Nava Atlas's Blog, page 19

May 22, 2023

The Enchanted April by Elizabeth von Arnim (1922)

The Enchanted April, the 1922 novel by the elusive Elizabeth Von Arnim, has stood the test of time as a journey of friendship and self-discovery.

Certain stories possess an irresistible charm that beckons readers to embark on captivating journeys of the heart and mind. Elizabeth von Arnim’s 1922 novel, The Enchanted April is one such masterpiece, fueling the imagination and evoking a sense of wonder.

The Enchanted April is a lighthearted (yet not lightweight) tale of freedom to live an authentic life, and the transformative power of female friendship. This literary gem continues to engage readers even after a century, effortlessly weaving together picturesque landscapes, relatable characters, and heartfelt emotions.

Elizabeth von Arnim’s skillful portrayal of authentic characters is a testament to the enduring appeal of this novel. Through their joys, sorrows, and vulnerabilities, we find glimpses of our own humanity reflected in their journeys.

Lotty Wilkins, Rose Arbuthnot, Lady Caroline Dester, and Mrs. Fisher endear themselves to readers as we accompany them on their quests for the rediscovery of their true selves. Within the embrace of the Italian paradise, these four women embark on an exploration of their desires, dreams, and unfulfilled passions.

Beyond its engaging characters, The Enchanted April captivates with its vivid descriptions of the Italian Riviera’s sun-drenched landscapes. Elizabeth von Arnim’s prose transports us to idyllic gardens where vibrant flowers bloom, and the gentle Mediterranean breeze whispers secrets of serenity and renewal.

With each turn of the page, we are enveloped in a world that appeals to our senses, inviting us to breathe in the fragrant air and bask in the golden sunlight.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Plot SummarySet against the backdrop of post-World War I England, the novel follows the lives of four seemingly dissimilar women whose paths happen to intertwine. Lotty Wilkins, Rose Arbuthnot, Lady Caroline Dester, and Mrs. Fisher respond to an advertisement inviting them to rent a medieval castle on the Italian Riviera for the month of April.

Eager to escape their unfulfilling lives, the four women embark on a journey that promises not only sunshine and beauty but also a chance for self-reflection and transformation.

Upon arriving at the idyllic San Salvatore, the magic of the place begins to work its charm on the ladies. The story delves into the women’s inner lives and desires, revealing their dreams, disappointments, and hidden aspirations.

As they immerse themselves in the Italian gardens and the soothing Mediterranean breezes, the ladies gradually shed their inhibitions and allow themselves to be transformed by the power of love and nature.

Themes, characters, & critical reception

The Enchanted April explores themes of liberation, personal growth, and the rekindling of one’s passions.

Lotty Wilkins, a timid and unfulfilled housewife, discovers her voice and inner strength in the embrace of San Salvatore. Burdened by her unhappy marriage, Rose Arbuthnot rediscovers her capacity for love and joy.

Additionally, the enigmatic Lady Caroline Dester, a famous socialite, learns to embrace vulnerability and opens herself to the possibility of genuine connection. Mrs. Fisher, a widow trapped in the memories of her past, finds solace and a renewed zest for life amidst the vibrant surroundings.

Elizabeth von Arnim’s nuanced character development paints a vivid portrait of women who defy societal expectations in their unique journeys of self-discovery. She highlights the universal desire for freedom, connection, and fulfillment through their interactions and revelations.

Since its publication, The Enchanted April has captivated readers and critics alike with its whimsical prose and profound storytelling. Contemporary reviews praised Elizabeth von Arnim’s ability to transport readers to the Italian Riviera, evoking a sense of escapism and tranquility.

. . . . . . . . . .

1991 film adaptation, titled Enchanted April

. . . . . . . . . .

The enduring appeal of The Enchanted April has inspired several adaptations, further cementing its place in popular culture. The novel was adapted into a successful 1935 film directed by Harry Beaumont and subsequently remade in 1991 by Mike Newell, gaining critical acclaim.

The story also reached the Broadway stage as a musical, with Matthew Barber’s theatrical adaptation premiering in 2003, receiving Tony Award nominations and captivating audiences with its enchanting portrayal of love and transformation.

ConclusionWhat sets this literary treasure apart is its ability to strike a chord with readers across generations. Elizabeth von Arnim’s exquisite prose captures the essence of human emotions, unveiling the complexities of the human spirit with grace and authenticity.

Her storytelling continues to resonate, reminding readers of the universal yearning for personal freedom, authentic connections, and a life of joy and purpose.

. . . . . . . . .

The stage musical went on to be performed in other venues,

including Hale Center Theater Orem

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review in the Oakland Tribune, January 1923: The author of Elizabeth and her German Garden has written a humorous and satiric story of four women who rent an Italian castle.

“Elizabeth”* is to be thanked for the atmosphere and illusion she creates in The Enchanted April and she is to be congratulated warmly for Mrs. Wilkens.

It is an enchanted April this month in Italy, a story of smiles and solid enjoyment and one such as few writers could produce.

One may question the powers of reformation in Italian breezes and views and may wonder at the rapid changes the characters undergo. But one will question and wonder a long time after reading the book. The charm and the impression are that enduring.

Mrs. Wilkens is a shy and retiring woman who defers so much to her husband that she is without color and character. No one knows when she is present, no one even thinks of her. The husband, on the other hand, is the life of every party.

Then there is Rose Arbuthnot, deeply religious and becoming more and more self-centered because of the estrangement in her family. Her husband has written some memoirs of famous women who are none too particular in many ways. This grieves Rose and she won’t take any of his money except to give to charity.

Four lives are indeed changed

Another character in the cast, Lady Caroline, is so beautiful and so winning she cannot be cold and rude for her features and her voice will not betray her intent. She is selfish and she wished to be alone, to go away from everyone she knows, that she might think for once in her life.

With a Mrs. Fisher, more selfish than any, a regular tyrant in securing her rights, Rose and Lotty Wilkens rent a castle in Italy for a month.

The charm is worked on Mrs. Wilkens first. She is filled with the most glorious sensation of happiness imaginable and tries right away to spread the feeling to the rest.

The spell of the castle and of Italy works on all and four lives are changed. This is the story which in outline sounds a bit like Pollyanna, but which, because of the bright lines, flashes of humor, and keen observation is the best book that the new year has yet disclosed.

*Elizabeth von Arnim identified herself only as “Elizabeth” or “The author of Elizabeth and Her German Garden” as her nom de plume on many of her earlier books.

. . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

The Solitary Summer by Elizabeth von Arnim. . . . . . . . . .

The post The Enchanted April by Elizabeth von Arnim (1922) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 17, 2023

Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett: A Romantic Correspondence

In 1844, Elizabeth Barrett’s second major collection of poems (A Drama of Exile) was published and warmly received. The work included lines that praised fellow poet Robert Browning.

Presented here are the two letters that started the correspondence and ignited the romantic literary love story of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett (who soon became Elizabeth Barrett Browning).

After reading the poems, Robert wrote a letter of thanks to Elizabeth on January 10, 1845, with the tantalizing line, “I love your verses with all my heart … and I love you, too.”

Their correspondence ensued until they met for the first time in the summer of 1845. Over the next several months, they became ever closer. Elizabeth remarked that she and Robert were “growing to be the truest of friends.”

Their courtship went on for twenty months, during which time they exchanged five hundred seventy-five letters, many of which are collected in The Letters of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett, 1845 – 1846, and published much later (1900) by Smith, Elder & Co. in London.

A secret wedding and escape to ItalyOn September 12, 1846, Elizabeth and Robert were secretly married at Marylebone Church (her father didn’t approve). Not long after, the couple moved to Pisa, Italy to begin their life together.

Eventually learning of Elizabeth’s marriage, her father disowned her, refusing to see her or open letters she sent to him. Fortunately, after some time had passed, most of Elizabeth’s family accepted her marriage to Robert.

The two were inspired by their surroundings in Italy, and now, as Elizabeth Barrett Browning, she wrote a significant amount of poetry while living there.

Her most famous work, Sonnets from the Portuguese, was a collection of love poems that she wrote in the first few years of her marriage to Robert. The sonnet that begins with her most famous line, “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways,” is part of this collection.

To make these letters more readable, especially on devices, long paragraphs have been broken up, but otherwise, they remain intact. The volume in its entirety, if you’d like to read these very literary love letters, is found at The Letters of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett, 1845 – 1846.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about this romantic pair:

The Literary Love Story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning

. . . . . . . . . .

