Nava Atlas's Blog, page 53

July 6, 2020

Monday or Tuesday by Virginia Woolf — a 1921 short story (full text)

“Monday or Tuesday,” a 1921 short story by Virginia Woolf, appeared in the only collection of stories she published during her lifetime. The title of the collection was also Monday or Tuesday. It was later anthologized in A Haunted House and Other Short Stories (1944), which contained six of the eight original stories.

First published by Hogarth Press, the small publishing company run by Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Mr. Woolf deemed it the worst book ever printed due to a plethora of typographical errors. They were corrected in later editions.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Virginia Woolf

. . . . . . . . .

Here are a duo of excellent analyses of this very short, very perplexing story:

A Short Analysis of Virginia Woolf’s Monday or Tuesday begins helpfully: If you found reading ‘Monday or Tuesday’ a disorienting experience, don’t worry: you’re meant to. One of the things Woolf is exploring through this short story is disorientation, distraction, the difficult and perhaps foolish quest for truthful and honest representation of the world through one’s writing. Even the title hints at this confusion and uncertainty: to the narrator, and perhaps to Woolf herself, today could be either Monday or Tuesday.

ENotes has a helpful critical analysis as well: In “Monday or Tuesday,” a series of contrasts between up and down, spatially free timelessness (a lazily flying heron) and restrictive timeliness (a clock striking), day and night, inside and outside, present experience and later recollection of it conveys the ordinary cycle of life suggested by the title and helps capture its experiential reality, the concern expressed by the refrain question that closes the second, fourth, and fifth paragraphs: “and truth?”

. . . . . . . . .

A Haunted House and Other Short Stories by Virginia Woolf on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . . .

A Foreword by Leonard Woolf

The original stories in Monday or Tuesday were later collected in A Haunted House and Other Short Stories. Monday or Tuesday was included along with the several other original stories: “A Haunted House,” “An Unwritten Novel,” “The String Quartet,” “Kew Gardens,” and “The Mark on the Wall.”

Mr. Woolf, as he explains here, omitted two of the original stories, “Blue & Green,” and “A society,” as he felt that would have been Virginia’s preference. Here is the Foreword by Leonard Woolf introducing this volume, which was published in the early 1944, after Virginia’s death.

Monday or Tuesday, the only book of short stories by Virginia Woolf which appeared in her lifetime, was published in 1921. It has been out of print for years.

All through her life, Virginia Woolf used at intervals to write short stories. It was her custom, whenever an idea for one occurred to her, to sketch it out in a very rough form and then to put it away in a drawer. Later, if an editor asked her for a short story, and she felt in the mood to write one (which was not frequent), she would take a sketch out of her drawer and rewrite it, sometimes a great many times.

Or if she felt, as she often did, while writing a novel that she required to rest her mind by working at something else for a time, she would either write a critical essay or work upon one of her sketches for short stories. For some time before her death we had often discussed the possibility of her republishing Monday or Tuesday, or publishing a new volume of collected short stories.

Finally, in 1940, she decided that she would get together a new volume of such stories and include in it most of the stories which had appeared originally in Monday or Tuesday, as well as some published subsequently in magazines and some unpublished. Our idea was that she should produce a volume of critical essays in 1941 and the volume of stories in 1942.

In the present volume I have tried to carry out her intention. I have included in it six out of the eight stories or sketches which originally appeared in Monday or Tuesday. The two omitted by me are “A Society,” and “Blue and Green.” I know that she had decided not to include the first and I am practically certain that she would not have included the second.

Monday or Tuesday by Virginia Woolf

Lazy and indifferent, shaking space easily from his wings, knowing his way, the heron passes over the church beneath the sky. White and distant, absorbed in itself, endlessly the sky covers and uncovers, moves and remains. A lake? Blot the shores of it out! A mountain? Oh, perfect—the sun gold on its slopes. Down that falls. Ferns then, or white feathers, for ever and ever——

Desiring truth, awaiting it, laboriously distilling a few words, for ever desiring—(a cry starts to the left, another to the right. Wheels strike divergently.

Omnibuses conglomerate in conflict)—for ever desiring—(the clock asseverates with twelve distinct strokes that it is midday; light sheds gold scales; children swarm)—for ever desiring truth. Red is the dome; coins hang on the trees; smoke trails from the chimneys; bark, shout, cry “Iron for sale”—and truth?

Radiating to a point men’s feet and women’s feet, black or gold-encrusted—(This foggy weather—Sugar? No, thank you—The commonwealth of the future)—the firelight darting and making the room red, save for the black figures and their bright eyes, while outside a van discharges, Miss Thingummy drinks tea at her desk, and plate-glass preserves fur coats——

Flaunted, leaf—light, drifting at corners, blown across the wheels, silver-splashed, home or not home, gathered, scattered, squandered in separate scales, swept up, down, torn, sunk, assembled—and truth?

Now to recollect by the fireside on the white square of marble. From ivory depths words rising shed their blackness, blossom and penetrate. Fallen the book; in the flame, in the smoke, in the momentary sparks—or now voyaging, the marble square pendant, minarets beneath and the Indian seas, while space rushes blue and stars glint—truth? content with closeness? Lazy and indifferent the heron returns; the sky veils her stars; then bares them.

More about Monday or Tuesday by Virginia Woolf

Listen online at Librivox

Monday or Tuesday at the British Library

Read the entire collection of Monday or Tuesday on Project Gutenberg

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Monday or Tuesday by Virginia Woolf — a 1921 short story (full text) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 2, 2020

Elizabeth Taylor’s Novels: Where to Begin, Which to Reread?

English author (not the actress) Elizabeth Taylor (1912 – 1975) published seventeen books: four collections of stories, one children’s book, and twelve novels. If you’re just discovering this under-appreciated author and wondering where to begin or considering a reread, here is a glimpse of Elizabeth Taylor’s novels.

She’s “not like most novelists,” Elizabeth Jane Howard observes; she’s “one in a thousand: how deeply I envy any reader coming to her for the first time.”

In Contemporary Novelists, Elizabeth explained her process: “I write in scenes, rather than in narrative, which I find boring. I am pleased if the look of a page is interesting, broken by paragraphs or dialogue, not just one dense slab of print.”

. . . . . . . .

Learn more about Elizabeth Taylor

. . . . . . . . . .

At Mrs Lippincote’s (1945)

It was Mr Lippincote’s house too, but Elizabeth Taylor is keenly interested in women’s lives. Here we have the Davenant family—Roddy and Julia, with their son, Oliver—moving into this house with “every comfort,” near the RAF base where Roddy works.

With them is Eleanor, Roddy’s cousin and an unmarried school-teacher, who tries “not to behave like a spinster in a book.” Julia, unsatisfied with married life and with conversations “about butchers and laundries” with other wives, prefers to discuss the Brontës with the Wing Commander.

Paragraphs of dialogue outnumber expository passages, and the novel is a pleasure to read but poses a bolder question: what can this intelligent and ambitious woman expect from this world, beyond a Mrs Davenant’s house?

. . . . . . . . . .

Palladian (1946)

Cassandra arrives at Cropthorne Manor to be a governess, but she has “nothing to recommend her to such a profession,” beyond a “proper willingness to fall in love, the more despairingly the better with her employer.”

Bookish readers will relate to Cassandra’s struggle to reconcile her bookish expectations with her reality. Taylor’s Palladian, compared to her body of work, is like Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey to Austen’s better-known novels, all-of-a-piece but with a sharpness and witty, peculiar darkness.

. . . . . . . . . .

A View of the Harbour (1947)

Just as artwork plays a key role in Palladian, the central character in Taylor’s third novel is a painter. Bertram Hemingway is a retired naval officer, who anticipates hours spent painting the Newby harbor. It should make a “fine picture,” and indeed, Bertram’s narrative showcases the author’s appreciation of light and color.

But even more absorbing are the layers of relationships in this fishing community, where “everyone looks out for—and in on—each other.”

