Nava Atlas's Blog, page 6

December 24, 2024

Ouida (Louise de la Ramée), English Victorian Novelist

Louise de la Ramée, (known by her pen name of Ouida; January 1, 1839 – January 25, 1908) was an English novelist of French extraction. Born in Bury St. Edmunds, England, her nom de plume was supposedly suggested by a young sister’s efforts to pronounce “Louise.”

The best-known of her many works are A Dog of Flanders, a children’s book that has been adapted to film numerous times, and Under the Flag. She wrote more than forty novels, plus many short stories and children’s books. She also contributed numerous articles and essays to magazines and journals.

Her novels dealt with all phases of European society, some of her themes being treated with cleverness and skill, often with cynical railing at the weaknesses of her characters.

Her early stories were extravagantly romantic, but she shed her passionate exuberance and became a stronger writer, though inclined to the reckless and tragic. For the last thirty years of her life she made her home in Italy, where scenes in many of her novels were set. (adapted from The New Student’s Reference Work, Chicago: F.E. Compton and Co., 1914)

The following has been adapted from De la Ramée, Marie Louise,” in Dictionary of National Biography, 1912 supplement, London: Smith, Elder, & Co. (1912) in 3 vols.

Ouida (1839 – 1908), born Marie Louise de la Ramée in Bury St. Edmunds, was the daughter of Louis Ramé and Susan Sutton. She owed her education to her father, a teacher of French whose intellectual power was exceptional. At an early age, she expanded her surname of Ramé into de la Ramée.

Though not a lot is known about her early life, a girlhood diary from April 1850 to May 1853 showcases her precocity, love of reading, and eagerness to learn. She visited Boulogne with her parents in 1850, and accompanied them to London in 1851 to see the Great Exhibition.

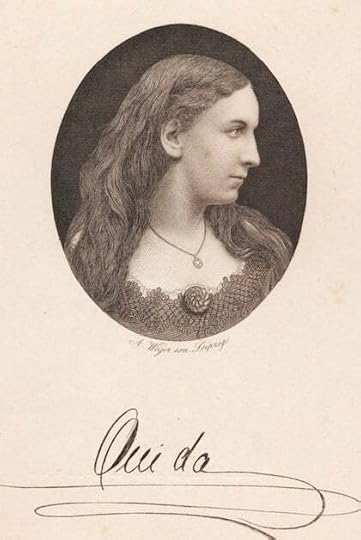

Slightly built, fair, with an oval face, she had large dark blue eyes and golden brown hair. A portrait in red chalk, drawn in September 1904 by Visconde Giorgio de Moraes Sarmento, was presented by the artist to the National Portrait Gallery, London, in 1908. He offered another drawing, also created in her declining years, to the Moyses Hall Museum, Bury St. Edmunds.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

The beginnings of a literary career

Ouida began her literary career under Harrison Ainsworth’s auspices, publishing a short story titled “Dashwood’s Drag or, the Derby and What Came of It” (1859) in the New Monthly Magazine.

Ainsworth, convinced of her ability, accepted and published by the end of 1860 seventeen tales by her, none of which she reprinted, although they brought her into notice. Like her later novels they dealt with dubious phases of military and fashionable life.

Her first long novel, Granville de Vigne, appeared in the same magazine in 1863. Tinsley published it in three volumes, changing the title with her consent to Held in Bondage. On the title page, Miss de la Ramée first adopted the pseudonym of “Ouida,” by which she was ever after known as a writer.

Strathmore followed in 1865, and Idalia, written when she was sixteen, in 1867. Strathmore was parodied as Strapmore! a romance by “Weeder” in Punch by Sir Francis Burnand in 1878. Ouida’s vogue was assisted by Lord Strangford’s attack on her novels in the Pall Mall Gazette.

An exceptionally prolific writer in several genres

Ouida’s books were constantly reprinted in cheap editions, and some were translated into French, or Italian, or Hungarian.

Many of her later essays in the Fortnightly Review, the Nineteenth Century, and the North American Review were republished in Views and Opinions (1895) and Critical Studies (1900). There she proclaimed her hostility to woman suffrage and vivisection, or proved her critical insight into English, French, and Italian literature. Her uncompleted last novel, Helianthus (1908), was published after her death.

An 1893 opera by G. A. à Beckett and H. A. Rudall was based on her novel Signa (1875). The light opera Muguette by Carré and Hartmann on Two Little Wooden Shoes. Plays based on Moths were produced at the Globe Theatre in March, 1883; as were those adapted from Under Two Flags, to much success.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Settling in ItalyIn 1874 Ouida settled permanently with her mother in Florence, and pursued her work as a novelist. At first she rented an apartment at the Palazzo Vagnonville. Later, she moved to the Villa Farinola at Scandicci, three miles from Florence, where she lived in grand style, entertained lavishly, collected objets d’art, dressed expensively (but not always tastefully), drove good horses, and kept many dogs, to which she was deeply attached.

In The Massarenes (1897) she painted a lurid picture of the parvenu millionaire in smart London society. Ouida prized this book, but it failed to capture the public, and her popularity waned. Thereafter she chiefly wrote essays on social questions or literary criticisms for the leading magazines for scant remuneration.

Animal rights advocacy

Ouida’s affection for animals arose from her horror of injustice. Her faith in all humanitarian causes was earnest and sincere. She was an animal rights advocate and staunchly anti-vivisectionist She was also against hunting and the fur trade. One of her nonfiction books was The New Priesthood: A Protest against Vivisection (1897). She also wrote articles against animal experiments for periodicals of the day.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

A decline in fortune, and a lost legacyImpractical, and not scrupulous in money matters, Ouida went into debt when her literary profits declined. She gradually fell into acute poverty. Her mother, who died in 1893, was buried in the Allori cemetery at Florence as a pauper. From 1894 to 1904, Ouida lived in a state often bordering on destitution, at the Villa Massoni, at Sant Alessio near Lucca.

From 1904 to 1908 she made her home at Via-reggio, where a peasant woman looked after her. Ouida’s tenement was shared with dogs that she brought in from the street.

Ouida had an artificial and affected manner, and although amiable to her friends was rude to strangers. Cynical, petulant, and prejudiced, she was quick at repartee. She was fond of painting, for which she believed she had more talent than for writing, and she was in the habit of making gifts of her sketches to her friends throughout her life.

She knew little firsthand of the Bohemians or of the wealthy men and women who were the subjects of her chief dramatis personæ. She described love like a precocious schoolgirl, and with an exuberance which, if it arrested the attention of young readers, moved the amusement of their elders.Yet, she wrote of the Italian peasants with knowledge and sympathy and of dogs with admirable fidelity.

Major works & more informationOuida published dozens of works of fiction, both as novels and volumes of collected short stories. She was almost unreasonably prolific! Here is her complete bibliography. A number of her works were adapted to early film. Some of the most popular of her works were:

Held in Bondage (1863, 1870, 1900)Strathmore (1865)Idalia (1867)Under Two Flags (1867)Tricotrin (1869)Puck (1870)A Dog of Flanders and other Stories (1872)Two Little Wooden Shoes (1874)Moths (1880)Bimbi, Stories for Children (1882)More information about Ouida (Louise de la Ramée)

Download several Ouida books (Emory University) Ouida’s works on Project Gutenberg Victorian Web Ouida on Smart Bitches, Trashy Books Listen to several books online at Librivox.orgThe post Ouida (Louise de la Ramée), English Victorian Novelist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 17, 2024

Lore Segal, Wry Chronicler of Survivor & Refugee Life

Lore Segal (March 8, 1928 – October 7, 2024) chronicled her experiences as a Holocaust survivor and an immigrant in search of a home who eventually found her way to the United States. Her fiction was oddly humorous and yet deeply insightful.

Poet Carolyn Kizer, writing about Segal’s 1985 novel Her First American in the New York Times Book Review, said Segal came “closer than anyone to writing The Great American Novel,” even though, Kizer noted with a touch of irony, its main characters were Black people and Jewish refugees and it was not written by a man.

The Kindertransport

Born Lore Valier Groszmann in Vienna, the only child of a bank accountant and a homemaker, she was one of the first children to leave Nazi-occupied Europe on the Kindertransport trains that carried thousands of Jewish children to foster families and shelters in Britain.

