Nava Atlas's Blog, page 23

October 13, 2022

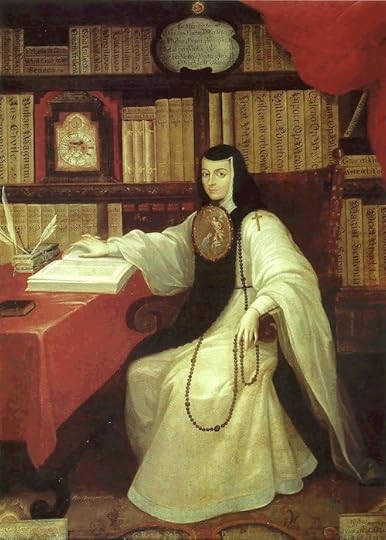

The Tenth Muse: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Juana Inés de Asbaje Ramírez de Santillana (November 1648 (?) – April 17, 1695), more familiarly known as Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz was a Mexican writer, poet, philosopher, composer, and Hieronymite nun.

Known as the “Tenth Muse” or as “The Phoenix of America” due to her formidable achievements in literature and scholarship, she is now revered as an early feminist.

Her writing is the subject of vibrant academic discourse on subjects as wide-ranging as women’s rights, environmentalism, colonialism, and education.

Early years

The exact date of Sor Juana’s birth is unknown; however, most accounts place her birth in November 1648, with her baptism not taking place until December 1651.

She was born out of wedlock to a Creole mother, Doña Isabel Ramírez de Santillana, and a Spanish father, Pedro Manuel de Asbaje. The family — her mother, grandparents, four sisters, and a brother, with her father mostly absent — lived in relative comfort on a hacienda in San Miguel Nepantla, near Mexico City.

Juana’s intellectual pursuits began at an early age. Some accounts claim that she learned to read at the age of three, when she hid in the hacienda chapel with her grandfather’s books from the adjoining library.

While stories of her reading and writing Latin by age four, and Greek by age eight, are probably exaggerated, there is no doubt that she was formidably intelligent.

At the age of sixteen, she was sent to live in Mexico City with her maternal aunt. She begged her mother to allow her to disguise herself as a boy, to gain entrance to Mexico City University which was then open only to men. Her mother refused, and Juana continued her studies in private.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Life at CourtJuana’s intelligence and beauty attracted the attention of the viceroy, Antonio Sebastián de Toledo, Marqués de Mancera, and the vicereine, Doña Leonor Carreto. In 1664 she was invited to court as a lady in waiting.

The system that she navigated during this time was complex. Mexico was a highly autocratic society, and the University, the Court, and the Church were the most powerful institutions in the country.

The Court represented the point of contact with Europe and European culture, while the Church controlled the dissemination of knowledge and culture. It was a man’s world, run by men for men, and this makes Sor Juana’s achievements, in the precarious feminine space that she made for herself between these institutions, even more astounding.

She was much admired for her literary accomplishments, especially after the Marqués “tested” her in a meeting of several prominent theologians, philosophers, and poets, all of whom were astonished by her intelligence, and she received several offers of marriage, all of which she declined.

In the biography Sor Juana, or The Traps of Faith (1982) Octavio Paz wrote of the impact this repressive patriarchal system had on Sor Juana’s writing:

“Her work tells us something, but to understand that something we must realize that it is utterance surrounded by silence: the silence of the things that cannot be said. The things she cannot say are determined by the invisible presence of her dread readers [those clergy who read and disagreed with her work] … An understanding of Sor Juana’s work must include an understanding of the prohibitions her work confronts …”

Religious life and secular writing

In 1667, with a “total disinclination to marriage” and a desire to have “no fixed occupation which might curtail my freedom to study,” Juana began her life as a nun, first in the austere convent of San José de las Carmelitas Descalzas and then, from 1669, in the more lenient Convent of Saint Paula of the Order of San Jerónimo.

Here the nuns had their own living quarters, complete with kitchens, bathrooms, and parlors, and often their own servants too. Sor Juana was allowed to study, correspond with other scholars, compose music that was both secular and religious, and hold an intellectual salon in her quarters each week.

In the convent, where she remained until her death, Sor Juana amassed one of the largest private libraries on the continent (around 4,000 volumes), together with an enviable collection of scientific and musical instruments.

She continued to be supported by powerful figures, and when the new viceroy, the Marqués de la Laguna, arrived in 1680, both he and his wife visited Sor Juana and supported the publication of her works in Spain. Under their patronage, she became the unofficial court poet and wrote plays, poetry, religious services, and for state festivals.

In her poetry, she employed the full range of forms and themes of the time, including sonnets, romances, and ballads, and drew on a vast range of Classical, mythological, religious, and philosophical sources of inspiration.

Her lyrics were moral and satirical as well as religious, and she also wrote dramatic, scholarly, and comedic works. Her output was prolific, and she wrote fluently in three languages: Spanish, Latin, and Nahuatl.

Many of Sor Juana’s secular poems were love poems, written in the first person as a woman narrator, and preoccupied not with the romance of love but the disillusionment, pain, and jealousy that accompany it.

She acknowledged feeling en dos partes dividida (divided into two parts), torn between reason and passion, devotion and sensuality.

There has been much debate over the nature of her friendship with the Marqués’s wife, María Luisa. The only real clues lie in Sor Juana’s poetry. Poems dedicated to Lisi or Lysis extol her virtues — which would have been traditional and expected for a court poet — but some also seem to allude to a romantic relationship, or at least the desire for one:

My divine Lysis:

do forgive my daring,

if so I address you,

unworthy though I am to be known as yours.”

. . . . . . . . .

Sor Juana on Academy of American Poets

. . . . . . . . .

Sor Juana achieved great fame in both Mexico and Spain, but with renown came disapproval from church officials. In the early 1680s, she broke with her Jesuit confessor, Antonio Núñez de Miranda, writing to him in 1681:

“The cause of your anger…has been none other than the ability that God has given me in creating these wretched verses without asking permission from Your Reverence.”

She also lost the protection of the Marqués and marquise de la Laguna after they departed for Spain in 1688.

She was always an outspoken supporter of women’s rights, in particular women’s rights to education, and often used her work to criticize the patriarchal system that rendered women all but invisible.

One of her best-known poems, “Hombres necios” (Foolish Men) fiercely accuses men of the same behavior that they criticize in women:

You foolish men who lay

the guilt on women,

not seeing you’re the cause

of the very thing you blame…

Their favor and disdain

you hold in equals state,

if they mistreat, you complain,

you mock if they treat you well…

Famously, Sor Juana paraphrased St. Teresa of Ávila in saying that “One can perfectly well philosophize while cooking supper.”

In response, several high-ranking Catholic officials, including the Archbishop of Mexico, publicly condemned her “waywardness.” In November 1690 the bishop of Puebla, Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz, published — without Sor Juana’s permission — her critique of a 40-year-old sermon by António Vieira, a Portuguese Jesuit preacher.

Fernández de Santa Cruz, using the female pseudonym Sister Filotea, added his own letter to this Carta Atenagórica, in which he criticized Sor Juana for not focusing on religious studies. While he conceded that some of her critical points were valid, he maintained that as a woman she should give up writing and devote herself to prayer instead.

Sor Juana responded in March 1691, in the famous Respuesta a Sor Filotea. In it, she defended the right of women to education and knowledge and traced the many obstacles she had faced throughout her life in her pursuit of learning, including her self-inflicted punishments for learning too slowly:

“It turned out that the hair grew quickly and I learned slowly. As a result, I cut off the hair in punishment for my head’s ignorance, for it didn’t seem right to me that a head so naked of knowledge should be dressed up with hair, for knowledge is a more desirable adornment.”

She stated that the study of “human arts and sciences” were necessary for an understanding of sacred theology and underscored her devotion to the pursuit of learning.

The pressure of censorship

Besieged by criticism and under great pressure from her confessor, Sor Juana stopped writing. Whether this was a process of forced abjuration, or whether she simply chose to stop writing to avoid further censure, is unclear.

