Nava Atlas's Blog, page 9

July 29, 2024

Laura and Eleanor Marx, translators of Karl Marx

It’s striking that two daughters of Karl Marx, Laura and Eleanor, became important early translators of his work. Marx (1818 – 1883), the German-born social and economic theorist and philosopher, is best known for The Communist Manifesto (co-authored by Friedrich Engels) and Das Kapital.

Laura Marx (1845 – 1911) was the second daughter of Karl Marx and Jenny von Westphalen was instrumental in translating Marx’s works from German into French. Her sister Eleanor Marx (1855-1898), the youngest daughter in the Marx family, was involved in translation from German into English.

. . . . . . . . . .

Laura Marx,translator of Karl Marx’s works into French

Jenny Laura Marx (also known as Laura Lafargue) was a German social activist, and a translator from German to French. Born in Brussels, Belgium, she was the second daughter of Karl Marx and Jenny von Westphalen, an activist and social critic in her own right. Laura moved with her parents to France, and then to Prussia, before the family settled in London in 1849.

Laura married French revolutionary socialist Paul Lafargue in 1868. They spent decades doing political work together, translating Karl Marx’s work into French, and spreading Marxism in France and Spain, while being financially supported by German philosopher Friedrich Engels.

Laura Marx died in 1911 in a suicide pact with her husband Paul Lafargue. She was 66, and he was 69. She left this letter, she wrote in part: “I die with the supreme joy of knowing that at some future time, the cause to which I have been devoted for forty-five years will triumph. Long live Communism! Long Live the international socialism!”

Laura Marx’s main translations were:

The Communist Manifesto (Manifeste du parti communiste, 1897) by Karl Marx and Friedrich EngelsRevolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany (Révolution et contre-révolution en Allemagne, 1900) by Karl MarxReligion, philosophie, socialisme (translated with Paul Lafargue, 1901) by Friedrich EngelsA Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (Contribution à la critique de l’économie politique, 1909) by Karl Marx. . . . . . . . . .

Eleanor Marx,translator of Karl Marx’s works into English

Eleanor Marx (1855-1898) was an English socialist activist and a translator from German, French and Norwegian to English. Known to her family as Tussy, she was the English-born youngest daughter Karl Marx and Jenny von Westphalen.

As a child, Eleanor Marx often played in in her father’s study while he was writing Capital (Das Kapital), the foundational text of what would become known as Marxism.

According to her biographer Rachel Holmes, “Tussy’s childhood intimacy with Marx whilst he wrote the first volume of Capital provided her with a thorough grounding in British economic, political and social history. Tussy and Capital grew together.” (quoted in Eleanor Marx: A Life, Bloomsbury, 2014).

Eleanor Marx became her father’s secretary at age sixteen and accompanied him to socialist conferences around the world.

In London, she met with French revolutionary socialist Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, who had fled to England after participating in the Paris Commune, a revolutionary socialist government that briefly ruled Paris in 1871.

Eleanor Marx took her own life at age 43 after discovering that her partner, English Marxist Edward Aveling, had secretly married a young actress the previous year.

Translations of Karl Marx’s work

Eleanor translated some parts of Capital from German to English. She also edited the translations of Marx’s lectures Value, Price and Profit (Lohn, Preis und Profit) and Wage Labour and Capital (Lohnarbeit und Kapital) for them to be published into books.

After Karl Marx’s death in 1883, Eleanor Marx published her father’s unfinished manuscripts and the English edition of Capital (1887).

Other translations

Eleanor translated Lissagaray’s History of the Paris Commune of 1871 (L’Histoire de la Commune de 1871). The English edition was published in 1876. She also translated literary works, including French novelist Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary in 1886.

Eleanor expressly learned Norwegian to translate Norwegian writer Henrik Ibsen’s plays, including An Enemy of the People (En Folkefiende) in 1888, and The Lady from the Sea (Fruen fra havet) in 1890.

. . . . . . . . . .

Source: A history of translation in 150 portraits

See also: 10 Lost Ladies of Literary Translation

Contributed by Marie Lebert. Reprinted by permission. Marie is a bilingual French-English translator. She has worked as a translator and/or librarian for international organizations and has written ebooks, articles and essays about translation and translators, ebooks, libraries and librarians, and medieval art. She holds a doctorate of linguistics (digital publishing) from the Sorbonne University, Paris, and a master of social science (society and culture) from the University of Caen, Normandy. Find more about women translators of the past at Marie Lebert.

The post Laura and Eleanor Marx, translators of Karl Marx appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 26, 2024

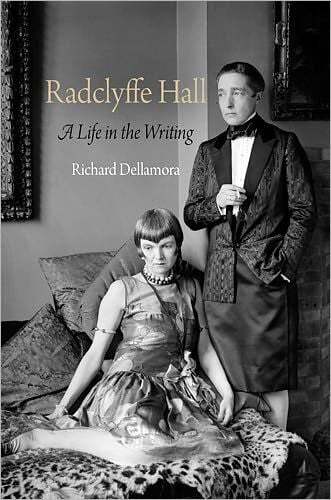

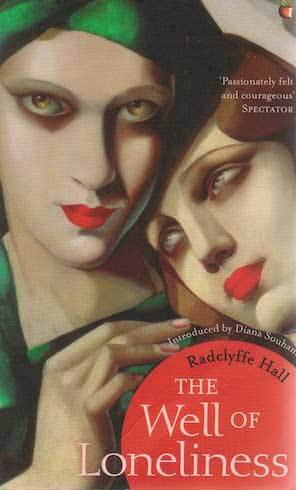

How to Burn a Book: Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness

In a forthcoming book, I argue that 1928, when The Well of Loneliness (Radclyffe Hall) and Lady Chatterley’s Lover (D.H. Lawrence) were published, was the year in which sex and sexuality were first described openly in the novel without any authorial moral judgement.

So the passage below, from The Well of Loneliness, would not have been a problem in 1928 if Stephen Gordon had been a man; but Stephen is a woman.

But her eyes would look cold, though her voice might be gentle, and her hand when it fondled would be tentative, unwilling. The hand would be making an effort to fondle, and Stephen would be conscious of that effort. Then looking up at the calm, lovely face, Stephen would be filled with a sudden contrition, with a sudden deep sense of her own shortcomings; she would long to blurt all this out to her mother, yet would stand there tongue-tied, saying nothing at all. (Radclyffe Hall, The Well of Loneliness, 1928)

By 1928 it was accepted that women in novels should have a sexual life – younger women and older women, women married and unmarried, modern women and flappers.

A sexual relationship in the 1928 novel could be inside or outside marriage, with the woman as an adulteress or as a single woman with an adulterous man. The novels of 1928 mostly did not judge. Fidelity was no longer considered a necessary virtue for women, just as it had never been for men; 1928 saw women in Great Britain get equal voting rights to men and novelists gave them equal sexual rights to match.

The only caveat was that a woman’s sexual life should not involve other women, though even then the serious literary critic was prepared to accept such a serious treatment of such a serious subject as Radclyffe Hall’s, especially if it made being gay (in the contemporary sense) seem the opposite of gay (in the 1928 sense), as it certainly did.

No one in The Well of Loneliness is having any fun and lesbianism is made to seem very gloomy indeed. Surely no bi-curious adolescent has ever been converted to the Sapphic cause by reading it.

The Well of Loneliness is often regarded as the first lesbian novel though this is an assertion which I have tried to refute elsewhere.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Positive early reviewsRadclyffe Hall’s fifth published novel, The Well of Loneliness was released as a very high-priced hardback in 1928 and treated with the same polite earnestness by the erudite reviewers in the heavyweight British literary magazines and newspapers as her previous four. All had received mostly respectful but unenthusiastic reviews in the “serious” press.

Hall and her partner Una Troubridge were well-known and accepted on the British literary and social scene despite always cross-dressing in a very provocative manner. Because of its high price, the novel was expected only to sell to these cognoscenti: educated, progressive people who would not be expected to be upset by its lesbian subject matter.

The early reviewers mostly treated it as a literary, even a philosophical work, rather than a provocatively sexual one – not that there is any sex in The Well of Loneliness. There is a sympathetic forward by the prominent sexologist Havelock Ellis.

Here are a couple of positive early, published before a sensational article in a tabloid newspaper stirred up a public outrage.

Miss Radclyffe Hall’s latest work, The Well of Loneliness (Cape, 15s. net) is a novel, and we propose to treat it as such. We therefore rather regret that it should have been thought necessary to insert at the beginning a “commentary” by Mr. Havelock Ellis to the effect that, apart from its qualities as a novel, it “possesses a notable psychological and sociological significance” as a presentation, in a completely faithful and uncompromising form, of a particular aspect of sexual life to the book as a work of art this testimony adds nothing; on the other hand, the documentary significance of a work of fiction seems to us small.

