Nava Atlas's Blog, page 5

January 31, 2025

They wrote bestsellers and/or future classics before age 25

To write a great novel (or even a decent one), it seems that a writer should have a certain amount of life experience. But that’s not always the case — not in the past, and not in the present. Following are seven novels written when their authors were precocious young women — some still in their teens.

Some have become iconic classics; others sold in the millions are forgotten bestsellers.

So, what of it? Maybe the point is that if you have a story inside of you, find a way to tell it no matter what your age — tender through advanced. It may not become a classic or a bestseller or even be published, but at least will be something to build on.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Mary Shelley: Frankenstein, 1818

In the throes of her tumultuous, tragic, and romantic youth, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797 – 1851) created Frankenstein, one of the most memorable and influential novels of all time. Mary wasn’t yet twenty-one at the time.When she met Percy Bysshe Shelley, the romantic poet, she was around sixteen. Their fateful liaison would alter the course of her life. In the summer of 1814, seventeen-year-old Mary eloped to Italy with the already-married Shelley, who left his distraught, pregnant wife behind.

In the summer of 1816, Mary and Percy rented a villa not far from Lord Byron’s on Lake Geneva. On the night of a thunderstorm (yes, the classic “dark and stormy night”), it was proposed that each of the group write a supernatural tale.

Frankenstein was first published anonymously, but eventually the author’s identity was revealed and subsequent editions bore her name. In the preface to the 1831 edition, Mary tells the story of how she came to write her masterpiece. Here in her own words is the story of how it came to pass that a sheltered young woman from England came to write one of the most haunting tales of all time, with a creature that continues to grip the imagination.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Miles Franklin: My Brilliant Career, 1901

My Brilliant Career was Miles Franklin‘s first novel. Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin (1879 – 1954) went on to become one of the most prominent Australian authors of the first half of the 20th century.

Franklin wrote this novel while still in her teens, and it was published before she turned twenty-one. My Brilliant Career tells the story of Sybylla Melvyn, a high-strung, imaginative girl from the Australian countryside. When her parents fall on hard times, they send her to live with her grandmother in another part of the country.

Convinced that she’s ugly and useless, Sybilla is surprised when Harold Beecham, a wealthy young man, courts her and proposes marriage. Sybilla knows that she is “not a valuable article in the marriage market,” but “despises the slavery which respectable marriage will bring.” She will never “perpetrate matrimony,” will never be a “participant in that ‘degradation’” — these are astonishing words from the pen of a teen who, like her heroine, grew up in the outback.

Sybilla must navigate the narrow choices available to women of her time and place, and her desire to be independent. The 1979 film adaptation starring Judy Davis and Sam Neill was lovely as well, and quite true to the book.

. . . . . . . . . . .

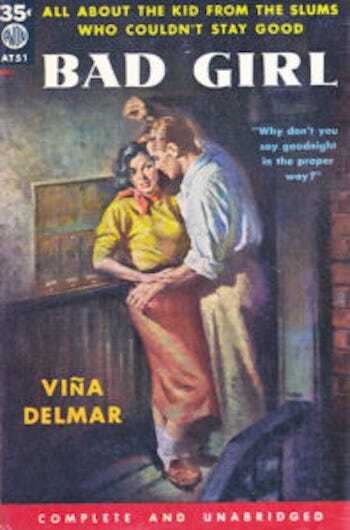

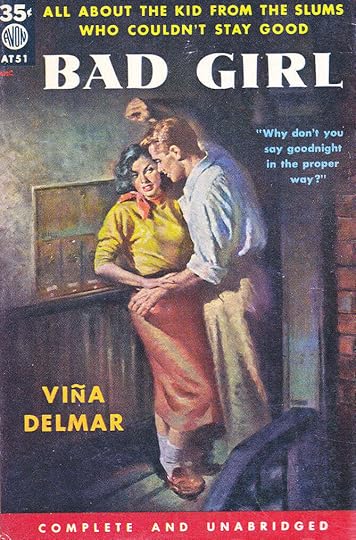

Viña Delmar: Bad Girl, 1928

Despite its provocative title, the forgotten bestselling 1928 novel, Bad Girl by Viña Delmar, wasn’t all that. Delmar, just twenty-three when it was published, was already married and the mother of a four-year-old son. That in itself wasn’t so unusual at the time, but not emblematic of experience-seeking urban women of the Jazz Age.

In Bad Girl, Dorothy, or “Dot,” as she’s called, has one instance of premarital sex, marries the guy (not a bad sort, but none too bright), and after a respectable period of time, becomes pregnant. She seriously considers ending the pregnancy, but goes ahead with it. Dot’s pregnancy and childbirth occupy much of the novel. The cover of a later edition (above) sensationalizes the story, as was typical of pulp novels.

There’s nothing scandalous about this middling novel, but the realities of a young wife’s pregnancy and her experiences in a birthing hospital were enough to grab the attention of The New England Watch and Ward Society. This organization, whose mission was censorship of books and the performing arts gave rise to the phenomenon of “Banned in Boston.”

Publishers welcomed their books being “Banned in Boston” — the controversy boosted book sales, as it did for Bad Girl. Despite having been a big bestseller, copies are hard to come by; I got mine on Ebay. I needed to read it for a project I’m working on, but wouldn’t necessarily recommend it. Still, it’s an interesting document of its era, and the basis of the well-regarded 1931 film of the same name. Here’s a 1928 interview with Viña Delmar.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Daphne du Maurier: The Loving Spirit, 1931

Not as well known as Daphne du Maurier’s more iconic works like Rebecca and My Cousin Rachel (among many other thrilling tales), The Loving Spirit was her first novel. Twenty-four at the time it was published, it launched what would become a stellar career.

Beginning in the early 1800s, The Loving Spirit tells the story of the Coombes family and is mainly set in Cornwall, a part of England in which the author spent much of her life. Janet Coombes marries her cousin, Thomas Coombes, a shipbuilder. The novel follows the adventures and trials of this family for four generations.

A modern reprint of this novel rightly described it as having “established du Maurier’s reputation and style with an inimitable blend of romance, history, and adventure.” Readers familiar with du Maurier’s later, and more famous works, have been delighted to discover her first novel. More about The Loving Spirit.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Carson McCullers: The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, 1940

Carson McCullers (1917–1967) was twenty-three when The Heart is a Lonely Hunter was published. While her novels, novellas, and short stories have retained a prominent place in the American canon, Lonely Hunter has arguably remained her best-remembered. This selection of quotes from The Heart of a Lonely Hunter sample the tone and flavor of the narrative.

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter made McCullers an overnight literary celebrity. She described herself as “much too young to understand what happened to me or the responsibility it entailed.” Readers and critics considered it an epic achievement and marveled that one so young had such a grasp of human nature. From a 1940 review:

“The characters move around Singer, a man of mystical understanding, in an intricate dance of hope and despair: Mick, and adolescent ardently longing to express herself in music; Jake Blount, a wild, blundering reformer; Dr. Copeland, the African American patriarch. Their appeal to Singer is the appeal of all humanity to a silent, cryptic universe.”

Reviewers felt that McCullers had captured America’s racial and economic divides simply and dramatically. Richard Wright, reviewing the novel in 1940, wrote:

“To me the most impressive aspect of The Heart is a Lonely Hunter is the astonishing humanity that enables a white writer, for the first time in Southern fiction, to handle African-American characters with as much ease and justice as those of her own race.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Kathleen Winsor: Forever Amber, 1944

Forever Amber by Kathleen Winsor is the sprawling story of Amber St. Clair, a beauty who climbs the class ranks of Restoration-era England. Twenty-five when the novel was published, Winsor had devoted more than five years to its nearly 1,000 pages.

Amber’s fictional narrative is interwoven with true historic facts of the English Restoration. On her nearly 1,000-page path to becoming the mistress of Charles II, Amber leaves a trail of scandal in her wake — theft, multiple husbands and lovers, and lots of sexual escapades (though none graphically described).

Forever Amber scandalized and enthralled. Fourteen U.S. states and all of Australia, banned the book upon its release, citing obscenity. It went to costly trials in the U.S.; Winsor and her publisher stood by her work and eventually prevailed in court. The notoriety trials didn’t hurt its popularity — quite the opposite.

Winsor made a fortune from Forever Amber and went on to write a few more novels, though none achieved its level of sales or notoriety. One reviewer wrote that Amber made Scarlett O’Hara look like a kindergarten teacher.