From: Robert Browning

New Cross, Hatcham, Surrey

January 10, 1845

I love your verses with all my heart, dear Miss Barrett — and this is no off-hand complimentary letter that I shall write,—whatever else, no prompt matter-of-course recognition of your genius, and there a graceful and natural end of the thing.

Since the day last week when I first read your poems, I quite laugh to remember how I have been turning and turning again in my mind what I should be able to tell you of their effect upon me, for in the first flush of delight I thought I would this once get out of my habit of purely passive enjoyment, when I do really enjoy, and thoroughly justify my admiration — perhaps even, as a loyal fellow-craftsman should, try and find fault and do you some little good to be proud of hereafter!

— But nothing comes of it all — so into me has it gone, and part of me has it become, this great living poetry of yours, not a flower of which but took root and grew —

Oh, how different that is from lying to be dried and pressed flat, and prized highly, and put in a book with a proper account at top and bottom, and shut up and put away … and the book called a ‘Flora,’ besides!

After all, I need not give up the thought of doing that, too, in time; because even now, talking with whoever is worthy, I can give a reason for my faith in one and another excellence, the fresh strange music, the affluent language, the exquisite pathos and true new brave thought; but in this addressing myself to you—your own self, and for the first time, my feeling rises altogether.

I do, as I say, love these books with all my heart — and I love you too. Do you know I was once not very far from seeing — really seeing you?

Mr. Kenyon said to me one morning ‘Would you like to see Miss Barrett?’ then he went to announce me — then he returned … you were too unwell, and now it is years ago, and I feel as at some untoward passage in my travels, as if I had been close, so close, to some world’s-wonder in chapel or crypt, only a screen to push and I might have entered, but there was some slight, so it now seems, slight and just sufficient bar to admission, and the half-opened door shut, and I went home my thousands of miles, and the sight was never to be?

Well, these Poems were to be, and this true thankful joy and pride with which I feel myself,

Yours ever faithfully,

Robert Browning

. . . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Barrett’s first response to Robert BrowningFrom: Miss Barrett

50 Wimpole Street

January 11, 1845

I thank you, dear Mr. Browning, from the bottom of my heart. You meant to give me pleasure by your letter—and even if the object had not been answered, I ought still to thank you. But it is thoroughly answered.

Such a letter from such a hand! Sympathy is dear—very dear to me: but the sympathy of a poet, and of such a poet, is the quintessence of sympathy to me! Will you take back my gratitude for it?—agreeing, too, that of all the commerce done in the world, from Tyre to Carthage, the exchange of sympathy for gratitude is the most princely thing!

For the rest you draw me on with your kindness. It is difficult to get rid of people when you once have given them too much pleasure—that is a fact, and we will not stop for the moral of it.

What I was going to say—after a little natural hesitation—is, that if ever you emerge without inconvenient effort from your ‘passive state,’ and will tell me of such faults as rise to the surface and strike you as important in my poems, (for of course, I do not think of troubling you with criticism in detail) you will confer a lasting obligation on me, and one which I shall value so much, that I covet it at a distance.

I do not pretend to any extraordinary meekness under criticism and it is possible enough that I might not be altogether obedient to yours. But with my high respect for your power in your Art and for your experience as an artist, it would be quite impossible for me to hear a general observation of yours on what appear to you my master-faults, without being the better for it hereafter in some way.

I ask for only a sentence or two of general observation — and I do not ask even for that, so as to tease you — but in the humble, low voice, which is so excellent a thing in women—particularly when they go a-begging!

The most frequent general criticism I receive, is, I think, upon the style — ‘if I would but change my style’! But that is an objection (isn’t it?) to the writer bodily? Buffon says, and every sincere writer must feel, that ‘Le style c’est l’homme’; a fact, however, scarcely calculated to lessen the objection with certain critics.

Is it indeed true that I was so near to the pleasure and honour of making your acquaintance? and can it be true that you look back upon the lost opportunity with any regret? But — you know — if you had entered the ‘crypt,’ you might have caught cold, or been tired to death, and wished yourself ‘a thousand miles off;’ which would have been worse than travelling them.

It is not my interest, however, to put such thoughts in your head about its being ‘all for the best’; and I would rather hope (as I do) that what I lost by one chance I may recover by some future one. Winters shut me up as they do dormouse’s eyes; in the spring, we shall see: and I am so much better that I seem turning round to the outward world again.

And in the meantime I have learnt to know your voice, not merely from the poetry but from the kindness in it. Mr. Kenyon often speaks of you—dear Mr. Kenyon!—who most unspeakably, or only speakably with tears in my eyes — has been my friend and helper, and my book’s friend and helper! critic and sympathiser, true friend of all hours!

You know him well enough, I think, to understand that I must be grateful to him.

I am writing too much,—and notwithstanding that I am writing too much, I will write of one thing more.

I will say that I am your debtor, not only for this cordial letter and for all the pleasure which came with it, but in other ways, and those the highest: and I will say that while I live to follow this divine art of poetry, in proportion to my love for it and my devotion to it, I must be a devout admirer and student of your works. This is in my heart to say to you—and I say it.

And, for the rest, I am proud to remain

Your obliged and faithful

Elizabeth B. Barrett

The post Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett: A Romantic Correspondence appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 16, 2023

Muriel Spark, Author of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie

Dame Muriel Spark (February 1, 1918 – April 13, 2006) was a Scottish novelist, short story writer, poet, and biographer.

Her novels were famous for their wit and style, and several have been adapted for film, television, and the stage. Her best-known work is the novelThe Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961).

Spark was quite prolific — in a nearly fifty-year career she wrote twenty-two novels, several collections of short stories, poetry, and nonfiction. She has been recognized as one of the greatest British writers.

Early years and education

Muriel Spark was born Muriel Sarah Camberg in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1918. Her father, Bernard, was Jewish and an engineer by profession. Her mother, Sarah, was a music teacher who had been raised Anglican.

She had one older brother, Philip, born in 1912, but the two were never close (with characteristic Spark wit, she once compared him to a Chekhov short story).

The family lived in the largely working-class Edinburgh suburb of Bruntsfield. Later, she would recall her childhood as financially tight but largely happy.

With the help of public bursaries, she went to the James Gillespie School for Girls, and then to a merchant school (much later, she would use this as the model for Marcia Blaine’s in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie).

Muriel was interested in literature from a young age, and at age fourteen won first prize in a poetry competition commemorating Sir Walter Scott’s death a century earlier in 1832.

She signed up to study commercial and precis writing at Heriot-Watt College in Edinburgh, but didn’t go on to university, partly because her parents could not afford it, and partly because, in her opinion, “many older girls who were studying at Edinburgh University were humanly rather dull and earnest, without adult style or charm.” Instead, she studied secretarial skills and later worked in an Edinburgh department store.

A disastrous marriage

In 1937 she met Sydney Oswald Spark, known as “SOS,” in Edinburgh. He was thirteen years older than her, and a teacher about to embark on a three-year stint in Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

They married in September of that year and she followed him to Africa. Their son, Samuel Robin (known as Robin), was born in 1938.

Not much is known about this part of her life, and Muriel rarely spoke about it. However, it soon became clear that her husband suffered from manic depression and increasingly experienced violent episodes.

She became more and more unhappy, and left both Africa and her marriage in 1944, initially leaving Robin behind.

Later she wrote: “I was attracted to a man who brought me flowers when I had flu. (From my experience of life I believe my personal motto should be ‘beware of men bringing flowers’.)” She chose, however, to keep her husband’s name: “Camberg was a good name, but comparatively flat. Spark seemed to have some ingredient of life and fun.”

When Robin arrived in London in 1945, she sent him to live with his grandparents in Edinburgh while she set about making a living in London. She took several different jobs, including a stint with the Political Intelligence Department of the Foreign Office, and as editor of the Poetry Society’s magazine, Poetry Review, from 1947 – 1949.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The 1950s, and conversion to CatholicismMuriel Spark was also writing and publishing her own poetry. A first collection, The Fanfarlo and Other Verse, was published in 1952, just a year after she had entered a competition run by the Observer newspaper and won (out of almost seven thousand entries) with her poem “The Seraph and the Zambesi”

In the early 1950s, she also worked with literary journalist Derek Stanford on critical studies of Mary Shelley, Emily Brontë, and John Masefield. She edited volumes of Emily Brontë poems, Brontë letters, and Mary Shelley letters.