There is a document of repentance dated March 1694, in which she agreed to undergo penance, and she supposedly voiced her regret at “having lived so long without religion in a religious community.”

Sor Juana’s library and collections were sold for alms, and she renewed her religious vows. She died in April 1695 while nursing her fellow sisters during a plague epidemic.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Legacy of Sor Juana Inés de la CruzAlthough Sor Juana’s work was largely ignored for centuries after her death, the 1980s saw new translations appear, inspired by a growing feminist movement, and a ground-breaking biography written by Octavio Paz.

Sor Juana is now considered an icon of Mexico and Mexican identity: her name was inscribed on the wall of honor in the Mexican Congress in 1995, her image has been printed on the 200 peso note, and her former cloister is a center for higher education.

It was her relationship with María Luisa which has fascinated filmmakers and writers the most. The 1999 novel Sor Juana’s Second Dream, by poet and scholar Alicia Gaspar de Alba, portrays the friendship as homoerotic, and became the basis for the play The Nun and the Countess by Odalys Nanín. It also inspired an opera, Juana, which premiered at the University of California Los Angeles.

More recently, interest in Sor Juana and María Luisa has been sparked by the 2016 television series Juana Inés, which was first produced in Mexico and is now available on Netflix.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online, and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Further reading

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Selected Works, edited by Julia Alvarez,translated by Edith Grossman (W.W. Norton, 2016)Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Feminist Reconstruction of Biography and Text,

by Teresa A. Yugar (Wipf & Stock, 2014)Sor Juana, or The Traps of Faith, by Octavio Paz

(no longer in print but available in English translation)

More about Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Explore the Life and Works of Sor Juana Britannica Rediscovering a Revolutionary (LA Times)

See more author biographies on this site.

The post The Tenth Muse: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 10, 2022

An excerpt from Rapture and Melancholy: The Diaries of Edna St. Vincent Millay

Rapture and Melancholy: The Diaries of Edna St. Vincent Millay, edited and annotated by Daniel Mark Epstein (Yale University Press, 2022) sheds an intimate light on an iconic American poet.

A revival of interest in the life and work of Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Edna St.Vincent Millay began in the early 2000s with the publications of What Lips My Lips Have Kissed (2001), also by Daniel Mark Epstein (2001), and Savage Beauty by Nancy Milford (2001) and

Millay received the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1923 for The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver, her fourth collection. She was the first woman (and only the second person) to win this award. Only thirty-one at the time, she was already one of America’s best-known poets, able to attract huge, enthusiastic crowds on her reading tours.

Enriching this treasure trove of diary entries, which spanning from Millay’s mid-teens to middle age, are Epstein’s chapter openers. His insights provide context for each section, and are helpful for filling in time gaps, as Millay wasn’t always a consistent diarist.

In the Foreword to Rapture and Melancholy, Holly Peppe, Millay’s literary executor, writes that until 1998, “when the diaries were transferred to the Library of Congress from Steepletop, Millay’s home in Austerlitz, New York, they have remained safely out of view, available only to credentialed scholars. With this book, Daniel has changed all that.”

Edna St. Vincent Millay’s life, from beginning to end, was unconventional and intense. She truly did burn her candle at both ends, as she wrote in her famous four-line poem, “First Fig.” After her untimely death in 1950, her legacy dimmed — many would argue, unfairly. Epstein has harnessed the inner world of a true original, helping to restore her to her rightful place in American letters.

. . . . . . . .

More about Edna St. Vincent Millay

. . . . . . . . .

From the publisher of Rapture and Melancholy, Yale University Press:

The English author Thomas Hardy proclaimed that America had two great attractions: the skyscraper, and the poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay. In these diaries the great American poet illuminates not only her literary genius, but her life’s a devoted daughter, sister, wife, and public heroine; and finally as a solitary, tragic figure.

This is the first publication of the diaries she kept from adolescence until middle age, between 1907 and 1949, focused on her most productive yers. Who was the girl who wrote “Renascence,” that marvel of early twentieth-century poetry? What trauma or spiritual journey inspired the poem?

And after such celebrity why did she vanish into near seclusion after 1940? These questions hover over the life and work, and trouble biographers and readers alike.

Intimate, eloquent, these confessions and keen observations provide the key to understanding Millay’s journey from small-town obscurity to world fame, and the tragedy of her demise.

. . . . . . . .

Rapture and Melancholy

is available wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . .

… by Daniel Mark Epstein: To what does Edna St. Vincent Millay owe the honor of having her diaries published and read in 2022, more than seventy years after her death? Her status as a poet and playwright of the first magnitude, secure until the 1940s, is now a subject of debate.

Her poems remain in print and her play Aria da Capo is occasionally revived; but as of this writing her work is rarely included in textbooks or college syllabi.

The reasons for this are largely political, or in any case extra-literary. The poet had the fortune and misfortune to become a legend in her own time, what we now quaintly call “a cultural icon.”

Her binge drinking and promiscuity were notorious even in the 1920s when such behavior was commonplace. She became the bad girl of American letters who published her modern escapades in verses that demonstrated mastery of the classic forms and meters. No one had seen anything like it.

Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, who had enough Latin between them to recognize her achievement, ostentatiously ignored the upstart whose ballads and sonnets made her rich. She needed no one’s help, and what she was writing did not fit the modernist’s profile of “free verse.” Her success was a reproach to modernism.

Meanwhile she behaved as badly as Byron and Baudelaire, Sappho in a cloche hat, chain-smoking, sipping gin, and bed-hopping … The poetry was transgressive and subversive. Compared with the unimpeachable verse of Elizabeth Bishop, Millay’s poetry is still shocking.

… The diaries — which the mature writer never intended for publication — are unfiltered. From beginning to end she writes without restraint or inhibition, recording thoughts, dreams, emotions, and impressions meant only for her own clarification and reflection.

In these pages, we hear Millay’s intimate voice, the woman speaking to herself about her most private and urgent concerns.

About Daniel Mark Epstein: Millay biographer Daniel Mark Epstein is a poet and dramatist, the author of books about Abraham Lincoln, Walt Whitman, and Bob Dylan. He is a recipient of awards from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Find him at DanielMarkEpstein.com.

An excerpt from Rapture and Melancholy

July 20, 1910 Wednesday Night

Journal of a Little Girl Grown-Up

I’m tired of being grown-up! Tired of dresses that kick around my feet, tired of high-heeled shoes; tired of conventions and proprieties; tired, tired and sick of hairpins! I want to be a little girl again.

It seems to me, looking back over my jump-rope and hop-scotch days, that I never played half hard enough, always came in a little too soon, lay abed a little too long. If I had only known, and had climbed enough trees and made enough mud-pies to last me through the awful days when I should want to and couldn’t!

And the awfullest thing about it is that I haven’t forgotten how. It wouldn’t be so bad if I just couldn’t remember; but to know how so well—to want to so bad—and not to be able to! It seems to me I can remember everything I ever did, every place I was ever in.

My mind is a labyrinthian picture-gallery in which every paint-ing is some scene from my life—vivid and distinct, even in its most trivial details. It takes but the tiniest thing, the faintest sound or scent, often-times imagination—to bring such a scene before my eyes. There is a little spicy-smelling yellow flower growing in clusters on a bush, in old-fashioned gardens I think they call it “clove” or a “flowering currant.”

The smell of it inevitably never fails to take me back into a little playhouse I made once under such a bush, just this side of the church-yard fence. It is a hot summer afternoon. The air is drowsy with the sweetness of the tiny trumpet-shaped flowers above my head and, save for the monotonous droning of many bees, there is no sound anywhere.

I am painstakingly trimming a rhubarb leaf hat with white-clover and buttercups with which my lap is filled. Beside me are two long, slender white wands from which I have been peeling the bark for ribbons, with primitive implements of sharp teeth and nails.

I can taste again the sweetness of the smooth round stick in my mouth. I see again the moist, delicate green of the bark’s living. And into my nostrils I breathe the hot spicy fragrance until my soul is steeped in it.

