Nava Atlas's Blog, page 4

March 18, 2025

Bearing Witness: the Life of War Correspondent Marie Colvin

Marie Colvin (January 12, 1956 – February 22, 2012) was an American journalist known for her intimate, storytelling reporting style covering conflicts worldwide.

She was best known for her coverage of the Middle East (as well as for her trademark black eyepatch, worn after losing her left eye in Sri Lanka). She died while covering the conflict in Syria in 2012, and the Syrian government has since been held responsible for her death.

Early life and education

Marie Catherine Colvin was born in Astoria, Queens, the eldest of five children. She was raised in the affluent Oyster Bay area, Her parents, Bill and Rosemarie, were both high school teachers. Bill was passionate about literature and Democratic politics and passed both passions on to Marie.

Marie studied anthropology at Yale, and during her four years there she “changed from a regular science major to a science major who only takes English courses (there was no time to change majors).”

She took a class with writer and journalist John Hersey, one of the first practitioners of “New Journalism” — in which storytelling techniques are applied to reporting. She was inspired to begin writing for the Yale Daily News and realized this was her calling.

Beginning a career of global reporting

After graduating in 1978, Marie began working as an editor for the newsletter for Teamsters Local 237 in New York City, then moved to a staff reporter position for United Press International in Trenton, New Jersey. In 1984 UPI had named her Paris Bureau Chief. She was responsible for the international news desk, which gave her the opportunity to cover the Middle East, a region that fascinated her.

Marie was determined to cover the possible outbreak of war in Libya in 1986. New York Times reporter Judith Miller told her to “Just go … Qaddafi is crazy, and he will like you.” She went, and indeed, he liked her; she was summoned to his private chambers.

“It was midnight,” she wrote, “when Col. Muammar Gadhafi, the man the world loves to hate, walked into the small underground room in a red silk shirt, baggy white silk pants, and a gold cape tied at his neck.” She recalled that he had introduced himself, “I am Qaddafi,” and she had responded, “No kidding,” before spending the rest of the night fending off his advances.

It was the first of dozens of interviews she conducted throughout her career with heads of state, world leaders and rebel leaders. These included Yasser Arafat, on whom she wrote and produced a BBC documentary based on over twenty personal interviews. She also accompanied him to the White House when peace talks were being conducted with Yitzhak Rabin. During the 1993 Oslo peace accords she reportedly told him, “Just put the pencil down and sign it already.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

In extremis: reporting for the Sunday TimesMarie moved to The Sunday Times in London in 1986 and reported on conflicts all over the world, including East Timor, the Balkans, Sierra Leone, Somalia, and Chechnya. She continued to report on the Middle East and covered the Iran–Iraq war in the 1980s, both Gulf Wars, and the Arab Spring of 2011.

She became recognized for her intimate writing style, avoiding the dominant macho language and image of war reporting. She focused instead on the horrific human cost of every conflict. “My job,” she said, “is to bear witness. I have never been interested in knowing what make of plane just bombed a village.” She won several awards, including the Courage in Journalism Award, the British Press Award, and the Foreign Press International’s Journalist of the Year Award.

Publicly, she wasn’t a fan of feminism, quoting her heroine Martha Gellhorn: “Feminists nark me.” In private, however, she was aware that more was demanded of her than of her male colleagues. On the subject of female journalists, she wrote, “Maybe we feel the need to test ourselves more, to see how much we can take and survive.”

While on assignment, her determination to “go in bare and eat what they eat, drink what they drink, sleep where they sleep” often led her to take extreme risks. She went where other journalists would not, and stayed when others left, driven by the knowledge that “what I write about is humanity in extremis, pushed to the unendurable, and that it is important to tell people what really happens in wars…”

This drive was demonstrated in 1999 in East Timor when Marie and two female Dutch journalists chose to stay in a besieged UN compound with hundreds of refugees who were fleeing Indonesian-backed militia forces. UN staff and other journalists (mostly male) were evacuated, leading to Marie’s wry comment that, “They don’t make men like they used to.”

Marie’s determination to stay saved the lives of those refugees when the UN, embarrassed by her powerful reports, returned to the compound to evacuate them. A front-page headline read, “Her courage saved 1,500.”

Photographer Paul Conroy (one of the few photographers she was happy to work with and who was with her in Syria when she died) said of her bravery,

“People called her fearless, but they are absolutely wrong. She was terrified. Her bravery came from going back in even though she was terrified. That’s completely different from being fearless. It was just that curiosity overtook any sense of staying alive.”

Paying the price: PTSD

Marie did not emerge unscathed from so many war zones. In 2001, while covering an upsurge of violence in the Sri Lankan civil war, she lost her left eye in a rocket-propelled grenade attack. She had already seen more combat than most soldiers; the trauma of the injury triggered the full-blown PTSD that she struggled with for the rest of her life.

At her worst times – often back home in London, where there was nothing to distract her from paranoia, panic attacks, and nightmares – she would disappear for days.

After Marie’s death, friends and colleagues recalled her long nights of partying and drinking, but the reality was a serious alcohol problem that she never quite mastered. Pressured by friends and family, she eventually sought help for PTSD, though she said, “I have no intention of not drinking, [but] I never drink when I am covering a war.”

In extremis II: personal life

Marie’s personal life was tumultuous. Not long after joining the Sunday Times she met her first husband, Patrick Bishop. A diplomatic correspondent, he was in Iraq at the same time as Marie to cover the Iran–Iraq war. He recalled wanting to impress her with his knowledge of artillery and the difference between incoming and outgoing fire.

“I explained that the bang we had just heard was outgoing and therefore nothing to worry about. Then there was another explosion. ‘And that one,’ I said, ‘is incoming!’ and threw myself headlong onto the ground. As the shell exploded some distance away, I looked up to see the woman I had been trying to show off to, gazing down at me with pity and amusement.”

They married in August 1989 but Bishop was unfaithful, and the marriage quickly dissolved. After their divorce, Marie married Bolivian journalist Juan Carlos Gumucio in 1996. This time she suffered two miscarriages, and Gumucio proved to be violent and an alcoholic. They divorced, and he took his own life in 2002.

In 1999, Marie reunited with Bishop while covering the conflict in Kosovo, but the relationship didn’t last any longer the second time around. In 2003, she met Richard Flaye, a divorced company director, and was soon introducing him as “the love of my life.” They shared a passion for ocean sailing, and Flaye seemed to give Marie the kind of stability she’d never experienced. Their relationship lasted on and off until Marie’s death in 2012.

The last assignment: Syria, 2012

With her characteristic drive to report on the brutality of war, Marie was determined to cover the hostilities that began in Syria in 2011. Along with photographer Paul Conroy, she crossed into the city of Homs in February 2012, ignoring the Syrian government’s attempts to prevent journalists from covering the conflict. Homs was under direct attack from the Syrian army and foreign reporters were banned.

Along with other foreign journalists who had also made it in, Marie filed her reports from a makeshift media center surrounded by bombed-out buildings. Homs, she wrote, was: “

… the symbol of the revolt, a ghost town, echoing with the sound of shelling and the crack of sniper fire, the odd car careening down the street at speed. Hope to get to a conference hall basement where 300 women and children are living in the cold and dark. Candles, one baby born this week without medical care, little food.”

Marie and Paul left Homs after a few days when the situation rapidly deteriorated, but Marie was determined to return. This time, there was no space for them to carry video equipment, flak jackets, or helmets, and the Syrian army was under orders to kill any journalists found near the besieged area. They had to crawl for hours through a frigid tunnel from outside of the city. Even in such dire circumstances, though, Marie did not lose her sense of humor: she emailed Flaye that night, saying,

“You would have laughed. I had to climb over two stone walls tonight, and had trouble with the second (six feet) so a rebel made a cat’s cradle of his two hands and said, ‘Step here and I will give you a lift up.’ Except he thought I was much heavier than I am, so when he ‘lifted’ my foot, he launched me right over the wall and I landed on my head in the mud!”

Back at the media center, there were few journalists left. In an interview with CNN broadcast the night before she died, Marie said, “It’s a complete and utter lie they’re only going after terrorists. The Syrian Army is simply shelling a city of cold, starving civilians.”

Marie was killed on February 22, when direct rocket fire hit the media center. French photographer Rémi Ochlik also died in the attack, while Conroy – along with Syrian translator Wael al-Omar and French journalist Edith Bouvier – was severely injured.

The aftermath of Marie Colvin’s death

Marie’s death triggered an outpouring of tributes from friends and colleagues around the world. Questions were raised as to why she went back into Homs when it was so clearly too dangerous. There was a huge backlash against the Sunday Times for “allowing” her to continue in Syria.

According to Vanity Fair journalist Marie Brenner, there was “rage” among foreign staff members at the paper at “what they considered the danger they now faced in the paper’s frenzy for press awards.”

Concerns were also raised about Marie’s mental state and the level of support she had received from her superiors. However, as Marie’s executor, Jane Wellesley, pointed out, “If the Sunday Times had not allowed Marie to continue the work she loved, it would have destroyed her.”

In 2016, a civil suit was filed against the Syrian government by Marie’s family. Three years later, a US court found that the government, led by Bashar al-Assad, was responsible for Marie’s death: Judge Amy Berman Jackson ruled that it had been an “extrajudicial killing” and ordered Damascus to pay over $300 million in damages for the “unconscionable crime.”

Later, the Marie Colvin Memorial Foundation was established at Stony Brook University to honor Marie’s legacy of supporting victims of conflict and the journalists who report on it. The foundation focuses on education, aid, and raising global awareness of conflict.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

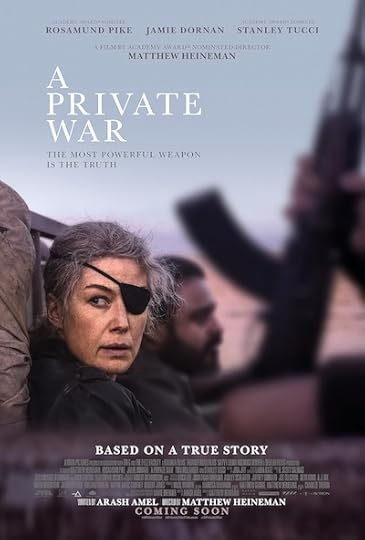

A Private War and Marie Colvin’s LegacyIn 2018, two films and a biography were released about Marie’s life. A Private War is perhaps the best-known. Starring Rosamund Pike as Marie and with Paul Conroy as a consultant, it received positive reviews from critics as well as Marie’s family and friends.

The level of realistic detail in the film was remarkable. Director Matthew Heineman was also a documentary film maker, and ensured that all the extras cast had actually lived through the events being recreated: they were Syrians who had been shelled in a basement in Homs, they were Libyans who had been shaken by the traumas of war.

A documentary film called Under the Wire was also produced, based on Paul Conroy’s memoir about his time with Marie, and Syria in particular.

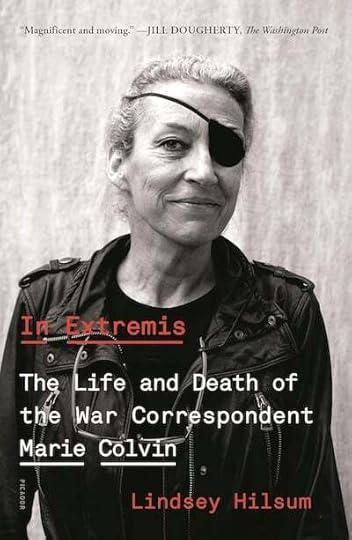

A biography titled In Extremis: The Life of War Correspondent Marie Colvin was written by her longtime friend and colleague Lindsay Hilsum, International Editor for Channel 4 News in the UK. Based on hundreds of interviews with Marie’s family, friends, and other colleagues, as well as Marie’s extensive private journals going back to her childhood, it was a remarkably rounded biography. It won the 2019 James Tait Black Award as well as being shortlisted for the Costa Biography Award.

Hilsum later said, “Part of me thinks Marie is looking down saying, ‘Hey, what’s all the fuss, this is what we do’. But I also think she would be glad that people were talking about Homs again, and hope that maybe some of the attention would be focused on Yemen and other under-reported conflicts and the people suffering in them.”

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find more of her writings here and on Literary Ladies Guide.

. . . . . . . . .

Further reading

In Extremis: The Life of War Correspondent Marie Colvin by Lindsay Hilsum, 2018A Private War: Marie Colvin and Other Tales of Heroes, Scoundrels and Renegades by Marie Brenner, 2019On the Front Line: The Collected Journalism of Marie Colvin by Marie Colvin, 2012The post Bearing Witness: the Life of War Correspondent Marie Colvin appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 14, 2025

Nikki Giovanni: An Appreciation of the Esteemed Poet

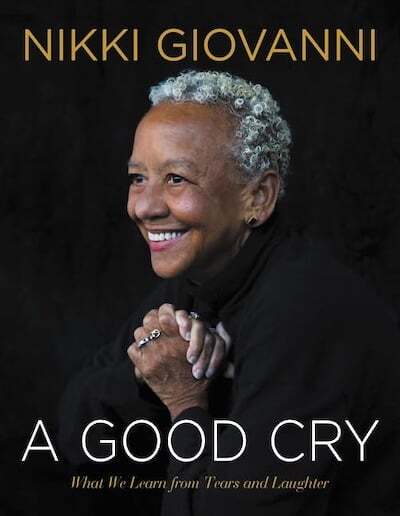

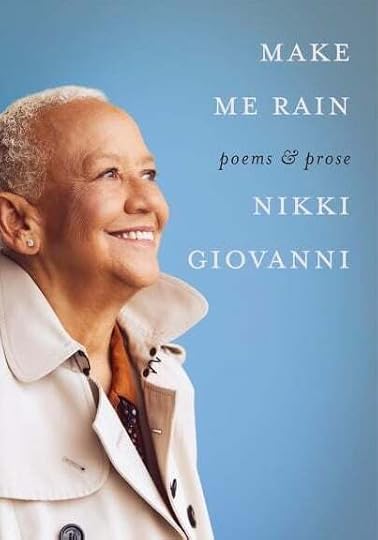

Some years before her death, renowned poet, professor, and activist Nikki Giovanni wrote, “I hope I die warmed by the life I tried to live.”

Giovanni’s hope and vision have been realized. When she passed away on December 9, 2024, she was surrounded by the boundless love of her wife, Virginia Fowler, her son Thomas, and her granddaughter Kai.

Nikki Giovanni was eighty-one years old when she died of complications from cancer, her third diagnosis of the disease. Despite this tremendous physical challenge, Ms. Giovanni continued to write, speak, teach, and publish throughout the last decade of her life.

For nearly sixty years, Giovanni was the quintessential people’s poet. She used deceptively simple language to explore the complexities at the intersection of race, politics, gender, love, loneliness, and creativity.

Giovanni’s friend and fellow poet and author Renee Watson described her as “one of the cultural icons and of the Black Arts and Civil Rights movements. She became friends with Rosa Parks, Aretha Franklin, James Baldwin, Nina Simone, and Muhammad Ali, and inspired generations of students, artists, activists, musicians, scholars and human beings, young and old.”

A turbulent early lifeBorn Yolanda Cornelia Giovanni Jr., her parents were Yolande (Watson) Giovanni and Jones Giovanni, on June 7, 1943. Her older sister, Gary Ann, nicknamed her Nikki. Shortly after she was born, the family moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where her parents worked as grade school teachers.

The Giovanni home was turbulent. Her father abused her mother physically and psychologically. Nikki grew to despise her father’s violence and her mother’s acceptance of the situation.

When she was fifteen, Giovanni decided to save herself and moved into her grandparents’ home in Knoxville, Tennessee. She attended Austin High School, where her grandfather taught Latin, and graduated early.

University studiesHer next stop was Fisk University (an HBCU) in Nashville, Tennessee. Giovanni later commented that Fisk, with its sorority sisters dominating the campus in the early 1960s, was “an odd fit.” The Women’s Dean was especially punitive towards her. When she left campus overnight for Thanksgiving break without permission, she was expelled from the university.

A year later, after Giovanni had returned to Knoxville and worked in a local Walgreens. The new Dean of Women from Fisk University, Blanche McConnell Cowan, went to Knoxville and urged her to return to her studies. Giovanni agreed. She helped to rebuild Fisk University’s chapter of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and began to study with John Oliver Killens, a founder of the Harlem Writers World. She graduated with honors in 1967.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Nikki Giovanni

. . . . . . . . . . .

Giovanni attended the University of Pennsylvania’s School for Social Work for a brief time, but realized that her calling to write was all-consuming. Shortly after she graduated from Fisk, her grandmother, Louvenia Watson, passed away and Giovanni began to write poetry to cope with her grief.

For the next several years, Giovanni wrote and was a frequent guest on Soul!, the PBS Black culture program. She had a son in 1969 and ignored comments regarding her unmarried status. She explained her decision to Ebony magazine with great emphasis:

“I had a baby at 25 because I wanted to have a baby and I could afford to have a baby. I didn’t get married I didn’t want to get married and I could afford not to get married.”

Giovanni held teaching positions at Rutgers University and Queens College until 1987, when Virginia Fowler recruited her to be a visiting professor at Virginia Tech University. Giovanni earned tenure, and she and Ms. Fowler became a couple.

Poetry as truth-tellingGiovanni’s poetry was naturally averse to pretension and artifice. She perceived poetry as a vehicle for truth-telling, dispelling the myths perpetuating an inequitable, racist society. One of her early poems, “Ego-Tripping,” which has been performed for generations by young African American women, exudes pride and power in recognizing themselves in their ancestors:

Ego Tripping (there may be a reason why)

I was born in the congo

I walked in the fertile crescent and built

The sphinx

I designed a pyramid is tough that a star

That glows every one hundred years falls

Into the center giving divine perfect light

I am bad.

Read the full poem here.

In the 1970s, Giovanni wrote poetry that explored nature, intimacy, beauty, and the comforts of home:

My House (an excerpt; this is the third verse)

I mean it’s my house

And I want to fry pork chops

And bake sweet potatoes

And call them yams

Cause I run the kitchen

And I can stand the heat

Read the full poem here.

Giovanni delighted her readers with unexpected bursts of joy, such as the self-deprecating worries of one lover — feeling undeserving of the love given by their new lover:

I Take Master Card

I’ve heard all the stories

‘bout how you don’t deserve me

‘cause I’m so strong and beautiful

And wonderful and you could

never live up to what you know I should have

I want you to know

I take Master Card

Read the full poem here.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Nikki Giovanni in a live talk; honoring TupacAttending a live talk by Nikki Giovanni was one of the most motivational gifts anyone could receive. As Maya Angelou famously remarked, what you remember about people is how they made you feel. Giovanni had a gift for making people feel good.

Giovanni had a gift for connecting with her audience (students were a particular favorite of hers), leaving them with confidence that they too, could write poetry that could change their lives — and perhaps even the world.

I was fortunate to be in an audience of Giovanni’s in November 1996. The San Francisco Book Festival hosted her as one of their major speakers; living in San Francisco then, I was able to attend and experience her magic. She spent some time talking about the murder of rapper Tupac Shakur (which occurred three months before this gathering), angry that many young Black men would not live to reach maturity; still, she expressed mood of moving forward. She had the audience actively engaged and absorbing every word without descending into collective despair.

In honor of Tupac, THUG LIFE, the tattoo that Tupac Shakur had emblazoned on his chest, was adapted to a much smaller size and tattooed on Ms. Giovanni’s wrist. Ms. Giovanni stated that she would “rather be with the thugs than the people talking about them.” In 1997, Giovanni published her book Love Poems, a remembrance of Tupac. That night, the audience heard part of the poem All Eyes on U:

All Eyes on U (for 2Pac Shakur 1971-1996)

if those who lived by lies died by lies there would be nobody on wall street

In executive suites in academic offices instructing the young

don’t tell me he got what he deserved he deserved a chariot and

The accolades of a grateful people

he deserved his life

Read the rest of the poem here.

Nikki Giovanni speaking at Emory University, 2008

Photo by Brett Weinstein, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . .

Nikki Giovanni wrote thirty books in her lifetime: poetry, prose, and children’s books. Although she never sought accolades, she was honored to accept the NAACP Image Award, the Langston Hughes Medal, the Caldecott Medal, and the Children’s Book Award. She held twenty-seven honorary degrees from various colleges and universities, and was given the key to more than two dozen American cities.

Perhaps Giovanni’s most unusual recognition was by scientist Robert James Baker, a devoted fan who named a species of a South American bat after her: the Micronycteris giovanniae.

Giovanni retired from Virginia Tech in 2022 and, despite her health challenges, wrote until the end of her life. The Last Book, her fittingly titled final poetry collection, will be published in late 2025.

Poet Renee Watson, a close friend of Giovanni’s, wrote a praise poem for Giovanni’s eightieth birthday. It encapsulates her place in history and the arts:

Ever year on the seventh of June

Heaven throws a birthday party

for Nikki.

Coretta is there. She’s protective of Aiyana and Hadiya.

She introduces them to Sandra and Breonna, keeps them close.

And surely Harriet and Fannie and Rosa are swapping stories of how

They got over.

And Lucille and Gwendolyn and Margaret recite sonnets, teach them to Betty.

And Toni and Maya are writing jubilees for the angels to sing.

Read more about this poem (along with Watson’s conversation with Nikki Giovanni here)

. . . . . . . . .

Further reading and sources

Poetry Foundation Nikki Giovanni’s personal website Remembering the Fierce and Lyrical Voice of Nikki Giovanni (video) In Memoriam: Nikki Giovanni Nikki Giovanni, Poet Who Wrote of Black JoyContributed by Nancy Snyder, who retired from the City and County of San Francisco and as a union officer for SEIU Local 1021/790. She writes about books and women writers to understand the world and her place in it.

The post Nikki Giovanni: An Appreciation of the Esteemed Poet appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 10, 2025

Mary Wollstonecraft’s Letters from Scandinavia (1796)

The work of feminist writer and philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft’s (1759–1797) has endured, despite attempts of critics of her time to bury her legacy after her death. A year after she died, her husband, William Godwin, published Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman, unwittingly turning the public against the love of his life.

Two generations later, however, women rediscovered Mary Wollstonecraft’s writing — breathing new life into a historical figure who might have been forgotten along with other notable women whose words were lost to the patriarchy.

William Godwin meant no harm when he published his memoir of Mary Wollstonecraft in 1798. Mired in grief, he wanted the world to know Mary the way he did— as a compassionate, brilliant woman.

His mistake was putting her personal life on display by including her private letters to her former lover, Gilbert Imlay, an American businessman, in the appendix of the memoir. Mary had lived with Imlay and had their daughter, Fanny, out of wedlock. The public scorned Mary, judging her to be immoral. The public turned on Godwin as well; his stature in the literary and political establishment plummeted.

What could he have been thinking? If Godwin wanted people to know the real Mary Wollstonecraft, he could have simply directed them to her 1796 travel narrative: Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark is a highly personal account of Mary’s journey to Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. She traveled to these Scandinavian countries in 1795 on Gilbert Imlay’s behalf, hoping to recover a missing shipment of silver.

Mary’s ultimate goal: to win Imlay back from the actress he had taken up with. Bereft over his infidelity, she tried to take her own life by drinking laudanum.

. . . . . . . . .

Solitary Walker: A Novel of Mary Wollstonecraft by N.J. Mastro

is available on Bookshop.org*, Amazon*, and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . .

Mary met Gilbert Imlay in France in 1793, where she had moved to write about the French Revolution. Imlay, an American, was there on “business.” Perhaps seeing an independent, adventuresome spirit akin to her own (they both resisted the idea of marriage), they embarked on an affair.

After a time, Imlay pulled away from Mary. When he moved to London for his shipping enterprise and left her in Paris with their child, Mary plunged into an emotional abyss. A few months later, when France declared war on Great Britain, she was in danger. As a British national, the authorities could arrest her at any moment. Making matters worse, her once revolutionary writing had suddenly marked her as an anti-revolutionary under Maximilien Robespierre’s new regime. To be on the safe side, she and Imlay pretended to be married. Her status as his wife, Imlay assured her, would ward off the authorities.

Mary didn’t foresee the trap she was stepping into — the kind that ensnares women who are blinded by love. When she and Imlay faked their marriage certificate with the help of the American ambassador, Gouverneur Morris, they never spoke of how the lie might end. Imlay’s sudden abandonment of Mary and their daughter forced the question.

Persistent and determined, Mary knew her reputation (and thus her livelihood) would be ruined if it were to come out that she and Imlay weren’t married. Thus, in the spring of 1795, she would have done anything to keep him. That included traveling to Scandinavia to find the shipment of missing silver — which, to Mary’s horror, Imlay had stolen.

It was audacious to travel alone to Scandinavia with only her daughter Fanny and the child’s nursemaid as companions. Scandinavia was a remote, rugged land in the far northern reaches of the hemisphere. Mary hired no guide and carried no pistol for protection. She wrote frequently to Imlay, expressing the intense sadness she felt:

“How am I altered by disappointment! — When going to [Lisbon] ten years ago, the elasticity of my mind was sufficient to ward off weariness — and the imagination could dip her brush in the rainbow of fancy, and sketch futurity in smiling colours. Now I am going towards the North in search of sunbeams! — Will any ever warm this desolated heart? All nature seems to frown — or rather mourn with me. — Every thing is cold — cold as my expectations! … I have lost the little appetite I had; and I lie awake, till thinking almost drives me to the brink of madness — only to the brink for I never forget, even in the feverish slumbers I sometimes fall into, the misery I am labouring to blunt …”

In addition to documenting the journey in letters, Mary kept notes of her travels. Prior to leaving London, she had secured an advance from her publisher, Joseph Johnson, for a travel narrative to be written upon her return.

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Mary Wollstonecraft

. . . . . . . . .

Mary’s mission to recover Imlay’s silver fell short, but not before turning over every possible lead in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark — all to no avail. Upon her return to London, she and Imlay parted for good. Distraught, Mary attempted to drown herself by jumping into the Thames. Watermen rescued her downstream.

As she had always done, Mary turned to her pen as an antidote to despair. During her physical and emotional recovery, she realized that the letters she’d written to Imlay (which he had returned to her) were the perfect the framework for her travel narrative. In a matter of months, she penned Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark, an epistolary travel narrative addressed to an unnamed individual.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, an Enlightenment philosopher Mary favored, may have influenced the structure of her travel narrative. Rousseau’s Reveries of a Solitary Walker (1782), an autobiographical account of his walks in France in the final years of his life, revealed his state of disenchantment. Mary likely felt some affinity with Rousseau as she traveled alone with her daughter in the verdant taiga in the summer of 1795.

Mary had been more discrete than her future husband William Godwin, who put her words before a harsh public after her death. For example, she wrote to Imlay that summer from Gothenburg, Sweden, on July 1:

“I labor in vain to calm my mind — my soul has been overpowered by sorrow and disappointment. Every thing fatigues me — this is a life that cannot last long … we must either resolve to live together, or part for ever, I cannot bear these continual struggles.”

But in her travel narrative, she tempered her expression, pulling a thin veil over her distressed feelings, yet baring her soul as she confessed how sadness enveloped her in this foreign land:

“How frequently has melancholy and even misanthropy taken possession of me, when the world has disgusted me, and friends have proved unkind.”

Mary admitted that she carried deep wounds — a daring move for a writer, especially a woman. In a later passage in Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark, she became more direct:

“You have sometimes wondered, my dear friend, at the extreme affection of my nature. But such is the temperature of my soul. It is not the vivacity of you, the heyday of existence. For years I have endeavoured to calm an impetuous tide, labouring to make my feelings take an orderly course. It was striving against the stream. I must love and admire with warmth, or I sink into sadness. Tokens of love which I have received have wrapped me in Elysium, purifying the heart they enchanted.”

Who is “you?” Mary doesn’t tell the reader, but those in her circle knew she was writing to Imlay, whom they also believed was her husband. Mary didn’t care. Using Imlay as a prop to tell her story, projecting him as cold and unfeeling, she gave herself the last word in their failed love affair.

Scandinavia wasn’t a complete loss for Mary. Her travel narrative conveyed how time spent in nature improved her lagging spirits, and she seemed to have gotten a modicum of relief from her melancholy. Glimmers of the Mary of old began to resurface, and she charmed readers with frankness and sincerity.

So smitten was William Godwin upon reading Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark, he remarked, “If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book.” He and Mary first met at a dinner held by her publisher, Joseph Johnson, where they traded fiery words. Four years later, they reconnected. In Memoirs, Godwin described their renewed acquaintance:

“When we met again, we met with new pleasure, and, I may add, with a more decisive preference for each other … It was friendship melting into love. Previously to our mutual declaration, each felt half-assured, yet each felt a certain trembling anxiety to have assurance complete.”

In Memoirs, Godwin adopted some of Mary’s candor, writing that he’d never loved a woman until he met her. Godwin was a confirmed bachelor who avoided marriage. Mary did as well, so they were, in that sense, a perfect match … that is, until she became pregnant. With Imlay back in France, she had a decision to make. Knowing that she’d be ostracized if it were to come out that she and Imlay had never been wed, she married Godwin. For with him, she’d finally found a union of love based on mutual respect and adoration.

The Godwins delighted in redefining the institution of marriage and did things their way. People who are ahead of their time, Mary asserted, must be willing to face censure; yet surprisingly, they got away with most of their bold actions.

William Godwin woefully miscalculated the public’s reaction when he paid tribute to Mary Wollstonecraft upon her death. His revelations resulted in the very damage to her reputation she had managed to circumvent during her unorthodox life.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: An Appreciation

. . . . . . . . . .

As the 19th century unfolded, suffragists in America and Great Britain resurrected Mary Wollstonecraft’s writings. They turned to A Vindication of the Rights of Woman for inspiration in their quest to secure equal rights. For these reformers, it wasn’t just about the vote; they wanted educational equality, the opportunity to work in any chosen occupation, and the ability to enter the political sphere. In short, they wanted agency and freedom.

“I do not wish them [women] to have power over men;” Mary wrote in her now-famous treatise, “but over themselves.”

Today, historians widely refer to Mary Wollstonecraft as the mother of feminism. William Godwin holds the distinction of being known as the founder of philosophical anarchism, a political philosophy that promotes self-government and progressive rationalism, including benevolence to others. Both are tremendous gifts to humanity.

Another was the child born to William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft. Mary Godwin grew up to be Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein or, The Modern Prometheus, the 1818 novel that launched the genre of science fiction. Mary Shelley never knew her mother, but clearly, Mary Wollstonecraft’s revolutionary spirit resided in her.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by N.J. Mastro, the author of Solitary Walker: A Novel of Mary Wollstonecraft, a biographical novel about Mary Wollstonecraft’s incredible rise as a writer and philosopher and her ill-fated forays into love. Set against the backdrop of 18th-century London, the French Revolution, and the remote shores of Scandinavia, this well-researched novel captures the timeless story of a woman in search of herself.

*These are Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate links. If a product is purchased after linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps us to keep growing.

The post Mary Wollstonecraft’s Letters from Scandinavia (1796) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 6, 2025

The Little-Known Writings of Zelda Fitzgerald

Zelda Fitzgerald was an American author, artist, and socialite. Although she is best remembered as the wife of F. Scott Fitzgerald, she was a talented writer and artist in her own right, which caused the couple a great deal of conflict.

Zelda wrote one novel (Save Me the Waltz) and an unstaged play, Scandalabra. What is less known is that she wrote various articles for periodicals, including College Humor, Harper’s Bazaar, and the New York Tribune. Here, we’ll take a closer look at five of these little-known features.

Zelda Fitzgerald’s life in brief

Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald (1900 – 1948) was born into to an affluent family in Montgomery, Alabama. In 1920, she married F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896–1940), and the couple moved to New York City, where they became known for their hard-drinking and party-centric lifestyle. Zelda became known as a flapper—the word coined for free-spirited young women living on their own terms.

Zelda’s work wasn’t successful in her lifetime. Save Me the Waltz sold poorly, earning only about $120 in royalties, according to the F. Scott Fitzgerald Society. In comparison, F. Scott Fitzgerald earned approximately $17,055 for various writings in the 1920s.

The Collected Writings of Zelda Fitzgerald compiles most of Zelda’s work in one volume. It includes her novel and play. Zelda was also a visual artist, though her few gallery exhibitions weren’t successful. Reproductions of her work can be seen here.

The Fitzgerald’s marriage eventually fell apart, and Zelda was institutionalized for various mental illnesses, including depression and possible schizophrenia. Zelda began work on a second novel, Caesar’s Things, after Scott’s death, but it remained unfinished due to her various challenges. Repeated electroshock treatments, among others, greatly affected her quality of life and memory.

While sedated, Zelda died at Highville Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina in an arson fire. She was inducted into the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame in 1992, and in recent times her work has been reconsidered, especially for her honest, sometimes biting commentary about being a woman in the early decades of the twentieth century.

5 Published Featurs by Zelda Fitzgerald

Zelda sold her first article to Metropolitan Magazine in 1922, commenting on the phenomenon of 1920s flapper culture—essentially, outspoken women who rejected cultural norms and repressive attitudes of the time.

Her writings were sometimes credited alongside her husband, though it’s now believed she did most of the writing. Scott is likely to have taken some passages from her diaries to use in his own work.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

“Eulogy on the Flapper” (Metropolitan Magazine, June 1922)Zelda’s article, “Eulogy on the Flapper” (1922, Metropolitan Magazine), delved into the popular subculture. comments on what it was like to be an influential, outspoken woman of the time.

The piece starts with Zelda’s disillusionment about popular culture and party life, expressing her growing dissatisfaction with life, only two years into her marriage.

“The Flapper is deceased. Her outer accoutrements have been bequeathed to several hundred girls’ schools throughout the country, to several thousand big-town shopgirls, always imitative of the several hundred girls’ schools, and to several million small-town belles always imitative of the big-town shopgirls via the ‘novelty stores’ of their respective small towns.”

The piece continues, describing the idealistic enthusiasm with which young women opposed conservative 1920s culture:

“’Out with inhibitions,’ gleefully shouts the Flapper, and elopes with the Arrow-collar boy that she had been thinking, for a week or two, might make a charming breakfast companion.”

Zelda ends “Eulogy on the Flapper” with irony, implying that flapper culture wasn’t dead but deliberately suppressed — instead of being naïve, as they were commonly perceived, she writes that flappers teach young women to think for themselves:

“And yet the strongest cry against Flapperdom is that it is making the youth of the country cynical. It is making them intelligent and teaching them to capitalize their natural resources and get their money’s worth. They are merely applying business methods to being young.”

“Friend Husband’s Latest” (New York Tribune, April 1922)

Zelda’s influence on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s work is unmistakable. According to multiple sources, Zelda was the inspiration for several characters in his novels and stories—including Rosalind in his debut novel This Side of Paradise.

The feature Friend Husband’s Latest is a review of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Beautiful and Damned, from Zelda’s perspective. She begins with a simple, sarcastic description:

“I note on the table beside my bed this morning a new book with an orange jacket entitled The Beautiful and Damned. It is a strange book, which has for me an uncanny fascination. It has been lying on that table for two years. I have been asked to analyze it carefully in the light of my brilliant critical insight, my tremendous erudition, and my vast impressive partiality. Here I go!”

According to this feature, Scott had appropriated several passages from Zelda’s diaries and inserted them into the book—presumably without her permission.

“Mr. Fitzgerald—I believe that is how he spells his name—seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.”

Some modern scholars believe that Zelda’s co-written pieces were entirely her own, though many were credited to both she and Scott. Similarities in their writing styles have also made some suspect that Scott had plagiarized from her work more than once.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

“Looking Back Eight Years” (College Humor, June 1928)“Looking Back Eight Years” presents a disillusioned take on Zelda’s life over an eight-year period. In Zelda’s words, quoted from the book Zelda Fitzgerald: Her Voice in Paradise below:

“It is not altogether the prosperity of the country and the consequent softness of life which have made them unstable… It is a great emotional disappointment resulting from the fact that life moved in poetic gestures when they were younger and has now settled back into buffoonery…”

At this point, Zelda may have looked back to the optimism of her youth and compared it with her mounting dissatisfaction:

“Sensitive young people are haunted and harassed by a sense of unfulfilled destiny.”

“Who Can Fall in Love After Thirty” (College Humor, October 1928)

“Who Can Fall in Love After Thirty” explored Zelda’s thoughts on love, passion, and how one’s perception might change with age.

“The one passion that does not exist for the men of forty is the bombastic, reckless, uncalculated, uncompromising one mostly responsible for adolescent marriages. Their horizon has broadened, their energies are spread over a wider field, they have learned to discipline and weigh their impulses toward adventure.”

She implies further dissatisfaction with, and seeking different things from, a relationship after age thirty. When she wrote this piece, her relationship with Scott was extremely strained, and compared it with a wine that’s costly and intoxicating.

“It seems to us that at thirty, the haze of youth having lifted a little, emotions are stronger for their clarity, more definite for the fact that by then they have a category, a place where they belong — for the same reasons that wine in a bottle with a year is better than wine on tap; and if it is more costly and intoxicating, well, maybe that’s why people drink less of it!”

She continued writing for College Humor until 1931, when her last piece, “Poor Working Girl,” was published.

“The Changing of Park Avenue” (Harper’s Bazaar, January 1928)

“The Changing of Park Avenue” described one of New York City’s most prestigious locations at the height of the 1920s Jazz Age.

“Beginning in the pool of glass that covers the Grand Central tracks, Park Avenue flows quietly and smoothly up Manhattan. Windows and prim greenery and tall, graceful, white facades rise up from either side of the asphalt stream, while in the center floats, impermanently, a thin series of water-color squares of grass—suggesting the Queen’s Croquet Ground in Alice in Wonderland.”

She praises its beauty but also criticizes its opulence:

“There has never been a faded orchid on Park Avenue. And yet this is a masculine avenue. An avenue that has learned its attraction from men—subdued and subtle and solid and sophisticated in its understanding that avenues and squares should be a fitting and sympathetic background for the promenades of men.”

Zelda’s criticism of Park Avenue can also be viewed as being part of a larger critique aimed at a dissolute society as a whole:

“There is a lightness about these mornings. Nobody has ever asked a geographical question on Park Avenue. It is not ‘the way’ to anywhere. It exists, apparently, solely because millionaires have decided that life on the grand scale in a small space is only possible with as tranquil and orderly a background as this long, blond, immaculate route presents.”

Zelda frequently drew from her own life and experiences, including the 1931 story “Poor Working Girl ” (College Humor) that was inspired by her life with Scott in New York.

Perhaps expressing her own thoughts about criticism, the story ends with the line: ”[…] perhaps Eloise wasn’t destined for Broadway after all.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Alex J. Coyne, a journalist, author, and proofreader. He has written for a variety of publications and websites, with a radar calibrated for gothic, gonzo and the weird. His features, posts, articles and interviews have been published in People Magazine, ATKV Taalgenoot, LitNet, The Citizen, Funds for Writers, and The South African, among other publications.

Further ReadingA complete list of Zelda and Scott’s publications in newspapers and magazines can be found here. Zelda Fitzgerald Papers (Princeton) Britannica: Zelda Fitzgerald Cambridge Dictionary: Flapper Alabama MomentsThe post The Little-Known Writings of Zelda Fitzgerald appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 28, 2025

1920s Novels by Women Writers That Still Resonate Today

It’s incredible (and sad) that we’re still grappling with the same issues presented in these five 1920s novels by women writers. Four of them fell out of print and were rediscovered and reissued decades later; one has never gone out of print. It’s wonderful that all are available in fresh new or recent editions.

In these reissues, fascinating new introductions, forewords, or afterwords re-introduce these writers aren’t known enough and/or shouldn’t have been forgotten in the first place: Ursula Parrott, Radclyffe Hall, Anzia Yezierska, Jessie Redmon Fauset, and Dorothy Canfield Fisher.

As Edna St. Vincent Millay famously wrote, it’s not one damn thing after another, it’s the same damn thing, over and over. One hundred years or so after these books came out, we’re still grappling with their central themes in the culture and in personal lives. And while that’s frustrating, it’s also why these novels are still relevant to contemporary readers.

. . . . . . . . . .

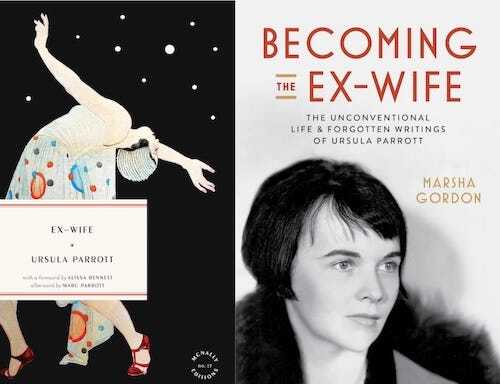

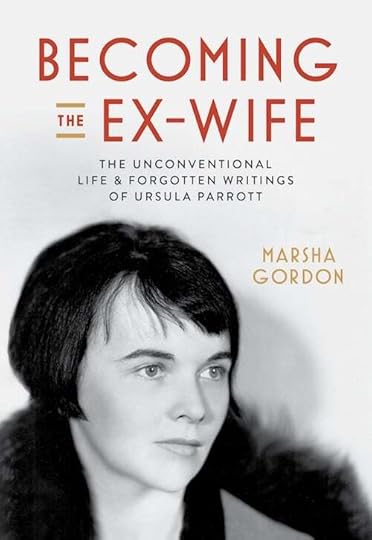

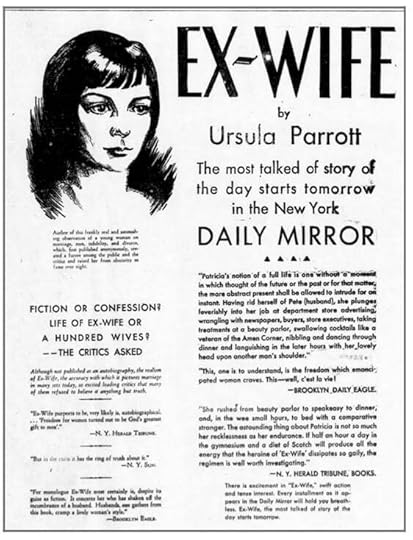

Ex-Wife by Ursula Parrott (1929)

The struggle for women’s bodily autonomy goes on, alas

I first discovered Ursula Parrot and her best-known book, Ex-Wife, in this episode of the Lost Ladies of Lit podcast. Marsha Gordon, the author of Becoming the Ex-Wife: The Unconventional Life & Forgotten Writings of Ursula Parrott . It remained the most successful and controversial of her many published works. From Marsha:

“Once the most renowned ex-wife in America, bestselling author Ursula Parrott (1899– 1957) was routinely described as ‘famous’ in her lifetime when the press covered her new books, Hollywood deals, marriages and divorces, and run-ins with the law … She published twenty books from the late 1920s through the late 1940s, several of them bestsellers, and over one hundred short stories, articles, and novel-length magazine serials.

… After making hundreds of thousands of dollars writing — during the height of the Depression no less — Ursula lost it all, ending up homeless in the 1950s. Like many other influential, bestselling women writers, she was unfairly pigeonholed and dismissed as a romance magazine writer and her death in 1957 transpired with little notice.”

Patricia, the novel’s protagonist, relates her adventures and misadventures in a brisk, wry style. The writing feels so fresh, it could have been written yesterday. Patricia’s story features a disintegrating open marriage, bed-hopping, abortion, rape, and spousal abuse, all awash in plenty of alcohol (though set in the days of prohibition).

A typical review observed: “There is a procession of men friends, numerous affairs — but no real love or joy … This book is assuredly frank. If it hasn’t been ‘banned in Boston,’ it will be.” Though Ex-Wife’s controversies drove it onto the bestseller list, it was never banned — demonstrating the random nature of censorship. Many reviewers cast Ex-Wife as a cautionary tale: “Freedom of women found not so free,” blared one headline.

In Becoming the Ex-Wife, Marsha Gordon pinpoints what is so disturbing about how Ex-Wife was received and reviewed:

“While many contemporary reviewers of the novel criticized its sensationalism, none expressed concerned over the violence Patricia endures. That reviewers compared Ex-Wife to novels ranging from Daniel Defoe’s 1724 Roxana to Anita Loos’s 1925 Gentleman Prefer Blondes suggest a certain blindness to the real atrocity of the novel, which has to do with the way men, repeatedly, forcefully, and viciously take liberties with women’s bodies. Was this violence so ordinary, or seemingly justifiable, that it went unnoticed?”

All twenty of Ursula Parrot’s fell out of print. McNally Editions republished Ex-Wife in 2023; and it has been translated into Italian, Swedish, Spanish, German, and Dutch. Marsha Gordon has lots more to say about this forgotten author and her neglected body of work in 10 Fascinating Facts About Ursula Parrott.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall (1928)

A queer writer’s plea for tolerance is dragged through the courts

Radclyffe Hall (1880 – 1943) was a British author best known for her groundbreaking novel, The Well of Loneliness. It’s often described as the story of young woman’s coming to terms with her lesbian identity, but it’s more than that. It’s about a person born female making sense of her maleness. It was certainly ahead of its time in expressing the concept of gender dysphoria without the vocabulary available today.

Radclyffe Hall wore male clothing, preferred to be called “John,” and wanted to be accepted by society as male. Hall described herself as a “congenital invert,” a term that came from early 20th-century sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing, referring to inborn gender reversal where women could be born with a masculine soul and vice versa — in contemporary terms, transgender.

The book’s main character is Stephen Gordon, whose father fittingly gave her a male name. Hall touchingly, often achingly, weaves the story of Stephen’s life, longings, and relationships with women using the limited descriptive language available at the time. The book caused a furor when it was published in England in 1928. Though it addressed its themes in a subtle and completely non-graphic manner, copies of the book were seized soon after publication.

The campaign against the book was led by the editor of the Sunday Express, who famously wrote, “I would rather give a healthy boy or a healthy girl a phial of prussic acid than this novel.”

Hall’s publisher forced to endure an obscenity trial. The prosecution won, with the British court ruling that the novel was obscene because it defended “unnatural practices between women.” Hall and her publisher were forced to burn the already-printed copies in England, at their own expense. Fortunately, the book was concurrently published in France and other countries, and thanks to a loophole it could be imported into Britain. The controversy made it a bestseller, though officially it remained banned in England until 1959, sixteen years after Hall’s death.

The Well also went to trial in the U.S. in 1928, and it prevailed, though not without a fight (and a sharp attorney). Radclyffe Hall waded into the fray with eyes open. She wrote the novel purposefully as a plea for tolerance of people who didn’t fit into the gender binary. Of the five books presented here, it’s the only one that has never gone out of print. Consider a foundational LGBTQ classic, it’s a great read — or listen. I’m listening to it on Audible, interpreted by a wonderful reader.

. . . . . . . . . .

Bread Givers by Anzia Yezierska (1925)

The travails of a young woman immigrant and the elusive American Dream

Bread Givers is the best-known novel by by Anzia Yezierska (1885 – 1970), whose work reflected the Jewish immigrant experience in early 1900s America. To present this kind of story with a female perspective — and get it published — was a rarity at the time, reflecting the author’s chutzpah and determination.

Anzia arrived with her family to New York City’s Lower East Side around 1893. A product of the immigration wave of the late 1800s, she never quite shed the feeling of being an outsider. Longing to rise above her circumstances, she was somewhat hampered by her brittle personality and a helping of self-loathing.

An autobiographical novel, Bread Givers delves into the well-trodden theme of an immigrant family whose children strain against Old World parents. The father, Reb. Smolinsky, is learned in the holy Torah, but he’s childish, impractical, and inflexible when it comes to his three daughters, who chafe under his domination.

The youngest and feistiest of the sisters is Sara, oddly nicknamed “Blut und Eisen” (Blood and Iron). The fictional stand-in for the real-life Anzia, Sara rebels fiercely, fighting for autonomy and self-determination. The process of breaking away from her father’s rule is painful. Some of her strivings lead to discomfort and embarrassment, but she emerges as a person (mostly) in command of her world.

Bread Givers reads a bit awkwardly at times, sometimes apparent that English wasn’t this writer’s first language. Still, it’s a fast-moving read in which one person’s immigrant experience speaks to the universal promise and perils of the mythical American Dream.

Bread Givers was out of print when it was rediscovered by a doctoral student in the 1960s. It was republished in 1975 and has been reissued in several editions since. Here’s more about Bread Givers and in Anzia’s own words, her struggle to write it.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

There is Confusion by Jessie Redmon Fauset (1924)

Black narratives and histories are once again being challenged

There is Confusion by Jessie Redmon Fauset (1882 – 1961) was the first novel by this multitalented editor, poet, essayist, educator, and novelist associated with the Harlem Renaissance. In addition to her own pursuits, Jessie was known as one of the “literary midwives” of the movement, someone who encouraged and supported other talents in her role as the literary editor of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP.

After being out of print for decades, Modern Library reissued There is Confusion in 2020 (this novel deserves a better cover!). The publisher’s synopsis:

“A rediscovered classic about how racism and sexism tests the spirit, ambition, and character of three children growing up in Hell’s Kitchen and Harlem … Set in early-twentieth-century New York City, There Is Confusion tells the story of three Black children: Joanna Marshall, a talented dancer willing to sacrifice everything for success; Maggie Ellersley, an extraordinarily beautiful girl determined to leave her working-class background behind; and Peter Bye, a clever would-be surgeon who is driven by his love for Joanna … There Is Confusion is an unjustly forgotten classic that celebrates Black ambition, love, and the struggle for equality.”

Reviews in white newspapers made a huge to-do about There is Confusion’s depiction of middle-class Black people doing ordinary things and grappling with universal quandaries and challenges of life. They didn’t object, but found it incredible that the Black characters were portrayed in ways that didn’t involve the usual demeaning stereotypes. They also expressed amazement that a Black woman could write so gracefully, blithely unaware that Jessie was a graduate of Cornell University (class of 1905!) and had a Master’s degree in French from the University of Pennsylvania.

There is Confusion was the first of Jessie Fauset’s four novels, all of which were occasionally criticized by Black critics as having an overly bourgeoise perspective. Yet other Black reviewers were delighted. Critic and anthropologist William Stanley Braithwaite praised Jessie as “the potential Jane Austen of Negro literature.” Here’s more about There is Confusion.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Home-Maker by Dorothy Canfield Fisher (1924)

Women are still doing most of the housework and childcare

The Home-Maker by Dorothy Canfield Fisher imagined a domestic role-reversal, something virtually unheard of in the early 1920s. Fisher (1879–1958) was an American writer, educational reformer, and social activist based in New England.

At the start of The Home-Maker, Evangeline and Lester Knapp are both unhappily going through the motions of their traditional roles. An accident forces them to reverse roles, and from that adversity, the family finds strength and happiness. I couldn’t scout out when The Home-Maker fell out of print, other than that it did. It seems to have been re-issued as an Audible edition only (which is how I consumed it), and not in book form. Here’s a concise description from the audio edition:

“Evangeline Knapp’s neighbors are in awe of her prowess. She re-upholsters furniture and can take scraps of fabric and create a beautiful garment. Her house is always immaculate and her children are beautifully behaved — except for the stubborn youngest, but with Eva’s strength of will, they’re certain she’ll sort him out in time.

The neighbors don’t know that in her frenzied zeal to create the perfect home, her children live in dread of her temper. She loves them, but she can’t stand having to remind them constantly about the same things, simple rules easy enough for anyone to understand. Eva can’t abide childishness.

Her husband Lester is no less miserable in his job as a department store accountant, sacrificing his love of literature and poetry to the daily grind of commerce. Lester can’t seem to get ahead and feels like a failure … When a near-fatal accident forces these two to switch roles, each finds their true calling. Then fate steps in again. As with her children’s classic Understood Betsy, Dorothy Canfield Fisher brilliantly explores the inner lives not only of the parents but the three Knapp children. The Home-Maker proves … that biology should not determine destiny.”

The Home-Maker seems to have been well-received at the time as a mid-list book by a well-known author. Despite its unusual theme, it was surprisingly uncontroversial. I wonder if it would be more so today, with this crazy “trad wife” trend happening. This novel is engaging and enjoyable, and reminds us that even today, women in heteronormative households are still doing the lion’s share of housework and childcare.

The audiobook of The Home-Maker is available on Audible (via Amazon), and can also be read on Project Gutenberg (though the formatting is hard on the eyes).

The post 1920s Novels by Women Writers That Still Resonate Today appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

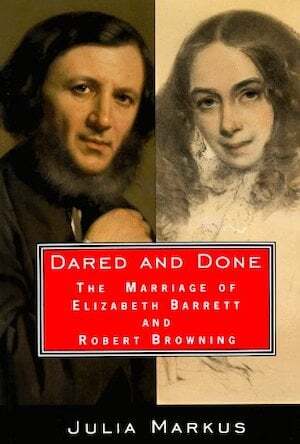

Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Mystery Illness: Theories and Conjectures

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861) was one of the great romantic poets of the Victorian era. “Sonnet 43” breathed her famous words to life: “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.”

Her early texts, flavored with feminism, paved the way for others to follow. Immensely popular in her lifetime, her work was somewhat forgotten until rediscovered with new appreciation starting in the second-wave feminist era of the 1970s. Her life was one of contrasts: she was remarkably prolific, enjoyed a happy marriage with fellow poet Robert Browning, yet her lifelong chronic illness shadowed her for all time.

Browning kept a diary of her ailments, yet many questions remain unanswered about the source of her maladies. A Penn State anthropologist may have found the answer more than a century later.

Deciphering Browning’s Illness

Research associate in anthropology Anne Buchanan wanted to separate theory from plausible facts. The poet suffered from debilitating physical pain from age 13. Unable to diagnose or treat her symptoms, doctors drew up all sorts of hypotheses. From heart palpitations to anorexia and tuberculosis; some theorized the lifetime effects of injuries to her spine from falling from a horse.

Buchanan mentions some attributing Browning’s illness to defense against the inferior status and treatment of Victorian women. Interestingly, Buchanan’s daughter Ellen experienced similar symptoms to Browning. Diagnosed with hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HKPP), the disease is a muscle disorder that lowers blood potassium levels by trapping potassium in muscle cells.

There is no cure for the rare disorder. However, HKPP is genetic. Buchanan found slight evidence that an uncle in Browning’s family may have had similar symptoms.

While many experts have poured through Browning’s journals and diaries, none have come close to a definitive answer. An HKPP diagnosis could be the most likely prognosis.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Poetry of Elizabeth Barrett Browning:

A 19th-Century Analysis

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Opium TheoryIt’s no secret that Browning took laudanum, an opiate, to treat her chronic ailments. Historians believe its prolonged use led to opium addiction, eventually resulting in her spending her entire fortune on the drug.

In the 19th century, laudanum was the drug of choice. The alcohol-based medicine containing opium was frequently used until the early 1900s.

Dr Joseph Crawford, a senior lecturer at Exeter University, wrote extensively about its misuse among the great romantic poets and writers. Female writers, including Browning, referenced opium and other opiate type drugs in their works. She called it her “elixir” because of its “tranquilizing power.”

Unfortunately, her “elixir” may have contributed to her premature death. Theories abound for the cause — some cite heart failure; others an overdose.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Opioid addiction treatment todayAs we know, opioid addiction crisis has continued unabated. Whereas opium was previously painted as the villain, modern medicine is applying it to the greater good. Today, opium tincture-assisted treatment is used to treat opioid-use disorder.

Another effective treatment method is prescription medicine Suboxone. However, this option could soon be off the table in light of the Suboxone tooth decay lawsuit.

At the center of the lawsuit is the global pharmaceutical company Indivior. Thousands of plaintiffs claim Indivior failed to warn patients and healthcare providers about Suboxone’s oral health risks.

Patients who used Suboxone film suffered dental injuries, including severe tooth decay, erosion, and tooth loss, allegedly due to its acidic formulation. TruLaw says Suboxone lawyers are investigating claims that film testing was inadequate, and its dental risk warnings insufficient.

Opioid addiction remains a pressing issue today. Like Browning, other writers and artists used various forms of the drug to elicit euphoric emotions, inspiring some of their best works. Now that we know the detrimental effects, people are seeking effective opioid addiction treatment.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Keeping Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Legacy AliveElizabeth Barrett Browning inspired Emily Dickinson and Virginia Woolf and is considered one of the 19th century’s greatest poets. Long before the 20th-century feminist movements, Browning condemned barriers to women’s achievement in her seminal work, the book-length poem Aurora Leigh.

The British Library also recently acquired a series of letters written by Browning. The collection includes 131 letters dated after her “1844 Poems,” which brought her fame. Most are addressed to her sister, Henrietta Surtees Cook.

Browning was steadfast in her romantic outlook on life despite the trials and tribulations she faced. Despite her lifelong ill health, she prevailed and is remembered as one of the greatest poets that ever lived, especially as a paragon of Victorian poetry.

The post Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Mystery Illness: Theories and Conjectures appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 22, 2025

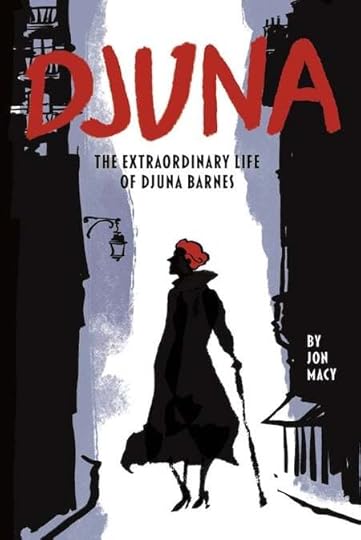

Fascinating facts about Djuna Barnes, author of Nightwood

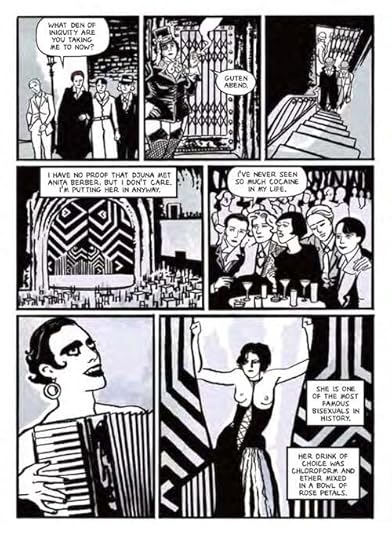

Djuna Barnes was a Modernist writer whose various talents and eccentricities made her unique. She went to great lengths to protect her privacy, so it’s not surprising that she had a whole closet full of skeletons. These fascinating facts about Djuna Barnes are presented by Jon Macy, creator of the graphic novel Djuna: The Extraordinary Life of Djuna Barnes.

Childhood trauma armored Djuna with a razor sharp wit, and an almost Ahab-and-the-whale, determination to succeed as a writer. Immensely talented, she was a journalist, poet, artist and novelist.

She became a celebrated star in 1920s Paris along with her friends James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, Ernest Hemingway, and Gertrude Stein. Her masterpiece, Nightwood, is one of the greatest lesbian novels ever written, and her influence on modern writers reverberates into the present.

Much of her allure comes from the mystery surrounding her self-isolation. Why did she turn her back on the world to live as a recluse for the last forty years of her life? Many have tried to find out, myself included. Here are a few things that struck me during my search to understand Djuna Barnes’ complex truth.

Djuna grew up in a cult-like family

Djuna grew up in a free love bohemian cult that abused her and then forced her into marriage at seventeen to get rid of her. It would be easy to portray her family as villains — they were in many ways, but they also had charm, ambition, and talent to spare.

Djuna’s grandmother, Zadel Barnes, was a pioneering journalist and activist. In 1879, she founded a London salon for writers, actors, abolitionists, reformers, and queers of all kinds. Her sphere included; William Morris, Eleanor Marx, Victoria Woodhull, and of course, Oscar Wilde.

Zadel was a talented grifter and free love advocate. She gifted Djuna with a wealth of literary intelligence, and taught her how female journalists can sidestep propriety when it suited their mission.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

In her days as a journalist, Djuna interviewed every famous person in early 1900s New York. Such luminaries included silent film star Alla Nazimova, Ziegfeld, Diamond Jim Brady (who kept his underwear in a safe), Coco Chanel who gave her a dress, and Jack Dempsey, the shy boxer.

She was well paid, but she chafed under the usual assignments. Djuna found celebrities shallow, so she changed their words to sound more engaging. None of them complained because she made them seem wittier than they were.

Djuna preferred to interview the offbeat and downtrodden. She challenged her editors by doing articles on legless elevator men, women cops who liked poetry, and Black acting troupes who could never get a break — people no one else would touch.

. . . . . . . . .

Djuna: The Extraordinary Life of Djuna Barnes by Jon Macy

(Street Noise Books, 2024) is available on Bookshop.org, Amazon*

& wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . .

Djuna’s father had two wives and many children in the utopian free love commune where she grew up. When her mother divorced her father, Djuna’s fractured half of the family landed in a windowless Bronx tenement, alone and destitute. She was homeschooled and unsocialized, yet fiercely precocious.

She demanded a job from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. She said, “I can write, I can draw, and you would be a fool not to hire me.” The fact that she could interview someone and draw their portrait meant she could get paid twice. Her ungrateful mother and three brothers would never have survived without her.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

A suicide landed right in front of herThe stock market crash of 1929 was devastating to the American expatriates in Europe. The jobs were gone and the reporters, including Djuna, lost everything.

Djuna was on her way to deliver her last article to an editor when a man’s body fell at her feet. He had jumped from the rooftop. His blood was all over the sidewalk and part of his brain splashed onto her fine tailored tweed skirt. She was so upset she had to lay in bed for three days to recover. The article, incidentally, was about fine dining.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Djuna Barnes’ masterpiece is her 1936 novel, Nightwood. It was praised by critics as a work of genius exemplifying late Modernism. It is also considered a finest work of lesbian fiction. The novel is famous for its lush poetic quality, often compared to an opera. A little-known fact is that Barnes wrote it in verse, then translated it into prose. She was a poet first, which gave her a uniquely powerful voice that carried into her writing.

It’s also known as the chewiest read in the English language, even surpassing James Joyces’s Ulysses for its unfathomable experimentations. Comparative literature professors have been known to assign Nightwood as a way to weed out the weaker students in their class. Once you know that Joyce was poking fun at us the whole time, Ulysses lets you in on its joke. Djuna Barnes poked society with intricate daggers.

She saved Patchin Place in Greenwich Village

Djuna lived on a little gated street in Greenwich Village called Patchin Place. It was cobblestoned, with beautiful ailanthus trees, and even had one of the last two original gas street lamps in New York City. Many famous people lived there, including e.e. cummings, Marlon Brando, and John Reed. By the 1970s, Djuna was the last one.

A developer tried to buy the charming little cul-de-sac intending to tear it down and build condos. At a public meeting, Djuna shouted down the developers and stopped the proceedings. She bellowed, in her high mid-Atlantic tone, “If lost, where would all the young muggers go to practice their trade?” Patchin Place was saved.

Ingmar Bergman almost made an adaptation of Nightwood

Djuna was incredibly difficult to work with; her legacy was sacred to her. The only people she respected were James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, and . Seven film companies approached her for the rights to adapt Nightwood into a film, but she always turned them down. All except Bergman. She trusted him, and there was talk of starring in it, which Djuna liked.

If the film had been made, Djuna Barnes would have been a household name, and her novel would have come back into print. However, it didn’t come to pass. It’s another tragedy for Djuna, and new generations who would have discovered her if Bergman could have brought her vision to the cinema.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Djuna was a major recluse who hated disruptionsDjuna was a recluse. She had lived in the same studio apartment for forty years. Few were allowed to enter, and those who did, like Anaïs Nin, inevitably wrote about the experience. Djuna was followed around Greenwich village by students doing their dissertations on her, but she chased them away waving her cane. She called them, “post graduate termites.”

Carson McCullers stuffed flowers in her mailbox. Djuna could be heard from her second story window saying, “whoever is ringing this bell please go the hell away.”

Cordelia Pearson tried to wheedle her way into Djuna’s life by hiring her to paint her portrait. Djuna refused, but complained about it to e.e. cummings and his wife. Djuna put a stop to all the shenanigans, but the woman wouldn’t give up. After endless love letters, she sat crying on Djuna’s doorstep until the police were called to take her away.

Even Djuna’s window cleaner would interrupt her writing by telling her that he had read her book, but didn’t really like it.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

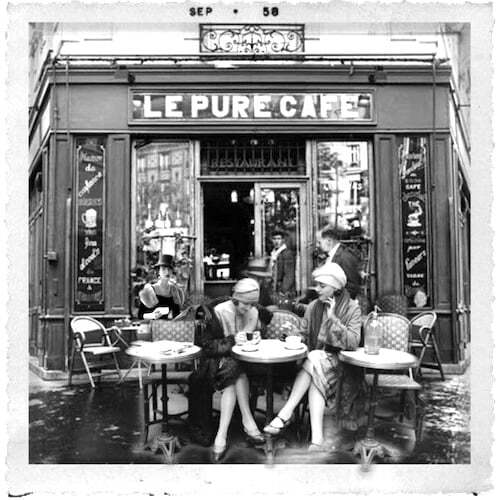

The famous photo purported to be Djuna isn’t actually of herA famous photograph of two fashionable women in front of a café in 1920s Paris has caption that always reads: “Djuna Barnes and Solita Solano in front of the Le Dome.” It is not them. They’re actually two Parisian models photographed by Maurice Branger (1874–1950) in front of Le Pure Café.

I have carefully studied the angular nose of Djuna Barnes for the last five years. Her clothes. Her style. The wicked black pumps. None of these match the nose, clothes, and style Djuna carefully cultivated to be her signature “genius writer” persona. In the image Djuna is apparently writing her masterpiece at a little iron café table, but it’s with her right hand; she was left handed.

Djuna Barnes is ready for her comeback. It is my hope that my graphic novel biography of this esteemed author assists in preserving her renown, and introduces her literary works to a new generation of readers.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Jon Macy, a graphic novel writer and artist. His most recent work, Djuna: The Extraordinary Life of Djuna Barnes, is now available from Street Noise Books. He admits he might be a little obsessed with Djuna Barnes. Find him at Jon Macy Graphic Novels and on Instagram, @nefarismo

*These are Bookshop.org and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased after linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps us keep growing.The post Fascinating facts about Djuna Barnes, author of Nightwood appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 11, 2025

10 Fascinating Facts About Ursula Parrott, Forgotten Author of Ex-Wife

Once the most renowned ex-wife in America, bestselling author Ursula Parrott (1899 – 1957) was routinely described as “famous” in her lifetime when the press covered her new books, Hollywood deals, marriages and divorces, and run-ins with the law.

As I detail in Becoming the Ex-Wife: The Unconventional Life & Forgotten Writings of Ursula Parrott, she published twenty books from the late 1920s through the late 1940s, several of them bestsellers, and over one hundred short stories, articles, and novel-length magazine serials.

Ursula Parrott piloted for the Civilian Air Corps during World War II; co-founded a weekly rural Connecticut newspaper with a group including American Newspaper Guild founder Heywood Broun and her literary agent George Bye; was an informant in a federal drug investigation; and travelled the world, including an extended story-collecting trip to Russia in the 1930s. And between all her writing and other adventures, she married (and divorced) four times.

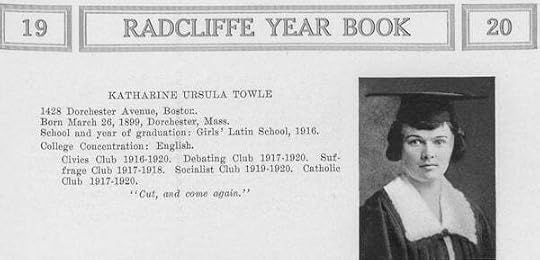

Born Katherine Ursula Towle, she was raised and educated in Boston and spent most of her adult years living in New York City, where she set many of her stories.

. . . . . . . . .

Becoming the Ex-Wife by Marsha Gordon

is available on Bookshop.org &

wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . .

After making hundreds of thousands of dollars writing — during the height of the Depression no less — Ursula lost it all, ending up homeless in the 1950s. Like many other influential, bestselling women writers, she was unfairly pigeonholed and dismissed as a romance magazine writer and her death in 1957 transpired with little notice.

I still wonder why Ursula’s contemporary Jazz Age writer, F. Scott Fitzgerald, is so much more famous than she, something about which I wrote for The Conversation (Why have you read ‘The Great Gatsby’ but not Ursula Parrott’s ‘Ex-Wife’?) and led a webinar for the National Humanities Center (Why You Should Start Teaching Ursula Parrott’s Ex-Wife).

Not one of her twenty novels remained in print until McNally Editions republished her 1929 bestseller, Ex-Wife, in 2023; it has now been translated into and republished in Italian, Swedish, Spanish, German, and Dutch.

. . . . . . . . .

Katherine Ursula Towle’s Radcliffe College yearbook photo, 1920

Courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute

. . . . . . . . .

She Skipped Classes, Cheated on Papers,and Almost Didn’t Graduate from Radcliffe College

Katherine Ursula Towle was one of seventeen girls from the 1916 class at Boston’s Girls’ Latin School to take honors in her Radcliffe entrance examinations, despite a lackluster work ethic and mediocre grades in high school. At Radcliffe, she was chronically late to classes but demonstrated intellectual promise on the rare occasions that she applied herself.

Midway through her studies, in 1918, the chairman of the academic board at Radcliffe sent her father a letter telling him that Katherine needed to get her act together. The chairman reminded Dr. Towle that “in order to get the degree from Radcliffe, a student must pass in at least seventeen courses with grades above ‘D’ in two-thirds of them.” In her freshman and sophomore years, Katherine had, in fact, earned Ds in German, history, botany, and even in her major —English.

Dr. Towle must have made his displeasure known, since his daughter turned things around enough to successfully earn her English degree on June 23, 1920. Still, Radcliffe’s 1920 yearbook reads: “I don’t suppose Katharine [sic] Towle is here; she is probably cramming at the Widow’s.” The class president also dedicated a bit of doggerel to Kitty (as she was nicknamed):

She cut classes all during the year,

Her finals then filled her with fear.

At the Widow’s she learned

What from profs, she had spurned,

A proceeding most queer.