Nava Atlas's Blog, page 32

November 9, 2021

The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Highsmith (1956)

The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Highsmith is a 1956 novel introducing Thomas Ripley, the sociopathic anti-hero who went on be the central character of four subsequent books. The five novels came to be known as “the Ripliad.” The first installment was followed by Ripley Under Ground, Ripley’s Game, The Boy Who Followed Ripley, and Ripley Under Water.

Like many of Highsmith’s characters, Tom Ripley is a con artist and murderer. Highsmith described him as “suave, agreeable, and utterly amoral.” He’s cultured, charming, and often portrayed as likable, which puts the reader in a moral bind — just as the author intended.

The following synopsis from Amazon is by Patrick O’Kelley:

“One of the great crime novels of the 20th century, Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley is a blend of the narrative subtlety of Henry James and the self-reflexive irony of Vladimir Nabokov.

Like the best modernist fiction, Ripley works on two levels. First, it is the story of a young man, Tom Ripley, whose nihilistic tendencies lead him on a deadly passage across Europe. On another level, the novel is a commentary on fiction-making and techniques of narrative persuasion. Like Humbert Humbert, Tom Ripley seduces readers into empathizing with him even as his actions defy all moral standards.

The novel begins with a play on James’s The Ambassadors. Tom Ripley is chosen by the wealthy Herbert Greenleaf to retrieve Greenleaf’s son, Dickie, from his overlong sojourn in Italy. Dickie, it seems, is held captive both by the Mediterranean climate and the attractions of his female companion, but Mr. Greenleaf needs him back in New York to help with the family business.

With an allowance and a new purpose, Tom leaves behind his dismal city apartment to begin his career as a return escort. But Tom, too, is captivated by Italy. He is also taken with the life and looks of Dickie Greenleaf. He insinuates himself into Dickie’s world and soon finds that his passion for a lifestyle of wealth and sophistication transcends moral compunction. Tom will become Dickie Greenleaf—at all costs.

Unlike many modernist experiments, The Talented Mr. Ripley is eminently readable and is driven by a gripping chase narrative that chronicles each of Tom’s calculated maneuvers of self-preservation. Highsmith was in peak form with this novel, and her ability to enter the mind of a sociopath and view the world through his disturbingly amoral eyes is a model that has spawned such latter-day serial killers as Hannibal Lecter.”

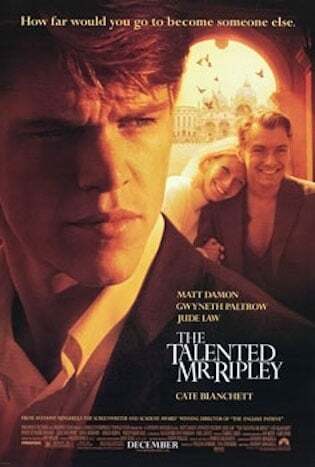

The Ripley novels were highly successful and well-reviewed (see a typical review from 1956 below). Some of the Ripley novels were made into feature film, the most notable of which was the 1999 adaptation starring Matt Damon as the title character.

A 2021 reconsideration ofThe Talented Mr. Ripley in the New York Times Magazine (a highly recommended read!) observed: “The task of making a heinous character sympathetic is the real work of many novels. Think of the criminal Humbert Humbert in Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita.” The novel was also known for its homoeroticism, which was rather bold for the era in which it was published.

. . . . . . . . . .

1999 film adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley

can be streamed on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

From the original review of The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Highsmith in the Bridgeport Telegram, February 1956. Tom Ripley, hero of this story by Patricia Highsmith, is indeed talented, in peculiar ways.

His are the talents which make a successful criminal ingenuity, a flair for luxury, the ability to turn any situation to his own benefit. A chance meeting in a New York bar becomes for him an avenue to easy living in Italy — on someone else’s money.

Curiously enough, he has few gifts beside the aforementioned, and few real interests. He has no friends of either sex; he is a completely self-centered individual who believes in taking what he can get.

Italian mission

As his Italian mission draws to a close, unaccomplished, Ripley soon sees that it has become necessary to turn to murder to secure a continuation of his very pleasant position. He is not one to blanch at such a necessity. Soon he is involved in the precarious business of covering up his tracks.

Having brought all his ingenuity into play, our hero is on the verge of safety when an unlucky break forces him to murder again. The Italian police are soon scouring the country for the criminal. But, due to some clever planning, they are now searching for the wrong man.

A manipulative sociopath

As the suspense swiftly mounts, Ripley boldly manipulates the principals in the dangerous plot to secure his skin. Painstakingly he builds up his proofs of innocence, adapting his actions to quick changes in the situation.

With great success the author builds up the tension which surrounds a hunted man. Readers of Highsmith’s other well-known novels of suspense will not be disappointed by The Talented Mr. Ripley.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Talented Mr. Ripley on Bookshop.org and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

“He loved possessions, not masses of them, but a select few that he did not part with. They gave a man self-respect. Not ostentation but quality, and the love that cherished the quality. Possessions reminded him that he existed, and made him enjoy his existence.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If you wanted to be cheerful, or melancholic, or wistful , or thoughtful, or courteous, you simply had to act those things with every gesture.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Mr Greenleaf was such a decent fellow himself, he took it for granted that everybody else in the world was decent, too. Tom had almost forgotten such people existed.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“He liked the fact that Venice had no cars. It made the city human. The streets were like veins, he thought, and the people were the blood, circulating everywhere.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Beyond Sicily came Greece. He definitely wanted to see Greece. He wanted to see Greece as Dickie Greenleaf with Dickie’s money, Dickie’s clothes, Dickie’s way of behaving with strangers. But would it happen that he couldn’t see Greece as Dickie Greenleaf? Would one thing after another come up to thwart him—murder, suspicion, people? He hadn’t wanted to murder, it had been a necessity.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“He hated becoming Thomas Ripley again, hated being nobody, hated putting on his old set of habits again, and feeling that people looked down on him and were bored with him unless he put on an act for them like a clown, feeling incompetent and incapable of doing anything with himself except entertaining people for minutes at a time.”

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like: Strangers on a Train by Patricia Highsmith

. . . . . . . . . .

More about The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Highsmith

Wikipedia Reader discussion on Goodreads A Close Reading of The Talented Mr. Ripley. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Highsmith (1956) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 7, 2021

Laura — the 1944 Film Based on the Novel by Vera Caspary

Laura, the 1944 film based on the 1943 novel of the same name by Vera Caspary, has earned a secure place among the finest of the film noir genre.

The novel remains Caspary’s best-known work, and its even better-known film version has been preserved in the U.S. National Film Registry of the Library of Congress for its significance. It was also named as one of the 10 best mystery films of all time by the American Film Institute.

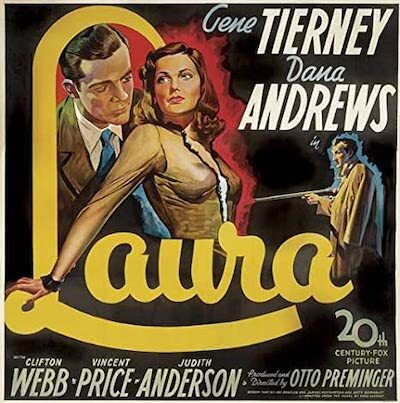

Produced and directed by Otto Preminger, Laura starred Gene Tierney in the title role. The three men involved in Laura’s life and subsequently purported death are Dana Andrews as detective Mark McPherson, Vincent Price as Laura’s playboy fiancé, and Clifton Webb as newspaper columnist Waldo Lydecker, a Svengali figure who is possessive of his protege.

Plot summary

Laura Hunt, a beautiful and successful New York City advertising executive, has been murdered in her apartment, her face rendered unrecognizable by a direct shotgun blast. The NYC police department has assigned detective Mark McPherson to investigate the case.

He sets out to grill the people in Laura’s life — Waldo Lydecker, the pompous columnist who could boast of using his clout to launch Laura’s career in its early stages; her ineffectual fiancé, Shelby Carpenter, who is also might be construed as a gigolo for her wealthy aunt, Ann Treadwell; and Bessie, Laura’s loyal housekeeper.

Reading Laura’s letters, getting to know her through her friends, and gazing at the portrait of her in her lovely Manhattan apartment, Detective McPherson seems to be falling in love with the dead woman. The twist comes as he rests and ponders one night after poking around in her apartment — in walks Laura, very much alive.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Ultimate Caspary Woman: Laura by Vera Caspary

. . . . . . . . . .

Who was the murder victim, then? Why was she in Laura’s apartment wearing Laura’s robe, and who was she with?

It’s quickly revealed (and this is not a spoiler, as this is still about mid-film) that the victim was Diane Redfern, a down-on-her-luck model whose height and coloring match Laura’s. She was using the apartment with Laura’s permission, and as it seems, was likely canoodling with Shelby.