The strain of living on the margins of literary London — always financially precarious, popping diet pills in place of meals, and never quite knowing what was coming next — began to wear on her, and she suffered an emotional and physical collapse in 1954.

It was also a profoundly spiritual collapse. The year before she had been baptized into the Church of England, influenced heavily by T. S. Eliot and his writing (which, at the height of her breakdown, she believed contained secret messages in Ancient Greek), but now decided to convert to Roman Catholicism.

In her convalescence, she was supported by fellow convert Graham Greene (who sent her money and red wine on the condition that she would never pray for him), while a priest found her the Camberwell bedsit from which she would write her early novels. But she was never able to fully articulate why faith and religion had become so important to her at this point in her life.

“The simple explanation,” she said later, “is that I felt the Roman Catholic faith corresponded to what I had always known and believed; the more difficult explanation would involve the step by step building up of a conviction.”

At the same time as her conversion to Catholicism, her son Robin was embracing Judaism. It caused a family rift when he claimed that his maternal great-grandmother was Jewish and petitioned for her to be posthumously recognized as such.

Muriel retaliated by accusing him of seeking publicity to advance his art career. This dispute, which dug deeply and painfully into family history and heritage, lasted until her death. She took steps to ensure that her son received nothing from her estate.

A rich writing career

Muriel’s conversion to Catholicism profoundly influenced her writing. In a later interview, she said “somehow with my religion – whether one has anything to do with the other, I don’t know – but it does seem so, that I just gained confidence.”

Penelope Fitzgerald, a contemporary and fellow novelist, perhaps put it more succinctly: “…it wasn’t until she became a Roman Catholic … that she was able to see human existence as a whole, as a novelist needs to do.”

The first of more than twenty novels, The Comforters, was published in 1957. It established Muriel Spark’s distinctive voice and received excellent reviews (including those by Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh, who wrote that he preferred The Comforters to his own The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold).

From then until the mid-1970s, she published almost a novel a year, as well as short stories, plays, essays, children’s books, and further collections of poetry.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie and other novelsWhat would become Muriel Spark’s best-known novel, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, was published in 1961.

The tale of the middle-aged Edinburgh schoolteacher became legendary. Its success on Broadway, and in film and television versions ensured that Muriel was financially secure for life. The 1969 film starred a young Maggie Smith, and is considered a cinematic classic.

Two other novels were also adapted for film: The Driver’s Seat (1970) starring Elizabeth Taylor and The Abbess of Crewe (1974) starring Glenda Jackson.

Other novels were adapted for television (The Girls of Slender Means published in 1963), for radio (The Ballad of Peckham Rye published in 1960), and for stage (Memento Mori and Doctors of Philosophy).

Escape to Italy

In 1963 Muriel left Britain for good. Mostly, she confessed, it was to escape those friends from whom her sudden success had estranged her. She was particularly keen to avoid Derek Stanford, who had published a conflicted, slightly disturbing memoir of her, based on the years they collaborated.

She moved first to New York, where she worked as a staff writer at The New Yorker. Editor William Shawn was a supporter of her writing, having published The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie in full in one issue of the magazine.

By the time she moved to Rome in 1967, she had invented herself almost as a character in one of her novels: chic, with perfect hair and nails, expensive jewelry and furs. Living in an immaculately decorated apartment just across from the Vatican, she self-styled as the epitome of wit and success.

In 1968 she met Penelope Jardine, a rich young woman studying art in Rome. Together they traveled to Oliveto in Tuscany and settled there to live and work. There they remained until Muriel’s death in 2006. Visitors reported that she was bright, happy, and less worried about dressing well: “There isn’t really a need for it here.” She enjoyed watching TV soaps in bed.

Muriel continued to write, sometimes spinning out stories in a single draft in spiral bound notebooks from the Edinburgh stationers James Thin, using one side of the paper only. Her last novel, aptly (or ironically) titled The Finishing School, was published in 2004.

Critical reception of Muriel Spark’s work

Muriel Spark was always something of a controversial author among certain readers. Her particular brand of waspish Catholic chic was often mistaken for right-wing tendencies, and feminists in particular often distrusted her work. In addition, the brevity of her novels led many critics to dismiss them as light and trivial.

However, more recently, John Lanchester, in his introduction to a Penguin edition of The Driver’s Seat, wrote that she should be viewed more as:

“… proto Post-Modernist, a writer with a sharp and lasting interest in the arbitrariness of fictional conventions; a writer whose eager adoption of the conventions of the novel have always been accompanied by a wish to toy with, subvert, parody, and undermine them.”

In a 2014 essay in The New Yorker, Parul Sehgal wrote of The Girls of Slender Means, “This is Spark’s particular genius: the cruelty mixed with camp, the lightness of touch, the flick of the wrist that lands the lash.”

She was also often referred to, especially during the 1990s, as “the greatest living British writer,” and counted W. H. Auden, John Updike, Tennessee Williams, and Iris Murdoch among her admirers.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Curriculum Vitae: A “clearly disappointing” autobiographyMuriel Spark rarely appeared on television or radio and was notoriously private about her life. This reticence helped to turn her 1992 autobiography, Curriculum Vitae, into the literary event of the year.

However, it was as notable for what it didn’t tell as for what it did. Like most of her books, it was short, and the narrative ended with the publication of her first novel.

Novelist Anita Brookner said that “as an account of a writer’s formation Curriculum Vitae is clearly disappointing,” while biographer Victoria Glendinning remarked that “one cannot tell from this book which people, if any, she loved with a passion.”

On the more positive side, Jenny Turner noted that “Although it skates over many things about which eager beavers may want to know more: Muriel’s disastrous teenage marriage … her twenties in Rhodesia … her son from that marriage … none of this is anybody’s business but Spark’s own.”

Muriel Spark’s legacy

Muriel Spark died on April 13, 2006, and is buried in the cemetery of Sant’ Andrea Apostolo in Oliveto. Her entire estate was left to Jardine, while her personal archive is held at the National Library of Scotland.

During her lifetime she received honorary degrees from universities including Oxford, Aberdeen, Edinburgh, London, and the American University of Paris. She was elected a Companion of Literature by the Royal Society of Literature, and an Honorary Member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

She was also an Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and was made a Dame of the British Empire in 1993.

Today, all of Muriel Spark’s novels remain in print and continue to be popular. In 2008, The Times of London ranked her eighth in its list of the “50 greatest British writers since 1945” and in 2010 she was posthumously shortlisted for the Lost Man Booker Prize of 1970 for The Driver’s Seat.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Muriel SparkMajor works: Novels, short stories, poems, and essays

All of Muriel Spark’s novels are still in print in various editions, including a full set of hardback Centenary Editions published by Polygon (Birlinn) in 2018. Muriel Spark’s list of published works is quite extensive; see her full bibliography.

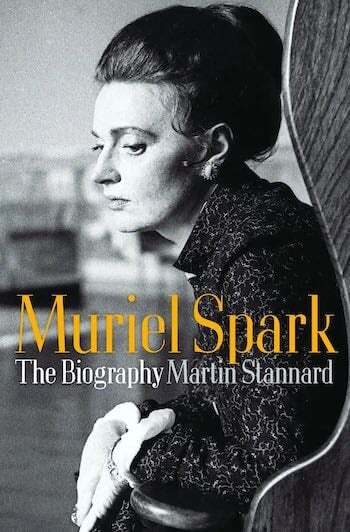

Biography and criticism

Curriculum Vitae by Muriel Spark (an autobiography, 1992)Muriel Spark: The Biography by Martin Stannard (2010)Appointment in Arezzo: A Friendship with Muriel Spark by Alan Taylor (2017)A Good Comb, edited by Penelope Jardine (2018)More information

Obituary in The Guardian Reader discussions of Muriel Spark’s books on Goodreads The Best Books by Muriel Spark Jewish Women’s Archive WikipediaThe post Muriel Spark, Author of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 1, 2023

