deft of touch, drew a long-wristed “kid” over Mrs. Sommers’ hand. She smoothed it down over the wrist and buttoned it neatly, and both lost themselves for a second or two in admiring contemplation of the little symmetrical gloved hand. But there were other places where money might be spent.

There were books and magazines piled up in the window of a stall a few paces down the street. Mrs. Sommers bought two high-priced magazines such as she had been accustomed to read in the days when she had been accustomed to other pleasant things.

She carried them without wrapping. As well as she could she lifted her skirts at the crossings. Her stockings and boots and well-fitting gloves had worked marvels in her bearing – had given her a feeling of assurance, a sense of belonging to the well-dressed multitude.

She was very hungry. Another time she would have stifled the cravings for food until reaching her own home, where she would have brewed herself a cup of tea and taken a snack of anything that was available. But the impulse that was guiding her would not suffer her to entertain any such thought.

There was a restaurant at the corner. She had never entered its doors; from the outside she had sometimes caught glimpses of spotless damask and shining crystal, and soft-stepping waiters serving people of fashion.

When she entered her appearance created no surprise, no consternation, as she had half feared it might. She seated herself at a small table alone, and an attentive waiter at once approached to take her order. She did not want a profusion; she craved a nice and tasty bite — a half-dozen blue points, a plump chop with cress, a something sweet — crème-frappèe, for instance; a glass of Rhine wine, and after all a small cup of black coffee.

While waiting to be served she removed her gloves very leisurely and laid them beside her. Then she picked up a magazine and glanced through it, cutting the pages with a blunt edge of her knife. It was all very agreeable. The damask was even more spotless than it had seemed through the window, and the crystal more sparkling.

There were quiet ladies and gentlemen, who did not notice her, lunching at the small tables like her own. A soft, pleasing strain of music could be heard, and a gentle breeze was blowing through the window. She tasted a bite, and she read a word or two, and she sipped the amber wine and wiggled her toes in the silk stockings.

The price of it made no difference. She counted the money out to the waiter and left an extra coin on his tray, whereupon he bowed before her as before a princess of royal blood.

There was still money in her purse, and her next temptation presented itself in the shape of a matinée poster.

It was a little later when she entered the theatre, the play had begun and the house seemed to her to be packed. But there were vacant seats here and there, and into one of them she was ushered, between brilliantly dressed women who had gone there to kill time and eat candy and display their gaudy attire.

There were many others who were there solely for the play and acting. It is safe to say there was no one present who bore quite the attitude which Mrs. Sommers did to her surroundings. She gathered in the whole — stage and players and people in one wide impression, and absorbed it and enjoyed it.

She laughed at the comedy and wept — she and the gaudy woman next to her wept over the tragedy. And they talked a little together over it. And the gaudy woman wiped her eyes and sniffed on a tiny square of filmy, perfumed lace and passed little Mrs. Sommers her box of candy.

The play was over, the music ceased, the crowd filed out. It was like a dream ended. People scattered in all directions. Mrs. Sommers went to the corner and waited for the cable car.

A man with keen eyes, who sat opposite to her, seemed to like the study of her small, pale face. It puzzled him to decipher what he saw there. In truth he saw nothing — unless he were wizard enough to detect a poignant wish, a powerful longing that the cable car would never stop anywhere, but go on and on with her forever.

More about “A Pair of Silk Stockings” by Kate Chopin

Audio reading on Librivox More analysis on KateChopin.OrgMore full texts of Kate Chopin’s works on this site