Laura quickly goes from presumptive murder victim to prime suspect. She is even arrested by McPherson, who is struggling to remain unbiased given his growing feelings for her. Shelby, who possesses a gun, and Lydecker, with his overbearing personality, remain under suspicion.

To say any more would be to reveal spoilers; if the gist of storyline intrigues you, the movie is available to watch on various streaming platforms. But do read the book first. What can’t be captured on film is the book’s shifting perspective between the main characters. Each tells their version of what happened in the first person, a device that inspired Caspary from Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White.

. . . . . . . . . .

One of several posters for the 1944 film

. . . . . . . . . .

Though Laura is sometimes classified in the femme fatale genre, this isn’t accurate. The eponymous heroine is a smart, hardworking, independent woman (her dicey taste in men aside), and the prototype for what Francis Booth calls “the ultimate Caspary woman.”

The following insights into how Laura went from page to screen is excerpted from the forthcoming No One Named Vera Can Ever Tell a Lie: The Novels of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth (reprinted by permission):

Caspary had intended to try to get Laura staged as a play, having given up on Hollywood, and did in fact write the script with collaborator George Sklar. Then Otto Preminger came along. It didn’t go well. Caspary told her side of the story in an article for The Saturday Review of June 26, 1971, called “My ‘Laura’ and Otto’s.’’

Hollywood’s indifference did not break my heart, as I was working on the play at the time. The first draft had been a play that I had buried for almost two years before I wrote the novel. The book was constructed like a play, its scenes dramatically structured, the characters exposed in action, so I thought it a natural for the stage.

Meanwhile, my agent, Monica McCall, who was handling the dramatic rights, had given a typescript of the book to a Broadway producer and director. He liked the story and wanted not only to produce it but to collaborate with me on the revised play. I was flattered because he had a Broadway reputation, because he offered all of his Middle European charm along with an elegant lunch of blinis and caviar. His name was Otto Preminger.

But Preminger “wanted to make it a conventional detective story; I saw it as a psychological drama about people involved in a murder. We fell out over this, and I asked my old friend and collaborator George Sklar to work with me.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Lydecker, Detective McPherson, and Laura’s portrait

. . . . . . . . . .

Preminger also wanted Marlene Dietrich to play Laura, which Caspary disagreed with. In the end, despite all the work she and Sklar had put into the play, she rang George one night to say she had decided what to do: “I’m going to offer Laura as a movie and be done with the bitch.”

As part of the contract, she handed over all creative responsibilities to Preminger. When she saw the first version of the script, she wished she hadn’t. She was nowhere near done with the bitch yet. Caspary continues the story in her autobiography.

Ordinarily, authors of books, plays, and original stories are not allowed to read screenplays. Perhaps because I was working for the studio and came twice a week to talk to my producer, Preminger gave me the first draft to read; perhaps because he wanted to show me how he had improved the story.

I had signed away the right to be indignant, but I forgot this and stormed into Preminger’s office. Preminger and the first writer had made it into exactly what I had objected to when Preminger had first offered to write the play with me.

“A commonplace detective story,” I ranted, “and how you’ve dulled the characters, especially Laura.” “In the book,” said Otto, “Laura has no character. She’s nothing, a nonentity.” I raged like a shrew.

. . . . . . . . . .

Dana Andrews and Gene Tierney in Laura

. . . . . . . . . .

His “well-publicized conquests had taught Mr. Preminger little about women, nothing about the maternal instinct, nothing of a woman’s satisfaction in consoling a troubled man.” Preminger had no appreciation of the qualities of a Caspary girl; probably no one in Hollywood did. “Naturally I resented Preminger’s turning her into the Hollywood version of a cute career girl.”

Caspary is, perhaps disingenuously, astonished at a top Hollywood producer’s lack of understanding of the strong, self-sufficient woman. “Couldn’t Otto understand that a woman could be generous, find jobs, lend money to a man without thought of paying for his sexual services?” No, he couldn’t.

But this was not the end of the matter: before shooting, the script was extensively revised, without Caspary’s knowledge or help, and ended up as something that even she liked.

He would never admit that the script was rewritten after our fight, but to me, this was obvious since the charm, the gaiety, the brilliant humor of the finished film (lacking in the version I read) could only have been the work of Samuel Hoffenstein, distinguished as a wit long before he came to Hollywood. This was not the end of my battle with Preminger.

It wasn’t. Preminger would reappear later, involved in The Murder at the Stock Club. But he hadn’t changed his mind about women.

. . . . . . . . .

Laura (the 1943 novel) by Vera Caspary

on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Laura — the 1944 Film Based on the Novel by Vera Caspary appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 4, 2021

Discovering Hazel Hall, “The Emily Dickinson of Oregon”

Hazel Hall (1886 –1924) was an American poet much beloved in her adopted state of Oregon. She was often referred to, for various reasons, as “The Emily Dickinson of Oregon.” Though she has been widely anthologized on both sides of the Atlantic, she’s no longer well known, yet deserves another look.

>By 1910, the city of Portland, Oregon was a lively city of commerce and community. An active population of well over 207,000 established it as the largest city in the Pacific Northwest. From the port side along the Ocean-accessible Columbia River to the West Bank of the roaring Willamette, people spent their days working in factories, window-shopping, strolling hand-in-hand, riding trolleys, and bustling about in all the ways that folks in large cities have always done.

Though Portland was host to much lively activity and trade, young Hazel Hall couldn’t take part in any of it. Being confined to a wheelchair from the age of twelve, she sat in the upper room of her home watching life in its myriad of shapes and sizes parade before her.

With her limited mobility, Hazel couldn’t stand up to peer out her window, so she fashioned a hand-mirror in such a way as to be able to view the streets below in the reflection of the glass.

Hazel Hall was born on February 7, 1886 in St. Paul, Minnesota to Montgomery and Mary Garland Hall. She had two sisters, Ruth and Lulu. The family moved to Portland, Oregon when Hazel was yet a toddler. Though young Hazel romped and played just as exuberantly as any other child, she fell ill with scarlet fever at age twelve. She was disabled ever afterward and confined to a wheelchair.

Not to be discouraged by her strict confinement, Hazel spent her days under the light of her window sewing and adorning fine linens and bridal robes, baby clothes, lingerie, Bishop’s cuffs, and christening gowns. These items were so beautifully embroidered that she became one of the favorite seamstresses of many of Portland’s social elite in the West Hills, bringing her money enough for her to earn her keep.

Hazel’s sister, Ruth, a librarian in the Portland School District, borrowed numerous books for Hazel to read. From classics to science, Hazel read everything that her sister brought home for her, but developed a particular interest in poetry. Emily Dickinson, who passed away the same year of Hazel’s birth, was counted among her favorite poets, along with Robert Frost and Edna St. Vincent Millay.

Hazel had always occupied herself by writing and by the age of 30, her work was published in the Boston Evening Transcript. Her poem, To An English Sparrow is a cadent piece of rhyme and meter deep in feeling. The life of the poem resembles the life of a sewing needle, which Hall knew the ins and outs of very well.

To an English Sparrow (excerpt)

Little feathered tufts of gray,

Skipping blithely through the day —

Never resting,

Yet protesting

In your querulous, quick way —

Little sparrow;

You who would the woodland spurn —

Bird-prized haunts of leaf and fern —

Ever grace the crowded street,

Seeking man’s companionship

With your chippy-chip chip chirp—

On your wing or tripping feet —

Ever lightly

Always sprightly

Comes your note so nearly sweet,

English sparrow

Following the success of having a poem published in The Boston Evening Transcript, Hazel Hall’s poems appeared in such prestigious magazines as The Century Magazine, Harpers Magazine, The New Republic, The Nation, Yale Review, and Literary Review.

In 1920, Hazel’s poem, Three Girls, was chosen as one of the five best poems of the year by critic William Stanley Braithwaite.

Three Girls

Three school girls pass this way each day,

Two of them go in the fluttery way

Of girls, with all that girlhood buys:

But one goes with a dream in her eyes.

Two of them have the eyes of girls

Whose hair is learning scorn of curls,

But the eyes of one are like wide doors

Opening out on misted shores,

And they will go as they go today

On to the end of life’s short way;

Two will have what living buys,

And one will have the dream in her eyes.

Two will die as many must,

and fitly dust will welcome dust;

But dust has nothing to do with one—

She dies as soon as her dream is done.

Acquiring only a fifth grade education before becoming fettered to a wheelchair failed to prevent Hazel Hall from reaching out to a world in which she couldn’t fully participate. With her poetry, she managed to inspire not only poetic appreciation, but also admiration for the simpler things that life brings one’s way.

Hazel’s interest in philosophy inspired her to think deeply about humanity and helped her to resist the temptation to become overwhelmed by her circumstances. In many ways it was her circumstances which she considered to be advantageous to writing poetry, for the solitude that she experienced aided in not only thinking through iambs and meters, but also in creating artistic presentations of the seemingly routine.

. . . . . . . . . .