Then on and on into picture after picture after picture, through a meadow where, at every step, I had to pick the violets to clear a place for my feet; over the short stubble of a wide level field to the place where a friendly grapevine climbed a tree and, with its own weight bent the branches

to the ground, bringing forth grapes and apples into easy reach; up the side of a woody hill and [wandered] a winding path to a secret spot where fox berries grew bigger, sweeter, and more plentifully than anywhere else in the world.

Hundreds of places, each one as dear as these each one so distinct that I know I could find now if it is still there. If I could just go back like na little girl and revisit each scene alone. Who would there be to say “Go away, you can’t come here, for you are a little girl no longer”?

. . . . . . . .

See also: 12 Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay

The post An excerpt from Rapture and Melancholy: The Diaries of Edna St. Vincent Millay appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 2, 2022

In Search of Virginia Woolf’s Lighthouse, Godrevy Light

What is it that makes us long to see what the writers we love once saw? To stand in their footsteps? Do we imagine that some fairy dust will fall from nearby trees or rise from abandoned floorboards to bring us the wisdom or the art that flowed from their fingers to their manuscripts, whether through pens or pencils, typewriter keys, or pixels?

That’s what was on my mind on a visit to Cornwall, England, when I was determined to get to Godrevy Light, the lighthouse that inspired Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse.

Godrevy Light

Like the characters in Part I, “The Window,” I found getting to the lighthouse difficult. My spouse and I, Americans who drive as little as possible, don’t want to drive in the UK, where we would certainly be disoriented by the different positioning of steering wheels and road lanes.

Trains and buses get us to most of the places we want to go, but I could not find a way to get out to Godrevy Point, the nearest land to the lighthouse. Bus service is so infrequent that I (the travel agent in our household) could find no way to go out and return the same day.

I considered hiring a taxi but was dismayed to realize that while the lighthouse was only three miles from shore at Godrevy Point, the roads from any settlement served by a bus or a train were winding and indirect. The more I investigated, the more travel to the lighthouse seemed time-consuming and expensive.

The Godrevy Lighthouse stands on a small rocky island, inhabited today only by birds and seals. You can judge its beauty when I tell you that a photo of the lighthouse was the winner of the 2021 South West Coast Path photo competition. (For context, the South West Coast Path provides the gorgeous scenery for TV shows such as Poldark and Broadchurch.)

The white octagonal-shaped tower was built in 1859, after a steamer wrecked on the rocky reef known as the Stones and sank. Everyone on board drowned. After the lighthouse was built three keepers alternated month-long duties to staff the light.

. . . . . . . . . .

To the Lighthouse (1927)

. . . . . . . . . .

At the beginning of To the Lighthouse, Mrs. Ramsay prepares for the proposed visit by knitting a stocking for the Lighthouse keeper’s little boy. She also looks around for “old magazines, and some tobacco, indeed whatever she could find lying about … to give those poor fellows who must be bored to death sitting all day with nothing to do ….”

To explain why she wants to deliver these things to the Lighthouse, she asks her daughters, “How would you like to be shut up for a whole month at a time, and possibly more in stormy weather, upon a rock the size of a tennis lawn? … and to have no letters or newspapers, and … to see the same dreary waves breaking week after week?”

In 1934, some seven years after the publication of To the Lighthouse (but decades after the time in which it was set), the Godrevy Lighthouse became automatic. The keepers who had concerned Mrs. Ramsay were relieved of their dreary and boring duties as well as their livelihood. (For another perspective on lighthouse keepers see Jeanette Winterson’s Lighthousekeeping.)

. . . . . . . . . .

Godrevey Lighthouse

This photo and at top, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . .

To the Lighthouse is regarded as Woolf’s most autobiographical novel. It describes two days, ten years apart, in the lives of the Ramsay family. While the story is set in the Scottish Hebrides, Woolf says in her diary that Mr. and Mrs. Ramsay are closely modeled on Woolf’s parents, Leslie and Julia Stephen, and that the events in the book recall the family’s summers in St. Ives, Cornwall.

The book had therapeutic value for Woolf—her mother, like Mrs. Ramsay, died suddenly. Woolf was thirteen at the time of her mother’s death, and she says she was “obsessed” with her mother until she wrote To the Lighthouse. Afterward she wondered why it was that once she had described her mother that “my vision of her and my feeling for her” became “so much dimmer and weaker?”

The phenomenon of something becoming “dimmer and weaker” happens in the novel as well. In Part I, the Lighthouse is the object of six-year-old James’s longing and the intended recipient of Mrs. Ramsay’s charitable efforts.

It provides Mr. Ramsay with the power to disappoint (and thus to win his son’s hatred). It gives the Ramsay’s houseguest, Charles Tansley, (a man who whispers in painter Lily Briscoe’s ear, “Women can’t paint, women can’t write”) the opportunity to disparage dreams.

When James makes it to the Lighthouse in Part III, he is disappointed. “The Lighthouse was then [when he was six] a silvery, misty-looking tower with a yellow eye that opened suddenly and softly in the evening.” When he finally arrives, ten years later, he sees “the whitewashed rocks; the tower, stark and straight,” and he thinks, “So that was the Lighthouse, was it?”

He resolves the contradiction in the next paragraph. “The other was also the Lighthouse. For nothing was simply one thing.”

And that, I think, is how Woolf frees herself of her obsession with her mother. Like the Lighthouse, Mrs. Ramsay dominates Part I. She is the close third-person narrator through which we see much of the section, and when she is not the narrator, she is the object of other people’s narrative thoughts.

Everyone in Part I is obsessed with Mrs. Ramsay: her beauty, her kindness, her ability to manage a household of children and guests and servants, and her skills as a matchmaker. She delights in bringing people together and through the force of her desire effects a marriage proposal. By simply looking at young Paul Rayley, Mrs. Ramsay makes him understand that she wants him to propose marriage to Mindy Doyle as she sends the two of them out for a walk together.

Lily Briscoe, determined to remain unmarried, resents Mrs. Ramsay’s power, and yet she longs to bask in her light.

Yes, her light.

For Mrs. Ramsay is the Lighthouse. See how she is described here, for example, half turning “to pour erect into the air a rain of energy, a column of spray, … as if all her energies were being fused into force, burning and illuminating…” Later, her husband thinks, “it hurt him that she should look so distant, and he could not reach her” (just as they cannot reach the distant lighthouse).

Mrs. Ramsay herself thinks she would like to go with some of the others as they set out on a walk. “Of course it was impossible for her to go with them. But she would have liked to go, had it not been for the other thing.” The “other thing” is never named, and I would say Mrs. Ramsay cannot go with them because she is the Lighthouse, the point that guides the others in their travels.

She is a manipulative and powerful woman who embodies beauty and warmth. She epitomizes maternal love and at the same time, a cold, unreachable distance. Like the Lighthouse in the eyes of sixteen-year-old James, she is not simply one thing.

. . . . . . . . . .

Virginia Woolf

. . . . . . . . . .

I couldn’t figure out how we would get to the Godrevy Light. I wasn’t sure we would even be able to see the lighthouse from St. Ives (as opposed to the Godrevy Headlands a few miles away), and so when our bus rounded a curve and began its steep descent into the village and I caught a glimpse of the tower, surprisingly close, my hand flew to my chest.

My heart really did give a little leap. I was so thrilled to see the light that had inspired one of my favorite novels that when the bus arrived at the outskirts of St. Ives (the roads being too narrow for it to continue into the town), I scrambled off eagerly, realizing only once we were walking in the village that I had left my hat on my seat.

It was a hat I had carried with me on many trips, one of the few I had ever worn that I thought flattered my face, a crushable thing that opened out to a wide-brimmed sunhat to shade my pale complexion. Yet unlike other losses, I was not dismayed to have forgotten it. It had served me well for many years, and I was certain it could be replaced quite easily. I was excited to be in St. Ives and within sight of the lighthouse.

Crowded beachside restaurants offered views of the gleaming structure on its stony perch. I imagined that we would eventually have lunch at one of those tables, though I suspected the menus would be heavy on fried foods and not to my taste. As we navigated the winding streets and alleys of St. Ives, buildings blocked our view of the bay.