Her longest work yet, The View of the Harbour shifts perspectives between residents. Each character is developed meticulously and engagingly (though they’re not always likeable) and readers feel both intimately involved and isolated, as do many villagers.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Wreath of Roses (1949)

This could have been an idyllic novel about three women vacationing in summer, but something happens when Camilla is traveling to meet her friend Liz (at Frances’ house, Frances having been Liz’s governess).

A tragedy at the railway station situates Camilla’s holiday in an unsettled state, but Taylor’s humor soothes the sinister elements.

One might say that the book is about the little things, like a hot summer in an English town, the elements of everyday that inspire Frances’ paintings: “But not little. That is life. Its loving kindness and simplicity, and it lay there all the time in [her] pictures, implicit in every petal and every jug [she] ever painted.”

. . . . . . . . . .

A Game of Hide and Seek (1951)

When they were children, Harriet and Vesey entertained the younger children with hide-and-seek, always hiding together, in the hayloft. To have hidden independently would have seemed a betrayal: they committed to each other in the simplest terms. All of the children in Taylor’s fiction are remarkably credible.

When they are separated while Vesey attends Oxford, Harriet takes a position in a gown shop to distract herself from his absence; perhaps in search of a more permanent distraction, she marries another man.

When Harriet and Vesey reconnect—accidentally and enthusiastically—in middle-age, dynamics shift. This is quintessential Taylor territory: commitment and compromise, disappointment and desire, what we hide and what we seek.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Sleeping Beauty (1953)

In her introduction to Virago’s 1983 reprint of Taylor’s sixth novel, Susannah Clapp extolls the author’s “careful and unreverent documentation of middle-class life.”

Taylor, Clapp says, writes about “people who are comfortably off and who feel uncomfortable.” Isabella is the epitome of uncomfortable, when Vinny arrives to comfort her, in the wake of her husband’s death.

When Vinny meets Emily, this new relationship takes precedence: Clapp writes that “he is within a smile of being a cad.” Isabelle occupies her time with Evalie and something-like-normal resumes, so their talk “skimmed along, chocolates were chosen from the box, tea drunk, sherry sipped.”

Grief plays a role, but more important is what Clapp describes as the “daily piling-up of small losses or small lies.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Angel (1957)

A particular delight for readers with an interest in writing and publishing, Angelica Deverell is a prolific and successful romance writer. Inspired by two biographies about popular English novelist Marie Corelli (one by Eileen Bigland published in 1953 and the other by Amanda McKittrick Ros published in 1954), Taylor considers the relationship between invention and desperation.

The worlds that Angelica Deverell’s characters inhabit are lush and extravagant; in one way, the world she inhabits as authoress is also like that, but, in another, her world is barren and lonely.

What and how we create, how we retreat into fantasy, the dreams we harbor about romance: Angel could be viewed as a cautionary tale, but Taylor’s characterization of Angelica makes it more complicated than that. Film buffs take note: Angel was filmed in 2007, directed by François Ozon and starring Romola Garai.

. . . . . . . . . .

In a Summer Season (1961)

Kate’s second marriage is to a man ten years her junior; also occupying the Herons’ home are the children from her first marriage (her twenty-two-year-old son and sixteen-year-old daughter), an elderly aunt, and a cook.

Relationships revolving around each household member are of interest, but at the core of the novel is the triangle between Kate and Dermot and Charles—an old family friend whose arrival (with his daughter) disrupts the family home.

Taylor’s eye for detail and ear for dialogue make easy reading of dysfunctional family life: “In the summer, white jasmine made the dark flint walls less gloomy.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Soul of Kindness (1964)

In contrast to Angel, Taylor’s ninth novel focuses on several characters once more; in that sense, it’s more like A View of the Harbour, but with fewer shifts. At the core of the story is the Secretan mother-and-daughter pair, and the novel opens with the daughter’s wedding.

Flora and Richard recall other married couples in Taylor’s fiction, including her debut, whose expectations and reality collide also. But here the focus is on how people build and break key relationships, not only marriages.

One member of the cast who stands out is Miss Folley, the housekeeper (who brings to mind Mrs Parsons, Frances’ charlady in A Wreath of Roses, and Mrs Curzon, Harriet’s hired help in A Game of Hide and Seek).

How we maintain our homes, small comforts and small ceremonies: The Soul of Kindness is rich with character and the thematic reverberations reward a close reading.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Wedding Group (1968)

The charwoman in this novel is the “only sign of life” in the communal “world of women” that Cressy inhabits. One of the women there tells Cressy that she has “a wicked little head on those young shoulders” and Cressy hears the echo of her mother’s disapproval there too.

When she ultimately leaves the commune and works in an antique shop, Cressy appears to move toward independence. When she meets and marries David, whose relationship with his mother is tedious and demanding, Cressy trades her fledgling independence for another form of dependence.

Fascinating for its portrayal of power and its complex shifts in agency, this is one of Taylor’s most uncomfortable novels.

. . . . . . . . . .

Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont (1971)

A suitable companion for Cressy’s story, with its theme of independence, this novel features Laura Palfrey as she is taking up residence with other elderly women (and a single man) at the Hotel Claremont. In the dining room, the other residents “look as if they had been sitting there for years” as they anticipate their celery soup.

In this scene, Mrs Palfrey appears to fit outwardly. But readers know that she does not, and soon the evidence—in the form of a handsome, young writer named Ludo—is clear to other residents too.

Delicately and deliberately constructed, this portrait of aging is invigorating and deservedly lauded. This novel has also been a BBC Book at Bedtime, and a film, directed by Dan Ireland in 2005—from a screenplay by Ruth Sacks Caplin written for television in the 1970s—and starring Joan Plowright.

. . . . . . . . . .

Blaming (1976)

Written and edited after Taylor’s cancer diagnosis and treatment, it’s unsurprising that this slim novel deals with grief. At the forefront, however, is a complicated friendship that erupts and develops after Anne’s husband dies on holiday.

Martha’s assistance is useful in the immediate aftermath, but the women struggle to maintain a connection after Anne returns to England. Questions of responsibility and disassociation, guilt and denial, feature prominently in the novel.

And despite its heavy themes, Taylor’s use of dialogue (particularly with the children) and her astute social observations make this posthumously published novel a rewarding read.

On the back of the 1995 edition of A View of the Harbour, this blurb appears from Anne Tyler: “Jane Austen, Elizabeth Taylor, Barbara Pym, Elizabeth Bowen—soul sisters all.” If you’re looking for a soul sister to add to your bookshelves, look no further.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

More about Elizabeth Taylor on this site

Quotes by British Novelist Elizabeth Taylor

Quotes from Elizabeth Taylor’s Fiction: Glimpsing the British Novelist’s Gifts

. . . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Taylor page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Elizabeth Taylor’s Novels: Where to Begin, Which to Reread? appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 1, 2020

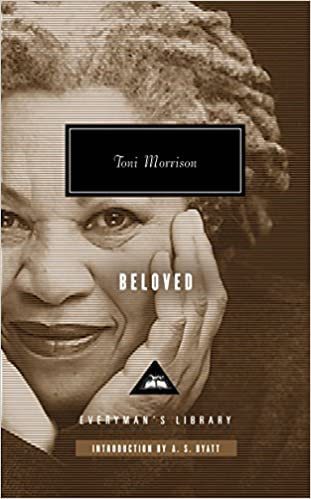

Powerful Quotes from Beloved by Toni Morrison (1987)

Toni Morrison (1931 – 2019), the American novelist, editor, essayist, teacher, and professor is remembered for her powerful novels exploring the African-American experience. Following are quotes from Beloved, her Pulitzer Prize-winning 1987 novel.

Morrison based Beloved on a true incident. In 1856, a female escaped slave crossed the Ohio river from Kentucky into Ohio to seek freedom. Instead, she was captured, and killed her child so she wouldn’t have to be returned to slavery. Similarly, Sethe, the protagonist of the novel, kills her baby, who she calls Beloved, and is ever after haunted by her ghost.

