Nava Atlas's Blog, page 7

December 3, 2024

From New Journalism to Modern Gonzo: Joan Didion, Gail Sheehy & Barbara Ehrenreich

Gonzo journalism is a writing style strongly associated with Tom Wolfe and Hunter S. Thompson. However, others have contributed their voice to immersive journalism since the genre’s earliest roots in New Journalism.

Here we’ll explore the work of Joan Didion, Gail Sheehy, and Barbara Ehrenreich in this context as three impactful female gonzo journalists.

Where the author becomes central to the story or investigation is an example of immersive or gonzo journalism.

A Brief Introduction to Immersive Journalism

The first use of the term “New Journalism” is credited to Matthew Arnold in 1887, and in more recent times, to Tom Wolfe. Gonzo journalism evolved from there, originating from a 1970s article about the Kentucky Derby published in Scanlan’s Monthly. Since then, immersive nonfiction is another broad, descriptive phrase for this particular journalistic style.

However, some sources have stated that the first use of the word “gonzo” was used by the Boston Globe editor to describe Thompson’s writing style. Collins Dictionary lists the meanings for gonzo as “wild or crazy” or alternatively as “explicitly indicating the writer’s feelings at the time of witnessing the events.”

The phrase “crazy” would also be used to describe any events surrounding the gonzo author or observer, with Thompson noting: “If you’re going to be crazy, you have to get paid for it or else you’re going to be locked up.”

Gonzo, immersive, or investigative journalism sometimes adds responsibility or risk to reporting a story. However, gonzo journalism is never written as deliberate recklessness on the author’s part—there’s always a sense of responsibility even if stories or topics might get “crazy”.

Once the journalist becomes central to their story, you have a possible contender for what might be immersive nonfiction or gonzo journalism. For example, it can be argued that one of its early pioneers was Nellie Bly (1864–1922) who had herself institutionalized so that she could write the now-famous exposé, Ten Days in a Madhouse.

Bly’s writing also took her on a trip around the world in 72 days— she took inspiration from Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days (1872) to see whether it was truly possible. Her real journey beat the fictional one by more than a week.

Modern gonzo journalism and immersive nonfiction have shown no signs of stopping or slowing down. The Gonzo Foundation promotes modern gonzo journalism by preserving Hunter S. Thompson’s legacy and writings.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Joan DidionJoan Didion (1934–2021) was one of gonzo journalism’s pioneers. Didion typed out Ernest Hemingway’s works as a writing exercise. This technique was echoed by Hunter S. Thompson, who did the same with F. Scott Fitzgerald’s writing.

She published her debut novel Run River in 1963, though focused much of her work on immersive nonfiction. Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968) is a seminal work that explores California life and the countercultural hippie movement.

Didion’s essay for The Saturday Evening Post in 1967 described the darker side of Haight-Ashbury counterculture—shooting meth and dropping acid, a sharp contrast to the Summer of Love that was being portrayed in the media.

The nonfiction work Salvador (1983) covered the Salvadorian civil war from first-hand perspective—truly immersive journalism. In 1992, she published another essay collection titled After Henry.

Her New York Times essay “Why I Write” explored Didion’s motivations: “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see, and what it means.”

Didion’s essay “In Bed” described her struggle with chronic migraines. She wrote: “Four, sometimes five times a month, I spend the day in bed with a migraine headache, insensible to the world around me.”

The Year of Magical Thinking chronicled the grieving process after her husband’s death. Written in 2004, it was published in 2005. Didion’s last book was an essay collection Let Me Tell You What I Mean (2021).

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Gail SheehyGail Sheehy (1936 – 2020) was a pivotal immersive nonfiction writer, journalist, and political essayist. She examined the dark side of city living, often intermingled with her first-person perspective. She wrote for some of creative nonfiction’s most familiar magazines and publications, including Vanity Fair and New York.

Sheehy began writing sales and advertising copy for retailer J.C. Penney. She later became known for serious, hard-hitting feature writing. Like many immersive nonfiction authors, Sheehy’s writing put controversial topics under the spotlight. Famously, Sheehy provided in-depth and never-before-seen coverage of the Kennedy family.

Gail Sheehy wrote a 1969 feature article called Speed City for New York Magazine. Eventually, the idea evolved into the longer work Speed is of the Essence (1971), a book highlighting the evils of drug addiction and methamphetamine.

Redpants and Sugarman later became an explorative 1971 feature article about city prostitution.

The song Sugar Man by Rodriguez (professional mononym of Sixto Diaz Rodriguez) was recorded in 1969—and released in 1970 from the album Cold Fact. The Tom Waits song Downtown Train also makes a passing reference to “redpants and the sugar man” in 1985.

Sheehy’s influence stretched beyond journalism and into popular culture. Her writing continued to follow immersive journalism and gonzo-related writing.

Sheehy joined the Women’s Institute for Freedom of the Press (WIFP) as an associate in 1977. Today, the list contains a worldwide list of female journalists and press staff, including Sena Christian, Kashini Maistry, and Dorothy Abbott.

She continued in her highly detailed political coverage, and some of her focused pieces about Hillary Clinton were collected in the book Hillary’s Choice (1999). Sheehy’s writing evolved as she aged, and her later essays more readily covered aging and grief. Later books included Sex and the Seasoned Woman (2006) and Passages Into Caregiving (2010).

Gail Sheehy’s final work was a memoir—Daring: My Passages: A Memoir (2014). She passed away in 2020 at the age of 83. In her New York Times obituary, Sheehy was described as a “journalist, author, and social observer.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Barbara EhrenreichBarbara Ehrenreich (1941 – 2022) was an influential news writer, journalist, and creative nonfiction author. She received her PhD in cellular immunology. However, she dedicated her life to social causes and commentary after giving birth to her daughter in a public healthcare clinic in 1970.

The Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) lauds Ehrenreich’s “pen and sarcastic wit,” which became part of her characteristic writing style. Ehrenreich focused much of her writing on social causes, including healthcare, economics, and women’s rights. She became familiar as a columnist whose work turned into more than twenty published books.

In 1978, Ehrenreich published one of her most famous titles: For Her Own Good. This work explored the treatment of women, illustrated with “150 years of expert advice” that put women at a disadvantage in healthcare and science.

Ehrenreich was also known for such nonfiction works as The American Health Empire (1971); Witches, Midwives, and Nurses (1972); and The Snarling Citizen (1995). The Worst Years of Our Lives (1990) collected more of Ehrenreich’s essays, focusing on the progression of female rights—and the lack thereof.

The 2001 nonfiction book Nickeled and Dimed continues the tradition of immersive journalism. In this case, Ehrenreich cast a spotlight on American income by living the actual experience of getting by on minimum-wage jobs, and then documenting the results.

The 2005 book Bait and Switch: The Futile Pursuit of the American Dream was another one of Ehrenreich’s immersive works. For this book, she assumed the role of a corporate employee climbing the company ladder—the description calling it “the shadowy world of the corporate unemployed.”

Bright-Sided (2009) explored the downsides of “positive thinking” and the psychological impact of being told to be happier in the face of financial or social issues. This was a deliberate commentary on “guru-like” thinking, published during the self-help boom.

Her writing focused often on topics like social or economic injustices, and took an insider’s perspective on these issues. Ehrenreich stands out as an important gonzo journalist, because she was never afraid to immerse herself in the story — Living with a Wild God (2014) explored her thoughts on religion as a nonbeliever.

Ehrenreich wrote features for numerous publications, including Vogue, Salon.com, Harper’s Magazine, and The New York Times. Her last book was a collection of essays called Had I Known, published in 2020. Barbara Ehrenreich, called a “myth-busting writer and activist” in an obituary, passed away in 2022.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Alex J. Coyne, a journalist, author, and proofreader. He has written for a variety of publications and websites, with a radar calibrated for gothic, gonzo and the weird. His features, posts, articles and interviews have been published in People Magazine, ATKV Taalgenoot, LitNet, The Citizen, Funds for Writers, and The South African, among other publications.

The post From New Journalism to Modern Gonzo: Joan Didion, Gail Sheehy & Barbara Ehrenreich appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 27, 2024

Mae V. Cowdery, a Harlem Renaissance Poet to Rediscover

Mae Virginia Cowdery (also known as Mae V. Cowdery; January 10, 1909 – November 2, 1948) is an under-appreciated poetic voice from the Harlem Renaissance era of the 1920s. A selection of her earlier poems is presented here.

