Nava Atlas's Blog, page 38

June 23, 2021

Novel on Yellow Paper by Stevie Smith (1936)

This analysis of Novel on Yellow Paper by Stevie Smith (1936) is excerpted from Amongst Those Left by Francis Booth. Reprinted by permission.

‘This book is the talking voice that runs on, and the thoughts come, the way I said, and the people come too, and come and go, to illustrate the thoughts, to point the moral, to adorn the tale.’

Born Florence Margaret Smith, in Kingston Upon Hull, England, Stevie Smith (1902 – 1971) is now better known and loved as a poet than as a novelist. All her novels were written relatively early in her life and are all unconventional. Smith was brought up, along with her sister, by her feminist aunt Madge Spear, whom she called ‘The Lion Aunt’ and with whom she lived all her life.

“Dear Auntie Lion, I do so hope you will forgive what is written here. You are yourself like shining gold. When I think of what some women are like, I am full of humble gratitude and apprehension that I have you to live with.”

Smith lived a creative and intellectual life largely independent of men. She knew personally many artistic and creative women and corresponded with many others. However, she did not make a living from her writing and worked in the very male world of publishing; like Ann Quin a generation later she worked as a secretary, from 1923 to 1953.

Smith had been writing poetry for ten years when she first submitted her poems to an agent, who suggested she should write a novel instead; Novel on Yellow Paper (1936), was the result. After that she published her first volume of poetry, A Good Time Was Had By All (1937), which was followed by more poetry and two more novels.

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

Smith’s three novels – Novel on Yellow Paper; or, Work It Out For Yourself, 1936; Over The Frontier, 1938; The Holiday 1949 – are all decidedly internalized and autobiographical: the world of externals only seems to exist through the narrator’s rather eccentric view of it and her flowing, rambling chatter, which seems to have no ordering principle other than that of the association of ideas.

After the last novel was published in 1949, she concentrated on her poetry. Having left her secretarial job in 1953 she reviewed books, published sketches and read her poetry in public, becoming well-known especially for the poetry collection Not Waving But Drowning, published in 1957.

The narrator of the first two novels, Pompey Casmilus, is a thinly veiled version of Smith herself; in the first novel she talks entirely about herself, her opinions and her life at work and in her small social circle. Over The Frontier starts in similar vein but Pompey then goes to Germany and the novel (which was published just before the Second World War) turns into a parody of a certain kind of jingoistic thriller written by John Buchan and others.

. . . . . . . .

Novel on Yellow Paper on Bookshop.org*

Novel on Yellow Paper on Amazon*

. . . . . . . .

Whereas Novel on Yellow Paper had been concerned with anti-Semitism, Over the Frontier is concerned with German militarism. Smith’s third novel, The Holiday, published more than ten years later, is more conventional and though it has characters – the central figure Celia is in many ways like Smith herself – and a frustrated love story, it is mainly concerned with post-war Britain and its role in the world and many of the characters speak as if merely voicing Smith’s own views.

Novel on Yellow Paper is so titled because the narrator is said to be composing it on office paper while she is at work:

“I am typing this book on yellow paper. It is very yellow paper, and it is this very yellow paper because often sometimes I am typing it in my room at my office, and the paper I use for Sir Phoebus’s letters is blue paper with his name across the corner ‘Sir Phoebus Ullwater, Bt.’ and those letters of Sir Phoebus go out to all over the world. And that is why I type yellow, typing for my own pleasure.”

The narrator, who, like Smith herself, is a private secretary who lives with her aunt, makes it clear that this is going to be an experimental novel:

“But first, Reader, I will give you a word of warning. This is a foot-off-the-ground novel that came by the left hand. And the thoughts come and go and sometimes they do not quite come and I do not pursue them to embarrass them with formality to pursue them into a harsh captivity. And if you are a foot-on-the-ground person I make no bones to say that is how you will write and only how you will write. And if you are a foot-on-the-ground person, this book will be for you a desert of weariness and exasperation. So put it down. Leave it alone. It was a mistake you made to get this book. You could not know.”

Despite the apparent frivolity and lightness of tone of most of the book, Pompey (and therefore Smith) are well aware of world politics and have serious things to say, especially about German fascism. Pompey has been to Germany and stays in the house of Jewish friends in Berlin. ‘Oh how I felt that feeling of cruelty in Germany, and the sort of vicious cruelty that isn’t battle-cruelty, but doing people to death in lavatories.’

It is important to remember that this was at a time when the British government and monarchy still had full diplomatic relations with Germany and that the policy of appeasement would continue for several years.

No one had yet predicted the horrors of war or the Holocaust and, although a few committed writers like George Orwell, Christopher Caudwell and Ralph Fox were leaving to fight fascists in Spain just as Novel on Yellow Paper was being published, Smith’s political insight in this novel is far in advance of the great majority of the writers of the time.

But despite the seriousness of this message, the novel keeps its lightness and its constant reminders that it is indeed a novel, addressing the reader and talking about literary technique. Pompey discusses her friend Harriet who is a poet but wants to write a book about fashion. Harriet does not know how to keep the book to a reasonable length.

“But with me, I shall have no such difficulty. I shall know when to stop. And whatever I write then will be Volume Two.

But Harriet in her writing form has a very exact and precise sense of form. And that is a thing I am not able to come by. Reader, it is a fault.

People have said to me: If you must write, remember to write the sort of book the plain man in the street will read. It may not be a best seller – but it should maintain a good circulation.

About this I pondered for a long time and became distraut [sic]. Because I can write only as I can write only, and Does the road wind uphill all the way? Yes, to the very end. But brace up, chaps, there’s a 60,000 word limit.

Oh how irritated I am by this funny idea of keeping your feet on the ground. Spoken like an officer and a gentleman, Sir People. Spoken like a prig and a nincompoop.”

More about Novel on Yellow Paper Book of a Lifetime: Novel on Yellow Paper Reader discussion on Goodreads The Modern Novel

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Novel on Yellow Paper by Stevie Smith (1936) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

When the Present Clashes with the Past: Reminiscences of Enid Blyton

Quite often in life, the innocence and idealism of one’s childhood years are intruded upon by the realities and pragmatism of adult life. But when one is forced to reckon with the labeling of a favorite author of one’s childhood, one will necessarily need to have a dialogue with the past to find a balance with the present. The author in question is Enid Blyton, who was called “a racist, sexist homophobe and not a well-regarded writer,” by the members of the Royal Mint, who in 2019 blocked attempts to give her a commemorative coin.

Recently, the issue resurfaced when the UK-based charity, English Heritage, in the light of the Black Lives Matter movement, decided to update its website with information on Enid Blyton. Their Twitter account stated:

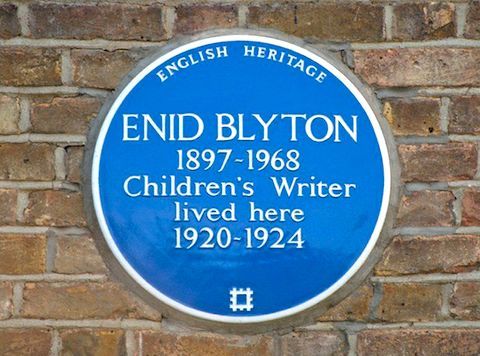

“Our 1997 Blue Plaque to Enid Blyton is back in the news along with our online bio of the children’s author, whose books are loved by many. We can fit about 19 words on each plaque. Our website provides a fuller picture of the person’s life, including any uncomfortable aspects.”

. . . . . . . . .

The plaque in question; photo: BBC

. . . . . . . . .

The website now states that Blyton’s work has been criticized during her lifetime and after, “for its racism, xenophobia and literary merit.”

Born in 1897, Enid Blyton is well-known for her Famous Five and Secret Seven adventure stories, as also the stories revolving around schools, not to forget the picture tales of Noddy, the wooden boy, created by a carpenter, just like Pinocchio, which comes alive.

Apart from the recent hullaballoo, Blyton’s works have always courted controversy with libraries across the world removing her books from their syllabus and the BBC refusing to dramatize her work, between 1930 and 1950, and terming her a “tenacious second-rater” in their internal correspondence.

Blyton was also accused of gender bias, as tasks were clearly divided between men and women, with the men doing the brain work whilst the women cooked and dished out picnic lunches and the girls washed up afterward. But again, these need to be seen in the context of the years (1928-1960) that Blyton wrote the majority of her stories — a time when a life of domesticity was the lot of most women.