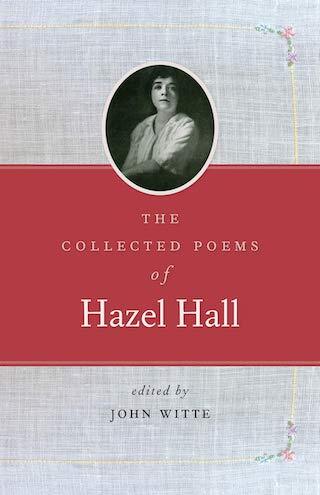

The Collected Poems of Hazel Hall on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Many of her poems were included in numerous anthologies, gaining her popularity even in England. Her first book, Curtains, was published in 1921, her second book, Walkers, in 1923. In 1928 her third book, Cry of Time, would be published posthumously by her sister, Ruth. A group of her needlework poems within the pages of Curtains gained Hall the Young Poets Prize from Poetry magazine.

When Hazel’s eyesight began to fail her, she no longer wrote poetry about sewing, as she did in Curtains, but instead began to write more about the things she spied from the confines of her room. Thus, Walkers, came to be.

The editors of The Bookman literary journal gave Hazel’s newest book much praise within its pages of the August 1923 issue, calling the poems “genuine, individual, and very lovely,” including in their review a quote from her poem, Protection:

I have envied, I have pitied

Wrapped their sorrows over me

Like a shawl, to keep from knowing

Cold that is colder than the sea.

At the age of thirty-eight, Hazel Hall succumbed to an illness and passed away in the family home. Within eight short years, from 1916 to 1924, she had managed to touch the hearts of many readers with her poems. Upon her death on May 11, 1924, her obituary was on the front page of the Oregonian newspaper with the headline:

“SWEET VOICE OF HAZEL HALL IS HUSHED BY DEATH.”

Yet, it wasn’t hushed for good, thanks to John Witte, English Professor at the University of Oregon. In 2000, Witte collected all three of Hazel Hall’s books into one volume and published (Northwest Readers) The Collected Poems of Hazel Hall, making it possible for her voice to continue ringing out loud, strong, and sweet, teaching us all how to live life as fully as we are able.

The Oregon Book Award for poetry is named for Hazel Hall and William Stafford (the Stafford/Hall Award for Poetry). The award’s sponsor, Literary Arts, referred to her as “The Emily Dickinson of Oregon.”

Hazel Hall’s home at 106 NW 22nd Place in Portland is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Hazel Hall House. In 1995 the Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission built a memorial park, or poetry garden, next to the Hazel Hall House. The park is home to three of her poems carved in granite; Light Sleep, Things That Grow, and The Listening Macaws.

Contributed by Tami Richards. This post was originally published on HerRhetoric. Reprinted with permission.

More about Hazel Hall Oregon Encyclopedia Re-reading Hazel Hall Academy of American Poets. . . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Discovering Hazel Hall, “The Emily Dickinson of Oregon” appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

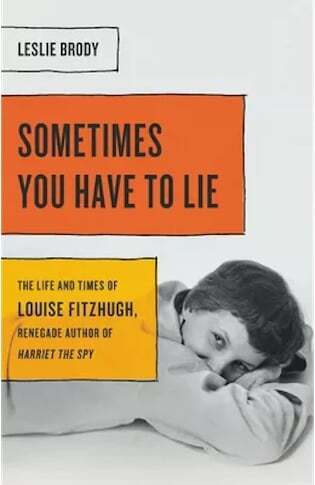

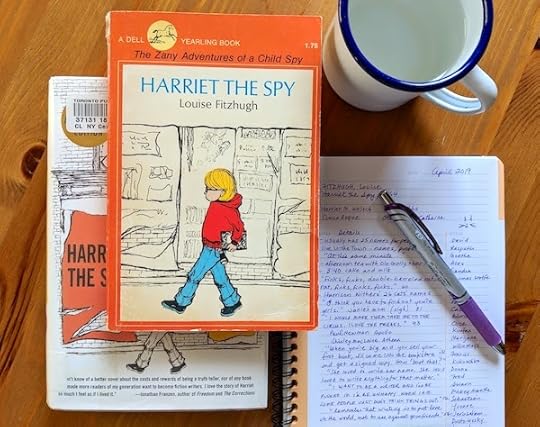

Sometimes You Have to Lie: The Life and Times of Louise Fitzhugh, Renegade Author of Harriet the Spy by Leslie Brody

It’s still so relevant—a writer with her mouth “open in horror all the time” at “the state of the world” and all the “social injustice, prejudice, and poverty” around her. That’s how Louise Fitzhugh describes feeling in the mid-1970s—toward the end of her life, in a letter to a friend—in Sometimes You Have to Lie: The Life and Times of Louise Fitzhugh, Renegade Author of Harriet the Spy (2020), a biography by Leslie Brody.

In the five years following its publication in 1964, Harriet the Spy sold about 2.5 million copies; that number nearly doubled by 2019. Decades have passed, but she remains relevant: readers continue to freshly fall for—and renew their acquaintance with—Harriet.

Leslie Brody did not grow up with Harriet; she “met” her when she was commissioned to adapt the novel for the stage in 1988: “I read it through several times, stunned at how lucky I was—after all this time, and the many ways our rendezvous might have gone awry—to find her.”

Louise Fitzhugh herself, conceived of Harriet in 1963, in the wake of disappointment after a gallery showing of her artwork: that’s when she started work on a children’s book featuring “a nasty little girl who keeps a notebook on all her friends.”

This disclosure is also from one of Louise Fitzhugh’s letters; Leslie Brody’s access to the author’s personal correspondence (and Brody’s own correspondence with Fitzhugh’s friends) fuels readers’ senses of intimate knowledge and understanding. It makes this biography feel revelatory and authentic, like Leslie Brody has peeked inside Harriet’s—I mean, Louise’s—notebook.

. . . . . . . . .

More about Louise Fitzhugh

. . . . . . . . . .

In the novel, even at eleven years old, Harriet was insistent on being Harriet: “Harriet was just so about a lot of things.” Her nursemaid Ole Golly introduces her to writers like Cowper, Emerson, James, and Wordsworth with his “inward eye which is the bliss of solitude” and encourages Harriet’s writing habit. But it’s a fine line between being alone and being lonely and, when the subjects of Harriet’s notebook discover its contents, Harriet must broaden her understanding of perspective.

In the 50th anniversary edition of Harriet the Spy, novelist Rebecca Stead explains Harriet’s enduring relevance: “What Harriet learns—painfully, necessarily—is that she can’t let every thought or observation escape onto the page. Some truths, Ole Golly explains … are just for ourselves. In other words, there are some kinds of loneliness we must learn to live with.” It’s challenging, it’s relatable.

Judy Blume is more succinct: “She had secrets; I had secrets. She was curious; I was curious.” Brody’s curiosity about Fitzhugh and her secrets fuels her biographical explorations; her gratitude for Harriet’s complexity infuses her research with enthusiasm. It’s both detail-oriented and narrative-driven.

It’s my favorite aspect of Sometimes You Have to Lie: the Harriet-ness of it all. Additional details are available in the endnotes and any readers with specific interests can employ the index, but Brody’s familiarity with—and respect for—Fitzhugh’s work adds a layer of satisfaction for Harriet fans.

. . . . . . . . . .

Sometimes You Have to Lie on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

In describing Fitzhugh’s younger years, for instance, Brody notes: “One of her favorite habits was sitting at the top of the stairs to listen in on the grown-ups at cocktail hour.” Biography devotees might find this interesting; Harriet fans will thrill to the glimpse of Harriet-in-young-Louise.

But I might have guessed this volume would prove fascinating for its Harriet-ness: the evolving relationships with agents and publishers, details about character names and journal-keeping and collaboration, other influential reading in Fitzhugh’s stacks (Harper Lee I might have anticipated, but Yeats?!), and decisions to pursue/abandon manuscripts featuring other characters in Harriet’s circle.

What I did not expect were the dedicated excavations of Louise Fitzhugh’s own circle of friends and colleagues (and lovers, both male and female), her privileged upbringing and parents’ personal histories, and the diverse nature of her creative pursuits.

Brody also devotes chapters to both Louise’s father (Millsaps Fitzhugh) and his privileged youth in Memphis, Tennessee, and her mother (Mary Louise Perkins) of Clarksdale, Mississippi. The court proceedings surrounding their divorce were concluded while Louise was very young, but they were so dramatic and scandalous that she would later learn all the details via archival newspaper coverage.

Even as a young reader, I understood that Harriet’s family possessed a status that mine did not, but I did not connect that to her author’s experiences.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh

. . . . . . . . .

The Fitzhugh family’s wealth created ample educational and social opportunities for Louise; although as she grew up, her interest in the former grew, she opted out of the latter. Her studies at Bard College “in the remarkably pretty Hudson River Valley” were as significant for providing “a radically different perspective on race, sex, and class” as for being “a peaceful refuge.” There, “the women of Bard wore ‘pants and jackets, lounging and smoking as men.’”