Mae was the only child of professional parents who were part of Philadelphia’s Black elite. They instilled in her their values of racial pride, equality, and respect for the arts.

Above right, Mae in 1928 at age nineteen, sporting an androgynous look.

While still a student at the Philadelphia High School for Girls, three of Mae’s poems were published in Black Opals, a prestigious short-lived (1927 – 1928) literary journal of a Philadelphia cultural organization of the same name.

For the fledgling poet, 1927 was a banner year. In addition to publication in Black Opals, she won first prize for her poem “Longings” in an NAACP-sponsored competition. It was published in the association’s journal, The Crisis. She won the Krigwa Prize for “Lamps, ” and “Dusk” was chosen for Ebony and Topaz, an anthology of Black poets published that same year.

Mae attended Pratt Institute in Brooklyn with the aim of studying fashion design. Though she didn’t complete her studies, her sojourn in New York City was an entry into the lively cultural scene in Greenwich Village. Perhaps that’s where she encountered the poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay, whose poetry she admired. She also enjoyed a lively correspondence with Langston Hughes, who greatly encouraged her poetic endeavors.

After her early successes, she continued to have her poems published in journals and anthologies highlighting writers now associated with the Harlem Renaissance.

In 1936, Mae produced a limited edition of 350 copies of We Lift Our Voices: And Other Poems, which was critically well received. And because there were relatively few copies printed, it’s difficult to obtain this book.

Not yet in the public domain, its contents are not freely distributed online. I was fortunate enough to see one of the rare copies in the main branch of the New York Public Library, and the poetry is just beautiful. Hopefully it can become more widely available when it falls into the public domain.

Mae’s bisexual life was an open a secret. Desire for both male and female love objects were expressed in her poetry. “Dusk” (1927), for example, begins: Like you / Letting down your / Purpled shadowed hair /To hide the rose and gold / Of your loveliness … In “Love in These Days” a relationship sours between a woman and a man: Her eyes were hard / And his bitter / As they sat and watched / The fire fade …

After her sojourn in New York City, Mae returned to Philadelphia, married twice, had a daughter, and her life folded into the city’s Black elite. Society columns depicted her public persona as a young society matron, impeccably attired in dresses and pearls, a contrast to her androgynous portrait at age nineteen shown at the top of this post.

It’s not clear why Mae took her own life at the age of thirty-nine (in 1948). Her obituary made no mention that she was a published poet. Philadelphia-based anthropologist and activist Arthur Huff Fauset (half-brother of Jessie Redmon Fauset) wrote that Mae was “a flame that burned out rapidly … a flash in the pan with great potential who just wouldn’t settle down.” To be fair, we don’t know if she wouldn’t, or simply couldn’t, due to external pressures to conform.

Numbering more than sixty exquisite poems, Mae Cowdery’s body of work is significant, even in comparison to those contemporaries of the Harlem Renaissance era who have remained known. One of the best overviews of her brief life can be found in Aphrodite’s Daughters: Three Modernist Poets of the Harlem Renaissance by Maureen Honey (Rutgers University Press, 2016).

The following is a selection of poems by Mae Virginia Cowdery are in the public domain.

LampsLongingsThe Wind BlowsDuskTimeGoalHidden MoonMy BodyNamelessLove in These DaysA PrayerOf the EarthWant. . . . . . . . . .

LampsBodies are lamps

And their life is the light.

Ivory, Gold, Bronze and Ebony—

Yet all are lamps

And their lives the lights.

Dwelling in the tabernacles

Of the most high—are lamps.

Lighting the weary pilgrims’ way

As they travel the dreary night—are lamps.

Swinging aloft in great Cathedrals

Beaming on rich and poor alike—are lamps.

Flickering fitfully in harlot dives

Wanton as they that dwell therein— are lamps.

Ivory, Gold, Bronze and Ebony—

Yet all are lamps

And their lives the lights.

Some flames rise high above the horizon

And urge others to greater power.

Some burn steadfast thru the night

To welcome the prodigal home.

Others flicker weakly, lacking oil to burn

And slowly die unnoticed.

What matter how bright the flame

How weak?

What matter how high it blazes

How low?

A puff of wind will put it out.

You and I are lamps—Ebony lamps,

Our flame glows red and rages high within

But our ebon shroud becomes a shadow

And our light seems weak and low.

Break that shadow

And let the flame illumine heaven

Or blow wind…blow

And let our feeble lights go out.

(The Crisis, December 1927. This poem was one of two poems by Mae Cowdery that won first prize in the 1927 poetry competition in The Crisis, along with the next poem, “Longings”)

. . . . . . . . . .

LongingsTo dance—

In the light of moon,

A platinum moon

Poised like a slender dagger

On the velvet darkness of night.

To dream—

’Neath the bamboo trees

On the sable breast

Of earth—

And listen to the wind.

To croon—

Weird sweet melodies

Round the cabin door

With banjos clinking softly—

And from out the shadow

Hear the beat of tom-toms

Resonant through the years.

To plunge—

My brown body

In a golden pool,

And lazily float on the swell

Watching the rising sun.

To stand—

On a purple mountain

Hidden from earth

By mists of dreams

And tears—

To talk—

With God.

(The Crisis, December 1927)

. . . . . . . . . .

The Wind BlowsThe wind blows.

My soul is like a tree

Lifting its face to the sun,

Flinging wide its branches

To catch the falling rain,

To breathe into itself a fragrance

Of far-off fields of clover,

Of hidden vales of violets,—

The wind blows,—

It is spring!

The wind blows.

My soul is like sand,

Hot, burning sand

That drifts and drifts

Caught by the wind,

Swirling, stinging, swarting,

Silver in the moonlight.

Soft breath of lovers’ feet

Lulled to sleep by the lap of waves,

The wind blows—

It is summer!

The wind blows.

My soul is still

In silent reverie

Hearing sometimes a sigh

As the frost steals over the land

Nipping everywhere.

Earth is dead.

The woods are bare.

The last leaf is gone.

Nipped by death’s bitter frost,

My youth grown grey

Awaits the coming of

The new year.

The wind blows,—

It is winter!

(Opportunity, October 1927)

. . . . . . . . . .

DuskLike you

Letting down your

Purpled shadowed hair

To hide the rose and gold

Of your loveliness

And your eyes peeping thru

Like beacon lights

In the gathering darkness.

(Ebony and Topaz, 1927)

. . . . . . . . .

TimeI used to sit on a high green hill

And long for you to be like the clouds,

Soft and white……….

And you eyes be like heaven’s blue

And your hair like the tree sifted sun……….

But then I was young, and my eyes yet

Round with wonder.

Now I site by an endless road and watch

As you come……….swiftly like dusk

Your hair like a starless night

Your eyes like deep violet shadows,

And soft arms cradle me on your sweet

Brown breast……….for I have grown old

And my eyes hold unshed tears,

And my face is lean and hard in daylight’s

Mocking glare.

But with the night

Dusk fingers and lips like dew

Erase each wound of time

And my eyes grow round with wonder

At your beauty.

(Black Opals, Christmas 1927)

. . . . . . . . . .

GoalMy words shall drip

Like molten lava

From the towering black volcano,

On the sleeping town

’Neath its summit.

My thoughts shall be

Hot ashes

Burning all in its path.

I shall not stop

Because critics sneer,

Nor stoop to fawning

At man’s mere fancy.

I shall breathe

A clearer freer air

For I shall see the sun

Above the crowd,

I shall not blush

And make excuse

When a son of Adam,

Who calls himself

“God’s Layman,”

Slashes with scorn

A thing born from

Truth’s womb and nursed

By beauty. It will not

Matter who stoops

To cast the first stone.

Does not my spirit

Soar above these feeble

Minds? thoughts born

From prejudice’s womb

And nursed by tradition?

I will shatter the wall

Of darkness that rises

From gleaming day

And seeks to hide the sun.

I will turn this wall of

Darkness (that is night)

Into a thing of beauty.

I will take from the hearts

Of black men–

Prayers their lips

Are ‘fraid to utter.