While it is easy to romanticize this humanitarian effort, it’s important to remember that the British were willing to take Jewish children, but not adults, and that the rescued children were not necessarily accepted with loving arms.

Lore chronicled her experiences as a young refugee in her first novel, the semi-autobiographical Other People’s Houses, published in 1964. The novel portrays the experiences of “Lorle Groszmann.” It draws on her experiences of over ten years of being shuffled from one household to another and then from one country to another, eventually with her mother.

. . . . . . . . . .

Lore in 1939, around the age of 11

. . . . . . . . .

The novel is saved from the maudlin by the narrator’s wise and unapologetic sense of self. Surrounded by crying parents and children, Lorle is curious about the journey she is about to undertake and eager to add to the list of countries she has visited. In the Netherlands, awaiting the ship that will carry her and other children in the transport to England, she wonders whether she can legitimately add that nation to her list—it is nighttime, and she cannot see anything.

During her first cold winter in England, in 1938, ten-year-old Lore wrote what she later described as a “tearjerker” letter to the refugee committee in England. It won her parents a visa to leave Austria. There, however, they were treated as enemy aliens—her father detained on the Isle of Man, and Lore and her mother restricted as to where in England they were allowed to live. Her father, eventually released from his internment and barred from working in any occupation except that of a butler, died shortly before the end of the war.

Arriving in the United States

Lore graduated from Bedford College, a women’s college at the University of London, in 1948. Then she went to the Dominican Republic, one of the few nations that would accept Jewish immigrants, to join other relatives. In 1951, Lore was finally allowed to enter the United States along with her mother, grandmother, and an uncle. They all lived in one apartment on 157th Street in Manhattan’s Washington Heights.

She married David Segal in 1961. An editor at Harper & Row and at Knopf, he died of a heart attack in 1970 at the age of forty. Social security and financial support from her late husband’s family allowed Lore to raise their two young children with the help of her mother.

Lore and her husband had moved into a rent-controlled apartment on 100th Street; shortly before David’s death, Lore’s mother Franzi had rented another apartment in the same building.

Finding Her Subject

Lore knew she was a writer since the age of twelve. Sick in bed as her mother read aloud to her from Charles Dickens, she later said, “the concept writer burst upon me. This is what I was going to do. It did not occur to me that I’d been doing it since I was ten.”

But before she could make money as a writer, Lore worked at a variety of jobs, including secretary and textile designer. She also took a course in creative writing at the New School in New York City.

At first, she said, she “couldn’t think of anything to write about. The Holocaust experience, it seemed to me, was already public knowledge … It was at a party that somebody asked me a question to which my answer was an account of the children’s transport that had brought me to England. It was my first experience of the silence of a roomful of people listening. I listened to the silence. I understood that I had a story to tell.”

In 1976, Lore published her second book, a novella titled Lucinella. Stanley Elkin praised this cult classic about a poet who is visited by Zeus as “shamelessly wonderful.” She also wrote children’s books, including Tell Me a Mitzi (1970), a tribute to her mother’s role in rearing her own children, and The Juniper Tree (1973), illustrated by her friend Maurice Sendak. She also taught — at Columbia, Princeton, and Bennington, for a while commuting between New York and Chicago to teach at the University of Illinois.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Her First AmericanHer First American was published in 1985. Ilka Weissnix, a recently arrived Jewish refugee, takes a train journey to the western United States to “look for America” in 1951. While traveling, she meets Carter Bayoux, a prominent Black intellectual and tragically alcoholic charmer who eventually becomes her lover.

As her cleverly chosen surname (Weissnix could be weiss nichts in German and might be interpreted to mean either knows nothing or not white or both) implies, Ilka is completely innocent; Carter is only too knowing, and it is the interaction of their perspectives that brings wisdom and tragic humor to the portrayal of their relationship in this novel.

Lore found her subject matter in the creative writing class that led her to write Other People’s Houses, and it was also in that class that she met the man who would serve as the model for the character of Carter Bayoux. “It’s my best book, but it took 18 years,” she said, speaking of Her First American to Matthew Schaer in a 2024 New York Times interview.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

A Pulitzer FinalistShakespeare’s Kitchen, a novel-in-stories, was published in 2007, more than twenty years after Her First American. It features an older, more accomplished Ilka, who takes a position as a visiting scholar at a Connecticut university and finds herself embroiled in the petty politics of academe.

Many of the stories that became Shakespeare’s Kitchen were published in the New Yorker; the most famous is “The Reverse Bug,” about a conference on genocide that is disrupted by the screams of victims somehow mysteriously incorporated into the lecture hall’s sound system.

In 2008, when Segal was eighty, Shakespeare’s Kitchen was named a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize. That was the same year that independent publisher Melville House arranged to reissue Lucinella, which had gone out of print.

Melville House went on to publish her last novel, Half the Kingdom, in 2013. Described as “darkly comic,” it portrays an alarming uptick in advanced dementia cases in a hospital emergency room. In 2019, a collection of essays, short stories, and novel excerpts appeared as The Journal I Did Not Keep. That collection is an excellent choice for those who want to explore Lore Segal’s writing before deciding to commit to any one of her novels or short story collections.

Though she didn’t win the Pulitzer, she received numerous prestigious awards in her lifetime, including the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, O. Henry Prize, Guggenheim Fellowship, and many others. Here is the full list of her literary awards.

Writing Until the Very End

Lore Segal wrote right up to her death, despite the ailments of age, which in her case included diminished vision and the need for a walker. She published a series of stories about a group of elderly ladies who meet for lunch and then, because of the pandemic and later because of their decreasing mobility, meet on Zoom.

Many of these stories were collected in Ladies Lunch (2023). The ladies discuss aging and death, the loss of friends, and the failures of family members to understand what they want and need—always with the wisdom and wry humor that Segal brought to all her work.

“Stories About Us,” which appeared in the New Yorker the week before she died at the age of ninety-six, begins with the line, “Let’s get the complaining out of the way,” and ends with a discussion of the best word to use in a translation of Austrian Jewish poet Theodor Kramer.

Her editor for that story, Cressida Leyshon, recalled discussing edits with Segal while she was in hospice shortly before her death. Writing about those discussions, Leyshon said:

“Her voice was faint, but the lilt of her Austrian-accented English was clear, and she would often repeat aloud a sentence where I’d suggested an edit. Sometimes she’d agree, but at other times, with a merry incredulity, she’d say no. Of course, she implied, I should understand what a ridiculous suggestion this was! And, of course, she was right.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.

Further Reading and Sources

Gornick, Vivian. “Isn’t It Interesting?” New York Review of Books, 8 February 2024.Kizer, Carolyn. “The Education of Ilka Weissnix.” New York Times Book Review, 19 May 1985. Leyshon, Cressida. “Lore Segal Will Keep on Talking Through Her Stories.”The New Yorker, 13 October 2024. Marcus, James “How Lore Segal Saw the World in a Nutshell.” Atlantic Monthly 10 October, 2024. Schaer, Matthew “A Master Storyteller, at the End of Her Story.” 6 October 2024.

The New York Times, 6 October 2024. Smith, Harrison “Lore Segal, acclaimed novelist of memory and displacement, dies at 96.”

Washington Post, 9 October 2024.

Works by Lore Segal

Fiction

Other People’s Houses (1964)Lucinella: A Novel (1976)Her First American: A Novel (1985)Shakespeare’s Kitchen (2007)Half the Kingdom (2013)Ladies Lunch (2023)Children’s books

Tell Me a Mitzi. Illustrated by Harriet Pincus (1970)All the Way Home (1973)Tell Me a Trudy. Illustrated by Rosemary Wells (1977) The Story of Old Mrs. Brubeck and How She Looked for Trouble and Where She Found Him (1981) The Story of Mrs. Lovewright and Purrless Her Cat (1985) Morris the Artist (2003) Why Mole Shouted and Other Stories (2004)More Mole Stories and Little Gopher, Too (2005)The post Lore Segal, Wry Chronicler of Survivor & Refugee Life appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Lore Segal, Chronicler of the Immigrant & Refugee Experience

Lore Segal (March 8, 1928 – October 7, 2024) chronicled her experiences as a Holocaust survivor and an immigrant in search of a home who eventually found her way to the United States. Her fiction was oddly humorous and yet deeply insightful.