Before attending Bard, and “encountering some truly gifted poets” beginning with Jimmy Merrill, Louise herself had considered writing poetry. “It was never easy for her to dislodge her father’s acid observation that any literary work that wasn’t Tolstoy was hardly worth the trouble.”

She believed that “painting and poetry were at the top of the art pyramid, and that other forms of design and literature somehow counted for less.” (Even though I knew that Fitzhugh illustrated Harriet the Spy, Brody’s biography reveals how important drawing was for her.)

By 1950, Louise was living in Greenwich Village, “part of a bohemian enclave” as Brody describes it, which included people like writer Djuna Barnes, photographer Berenice Abbott, literary critic Anatole Broyard, playwright Lorraine Hansberry, and her particularly close friends Marijane Meaker and Sandra Scoppettone.

Much of the group, as the playwright and author Jane Wagner characterized it, was a network of “successful, creative, pleasure loving, ambitious, knowledgeable lesbians.” There, Fitzhugh “felt a safety in numbers against the judgment of the world.”

In 1961 she illustrated Suzuki Beane, a story that Sandra Scoppettone wrote, in an “age when sophisticated take-offs and spoofs were in fashion,” a response to characters like Kay Thompson’s Eloise. Fitzhugh also tinkered with one-act plays, like “The Butcher Shop” and “The Luncheonette,” which were also titles of paintings that she had exhibited at the Hudson Park branch of the New York Public Library in 1956.

Over time, Brody observes that Fitzhugh “became increasingly interested in surrealism” and created “more overtly satirical and political drawings with pioneers and cowboys to comment on the ‘national infatuation with violence and acquisition.’”

Creating power on the page

Brody’s observation about Fitzhugh’s reading while she wrote Harriet the Spy seems a suitable summary of Fitzhugh’s writing overall: “What these works ‘all have in common is their investigation into how the powerful connive to take advantage of defenseless individuals or marginalized groups.’”

When Fitzhugh read up on her parents’ divorce proceedings, she persistently returned to the idea that she was an afterthought, relegated to the margins in a situation that fundamentally shaped her future.

In contrast, Harriet creates her own power on the page (although it’s unexpectedly reflected against herself as the story unfolds). She consistently struggles to be an individual and to maintain her truth. “Kids who felt they were different could read parts of their secret selves in Harriet, relate to her refusal to be pigeonholed or feminized, and cheer her instinct for self-preservation,” Brody writes.

. . . . . . . . .

Playing Town: Revisiting Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy

. . . . . . . . .

I’m reminded of Michaela Coel’s Misfits (2021), which was in my stack alongside this biography. When she describes how a “misfit is one who looks at life differently” and also someone whom life looks at differently—not only do I think of Harriet but, now, also her author. (Who, ironically, was compelled to keep many secrets from public view, even as she expressed herself boldly in her personal life.)

Coel’s idea of a “misfit” is “cross-generational and crosses concepts of gender or culture,” and it’s characterized “by a desire for transparency, a desire to see another’s point of view.” It’s Harriet all over, as she peers from a place of safety to observe people’s lives unfolding around her, scribbling her observations in her notebook.

Throughout Fitzhugh’s books, she makes the case for “children’s liberation” most obviously in Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change. Along the way, as Brody observes, she provides “life-preserving strategies that children may employ in their power struggle with adults.”

It’s not just truth-telling, it’s truth-building: “Lying is one time-honored tactic; self-reliance is another.” Brody provides both insight and understanding, in focusing on the struggles and triumphs that fuelled Fitzhugh’s artistic career and infused her art and literature. While Harriet is recording the truths she observes around her, learning when and how to articulate them, she is shaping her unique understanding of the world and making a space for misfits, like her, in it.

Joan Williams said Louise believed “writing for children gave her a wonderful sense of doing good.” This sense is as evident in Leslie Brody’s biography as it is in Fitzhugh’s writing. I’m as much of a Harriet fan as I ever was.

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Sometimes You Have to Lie: The Life and Times of Louise Fitzhugh, Renegade Author of Harriet the Spy by Leslie Brody appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 2, 2021

The Ultimate Caspary Woman: Laura by Vera Caspary

Laura, a detective novel/murder mystery published in 1943, has remained Vera Caspary’s best-known work, partially thanks to the well-regarded film adaptation that followed. The slim yet action-packed story was first serialized in Collier’s magazine in 1942 as Ring Twice for Laura.

In the excellent afterword for the 2005 Feminist Press edition of this book, A.B Emrys writes:

“Caspary’s fairy tale for working women takes place in a world of men who use women for advancement and self-reflection. The potential darkness of this world places Laura into the noir category and shadows even Caspary’s non-crime fiction … ‘Who can you trust’ was a game working women had to play frequently, and Laura makes evident that women might be labeled femmes fatales because they worked in the male-dominated business world.”

Though Laura is sometimes classified in the femme fatale genre, this isn’t accurate. The eponymous heroine is a smart, hardworking, independent woman (her dicey taste in men aside), and the prototype for the ultimate Caspary woman. The following discussion of Laura is excerpted from the forthcoming No One Named Vera Can Ever Tell a Lie: The Novels of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth:

Laura turned detective fiction on its head. In most mid-twentieth century women’s crime novels, the central character is a male detective: Marjorie Allingham’s Albert Campion; Margaret Millar’s Paul Prye, Inspector Sands and Tom Aragon; Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey; Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot (Miss Marple is an exception); Ngaio Marsh’s Inspector Alleyn.

They were all working in a tradition started in 1878, ten years before Sherlock Holmes first appeared, by Anna Katharine Green, the “mother of detective fiction” with her series of detective Ebenezer Bryce novels. If Philip Marlowe is the Chandler man, Laura introduces the Caspary woman.

“She is carved from Adam’s rib, indestructible as legend, and no man will ever aim his malice with sufficient accuracy to destroy her.”

This is from the final sentence of Laura, Vera Caspary’s fifth novel, her first major commercial success. It has remained her most famous and popular work, as a novel and as well as the 1944 film adaptation.

Enter the Caspary Woman

Laura is the first of a series of thrillers in which the Caspary woman appears, bursting onto the page here as a fully formed heroine for her time. Caspary much later described this woman in her autobiography:

“I’d given Laura a heroine’s youth and beauty but had added the strength of a woman who had, in spite of the struggle and competition of success in business, retained the feminine delicacy that allowed men to exercise the power of masculinity.”

Laura Hunt, as the first Caspary woman, would have several successors in Caspary’s works but very few in the works of other writers, even female ones; Laurel Grey in Dorothy B. Hughes’ 1947 In a Lonely Place is an exception. Laurel (as filtered through the viewpoint of the male anti-hero) was “a dream he had not dared dream, a woman like this. A tawny-haired woman; a high-breasted, smooth-hipped, scented woman; a wise woman.”

Laura is groundbreaking for its title, which unambiguously points to a woman as being the focus of the novel rather than the solving of a crime. Very few mid-twentieth century novels of any genre had just a woman’s name as the title – Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938), though the title character is dead and doesn’t appear in the novel in person.

The genesis of Laura

Caspary had never written a murder mystery in the form of a novel before Laura and had not been particularly inclined to do so because character has to give way to plot in a crime novel.

“Mysteries had never been my favorite reading. The murderer, the most interesting character, has always to be on the periphery of action lest he give away the secret that can be revealed only in the final pages.”

A murder mystery as a screenplay was an easy thing for her but a novel was something completely different. In her 1979 autobiography, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, Caspary talks about the genesis of Laura:

“Most of my originals had been murder stories, but I never thought of them in the same class as a novel. The novel demands a full development of each character. This was my problem. Every character in the story, except the detective, was to be a suspect—particularly the heroine, with whom the detective was to fall in love.

If her innocence was in doubt, how could her thoughts be made clear to the reader? I did not want to cheat. If she and the other characters were to be made more than detective-story stereotypes, I had to find a way to show them alive and contradictory while keeping secret the murderer’s identity.

The story fascinated my friend Ellis St. Joseph, who suggested that I try the Wilkie Collins method of having each character tell his or her own version, revealing or concealing information according to his or her own interests. Night after night Ellis and I sat up talking about Waldo Lydecker, the impotent man who tries to destroy the woman he can never possess.

We developed his background, imagined his youth, analyzed the causes of his frustrate masculinity, considered his taste, his talent, his idiosyncrasies. I enjoyed the trick of writing in his style, contrasting his florid mannerisms with the direct prose of the detective and, through the girl’s version, showing the vagaries of the female mind. After all those barren mechanical years, I worked with the zest of a young writer with a first novel.

Sometime in October it was finished. In order to see the story objectively I needed time away from obsession. Paramount offered a job and I went to work on a story about a night plane to Chungking. War interrupted. . .