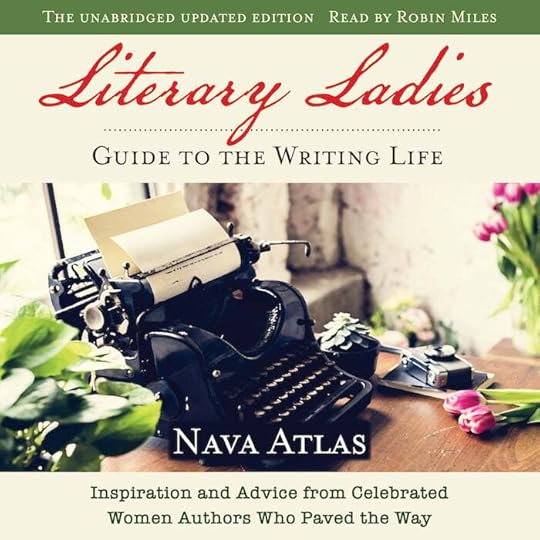

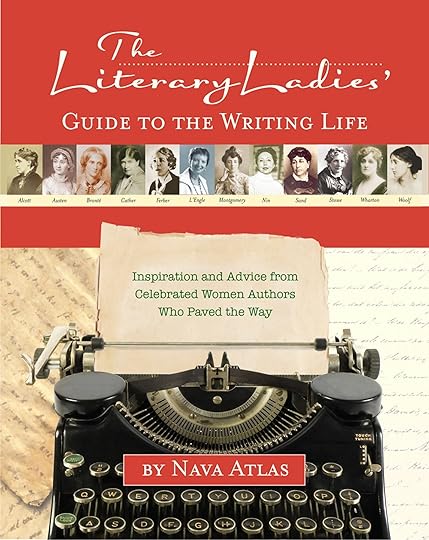

Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life by Nava Atlas

Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life: Inspiration and Advice from Celebrated Women Authors Who Paved the Way by Nava Atlas (2011) is now available as an audiobook (updated and expanded) produced by Blackstone Publishing (2023).

The desire to put pen to paper has been described by many writers as an obsession that can’t be denied. Perhaps best expressed by author Anaïs Nin, who writes, “You write out of a deep inner necessity. If you are a writer, you have to write, just as you have to breathe…”

In Literary Ladies’ Guide to the Writing Life, Nava Atlas presents a treasury of intimate glimpses into the unfolding writing process across fifteen brilliant careers in women’s literature and relates their struggles, striving, and successes to those experienced by women writers today.

About the 2023 audiobook

From the publisher: Author and artist Nava Atlas presents a treasury of intimate glimpses into the unfolding creative writing process across fifteen brilliant careers in women’s literature and relates their stories to women writers of today.

Through their journals, letters, and diaries, we get to know the struggles and triumphs of Louisa May Alcott, Jane Austen, Charlotte Bronte, Gwendolyn Brooks, Octavia E. Butler, Willa Cather, Madeleine LEngle, Edna Ferber, Zora Neale Hurston, L.M. Montgomery, Anais Nin, George Sand, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Edith Wharton, and Virginia Woolf.

Atlas’s own insightful commentary, newly updated, lifts the curtain on these women’s writing lives and provides reassuring tips and advice on such subjects as finding your voice, self-discipline, dealing with rejection, money matters, balancing family with the solitary writing process, and more. This guide will resonate with women writers in today’s world, at any stage of their journey.

Available on Audible, Apple, and wherever audiobooks can be downloaded

PLEASE NOTE: When you purchase this title from Audible, the accompanying PDF will be available in your Audible Library along with the audio.

©2011 Nava Atlas (P) 2023 Blackstone Publishing | Narrated by: Robin Miles | 6 hrs and 54 mins. . . . . . . . . . . .

About the 2011 book

In Literary Ladies’ Guide to the Writing Life, Nava Atlas presents a treasury of intimate glimpses into the unfolding creative writing process across twelve brilliant careers in women’s literature and relates their stories to women writers of today.

Drawing from diaries, journals, letters, memoirs and interviews, Atlas reveals the views of twelve classic women authors on the subjects of importance to every writer—the creative process, the inner critic, finding the time to write, rejection and acceptance, and developing a “voice.” The pages of this book are a feast for the eyes as well, with 130 vintage full-color photographs and illustrations

Atlas provides her own illuminating commentary and discusses how the lessons of classic women writers of the past still resonate with women writing in the present.

Within these pages, Atlas delves into the lives of these and other classic authors of the past to find lessons for women writing today. From learning how to stay disciplined, focused, and not getting distracted to finding tools of motivation and methods of practice, readers are able to find comfort and reassurance from some of our most beloved women authors.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

About Nava AtlasThough Nava is best known as the author of many books on vegan and vegetarian cooking, she also produces visual books on women’s issues, including the book shown here.

Nava Atlas is also an active fine artist. Her work is shown and collected by museums and universities across the U.S. You can see her work at navaatlasart.com. Her home is in the Hudson Valley region of New York State.

More about Nava can be found on her Wikipedia page, and in her permanent archive of papers at Duke University’s Rubenstein Library.

The post Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life by Nava Atlas appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 29, 2023

13 Love Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay

Though Edna St. Vincent Millay wasn’t considered a confessional poet, her prolific love life was often reflected in her lines, sometimes obliquely, other times directly. Following is a small sampling of love poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay.

Some of Millay’s love poems hint at cynicism, others sorrow, while others still reflect a women in full charge of her sexuality and aware of her power over those whose hearts she won — or broke.

It has been argued that tales of Millay’s love life have eclipsed her reputation as a poet — and that this should be corrected, as she was a brilliant poet. In hindsight unjustly, er reputation began waning even before her untimely death.

Vincent, as she preferred to be called, entered Vassar College in 1913 at age 21. Several years older than her fellow freshmen (who were women, as at the time it was an all-girls school), she soon became aware of her power to attract members of both sexes, and used this to her advantage in her journey to become one of the most celebrated poet of the 1920s and 1930s.

According to J.D. McClatchley, editor of Edna St. Vincent Millay: Selected Poems (2002):

“‘People fall in love with me … and annoy me and distress me and flatter me and excite me.’ And she responded in kind; there were torrid affairs with girls at school, adding to her campus notoriety, and tepid flings with older men who might help her career.

Throughout her life, she did what she felt she must do in order to create the conditions necessary to accomplish her work … After Vassar, she became the Circe of Greenwich Village. She was soon the talk of the town.

Her affairs were sometimes of the heart, and sometimes more practical. The writers she took as lovers (and invariably kept as friends afterward) … were in a position to both teach and help her. And she had always been a quick study. The poems she wrote then — wild, cool, elusive — intoxicated the Jazz Babies. She had found the pulse of the new generation.”

The love poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay presented here are from her first four collections; all are in the public domain. The poems included here are:

Ashes of LifeThe DreamIndifferenceRecuerdoThursdayThe PhilosopherPasser Mortuus EstAlms EbbI, Being Born a WomanWhat Lips My Lips Have KissedLoving You Less Than LifeThe Spring and the Fall. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Edna St. Vincent Millay

. . . . . . . . . .

This is but a sampling of Millay’s poems that deal with the affairs of the heart. You’ll find these early collections in full on this site:

Renascence and Other Poems A Few Figs From Thistles Second April The Harp-Weaver and Other Poems See another sampling: 12 Iconic Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay .. . . . . . . . . .

ASHES OF LIFE

Love has gone and left me and the days are all alike;

Eat I must, and sleep I will,—and would that night were here!

But ah!—to lie awake and hear the slow hours strike!

Would that it were day again!—with twilight near!

Love has gone and left me and I don’t know what to do;

This or that or what you will is all the same to me;

But all the things that I begin I leave before I’m through,—

There’s little use in anything as far as I can see.

Love has gone and left me,—and the neighbors knock and borrow,

And life goes on forever like the gnawing of a mouse,—

And to-morrow and to-morrow and to-morrow and to-morrow

There’s this little street and this little house.

(From Renascence and other Poems, 1917

Analysis of “Ashes of Life”)

. . . . . . . . . .

THE DREAM

Love, if I weep it will not matter,

And if you laugh I shall not care;

Foolish am I to think about it,

But it is good to feel you there.

Love, in my sleep I dreamed of waking,—

White and awful the moonlight reached

Over the floor, and somewhere, somewhere,

There was a shutter loose,—it screeched!

Swung in the wind,—and no wind blowing!—

I was afraid, and turned to you,

Put out my hand to you for comfort,—

And you were gone! Cold, cold as dew,

Under my hand the moonlight lay!

Love, if you laugh I shall not care,

But if I weep it will not matter,—

Ah, it is good to feel you there!

(From Renascence and other Poems, 1917)

. . . . . . . . . .

INDIFFERENCE

I said,—for Love was laggard, O, Love was slow to come,—

“I’ll hear his step and know his step when I am warm in bed;

But I’ll never leave my pillow, though there be some

As would let him in—and take him in with tears!” I said.