Nonetheless, we made our way to the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden. Hepworth was a contemporary of Woolf’s, about twenty years younger, and like Woolf, brought a modernist sensibility to her creative work. Both women were inspired by Cornwall and St. Ives—for Hepworth, as for so many other visual artists, it was the quality of the light reflected off water, rugged land, and crushed shells.

Woolf saw that light as well, “wave after wave shedding again and again smoothly a film of mother-of-pearl,” and she also saw that other light from across the waves, “first two quick strokes and then one long steady stroke.” In other words, the light of the Lighthouse.

Hepworth’s stone constructions were partially inspired by Cornwall’s craggy landscape and its neolithic quoits, tors, and circles. From the sculpture garden, we climbed up and then down steep, cobbled paths to the Tate St. Ives and entered its domed portico. Hungry by then, we headed up to the top-floor cafe to find an outdoor table on the terrace where my heart leapt once again when confronted with a perfect view of (drumroll, please) the Lighthouse!

I gazed across the bay to that sober sentinel, white against the gray-blue sky and sea, and thought about Mrs. Ramsay as I enjoyed my parsnip soup garnished with roasted onion jam. There had to be a way to get to the island, and later, as we walked along the bustling harbor promenade, the way appeared. Posters on the seawall offered seal- and bird-watching trips to Godrevy Island. I booked passage for the two of us the day after the next (our last in Cornwall).

Everything was working out perfectly, and when the bus arrived to take us back to Penzance, I was delighted to find my old friend, my hat, sitting on a ledge next to the driver.

Just as in To the Lighthouse, the day of the planned boat trip dawned stormily, and a message on my phone told me our cruise had been canceled and my money refunded. Just as in the novel, the weather would interfere with our effort to reach the Lighthouse.

Perhaps in ten years, I will return to Cornwall to visit the lighthouse.

Or perhaps it is enough that, like Lily Briscoe, the painter who concludes Woolf’s book and who never goes to the Lighthouse, I have had my vision: I have seen the Lighthouse not only as it appears off the coast of St. Ives, but as Woolf herself portrayed it.

The Lighthouse is more than one thing, after all. It is the thing that inspires and the thing that stands guard. It is the thing that comforts and the thing that cannot be reached. Like my hat, perhaps, it is the thing that is lost and the thing that is found.

Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.

The post In Search of Virginia Woolf’s Lighthouse, Godrevy Light appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 12, 2022

Lolly Willowes; or The Loving Huntsman by Sylvia Townsend Warner

Lolly Willowes; or The Loving Huntsman was the first novel by modernist author Sylvia Townsend Warner. Published in 1926, it’s now considered an early feminist classic.

Considered comedy of manners, this novel is steeped in social satire. This collection of reviews was gathered in High Collars & Monocles: 1920s Novels by British Female Couples by Francis Booth, © 2020. Reprinted by Permission.

Following is a synopsis and two reviews from 1926, when the book was originally published. A more recent look back at Lolly Willows in the Guardian lauds it as a social satire and “an elegantly enchanting tale that transcends its era.”

Lolly Willowes: a brief synopsisThe Scotsman, February 18, 1926, provided a synopsis in its coverage of Lolly Willowes, or The Loving Huntsman by Sylvia Townsend Warner (London: Chatto & Windus)

There is a piquant charm in this quiet chronicle of the life of an old spinster who makes a compact with the Devil, throws her relations to the winds, and asserts her right to stay out all night in the hills.

If it be objected that the patient Aunt Lolly whose submissive girlhood, submissive sisterhood, and submissive aunthood are so delicately and with fine persistence pictured by the writer could never develop into such a “monstrosity” as a witch, then the objector is referred to the exquisite old lady herself, who, it is certain, will charm doubt into conviction.

For does she not explain everything when she tells the “loving huntsman” of Great Mop village that “one doesn’t become a witch to run round being harmful, or to run round being helpful either, a district visitor on a broomstick?

It’s to escape all that – to have a life of one’s own, not an existence doled out to you by others, charitable refuse of their thoughts, so many ounces of stale bread of life a day, the workhouse dietary so scientifically calculated to support life.”

Thus is it. Aunt Lolly at last satisfies her inmost cravings to be herself: and may all overweening nieces and nephews, brothers and sisters-in-law, take warning from this tale of an old spinster who turns. The writer, who has already made herself known by an appealing book of verse, must be congratulated for the delicious fancy and charming irony of the present prose study. It is a book to be read again with increased pleasure.

. . . . . . . . .

Sylvia Townsend Warner

. . . . . . . . .

From the Times Literary Supplement (London), February 4, 1926: Miss Sylvia Townsend Warner gives us in Lolly Willowes not only a first novel of remarkable accomplishment but an object-lesson in the proper way of bringing Satan into modern fiction.

She wastes no time in cold philosophical argument, in pumping up horror before and after the event, in giving away the surprise and then making it seem preposterous; instead she prepares the ground with extraordinary subtlety.

Laura Willowes is the unmarried daughter of one, sister of another, and aunt of a succeeding generation of a respectable, solid, acquisitive, comfortable middle-class family. Her youth was spent at Lady Place, a house near Yeovil where her father kept the accumulated family furniture and owned the brewery.

And when her father died she was unquestioningly taken in by her brother Henry and his wife Caroline to live with them, as the children’s Aunt Lolly, at the house in Apsley Terrace and in the lodgings of the summer holidays.

Up to the end of part one nobody could anticipate the development. Laura’s life, all the life of all Aunt Lollys, is set down for us in sentences of deft observation and concealed irony. Miss Warner’s economy of phrase is admirable.

“By the time the Willowes family met at breakfast all this activity had disappeared like the tide from the smooth, garnished beach. For the rest of the day it functioned unnoticed. Bells were answered, meals were served, all that appeared was completion.

Yet unseen and underground the preparation and demolition of every day went on, like the inward persistent working of a heart and entrails. Sometimes a crash, a banging door, a voice raised, would rend the veil of impersonality. And sometimes a sound of running water at unusual hours and a faint steaming hiss in the upper parts of the house betokened that one of the servants was having a bath.”

Nobody would suspect the emergence of a cloven hoof from this quiet realism. Into seventy-three pages Miss Warner compasses twenty years of Laura’s life with Henry and Caroline, she and they and their offspring and their life etched with fine precision.

If one is afraid of what is coming, the fear is that nothing is to come but one more study – though an unusually artistic one – of a frustrated woman’s life and death. There have been hints, it is true, but too deep for the un-intuitive. At the age of forty-seven, however, the war being over, Laura is more than usually oppressed by the day-dreams that customarily invaded her during autumn in London.

Something is waiting for her, she must find a clue, but the clue eludes her. An impulse seizes her in a greengrocer’s shop, it leads to the Chilterns, she buys a map and guide, and calmly startles a family dinner-party by announcing that she is going to Great Mop to live in a cottage. There is a trap for the unwary here, too.

The prophetic will exclaim: “Ah, yes, the country, nice old landladies, village worthies, landscape and echoes of Henry Ryecroft;” and they will be most deservedly confounded, for Miss Warner gives them all these things, and the real surprise on top of them. The crisis comes when nephew Titus comes to Great Mop two, to write a book on Fuseli.

In depicting Laura’s dumb anguish at this invasion of her privacy and desecration of her mysterious love for her chosen country, a new note of passion suddenly breaks out. The whole family seems to be advancing upon her once again, and, alone in a solitary field, she invokes the woods for help. The answer is prompt, but we cannot bring ourselves to spoil the delightful surprise prepared for the reader and for Laura on the latter’s return to tea.

It must suffice to say that Aunt Lolly realizes at length to what all the omens of her life have pointed. She is – we are compelled to divulge it – a witch, a modern witch, one of thousands. Miss Warner works out her idea, witches’ Sabbath, Satan and all, so delicately and tactfully that it never becomes incongruous.

Titus is bewitched into the arms of a fiancée, and Laura, having passionately breathed to her master the hidden truth about witches, remains at Great Mop among her companions. It is a charming story, beautifully told, spare in outline but emotionally rich, on which we congratulate the author.