Poet Carolyn Kizer, writing about Segal’s 1985 novel Her First American in the New York Times Book Review, said Segal came “closer than anyone to writing The Great American Novel,” even though, Kizer noted with a touch of irony, its main characters were Black people and Jewish refugees and it was not written by a man.

The Kindertransport

Born Lore Valier Groszmann in Vienna, the only child of a bank accountant and a homemaker, she was one of the first children to leave Nazi-occupied Europe on the Kindertransport trains that carried thousands of Jewish children to foster families and shelters in Britain.

While it is easy to romanticize this humanitarian effort, it’s important to remember that the British were willing to take Jewish children, but not adults, and that the rescued children were not necessarily accepted with loving arms.

Lore chronicled her experiences as a young refugee in her first novel, the semi-autobiographical Other People’s Houses, published in 1964. The novel portrays the experiences of “Lorle Groszmann.” It draws on her experiences of over ten years of being shuffled from one household to another and then from one country to another, eventually with her mother.

. . . . . . . . . .

Lore in 1939, around the age of 11

. . . . . . . . .

The novel is saved from the maudlin by the narrator’s wise and unapologetic sense of self. Surrounded by crying parents and children, Lorle is curious about the journey she is about to undertake and eager to add to the list of countries she has visited. In the Netherlands, awaiting the ship that will carry her and other children in the transport to England, she wonders whether she can legitimately add that nation to her list—it is nighttime, and she cannot see anything.

During her first cold winter in England, in 1938, ten-year-old Lore wrote what she later described as a “tearjerker” letter to the refugee committee in England. It won her parents a visa to leave Austria. There, however, they were treated as enemy aliens—her father detained on the Isle of Man, and Lore and her mother restricted as to where in England they were allowed to live. Her father, eventually released from his internment and barred from working in any occupation except that of a butler, died shortly before the end of the war.

Arriving in the United States

Lore graduated from Bedford College, a women’s college at the University of London, in 1948. Then she went to the Dominican Republic, one of the few nations that would accept Jewish immigrants, to join other relatives. In 1951, Lore was finally allowed to enter the United States along with her mother, grandmother, and an uncle. They all lived in one apartment on 157th Street in Manhattan’s Washington Heights.

She married David Segal in 1961. An editor at Harper & Row and at Knopf, he died of a heart attack in 1970 at the age of forty. Social security and financial support from her late husband’s family allowed Lore to raise their two young children with the help of her mother.

Lore and her husband had moved into a rent-controlled apartment on 100th Street; shortly before David’s death, Lore’s mother Franzi had rented another apartment in the same building.

Finding Her Subject

Lore knew she was a writer since the age of twelve. Sick in bed as her mother read aloud to her from Charles Dickens, she later said, “the concept writer burst upon me. This is what I was going to do. It did not occur to me that I’d been doing it since I was ten.”

But before she could make money as a writer, Lore worked at a variety of jobs, including secretary and textile designer. She also took a course in creative writing at the New School in New York City.

At first, she said, she “couldn’t think of anything to write about. The Holocaust experience, it seemed to me, was already public knowledge … It was at a party that somebody asked me a question to which my answer was an account of the children’s transport that had brought me to England. It was my first experience of the silence of a roomful of people listening. I listened to the silence. I understood that I had a story to tell.”

In 1976, Lore published her second book, a novella titled Lucinella. Stanley Elkin praised this cult classic about a poet who is visited by Zeus as “shamelessly wonderful.” She also wrote children’s books, including Tell Me a Mitzi (1970), a tribute to her mother’s role in rearing her own children, and The Juniper Tree (1973), illustrated by her friend Maurice Sendak. She also taught — at Columbia, Princeton, and Bennington, for a while commuting between New York and Chicago to teach at the University of Illinois.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Her First AmericanHer First American was published in 1985. Ilka Weissnix, a recently arrived Jewish immigrant, meets Carter Bayoux, a prominent Black intellectual and tragically alcoholic charmer. He becomes her teacher and lover during a train journey to the western United States, where she has gone, like a character in the famous Simon and Garfunkel song, to “look for America.”

As her cleverly chosen surname (Weissnix could be weiss nichts in German and might be interpreted to mean either knows nothing or not white or both) implies, Ilka is completely innocent; Carter is only too knowing, and it is the interaction of their perspectives that brings wisdom and tragic humor to the portrayal of their relationship in this novel.

Lore found her subject matter in the creative writing class that led her to write Other People’s Houses, and it was also in that class that she met the man who would serve as the model for the character of Carter Bayoux. “It’s my best book, but it took 18 years,” she said, speaking of Her First American to Matthew Schaer in a 2024 New York Times interview.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

A Pulitzer FinalistShakespeare’s Kitchen, a novel-in-stories, was published in 2007, more than twenty years after Her First American. It features an older, more accomplished Ilka, who takes a position as a visiting scholar at a Connecticut university and finds herself embroiled in the petty politics of academe.

Many of the stories that became Shakespeare’s Kitchen were published in the New Yorker; the most famous is “The Reverse Bug,” about a conference on genocide that is disrupted by the screams of victims somehow mysteriously incorporated into the lecture hall’s sound system.

In 2008, when Segal was eighty, Shakespeare’s Kitchen was named a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize. That was the same year that independent publisher Melville House arranged to reissue Lucinella, which had gone out of print.

Melville House went on to publish her last novel, Half the Kingdom, in 2013. Described as “darkly comic,” it portrays an alarming uptick in advanced dementia cases in a hospital emergency room. In 2019, a collection of essays, short stories, and novel excerpts appeared as The Journal I Did Not Keep. That collection is an excellent choice for those who want to explore Lore Segal’s writing before deciding to commit to any one of her novels or short story collections.

Though she didn’t win the Pulitzer, she received numerous prestigious awards in her lifetime, including the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, O. Henry Prize, Guggenheim Fellowship, and many others. Here is the full list of her literary awards.

Writing Until the Very End

Lore Segal wrote right up to her death, despite the ailments of age, which in her case included diminished vision and the need for a walker. She published a series of stories about a group of elderly ladies who meet for lunch and then, because of the pandemic and later because of their decreasing mobility, meet on Zoom.

Many of these stories were collected in Ladies Lunch (2023). The ladies discuss aging and death, the loss of friends, and the failures of family members to understand what they want and need—always with the wisdom and wry humor that Segal brought to all her work.

“Stories About Us,” which appeared in the New Yorker the week before she died at the age of ninety-six, begins with the line, “Let’s get the complaining out of the way,” and ends with a discussion of the best word to use in a translation of Austrian Jewish poet Theodor Kramer.

Her editor for that story, Cressida Leyshon, recalled discussing edits with Segal while she was in hospice shortly before her death. Writing about those discussions, Leyshon said:

“Her voice was faint, but the lilt of her Austrian-accented English was clear, and she would often repeat aloud a sentence where I’d suggested an edit. Sometimes she’d agree, but at other times, with a merry incredulity, she’d say no. Of course, she implied, I should understand what a ridiculous suggestion this was! And, of course, she was right.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.

Further Reading and Sources

Gornick, Vivian. “Isn’t It Interesting?” New York Review of Books, 8 February 2024.Kizer, Carolyn. “The Education of Ilka Weissnix.” New York Times Book Review, 19 May 1985. Leyshon, Cressida. “Lore Segal Will Keep on Talking Through Her Stories.”The New Yorker, 13 October 2024. Marcus, James “How Lore Segal Saw the World in a Nutshell.” Atlantic Monthly 10 October, 2024. Schaer, Matthew “A Master Storyteller, at the End of Her Story.” 6 October 2024.

The New York Times, 6 October 2024. Smith, Harrison “Lore Segal, acclaimed novelist of memory and displacement, dies at 96.”

Washington Post, 9 October 2024.