I lay,—for Love was laggard, O, he came not until dawn,—

I lay and listened for his step and could not get to sleep;

And he found me at my window with my big cloak on,

All sorry with the tears some folks might weep!

(From Renascence and other Poems, 1917)

. . . . . . . . . .

RECUERDO

We were very tired, we were very merry—

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry.

It was bare and bright, and smelled like a stable—

But we looked into a fire, we leaned across a table,

We lay on a hill-top underneath the moon;

And the whistles kept blowing, and the dawn came soon.

We were very tired, we were very merry—

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry;

And you ate an apple, and I ate a pear,

From a dozen of each we had bought somewhere;

And the sky went wan, and the wind came cold,

And the sun rose dripping, a bucketful of gold.

We were very tired, we were very merry,

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry.

We hailed, “Good morrow, mother!” to a shawl-covered head,

And bought a morning paper, which neither of us read;

And she wept, “God bless you!” for the apples and pears,

And we gave her all our money but our subway fares.

(From A Few Figs from Thistles, 1921

Analysis of “Recuerdo”)

. . . . . . . . .

THURSDAY

And if I loved you Wednesday,

Well, what is that to you?

I do not love you Thursday—

So much is true.

And why you come complaining

Is more than I can see.

I loved you Wednesday,—yes—but what

Is that to me?

(From A Few Figs from Thistles, 1921

Analysis of “Thursday”)

. . . . . . . . . .

THE PHILOSOPHER

And what are you that, wanting you

I should be kept awake

As many nights as there are days

With weeping for your sake?

And what are you that, missing you,

As many days as crawl

I should be listening to the wind

And looking at the wall?

I know a man that’s a braver man

And twenty men as kind,

And what are you, that you should be

The one man in my mind?

Yet women’s ways are witless ways,

As any sage will tell,—

And what am I, that I should love

So wisely and so well?

(From A Few Figs from Thistles, 1921)

. . . . . . . . . .

PASSER MORTUUS EST

Death devours all lovely things;

Lesbia with her sparrow

Shares the darkness,—presently

Every bed is narrow.

Unremembered as old rain

Dries the sheer libation,

And the little petulant hand

Is an annotation.

After all, my erstwhile dear,

My no longer cherished,

Need we say it was not love,

Now that love is perished?

(From Second April, 1921)

. . . . . . . . . .

ALMS

My heart is what it was before,

A house where people come and go;

But it is winter with your love,

The sashes are beset with snow.

I light the lamp and lay the cloth,

I blow the coals to blaze again;

But it is winter with your love,

The frost is thick upon the pane.

I know a winter when it comes:

The leaves are listless on the boughs;

I watched your love a little while,

And brought my plants into the house.

I water them and turn them south,

I snap the dead brown from the stem;

But it is winter with your love,—

I only tend and water them.

There was a time I stood and watched

The small, ill-natured sparrows’ fray;

I loved the beggar that I fed,

I cared for what he had to say,

I stood and watched him out of sight;

Today I reach around the door

And set a bowl upon the step;

My heart is what it was before,

But it is winter with your love;

I scatter crumbs upon the sill,

And close the window,—and the birds

May take or leave them, as they will.

(From Second April, 1921

Analysis of “Alms”)

. . . . . . . . . .

EBB

I know what my heart is like

Since your love died:

It is like a hollow ledge

Holding a little pool

Left there by the tide,

A little tepid pool,

Drying inward from the edge.

(From Second April, 1921

Analysis of “Ebb”)

. . . . . . . . . .

I, BEING BORN A WOMAN

I, being born a woman and distressed

By all the needs and notions of my kind,

Am urged by your propinquity to find

Your person fair, and feel a certain zest

To bear your body’s weight upon my breast:

So subtly is the fume of life designed,

To clarify the pulse and cloud the mind,

And leave me once again undone, possessed.

Think not for this, however, the poor treason

Of my stout blood against my staggering brain,

I shall remember you with love, or season

My scorn with pity, — let me make it plain:

I find this frenzy insufficient reason

For conversation when we meet again.

(From The Harp-Weaver and Other Poems, 1922

Analysis of “I, Being Born a Woman“)

. . . . . . . . . .

WHAT LIPS MY LIPS HAVE KISSED

What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and

why,

I have forgotten, and what arms have lain

Under my head till morning; but the rain

Is full of ghosts to-night, that tap and sigh

Upon the glass and listen for reply,

And in my heart there stirs a quiet pain

For unremembered lads that not again

Will turn to me at midnight with a cry.

Thus in the winter stands the lonely tree,

Nor knows what birds have vanished one by one,

Yet knows its boughs more silent than before:

I cannot say what loves have come and gone,

I only know that summer sang in me

A little while, that in me sings no more.

(From The Harp-Weaver and Other Poems, 1922

Analysis of “What Lips My Lips Have Kissed”)

. . . . . . . . . .

LOVING YOU LESS THAN LIFE

Loving you less than life, a little less

Than bitter-sweet upon a broken wall

Or brush-wood smoke in autumn, I confess

I cannot swear I love you not at all.

For there is that about you in this light–

A yellow darkness, sinister of rain–

Which sturdily recalls my stubborn sight

To dwell on you, and dwell on you again.

And I am made aware of many a week

I shall consume, remembering in what way

Your brown hair grows about your brow and

cheek,

And what divine absurdities you say:

Till all the world, and I, and surely you,

Will know I love you, whether or not I do.

(From The Harp-Weaver and Other Poems, 1922)

. . . . . . . . . .

THE SPRING AND THE FALL

In the spring of the year, in the spring of the year,

I walked the road beside my dear.

The trees were black where the bark was wet.

I see them yet, in the spring of the year.

He broke me a bough of the blossoming peach

That was out of the way and hard to reach.

In the fall of the year, in the fall of the year,

I walked the road beside my dear.

The rooks went up with a raucous trill.

I hear them still, in the fall of the year.

He laughed at all I dared to praise,

And broke my heart, in little ways.

Year be springing or year be falling,

The bark will drip and the birds be calling.

There’s much that’s fine to see and hear

In the spring of a year, in the fall of a year.

‘Tis not love’s going hurts my days,

But that it went in little ways.

(From The Harp-Weaver and Other Poems, 1922)

The post 13 Love Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 28, 2023

The Daughters of the Late Colonel by Katherine Mansfield (full text)

“The Daughters of the Late Colonel” by Katherine Mansfield is a modernist short story. New Zealand-born Mansfield (1888 – 1923) has been recognized for revolutionizing the short story form.

“The Daughters of the Late Colonel” is considered among her most highly regarded stories, along with “At the Bay,” “The Voyage,” and “The Stranger.”

Written in 1920, this story (now in the public domain) was first published in The London Mercury in 1921, and was later part of Mansfield’s short story collection, The Garden Party and Other Stories.

Summaries and analyses of The Daughters of the Late Colonel

Summary and analysis on LitCharts A short analysis on Interesting Literature Analysis on Literary Theory and Criticism. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Katherine Mansfield

. . . . . . . . . .

I

The week after was one of the busiest weeks of their lives. Even when they went to bed it was only their bodies that lay down and rested; their minds went on, thinking things out, talking things over, wondering, deciding, trying to remember where …

Constantia lay like a statue, her hands by her sides, her feet just overlapping each other, the sheet up to her chin. She stared at the ceiling.

“Do you think father would mind if we gave his top-hat to the porter?”

“The porter?” snapped Josephine. “Why ever the porter? What a very extraordinary idea!”

“Because,” said Constantia slowly, “he must often have to go to funerals. And I noticed at—at the cemetery that he only had a bowler.” She paused. “I thought then how very much he’d appreciate a top-hat. We ought to give him a present, too. He was always very nice to father.”

“But,” cried Josephine, flouncing on her pillow and staring across the dark at Constantia, “father’s head!” And suddenly, for one awful moment, she nearly giggled. Not, of course, that she felt in the least like giggling. It must have been habit.

Years ago, when they had stayed awake at night talking, their beds had simply heaved. And now the porter’s head, disappearing, popped out, like a candle, under father’s hat…. The giggle mounted, mounted; she clenched her hands; she fought it down; she frowned fiercely at the dark and said “Remember” terribly sternly.

“We can decide to-morrow,” she said.

Constantia had noticed nothing; she sighed.

“Do you think we ought to have our dressing-gowns dyed as well?”

“Black?” almost shrieked Josephine.