. . . . . . . . . .

High Collars & Monocles by Francis Booth

is available on Amazon US and Amazon UK

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review Edwin Clark, New York Times, February 7, 1926: It is on rare and infrequent occasions that such perfected and deftly fascinating fiction as Lolly Willowes swims within the reviewer’s ken.

David Garnett, who is remembered as something of a master of wit and shrewd observation, has remarked that this is one of the year’s witty books. However, this novel needs no such introduction. It is the cameo-like realization of the life of a quaint and subtly attractive maiden lady. It recalls the two exquisite novels of Elinor Wylie, but Lolly Willowes is closer to the present.

Behind the story of Lolly, but at least once removed, is the inevitable theme of the old order changing. The effect upon her life is less pronounced than usual because of her passive temperament. The Willowes are an old family of landed gentry. Lolly is heir to much accumulated tradition.

Her father is a brewer, her mother is a semi-invalid. She is the youngest of the three children. Hence, she grows up in a family where the males of the house were always expected to look after her. In turn, she compared all other men in terms of her father and brothers. With complacency she looked out upon the world from their country seat, Lady Place, in Somerset. It was satisfying to her. . .

The sly and almost subdued comedy of this novel is a strong suggestion of the quality of Jane Austen. The handling of sentiment, family life, and much feminine observation has the adroit fitness of the divine Jane.

In the handling of the narrative, however, a different method is employed; the straightforward method of the comedy of manners could not capture the inner life of Lolly, and fill so minutely the picture of this involved family life, for all its surface commonplaceness.

Beginning in the later Victorian age of gentility, the story is woven into the present restless age, without neglecting or overemphasizing the war; the technical skill and compression is of a high order.

At forty-seven, Lolly realizes that she has had almost no life of her own. Rebellion stirs in her. To the horror of her brothers, to the surprise of their children – now grown-up – she insists upon escaping from them. This whim of hers to leave them and live in the village of Great Mop – population 227 and twelve miles from anywhere – is embarrassing because Henry has invested her money in an enterprise that just at the moment is in decline. Lolly accepts a loss and departs.

Once at Great Mop she begins to recapture the serenity that had made her inner life bright at Lady Place. . . .

The family hope for her return. They visit her. She has horror at the thought of returning to Apsley Terrace, London. The idea preys upon her mind and finds outlet in fantasy. Thus, James’s son, now graduated from Oxford, comes to stay with her at Great Mop. Though she thought herself very fond of him, he greatly distresses her. She starts a sprightly flirtation with the Prince of Darkness, in an effort to find that fellowship that her life has lacked. Finally, she is free of her relatives. She could at last do what she liked. . .

In the limitations of its genre, Lolly Willowes is an exquisite fantasy of wit. Also, in its mixture of comedy of manners and dark romanticism, there is a viable essence that is enchanting. Lolly, indeed, going her kind, lonely way, is a character that ingratiatingly sets herself in memory.

Doubtless, the Willowes, with their traditions and sane conservativeness, will not be forgotten. But, in the last analysis, it is Lolly – who might be another Emily Dickinson, had she only had the medium of expression – who captivates our fancy. Her secret life is ours in the artless words of her historian.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Lolly Willowes Full text at Wikisource The 100 Best Novels: No. 52: Lolly Willowes Reader discussion on Goodreads. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth-Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938; High Collars & Monocles: 1920s Novels by British Female Couples.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young Adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

The post Lolly Willowes; or The Loving Huntsman by Sylvia Townsend Warner appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 2, 2022

10 Fascinating Facts About Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, French Portraitist

Susanne Dunlap, author of the historical novel The Portraitist: A Novel of Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (She Writes Press, 2022) presents ten fascinating facts about one of the two most important French female artists of the period before, during, and after the French Revolution.

About The Portraitist:

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard is ready to draw the line between art and politics in The Portraitist. Award-winning author Susanne Dunlap paints a historical retelling of real-life Adélaïe Labille-Guiard, a female portraitist and painter, and her earnest battle to win recognition as an artist in 18th-century Paris amidst the French Revolution.

Paris, 1774. After her separation from her abusive husband, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard is at last free to pursue her dream of becoming the premier woman portraitist in Paris. Free, that is, until she discovers at her first public exhibition that another woman artist is poised to claim that role — and she has more training and better connections in the tightly controlled art world.

To have a chance of competing, Adélaïde must first improve her skills in oil painting. But her love affair with her young teacher gives rise to suspicions that he touches up her work, and her decision to make much-needed money by executing erotic pastels threatens to create as many problems as it solves.

As her rival gains lucrative portrait commissions and an appointment as portraitist to Queen Marie Antoinette, Adélaïde continues to struggle, until at last she earns a royal appointment of her own, and, in 1789, receives a massive commission from a member of the royal family.

But the timing couldn’t be worse. Adélaïde’s world is turned upside down by political chaos and revolution. With danger around every corner of her beloved Paris, she must find a way to survive and adjust to the new order, starting all over again to carve out a life and a career—and stay alive in the process.

The Portraitist is based on the true story of one woman artist’s fight to take her rightful place in a man’s world — and the decisions she makes that lead her ultimately to the kind of fulfillment she never expected.

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard began her career in a world where royal patronage was the height of accomplishment and ended it after a bloody revolution and a new political system that set women’s rights and autonomy back about a century.

Liberté, égalité, fraternité—brotherhood—men ended up with all the privileges in the Napoleonic code. Worth noting — there’s no actual French word for sisterhood.

Nonetheless, Labille-Guiard was remarkable for what she did achieve, and her artworks can be found in museums and private collections all over the world. So why is she so little known?

Fascinating Facts About Adélaïde Labille-GuiardShe didn’t come from an artistic family. Adélaïde’s principal rival, Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun, was taught to draw and paint by her artist father, her godfather was the artist Gabriel Doyen, and she was surrounded by the best artists of the day.

By contrast, almost nothing is known about Adélaïde’s early training. Her father was a modiste who owned a fashion boutique in Paris called À la Toilette. Interesting tidbit: before Madame du Barry became Louis XV’s official mistress she was a shop girl by the name of Jeanne Bécu in that boutique.

Adélaïde was one of two surviving children of eight; her mother died when she was 17. It’s unlikely that her sickly mother took the time to teach her how to draw. And there’s little information about her schooling either.

It’s possible that—like her rival Elisabeth—she was sent to a convent school for some of her education. But that’s pure conjecture. In any case, she somehow acquired the education she needed, although one biographer laments that she wasn’t educated enough.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Portraitist: A Novel of Adélaïde Labille-Guiard

is available wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . . . .

She married at the age of 19 (and was legally separated 8 years later). Divorce was illegal in Catholic Ancien Régime France. Adélaïde couldn’t get a divorce until after the laws changed in 1793, twelve years later.

She took up with François-André Vincent, a history painter, after becoming his student in 1776. Although her divorce came through soon after the Revolution, they didn’t marry until 1800.

There’s no evidence today that explains why she and André didn’t marry as soon as they were able. But it could have something to do with the fact that once they married, she relinquished the name of Labille-Guiard—the name associated with her artistic career—and became known as Madame Vincent.

Adélaïde started out painting miniatures. Painting miniatures was seen as a genteel occupation for girls and women in the 18th century, and they were generally painted with watercolors—inexpensive, easily cleaned up. But Adélaïde clearly didn’t approach the practice of art as a pretty pastime.

We know that she studied the painting of miniature watercolors with François-Élie Vincent, a member of the Académie Royale, who just happened to be the father of Adélaïde’s eventual lover and husband. She also studied pastels with Maurice Quentin de la Tour, the most famous pastellist of the time.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Self Portrait, watercolor on ivory, 1774

. . . . . . . . . . .

Access to training in the technique and art of painting was a significant hurdle for women. The Louvre housed the École des Beaux Arts, but those classes were closed to women, so the only recourse was individual tutelage.

Without an artist family member or connections, Adélaïde must have been determined and passionate to have broken into the insular, sexist field.