A reader’s reminiscence

For my siblings and me, and other children growing up in India, Enid Blyton has almost been a rite of passage, where none of the above messages even took hold. This author was among the first to open up the love for reading in me and occupies a very special place in my heart.

To Blyton goes the credit of opening up a magic world, which we tried to recreate in our own lives. During summer holidays, a chicken coop would be converted into a Club House just like the one that the Five Find-Outers had. We emulated them even in the password that had to be uttered before being allowed into the Club House, by the designated leader of that week.

Whilst Blyton might have allotted the powerful roles to the boys, this was not the case with us, as we chose not to take her literally. This apart, a plank nailed on to a mango tree doubled up as a Tree House. When we tired of these two options, there was always the Tent House to crawl into, made up of a large tarpaulin sheet, which was actually a cover for our Dad’s Ambassador car.

The parleys in these three “Houses” would also lead to some real adventures, where we headed out to a junction where two rivers met, some distance from our home. We were accompanied by a few friends, all fueled with the same sense of adventure as the Secret Seven. There were even some not very successful attempts at lighting makeshift fires to cook some beans etc., which we forced ourselves to eat, just for the thrill of doing what our adventurous idols would do in Blyton’s stories.

The other event that caused excitement from Blyton’s tales were the midnight feasts planned by the “Naughtiest Girl in the School,” Elizabeth Allen or the girls from the St. Claire’s series. The tuck that these girls shared — scones, potted meat, clotted cream, etc. were so far removed from any food that Indian kids were used to, that we truly longed to sample them.

On a visit to Oxford, when a friend took us for a drive to a scenic spot beside a river, she also ordered some refreshments, for us to snack on. When she said, “clotted cream,” my mind transported itself back to the Enid Blyton tales and all I could think was, “I wish I could tell my friends from back then that I had actually tasted something that we had all drooled over, in our imagination.”

So, thoughts of Enid Blyton can only bring back memories of an idyllic childhood, devouring her books, reading them in the order that they were meant to be read, and comparing notes with siblings and friends, about how far they had progressed. At that point in time, nothing in those books struck me as being negative towards any character, except regarding behavior at school, or attitudes towards teachers and friends.

. . . . . . . . . .

Books by and about Enid Blyton on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

No doubt, Enid Blyton, as an adult, could be accused of using politically incorrect terminology, which may not pass muster in books for children today. But I am almost certain that most of us just took the character descriptions at face value, without thinking of skin color or anything along those lines. Mentions of golliwogs were just accepted as props to a story, as we as children inhabited a world of innocence.

This piece is written more in defense of a childhood that was spurred by the world of imagination that Enid Blyton managed to create for generations of children. Even my daughter started her days of reading with Noddy books, moved on to the other adventures, and seems none the worse for it.

I wonder if any of the racism or xenophobia that prevails in my country or the world today can be attributed to Enid Blyton. There are war heroes like Winston Churchill, Robert Clive, and others who have done much more damage to my country and were inherently racist and xenophobic — and whom Britain has glorified. One has to wait and see when English Heritage will think of removing the whitewash surrounding such people.

Contributed by Melanie P. Kumar: Melanie is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about the Enid Blyton controversy Why it’s Important to Note Enid Blyton’s Failings, Not Erase Her Work Enid Blyton Fans React to ‘Racist’ Label Enid Blyton: Heritage Bosses Respond to Racism, etc. English Heritage Has No Plans to Remove PlaqueSee more of this site’s Literary Musings.

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post When the Present Clashes with the Past: Reminiscences of Enid Blyton appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 20, 2021

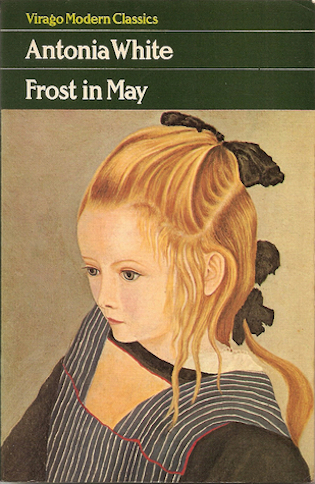

Antonia White, author of Frost in May

Antonia White (born Eirene Botting, March 31, 1899 – April 10, 1980) was a British author best known for her autobiographical novel Frost in May. In addition to producing other novels and short stories, she was an accomplished translator from French to English.

Her well-documented struggles with mental health resulted in her being committed to an asylum in her early twenties, an experience that she used as the basis for some of her fiction. Other notable themes in both her life and work were religion, particularly Catholicism, and her difficult relationship with her father and daughters.

Early life and introduction to religion

Antonia’s early years were spent at the family home in Kensington, and at Binesfield, the Sussex cottage owned by her paternal grandparents. When in London she spent most of her time either alone with her beloved toy dog Dash, or in the care of the already busy housekeeper.

Antonia’s father, Cecil Botting, was a renowned classics scholar and teacher, and it was he who unilaterally chose the hated birth name of Eirene Botting, spelled in the classical Greek way, for his only daughter. (She would change it later, using her mother’s maiden name of White and her childhood nickname ‘Tony’ as the basis for the more feminized ‘Antonia’.) Nevertheless, Cecil assumed an importance and dominance in Antonia’s life that far outweighed that of her mother, Christine. Biographer Jane Dunn wrote that he ‘looms as the most imposing, demanding, and threatening male figure in Antonia’s life.’

Cecil’s interest in his daughter was more intellectual than emotional, and he started teaching her Greek when she was just three years old. However, it was Cecil’s religious epiphany and conversion to Catholicism that had the greatest, and arguably the most damaging, effect on the young Antonia.

At just seven years old, she was obliged to follow her father into the Church, and for the first time was exposed to the concepts of religious sin and guilt; she later said: ‘I never did feel free again.’ She felt that the religion had been imposed on her, and would spend the rest of her life in the spiritual conundrum of having been neither born to Catholicism nor irrevocably drawn to it herself, unable to abandon it completely and yet also unable to accept the fundamental tenets of a faith that she never wholeheartedly believed in.

The Convent of the Sacred Heart

In September 1908, Antonia was enrolled as a pupil at the Convent of the Sacred Heart Roehampton, a well-established Catholic boarding school that drew an international group of students, mostly from high-ranking European families. She felt out of place, both as a middle-class girl and as a recent convert who hadn’t yet learned (and never really would learn) how to wear her religion casually.

‘I could not boast of having been dedicated to Our Lady and dressed exclusively in blue and white for my first seven years; I had not even a patron saint,’ she recalled. The spiritual regime under the nuns did little to encourage her. Bright, talented, and eager to learn, her enthusiasm and natural pride in her achievements were crushed and dismissed as sinful. It was not her will that counted, she was taught, but God’s, and her desires must be broken in order to be remade in God’s own fashion.

It was at the Convent that Antonia’s tortured relationship with creativity and writing began. She credited her time there with inspiring her to write; she genuinely believed that without the nuns’ education, she would never have picked up her pen. On the other hand, it was also at the Convent that she received a cruel blow to her burgeoning creativity, one that she would also later blame for her lifelong writer’s block.

She had fallen ill during the spring term of 1914 and started a novel during her convalescence, both as a way of passing the time and as a way of winning her father’s approval (which she was forever seeking and usually failing to find) for her piety. The plot involved the heroine becoming a Carmelite nun and the hero becoming a Jesuit, both sinners reformed by faith. Unfortunately, the manuscript was discovered at the sinning stage, before she had had a chance to write their conversion.

On her fifteenth birthday, she was summoned to face her father, who accused her of perversity and indecency and gave her no chance to explain or defend herself, and ordered that she leave the Convent immediately. Antonia would always maintain that this episode had traumatized her to such an extent that she was never able to write from pure imagination again.

All of her work would be heavily based on real events, and her first novel Frost in May was essentially an account of her time at Roehampton with all her conflicting feelings about it, the vivid and narrative told through the voice of young Nanda Grey.

Teaching and a first marriage

After finishing her schooling at St Paul’s Girls School, Antonia rejected her father’s ambitions for her to go to university and instead took a series of jobs, first as a governess to a wealthy Catholic family and then as a teacher at a boys’ school. The money was a key factor in her decision; she considered her own income vital for her independence, and her finances (or lack of them) would preoccupy her for the rest of her life.