And turn their coarseness

Into a beauty of the jungle

Whence they came.

The lava from the black volcano

Shall be words–the ashes–thoughts

Of all men.

(Black Opals, Spring 1927)

. . . . . . . . . .

Hidden MoonMy thoughts soared up

To the starless sky

And a cloud

Passed over the face

Of the yellow moon.

My thoughts

Are the clouds that hide

The face of the moon,

And yours are

The night wind

That blows away the ugly

Moon clouds.

(Black Opals, Spring 1927)

. . . . . . . . . .

My BodyMy body

Is an ugly thing

Fashioned by God.

My body

Is an empty thing

Made from crumbling sod.

My soul

Is a lovely thing

Fashioned by God.

My soul

Is a flaming thing

That trampling hordes

Have left untrod.

(Black Opals, Spring 1927)

. . . . . . . . .

NamelessHow like the restless beating

Of our hearts

Is the surge of the sea;

How like the tumult

Of our souls

Is the lashing of the storm;

How like the yearning

In our song

Is the wind,

How like a prayer

Is night.

(Black Opals, Christmas 1928)

. . . . . . . . . .

Love in These DaysHer eyes were hard

And his bitter

As they sat and watched

The fire fade

From the ashes of their love.

Then they turned

And saw the naked autumn wind

Shake the bare autumn trees,

And each one thought

As the cold came in–

……..”It might have been”……..

(Black Opals, June 1928)

. . . . . . . . . . .

A PrayerI saw a dark boy

Trudging on the road

(Twas’ a dreary road Blacker than night).

Oft times he’d stumble

And stagger ‘neath his burden

But still he kept trudging

Along that dreary road.

I heard a dark boy

Singing as he passed

Oft times he’d laugh

But still a tear

Crept thru his song,

As he kept trudging

Along that weary road.

I saw a long white mist roll down

And cover all the earth

(There wasn’t even a shadow

To tell it was night).

And then there came an echo . . . .

. . . . Footsteps of a dark boy

Still climbing on the way.

A song with its tear

And then a prayer

From the lips of a dark boy

Struggling thru the fog.

Oft times I’d hear

The lashing of a whip

And then a voice would cry to heaven

“Lord! . . . Lord!

Have mercy! . . . mercy!”

And still that bleeding body

Pushed onward thru the fog .

Song . . . Tears . . . Blood . . . Prayer

Throbbing thru the mist.

The mist rolled by

And the sun shone fair,

Fair and golden

On a dark boy . . . . cold and still

High on a bare bleak tree

His face upturned to heaven

His soul upraised in song

“Peace. . . . Peace

Rest in the Lord.”

Oft times in the twilight

I can hear him still singing

As he walks in the heavens,

A song without a tear

A prayer without a plea.

Lord, lift me up to the purple sky

That lays its hand of stars

Tenderly on my bowed head

As I kneel high on this barren hill.

My song holds naught but tears

My prayer is but a plea

Lord take me to the clouds

To sleep . . . to sleep.

(The Crisis, September 1928)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Of the EarthA mountain

Is earth’s mouth . . .

She thrusts her lovely

Sun painted lips

To the clouds . . . for heaven’s kiss.

A tree

Is earth’s soul . . .

She raises her verdant

Joyous prayer

To the slowly sinking sun

And to evening’s dew.

She flings her rugged defiance

To hell’s grumbling wrath

And deadly smile;

Then rustles her thanksgiving

To the dawn.

A river

Is earth’s tears . . .

Flowing from her deep brown bosom

To the horizon of

Oblivion . . .

O! Earth, why do you weep?

(The Carolina Magazine, May 1928)

. . . . . . . . . .

WantI want to take down with my hands

The silver stars

That grow in heaven’s dark blue meadows

And bury my face in them.

I want to wrap all around me

The silver shedding of the moon

To keep me warm.

I want to sell my soul

To the wind in a song

To keep me from crying in the night.

I want to wake and find

That I have slept the day away,

Only nights are kind now . . .

With the stars . . . moons . . . winds and me . . .

(The Crisis, November 1928)

See also:

Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance to Rediscover and Read

Books on women writers of the Harlem Renaissance on Bookshop.org *

* This is a Bookshop.org affiliate link. If a product is purchased after linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps us to keep growin.

The post Mae V. Cowdery, a Harlem Renaissance Poet to Rediscover appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 18, 2024

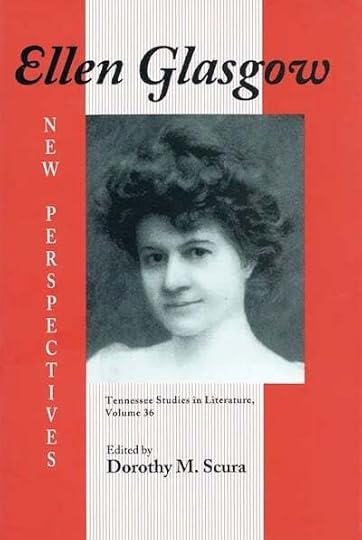

Ellen Glasgow, Southern Writer Worth Rediscovering

Ellen Glasgow (April 22, 1873 – November 21, 1945) was one of the South’s most eminent writers of her day. Today she’s far less known than contemporaries like Edith Wharton and Willa Cather, despite having created an impressive body of work.

Ellen’s output included novels, collections of short stories and poems, a treatise on how to write fiction, and an autobiography. She was also the recipient of the Pulitzer Prize in 1942. Today, if she is remembered for anything, it’s more for her influence than her literary talent.

It’s well worth rediscovering this often overlooked writer.

Early years

Ellen Anderson Gholson Glasgow was born in Richmond, Virginia to Francis Thomas and Anne Jane Gholson Glasgow. Her father, of Scotch-Irish descent, was from the Shenandoah Valley and studied at Washington and Lee College. Her mother was from an upper-crust family in Cumberland County with many illustrious ancestors.

The dynamics of family life had an enormous influence on the young Ellen. Her mother, who gave birth to ten children, suffered from nerves and depression. Her father, a rough, blunt man who had affairs, ran Tredegar Iron Works, which supplied most of the munitions during the Civil War.

Ellen’s parents decided her health was fragile and she was too headstrong for school, so she was educated at home. Lucky for this smart, curious, young lady, she had access to her father’s library and read voraciously: history, literature, and philosophy.

Over the years she was influenced by thinkers like Freud, Schopenhauer, and Darwin. Asserting her independence, she told her parents she would not make her debut, a right of passage for aristocratic southern young ladies.

Ellen was twenty when her mother died. This had a profound impact on her, and she never fully forgave her father for his ill-treatment of her mother.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Reshaping the literature of the SouthEllen Glasgow’s writing sparked a reshaping of the literature of the South. Her novels studied the changing culture and the roles of men and women, leaving behind the sentimental stories of olden times: the plantation houses surrounded by magnolias in the distance, the slaves toiling in the fields, all with the backdrop of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Most of her books, set in Virginia, were social histories of the region as it changed from an agrarian to an industrial society and women’s roles transformed; she can be considered an early feminist who certainly resented the strictures placed on her by society.

Ellen left a generous body of work: some twenty novels; books of short stories and poems; essays; articles; and a memoir and collection of letters published posthumously. See her full bibliography.

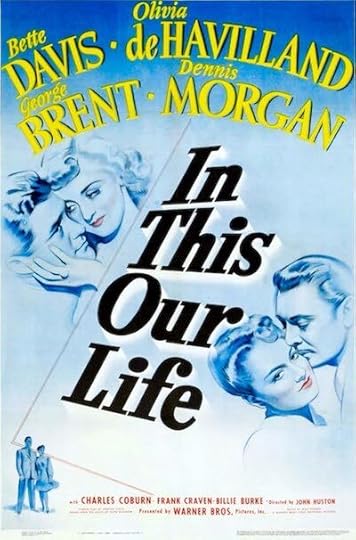

In 1940 Ellen was awarded the Howells Medal of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 1942, she was awarded the Pulitzer for her novel, In This Our Life. By then, she was aging, suffering from poor health, and winding down as a writer. In This Our Life was released as a 1942 film directed by John Huston, starring Bette Davis and Olivia de Havilland.