Adélaïde and her rival dogged each other’s steps throughout their careers. Obviously, the opportunities for top-notch women artists were extremely limited. Hardly surprising, then, that these two would find each other competing for the same or similar achievements.

The parallels are remarkable nonetheless: They both exhibited for the first time in the same salon, they both had royal patronage (although Elisabeth had the prize of being Marie Antoinette’s official portraitist), they were both elected to the Académie Royale in the same year and exhibited in the same salons every other year until 1789.

After that, Elisabeth was off painting in the courts of Europe, having fled and been declared an exile and enemy of the Republic because of her ties to the royal family.

Unlike her rival, Adélaïde became a highly respected teacher and was much in demand. Her studio before the Revolution consisted of nine talented women, her nine “muses,” she called them. They were a consistent source of income for her, and one of them—Marie-Gabrielle Capet—not only became a close friend, but Adélaïde and André adopted her after the Revolution so she could inherit their estates.

Elisabeth didn’t like teaching.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Marie Gabrielle Capet, Atelier of Madame Vincent,

Oil on Canvas, 1808

. . . . . . . . . . .

After years of trying, Adélaïde became the first woman to be awarded a studio and accommodations in the Louvre. The Louvre was neither a museum nor a royal residence at that time. It was instead a center of art and creativity, and free lodging was given to members of the Académie who requested it. That is, if they were men.

Adélaïde struggled financially and lobbied for those free accommodations before, during, and after the Revolution. Her first attempt in 1787 was thwarted by the conservative Comte d’Angiviller, controller of all things artistic in France, who claimed that allowing women to come into the Louvre to study would be a corrupting influence.

She finally succeeded in 1795 and became more famous as a teacher than an artist.

Adélaïde was never paid for her biggest commission: a massive painting for the Comte de Provence. Louis XVI’s younger brother hired Adélaïde to paint a 17 x 19-foot picture to hang in the École Militaire.

Since payment always came upon completion, Adélaïde had to fork out her own funds to purchase the expensive materials—the finest canvas from the Low Countries to be stitched together for such a huge painting, masses of pigments and brushes, scaffolding, gesso, and so on.

Mesdames (the king’s aunts, who were Adélaïde’s royal patrons) secured studio space for her in the disused Bibliothèque du Roi, since her own studio was nowhere large enough to accommodate a project of that size.

She was supposed to get thirty-thousand Livres, or about $18,000 in today’s currency—bearing in mind that this amount had a great deal more purchasing power then that it has today (the average laborer earned about $30 a year).

However, instead of a big payday, Adélaïde ended by losing 8,000 livres of her own money, about $5,000. The ultimate irony is that all that’s left of this mammoth painting is an oil sketch.

Adélaïde painted a portrait of Maximilien Robespierre. Before the dark days of the Terror, Adélaïde made an effort to prove her loyalty to the Republic—despite her history of royal patronage—by painting portraits of all the delegates to the national convention, free. At the time, that included Robespierre.

His portrait has been lost along with all the others, which were destroyed during the worst excesses of the Terror. In fact, many of Adélaïde’s paintings and pastels met the same fate, which is one reason why there are so many fewer works by her in museums today than by Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard,

Self Portrait with Two Students, Oil on Canvas, 1785

. . . . . . . . . . .

When André Vincent died, the paintings in his possession by his late wife were sold for mere pennies. Adélaïde died in 1803 at the age of 54, cause unknown, but she had likely been ill for a while. I have been unable to discover the location of her grave. However, her history-painter husband is interred in Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, and his works sold for many thousands of Livres when he died.

Adélaïde’s work was underappreciated until late in the twentieth century. Her most famous painting, the self-portrait with her students Marie Gabrielle Capet and Marie Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemonde, is on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. A detail of this work is on the cover of The Portraitist.

In the Catalogue Raisonné of her output by Anne Marie Passé, of the 143 paintings identified, over half are lost (labeled “unknown location”). Compare that to her rival’s output of somewhere around 600 works, and you can easily see why Adélaïde Labille-Guiard remains relatively unknown.

The Portraitist is my attempt to change that!

Susanne Dunlap is the author of twelve works of historical fiction for adults and teens, as well as an Author Accelerator Certified Book Coach. Her love of historical fiction arose partly from her studies in music history at Yale University (PhD, 1999), partly from her lifelong interest in women in the arts as a pianist and non-profit performing arts executive.

Her novel The Paris Affair won first place in its category in the CIBA Dante Rossetti awards for Young Adult Fiction. The Musician’s Daughter was a Junior Library Guild Selection and a Bank Street Children’s Book of the Year, and was nominated for the Utah Book Award and the Missouri Gateway Reader’s Prize. In the Shadow of the Lamp was an Eliot Rosewater Indiana High School Book Award nominee. Susanne earned her BA and an MA (musicology) from Smith College, and lives in Biddeford, ME, with her little dog Betty. You can find her at Susan-Dunlap.com.

See our Other Rad Voices category to explore more amazing women outside the literary realm.

The post 10 Fascinating Facts About Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, French Portraitist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 30, 2022

“Rosefrail and Fair” — Lucia Joyce, Dancer Daughter of James Joyce

This introduction to the life of Lucia Joyce, a professional dancer and the talented, troubled daughter of James Joyce and Nora Barnacle is excerpted from Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

Sylvia Beach, publisher of Ulysses, wrote in Shakespeare and Company about James Joyce’s family:

“I was very fond of them all: Giorgio, with his gruffness, hiding or trying to hide his feelings; Lucia, the humorous one – neither of them happy in the strange circumstances in which they grow up; and Nora, the wife and mother, who scolded them all, including her husband, for their shiftlessness.”

People didn’t normally think of Lucia as the humorous one; she was generally seen as being rather tragic, and later in life was in a mental institution for many years. In her contribution to Robert McAlmon’s Being Geniuses Together, Kay Boyle talks tenderly about how the fragile Lucia came to see her one day in 1928:

“Whether it had been suggested to her that she come, or whether she had come of her own accord, I did not know. But as she sat in the sunlight that came hot through the plate-glass window, I felt her tragically reaching, seeking for what could probably never be found and for a fearful moment I believed I was looking at my own reflection in a glass.

She was like the high, perishable, wishful tendril of a vine moving blindly up a wall, and the vine from which she sought escape was rooted in a territory that had for her no recognisable name. I thought of Joyce’s poem to his blue-veined daughter, and there in her delicate wrists I could see the veins, so vulnerable under the silky, transparent skin.

She was then (as perhaps I too was then, and as perhaps all daughters are until they cease being merely daughters) precariously only half a person, and the other half she sought for in panic first in one direction and then in another, not knowing in whose mind or flesh or in what alien country it might live.”

The poem that Boyle refers to comes from the small selection of Joyce’s early poems, Pomes Penyeach, which was published with Lucia’s illustrations and facsimiles of Joyce’s handwritten texts by Jack Kahane’s Obelisk Press in 1932, though Sylvia Beach had published a regular edition in 1927.

Harry and Caresse Crosby of the Black Sun Press had originally suggested the idea of a deluxe, illustrated, facsimile, limited edition to Joyce; he was happy for Lucia’s work to be published, happy for her to have something, to be something in her own right. Not that it was anything very much in her own right to illustrate her father’s work; her drawings would never otherwise have been published, and she would have been in no doubt about that.

Still, Joyce made sure she got a third of the royalties. Only twenty-five copies of the deluxe edition were printed, on lustrous Japanese nacre, with Lucia’s illuminated capitals delicately colored; all were signed by Joyce.

The British Library has number 25; it’s very beautiful. Number 3 was auctioned in 2015 with an estimate of $40,000 to $60,000 but failed to sell. This is the poem about Lucia that Kay Boyle referred to:

A Flower Given to My Daughter

Frail the white rose and frail are

Her hands that gave

Whose soul is sere and paler

Than time’s wan wave.

Rosefrail and fair – yet frailest

A wonder wild

In gentle eyes thou veilest,

My blueveined child.