Although she had always rebelled against the idea of becoming a ‘schoolmarm,’ Antonia found that she enjoyed it. She taught Latin, French, and Greek, but struggled to control her classes and had to negotiate the boys’ good behavior by agreeing to tell them ghost stories halfway through the lesson if they had completed all their work. She was asked to leave after two terms when the headmaster walked in at the climax of a particularly gruesome story. This period of her life was later fictionalized in her second novel, The Lost Traveller.

During this time she met Reggie Green-Wilkinson. They were ill-suited: Antonia later described the two of them as Hansel and Gretel, two doomed children wandering in the woods of London, but they became engaged when Antonia was just turning twenty-one.

After their marriage, they set up home together in Chelsea, where Antonia felt free of the constraints of her Kensington childhood, and that she could become the artist she wanted to become. It was here that Antonia first experienced the mental illness that would afflict her for the rest of her life.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The asylumHer third novel, The Sugar House, details this difficult time with an acute and harrowing awareness; on rereading it later, Antonia commented, ‘… all that queer, horrid Chelsea time leading up to the asylum…How painfully well it described this state of mind which I first knew in 1921.’

It began with a feeling of depression and isolation, a state which quickly escalated into oppressive fear and disorientation. She felt non-existent, to the extent that she was surprised to see letters addressed to her, and once rushed into the sitting room full of mirrors expecting to see nothing reflected in them.

Reggie was also unhappy, drinking heavily, and their poor financial situation did not help her state of mind. In summer 1922 she began the process of annulment, an excruciating process that took two years to complete and involved an interview and a physical examination.

Her mental health declined rapidly, and the period of depression was followed by a mania so severe that she felt it was almost supernatural. Later, in her fourth novel Beyond the Glass, she would write of this experience: ‘It was difficult sometimes not to burst out singing or laughing from sheer ecstatic joy’, and she explained this fictionalized episode to her friend Emily Coleman by saying that, ‘She [Clara] is going mad without knowing it, and this false ecstasy is the sign.’

By November 1922, Antonia’s health had deteriorated to such an extent that her father had her committed to Bethlem Royal Hospital. Violent, fearful, free of any inhibitions, she was unable to communicate properly and was deemed a risk to herself and others.

She stayed there for nine months, during which time she was subjected to padded cells, strait-jackets, icy cold baths, force-feeding, and a regimen of strong sedative drugs, all often experienced through hallucinations and psychosis. It was an experience that was both rich and terrifying. She was finally discharged in August 1923 and returned to her parents’ house in London.

Family life of sorts

In April 1925, Antonia married her friend Eric Earnshaw Smith. He was a homosexual, and their love — although very real — was purely platonic, which suited Antonia. She was terrified of sexual relations and had never found any pleasure in them.

A talented poet who also worked for the Foreign Office, Eric was probably the most important man in Antonia’s life after her father. He gave her the intellectual stimulation and companionship she craved and was able to deal with her continued violent tempers and mood swings. His gentle questioning and debate around spirituality were also influential in her gradual estrangement from the Catholic Church. Both had affairs but never strayed too far from the other.

By 1928, however, Antonia felt that she was ready for a relationship that encompassed sexual love as well. It was at this time that she met Silas Glossop, a mining engineer who wrote poetry and loved reading. Initially, the affair was simply one more in her open marriage to Eric, but in December 1928, Antonia discovered that she was pregnant. Her subsequent decision to leave Eric for Silas was, she claimed, one of the hardest she ever made, and one that she often regretted.

During her pregnancy, Silas took a mining job in Canada, hoping that he would have the opportunity after his contract to complete his doctorate at Harvard. He needed the job to provide for his unexpected family, and despite Antonia’s unhappiness over the separation he left in May 1929. On August 18, after a long and difficult labor, their daughter Susan was born, but with the little family still separated and Antonia’s mental health still precarious (especially after the death of her father in November 1929), she was quickly sent to a private residential nursery at Roehampton and remained there for almost a year.

During this time, Antonia had supplemented her allowance from Silas with part-time work at an advertising agency, Crawford’s. She had previously worked freelance as a copywriter, and while she did not enjoy the work (believing it to be routine and in direct opposition to her creative ambitions) it paid well, and she was good at it. It was here that she met Tom Hopkinson. From the start their relationship was unbalanced; she was much more romantically attracted to him, while he was more sexually attracted to her.

But when Silas finally returned to London in September 1930, Antonia was forced to make another choice. This time it came down to money, and after several months of turmoil, she settled on Tom: ‘I believe I wouldn’t marry Si because he had no money. I believe I married Tom because he had a regular job and a hundred pounds or two…’

Her decision was settled when, in November of that year, she discovered she was pregnant again. Given the confusion of the past weeks could not be sure who the father was, but with Tom’s relatively stable financial situation it suited her to have him believe it was his child. For several years she also allowed Susan to believe that Tom was her father too. Tom and Antonia were married in November 1930 in Carlisle Cathedral, and another daughter, Lyndall, was born in July 1931.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

The following years were ones of highs and lows for Antonia, both professionally and personally, and defined by continued mental health struggles. Her relationship with Tom was a difficult one: both felt used by the other in the marriage but were encouraging and supportive to each other in their writing.

It was with Tom’s support that, in November 1932, Frost in May was finally finished. It was accepted for publication by the fledgling Harmsworth, with later editions published by the Nonesuch Press, and its success was such that it upset the delicate equilibrium of Antonia’s relationship with Tom, who felt that he was fast becoming the inferior partner in an already unequal marriage. In December of that year, he signed a letter to her, ‘your foolish, incompetent, ill-writing, conceited, detestable, unintelligent and worn-out husband, Tom.’

Tom embarked on an affair with a married woman, Frances Grigson, signaling the beginning of the end of the marriage and the start of a cycle of mental illness for Antonia which would never really end. Sojourns with friends (such Emily Coleman, Peggy Guggenheim, and Djuna Barnes) left her more exhausted than refreshed, and a trip to Brittany with Tom in 1934 was cut short after Antonia suffered recurring and terrifying hallucinations and nightmares.

She became desperate, attempting to describe ‘the beast,’ as she called it, to Tom: ‘This perpetual inner torture is a disease and productive of no good to myself and no one else. But no act of will can destroy it … this meaningless suffering is like a cancer, making one repulsive to oneself and everyone else.’ She pleaded with him to kill her, saying that, ‘It would be much the best thing for you to do.’

The episode left Antonia feeling lonely, isolated, and tormented with guilt. By 1935 her relationship with Tom broke under the strain. She moved out of the family home, leaving him with the children and a nurse for help, and began a course of intensive psychoanalysis with Dr. Dennis Carroll that would last four years.

The start of a troubled relationship

Antonia’s mental breakdowns were mirrored in her eldest daughter Susan. It was the first of many in which the struggles of the mother would be echoed in the daughter. Tom was sufficiently concerned that he arranged for Susan to have a course of psychoanalysis. It was also arranged that he should move out of the family home to allow Antonia to move back in, a surprising suggestion from Dr. Carroll. It was intended to make both Antonia and Susan feel more secure, but given the children’s closeness to Tom, and Antonia’s delicate state of mind at the time, it wasn’t entirely a success.

In 1937 Antonia instigated a divorce from Tom. Although in future years she would have affairs—- notably with Eric Siepmann, Bertrand Russell, and David Gascoyne — she would never marry or have a lasting relationship again. She also finally told Susan that her real father was Silas.

Silas, although now deep into a love affair with Djuna Barnes, was happy to take Susan to tea once a week, and Susan appeared to like the idea of having a father all to herself. The emotional impact, however, of feeling as if Tom was no longer hers (and also that Lyndall was now somewhat estranged from her) increased Susan’s already apparent feelings of loneliness. The impact of Antonia’s moods and mental state began to affect her more directly. It was the start of a difficult and troubling period in Antonia’s relationship with her eldest daughter that would last for several years.

War work, and return to Catholicism

As Britain prepared for war, Antonia’s mental state improved markedly. In 1939 she wrote to Emily Coleman, ‘Funnily enough I’ve never had such a peaceful life as I’ve had since Sept. 1st…I feel very calm, only fretting in inaction.’