A memorable quote from In This Our Life: “Why do all of us, every last one, have to go through hell to find out what we really want?”

The Encyclopedia of Southern Culture cites seven novels as her best efforts. The Deliverance (1904) depicts class conflict after the Civil War; her trilogy about women: Virginia (1913), Life and Gabriella (1916), and Barren Ground (1925) – stories about strong females who rebel against their roles in society. Further, she wrote three comedies of manners: The Romantic Comedians (1926), They Stooped to Folly (1929), and The Shelter of Life (1932).

. . . . . . . . . . .

The 1942 film adaptation of

Ellen Glasgow’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel

. . . . . . . . . . .

Troubles in life and loveIn life, suffering can often lead to a heavy heart, a soulful depth of experience, and — good writing. Ellen Glasgow had more than her share of troubles. In addition to having little respect for her father and losing her beloved mother at such an impressionable age, she was a sickly child who battled debilitating deafness during her adult years. She lost her favorite sister Cary to cancer and later, her brother Frank and brother-in-law George McCormack (Cary’s husband) to suicide.

In her twenties, she had an affair with a married man we only know as Gerald B., who later died. Ellen’s love life continued to be unlucky. For years she was quietly engaged to handsome Richmond attorney Henry Watkins Anderson, who was deeply involved with The Red Cross during World War II.

Anderson was assigned to the Red Cross Commission in the Balkans, where he began an affair with the beautiful Queen Marie of Romania (who also happened to be married). After some time, when Anderson returned to Richmond, he was still smitten with the Queen and couldn’t stop talking about her. Despairing, Ellen overdosed on sleeping pills one night. Yet she survived, and out of the ashes of misery came creativity. She kept writing and her reputation grew.

Animal advocacy

Ellen had a great passion for social justice and was also very involved in animal advocacy. One of her charities was the Richmond SPCA. She encouraged many prominent citizens like Douglas Southall Freeman and James Branch Cabell to donate and get involved, and she was president of the board for twenty-one years, right up until her death; she was the driving force behind opening the city’s first shelter.

According to the SPCA website, Ellen bequeathed the bulk of her estate and the rights to her work to this organization which gave them the seed for their endowment. All this was left in honor of her Sealyham Terrier Jeremy.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Ellen Glasgow’s legacyEllen had a wealth of interesting friends, including Allen Tate, James Branch Cabell, and H.L. Mencken. Her friend Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings was writing her biography but died before its completion.

This erudite, well-traveled, glass-ceiling-breaker was known for her grand entertaining at her Greek Revival mansion at 1 West Main in downtown Richmond. Once she even had a party for Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas while they were on their American tour.

(An interesting note, in 2024, her house went up for sale for $1.395 million — 11,000 square feet, with all the beautiful historical details intact)

Biographer Susan Goodman described Ellen Glasgow’s style as poetic realism. She influenced writers like Eudora Welty, Robert Penn Warren, and William Faulkner. Here’s hoping that a reconsideration of her works spreads beyond literary buffs and researchers.

Ellen Glasgow died in her sleep on November 21, 1945, likely from heart disease. She is buried in Richmond’s historic Hollywood Cemetery with her beloved Jeremy alongside. Her epitaph reads: “Tomorrow to Fresh Woods and Pastures New.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Tyler Scott, who has been writing essays and articles since the early 1980s for various magazines and newspapers. In 2014 she published her novel The Excellent Advice of a Few Famous Painters. She lives in Blackstone, Virginia where she and her husband renovated a Queen Anne Revival house and enjoy small town life. Visit her at Pour the Coffee, Time to Write.

Further reading and sourcesGoodman, Susan. Ellen Glasgow, A Biography. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1998Reagan, Wilson and Freeis, William. Documenting the American South, Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. University of North Carolina Press, 1989: Ellen Anderson Gholson Glasgow, 1873-1945 Mambrol, Nassullah. Analysis of Ellen Glasgow’s Novels – Literary Theory and Criticism . June 2, 2018. Berke, Amy. Bleil, Robert, Cofer, Jordan. Davis, Doug, Ellen Glasgow, American Literature After 1865, Chapter 76, Pressbooks: Ellen Glasgow (1873 – 1945) – American Literatures After 1865 Schwarting, Paulette. Ellen Glasgow’s Broken Heart | Virginia Museum of History & Culture Encyclopedia Britannica, Ellen Glasgow, American Author, Oct. 30, 2024.Starr, Robin, Richmond SPCA blog. June 8, 2011: 120 Years of History: Accomplishments of the early 1900’s and the leadership of Ellen Glasgow (Richmond SPCA Blog)

The post Ellen Glasgow, Southern Writer Worth Rediscovering appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 14, 2024

Anarchism: What it Really Stands for by Emma Goldman (1911)

Emma Goldman (1869 – 1940) was a noted political activist and promoter of the anarchist philosophy. She was best known for her role in the development oof its theories in the early twentieth century.

As such, “Anarchism: What it Really Stands For” is a 1911 essay that crystalizes her views. Anarchism, in brief, argues against all forms of authority the abolishment of institutions of government, advocating for replacing them with stateless societies.

Goldman’s views seem particularly resonant — and relevant — in this age of government overreach into privacy and personal freedom.

In 1906, Goldman founded the Mother Earth Journal, serving as its editor and writing as a frequent contributor. The essay that follows was originally published as a pamphlet (priced ten cents) by Mother Earth Publishing Association, in 1911. It is in the public domain.

Anarchism: What it Really Stands for by Emma Goldman

The history of human growth and development is at the same time the history of the terrible struggle of every new idea heralding the approach of a brighter dawn. In its tenacious hold on tradition, the Old has never hesitated to make use of the foulest and crudest means to stay the advent of the New, in whatever form or period the latter may have asserted itself.

Nor need we retrace our steps into the distant past to realize the enormity of opposition, difficulties, and hardships placed in the path of every progressive idea. The rack, the thumbscrew, and the knout are still with us; so are the convict’s garb and the social wrath, all conspiring against the spirit that is serenely marching on.

Anarchism could not hope to escape the fate of all other ideas of innovation. Indeed, as the most revolutionary and uncompromising innovator, Anarchism must needs meet with the combined ignorance and venom of the world it aims to reconstruct.

To deal even remotely with all that is being said and done against Anarchism would necessitate the writing of a whole volume. I shall therefore meet only two of the principal objections. In so doing, I shall attempt to elucidate what Anarchism really stands for.

The strange phenomenon of the opposition to Anarchism is that it brings to light the relation be tween so-called intelligence and ignorance. And yet this is not so very strange when we consider the relativity of all things.

The ignorant mass has in its favor that it makes no pretense of knowledge or tolerance. Acting, as it always does, by mere impulse, its reasons are like those of a child. “Why?” “Because.” Yet the opposition of the uneducated to Anarchism deserves the same consideration as that of the intelligent man.

What, then, are the objections? First, Anarchism is impractical, though a beautiful ideal. Second, Anarchism stands for violence and destruction, hence it must be repudiated as vile and dangerous. Both the intelligent man and the ignorant mass judge not from a thorough knowledge of the subject, but either from hearsay or false interpretation.

. . . . . . . . . . .

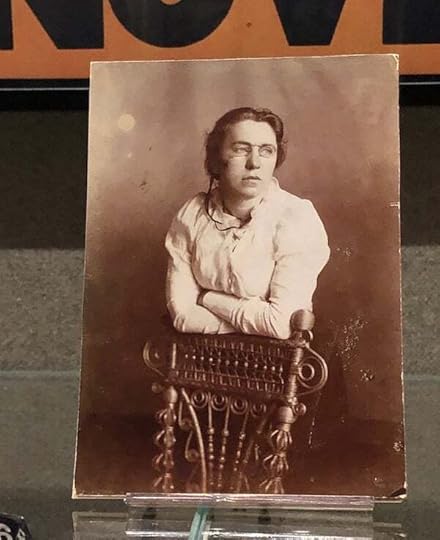

Emma Goldman (International Institute of Social History)

. . . . . . . . . . .

A practical scheme, says Oscar Wilde, is either one already in existence, or a scheme that could be carried out under the existing conditions; but it is exactly the existing conditions that one objects to, and any scheme that could accept these conditions is wrong and foolish.