Beloved earned Morrison a Pulitzer Prize, and later won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1993 to honor her body of published works. These included The Bluest Eye (1970), Sula (1974), Song of Solomon (1977) and Tar Baby (1981). Morrison went on to publish many other works of fiction and nonfiction. From the publisher:

“Sethe was born a slave and escaped to Ohio, but eighteen years later she is still not free. She has too many memories of Sweet Home, the beautiful farm where so many hideous things happened. And Sethe’s new home is haunted by the ghost of her baby, who died nameless and whose tombstone is engraved with a single word: Beloved. Filled with bitter poetry and suspense as taut as a rope, Beloved is a towering achievement.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Toni Morrison

. . . . . . . . .

“Freeing yourself was one thing, claiming ownership of that freed self was another.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Sweet, crazy conversations full of half sentences, daydreams and misunderstandings more thrilling than understanding could ever be.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Definitions belong to the definers, not the defined.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There is a loneliness that can be rocked. Arms crossed, knees drawn up, holding, holding on, this motion, unlike a ship’s, smooths and contains the rocker. It’s an inside kind–wrapped tight like skin. Then there is the loneliness that roams. No rocking can hold it down. It is alive. On its own. A dry and spreading thing that makes the sound of one’s own feet going seem to come from a far-off place.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Me and you, we got more yesterday than anybody. We need some kind of tomorrow.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Something that is loved is never lost.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Let me tell you something. A man ain’t a goddamn ax. Chopping, hacking, busting every goddamn minute of the day. Things get to him. Things he can’t chop down because they’re inside.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“Love is or it ain’t. Thin love ain’t love at all.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“No matter what all your teeth and wet fingers anticipated, there was no accounting for the way that simple joy could shake you.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“In Ohio seasons are theatrical. Each one enters like a prima donna, convinced its performance is the reason the world has people in it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I don’t care what she is. Grown don’t mean a thing to a mother. A child is a child. They get bigger, older, but grown? What’s that supposed to mean? In my heart it don’t mean a thing.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Sifting daylight dissolves the memory, turns it into dust motes floating in light.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Lay my head on the railroad line. Train come along; pacify my mind. ”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Unless carefree, mother love was a killer.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Sad as it was that she did not know where her children were buried or what they looked like if alive, fact was she knew more about them than she knew about herself, having never had the map to discover what she was like.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The best thing she was, was her children.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She did not tell them to clean up their lives, or go and sin no more. She did not tell them they were the blessed of the earth, its inheriting meek, or its glory-bound pure. She told them that the only grace they could have is the grace they could imagine. That if they could not see it, they could not have it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“No more running-from nothing. I will never run from another thing on this Earth. I took one journey and I paid for the ticket, but let me tell you something, Paul D. Garner: it cost too much!”

. . . . . . . . . .

Beloved by Toni Morrison on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

“People who die bad don’t stay in the ground.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It’s not about choosing somebody over her. It’s about making space for somebody along with her.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Outside, snow solidified itself into graceful forms. The peace of winter stars seemed permanent.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“What’s fair ain’t necessarily right.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Beloved, she my daughter. She mine. See. She come back to me of her own free will and I don’t have to explain a thing.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Nothing could be counted on in a world where even when you were a solution you were a problem.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Feel how it feels to have a bed to sleep in and somebody there not worrying you to death about what you got to do each day to deserve it. Feel how that feels. And if that don’t get it, feel how it feels to be a colored woman roaming the roads with anything God made liable to jump on you. Feel that.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“In trying to make the slave experience intimate, I hoped the sense of things being both under control and out of control would be persuasive throughout; that the order and quietude of every day life would be violently disrupted by the chaos of the needy dead; that the herculean effort to forget would be threatened by memory desperate to stay alive. To render enslavement as a personal experience, language must first get out of the way.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It was lovely. Not to be stared at, not seen, but being pulled into view by the interested, uncritical eyes of the other.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“More it hurt more better it is. Can’t nothing heal without pain, you know.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It was the right thing to do, but she had no right to do it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Daily life took as much as she had. The future was sunset; the past something to leave behind. And if it didn’t stay behind, well, you might have to stomp it out.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“You just can’t mishandle creatures and expect success.”

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Powerful Quotes from Beloved by Toni Morrison (1987) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 30, 2020

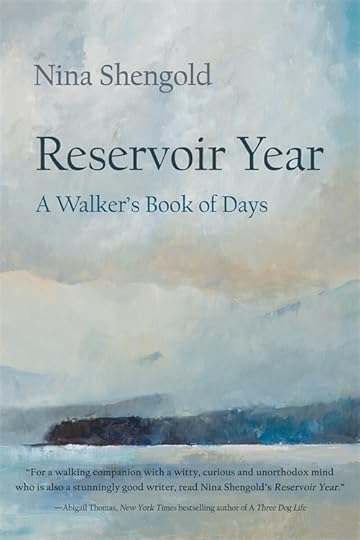

Reservoir Year: A Walker’s Book of Days by Nina Shengold

Nina Shengold’s Reservoir Year: A Walker’s Book of Days (Syracuse University Press, 2020) takes its place in the tradition of deeply felt nature writing, the kind that heightens observation of the world while delving into questions of self.

Literary Ladies Guide rarely features books that aren’t by classic (that is, departed) women authors or directly related to them (fictional homages, biographies, etc.). But when I opened Reservoir Year (Syracuse University Press, 2020), I at once imagined it as a descendant of the works of several classic authors whose profound affinity to the natural world became central to their art:

For Emily Brontë, any sojourn away from her Yorkshire home of Northern England, no matter how brief — to attend school or work as a governess — would make her ill. As a veritable recluse, Emily thrived on great long walks on the moors surrounding the Brontë family home, her devoted dog Keeper at her side. It was the only way she could exist in the world.

Tragically, Emily succumbed to consumption (tuberculosis) at age 30, but not before producing her iconic novel, Wuthering Heights (1847), and a body of poetry considered some of the finest in the English language. Here’s a lovely essay on nature in the poetry of Emily Brontë, which affirms that “the image of Emily Brontë roaming the moors is one mythic element about her that is true.”

Mary Hunter Austin is no longer widely read, but in her time, she moved though vaunted American literary circles. Her first and best-known book, The Land of Little Rain (1903), was a loosely connected collection of short stories and essays paying tribute to the lands of American Southwest and its Native American inhabitants, as well as its animal and plant life.

In her essays and stories, Austin offers vivid descriptions of mountains, deserts, trails, and even weather phenomena. Her writings highlight the benefits of harmony between humans and nature, or the dire consequences of its opposite. Keenly observing the natural world in writing confirmed her life’s purpose — fighting for environmental and social justice, especially for the native people who so revered the land.

Gene Stratton-Porter was a hugely successful author in her time, as well as a self-taught naturalist. In A Girl of the Limberlost (1909), her best-known novel, teenaged Elnora Comstock is far more interested in moths than in men. Her rambles through the Limberlost swamp, lovingly detailed, lead to her becoming a teacher of natural history and a collector of scientific specimens — both unusual practices for women of the time.

Stratton-Porter was often called the “bird lady” in her Indiana home town thanks to her intricate, detailed, and passionate writings about the state’s natural habitats. Better yet, she wove not-so-subtle messages of female independence into her enjoyable tales.

A more contemporary cousin to Reservoir Year is Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, a 1974 memoir by Annie Dillard. Dillard records observations of her corner of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains through a year of journalistic entries, using them as a springboard for contemplations on life itself.

. . . . . . . . . .

Illustration by Carol Zaloom

. . . . . . . . . .

Nina Shengold arranges Reservoir Year by season and begins at a metaphorical place many of us come to in life: A crossroads. That’s what makes Reservoir Year so lovely and relatable. I can fully understand why Shengold set herself a seemingly impossible challenge as she came to what felt like a turning point in life. This upstate New Yorker begins with the book’s preamble:

I live in the foothills of the Catskills, four miles from the glorious Ashokan Reservoir. For a year, I walked by its side every day, in all kinds of weather, from predawn to starlight.