The presence of this commentary, however, points to the criticism which, with all our admiration for much of the detail, we feel compelled to express – namely, that this long novel, sincere, courageous, high-minded, and often beautifully expressed as it is, fails as a work of art through divided purpose. It is meant as a thesis and a challenge as well as an artistic creation. (Times Literary Supplement, August 2, 1928)

. . . . . . . . . .

The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall, is a very difficult work to review. Should I praise it, then I can literally hear the huge army of the narrow-minded hinting that I am in sympathy with its publication.

Should, on the other hand, I dismiss it as a novel written on a subject which is unmentionable, then I should condemn a work of considerable art; a story which is poignantly tragic to a degree; one of the few books I have ever read which illustrates the pitiful loneliness of sexual perversity as it is, apart from the pervert’s psychological and biological significance.

Every work of art, every undertaking designed in all seriousness, must, however, be viewed objectively. One may have little or no sympathy with the subject – but that is not the point. Criticism should not be prejudice disguised as erudition, though only too often it is thus bedecked. In any case, only the bigoted and the foolish seek to ignore an aspect of life which is as undeniable a fact as any concrete thing. To deny something because you dislike to confess that it is true belongs to the mentality of the undeveloped. (Richard King, The Tatler, August 15, 1928)

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from The Well of Loneliness

. . . . . . . . . .

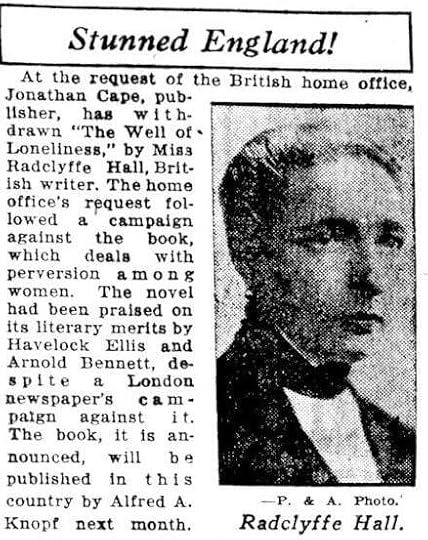

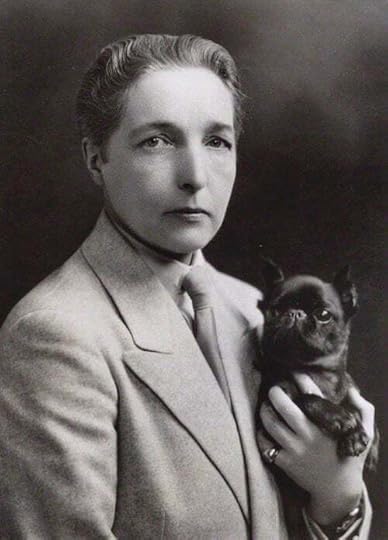

On August 19, 1928, the editor of the British tabloid paper The Sunday Express published a hysterical article entitled “The Book That Must be Suppressed” accompanied by a picture of Hall with her severe haircut, then called an Eton crop, dressed in a very masculine black smoking jacket with bow tie, holding a cigarette and looking out disdainfully.

Almost all press photographs of Hall from the time show her apparently wearing a man’s suit; in fact she nearly always wore a bespoke, tailored, knee-length skirt rather than trousers to match the tailored jacket but photos hardly ever showed below the knee.

In the Express article, the editor states that, “So far as I know, it is the first English novel which presents, in a completely faithful and uncompromising form, one particular aspect of sexual life as it exists among us today.”

The editor notes that the book is intended to present the lives of its characters sympathetically in order that they may be understood.

But he is not convinced. “This is the defence and the justification of what I regard as an intolerable outrage – the first outrage of this kind in the annals of English fiction.” The editor also says that artistic merit is no defense; quite the reverse in fact.

The adroitness and cleverness of the book intensifies its moral danger. It is a seductive and insidious piece of special pleading designed to display perverted decadence as a martyrdom inflicted upon these outcasts by a cruel society. It flings a veil of sentiment over their depravity. It even suggests that their self-made debasement is unavoidable, because they cannot save themselves.

In the most infamous quote in the article, the editor says, “I would rather give a healthy boy or a healthy girl a phial of prussic acid than this novel. Poison kills the body, but moral poison kills the soul. . . The book must at once be withdrawn.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Rebuttal to the negative reviewsAt least one serious British newspaper returned fire to the growing number of negative reviews, including this article titled “The Stunters and the Stunted.”

Will stunt journalism be allowed to cripple and degrade English literature? The question is raised by an article in a Sunday newspaper clamouring for the suppression of a novel, The Well of Loneliness, written by Miss Radclyffe Hall and published by Messrs. Jonathan Cape, Ltd, price 15s.

The book is the story of an abnormal woman. It is a restrained and serious psychological study. It is written “with understanding and practice, with sympathy and feeling,” says The Nation. It is “sincere, courageous, high-minded and often beautifully expressed,” says The Times Literary Supplement.

But the stunt journalist, writing for a Sunday newspaper which revels in the revelations of murderers and in the views and confessions of the unfortunate persons made notorious by the terrible ordeal of trial for murder, can see here an opportunity for sensation-mongering . . .

In this book there is nothing pornographic. The evil-minded will seek in vain in these pages for any stimulant to sexual excitement. The lustful sheikhs and cavemen and vamps of popular fiction may continue their sadistic course unchecked in those pornographic novels which are sold by the millions, but Miss Radclyffe Hall has entirely ignored these crude and violent figures of sexual melodrama. She has given to English literature a profound and moving study of a profound and moving problem. (Arnold Dawson, The Daily Herald, August 20, 1928)

The British Establishment very quickly came down on the side of the tabloids; the British publishers offered to withdraw it just a few days later in a letter to The Times – knowing, however, that they could quickly reprint it in France and sell it there without fear of censorship.

Sir, – We have today received a request from the Home Secretary asking us to discontinue publication of Miss Radclyffe Hall’s novel: “The Well of Loneliness.” We have already expressed our readiness to fall in with the wishes of the Home Office in this matter, and we have therefore stopped publication.

I have the honour to be your obedient servant,

Jonathan Cape (for and on behalf of Jonathan Cape, Ltd), August 23, 1928

Just a few days later, another British tabloid newspaper, The People, also jumped on the censorship bandwagon, claiming that it was them who had originally asked for a ban of this “revolting” book.

The “secret novel” to which “The People” drew attention last week has been withdrawn by the publishers at the request of the Home Secretary.

While other newspapers were trying to make up their minds about the book, “The People” had already decided that the revolting aspect of modern life with which it dealt made its publication undesirable.

Further, “The People” announced exclusively, a week ago, that the novel, and the banning of it, were under official consideration.

The Home Secretary’s acceded request for the books withdrawal is a triumphant vindication of “The People’s” judgement. (The People, August 26, 1928)

Banning and, in the case of The Well of Loneliness, literally burning copies of a book is always a great way to increase sales, as the writer of a letter to another newspaper very quickly found.

I happened to visit two well-known London bookshops today, and I had not been in either five minutes before I heard mention made of Miss Radclyffe Hall’s suppressed book.

In one shop a customer enquired whether a copy could still be obtained through the circulating library department, and was told that the probable policy of the library would be to withdraw all copies in circulation as soon as they were returned, and issue no more.

In the other shop a customer was expressing at some length to an assistant his views on the unfairness, not so much of the suppression, as of the methods adopted to bring it about. (Yorkshire Post, August 28, 1928)

Nevertheless, even some of the more serious, upmarket British journals also jumped swiftly onto the ban-the-book bandwagon, including The Tatler which only two weeks earlier had reviewed The Well of Loneliness fairly and sympathetically.

The Home Secretary is to be congratulated on having secured the suppression of “The Well of Loneliness” without setting the Public Prosecutor in action. The book is mischievous and unwholesome; but a prosecution would certainly have failed, because there is not an indecent word or an obscene image in it from the first to the last page.

The police authorities are well aware that prosecutions for sexual abnormality, even when a conviction is obtained, do more harm than good, and always, if they can, avoid proceedings . . . The female “invert,” up to now regarded as a hysterical half-wit, is by Miss Radclyffe Hall described as the victim of a pre-disposition or pre-natal taint.