Forever Amber (which took me months to listen to) fell out of print, but is available in a “rediscovered classics” edition (with the cover shown above). It has been called a “bodice ripper,” it is not. Though it does take a bit of stamina to read, in my humble opinion, it doesn’t belong in the literary trash heap.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Françoise Sagan: Bonjour Tristesse, 1954

Bonjour Tristesse by Françoise Sagan is the story of Cecile, an amoral seventeen-year-old, who goes on vacation to the south of France with her father, Raymond. Sagan was eighteen when it was published and immediately became the epitome of an enfant terrible.

The title Bonjour Tristesse, meaning “hello sadness” in English, comes from a line in the poem “À Peine Défigurée” by Paul Éluard. The poem describes the familiarity of sadness that reappears in waves.

Bonjour Tristesse is a novel of romantic intrigue gone awry. The tangled web of romance and expressions of sexuality earned the book plenty of backlash, but it also solidified Sagan’s position as part of the rebellious post-war youth generation. Here’s a contemporary review of Bonjour Tristesse.

Fast-living and reckless all her life, Sagan nevertheless went on to become one of France’s most prolific and notable 20th-century writers.

More recent young women authors …

Writers in their teens and twenties are still producing the novels, maybe more then ever before. Here are a few recent titles, not including those written by enterprising self-publishers who build their readership on social media (especially TikTok):

S.E. Hinton was in high school when she wrote the now-classic YA novel of disaffected youth, The Outsiders (1967).

Angie Thomas wrote The Hate U Give (2017) while she was in high school and was twenty-one when it was published. A YA novel intended to shed light on the Black Lives Matter movement and the issue of police brutality, it was adapted to a highly acclaimed film that came out the following year.

Kody Keplinger was seventeen when she wrote The Duff (2010), a YA romance that stirred up some controversy. Though she has written several YA novels since, The Duff remains her best known.

Helen Oyeyemi was eighteen when The Icarus Girl (2005), a story of a girl with a Nigerian Mother and English father, was published to much acclaim. She has since published seven more novels and two plays.

Flavia Bujor (French-Romanian) takes the prize for youth here — she wrote the children’s story, The Prophecy of the Stones (2004) when she was thirteen. Though the reviews for the American edition were quite mixed, it was translated into twenty-three languages.

The post They wrote bestsellers and/or future classics before age 25 appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 28, 2025

Reuben Sachs by Amy Levy (1888) – an overview

Amy Levy (1861 – 1889), British novelist and proto-feminist essayist, lived the life of the “New Woman” with a circle of literary and lesbian friends, especially her probable lover Vernon Lee. The wealthy, fictional Sachs family in 19th-century London is the subject of Reuben Sachs (1888), arguably Levy’s best-known work.

Levy’s novel The Romance of a Shop (also published in 1888), is a “New Woman” novel about four sisters trying to make it in business.

In 1886, Levy had published “The Jew in Fiction,” in the British Jewish Chronicle. She said that no novelist so far had succeeded in “grappling in its entirety with the complex problems of Jewish life and Jewish character. The Jew, as we know him today … has been found worthy of none but the most superficial observation.”

The Sachs family lives in the most prestigious parts of London, England (Levy’s parents lived in Bloomsbury). The Sachs are “a family of Portuguese merchants, the vieille noblesse of the Jewish community.”

In the Sachses’ London Jewish community, “with its innumerable trivial class differences, its sets within sets, its fine-drawn distinctions of caste, utterly incomprehensible to an outsider, they held a good, though not the best position.”

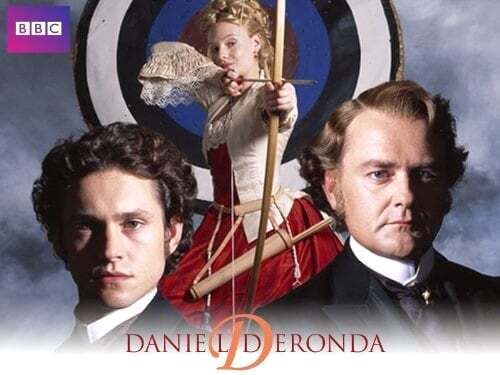

Levy’s short novel was written in response to what she considered the over-sentimental treatment of the Jewish characters and naïve, romantic view of Zionism in George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda (1876) with its “little group of enthusiasts, with their yearnings after the Holy Land.”

The story of Reuben Sachs as well as Judith Quixano

Despite the man’s name in the title of Levy’s Reuben Sachs, the novel is at least as much about Reuben’s cousin Judith Quixano. Judith’s patrician Portuguese ancestry is revealed in this description:

She was twenty-two years of age, in the very prime of her youth and beauty; a tall, regal-looking creature, with an exquisite dark head, features like those of a face cut on gem or cameo, and wonderful, lustrous, mournful eyes, entirely out of keeping with the accepted characteristics of their owner.

Judith (whose name references the Biblical story of Judith and Holofernes), who has been adopted by her aunt and uncle after her family lose their money, doesn’t have a financial inheritance of her own and, despite her good looks, she knows her adoptive parents will find it difficult to marry her off into another good Jewish family.

Judith is in love with Rueben and vice versa, although they are first cousins. It looks for a while as if they will marry, but Judith receives a marriage proposal from the non-Jewish, wealthy Bertie. She reluctantly accepts.

Material advantage; things that you could touch and see and talk about; that these were the only things which really mattered, had been the unspoken gospel of her life.

Now and then you allowed yourself the luxury of a fine sentiment in speech, but when it came to the point, to take the best that you could get for yourself was the only course open to a person of sense.

The push, the struggle, the hunger and greed of her world rose vividly before her. Wealth, power, success—a flaunting success for all men to see; had she not believed in these things as the most desirable on earth? Had she not always wished them to fall to the lot of the person dearest to her? Did she not believe in them still? Was she not doing her best to secure them for herself?

Judith regrets her decision almost immediately and wishes she had held out for Reuben. Then she hears that Rueben has died. The novel ends on a low note, with Judith’s dark thoughts.

It seemed to her, as she sat there in the fading light, that this is the bitter lesson of existence: that the sacred serves only to teach the full meaning of sacrilege; the beautiful of the hideous; modesty of outrage; joy of sorrow; life of death.

. . . . . . . . .

Amy Levy

. . . . . . . . . . .

A commercial success; criticized by the British Jewish pressAlthough it was a commercial success on both sides of the Atlantic, the British Jewish press hated Reuben Sachs, with its merciless portrayal of such shallow, unsympathetic characters. Jewish World said of Levy: “She apparently delights in the task of persuading the general public that her own kith and kin are the most hideous types of vulgarity.”

The Jewish Chronicle didn’t even review it, despite having published Levy’s earlier essay, but referred to it as being “intentionally offensive.”

The year after Reuben Sachs appeared, and soon after Levy’s death, the future Zionist campaigner Israel Zangwill, who coined the phrase “melting pot” in the title of a play, was commissioned by the Jewish Publication Society of America to write Children of the Ghetto, concerning a group of characters in the Jewish East End of London.

In the novel, Esther Ansell, many of whose views seem to echo Zangwill’s own, writes a novel, Mordecai Josephs, under a male pseudonym; no one knows she is the author; her novel seems to be based on Reuben Sachs. Everyone in Esther’s set hates the book and the way it betrays the mercenary and unspiritual bourgeois Jewish inhabitants of London, exactly the criticism the Jewish press had of Reuben Sachs.

Levy took her own life at the age of twenty-seven and became the first Jewish woman to be cremated in England; Oscar Wilde, who had published her stories in his Woman’s World, wrote an obituary for her.

. . . . . . . . .

Excerpted from A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth ©2022. Reprinted by permission.

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture: Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth-Century Literary Eroticism; Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938; High Collars & Monocles: 1920s Novels by British Female Couples; and A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young Adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

The post Reuben Sachs by Amy Levy (1888) – an overview appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 23, 2025

Radio Days: Trailblazing Women Journalists on the Airwaves

Starting in the 1920s, trailblazing American female radio broadcasters used their voices to open their fellow citizen’s eyes — or more accurately ears — to news of the wider world.

Historically, women had to fight like crazy to participate in every form of journalism. Though women faced less resistance in the early days of radio, they still had to fight for the right to report hard news.

Radio started crackling its way into American homes in the early 1920s. The airwaves expanded the way news and entertainment reached people. Stations sprang up in cities everywhere, exciting listeners with sounds coming out of a strange little box. Radio came on the scene several years even before the first “talkie” movie (1927), so it truly seemed like magic.

You might think of early radio as an old-fashioned form of podcasting. After all, podcasts are basically radio shows, except they’re distributed on the internet. For people who were lonely and isolated (especially during the Great Depression), radio helped them feel more connected to what was going on in the country and the world.