In December, her mother died and she inherited Binesfield, the Sussex cottage that had given her so much pleasure in her childhood. She hoped to be able to live there with the children, but concerns about bombing delayed the move. When Antonia got a job with the BBC, working on their American and Canadian programs, it was put off altogether.

Susan was hurriedly packed off to boarding school in Salisbury, while Lyndall was sent to live with Tom and his new wife, Gerti. Antonia thrived in the high-pressure atmosphere of London during the Blitz and attempted to maintain some semblance of family life by visiting Susan some weekends. She didn’t, however, bother to visit Lyndall, who after 1942 was a boarder at Headington School near Oxford.

In 1943 she left her job at the BBC and began working at PID, the secret Political Intelligence Department of the Foreign Office, where she worked with Americans on propaganda operations in France.

The work was intense, often six or seven days a week and long hours each day, and while at first, Antonia loved the busyness of it she soon became burnt out. The demands of wartime took their toll, and she struggled with the old symptoms of depression, weeping, and lethargy.

She found some consolation in her religion, to which she had returned quietly at the end of 1940. She had been engaging in correspondence with a Joseph Thorp, known as Peter, who had first written to her about Frost in May. Their letters concentrated on religion and Catholicism and turned into an acute analysis of Antonia’s shifting intellectual and spiritual beliefs. This correspondence was eventually published in 1965 as The Hound and the Falcon.

Domineering women

At the end of the war, two women came into Antonia’s life who would dominate her mentally, emotionally, and spiritually for some years afterward. In 1946, she met Benedicta Bezer, a recent convert to Catholicism who had previously led a wild life of drugs and clubs in London and Paris, and who was known as a lesbian.

The two women became very close very quickly, and even Antonia would later look back and view their relationship as one of the more bizarre episodes of her life. Benedicta herself was close to insanity, and her manias presented themselves as religious fervor, saintly delusions, and prayer sessions that could last for days.

Both Antonia and eventually Susan (who had followed her mother into Catholicism, and been baptized at Brompton Oratory in August 1945) were drawn into a toxic web of hysteria that bordered on madness. Antonia admitted that her attraction to Benedicta was partly sexual, and Susan felt spellbound, entranced by Benedicta’s attractiveness and religious passion. But it was not long before the fervor sparked a crisis and collapse in Susan and a subsequent similar collapse in Antonia. The relationship with Benedicta was over, but the shared experience of infatuation and loss brought Antonia and Susan closer together than ever before.

Antonia, however, immediately fell into the circles of Dorothy Kingsmill, a self-styled, untrained psychoanalyst, who used her ‘intuitive gift’ to manipulative ends. Antonia turned to her for treatment after the debacle with Benedicta, and although she did not pay in money for their sessions (since Dorothy considered it her vocation) a relationship of control and obligation developed.

In August and September of 1947, Antonia suffered a series of psychological crises, alternating between severely heightened anxiety and the ‘downers’ of complete lethargy. At the same time, Dorothy experienced a nervous breakdown which she blamed on the strain of dealing with Antonia’s “shadow side”. The relationship with Dorothy finally broke down in 1949 with letters from Dorothy accusing Antonia of being ‘depraved’ and ‘monstrous,’ leaving Antonia exhausted and mentally fragile.

The Lost Traveller, translation, and estrangement from Susan

In April 1950, The Lost Traveller was published. In it, Nanda Grey’s name had been changed to Clara Batchelor, but her character and the story were essentially continuations of Frost in May, and the book was just as autobiographical; a powerful evocation of the adolescent struggle Antonia herself had faced between the spiritual life and the attractions of the outside world.

She felt eased by the publication and the positive reviews and was able to start work almost immediately on the next book in the sequence, The Sugar House. It was at this time too that she started translating from French, beginning with Guy de Maupassant’s Une Vie for Hamish Hamilton. Over several years she would translate hundreds of books, including Colette’s entire oeuvre, into English.

While her professional and artistic life was looking up, Antonia faced increasing difficulties with her daughters. Susan had returned home from Oxford University in spring 1948, on the verge of a nervous breakdown. While Antonia was very happy to nurse her, grateful for the opportunity to try and make up for some of her failings as a mother during Susan’s early years, her diaries at this time are full of uncompromising analysis of Susan’s character, and the perceived failings in her personality that had led her to this point.

Antonia, ever her own worst critic, could not help but dole the same out to her daughter. Susan returned to Oxford to finish her degree, but in spring 1951 attempted suicide by swallowing one hundred codeine tablets. ‘It was a dull job’, she later wrote, ‘and I read Of Mice and Men most of the night to pass the time.’

Her future husband, Thomas Chitty, found her in time and rushed her to the Radcliffe Infirmary. On her release from the hospital she moved back in with Antonia, only for Antonia to throw her out a few weeks later in a row over furniture. Within three weeks, Susan had married Thomas Chitty in a secret ceremony to which only Lyndall, Silas, and Silas’s new wife Sheila were invited.

Both Susan and Thomas sent Antonia letters informing her of their wedding, posted so that they would arrive when they were away on honeymoon. It was the beginning of estrangement, on Susan’s instigation, that would last for almost six years. Not until 1957 was some semblance of a relationship re-established.

Lyndall, meanwhile, had always felt that Antonia was jealous of both her and Susan, resenting both their beauty and any happiness that they might find with other people. But with Susan estranged, Antonia and Lyndall began to spend more time together and for a while, the shift comforted and healed them both. Lyndall later wrote that she ‘began to realize this person I had always feared as a monster was also a human being.’

. . . . . . . . .

Antonia White page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

The Sugar House was finished by the end of 1951 and published in summer 1952. Antonia felt it was her strongest book, with a vivid psychological understanding of her mental disintegration during the early 1920s. However, she was less sure about how it would be received, especially since the literary landscape was changing so rapidly.

Opinion seemed very set against religion in general and Catholicism in particular, and with the emergence of authors such as William Cooper and Kingsley Amis, the struggles of a young middle-class girl with sex and spirituality seemed outdated. She was proven somewhat correct when reviews were mixed; in her mind, they were some of the ‘most hostile I have ever had.’

The writing of the next novel began slowly, but by April 1954 she had finished Beyond the Glass. It was completed through a period of continued depression, and also while Antonia was incredibly busy with her translation work. This time the critics responded positively, and Antonia was pleased that the book brought her the recognition she felt she deserved.

But Beyond the Glass ended with Clara hesitating on the edge of life, just released from the asylum and unsure of where to go next, still entranced by the intensity of life in the grip of ‘the beast’ and unconvinced that a so-called sane world had anything comparable to offer. Antonia would struggle for the rest of her life to write the next stage of Clara’s journey, but was always unable to; at times the effort would drive her to the brink of madness again.

Her next literary endeavor were two children’s books starring her two Siamese cats, Minka and Curdy, acquired at the end of 1954. Antonia had always loved cats, and their antics provided her with joy and amusement for almost eighteen years.

‘Schoolmarm’ in America

In August 1958 Antonia received an unexpected invitation: to teach creative writing at St Mary’s, a Catholic girl’s school in South Bend, Indiana. Antonia agreed to go for a term, beginning in September 1959, and teaching a select group of twenty students.

Her time there, she wrote to Lyndall, opened her eyes to the possibilities of teaching; she came to love and admire her students and was admired and respected in return. She embraced the American way of life and was keen to try everything, including hot dogs and watching American football (for which she developed an unlikely but lasting passion).

‘I’m just immersing myself,’ she wrote to Emily Coleman, ‘love it, get bewildered, don’t mind, can hardly remember England…’ But by the end of term, she began to find that institutional life suited her less. She was uneasy around the nuns, and although they tried to persuade her to stay on, she left after the agreed term. After a period of traveling and sightseeing, she returned home in February 1960.

Ill health and writer’s block

Back in London, Antonia found herself unable to write, unsettled when her landlord forced the sale of her flat and was beset by health problems. By 1965 she was forced to see her doctor with swellings around her eyes, and further mental health issues resulted in a course of antidepressants (which she had never had before), and a stint as an outpatient at the Cassel Hospital in Richmond. But despite the pills and analysis, her depression would not lift, and grew worse after she had to have Curdy, one of her beloved cats, put down.

In October 1968 she endured the first operation for cataracts. She continued to try and work on translations that were due, conscious that she needed the money, but other health problems dogged her. She was now completely deaf without a hearing aid, and her sight never recovered sufficiently for her to feel confident walking out and about on her own.