Possibly, but is not the same true of the male invert? Happily the question has been settled by the good taste and common sense of Messrs. Cape, who agreed at once to withdraw the book. (The Tatler, September 5, 1928)

The Home Secretary in question was the aristocratic Sir William Joynson-Hicks, Viscount Bedford, who had been described as “the most prudish, puritanical and protestant Home Secretary of the twentieth century.” Jix, as he was known, was loved by the tabloid press but treated as a laughing stock by the serious journals.

As Home Secretary he cracked down on many aspects of the Roaring Twenties of which he disapproved, including the existence of London nightclubs, many of which he ordered the Metropolitan police to raid. Hicks said he was trying to stem “the flood of filth coming across the Channel,” banning the works of D. H. Lawrence whose Lady Chatterley’s Lover was published privately in 1928 in Italy partly because of him – Jix forced the publishers to issue an expurgated version in Britain.

He also clamped down on books on birth control and a translation of Boccaccio’s admittedly raunchy The Decameron which nevertheless dates from the 1350s. Hicks even opposed the revision of The Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer in his own book The Prayer Book Crisis, published in May 1928.

However, despite his disapproval of the “modern woman,” Hicks did personally drive through Parliament the Equal Franchise Act of 1928 which gave women equal voting rights to men – rights they unhesitatingly used to unseat Hicks’ own Conservative party in the General Election of the following year.

Fellow writers try to appeal to reason

Fellow writers generally agreed that books should not be banned because of their subject matter. British novelist E. M. Delafield (whose 1928 novel What is Love? has contrasting heroines in Vicky and Ellie who are reminiscent of Vanity Fair’s Becky and Amelia but with more of a sex life) gave a talk to a woman’s group in Leeds while the controversy was raging in which she directly addressed the issue.

Virginia Woolf, whose pansexual novel Orlando was also published in 1928, was tepid about The Well of Loneliness, though it was the literary style she disapproved of rather than the content. She wrote in a letter, “At this moment our thoughts centre upon Sapphism. We have to uphold the morality of that Well of all that’s stagnant and lukewarm and neither one thing or the other; The Well of Loneliness.”

And in another letter, “The dulness [sic] of the book is such that any indecency may lurk there — one simply can’t keep one’s eyes on the page.” She also wrote in her diary about the publisher’s appeal in court of “The pale tepid vapid book which lay damp and slab all about the court.”

However, she and E. M. Forster attended the appeal together and wrote a letter to The Nation in support.

The Well of Loneliness is restrained and perfectly decent, and the treatment of its theme is unexceptionable. It has obviously been suppressed because of the theme itself. May we add a few words on this point?

The subject-matter of the book exists as a fact among the many other facts of life. It is recognised by science and recognisable in history. It forms, of course, an extremely small fraction of the sum-total of human emotions, it enters personally into very few lives, and is uninteresting or repellent to the majority; nevertheless it exists, and novelists in England have now been forbidden to mention it by Sir W. Joynson-Hicks.

May they mention it incidentally? Although it is forbidden as a main theme, may it be alluded to, or ascribed to subsidiary characters? Perhaps the Home Secretary will issue further orders on this point.

Seizure of and destruction of printed copies proceeds

Despite the support of well-known writers, the publisher’s appeal against the seizure of two hundred and forty seven copies of the book and the decision to destroy them failed; the appeal judge made no attempt to hide his prejudice, as reported in another tabloid newspaper.

In giving the decision of the Court, Sir Robert Wallace said there were plenty of people who would not be depraved or corrupted by reading this book, but there were also those whose minds were open to such immoral influences.

The view of this Court is that this book is very subtle, insinuating in the theme it propounds, and much more dangerous because of that fact.

It is the view of this Court that this is a most dangerous and corrupting book . . . that it is a disgusting book, a book which is prejudicial to the morals of the community, and in our view the order made by the magistrate was a fair one, and the appeal is dismissed with costs. (Daily Mirror, December 15, 1928)

After the appeal court decision, the seized copies of the novel were very quickly burned “in the King’s furnace” – five years before the first fascist book burnings in Germany – a notorious occasion reported, mostly approvingly, in the popular press.

All the seized copies of Miss Radclyffe Hall’s novel, “The Well of Loneliness,” will early this week help to warm the many rooms of New Scotland Yard.

It is understood that the copies of the book, which are now under lock and key, will be fed into the furnaces in the basement of New Scotland Yard and be destroyed. The destruction of the books will be conducted under the supervision of at least one officer of high rank. (Aberdeen Press and Journal, December 17, 1928)

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Radclyffe Hall

(photo, ca 1930, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Meanwhile, The Well of Loneliness had swiftly been reprinted in Paris and was openly and very successfully on sale there, as attested by a couple of sympathetic female journalists, including the Paris correspondent of the very Tatler which had just the week earlier condemned the book.

At my flat in Paris I found a copy of Radclyffe Hall’s “Well of Loneliness” and, incidentally, many thanks to the sender whose handwriting on the address I did not recognise! I read it from cover to cover with breathless interest, and very soon, no doubt, I shall read it again.

Rarely has Paris “been so well done,” and not only the pages referring to a certain Paris and a certain milieu of that certain Paris, but the whole atmosphere of my beloved city. I am told that this novel has started a certain amount of yapping, and this seems curious to me, for I have read several notices of it in the columns of such “pillars of the Press” as “The Sunday Times,” “The Morning Post,” “The Saturday Review,” and “The Telegraph,” which were, in most cases, understanding and appreciative.

Strange the difficulty that some people have to keep calm when any pitiful aspect of sexual life is discussed. Pitiful? Why, of course. No one deliberately wants to be uncomfortable, and anything abnormal is dashed uncomfy. (“Priscilla in Paris,” The Tatler, September 12, 1928)

And early the next year the Paris correspondent of the prestigious New Yorker, a journalist and novelist – and lesbian – herself, reported that the novel was openly on sale and highly popular there.

It may be interesting to know that Radclyffe Hall’s novel about Lesbians, The Well of Loneliness, though banned in England and under fire in New York, has escaped condemnation in France, where it now enjoys a local printing. Its biggest daily sale takes place from the news vendor’s cart serving the deluxe train for London, La Flèche d’Or, at the Garde du Nord.

The price is one hundred and twenty-five francs a copy. For first English editions, dealers in the Rue de Castiglione offered to buy for as high as six thousand francs, and to sell at as high as anything you are silly enough to pay. (Janet Flanner, ‘Letter from Paris,’ New Yorker, 1929)

In Flanner’s native New York however things did not go so well for the Well, as reported in the New York Times for February 22, 1929.

Magistrate Hyman Bushel in the Tombs Court ruled yesterday that the book “The Well of Loneliness” by the Englishwoman writer Radclyffe Hall is obscene and was printed and distributed in this city in violation of the penal law. He ordered a complaint drawn against the Covici, Friede Corporation, American publishers of the book . . .

Mr. Friede, who was in court when the decision was announced, was promptly arrested, but freed in $500 bail, which he furnished in cash. No bail was fixed in the case of the corporation. Hearings were held several weeks ago by the magistrate in the West Side Court in a proceeding started by John S. Simner, superintendent of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, who had seized 855 copies of the novel at the publisher’s office.

Friede had gambled big by taking out a huge $10,000 dollar loan to buy the US publication rights from Cape in England but he could still easily afford to pay the $500 bail, which he probably did with a triumphant smile, since he had already sold 100,000 copies of the paperback at $5 each – double the normal price of a paperback novel at the time.

As Una Troubridge said, “What nobody foresaw was that the re-publication in Paris would be followed by translation into eleven languages, by the triumph of the book in the United States of America and the sale of more than a million copies.” Censorship works in the short run, but rarely in the censor’s favor.

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture: Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth-Century Literary Eroticism; Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938; High Collars & Monocles: 1920s Novels by British Female Couples; and A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young Adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

The post How to Burn a Book: Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 25, 2024

Ban if You Can: Banning & Censorship in Contemporary India

India’s celebrated diversity and, by and large, a sense of peaceful co-existence has taken a severe hit since the past decade. This has been linked with the rise of right-wing Hindutva in politics, which has bred a sense of injured pride in the Hindu majority accompanied by a phobia created about the threat from minorities, most of all Islam.

The myths being perpetrated include the uncontrolled rise in the Muslim population, as also the physical threats that could result from this change in demographics.

There is no data to substantiate these claims but with the power of social media and its ability to make a piece of fake news viral, nobody seems to care anymore to do a fact check and most people are quite content to believe all the lies that land on their telephones, day in and day out.