The true criterion of the practical, therefore, is not whether the latter can keep intact the wrong or foolish; rather is it whether the scheme has vitality enough to leave the stagnant waters of the old, and build, as well as sustain, new life. In the light of this conception, Anarchism is indeed practical. More than any other idea, it is helping to do away with the wrong and foolish; more than any other idea, it is building and sustaining new life.

The emotions of the ignorant man are continuously kept at a pitch by the most blood-curdling stories about Anarchism. Not a thing too outrageous to be employed against this philosophy and its exponents. Therefore Anarchism represents to the unthinking what the proverbial bad man does to the child,—a black monster bent on swallowing everything; in short, destruction and violence.

Destruction and violence! How is the ordinary man to know that the most violent element in society is ignorance; that its power of destruction is the very thing Anarchism is combating?

Nor is he aware that Anarchism, whose roots, as it were, are part of nature’s forces, destroys, not healthful tissue, but parasitic growths that feed on the life’s essence of society. It is merely clearing the soil from weeds and sagebrush, that it may eventually bear healthy fruit.

Someone has said that it requires less mental effort to condemn than to think. The widespread mental indolence, so prevalent in society, proves this to be only too true.

Rather than to go to the bottom of any given idea, to examine into its origin and meaning, most people will either condemn it altogether, or rely on some superficial or prejudicial definition of non-essentials.

Anarchism urges man to think, to investigate, to analyze every proposition; but that the brain capacity of the average reader be not taxed too much, I also shall begin with a definition, and then elaborate on the latter.

ANARCHISM: The philosophy of a new social order based on liberty unrestricted by man-made law; the theory that all forms of government rest on violence, and are therefore wrong and harmful, as well as unnecessary.

The new social order rests, of course, on the materialistic basis of life; but while all Anarchists agree that the main evil today is an economic one, they maintain that the solution of that evil can be brought about only through the consideration of every phase of life,—individual, as well as the collective; the internal, as well as the external phases.

A thorough perusal of the history of human development will disclose two elements in bitter conflict with each other; elements that are only now beginning to be understood, not as foreign to each other, but as closely related and truly harmonious, if only placed in proper environment: the individual and social instincts.

The individual and society have waged a relentless and bloody battle for ages, each striving for supremacy, because each was blind to the value and importance of the other. The individual and social instincts,—the one a most potent factor for individual endeavor, for growth, aspiration, self-realization; the other an equally potent factor for mutual helpfulness and social well-being.

The explanation of the storm raging within the individual, and between him and his surroundings, is not far to seek. The primitive man, unable to understand his being, much less the unity of all life, felt himself absolutely dependent on blind, hidden forces ever ready to mock and taunt him.

Out of that attitude grew the religious concepts of man as a mere speck of dust dependent on superior powers on high, who can only be appeased by complete surrender. All the early sagas rest on that idea, which continues to be the leit-motif of the biblical tales dealing with the relation of man to God, to the State, to society.

Again and again the same motif, man is nothing, the powers are everything. Thus Jehovah would only endure man on condition of complete surrender. Man can have all the glories of the earth, but he must not become conscious of himself. The State, society, and moral laws all sing the same refrain: Man can have all the glories of the earth, but he must not become conscious of himself.

Anarchism is the only philosophy which brings to man the consciousness of himself; which maintains that God, the State, and society are non-existent, that their promises are null and void, since they can be fulfilled only through man’s subordination.

Anarchism is therefore the teacher of the unity of life; not merely in nature, but in man. There is no conflict between the individual and the social instincts, any more than there is between the heart and the lungs: the one the receptacle of a precious life essence, the other the repository of the element that keeps the essence pure and strong.

The individual is the heart of society, conserving the essence of social life; society is the lungs which are distributing the element to keep the life essence—that is, the individual—pure and strong.

“The one thing of value in the world,” says Emerson, “is the active soul; this every man contains within him. The soul active sees absolute truth and utters truth and creates.” In other words, the individual instinct is the thing of value in the world. It is the true soul that sees and creates the truth alive, out of which is to come a still greater truth, the re-born social soul.

Anarchism is the great liberator of man from the phantoms that have held him captive; it is the arbiter and pacifier of the two forces for individual and social harmony. To accomplish that unity, Anarchism has declared war on the pernicious influences which have so far prevented the harmonious blending of individual and social instincts, the individual and society.

Religion, the dominion of the human mind; Property, the dominion of human needs; and Government, the dominion of human conduct, represent the stronghold of man’s enslavement and all the horrors it entails.

Religion! How it dominates man’s mind, how it humiliates and degrades his soul. God is everything, man is nothing, says religion. But out of that nothing God has created a kingdom so despotic, so tyrannical, so cruel, so terribly exacting that naught but gloom and tears and blood have ruled the world since gods began.

Anarchism rouses man to rebellion against this black monster. Break your mental fetters, says Anarchism to man, for not until you think and judge for yourself will you get rid of the dominion of darkness, the greatest obstacle to all progress.

Property, the dominion of man’s needs, the denial of the right to satisfy his needs. Time was when property claimed a divine right, when it came to man with the same refrain, even as religion, “Sacrifice! Abnegate! Submit!”

The spirit of Anarchism has lifted man from his prostrate position. He now stands erect, with his face toward the light. He has learned to see the insatiable, devouring, devastating nature of property, and he is preparing to strike the monster dead.

“Property is robbery,” said the great French Anarchist, Proudhon. Yes, but without risk and danger to the robber. Monopolizing the accumulated efforts of man, property has robbed him of his birthright, and has turned him loose a pauper and an outcast.

Property has not even the time-worn excuse that man does not create enough to satisfy all needs. The A B C student of economics knows that the productivity of labor within the last few decades far exceeds normal demand a hundredfold. But what are normal demands to an abnormal institution?

The only demand that property recognizes is its own gluttonous appetite for greater wealth, because wealth means power: the power to subdue, to crush, to exploit, the power to enslave, to outrage, to degrade.

America is particularly boastful of her great power, her enormous national wealth. Poor America, of what avail is all her wealth, if the individuals comprising the nation are wretchedly poor? If they live in squalor, in filth, in crime, with hope and joy gone, a homeless, soilless army of human prey.

It is generally conceded that unless the returns of any business venture exceed the cost, bankruptcy is inevitable. But those engaged in the business of producing wealth have not yet learned even this simple lesson.

Every year the cost of production in human life is growing larger (50,000 killed, 100,000 wounded in America last year); the returns to the masses, who help to create wealth, are ever getting smaller.

Yet America continues to be blind to the inevitable bankruptcy of our business of production. Nor is this the only crime of the latter. Still more fatal is the crime of turning the producer into a mere particle of a machine, with less will and decision than his master of steel and iron.

Man is being robbed not merely of the products of his labor, but of the power of free initiative, of originality, and the interest in, or desire for, the things he is making.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Real wealth consists in things of utility and beauty, in things that help to create strong, beautiful bodies and surroundings inspiring to live in. But if man is doomed to wind cotton around a spool, or dig coal, or build roads for thirty years of his life, there can be no talk of wealth.

What he gives to the world is only gray and hideous things, reflecting a dull and hideous existence,—too weak to live, too cowardly to die. Strange to say, there are people who extol this deadening method of centralized production as the proudest achievement of our age.

They fail utterly to realize that if we are to continue in machine subserviency, our slavery is more complete than was our bondage to the King. They do not want to know that centralization is not only the death knell of liberty, but also of health and beauty, of art and science, all these being impossible in a clock like, mechanical atmosphere.

Anarchism cannot but repudiate such a method of production: its goal is the freest possible expression of all the latent powers of the individual. Oscar Wilde defines a perfect personality as “one who develops under perfect conditions, who is not wounded, maimed, or in danger.”

A perfect personality, then, is only possible in a state of society where man is free to choose the mode of work, the conditions of work, and the freedom to work.

One to whom the making of a table, the building of a house, or the tilling of the soil, is what the painting is to the artist and the discovery to the scientist—the result of inspiration, of intense longing, and deep interest in work as a creative force.

That being the ideal of Anarchism, its economic arrangements must consist of voluntary productive and distributive associations, gradually developing into free communism, as the best means of producing with the least waste of human energy. Anarchism, however, also recognizes the right of the individual, or numbers of individuals, to arrange at all times for other forms of work, in harmony with their tastes and desires.