Works by Lore Segal

Fiction

Other People’s Houses (1964)Lucinella: A Novel (1976)Her First American: A Novel (1985)Shakespeare’s Kitchen (2007)Half the Kingdom (2013)Ladies Lunch (2023)Children’s books

Tell Me a Mitzi. Illustrated by Harriet Pincus (1970)All the Way Home (1973)Tell Me a Trudy. Illustrated by Rosemary Wells (1977) The Story of Old Mrs. Brubeck and How She Looked for Trouble and Where She Found Him (1981) The Story of Mrs. Lovewright and Purrless Her Cat (1985) Morris the Artist (2003) Why Mole Shouted and Other Stories (2004)More Mole Stories and Little Gopher, Too (2005)The post Lore Segal, Chronicler of the Immigrant & Refugee Experience appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 16, 2024

Effie Lee Newsome, Harlem Renaissance Era Poet

Effie Lee Newsome (1885–1979), was a writer, illustrator, and librarian whose poetry for adults and children made her a notable literary figure of the Harlem Renaissance.

From the time her poetry was first published in NAACP’s The Crisis, her work was regularly featured in anthologies and other publications, particularly in the 1920s.

Mary Effie Lee was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and raised in Wilberforce, Ohio. Her parents were Mary Elizabeth Ashe Lee and Benjamin Franklin Lee. Her clergyman father was editor-in-chief of the Christian Recorder and served as president of Wilberforce University.

Fascinating side note: Benjamin Franklin Lee was descended from free Blacks who founded the Gouldtown community (New Jersey) in the 18th century. Gouldtown was once cited as “America’s Oldest Negro Community.”

Effie took classes at Wilberforce University, Oberlin College, Philadelphia Academy of the Arts, and the University of Pennsylvania. Though she didn’t complete a degree, she was able to explore her dual interests in art and writing. She and her sister Consuelo, also a poet, both worked as illustrators for children’s magazines.

The Brownie’s Book and the Little Page

Effie began publishing her poems and stories in The Crisis in 1915. One of her most anthologized poems, “Morning Light: The Dew-Drier,” appeared in a 1918 issue. Her poems were regularly featured in The Brownie’s Book, a magazine for Black children that was a spinoff of The Crisis — both founded by W.E.B. Du Bois. Jessie Redmon Fauset was its editor.

As a major contributor to The Brownie’s Book, Effie was among the first contingent of writers to create poems expressly for Black children. Subsequently, writing for children became a longstanding professional interest for Effie and something for which she became known. In 1924, she became the editor of the children’s column “Little Page” in The Crisis, a position that lasted for a decade. Her poetry encouraged younger readers to appreciate their worth and beauty, and to marvel at the world around them.

Marriage and a profession

In 1920, after marrying Rev. Henry Nesby Newsome, an African Methodist Episcopal Church minister, she began using the name of Effie Lee Newsome. Until then she had been Mary Effie Lee, her given family name.

The couple briefly lived in Birmingham, Alabama, where she taught in an elementary school and worked as the school librarian. When they returned to Wilberforce, she continued to work as a librarian in various schools and colleges. Her last position was at Wilberforce University, where she remained until her retirement in 1963.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also:

19 Poems by Effie Lee Newsome

. . . . . . . . . .

Anthologies and two books of collected poetryThroughout the 1920s, Effie continued to contribute to Black poetry anthologies. In her biographical note in Caroling Dusk: An Anthology of Verse by Negro Poets, a classic 1927 collection edited by Countee Cullen, she described herself as “ a lover of the out-of-doors, and of the beautiful.”

Her only published collection, Gladiola Garden: Poems of Outdoors and Indoors for Second Grade Readers, was published in 1940.

The Oxford Companion to American Literature, stated that Effie’s writing gave children “two great gifts: a keen sense of their own inestimable value and an avid appreciation of the natural world.” A digital copy of this book, with its generous collection of dozens of poems, can be viewed here (New York Public Library Digital Collections).

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Wonders: The Best Children’s Poems of Effie Lee Newsome was published in 1999. It includes poems from Gladiola Garden, The Brownies’ Book magazine, and “The Little Page” column from The Crisis. According to the publisher, this collection “reintroduces Effie Lee Newsome and the spirit of her work to a new generation of children.”

Not a lot more is known about Effie Lee Newsome’s life, and it’s next to impossible to find other images of her than the one shown here. Hers seemed a life of steady work and creativity with little drama or upheaval. Though Effie never lived in New York City, her thoughtful poetry was a valued contribution to Harlem Renaissance era literature. Perhaps the time for her work to be more widely known and studied is at hand.

Sources and more information African American Registry Afro-American: “Effie Lee Newsome, African American Poet of the 1920s” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly; Johns Hopkins University Press, Summer 1988.Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 76, Afro-American Writers 1940 – 1955 (1988)Notable Black American Women Book 1. Edited by Jessie Carney Smith,1992The Concise Oxford Companion to African American Literature, First edition, 1997The post Effie Lee Newsome, Harlem Renaissance Era Poet appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 12, 2024

The Heart of a Woman by Georgia Douglas Johnson (1918 – full text)

Georgia Douglas Johnson (1880 – 1966) was a respected poet and playwright associated with the Harlem Renaissance movement. Following is the full text of her first published collection, The Heart of a Woman and Other Poems (1918).

The Heart of a Woman was followed by Bronze (1922) and An Autumn Love Cycle (1928). Many years later she came out with Share My World (1962). With four published collections, it’s quite likely that Georgia was the most widely published of the female poets of her era.

Georgia’s poems were published in numerous periodicals and anthologies, particularly in the 1920s. In her poetry, Georgia addressed issues of race as well as universal themes of love, motherhood, and being a woman in a male-dominated world.

The Heart of a Woman featured poems that were specific to Georgia’s life, yet universal to the female experience. They spoke of love and hope, as well as of loneliness and disappointments. Her frustration with women’s constrained roles was expressed with grace and subtlety.

The Heart of a Woman (1981), the title of the fourth volume in Maya Angelou‘s seven-part autobiography series that began with I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings, is named for the first, eponymous poem in this collection.

The Heart of a Woman was published by the Cornhill Company (Boston) and is in the public domain. You can see what it looked like when it was first published on Internet Archive.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Georgia Douglas Johnson

See also: Bronze (1922 – full text)

. . . . . . . . . .

by Georgia Douglas JohnsonContents

Introduction by William Stanley Braithwaite

The Heart of a Woman

Gossamer

The Dreams of the Dreamer

Sympathy

Contemplation

Dead Leaves

Dawn

Elevation

Whither?

Quest

Mate

Emblems

Mirrored

Pent

Pages from Life

Recall

Foredoom

Peace

Despair

Eventide

Gethsemane

Gilead

Impelled

In Quest

Inevitably

Isolation

Joy

Memory

Modulations

Omega

Poetry

Posthumous

Query

Recompense

Repulse

Rhythm

Smothered Fires

Supreme

Sympathy

Tears and Kisses

The Measure

Thrall

Tired

What Need Have I For Memory?

When I Am Dead

Whene’er I Lift My Eyes to Bliss

Where?

Youth

. . . . . . . . . . .

Introduction by William Stanley Braithwaite

The poems in this book are intensely feminine and for me this means more than anything else that they are deeply human. We are yet scarcely aware, in spite of our boasted twentieth-century progress, of what lies deeply hidden, of mystery and passion, of domestic love and joy and sorrow, of romantic visions and practical ambitions, in the heart of a woman.

The emancipation of woman is yet to be wholly accomplished; though woman has stamped her image on every age of the world’s history, and in the heart of almost every man since time began, it is only a little over half of a century since she has either spoke or acted with a sense of freedom.

During this time she has made little more than a start to catch up with man in the wonderful things he has to his credit; and yet all that man has to his credit would scarcely have been achieved except for the devotion and love and inspiring comradeship of woman. Here, then, is lifted the veil, in these poignant songs and lyrics. To look upon what is revealed is to give one a sense of infinite sympathy; to make one kneel in spirit to the marvelous patience, the wonderful endurance, the persistent faith, which are hidden in this nature.

The heart of a woman falls back with the night.

And enters some alien cage in its plight,

And tries to forget it has dreamed of the stars

While it breaks, breaks, breaks on the sheltering bars.

sings the poet.

And the songs of the singer

Are tones that repeat

The cry of the heart

Till it ceases to beat.

This verse just quoted is from “The Dreams of the Dreamer,” and with the previous quotation tells us that this woman’s heart is keyed in the plaintive, knows the sorrowful agents of life and experience which knock and enter at the door of dreams.