At such a juncture, all forms of media including books, have the power to influence people and change minds. Hence, governments and powerful religious groups are very sensitive about certain topics, which they feel the public should be denied access to. With this started the history of bans in India, though it is not as if other more progressive countries have not done their share of banning.

Book banning in IndiaAubrey Menen and Salman Rushdie

One of the earliest books to be banned in India was Rama Retold. Written in 1954 by the British writer Aubrey Menen as a spoof with a dose of humor, it clearly did not appeal to the funny bone of Indians and the book was prevented from being imported into India.

The author, labeled as a satirist, novelist and theatre critic, was probably much more, as he took pot shots at all the characters in the Ramayana, including the one who is said to have authored the Ramayana, Valmiki.

In today’s India, this retelling might have brought him death threats and though he chose to make India his home in later life, he fortunately didn’t live to see this phase of India’s authoritarian grip on the written and spoken word.

Sometimes, as it happened with Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, it is the fear of communal conflagrations that can result in a ban. Even though the book made it to the Booker shortlist, the government headed by the Congress party under Rajiv Gandhi, decided to play safe and enforce a ban on the book.

In 1989, there was a fatwa put on Rushdie by Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran and the author had to go into hiding for long years. It is tragic how Rushdie nearly paid with his life in August 2022, despite years having gone by, since the fatwa was lifted.

One is not sure whether the misguided assailant had even read the book. Rushdie’s cup of woes did not end with the Satanic Verses in India.

His Moor’s Last Sigh, also came in for criticism and protests in the state of Maharashtra, as one of the characters seemed to bear a resemblance to Balasaheb Thackeray, the founder of a political party called the Shiva Sena. That Thackeray started his career as a journalist, makes this all the more ironic.

Dan Brown

When it came to Dan Brown’sThe Da Vinci Code, it was India’s Christian population that rose up in protest claiming that the book had made profane statements on Christ.

Despite selling millions of copies worldwide, after the movie version was released in 2006, the book was prevented from being “sold, distributed and read.” The movie also came in for a ban in several states of India, where the Christian population were located in large numbers.

Arundhati Roy

In a country steeped in patriarchy, many women authors have had to face criticism of their books, if not outright bans. Arundhati Roy, who won the Booker Prize for her God of Small Things, had to fight a case, as a lawyer in Kerala was offended by her book with its reference to an upper caste Kerala woman cohabiting with a man from a lower caste.

But truth is stranger than fiction. Even today the papers are full of stories of families attacking couples belonging to different castes, with some of them ending in the tragic death of one or both.

Indian patriarchy strangely extends across the different religions that have incubated here. At the heart of this sense of ownership of a woman is likely linked to an ancient lawmaker, Manu, who in his Manusmriti, has clearly spoken of a woman as a piece of property and drawn the most demeaning parallels about her position in society.

That the present Union government is trying to bring in the Manusmriti as a part of its newly amended criminal laws, has led to a lot of protests, including from those of the legal fraternity. If Manu’s code is revived by this government, it will certainly be back to the dark ages for the women of India, especially those who live in the villages and small towns, with less access to education and an already internalized acceptance of patriarchy.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

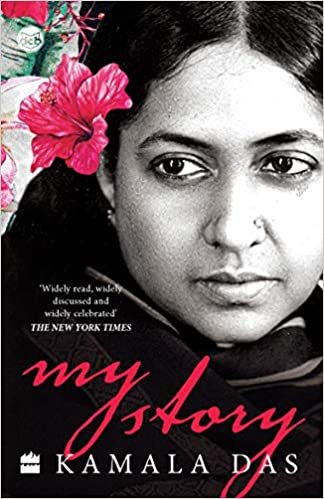

Kamala Das

Another woman author who had to face a great deal of censure was the Malayalam author, Kamala Das, who wrote fearlessly about a woman’s body and its needs.

Her writings shook society and Das had to face a huge backlash from an orthodox society. But she was unfazed and continued writing till her last breath. Even today, her writings make up a big part of feminist Indian writing.

Poet, author, social scientist and feminist Kamla Bhasin put it succinctly when she observed, “My honour is not in my vagina.” The tragedy of patriarchy is in its belief that this is where a woman’s honor vests.

In recent times, the politics surrounding food have also led to the banning of movies, including those available for live streaming. While propaganda films have managed to garner awards in the last ten years, the right-wing ecosystem seems to exercise strict control about what films are suitable for viewing by the Indian public.

A contemporary film bannedIt’s enough for just one person to see a movie, feel outraged by it and have it banned by posting about it on social media. One such film, which was removed from Netflix was Annapoorani: The Goddess of Food. The furor over “hurting Hindu religious sentiment,” resulted in its removal at its “licensor’s request.”

The gist of the story revolves around actor, Nayanthara, aspiring to become a cook by learning to eat and prepare non-vegetarian dishes, which are taboo in a Brahmin home. It’s another story that many Indians from the upper castes have broken this taboo, but of course this is again a question of patriarchy rearing its head in that a woman does not have a right over her food choices either.

The role of India’s government in banning and censorshipIn earlier times, governments banned books or movies in anticipation of trouble, or because they felt jittery over certain allusions in books and the popular media.

Today the government has managed a huge stranglehold on the dissemination of information. The mainstream media has largely become a propaganda machine for the government and has earned for itself the title of Godi or Lap Media.

Many activists find themselves in jail over trumped up charges of spreading fake news. The independent media is always up for censure with several journalists feeling threatened about how they cover news. Even stand-up comics have not been spared, with many of their shows being called off because someone protested during the event, or prior to the staging.

The author Aubrey Menen, mentioned earlier, put it best in his closing lines of Rama Retold, which he reserved for his favorite character, Valmiki:

“There are three things, which are real: God, human folly and laughter. Since the first two pass our comprehension, we must do what we can with the third.”

It is sad that Indians seem to have missed out on the joys of laughing at their own foibles because at the end of the day, it is just the fact of having a very thin skin, especially our politicians.

Contributed by Melanie P. Kumar: Melanie is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

The post Ban if You Can: Banning & Censorship in Contemporary India appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 22, 2024

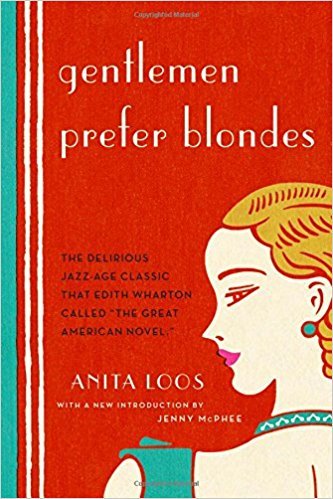

But Gentlemen Marry Brunettes, the sequel to Gentlemen Prefer Blondes

Anita Loos’ wildly successful 1925 novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was followed by a sequel, But Gentlemen Marry Brunettes. Published in the U.S. in 1927 and in England in 1928, it continued the adventures of the free, independent but ditzy Lorelei Lee and her friend, Dorothy Shaw.

Despite her misspellings and malapropisms, Lorelei is very much the modern, free 1920s woman and though she is deliberately written to appear as a “dumb blonde,” she is actually extremely sharp (and beautifully written in a virtuoso performance by Loos).

Lorelei wants us to understand that she is not a gold digger but a “diamond collector” and her faux-naïve monologue – the novel purports to be Lorelei’s diary – contains many other gems that sound in retrospect as though they were written specifically for Marilyn Monroe, even though Monroe was only two years old when the novel was published:

“Diamonds are a girl’s best friend.”“Money may not buy happiness, but it sure does make it easier to be glamorous.”“Being blond means never having to say sorry for being fabulous.”Not that Lorelei intends to be dependent on a man —“Why chase after a man when you can chase after a job and have both?” And, as she says, “success is the best revenge, especially when you’re wearing a stunning dress.”

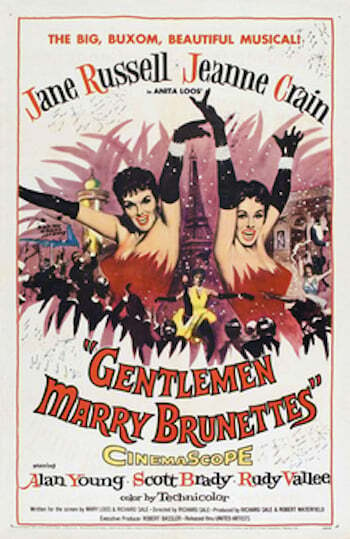

The famous 1953 film adaptation of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, starring Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell, bears only passing resemblance to the original book, and 1955’s Gentlemen Marry Brunettes film, starring Jane Russell and Jeanne Crain as Dorothy Shaw’s daughters, even less so.

