Nava Atlas's Blog, page 30

February 9, 2022

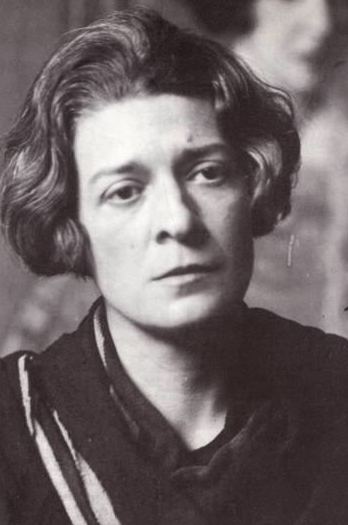

On Being Young—a Woman—and Colored by Marita O. Bonner (1925)

Marita Odette Bonner (1899 – 1971) was a short story writer, playwright, and essayist. Between 1925 and 1927 she produced a great number of short stories featuring characters from varied cultures navigating urban life. She became noted for two prize-winning essays — “On Being Young—A Woman—and Colored” (1925), presented here, and “Drab Rambles” (1927).

One of the earliest Black students at Radcliffe College, she was academically talented as well as a gifted pianist and composer. Upon her 1922, graduation, when she was named “Radcliffe’s Beethoven,” Bonner continued to blossom, becoming a noted figure in the Harlem Renaissance movement.

In the late 1920s, Bonner wrote three plays, the best known of which was The Purple Flower (1928). Her writings often dealt with the challenges of being Black in a racist society, a theme exemplified in the essay that follows.

“On Being Young—a Woman—and Colored” was a first prize winner in an annual contest sponsored by The Crisis (the journal of the NAACP, which had a decided literary bent). Originally published in their December 1925 issue, it is now in the public domain.

At the time of this essay’s publication, the prolific Marita Bonner was working as an English teacher at the Armstrong High School in Washington, D. C. She continued to write short fiction until 1941, after which she focused on raising her three children as well as teaching high school in Chicago.

On Being Young — a Woman — and Colored by Marita O. Bonner

You start out after you have gone from kindergarten to sheepskin covered with sundry Latin phrases.

At least you know what you want life to give you. A career as fixed and as calmly brilliant as the North Star. The one real thing that money buys. Time. Time to do things. A house that can be as delectably out of order and as easily put in order as the doll-house of “playing-house” days. And of course, a husband you can look up to without looking down on yourself.

Somehow you feel like a kitten in a sunny catnip field that sees sleek, plump brown field mice and yellow baby chicks sitting coyly, side by side, under each leaf. A desire to dash three or four ways seizes you.

That’s Youth. But you know that things learned need testing—acid testing—to see if they are really after all, an interwoven part of you. All your life you have heard of the debt you owe “Your People” because you have managed to have the things they have not largely had.

So you find a spot where there are hordes of them—of course below the Line—to be your catnip field while you close your eyes to mice and chickens alike.

If you have never lived among your own, you feel prodigal. Some warm untouched current flows through them—through you— and drags you out into the deep waters of a new sea of human foibles and mannerisms; of a peculiar psychology and prejudices. And one day you find yourself entangled—enmeshed—pinioned in the sea- weed of a Black Ghetto.

Not a Ghetto, placid like the Strasse that flows, outwardly unperturbed and calm in a stream of religious belief, but a peculiar group. Cut off, flung together, shoved aside in a bundle because of color and with no more in common.

Unless color is, after all, the real bond. Milling around like live fish in a basket. Those at the bottom crushed into a sort of stupid apathy by the weight of those on top. Those on top leaping, leaping; leaping to scale the sides; to get out. There are two “colored” movies, innumerable parties—and cards. Cards played so intensely that it fascinates and repulses at once.

Movies. Movies worthy and worthless—but not even a low-caste spoken stage. Parties, plentiful. Music and dancing and much that is wit and color and gaiety.

But they are like the richest chocolate; stuffed costly chocolates that make the taste go stale if you have too many of them. That make plain whole bread taste like ashes.

There are all the earmarks of a group within a group. Cut off all around from ingress from or egress to other groups. A sameness of type. The smug self-satisfaction of an inner measurement; a measurement by standards known within a limited group and not those of an unlimited, seeing, world … Like the blind, blind mice. Mice whose eyes have been blinded.

. . . . . . . . .

RELATED CONTENT

Renaissance Women: 13 Female Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

7 Black Women Playwrights of the Early 20th Century

. . . . . . . . .

Strange longing seizes hold of you. You wish yourself back where you can lay your dollar down and sit in a dollar seat to hear voices, strings, reeds that have lifted the World out, up, beyond things that have bodies and walls. Where you can marvel at new. marbles and bronzes and flat colors that will make men forget that things exist in a flesh more often than in spirit. Where you can sink your body in a cushioned seat and sink your soul at the same time into a section of life set before you on the boards for a few hours.

You hear that up at New York this is to be seen; that, to be heard. You decide the next train will take you there. You decide the next second that that train will not take you, nor the next— nor the next for some time to come.

For you know that—being a woman— you cannot twice a month or twice a year, for that matter, break away to see or hear anything in a city that is supposed to see and hear too much.

That’s being a woman. A woman of any color. You decide that something is wrong with a world that stifles and chokes; that cuts off and stunts; hedging in, pressing down on eyes, ears and throat. Somehow all wrong.

You wonder how it happens there that — say five hundred miles from the Bay State — Anglo Saxon intelligence is so warped and stunted.

How judgment and discernment are bred out of the race. And what has become of discrimination? Discrimination of the right sort. Discrimination that the best minds have told you weighs shadows and nuances and spiritual differences before it catalogues. The kind they have taught you all of your life was best: that looks clearly past generalization and past appearance to dissect, to dig down to the real heart of matters. That casts aside rapid summary conclusions, drawn from primary inference, as Daniel did the spiced meats.

Why can’t they then perceive that there is a difference in the glance from a pair of eyes that look, mildly docile, at “white ladies” and those that, impersonally and perceptively — aware of distinctions — see only women who happen to be white?

Why do they see a colored woman only as a gross collection of desires, all uncontrolled, reaching out for their Apollos and the Quasimodos with avid indiscrimination? Why unless you talk in staccato squawks — brittle as sea-shells — unless you “champ” gum — unless you cover two yards square when you laugh —unless your taste runs to violent colors — impossible perfumes and more impossible clothes —are you a feminine Caliban craving to pass for Ariel?

An empty imitation of an empty invitation. A mime; a sham; a copy-cat. A hollow re-echo. A froth, a foam. A fleck of the ashes of superficiality?

Everything you touch or taste now is like the flesh of an unripe persimmon … Do you need to be told what that is being …? Old ideas, old fundamentals seem worm-eaten, out-grown, worthless, bitter; fit for the scrap-heap of Wisdom.

What you had thought tangible and practical has turned out to be a collection of “blue-flower” theories. If they have not discovered how to use their accumulation of facts, they are use- less to you in Their world. Every part of you becomes bitter.

But — “In Heaven’s name, do not grow bitter. Be bigger than they are” — exhort white friends who have never had to draw breath in a Jim-Crow train. Who have never had petty putrid insult dragged over them — drawing blood —l ike pebbled sand on your body where the skin is tenderest. On your body where the skin is thinnest and tenderest.

You long to explode and hurt everything white; friendly; unfriendly. But you know that you cannot live with a chip on your shoulder even if you can manage a smile around your eyes—without getting steely and brittle and losing the softness that makes you a woman.

For chips make you bend your body to balance them. And once you bend, you lose your poise, your balance, and the chip gets into you. The real you. You get hard … And many things in you can ossify … And you know, being a woman, you have to go about it gently and quietly, to find out and to discover just what is wrong. Just what can be done.

You see clearly that they have acquired things. Money; money. Money to build with, money to destroy. Money to swim in. Money to drown in. Money.

An ascendancy of wisdom. An incalculable hoard of wisdom in all fields, in all things collected from all quarters of humanity. A stupendous mass of things. Things.

So, too, the Greeks … Things. And the Romans … And you wonder and wonder why they have not discovered how to handle deftly and skillfully, Wisdom, stored up for them — like the honey for the Gods on Olympus — since time unknown.

You wonder and you wonder until you wander out into Infinity, where — if it is to be found anywhere —Truth really exists. The Greeks had possessions, culture. They were lost because they did not understand. The Romans owned more than anyone else.Trampled under the heel of Vandals and Civilization, because they would not understand. Greeks. Did not understand.

