Nava Atlas's Blog, page 57

March 29, 2020

Optimistic Quotes from Pollyanna — and on Being “a Pollyanna”

A “Pollyanna,” according to Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary, is “a person characterized by irrepressible optimism and a tendency to find good in everything.” Following is a selection of quotes from Pollyanna — the 1913 novel by Eleanor H. Porter that gave rise to this enduring term.

You’ll also find some contemporary quotes on what it means to be — or not to be — “a Pollyanna.”

Pollyanna was first published in the World War I era — hardly the time, it would seem, for a book whose newly orphaned main character was as sunny and optimistic as they come. But somehow, the book struck a nerve and was an immediate hit with children as well as adults.

In a nutshell, Pollyanna is an 11-year-old orphan who comes to live under the care of her dour spinster aunt Polly in a Vermont town. Soon, her “glad game” — finding the good in any situation— wins over the residents of the town and transforms it into a place of hope and joy.

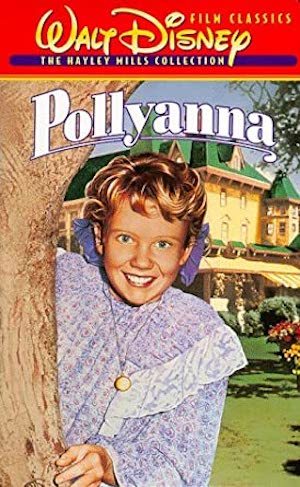

It didn’t take long for Pollyanna to sell a million copies. It was translated into numerous languages and adapted for stage, including a successful Broadway run. A number of film versions have appeared over the years, the best known of which was the 1960 Disney adaptation starring Hayley Mills in the title role.

Pollyanna is replete with literary clichés of the era — the exuberant orphan (think Anne of Green Gables and Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm) who wins everyone over; the stern spinster aunt whose heart softens; the downtrodden, kind servants. The writing is flat, sentimental, and often downright corny. Yet there’s something about Pollyanna’s optimism that’s been irresistible to generations of readers.

. . . . . . . . . .

Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter: Revisiting the Eternal Optimist:

. . . . . . . . . .

“There is something about everything that you can be glad about, if you keep hunting long enough to find it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I know, father-among-the-angels, I’m not playing the game one bit now—not one bit; but I don’t believe even you could find anything to be glad about sleeping all alone ‘way off up here in the dark—like this. If only I was near Nancy or Aunt Polly, or even a Ladies’ Aider, it would be easier!”

. . . . . . . . . .

“And most generally there is something about everything that you can be glad about, if you keep hunting long enough to find it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She had been too busy wishing things were different to find much time to enjoy things as they were.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Oh, but Aunt Polly, Aunt Polly, you haven’t left me any time at all just to — to live.”

“To live, child! What do you mean? As if you weren’t living all the time!”

“Oh, of course I’d be BREATHING all the time I was doing those things, Aunt Polly, but I wouldn’t be living. You breathe all the time you’re asleep, but you aren’t living. I mean living —doing the things you want to do: playing outdoors, reading (to myself, of course), climbing hills, talking to Mr. Tom in the garden, and Nancy, and finding out all about the houses and the people and everything everywhere all through the perfectly lovely streets I came through yesterday. That’s what I call living, Aunt Polly. Just breathing isn’t living!”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It’s funny how dogs and cats know the insides of folks better than other folks do, isn’t it?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“What men and women need is encouragement. Their natural resisting powers should be strengthened, not weakened…. Instead of always harping on a man’s faults, tell him of his virtues. Try to pull him out of his rut of bad habits. Hold up to him his better self, his REAL self that can dare and do and win out!”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The influence of a beautiful, helpful, hopeful character is contagious, and may revolutionize a whole town…. People radiate what is in their minds and in their hearts. If a man feels kindly and obliging, his neighbors will feel that way, too, before long. But if he scolds and scowls and criticizes—his neighbors will return scowl for scowl, and add interest!… When you look for the bad, expecting it, you will get it. When you know you will find the good—you will get that …”

. . . . . . . . . .

Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

“Oh, but your eyes are so big and dark, and your hair’s all dark, too, and curly,” cooed Pollyanna. “I love black curls. (That’s one of the things I’m going to have when I get to Heaven.) And you’ve got two little red spots in your cheeks. Why, Mrs. Snow, you ARE pretty! I should think you’d know it when you looked at yourself in the glass.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Well, you see, since I have been hurt, you’ve called me ‘dear’ lots of times—and you didn’t before. I love to be called ‘dear’—by folks that belong to you, I mean. Some of the Ladies’ Aiders did call me that; and of course that was pretty nice, but not so nice as if they had belonged to me, like you do. Oh, Aunt Polly, I’m so glad you belong to me!”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes on being “a Pollyanna”

“I have been accused of being a Pollyanna, but I think there are plenty of people dealing with the darker side of human nature, and if I am going to write about people who are kind and generous and loving and thoughtful, so what?” (Ann Patchett, author)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Balance in life is the key, as Aristotle taught us. Nobody likes a naive Pollyanna, but neither do we like to be around people who are constantly complaining and finding fault.” (Mark Skousen, economist)

. . . . . . . . . .

“My husband and I met on OK Cupid. We went out on our little coffee date, and I knew right away he was my husband. He’s a handsome, smarty-pants architect from Tokyo. On our first date, I said, ‘I wake up like this. I’m Pollyanna Sunshine, and I’m not for everyone’.” (Geneva Carr, actress)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Whenever someone calls me a Pollyanna, I consider it to be the highest of compliments. This courageous girl finds a community that has been torn apart with hate, fear, and pain and brings it love, courage and healing. Isn’t that what our world today needs more than anything?” (Joe Tye, author and inspirational speaker)

“I don’t mean to sound like a Pollyanna, but for me, New York is the ideal because of the diversity here. ‘Billy on the Street’ is really informed by that.” Billy Eichner, comedian

. . . . . . . . . .

“I am a bit of a Pollyanna — I spend most of my day happy.” (Ted Danson, actor)

. . . . . . . . . .

“I don’t find any real rivalries with crime and thriller writers anyway. That might sound a little Pollyanna, but for the most part the writers I compete with, if you want to use that word, it’s a pretty friendly rivalry. I think we all realize that the boat rises and sinks together.” (Harlan Coben, author)

. . . . . . . . . .

“In all probability the Human Genome Project will, someday, find that I carry some recessive gene for optimism, because despite all my best efforts I still can’t scrape together even a couple days of hopelessness. Future scientists will call it the Pollyanna Syndrome, and if forced to guess, I’d say that mine has been a way-long case history of chasing rainbows.” (Chuck Palahniuk, author)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Millions of Americans would still despair in the eight long years of the Depression that lay ahead and many of their individual dreams would be dashed on the rocks of economic hardship. But collectively, the country was in a new place, with a new confidence that the federal government would actively try to solve problems rather than fiddle or cater to the rich. Hope was no longer for Pollyannas; the cynics about the American system were in retreat.” (Jonathan Alter, journalist)

. . . . . . . . . .

“I prefer to see myself as the Janus, the two-faced god who is half Pollyanna and half Cassandra, warning of the future and perhaps living too much in the past — a combination of both.” (Ray Bradbury, author)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Be a balanced optimist. Nobody is suggesting that you become an oblivious Pollyanna, pretending that nothing bad can or ever will happen. Doing so can lead to poor decisions and invites people to take advantage of you. Instead, be a rational optimist who takes the good with the bad, in hopes of the good ultimately outweighing the bad, and with the understanding that being pessimistic about everything accomplishes nothing. Prepare for the worst but hope for the best — the former makes you sensible, and the latter makes you an optimist.” (Dale Carnegie, author and motivational speaker)

. . . . . . . . . .

The 1960 film adaptation starring Hayley Mills

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Pollyanna – 1960 film

Read Pollyanna online at Project Gutenberg

Listen to Pollyanna on Librivox

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Optimistic Quotes from Pollyanna — and on Being “a Pollyanna” appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 26, 2020

10 Classic Cuban Women Authors to Discover

Cuban literature began gaining the recognition it deserved at the start of the 19th century. Here we’ll take a look at ten inspirational Cuban women authors that deserve to be discovered and read.

Gertrudis Gomez de Avellaneda, the earliest of the writers listed here, focused on abolitionist characters. After the abolition of slavery in Cuba in 1886, the focus of Cuban literature shifted to themes of independence, freedom, social protest, and personal and universal issues.