My usual path is a former roadbed on top of the reservoir’s main dam. There’s a small parking lot near the village of Olivebridge rimmed by wildflowers, hardwoods, and pines. You pass through a row of traffic barrier columns and take a few strides to the edge of the trees, and the world opens up: a panoramic vista of water, mountains, and sky. People stop in their tracks and gasp. I once heard an awestruck child cry out, “Is that the ocean? Mom! What is this place??”

It’s a good question. I spent a year trying to answer it, day after day after day. I was poised to turn sixty, a birthday that can’t help but rattle the ribcage. My daughter Maya was at college in Vermont and I missed her bright energy daily; my parents were dwindling into their nineties. And my dog had died.

Reservoir Year’s publisher, Syracuse University Press, introduces the book:

On the eve of her sixtieth birthday, Nina Shengold embarks on a challenge: to walk the path surrounding the Catskills’ glorious Ashokan Reservoir every day for a year, at all times of day and in all kinds of weather, trying to find something new every time. Armed with lively curiosity, infectious enthusiasm, and renewed stubbornness, she hits the path every day with all five senses wide open, searching for details that glint.

As Shengold explores the secrets of this spectacular place, she rediscovers the glories of solitude and an expanded community, both human and animal. Step by step, her reservoir walks rekindle connections with family, strangers, and friends, with a landscape she grows to revere, and with a new sense of self.

Like the writings of John Burroughs, Annie Dillard, and Barry Lopez, Shengold’s reflections on her personal journey will resonate with outdoor enthusiasts and armchair hikers alike. Quietly transformative, Reservoir Year encourages readers to find their own ways to unplug and slow down, reconnecting with nature, reviving old passions, and sparking some new ones along the path.

How will this yearlong journey to walk and observe the same path each day transform Nina Shengold? That is for the reader to discover. In troubled times, or simply when one is at a proverbial fork in the road, a personal challenge can reignite a passion for life.

Reservoir Year is a comforting yet thought-provoking meditation on the human relationship with the natural world and how a connection with nature can deepen our awareness and empathy, no matter where we are in life.

Illustrated with beautiful hand-colored linocuts by Carol Zaloom and line drawings by Will Lytle. Cover art by Kate McGloughlin.

. . . . . . . .

Reservoir Year: A Walker’s Book of Days by Nina Shengold

is available on Amazon* and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . . .

About the author

Nina Shengold’s books include the novel Clearcut (Anchor Books), River of Words: Portraits of Hudson Valley Writers (SUNY Press, with photographer Jennifer May), and fourteen theatre anthologies for Vintage Books and Viking Penguin, many coedited with Eric Lane. She won the Writers Guild Award for her teleplay Labor of Love and the ABC Playwright Award for Homesteaders. Her plays are published by Playscripts, Broadway Play Publishing, and Samuel French; War at Home: Students Respond to 9/11, written with Nicole Quinn and the Rondout Valley High School Drama Club, has been produced around the world. Shengold has profiled more than 150 writers for Chronogram, Poets & Writers, and Vassar Quarterly. She’s a founding member of the theatre company Actors & Writers, author series Word Café, and Hudson Valley Writers Resist. A graduate of Wesleyan University, Shengold has taught at Manhattanville College and the University of Maine, and currently teaches creative writing at Vassar College. She was born in Brooklyn, grew up in New Jersey, escaped to Alaska, and now lives and works in the foothills of New York’s Catskill Mountains.

Praise for Reservoir Year: A Walker’s Book of Days

“Shengold’s beautifully calibrated rhythm of language conveys all the rhythm of walking—the quiet, graceful stride along with lively, animated steps, the contemplative solitary strolls and those shared with companions. But she offers us as well the rhythm of the infinitesimal and the grand; of the expected and the unexpected; of the abstract and the real.”

—Akiko Busch, author of How to Disappear: Notes on Invisibility in a Time of Transparency

“To walk with Shengold along the banks of the Ashokan Reservoir is to see the Catskills—its ever-changing sky, its magnificent wildlife, and even its ghosts—through the lens of a writer of rare and exquisite sensibility.”

—Leslie T. Sharpe, author of The Quarry Fox: And Other Critters of the Wild Catskills

“Accompanied by her elegant, unpretentious prose, the reader comes upon surprises: a bear, an eagle feather, a crimson forest. Filled to the brim with subtle revelations, of sunwashed illuminations but also the poignant history; a drowned town lies below the shimmering surface. Expect to be moved, and then overcome by the tenderness and variety of Shengold’s emotional literary palette.”

—Laura Shaine Cunningham, author of Sleeping Arrangements and A Place in the Country

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Reservoir Year: A Walker’s Book of Days by Nina Shengold appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 26, 2020

Quotes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s impactful novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), was the first ever to be an international best-seller. More than 1.5 million copies of the anti-slavery novel were sold worldwide during its first year of release in 1852. Following is a selection of quotes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which isn’t always considered great literature, but is credited for helping to turn public opinion against slavery.

The novel helped fuel the anti-slavery movement, and is thought to have changed the course of history as well the publication business. No other book sold as many copies in the 19th century, other than the Bible.

Stowe’s astounding success with novel affected the fight for the abolition of slavery and displayed her fearlessness by writing on this subject in a white-dominated world.

Ever modest, Stowe barely took credit for her work. “I did not write it. God wrote it. I merely did his dictation,” she wrote in the introduction to the 1879 edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Further, she explained in the Author’s Preface:

“The object of these sketches is to awaken sympathy and feeling for the African race, as they exist among us; to show their wrongs and sorrows, under a system so necessarily cruel and unjust as to defeat and do away the good effects of all that can be attempted for them, by their best friends, under it.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

How Harriet Beecher Stowe was Inspired to Write Uncle Tom’s Cabin

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Any mind that is capable of real sorrow is capable of good.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“The longest way must have its close — the gloomiest night will wear on to a morning.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“…the heart has no tears to give, — it drops only blood, bleeding itself away in silence.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Scenes of blood and cruelty are shocking to our ear and heart. What man has nerve to do, man has not nerve to hear.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“There are in this world blessed souls, whose sorrows all spring up into joys for others; whose earthly hopes, laid in the grave with many tears, are the seed from which spring healing flowers and balm for the desolate and the distressed.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Death! Strange that there should be such a word, and such a thing, and we ever forget it; that one should be living, warm and beautiful, full of hopes, desires and wants, one day, and the next be gone, utterly gone, and forever!”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Treat ’em like dogs, and you’ll have dogs’ works and dogs’ actions. Treat ’em like men, and you’ll have men’s works.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“I am braver than I was because I have lost all; and he who has nothing to lose can afford all risks.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

“So much has been said and sung of beautiful young girls, why don’t somebody wake up to the beauty of old women?”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Perhaps it is impossible for a person who does no good not to do harm.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Talk of the abuses of slavery! Humbug! The thing itself is the essence of all abuse!”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“I make no manner of doubt that you threw a very diamond of truth at me, though you see it hit me so directly in the face that it wasn’t exactly appreciated, at first.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“No one is so thoroughly superstitious as the godless man.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Could I ever have loved you, had I not known you better than you know yourself?”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“All men are free and equal, in the grave,”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“It is with the oppressed, enslaved, African race that I cast in my lot; and if I wished anything, I would wish myself two shades darker, rather than one lighter.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Everything your money can buy, given with a cold, averted face, is not worth one honest tear shed in real sympathy?”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“My country again! Mr. Wilson, you have a country; but what country have I, or anyone like me, born of slave mothers? What laws are there for us? We don’t make them,—we don’t consent to them,—we have nothing to do with them; all they do for us is to crush us, and keep us down.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Sir, 1 haven’t any country, any more than I have any father. But I’m going to have one. I don’t want anything of your country, except to let me alone—to go peaceably out of it; and when I get to Canada, where the laws will own me and protect me, that shall be my country, and its laws I will obey. But if any man tries to stop me, let him take care, for I am desperate. I’ll fight for my liberty to the last breath I breathe. You say your fathers did it; if it was right for them, it is right for me!”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Deeds of heroism are wrought here more than those of romance, when, defying torture, and braving death itself, the fugitive voluntarily threads his way back to the terrors and perils of that dark land, that he may bring out his sister, or mother, or wife.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Harriet Beecher Stowe

. . . . . . . . . .