But women have made the saddest songs of the world, Sappho / no less than Elizabeth Barrett Browning / Ruth the Moabite/ poetess gleaning in the fields of Boaz no less than Amy Levy / the Jewess who broke her heart against the London pavements; and no less does sadness echo its tender and appealing sigh in these songs and lyrics of Georgia Douglas Johnson. But sadness is a kind of felicity with woman, paradoxical as it may seem; and it is so because through this inexplicable felicity they touched, intuitionally caress, reality.

So here engaging life at its most reserved sources, whether the form or substance through which it articulates be nature, or the seasons, touch of hands or lips, love, desire, or any of the emotional abstractions which sweep like fire or wind or cooling water through the blood, Mrs. Johnson creates just that reality of woman’s heart and experience with astonishing raptures.

It is a kind of privilege to know so much about the secrets of woman’s nature, a privilege all the more to be cherished when given, as in these poems, with such exquisite utterance, with such a lyric sensibility.

— William Stanley Braithwaite, Cambridge, Massachusetts

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Heart of a Woman

The heart of a woman goes forth with the dawn,

As a lone bird, soft winging, so restlessly on,

Afar o’er life’s turrets and vales does it roam

In the wake of those echoes the heart calls home.

The heart of a woman falls back with the night,

And enters some alien cage in its plight,

And tries to forget it has dreamed of the stars

While it breaks, breaks, breaks on the sheltering bars.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Gossamer

The dreams of the dreamer

Are life-drops that pass

The break in the heart

To the soul’s hour-glass.

The songs of the singer

Are tones that repeat

The cry of the heart

‘Till it ceases to beat.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Dreams of the Dreamer

The dreams of the dreamer

Are life-drops that pass

The break in the heart

To the soul’s hour-glass.

The songs of the singer

Are tones that repeat

The cry of the heart

‘Till it ceases to beat.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Sympathy

My joy leaps with your ecstasy,

In sympathy divine;

The smiles that wreathe upon your lips.

Find sentinels on mine:

Your lightest sigh I’m echoing,

I tremble with your pain,

And all your tears are falling

In my heart like bitter rain.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contemplation

We stand mute!

No words can paint such fragile imagery,

Those prismic gossamers that roll

Beyond the sky-line of the soul;

We stand mute!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Dead Leaves

The breaking dead leaves ‘neath my feet

A plaintive melody repeat,

Recalling shattered hopes that lie

As relics of a bygone sky.

Again I thread the mazy past,

Back where the mounds are scattered fast –

Oh! foolish tears, why do you start,

To break of dead leaves in the heart?

. . . . . . . . . . .

Dawn

Trailing night’s sand-sifted stars,

Rainbows sweep, as day unbars.

Fragrant essences of morn,

Bathe humanity — new-born!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Elevation

There are highways in the soul,

Heights like pyramids that rise

Far beyond earth-veiled eyes,

Sweeping through the barless skies

O’er the line where daylight dies —

There are highways in the soul!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Whither?

Minutes swiftly throb and pass,

Shadows cross the dial-glass,

Speeding ever to some call,

Weary world and shadows, all.

Down the closing aisles of day,

Tramping footsteps die away,

But no tidings thread the gloom,

From the hushed and silent tomb.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Quest

The phantom happiness I sought

O’er every crag and moor;

I paused at every postern gate,

And knocked at every door;

In vain I searched the land and sea,

E’en to the inmost core,

The curtains of eternal night

Descend — my search is o’er.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Mate

Our separate winding ways we trod,

Along the highways, unto God,

Unbonded by the clasp of hand,

Without a vow — we understand.

Estranged for aye, the fusing kiss.

Omnipotent, we bide in this —

They need no trammeling of bars

Whose souls were welded with the stars.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Emblems

A wordless kiss, a stifled sigh,

A trembling lip, a downcast eye,

“Alas,” they say,

“A-day, a-day,”

The cruse has failed, the lamp must die!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Mirrored

When lone and solitaire within your chamber,

With lamp unlit, as evening shades unroll.

If you reveal the trail your thoughts are taking,

I then may read the riddle of your soul.

For it is then, the tired mind unveiling,

Drifts stark into the holy after-glow.

Within the hour of quiet meditation.

The tidal thoughts, like limpid waters, flow.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Pent

The rain is falling steadily

Upon the thirsty earth,

While dry-eyed, I remain, and calm

Amid my own heart’s dearth.

Break! break! ye flood-gates of my tears

All pent in agony,

Rain, rain! upon my scorching soul

And flood it as the sea!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Pages from Life

Not for your tender eyes that shine,

Nor for your red lips pulsing wine,

I love you, dear: your soul divine.

In sweet captivity, holds mine!

. . .

The tender eyes have lost their glow,

The flagons of the lips run low.

The autumn trembles in the air, —

A woman passes solitaire!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Recall

Winter — aback sweeps the inward eye,

Fleet o’er the trail to a rose-wreathed sky,

Girt by a cordon of dreams I dwell

Deep in the heart of the old-time spell.

Almost, the tones of your whispered word,

Almost! the thrill that your dear lips stirred,

Almost!! that wild pulsing throb again —

Almost!!! —

(‘Tis winter, the falling rain).

. . . . . . . . . . .

Foredoom

Her life was dwarfed, and wed to blight,

Her very days were shades of night,

Her every dream was born entombed.

Her soul, a bud, — that never bloomed.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Peace

I rest me deep within the wood,

Drawn by its silent call,

Far from the throbbing crowd of men

On nature’s breast I fall.

My couch is sweet with blossoms fair,

A bed of fragrant dreams,

And soft upon my ear there falls

The lullaby of streams.

The tumult of my heart is stilled,

Within this sheltered spot.

Deep in the bosom of the wood.

Forgetting, and — forgot!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Despair

The curtains of twilight are drawn in the west

And vespers are sweet on the air,

While I, through my leafless, ungarlanded way

But pause at the gates of despair.

Good-bye to the hopes that were never fulfilled,

Good-bye to the fond dreams that failed.

Good-bye to my dead that has never been born.

Good-bye to love’s ship that ne’er sailed.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Eventide

The silence of the brooding night,

Enfolds me with its eerie light;

I lie upon its shadowed breast

A pilgrim, wearying for rest

Nightfall! thy sable curtains steep

My very soul in solace deep,

God sends thee with thy soothing balms,

That I may falter to thy arms.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Gethsemane

Into the garden of sorrow,

Some day we all must roam,

If not to-day, then to-morrow,

Bow ‘neath its purple dome.

Out from the musk-laden banqueting halls,

Doffing our mirth-spangled vestments like thralls,

Softly we wend to Gethsemane,

In the hour that sorrow calls!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Gilead

Walk within thy own heart’s temple, child, and rest,

What you seek abides forever in thy breast.

Closer than thy folded arm

Is the soul-renewing-balm,

Walk within thy own heart’s temple, child, and rest.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Impelled

Athwart the sky the great sun sails,

Through aeons thus, the daylight trails,

And man, living breath of the sod

Beholding, in his heart knows God.

Throughout the night’s long brooding deep,

Earth’s trustful children die-to-sleep.

But with the whisperings of morn

Awake, unto the day, new-born.

The mystery of earth untold,

The great infinite, none behold,

Forge ever new the spiral chain,

Revolving man to God again.

. . . . . . . . . . .

In Quest

With the first blush of morning, my soul is awing,

Away o’er the phantom lands free, wandering,

I seek thee in hamlet, in woodland, and hall.

Till night-shades, enfolding my tired heart, fall.

Yet ever and alway, like the thrush in a tree.

My heart lifts its preluding love-song to thee;

I call through the days, through the long weary years.

And slumber at night-fall, refreshed by my tears.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Inevitably

There’s nothing in the world that clings

As does a memory that stings;

While happy hours fade and pass,

Like shadows in a looking-glass.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Isolation

Alone! yes, evermore alone — isolate each his way,

Though hand is echoing to hand vain sophistries of clay.

Within that veilèd, mystic place where bides the inmost soul,

No twain shall pass while tides shall wax, nor changing seasons roll.

Enisled, apart our pilgrimage, despite the arms that twine.

Despite the fusing kiss that wields the magic charm of wine.

Despite the interplay of sigh, the surge of sympathy.

We tread in solitude remote, the trail of destiny!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Joy

There’s a soft rosy glow o’er the whole world to-day,

There’s a freshness and fragrance that trembles in May,

There’s a lilt in the music that vibrates and thrills

From the uttermost glades to the tops of the hills.