The industry welcomed women broadcasters because they were good for business. In the 1920s, women spent eighty percent of American income (though they certainly weren’t earning that share), so advertisers loved programs by and for the ladies.

In turn, this opened up other jobs in radio: research, publicity, advertising, talent search, secretarial, and more. A good number of women became executives, too.

Early radio programs were filled with lots of fluff, soap operas, and “women’s topic” programs aimed at housewives. But there was also plenty of serious journalism on the air. It wasn’t all smooth sailing for female journalists, who were sometimes told that their voices didn’t have as much authority as men’s. But a good number of women broke through to bring the important news of their day to the airwaves. Here are three of them.

. . . . . . . . . .

Dorothy Thompson

Dorothy Thompson advocates for repeal of Neutrality Act, 1939

Photo by Harris & Ewing, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Dorothy Thompson (1893 – 1961) used her charm, wit, sense of adventure, and strong work ethic to create an incredibly varied career in journalism. She started out by promoting the suffrage movement.

After women won the right to vote in 1920, she moved to Europe and became one of America’s first foreign correspondents. Based in Berlin, she reported from across the continent and at the same time enjoyed a fabulous social life. Her circle of friends included many writers and artists that we still remember today.

By the 1930s, Dorothy was one of the most trusted American journalists. She never sugar-coated the truth, and because she warned so loudly against the rise of fascism, she was thrown out of Germany in 1933.

As a news commentator for NBC radio in the 1930s, Dorothy’s show, “On the Record” was heard by millions. When Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939, legend has it that Dorothy stayed on the air for fifteen days and nights in a row (it’s not clear what she did about sleep!). The June 12, 1939 issue of Time magazine featured her on the cover, speaking into an NBC radio microphone.

“Peace has to be created in order to be maintained. It will never be achieved by passivity and quietism.” That’s just one of the countless pearls of wisdom on the strands of radio pioneer Dorothy Thompson’s life.

Dorothy Thompson’s life and work inspired a 1942 film, Woman of the Year. Katherine Hepburn plays Tess Harding, a character based on Dorothy. It also became a Broadway musical, with Lauren Bacall as Tess.

Dorothy Thompson was considered the most influential American woman, second only to first lady Eleanor Roosevelt. With all she accomplished, and being immortalized in a movie and a musical, isn’t it amazing that few people today have heard of her?

. . . . . . . . . .

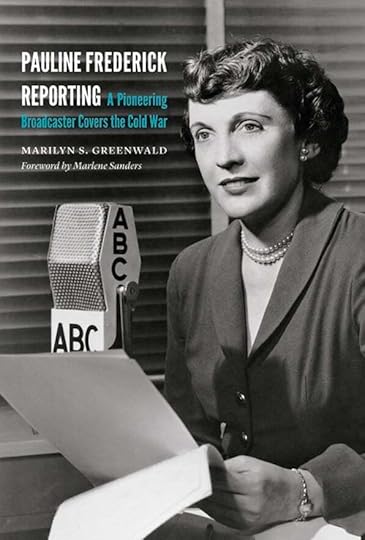

Pauline Frederick

Pauline Frederick (1908 – 1990) was one of the journalists who was told that “a woman’s voice doesn’t carry authority” when she first tried breaking into broadcast news. After doors had been opened to women in radio, after World War II, they started to close. Pauline pried them open, over and over again.

Pauline couldn’t convince any radio network to hire her. That frustrated her because as a print journalist she’d covered international news, including the Nuremberg trials. Finally, she freelanced for ABC radio, where she was assigned to the kind of women’s topics she dreaded. One of them was “How to Get a Husband.” Pauline regretted it, saying, “I don’t think I learned anything from it, and I don’t think the audience did either.”

Pauline persisted and finally got to report on news stories. She became the first female journalist to broadcast from China in the late 1940s and followed that with reporting from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

After she covered the first televised political convention in 1948, ABC hired her to do a weekday news program called Pauline Frederick Reports. That made her the first woman news commentator on TV. She was also the first woman to moderate a televised presidential debate (1976).

Toward the end of her career, Pauline Frederick returned to her passion for radio. Now one of the stars of broadcast news, she no longer had to struggle for the chance to get on the air. She worked on National Public Radio for five years before retiring in 1980.

. . . . . . . . . .

Kathryn Cochran Cravens

[Photo: Kathryn Cochran Cravens, 1938. Image available online

and used in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107.]

Kathryn Cochran Cravens (1899 – 1991) started out as an actress in stock theater companies and silent films. Needing more work during the Depression, she found a job in radio. Food, fashion, health, children, and saving money were popular topics, so KMOX in St. Louis hired her to do a broadcast called “Let’s Compare Notes.” It went on air in 1933.

But Kathryn soon grew bored and noticed that there weren’t any women hosting news programs. She convinced the station to let her do a show called “News Through a Woman’s Eyes.” That made her the first-ever female radio news broadcaster. With her acting background, she brought wit and drama to the program. It was such a success that CBS swooped in and lured her to New York City.

By 1936 she had two million listeners and was making a thousand dollars a week — a fortune at the time. And getting more than 3,000 pieces of fan mail every week proved that she was a big hit in the big city!

With every passing year, there was more competition for Kathryn as a female radio news broadcaster. Having blazed the trail, she was no longer a novelty. In 1938, CBS dropped her program. But her experiences sharpened her skills as a journalist, and she became a radio war correspondent during World War II — another first for women.

You may also enjoy …

8 Female Journalists of the World War II Era Ladies of the Black Press 4 Trailblazing Femail PhotojournalistsThe post Radio Days: Trailblazing Women Journalists on the Airwaves appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 17, 2025

Belle da Costa Greene: The Woman Behind The Personal Librarian

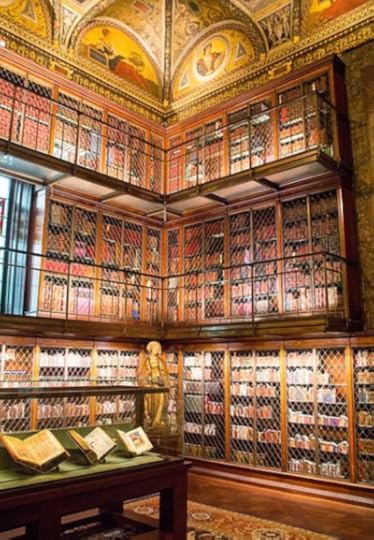

In the 2021 historical novel The Personal Librarian, authors Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray illuminate the story of Belle da Costa Greene, private librarian to financial mogul J.P. Morgan. Her expertise and passion were foundational to the beginnings of the Morgan Library and Museum, a cultural gem that continues to thrive in New York City.

This overview of The Personal Librarian novel and its real-life subject is reprinted from the website of N.J. Mastro, with permission. Photo at right is from The Morgan Library & Museum.

The Personal Librarian (2021) opens in 1905. After amassing his fortune, J.P. Morgan has set out to build the finest personal library in the world. In the novel, J.P. casts an imposing figure, as he did in real life. Imagine Rich Uncle Pennybags from the board game, Monopoly, the man on whom the caricature is based.

The Personal Librarian — an overview

Upon the recommendation of his nephew Junius Morgan, J.P. hires Belle da Costa Greene to purchase and curate his growing collection of rare books, manuscripts, book-related artifacts, and artwork. At the time, Belle was working as a librarian at Princeton, a white male-only university. Junius discovered Belle’s talent during his frequent visits to Princeton’s rare book collection. Her exceptional knowledge impressed him, as did her witty, animated personality.

Belle dazzles her new employer from the start. Because a great deal of business occurs in social settings as much as at auctions and by private arrangement, J.P. introduces her to New York society, where she makes an indelible impression. Soon she is traveling the world searching for the rarest of books, the most exquisite artwork money can buy, and antiquities few people have ever seen.

A woman earning such a prestigious position as librarian to one of America’s wealthiest individuals was alone a stunning achievement. Women simply didn’t enjoy professional positions of that magnitude; they didn’t even have the vote yet. That Belle was Black made her appointment even more remarkable. Belle had light skin color, enabling her to pass through life presenting herself as a white woman.

Throughout what appeared a charming, glamorous existence, Belle is forced to carry the secret of her true identity. If discovered, she would be fired. Not only would this destroy her career as a librarian, it would also take away her livelihood. Besides supporting herself, she was the breadwinner for her mother and siblings, to whom she provided food, clothing, shelter, and education.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Belle’s story in The Personal Librarian is poignant, engaging, and instructive. Readers discover Belle while the authors also bring to life on the page two unique worlds, that of rare books and fine art. The main learning for me, however, was the path of Black individuals who passed as white in this era.