“Well, what else?” said Constantia. “I was thinking—it doesn’t seem quite sincere, in a way, to wear black out of doors and when we’re fully dressed, and then when we’re at home—”

“But nobody sees us,” said Josephine. She gave the bedclothes such a twitch that both her feet became uncovered, and she had to creep up the pillows to get them well under again.

“Kate does,” said Constantia. “And the postman very well might.”

Josephine thought of her dark-red slippers, which matched her dressing-gown, and of Constantia’s favourite indefinite green ones which went with hers. Black! Two black dressing-gowns and two pairs of black woolly slippers, creeping off to the bathroom like black cats.

“I don’t think it’s absolutely necessary,” said she.

Silence. Then Constantia said, “We shall have to post the papers with the notice in them to-morrow to catch the Ceylon mail…. How many letters have we had up till now?”

“Twenty-three.”

Josephine had replied to them all, and twenty-three times when she came to “We miss our dear father so much” she had broken down and had to use her handkerchief, and on some of them even to soak up a very light-blue tear with an edge of blotting-paper. Strange! She couldn’t have put it on—but twenty-three times. Even now, though, when she said over to herself sadly “We miss our dear father so much,” she could have cried if she’d wanted to.

“Have you got enough stamps?” came from Constantia.

“Oh, how can I tell?” said Josephine crossly. “What’s the good of asking me that now?”

“I was just wondering,” said Constantia mildly.

Silence again. There came a little rustle, a scurry, a hop.

“A mouse,” said Constantia.

“It can’t be a mouse because there aren’t any crumbs,” said Josephine.

“But it doesn’t know there aren’t,” said Constantia.

A spasm of pity squeezed her heart. Poor little thing! She wished she’d left a tiny piece of biscuit on the dressing-table. It was awful to think of it not finding anything. What would it do?

“I can’t think how they manage to live at all,” she said slowly.

“Who?” demanded Josephine.

And Constantia said more loudly than she meant to, “Mice.”

Josephine was furious. “Oh, what nonsense, Con!” she said. “What have mice got to do with it? You’re asleep.”

“I don’t think I am,” said Constantia. She shut her eyes to make sure. She was.

Josephine arched her spine, pulled up her knees, folded her arms so that her fists came under her ears, and pressed her cheek hard against the pillow.

. . . . . . . . . .

MORE FULL TEXTS OF MANSFIELD SHORT STORIES

“Bliss ” (1918)

“Miss Brill” (1920)

“The Garden Party” (1920)

. . . . . . . . . .

II

Another thing which complicated matters was they had Nurse Andrews staying on with them that week. It was their own fault; they had asked her. It was Josephine’s idea. On the morning—well, on the last morning, when the doctor had gone, Josephine had said to Constantia, “Don’t you think it would be rather nice if we asked Nurse Andrews to stay on for a week as our guest?”

“Very nice,” said Constantia.

“I thought,” went on Josephine quickly, “I should just say this afternoon, after I’ve paid her, ‘My sister and I would be very pleased, after all you’ve done for us, Nurse Andrews, if you would stay on for a week as our guest.’ I’d have to put that in about being our guest in case —”

“Oh, but she could hardly expect to be paid!” cried Constantia.

“One never knows,” said Josephine sagely.

Nurse Andrews had, of course, jumped at the idea. But it was a bother. It meant they had to have regular sit-down meals at the proper times, whereas if they’d been alone they could just have asked Kate if she wouldn’t have minded bringing them a tray wherever they were. And meal-times now that the strain was over were rather a trial.

Nurse Andrews was simply fearful about butter. Really they couldn’t help feeling that about butter, at least, she took advantage of their kindness. And she had that maddening habit of asking for just an inch more of bread to finish what she had on her plate, and then, at the last mouthful, absent-mindedly—of course it wasn’t absent-mindedly—taking another helping.

Josephine got very red when this happened, and she fastened her small, bead-like eyes on the tablecloth as if she saw a minute strange insect creeping through the web of it. But Constantia’s long, pale face lengthened and set, and she gazed away—away—far over the desert, to where that line of camels unwound like a thread of wool …

“When I was with Lady Tukes,” said Nurse Andrews, “she had such a dainty little contrayvance for the buttah. It was a silvah Cupid balanced on the—on the bordah of a glass dish, holding a tayny fork. And when you wanted some buttah you simply pressed his foot and he bent down and speared you a piece. It was quite a gayme.”

Josephine could hardly bear that. But “I think those things are very extravagant” was all she said.

“But whey?” asked Nurse Andrews, beaming through her eyeglasses. “No one, surely, would take more buttah than one wanted—would one?”

“Ring, Con,” cried Josephine. She couldn’t trust herself to reply.

And proud young Kate, the enchanted princess, came in to see what the old tabbies wanted now. She snatched away their plates of mock something or other and slapped down a white, terrified blancmange.

“Jam, please, Kate,” said Josephine kindly.

Kate knelt and burst open the sideboard, lifted the lid of the jam-pot, saw it was empty, put it on the table, and stalked off.

“I’m afraid,” said Nurse Andrews a moment later, “there isn’t any.”

“Oh, what a bother!” said Josephine. She bit her lip. “What had we better do?”

Constantia looked dubious. “We can’t disturb Kate again,” she said softly.

Nurse Andrews waited, smiling at them both. Her eyes wandered, spying at everything behind her eyeglasses. Constantia in despair went back to her camels. Josephine frowned heavily—concentrated. If it hadn’t been for this idiotic woman she and Con would, of course, have eaten their blancmange without. Suddenly the idea came.

“I know,” she said. “Marmalade. There’s some marmalade in the sideboard. Get it, Con.”

“I hope,” laughed Nurse Andrews—and her laugh was like a spoon tinkling against a medicine-glass—“I hope it’s not very bittah marmalayde.”

III

But, after all, it was not long now, and then she’d be gone for good. And there was no getting over the fact that she had been very kind to father. She had nursed him day and night at the end. Indeed, both Constantia and Josephine felt privately she had rather overdone the not leaving him at the very last.

For when they had gone in to say good-bye Nurse Andrews had sat beside his bed the whole time, holding his wrist and pretending to look at her watch. It couldn’t have been necessary. It was so tactless, too.

Supposing father had wanted to say something—something private to them. Not that he had. Oh, far from it! He lay there, purple, a dark, angry purple in the face, and never even looked at them when they came in. Then, as they were standing there, wondering what to do, he had suddenly opened one eye.

Oh, what a difference it would have made, what a difference to their memory of him, how much easier to tell people about it, if he had only opened both! But no—one eye only. It glared at them a moment and then… went out.

IV

It had made it very awkward for them when Mr. Farolles, of St. John’s, called the same afternoon.

“The end was quite peaceful, I trust?” were the first words he said as he glided towards them through the dark drawing-room.

“Quite,” said Josephine faintly. They both hung their heads. Both of them felt certain that eye wasn’t at all a peaceful eye.

“Won’t you sit down?” said Josephine.

“Thank you, Miss Pinner,” said Mr. Farolles gratefully. He folded his coat-tails and began to lower himself into father’s arm-chair, but just as he touched it he almost sprang up and slid into the next chair instead.

He coughed. Josephine clasped her hands; Constantia looked vague.

“I want you to feel, Miss Pinner,” said Mr. Farolles, “and you, Miss Constantia, that I’m trying to be helpful. I want to be helpful to you both, if you will let me. These are the times,” said Mr Farolles, very simply and earnestly, “when God means us to be helpful to one another.”

“Thank you very much, Mr. Farolles,” said Josephine and Constantia.

“Not at all,” said Mr. Farolles gently. He drew his kid gloves through his fingers and leaned forward. “And if either of you would like a little Communion, either or both of you, here and now, you have only to tell me. A little Communion is often very help—a great comfort,” he added tenderly.

But the idea of a little Communion terrified them. What! In the drawing-room by themselves—with no—no altar or anything! The piano would be much too high, thought Constantia, and Mr. Farolles could not possibly lean over it with the chalice.

And Kate would be sure to come bursting in and interrupt them, thought Josephine. And supposing the bell rang in the middle? It might be somebody important—about their mourning. Would they get up reverently and go out, or would they have to wait… in torture?

“Perhaps you will send round a note by your good Kate if you would care for it later,” said Mr. Farolles.

“Oh yes, thank you very much!” they both said.

Mr. Farolles got up and took his black straw hat from the round table.

“And about the funeral,” he said softly. “I may arrange that—as your dear father’s old friend and yours, Miss Pinner — and Miss Constantia?”

Josephine and Constantia got up too.