“Every nation that carries in its bosom great and unredressed injustice has in it the elements of this last convulsion.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“I’ve lost everything in this world, and it’s clean gone, forever– and now I can’t lose heaven, too; no, I can’t get to be wicked, besides all.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“What poor, mean trash this whole business of human virtue is! A mere matter, for the most part, of latitude and longitude, and geographical position, acting with natural temperament. The greater part is nothing but an accident.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“When a heavy weight presses the soul to the lowest level at which endurance is possible, there is an instant and desperate effort of every physical and moral nerve to throw off the weight; and hence the heaviest anguish often precedes a return tide of joy and courage.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“There have been times when I have thought, if the whole country would sink, and hide all this injustice and misery from the light, I would willingly sink with it.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“in a novel, people’s hearts break, and they die, and that is the end of it; and in a story this is very convenient. But in real life we do not die when all that makes life bright dies to us.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“We ought to be free to meet and mingle, –to rise by our individual worth, without any consideration of caste or color; and they who deny us this right are false to their own professed principals of human equality.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe

Wikipedia

The First Great American Novel

The Pervading Influence of Uncle Tom’s Cabin on Pop Culture

Listen to a free audio recording on Librivox

The post Quotes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 22, 2020

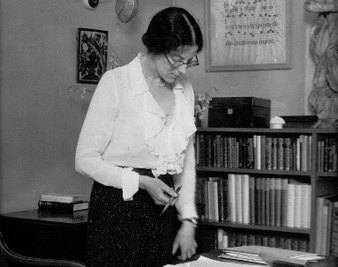

Sylvia Townsend Warner

Sylvia Townsend Warner (December 6, 1893 – May 1, 1978) was an English novelist, poet, and musicologist. Best known for her novels Lolly Willowes and The Corner That Held Them, she was also a prolific writer of short stories and contributed to The New Yorker for over forty years.

Despite a revival of her work in the 1970s, led by feminist publisher Virago Press, she is still an under-appreciated figure in literature and is probably just as well known for her long-term lesbian relationship with Valentine Ackland.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Early years

Sylvia was the only child of Harrow schoolmaster George Townsend Warner and his wife, Nora Mary Hudleston. She was a strong-willed and curious child, who loved learning but was withdrawn from kindergarten after a single term.

According to her school report, she distracted the other children with too many questions and mimicked the teachers to the point of insolence. The only positive comment was that she was a musical child who always sang in tune.

After this, Sylvia was taught at home by Nora. The Bible, history, geography, Shakespeare, languages, and music were all taught with flair, alongside vivid stories from Nora’s own childhood in India.

Her father instilled in Sylvia the same passion for history that he himself had. A talented teacher, he was beloved by his pupils and by Sylvia, who adored him though his teaching and housemaster responsibilities often kept him too busy for family.

Sylvia’s relationship with her mother was more difficult and complex. Nora’s affection for her daughter tailed off as Sylvia grew into a tall, lanky, shortsighted girl who showed no interest in any of the social necessities and niceties that Nora herself held so dear.

When, in 1911, Sylvia was of an age to “come out” in society, she drove Nora to distraction by showing very little interest in the proceedings. Later, Sylvia would write that “nothing compensated for my sex,” and felt that Nora resented her for not being a boy.

Generally, though, Sylvia’s upbringing was a comfortable one. Term times at Harrow were interspersed with family holidays, to Switzerland during the winter and to Scotland in the summer. Early in 1914, George bought a piece of land in South Devon intending to build a house for holidays and eventual retirement.

The house, known as Little Zeal, became a permanent home for George and Nora but never for Sylvia. Her relationship with her mother was strained enough: by 1914 she was more than ready to start making her own way.

Outbreak of war and dedication to music

Music had always been important to Sylvia. She was a talented pianist and composer, and when she was 16 began to study formally with the music master at Harrow, Percy Buck. He supported and encouraged her, teaching her the piano and the organ, the history and theory of music, and composition. He was also her first real lover; they began an affair when Sylvia was 19. which lasted for 17 years.

At the outbreak of war in 1914, Sylvia had been due to travel to Europe to study composition with Arnold Schoenberg. Instead, she stayed in England, continuing to study under Buck’s tutelage and the supervision of the Royal College of Music.

She also worked the night shift at a munitions factory in South London. Her father encouraged her to write about her experiences there, and the result was an 8,000-word essay, ‘Behind the Firing Line’, which was published under the name of “A Lady Worker” in Blackwood’s in February 1916. It was Sylvia’s first published piece.

In September of that year, George died, likely from a burst ulcer. His death affected Sylvia badly: she would later write, “My father died when I was twenty-two, and I was mutilated.”

Moving back to Little Zeal to take care of her mother was an ordeal. Their relationship had not improved, and grief made it worse for both of them.

In 1917 she was offered, possibly through Buck’s intervention, a position as editor for a new musicology project: the collecting, editing, and publication of a wealth of Elizabethan church music, which until then had existed only in handwritten form in cathedral books.

The Tudor Church Music project, financed by the Carnegie (UK) Trust, gave her a salary of £3 per week, which was not much to live on but gave her enough to move back to London and away from Nora. Sylvia enjoyed the work and threw herself into it, gaining a reputation as a talented editor who knew her subject.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Life in London and the first novel

Sylvia settled quickly into a relatively quiet life in London. Although she knew many of the people who would become part of the Bloomsbury set, she preferred fewer friendships to large gatherings, and her affair with Percy Buck continued.

Her relationship with her mother also began to improve after Ronald Eiloart, a former pupil of her father’s and a close friend of the family, returned from the war and asked for Nora’s hand in marriage. Sylvia was delighted and the Eiloarts appalled, but the match seemed to suit Nora and so relieved Sylvia of some worry and stress.

Writing was also becoming a large part of Sylvia’s life, taking the place of composing. She was beginning to write poetry, using left-over pieces of the smooth, heavy manuscript paper that she brought home with her from the Carnegie project.

She also attempted a novel, The Quick and the Dead, which was quickly discarded in favor of a new story about a contemporary witch. This novel, which became Lolly Willowes, was far easier for Sylvia to write: “One line led me to another, one smooth page to the next.”

Sylvia was also corresponding with the writer, philosopher, and Dorset recluse Theodore Powys, and her determination to find a publisher for his work brought her into contact with both David Garnett of Nonesuch Press and with Chatto & Windus.

It was Garnett who, in 1923, encouraged her to send her poems for publication, and Chatto that accepted them. The collection was published as The Espalier, followed by Lolly Willowes in 1926.

Both met with great success and Sylvia handled the inevitable questions about black magic and witchcraft with humor and candor, suggesting that modern-day witches might use vacuum cleaners instead of broomsticks for flying.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Dorset and Valentine Ackland

After finishing her second novel, Mr. Fortune’s Maggot, Sylvia’s next project was ambitious: a study of Theodore Powys. She never completed it and only seventy-six drafted pages survive, but the project took her to Dorset and to the village of Chaldon where Powys lived.

There, one summer evening, she met a Mrs. Molly Turpin, also known as Valentine Ackland. Valentine had been renting a cottage in the village since 1925 as an escape from her unhappy marriage to Richard Turpin, and often visited the Powys’s.

This first encounter was not a success. Sylvia felt overawed by Valentine’s poise and beauty (she was almost six feet tall, elegant with a boyish haircut and slim figure) and felt as if she, the “famous novelist,” was a disappointment. She compensated by being dismissive and rude, and Valentine subsequently avoided her in the village.

In October 1927, Sylvia began writing the diary that she would keep for the next fifty years. It shows the busyness and diversity of her London life — often meeting friends (although still avoiding parties), attending concerts and recitals, continuing with her work at the Carnegie project, and publishing her second collection of poetry, Time Importuned, in spring 1928.