Romans. Would not understand. “They.” Will not understand.

So you find, they have shut Wisdom up and have forgotten to find the key that will let her out They have trapped, trammeled, lashed her to themselves with thews and thongs and theories. They have ran- sacked sea and earth and air to bring every treasure to her. But she sulks and will not work for a world with a whitish hue because it has snubbed her twin sister, Understanding.

You see clearly — off there is Infinity — Understanding. Standing alone, waiting for someone to really want her. But she is so far out there is no way to snatch at her and drag her in.

So — being a woman — you can wait. You must sit quietly without a chip. Not sodden — and weighted as if your feet were cast in the iron of your soul. Not wasting strength in enervating gestures as if two hundred years of bonds and whips had really tricked you into nervous uncertainty.

But quiet; quiet. Like Buddha — who brown like I am — sat entirely at ease, entirely sure of himself; motionless and knowing, a thousand years before the white man knew there was so very much difference between feet and hands.

Motionless on the outside. But inside? Silent. Still … “Perhaps Buddha is a woman.”

So you too. Still; quiet; with a smile, ever so slight, at the eyes so that Life will flow into and not by you. And you can gather, as it passes, the essences, the overtones, the tints, the shadows; draw understanding to your self. And then you can, when Time is ripe, swoop to your feet — at your full height — at a single gesture. Ready to go where? Why … Wherever God motions.

The post On Being Young—a Woman—and Colored by Marita O. Bonner (1925) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 8, 2022

7 Black Women Playwrights of the Early 20th Century

In the heyday of the Harlem Renaissance movement of the 1920s, and the years just before and after, a notable number of Black women made a name for themselves as writers, playwrights, poets, editors, and journalists.

Women writers associated with the Harlem Renaissance era were often multifaceted, working as educators, librarians, musicians, and more while at the same time developing their talents in the written and theatrical arts.

Here we’ll take a look at seven Black women playwrights of the early twentieth century whose works written for the stage are ripe for rediscovery. For further in-depth overviews of Black women playwrights of the early twentieth century, consult these sources:

Black Female Playwrights: An Anthology of Plays Before 1950 (Kathy A. Perkins, editor). Indiana University Press, 1990.“Angelina Weld Grimké, Mary T. Burrill, Georgia Douglas Johnson, and Marita O. Bonner: An Analysis of Their Plays” by Doris E. Abramson in Sage, 1985 (This article is excellent, though it requires access to academic libraries via ProQuest)A brief overview of women playwrights whose work rose to prominence during the Harlem Renaissance era can be found in chapter 1 of Their Place on the Stage: Black Women Playwrights in America by Elizabeth Brown-Guillory. Prager, 1988.. . . . . . . . . . .

Marita O. Bonner

Marita Odette Bonner (1899 – 1971) was a short story writer, playwright, and essayist. Between 1925 and 1927 she produced a great number of short stories featuring characters from varied cultures navigating urban life.

Bonner was academically talented as well as a gifted pianist and composer. She was one of the earliest Black students at Radcliffe College. Jim Crow wasn’t just limited to the South, Bonner was forced to commute for all of her college years, as Black students weren’t allowed to live on campus. Upon her 1922, graduation, when she was named “Radcliffe’s Beethoven,” Bonner continued to bloom.

She became known for two prize-winning essays — “On Being Young—A Woman— and Colored” (1925) and “Drab Rambles” (1927). In the late 1920s, Bonner wrote three plays, the best known of which was The Purple Flower (1928). Her writing often dealt with the challenges facing Black communities in a racist society.

Marita Bonner continued to write short fiction until 1941, after which she focused on raising her three children as well as teaching high school in Chicago. Find Bonner’s plays in printed form:

The Pot-Maker (A Play to be Read): (Opportunity 5, Feb. 1927: pp. 43-46)

The Purple Flower.(The Crisis 35, Jan. 1928: pp. 202-07)

Exit — An Illusion.(Crisis 36, Oct. 1929: pp. 335-336; 352)

. . . . . . . . . .

Mary P. Burrill

Mary P. Burrill (1881 – 1946) was a prominent figure in the Harlem Renaissance era; her two plays, considered of cultural significance, were published in 1919. They That Sit in Darkness was published in Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Review, and Aftermath, published in The Liberator, a socialist publication. Aftermath was staged in New York City in 1928 by the Krigwa Players.

Burrill’s theatrical writings were classified as protest plays, as they aimed to advance views on social issues, notably race and gender. Burrill remained a central figure in the Washington, D.C. wing of the Harlem Renaissance movement, where she hosted a literary salon to encourage writers and other creative artists of the movement. She also enjoyed a long career at Dunbar High School, where she taught English and drama and directed plays and musicals.

Burrill’s partner was Lucy Diggs Slowe, who was appointed Dean of Women at Howard University (one of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities) in 1922. They were ahead of their time, living as a couple for twenty-five years, and even bought a house together. Burrill was heartbroken when Slowe died in 1937.

It’s not easy to find the full text of They That Sit in Darkness; the full text of Aftermath can be read here.

. . . . . . . . . .

Angelina Weld Grimké

Angelina Weld Grimké (1880 – 1958) was an American essayist, playwright, and poet whose work was frequently featured in The Crisis, the influential journal of the NAACP, and anthologies of the Harlem Renaissance era. She’s best remembered for her poetry and short stories. Themes of race and bias played a prominent role in her poetry and plays.

Rachel (which you can read in full by linking through) was the only play she wrote that was staged, but it was of great historic significance as one of the first public productions of a work by a woman of color. It had its debut in Washington D.C. in 1916 and was formally published in 1920. The program read:

“This is the first attempt to use the stage for race propaganda in order to enlighten the American people relative to the lamentable condition of the millions of Colored citizens in this free republic.”

Grimké wrote just one other play, Mara, which, like Rachel, dealt with the theme of lynching. It remains unpublished. Rachel was staged in a virtual performance by the Roundabout Theatre Company in 2021.

. . . . . . . . .

Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston (1891 – 1960) had a dual career as a writer (producing novels, short stories, plays, and essays) and anthropologist.

Though Zora is better known today for her novels (particularly Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), short stories, and essays, she was a surprisingly prolific playwright. Zora’s plays are far less known than her fiction and nonfiction works, mainly because most remain unpublished and unproduced. Still, they reveal another aspect of her talent and ambition. Most of the following plays can be accessed at the Collection of Zora Neale Hurston Plays at the Library of Congress.

The first play, Meet the Mamma, is dated 1925; the last, Polk County, is from 1944. The rest are dated from 1930 to 1935:

Meet the Mamma: A Musical Play in Three Acts; Cold Keener, a Revue; De Turkey and de Law: A Comedy in Three Acts; Mule Bone: A Comedy of Negro Life in Three Acts (co-written with Langston Hughes); Forty Yards; Lawing and Jawing; Poker!; Woofing; Spunk; Color Struck; Polk County: A Comedy of Negro Life on a Sawmill Camp with Authentic Negro Music in Three Acts.

. . . . . . . . . .

Georgia Douglas Johnson

Georgia Douglas Johnson (1880 – 1966) was best known as a poet active during the Harlem Renaissance era, though she also was an avid musician, teacher, and anti-lynching activist. She was one of the first African-American female playwrights and produced four books of poetry.

It’s estimated that she wrote nearly thirty plays, some of which have been lost along with other portions of her work. Of those, there are some twelve surviving plays. Although none of Georgia’s plays were published in her lifetime, several were staged at community venues such as churches, schools, YMCAs, and such. By the time she delved into writing plays, she had already earned a solid reputation as a published poet with Heart of a Woman and Other Poems (1918) and Bronze (1922).

A comprehensive collection of her surviving plays was published in 2006 — The Plays of Georgia Douglas Johnson: From the New Negro Renaissance to the Civil Rights Movement. this is the best resource in which to read her plays in full. It contains: Blue Blood; Plumes; Frederick Douglass; Paupaulekejo; Starting Point; A Sunday Morning in the South (white church version); A Sunday Morning in the South (Black church version); Safe; Blue-Eyed Black Boy; And Yet They Paused.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

May Miller

May Miller (1899 – 1995) was one of the most widely published female playwrights and poets of the Harlem Renaissance era. Though poetry was her first love, her accomplishments branched out widely. She was the first African-American student to attend Johns Hopkins University and became one of the pioneers in the field of sociology.