“I should like it to be quite simple,” said Josephine firmly, “and not too expensive. At the same time, I should like —”

“A good one that will last,” thought dreamy Constantia, as if Josephine were buying a nightgown. But, of course, Josephine didn’t say that. “One suitable to our father’s position.” She was very nervous.

“I’ll run round to our good friend Mr. Knight,” said Mr. Farolles soothingly. “I will ask him to come and see you. I am sure you will find him very helpful indeed.”

V

Well, at any rate, all that part of it was over, though neither of them could possibly believe that father was never coming back. Josephine had had a moment of absolute terror at the cemetery, while the coffin was lowered, to think that she and Constantia had done this thing without asking his permission. What would father say when he found out? For he was bound to find out sooner or later. He always did.

“Buried. You two girls had me buried!” She heard his stick thumping. Oh, what would they say? What possible excuse could they make? It sounded such an appallingly heartless thing to do. Such a wicked advantage to take of a person because he happened to be helpless at the moment. The other people seemed to treat it all as a matter of course.

They were strangers; they couldn’t be expected to understand that father was the very last person for such a thing to happen to. No, the entire blame for it all would fall on her and Constantia. And the expense, she thought, stepping into the tight-buttoned cab. When she had to show him the bills. What would he say then?

She heard him absolutely roaring. “And do you expect me to pay for this gimcrack excursion of yours?”

“Oh,” groaned poor Josephine aloud, “we shouldn’t have done it, Con!”

And Constantia, pale as a lemon in all that blackness, said in a frightened whisper, “Done what, Jug?”

“Let them bu-bury father like that,” said Josephine, breaking down and crying into her new, queer-smelling mourning handkerchief.

“But what else could we have done?” asked Constantia wonderingly. “We couldn’t have kept him, Jug—we couldn’t have kept him unburied. At any rate, not in a flat that size.”

Josephine blew her nose; the cab was dreadfully stuffy.

“I don’t know,” she said forlornly. “It is all so dreadful. I feel we ought to have tried to, just for a time at least. To make perfectly sure. One thing’s certain”—and her tears sprang out again—“father will never forgive us for this—never!”

VI

Father would never forgive them. That was what they felt more than ever when, two mornings later, they went into his room to go through his things. They had discussed it quite calmly. It was even down on Josephine’s list of things to be done. “Go through father’s things and settle about them.” But that was a very different matter from saying after breakfast:

“Well, are you ready, Con?”

“Yes, Jug—when you are.”

“Then I think we’d better get it over.”

It was dark in the hall. It had been a rule for years never to disturb father in the morning, whatever happened. And now they were going to open the door without knocking even…. Constantia’s eyes were enormous at the idea; Josephine felt weak in the knees.

“You—you go first,” she gasped, pushing Constantia.

But Constantia said, as she always had said on those occasions, “No, Jug, that’s not fair. You’re the eldest.”

Josephine was just going to say—what at other times she wouldn’t have owned to for the world—what she kept for her very last weapon, “But you’re the tallest,” when they noticed that the kitchen door was open, and there stood Kate …

“Very stiff,” said Josephine, grasping the door handle and doing her best to turn it. As if anything ever deceived Kate!

It couldn’t be helped. That girl was…. Then the door was shut behind them, but—but they weren’t in father’s room at all. They might have suddenly walked through the wall by mistake into a different flat altogether.

Was the door just behind them? They were too frightened to look. Josephine knew that if it was it was holding itself tight shut; Constantia felt that, like the doors in dreams, it hadn’t any handle at all. It was the coldness which made it so awful. Or the whiteness—which?

Everything was covered. The blinds were down, a cloth hung over the mirror, a sheet hid the bed; a huge fan of white paper filled the fireplace. Constantia timidly put out her hand; she almost expected a snowflake to fall.

Josephine felt a queer tingling in her nose, as if her nose was freezing. Then a cab klop-klopped over the cobbles below, and the quiet seemed to shake into little pieces.

“I had better pull up a blind,” said Josephine bravely.

“Yes, it might be a good idea,” whispered Constantia.

They only gave the blind a touch, but it flew up and the cord flew after, rolling round the blind-stick, and the little tassel tapped as if trying to get free. That was too much for Constantia.

“Don’t you think—don’t you think we might put it off for another day?” she whispered.

“Why?” snapped Josephine, feeling, as usual, much better now that she knew for certain that Constantia was terrified. “It’s got to be done. But I do wish you wouldn’t whisper, Con.”

“I didn’t know I was whispering,” whispered Constantia.

“And why do you keep staring at the bed?” said Josephine, raising her voice almost defiantly. “There’s nothing on the bed.”

“Oh, Jug, don’t say so!” said poor Connie. “At any rate, not so loudly.”

Josephine felt herself that she had gone too far. She took a wide swerve over to the chest of drawers, put out her hand, but quickly drew it back again.

“Connie!” she gasped, and she wheeled round and leaned with her back against the chest of drawers.

“Oh, Jug—what?”

Josephine could only glare. She had the most extraordinary feeling that she had just escaped something simply awful. But how could she explain to Constantia that father was in the chest of drawers? He was in the top drawer with his handkerchiefs and neckties, or in the next with his shirts and pyjamas, or in the lowest of all with his suits. He was watching there, hidden away—just behind the door-handle—ready to spring.

She pulled a funny old-fashioned face at Constantia, just as she used to in the old days when she was going to cry.

“I can’t open,” she nearly wailed.

“No, don’t, Jug,” whispered Constantia earnestly. “It’s much better not to. Don’t let’s open anything. At any rate, not for a long time.”

“But—but it seems so weak,” said Josephine, breaking down.

“But why not be weak for once, Jug?” argued Constantia, whispering quite fiercely. “If it is weak.” And her pale stare flew from the locked writing-table—so safe—to the huge glittering wardrobe, and she began to breathe in a queer, panting away.

“Why shouldn’t we be weak for once in our lives, Jug? It’s quite excusable. Let’s be weak—be weak, Jug. It’s much nicer to be weak than to be strong.”

And then she did one of those amazingly bold things that she’d done about twice before in their lives: she marched over to the wardrobe, turned the key, and took it out of the lock. Took it out of the lock and held it up to Josephine, showing Josephine by her extraordinary smile that she knew what she’d done—she’d risked deliberately father being in there among his overcoats.

If the huge wardrobe had lurched forward, had crashed down on Constantia, Josephine wouldn’t have been surprised. On the contrary, she would have thought it the only suitable thing to happen. But nothing happened. Only the room seemed quieter than ever, and the bigger flakes of cold air fell on Josephine’s shoulders and knees. She began to shiver.

“Come, Jug,” said Constantia, still with that awful callous smile, and Josephine followed just as she had that last time, when Constantia had pushed Benny into the round pond.

VII

But the strain told on them when they were back in the dining-room. They sat down, very shaky, and looked at each other.

“I don’t feel I can settle to anything,” said Josephine, “until I’ve had something. Do you think we could ask Kate for two cups of hot water?”

“I really don’t see why we shouldn’t,” said Constantia carefully. She was quite normal again. “I won’t ring. I’ll go to the kitchen door and ask her.”

“Yes, do,” said Josephine, sinking down into a chair. “Tell her, just two cups, Con, nothing else—on a tray.”

“She needn’t even put the jug on, need she?” said Constantia, as though Kate might very well complain if the jug had been there.

“Oh no, certainly not! The jug’s not at all necessary. She can pour it direct out of the kettle,” cried Josephine, feeling that would be a labour-saving indeed.

Their cold lips quivered at the greenish brims. Josephine curved her small red hands round the cup; Constantia sat up and blew on the wavy steam, making it flutter from one side to the other.

“Speaking of Benny,” said Josephine.

And though Benny hadn’t been mentioned Constantia immediately looked as though he had.

“He’ll expect us to send him something of father’s, of course. But it’s so difficult to know what to send to Ceylon.”

“You mean things get unstuck so on the voyage,” murmured Constantia.

“No, lost,” said Josephine sharply. “You know there’s no post. Only runners.”

Both paused to watch a black man in white linen drawers running through the pale fields for dear life, with a large brown-paper parcel in his hands. Josephine’s black man was tiny; he scurried along glistening like an ant. But there was something blind and tireless about Constantia’s tall, thin fellow, which made him, she decided, a very unpleasant person indeed …

On the veranda, dressed all in white and wearing a cork helmet, stood Benny. His right hand shook up and down, as father’s did when he was impatient. And behind him, not in the least interested, sat Hilda, the unknown sister-in-law. She swung in a cane rocker and flicked over the leaves of the Tattler.