Such free display of human energy being possible only under complete individual and social freedom. Anarchism directs its forces against the third and greatest foe of all social equality; namely, the State, organized authority, or statutory law,—the dominion of human conduct.

Just as religion has fettered the human mind, and as property, or the monopoly of things, has subdued and stifled man’s needs, so has the State enslaved his spirit, dictating every phase of conduct.

“All government in essence,” says [Ralph Waldo] Emerson, “is tyranny.” It matters not whether it is government by divine right or majority rule. In every instance its aim is the absolute subordination of the individual.

Referring to the American government, the greatest American Anarchist, [Henry] David Thoreau, said: “Government, what is it but a tradition, though a recent one, endeavoring to transmit itself unimpaired to posterity, but each instance losing its integrity; it has not the vitality and force of a single living man. Law never made man a whit more just; and by means of their respect for it, even the well disposed are daily made agents of injustice.”

Indeed, the keynote of government is injustice. With the arrogance and self-sufficiency of the King who could do no wrong, governments ordain, judge, condemn, and punish the most insignificant offenses, while maintaining themselves by the greatest of all offenses, the annihilation of individual liberty.

Thus Ouida is right when she maintains that “the State only aims at instilling those qualities in its public by which its demands are obeyed, and its exchequer is filled. Its highest attainment is the reduction of mankind to clockwork. In its atmosphere all those finer and more delicate liberties, which require treatment and spacious expansion, inevitably dry up and perish.

The State requires a taxpaying machine in which there is no hitch, an exchequer in which there is never a deficit, and a public, monotonous, obedient, colorless, spiritless, moving humbly like a flock of sheep along a straight high road between two walls.”

Yet even a flock of sheep would resist the chicanery of the State, if it were not for the corruptive, tyrannical, and oppressive methods it employs to serve its purposes.

Therefore Bakunin repudiates the State as synonymous with the surrender of the liberty of the individual or small minorities—the destruction of social relationship, the curtailment, or complete denial even, of life itself, for its own aggrandizement.

The State is the altar of political freedom and, like the religious altar, it is maintained for the purpose of human sacrifice.

In fact, there is hardly a modern thinker who does not agree that government, organized authority, or the State, is necessary only to maintain or protect property and monopoly. It has proven efficient in that function only.

Even George Bernard Shaw, who hopes for the miraculous from the State under Fabianism, nevertheless admits that “it is at present a huge machine for robbing and slave-driving of the poor by brute force.” This being the case, it is hard to see why the clever prefacer wishes to uphold the State after poverty shall have ceased to exist.

Unfortunately there are still a number of people who continue in the fatal belief that government rests on natural laws, that it maintains social order and harmony, that it diminishes crime, and that it prevents the lazy man from fleecing his fellows. I shall therefore examine these contentions.

A natural law is that factor in man which asserts itself freely and spontaneously without any external force, in harmony with the requirements of nature. For instance, the demand for nutrition, for sex gratification, for light, air, and exercise, is a natural law. But its expression needs not the machinery of government, needs not the club, the gun, the handcuff, or the prison.

To obey such laws, if we may call it obedience, requires only spontaneity and free opportunity. That governments do not maintain themselves through such harmonious factors is proven by the terrible array of violence, force, and coercion all governments use in order to live. Thus Blackstone is right when he says, “Human laws are invalid, because they are contrary to the laws of nature.”

Unless it be the order of Warsaw after the slaughter of thousands of people, it is difficult to ascribe to governments any capacity for order or social harmony. Order derived through submission and maintained by terror is not much of a safe guaranty; yet that is the only “order” that governments have ever maintained.

True social harmony grows naturally out of solidarity of interests. In a society where those who always work never have anything, while those who never work enjoy everything, solidarity of interests is non-existent; hence social harmony is but a myth.

The only way organized authority meets this grave situation is by extending still greater privileges to those who have already monopolized the earth, and by still further enslaving the disinherited masses. Thus the entire arsenal of government—laws, police, soldiers, the courts, legislatures, prisons,—is strenuously engaged in “harmonizing” the most antagonistic elements in society.

The most absurd apology for authority and law is that they serve to diminish crime. Aside from the fact that the State is itself the greatest criminal, breaking every written and natural law, stealing in the form of taxes, killing in the form of war and capital punishment, it has come to an absolute standstill in coping with crime. It has failed utterly to destroy or even minimize the horrible scourge of its own creation.

Crime is naught but misdirected energy. So long as every institution of today, economic, political, social, and moral, conspires to misdirect human energy into wrong channels; so long as most people are out of place doing the things they hate to do, living a life they loathe to live, crime will be inevitable, and all the laws on the statutes can only in crease, but never do away with, crime.

What does society, as it exists today, know of the process of despair, the poverty, the horrors, the fearful struggle the human soul must pass on its way to crime and degradation. Who that knows this terrible process can fail to see the truth in these words of Peter Kropotkin:

“Those who will hold the balance between the benefits thus attributed to law and punishment and the degrading effect of the latter on humanity; those who will estimate the torrent of depravity poured abroad in human society by the informer, favored by the Judge even, and paid for in clinking cash by governments, under the pretext of aiding to unmask crime; those who will go within prison walls and there see what human beings become when deprived of liberty, when subjected to the care of brutal keepers, to coarse, cruel words, to a thousand stinging, piercing humiliations, will agree with us that the entire apparatus of prison and punishment is an abomination which ought to be brought to an end.”

The deterrent influence of law on the lazy man is too absurd to merit consideration. If society were only relieved of the waste and expense of keeping a lazy class, and the equally great expense of the paraphernalia of protection this lazy class requires, the social tables would contain an abundance for all, including even the occasional lazy individual.

Besides, it is well to consider that laziness results either from special privileges, or physical and mental abnormalities. Our present insane system of production fosters both, and the most astounding phenomenon is that people should want to work at all now.

Anarchism aims to strip labor of its deadening, dulling aspect, of its gloom and compulsion. It aims to make work an instrument of joy, of strength, of color, of real harmony, so that the poorest sort of a man should find in work both recreation and hope.

To achieve such an arrangement of life, government, with its unjust, arbitrary, repressive measures, must be done away with. At best it has but imposed one single mode of life upon all, without regard to individual and social variations and needs.

In destroying government and statutory laws, Anarchism proposes to rescue the self-respect and independence of the individual from all restraint and invasion by authority. Only in freedom can man grow to his full stature.

Only in freedom will he learn to think and move, and give the very best in him. Only in freedom will he realize the true force of the social bonds which knit men together, and which are the true foundation of a normal social life.

But what about human nature? Can it be changed? And if not, will it endure under Anarchism?

Poor human nature, what horrible crimes have been committed in thy name! Every fool, from king to policeman, from the flat-headed parson to the visionless dabbler in science, presumes to speak authoritatively of human nature. The greater the mental charlatan, the more definite his insistence on the wickedness and weaknesses of human nature. Yet, how can any one speak of it today, with every soul in a prison, with every heart fettered, wounded, and maimed?

John Burroughs has stated that experimental study of animals in captivity is absolutely useless. Their character, their habits, their appetites undergo a complete transformation when torn from their soil in field and forest. With human nature caged in a narrow space, whipped daily into submission, how can we speak of its potentialities?

Freedom, expansion, opportunity, and, above all, peace and repose, alone can teach us the real dominant factors of human nature and all its wonderful possibilities.

Anarchism, then, really stands for the liberation of the human mind from the dominion of religion; the liberation of the human body from the dominion of property; liberation from the shackles and restraint of government.

Anarchism stands for a social order based on the free grouping of individuals for the purpose of producing real social wealth; an order that will guarantee to every human being free access to the earth and full enjoyment of the necessities of life, according to individual desires, tastes, and inclinations.

This is not a wild fancy or an aberration of the mind. It is the conclusion arrived at by hosts of intellectual men and women the world over; a conclusion resulting from the close and studious observation of the tendencies of modern society: individual liberty and economic equality, the twin forces for the birth of what is fine and true in man.