. . . . . . . . . .

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1925 novel)

by Anita Loos

. . . . . . . . . .

Like the best of modern 1920s women, Lorelei doesn’t need to be saved, she just needs a man to spend his savings on her. “I don’t need a knight in shining armor, I need a man who can keep up with me.”

And: “I refuse to be just another pretty face. I’m here to own the room and conquer the world.”

There is also a quote in the original novel that gives the clue to the incomplete nature of the book’s title, “Gentlemen may prefer blondes, but smart men prefer a blonde with a brain.”

At the beginning of this sequel, Lorelei tells us that she is “going to begin a diary again, because I have quite a little time on my hands.” The new diary, like the one in the previous novel, is full of the delightful non-standard spellings and howlers as the first one – Loos’ technical skill is severely underrated in my opinion.

In the new diary, Lorelei’s foil Dorothy is back as her sounding board. “I mean sometimes Dorothy becomes Philosophical, and says something that really makes a girl wonder how anyone who can make such a Philosophical remark can waste her time like Dorothy does.”

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Anita Loos

. . . . . . . . . .

Now married to Henry, who is of “the wealthy classes,” Lorelei says that “practically every married girl ought to have a career if she is wealthy enough to have the home life carried on by the servants.” And especially, as in her case, if she is married to husband like Henry, who is “quite a homebody and, if the girl was a homebody to, she would encounter him quite often.” So

Lorelei tells her diary that she needs to get out of the house and “to meet brainy gentlemen who have got ideas on the outside.”

The first career Lorelei tries is the cinema, where she stars in “a superproduction based on sex life in the period of Dolly Madison” [wife of James Madison, fourth president of the United States at the beginning of the 1800s].

The production team argue as to whether it should be full of “Psychology,” mob scenes and ornamental sets or full of a “great moral lesson,” as Henry wants. “I did not care what it was full of, as long as it was full of plenty of cute scenes where the leading man would chase me round the trunk of a tree and I would peek out at him, like Lillian Gish.”

Well, when our cinema was finished the title turned out to be “Stronger than Sex,” which was thought up by quite a bright girl in Mister Goldmark’s suite of offices. And the great moral lesson was, that girls could always help it, if they would only think of Mother.

Lorelei has a baby

But Lorelei becomes pregnant and has to give up her career in the cinema. Dorothy says that “a kid that looks like any rich father is as good as money in the bank,” and Lorelei is happy to be pregnant so soon after the marriage because “the sooner a girl becomes a Mother after the ceremony, the more likely it is to look like Daddy.”

Dorothy advises her however to only have one “kiddie” because she thinks that “one is enough of almost anything that looks like Henry. But Dorothy has no reverents for Motherhood.”

Henry wants to stay in Philadelphia to have the baby because, as Lorelei says, in Philadelphia he is quite “promanent,” whereas Lorelei is desperate to move to New York, even knowing that “the riskay things that Henry can think up may intreege the suberbs of Philadelphia, but they really would not be such a thrill in New York.”

She asks a New York friend, who is “very, very promanent” to get invitations for Henry to join various societies. It works; “when Henry started in to receive all of those invitations, it made him feel very good to think that his promanents had reached New York.”

She decides to “become literary”After the baby comes, Henry settles “quite a large settlement on me.” But Lorelei is bored and soon starts to think of a new career. “I decided not to produce any more cinemas, because ‘Stronger Than Sex’ went right over people’s heads and became a financial failure. So I decided to become literary instead and spend more time in some literary envirament, outside the home.”

Lorelei starts with probably the most literary environment in New York, the Algonquin Hotel, still the real-life home in 1928 to Dorothy Parker and the Vicious Circle; she goes for lunch and charms the waiter into sitting them next to the famous writers.

After Dorothy gets bored and leaves, Lorelei is invited to sit at the table of “all the geniuses” by one of them, who says to his companions, “you are always discovering a Duse, or a Sapho or a Cleopatra every week, and I think it is my turn. Because I have discovered a young lady who is all three rolled into one.”

Lorelei has already said of this man that he “is always falling in love with some new girl” so she is not surprised when he says he has “noted my reverants for everything they said and he finally told me that he realised I had more in me than I looked, so he issued me an invitation to come to luncheon every day.”

But Lorelei has already decided to join another organization, the Lucy Stone League – a real-life women’s establishment founded in 1921 that advocated women keeping their name after marriage. Lorelei wants to be able to “write my book without my identity being sunk by having the name of a husband to crush me.”

Because a girl’s name should be Sacred, and when she uses her husband’s it only sinks her identity. And when a girl always insists on her own maiden name, with vialents, it lets people know that she must be important some place or other.

And quite a good place to insist on an unmarried name, is when you go to some strange hotel accompanied by a husband. Because when the room clerck notes that a girl with a maiden name is in the same room with a gentleman, it starts quite a little explanation, and makes a girl feel quite promanent before everybody in the lobby.

But Dorothy said I had better be careful. I mean she says that most Lucy Stoners do not really worry the room clerck, because they are generally the type that are only brought to hotels on account of matrimony.

But Dorothy said that when Henry and I waltz in and ask for a room with my maiden name the clerck would probably get one good look at me, and hand Henry a room in the local jail for the Man act [the Mann Act of 1910 criminalized the transportation of “any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose”].

“I do not listen to any advice about literature from a girl like Dorothy. And so I joined it.”

Lorelei’s novel and Dorothy’s misadventures

Lorelei decides to write her novel about Dorothy, which “is not going to be so much for girls to resemble, as it is to give them a warning what they should stop doing.” Dorothy turns out to have had a very interesting childhood, starting from “quite a low enviranment,” and though she has improved herself to the extent of living at the Ritz, Dorothy still “does nothing but fall madly in love with the kind of gentlemen who were born without money and have not made any since.”

By the age of sixteen Dorothy has ended up working among grifters and tricksters in a “Carnaval Company” but still seems to be a virgin, “without the subjeck of ‘Life’ being brought to turn notice. Because when I was only 13, I sang in our church quire, and practically every boy in our quire had at least mentioned the subjeck and some of them had done even more.”

Lorelei’s reasoning for this is that in a Carnaval Company “nothing is Sacred,” and people can make jokes about matters of Life. “But Love is so Sacred in a church quire, that they never even mention it above a whisper, and it becomes more of a mistery. And when a thing is a mistery, it is always more intrieging.”

So for Lorelei growing up there was ironically “quite a lot more Love going on” than in Dorothy’s traveling circus.

Eventually, Dorothy has come to the conclusion that it is time that she gave the “love racket” a whirl, “and find out for herself if it had really been over-advertised.” Her skepticism is not surprising to Lorelei, given that she lives in the company of people whose whole lives involve swindling the public. But when Dorothy “decided to do it,” and “find out about ‘Things,’” the only person she could think of who might be interested is the “Deputy Sherif” so she gives him “a kind word.”

After going with him to the cinema, Dorothy decides to let the Deputy Sherif kiss her, Dorothy’s first kiss. It is a big disappointment. “Dorothy says she felt like a little boy who had just found out that Santy Clause was the Sunday School Superintendant.”

Dorothy passes up the chance to marry into the Deputy Sherif’s wealthy family and runs away to join an acting company run by a Frederik Morgan, having decided on her new career after seeing Morgan playing the lead in “The Tail of Two Cities,” after which “the whole subjeck of Sex Appeal had taken on quite a new aspeck to Dorothy. And Dorothy says she decided that all of the things the Deputy Sherif had tried on her, that only made her squirm, would be a Horse of a different color with that leading man in the role.”

So Dorothy accompanies Mr Morgan up to his apartment where he tells her the story of “his Life,” which includes the fact that he has a wife but had to send her away because “an Artist must use all of his feelings to develop his temprament by.”

And then he told Dorothy that she would probably turn out to be an Artist herself, as soon as she got her temprament developed and found out about Life.

And he said that he himself would be willing to teach her about Life and give her all his ade. And he told her it was really quite a large opertunity for a girl like her, when society women with strings of pearls were after it. So after he finished his recomendation, he asked Dorothy whether she would like to go home, or take off her things and stay awhile.

So Dorothy took off her things.

But it turns out that learning about Life does not improve Dorothy’s acting “temperament” and, worse, it “did not turn out to be so enjoyable to her, after all. I mean, Dorothy is never at her best in a tate-a-tate.”

Both parties agree to “let the matter drop,” but Dorothy continues to act and then gets a job at the Follies, where she impresses a millionaire polo player, Charlie Breene. But the rich boy bores her and she gives him the slip. “And Dorothy says that running out on millionaires has been her specialty ever since.”