“I think his watch would be the most suitable present,” said Josephine.

Constantia looked up; she seemed surprised.

“Oh, would you trust a gold watch to a native?”

“But of course, I’d disguise it,” said Josephine. “No one would know it was a watch.” She liked the idea of having to make a parcel such a curious shape that no one could possibly guess what it was. She even thought for a moment of hiding the watch in a narrow cardboard corset-box that she’d kept by her for a long time, waiting for it to come in for something.

It was such beautiful, firm cardboard. But, no, it wouldn’t be appropriate for this occasion. It had lettering on it: Medium Women’s 28. Extra Firm Busks. It would be almost too much of a surprise for Benny to open that and find father’s watch inside.

“And of course it isn’t as though it would be going—ticking, I mean,” said Constantia, who was still thinking of the native love of jewellery. “At least,” she added, “it would be very strange if after all that time it was.”

VIII

Josephine made no reply. She had flown off on one of her tangents. She had suddenly thought of Cyril. Wasn’t it more usual for the only grandson to have the watch? And then dear Cyril was so appreciative, and a gold watch meant so much to a young man. Benny, in all probability, had quite got out of the habit of watches; men so seldom wore waistcoats in those hot climates.

Whereas Cyril in London wore them from year’s end to year’s end. And it would be so nice for her and Constantia, when he came to tea, to know it was there. “I see you’ve got on grandfather’s watch, Cyril.” It would be somehow so satisfactory.

Dear boy! What a blow his sweet, sympathetic little note had been! Of course they quite understood; but it was most unfortunate.

“It would have been such a point, having him,” said Josephine.

“And he would have enjoyed it so,” said Constantia, not thinking what she was saying.

However, as soon as he got back he was coming to tea with his aunties. Cyril to tea was one of their rare treats.

“Now, Cyril, you mustn’t be frightened of our cakes. Your Auntie Con and I bought them at Buszard’s this morning. We know what a man’s appetite is. So don’t be ashamed of making a good tea.”

Josephine cut recklessly into the rich dark cake that stood for her winter gloves or the soling and heeling of Constantia’s only respectable shoes. But Cyril was most unmanlike in appetite.

“I say, Aunt Josephine, I simply can’t. I’ve only just had lunch, you know.”

“Oh, Cyril, that can’t be true! It’s after four,” cried Josephine. Constantia sat with her knife poised over the chocolate-roll.

“It is, all the same,” said Cyril. “I had to meet a man at Victoria, and he kept me hanging about till… there was only time to get lunch and to come on here. And he gave me—phew”—Cyril put his hand to his forehead—“a terrific blow-out,” he said.

It was disappointing—to-day of all days. But still he couldn’t be expected to know.

“But you’ll have a meringue, won’t you, Cyril?” said Aunt Josephine. “These meringues were bought specially for you. Your dear father was so fond of them. We were sure you are, too.”

“I am, Aunt Josephine,” cried Cyril ardently. “Do you mind if I take half to begin with?”

“Not at all, dear boy; but we mustn’t let you off with that.”

“Is your dear father still so fond of meringues?” asked Auntie Con gently. She winced faintly as she broke through the shell of hers.

“Well, I don’t quite know, Auntie Con,” said Cyril breezily.

At that they both looked up.

“Don’t know?” almost snapped Josephine. “Don’t know a thing like that about your own father, Cyril?”

“Surely,” said Auntie Con softly.

Cyril tried to laugh it off. “Oh, well,” he said, “it’s such a long time since—” He faltered. He stopped. Their faces were too much for him.

“Even so,” said Josephine.

And Auntie Con looked.

Cyril put down his teacup. “Wait a bit,” he cried. “Wait a bit, Aunt Josephine. What am I thinking of?”

He looked up. They were beginning to brighten. Cyril slapped his knee.

“Of course,” he said, “it was meringues. How could I have forgotten? Yes, Aunt Josephine, you’re perfectly right. Father’s most frightfully keen on meringues.”

They didn’t only beam. Aunt Josephine went scarlet with pleasure; Auntie Con gave a deep, deep sigh.

“And now, Cyril, you must come and see father,” said Josephine. “He knows you were coming to-day.”

“Right,” said Cyril, very firmly and heartily. He got up from his chair; suddenly he glanced at the clock.

“I say, Auntie Con, isn’t your clock a bit slow? I’ve got to meet a man at—at Paddington just after five. I’m afraid I shan’t be able to stay very long with grandfather.”

“Oh, he won’t expect you to stay very long!” said Aunt Josephine.

Constantia was still gazing at the clock. She couldn’t make up her mind if it was fast or slow. It was one or the other, she felt almost certain of that. At any rate, it had been.

Cyril still lingered. “Aren’t you coming along, Auntie Con?”

“Of course,” said Josephine, “we shall all go. Come on, Con.”

IX

They knocked at the door, and Cyril followed his aunts into grandfather’s hot, sweetish room.

“Come on,” said Grandfather Pinner. “Don’t hang about. What is it? What’ve you been up to?”

He was sitting in front of a roaring fire, clasping his stick. He had a thick rug over his knees. On his lap there lay a beautiful pale yellow silk handkerchief.

“It’s Cyril, father,” said Josephine shyly. And she took Cyril’s hand and led him forward.

“Good afternoon, grandfather,” said Cyril, trying to take his hand out of Aunt Josephine’s. Grandfather Pinner shot his eyes at Cyril in the way he was famous for. Where was Auntie Con? She stood on the other side of Aunt Josephine; her long arms hung down in front of her; her hands were clasped. She never took her eyes off grandfather.

“Well,” said Grandfather Pinner, beginning to thump, “what have you got to tell me?”

What had he, what had he got to tell him? Cyril felt himself smiling like a perfect imbecile. The room was stifling, too.

But Aunt Josephine came to his rescue. She cried brightly, “Cyril says his father is still very fond of meringues, father dear.”

“Eh?” said Grandfather Pinner, curving his hand like a purple meringue-shell over one ear.

Josephine repeated, “Cyril says his father is still very fond of meringues.”

“Can’t hear,” said old Colonel Pinner. And he waved Josephine away with his stick, then pointed with his stick to Cyril. “Tell me what she’s trying to say,” he said.

(My God!) “Must I?” said Cyril, blushing and staring at Aunt Josephine.

“Do, dear,” she smiled. “It will please him so much.”

“Come on, out with it!” cried Colonel Pinner testily, beginning to thump again.

And Cyril leaned forward and yelled, “Father’s still very fond of meringues.”

At that Grandfather Pinner jumped as though he had been shot.

“Don’t shout!” he cried. “What’s the matter with the boy? Meringues! What about ’em?”

“Oh, Aunt Josephine, must we go on?” groaned Cyril desperately.

“It’s quite all right, dear boy,” said Aunt Josephine, as though he and she were at the dentist’s together. “He’ll understand in a minute.” And she whispered to Cyril, “He’s getting a bit deaf, you know.” Then she leaned forward and really bawled at Grandfather Pinner, “Cyril only wanted to tell you, father dear, that his father is still very fond of meringues.”

Colonel Pinner heard that time, heard and brooded, looking Cyril up and down.

“What an esstrordinary thing!” said old Grandfather Pinner. “What an esstrordinary thing to come all this way here to tell me!”

And Cyril felt it was.

“Yes, I shall send Cyril the watch,” said Josephine.

“That would be very nice,” said Constantia. “I seem to remember last time he came there was some little trouble about the time.”

X

They were interrupted by Kate bursting through the door in her usual fashion, as though she had discovered some secret panel in the wall.

“Fried or boiled?” asked the bold voice.

Fried or boiled? Josephine and Constantia were quite bewildered for the moment. They could hardly take it in.

“Fried or boiled what, Kate?” asked Josephine, trying to begin to concentrate.

Kate gave a loud sniff. “Fish.”

“Well, why didn’t you say so immediately?” Josephine reproached her gently. “How could you expect us to understand, Kate? There are a great many things in this world you know, which are fried or boiled.” And after such a display of courage she said quite brightly to Constantia, “Which do you prefer, Con?”

“I think it might be nice to have it fried,” said Constantia. “On the other hand, of course, boiled fish is very nice. I think I prefer both equally well … Unless you … In that case —”

“I shall fry it,” said Kate, and she bounced back, leaving their door open and slamming the door of her kitchen.