Given how harshly Blacks were treated at the time, it wasn’t unusual for individuals with light skin color to elect to pass as white. One can only imagine the heartache that must have accompanied their choice. Belle’s story demonstrates this as she navigates her feelings and those of her family, including dealing with relatives who didn’t approve of her decision or that of her mother’s to live as white women.

Who was the real Belle da Costa Greene?Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray appear to have done an exceptional job of staying true to Belle’s actual story. The novel closely follows her life’s chronology.

Belle da Costa Greene was born Belle Marion Greener in 1883 in Washington, DC. Prior to her birth, her father was the first Black graduate of Harvard and spent time as the first Black librarian at the University of South Carolina. Belle’s parents separated when she was an adolescent. While Belle and the rest of her family remained in Washington, D.C., her father went on to pursue what eventually turned out to be a distinguished career in racial justice in other major U.S. cities. Belle only knew him from afar.

Belle’s mother and father, both of mixed race, had light skin, as did their children. Seeing the difficult road ahead for Black people in a segregated, racist world, Belle, along with her mother and siblings, changed their surname to Greene (dropping the “r”) to disassociate themselves from her father, then fabricated a new ancestry by describing themselves as Americans of Portuguese descent. Belle further altered her name by adding da Costa to the Greene name to reinforce her ruse of Portuguese heritage. Only one brother also adopted da Costa.

. . . . . . . . .

Photo: Morgan Library & Museum

. . . . . . . . .

Belle didn’t have the resources to attend college and went directly from high school to her job at Princeton. There her intellect and interest in rare collections set her apart, drawing the attention of Junius Morgan. She began her job as J.P.’s librarian in 1905 and stayed in that position until his death in 1913.

During her tenure as J.P.’s librarian, Belle did indeed take New York by storm. She became a regular at posh dinners and parties where J.P. introduced her to America’s wealthiest class. Belle had a flair for fashion. Stylish and beautiful, she wasn’t afraid to make herself visible — daring, essentially, to hide in plain sight.

Newspapers regularly featured her. One article in the Boston Globe in 1916 wrote, “it is rather gratifying to feminists to reflect that no near-sighted and anemic masculine scholar was Mr. Morgan’s helper in the long task of collecting the library treasure, but a woman, and a young and very pretty one at that.” [1]

Belle soon earned the reputation as the cleverest woman in the country due to her extensive knowledge regarding rare books and art. She knew what she wanted and how to get it by becoming a savvy purchaser, outsmarting her male counterparts, the dealers and collectors with whom she competed, often beating them at their own game.

In an interview on NPR, authors Benedict and Murray suggested that stereotypes likely contributed to Belle being able to pass as white. Whites commonly perceived Blacks as uneducated and incapable. Belle was anything but. She was educated, confident, and outspoken. She knew how to carry herself in the presence of white upper-class individuals like the Morgans, who ran in rich and complicated circles. [2]

J.P. Morgan died in 1913, passing his library down to his son, J.P. (Jack) Junior. Belle continued to serve as its librarian. In 1924, the collection had become too important to remain private. Jack Morgan gifted the private library to the public as a memorial to his father and named it the Pierpont Morgan Library. He also named Belle director.

Belle worked at the Pierpont Morgan Library for the next 24 years, expanding her reputation for scholarly research. She continued to travel extensively in Europe, attending auctions and collecting artifacts.

Belle never married. She is said, however, to have had a long-standing romantic relationship with Italian Renaissance art expert Bernard Berenson, which is explored fictitiously in The Personal Librarian. Belle and Berenson met in 1909 and enjoyed what the Morgan Library & Museum today refers to as a forty-year epistolary affair. Berenson was married, which may have prevented them from involvement beyond frequent letters and clandestine meetings. Here is Click here for a wonderfully informative video describing their relationship.

Belle retired in 1948. She died in 1950 in New York. It wasn’t until 1999 that J.P. Morgan biographer Jean Strouse discovered Belle’s birth certificate identifying her as “C” for colored. Little more is known, as Belle appears to have destroyed all her personal papers prior to her death.

Today the Pierpont Morgan Library is the Morgan Library & Museum, a major cultural institution. You can see images and hear about the library’s history in this visually rich short video.

Some may view Belle da Costa Greene as an imposter, a woman who pretended to be someone she was not. I believe the opposite. She decided who she was and who she wanted to be, in part doing what circumstances of her era required her to do.

By defying an arbitrary set of rules that were wildly unjust, she didn’t just survive, she thrived. Today she stands as proof of how wrong those rules were and how each individual has a set of choices available to them. While those choices may vary, it is a person’s inner drive and spirit that ultimately prevails.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Morgan Library, photo by Mike Peel (mikepee.net)

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . . .

Note from Literary Ladies Guide: An exhibit, Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy, is on view at the Morgan from October 25, 2024 through May 4, 2025. From the museum’s website:

“The exhibition traces Greene’s storied life, from her roots in a predominantly Black community in Washington, D.C., to her distinguished career at the helm of one of the world’s great research libraries. Through extraordinary objects―from medieval manuscripts and rare printed books to archival records and portraits―the exhibition demonstrates the confidence and savvy Greene brought to her roles as librarian, scholar, curator, and cultural executive, and honor her enduring legacy.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

N.J. Mastro‘s debut novel, Solitary Walker: A Novel of Mary Wollstonecraft, biofiction about Wollstonecraft, the woman widely considered by historians to be the world’s first feminist, will be published in February 2025 by Black Rose Writing. She also writes Herstory Revisited, a blog which reviews biographical fiction about amazing women from history.

Further reading

Belle da Costa Green, the Morgan’s First Librarian and Director (The Morgan) Belle de Costa Greene: Library Director, Advocate, and Rare Books Expert (LOC) The Story of J.P. Morgan’s ‘Personal Librarian’ — and Why She Chose to Pass as White (NPR)Notes

[1] Belle de Costa Greene: library director, advocate, and rare books expert. Joanna Colclough. February 9, 2022. Library of Congress. Retrieved from LOC.

[2] The story of J.P. Morgan’s ‘personal librarian’ — and why she chose to pass as white. Karen Grigsby Bates. NPR. August 31, 2021. Retrieved from NPR.

The post Belle da Costa Greene: The Woman Behind The Personal Librarian appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 16, 2025

Should These Women Authors Be Cancelled?

In pondering whether certain classic women authors should or shouldn’t be cancelled for holding abhorrent views I’m not advocating for or against; just musing on this vexing question.

Recently, Lynne Weiss, a contributor to this site, asked me what I’m going to do about Alice Munro. Given the magnitude of Munro’s recent posthumous controversy, I told Lynne I’m not going to do anything. I never got around to reading anything by Munro, truth be told, so it will be easy for me to continue to ignore her.

Then, in the past week, I keep seeing news stories about a certain male author who is getting into more and more trouble More women are coming forward with allegations. I don’t want to say who it is, since he’s still living.

All of this has gotten me to thinking about other women authors who were found to hold abhorrent views (or whose views have become abhorrent to contemporary sensibilities). Should we stop reading them? Should certain things be overlooked if the author left this earth with more in the good column than the bad? Again, this is not for me to decide.

This list makes me vacillate. I could live without some of these writers; others, ouch! it would be tough to give up. It’s the old quandary of separating the art from the artist.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Little House on the (Controversial) Prairie

Thinking about this subject brings to mind something I shared on Literary Ladies’ Facebook page in 2017 when it was Laura Ingalls Wilder’s 150th birthday, an article in Smithsonian magazine, “The Little House on the Prairie was Built on Native American Land.” I simply shared it, I didn’t editorialize But FB page followers, dozens of them, pretty much freaked out and were mad both at me and at Smithsonian.

Here’s a screen shot sampling some of the comments (names and identities redacted):

Some of the comments was of the “she was a product of her time” variety. I wasn’t going to get further into the fray and I’m never one to tell people how or what to think but as an argument, that’s a weak one. Louisa May Alcott, for example, was also “a product of her time,” and she was a feminist and abolitionist.

But then, someone commented on the Substack iteration of this post and informed me that Louisa, who I thought was so sainted, expressed anti-Irish sentiment. Sigh, even Louisa May Alcott isn’t perfect.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Edith Wharton, Antisemite?

Edith Wharton (1862 – 1937) was a wealthy heiress and a product of New York high society, never wanting for anything — except perhaps happiness.