Miller augmented her work as a writer with a distinguished career as a teacher and lecturer in several prestigious institutions. Her major plays addressed colorism within the Black community, Black servicemen, lynching, and other issues of race and class.

Her major works include: The Bog Guide (1925); Scratches (1929); Stragglers in the Dust (1930); Nails and Thorns (1933). These were all republished by Alexander Street Press from 2001 to 2003. In addition, Miller also wrote many historical plays, four of which (including Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth) were included in the anthology Negro History in Thirteen Plays (1935).

. . . . . . . . . . .

Eulalie Spence

Eulalie Spence (1894 – 1981) was so popular and prolific in her heyday that it’s hard to fathom her decline into obscurity. Like many of her contemporaries who bloomed during the Harlem Renaissance, she was multitalented—a writer and playwright as well as an actress and teacher. She authored some fourteen plays, of which five were published.

Spence, an immigrant from the British West Indies, believed that plays were meant to be fun and entertaining. Though this went against the prevailing notion that the purpose of all art was to agitate for social justice, she was a highly visible member of the Black theater community of the Harlem Renaissance, and one of its most popular.

Later, Spence became an important mentor to renowned theatrical producer Joseph Papp, who founded The Public Theater and the Shakespeare in the park theater festival in New York City. They encountered one another when she was the only Black teacher in his predominantly white high school; he described her as “the most influential force” in his life.

Spence’s plays included in this list are from 1923 – 1929, except for The Whipping, which is dated 1934: The Starter; On Being Forty; Foreign Mail; Fool’s Errand; Her; Hot Stuff; The Hunch; Undertow; Episode; La Divina Pastora; The Whipping.

. . . . . . . . . . .

RELATED CONTENT

Renaissance Women: 13 Female Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance to Rediscover and Read

The post 7 Black Women Playwrights of the Early 20th Century appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 31, 2022

The Pure and the Impure by Colette (1932)

The Pure and the Impure by Colette, a strange work first published in 1932, feels less like a novel and more like a series of loosely stitched together character sketches. Indeed it is just that, of the gay and lesbian demimondaine societies in the Paris of Colette’s time. This deep dive into The Pure and the Impure is excerpted from Text Acts: Eroticism in 20th-Century Literature, volume 2* by Francis Booth. Reprinted by permission.

All but one of the characters are unnamed but are presumably real people that Colette knew. Janet Flanner, who was Paris correspondent for The New Yorker from 1925 onwards, and published plenty of her own sketches of Paris society, said of The Pure and the Impure:

“She used her customary semi-fictional formula to report on the behavior, the mores, reflexes, instincts of women, especially as sentient, desiring creatures drawn to similarities and even to substitutes. Colette, as author, confronts the reader at the same time in a somewhat fierce intimacy, with her personal remembrances, observations, and exact images, all dealing basically with the phenomenon of eroticism.

Colette’s understanding of the male sex amounted to an amazing identification with man per se, to which was added her own uterine comprehension of women, more objective than feminine. One can think of no other female writer endowed with this double comprehension whereby she understood and accepted the naturalness of sex wherever found or however fragmented and re-apportioned. She seemed to have a hermaphroditic duality in her understanding and twofold loyalties.”

Colette is indeed equally at home in the society of adulterous older women, gay men, and transgender women in this book, as no doubt she was in real life. Given that it was published only four years after Radclyffe Hall’s banned and despised The Well of Loneliness, which does not contain any references to sex or sexuality – the furthest it goes is a one-sentence description of a kiss between two women – it seems amazing that Colette’s book was ever published, though it was written in French and published in Paris.

. . . . . . . . .

More about Colette

. . . . . . . . . .

It almost seems as if Colette is trying to push every button that would make male censors apoplectic. Close to the beginning, there is a scene of female orgasm: the male censors, even if they admitted that there was such a thing, would hate to see it in print, especially as it takes place in an opium den; drugs and female sex in one scene — horrors!

“The narrow staircase of polished wood creaked under some footsteps, which then sounded on the balcony above me, where could be heard the rustling of silk, the light impact of pillows thrown upon the echoing floorboards, and silence closed in again. But from the depths of this very silence a sound imperceptibly began in a woman’s throat, at first husky, then clear, asserting its firmness and amplitude as it was repeated, becoming clear and full like the notes the nightingale repeats and accumulates until they pour out in a flood of arpeggios …

Up there on the balcony a woman was trying hard to delay her pleasure and in doing so was hurrying it towards its climax and destruction, in a rhythm at first so calm and harmonious, so marked that I involuntarily beat time with my head, for its cadence was as perfect as its melody.”

But wait — there’s worse. We then discover that the woman in question, Charlotte, was not only ‘rather plump and resembled the favourite models of Renoir,’ but that she was ‘probably forty-five years old.’ What? says the censor, going red in the face: even plump, middle-aged women have orgasms?

Apparently, they do, but that is not even the worst of it: it turns out the man involved in the orgasm was a fair-haired boy, much younger than her. And then, just when the censor is about to pass out from apoplexy, the narrator reveals the shocking truth: the woman faked the orgasm to please the boy.

“I recalled the romantic reward she had granted the young lover, the almost public display of pleasure she had made in that nightingale lament, those full notes reiterated again and again, precipitated until their trembling equilibrium broke in a climax of torrential sobbing … I considered the young lover’s happiness was great when measured by the perfect dupery of the woman who thus subtly contrived to give a weak and sensitive boy the very highest concept of himself that a man can have.”

Which is the more outrageous for the male, patriarchal, misogynistic censor: showing a woman having an orgasm with a boy, or showing a woman faking that orgasm? ‘Am I, then,’ she says later, ‘going to find myself, in the first pages of a book, declaring that men are of less use to women than women are to men? We shall see.’ We do and they are.

Writing freely about female sexuality

Having now made sure that the censor is dead of a heart attack, Colette feels free to talk freely and in great depth about female sexuality, lesbianism and homosexuality. She even feels free to use the ‘c’ word (le con in French; just to remind you that con is a masculine noun, as are le vagin, le clitoris and l’orgasme).

She is talking here with the British-born, French-speaking Sapphic poet Renée Vivien, the only character in the book who is referred to by her real name, as she was already long dead. They are talking about a male poet. Vivian says, ‘I don’t want to hear any more about him or his verses tonight. He has no talent …’

One of the few straight men Colette knows, whom she calls Damien, is a womanizer, a Don Juan; like all men of this type, he is never satisfied by a woman, never feels any form of partnership or equality with them; he has ‘the same concept of a lover that used to be a characteristic of young girls, who could not imagine a warrior except with his weapon drawn or a lover except one ready at any moment to prove his love.’

He tells her that, ‘on that score the women I’ve known have never had any reason to complain. I educated them well. But as for what they ever gave me in exchange…’ The narrator wonders:

“… what would he have said had he ever met the woman who, out of sheer generosity, fools the man by simulating ecstasy? But I need not worry on that score: most surely he encountered Charlotte, and perhaps more than once. She produced for him her little broken cries, while she turned her head aside, and while her hair veiled her forehead, her cheek, her half-shut eyes, lucid and attentive to her master’s pleasure… The Charlottes of this world nearly always have long hair.”

Having begun the narrative in an opium den, the narrator tells us that, for her, sex is no more dangerous a habit than smoking tobacco, either for men or for women: ‘The habit of obtaining sexual satisfaction is less tyrannical than the tobacco habit, but it gains on one. O voluptuous pleasure, O lascivious ram, cracking your skull against all obstacles, time and again!’

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Pure and the Impure by Colette

on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Many of Colette’s circle were women who dressed and acted in the most masculine way possible; after World War I they were very few young men in society and, perhaps subliminally, many cultured and educated lesbians in a certain, closed, secluded part of Paris society, and also of British society, as chronicled by Radclyffe Hall.They filled the void as best they could, though that was not always enough. In the breaking down of class barriers that followed the War, these secluded societies found it far more difficult to hide themselves.

“How timid I was, at that period when I was trying to look like a boy, and how feminine I was beneath my disguise of cropped hair. ‘Who would take us to be women? Why, women.’ They alone were not fooled. With such distinguishing marks as pleated shirt front, hard collar, sometimes a waistcoat, and always a silk pocket-handkerchief, I frequented a society perishing on the margin of all societies.