A bout of double pneumonia sent her to hospital in December 1969. Although both daughters were abroad — Susan in Boston where Thomas had an academic job, and Lyndall in Italy — friends and old lovers, including Tom and Silas, rallied around. Her second cataract operation, unable to be postponed any longer, was scheduled for October 1970, but she contracted an eye infection afterward, which exacerbated her pain and prolonged her stay in the hospital.

In April 1971, after the vet diagnosed Minka with cancer, she also had to put her down. She was further depressed by seemingly constant news of the death of friends, but it was the deaths of Eric Earnshaw Smith later in 1971, and Emily Coleman in 1974, which affected her most deeply. In her grief, she turned once again to writing, accepting translations as they came along (including Voltaire and Simenon). She didn’t find much solace in her religion, only attending church on Sundays and Holidays of Obligation instead of her previous three times a week at Mass.

Virago and a resurgence in popularity

At the beginning of 1977, Antonia was introduced to Carmen Callil, a young Australian publisher who was running the feminist publishing house Virago and who would become a close friend to Antonia for the rest of her life. She was on the lookout for new publishing ideas, and a mutual friend (Michael Holroyd) suggested that she reissue Frost in May.

Carmen was enthralled by the book, and the idea for Virago Modern Classics was born. Frost in May was reissued in summer 1978, and was a brilliant success: television and radio rights were sold, and Carmen decided to also reissue the trilogy of Clara books. However, when she asked Antonia to write the introduction, writer’s block took hold once again and Antonia was unable to write even a sentence. Carmen, attempting to interview her to help the process along, ‘sat opposite her … and I watched pain so great overcome her it twisted her body.’ The interview was eventually completed, Carmen wrote the introduction herself, and Clara enjoyed the same resurgence in popularity as Nanda.

The final breakdown

In July 1978, Antonia suffered a mild stroke that affected her memory and her ability to talk, and further health problems followed in January 1979 when she was confirmed as having bowel cancer. She commenced intensive radiotherapy treatment, but her physical condition deteriorated rapidly.

Conscious of the state she was in, she decided that she wanted to rewrite her will; it had changed several times over the years as her relationship with her daughters first declined and then improved. Now, given the resurgent success of her books, she wanted to determine once and for all the issue of who would act as literary executor.

Previously, the choice had been Susan, but she now changed it so that Carmen, Susan, and Lyndall were joint literary executors. Lyndall, however, renounced most of her claim to Antonia’s financial estate, saying that Susan now had four children and needed the money far more. This reworking of the will, although well-intentioned, caused huge problems later on when the executors couldn’t agree.

In October 1979, Antonia moved from her London flat into a Catholic nursing home in Sussex, close to Susan and Thomas’s home. There, her mental and physical condition went rapidly downhill. The old guilt and fear associated with her Catholicism violently resurfaced, and friends who visited were shocked at the terror they saw in her eyes. She no longer recognized either of her daughters and died in her sleep, on April 10, 1980.

Two daughters, two memoirs

After Antonia’s death, her literary legacy was assured thanks to Carmen and Virago. Her personal legacy, however, was not such a happy one. Both Susan and Lyndall embarked on memoirs of their mother, which inevitably generated competition between them and dredged up old, painful, and often very different memories.

When Susan’s memoir Now To My Mother: A Very Personal Memoir of Antonia White was published in 1985, Lyndall wrote to a couple of newspapers to point out some inaccuracies in quotes from Antonia’s diaries, and also to deny Susan’s claim that Lyndall, too, had hated their mother in childhood.

By the time Lyndall’s memoir was published (Nothing To Forgive: A Daughter’s Life of Antonia White, 1988), the relationship between the sisters had broken down completely. Only one task remained, the editing of Antonia’s diaries for publication, and they could not agree on who should do it.

Lyndall and Carmen argued that Susan was clearly too biased and that no daughter whose relationship with her mother had been so troubled could possibly undertake such a monumental task. Susan argued that she wrote biographies professionally, and besides, couldn’t afford to pay someone outside the family to do it. Eventually, Susan took legal action, and as the sole financial beneficiary under Antonia’s will, won her case. The diaries, edited completely by her, appeared in two volumes in 1991 and 1992.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is an author, poet, and artist with a serious case of wanderlust. She is originally from the UK, but has spent time abroad in Europe, the United States and the Bahamas.

When not traveling or working on her current projects — a chapbook of poetry, “The Cabinet of Lost Things,” and a novel based on the life of modernist writer and illustrator Djuna Barnes — she can be found with her nose in a book, daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Visit her on the web at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Antonia WhiteMajor works (selected)

Frost In May (1933; republished by Virago 1978)The Lost Traveller (1950; republished by Virago 1979)The Sugar House (1952; republished by Virago 1979)Beyond the Glass (1954; republished by Virago 1979)Strangers: Short Stories (1954; republished by Virago 1981)The Hound and the Falcon (1965; republished by Virago 1980)As Once in May (1983)Biographies

Now To My Mother: A Very Personal Memoir of Antonia White by Susan Chitty (1985)Nothing To Forgive: A Daughter’s Life of Antonia White by Lyndall Passerini Hopkinson (1988)Antonia White: Diaries (Vol.1 1926-1957, Vol. 2 1958-1979), ed. by Susan Chitty (1991-1992)Antonia White: A Life, by Jane Dunn (1998)More information

Wikipedia Reader discussion on Goodreads London Review of Books A Gimlet Eye Beneath a Chapel Veil (a review of Frost in May). . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Antonia White, author of Frost in May appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

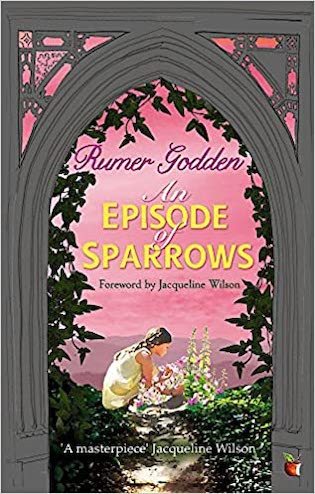

An Episode of Sparrows by Rumer Godden (1956)

This analysis of Rumer Godden’s 1956 novel, An Episode of Sparrows, features its tenacious young heroine, Lovejoy Mason. Excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

Growing up in the colonial era, like the family in Rebecca West’s The Fountain Overflows are the sisters Bea and Harriet in The River, 1946, set in what was then Bengal by Rumer Godden (1907–1998), who herself grew up partly in India. Like many of the girls in these semi-autobiographical novels, Harriet wants to be a writer when she grows up.

“The middle finger of Harriet’s right hand had a lump on the side of it; that was her writing lump; she had it because she wrote so much, because she was a writer. ‘I am going to be a poet when I grow up,’ said Harriet; and she added, after another thought, ‘Willy-nilly.’ She kept a private diary and a poem book hidden in an old box that also did as a desk in an alcove under the side-stairs, her Secret Hole, though it was not secret at all and there was no need to hide her book because she could not resist reading her poems to everyone who would listen.”

Is it meant to be a children’s book?But despite having been educated at what is now the very posh Roedean School on the South coast of England and having then spent much of her working life teaching dancing in India, Godden wrote a coming-of-age novel about the contrast between middle-class orthodoxy and poverty on the streets of wartime London: An Episode of Sparrows, 1956, which was made into the film Innocent Sinners, 1958. An Episode of Sparrows has been reissued several times as a children’s book, though it is not obvious that this is what it is meant to be. In her introduction to the Virago edition, Jacqueline Wilson says:

“I’m not sure if Rumer Godden wrote An Episode of Sparrows for children or for adults. It was originally published on an adult list but I read it when I was about ten, Lovejoy’s age. She’s the heroine of this book, a small, strong-willed little girl with the tenacity and determination of twenty adults.

She’s got a feckless mother, no father at all, and scarcely any friends. It’s not perhaps surprising. Lovejoy is fierce and selfish because she’s had to learn to be tough to survive. She snatches, she steals, she’s witheringly scornful if she doesn’t like anyone. I knew as I read the book that I’d be very wary of Lovejoy in real life – but even so, I cared about her passionately.”