I returned happily to reworking my mystery. On Christmas morning I wrote ‘The End’ and, on the title page, Laura. At dinner my friends toasted the book. Indeed it was a splendid holiday, the start of a new career and a year that was to change my life. I had come to California for three months; I stayed twenty-four years.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Laura by Vera Caspary on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Laura does indeed employ multiple points of view, being narrated at first by the effete aesthete Waldo, who we initially assume is going to be the central character.

Waldo’s first-person narration is followed by a section of narration in the third person with Waldo as the informing intelligence, and then by sections narrated by the detective Mark McPherson, an interlude of stenographic reports of interviews at the police station and narrations by Laura herself.

But, hang on, how can Laura speak? She’s dead? Isn’t she?

No, she isn’t, as it turns out. At first, we are meant to think that Laura Hunt is like Rebecca, the absent titular heroine who overshadows everything and everyone from beyond the grave.

But, after “her” funeral, Laura returns and we find out that the dead body lying in the doorway of Laura’s apartment with her face blown away by the shotgun was not Laura at all but Laura’s friend Diane, wearing her robe; she had been staying in Laura’s apartment while Laura was away.

Not that Diane was much of a friend anymore: she had stolen Laura’s boyfriend Shelby, making Laura the prime suspect in her murder. This is quite a twist: the murdered woman is not the murdered woman but the putative murderer of another woman.

From echoing Rebecca, Laura suddenly turns into Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White, 1859, with which it has many deliberate parallels, including the name of its title character. In Collins’ novel, the two young women Anne and Laura’s identities are switched after Laura refuses to give up her marriage settlement of twenty thousand pounds. Anne then dies of her long-term illness and is buried as Laura; Laura is considered mad for claiming to be Laura and is locked up.

Waldo Lydecker

Caspary’s physical description of Waldo Lydecker came straight from Count Fosco in The Woman in White; this sentence describing Fosco could just as well be in Laura.

“Fat as he is and old as he is, his movements are astonishingly light and easy. He is as noiseless in a room as any of us women, and more than that, with all his look of unmistakable mental firmness and power, he is as nervously sensitive as the weakest of us. He starts at chance noises as inveterately as Laura herself.”

Everything in the description of Waldo that Caspary worked so hard on with Ellis St. Joseph – his exquisite taste, his apartment, his cane, his Filipino houseboy, his erudite, witty, and rather camp writing style – scream to the contemporary reader, and perhaps to the sophisticated reader in 1945, that Waldo is gay.

But, as we saw, according to Caspary’s much later description in her autobiography, Waldo is intended as an “impotent man who tries to destroy the woman he can never possess,” namely, Laura. Waldo is a beautifully drawn character: a famous reviewer, columnist and essayist, waspish and withering, a society butterfly.

If we have not read Caspary’s autobiography, we will assume that Waldo loves Laura, with whom he has had a close relationship for several years, in a nonsexual way, that it is good for him as a gay man to be seen about town with a beautiful young woman – lavender marriages were very common at the time in high society, especially in Hollywood

For her part, Laura is happy to be in the company of somebody much older, a wealthy, cultured man who is no threat, intended to keep away the attention of younger, eligible men. It does strike rather a sour note when, towards the end, we find out that Waldo’s love for Laura was nowhere near platonic, though we may remember that at the beginning of the book Waldo has said, “I offer the narrative, not so much as a detective yarn as a love story.”

. . . . . . . . . .

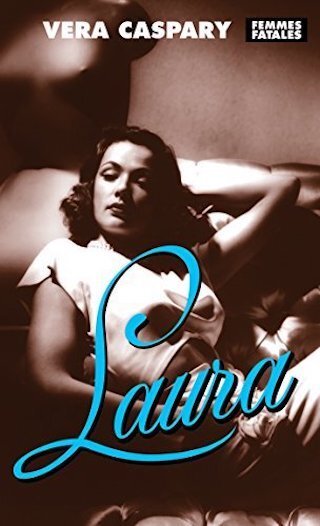

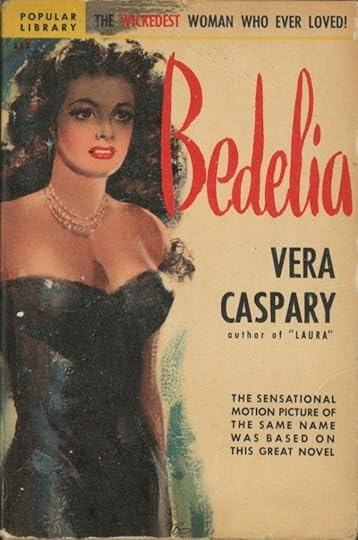

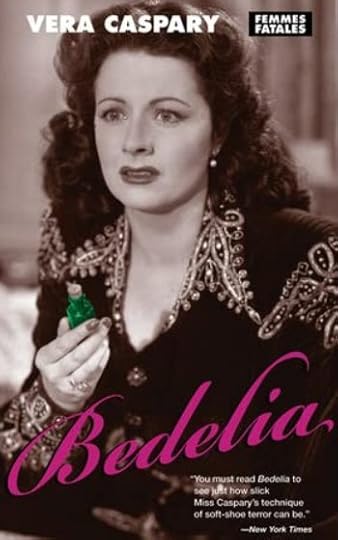

The sensationalized pulp cover

. . . . . . . . . .

But, despite her affection for Waldo and the amount of time she spends with him, Laura does have a boyfriend, the rogue Shelby Carpenter, a louche lounge lizard and something of a playboy.

We are not too surprised to find out later that Shelby has been having an affair with the late Diane and possibly even with Laura’s wealthy aunt Susan – a Caspary woman herself, with no man in sight, a summer place on Long Island and a big house on Fifth Avenue – despite Susan’s northerner’s snobbery about southern men.

Laura works in advertising, in a role not entirely unlike Caspary’s own jobs in copywriting. She is very successful at it – the Caspary woman is always a success in business and Laura does very well financially, much better than Shelby, who has a very loose work ethic. Caspary women tend to be more ambitious and earn more than the men they associate with; the men tend to have something of a problem with this.

Laura’s career and earning potential are also contrasted to those of the detective Mark, who says to Waldo, “I’m a workingman, I’ve got hours like everyone else. And if you expect me to work overtime on this third-class mystery, you’re thinking of a couple of other fellows.”

Also contrasting with Laura is the now-deceased Diane, who is not at all the typical Caspary woman. Her shabby downtown apartment is starkly contrasted with Laura’s swanky but discreet place up on East 66th Street in Manhattan.

Despite the exorbitant rent on her remodeled third-floor apartment with a garden, unheard of in Manhattan (though Caspary woman Sara in Murder at the Stork Club has one; she also has a PI husband who earns a lot less than she does), Laura “had lived here, she told me, because she enjoyed snubbing Park Avenue’s pretentious foyers.”

She has her own key to the door at street level, which is essential to the plot: if she had lived in a doorman apartment, the killer would have been seen. In Diane’s very different fourth floor apartment in the West Village there is the added subtle class distinction that Diane paid cash in stores rather than having an account, as any true Caspary woman would.

Detective Mark’s turn

Mark inspects her apartment, trying to pin down her character. He does, as superbly and succinctly encapsulated in Caspary’s writing:

“There were no bills as there had been in Laura’s desk, for Diane came from the lower classes, she paid cash. The sum of it all was a shabby and shiftless life. Fancy perfume bottles, Kewpie dolls, and toy animals were all she brought home from expensive dinners and suppers in night spots. The letters from her family, plain working people who lived in Paterson, New Jersey, were written in night-school English and told about layoffs and money troubles. Her name had been Jennie Swobodo.”

As Laura is one of Caspary’s alter egos, so Diane is the other. Caspary talked in her autobiography of the “skinny girl” of her imagination, the girl who represents the other side to her public persona.

Detective Mark, speaking in his hard-boiled, noir mode says of the deceased, purely based on seeing her apartment, “I had known girls like that around New York. No home, no friends, not much money. Diane had been a beauty, but beauties are a dime a dozen on both sides of Fifth Avenue between Eighth Street and Ninety-Sixth.”

Both apartments are contrasted with the elegance and refinement of Waldo’s, filled as it is with the most refined and exquisite antiques.

“Everything he owned was special and rare. His favorite books had been bound in selected leathers, he kept his monogrammed handkerchiefs and shorts and pajamas in silk cases embroidered with his initials. Even his mouthwash and toothpaste had been made up from special prescriptions.”

Laura claims, when suspected of murdering Diane out of jealousy, not to have been upset by Diane’s relationship with ostensibly perfect Kentuckian gentlemen Shelby, even though Laura and Shelby were to have been married just a few days after the murder. Laura herself claims to have come from a poor background, though this seems unlikely in light of her aunt’s Fifth Avenue brownstone.

“I’m not so different. I came to New York, too, a poor kid without friends or money. People were kind to me . . . and I felt almost an obligation toward kids like Diane. I was the only friend she had. And Shelby.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The 1944 film poster

. . . . . . . . . .