Although morals, good and bad, have not changed during the past twenty-five or thirty years, class consciousness, in destroying itself, has gradually undermined and debilitated the clique I am referring to, which tried, trembling with fear, to live without hypocrisy, the breathable air of society… The adherents of this clique of women exacted secrecy for their parties, where they appeared dressed in long trousers and dinner jackets and behaved with unsurpassed propriety.”

Many of these cross-dressing women had their girlfriend, their protégée, their petite amie, ‘rather rude young creatures, insinuating and grasping. Not surprising, this, for these ladies in male attire had, by birth and from infancy, a taste for below stairs accomplices.’

But not all of Colette’s acquaintances are comfortable with these cross-dressing women. One says to her, ‘you see, when a woman remains a woman, she is a complete human being. She lacks nothing, even insofar as her amie is concerned. But if ever she gets it into her head to try to be a man, then she’s grotesque.’ For Colette, the only thing of which she disproves is ‘Sapphic libertinage;’ for her, fidelity rather than sexual gratification is the most important thing.

“Two women very much in love do not shun the ecstasy of the senses, nor do they shun a sensuality less concentrated than the orgasm, and more warming. It is this unresolved and demanding sensuality that finds happiness in an exchange of glances, an arm laid on a shoulder, and is thrilled by the odour of sun-warmed wheat caught in a head of hair. These are the delights of a constant companionship and shed habits that engender and excuse fidelity.”

. . . . . . . . .

Text Acts, Vols. 1, 2, &3 on Amazon U.S.*

and Amazon U.K.*

. . . . . . . . . .

Colette knew Marcel Proust slightly and read all of his works. She doesn’t disapprove of his emphasis on homosexuality, but strongly objects to his portrayal of women. She feels, and indeed demonstrates later in the book, that she has an intimate understanding of the homosexual man, but that he does not have the same understanding of women.

“Ever since Proust shed light on Sodom, we have had a feeling of respect for what he wrote, and would never dare, after him, to touch the subject of these hounded creatures, who are careful to blur their tracks and to propagate at every step their personal cloud, like the cuttlefish.

But – was he misled, or was he ignorant? – when he assembles a Gomorrah of inscrutable and depraved young girls, when he denounces an entente, a collective tea, a frenzy of bad angels, we are only diverted, indulgent, and a little bored, having lost the support of the dazzling light of truth that guides us through Sodom.

This is because, with all due deference to the imagination or the error of Marcel Proust, there is no such thing as Gomorrah. Puberty, boarding school, solitude, prisons, aberrations, snobbishness – they are all seedbeds, but too shallow to engender and sustain a vice that could attract a great number or become an established thing that would gain the indispensable solidarity of its votaries. Intact, enormous, eternal, Sodom looks down from its heights upon its puny counterfeit.”

. . . . . . . . .

Short and Sweet Quotes by Colette

. . . . . . . . .

The language of passion

Colette seems to have been welcomed into the gay male society of Paris, though mainly as an observer. If anything, she considers them more well-adjusted than lesbian society, especially the transgender lesbians who are obsessed with masculinity: gay men are not obsessed with women.

“They allowed me to share with them their sudden outbursts of gaiety, so shrill and revealing. They appreciated my silence, for I was faithful to their concept of me as a nice piece of furniture and I listened to them as if I were an expert. They got used to me, without ever allowing me access to a real affection. No one excluded me – no one loved me. I owe a great deal to their cold friendship, to their fierce critical sense.

They taught me not only that a man can be amorously satisfied with a man but that one sex can suppress, by forgetting it, the other sex. This I had not learned from the ladies in men’s clothes, who were preoccupied with men, who were always, with suspect bitterness, finding fault with men. My strange homosexual friends did not talk about women, except distantly and condescendingly… Absent yet present, a translucent witness, I enjoyed an indefinable piece, accompanied by a kind of conspiratorial pride.

I heard on their lips the language of passion, of betrayal and jealousy, and sometimes of despair – languages with which I was all too familiar, I had heard them elsewhere and spoke them fluently to myself.”

Colette certainly spoke and wrote the languages of passion, one of the first and still one of the best women to do so.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Pure and the Impure by Colette (1932) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 23, 2022

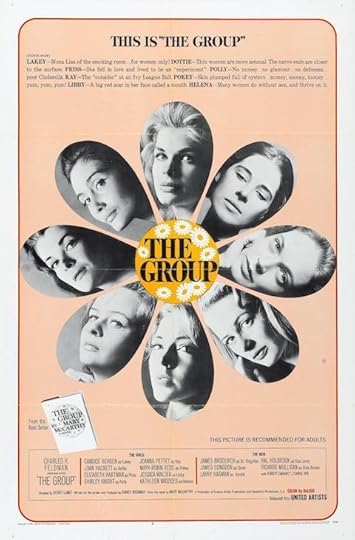

The Group by Mary McCarthy (1963)

The Group (1963), is arguably American author Mary McCarthy’s best-known work. Known for trenchant works of fiction and nonfiction, McCarthy likely would not have chosen this juicy, gossipy novel, with elements of autobiography, to be a great part of her lasting legacy, as we’ll see later.

The Group hit the New York Times Bestseller List several weeks after its publication and stayed there for nearly two years. Considered rather scandalous for its time, it touched on issues of contraception, abortion, mental illness, male chauvinism, and lesbian relationships, as experienced by young women in the 1930s.

The book was banned in several countries, but that didn’t deter it from being a huge international hit. The film version of The Group premiered in 1966, featuring a stellar cast (including a breakthrough role for Candice Bergen) and direction by Sidney Lumet.

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Mary McCarthy

. . . . . . . .

The book follows the lives of a group of friends from Vassar College (which McCarthy attended), from the time of their graduation in 1933. The young women — Kay, Dottie, Mary, Press, Libby, Elinor (Lakey), Helena, and Polly, are beginning to experience the trials of young adulthood just as America is gripped by the Great Depression. Life unfolds with its joys and triumphs, as well as its sorrows and challenges.

Here’s a succinct description from the 1991 Mariner Books edition:

“Written with a trenchant, sardonic edge, The Group is a dazzlingly outspoken novel and a captivating look at the social history of America between two world wars. Juicy, shocking, witty, and almost continually brilliant.

Mary McCarthy’s most celebrated novel follows the lives of eight Vassar graduates, known simply to their classmates as ‘the group.’ An eclectic mix of personalities and upbringings, they meet a week after graduation to watch Kay Strong get married.

After the ceremony, the women begin their adult lives — traveling to Europe, tackling the worlds of nursing and publishing, and finding love and heartbreak in the streets of New York City.

Through the years, some of the friends grow apart and some become entangled in each other’s affairs, but all vow not to become like their mothers and fathers. It is only when one of them passes away that they all come back together again to mourn the loss of a friend, a confidante, and most importantly, a member of the group.”

Initial critical receptionThe Group was widely reviewed, often with breathless attention to its more controversial details. Male critics were occasionally harsh. Norman Mailer, known for being a chauvinistic jerk, wrote in the New York Review of Books: “Her book fails as a novel by being good but not nearly good enough … she is simply not a good enough woman to write a major novel.”

A 2017 Guardian article reporting on that year’s reissue of The Group, reflected on the book’s impact on McCarthy’s life and reputation:

“For years afterwards, McCarthy received letters from irate readers accusing her of a ‘perverted outlook on life.’ She was shunned by her former university contemporaries, many of whom felt they had been mercilessly pilloried in the book. Despite the fact that The Group went on to top the New York Times bestseller list for almost two years, the experience was still raw enough for McCarthy to admit in a 1989 newspaper interview shortly before her death that she thought The Group had ‘ruined my life.’”

Other critics were kinder, considering the novel for its intrinsic value rather than what the reviewer personally thought of Mary McCarthy. Critic David Boroff wrote: “Miss McCarthy has come through brilliantly. It is sheer exhilaration to watch her nimble intelligence at work, great joy to read her rich and supple prose. The Group clearly is one of the best novels of the decade.”

Some of the real-life women who were fictionalized — McCarthy’s Vassar classmates — recognized themselves in the novel and were none too happy.

A contemporary reconsideration

The long view has been kind to The Group. With the benefit of hindsight, critic Julia Armfield named The Group the best book of 1963 in a 2019 piece in Granta.