As to methods. Anarchism is not, as some may suppose, a theory of the future to be realized through divine inspiration. It is a living force in the affairs of our life, constantly creating new conditions. The methods of Anarchism therefore do not comprise an iron-clad program to be carried out under all circumstances.

Methods must grow out of the economic needs of each place and clime, and of the intellectual and temperamental requirements of the individual. The serene, calm character of a Tolstoy will wish different methods for social reconstruction than the intense, overflowing personality of a Michael Bakunin or a Peter Kropotkin.

Equally so it must be apparent that the economic and political needs of Russia will dictate more drastic measures than would England or America. Anarchism does not stand for military drill and uniformity; it does, however, stand for the spirit of revolt, in whatever form, against everything that hinders human growth. All Anarchists agree in that, as they also agree in their opposition to the political machinery as a means of bringing about the great social change.

“All voting,” says Thoreau, “is a sort of gaming, like checkers, or backgammon, a playing with right and wrong; its obligation never exceeds that of expediency. Even voting for the right thing is doing nothing for it. A wise man will not leave the right to the mercy of chance, nor wish it to prevail through the power of the majority.”

A close examination of the machinery of politics and its achievements will bear out the logic of Thoreau.

What does the history of parliamentarism show? Nothing but failure and defeat, not even a single reform to ameliorate the economic and social stress of the people. Laws have been passed and enactments made for the improvement and protection of labor.

Thus it was proven only last year that Illinois, with the most rigid laws for mine protection, had the greatest mine disasters. In States where child labor laws prevail, child exploitation is at its highest, and though with us the workers enjoy full political opportunities, capitalism has reached the most brazen zenith.

Even were the workers able to have their own representatives, for which our good Socialist politicians are clamoring, what chances are there for their honesty and good faith?

One has but to bear in mind the process of politics to realize that its path of good intentions is full of pitfalls: wire-pulling, intriguing, flattering, lying, cheating; in fact, chicanery of every description, whereby the political aspirant can achieve success.

Added to that is a complete demoralization of character and conviction, until nothing is left that would make one hope for anything from such a human derelict. Time and time again the people were foolish enough to trust, believe, and support with their last farthing aspiring politicians, only to find themselves betrayed and cheated.

It may be claimed that men of integrity would not become corrupt in the political grinding mill. Perhaps not; but such men would be absolutely helpless to exert the slightest influence in behalf of labor, as indeed has been shown in numerous instances.

The State is the economic master of its servants. Good men, if such there be, would either remain true to their political faith and lose their economic support, or they would cling to their economic master and be utterly unable to do the slightest good. The political arena leaves one no alternative, one must either be a dunce or a rogue.

The political superstition is still holding sway over the hearts and minds of the masses, but the true lovers of liberty will have no more to do with it. Instead, they believe with Stirner that man has as much liberty as he is willing to take.

Anarchism therefore stands for direct action, the open defiance of, and resistance to, all laws and restrictions, economic, social, and moral. But defiance and resistance are illegal. Therein lies the salvation of man. Everything illegal necessitates integrity, self-reliance, and courage. In short, it calls for free, independent spirits, for “men who are men, and who have a bone in their backs which you cannot pass your hand through.”

Universal suffrage itself owes its existence to direct action. If not for the spirit of rebellion, of the defiance on the part of the American revolutionary fathers, their posterity would still wear the King’s coat. If not for the direct action of a John Brown and his comrades, America would still trade in the flesh of the black man.

True, the trade in white flesh is still going on; but that, too, will have to be abolished by direct action. Trade unionism, the economic arena of the modern gladiator, owes its existence to direct action. It is but recently that law and government have attempted to crush the trade union movement, and condemned the exponents of man’s right to organize to prison as conspirators.

Had they sought to assert their cause through begging, pleading, and compromise, trade unionism would today be a negligible quantity. In France, in Spain, in Italy, in Russia, nay even in England (witness the growing rebellion of English labor unions) direct, revolutionary, economic action has become so strong a force in the battle for industrial liberty as to make the world realize the tremendous importance of labor’s power.

The General Strike, the supreme expression of the economic consciousness of the workers, was ridiculed in America but a short time ago. Today every great strike, in order to win, must realize the importance of the solidaric general protest.

Direct action, having proved effective along economic lines, is equally potent in the environment of the individual. There a hundred forces encroach upon his being, and only persistent resistance to them will finally set him free. Direct action against the authority in the shop, direct action against the authority of the law, direct action against the invasive, meddlesome authority of our moral code, is the logical, consistent method of Anarchism.

Will it not lead to a revolution? Indeed, it will. No real social change has ever come about without a revolution. People are either not familiar with their history, or they have not yet learned that revolution is but thought carried into action.

Anarchism, the great leaven of thought, is today permeating every phase of human endeavor. Science, art, literature, the drama, the effort for economic betterment, in fact every individual and social opposition to the existing disorder of things, is illumined by the spiritual light of Anarchism.

It is the philosophy of the sovereignty of the individual. It is the theory of social harmony. It is the great, surging, living truth that is reconstructing the world, and that will usher in the Dawn.

The post Anarchism: What it Really Stands for by Emma Goldman (1911) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 8, 2024

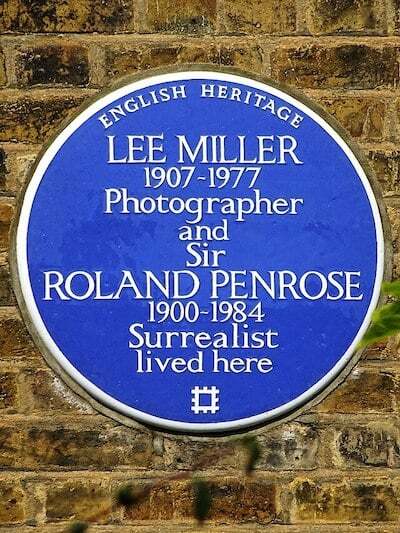

The Many Lives of Lee Miller, Photographer & War Correspondent

Elizabeth Lee Miller (April 23, 1907 – July 21, 1977), known professionally as Lee Miller, was an American photographer and war correspondent. For many years she was known as the muse and lover of Surrealist artist Man Ray.

She was extraordinarily talented in her own right, moving with ease from the fashion circles of New York, to the Surrealist circles of Paris, to front-line photography in World War II.

Her life and work has been painstakingly documented and promoted by her son Antony Penrose, and most recently has been the subject of a 2023 film produced by and starring Kate Winslet.

Early life and education

Lee was born in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1907. Her mother, Florence, was a nurse and her father Theodore was an engineer. She had two brothers: John (1905) and Erik (1910).

Theodore was a keen amateur photographer, and owned both a Kodak Brownie camera and a home darkroom. He taught Lee the basics of photography while she was just a girl. She was also his favorite model, and he took dozens of photographs of her, her friends, and her brothers over the years.

Despite having this loving family, Lee’s childhood was a difficult one. At age seven, while visiting relatives, she was raped by a family friend; this left her traumatized and suffering from a sexually transmitted disease. In the days before penicillin, the only treatment was douching with dichloride of mercury. As a nurse, it fell to Florence to administer these treatments, an experience which was horrendous for both her and Lee.

A few years later, Lee endured another tragedy when her teenage sweetheart died of heart failure while out on a lake in a rowing boat.

As a result, Lee struggled in school and was expelled several times. She did, however, show an interest in the theatre, and in an attempt to encourage her pursue something worthwhile, her parents agreed to send her to the L’École Medgyés pour la Technique du Théâtre in Paris for seven months.

She studied set design and lighting, but, as her son later wrote, she was “not one of the school’s star pupils. She was eighteen, gregarious, fabulously beautiful in the exactly the style of the period, and far more interested in celebrating her newfound freedom than in formal studies. Informally, what she was learning was what it meant to be a fully emancipated woman in charge of her own destiny.”

Lee returned to New York in 1926, where she attended the Experimental Theatre at Vassar College, studying Dramatic Production under Hallie Flannigan.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Modeling in New York City

Lee’s career as a fashion model began that winter, when the publishing magnate Condé Nast reputedly saved her from being hit by oncoming traffic as she tried to cross the road in Manhattan. Impressed by her good looks, he offered her a job as a model for Vogue.

She was on the cover of both the British and American March 1927 editions. Subsequently, she worked with some of the greatest fashion photographers of the time including Edward Steichen and George Hoyningen-Huene.