Poetry was a widely practiced genre for Cuban women writers, although they produced many short stories, essays, novels, autobiographies, ethnographical studies, and testimonial literature.

Due to its rich history, Cuban literature is considered among the most influential in the Spanish-speaking world, and women have long been an intrinsic part of its development.

. . . . . . . . . .

Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda (1814 – 1873)

Born in Puerto Principe, Cuba, Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda was a Cuban-Spanish playwright considered one of the greatest of romantic writers and women poets of the 19th century.

Though she didn’t live in Cuba for much of her life, having spent much of it in Spain, she had a major influence on Cuban literature. Avellaneda’s timeless style, romantic vision, and personal suffering combined to create some of the most heart-rending literature in the Spanish language.

Based on historical models, Avellaneda’s plays are distinctive due to their poetic diction and lyrical passages. Her first poems, published under her nom de plume La Peregrina, were collected in 1841 and combined into a volume called Poesias Liricas (Lyrical Poems).

Though some of her works are now almost entirely forgotten, including the antislavery Sab (1841), others received major recognition and were met with success. Among those were Alfonso Munio (1844), based on the life of Alfonso X, and Saul (1849).

Years after the publication and success of these works, Avellaneda attempted to enroll in the Royal Academy in 1853 after her friend Juan Nicasio Gallego died, leaving a vacant seat. Though she was widely admired by male members of the academy, she was rejected by the Academy because she was a woman.

After being rejected from the Academy, Avellaneda briefly returned to Cuba before returning to Madrid, where she died in 1873.

. . . . . . . . .

Úrsula Cespedes (1832 – 1874)

Úrsula Céspedes was born in Hacienda La Soledad, close to Bayamo in the eastern part of Cuba. Céspedes was a poet and the founder of the Academia Santa Úrsula in Manzanillo, Cuba.

Her education started at home where she learned music and French. Years later while visiting Villa Clara, a province in Cuba, she met her soon-to-be husband, Gines Escanaverino.

Shortly after, she became a teacher and founded the Academia Santa Úrsula for women’s schooling with her husband. The couple moved to Havana in 1863 where they remained until 1865 when her husband became a director for a secondary school, where the poet also taught classes.

Céspedes’ first poems were published in 1855 in Semanario Cubano and El Redactor in Santiago de Cuba. In 1861, she published her first book, Ecos de la Selva, with a prologue by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes.

After the death of her brothers and father, Céspedes moved to Santa Isabel de las Lajas due to the uncontrolled persecution against her family. She died there on November 2, 1874. In 1948 the Dirección de Cultura of the Ministry of Education published a selection of her works.

. . . . . . . . . .

Aurelia Castillo de González (1842 – 1920)

Aurelia Castillo de González was born in Camagüey, Cuba. She received a liberal arts education, which inspired her interest in literature.

She married Spanish soldier Colonel Francisco Gonzalez del Hoyo, whose support of the Republic earned him many enemies in Cuba. As a result, in 1875 the couple left Cuba for Spain.

There, Aurelia worked for various magazines to establish her writing career, focusing on anti-slavery issues.

She first attracted attention as a writer with her elegy on “El Lugareno” in 1866. She was also the author of a volume of fables based on the life and works of Gertrudis Gomez de Avellaneda. In addition, she founded the Academia de Artes y Letras (Academy of Arts and Letters).

After much travel, she returned to her hometown of Camagüey where she died in 1920.

. . . . . . . . . .

Lydia Cabrera (1899 – 1991)

Lydia Cabrera, born in Havana, Cuba, was a writer as well as a literary activist, and ethnologist. She is known as a major figure in Cuban letters for her work in Afro-Cuban folklore and fictional works.

In 1927, Cabrera moved to France in hopes of becoming an artist. As a result of her studies in Paris and a friendship with Teresa de la Parra, a Venezuelan author whom she met while studying in Europe, she decided to study Afrocubanismo as an adult. The pair often studied Cuba and read Cuban books together.

In 1938, she returned to Cuba and remained there until 1960. After the Communist takeover by Fidel Castro, she relocated to Miami, Florida, where she lived and continued to work for the remainder of her life. Around the time of her death, she donated her research collection to the University of Miami.