So, despite impressing the polo player’s millionaire society mother, Dorothy runs off with a “saxaphone player” she met at the Follies. The marriage goes wrong for Dorothy on the way to the wedding, when she sees her future husband Lester in the daylight for the first time and is not impressed; she spends the next several chapters trying to get away from him, with the ostensible help of the Breene family’s money and lawyer, during which Dorothy goes on a trip to Paris.

The polo player’s family money had actually been secretly supporting Lester and when the money stops, he blackmails the Breenes’ lawyer into paying him $10,000 to go away. The upshot is that Dorothy is now free to marry Charlie so her worried family pay the lawyer to frame her on a drugs charge and the police lock her up.

But Lorelei comes to her rescue and then Charlie reappears, having been cut off from his family’s money and got himself sober. Dorothy falls in love and, reader, she married him.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The 1955 film, Gentlemen Marry Brunettes,

has little in common with the 1927 original novel

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture: Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth-Century Literary Eroticism; Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938; High Collars & Monocles: 1920s Novels by British Female Couples; and A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young Adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

The post But Gentlemen Marry Brunettes, the sequel to Gentlemen Prefer Blondes appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 21, 2024

65 Witty, Bawdy Mae West Quotes

Mae West (1893 – 1980) earned international fame as an actress and singer, but she was also a talented playwright and screenwriter. In fact, it was she who wrote all the clever and sometimes bawdy quips that were her stock in trade. This collection of Mae West quotes gathers some of her wittiest and best known.

At one point in the 1930s, Mae was the highest-earning women in the U.S. Constantly doing battles with censors, she famously said, “I believe in censorship. I made a fortune out of it.” Mae created her iconic persona, and behind it was her desire to poke holes in stodgy convention and hypocrisy

The American Film Institute named her the 15th greatest female screen legend, an honor she richly deserved. When her film career wound down, she continued to write books and plays.

“You only live once, but if you do it right, once is enough.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There are no good girls gone wrong — just bad girls found out.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I generally avoid temptation unless I can’t resist it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Every man I meet wants to protect me. I can’t figure out what from.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I wrote the story myself. It’s about a girl who lost her reputation and never missed it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Between two evils, I always pick the one I never tried before.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Sex is like good bridge. If you don’t have a good partner, you’d better have a good hand.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“When I’m good, I’m very good, but when I’m bad, I’m better. ”

. . . . . . . . . .

Mae West: The Surprisingly Literary Star of Stage & Screen

. . . . . . . . . .

“I’ll try anything once, twice if I like it, three times to make sure.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I’m single because I was born that way.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Good girls go to heaven, bad girls go everywhere.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I’m no model lady. A model’s just an imitation of the real thing.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Ladies who play with fire must remember that smoke gets in their eyes.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A dame that knows the ropes isn’t likely to get tied up.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Marriage is a fine institution, but I’m not ready for an institution.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It’s not the men in your life that matters, it’s the life in your men.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Discarded lovers should be given a second chance, but with somebody else.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Sex is an emotion in motion.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I never said it would be easy, I only said it would be worth it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Cultivate your curves — they may be dangerous but they won’t be avoided.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Those who are easily shocked should be shocked more often.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Too much of a good thing can be wonderful!”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I never worry about diets. The only carrots that interest me are the number you get in a diamond.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It is better to be looked over than overlooked.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I used to be Snow White, but I drifted.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Anything worth doing is worth doing slowly.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Don’t keep a man guessing too long — he’s sure to find the answer somewhere else”

. . . . . . . . . .

“You are never too old to become younger!”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Love thy neighbor — and if he happens to be tall, debonair and devastating, it will be that much easier.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Women like a man with a past, but they prefer a man with a present.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“Look your best — who said love is blind? ”

. . . . . . . . . .

“His mother should have thrown him away and kept the stork.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A woman in love can’t be reasonable — or she probably wouldn’t be in love.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“To err is human — but it feels divine.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I have found men who didn’t know how to kiss. I’ve always found time to teach them.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If a little is great, and a lot is better, then way too much is just about right!”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Men are my hobby, if I ever got married I’d have to give it up.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Getting married is like trading in the adoration of many for the sarcasm of one.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“When women go wrong, men go right after them.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Good women are no fun … The only good woman I can recall in history was Betsy Ross. And all she ever made was a flag.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I’ve no time for broads who want to rule the world alone. Without men, who’d do up the zipper on the back of your dress? ”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Love conquers all things except poverty and toothache.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I never loved another person the way I loved myself.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She’s the kind of girl who climbed the ladder of success wrong by wrong.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“JUDGE: Are you trying to show contempt for this court?

MAE WEST: I was doin’ my best to hide it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Women with pasts interest men because they hope history will repeat itself.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I only read biographies, metaphysics and psychology. I can dream up my own fiction.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I’m a woman of very few words, but lots of action.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“An ounce of performance is worth pounds of promises.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A man’s kiss is his signature.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Everyone has the right to run his own life — even if you’re heading for a crash. What I’m against is blind flying.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“Love isn’t an emotion or an instinct — it’s an art.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I’ve been in more laps than a napkin.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I see you’re a man with ideals. I better be going before you’ve still got them.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It isn’t what I do, but how I do it. It isn’t what I say, but how I say it, and how I look when I do it and say it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I saw what a mess a lot of people could make of their lives when they’re smitten. Some of them go temporarily insane. They find a person who they think holds the key to their happiness — the only key to their happiness … My work has always been my greatest happiness.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A hard man is good to find.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Goodness, what beautiful diamonds!” “Goodness had nothing to do with it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Ten men waiting for me at the door? Send one of them home, I’m tired.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If I had known I was going to live this long, I would have taken better care of myself.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Men are all alike — except the one you’ve met who’s different.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I’ve been rich and I’ve been poor, and rich is better.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I only like two kinds of men, domestic and imported.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“What’s the good of resisting temptation? There’ll always be more.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Sex with love is the greatest thing in life. But sex without love — that’s not so bad either.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Gentlemen prefer blondes, but who says blondes prefer gentlemen?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“You only live once, but if you do it right, once is enough”

More about Mae West

Mae West biography Mae West: Dirty Blonde (American Masters, PBS)The Best of Mae West (film clip compilation)The post 65 Witty, Bawdy Mae West Quotes appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 17, 2024

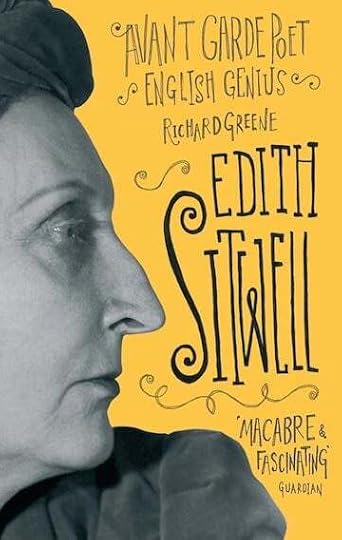

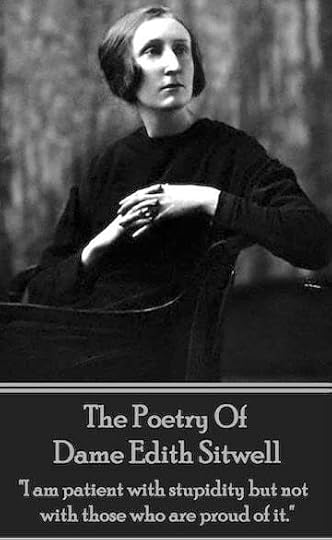

“Fifteen Bucolic Poems” by Edith Sitwell (1920

Dame Edith Sitwell (1887 – 1964), the British poet, literary critic, and famous eccentric, began publishing her poetry in 1913. With a modernist edge, some of it inscrutably abstract, some even set to music and sound.

Because of her dramatic self-presentation and manner of dress, she was sometimes criticized as a dilettante, but overall, her literary legacy remained intact and has grown over the years. Her poetry is praised for its craftsmanship and attention to technique.

Mother and Other Poems (1915) was her first published collection, followed by Clown’s Houses (1915). The following poems comprise the section titled “Fifteen Bucolic Poems” from her third collection, The Wooden Pegasus (1920). This book and its poems are in the public domain.

. . . . . . . . . . .

I

WHAT THE GOOSEGIRL SAID ABOUT THE DEAN

TURN again, turn again,

Goose Clothilda, Goosie Jane!

The wooden waves of people creak

From houses built with coloured straws

Of heat; Dean Pappus’ long nose snores—

Harsh as a hautbois, marshy-weak.