By 1929, however, the affair with Buck was fading. Sylvia was beginning to feel old and dowdy: her face annoyed her (“what was wrong with my face was that the orders had been mixed”), and her hair displeased her (“like Disraeli in middle-age, so oily and curly”).

She was also having trouble writing. Her latest novel, Early One Morning, went unfinished and was followed by several false starts. The Tudor Church Music project was wound up, with the final trustees meeting taking place in October. The only thing that she found gave her joy was poetry.

Amid emotion with Buck and worry over Powys’s son Francis, who was said to have consumption, Sylvia traveled down to Dorset in spring 1930. This time she purchased a cottage and, after meeting Valentine again and realizing that she had nowhere of her own in the village, offered her the option of sharing.

The idea was that both women would use the cottage for a month or so at a time, separate and apart, in between London commitments. By the end of the year, however, they had become lovers. Sylvia ended the affair with Buck and left London for Chaldon.

The honeymoon years

Sylvia wrote of those first months, “…life rising up again in me cajoles with unscrupulous power and I will yield to it gladly, if it leads me away from this death I have sat so snugly in for so long…”

Deeply in love, as the months went by their lives “joined up imperceptibly, along all their lengths”. Their worst row was over the housekeeping: Sylvia was accustomed to thrift and to having to be ingenious, whereas Valentine viewed such behavior as unnecessarily alarming and demeaning.

Music, too, was a source of difference, and the concerts and recitals that had been so much a part of Sylvia’s life became rare occurrences. She preferred not to go without Valentine, and Valentine preferred not to go. They both accepted these differences, which gave a little breathing space and privacy between them.

Happy though they were, Valentine was not entirely at ease and often had moments of depression and private drinking — an ongoing problem of which Sylvia remained unaware.

The differences in their writing also caused Valentine some distress. Her reverence for poetry matched her love for Sylvia, and she found her inability to write during the first flush of their relationship a real problem. Sylvia had originally viewed Valentine’s poetry as “pleasing minor verse.”

Now, as Valentine’s lover, she came to see it as superior to her own: lyrical, difficult, with layers that deepened the more she read. However, she also recognized that the short, flowing form would not sell.

Knowing that her own work would be published but that Valentine’s would struggle, Sylvia came up with a plan of sending out their poems together for publication in a single volume, with only their initials on the title page. Valentine agreed, somewhat dubiously. The collection was later published as Whether a Dove or a Seagull, with their full names on the title page of the American edition but no attribution to individual poems. In the English edition, however, a key was included in the back to say who had written what.

Reviews were mixed, with most reviewers becoming too caught up in trying to guess who each poem belonged to rather than to actually review the poems themselves. Valentine was embarrassed and upset.

The shift to Communism and the Spanish Civil War

In the winter of 1933, Valentine began to read political pamphlets. Most of them focused on atrocities in Nazi Germany and the colonial situation in Africa and troubled her enormously, but she was wary of the left-wing alternatives.

By 1934, however, the scale of Nazi brutality in Germany had changed her mind, and even Sylvia — who previously had been generally uninterested in politics — was persuaded that the Communist cause was a just one.

In the spring of 1935, they both became members of the Communist Party of Great Britain, and Communism became almost like a blessing on their relationship, which they had come to think of as marriage.

By 1936, the emerging situation in Spain appalled both of them, and Valentine longed to join the miliciana, the female Republican fighters. This never happened, but in September both she and Sylvia were “called up” to work in a Red Cross unit in Barcelona. Their work there only lasted three weeks, but it was enough for Sylvia to develop a passion for Spain that matched her passion for politics.

Through it all, she continued to write. In January 1936 she finished her novel Summer Will Show, and in the spring she also submitted the first of 150 short stories to The New Yorker. After having made a bet that it would be rejected, she had to forfeit her £5. On the whole, though, it was a good bargain; the regular income that followed was to make her financially secure for the rest of her life.

A dangerous affair: Elizabeth Wade White

During 1937 Sylvia became a whirlwind of activity for the Party, undertaking several public speaking engagements. The flurry was in part due to the lingering enthusiasm from Spain, but also as a distraction from one of Valentine’s affairs.

Sylvia always remained faithful to Valentine, but Valentine often had “dalliances” which Sylvia did not mind; indeed, she encouraged them, not wanting Valentine’s desire for her to be tainted by longing for others.

She was always convinced of their love for each other and told Valentine as much, noting that if ever a woman came along who caused Sylvia damage, then her feelings would be very different. Until 1938, she never had cause to test those feelings.

Elizabeth Wade White was a young, rich American who Sylvia had met in 1929 on a short trip to New York. Also a Communist, in 1938 she was on her way to Spain and, after getting back in touch with Sylvia, stayed in Dorset for a few days en route. The worsening situation in Spain made it impossible for her to get there, and she turned back to Paris. Sylvia and Valentine offered her a place to stay, and by November of that year, Valentine and Elizabeth were lovers.

By February 1939, Sylvia was sufficiently unhappy that she considered moving out of the shared house. Valentine begged her to stay, but a joint trip to America for a Writer’s Congress was a disaster. Elizabeth, tagging along, was unwilling to share Valentine and became increasingly possessive and jealous.

Sylvia attempted to conceal how hurt and upset she was, while Valentine was torn between the two of them. After a difficult summer, the news of war made Valentine’s mind up for her. She returned to England with Sylvia, but things remained strained.

Both Sylvia and Valentine volunteered with the local branch of the Women’s Voluntary Service during the war, while Valentine also took on extra clerking duties.

Sylvia continued to write, publishing a volume of short stories in America, But the war years were difficult for both of them, and in 1944 Valentine fell into an almost suicidal depression. She felt she could not write, was worried about money, and felt guilty over their relationship, which had never really recovered from the disastrous trip to America.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

After the war, and another affair

Sylvia continued to write throughout the war, publishing The Cat’s Cradle Book in America and beginning work on a new novel The Corner That Held Them. Both she and Valentine volunteered in the Women’s Voluntary Service. Valentine hated the rigidity of the roles she was given, and by 1944 had fallen into a suicidal depression.

After the war, their lives continued to diverge. Sylvia had more success with her writing, signing a lucrative First Reading Agreement with the New Yorker, finishing The Corner That Held Them, contributing articles to magazines such as The New Statesman and The Countryman, and accepting a commission to write a book about Somerset.

Valentine, meanwhile, was experiencing the private transformation of spirituality and religion, something which Sylvia did not understand or easily accept.

In April 1949, this new preoccupation with God was interrupted when Elizabeth Wade White came to visit again. This time both Valentine and Sylvia realized that Elizabeth would not simply “blow over” and Valentine found herself torn once more.

She was genuinely in love with two people at the same time, but her eventual solution pleased nobody: in an echo of their arrangement before the war, she proposed that they should all three live together, Valentine and Elizabeth as lovers and Sylvia as a companion.

Sylvia, horrified, rejected this idea completely, and began to think of the practicalities of moving out. She continued to live with Valentine while Elizabeth returned to America to make preparations for moving, but, as she said in a letter to her friend Alyse Gregory, “the attrition of waiting is as dangerous as a wound that may turn to gangrene.”

Elizabeth’s arrival date was set for September 2, 1949, for one month. During this time, Sylvia would live in a hotel rather than find another place to live permanently. But while Sylvia found life in the hotel dreary and dull, Valentine struggled to adjust to living with Elizabeth and missed Sylvia desperately.

By spring 1950, when Elizabeth had returned to America, the affair — which had been so much more than an affair — was over, but Valentine and Sylvia’s relationship never fully recovered.

. . . . . . . . .

Sylvia Townsend Warner page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

The last years

The mood of the 1950s was uncertain, with the threat of another war looming. Both Sylvia and Valentine continued to support Communism, but with far less zeal than before. In 1953 Valentine formally resigned from the Communist Party and turned to Roman Catholicism.