In a Caspary woman gender reversal, Laura has given Shelby an extravagant cigarette case, “fourteen-karat gold, as a man might buy his wife an orchid or a diamond to expiate infidelity.” Normally the giver is the unfaithful one, but not Laura. Shelby has given the precious object to Diane – surely not something a true southern gentleman would do.

Diane has pawned it and Laura has found out, giving her ample motive for the murder of Diane. Meanwhile, Mark the detective has developed more than a professional interest in Laura – and vice versa. Waldo is outraged, he tries to make Laura understand how a man like Mark sees women: he cannot truly appreciate them.

“Do you know Mark’s words for women? Dolls. Dames.” Waldo, connoisseur of women as of all things aesthetic, sneers to her, “What further evidence do you need of a man’s vulgarity and insolence? There’s a doll in Washington Heights who got a fox fur out of him—got it out, my dear, his very words. And a dame in Long Island whom he boasted of deserting after she’d waited faithfully for years.”

Waldo also tries to persuade Mark that he is mad to pursue Laura, who is completely out of his league. But Mark’s obsession makes him blind to the fact that any true Caspary woman will always be beyond his reach.

Laura is indeed no dope and is not at all bound by the shackles of romance, but, “going on thirty and unmarried, I had become alarmed,” and bought Shelby the cigarette case, “pretending to love him and playing the mother game.”

For Laura, as a true Caspary woman, gender roles are inverted: the handsome, debonair Shelby was to be a trophy husband; the fact that her friend pursued her fiancé simply reinforced the triumph of the trophy.

Laura thinks of Shelby as a child, exactly in the way a stereotypical male character in a novel by a male writer might think of his stereotypical trophy wife. “I was afraid because I had always been weak with a thirty-two-year-old baby.”

Interestingly, since Caspary says in her autobiography that she enjoyed playing with the different styles of narration it is surely not a coincidence that the sections narrated by Laura are better written, with finer, more “novelistic” writing than the others.

But, though only Laura and no one else appears to have a motive for murdering Diane, Shelby also has a motive for murdering Laura. Mark and everyone else assume that Diane was shot by mistake when she answered the door in Laura’s robe while staying at Laura’s apartment, but what if she wasn’t? What if Laura was the target?

In a gender-reversed pre-echo of the plot driver in Bedelia there is a twenty-five thousand dollar insurance policy that Laura has made over to him. Shelby has a shotgun, as any southern gentleman would, so he has means as well as motive and opportunity.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also:

Is Vera Caspary’s Bedelia the Wickedest Fictional Anti-Heroine?

. . . . . . . . . .

Was it then Laura, the Caspary woman who expects the same rights as men, who wanted sex from a relationship, and Waldo who was unable to give it? Did she turn to Shelby to satisfy her physically?

And was Shelby driven to Diane because he was scared of Laura, unable to satisfy a woman who was smarter than him and earned five times as much as he did? None of these things could be said out loud in 1942.

And then, what happens after the ending of the novel? Does Laura go ahead and marry Shelby, or does Mark take his place? We have to hope not: Mark would never cope with her, she would destroy him. Mark, with his dolls and dames and police cronies, would never understand the Caspary woman.

More information

Hardboiled Feminism Wikipedia (1943 novel) Wikipedia (1944 film) Reader discussion on GoodreadsContributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Ultimate Caspary Woman: Laura by Vera Caspary appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 1, 2021

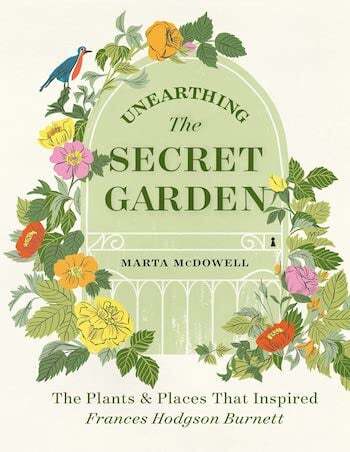

Unearthing the Secret Garden by Marta McDowell

In Unearthing the Secret Garden, Marta McDowell pays homage to the enduring classic by Frances Hodgson Burnett that has enthralled generations of readers. Through the universal metaphor of garden cultivation, The Secret Garden conveys a message of hope, and the renewal of the life as well as the self.

The Secret Garden introduced the reader to an unlikely heroine, Mary Lennox, a sickly and neglected 10-year-old born to wealthy British parents in colonial India. After a cholera epidemic kills her parents, Mary is sent to England to live with her uncle in a mysterious house.

The story follows the spoiled and sulky young girl as she slowly sheds her sour demeanor after discovering a secret locked garden on the grounds of her uncle’s manor. She befriends Dickon, a free spirit who can communicate with animals, and Colin, her uncle’s son, a neglected and lonely invalid.

Unearthing the Secret Garden is Marta McDowell’s gorgeous, deeply felt tribute to the timeless tale. Filled with photographs of the flowers, plants, and gardens that inspired Burnett, it also presents vintage illustrations from several editions of The Secret Garden, a book that has never gone out of print.

The following excerpt is from Unearthing the Secret Garden: The Plants & Places That Inspired Frances Hodgson Burnett. @2021 by Marta McDowell, Timber Press. Reprinted by permission; all rights reserved.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Unearthing the Secret Garden is available on Bookshop.org*, Amazon*,

and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . . . .

THE SECRET GARDEN is revealed scene by scene through Mary’s eyes. Only the robin, “who had flown to his treetop,” accompanies her. “It was the sweetest most mysterious-looking place any one could imagine,” the narrator tell us.

Mary sees stone seats in evergreen alcoves and tall moss-covered urns—formal elements softened by age. The remains of grassy paths meander here and there. The garden’s high walls are thick with leafless stems of climbing roses. Frances Hodgson Burnett infused her nostalgia for Maytham’s rose garden into the atmosphere of the abandoned garden:

… Their thin gray or brown branches and sprays looked like a sort of hazy mantle spreading over everything, walls, and trees, and even brown grass, where they had fallen from their fastenings and run along the ground. It was this hazy tangle from tree to tree which made it all look so mysterious. Mary had thought it must be different from other gardens which had not been left all by themselves so long; and indeed it was different from any other place she had ever seen in her life.

Now it was to be hers, her own.

If you have ever stepped into a garden and felt a shiver of something—recognition? awe?—you have had your own secret garden moment. Nature and a gardener have conspired to make a place that resonates at the same harmonic frequency as your spirit. A mystery. Some combination of light, color, plant, and place causes it, like the golden mean employed by ancient architects. It is an effect to which every gardener aspires.

. . . . . . . . .

Mary clears around the “sharp little green points;”

Illustration by Nora S. Unwin

. . . . . . . . .

Mary is uneasy. Is the secret garden dead? Ten years is a long time to be neglected. The grass is brown, the rose plants look gray and brittle—something that never happened in India. But then she notices “sharp little pale green points” sticking out of the earth.

“Yes, they are tiny growing things,” she whispers to herself, “and they might be crocuses or snowdrops or daffodils.” She starts to clear around them with a pointed piece of wood, by instinct wanting to give them more room to breathe.

Back in her room, she can’t stop thinking about the garden. She is struck with a desire to see all the things that will grow in England, plant lust being common to most gardeners, new or old. “I wish—I wish I had a little spade,” she tells Martha that afternoon. Worried that she will give away her secret, Mary quickly adds that she would like to make a little garden somewhere.

For the acquisition of the spade, Martha promises to employ her brother, Dickon. Mary sends along a written request with some money on Martha’s next day off so that he can buy it in the village.

“In the shop at Thwaite they sell packages o’ flower-seeds for a penny each, and our Dickon he knows which is th’ prettiest ones an’ how to make ’em grow,” Martha informs Mary in her broad Yorkshire. “Our Dickon can make a flower grow out of a brick walk. Mother says he just whispers things out o’ th’ ground.”

Like the Greek god Pan, Dickon is at home in nature. Frances once referred to him as a sort of faun, and in the book, he is described as “a sort of wood fairy,” red-cheeked and blue-eyed. He is slightly older than Mary—about twelve.

In Dickon, Burnett created a character to embody her own connection with the animal world. She was convinced that in past incarnations she had been animals, especially birds. “I am such friends with them and I understand them so and they are so sure of it and are such friends with me,” she had once said. And so it is with Dickon Sowerby.

Mary first comes upon Dickon in person sitting under a tree in the woods adjoining Misselthwaite’s gardens. He is playing his wooden pipe. Wild creatures are keeping him company. A crow named Soot. Captain the fox cub. Dickon unwraps a package for Mary. There is a miniature spade, plus a small rake, a garden fork, a hoe, a trowel, and some packets of flower seeds.

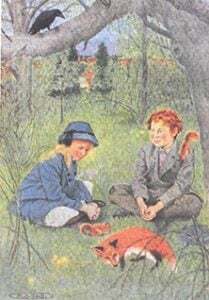

. . . . . . . . .