Cabrera published over one hundred books, the most important being El Monte (The Wilderness), the first major ethnographic study of Afro-Cuban traditions, herbalism, and religion.

In addition, she was among the first writers to bring recognition to the rich Afro-Cuban culture and religion. She contributed greatly to Cuba’s literature, anthropology, art, ethnomusicology, and ethnology. Cabrera died in Miami, Florida, on September 19, 1991.

. . . . . . . . .

Ofelia Rodríguez Acosta (1902 – 1975)

Ofelia de la Concepción Rodríguez Acosta García was a writer, journalist, activist, and radical feminist born in Pinar del Rio, Cuba. In addition to being an author feminist chronicles, stories, novels, and essays, she’s also considered one of Cuba’s most famous social reformers.

Writing and study were greatly valued in her childhood, as her father was a writer and intellectual. Rodríguez was a bright student at the Institute of Havana, and as a result of her hard work she was awarded a grant to study in Europe and Mexico.

Rodríguez was recognized as one of the most prolific writers of the 1920s and 1930s. She played an active role in Cuba’s politics as well. Between 1929 to 1932, she wrote for Bohemia, where she “developed radical psychological challenges to the prescribed behavior of Cuban women.”

Rodríguez, along with Cuban feminist, journalist, and poet Mariblance Sabas Aloma, was among one of Cuba’s most influential feminist writers of the early part of the twentieth century.

Some of Rodríguez’s work was quite controversial. La Vida Manda (1927), which caused public outrage, was perhaps the most controversial of all her works. She was quite adamant about women’s liberation from the religious, social, and sexual structures of society; she encouraged women to take control of their own liberation.

Rodríguez moved to Mexico in 1939 and lived there until her death on June 28, 1975. There has been speculation that she spent her last years in a Mexican lunatic asylum, while others report that she passed away in a nursing home in Havana. ??

. . . . . . . . . .

Dulce Maria Loynaz (1902 – 1997)

Dulce Maria Loynaz, known as the “grande dame of Cuban letters,” was born in Havana City, Cuba, into an artistic and patriotic family. She was the daughter of General Enrique del Castillo (author of the lyrics of the march theme “El Himno Invasor”) and the sister of poet Enrique Loynaz Munoz.

Loynaz’ young adulthood was filled with adventure, as she was able to enjoy experiences only accessible to the privileged. She published numerous poems in this phase of her life, and graduated with a Doctorate of Civil Law at the University of Havana in 1927. She never formally practiced law.

In 1928, Loynaz started writing the novel Jardin and completed it in 1935. Feminism was flourishing in Cuba, and women’s rights were making waves in politics.

Loynaz was elected as a member of the Arts and Literature National Academy in 1951, the Cuban Academy of Language in 1959, and the Spanish Royal Academy of Language in 1968. She received many prizes and awards from various Cuban cultural institutions. Perhaps the most notable awards was the Miguel de Cervantes Prize in 1984, considered the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in Spanish literature.

She voluntarily stopped writing in Cuba in 1959 after the victory of the Revolution. She continued to gain recognition for her works, however, and was awarded the Cuban National Prize for Literature in 1987. Dulce Maria Loynaz died in 1997 and was buried in the Colon Cemetery, Havana.

. . . . . . . . . .

Dora Alonso (1910 – 2001)

Born in Maximo Gomez, Matanzas, Cuba, Dora Alonso was a journalist and writer who worked in both print and radio. Her works range from novels, short stories, poetry, children’s literature, and theatre.

After her first poem, Amor, appeared in the El Mundo newspaper, she began taking on diverse writing jobs, such as becoming a correspondent of the newspaper Prensa Libre (Free Press) and writing radio scripts.

One of her first short stories on social issues was awarded in 1936 by Bohemia, a literary magazine. In 1942, she started writing for a magazine called Lux, which showcased her first interviews with many political and public figures. These included the Chinese ambassador in Cuba and Pablo Neruda, the Chilean poet.

Alonso is the most translated and published Cuban author for children. Two of her novels, Tierra Brava and Soy el Batey have been adapted to film by Instituto Cubano de Radio y Televisión. Another one of her novels, Tierra Inerme, was given the highest recognition at II Spanish American Literary Contest at Casa de las Americas.