Sylvia did not share Valentine’s enthusiasm for religion. Their conversation around the church was wary at best, and in private Sylvia found that flippancy was the best way for her to deal with the situation.

The church at Weymouth attended by Valentine became “Our Lady of Winkles,” the prayer sheets “Holy Crumbs,” the devotional candles by Valentine’s bed “blue nightlights”. But the gap opening between her and Valentine disturbed Sylvia a great deal.

She even felt herself to blame, writing to a friend that, “she would not, she could not, have turned back into that church if loneliness, unhappiness, sense of frustration, disappointment, disillusionment, had not driven her.”

Sylvia focused instead on taking joy from other things — the garden, her cats, her writing, the time she spent with Valentine where the Church was not a topic of conversation, music.

In 1954 her latest novel, The Flint Anchor, was published with rave reviews, and later that year she was offered the chance to translate Proust’s Contre Sainte-Beuve. This was published in 1958 to great critical acclaim and was followed in 1964 by a biography of the novelist T. H. White (published in 1967).

However, Valentine was suffering from serious health problems. During the 1960s she underwent an operation for temporal arteritis and then treatment for breast cancer. After two operations and radiotherapy, it was found that the cancer had spread to her lungs. She died, with Sylvia at her bedside, on November 9, 1969.

In the months afterward, everyday life ceased to have much meaning for Sylvia. Her writing slowed down, and although she kept up correspondences with friends, she felt that nothing could fill the gap Valentine left. Some joy in life was only restored when, in 1972, she befriended the young widow of an Austrian count, Gräfin Antonia Trauttmansdorff.

What started as a superficial social acquaintance grew to a deep friendship that sustained Sylvia through her last years. It was during this time that she wrote Elfindom, saying that her new friendship allowed her to leave behind the intricacies of the human heart and write something entirely different.

Soon Sylvia’s health began to deteriorate due to old age. Having always been strong and robust, she began falling, and by the beginning of 1978 could not walk more than a few steps without support. She died, at home, at the beginning of May, surrounded by the blooming flowers in her garden.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is an author, poet and artist with a serious case of wanderlust. She is originally from the UK, but has spent time abroad in Europe, the United States and the Bahamas.

When not traveling or working on her current projects — a chapbook of poetry, “The Cabinet of Lost Things,” and a novel based on the life of modernist writer and illustrator Djuna Barnes — she can be found with her nose in a book, daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Visit her on the web at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Sylvia Townsend Warner

Major works

Novels

Lolly Willowes (1926)

Mr Fortune’s Maggot (1927)

The True Heart (1929)

Summer Will Show (1936)

After the Death of Don Juan (1938)

The Corner That Held Them (1948)

The Flint Anchor (1954)

The Music at Long Verney: Twenty Stories (2001; posthumous)

Poetry collections

The Espalier (1925)

Time Importuned (1928)

Opus 7 (1931)

Whether a Dove or Seagull (1933; jointly written with Valentine Ackland)

Boxwood (1957)

Collected Poems (1982)

More information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Sylvia Townsend Warner Society

Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes is ‘a great shout of life’

Colm Toibin Reads Sylvia Townsend Warner

Sylvia Townsend Warner Reading Week 2020

Biographies and letters

Sylvia Townsend Warner: A Biography by Claire Harman (1989)

I’ll Stand By You: Selected Letters of Sylvia Townsend Warner and Valentine Ackland, edited by Susanna Pinney (1998)

This Narrow Place: Sylvia Townsend Warner and Valentine Ackland 1930-1951, by Wendy Mulford (1988)

The Akeing Heart: Letters Between Sylvia Townsend Warner, Valentine Ackland and Elizabeth Wade White, edited by Peter Haring Judd (Handheld Press, 2018)

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Sylvia Townsend Warner appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 20, 2020

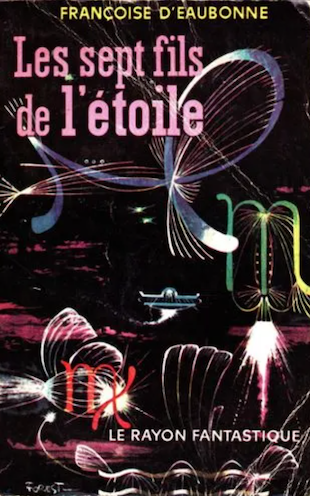

Discovering Françoise d’Eaubonne, Pioneering Ecofeminist

At the age of eleven, Françoise d’Eaubonne (March 12, 1920 – August 3, 2005) wrote on a convent wall, “Vive le féminisme!”

This was just the start of what would be a radical life as a member of the French Communist Party, writing more than fifty novels and essays and, most importantly, coining her defining theory: ecofeminism.

One of the best-known leaders of the French feminist movement, d’Eaubonne’s most famous work was her essay “Le Féminisme ou Le Mort” (Feminism or Death), published in 1974.

Up until last year, I had never heard the name Françoise d’Eaubonne. Perusing the various muddled titles in a French second-hand book market I happened upon a book with a rather interesting cover, and still more interesting blurb:

“Pour la première fois peut-être dans l’histoire de la science-fiction, le héros: le pilote de l’astronef, est une femme!”

Using my rather amateurish French, I translate: “for perhaps the first time in the history of science fiction, the hero, the pilot of the spacecraft is a woman!” I was intrigued. Why have I never heard of this? If I am to believe the blurb, isn’t this revolutionary?

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Les Sept Fils de l’Etoile

Three euros poorer, clutching Les Sept Fils de l’Étoile, written in 1962 by the mysterious Françoise d’Eaubonne, I was on the quest to discover this forgotten heroine. A barely existent Wikipedia page, most of her books to be found on no site, let alone an English-language one, I felt in possession of a secret treasure: I had to turn to discovering her through the book itself.

Reading the first few pages, it is not hard to see that d’Eaubonne was ahead of her time, her work seething with feminist and colonialist criticism (phrases such as “it’s rare for a woman to get to my job level” and “a result of earthly racism”), but in a foreign landscape: space. D’Eaubonne seemed to be especially concerned with the environment.

Ecofeminism as seminal theory

From there I could finally find information on this enigma. Later branded “apolitical and ahistorical,” ecofeminism was d’Eaubonne’s seminal theory. She asserted that the patriarchy views both women and nature as wild and unruly, and that in a utopian world, there would be equality under the harmony of nature, with all organic functions respected.

A contemporary and friend of Simone de Beauvoir, d’Eaubonne wrote to her in a letter: “nous sommes toutes vengées.” This means “we are all avenged.” She is right; it is therefore time for d’Eaubonne to have a resurgence.

Contributed by Beatrice Ricketts.

. . . . . . . . . .

Françoise d’Eaubonne page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Françoise d’Eaubonne and ecofeminism

Britannica’s article on ecofeminism

Françoise d’Eaubonne, pionnière de l’écoféminisme

Françoise d’Eaubonne et l’Ecoféminisme by Caroline Goldblum

Selected works – Fiction

Le cœur de Watteau, 1944

Comme un vol de gerfauts, prix des lecteurs 1947

Belle Humeur ou la Véridique Histoire de Mandrin,1957

J’irai cracher sur vos tombes, 1959

Les Tricheurs,

Jusqu’à la gauche, 1963

Les Bergères de l’Apocalypse, 1978

On vous appelait terroristes, 1979

Je ne suis pas née pour mourir, 1982

Terrorist’s blues, 1987

Floralies du désert, 1995

Selected essays

“Le complexe de Diane, érotisme ou féminisme” 1951

Y a-t-il encore des hommes? 1964

Eros minoritaire, 1970

Le féminisme ou la mort, 1974

Les femmes avant le patriarcat, 1976

Contre violence ou résistance à l’état, 1978

Écologie, féminisme : révolution ou mutation ?, 1978

La liseuse et la lyre, 1997

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Discovering Françoise d’Eaubonne, Pioneering Ecofeminist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 15, 2020

11 Essential Classic Novels and Memoirs by Black Women Authors

Literary Ladies Guide celebrates classic women authors, and as part of our mission, we honor the rich tradition of African-American women authors. If you’d like to read more classic novels and memoirs by Black women writers, there’s much to explore. This list is a good place to start.