Lee was hugely successful as a model, but quickly decided that she would “rather take a picture than be one.”

She abandoned modeling altogether when, in July 1928, a photograph taken of her by Edward Steichen was used as a advertisement for Kotex sanitary towels. At the time, feminine hygiene was considered far too personal and delicate to discuss in public, and after the image was the focal point of a massive nationwide advertising campaign, Lee found herself out on a limb — though also proud of the scandal it had caused.

On the other side of the camera in Paris

Lee moved to Paris in 1929, and sought out the Surrealist artist Man Ray. For several years she was his muse, lover, confidant, and collaborator, and she also established her own photographic studio in the city. Her portrait photography was highly sought after by writers, artists, socialites, and royalty — she even photographed the pet lizard of a French socialite.

However, it was her Surrealist photographs that are probably best known from this period. Alongside Man Ray, she experimented with juxtaposition — the technique of combining two elements within the same photo — and solarization, which partially reverses the positive and negative spaces of a photo, producing halo-like outlines that emphasize both light and shadow.

Even outside of the studio, her work had a quirky style. Later, her son Antony wrote, “The thing that became her distinctive, Surrealist style was what I call the ‘found image.’ She takes a photograph of, perhaps, an everyday occurrence, and she does it in such a way that it becomes an image that is containing ‘the marvelous.’”

While in Paris, Lee became part of the Surrealist circle of artists, including Paul and Nusch Éluard, Pablo Picasso, Max Ernst, Dorothea Tanning, Leonora Carrington, and Joan Miró.

According to Antony, “When Lee arrived in Paris she had, in a way, been a Surrealist for some time — before the movement even had a name — because she had that determination to pursue her life free of the constraints of society which the Surrealists were already rebelling against. They wanted to create a new world which was not governed by religion or law or whatever…The Surrealist movement was going in tremendous force, and she was ready-made for it, and it for her.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

New York and EgyptShe and Man Ray separated in 1932. Lee returned to New York to establish another studio there with her younger brother Erik. She specialized in advertising and celebrity portraits, including photographs of actresses Lilian Harvey and Gertrude Lawrence, and continued to experiment with Surrealist styles and techniques.

Her work was included in Julian Levy’s exhibition Modern European Photographers in 1932, and he subsequently gave her a one-woman show which brought her work to the attention of the art world. Soon afterwards, she was listed by Vanity Fair as one of the “most distinguished living photographers.”

She married the wealthy Egyptian businessman Aziz Eloui Bey in 1934, and moved with him to Cairo. She became fascinated with the idea of desert travel, and photographed the pyramids, desert, villages and ruins.

The photographs show a sense of dislocation, perhaps drawn from her experiences as an expatriate, and her best-known Egyptian image, Portrait of Space, 1937, views the desert through a torn fly screen door, turning it into a dream-like, Surrealist space.

Lee continued to travel to Europe, and during a return visit to Paris in 1937 she met Roland Penrose, a Surrealist artist. They began an affair, and in 1939 she officially left Bey and moved with Penrose to London.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

See also: 8 Female Journalists of the World War II Era

. . . . . . . . . . .

In London, Lee met Audrey Withers, editor of British Vogue. It was a connection that would prove vital for both Lee and for the magazine when, in 1940, Lee photographed London during and after the Blitz. Vogue published these photos, along with several photo essays by Lee about the Auxiliary Territorial Service.

It not only gave Lee an outlet for her photography in a new country and with a new subject, but it also helped to change Vogue’s reputation from solely a luxury fashion magazine — an indulgence that wasn’t much in demand during the war years — to a magazine that also published serious news.

Lee also published her images in a book, Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain Under Fire (1941).

By 1943 she had become an accredited war correspondent through Condé Nast Publications, one of the very few women to do so, and in 1944 teamed up with Life photojournalist David E. Scherman.

She became the first female photojournalist to follow the US Army as it advanced on the front lines, and photographed major events such as the battle of Saint-Malo, the Liberation of Paris, and the liberation of both the Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps. She also taught herself to write articles, and the pieces that accompanied the photographs in print were almost always her own.

Lee was unsure whether the photos from the concentration camps would be publishable, given the horrific subject matter, but she sent them back to Vogue with a telegram: “I IMPLORE YOU TO BELIEVE THIS IS TRUE.” In June 1945, American Vogue printed the photos under the title, “Believe It.”

In 1945, she traveled throughout Eastern and Central Europe, documenting the horrific aftermath of the war on mostly ordinary people, and had an eye for the detail of combat that her male counterparts often overlooked.

As Meredith Herndon wrote for The Smithsonian, “Miller’s eye for Surrealist elements resulted in haunting photos that juxtaposed images of ordinary beauty with violence and destruction.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

After the warLee married Roland Penrose in 1947, and gave birth to their son Antony at the age of forty. The family moved out of London to Farleys, a farm in the East Sussex countryside.

She continued to cover fashion, art, and celebrity culture for Vogue, and Farleys became known as a gathering place for the Surrealists. Many of Lee’s more intimate (and now iconic) photographs, of friends including Man Ray, Picasso, Eileen Agar, Dorothea Tanning and Max Ernst, were taken here.

Sadly, she suffered from severe (and at that time undiagnosed) post-traumatic stress disorder, which manifested in alcoholism and depression, and never spoke of her war work to her son, Antony.

In the early 1950s, Lee moved away from professional photography. Her final tongue-in-cheek piece for Vogue, “Working Guests” (1953), showed major art world figures (such as Alfred H. Barr, Jr., then the director of the Museum of Modern Art in NYC) feeding the pigs at Farleys.

Last years

In the last two decades of her life, Lee managed what her son would later call “the most astonishing achievement of her whole career … self-recovery … somehow she found the strength to get her drinking under control.”

A large part of this recovery came through cooking. Lee had given up photography, but she still longed for a creative outlet, and sent herself to the Cordon Bleu cookery school in Paris for six months.

Cooking, her son wrote, was “a kind of displacement activity for the demons that must have been rushing around inside her head all the time.” She became an award-winning cook, known for her Surrealism-inspired dishes such as green chicken and blue fish.

Lee died at Farleys in July 1977 of cancer at the age of seventy.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Legacy: Redefining femininityAfter Lee Millers’s death, Antony and his wife discovered some sixty thousand negatives and twenty thousand photographic prints, along with contact sheets, writings, and documents, all boxed up in the attic at Farleys.

From the 1980s, Antony worked to archive and promote her photographic work, which had been largely forgotten by the art world. Farleys is now the home of the Lee Miller Archive, along with a gallery which hosts rotating exhibitions.

Her work has also been shown in several major retrospectives, including at the Imperial War Museum and V&A Museum in London, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico.

Most recently, her war work has been the focus of the 2023 film Lee, produced by and starring Kate Winslet. Years of research went into making the film, along with a great deal of collaboration with Antony, and Kate Winslet reportedly spent days in the archives at Farleys.

According to Antony, “Other attempts to make a feature film about Lee had failed in the past, but this one succeeded…it owes much of its force and integrity to being a film about a women made by women.” On Lee, Kate Winslet said, “I think we live in a time when femininity is starting to mean something new, but Lee was already redefining femininity as resilience and power and courage and tenacity.”

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Lee Miller’s work

Women at War: The National WWII Museum Photographer Lee Miller’s Second World War Lee Miller ArchivesFurther reading:

Lee Miller: On Both Sides of the Camera by Carolyn Burke (2006)Lee Miller’s War: Beyond D-Day by Antony Penrose (2020)The Lives of Lee Miller by Antony Penrose (2021)Lee Miller: Fashion in Wartime Britain by Robin Muir and Amber Butchart(Lee Miller Archives Publishing, 2021)Lee Miller: Photographs by Antony Penrose and Kate Winslet (2023)Lee Miller Man Ray: Fashion, Love, War by Victoria Noel-Johnson (2023)Lee Miller: The True Story (Sky Original – Kate Winslet and Antony Penrose

discussing the film Lee) on YouTube

The post The Many Lives of Lee Miller, Photographer & War Correspondent appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 2, 2024

James Weldon Johnson’s Analysis of Phillis Wheatley’s Poetry