The wooden waves of people creak

Through the fields all water-sleek;

And in among the straws of light

Those bumpkin hautbois-sounds take flight,

Whence he lies snoring like the moon,

Clownish-white all afternoon,

Beneath the trees’ arsenical

Harsh wood-wind tunes. Heretical—

(Blown like the wind’s mane

Creaking woodenly again)

His wandering thoughts escape like geese,

Till he, their gooseherd, sets up chase,

And clouds of wool join the bright race

For scattered old simplicities.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Edith Sitwell

. . . . . . . . . .

II

NOAH

NOAH, through green waters slipping sliding like a long sleek eel,

Slithered up Mount Ararat and climbed into the Ark,—

Slipping with his long dank hair; and sliding slyly in his barque,

Pushed it slowly in a wholly glassy creek until we feel

Pink crags tremble under us and wondrous clear waters run

Over Shem and Ham and Japhet, moving with their long sleek daughters,

Swift as fishes rainbow-coloured darting under morning waters….

Burning seraph beasts sing clearly to the young flamingo Sun.

Note.—Thanks due to Helen Rootham for her earnest collaboration in this poem.

. . . . . . . . . . .

III

THE GIRL WITH THE LINT-WHITE LOCKS

THE bright-striped wooden fields are edged

With noisy cock’s crow trees, scarce fledged—

The trees that spin like tops, all weathers,

Like strange birds ruffling glassy feathers.

My hair is white as flocks of geese,

And water hisses out of this;

And when the late sun burns my cheek

Till it is pink as apples sleek,

I wander in the fields and know

Why kings do squander pennies so—

Lest they at last should weight their eyes!

But beggars’ ragged minds, more wise,

Know without flesh we cannot see—

And so they hoard stupidity

(The dull ancestral memory

That is the only property).

They laugh to see the spring fields edged

With noisy cock’s crow trees scarce fledged,

And flowers that grunt to feel their eyes

Made clear with sight’s finalities.

. . . . . . . . . . .

IV

THE LADY WITH THE SEWING MACHINE

ACROSS the fields as green as spinach,

Cropped as close as Time to Greenwich,

Stands a high house; if at all,

Spring comes like a Paisley shawl—

Patternings meticulous

And youthfully ridiculous.

In each room the yellow sun

Shakes like a canary, run

On run, roulade, and watery trill—

Yellow, meaningless, and shrill.

Face as white as any clock’s,

Cased in parsley-dark curled locks,

All day long you sit and sew,

Stitch life down for fear it grow,

Stitch life down for fear we guess

At the hidden ugliness.

Dusty voice that throbs with heat,

Hoping with its steel-thin beat

To put stitches in my mind,

Make it tidy, make it kind;

You shall not! I’ll keep it free

Though you turn earth sky and sea

To a patchwork quilt to keep

Your mind snug and warm in sleep.

. . . . . . . . . . .

V

BY CANDLELIGHT

HOUSES red as flower of bean,

Flickering leaves and shadows lean!

Pantalone, like a parrot,

Sat and grumbled in the garret,

Sat and growled and grumbled till

Moon upon the window-sill,

Like a red geranium,

Scented his bald cranium.

Said Brighella, meaning well—

“Pack your box and—go to Hell!

Heat will cure your rheumatism.”

Silence crowned this optimism.

Not a sound and not a wail—

But the fire (lush leafy vale)

Watched the angry feathers fly.

Pantalone ’gan to cry

Could not, would not, pack his box.

Shadows (curtseying hens and cocks)

Pecking in the attic gloom,

Tried to smother his tail-plume….

Till a cock’s comb candle-flame,

Crowing loudly, died: Dawn came.

. . . . . . . . . . .

VI

SERENADE

THE tremulous gold of stars within your hair

Are yellow bees flown from the hive of night,

Finding the blossom of your eyes more fair

Than all the pale flowers folded from the light.

Then, Sweet, awake, and ope your dreaming eyes

Ere those bright bees have flown and darkness dies.

. . . . . . . . . . .

VII

CLOWNS’ HOUSES

BENEATH the flat and paper sky

The sun, a demon’s eye,

Glowed through the air, that mask of glass;

All wand’ring sounds that pass

Seemed out of tune, as if the light

Were fiddle-strings pulled tight.

The market square with spire and bell

Clanged out the hour in Hell.

The busy chatter of the heat

Shrilled like a parokeet;

And shuddering at the noonday light

The dust lay dead and white

As powder on a mummy’s face,

Or fawned with simian grace

Round booths with many a hard bright toy

And wooden brittle joy:

The cap and bells of Time the Clown

That, jangling, whistled down

Young cherubs hidden in the guise

Of every bird that flies;

And star-bright masks for youth to wear,

Lest any dream that fare

—Bright pilgrim—past our ken, should see

Hints of Reality.

Upon the sharp-set grass, shrill-green,

Tall trees like rattles lean,

And jangle sharp and dizzily;

But when night falls they sigh

Till Pierrot moon steals slyly in,

His face more white than sin,

Black-masked, and with cool touch lays bare

Each cherry, plum, and pear.

Then underneath the veilèd eyes

Of houses, darkness lies,—

Tall houses; like a hopeless prayer

They cleave the sly dumb air.

Blind are those houses, paper-thin;

Old shadows hid therein,

With sly and crazy movements creep

Like marionettes, and weep.

Tall windows show Infinity;

And, hard reality,

The candles weep and pry and dance

Like lives mocked at by Chance.

The rooms are vast as Sleep within:

When once I ventured in,

Chill Silence, like a surging sea,

Slowly enveloped me.

. . . . . . . . . . .

VIII

THE SATYR IN THE PERIWIG

THE Satyr Scarabombadon

Pulled periwig and breeches on:

“Grown old and stiff, this modern dress

Adds monstrously to my distress;

The gout within a hoofen heel

Is very hard to bear; I feel

When crushed into a buckled shoe

The twinge will be redoubled, too.

And when I walk in gardens green

And, weeping, think on what has been,

Then wipe one eye,—the other sees

The plums and cherries on the trees.

Small bird-quick women pass me by

With sleeves that flutter airily,

And baskets blazing like a fire

With laughing fruits of my desire;

Plums sunburnt as the King of Spain,

Gold-cheeked as any Nubian,

With strawberries all goldy-freckled,

Pears fat as thrushes and as speckled …

Pursue them?… Yes, and squeeze a tear:

‘Please spare poor Satyr one, my dear.’

‘Be off, sir; go and steal your own!’

—Alas, poor Scarabombadon,

They’d rend his ruffles, stretch a twig,

Tear off a satyr’s periwig!”

. . . . . . . . . . .

IX

THE MUSLIN GOWN

WITH spectacles that flash,

Striped foolscap hung with gold

And silver bells that clash,

(Bright rhetoric and cold),

In owl-dark garments goes the Rain,

Dull pedagogue, again.

And in my orchard wood

Small song-birds flock and fly,

Like cherubs brown and good,

When through the trees go I

Knee-deep within the dark-leaved sorrel.

Cherries red as bells of coral

Ring to see me come—

I, with my fruit-dark hair

As dark as any plum,

My summer gown as white as air

And frilled as any quick bird’s there.

But oh, what shall I do?

Old Owl-wing’s back from town—

He’s skipping through dark trees: I know

He hates my summer gown!

. . . . . . . . . . .

X

MISS NETTYBUN AND THE SATYR’S CHILD

AS underneath the trees I pass

Through emerald shade on hot soft grass,

Petunia faces, glowing-hued

With heat, cast shadows hard and crude—

Green-velvety as leaves, and small

Fine hairs like grass pierce through them all.

But these are all asleep—asleep,

As through the schoolroom door I creep

In search of you, for you evade

All the advances I have made.

Come, Horace, you must take my hand.

This sulking state I will not stand!

But you shall feed on strawberry jam

At tea-time, if you cease to slam

The doors that open from our sense—

Through which I slipped to drag you hence!

. . . . . . . . . . .

XI

QUEEN VENUS AND THE CHOIR-BOY

(To Naomi Royde Smith)

THE apples grow like silver trumps

That red-cheeked fair-haired angels blow—

So clear their juice; on trees in clumps,

Feathered as any bird, they grow.

A lady stood amid those crops—

Her voice was like a blue or pink

Glass window full of lollipops;

Her words were very strange, I think:

“Prince Paris, too, a fair-haired boy

Plucked me an apple from dark trees;

Since when their smoothness makes my joy;

If you will pluck me one of these

I’ll kiss you like a golden wind

As clear as any apples be.”

And now she haunts my singing mind—

And oh, she will not set me free.