Oh! I am so happy, my heart is so light.

The shades and the shadows have vanished from sight,

This wild pulsing gladness throbs like a sweet pain —

O soul of me, drink, ere night falleth again!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Memory

Love’s roses I gathered, all dewy, in May,

My heart holds the breath of their attar to-day;

And now, while the blasts of the winter winds ring,

I hear not the tempest, I’m dreaming of Spring.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Modulations

The petals of the faded rose

Commingle silently,

One with the atoms of the dust,

One with the chaliced sea. –

The essence of my fleeting youth

Caught in the web of time,

Exhales within the springing flowers

Or breathes in love sublime.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Omega

The fragile fabric of our dream

Drifts as a feather down life’s stream

The long defile of empty days

Grim silhouetted, mock my gaze.

Though oft escapes the stifled sigh,

A desert ever broods my eye —

Since you have utterly forgot,

God grant that I remember not!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Poetry

Behold! the living thrilling lines

That course the blood like madd’ning wines,

And leap with scintillating spray

Across the guards of ecstasy.

The flame that lights the lurid spell

Springs from the soul’s artesian well,

Its fairy filament of art

Entwines the fragments of a heart.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Posthumous

Of what avail the tardy showers,

To the famished summer flowers?

All in vain the rain-drops cry,

Dead things never make reply.

Life’s belated cup of bliss,

Woo the weary lips to kiss,

When the singing is a sigh.

Pulses quivering, to die.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Query

Is she the sage who will not sip

The cup love presses to her lip?

Or she who drinks the mad cup dry,

And turns with smiling face — to die?

. . . . . . . . . . .

Recompense

Roses after rain,

Pleasure after pain,

Happiness will soothe the sigh,

Smiles await the tear-dimmed eye

Bloom will follow blight,

Daylight trails the night,

Life is sweeter

Love is deeper

In the heart’s twilight!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Repulse

Nobody cares when I am glad,

I beat upon their hearts in glee,

“Drink, drink joy’s brimming cup with me,”

All echoless, my ecstasy —

Nobody cares when I am glad.

Nobody cares when I am sad,

Whene’er I seek compassion’s breast,

I falter wounded from my quest

Back! back into my heart, sore prest —

Nobody cares when I am sad.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Rhythm

Oh, my fancy teems with a world of dreams, —

They revolve in a glittering fire,

How they twirl and go with the tunes that flow

On the breath of my soul-strung lyre.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Smothered Fires

A woman with a burning flame

Deep covered through the years

With ashes. Ah! she hid it deep,

And smothered it with tears.

Sometimes a baleful light would rise

From out the dusky bed,

And then the woman hushed it quick

To slumber on, as dead.

At last the weary war was done

The tapers were alight,

And with a sigh of victory

She breathed a soft — good-night!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Supreme

The fairest lips are those we kiss,

With greatest ecstasy and bliss;

The brightest eyes, are those that shine,

Unchangingly through changing time;

The greatest love is that we know.

When life is just an afterglow.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Sympathy

My joy leaps with your ecstasy,

In sympathy divine;

The smiles that wreathe upon your lips.

Find sentinels on mine:

Your lightest sigh I’m echoing,

I tremble with your pain,

And all your tears are falling

In my heart like bitter rain.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Tears and Kisses

There are tears sweet, refreshing like dewdrops that rise,

There are tears far too deep for the lakes of the eyes.

There are kisses like thistledown, fitfully sped,

There are kisses that live in the hearts of the dead.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Measure

Fierce is the conflict — the battle of eyes,

Sure and unerring, the wordless replies,

Challenges flash from their ambushing caves

Men, by their glances, are masters or slaves.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Thrall

Fragile, tiny, just a sprite,

Holding me a thrall bedight,

Stronger than a giant’s wand

Serves the word of your command.

Out from rushing worlds, though low

Should you whisper, I would know,

And would answer, though the breath

Be the gateway unto death.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Tired

I’m tired, days and nights to me

Drag on in slow monotony,

With not a single star in sight

To lend a gleam of cheering light.

I’m tired, there are none to care

That I am drifting to despair:

O shadows! take me to your breast

For I am tired — I would rest.

. . . . . . . . . . .

What Need Have I For Memory?

What need have I for memory,

When not a single flower

Has bloomed within life’s desert

For me, one little hour.

What need have I for memory

Whose burning eyes have met

The corse of unborn happiness

Winding the trail regret?

. . . . . . . . . . .

When I Am Dead

When I am dead, withhold, I pray, your blooming legacy;

Beneath the willows did I bide, and they should cover me;

I longed for light and fragrance, and I sought them far and near,

O, it would grieve me utterly, to find them on my bier!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Whene’er I Lift My Eyes to Bliss

Whene’er I lift my eyes to bliss,

I stagger blind with pain,

Afar into the folding night

The silence, and the rain.

Whene’er I feel the urge of Spring,

A throbbing, unknown woe

Enfolds me; I am desolate

When love is calling low.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Where?

I called you through the silent night

Across the brooding deep,

I sought you in the shadowland

From out the world — asleep;

No answer echoed to my call,

And now my way I thread

About the lowly mounds that rise

Among the silent dead.

Though voiceless, you will hear my call,

Your soul will heed my cry.

Will rise, and mock the prison where

Your bones recumbent lie.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Youth

The dew is on the grasses, dear,

The blush is on the rose.

And swift across our dial-youth,

A shifting shadow goes.

The primrose moments, lush with bliss,

Exhale and fade away,

Life may renew the Autumn time,

But nevermore the May!

Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance to Rediscover and Read

Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance to Rediscover and Read

The post The Heart of a Woman by Georgia Douglas Johnson (1918 – full text) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 11, 2024

10 Contemporary Novels About Bookstores and Libraries

For those of us who love (or make that obsessed with) books, novels about books, bookstores, and libraries are the icing on the cake. Reading about books and bookish people in fictional narratives, might seem odd, but for the devout bibliophile, it makes perfect sense.

Presented here is a selection of contemporary novels whose stories are centered around bookstores or libraries. What could be cozier reading on a chilly day accompanied by a warm drink, a blanket, and a four-legged friend or two?

. . . . . . . . . .

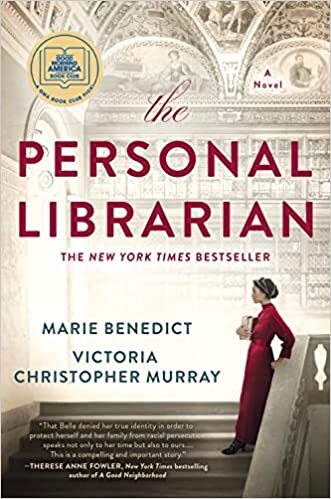

The Personal Librarian by Marie Benedict

From the publisher: A remarkable novel about J. P. Morgan’s personal librarian, Belle da Costa Greene, the Black American woman who was forced to hide her true identity and pass as white in order to leave a lasting legacy that enriched our nation, from New York Times bestselling authors Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray.

Belle da Costa Greene is hired by J. P. Morgan to curate a collection of rare manuscripts, books, and artwork for his newly built Pierpont Morgan Library. Belle becomes a fixture in New York City society and one of the most powerful people in the art and book world, known for her impeccable taste and shrewd negotiating for critical works as she helps create a world-class collection.

The Personal Librarian tells the story of an extraordinary woman, famous for her intellect, style, and wit, and shares the lengths she must go to—for the protection of her family and her legacy—to preserve her carefully crafted white identity in the racist world in which she lives.

The Personal Librarian on Bookshop.org*

The Personal Librarian on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

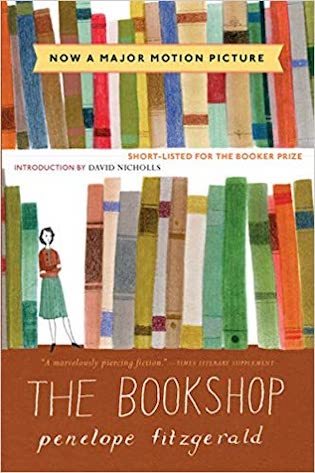

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald

From the publisher: Set in 1959, Florence Green, a kindhearted widow with a small inheritance, risks everything to open a bookshop—the only bookshop—in the seaside town of Hardborough. By making a success of a business so impractical, she invites the hostility of the town’s less prosperous shopkeepers.