Mary and Dickon discuss their garden plans surrounded by

his rescued animals; illustration by M.L. Kirk

. . . . . . . . .

After a long conversation about flowers and growing things, Mary decides to share her secret with Dickon, sneaking him through the ivy-hidden door. His reaction doesn’t disappoint. “Eh!” he gasps in an almost whisper. “It is a queer, pretty place! It’s like as if a body was in a dream.” Frances had gauged her friends’ reactions to Maytham’s rose garden in much the same way.

Over the weeks that follow, Mary and Dickon work in the garden—pruning, weeding, and avoiding detection. He teaches her about gardening. Perennials like lily-of-the-valley need to be divided. Biennials require patience, growing green one year in order to bloom the next.

Dickon reassures Mary that most of the roses are “wick,” that is, very much alive. They make an unusual pair: a poor but much-loved boy in tune with the natural world and a stunted rich girl who grew up without affection.

Dickon is Mary’s teacher at Misselthwaite in the same way that Frances’s friends—and vicars—at Maytham had been generous with gardening lessons and advice. To make plants thrive, Dickon knows that one must “be friends with ’em for sure.”

Like his tame animal friends, garden plants need attention. “If they’re thirsty give ’em a drink and if they’re hungry give ’em a bit o’ food.” It’s good advice for any gardener. Mary absorbs his lessons like a thirsty plant.

The two children decide to cultivate a different sort of garden. Unlike Misselthwaite’s formal borders—tended by head gardener Mr. Roach and his staff—theirs will be a tad untamed. “I wouldn’t want to make it look like a gardener’s garden, all clipped an’ spick an’ span, would you?” Dickon asks.

“It’s nicer like this with things runnin’ wild, an’ swingin’ an’ catchin’ hold of each other.” Mary agrees. “It wouldn’t seem like a secret garden if it was tidy.” Like the rose garden at Maytham Hall, the secret garden is to be in the spirit of the Arts and Crafts movement.

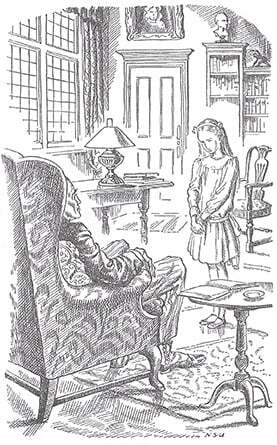

With her new interest and activities, Mary’s disposition improves as does her appetite. Then reality intervenes. Archibald Craven comes home to roost, and so does Mary’s guilty conscience.

In a tense interview with her uncle, she reverts into a plain fretful child, worried that he will ban her from the outdoors in general or the secret garden in particular. But he provides a chance opening when he asks if there is anything she wants. He meant a toy or a book.

. . . . . . . . . .

Mary approaches her uncle to ask for her “bit of earth,”

illustration by Nora S. Unwin

. . . . . . . . . .

Omitting the particular space she has in mind, Mary asks her uncle if she might have “a bit of earth [t]o plant seeds in—to make things grow—to make them come alive.”

Archibald Craven is stunned, reminded of Lilias, his dear wife, who had also loved to garden. “When you see a bit of earth you want[,] take it, child, and make it come alive,” he responds, full of emotion. That was all Mary needed to hear. Craven leaves the next day for yet another tour of the Continent, and the secret garden is hers.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Marta McDowell: Marta McDowell lives, gardens, and writes in Chatham, New Jersey. She consults for public gardens and private clients, writes and lectures on gardening topics, and teaches landscape history and horticulture at the New York Botanical Garden, where she studied landscape design.

Marta’s particular interest is in authors and their gardens, the connection between the pen and the trowel. In 2018, she was the Emily Dickinson Museum’s Gardener-in-Residence, and she was the 2019 winner of the Garden Club of American’s award for outstanding literary achievement. Her books include Unearthing the Secret Garden, Beatrix Potter’s Gardening Life, The World of Laura Ingalls Wilder, Emily Dickinson’s Gardening Life, and All the President’s Gardens. Visit her at Marta McDowell.

MORE BY MARTA MCDOWELL ON THIS SITE

Emily Dickinson’s Gardening Life

Beatrix Potter’s Gardening Life

Beatrix Potter’s Letters to Children: The Path to Her Books

Laura Ingalls Wilder: Late-Blooming Author with a Passion for Nature

. . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy: Quotes from The Secret Garden

. . . . . . . . . .

The Secret Garden is indisputably one of the most beloved children’s classics. Published in 1911, it has never been out of print, selling millions of copies worldwide.

What many readers don’t know, however, is that its author, Frances Hodgson Burnett was one of the most popular and prolific writers of her time. Unsurprisingly, she was also a lover of flowers and gardens—but the path to her literary triumph was a long one, beset with personal tragedy and illness.

In Unearthing The Secret Garden, Marta McDowell starts by chronicling Burnett’s childhood and early life, with a focus on her growing interest in gardens and her development as a writer. McDowell also shares details of the three gardens Burnett created in England, Long Island, and Bermuda. A guide to the plants featured in The Secret Garden will delight gardeners.

In addition, McDowell transcribes the complete text of three of Burnett’s garden-themed stories, which help to deepen our appreciation of Burnett’s love and knowledge of gardening. McDowell complements her delightful text with period illustrations and contemporary photographs that bring Burnett’s world vividly to life for the reader.

Just as The Secret Garden continues to enchant readers of all ages, so Unearthing The Secret Garden draws us into a richly textured account of the fascinating professional and gardening life that gave us one of literature’s greatest treasures.

. . . . . . . . .

See also: 4 Classic Books by Frances Hodgson Burnett

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Unearthing the Secret Garden by Marta McDowell appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 30, 2021

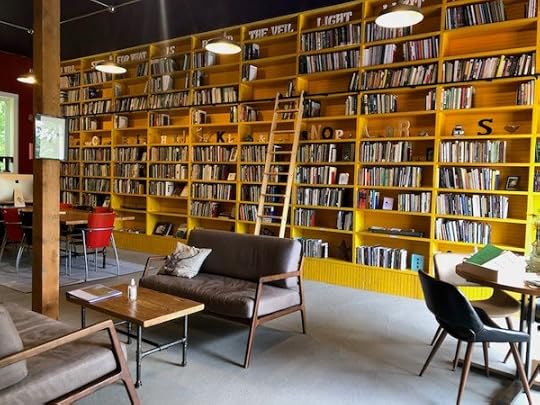

The Poetry Barn in West Hurley, NY

If you do a search on “Poetry Barn,” Google will first serve you an ad for Pottery Barn. Scroll right past that and you’ll arrive at the right destination — The Poetry Barn in West Hurley, New York, a private library and workshop/event space dedicated to all things poetic.

The Poetry Barn is the creation of founding director Lissa Kiernan, who converted a small barn into housing for an inviting 3,000+ volume lending library. In the surroundings of contemporary and classic poetry books, the space is a haven for a myriad of ongoing virtual and in-person workshops and occasional events.

The venue is located on a quiet residential road near the beautiful Ashokan Reservoir in Ulster County, in the Catskill foothills region of New York State. If the weather cooperates, try to schedule some time to walk around the reservoir if you’re making a special trip.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

How to visitMake an appointment for a visit: Make sure not to just show up, whether you’ve traveled from near or afar — you’ll need to make a reservation, especially important at this time, for a visit. Here is The Poetry Barn’s visit scheduler.

Tuesday-Friday, 12-6 PM (by appointment)

Saturdays 12-4 PM (by appointment)

Web: The Poetry Barn

Contact: Email: hello@poetrybarn.org | Phone: (845) 280-0430

. . . . . . . . .

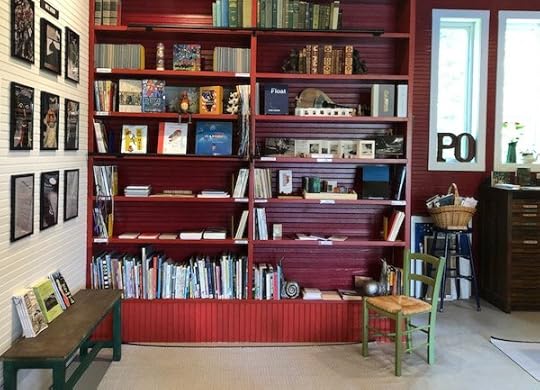

The children’s corner

. . . . . . . . .

From The Poetry Barn’s website, here is their mission:

“The Poetry Barn nurtures poetry education, inspiration, and appreciation through workshops, retreats, readings, and a comprehensive poetry lending library made freely accessible to the public. Nestled in the foothills of Catskill Park in Hudson Valley, surrounded by the protected lands of the Ashokan Reservoir, we take nature as inspiration, and act as a pollinator habitat for poetry and its sister arts.”

. . . . . . . . .