After divorcing Teddy Wharton in 1913, Edith moved to France, which was on the brink of entering World War I. Upon the outbreak of the war, she immediately plunged into relief work. Among her accomplishments were feeding and housing hundreds of child refugees, establishing hostels for other refugees; and assisting wounded soldiers and struggling families.

For her war relief efforts, Wharton received one of France’s highest honors, the Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. Yet for all her compassion for war refugees, wounded soldiers, and orphaned children, Edith Wharton made no secret of her antisemitism. It was manifested in some of the characters in her books and in her correspondence.

The Jewish Federation of the Berkshires in Great Barrington (a neighboring town of Lenox, home to the palatial home Edith built), co-sponsored an event with the Mount (in neighboring Lenox, MA, a few years ago, “Edith Wharton’s Anti-Semitism: A Consideration.”

It’s hard to square those two sides of her, which coexisted in one talented, energetic, and complicated woman.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, eugenicist?

This one is disappointing and surprising, given how progressive Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860 – 1935) in so many other ways. She’s best remembered for the long short story on the (mis)treatment of postpartum depression, The Yellow Wallpaper, a women’s studies staple.

She was also one of the leading activists in the late 19th and early 20th century American women’s movement, and her nonfiction works (notably Women and Economics) details how women’s lives are impacted by social and economic bias are still (sadly) relevant.

It’s jarring to learn about some of Charlotte’s views on race and immigration. Some of her views in published essays were incredibly racist. And she held rather nationalistic views for someone so dedicated to equality. She had harsh words at times for immigrants, for example, writing that they diluted the “reproductive purity” of Americans of British decent. She famously said of herself “I am an Anglo-Saxon before everything,” and has been labeled a “eugenics feminist.”

Dorothy Canfield Fisher, whose life and work overlapped with Gilman’s was quite popular the 20th century, has also come under scrutiny for her possible sympathies with eugenics.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Colonialism in Isak Dinesen’s Out of Africa

Out of Africa by Isak Dinesen (1885 – 1962; pen name of Danish writer Karen Blixen) is a 1937 memoir of her years in Africa, 1914 to 1931. She owned a 4,000-acre coffee plantation in the hills outside of Nairobi, Kenya. This memoir was made famous by the 1985 Oscar-winning film starring Meryl Streep as Dinesen and Robert Redford as her fickle lover, Denys Finch-Hatton.

No one disputes the literary merit of Out of Africa. But in recent years, it has been subject of harsh reconsideration through the lens of decolonization. A 2017 essay in Quartz Africa by Abdi Natif Dahir, “Celebrating Karen Blixen’s Out of Africa Shows Why White Savior Tropes Still Exist,” argues:

“Since the publication of Blixen’s book in 1937, she has remained an important—and lasting—fixture in the study of Kenya’s colonial history … Ultimately, Blixen draws a hierarchy of life in which Africans have no place, in which she is the interlocutor of both ‘native’ and nature, and where ‘white men fill in the mind of the Natives the place that is, in the mind of the white men, filled by the idea of God.’”

And her biography on Post Colonial Studies states:

“Criticism of her work frequently shifts from admiration of her form to outrage at her portrayal of Africans. Karen Blixen’s complicated life and work continue to be studied, debated, and questioned in light of both the colonial society she inhabited and the modern reality of a postcolonial world.”

I rewatched the film last year, and whether because of today’s more critical lens on colonialism (really, it’s terrible to romanticize it) or that it’s simply slow as molasses, it didn’t hold up at all for me.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Enid Blyton: Offensive in all possible ways

Enid Blyton isn’t quite as known and read in the U.S. as she is (or was) in her home country, England, where she was once a wildly popular children’s book writer. And apparently, in England’s colonies. Literary Ladies Guide contributor Melanie Kumar and her contemporaries were fans of Blyton’s adventurous tales growing up in India. As an adult, reconsidered her views on this writer. She writes:

“Quite often in life, the innocence and idealism of one’s childhood years are intruded upon by the realities and pragmatism of adult life. The author in question is Enid Blyton, who was called “a racist, sexist, homophobe and not a well-regarded writer,” by the members of the Royal Mint, who in 2019 blocked attempts to give her a commemorative coin.

When one is forced to reckon with the labeling of a favorite author of one’s childhood, there will necessarily need to be a dialogue with the past to find a balance with the present. The issue resurfaced when the UK-based charity, English Heritage, in the light of the Black Lives Matter movement, decided to update its website with information on Enid Blyton.

The website now states that Blyton’s work has been criticized during her lifetime and after, ‘for its racism, xenophobia, and literary merit.’ Read the rest of Melanie’s essay, “When the Past Clashes with the Present: Reminiscences of Enid Blyton.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Of course, many other brilliant creative artists and writers, male and female, were jerks (or worse) in their personal lives. Should we avert our eyes when passing Picasso’s paintings in practically every museum on the planet? Again, I’m not saying that the writers above should or shouldn’t be canceled or ignored. We all have the freedom to read or not read who we choose.

My final question is whether we judge female jerks more harshly than their male counterparts. Read the thoughtful reader comments on the Substack iteration of this post, and feel free to comment below as well. The consensus seems to be: don’t cancel, but it’s good to know the good, the bad, and the ugly when it comes to writers.

One final thought: I have no problem cancelling male authors who have done worse than hold abhorrent views and who have caused actual physical and psychological harm to others.

The post Should These Women Authors Be Cancelled? appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 13, 2025

Everything Is Copy: The Life and Writing of Nora Ephron

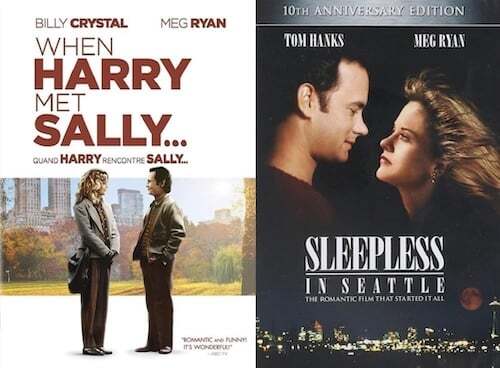

Nora Ephron (May 19, 1941–June 26, 2012) was an American screenwriter, film director, novelist, essayist, and journalist. She’s best remembered for her romantic comedy films, including When Harry Met Sally, Sleepless in Seattle, and You’ve Got Mail.

As a prolific essayist and journalist, her trademark skepticism, wit, and intimate writing style made her hugely successful, and she deserves to be remembered just as much for her prose as her screenplays.

Early life as part of a writing family

Nora was born in New York City in 1941 and had three younger sisters: Delia, Amy, and Hallie. Her parents, Henry and Phoebe, were both Broadway playwrights. At least two of their plays, Three’s A Family and Take Her, She’s Mine, were based on their family life.

When Nora was five years old, the family moved to Los Angeles. Henry and Phoebe Ephron were scriptwriters for a number of movies, including Desk Set, starring Spencer Tracy and Katherine Hepburn, and other classics.

All four sisters learned to read early, and dinnertime — served promptly every evening at six-thirty — was seen as an opportunity for them to learn the art of storytelling. Hallie later said that “the competition for airtime was Darwinian.” All four later became writers.

Nora’s parents regularly sent her to summer camp, where friends described her as a “natural leader.” At Camp Tocaloma in Arizona, she would entertain her friends by reading her mother’s letters from home aloud: “My friends…would laugh and listen, utterly rapt at the sophistication of it all.” These letters helped to later forge Nora’s distinctive journalistic writing style. Phoebe told her to write essays and columns as if she were mailing a letter, and then “tear off the salutation.”

The phrase “everything is copy,” which later became synonymous with Nora herself, was also attributed to her mother and this period of letter writing. Later, Nora explained what she believed her mother had meant by it: “When you slip on a banana peel, people laugh at you. But when you tell people you slipped on a banana peel, it’s your laugh, so you become the hero rather than the victim of the joke.”

Both Henry and Phoebe battled with alcoholism. Biographer Kristin Marguerite Doidge wrote that this was “…a lifelong journey [for Nora], understanding how someone you love and admire and look up to can also be falling apart, how to love someone who isn’t just one thing.” The complexities of love in all its forms were later a major theme in her work.

Choosing not to be a lady: Wellesley College

Nora graduated from Wellesley College with a degree in political science but felt that her experiences there didn’t prepare her for life in any meaningful way. It certainly did nothing to prepare her for life as a woman in the modern world.

Later, she wrote, “It always seemed so sad that a school that could have done so much for women put so much energy into the one area women should be educated out of … What do you think? What is your opinion? No one ever asked.”