By daring to enlarge her neighbors’ lives, she crosses Mrs. Gamart, the local arts doyenne. Florence’s warehouse leaks, her cellar seeps, and the shop is apparently haunted. Only too late does she begin to suspect the truth: a town that lacks a bookshop isn’t always a town that wants one.

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald, published in 1978, was adapted to film in 2017, to mixed reviews by audiences and critics. Devotees of media about bookstores should nevertheless get some enjoyment from it.

The Bookshop on Bookshop.org*

The Bookshop on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

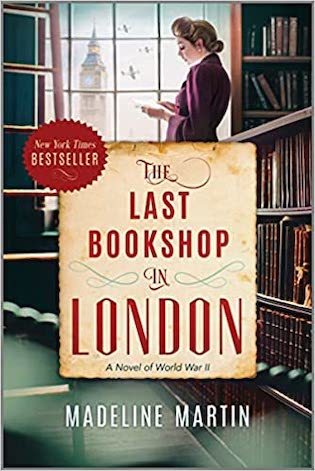

The Last Bookshop in London: A Novel of World War IIby Madeline Martin

From the publisher: August 1939 — London prepares for war as enemy forces sweep across Europe. Grace Bennett has always dreamed of moving to the city, but the bunkers and drawn curtains that she finds on her arrival are not what she expected. And she certainly never imagined she’d wind up working at Primrose Hill, a dusty old bookshop nestled in the heart of London.

Through blackouts and air raids as the Blitz intensifies, Grace discovers the power of storytelling to unite her community in ways she never dreamed—a force that triumphs over even the darkest nights of the war. This 2021 publication has become a bestseller and a reader favorite.

The Last Bookshop in London on Bookshop.org*

The Last Bookshop in London on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Booklover’s Library by Madeline Martin

From the publisher: A heartwarming story about a mother and daughter in wartime England and the power of books that bring them together, by the bestselling author of The Last Bookshop in London. In Nottingham, England, widow Emma Taylor finds herself in desperate need of a job.

She and her beloved daughter Olivia have always managed just fine on their own, but with the legal restrictions prohibiting widows with children from most employment opportunities, she’s left with only one option: persuading the manageress at Boots’ Booklover’s Library to take a chance on her with a job.

When the threat of war in England becomes a reality, Olivia must be evacuated to the countryside. In the wake of being separated from her daughter, Emma seeks solace in the unlikely friendships she forms with her neighbors and coworkers, and a renewed sense of purpose through the recommendations she provides to the library’s quirky regulars. But the job doesn’t come without its difficulties … As the Blitz intensifies in Nottingham and Emma fights to reunite with her daughter, she must learn to depend on her community and the power of literature more than ever to find hope in the darkest of times.

The Booklover’s Library on Bookshop.org*

The Booklover’s Library on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Lost Bookshop by Evie Woods

From the publisher: “The thing about books,” she said “is that they help you to imagine a life bigger and better than you could ever dream of.” On a quiet street in Dublin, a lost bookshop is waiting to be found .. For too long, Opaline, Martha and Henry have been the side characters in their own lives.

But when a vanishing bookshop casts its spell, these three unsuspecting strangers will discover that their own stories are every bit as extraordinary as the ones found in the pages of their beloved books. And by unlocking the secrets of the shelves, they find themselves transported to a world of wonder… where nothing is as it seems.

The Lost Bookshop on Bookshop.org*

The Lost Bookshop on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

The English Bookshop by Janis Wildy

From the publisher: Lucy isn’t ready for a life-changing journey when it comes knocking; she just wants to keep everything the same as the day her stepfather died. Unfortunately, expenses have overtaken her small family business, forcing her to do something quickly to keep it afloat.

When Lucy finds out she has inherited a bookshop in England, she travels to see it, intent on selling the property as soon as possible. But once there she meets a wonderfully kind group of villagers, including a handsome bookseller, who challenge her decision to make a quick sale.

What begins as a way to make money for her business in Seattle becomes an experience that uncovers family secrets and reveals the kindness of strangers. In England, Lucy just might rewrite her past in order to follow her heart.

The English Bookshop on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

The Paris Bookseller by Kerri Maher

But the success and notoriety of publishing the most infamous and influential book of the century comes with steep costs. The future of her beloved store itself is threatened when Ulysses‘ success brings other publishers to woo Joyce away. Her most cherished relationships are put to the test as Paris is plunged deeper into the Depression and many expatriate friends return to America. As she faces painful personal and financial crises, Sylvia—a woman who has made it her mission to honor the life-changing impact of books—must decide what Shakespeare and Company truly means to her. The Paris Bookseller on Bookshop.org*

The Paris Bookseller on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

The Little Paris Bookshop by Nina George

From the publisher: Monsieur Perdu calls himself a literary apothecary. From his floating bookstore in a barge on the Seine, he prescribes novels for the hardships of life. Using his intuitive feel for the exact book a reader needs, Perdu mends broken hearts and souls.

The only person he can’t seem to heal through literature is himself; he’s still haunted by heartbreak after his great love disappeared. She left him with only a letter, which he has never opened.

After Perdu is finally tempted to read the letter, he hauls anchor and departs on a mission to the south of France, hoping to make peace with his loss and discover the end of the story. Internationally bestselling and filled with warmth and adventure, The Little Paris Bookshop is a love letter to books, meant for anyone who believes in the power of stories to shape people’s lives.

The Little Paris Bookshop on Bookshop.org*

The Little Paris Bookshop on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

The Bookshop on the Corner by Jenny Colgan

From the publisher: Nina Redmond is a librarian with a gift for finding the perfect book for her readers. But can she write her own happy-ever-after? In this valentine to readers, librarians, and book-lovers the world over, the New York Times-bestselling author of Little Beach Street Bakery returns with a funny, moving new novel for fans of Nina George’s The Little Paris Bookshop.

Determined to make a new life for herself, Nina moves to a sleepy village many miles away. There she buys a van and transforms it into a bookmobile — a mobile bookshop that she drives from neighborhood to neighborhood, changing one life after another with the power of storytelling.

Nina discovers there’s plenty of adventure, magic, and soul in a place that’s beginning to feel like home… a place where she just might be able to write her own happy ending. The next book in this series is The Bookshop on the Shore.

The Bookshop on the Corner on Bookshop.org*

The Bookshop on the Corner on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

The Midnight Library by Matt Haig

From the publisher: Somewhere out beyond the edge of the universe there is a library that contains an infinite number of books, each one the story of another reality. One tells the story of your life as it is, along with another book for the other life you could have lived if you had made a different choice at any point in your life.

While we all wonder how our lives might have been, what if you had the chance to go to the library and see for yourself? Would any of these other lives truly be better?

In The Midnight Library, Matt Haig’s enchanting blockbuster novel, Nora Seed finds herself faced with this decision. Faced with the possibility of changing her life for a new one, following a different career, undoing old breakups, realizing her dreams of becoming a glaciologist; she must search within herself as she travels through the Midnight Library to decide what is truly fulfilling in life, and what makes it worth living in the first place.

The Midnight Library on Bookshop.org*

The Midnight Library on Amazon*

Nonfiction Books About Bookshops, Libraries, and Reading

(illustration above from Bibliophile by Jane Mount)

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop.org and Amazon affiliate links. If a product is purchased after linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps us to keep growing.

The post 10 Contemporary Novels About Bookstores and Libraries appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Novels About Books and Libraries by Women Writers

For those of us who love — or make that obsessed with —books, novels about books, bookstores, and libraries are the icing on the cake. Reading about books and bookish people in fictional narratives, might seem odd, but for the devout bibliophile, it makes perfect sense.

Presented here is a selection of novels by women writers whose stories that take place in bookstores or libraries. What could be cozier reading on a chilly day accompanied by a warm drink, a blanket, and a four-legged friend or two?

. . . . . . . . . .

The Personal Librarian by Marie Benedict

From the publisher: A remarkable novel about J. P. Morgan’s personal librarian, Belle da Costa Greene, the Black American woman who was forced to hide her true identity and pass as white in order to leave a lasting legacy that enriched our nation, from New York Times bestselling authors Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray.