Boyle knew Lucia on and off through her life; many years later, after Lucia’s death in 1983, Boyle had an exchange of letters about her with Joyce’s first major biographer, Richard Ellman; she told him how she and Samuel Beckett had spent an evening together sometime in 1932 when he tried to convince her that unhappiness and madness were not the same thing – Lucia was unhappy but that was not all there was to it. Boyle wrote to Ellman:

“One day, when we chance to meet again, I want to tell you of my first meeting with Samuel Beckett. It was in the sad time of Lucia’s first crisis, the beginning of it all, and Sam and I talked together at a crowded party in Walter Lowenfels’ apartment in Paris.

We both remember every word of that talk of over fifty years ago, talk which lasted from nine in the evening until two o’clock the next morning, during which he convinced me that there is such a thing as madness, and that love or understanding or any emotional response to that condition is not the cure.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

[image error]

Everybody I Can Think of Ever is available on

Amazon US & Amazon UK

. . . . . . . . . .

Soon after Beckett had arrived in Paris in November 1928 to take up his teaching post at the École Normale, he first met Lucia Joyce the same evening he met her father, at their apartment in Paris. He was introduced by fellow Dubliner Thomas MacGreevy, who had preceded Beckett as a lecturer there in 1926.

MacGreevy and Beckett quickly became close friends, a friendship that lasted their lifetimes. A large number of Beckett’s letters are to him, perhaps the only person, and almost certainly the only man he ever seems to have truly confided in.

As well as the Joyce family, while in Paris, MacGreevy became a friend of Sylvia Beach, Nancy Cunard, and especially Richard Aldington, husband of HD (Hilda Doolittle), who described Beckett as “the splendidly mad Irishman.” In Beckett Remembering, Beckett describes that first meeting, though he doesn’t mention Lucia.

“I was introduced to Joyce by Tom MacGreevy. He was very friendly – immediately, to the best of my recollection. I remember coming back very exhausted to the École Normale and, as usual, the door was closed and I climbed over the railings.

I remember that: coming back from my first meeting with Joyce. I remember walking back. And from then on we saw each other quite often. I can still remember his telephone number!”

Joyce was keen to ask Beckett about everything that had been going on in Dublin and was also keen to find an assistant to help him transcribe sections of what was then called Work in Progress but eventually became Finnegans Wake.

Joyce’s eyes were by now very weak and painful. Beckett says that he was never officially Joyce’s secretary, but he was at Joyce’s apartment a lot of the time. It was through Joyce that Beckett met Ezra Pound at one of Joyce’s favorite Paris restaurants. Pound was in a bad mood, possibly because he was having to dine at a restaurant favored by Joyce, who liked eating at the Trianon.

Beckett still remembered the dinner and Pound many years later, though not warmly: “The only time I remember having met Pound was one evening at dinner with the Joyces in the Trianon, Place de Rennes. He was having great trouble with a fond d’artichaut and was very aggressive and disdainful.”

When Beckett first met Lucia there was no suggestion of her madness, though she was already troubled and in conflict with her parents, particularly Nora, who did not want her to pursue the dancing career she felt was her chosen path. She and her brother Giorgio had been moved between several countries while they were younger and had to learn a new language every time – someone said that Lucia was illiterate in four languages.

And being the daughter of such a universally revered father was difficult for her. Nora saw her main duty as being to allow Jim the quiet and space he needed to write – the children came second. But despite her parents’ objections, Lucia took dancing lessons, and took them very seriously. She performed in public several times. Beckett went with the Joyces to a dance performance she was in at the Bal Bullier on May 28, 1929.

Joyce’s niece wrote about Lucia’s shimmering costume (there is a photograph of her wearing it on the front cover of her biography by Carol Loeb Shloss).

“It was in silver sequins edged with green. One leg was covered to the heel and the other came right through the costume, so that when she put one behind the other, she created the illusion of a fishtail. Green and silver were entwined in her hair.”

Not long after, Lucia began to have self-doubt, and by November of that year she had given up dance forever. When she met Beckett, Lucia was twenty-two and he was twenty-three, but he was already much more mature than her; she was still a girl, having difficulty differentiating herself as an individual from the strong personalities of her mother and father.

Lucia was both attractive and attracted to men; Joyce’s niece said she was “pretty, with dark, curly shoulder-length hair and blue eyes with a slight cast but … attractive in spite of it.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Lucia Joyce on Bloomsday;

Photograph by Berenice Abbott

. . . . . . . . . . .

In photographs like the portrait by Berenice Abbott it’s easy to see the strabismus or squint in Lucia’s eye, which she had tried to have corrected, unsuccessfully. It does give her a rather wild look; any doctor inclined to think she was mad would not have a hard time convincing other people.

No one knows whether Beckett and Lucia slept together, but everyone agrees that she was the one pursuing him. Of course, there are precedents for artists becoming close to the daughters of their artistic mentors: Wagner and Liszt’s daughter Cosima; Ezra Pound and Dorothy, the daughter of Olivia Shakespear, Yeats’ mistress.

And there are many precedents for daughters looking for a partner who can substitute for their genius father. It might have been the perfect match, but Lucia seems to have pressured Beckett too much and for too long. He wrote to MacGreevy on July 17, 1930:

“ . . . a letter from Lucia too. I don’t know what to do. She is unhappy she says. Now that you are gone there is no one to talk to about that. I do not dare go to Wales [the Joyce family were staying in Llandudno], and I promised I would if they were there on my way through. But that is impossible. There is no solution. What terrible instinct prompts them to have the genius of beauty at the right – or the wrong – moment!”

Years later she was still pursuing him, even though he had told her one day in May 1930 at her parents’ apartment that he only went there to see her father and not her. She was devastated and told her mother.

Nora took her daughter’s side; she told Beckett not to play with her daughter’s affections. James Joyce told him he was not welcome at their apartment anymore. The rift between the two writers lasted until Joyce finally realized that his daughter was genuinely ill and that a serious relationship with Beckett would have been a disaster.

Years later, Beckett described his relationship with Lucia to his biographer James Knowlson curtly and rather cruelly, as if she had meant very little to him. He minimizes the rift with Joyce and Lucia’s part in it. He says that when he went to Joyce’s apartment that day:

“Lucia was there, already very disturbed mentally. Sometimes she was perfectly normal. I had to tell her finally that I went to the house not to see her, but to see Joyce. Joyce was my interest. And, according to some accounts, Joyce was very upset . . . And we used to walk, when she was perfectly normal. And then she had these crazy spells. I never saw her in them though. They all understood that she was incurable. But Joyce could never agree with them. He was all for trying different treatments, with Jung and so on.”

Despite his later attempts to play down Lucia’s importance to him, she undoubtedly played a big part in Beckett’s life. In 1932 he wrote a novel, only published posthumously, called Dream of Fair to Middling Women. In the novel there are three women, one of whom is called Syra-Cusa, representing Lucia – St Lucia of Syracuse is the patron saint of eyesight, a very good saint for Joyce, with his lifelong eye problems, to name his daughter for, but a cruel Joycean irony that she too had an eye problem in spite of, or perhaps because of it.

The narrator in the novel, obviously a version of Beckett himself, describes her – although she is fictional, she is quite similar to the actual Lucia whom Kay Boyle describes.

The Syra-Cusa: her body more perfect than dream creek, amaranth Lagoon. She flowed along in a nervous swagger, swinging a thin arm amply. The sinewy fetlock sprang, Brancusi bird, from the shod foot blue arch veins and small bones, rose like a Lied to the firm wrist of the reins, the Bilitis breasts. Her neck was scraggy and her head was null . . .

She was prone, when brought to dine out, to puke, but into her serviette, with decorum, because, supposedly, the craving of her viscera was not for food and drink. To take her arm, to flow together, out of step, down the asphalt bed, was a foundering in music, the slow ineffable flight of a dream-dive, a launching and terrible foundering in a rich rape of water. Her grace was supplejack, it was cuttystool and cavaletto, he trembled as on a springboard, jutting out, doomed, high of a dream-water. Would she sink or swim in Diana’s well? That depends what we mean by a maiden.

Like Joyce, Beckett here needs footnotes, two in particular: Brancusi was the sculptor whose drawing is on the title page of Harry and Caresse Crosby’s publication of Joyce’s Work in Progress, and Songs of Bilitis is an 1894 erotic, lesbian, fin de siècle sequence of prose poems written by Pierre Louÿs – a friend of André Gide, Oscar Wilde, and Claude Debussy – who claimed to have translated from a previously unknown Greek original. As for being a maiden, Lucia’s former love interest claimed that she was when she left him for Beckett.

But if Beckett thought he could get rid of Lucia so easily, he was mistaken. She continued to stalk him, as we would say now, for years. In a letter to MacGreevy of February 20, 1935 he is still saying: “She wrote wanting to see me. I have done nothing – except make détours.” In Middling Women, the narrator says:

We thought we had got rid of the Syra-Cusa. No such thing, here below, as riddance, good, bad or indifferent. Not having the stomach formally to disprove her letters merely, quickly, cite a circumstance of no importance to tickle our fauces. For days, holidays, she came not abroad, she stayed mewed up in her bedroom. What was she up to? Hold everything now. She was doing abstract drawing! Heavenly Father! Abstract drawing! Can you beat that one?

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth-Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young Adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

More about Lucia Joyce Fire in the Brain (The New Yorker) How James Joyce’s Daughter, Lucia, was Treated for Schizophrenia by Carl Jung Why Was James Joyce’s Daughter Lucia Written Out of History?

The post “Rosefrail and Fair” — Lucia Joyce, Dancer Daughter of James Joyce appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 29, 2022

Quotes from My Story by Kamala Das, the Poet’s Autobiography

Kamala Das (1934 – 2009), the Indian author and poet, was far ahead of her time. Even after her death, her words continue to hold much of relevance for Indian women — and perhaps for women across the world.

In addition to her poetry, she was known for her short stories as well as her autobiography, My Story. Here we’ll explore quotes from My Story, a book both widely admired as well as controversial.

Kamala Das (later known as Kamala Surayya) believed in living life on her own terms, and this reveals itself in her writings. Her confessional poetry style wasn’t one readily adopted by Indian poets, least of all women. Her English poetry has been compared to that of Anne Sexton’s and won her recognition and literary awards during her lifetime.

Her writings look at Indian society with a critical eye, questioning its intransigent patriarchy and deeply entrenched notions of how women are expected to behave. Where love is concerned, there is a yearning for romanticism, which ends in cynicism. A quest for the spiritual is also visible in her writings, especially her poetry.

In the Preface to My Story, Kamala Das wrote:

“Some people told me that writing an autobiography like this, with absolute honesty, keeping nothing to oneself, is like doing a striptease. True, maybe. I, will, firstly, strip myself of clothes and ornaments. Then I intend to peel off this light brown skin and shatter my bones. At last, I hope you will be able to see my homeless, orphan, intensely beautiful soul, deep within the bone, deep down under, beneath even the marrow, in a fourth dimension.”

My Story was originally in Malayalam, titled Ente Katha, describes the events and forces that shaped the authors views as she came into her own. The book earned her praise as well as notoriety for its honesty, particularly about sexuality.

And in an interview with Iqbal Kaur about she wrote My Story the way that she did, Kamala Das said:

“I needed to disturb society out of its complacence. I found the complacence a very ugly state. I wanted to make women of my generation feel that if men could do something wrong, they could do it themselves too. I wanted them to realize that they were equal. I wanted to remove gender difference. I wanted to see that something happened to society, which had strong inhibitions and which only told lies in the public.”

Following is a selection of timeless, thought-provoking quotes from My Story by Kamala Das.

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Kamala Das

. . . . . . . . . .

“A poet’s raw material is not stone or clay; it is her personality.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Children are intuitive about people and feel more than adults a sense of rejection.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I was a burden and a responsibility neither my parents nor my grandmother could put up with for long.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“My grand uncle liked to see women glamorized with jewels and flowers. His second wife, my favorite aunt, was never seen even at night without her heavy jewelry, all gem encrusted and radiant … Each night she came to our house accompanied by her maids and a lantern, looking like a bride. And she walked up the steep staircase of the gatehouse to meet her famous husband in their lush bedroom, kept fragrant with incense and jasmine garlands.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Poets, even the most insignificant of them, are different from other people. They cannot close their shops like shop men and return home. Their shop is their mind and as long as they carry it with them, they feel the pressures and the torments.”

. . . . . . . . . .

10 Poems by Kamala Das

. . . . . . . . . .

“One’s real world is not what is outside him. It is the immeasurable world inside him that is real. Only the one who has decided to travel inwards, will realize that his route has no end.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The obsession with sin destroyed the mind of several girls who were at the beginning of their adolescence, normal and easy-going. If there was a dearth of sin, sin at any cost had to be manufactured, because forgiving the sinners was a therapeutic exercise, popular with the rabidly virtuous.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Society can well ask me how I could become what I became, although born to parents as high-principled as mine were. Ask the books that I read why I changed. Ask the authors dead and alive who communicated with me and gave me the courage to be myself. The books like a mother-cow licked the calf of my thought into shape and left me to lie at the altar of the world as a sacrificial gift.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Marriage meant nothing more than a show of wealth to families like ours. The bride was unimportant and her happiness a minor issue.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“With words I had destroyed my life. I had used them like swords in what was meant to be a purification dance, but blood was unwittingly shed.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Wherever a writer goes, her notoriety precedes her.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“We are trapped in immortality and our only freedom is the freedom to decompose.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Today at Nariman Point the tall buildings crowd one another. But when I was young and in love with a grey-eyed man it was a marshy waste. We used to walk aimlessly along the quiet Panday Road or cross the Cuffe Parade to walk towards the sun. We did not have a place to rest. But in the glow of those evening suns, we felt that we were Gods who had lost their way and had strayed into an unkind planet.”

. . . . . . . . . .

More about My Story by Kamala Das Review on Purple Pencil Project Reader discussion on Goodreads Wikipedia. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Melanie P. Kumar: Melanie is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

The post Quotes from My Story by Kamala Das, the Poet’s Autobiography appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 27, 2022

Women Authors’ Friendships: Mutual Support & Companionate Rivalry

When it comes to women author’s friendships, it’s understood that the writers’ common struggles benefit from mutual support. I wonder how much rivalry is involved, though, since writers can be an envious lot.

There are few templates for friendships between women writers, especially after one or both achieves some measure of success. Yes, there is mutual support. And yes, there is a measure of envy and rivalry.

This type of camaraderie has, and has always had, its delights as well as its complications. The well-known friendships between women who are now considered classic authors were no exception.

. . . . . . . . . .

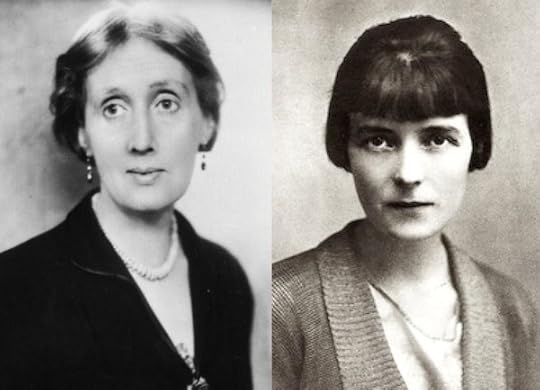

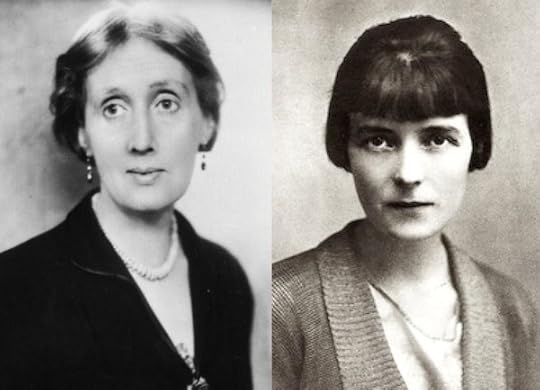

Virginia Woolf & Katherine Mansfield