Doidge wrote that Nora was “critical of her classmates at Wellesley for what she perceived as a lack of toughness, an unwillingness to fight for better conditions for women. I think she also found it silly that that was a thing at all. She had a complicated relationship with the concept of feminism.”

In 1996, when Nora was invited to give the commencement address at Wellesley, she told the students: “Whatever you choose, however many roads you travel, I hope that you choose not to be a lady. I hope you will find some way to break the rules and make a little trouble out there. And I also hope that you will choose to make some of that trouble on behalf of women.”

Achieving an ambition: New York City and journalism

After a stint working as an intern in the White House when John F. Kennedy was president (which she later wrote about in an essay, “Me and JFK: Now It Can Be Told”), she moved back to New York City, renting a series of small apartments and working in the typing pool at Newsweek.

She had plans to become a fully-fledged journalist, with dreams of following in the footsteps of Dorothy Parker, who she had first met as a child at one of her parents’ Hollywood parties. “All I wanted in this world,” she later wrote, “was to come up to New York and be Dorothy Parker. The funny lady. The only lady at the table.” This dream was soon punctured when she read more of Parker’s work, and found it to be “so embarrassing … Before one looked too hard at it, it was a lovely myth.”

She has always read constantly throughout her life, but particularly during this time: Doidge describes her curling up “on her new, wide-wale corduroy couch with a cup of hot tea and her dog-eared paperback copy of Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook.” Reading, for Nora, was not just for pleasure; it was also an education in the art of learning how to read people, how to interpret life onto the page, and how to make her writing her own.

Her chance came in 1962 when the newspapers went on strike, and every major paper in New York was shut down. Nora’s friend Victor Navasky, an editor, took the opportunity to print parodies of some of the papers and asked Nora if she would write a parody of a New York Post gossip column. Nora did it so well that it caught the attention of the Post’s publisher, Dorothy Schiff, who offered Nora her first job as a staff reporter. “If they can parody the Post,” she said, “they can write for it.”

Later, Nora wrote of her first weeks on the job: “The city room is dusty, dingy and dark. The desks are dilapidated and falling apart. It smells terrible. There aren’t enough phones … I am hired permanently. I have never been happier. I have achieved my life’s ambition, and I am twenty-two years old.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Everything is copy: essays and articlesIn 1970 Nora moved from the Post to Esquire, where she remained a writer until 1989. Her essays were hugely popular — her style (described by Rachel Syme in The New Yorker as “light, fizzy, precise”) and her sense of intimacy with readers made her a hit, even when her sharpness verged on cruelty.

This sharpness was characteristic of all of her writing, even her later screenplays: Meg Ryan, who worked with Nora on When Harry Met Sally, Sleepless in Seattle, and You’ve Got Mail, said: “Her allegiance to language was sometimes more than her allegiance to someone’s feelings.”

She wrote on diverse topics, universal and personal — politics, relationships, feminism, aging, and waxing. She recommended bikini waxes, but only if you were actually wearing a bikini. She implored the reader to employ the breathing exercises commonly taught in prenatal classes: “I recommend them highly, although not for childbirth, for which they are virtually useless.”

She also devoted entire essay to handbags, which she did not recommend in the slightest: “This is for women whose purses are a morass of loose TicTacs, solitary Advils, lipsticks without tops, Chapsticks of unknown vintage, little bits of tobacco even though there has been no smoking going on for at least ten years … This is for those of you who understand, in short, that your purse is, in some absolutely horrible way, you.”

Food was also a favorite topic. In the essay “Serial Monogamy: a Memoir” she scrutinized the “fancy” cooking of the 1960s, particularly her own fascination with the famous food writers of the time.

“We all began to cook in a wildly neurotic and competitive way,” she wrote. “We were looking for applause, we were constantly performing, we were desperate to be all things to all people. Was this the grand climax of the post–World War II domestic counterrevolution or the beginning of a pathological strain of feminist overreaching? No one knew. We were too busy slicing and dicing.”

Her essays were later collected into books, including Wallflower at the Orgy (1970), Crazy Salad (1975), and Scribble, Scribble (1978).

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Heartbreak and HeartburnNora married Dan Greenburg in the mid-1960s; they separated in 1974. She married Carl Bernstein two years later. She discovered that he was cheating on her with a mutual friend (Margaret Jay) while she was pregnant. Her first novel, Heartburn, is a thinly veiled account of their separation and subsequent divorce.

The protagonist, Rachel, is a food writer; recipes scattered throughout the narrative. Nora had longed for someone to include her original recipes in a cookbook but realized that “no one was ever going to put my recipes into a book, so I’d have to do it myself.”

The recipes in Heartburn include pears with lima beans, cheesecake, bacon hash, and key lime pie (which Rachel ultimately throws in her cheating husband’s face). Nora later wrote:

“The point wasn’t about the recipes. The point (I was starting to realize) was about putting it together. The point was about making people feel at home, about finding your own style, whatever it was, and committing to it. The point was about giving up neurosis where food was concerned. The point was about finding a way that food fit into your life.”

Heartburn was a bestseller, and Nora wrote the screenplay for the film adaption. Released in 1986, it starred Meryl Streep and Jack Nicholson, and was directed by Mike Nichols.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Success in screenwritingHeartburn wasn’t Nora’s first screenplay or film. She had started writing scripts in the early days after her divorce from Bernstein, when she was single, broke, and living with two young children in an apartment owned by her editor.

She discovered that scriptwriting allowed her to combine everything that she loved about her essay writing and journalism – observing people, dissecting them, understanding them – while also allowing her to stay in one place and work from home.

Her first film, Silkwood (1983), was co-written with Alice Arlen. It was based on the true story of Karen Silkwood, a union activist who died while investigating safety violations at a nuclear plant. Her big Hollywood breakthrough came in 1989, when she wrote the screenplay for When Harry Met Sally. The film was a huge hit, and Nora received a BAFTA for Best Original Screenplay and an Oscar nomination.

Nora made her directorial debut in 1992 with the film This is My Life, and also co-wrote the script with her sister Delia Ephron. Further hits included Sleepless in Seattle (1993), You’ve Got Mail (1998; also co-written with Delia), and Julie and Julia (2009). Rachel Syme has described her films as “physically chaste but rhetorically hot … the idea of swooning over someone’s syntax so dramatically that you change your life appears again and again in Ephron’s work.”

. . . . . . . . .

Nicholas Pileggi & Nora Ephron in 2010

photo by David Shankbone courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . .<

Considering the Alternative and last projectsNora’s third and final marriage was to Nicholas Pileggi (author of Goodfellas and Casino) in 1987. They remained married until her death.

She continued to write for theatre, and published two further collections of essays, I Feel Bad About My Neck (2006) and I Remember Nothing (2010). I Feel Bad About My Neck reached the top of the New York Times bestseller list for nonfiction.

In one essay in that collection, “Consider the Alternative,” Nora turned a wry, poignant eye to the topic of aging, writing that “… the honest truth is that it’s sad to be over sixty. The long shadows are everywhere … A miasma of melancholy hangs there, forcing you to deal with the fact that your life, however happy and successful, has been full of disappointments and mistakes … There are, in short, regrets.”

She was diagnosed with myelodysplasia in 2006 but chose not to reveal her diagnosis to anyone beyond her immediate family. Her death in 2012 at the age of seventy-one was caused by pneumonia, a complication of leukemia.

The legacy of Nora Ephron

Beyond the obvious legacy of her films – still big hits and hugely popular – Nora’s essays and other writings continue to inspire countless readers, women in particular. In her new introduction to I Feel Bad About My Neck, Dolly Alderton said that through her writing, Nora was “the best friend every woman longs for – shrewd, hilarious and utterly unimpeachable, equal parts Dorothy Parker, Coco Chanel and Mrs. Beeton.”

The Most of Nora Ephron — a collection of her newspaper columns, blog posts, speeches and other works — was published posthumously in 2013, and in 2016 her son, Jacob Bernstein, directed an HBO film of her life, titled Everything is Copy.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris.

More about Nora EphronBiography and criticism

Nora Ephron: A Life by Kristin Marguerite Doidge (2022)Nora Ephron At The Movies by Ilana Kaplan (2024)Books by Nora Ephron (selected)

Crazy Salad: Some Things About Women (1975)Scribble, Scribble: Notes on the Media (1978)Heartburn (1983)I Feel Bad About My Neck by Nora Ephron (2006)I Remember Nothing: and Other Reflections by Nora Ephron (2010)The Most of Nora Ephron by Nora Ephron (2013)Heartburn by Nora Ephron (year)Films and interviews

Nora Ephron’s Filmography Nora Ephron Interview (on Life Stories)The post Everything Is Copy: The Life and Writing of Nora Ephron appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 7, 2025

17 Poems by Helene Johnson, Poet of the Harlem Renaissance

Helene Johnson (1906 – 1995) was an American poet associated with the Harlem Renaissance. This selection of poems by Helene Johnson features those from the 1920s, the period in which as a young poet, she was most active.