. . . . . . . . . . .

XII

THE APE SEES THE FAT WOMAN

AMONG the dark and brilliant leaves,

Where flowers seem tinsel firework-sheaves,

Blond barley-sugar children stare

Through shining apple-trees, and there

A lady like a golden wind

Whose hair like apples tumbles kind,

And whose bright name, so I believe,

Is sometimes Venus, sometimes Eve,

Stands, her face furrowed like my own

With thoughts wherefrom strange seeds are sown,

Whence, long since, stars for bright flowers grew

Like periwinkles pink and blue,

(Queer impulses of bestial kind,

Flesh indivisible from mind.)

I, painted like the wooden sun,

Must hand-in-hand with angels run—

The tinsel angels of the booth

That lead poor yokels to the truth

Through raucous jokes, till we can see

That narrow long Eternity

Is but the whip’s lash o’er our eyes—

Spurring to new vitalities.

. . . . . . . . . . .

XIII

THE APE WATCHES “AUNT SALLY”

THE apples are an angel’s meat,

The shining dark leaves make clear-sweet

The juice; green wooden fruits alway

Drop on these flowers as white as day—

Clear angel-face on hairy stalk;

(Soul grown from flesh, an ape’s young talk.)

And in this green and lovely ground

The Fair, world-like, turns round and round,

And bumpkins throw their pence to shed

Aunt Sally’s crude-striped wooden head.

I do not care if men should throw

Round sun and moon to make me go,

(As bright as gold and silver pence) …

They cannot drive their own blood hence!

. . . . . . . . . . .

XIV

SPRINGING JACK

GREEN wooden leaves clap light away,

Severely practical, as they

Shelter the children, candy-pale.

The chestnut-candles flicker, fail….

The showman’s face is cubed clear as

The shapes reflected in a glass

Of water—(glog, glut, a ghost’s speech

Fumbling for space from each to each).

The fusty showman fumbles, must

Fit in a particle of dust

The universe, for fear it gain

Its freedom from my box of brain.

Yet dust bears seeds that grow to grace

Behind my crude-striped wooden face

As I, a puppet tinsel-pink,

Leap on my springs, learn how to think,

Then like the trembling golden stalk

Of some long-petalled star, I walk

Through the dark heavens until dew

Falls on my eyes and sense thrills through.

. . . . . . . . . . .

XV

“TOURNEZ, TOURNEZ, BONS CHEVAUX DE BOIS”

TURN, turn again,

Ape’s blood in each vein.

The people that pass

Seem castles of glass,

The old and the good,

Giraffes of blue wood;

The soldier, the nurse,

Wooden face and a curse,

Are shadowed with plumage

Like birds by the gloomage.

Blond hair like a clown’s,

The music floats, drowns

The creaking of ropes

The breaking of hopes.

The wheezing, the old,

Like harmoniums scold:

Go to Babylon, Rome,

The brain-cells called home,

The grave, New Jerusalem,

Wrinkled Methusalem:

From our floating hair

Derived the first fair

And queer inspiration

Of music (the nation

Of bright-plumed trees

And harpy-shrill breeze).

. . .

Turn, turn again,

Ape’s blood in each vein.

The post “Fifteen Bucolic Poems” by Edith Sitwell (1920 appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Mae West, the Surprisingly Literary Star of Stage & Screen

The notorious stage and screen actress and playwright Mae West of “come up and see me some time” fame, was surprisingly literary minded. West was famous as an actress, but it’s far less known that she wrote all her own stage and screen roles, creating the wickedly witty vamp character she became identified with.

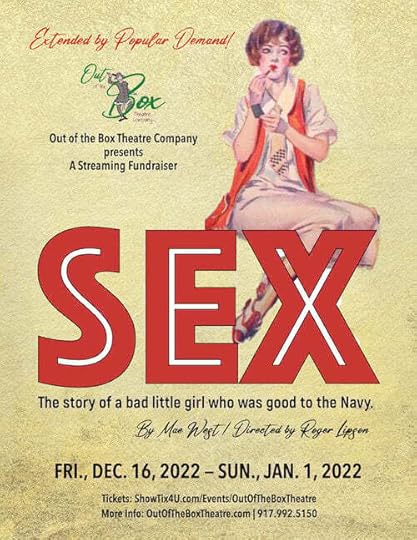

Despite her bad girl reputation, despite having been sentenced to ten days in prison for obscenity in her 1926 play Sex, and despite the equally provocative title of her 1927 play The Drag: A Homosexual Play in Three Acts, Mae West wasn’t as much a modern woman as she seemed. Of her 1928 play Diamond Lil West said:

“People have said that I must be bad myself because I played bad parts so well. They fail to credit me with intelligence and love for my art … Particularly now, with such things as ‘companionate marriage’ ideas floating around, is Diamond Lil timely. I don’t believe in it. I think it is nothing more than contracted prostitution. Marriage, love, and home should be kept sacred … I believe in the single standard for men and women.”

A self-created persona

In an interview in the July 4, 1928 issue of Variety, West emphasized her unique ability to maintain multiple current love affairs, if only in a fictional setting. People tend to forget that practically all the quotes for which she became (in) are all from fictional works that she wrote for her self-created persona to play.

“Diamond Lil has all my stuff in it … I only go into a play where I can be myself and strut my stuff. I know how I want to walk and talk, show off my figure and looks. I can bring one man after another into a play to revolve around me and no one else can. I have five men in love with me in ‘Diamond Lil’ and most authors can’t keep up one love interest,” said the star of the season’s $17,000 weekly freak riot at the Royale, New York.

. . . . . . . . . .

Mae in 1936

. . . . . . . . . .

An early example of her many wisecracks seeming to contradict the quote above comes from the play Sex, where the prostitute Margy is talking about a friend. “She had a guy she thought she was in love with and thought she needed and then she got wise. Now she’s married to an old guy, and she’s got a mansion up near Boston and a limousine and diamonds and everything she wants.”

West was famous for her limousine; another quote is, “If you’re trig and trim and straight and wiry you’ll travel in a slam-bang sports roadster, but if you’re curved and soft and elegant and grand, you’ll travel in a limousine.”

West’s “blonde bombshell” persona was just that: a front for a first-class stage and screen playwright, seriously underestimated as a writer, then and now.

. . . . . . . . . .

A revival of Mae West’s play, Sex, originally staged in 1926

. . . . . . . . . .

She had two plays in production in New York in 1928: Diamond Lil and Pleasure Man, which was prosecuted for a performance at the Biltmore Theater on October 1, 1928, for “unlawfully advertising, giving, presenting and participating in an obscene, indecent, immoral and impure drama, play, exhibition, show and entertainment.”

The prosecution claimed that the play dealt with “sex, degeneracy, and sex perversion” arguing that West and her collaborators “did unlawfully, wickedly and scandalously, for lucre and gain, produce, present and exhibit and display the said exhibition show and entertainment to the site and view of divers and many people, all to the great offense of public decency.”

The 1928 prosecution was especially incensed by the presence of openly gay actors and “the speeches, manners and obscene jokes of a large number of male degenerates.”

West’s empathy with and encouragement of gay actors made her an early icon of the gay scene. Much later West said, “They were all crazy about me and my costumes. They were the first ones to imitate me in my presence.”

West even brought the gay actors from The Drag home to meet her mother. “They’d do her hair and nails and she’d have a great time.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Mae in 1940

. . . . . . . . . .

At the time of the apotheosis of the flat-chested, bobbed-haired, flat-heeled flapper, West was the anti-flapper personified, famous as much for her bust and figure-accentuating dresses as for her wisecracks – “I look pretty buxom and blonde, don’t I? Well, believe me, I’m the kind gentlemen prefer.”

West is referring to Gentlemen Prefer Blondes by Anita Loos, which had been published in 1925 to great acclaim. But despite her love for her gay friends, West blamed gay designers for the flat-chested flapper look she so disapproved of. “God gave women their curves – effeminate dressmakers took them away by designing garments which could be worn only by women shaped like scarecrows.”

It’s important to remember just how outrageous the association with gay men, who could be jailed for homosexual activities, was considered in 1928, the year Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness was banned in England.

Mae West was presumably not surprised and probably not upset by the publicity her plays gained from being prosecuted – she was clearly courting prosecution and controversy with her outrageous titles.

Being “Banned in Boston” could be lucrative; being banned in New York was probably even better in terms of revenue for a book, film or play. In naming her works so provocatively, West was only taking to the limit a piece of advice on finding a title for a film given by silent movie actress Agnes Smith in the April 1928 issue of the movie magazine Photoplay.