A 2019 essay in LitHub by Mikaella Clements directs the contemporary reader to Please Take this Summer to Become Obsessed with the Group — with the tagline, Mary McCarthy’s 1960s novel about the 1930s feels like 2019. She writes that reading The Group is:

“… an obsessive experience, and one that, despite McCarthy’s and the novel’s fame, still feels like discovering a thrilling secret. Its prose shows a master stylist at work, its aesthetics are striking—all ivory-tipped cigarettes, hand-pureed pâté, Vassar socialists in dungarees—and it has a surprise queer romance that twists the whole narrative into new shape. It’s my new standard for a summer read: lavish, hilarious, smart, and mean, like a glamorous friend you’re torn between fearing and crushing on.”

In Vassar Unzipped, a 2013 Vanity Fair piece celebrating the 50th anniversary of the novel, Laura Jacobs “explores why the book still dazzles as a generational portrait, falters as fiction, and blighted McCarthy’s life.”

Fascinating fact! The Group served as an inspiration for Candace Bushnell for her 1996 novel, Sex and the City, which was the basis, of course, for the massively successful TV series and subsequent films. Bushnell wrote the foreword to a 2009 reissue of The Group.

Other contemporary reconsiderations call The Group “timeless.” Perhaps McCarthy was ahead of her time, but it’s also depressing to think that today’s women continue to struggle with the same issues as those of the 1930s.

. . . . . . . .

Though it has always received mixed reviews, the 1966 film adaptation

has gained favor as a cultural touchstone.

. . . . . . . .

From the original review in The Kansas City Star, August 25, 1963: Vassar May Confuse Them, But It Can’t Defeat Them: The Group by Mary McCarthy, reviewed by Richard Rhodes:

Ten years in the lives of eight girls, Vassar Class of ’33 — that is The Group, an excellent successor to Mary McCarthy’s earlier novels, witty, gossipy, crammed with artifacts of the 1930s, occasionally cruel, outstandingly realistic.

Besides “The Group” there are also fathers and husbands, babies under rigid feeding schedules, casseroles made with Campbell’s Soup, the new efficiency apartments, and the just-completed Museum of Modern Art.

That so much paraphernalia can be closet in one book is a triumph of the author’s style, which combines the lilting patois of an Irish washerwoman with the factual journal of a literate anthropologist. The Group’s dated slang, for example, she remembers perfectly.

“Kay and Harald had just about fainted when they heard what Dottie had been up to, behind their backs.” What Dottie has been up to, early in the novel, was a one-night stand with a man she had met only the same afternoon, at Kay’s wedding. Dottie, so innocent that her greatest worry was that Dick didn’t kiss her before they bedded.

This confusion between what Dottie’s Vassar education convinced her is “enlightened,” and what her family life and social values prepared her for, is typical of most of the members of the Group. They are sprung from a college staffed by scientific suffragettes, but they have only half-learned or half-believed, their lessons.

. . . . . . . . .

The Group on bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

With commendable courage and amusing silliness, they usually muddle through. They often fire their heaviest artillery at small targets, so that the question of whether to get dinner from a can or from mother’s recipe book invariably involves them in the question of whether to be a “new” woman, or, horrors, and old fogy.

When their education fails them they revert to type and valiantly stick together. If Kay has the enlightened daring to be married in a brown dress without the benefit of mother, father, or virginity, they will loyally attend, clucking and a little wide-eyed.

If everyone insists Polly’s father is a potentially dangerous manic-depressive, Polly will nevertheless take him into her apartment and support as best she can his extravagant eccentricities.

If Press Hartshorn Crockett is too timid to give in to her natural desires to play with her baby (her pediatrician husband insists it is to be picked up only for feedings), she will still envy and secretly admire Norine, who sunbathes her son naked in Central Park, and feeds him table scraps at three months: “… already he had shown a taste for Italian spaghetti.”

Press and Norine’s conversation in the park, late in the novel, might very well sum up the conflict which enlivens the book:

“You really think our education was a mistake?” Press asked anxiously. Sloan had often expressed the same view, but that was because it had given her ideas he had disagreed with.

“Oh, completely,” said Norine. “I’ve been crippled for life.” She stretched.

Norine could stretch in boredom at Priss’s question. Norine, a non-Group girl, survived Vassar almost untouched, reverting to type soon after graduation — she is slovenly, sensual, relaxed, and often immoral. She doesn’t have the conflicts that Press and The Group have.

But how much even they are “crippled for life” remains, Mary McCarthy makes clear, to be seen. Sooner or later most of them learn to manage the plain business of life —marriage, family problems, money problems babies, keeping house. Probably all survived to become good citizens and settled members of their appropriate social class, with babies and suburban homes and second cars and nostalgic memories of their years at Vassar.

Since society and their education were mutually exclusive, most of the Group undoubtedly found it easier to jettison the latter.

All except Mary McCarthy, Vassar class of ’33, who now can claim among her many charms and curios the honor of having elevated the inflections of girlish gossip to the level of an effective, ambient prose style.

An Irish orphan girl from Seattle with a good ear and a forthright pen, she now lives with her husband in Paris. And after all these years she has finally got “The Group” together again.

More about The Group A Critical Reading of The Group Mary McCarthy’s The Group: Three Queer Readings Reader discussion on Goodreads. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Group by Mary McCarthy (1963) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 18, 2022

In Her Own Words: Joan Didion Quotes on Life, Love, & Writing

There are hugely influential writers who inspire others within their lifetimes, and Joan Didion ( 1934 – 2021 ) was certainly one of them. But it’s after her passing that everything she wrote seems to resonate even more, because we realize that there will be no further words of wisdom. This selection of quotes by Joan Didion highlights her unique talent at examining life — its joys, sorrows, and challenges.

In her tribute to Joan Didion upon her passing, Nancy Snyder wrote, “Joan Didion had her sublime sentences filled with a myriad of details to convey her personal and wholly authentic stories. She wrote about nearly every cultural and political upheaval that transformed the U.S. from the 1960s to the present day.”

Another, equally significant part of Didion’s writing is her observations on day-to-day things in a way that many of us already think about. But the manner in which she expressed them was anything but commonplace. She faced tragedies, like the loss of a beloved husband and a daughter, with words that cannot help but move.

. . . . . . . . .

“To free us from the expectations of others, to give us back to ourselves – there lies the great, singular power of self-respect.” (“Self-respect: Its Source, Its Power” (essay originally published in Vogue, 1961)

. . . . . . . . .

“I am still committed to the idea that the ability to think for one’s self depends upon one’s mastery of the language.” (Slouching Towards Bethlehem, 1968)

. . . . . . . . .

“Character – the willingness to accept responsibility for one’s own life – is the source from which self-respect springs.” (Slouching Towards Bethlehem, 1968)

. . . . . . . . .

Joan Didion, photo by Brigitte Lacombe

. . . . . . . . .

“A writer is a person whose most absorbed and passionate hours are spent arranging words on pieces of paper. I write entirely to find out what’s on my mind, what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I’m seeing and what it means, what I want and what I’m afraid of.” (“On Keeping a Notebook,” essay included in Slouching Towards Bethlehem, 1968)

. . . . . . . . .

“So the point of my keeping a notebook has never been, nor is it now, to have an accurate factual record of what I have been doing or thinking. That would be a different impulse entirely, an instinct for reality which I sometimes envy but do not possess.” (“On Keeping a Notebook,” essay included in Slouching Towards Bethlehem, 1968)

. . . . . . . . .

“I’m not telling you to make the world better, because I don’t think that progress is necessarily part of the package. I’m just telling you to live in it. Not just to endure it, not just to suffer it, not just to pass through it, but to live in it. To look at it. To try to get the picture. To live recklessly. To take chances. To make your own work and take pride in it. To seize the moment. And if you ask me why you should bother to do that, I could tell you that the grave’s a fine and private place, but none I think do there, embrace. Nor do they sing there, or write, or argue, or see the tidal bore on the Amazon, or touch their children. And that’s what there is to do and get it while you can and good luck at it.” (UC Riverside commencement address, 1975)

. . . . . . . . .

“I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear.” (“Why I Write,” essay originally published in the New York Times Book Review , 1976)

. . . . . . . . .

“In many ways writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. It’s an aggressive, even a hostile act. You can disguise its qualifiers and tentative subjunctives, with ellipses and evasions—with the whole manner of intimating rather than claiming, of alluding rather than stating—but there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space.” (“Why I Write,” essay originally published in the New York Times Book Review , 1976)

. . . . . . . . .