A post-war London settingAn Episode of Sparrows is set in post-war London, on the borderline between a genteel, middle-class area and the much poorer houses nearby. Catford Street is on the poorer side, though it has working-class solidarity, making it rather like an urban version of the villages in Peyton Place by Grace Metalious and Shirley Jackson’s The Road Through the Wall. ‘Though Catford Street was in London it was a little like a village; to live in it, or the Terrace, or Garden Row, off it, or in any of the new flats that led off them, was to become familiar with its people.’ The children are a particular feature of the street, and especially of the novel.

“It was a strange thing that up to the age of seven children were noticeable in Catford Street; the babies in their well-kept perambulators and the little boys and girls in coat and legging sets were prominent, but after the age of seven, the children seemed to disappear into anonymity, to be camouflaged by the stones and bricks they played in; as if they were really the sparrows the Miss Chesneys called them they led a different life and scarcely anyone noticed them.

At fourteen or fifteen they appeared again, the boys as big boys that had become somehow dangerous – or was it that there was too much about them in the papers? – the dirty little girls as smart young women, with waved hair, bright coats, the same red nails and lipstick as the dancer in the bus queue; they wore slopping sling-back shoes and had shrill ostentatious voices.”

. . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

Girls in Bloom on Amazon UK*

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

As Jacqueline Wilson says, Lovejoy Mason, although only eleven years old, is a terrific character. Her mother is a musical singer on the stage, a coloratura, as Lovejoy says and is almost constantly away. She has left her daughter in the hands of the kind and caring but financially imperiled Mrs. Combie, whose husband is ruining them by attempting to open a gourmet restaurant in entirely the wrong part of London.

It is clear to the reader and to Mrs. Combie that Lovejoy’s mother prefers the company of men to that of her own daughter; she promises to come but doesn’t and promises to send money but doesn’t do that either. Lovejoy for her is very much out of sight and out of mind.

“It would have surprised Lovejoy’s mother, Mrs Mason, to be told that Lovejoy never had any pocket money; Mrs Mason was always going to give her some but, somehow, it was always spent. ‘I meant you to have an ice-cream,’ she would say to Lovejoy in the teashop or café, ‘but, look, I’ve only got sixpence for a coffee. Never mind. You can have the biscuit.’”

On the rare occasions the mother does come to see her, she brings a man whom Lovejoy is told to call ‘uncle’ and is gone again almost as soon as she came. Lovejoy has still not learned how to turn herself into stone, how to live without a mother in her life, still hopes her mother will come back permanently. When she stops, this will be her coming of age.

“The room still smelled of her mother; when Lovejoy burrowed her face against that spot on the armchair, instead of hard plush she seemed to be burrowing against the warm soft flesh she knew so well, that smelled of scent …”

Thievery and gardening

To make up for her loss, Lovejoy cynically and ruthlessly steals things, quite prepared to fight boys if she has to, though even she has her limits. ‘Lovejoy did not steal big things, nor money; she knew that to take money was wicked; nobody had told her that ice-creams and comics were money and she was adept in taking a parcel out of a perambulator while she pretended to rock it.’

But Lovejoy is no tomboy and is very fastidious in her dress, keeping her room and herself immaculate at all times, though her clothes have grown too small for her and her mother refuses to buy her any bigger ones. However, Lovejoy is not a pretty girl.

“She knew perfectly well she was not pretty; she had studied herself too often in the mirror to have any doubts about that; she had a certain fineness and lightness, dear little bones, thought Lovejoy, but her slant eyes and flat nose were not pretty.”

All protagonists in novels need a goal or quest; Lovejoy’s is to build a garden in the bombed out ruins of London, a private garden that no one else will have access to; a place for herself in the world, somewhere she will be found and not lost, if only by herself. (The symbolism of her garden is reminiscent of that of the tree growing in Brooklyn in Betty Smith’s novel.)

“She had never heard of a vortex but she knew there was a big hole, a pit, into which a child could be swept down, a darkness that sucked her down so that she ceased to be Lovejoy, or anyone at all, and was a speck in thousands of specks . . . She knew how easily that could happen because once she had been lost. I was only six then, thought Lovejoy; she was nearly eleven now but she had not forgotten it. She was lost and she was a speck and there was no-one. It had been when her mother was out of work and they were moving restlessly about.”

. . . . . . . . . .

An Episode of Sparrows on Bookshop.org*

An Episode of Sparrows on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

But even the few pennies Lovejoy needs to buy seeds and the most primitive of garden tools are hard to come by; she resorts to stealing from the candle box at the Catholic Church but she comes to be frightened of the statue of the Virgin Mary staring down at her; ‘it never looked at her, always into her, and she wriggled uncomfortably because, unaccountably, it seemed to find something in Lovejoy that matched it. How did it know that inside the hard tough Lovejoy was something as gentle as those eyes?’ Tip, the boy Lovejoy gets to help her, forces Lovejoy to repay the money as penance.

The first garden Lovejoy makes is destroyed by the boys who think she is encroaching on their territory but she and her friends find an enclosed, secret space behind the church and start to build again; ‘Lovejoy had never heard the word “sanctuary” but she knew she had found a safe place.’

“To Lovejoy it was very far from play. When the last bucket was tipped out and she saw the two flowerbeds filled with fine black earth, good garden earth, she had a feeling of such triumph and satisfaction as she had never known. ‘Who plants a garden plants happiness,’ says the Chinese proverb. In that moment Lovejoy was absolutely happy.”

But things soon take a turn for the worse. First, Tip is arrested for stealing the earth for the garden. His family prevent Lovejoy from seeing him.

“Lovejoy had thought she knew what it was like to be shut out; she had been alone when she was lost, alone lying waiting for her mother in bed, and sitting on the stairs while the gentlemen were in the room; she had learned to manage without her mother, for a long time now she had ‘counted her out’, thought Lovejoy, but there had always been someone, Vincent, Mrs Combie, then Tip. Tip! Lovejoy twisted her hands together as she looked at the closed door, gave a strangled little gulp and fled down the Street.”

“Mary, make me cocky and independent”And then it turns out that Lovejoy’s mother is not coming back; she has not been with the singing troupe she claimed and owes money everywhere, even to her own agent. The Juvenile Court very kindly try to find Lovejoy somewhere to live as Mrs Combie refuses to keep her on, now knowing that there will be no more money from her mother.

”It’s not that she’s not a good child, sir,” said Mrs Combie, coming back to the Chairman, “she is, but she has ideas.” Mrs Combie spoke as if that were a disease.’ Lovejoy must go to the Home of Compassion, a home for orphan girls run by nuns, but makes one last attempt to persuade Mrs Combie, and in particular her sister Cassie, who has always disliked Lovejoy.

“‘I’d work for you,’ said Lovejoy hoarsely. ‘Even when I’m grown up. I’d work and give you all the money.’

‘Shouldn’t we think of the story of the good Samaritan?’ Mrs Combie had asked Cassie, and Cassie had said, ‘In the story of the good Samaritan Lovejoy would have been the thief.’

Mrs. Combie stirred her tea and looked firmly at the tablecloth, but in spite of Cassie a great lump came in her throat.

‘Please keep me,’ said Lovejoy.

‘We can’t even keep ourselves,’ said Mrs. Combie incoherently and she burst into tears.”

And they can’t. The restaurant her husband so lovingly built up is closed and all the furnishings sold. In the Home of Compassion the nuns are quite kindly towards Lovejoy, but she does not have her own room and hates the clothes they give her. Lovejoy sells the clothes and buys fashionable new ones but they are taken away; ‘“that spirit must be broken. . . You must learn to do as you’re told,” Angela told Lovejoy. “You’re far too cocksure and independent.”. . . “Hail, Mary,” prayed Lovejoy between her teeth. “Mary, make me cocky and independent.”’

. . . . . . . . . .

More about An Episode of Sparrows Wikipedia “The First Book that Made Me Cry” Reader discussion on Goodreads Original review on Kirkus Reviews. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post An Episode of Sparrows by Rumer Godden (1956) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Ántonia Shimerda: Singular Heroine of Willa Cather’s My Ántonia

This character analysis of Ántonia Shimerda, the heroine of My Ántonia by Willa Cather (1873-1947) is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

My Ántonia (1918) is the third of Willa Cather’s Midwestern pioneer novels (often referred to as the Prairie Trilogy) of early twentieth century frontier life which, despite their brevity, manage to encompass the epic sweep of the pioneering move to the West, seeming to hark back to an earlier era of rugged individualism.