Belle da Costa Greene is hired by J. P. Morgan to curate a collection of rare manuscripts, books, and artwork for his newly built Pierpont Morgan Library. Belle becomes a fixture in New York City society and one of the most powerful people in the art and book world, known for her impeccable taste and shrewd negotiating for critical works as she helps create a world-class collection.

The Personal Librarian tells the story of an extraordinary woman, famous for her intellect, style, and wit, and shares the lengths she must go to—for the protection of her family and her legacy—to preserve her carefully crafted white identity in the racist world in which she lives.

The Personal Librarian on Bookshop.org*

The Personal Librarian on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald

From the publisher: Set in 1959, Florence Green, a kindhearted widow with a small inheritance, risks everything to open a bookshop—the only bookshop—in the seaside town of Hardborough. By making a success of a business so impractical, she invites the hostility of the town’s less prosperous shopkeepers.

By daring to enlarge her neighbors’ lives, she crosses Mrs. Gamart, the local arts doyenne. Florence’s warehouse leaks, her cellar seeps, and the shop is apparently haunted. Only too late does she begin to suspect the truth: a town that lacks a bookshop isn’t always a town that wants one.

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald, published in 1978, was adapted to film in 2017, to mixed reviews by audiences and critics. Devotees of media about bookstores should nevertheless get some enjoyment from it.

The Bookshop on Bookshop.org*

The Bookshop on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

The Last Bookshop in London: A Novel of World War IIby Madeline Martin

From the publisher: August 1939 — London prepares for war as enemy forces sweep across Europe. Grace Bennett has always dreamed of moving to the city, but the bunkers and drawn curtains that she finds on her arrival are not what she expected. And she certainly never imagined she’d wind up working at Primrose Hill, a dusty old bookshop nestled in the heart of London.

Through blackouts and air raids as the Blitz intensifies, Grace discovers the power of storytelling to unite her community in ways she never dreamed—a force that triumphs over even the darkest nights of the war. This 2021 publication has become a bestseller and a reader favorite.

The Last Bookshop in London on Bookshop.org*

The Last Bookshop in London on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Booklover’s Library by Madeline Martin

From the publisher: A heartwarming story about a mother and daughter in wartime England and the power of books that bring them together, by the bestselling author of The Last Bookshop in London. In Nottingham, England, widow Emma Taylor finds herself in desperate need of a job.

She and her beloved daughter Olivia have always managed just fine on their own, but with the legal restrictions prohibiting widows with children from most employment opportunities, she’s left with only one option: persuading the manageress at Boots’ Booklover’s Library to take a chance on her with a job.

When the threat of war in England becomes a reality, Olivia must be evacuated to the countryside. In the wake of being separated from her daughter, Emma seeks solace in the unlikely friendships she forms with her neighbors and coworkers, and a renewed sense of purpose through the recommendations she provides to the library’s quirky regulars. But the job doesn’t come without its difficulties … As the Blitz intensifies in Nottingham and Emma fights to reunite with her daughter, she must learn to depend on her community and the power of literature more than ever to find hope in the darkest of times.

The Booklover’s Library on Bookshop.org*

The Booklover’s Library on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

The Little Paris Bookshop by Nina George

From the publisher: Monsieur Perdu calls himself a literary apothecary. From his floating bookstore in a barge on the Seine, he prescribes novels for the hardships of life. Using his intuitive feel for the exact book a reader needs, Perdu mends broken hearts and souls.

The only person he can’t seem to heal through literature is himself; he’s still haunted by heartbreak after his great love disappeared. She left him with only a letter, which he has never opened.

After Perdu is finally tempted to read the letter, he hauls anchor and departs on a mission to the south of France, hoping to make peace with his loss and discover the end of the story. Internationally bestselling and filled with warmth and adventure, The Little Paris Bookshop is a love letter to books, meant for anyone who believes in the power of stories to shape people’s lives.

The Little Paris Bookshop on Bookshop.org*

The Little Paris Bookshop on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

The Bookshop on the Corner by Jenny Colgan

From the publisher: Nina Redmond is a librarian with a gift for finding the perfect book for her readers. But can she write her own happy-ever-after? In this valentine to readers, librarians, and book-lovers the world over, the New York Times-bestselling author of Little Beach Street Bakery returns with a funny, moving new novel for fans of Nina George’s The Little Paris Bookshop.

Determined to make a new life for herself, Nina moves to a sleepy village many miles away. There she buys a van and transforms it into a bookmobile — a mobile bookshop that she drives from neighborhood to neighborhood, changing one life after another with the power of storytelling.

Nina discovers there’s plenty of adventure, magic, and soul in a place that’s beginning to feel like home… a place where she just might be able to write her own happy ending. The next book in this series is The Bookshop on the Shore.

The Bookshop on the Corner on Bookshop.org*

The Bookshop on the Corner on Amazon*

*These are Bookshop.org and Amazon affiliate links. If a product is purchased after linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps us to keep growing.

The post Novels About Books and Libraries by Women Writers appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 10, 2024

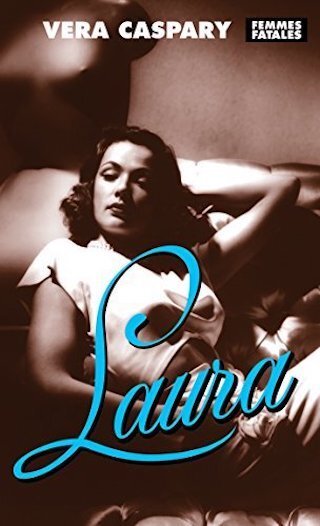

A Chosen Sparrow by Vera Caspary (1964)

“You survived. That’s important.”

“But who am I? An insignificant girl with no great talent. Why was I the one to be saved?”

He smiled a little. “Haven’t you heard that God heeds each sparrow’s fall?”

So many sparrows fell. Was God watching? Did He count them? Why was I chosen to live?”

(from A Chosen Sparrow by Vera Caspary, 1964)

This in-depth look at A Chosen Sparrow by Vera Caspary is excerpted from A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth ©2022. Reprinted by permission.

In a novel of compelling force the author traces the growth and development of Leni, a Jewish child who grew up in a Nazi prison. Knowing no other life, Leni strives to become like the “normal” people she encounters in her new world of freedom – post-war Vienna: the good citizens who wish to forget, the hypocrites who rationalize guilt, the penitents who try to atone the sins of the Nazis, the neurotics who hope to restore the days of perverse glory.

The very air of Vienna pulsates through the richly ornamented story – the customs, manners and old-world courtesy, and the charming lift of elegant shoulders, which shrug yesterday’s guilt from today’s pleasures.

Enchanted and corrupted by the brittle sentimentality and the splendors of this baroque world, Leni sees herself as the beautiful heroine of the classic fairytale. She seeks compensation in lush romanticism and shuns reality until the time comes when she is confronted by the specter of cruelty she knew in childhood, and the debt of the living (the chosen) to the six million dead. (—Front cover flap of the 1964 edition)

. . . . . . . . . .

Those who enjoyed Laura and anticipate another such novel of suspense will find Mrs. Caspary’s latest book far different but just as fascinating. The emphasis here is not entertainment only; the underlying purpose is to point up the disturbing fact that the evils of Nazism are still rampant in Europe today. The author’s imagination has evoked a strange heroine, a combination of the romantically old and the very modern new. (—Chicago Heights Star, April 12, 1964)

. . . . . . . . . .

As a novel about the survivor guilt of a Jewish girl growing up in Europe during and just after the time of the Nazis, A Chosen Sparrow by Vera Caspary was preceded among others by Elie Wiesel’s 1956 memoir Night, Olga Lengyel’s Five Chimneys (1959), both about their early lives in Auschwitz and Buchenwald, and by Meyer Levin’s Eva: A Novel of the Holocaust (1959), based on a true story, in which Eva passes for a while as a gentile, working as a maid in the home of an SS officer in Linz but is discovered and sent to Auschwitz.

Eva is set, like A Chosen Sparrow, in wartime and post-war Austria. Vienna-born Jewish writer Ilse Aichinger’s dreamlike Herod’s Children, first published in English in 1963, turns Levin’s and Caspary’s stories about the Jewish girl as outsider on their head: hers is a wartime story of a girl who feels like an outsider because she is not Jewish.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Vera Caspary