“The fancy that extraterrestrial life is by definition of a higher order than our own, is one that soothes all children and many writers.” (The White Album, 1979)

. . . . . . . . .

The Center Will Not Hold is the excellent

2017 documentary on Joan Didion

. . . . . . . . .

“We are imperfect mortal beings, aware of that mortality even as we push it away, failed by our very complication, so wired that when we mourn our losses, we also mourn, for better or for worse, ourselves. As we were. As we are no longer. As we will one day not be at all.” (The Year of Magical Thinking, 2005)

. . . . . . . . .

“A single person is missing for you, and the whole world is empty.” (The Year of Magical Thinking, 2005)

. . . . . . . . .

“I know why we try to keep the dead alive: we try to keep them alive in order to keep them with us. I also know that if we are to live ourselves there comes a point at which we must relinquish the dead, let them go, keep them dead. ” (The Year of Magical Thinking, 2005)

. . . . . . . . .

“If you are doing a piece about somebody, even if you admire them tremendously and express that in the piece, express that admiration, if they’re not used to being written about, if they’re civilians … they’re not used to seeing themselves through other people’s eyes. So you will always see them from a slightly different angle than they see themselves, and they feel a little betrayed by that.” (Academy of Achievement Interview, June 3, 2006)

. . . . . . . . .

“You get the sense that it’s possible simply to go through life noticing things and writing them down and that this is OK, it’s worth doing. That the seemingly insignificant things that most of us spend our days noticing are really significant, have meaning, and tell us something” ( The Paris Review interview, 2006)

. . . . . . . . .

“When we talk about mortality we are talking about our children.” (Blue Nights, 2011)

. . . . . . . . .

“When we lose that sense of the possible we lose it fast. One day we are absorbed by dressing well, following the news, keeping up, coping, what we might call staying alive; the next day we are not.” (Blue Nights, 2011)

. . . . . . . . .

“Do not whine … Do not complain. Work harder. Spend more time alone.” (Blue Nights, 2011)

. . . . . . . . .

Joan Didion books on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post In Her Own Words: Joan Didion Quotes on Life, Love, & Writing appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 17, 2022

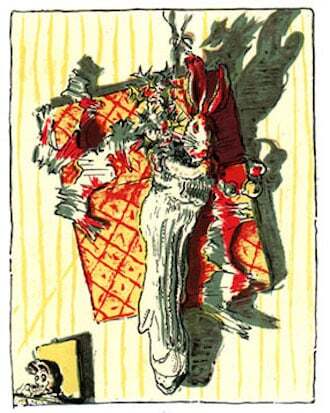

The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams turns 100

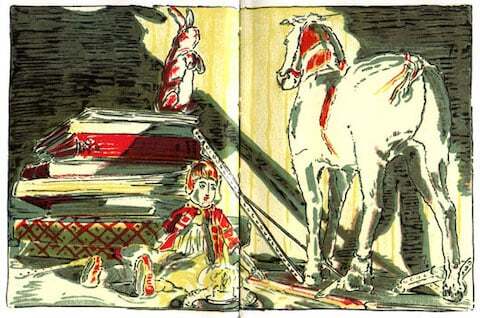

The Velveteen Rabbit (or How Toys Become Real) by Margery Williams was published in 1922 and has been in print ever since. The best-known book by British-born author Margery Williams Bianco (1881 – 1944), it has been a children’s classic for generations. In 2022, we celebrate the hundredth anniversary of its publication.

The story is at its heart about the transformative power of love. The original edition was illustrated by William Nicholson, and has been through numerous editions, with artwork by various illustrators.

A 1924 review in The Detroit News observed, “How Toys Become Real is the inner story of The Velveteen Rabbit, but there’s no syrupy moral to it. It’s just that if a toy is loved enough, it finally, through the alchemy of love, becomes real.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Plot summaryThe Velveteen Rabbit is the story of a stuffed toy rabbit who wishes to become real. The title rabbit is a Christmas gift for a child we come to know only as “the Boy.” The book begins:

“There was once a velveteen rabbit, and in the beginning he was really splendid. He was fat and bunchy, as a rabbit should be; his coat was spotted brown and white, he had real thread whiskers, and his ears were lined with pink sateen. On Christmas morning, when he sat wedged in the top of the Boy’s stocking, with a sprig of holly between his paws. The effect was charming.”

The Boy ignores the velveteen rabbit for a time, preferring to play with fancier, more modern toys.

The oldest toy in the nursery is the Skin Horse, who was passed down by the Boy’s uncle. He tells the rabbit of how toys can become real through the love of the children they belong to.

“The Skin Horse had lived longer in the nursery than any of the others. He was so old that his brown coat was bald in patches and showed the seams underneath, and most of the hairs in his tail had been pulled out to string bead necklaces. He was wise, for he had seen a long succession of mechanical toys arrive to boast and swagger, and by-and-by break their mainsprings and pass away, and he knew that they were only toys, and would never turn into anything else. For nursery magic is very strange and wonderful, and only those playthings that are old and wise and experienced like the Skin Horse understand all about it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The rabbit fervently wishes to become real through the Boy’s love, yet has some misgivings:

“He longed to become Real, to know what it felt like; and yet the idea of growing shabby and losing his eyes and whiskers was rather sad. He wished that he could become it without these uncomfortable things happening to him.”

It takes some time, but after the Boy takes the velveteen rabbit as sleeping companion one night, he begins to love him at last.

“Weeks passed, and the little Rabbit grew very old and shabby, but the Boy loved him just as much. He loved him so hard that he loved all his whiskers off, and the pink lining to his ears turned grey, and his brown spots faded. He even began to lose his shape, and he scarcely looked like a rabbit any more, except to the Boy. To him he was always beautiful, and that was all that the little Rabbit cared about. He didn’t mind how he looked to other people, because the nursery magic had made him Real, and when you are Real shabbiness doesn’t matter.”

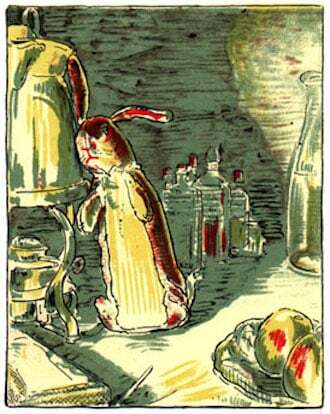

When the Boy contracts scarlet fever, the rabbit says by his side. When the doctor orders a trip to the seaside so the the patient and recover, and at the same time, to disinfect the nursery, all the books and toys are to be burned.

The velveteen rabbit is put into a sack and left outside. A tear falls from his eye as he thinks of the Boy.

“Of what use was it to be loved and lose one’s beauty and become Real if it all ended like this? And a tear, a real tear, trickled down his little shabby velvet nose and fell to the ground.”

When the teardrop touches the ground, a flower springs up at once, and out steps a fairy.

The fairy tells the rabbit that because he had become real to the Boy who loved him so dearly, she would make him real to all the world. In the forest, in view of the other rabbits, the fairy kisses the velveteen rabbit, who becomes a real rabbit — a handsome one, at that — and joins the others.

A few seasons pass, and a spring day finds the Boy playing out in the woods behind the house:

“Autumn passed and Winter, and in the Spring, when the days grew warm and sunny, the Boy went out to play in the wood behind the house. And while he was playing, two rabbits crept out from the bracken and peeped at him. One of them was brown all over, but the other had strange markings under his fur, as though long ago he had been spotted, and the spots still showed through. And about his little soft nose and his round black eyes there was something familiar, so that the Boy thought to himself:

“Why, he looks just like my old Bunny that was lost when I had scarlet fever!”

But he never knew that it really was his own Bunny, come back to look at the child who had first helped him to be Real.”

The Velveteen Rabbit was well received from the time it first came out, becoming a beloved childhood classic and garnering awards and accolades for decades to come. Following is a review that appeared a couple of years after it was published.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Velveteen Rabbit (various editions) on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review in The Birmingham News, Birmingham, AL, April, 1924, by Mary E. Foster: Do you know the velveteen rabbit? He came one Christmas morning with “the Boy’s” other toys; there he “sat wedged in the top of the Boy’s stocking, with a sprig of holly between his paws …”

For many long months he lived in the nursery where the mechanical toys treated him with superior airs, and only the old Skin Horse was kind to him. They became great friends, and from his years of experience the Skin Horse told the Velveteen Rabbit of life and how a toy could become “real.”