Despite the title, Ántonia (the Shimerda family have come from Bohemia; all Czech names have the stress on the first syllable, hence the accent over the Á) is not the narrator nor even the central character; she is always slightly off to one side and a little out of focus.

Nevertheless, this is a true coming of age story; at the end it fast forwards to Ántonia being a middle-aged woman having had a large number of children, but not with the narrator: despite the title, she is not and never has been ‘his’ Ántonia.

A family in Nebraska Territory

Unusually, a female author uses a male narrator: Jim Burden, ten years old at the start of the novel – Ántonia is two years older – to tell the story of his and other immigrant families, mostly newly arrived from Europe, settling in the virgin territory of Nebraska. The Shimerdas have been tricked by a relative into paying too much for unfit, unusable land, animals and dwellings; at first they live in not much more than a hole in the ground.

Ántonia’s father cannot reconcile himself to this hard new life; he has been a respected musician in Bohemia but is now reduced to extreme poverty. He kills himself after one misfortune too many.

After their father’s death, Ántonia’s older brother Ambrosch becomes the head of the family and tries, in his own way, to protect her. When she gets a job as cook for a neighboring family, the brother fights to stop her from becoming independent.

“They had a long argument with Ambrosch about Ántonia’s allowance for clothes and pocket-money. It was his plan that every cent of his sister’s wages should be paid over to him each month, and he would provide her with such clothing as he thought necessary. When Mrs Harling told him firmly that she would keep fifty dollars a year for Ántonia’s own use, he declared they wanted to take his sister to town and dress her up and make a fool of her.

Mrs Harling gives a lively account of Ambrosch’s behavior throughout the interview; how he kept jumping up and putting on his cap if he were through with the whole business, and how his mother tweaked his coat-tail and prompted him in Bohemian. Mrs Harling finally agreed to pay three dollars a week for Ántonia’s services – good wages in those days – and to keep her in shoes. There had been hot dispute about the shoes, Mrs Shimerda finally saying persuasively that she would send Mrs Harling three fat geese every year to ‘make even.’ Ambrosch was to bring his sister to town next Saturday.

‘She’ll be awkward and rough at first, like enough,’ grandmother said anxiously, ‘but unless she’s been spoiled by the hard life she’s led, she has it in her to be a real helpful girl.’

Mrs Harling laughed her quick, decided laugh. ‘Oh, I’m not worrying, Mrs Burden! I can bring something out of that girl. She’s barely seventeen, not too old to learn new ways. She’s good looking too!’ she added warmly.”

. . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

Girls in Bloom on Amazon UK*

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

The narrator, Jim, tells us how good it is ‘to have Ántonia near us again; to see her every day and almost every night!’ But he does not seem to have, and certainly does not convey to Tony, as he sometimes calls her, any romantic or sexual desires towards her, even though he is ‘jealous of Tony’s admiration for Charley Harling.

Because he was always first in his classes at school, and could mend water-pipes or the door-bell and take the clock to pieces, she seemed to think him a sort of Prince. Nothing that Charley wanted was too much trouble for her.’

Jim’s family move from the relative wilderness of the open fields to the relative civilization of the nearest nearby town, Black Hawk. All this is happening just at the time in American history where the Europeans who had first tamed the wild plains of states like Nebraska were Europeanizing the frontier. This is America’s bildungsroman as much as Ántonia’s, the story of the journey from virgin to sophisticate, from wild to tamed, from ingenuous to knowing, innocent to cynical, unstoried to storied. Much is gained, and much is lost in that journey.

“There was a curious social situation in Black Hawk. All the men felt the attraction of the foreign, well-set-up country girls who had come to town to earn a living, and, in nearly every case, to help the father struggle out of debt, or to make it possible for the younger children of the family to go to school.

These girls had grown up in the first bitter-hard times, and had got little schooling themselves. But the younger brothers and sisters, for whom they made such sacrifices and who have had ‘advantages,’ never seem to me, when I meet them now, half as interesting or as well educated. The older girls, who helped break up the wild sod, learned so much from life, from poverty, from their mothers and grandmothers; they had all, like Ántonia, been early awakened and made observant by coming at a tender age from an old country to a new.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

A 1918 review of My Ántonia

. . . . . . . . . . .

From time to time, traveling entertainers set up a tent in the town where they stage plays and hold dances. ‘Ántonia talked and thought of nothing but the tent.’ This changes not only Ántonia – formerly a total innocent – but men’s attitudes to her. She has come of age from girl to woman in their eyes.

“Ántonia’s success at the tent had its consequences. The iceman lingered too long now, when he came into the covered porch to fill the refrigerator. The delivery boys hung about the kitchen when they brought the groceries. Young farmers who were in town for Saturday came tramping through the yard to the back door to engage dancers, or to invite Tony to parties and picnics.”

Mr Harling, acting, like her own brother, in loco parentis, tells her she must stop. ‘This is what I’ve been expecting, Ántonia. You’ve been going with girls who have a reputation for being free and easy, and now you’ve got the same reputation… This is the end of it, to-night. It stops, short. You can quit going to these dances, or you can hunt another place. Think it over.’

For him, as for most men, a girl can either be a shy virgin or a seductive siren; there is no middle ground. Ántonia decides to leave, she has been offered work in another house. Mrs. Harling tells her something has changed within her. ‘I don’t know, something has… A girl like me has got to take her good times when she can. Maybe there won’t be any tent next year. I guess I want to have my fling, like the other girls.’

The narrator himself seems to think that Ántonia is now available: he takes her home after the dance and tells her she must kiss him good night. ‘Why, Jim! You know you ain’t right to kiss me like that. I’ll tell your grandmother on you!’ He tells her that her friend Lena let him kiss her, ‘and I’m not half as fond of her as I am of you.’ Being two years older than Jim, Ántonia is more concerned about his future than he is for hers.

Jim does make good, ending up at Harvard. Ántonia on the other hand is tricked by the man she had been going out with into going away with him; he leaves her, pregnant, before they are married. She returns in shame though she is unbowed.

When he comes back from school Jim says to her, ‘since I’ve been away, I think of you more often than of anyone else in this part of the world. I’d have liked to have you for a sweetheart, or a wife, or my mother or my sister – anything that a woman can be to a man.’ She looks at him with her ‘bright, believing eyes,’ glad that he remembers her so fondly when she had disappointed him.

Life intervenes‘Ain’t it wonderful, Jim, how much people can mean to each other? I’m so glad we had each other when we were little. I can’t wait till my little girl’s old enough to tell her about all things we used to do.’ Jim tells her when he goes away again that he will come back, but he doesn’t; ‘life intervened, and it was twenty years before I kept my promise.’ By this time she is married to a poor but honest man from Bohemia and has a large number of children.

“Before I could sit down in the chair she offered me, the miracle happened; one of those quiet moments that clutch the heart, and take more courage than the noisy, excited passages in life. Ántonia came in and stood before me; a stalwart, brown woman, flat-chested, her curly brown hair a little grizzled. It was a shock, of course. It always is, to meet people after long years, especially if they have lived as much and as hard as this woman had. We stood looking at each other. The eyes that peered anxiously at me were – simply Ántonia’s eyes.”

. . . . . . . . .

More about My Ántonia by Willa Cather Wikipedia Reader discussion on Goodreads My Antonia scholarly edition (full text) Audio version on Librivox. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Ántonia Shimerda: Singular Heroine of Willa Cather’s My Ántonia appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 18, 2021

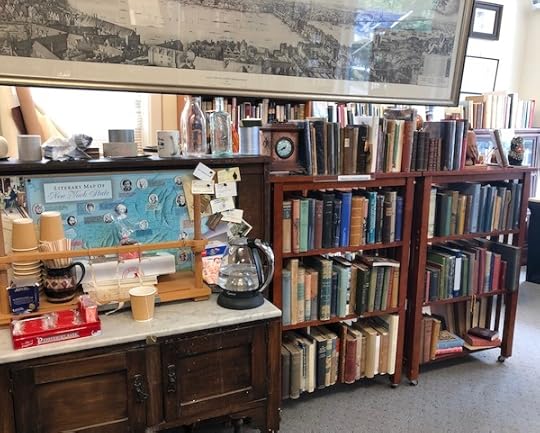

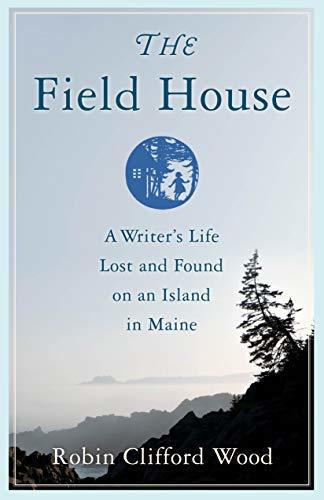

Hobart Book Village, a Bibliophile’s Dream in Upstate NY

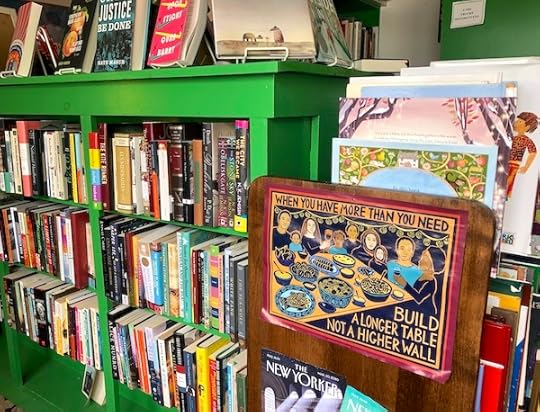

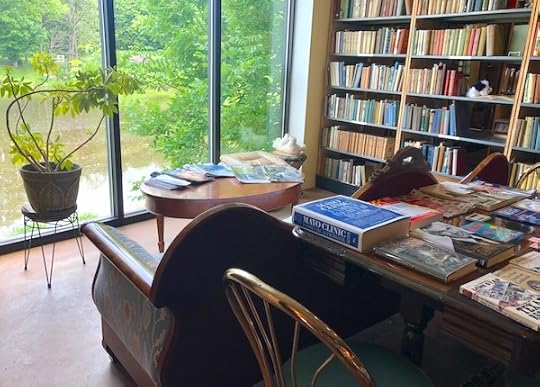

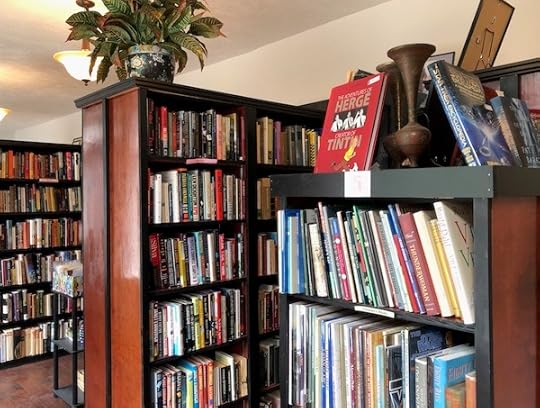

Have you ever heard of a book town or book village? Chances are you haven’t, if you live the U.S.; there are only three of them in all of North America. One of the most charming and accessible book towns is Hobart Book Village in upstate New York. (At right, a stack of books at LionEyes Books, which specializes in art books.)

It just so happens that Hobart, NY (Delaware County), one of North America’s rare book towns, is just a couple of hours from where I live in upstate New York. This book village was started in 2005 by local entrepreneur Don Dales; and while there has been a turnover in shops, the book village concept has been going strong in this hamlet for an impressive number of years.

The book town is a concept has caught on around the world, especially in Europe. It’s pretty much what it sounds like — a gathering of bookshops concentrated in the center of a small town or village.

Alex Johnson, the author of Book Towns elaborates:

“A book town is simply a small town, usually rural and scenic, full of bookshops and book-related industries. The movement started with Richard Booth in Hay-on-Wye in Wales in the 1960s, picked up speed in the 1980s and is continuing to thrive in the new millennium.

From the start, the driving force has been to encourage sustainable tourism and help regenerate communities … One important reason that almost all book towns are in bucolic locations is that they require cheap property to enable book businesses to open their doors. Many have been subsidized by local authorities to help them get off the ground. While many cities have numerous bookshops, book towns concentrate the outlets in a small area to create a critical mass.”

Web: Hobart Book Village

Main Street, Rt. 10, Hobart, NY 13788

Summer hours (starting June 1): Daily, 11-5. All other times of the year the village is mostly open on weekends; consult the website (above) for more details, or go directly to hours and directions.

Hobart Book Village’s website describes itself as having six bookshops, but I count eight (plus the Children’s Community Library). Whether six or eight, there’s plenty to keep book lovers busy for several enjoyable and relaxing hours.

NearbyHobart is tucked away in the beautiful Catskill mountains region of NY State, so make sure to consult Trip Advisor for more to do in the region as well as places to stay and eat.

The goodAll the bookstores are within close walking distance of one another, so you park once and you’re done.Each of the bookstores has something distinctive to offer, so that they don’t overlap too much. That makes each shop a different experience.All of the booksellers are super friendly and welcoming, happy to engage with fellow bibliophiles.There’s a mix of new and old books, and you’re likely to find some great bargains among the latter.You can visit two art galleries located amidst the bookstores. The Mural Gallery is one of them, though it’s only open on Saturdays from 12-4. An art gallery is part of one of the largest shops, Liberty Rock Books.Two huge sales: From the website — “Two huge semi-annual sales are held on the weekends of Memorial Day and Thanksgiving Day. These sales draw hundreds of collectors, book lovers, vacationers and local residents since it is a great way to stock personal libraries for the summer, fall and winter or kickstart Holiday shopping.”The not-so-goodA dearth of food; no coffee: There was no food or coffee place open in town during the hours I was there. I drove about a half mile to a gas station to get coffee and a snack. There’s just one place in the midst of the bookstores called The Dinner Plate, but it’s totally not vegan-friendly for someone like myself. I suppose I could have made do with a salad and a cheese-less pizza, but the place only opens at 4:00, the time when I wanted to start making the trek back. I suggest bring a picnic or stopping at a nearby town for food before hitting the bookstores. The adjacent town is Stamford, which has a few eateries. There are other options further afield as well.There’s no public transportation to Hobart; it’s only reachable by car.Festival of Women Writers

The goodAll the bookstores are within close walking distance of one another, so you park once and you’re done.Each of the bookstores has something distinctive to offer, so that they don’t overlap too much. That makes each shop a different experience.All of the booksellers are super friendly and welcoming, happy to engage with fellow bibliophiles.There’s a mix of new and old books, and you’re likely to find some great bargains among the latter.You can visit two art galleries located amidst the bookstores. The Mural Gallery is one of them, though it’s only open on Saturdays from 12-4. An art gallery is part of one of the largest shops, Liberty Rock Books.Two huge sales: From the website — “Two huge semi-annual sales are held on the weekends of Memorial Day and Thanksgiving Day. These sales draw hundreds of collectors, book lovers, vacationers and local residents since it is a great way to stock personal libraries for the summer, fall and winter or kickstart Holiday shopping.”The not-so-goodA dearth of food; no coffee: There was no food or coffee place open in town during the hours I was there. I drove about a half mile to a gas station to get coffee and a snack. There’s just one place in the midst of the bookstores called The Dinner Plate, but it’s totally not vegan-friendly for someone like myself. I suppose I could have made do with a salad and a cheese-less pizza, but the place only opens at 4:00, the time when I wanted to start making the trek back. I suggest bring a picnic or stopping at a nearby town for food before hitting the bookstores. The adjacent town is Stamford, which has a few eateries. There are other options further afield as well.There’s no public transportation to Hobart; it’s only reachable by car.Festival of Women WritersHobart is also known for its annual Festival of Women Writers and its winter workshops. Get all the information here.

The bookshops and more (as of summer 2021)

Adams Antiquarian Books (602 Main Street) features three floors of organized and and attractively displayed books, giving it the feel of so much more than just one bookshop. This treasure trove was the first bookshop opened in Hobart Book Village. From the brochure: “Featuring fine books, art, and tea offered in a bright, cordial atmosphere that makes both the collector and the browser feel welcome. Featuring 17th, 18th, 19th, and 20th century: Fiction, Biographies, Art, Music, Theatre, Dance, Etiquette, Graphic Arts, Poetry, Greek and Latin Texts, Theology, Science, Natural History; American, World; and Local History.”