Historically, it was challenge enough for women to become published authors; this was especially true for African-American women facing the dual struggle of race and gender bias. Fortunately, there are more women of all backgrounds writing today. That’s why this site limits its scope to women who have passed on, and those are the authors you’ll find in this list.

From the slave narratives of the 19th century, to the identity-seeking stories of the Harlem Renaissance, to the unique voices of recently departed authors like Toni Morrison and Ntozake Shange, these foundational classics have stood the test of time, and are still incredibly good reads.

. . . . . . . . . .

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Ann Jacobs (1861)

In 1857, Harriet Ann Jacobs (1813 –1897) was completing a manuscript for a barely fictionalized account of her life as a slave, and of her struggle to free herself and her children. After all she’d been through and how compellingly she presented her narrative, though, not a single publisher was willing to take the book on.

After repeated rejections, Harriet decided to publish the book herself, an impressive feat for any woman of that era, let alone one that had spent years as a fugitive slave. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself, an autobiography that reads like a novel, was published in 1861.

More about Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Ann Jacobs.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Plum Bun by Jessie Redmon Fauset (1928)

Jessie Redmon Fauset (1882 – 1961) was an American editor, poet, essayist, and novelist associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Plum Bun, the second of her four novels, was an important addition to the small but persistent canon of “passing” novels of the era produced by both male and female authors.

Plum Bun: A Novel Without a Moral is the story of Angela Murray, a young mixed-race woman who moves to New York City after her parents’ death. Angela decides to try to live as a white woman, only to discover that life on the other side of what was then called “the color line” also had its share of pitfalls. Creativity ultimately becomes the greatest source of satisfaction for her.

More about Plum Bun by Jessie Redmon Fauset.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Passing by Nella Larsen (1929)

Passing by Nella Larsen (1891 – 1964) is one of the most iconic novels of the Harlem Renaissance era of the 1920s. Within its spare prose lies deep ideas and much to ponder. The 2001 Griot Edition describes it succinctly:

“Passing’ is not only a direct reference to Clare’s decision to live as a white woman but also the suppression of her sexuality. It also calls attention to the other kinds of ‘passing’ women do in relationships romantic and otherwise, and the adoption by the black middle class of the actions and values of the dominant culture.”

More about Passing by Nella Larsen.

. . . . . . . . .

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston (1937)

Zora Neale Hurston made a name for herself during the Harlem Renaissance as an author and ethnographer. Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), her third published book and second novel, is certainly her best-known work and something of a feminist classic.

Janie, the story’s heroine, searches for independence, identity, love, and happiness over the course of twenty-five years and several relationships. This story is actually not unlike Zora’s own, though it could be argued that she never found true happiness.

Here’s more about Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Street by Ann Petry (1946)

The Street by Ann Petry was published in 1946 and became the first novel by an African-American woman to sell more than a million copies — all told, it sold more than 1.5 million. The story centers on Lutie Johnson, a young black single mother coping with racism, sexual harassment, violence, and class divisions in World War II-era New York City.

In Ann Petry (1996), a concise biography and analysis of the author’s literary canon, Hilary Holladay observed: “The urban black characters’ suffering is especially acute once they come to believe that there is no better life ahead, that the American dream of success is not theirs to strive for, let alone achieve.”

Here’s more about The Street by Ann Petry.

. . . . . . . . . .

Jubilee by Margaret Walker (1966)

Jubilee by Margaret Walker (1966), the only novel by this esteemed American author, poet, and educator, was the culmination of some twenty-five years of research and writing.

The story of Vyry, a mixed-race slave, is based on the real-life experiences of Walker’s great-grandmother. Walker received the Houghton Mifflin Literary Fellowship for this book, and its completion served as her Ph.D. from the University of Iowa.

Covering the antebellum years, Civil War, and Reconstruction periods, the narrative moves from a Georgia plantation to Alabama, following Vyry’s life and loves.

Here’s more about Jubilee by Margaret Walker.

. . . . . . . . . . .

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou (1969)

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou (1928–2014) is a 1969 autobiography by the beloved writer and poet covering her upbringing and youth. The book is the first in a seven-volume series. It delves into Angelou’s journey, one in which she experiences and overcomes racism and trauma and develops the strength of character and a love of literature.

The book starts with her as a three-year-old being sent to Stamos, Arkansas, to live with their grandmother along with her older brother. By the end of the book, Angelou is sixteen years old and becomes a mother.

More about I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison (1970)

So many of Toni Morrison’s novels have entered the American canon as classics, perhaps none more so than Beloved (1987). But for those just starting to read Nobel laureate Toni Morrison, I think it’s best to work your way up to Beloved to fully appreciate the way she constructs and tells a story. And what place to better start than with her first novel, The Bluest Eye.

Centering on Pecola, a Black girl who dreams of having blue eyes to fit into Western standards of beauty, the book is a meditation on race, class, and gender. At first, the book didn’t sell well at first and received mixed reviews. But it made its way onto the book lists of black studies college courses, which helped boost its visibility. One of Morrison’s most accessible works, The Bluest Eye is a good way to ease into her brilliant oeuvre.

More about The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison.

. . . . . . . . . .

Kindred by Octavia E. Butler (1979)

For Octavia E. Butler, writing science fiction wasn’t merely a vehicle for escaping into fantasy, but a means to explore universal issues. This is certainly true of Kindred. Whereas most of Butler’s work, before and after this novel, fits squarely into the sci-fi realm, Kindred falls more into the category of speculative fiction.

It tells of a contemporary African-American woman who travels back in time to save an ancestor who happens to be a white slave owner. By saving him in his time, she ensures her own survival in the future. With her knowledge of what lies in the future, the choices Dana must make are often agonizing.

Here’s more about Kindred by Octavia E. Butler.

. . . . . . . . . .

Sassafrass, Cypress & Indigo by Ntozake Shange (1982)

Ntozake Shange (1948 –2018), best known for her staged “choreopoem” For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow is Enuf, was also the author of a number of novels. Sassafrass, Cypress & Indigo perfectly captures the author’s gift for weaving social observation with magical language to form a compelling story.

Sassafrass, Cypress & Indigo is the story of three sisters and their mother from Charleston, South Carolina, all of whom are striving to live their creative dreams. The New York Times wrote that “Shange’s rich and wondrous story of womanhood, art, and passionately-lived lives is written with such exquisite care and beauty that anybody can relate to her message.”

More about Sassafrass, Cypress & Indigo by Ntozake Shange.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Wedding by Dorothy West (1995)

Dorothy West (1907 – 1998) was the last surviving member of the Harlem Renaissance movement. In her early career, she became known for short stories. Her first novel, The Living is Easy, didn’t appear until 1948; then there was a gap of some forty-seven years until The Wedding, was published in 1995, when West was in her late 80s.

The novel centers on the wedding day of Shelby, the daughter of a prominent, affluent African-American (and mixed-race) family, and Meade, a white jazz musician. It takes place on Martha’s Vineyard, long an exclusive enclave of upper-middle-class Black families. From there, the story of five generations of an American family unfolds.

More about The Wedding by Dorothy West.

. . . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

Fascinating African-American Women Writers of the 19th Century

The post 11 Essential Classic Novels and Memoirs by Black Women Authors appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 14, 2020

Jubilee by Margaret Walker (1966)

Jubilee by Margaret Walker (1966), the only novel by this esteemed American author, poet, and educator, was the culmination of some twenty-five years of research and writing.

The story of Vyry, a mixed-race slave, is based on the real-life experiences of Walker’s great-grandmother. Walker received the Houghton Mifflin Literary Fellowship for this book, and its completion served as her Ph.D. from the University of Iowa.

Covering the antebellum years, Civil War, and Reconstruction periods, the narrative moves from a Georgia plantation to Alabama, following Vyry’s life and loves. Jubilee received praised for its realistic depictions of daily life in the time of slavery and its aftermath.