The Skin Horse had been made “real” because the Boy’s uncle had loved him many years ago and one day the Rabbit asked him:

“What is real, does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?”

“Real isn’t how you are made,” said the Skin Horse. “It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long, time, not just to play with, but really loves you, then you become Real.”

“Does it hurt?” asked the rabbit.

“Sometimes, but when you are real you do not mind being hurt,” said the Skin Horse.

“Does it happen all at once, like being wound up, or bit by bit?”

“It doesn’t happen all at once. You become,” said the Skin Horse. “It takes a long time. That’s why it doesn’t often happen to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept. Generally by the time you are real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don’t matter at all, because once you are real you can’t be ugly, except to people who don’t understand.”

What child of five or six (or really, a child of any age) could fail to unconsciously realize what his love for his toys can mean to them after such a story, and what grown-up but will stop to think before they lightly discard some well-worn treasure which to them has served a purpose?

Books like this will be real friends of the children who read them or to whom they are read. Its print is large and its many pictures irresistible. Children of all ages will love the Velveteen Rabbit and the wise Skin Horse to the very end. Picture books can be of things we know every day, told in a delightful way and made “real” through love.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams turns 100 appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 16, 2022

Sydney Taylor, Author of All-of-a-Kind Family

Sydney Taylor (born Sarah Brenner; October 30, 1904 – February 12, 1978) was an American author best known for All-of-a-Kind Family. This series of autobiographical children’s novels portrays the life of an Eastern European Jewish immigrant family in New York City in the early twentieth century.

Though she wrote several other children’s novels, the five books in the All-of-a-Kind Family series proved to be her lasting legacy, earning a devoted audience for their warm and loving depiction of Jewish life in early twentieth-century America.

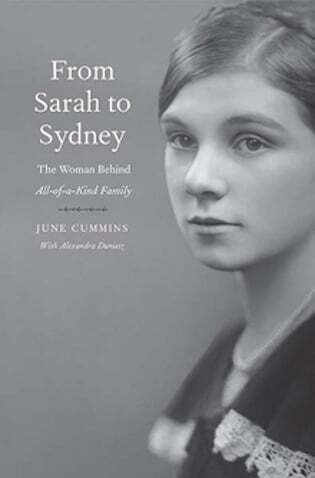

Photo above right, Sydney Taylor (Sarah Brenner) in the 1920s, from the private collection of her daughter, Jo Taylor Marshall.

Becoming an author unexpectedly

For New York City housewife Sydney Taylor, November 21, 1950, began as just another ordinary day. But after that day’s mail came, there was a significant change of status — the daughter of Eastern European Jewish immigrants had at once become a professional writer.

The letter that Sydney opened that day, addressed from Follett Publishers, informed her that she was the first-place winner in their Children’s Manuscript Competition. The prize included a gold medal, publication of the manuscript, and a cash award of $3,000 (equal to more than $30,000 today). The kicker was that she had no idea that she’d been entered into the contest.

After a brief conversation with her husband, Ralph Taylor, the mystery of the Follett prize was solved: the previous summer, Ralph had his secretary type his wife’s manuscript, which he’d found stashed in the closet. Ralph was convinced the stories were too good and too significant for them to go unnoticed by children’s book publishers.

. . . . . . . . . .

The real-life “all-of-a-kind” family —

Sarah (Sydney) is second from left, holding an apple

. . . . . . . . . .

The manuscript Sydney had written was the first in the five-book children’s historical fiction series, All of-A-Kind Family. The series was nearly autobiographical for Sydney. The tales reflected the real-life experiences of her own family, the Brenners, Jewish emigrants from Germany and Poland.

In 1901, Morris and Cecilia Brenner joined the wave of tens of thousands of European Jews coming to America, flush with big dreams and bigger ambition.

Sydney Taylor liked to tell these stories of her family in New York City’s Lower East Side to her daughter, Joanne, when she was young. These family tales were of her mother’s life growing up with four sisters (later there would be one brother, Charlie) in the Lower East Side in the early twentieth century. Joanne so enjoyed the tales that Sydney began writing them down.

Sydney’s bedtime stories for Joanne reflected something larger, more historical than simply the Brenner family chronicles. When Sydney began recording her family’s Jewish immigrant life in the early twentieth century, she was preserving fragments of the experience of millions of Eastern European Jewish immigrants.

In 1880, seventy-five percent of the world’s Jewish population lived in Europe and a mere three percent of world Jewry lived in the U.S. By 1920, the demographics had climbed to twenty-three percent of the Jewish population living in the U.S. During those forty years, over two million European Jews had landed in New York harbor.

The Brenner’s voyage to America

When Morris and Cecilia Brenner voyaged to America in 1901, their traveling party included fifteen-month-old daughter Ella, Cecilia’s brother (also named Morris), and an uncle, Hyam-Yonkel.

To save every penny, they traveled in steerage for their twelve-day voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. Unfortunately, from the first day of their ocean journey, Cecilia became severely ill with seasickness that had Morris attempting to care for his ill wife. Soon, Cecilia needed her husband’s care every hour of the day and night.

That left the responsibility of caring for Ella to Uncle Hyam-Yonkel and her brother Morris. One day, much to the surprise and shock of Uncle Hyam-Yonkel and brother Morris, Ella had slipped under the ship’s railings and had almost toppled overboard. Uncle Hyam-Yonkel went into action — he grabbed Ella’s long gown and carried her to safety.

Another favorite Brenner family tale of their voyage to America was Morris’s reaction when he first saw the Statue of Liberty. As their ship was coming into New York labor, Morris became so emotionally moved by the sight of Lady Liberty and the poem at the statue’s base by Emma Lazarus (“Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free”) that when the family finally disembarked the ship and cleared customs, Morris insisted that the family’s first stop would be locating the office where he could become a U.S. citizen. Of course, things didn’t work that way.

. . . . . . . . . .

Sydney in the 1950s

. . . . . . . . . .

Upon first arriving, the family stayed with Morris’s maternal aunt and uncle in their Lower East Side apartment until they found their own first home, an apartment nearby.

The Lower East Side was one of the world’s most densely populated areas, with a thousand residents per square acre. Yiddish was the dominant language heard in the streets. Immigrant Jews were packed into tenement housing; the apartments were impossible to clean and had inadequate ventilation, heat, and lighting.

The tenements had no hot water and often, only a communal toilet in hallways. It wasn’t unusual for twelve people to live in two rooms.

The Brenners’ first New York home of their own was on East 5th Street, a three-room apartment with the front room given out to Cecelia’s brother, and Uncle Hyam-Yonkel. After their second daughter, Henrietta, was born, the Brenners moved across the street to 708 East 5th Street. It was here that Sarah, the future Sydney Taylor, was born on October 30, 1904.

There would be two more daughters, Charlotte and Gertrude, spaced about two years apart, and after a longer stretch, brother Charlie was born. The real-life All-of-a-Kind-Family, plus one, was complete.

As conveyed in the five lightly fictionalized All-of-a-Kind Family books, Sarah and her four sisters excelled in the local public school, went to the Hamilton Fish Park Branch and Seward Branch Public Libraries on Friday afternoons, observed all the Jewish holidays and the Sabbath, helped their Mama with the housework, and every daughter, except for Henrietta, obeyed their parents.

What was also real, but not depicted in the series, was the unfortunate bouts of severe depression that plagued Cecilia. Otherwise, life for the five Brenner sisters unfolded around their public schools, their synagogue, and their friends and family.

Sarah becomes Sydney

When she was sixteen years old and a student at Morris High School, Sarah Brenner changed her first name to Sydney. It was the name she chose for her planned career in the theatre arts.

Sydney was forced to leave high school two years early to supplement the Brenner family income. She worked in the clerical field and continued to educate herself at night school.

In 1925, Sydney married Ralph Taylor, a pharmacist and businessman. Sydney acted in The Lenox Hill Players, a distinguished New York theatre company, from 1927 to 1929. Then, she became a professional dancer with the Martha Graham Dance Company. After their daughter was born in 1935, Sydney became a full-time housewife and mother to Joanne.

. . . . . . . . . .