She was just nineteen when her first published poem, “Trees at Night,” was published in Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life in 1925. A year later, this journal published six more of her poems.

Her poems also made an appearance in NAACP’s The Crisis and the first and only issue of Fire!!, Langston Hughes’ short-lived publication. As Helene grew aware of the economic and divide facing Black New Yorkers, she began to explore racial themes in her poetry.

Several scholars have made a case for a reconsideration of Helene’s poetry. Though she was a very private and self-described shy person, her poems are bold and innovative, bearing a unique voice.

In Notable Black American Women (1992) T. J. Bryan wrote: “Helene Johnson’s works are models for aspiring poets — especially for African American women poets who have long been led to believe that no tradition of achievement exists among Black American women in this genre prior to the 1960s … Helene Johnson is a transitional poet whose works of the 1920s and 1930s signal a striking out in new directions among Black American women poets, who began to abandon romantic themes and poetic conventions at this juncture.”

From Lehigh University’s Digital Anthology of African American Poetry: “Throughout the late 1920s, Johnson explored racial themes in a variety of ways in her poetry, including a number of ‘Harlem’-themed poems (“Sonnet to a Negro in Harlem” and “Bottled” being two representative examples). A number of her poems also used natural settings to powerful effect, including “A Southern Road.” Johnson’s poems often dramatize the tension between conservative morality and Christian restraints against the sensuous riot of the emerging African American youth culture of the 1920s (“Magalu”).

Following are the poems presented in this post. They’re from several sources that are all in the public domain, notably Caroling Dusk: An Anthology of Verse by Negro Poets, edited by Countee Cullen (1927); Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life. The Urban League; various issues);

Trees at NightAh My RaceNightMetamorphismFulfillmentThe RoadMagaluThe Little LoveFutilityLove in MidsummerA Southern RoadBottledSonnet to a Negro in HarlemPoemWhat Do I Care for Morning?Summer MaturesI Am Not ProudHelene Johnson’s legacy is encapsulated in this analysis of her life’s work University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy:

“Regardless of her fading presence in the Harlem Renaissance, Johnson’s work is being rediscovered and revived by several scholars today. Verner Mitchell, Nina Miller, and Maureen Honey have acknowledged Johnson’s inventiveness and said that poetry of this ability from of woman of Johnson’s time was unique.

Because she experienced much independence and sovereignty as a child and young adult, Johnson conveys in her poems an extremely powerful female perspective and image. Johnson is described as having been painfully shy while growing up. Her discretion is not displayed in her poetry, however, in which she speaks boldly about her race and her gender. Her 1925 poem, ‘My Race’ challenges the feminine themes of love and motherhood through bold and aggressive stances. Johnson, when writing about race, is brave and empowering.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Trees at NightSlim sentinels

Stretching lacy arms

About a slumberous moon;

Black quivering

Silhouettes;

Tremulous,

Stenciled on the petal

Of a bluebell;

Ink splattered

On a robin’s breast:

The jagged rent

Of mountains

Reflected in a

Still sleeping lake;

Fragile pinnacles

Of fairy castles;

Torn webs of shadows;

And

Printed ‘gainst the sky—

The trembling beauty

Of an urgent pine.

(Opportunity, May 1925)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Ah My RaceAh my race,

Hungry race,

Throbbing and young —

Ah, my race,

Wonder race,

Sobbing with song,

Ah, my race,

Careless in mirth

Ah, my veiled race,

Fumbling in birth.

(Opportunity, July 1925)

. . . . . . . . . . .

NightThe moon flung down the bower of her hair,

A sacred cloister while she knelt at prayer.

She crossed pale bosom, breathed a sad amen —

Then bound her hair about her head again.

(Opportunity, January 1926)

. . . . . . . . . . .

MetamorphismIs this the sea?

This calm emotionless bosom,

Serene as the heart of a converted Magdalene ––

Or this?

This lisping, lulling murmur of soft waters

Kissing a white beached shore with tremulous lips;

Blue rivulets of sky gurgling deliciously

O’er pale smooth-stones ––

This too?

This sudden birth of unrestrained splendour,

Tugging with turbulent force at Neptune’s leash;

This passionate abandon,

This strange tempestuous soliloquy of Nature,

All these –– the sea?

To climb a hill that hungers for the sky,

To dig my hands wrist deep in pregnant earth,

To watch a young bird, veering, learn to fly,

To give a still, stark poem shining birth.

. . . . . . . . . .

The RoadAh, little road all whirry in the breeze,

A leaping clay hill lost among the trees,

The bleeding note of rapture streaming thrush

Caught in a drowsy hush

And stretched out in a single singing line of dusky song.

Ah little road, brown as my race is brown,

Your trodden beauty like our trodden pride,

Dust of the dust, they must not bruise you down.

Rise to one brimming golden, spilling cry!

(Opportunity, July 1926)

. . . . . . . . . .

MagaluSummer comes. The ziczac hovers

‘Round the greedy-mouthed crocodile.

A vulture beats away a foolish jackal.

The flamingo is a dash of pink

Against dark green mangroves,

Her slender legs rivaling her slim neck.

The laughing lake gurgles, delicious music in its throat

And lulls to sleep the lazy lizard,

A nebulous being on a sun-scorched rock.

In such a place,

In this pulsing, riotous gasp of color,

I met Magalu, dark as a tree at night,

Eager-lipped, listening to a man with a white collar

And a small black book with a cross on it.

Oh, Magalu, come! Take my hand and I will read you poetry,

Chromatic words,

Seraphic symphonies,

Fill up your throat with laughter and your heart with song.

Do not let him lure you from your laughing waters,

Lulling lakes, lissome winds.

Would you sell the colors of your sunset and the fragrance

Of your flowers, and the passionate wonder of your forest

For a creed that will not let you dance?

(Opportunity, July 1926)

. . . . . . . . . .

The Little LoveA shy ear bared

For incipient kisses;

A secret shared

In laughter exquisite;

Soft finger tips,

While the night embraces,

Touch passionate colors

That morning erases

And when the Dawn wakens,

No attempt to recapture

Those swift fleeting hours of ecstatic rapture,

But hide the shy ear with a curl, my pet,

And that little secret,— forget.

(The Messenger, July 1926)

. . . . . . . . . .

FutilityIt is silly —

This waiting for love

In a parlor.

When love is singing up and down the alley

Without a collar.

(Opportunity, August 1926)

. . . . . . . . . .

Love in MidsummerAh love

Is like a throbbing wind,

A lullaby all crooning,

Ah love

Is like a summer sea’s soft breast.

Ah love’s

A sobbing violin

That naïve night is tuning,

Ah love

Is down from off the white moon’s nest.

(The Messenger, October 1926)

. . . . . . . . . .

A Southern RoadYolk-colored tongue

Parched beneath a burning sky,

A lazy little tune

Hummed up the crest of some

Soft sloping hill.

One streaming line of beauty

Flowering by a forest

Pregnant with tears.

A hidden nest for beauty

Idly flung my God

In one lonely lingering hour

Before the Sabbath.

A blue-fruited black gum,

Like a tall predella,

Bears a dangling figure,—

Sacrificial dower to the raff, Swinging alone,

A solemn, tortured shadow in the air.

(Fire!!, November 1926)

. . . . . . . . . .

BottledUpstairs on the third floor

Of the 135th Street library

In Harlem, I saw a little

Bottle of sand, brown sand

Just like the kids make pies

Out of down at the beach.

But the label said: “This

Sand was taken from the Sahara desert. ”

Imagine that! The Sahara desert!

Some bozo’s been all the way to Africa to get some sand.

And yesterday on Seventh Avenue

I saw a darky dressed fit to kill

In yellow gloves and swallow tail coat

And swirling a cane. And everyone

Was laughing at him. Me too,

At first, till I saw his face

When he stopped to hear a

Organ grinder grind out some jazz.

Boy! You should a seen that darky’s face!

It just shone. Gee, he was happy!

And he began to dance. No

Charleston or Black Bottom for him.

No sir. He danced just as dignified

And slow. No, not slow either.

Dignified and proud! You couldn’t

Call it slow, not with all the

Cuttin’ up he did. You would a died to see him.

The crowd kept yellin’ but he didn’t hear,

Just kept on dancin’ and twirlin’ that cane

And yellin’ out loud every once in a while.

