Goodnight Moon: On Falling Asleep in Order to Wake Up

This essay is excerpted from “An Unreasonably Deep Analysis of Goodnight Moon: On Finding (or Creating) Meaning in Dreams” by Eponynonymous.

My daughter used to fight sleep like grim death. Every night as she was dozing off, she would suddenly recoil, bouncing back from that hypnagogic state with flailing arms and banshee screams. It was as if she saw what lay on the other side of sleep and what she saw was death. Oblivion. I don’t think the analogy is too dramatic.

To a baby, bedtime really is a little death. Her sense of self is tenuous, her dreams not so easily distinguished from reality, and her mind freighted with new experiences that some psychologists say have the effect of slowing time. As it was, my daughter came to recognize those grim portents of sleep, and one of them was Goodnight Moon.

It’s a wonder Margaret Wise Brown’s masterpiece isn’t celebrated as a work of existentialist horror, one which plays on the belief that things exist regardless of our awareness of them. Combs, chairs, bowls full of mush—these things are lifeless, objective, impervious to introspection, and wholly beyond the mind which observes them.

We believe the world is made of “things,” and those who experience them are merely privileged with the senses to do so. Even the act of experience is understood to be an object of complex neurosensory activity in the brain, and subjectivity is only a particularly convincing illusion of emergent neural phenomena. Our consensus model of reality, as it were, speaks in the passive voice: object begets subject.

. . . . . . . . .

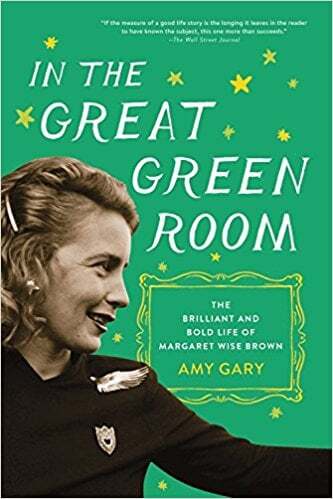

Margaret Wise Brown, photo by Consuelo Kanaga

courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . .

Not so the voice in Goodnight Moon, whose steady itemization of stars and balloons and little toy houses serve like rosary beads for the flighty spirit-voice, whose accruing mantra of “goodnight” foretells the end of all experience, even as it clings to the objects that define it.

Do these things persist when we close the book? What about when we close our eyes? To crib a famous thought experiment, if a quiet old lady is whispering hush and there’s nobody around to hear it, does she even make a sound? I think about this while rocking my daughter to sleep.

First published in 1947, Goodnight Moon was nothing if not a break from convention. Without any characters or coherent narrative, it was more like a lyrical stage set than a children’s story. Brown herself got the idea from a dream, having jotted down the words as soon as she woke up.

The lack of plot could not have troubled her less. As an educator, she championed the philosophy of author Lucy Sprague Mitchell, whose “here and now” approach to children’s literature sought to harmonize storytelling with the raw, sensory-laden experience of being a kid. Plot, character, morality—these were only incidental to a good story. More important is to reflect the child’s reality by heightening her experience of it. Such is the mandate, Brown believed, of all “sincere art.”

Today, Goodnight Moon is a classic, but in 1947 its charms were hardly assured. Early sales were slow. Anne Carroll Moore, the esteemed children’s librarian at the New York Public Library, famously called it an “unbearably sentimental piece of work,” going so far as to help blacklist the book for nearly 25 years—a draconian measure that might have stunted its popularity. (In one revealing incident in 1951, Brown was blocked from a book ceremony at the very library that had so excoriated her work.)

What exactly was Moore’s beef with Goodnight Moon? In a word, it was too realist, which is a shame because most kids who grew up with the book will attest to its profound strangeness. Rather than tantalizing children with a daytime odyssey to Oz or Neverland, Goodnight Moon lulls them to sleep with a gloomy portrait of a “great green room.”

Here, everything fantastical—three bears sitting in chairs, a cow jumping over the moon—is confined to picture frames hung on the wall. The only exception is in illustrator Clement Hurd’s decision to depict the story’s only characters—the bedridden child and the quiet old lady—as fluffy-tailed rabbits. The effect is soporific, and a little uncanny.

The Great Green Room’s true purpose, it seems, is not to lull juvenile rabbits to sleep but to simulate an underworld for them, an underworld where subjectivity obtains. Here, in this dreamy, second-person purgatory, all meaning that belongs to the world of the day has been cut loose. Here, in the night world, objects are only their appearances—a parody of the reader’s waking life, dependent as it is on dichotomies and boundaries and the unexamined assumption that the universe is devoid of meaning.

For just such an outlook, Goodnight Moon tells a story about falling asleep in order to wake up.

. . . . . . . . .

See also: In the Great Green Room: The Bold and Brilliant Life

of Margaret Wise Brown by Amy Gary

. . . . . . . . .

When my daughter was two months old, I had a dream of a creature perched atop her crib, peering down at her. Silent and serene, its knees were folded into its chest like a gargoyle. I knew the vision was only a figment of my imagination because I knew I was dreaming. But I still couldn’t move, and the thought was already gnawing at me that this gargoyle was, in some transcendent sense, real.

Why else would dreams take symbolic form if not to condense meaning too vast and complicated for our waking, literal minds to unpack? So I tried to scream myself awake, alert my wife lying beside me, unstick myself from the throes of sleep paralysis. Something stirred, my wife rolled over and shook me awake, and the transition was like a dive into cold water. A little birth.

When I see my daughter, asleep in her crib, cataloging the objects of the day, ossifying babble into a native tongue, I’m gripped by a tension between love and fear—love for this separate soul too divine for language, and fear for a world whose claws are out.

The Vedantists would say my fear is a manifestation of Ahaṁkāra, or egoic attachment. Buddhists would blame a kind of metaphysical ignorance known as Avidyā. But the lesson is more or less the same: Let go of the ego and fear will scatter. (Or, if you prefer the stylings of Frank Herbert: “Fear is the mind killer.”) What remains is the very bridge between subjects, that which expands over a vast and illusory sea of things.

That’s love. Pure and simple. And it seems Clement Hurd might have had this in mind. As his son Thacher Hurd told NPR in 2022, Goodnight Moon “mirrors what’s happening for the child, but it also gives them a feeling of some other world, something else that’s sort of a larger, more peaceful world.”

What would you call such a place? Maybe you should ask your dreams.

Read the essay in full on Substack.

The post Goodnight Moon: On Falling Asleep in Order to Wake Up appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.