All-of-a-Kind Family on

Bookshop.org

* and

Amazon

*

. . . . . . . . . .

All-of-a-Kind-Family , published in 1951, became the first of a series of children’s novels about a tight-knit Jewish family at the turn of the 20th century. Ella, Henny, Sarah, Charlotte, and Gertie are five young sisters (named for Sydney and her real-life sisters0 who live with their parents in the Lower East Side of New York City.

This story and its sequels depict the joys and challenges of immigrant life, with an overriding message of family love and loyalty. Notable for its emphasis on Jewish holidays and traditions, the book and its sequels presented them as joyous occasions, without resorting to stereotypes.

Readers wanted more after the success of the first All-of-a-Kind Family. Four more volumes about the five sisters (and now, one brother) followed: More All-Of-A-Kind Family (1954) All-of-a-Kind Family Uptown (1958), All-of-a-Kind Family Downtown (1972), and Ella of All-of-a-Kind Family (1978). In the long gap between the first three installments and the last two, Sydney published several other, unrelated children’s novels. Her last book, published posthumously, was Danny Loves a Holiday (1980), also unrelated to the series.

In the last half of the twentieth century, the All-of-a-Kind Family books were the best-known children’s works depicting Jewish life in America. Read more about the series here.

. . . . . . . . . .

From Sarah to Sydney (Yale University Press, 2021)

on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

When her status changed in 1950 to that of a professional writer, Sydney became active in touring public libraries throughout New York City and New York state to encourage literacy for young readers.

She also received voluminous fan mail and answered every letter. Towards the end of her life, her favorite letters were from grandmothers who had introduced the books to their daughters — and now joyfully watched as these daughters introduced the books to their children.

In an interview, Taylor shared why these books were so personally important for her to write. “I remember when I was a little girl and read books from the library that were always about Gentile children and never about Jewish ones. So when I grew up and had a daughter of my own, I determined I’d write a book for her about Jewish children.”

In 1978, Sydney Taylor died after a long bout with breast cancer. The next year, after Ralph brought the idea to the Association of Jewish Libraries, The Sydney Taylor Award for Excellence in Children’s Literature was established. The award recognizes a children’s book that displays literary merit and authentically conveys the Jewish experience.

The four sequels to All-of-a-Kind Family were republished in 2014 by Lizzie Skurnick Books. June Cummins, who would go on to write the first full-scale biography of the author (From Sarah to Sydney, 2021) contributed new forewords for these editions.

Contributed by Nancy Snyder, who writes about women writers and labor women. After working for the City and County of San Francisco for thirty years, she is now learning everything about Henry David Thoreau in Los Angeles.

. . . . . . . . .

Sydney Taylor’s books on Amazon*

More about Sydney TaylorNovels for children

All-of-a-Kind Family (1951), illustrated by Helen JohnMore All-Of-A-Kind Family (1954), illustrated by Mary StevensAll-of-a-Kind Family Uptown (1958), illustrated by Mary StevensMr. Barney’s Beard (1961), illustrated by Charles GeerNow That You Are 8 (1963), illustrated by Ingrid FetzThe Dog Who Came to Dinner (1966), illustrated by John E. JohnsonA Papa Like Everyone Else (1966), illustrated by George PorterAll-of-a-Kind Family Downtown (1972), illustrated by Beth and Joe KrushElla of All-of-a-Kind Family (1978), illustrated by Gail OwensDanny Loves a Holiday (1980), illustrated by Gail OwensBiography

From Sarah to Sydney: The Woman Behind All-of-a-Kind Familyby June Cummins with Alexandra Dunietz (2021)

More information and sources

Jewish Women’s Archive Meet Sydney Taylor: Unsung Creator of All-of-a-Kind Family (NY Times) Wikipedia Reader discussion of Sydney Taylor’s books on Goodreads A One-of-a-Kind Biography of the Author of the ‘All-of-a-Kind Family’ Stories. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Sydney Taylor, Author of All-of-a-Kind Family appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 11, 2022

Anzia Yezierska, author of Bread Givers

Anzia Yezierska (October 29, 1880 – November 21, 1970) was a Polish-born Jewish-American writer who achieved renown for her fiction on the immigrant experience in the early twentieth century.

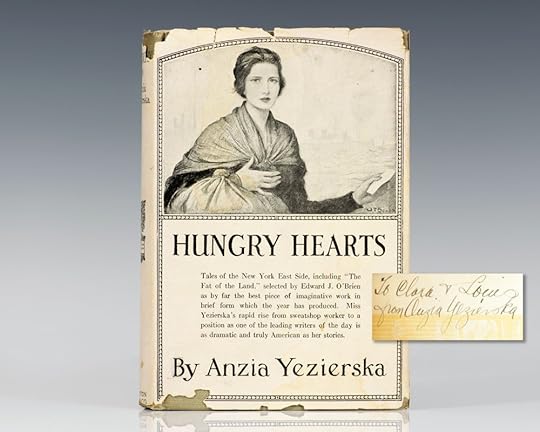

Her most notable novel has remained Bread Givers (1925). She also achieved renown with her first short story collection, Hungry Hearts (1920), and her 1923 novel, Salome of the Tenements (1923).

When her family immigrated to the U.S. in 1893, they were among the masses of Eastern European Jews who arrived between 1880 to 1924. Like many Jewish immigrants, they settled and lived in the immigrant neighborhood of the East side of Manhattan.

Early family life

Anzia Yezierska was born in Maly Plock, Poland. Her parents, Bernard and Pearl Yezierska, immigrated to America in 1893, six years after her eldest brothers had arrived and settled. They settled in the lower side of Manhattan, where most Jewish immigrants took refuge.

After arriving in the US, her family adopted Mayer as their new surname. Anzia changed her first name to Harriet (sometimes Hattie). In her late twenties, she changed it back to her original full name, Anzia Yezierska. Her father engaged in full-time study of the sacred text of the Torah and wasn’t gainfully employed.

Anzia’s mother worked at different unskilled jobs to support the family. Pressured to support her family, Anzia was forced to drop out of school after two years of elementary education. She began working a succession of domestic and factory jobs to support her family.

Eastern European culture, especially the Orthodox one to which her family belonged, didn’t support girls’ education. She and her sisters bore the brunt of this disadvantage. The boys of the family were all educated, and as adults worked in steady, reputable professions. Four of her brothers were pharmacists, another was a math teacher, and the other became an army colonel.

Education

Anzia clashed with her parents, especially her father, whose observance of the religion and Old World culture was a barrier to her full entry into American life. In search of independence and education, the young Yezierska left her home and went to Clara De Hirsch Home for Working Girls.

Anzia pursued her ambition of becoming educated wholeheartedly and with great determination. She promised the German patron in charge of the school that she would become a domestic science teacher to help improve the lives of her people.

The German patron awarded Anzia a four-year scholarship to Columbia’s Teachers College, studying domestic arts. From 1901 to 1905, Yezierska did menial work to support herself while studying in the college.

Her first job was as an elementary school teacher; she taught from 1908 to 1913. In 1913, she took a brief leave from her teaching job to attend the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, where she started pursuing the writing of fiction in earnest.

Longing to rise above her circumstances, she was somewhat hampered by her brittle personality and a measure of self-loathing. In her final book, the autobiographical Red Ribbon on a White Horse (1950), she wrote: “With a sudden sense of clarity, I realized the battle I thought I was waging against the world had been against myself, against the Jew in me.”

Personal life

In 1910, Anzia fell into a romantic relationship with Arnold Levitas, to whom she became engaged to marry. Instead, she married his friend Jacob Gordon, and due to guilt, this marriage was annulled. Anzia at once went back to Levitas, who she married in a religious ceremony. Her only daughter, Louise, was born in 1912.

In 1914, Anzia left her husband, taking her daughter to live in San Francisco where she took a job as a social worker. She had many responsibilities in that line of work, which made it challenging to take care of her daughter. She gave up custody of Louise to Levitas.

Yezierska and Levitas divorced in 1916, and the following year, having moved back to New York City, she fell in love with John Dewey, a philosopher and a professor at Colombia University. Dewey was one of the most prominent American scholars and social reform thinkers of the twentieth century. The love affair was in truth an affair, as Dewey was married, with a number of children. When Dewey was widowed in the mid-1920s, both he and Anzia had long moved on.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Sketch of Anzia accompanying a 1920s interview

. . . . . . . . . .