I know the crowd thought he was coo-coo.

But say, I was where I could see his face,

And somehow, I could see him dancin’ in a jungle,

A real honest-to-cripe jungle, and he wouldn’t have on them

Trick clothes — those yaller shoes and yaller gloves

And swallow-tail coat. He wouldn’t have on nothing.

And he wouldn’t be carrying no cane.

He’d be carrying a spear with a sharp fine point

Like the bayonets we had “over there.”

And the end of it would be dipped in some kind of

Hoo-doo poison. And he’d be dancin’ black and naked and gleaming.

And he’d have rings in his ears and on his nose

And bracelets and necklaces of elephants’ teeth.

Gee, I bet he’d be beautiful then all right.

No one would laugh at him then, I bet.

Say! That man that took that sand from the Sahara desert

And put it in a little bottle on a shelf in the library,

That’s what they done to this shine, ain’t it? Bottled him.

Trick shoes, trick coat, trick cane, trick everything — all glass —

But inside —

Gee, that poor shine!

(Vanity Fair, May 1927, and Caroling Dusk, both 1927)

“Bottled” needs an introduction and context, without which it can be misconstrued. It was first published in 1927 in the May issue of Vanity Fair. and later the same year in the classic anthology Caroling Dusk

Katherine R. Lynes in Project Muse offers much insight into the story behind the poem:

“In ‘Bottled,’ Johnson puts authentic and inauthentic into dialogue when she puts an imagined African jungle into a poem set on the real streets of New York City. The speaker of the poem admires the (imagined) cultural adornments and proud dancing of a man in the streets of Harlem.

The speaker reports that he dances to jazz, American music that has some of its roots in Africa but is not in and of itself wholly African; she also imagines this man as he would be if he were in Africa. He functions as a cultural object in the poem, a cultural object with contested authenticities. Johnson’s use of a mixture of cultural tropes reveals her awareness of and attentiveness to theories of cultural relativism.”

Read the rest of this analysis at Project Muse.

. . . . . . . . . .

Sonnet to a Negro in HarlemYou are disdainful and magnificent—

Your perfect body and your pompous gait,

Your dark eyes flashing solemnly with hate,

Small wonder that you are incompetent

To imitate those whom you so despise—

Your shoulders towering high above the throng,

Your head thrown back in rich, barbaric song,

Palm trees and mangoes stretched before your eyes.

Let others toil and sweat for labor’s sake

And wring from grasping hands their need of gold.

Why urge ahead your supercilious feet?

Scorn will efface each footprint that you make.

I love your laughter arrogant and bold.

You are too splendid for this city street.

(Caroling Dusk, 1927)

. . . . . . . . . .

See also …

See also …

Renaissance Women: 13 Female Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance to Rediscover and Read

. . . . . . . . . . .

Little brown boy,

Slim, dark, big-eyed,

Crooning love songs to your banjo

Down at the Lafayerre —

Gee, boy, I love the way you hold your head,

High sort of and a bit to one side,

Like a prince, a jazz prince. And I love

Your eyes flashing, and your hands,

And your patent-leathered feet,

And your shoulders jerking the jig-wa.

And I love your teeth flashing,

And the way your hair shines in the spotlight

Like it was the real stuff.

Gee, brown boy, I loves you all over.

I’m glad I’m a jig. I’m glad I can

Understand your dancin’ and your

Singin’, and feel all the happiness

And joy and don’t care in you.

Gee, boy, when you sing, I can close my ears

And hear tom-toms just as plain.

Listen to me, will you, what do I know

About tom-toms? But I like the word, sort of,

Don’t you? It belongs to us.

Gee, boy, I love the way you hold your head,

And the way you sing, and dance,

And everything.

Say, I think you’re wonderful. You’re

Allright with me,

You are.

(Caroling Dusk, 1927)

. . . . . . . . . .

What Do I Care for MorningWhat do I care for morning,

For a shivering aspen tree,

For sun flowers and sumac

Opening greedily?

What do I care for morning,

For the glare of the rising sun,

For a sparrow’s noisy prating,

For another day begun?

Give me the beauty of evening,

The cool consummation of night,

And the moon like a love-sick lady,

Listless and wan and white.

Give me a little valley

Huddled beside a hill,

Like a monk in a monastery,

Safe and contented and still,

Give me the white road glistening,

A strand of the pale moon’s hair,

And the tall hemlocks towering

Dark as the moon is fair.

Oh what do I care for morning,

Naked and newly born—

Night is here, yielding and tender—

What do I care for dawn!

(Caroling Dusk, 1927)

. . . . . . . . . .

Summer MaturesSummer matures. Brilliant Scorpion

Appears. The Pelican’s thick pouch

Hangs heavily with perch and slugs.

The brilliant-bellied newt flashes

Its crimson crest in the white water.

In the lush meadow, by the river,

The yellow-freckled toad laughs

With a toothless gurgle at the white-necked stork

Standing asleep, and one red reedy leg.

And here Pan dreams of slim stalks clean for piping,

And of a naked nightingale gone mad with freedom.

Come. I shall weave a bed of reeds

And willow limbs and pale nightflowers.

I shall strip the roses of their petals,

And the white down from the swan’s neck.

Come, night is here. The air is drunk

With wild grape and sweet clover.

And by the secret fount of Aganippe

Euterpe sings of love. Ah, the woodland creatures,

The doves in pairs, the wild sow and her shoats,

The stag searching the forest for a mate,

Know more of love than you, my callous Phaon.

The young moon is a curved white scimitar

Pierced through the swooning night.

Sweet Phaon. With Sappho sleep like the stars at dawn.

This night was born for love my Phaon.

Come.

(Opportunity, July 1927; also Caroling Dusk, 1927)

. . . . . . . . . .

I Am Not ProudI am not proud that I am bold

Or proud that I am black.

Color was given to me as a gage

And boldness came with that.

(The Saturday Evening Quill, April 1929)

Further reading

“The Published Poems of Helene Johnson” by T.J. Bryan. (The Langston Hughes Review, Fall 1987, Volume 6, No. 2, pp. 11-21. Published by: Langston Hughes Society, Penn State University Press)

“Toward an Understanding of Helene Johnson’s Hybrid Modernist Poetics” by Robert Fillman. CLA Journal, Vol. 61, No. 1-2 (Sept. – Dec. 2017), pp. 45-64

The post 17 Poems by Helene Johnson, Poet of the Harlem Renaissance appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

16 Poems by Helene Johnson

Helene Johnson (1906 – 1995) was an American poet associated with the Harlem Renaissance. This selection of poems by Helene Johnson features those from the 1920s, the period in which as a young poet, she was most active.

She was just nineteen when her first published poem, “Trees at Night,” was published in Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life in 1925. A year later, this journal published six more of her poems.

Her poems also made an appearance in NAACP’s The Crisis and the first and only issue of Fire!!, Langston Hughes’ short-lived publication. As Helene grew aware of the economic and divide facing Black New Yorkers, she began to explore racial themes in her poetry.

Several scholars have made a case for a reconsideration of Helene’s poetry. Though she was a very private and self-described shy person, her poems are bold and innovative, bearing a unique voice.

In Notable Black American Women (1992) T. J. Bryan wrote: “Helene Johnson’s works are models for aspiring poets — especially for African American women poets who have long been led to believe that no tradition of achievement exists among Black American women in this genre prior to the 1960s … Helene Johnson is a transitional poet whose works of the 1920s and 1930s signal a striking out in new directions among Black American women poets, who began to abandon romantic themes and poetic conventions at this juncture.”

From Lehigh University’s Digital Anthology of African American Poetry: “Throughout the late 1920s, Johnson explored racial themes in a variety of ways in her poetry, including a number of ‘Harlem’-themed poems (“Sonnet to a Negro in Harlem” and “Bottled” being two representative examples). A number of her poems also used natural settings to powerful effect, including “A Southern Road.” Johnson’s poems often dramatize the tension between conservative morality and Christian restraints against the sensuous riot of the emerging African American youth culture of the 1920s (“Magalu”).

Following are the poems presented in this post. They’re from several sources that are all in the public domain, notably Caroling Dusk: An Anthology of Verse by Negro Poets, edited by Countee Cullen (1927); Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life. The Urban League; various issues);

Trees at NightAh My RaceNightMetamorphismFulfillmentThe RoadMagaluThe Little LoveFutilityLove in MidsummerA Southern RoadBottledSonnet to a Negro in HarlemPoemWhat Do I Care for Morning?Summer MaturesHelene Johnson’s legacy is encapsulated in this analysis of her life’s work University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy: