Nava Atlas's Blog, page 15

November 3, 2023

The Banning of Nadine Gordimer’s Anti-Apartheid Novels

Nadine Gordimer (1923 – 2013) was a South African activist and Nobel Prize-winning author. Presented here is an overview of the banning of Nadine Gordimer’s anti-apartheid novels and other writings, and her legacy as one of the most prominent and outspoken authors of the anti-apartheid movement.

Gordimer was born in Springs, South Africa to Jewish immigrant parents. Her early experiences informed the rest of her life, including witnessing a raid on her family home where a servant’s letters and diaries were confiscated.

Her first novel, The Lying Days, was published in 1953 when apartheid-era censorship by the South African government was at its height.

The Publications Act

According to UCT News, between 1950 and 1990, a total of 26,000 books were banned under the Publications Act of 1974. Governmental bans affected theatre performances, films, television, and books. This reverberated through arts and communication.

Even internationally famous musicals like Hair and Jesus Christ Superstar were banned for reasons of supposed blasphemy. The book Black Beauty was banned merely for including the word “black” on the title page.

After publishing The Lying Days in 1953, Gordimer befriended activists like Bettie du Toit. She cited du Toit’s intentional arrest during a protest action as one of her early inspirations.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Nadine Gordimer

. . . . . . . . . . .

Gordimer’s first official ban under the Publications Act law was The Late Bourgeois World, published and banned in 1966. Times Live mentions other books that were banned that year, including Miriam Tlali’s Between Two Worlds (1975) and Es’kia Mphahlele’s Down Second Avenue (1959).

Banned books were completely barred from being read, and couldn’t be sold or shared. If anyone was caught with a banned text, they would be severely punished.

The government ban stretched internationally, and effecting books like The Satanic Bible by Anton LaVey (1969), and other texts that could be seen as anti-religious or against the political views of the time. Even musical artists like Pink Floyd became contraband for being seen as too anti-establishment for local ears.

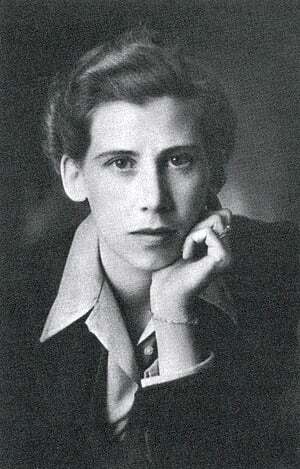

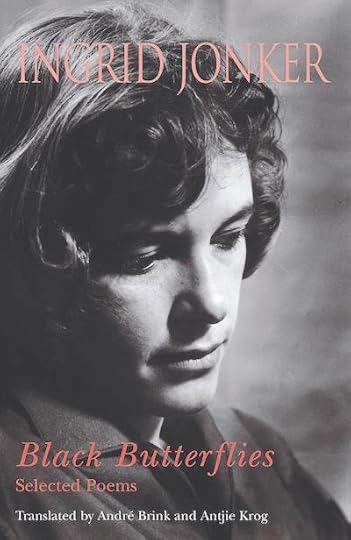

Renowned poet Ingrid Jonker’s father, Abraham, was one of the prominent National Party figures responsible for banning laws of the time. Abraham headed the censorship commission and had his own staunch opinions on Ingrid’s work. He possibly had his own bias against Gordimer’s writing as well.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Burger’s Daughter: banned and unbannedBurger’s Daughter was the second of Gordimer’s works to be banned by the South African apartheid government. The book was partially inspired by her friendship with anti-apartheid lawyers and friends of Nelson Mandela.

In 1979, the book was published and simultaneously banned by the apartheid government’s censorship committee. According to a QZ feature, South Africa’s government of that time would proceed to burn many books in the face of bans, too.

The New York Times reported the book’s ban being canceled in October of the same year: The Government Publications Appeal Board decreed that the book was “inflammatory” rather than harmful and the ban was lifted.

1980: What Happened to Burger’s Daughter

Gordimer couldn’t forget or forgive the government’s stance against her work. In 1980, she published a collection of essays recounting the book’s ban the prior year.

What Happened to Burger’s Daughter (or How South African Censorship Works) is a collection of essays by Gordimer and others.

The text explored the reasons for the apartheid-era ban against her work, and the greater impact this might have had on her writing. In this work, she examines the unfairness of governmental literature bans, and why her work (and others) were banned for no good reasons.

The book’s second chapter, written by the head of the Publications Board, is called “Reasons for the Ban.”

Her next book to be subjected to bans was July’s People, published in 1981 before South Africa eased strict censorship laws. July’s People envisioned a future South Africa where apartheid was ended through a civil war — a concept that the government deemed too dangerous to exist in print.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

South African bans against other artsIn 1984, musicians including Queen protested governmental censorship laws by performing at the Super Bowl in Sun City (located in what was then called Bophuthatswana). Many South Africans traveled to attend, going against laws that didn’t allow them to see the performance (or know the music).

The government’s stance on censorship also affected other arts. Cabaret artist Amanda Strydom famously used the Black Power salute on stage in 1986 during a concert, to the immediate displeasure of the government.

Gordimer continued to write on contentious topics. A Sport of Nature (1987) explored the story of a girl who changes her name to Hillela and subsequently joins the African National Congress (ANC) to marry a member.

Nadine Gordimer’s book bans lifted

Gordimer’s Nobel speech in 1991 mentions A Sport of Nature as a “most hazardous undertaking” under active literature bans.

Laws were revised after 1994, including the Films and Publications Act (65 of 1994), which lifted prior prohibitions on what South Africans were allowed to read and see. Modern censorship laws in Southern Africa are focused on responsible content regulation.

At the time of her death, all of Nadine Gordimer’ books had been unbanned and are available for anyone to read.

Contributed by Alex J. Coyne, a journalist, author. and proofreader. He has written for a variety of publications and websites, with a radar calibrated for gothic, gonzo and the weird. His features, posts, articles and interviews have been published in People Magazine, ATKV Taalgenoot, LitNet, The Citizen, Funds for Writers, and The South African, among other publications.

More about Nadine Gordimer

SA History: Nadine Gordimer Britannica: Nadine Gordimer The Guardian: Obituary for Nadine Gordimer Nobel Prize: Nadine Gordimer, 1991The post The Banning of Nadine Gordimer’s Anti-Apartheid Novels appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 24, 2023

Enid Blyton, Prolific & Controversial Children’s Book Author

Enid Blyton (August 11, 1897 – November 28, 1968) was a prolific British writer of children’s stories. Her most famous books include The Famous Five and Secret Seven series, The Faraway Tree, and the Noddy books.

She is believed to have written around seven hundred books altogether, along with hundreds of short stories, magazine articles, and poems.

Her work is controversial for its often dated and sometimes offensive views, yet decades after her death she remains one of the most popular children’s authors in the world.

Early life and education

Enid Mary Blyton was born in East Dulwich, London. She had two younger brothers, Hanly and Carey

Her father, Thomas, was a clothing wholesaler. She had a close and loving relationship with him, sharing his love of the outdoors, the theatre, art, music, and literature. In her 1952 autobiography, The Story of My Life, she describes her father’s willingness to take her for walks, writing that they were:

“… marvelous to me. It’s the very best way of learning about nature if you can go for walks with someone who really knows,” and recalled these times as “the happiest times, when looking back it seems the days were always warm and sunny and the skies were deeply blue.”

Her mother, Theresa, was a housewife. Enid’s relationship with her was more difficult, partly because her mother didn’t share the love of art and the outdoors and resented how Thomas encouraged Enid to spend time on these pursuits. Instead, she expected Enid to help with housework.

Shortly after Enid was born, the family moved to Beckenham in Kent. It was here that Enid went to school, initially to a small school run by two sisters in a house called Tresco, and then later to St. Christopher’s School for Girls, where she was Head Girl in her final two years. She was, by all accounts, bright and popular, and excelled at art and literature.

Despite her warm relationship with her father, Enid’s home life, wasn’t so happy. Her parents’ marriage was full of anger and frustration. When Enid was not quite thirteen her father announced that he was leaving. He moved out and took up residence with another woman, Florence Agnes Delattre.

Since separation and divorce were considered scandalous at the time, especially in the conventional English Kent countryside, Theresa forced Enid and her brothers to pretend that their father was simply away for a short while. This pretense, which the family kept up for years, had a lasting effect on Enid, who took her father’s departure as a rejection of her personally.

With the atmosphere at home strained, she spent more and more time writing in her room. Her mother despaired of her efforts at writing, which were rarely published and which she deemed a waste of time.

Teaching, and a writer’s beginnings

It was assumed Enid would attend music college and become a professional musician like her aunt (her father’s sister, May Crossland). However, feeling that her talents lay in writing, she determined to train as a teacher instead, where she would be in constant contact with children — her future audience of readers.

In September 1916, she enrolled in a teacher training course at Ipswich High School. It was around this time that she broke ties completely with her mother, spending holidays with friends rather than returning home. Although she kept in touch with her father, she was never able to accept his new family, and they were never as close as they once were.

After completing her teacher training in December 1918, Enid taught for a year at a boys’ school in Kent before becoming a governess to four young boys in Surbiton, Surrey. She remained there for four years, and later said it was “one of the happiest times of my life” despite the death of her father in 1920 from a stroke.

By the early 1920s, Enid was also beginning to have some success with her writing. Stories and articles were accepted for publication in various magazines, and she also wrote verses for greeting cards. By 1923 she had written and published more than a hundred stories, reviews, and poems.

Marriage and family life

On August 28, 1924, Enid married Hugh Alexander Pollock, an editor at the publishing company George Newnes. The wedding took place at Bromley Register Office, with neither Enid’s family nor Hugh’s family in attendance.

The couple honeymooned in Jersey. Later, Enid would base Kirrin Island (one of the places in the Famous Five series) on this island experience.

The early years of the marriage were happy and serene, spent mostly at Elfin Cottage in Beckenham. Hugh was supportive of Enid’s work and instrumental in publishing her stories at Newnes. In 1927, he also persuaded her to begin using a typewriter; before that, she had written all her stories in longhand.

In 1929 they moved to Old Thatch, a 16th-century thatched cottage in Bourne End, Buckinghamshire, very close to the River Thames. Enid described it as “a house in a fairy tale” and with the large gardens was able to indulge her passion for pets (which she had never been allowed as a child). At various times there were dogs, cats, hedgehogs, goldfish, pigeons, hens, and ducks roaming around the grounds.

In July 1931, the couple had a daughter, Gillian. After a miscarriage in 1934, a second daughter, Imogen, was born in October 1935.

Neither Enid nor Hugh spent much time with the children. Enid was busy with her writing and relied on domestic help for things like gardening, childcare, and cooking. Hugh had been working with Winston Churchill on his writings about World War I. He increasingly fell into depression as he realized how close the world was to entering another war.

Hugh began to drink, doing so while hiding in a cupboard underneath the stairs, and Enid retreated ever further into her writing. Her only real friend and confidante was Dorothy Richards, a maternity nurse who had helped with Imogen’s birth.

In August 1938, perhaps thinking that a move would help to give the family a chance, Enid bought a new house in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire — a much larger, newer eight-bedroom house, designed in a mockTudor style, which she called Green Hedges.

Second marriage

During the war years, Enid continued to write, while Hugh rejoined his old regiment, the Royal Scots Fusiliers, and was sent to Dorking in Surrey to train new officers. The separation put another strain on the marriage. While on holiday with Dorothy in Devon in 1941, Enid met Kenneth Waters, a surgeon.

In 1942, she and Hugh were divorced, and she married Kenneth in the City of Westminster Register Office in October 1943. Although she had promised that Hugh would be able to see his two daughters after the divorce, she went back on her word inexplicably, and the two girls never saw their father again.

In The Story of My Life, photographs of the family include Enid, Kenneth, Gillian, and Imogen. There is no mention of Hugh at all — as if he’d never existed.

Enid and Kenneth were largely happy together, but later, Enid’s daughters would each have very different recollections of their childhood and their mother.

In an interview with the author Gyles Brandreth, Gillian said that Enid could “communicate with children in a quite remarkable way… She was a fair and loving mother and a fascinating companion.”

Imogen, on the other hand, while acknowledging that “what [Enid] did as a writer was brilliant,” remembered her mother as “arrogant, insecure, pretentious, very skilled at putting difficult or unpleasant things out of her mind, and without a trace of maternal instinct.”

The family spent most of their holidays in Dorset, where they bought a farm in the 1950s, Manor Farm in Stourton Caundle. This setting provided much of the inspiration for the Famous Five books later on.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Making a successful careerIn the late 1920s and early 1930s, Enid worked mostly on educational books. She began writing and editing a fortnightly magazine, Sunny Stories for Little Folks and published her first full-length novel, The Enid Blyton Book of Bunnies (later renamed The Adventures of Binkle and Flip) in 1925.

By the 1940s she had given up much of her magazine writing and was concentrating on books. Her first full-length novel for children, The Secret Island, was published in 1938 and became the start of a series.

While her daughters were at boarding school, she began most of what would become her most famous series of books, such as The Famous Five books, the Adventure series, the St Clare’s series, the Faraway Tree, and the Wishing Chair series.

Later, these would be joined by the Secret Seven series, Malory Towers, and the Six Cousins books. Often Enid would publish up to twenty books in a single year.

1949 saw the appearance of the first Noddy book, Noddy Goes to Toyland, about a little wooden boy and his companion, Big Ears. It was the first of at least two dozen books in the same series that was enormously popular during the 1950s, with an extensive range of spin-offs, comic strips, and merchandise.

In 1950, she established a company, Darrell Waters Ltd. (taking Kenneth’s middle and last names) to deal with the financial and business side of things. Her prolific output remained constant, and by 1955 she had published the fourteenth Famous Five novel (Five Have Plenty of Fun), the eighth book in the Adventure series (The River of Adventure), and the seventh Secret Seven novel (Secret Seven Win Through).

Enid intended her books and stories for a wide range of ages, children between the ages of two and fourteen. She wrote adventure and mystery stories, school stories, animal stories, fantasy, fairytales, and nursery stories. Altogether, it’s estimated that she wrote about 700 books for children and about 2,000 short stories, as well as poems and magazine articles.

In a letter to the psychologist Peter McKellar, Enid described her writing technique:

“I shut my eyes for a few minutes, with my portable typewriter on my knee — I make my mind a blank … and then, as clearly as I would see real children, my characters stand before me … The first sentence comes straight into my mind, I don’t have to think of it — I don’t have to think of anything.”

The sheer volume of writings that she produced led to rumors that she employed an army of ghostwriters, a charge that she vehemently denied and that she eventually took legal action on.

She believed her stories came from her “under-mind” as opposed to her conscious mind, although her daughter Gillian also said that it was important for Enid to give her young readers a “strong moral framework in which bravery and loyalty are (eventually) rewarded.

Charity work

In 1953 Enid launched an eponymous fortnightly magazine, Enid Blyton’s Magazine. She wrote all the contents herself, except for paid advertisements, and the magazine launched four clubs that readers could join: the Busy Bees (which raised money for the PDSA pet charity), the Famous Five club (which raised money for a children’s home), the Sunbeam Society (which helped blind children) and the Magazine Club (which helped children with cerebral palsy).

The magazine folded in 1959, but in those six years, the clubs had a total of around half a million members and had raised about £35,000 (almost £1.5 million today).

. . . . . . . . . . .

When the Present Clashes with the Past:

Reminiscences of Enid Blyton

. . . . . . . . . . .

Despite Enid’s popularity, she was not without her critics. Many teachers and parents (along with literary critics) were dismissive of her work even at the time it was published, saying that it didn’t challenge young readers enough and that its literary merit was limited.

Later, particularly in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when a more progressive society was beginning to emerge, her books were also criticized for being elitist, sexist, racist, and xenophobic. They were banned by many libraries and schools that removed them from shelves. The children’s book critic Margery Fisher likened Enid’s books to “slow poison.”

These accusations have grown over the years. According to the academic Nicholas Tucker, Enid’s works have been “banned from more public libraries over the years than is the case with any other adult or children’s author.”

From the 1930s until the 1950s, the BBC refused to broadcast her stories: Jean Sutcliffe of the BBC Schools Broadcast department wrote that Enid’s books were “mediocre material” that were churned out too fast, and that “her capacity to do so amounts to genius … anyone else would have died of boredom long ago.”

Not long ago, some revisions were made to modernize some of the language in Enid Blyton books, notably the Famous Five series. These revisions proved to be a flop, and the original language was restoreed.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Final yearsBy the time that Enid Blyton’s Magazine ended, she was writing less and spending more time with Kenneth, who had retired as a surgeon in 1957. He suffered from arthritis, and the medicine he took damaged his kidneys. He died in 1967, while Enid herself was struggling with poor physical health. She had experienced bouts of breathlessness, had suffered a heart attack, and descended into dementia.

Enid continued to live at Green Hedges, cared for by staff, until this was no longer possible. She was transferred to a Hampstead nursing home in the summer of 1968. She died in her sleep on November 28, 1968, and was cremated at Golders Green in North London.

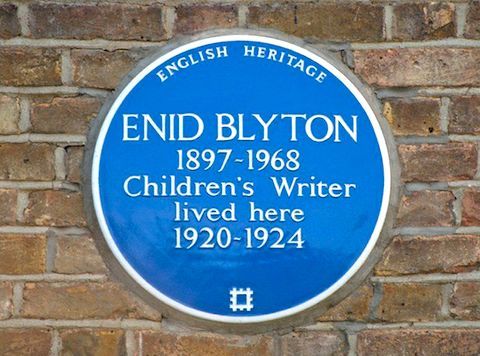

Her home, Green Hedges, was demolished in 1973, and the street of houses built on the site is called Blyton Close. In 2014, a plaque commemorating her time living in Beaconsfield was unveiled in the town hall gardens, along with small statues of Noddy and Big Ears.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Enid Blyton’s legacyThe majority of Enid’s books are still in print, with sales of more than 500 million copies. Her works have been translated into some ninety languages.

Several of her series have been continued by other authors, and some have been successfully adapted for television, film, and the stage, including Malory Towers, The Famous Five, Noddy, and The Faraway Tree.

Her life was itself the subject of a BBC film, broadcast in 2009, starring in the title role.

However, many of her books have also been heavily edited in recent years to remove offensive terms about race, appearance, and class. The criticism that she faced at the time of publication is even stronger today.

In 2016, the Royal Mint blocked a proposal to honor Enid Blyton with a commemorative 50p coin owing to her reconsideration as a “racist, a sexist and a homophobe.” It’s a conflicting legacy for the writer who introduced — and continues to introduce — generations of children to the joys of reading.

Today, the bulk of Enid’s collection of manuscripts and papers is held by the Seven Stories National Centre for Children’s Books in Newcastle upon Tyne.

The Enid Blyton Society was formed in 1995. It issues the Enid Blyton Society Journal three times a year, holds an annual Enid Blyton Day, and has a comprehensive website which delves into the different series of books and includes forums and quizzes.

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Enid BlytonOn this site

When the Present Clashes with the Past:Reminiscences of Enid Blyton

Major works

Almost all of Enid Blyton’s books for children are still in print (although many have been edited from the original versions). See a complete bibliography here.

Biographies

Enid Blyton: The Biography by Barbara Stoney (2006)101 Amazing Facts About Enid Blyton by Jack Goldstein (2020)Enid Blyton: A Literary Life by Andrew Maunder (2021)The Real Enid Blyton by Nadia Cohen (2022)Controversy

Why it’s Important to Note Enid Blyton’s Failings, Not Erase Her Work Enid Blyton Fans React to ‘Racist’ Label Enid Blyton: Heritage Bosses Respond to Racism, etc. English Heritage Has No Plans to Remove PlaqueThe post Enid Blyton, Prolific & Controversial Children’s Book Author appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 12, 2023

Nadine Gordimer, South African Author and Activist

Nadine Gordimer (November 20, 1923 – July 13, 2013) was a South African activist and Nobel Prize-winning author. Her short stories and long form fiction explored themes of alienation, apartheid, and exile in the context of South African people.

She published her first short story collection in 1949, and her first novel,The Lying Days, in 1953. Many of her works, including July’s People and Burger’s Daughter, were banned by the apartheid government at the time they were published.

In addition to the Nobel Prize for Literature, the Commonwealth Writer’s Prize, and countless other awards and honors, she cofounded the Congress of South African Writers (COSAW) and was a notable member of the African National Congress (ANC).

Her lifetime was devoted to political and social causes, including being a friend to many stalwarts of the anti-apartheid struggle in their time of need.

Early life and literary beginnings

Nadine Gordimer was born in 1923 in Springs, South Africa, a small mining town that’s about thirty miles from Johannesburg, Gauteng. She was the daughter of Jewish immigrants Isidore Gordimer (from Latvia) and Nan Myers (from the United Kingdom).

A privileged upbringing gave her secure foundation, and she began writing from the age of nine. By 1937, she was a published teenage author in the Sunday Express.

She went to school at the Convent of Our Lady of Mercy in Springs between ages eleven and sixteen. She was later removed from the school, and went to live with family.

She enrolled for college studies at the University of Witwatersrand, but left after a year to pursue writing. Her stories continued running in South African newspapers and magazines.

First collection and debut novel

Gordimer’s first short story collection published in 1949 via now-defunct Johannesburg publisher Silver Leaf Books. The rare collection Face to Face explored how apartheid affected South Africans, setting the tone for much of Gordimer’s lifetime work.

Her next short story collection was published in 1952. Its eponymous story, The Soft Voice of the Serpent, tells of a man contemplating the loss of a limb while sitting in his garden.

Her debut novel, The Lying Days, appeared in 1953. The book draws from her life experiences; it takes place in a small town and is written from the perspective of a South African woman named Helen Shaw. The Lying Days is considered a coming-of-age novel, as the protagonist discovers life and truth outside her small hometown.

Gordimer’s work quickly caught public attention, dealing with themes like racial separation and crossing boundaries. Her work would soon also catch the South African government’s attention and became the object of frequent bannings.

Life after early publications

Gordimer was married to Gerald Gavronsky from 1949 to 1952. She married again in 1954, staying married to art dealer Reinhold Cassirer until his death in 2001. Famous in his own right, he established the South African branch of the auction house Sotheby’s, and would later run his own art gallery.

The New Yorker published Gordimer’s short story, A Watcher of the Dead, in 1951. She maintained this editorial relationship, writing several stories for The New Yorker during her career.

After friend Bettie du Toit’s arrest during a protest action, Gordimer became more involved in anti-apartheid causes and social activism. Gordimer joined the African National Congress (ANC) and continued to show support through her writing.

She was a friend to many anti-apartheid figures, including Nelson Mandela. In 1963 – 1964, she created biographical sketches for The Guardian of Nelson Mandela and his co-accused at the famous Rivonia Trial. Gordimer also assisted Mandela in writing his famous “I Am Prepared to Die” speech.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Banned and continuing to writeGordimer published The Late Bourgeois World in 1966. It was the first of her books to be banned under government censorship. Touching on sensitive topics, it was written from the perspective of a pompous South African white woman.

More of her work written during the apartheid era was the object of bans by the government, notably July’s People and Burger’s Daughter. This intentionally created a difficult environment for politically inclined writers of the time.

In the 1960s to 1970s, Gordimer spent time away from Southern Africa teaching in United States schools. Gordimer went back to South Africa after this period, returning to write.

In 1961, she received the W.H. Smith Commonwealth Literary Award for her work.

From City Lovers to BBC’s Frontiers

Gordimer’s story, City Lovers, was published in The New Yorker in 1975. The story later became a 1982 film starring Joe Stewardson and Denise Newman in the lead roles.

The famously banned novel Burger’s Daughter was published in 1979. She wrote the book as a coded tribute to a friend who had been one of Nelson Mandela’s attorneys during the Rivonia Trial. She would later write an essay about the book’s banning, “What Happened to Burger’s Daughter.”

In 1989, Gordimer contributed an episode (Gold and the Gun) to Frontiers, a BBC show also featuring authors John Wells and Frederic Raphael. The show coincided with the fall of the Berlin Wall, a highly political time.

When Nelson Mandela was released from prison just a year later in 1990, he asked for Gordimer to be one of the first people he wanted to see.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Post-apartheid writingsHer post-apartheid work centered around themes of an evolving political landscape, such as that of guns, their impact, and the legal implications. The House Gun (1998) explored the topic of “house guns” as commonplace as “house cats” in the country at the time.

Gordimer would continue to be one of the most prolific, politically-charged fiction writers of the age. Her work won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1991, adding to her repetoire of writing awards.

A novel exploring alienation and human relationships called The Pickup appeared in 2001. This time, she explored a romance between the characters Julie and Abdu. When Abdu isn’t allowed to stay in South Africa, Julie joins him as an outsider in his country with little context for its new culture and customs.

Telling Tales (2003) is a result of Gordimer’s activism, collecting her own stories along with other Nobel winners and authors into one volume. Proceeds from the book were donated to HIV/AIDS-related causes. During this time, she was especially critical of President Thabo Mbeki’s public stance on the disease.

Get a Life (2005) tells the story of an anti-nuclear activist protesting against a nuclear plant in his town. This is contrasted with his personal life, while the character receives chemotherapy cancer treatment, which gives rise to mixed feelings about its impact.

An unauthorized biography of Gordimer was published against her wishes in 2006. While No Cold Kitchen had her cooperation at first, she later claimed that the author breached her trust for the purpose of writing the book. Later that year, Gordimer left South Africa to lecture at the University of Toronto.

Beethoven was one-sixteenth black (2007) was her next story collection, followed by her last novel No Time Like the Present (2012). The latter revisits a racially mixed romance set in post-apartheid South Africa.

. . . . . . . . . .

Gordimer in 2019 (photo: Wikimedia Commons)

. . . . . . . . . . .

In addition to receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature, Gordimer was bestowed the French Legion of Honor award in 2007 for her contributions to literature. Her awards and honors are too numerous to list here; get a full picture here.

Nadine Gordimer died at age ninety in 2013, reportedly in her sleep at her home in Johannesburg. Her legacy as literary stalwart is well regarded, with much of her work recorded in the South African National Archives.

The Nadine Gordimer Short Story Award is named in her memory, and makes up the greater South African Literary Awards. Her 92nd birthday was posthumously celebrated with a Google Doodle.

Contributed by Alex J. Coyne, a journalist, author, and proofreader. He has written for a variety of publications and websites, with a radar calibrated for gothic, gonzo and the weird. His features, posts, articles and interviews have been published in People Magazine, ATKV Taalgenoot, LitNet, The Citizen, Funds for Writers, and The South African, among other publications.

More about Nadine GordimerNovels

The Lying Days (1953)A World of Strangers (1958)Occasion for Loving (1963)The Late Bourgeois World (1966)A Guest of Honour (1970)The Conservationist (1974)Burger’s Daughter (1979)July’s People (1981)A Sport of Nature (1987)My Son’s Story (1990)None to Accompany Me (1994)The House Gun (1998)The Pickup (2001)Get a Life (2005)No Time Like the Present (2012)Other works

In addition to the novels listed above, Nadine Gordimer published numerous collections of short stories, essays. See a nearly complete bibliography here.

More information and sources

SA History Britannica National Archives (SA Government) Nobel Prize (1991: Literature) New World EncyclopediaThe post Nadine Gordimer, South African Author and Activist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 9, 2023

Music in the Street by Vera Caspary (1929)

Music in the Street (1929) was one of three novels by Vera Caspary, a remarkably prolific American novelist, playwright, and screenwriter all released in the same year, along withThe White Girl and Ladies and Gents.

This analysis of Music in the Street by Vera Caspary is excerpted from A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth ©2022. Reprinted by permission.

Mae Thorpe moves away from her small-town family into a working girls’ home in Chicago, where at first, she is one of the unpopular girls with no boyfriend who stays home on a Saturday night.

Mae finds a man, though he is by no means the kind of boy the popular girls would envy: Olyn is an artist, an intellectual, shy, socially awkward, and worst of all, poor and living at the YMCA.

“While Olyn was regarded suspiciously by the more hilarious because he neither smoked nor drank, he was accepted as Mae’s boyfriend. The girls teased her about him, made fun of his large collars and long neck, mocked his slow, serious manner of speaking, but they expected Mae to marry him.”

Still, despite Olyn taking her to the Art Institute of Chicago and other places her housemates would sneer at, when the phone rings at Rolfe House and her name is called, Mae feels as though she has finally made it.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Vera Caspary

. . . . . . . . . .

“Mae stepped forward with an air of importance. She was being called by her boyfriend and she had a large audience.” And when they go out together, Mae feels she has become part of the life of the city at last.

She was happy. She was a color in the spectrum, a figure in the parade. The lights winked merrily as if they knew how wonderful it was to be a girl going somewhere in the city with her boyfriend.

Mae hears music in the street. But the relationship has difficulty progressing. Since both of them live in hostels, there is no chance for them to be alone, no privacy anywhere. It is a long time before they even kiss.

After much argument she allowed him to press his eager timid lips against her lips while he breathed heavily through distended nostrils to show his rapture.

. . . . . . . . . . .

A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie is available on

Amazon (US) and Amazon (UK)

. . . . . . . . . . .

But then someone far more romantic comes along – Boyd Wheeler, a salesman. He has been coming into the drugstore where Mae works on a regular basis and she has always liked him, but never had the courage to talk to him. Eventually one of her friends from Rolfe House introduces them. He takes her out – to a theatre and a restaurant rather than an art gallery. Boyd wastes no time, even though this is the first date.

In the taxicab he kissed her. She knew it would have been better if she turned her head away. She knew it was not right for him to kiss her so fervently the first time he took her out. But with his lips hard against her lips, with his cheek brushing her cheek with its burning masculine roughness, she had no strength for resisting. He was an insolent lover and she was happy.

Boyd is clearly not going to give up until he gets his way, and eventually he does. After only a few more dates, he takes her to a seedy hotel. Mae cannot have any doubt about what is inevitably going to happen when she gets there, “but her body stiffened and she held him at a distance. She was frightened.”

Mae still doesn’t run away. Here is Caspary’s bleak description of a young single virgin giving herself to a man before marriage at the end of the 1920s.

There was a crack in the wallpaper. She stared at it as if she were fascinated by the thin jagged line of the crack. The room vanished. All she could see was the wallpaper with its faded flowers and the ugly brown crack. Minutes passed. Years passed.

Boyd moved. The bed spring creaked.

Mae turned her head. She saw Boyd sitting there fingering the knot in his brown tie. Like a person who has been unconscious she was suddenly aware of the room around her and the iron bed and Boyd’s raccoon coat hung carefully on the costumer. She looked intently at her lover. She saw his short nose and his proud crest of curly hair.

“You’ve got naturally curly hair,” she heard her voice saying. “I love naturally curly hair.” Then Boyd took her in his arms and she was afraid no longer.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: Laura by Vera Caspary

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth-Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938; High Collars & Monocles: 1920s Novels by British Female Couples.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young Adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Vera Caspary

The Secrets of Vera Caspary, the Woman Who Wrote Laura Jewish Women’s Archive Wikipedia Reader discussion on Goodreads Dolls and Dames — Laura by Vera Caspary The Broadcast 41The post Music in the Street by Vera Caspary (1929) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 7, 2023

7 Literary Cocktail Books: Boozy, Punny Tributes to Famous Authors

Some of us find that books are natural partners with coffee, but a small, feisty group of literary cocktail books prove that literature and booze are inextricably intertwined as well.

These literary cocktail books aren’t so much about the true history of famous authors and their drinking habits, but punny tributes to them and their works. I guess it makes sense — after all, many writers led booze-soaked lives.

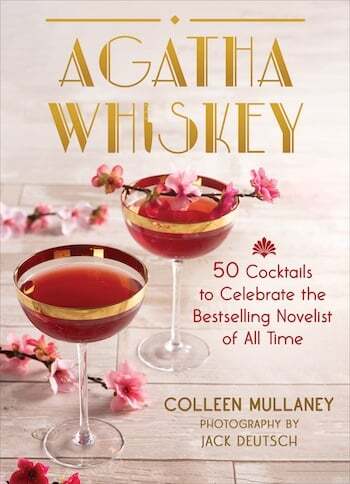

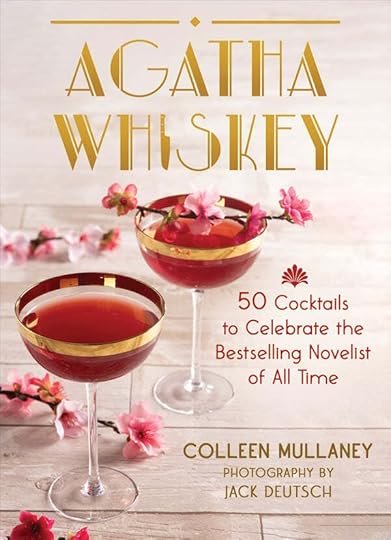

The genre of literary cocktail books took off with Tim Federle’s Tequila Mockingbird, and is going strong with Agatha Whiskey by Colleen Mullaney

These beautifully packaged books, filled with real recipes for cocktails (and sometimes mocktails) as well as fascinating literary history, are perfect gifts for the book loving cocktail connoisseur in your life.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Agatha Whiskey

Agatha Whiskey: 50 Cocktails to Celebrate the Bestselling Novelist of All Time by Colleen Mullaney (Skyhorse, 2023). From the publisher: A celebration of Agatha Christie’s timeless murder mysteries, killer short stories, suspenseful plays, and unmatched characters—with cocktails that are so tantalizingly delicious, it must be a crime.

Dame Agatha Christie is perhaps the world’s most famous mystery writer with over a billion copies of her books sold. Agatha Whiskey takes clues from Agatha’s most pivotal works of fiction and honors her most popular detectives, Hercule Poirot and Miss Jane Marple.

There’s a plot twist for everyone with fifty thrilling drinks such as a pocket full of rosé, orient espresso martini, and daiquiri on the Nile. There are also detective drinking games to get the whole party on the right track, perhaps sipping until there were none, and mocktails for those who choose to forgo an endless night.

Just like Agatha, Agatha Whiskey is here to entertain, inspire, and add some drama of the right sort to your life. Sample Passion Fruit Martinis, and read a Q & A with the author.

. . . . . . . . . . .

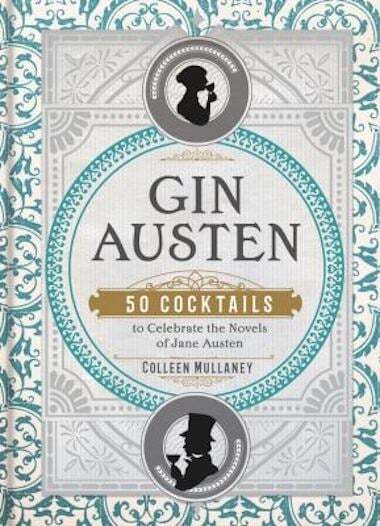

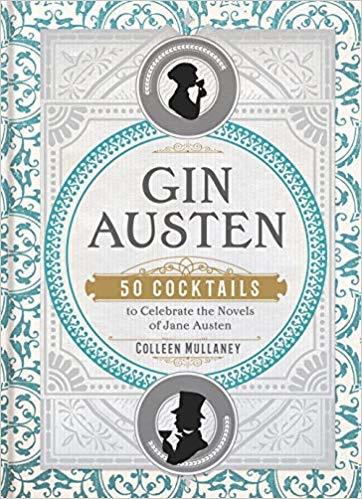

Gin Austen

Gin Austen: 50 Cocktails to Celebrate the Novels of Jane Austen by Colleen Mullaney (Union Square & Co., 2019). From the publisher: It is a truth universally acknowledged that a person in possession of this good book must be in want of a drink.

Discover an exotic world of cobblers, crustas, flips, punches, shrubs, slings, sours, and toddies, with recipes that evoke the past but suit today’s tastes. Raise your glass to Sense and Sensibility with a Brandon Old-Fashioned, Elinorange Blossom, Hot Barton Rum, or Just a Dashwood.

Toast Pride and Prejudice with a Cousin Collins, Fizzy Miss Lizzie, or Salt & Pemberley. Brimming with enlightening quotes from the novels and Austen’s letters, beautiful photographs, and period design, this intoxicating volume is a must-have for any devoted Janeite. Learn more about Gin Austen, with a recipe for Gin and Bennett.

. . . . . . . . . . .

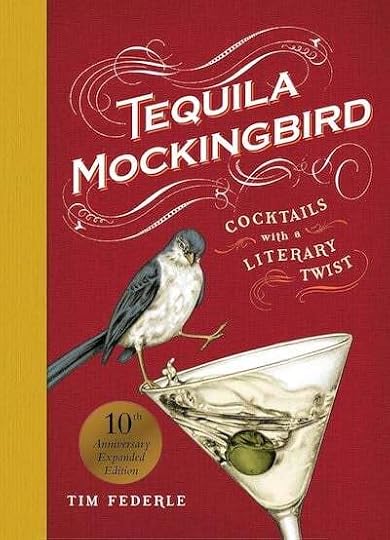

Tequila Mockingbird

Tequila Mockingbird: Cocktails with a Literary Twist (10th Anniversary Expanded Edition) by Tim Federle (Running Press, 2023) From the publisher: Celebrate the 10th anniversary of Tequila Mockingbird with this special new, expanded edition! This clever cocktail guide pairs cherished novels with both classic and cutting-edge drink recipes—no B.A. in English required.

It’s been ten years since the world’s bestselling cocktail recipes book, Tequila Mockingbird, captured the attention of bar crowds, literary lovers, English majors, and readers everywhere with its clever commentary on history’s most beloved books.

This much anticipated 10th anniversary expanded edition features an updated introduction, refined drink recipes, and more than 70 delicious drinks and bar snacks, of which 15 recipes and 7 illustrations are exclusive to this revised edition.

. . . . . . . . . . .

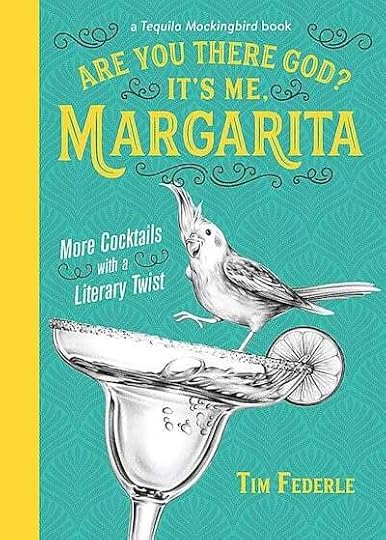

Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margarita

Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margarita: More Cocktails with a Literary Twist by Tim Federle (Running Press, 2018). From the publisher: Literature, puns, and alcohol collide in this clever follow-up to Tequila Mockingbird, the world’s bestselling cocktail recipes book.

Tim Federle’s Tequila Mockingbird has become one of the world’s bestselling cocktail books and resonated with bartenders and book clubs everywhere.

Now in this much anticipated follow-up, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margarita, Federle has shaken up 49 all-new, all-delicious drink recipes paired with his trademark puns and clever commentary on more of history’s most beloved books, as well as bar bites, drinking games, and whimsical illustrations throughout.

. . . . . . . . . . .

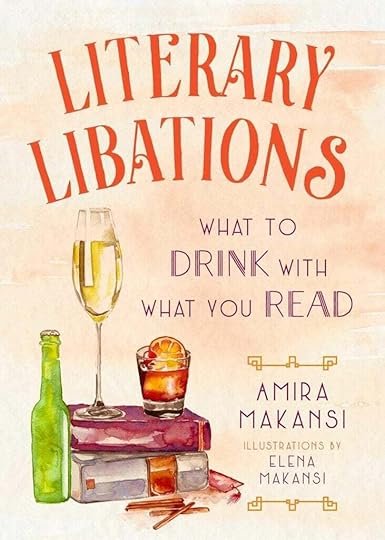

Literary Libations

Literary Libations: What to Drink with What You Read by Amira Makansi (Skyhorse, 2018). From the publisher: Want to know what to drink with all your favorite books?

A bubbly, boozy French 75 with The Great Gatsby. A luscious Chocolatini with Bridget Jones’s Diary. Old vine California Zinfandel with The Grapes of Wrath. Lager (by the pitcher, from your local dive) with Fight Club.

Refreshing citrus shandy with Their Eyes Were Watching God. And don’t you dare open Dracula without a Bloody Mary near at hand!

Now book lovers everywhere can raise the perfect toast to Shakespeare, Austen, Kerouac, Woolf, and more. With drink pairing recommendations for nearly 200 classic and contemporary works of fiction, including non-alcoholic pairings for kids and young adult books, Literary Libations is a necessary addition to bookshelves and bar tops everywhere.

. . . . . . . . . . .

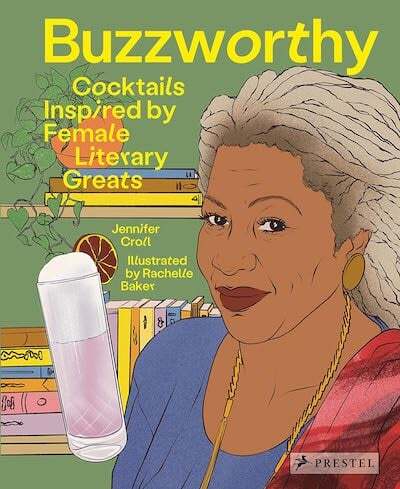

Buzzworthy

Buzzworthy: Cocktails Inspired by Female Literary Greats by Jennifer Croll (Prestel, 2023): From the publisher: The author of Free the Tipple is back with another collection of delectable cocktails—this time a literary mix inspired by the world’s most iconic women writers. The fifty recipes in this volume are as unconventional, imaginative, and refreshing as the authors that inspired them.

Each double-page spread includes an illustration of one important woman writer along with fascinating background about her œuvre, personality, and points of literary distinction.

And, of course, each profile is paired with a delicious recipe for a fitting cocktail. Pulling from every category—literary and genre fiction, poetry, graphic novels, essays and nonfiction— this book offers some surprising twists as well as old favorites. Perfect for literary-themed parties as well as intimate gatherings, this book itself is an intoxicating, lip-loosening brew made of equal parts sophistication and fun.

. . . . . . . . . . .

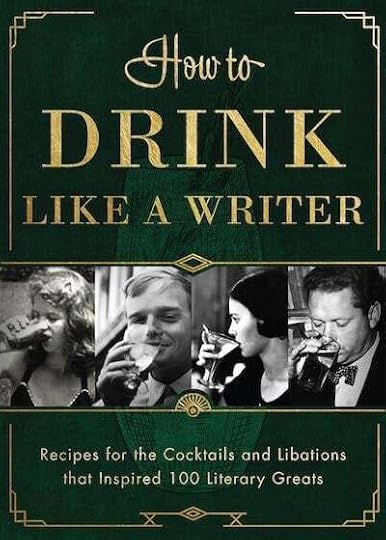

How to Drink Like a Writer

How to Drink Like a Writer: Recipes for the Cocktails and Libations that Inspired 100 Literary Greats by Apollo Publishers (2020). From the publisher: Pairing 100 famous authors, poets, and playwrights from the Victorian age to today with recipes for their iconic drinks of choice, How to Drink Like a Writer is the perfect guide to getting lit(erary) for madcap mixologists, book club bartenders, and cocktail enthusiasts.

Have you dreamed of sharing martinis with Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton after poetry class? Maybe a mojito—a real one, like they serve at La Bodeguita del Medio in Havana—is all you need to summon the mesmerizing power of Hemingway’s prose. Writer’s block? Summon the brilliant musings of Truman Capote with a screwdriver—or, “my orange drink,” as he called it.

With 100 spirited drink recipes and special sections dedicated to writerly haunts like the Algonquin of the New Yorker set and Kerouac’s Vesuvio Café, pointers for hosting your own literary salon, and author-approved hangover cures, all accompanied by original illustrations of ingredients, finished cocktails, classic drinks, and favorite food pairings, How to Drink Like a Writer is sure to inspire, invoke, and inebriate.

The post 7 Literary Cocktail Books: Boozy, Punny Tributes to Famous Authors appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 1, 2023

Nina Bawden, Author of Carrie’s War

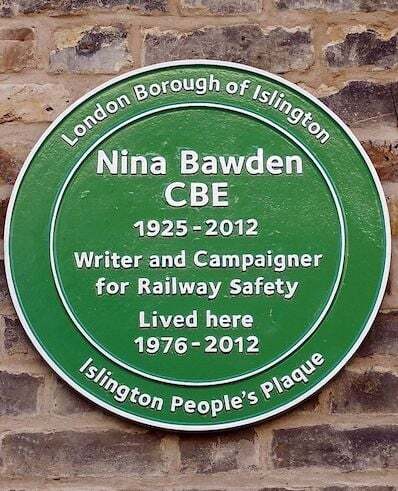

Nina Bawden (January 19, 1925 – August 22, 2012) was a British novelist, children’s book writer, and campaigner. Best known for the children’s novel Carrie’s War, she published twenty-three adult novels and twenty children’s books over some fifty years.

In all of her writing, she made “use of all of my life, all memory, wasting nothing,” and claimed that if her books were read in sequence, they formed a “coded autobiography.”

She was also a fierce campaigner for rail safety after being involved in the Potters Bar train crash of 2002.

Early years in Essex and Oxford

Born Nina Mary Mabey in Goodmayes, Essex, an area near the London Docks in Milford which she later described as “featureless and ugly.” Her father Charles was a merchant navy engineer and was mostly absent. It was a second marriage for him, but the first for her mother, who was a teacher.

She won a scholarship to Ilford County High School, but at age fourteen, when World War II broke out, she was evacuated first to Suffolk and then to South Wales. She only returned to London in 1943.

Despite this interruption to her education, Nina achieved a place at Somerville College, Oxford, to study philosophy, politics, and economics. There, she was a contemporary of Margaret Roberts — later Margaret Thatcher — and, with characteristic audacity and determination, attempted to persuade Margaret to join the Labour Party instead of the Conservatives. One can’t help but wonder how history might have been different had she succeeded!

Two marriages and family life

In 1946, Nina married Henry Bawden, an ex-serviceman and classical scholar many years her senior. His mother had taken her own life before their marriage; the couple managed to buy their first house in London with the money that she left. They had two sons, Nicholas (known as Niki) in 1948, and Robert in 1951.

When she met ex-naval officer Austen Kark, he too was married and had two young daughters. They fell in love after meeting on a bus in 1953, and both swiftly got divorced before marrying in 1954.

The couple had a daughter, Perdita, in 1957, and enjoyed family life in Weybridge, Surrey, where Nina served as a local magistrate as well as writing.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Writing for adults and childrenIt was while her children were young that Nina, who had initially wanted to become a foreign correspondent, started writing novels.

Her first book for adults, a crime novel called Who Calls the Tune, was published in 1956 by George Hardinge at Collins, and he continued to publish her adult novels (through his moves to Longman and then Macmillan) until 1987.

Finding a publisher for her children’s books proved more challenging, and it took several tries before her first, The Secret Passage (1963), was picked up by Livia Gollancz.

It was considered unusual at the time because the young protagonists didn’t have a traditional family, nor were the characters “good” as most children in books were: their mother was dead, their father was absent, their aunt was nasty, and they could be jealous, selfish, and bad-tempered.

In the early years of writing, Nina wrote one adult book and one children’s book each year. Later, she began to alternate them.

She became known for her refusal to shy away from the darker undercurrents of life, even in her children’s novels. In In My Own Time: Almost an Autobiography (1994) she wrote that “darkness and chaos threaten us all, lying in wait at the bottom of the garden, lurking outside the safe, lighted room,” and she always acknowledged that belief in her work.

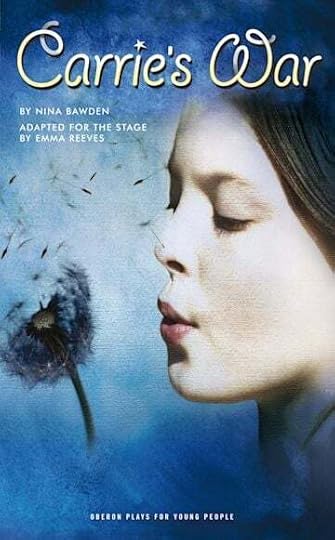

Her children’s novel Carrie’s War (1973) was arguably the best example of her beliefs. It’s the gritty story of two children evacuated from London to Wales during World War II, based on Nina’s real-life experiences. It won the Phoenix Award in 1995 and was adapted for television in 1974 and 2004.

Her adult novels, meanwhile, often centered on breakdowns -—of relationships, families, communication, health — and on the turbulence that may lie beneath the surface of a British middle-class family. Many also had a political undertone. Nina was a committed Labour supporter, and throughout her life challenged conservative social and cultural norms.

While she was sometimes criticized for her plotting — with some critics complaining there was too much and others that there was too little — it was generally agreed that she was a master of description, even in her children’s books. The Peppermint Pig (1975), contains the following wonderful line:

“Poll was the naughtiest one of the family, and the dreadful thing happened on one of her naughty days: a dark day of thick, mustardy fog that had specks of grit in it she could taste on her tongue.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Family life and a tragedyBy the late 1960s, Kark was rising up the ranks at the BBC (he would eventually become head of the BBC World Service) and the family moved to Islington in 1979.

The family traveled a lot, and Nina often set her novels in the countries they visited: for example, Kenya (Under the Skin, 1964), Morocco (A Woman of My Age, 1967), and Turkey (George Beneath a Paper Moon, 1974). They also enjoyed socializing and parties both in London and at their second home in Nafplio, Greece.

In his teens, her son Niki became addicted to drugs. He was also diagnosed with schizophrenia and, after a period of imprisonment for drug offenses, was incarcerated in a mental hospital. The story ended in tragedy when Niki drowned himself in the Thames in 1981 at the age of thirty-three. The family didn’t find out for certain that it was he who had died until months later.

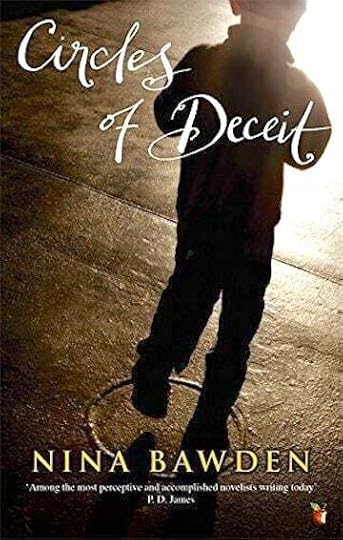

Later, Nina would write in her memoir, “If my son wanted to leave then I should have left too. This is what it feels like when pieces of you fall away.” Her novel, Circle of Deceit (1987), was based largely on Niki’s story.

“When bad things happen,” Nina said, “you absorb them into yourself and make use of them in novels.” The novel featured a young man who was schizophrenic, although Nina couldn’t bring herself to kill the character as Niki had done to himself in real life.

Circle of Deceit was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and was successfully adapted for television. It was not the only novel to be inspired by Niki: her later novel Birds on the Trees (1970) was about a young man who becomes addicted to drugs and has a subsequent breakdown, and the effect this has on his family. In 2010 it was shortlisted for the Lost Man Booker Prize.

The Potters Bar train crash

On 10th May 2002, Nina and her husband boarded a high-speed train from London to Cambridge to attend a party. It derailed at almost one hundred miles per hour at Potters Bar in Hertfordshire, killing seven people, including Kark, who died instantly, and injuring several more. It was the worst train disaster in British history.

Nina, then age seventy-seven, was cut from the wreckage with a broken ankle, arm, leg, shoulder, collarbone, and several ribs. Family and friends feared she might not recover. After multiple surgeries, she defied the doctors’ expectations and was able to stand unaided. She taught herself to walk again, and eventually returned home to Islington.

Although she suffered from PTSD after the crash, Nina said, “I refuse to feel badly done by in life … I could have been in a concentration camp or been born a paraplegic. My family have been so loving and supportive it is my duty to recover and get on with things for them.”

She campaigned tirelessly for a full investigation into the accident, and when the government refused to allow a public inquiry, she was so incensed that she cut up her Labour Party membership card. When survivors of the crash were refused legal aid, she stepped in and took the rail companies to court personally. In 2011 the company that operated that section of the rail track was fined £3 million for safety violations.

The disaster was commemorated in The Permanent Way (2003), a play by David Hare which featured a character based on Nina Bowden.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Later yearsNina Bawden continued to write through her recovery and subsequent campaigning, and in 2005 published a memoir, Dear Austen. It was structured as a series of letters addressed to her late husband, and was extraordinary in its courage, anger, and vulnerability. In one letter, Nina wrote,

“When we bought tickets for this railway journey we had expected a safe arrival, not an earthquake smashing lives into pieces … I dislike the word ‘victim.’ I dislike being told that I ‘lost’ my husband — as if I had idly abandoned you by the side of the railway track like a pair of unwanted old shoes. You were killed. I didn’t lose you. And I am not a victim, I am an angry survivor.”

Nina was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 1987 and the Lost Man Booker Prize in 2010. In the same year, she was awarded a PEN Award for Lifetime Services to Literature.

The crash had taken its toll, and in her last years, she was largely dependent on her daughter Perdita for helping her out. Nina never recovered after Perdita died from an aggressive form of cancer in 2012, and died just a few months after her daughter did that same year.

A plaque commemorating Nina Bawden’s life as a writer and campaigner was unveiled at her home in Islington in September 2015. Many of her books have been reissued by Virago Modern Classics.

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Nina BawdenFollowing is but a small sampling of Nina Bawden’s major works. Here is a complete bibliography, though it doesn’t distinguish between her works for adults and children, nor between fiction and nonfiction.

Books for children

Carrie’s War (1973)Henry (1988)Keeping Henry (1988)The Peppermint Pig (1975)The Secret Passage (1963)The Witch’s Daughter (1966)Selected novels for adults

Who Calls the Tune (1956)Devil by the Sea (1957)Under the Skin (1964)A Woman of My Age (1967)The Birds on the Trees (1970)George Beneath a Paper Moon (1974)Afternoon of a Good Woman (1976)Circle of Deceit (1987)Biography and letters

In My Own Time: Almost an Autobiography (1994)Dear Austen (2005)Further reading

Obituary in The Guardian Reader discussions on Goodreads The Booker PrizeThe post Nina Bawden, Author of Carrie’s War appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 27, 2023

Agatha Whiskey by Colleen Mullaney (+ a Q & A with the author)

From the author of Gin Austen, Colleen Mullaney’s new book, Agatha Whiskey, is a delicious and mysterious collection of cocktails and mocktails.

The perfect gift for mystery fans, Agatha Christie fans, amateur mixologists, and anyone who wants a fun drink to sip on all year round.

A celebration of Christie’s timeless murder mysteries, killer short stories, suspenseful plays, and unmatched characters—with cocktails that are so tantalizingly delicious, it must be a crime.

Dame Agatha Christie is arguably the world’s most famous mystery writer, with over a billion copies of her books sold.

Agatha Whiskey (Skyhorse, September 2023) takes clues from Agatha’s most pivotal works of fiction and honors her most popular detectives. Featured super-sleuths are Dame Agatha herself, the one and only Maiden of Murder, detective Hercule Poirot, whose sleuthing is only outdone by his magnificent mustache, and Miss Jane Marple, the sweet old maid with an uncanny knack for crime solving.

There’s a plot twist for everyone with fifty thrilling drinks such as a Pocket Full of Rosé, Orient Espresso Martini, and Daiquiri on the Nile. There are also detective drinking games to get your party on the right track, and mocktails for those who choose to forgo an endless night.

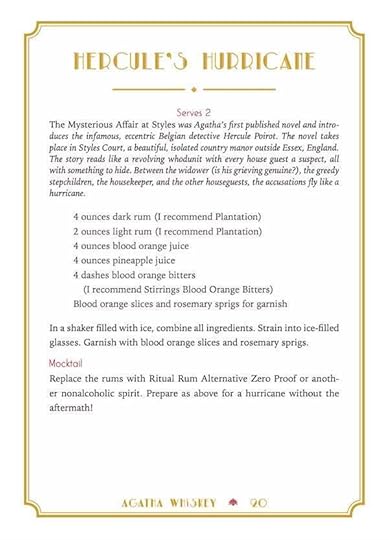

Just like Agatha herself, Agatha Whiskey is here to entertain, inspire, and add some drama of the right sort to your life. Make sure to read to the very end for a cocktail from the book, “Hercule’s Hurricane.”

. . . . . . . . .

Agatha Whiskey is available on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

About the Author: Colleen Mullaney is a well-known lifestyle expert and bestselling author of how-to books covering a range of topics on entertaining, cocktails, floral design, and weddings. Her most recent, Gin Austen, won the International Gourmand Drink Culture Award. Mullaney is a former magazine editor-in-chief and has been a regular contributor to Huffington Post, Today.com, New York Daily News, Woman’s Day, and many more. She lives in Westchester county, New York.

Q & A with Colleen Mullaney, author of Agatha Whiskey

Colleen, I shared a cocktail from your previous book, Gin Austen, shortly after it was published. Given the relative staidness of Jane Austen’s situations and characters the 20th-century settings of the Agatha Christie mysteries, how was the creative process behind Agatha Whiskey different?

I wrote Gin Austen to celebrate Jane’s work and her tremendous legacy through entertaining and cocktails, giving lighthearted insight into her world and her characters. She definitely was a woman ahead of her time, and her popularity remains so strong today.

So, when I began researching a second book by a woman author, I thought who better than Dame Agatha, the bestselling novelist of all time! But the question was, where do I even begin to choose titles and works to feature?

Her canon of work is so vast, and my goal was to write it so readers would discover a bit about her personal life and work — and to be entertained with cocktails. Hopefully, readers will come away curious.

As I decided how to approach the book, I broke it into different chapters to reflect the topics of her writing: Drinking Detectives, Murders & Mysteries in Faraway Places, Garden Parties, Stolen Identities & Unscrupulous Vicars, and Family Dynamics & Deadly Disturbances to name a few.

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Agatha Christie

. . . . . . . . .

Dame Agatha was something of an expert on poisons. Kemper Dawson (mystery author and host of the All About Agatha podcast) in the Forward to your book points out that “The Queen of Crime used poisons more than any other means to murder her characters.” Of course, your cocktails and mocktails aren’t poison-laced, but did these factors help inspire them?

Oh yes! I loved the fact that during the First World War, Agatha worked as an assistant dispenser, gaining knowledge of poisons. Ao it was a natural fit that poisons inspired many of the books I featured and the cocktails I mixed: Sparkling Cyanide (Sparkling Cyanide), Artist in Residence (Five Little Pigs), Seaside Sangria (Sleeping Murder).

Others were a play on words like Orient Espresso Martini (Murder on the Orient Express) and Daiquiri on the Nile (Death on the Nile).

. . . . . . . . . .

You may also like:

A Jane Austen-Inspired Cocktail

from Gin Austen by Colleen Mullaney

. . . . . . . . . .

Speaking of mocktails, can you talk about why you provided an alcohol-free alternative to each of your recipes?

I wanted to celebrate the fact that Agatha wasn’t a drinker, so I included a mocktail with each cocktail recipe. I featured a mocktail that I titled “Mocktails and Murder,” which I thought she would have enjoyed, sitting and looking out at her gardens. The cocktail is very garden-centric with Seedlip Grove 42, an English brand specializing in non-alcoholic spirits, rhubarb syrup, and bitters.It’s quite refreshing and tasty!

Also, I thought it was important to include mocktails for the growing number of people that are abstaining for personal reasons or simply to pursue a healthier lifestyle.

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Hercule’s Hurricane” (recipe below) Photo: Jack Deutsch

. . . . . . . . . . .

I recently read The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Dame Agatha’s first published novel, and the one that introduced her iconic detective, Hercule Poirot. This novel inspired your first two cocktail recipes, including the one I’ll be sharing here (Hercule’s Hurricane). Are you Team Poirot or Team Marple? And, would you like to give a shout-out to any of her lesser-known detectives (all of whom are listed in your book)?

Yes, the question I find most torturous when talking about the book! I adore Poirot, and his quirkiness, mannerisms, and profound way of being. That said, I root for his happiness.

But for me it’s Miss Jane Marple. She’s entirely underestimated, up for anything, and has no plans for slowing down. I love her community of St. Mary’s Mead, how she lives a virtuous life training girls from the nearby orphanage to work as housekeepers so they can go on and earn a living.

She has a nephew, Raymond West, who treats her to vacations and hotel stays. Then there’s the fact she makes her own Cherry Brandy from her grandmother’s recipe, offering it to anyone who’s had a bit of a fright. I include a recipe titled Miss Marple’s Cherry Blossom, with, of course, cherry brandy!

Scattered throughout your book are quotes from Agatha Christie’s novels. Can you share a favorite, and why it appeals to you?

Oh, it has to be this from Murder at the Vicarage:

“What are you doing this afternoon, Griselda?”

“My duty as the Vicaress. Tea and scandal at four-thirty.”

I just love the levity and humor of the honest answer, as you know in the book they do sit around and gossip about how one of the characters should meet his demise. Little did they know he was quite dead already!

For me, as a writer of entertaining books and lifestyle expert, mixing cocktails and inviting friends over to join in is what it’s all about — sharing and being hospitable is pure joy.

I would suggest grabbing a copy of Agatha Whiskey, inviting friends over, mixing up some cocktails and letting the fun begin! Pick your poison!!

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop.org and Amazon affiliate links. If a product is purchased after linking through, Literary Ladies receives a modest commission, which helps us to keep growing!

The post Agatha Whiskey by Colleen Mullaney (+ a Q & A with the author) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 17, 2023

“Sweat” – a 1926 short story by Zora Neale Hurston (full text)

Originally published in 1926, Zora Neale Hurston’s short story, “Sweat,” is nuanced and eloquently compact. Hurston maximizes each word, object, character, and plot point to create an impassioned and enlightening narrative.

Within this small space, Hurston addresses a number of themes, such as the trials of femininity, which she explores with compelling and efficient symbolism.

In her introduction to the 1997 anthology entirely devoted to the story (“Sweat” by Zora Neale Hurston), editor Cheryl A. Wall wrote:

“The many levels on which ‘Sweat’ can be read make it one of Zora Neale Hurston’s most enduring works. It was published in 1926, early in Hurston’s career, indeed, long before she had dedicated herself to the profession of writing.”

Robert Hemenway, a Hurston biographer, observes in Zora Neale Hurston: A Literary Biography (1977):

“‘Sweat’ is a story remarkably complex at both narrative and symbolic levels, yet so subtly done that one at first senses only the fairly simple narrative line. The account of a Christian woman learning how to hate in spite of herself, a story of marital cruelty and the oppression of marital relationships, an allegory of good and evil, it concentrates on folk character rather than on folk environment.”

Read the rest of Jason Horn’s analysis of this short story: “Sweat” by Zora Neale Hurston: An Ecofeminist Master Class in Dialect and Symbolism.

“Sweat” was originally published in Fire!! Devoted to the Younger Negro Artists (1926), and is now in the public domain.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Zora Neale Hurston

. . . . . . . . . . .

It was eleven o’clock of a Spring night in Florida. It was Sunday. Any other night, Delia Jones would have been in bed for two hours by this time. But she was a wash-woman, and Monday morning meant a great deal to her.

So she collected the soiled clothes on Saturday when she returned the clean things. Sunday night after church, she sorted them and put the white things to soak. It saved her almost a half day’s start. A great hamper in the bedroom held the clothes that she brought home. It was so much neater than a number of bundles lying around.

She squatted in the kitchen floor beside the great pile of clothes, sorting them into small heaps according to color, and humming a song in a mournful key, but wondering through it all where Sykes, her husband, had gone with her horse and buckboard.

Just then something long, round, limp and black fell upon her shoulders and slithered to the floor beside her. A great terror took hold of her. It softened her knees and dried her mouth so that it was a full minute before she could cry out or move. Then she saw that it was the big bull whip her husband liked to carry when he drove.

She lifted her eyes to the door and saw him standing there bent over with laughter at her fright. She screamed at him.

“Sykes, what you throw dat whip on me like dat? You know it would skeer me–looks just like a snake, an’ you knows how skeered Ah is of snakes.”

“Course Ah knowed it! That’s how come Ah done it.” He slapped his leg with his hand and almost rolled on the ground in his mirth. “If you such a big fool dat you got to have a fit over a earth worm or a string, Ah don’t keer how bad Ah skeer you.”

“You aint got no business doing it. Gawd knows it’s a sin. Some day Ah’m goin’ tuh drop dead from some of yo’ foolishness. ‘Nother thing, where you been wid mah rig? Ah feeds dat pony. He aint fuh you to be drivin’ wid no bull whip.”

“You sho is one aggravatin’ n—— woman!” he declared and stepped into the room. She resumed her work and did not answer him at once. “Ah done tole you time and again to keep them white folks’ clothes outa dis house.”

He picked up the whip and glared down at her. Delia went on with her work. She went out into the yard and returned with a galvanized tub and set it on the washbench. She saw that Sykes had kicked all of the clothes together again, and now stood in her way truculently, his whole manner hoping, praying, for an argument. But she walked calmly around him and commenced to re-sort the things.

“Next time, Ah’m gointer kick ’em outdoors,” he threatened as he struck a match along the leg of his corduroy breeches.

Delia never looked up from her work, and her thin, stooped shoulders sagged further.

“Ah aint for no fuss t’night Sykes. Ah just come from taking sacrament at the church house.”

He snorted scornfully. “Yeah, you just come from de church house on a Sunday night, but heah you is gone to work on them clothes. You ain’t nothing but a hypocrite. One of them amen-corner Christians–sing, whoop, and shout, then come home and wash white folks clothes on the Sabbath.”

He stepped roughly upon the whitest pile of things, kicking them helter-skelter as he crossed the room. His wife gave a little scream of dismay, and quickly gathered them together again.

“Sykes, you quit grindin’ dirt into these clothes! How can Ah git through by Sat’day if Ah don’t start on Sunday?”

“Ah don’t keer if you never git through. Anyhow, Ah done promised Gawd and a couple of other men, Ah aint gointer have it in mah house. Don’t gimme no lip neither, else Ah’ll throw ’em out and put mah fist up side yo’ head to boot.”

Delia’s habitual meekness seemed to slip from her shoulders like a blown scarf. She was on her feet; her poor little body, her bare knuckly hands bravely defying the strapping hulk before her.

“Looka heah, Sykes, you done gone too fur. Ah been married to you fur fifteen years, and Ah been takin’ in washin’ for fifteen years. Sweat, sweat, sweat! Work and sweat, cry and sweat, pray and sweat!”

“What’s that got to do with me?” he asked brutally.

“What’s it got to do with you, Sykes? Mah tub of suds is filled yo’ belly with vittles more times than yo’ hands is filled it. Mah sweat is done paid for this house and Ah reckon Ah kin keep on sweatin’ in it.”

She seized the iron skillet from the stove and struck a defensive pose, which act surprised him greatly, coming from her. It cowed him and he did not strike her as he usually did.

“Naw you won’t,” she panted, “that ole snaggle-toothed black woman you runnin’ with aint comin’ heah to pile up on mah sweat and blood. You aint paid for nothin’ on this place, and Ah’m gointer stay right heah till Ah’m toted out foot foremost.”

“Well, you better quit gittin’ me riled up, else they’ll be totin’ you out sooner than you expect. Ah’m so tired of you Ah don’t know whut to do. Gawd! how Ah hates skinny wimmen!”

A little awed by this new Delia, he sidled out of the door and slammed the back gate after him. He did not say where he had gone, but she knew too well. She knew very well that he would not return until nearly daybreak also. Her work over, she went on to bed but not to sleep at once. Things had come to a pretty pass!

She lay awake, gazing upon the debris that cluttered their matrimonial trail. Not an image left standing along the way. Anything like flowers had long ago been drowned in the salty stream that had been pressed from her heart. Her tears, her sweat, her blood.

She had brought love to the union and he had brought a longing after the flesh. Two months after the wedding, he had given her the first brutal beating. She had the memory of his numerous trips to Orlando with all of his wages when he had returned to her penniless, even before the first year had passed.

She was young and soft then, but now she thought of her knotty, muscled limbs, her harsh knuckly hands, and drew herself up into an unhappy little ball in the middle of the big feather bed. Too late now to hope for love, even if it were not Bertha it would be someone else.

This case differed from the others only in that she was bolder than the others. Too late for everything except her little home. She had built it for her old days, and planted one by one the trees and flowers there. It was lovely to her, lovely.

Somehow, before sleep came, she found herself saying aloud: “Oh well, whatever goes over the Devil’s back, is got to come under his belly. Sometime or ruther, Sykes, like everybody else, is gointer reap his sowing.”

After that she was able to build a spiritual earthworks against her husband. His shells could no longer reach her. Amen. She went to sleep and slept until he announced his presence in bed by kicking her feet and rudely snatching the covers away.

“Gimme some kivah heah, an’ git yo’ damn foots over on yo’ own side! Ah oughter mash you in yo’ mouf fuh drawing dat skillet on me.”

Delia went clear to the rail without answering him. A triumphant indifference to all that he was or did.

. . . . . . . . . .

The week was as full of work for Delia as all other weeks, and Saturday found her behind her little pony, collecting and delivering clothes.

It was a hot, hot day near the end of July. The village men on Joe Clarke’s porch even chewed cane listlessly. They did not hurl the cane-knots as usual. They let them dribble over the edge of the porch. Even conversation had collapsed under the heat.

“Heah come Delia Jones,” Jim Merchant said, as the shaggy pony came ’round the bend of the road toward them. The rusty buckboard was heaped with baskets of crisp, clean laundry.

“Yep,” Joe Lindsay agreed. “Hot or col’, rain or shine, jes ez reg’lar ez de weeks roll roun’ Delia carries ’em an’ fetches ’em on Sat’day.”

“She better if she wanter eat,” said Moss. “Syke Jones aint wuth de shot an’ powder hit would tek tuh kill ’em. Not to huh he aint. ”

“He sho’ aint,” Walter Thomas chimed in. “It’s too bad, too, cause she wuz a right pritty lil trick when he got huh. Ah’d uh mah’ied huh mahseff if he hadnter beat me to it.”

Delia nodded briefly at the men as she drove past.

“Too much knockin’ will ruin any ‘oman. He done beat huh ‘nough tuh kill three women, let ‘lone change they looks,” said Elijah Moseley. “How Syke kin stommuck dat big black greasy Mogul he’s layin’ roun wid, gits me. Ah swear dat eight-rock couldn’t kiss a sardine can Ah done throwed out de back do’ ‘way las’ yeah.”

“Aw, she’s fat, thass how come. He’s allus been crazy ’bout fat women,” put in Merchant. “He’d a’ been tied up wid one long time ago if he could a’ found one tuh have him. Did Ah tell yuh ’bout him come sidlin’ roun’ mah wife–bringin’ her a basket uh pecans outa his yard fuh a present? Yessir, mah wife! She tol’ him tuh take ’em right straight back home, cause Delia works so hard ovah dat washtub she reckon everything on de place taste lak sweat an’ soapsuds. Ah jus’ wisht Ah’d a’ caught ‘im ‘dere! Ah’d a’ made his hips ketch on fiah down dat shell road.”

“Ah know he done it, too. Ah sees ‘im grinnin’ at every ‘oman dat passes,” Walter Thomas said.

“But even so, he useter eat some mighty big hunks uh humble pie tuh git dat lil ‘oman he got. She wuz ez pritty ez a speckled pup! Dat wuz fifteen yeahs ago. He useter be so skeered uh losin’ huh, she could make him do some parts of a husband’s duty. Dey never wuz de same in de mind.”

“There oughter be a law about him,” said Lindsay. “He aint fit tuh carry guts tuh a bear.”

Clarke spoke for the first time. “Taint no law on earth dat kin make a man be decent if it aint in ‘im. There’s plenty men dat takes a wife lak dey do a joint uh sugar-cane. It’s round, juicy an’ sweet when dey gits it. But dey squeeze an’ grind, squeeze an’ grind an’ wring tell dey wring every drop uh pleasure dat’s in ’em out. When dey’s satisfied dat dey is wrung dry, dey treats ’em jes lak dey do a cane-chew. Dey throws em away. Dey knows whut dey is doin’ while dey is at it, an’ hates theirselves fuh it but they keeps on hangin’ after huh tell she’s empty. Den dey hates huh fuh bein’ a cane-chew an’ in de way.”

“We oughter take Syke an’ dat stray ‘oman uh his’n down in Lake Howell swamp an’ lay on de rawhide till they cain’t say Lawd a’ mussy.’ He allus wuz uh ovahbearin’ ni – – ah, but since dat white ‘oman from up north done teached ‘im how to run a automobile, he done got too biggety to live–an’ we oughter kill ‘im,” Old Man Anderson advised.

A grunt of approval went around the porch. But the heat was melting their civic virtue, and Elijah Moseley began to bait Joe Clarke.

“Come on, Joe, git a melon outa dere an’ slice it up for yo’ customers. We’se all sufferin’ wid de heat. De bear’s done got me!”

“Thass right, Joe, a watermelon is jes’ whut Ah needs tuh cure de eppizudicks,” Walter Thomas joined forces with Moseley. “Come on dere, Joe. We all is steady customers an’ you aint set us up in a long time. Ah chooses dat long, bowlegged Floridy favorite.”

“A god, an’ be dough. You all gimme twenty cents and slice way,” Clarke retorted. “Ah needs a col’ slice m’self. Heah, everybody chip in. Ah’ll lend y’ll mah meat knife.”

The money was quickly subscribed and the huge melon brought forth. At that moment, Sykes and Bertha arrived. A determined silence fell on the porch and the melon was put away again.

Merchant snapped down the blade of his jackknife and moved toward the store door.

“Come on in, Joe, an’ gimme a slab uh sow belly an’ uh pound uh coffee–almost fuhgot ’twas

Sat’day. Got to git on home.” Most of the men left also.