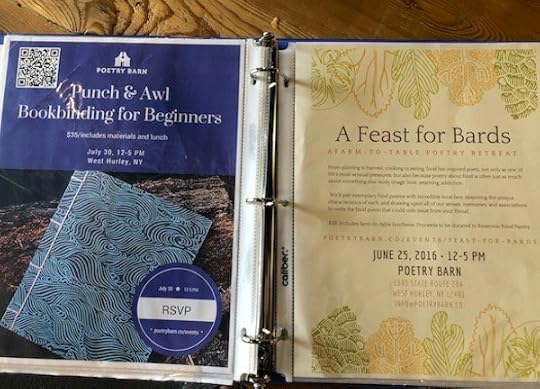

This image displays just a small sampling of the workshops offered.

Explore the entire range of workshops here.

. . . . . . . . .

The Poetry Barn offers an amazing array of workshops year -ound. Some are asynchronous (meaning you sign up for it and do the workshop on your own time, not in real time), while others are real-time Zoom events. One-on-one mentoring with noted posts is also available.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

EventsThe Poetry Barn hosts, onsite and off, wonderfully rich poetic events — readings, book launches, intimate concerts, and special workshops and classes. Check the calendar for upcoming events.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

At the heart of The Poetry Barn is, as mentioned earlier, a 3,000+ volume lending library. It’s open year-round by appointment. Books may be borrowed by members — see below.

. . . . . . . . .

Membership

MembershipMembership begins at $25 per year and includes these benefits: Borrowing books from the library, 10% discounts on workshops, and invitations to exclusive events. Here’s how to become a member.

Enjoy a little poetic retail therapy with books, journals, unusual paper, and other objects for the poet in your life (or for yourself!). Grab a cup of coffee and find a cozy chair to read for an hour or so, and view the rotating display of local art.

See more of this site’s Literary Travels features.

The post The Poetry Barn in West Hurley, NY appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 28, 2021

Is Vera Caspary’s Bedelia the Wickedest Fictional Anti-Heroine?

“As in Laura and now again in Bedelia, Vera Caspary avoids the conventional groove. No mysterious opening doors for her. No velvet-gloved hands or hidden rubies. No eerie cries in the night. Murder, yes, suspense, yes – plenty of it – but at the core of her stories is a comprehension that illuminates and gives credibility to the incredible actions of men and women.” (— from the back cover blurb of the 1945 first US edition).

The following analysis of Bedelia (1945) by Vera Caspary is excerpted from the forthcoming A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Novels of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth. Reprinted with permission.

Literary parallels“She seduces men … but does she kill them? A mystery about the wickedest woman who ever loved.” (— Front cover blurb from the 2012 paperback edition published in the Femmes Fatales series by the Feminist Press at the City University of New York)

Is Bedelia the wickedest literary woman who ever loved? There are certainly some earlier candidates. Young and innocent-looking murderesses in Victorian British fiction include Lydia Gwilt in Armadale by Wilkie Collins: “I shall be your widow,” says the poisonous Lydia, “in half an hour!” and Lucy Audley, from Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret, who “bore the red brand of murder on her soul.”

At least one academic has seen multiple parallels between Bedelia and Lady Audley; it is entirely possible that Caspary read Braddon though there is no direct evidence that she did.

We do know however that she admired and deliberately emulated Wilkie Collins — as we have just seen she imitated him in the literary form of Laura and as we will soon see, even more closely in Stranger than Truth.

In Daphne du Maurier’s novel My Cousin Rachel, Philip’s eponymous cousin may or may not have tried to poison him; he was to marry her after giving her all the family treasure, but we never find out.

Close to Caspary’s time and style are husband murderer Cora from James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934) and Phyllis Nirdlinger from Double Indemnity (1943), who seduces an insurance agent into helping her kill her husband for the money; the same twin themes of insurance agent and husband murder as we find in Bedelia, but with the role of the insurance man reversed.

Carmen Sternwood in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep (1939) and its 1946 movie murders her brother-in-law and tries to kill Philip Marlowe. There is also Miss Wonderley from Dashiell Hammett’s novel and 1941 film The Maltese Falcon (1929), a murderess who tries to use her charms to manipulate Sam Spade and does seduce him.

A brief introduction

If you had been reading the original hardback American or British versions of Bedelia before the film appeared, you would have been a hundred pages in before suspecting the charming heroine of being a murderess. And if you had bought any of the paperback editions with their unsubtle front cover blurbs giving the game away, by page one hundred you might be starting to feel disappointed — no one has yet died.

Earlier on though, Caspary would have teased you with the doctor’s suspicion that Charlie Horst’s recent illness may have been caused by poison – a poison that was perhaps given to him by his new wife Bedelia. But Charlie doesn’t believe it and we’re not sure either. Bedelia does seem like the perfect wife for Charlie, and they do seem to be in love.

As the novel opens on Christmas Eve 1913, the couple has invited in many friends. Bedelia has done them proud with her lavish preparations, literally without breaking a sweat, while Charlie is sweating from all the exertion.

“Bedelia’s ivory-tinted skin continued to look as fresh and cool as the white rose she had pinned in her sash.” The rose is from a bouquet brought by neighbor Ben, an artist newly moved into the area, with whom gossip has it that Bedelia might be enamored, and perhaps vice versa; he wants to paint a portrait of her.

Bedelia has bought rather expensive presents for their friends. “She had packages for the men as well as for their wives. And such luxurious trifles!” Charlie’s old money New England friends see this as rather crass, the Austen-named guest Mrs. Bennett “computed the cost of Bedelia’s generosity. ‘We’ve none of us measured up to your wife’s extravagance, Charlie. It’s not our habit to be so ostentatious as Westerners.’”

Bedelia is no New Englander, not at all like her husband’s snooty neighbors.

“She was different from the other women in the room, like an actress or a foreigner. Not that she was common. For all of her vivacity, she was more gentle and refined than any of her guests. She talked less, smiled more, sought friendliness, but fled intimacy … Her mouth, when it was not smiling, was small and perfect, a doll’s mouth.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A heroine and a villainCharlie had not known his new wife very long before they married and still knows very little of her background.

“There were times when Charlie felt that he knew nothing about her. All that she had told him of her girlhood and first marriage seemed as unreal as a story in a book. When she related conversations she had with people she used to know, Charlie could see printed lines, correctly paragraphed and punctuated with quotation marks. At such times he would feel that she was remote, like the heroine of the story, a woman he might dream about but never touch.”

Bedelia is indeed the heroine of her own story, as she is the villain of Caspary’s. She has told Charlie that she was born in California and that her previous husband was an artist named Raoul Cochran, with whom she lived in New Orleans. She says that Raoul is now dead and that she lost the baby she was to have with him, though she is now pregnant – or is she? – with Charlie’s baby, even though they only met in August.

When she met Charlie, in Colorado Springs, Bedelia says, she was desperately poor; Charlie may have taken advantage of her: his love for her is by no means chaste and pure and he may have exploited her poverty in pursuit of his lust, which is undiminished since the marriage.

“He was glad he had married a widow,” according to a passage in the book. He soon won’t be, hints Caspary with a wink.

Fatal attraction

Later, when Charlie sees her wearing her black silk corset, he thinks it is “the most seductive garment he had ever seen and, whenever Bedelia wore it, he wanted to make love to her.”

This is quite strong stuff for the mid-1940s, implying a laxity of morals on the part of Bedelia, a laxity that is intended to attract men. Nevertheless, Bedelia also has “a natural talent for housekeeping. With less fuss than his mother had made with her two servants, Bedelia and the young girl, Mary, kept the house like a pin.”

The ideal wife – apparently – Bedelia is the perfect male-fantasy combination of naughty and nice, slutty and house-proud, at home in both the bedroom and the kitchen. She wears a black crêpe de chine dress which exemplifies this ambivalence. “The bodice was cut low but filled with ruffles of white lace. The dress was both decorous and daring. No woman could criticize, no man fail to notice.”

Later, while she is in bed and Charlie is ministering to her during the snowstorm when the house is cut off by blizzards with no phone or power and the maid and the doctor cannot get to the house, Bedelia explains to Charlie his attraction for her.

. . . . . . . . . .

Vera Caspary signed bookplate. Photo: AbeBooks.com

. . . . . . . . . .

Sneaky, sinister deceitCharlie has already felt that something is not entirely right about his perfect new wife. For one thing, she is afraid of the dark, though he tries to wean her off having the light on all night. It makes him see her, literally, in a different light.

“By day his wife was earthy, a woman who loved her home and had a genuine talent for housekeeping. In the dark, she seemed entirely another sort of creature, female but sinister, a woman whose face Charlie had never seen.”

Knowing what we know from the book’s blurb about Bedelia’s wickedness, the first hint Caspary dangles in front of us is when Charlie, with “sunken eyes, colorless lips, and a pistachio-green complexion” is ill. Bedelia makes him a sedative, pouring powder from a blue packet into a glass of water. “Drink it fast, you won’t notice the taste,” she says, as presumably do all female poisoners administering the coup de grâce.