Dora Alonso, one of the most prolific of Cuban writers, passed away at the age of ninety on March 21, 2001.

. . . . . . . . . .

Rafaela Chacón Nardi (1926 – 2001)

Rafaela Chacón Nardi was a Cuban poet and educator born in Havana, Cuba.

After studying to become a teacher, she became a professor and taught at Escuela Normal para Maestros, Universidad de La Habana, and Universidad Las Villas. In 1948 she published Journey to the Dream, her first volume of poetry. The work was reprinted in 1957 and included a letter that Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral wrote praising Nardi’s poetry.

In 1971, Nardi founded the Grupo de Expresión Creadora as she had an interest in design and development of educational activities for disabled children.

She also facilitated children’s workshops in order to teach them about the work of José Martí and directed the Clubes de Promocion a la Lectura (Reading Promotion Clubs) for blind children. As a result of her dedication and hard work, she was awarded the Alejo Carpentier medal. Nardi died on March 11, 2001, in Havana, Cuba.

. . . . . . . . . .

Julieta Campos (1932 – 2007)

Julieta Campos was a Cuban-Mexican writer born in Havana, Cuba.

she was awarded the Premio Xavier Villaurrutia for her novel, Tiene Los Cabellos Rojizos y Se Llama Sabrina (1974). Four years after receiving the award for her outstanding work, she became the director for the Mexican chapter of the writer’s organization, PEN.

In addition to her literary endeavors, Campos served in López Obrador’s cabinet as the local Secretary of Tourism during the administration of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as Head of Government of the Federal District.

Campos died of cancer at the age of 75 in Mexico City on September 5, 2007.

. . . . . . . . . .

Excilia Saldaña (1946 – 1999)

Excilia Saldaña Molina was an Afro-Cuban juvenile literature writer, academic, and poet born in Havana, Cuba.

After graduating from Pedagogical Institute in Havana, she became a high school teacher. She also became one of the cultural figures who established El Caimán Barbudo (The Bearded Cayman) in 1966.

In 1967, she received an honorable mention from the jury of the Casa de las Americas Prize for her first book of poetry, Enlloro’, an unpublished manuscript. After leaving her teaching job in 1971, Saldaña became an editor at Editorial Casa de las Américas.

Saldaña was a professor of children’s literature at the Felize Varela Teaching Institute as well as at other universities. Her writing style incorporated elements of folklore and cultural traditions, as well as the exploration of women’s roles. Her work sheds light on issues of abandonment, incest, and sexual violence that Caribbean women face.

Saldaña was the recipient of numerous awards, including the 1979 National Ismaelillo Prize and the Rosa Blanca Prize (which she won three years in a row) from the National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba (UNEAC). Years later, UNEAC honored her again with the Nicolás Guilén Award for poetry.

Due to complications related to asthma, Saldaña died on July 20, 1999 in Havana.

More Cuban women authors worth a mention

Brígida Agüero y Agüero (1837 – 1866)

Mirta Aguirre (1912 – 1980)

Juana Borrero (1877 – 1896)

Domitila García Doménico de Coronado (1847 – 1938)

Maria Cristina Fragas (1856 – 1936)

Gilda Antonia Guillen (1959 – 2006)

Ada Maria Isasi-Diaz (1943 – 2012)

María Dámasa Jova Baró (1890 – 1940)

More about Cuban women authors

In Focus: “Cuban Art and Identity 1900-1950”

Women poets of Cuba: a selection of poems translated by Margaret Randall

. . . . . . . . . .

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

The post 10 Classic Cuban Women Authors to Discover appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

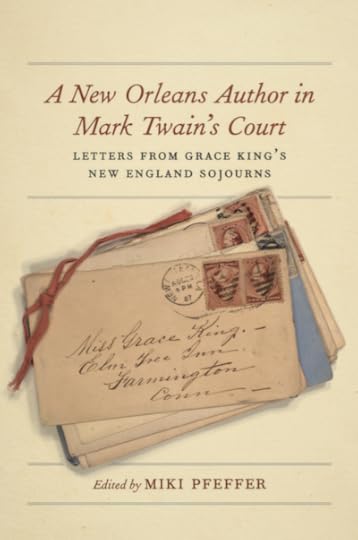

A New Orleans Author in Mark Twain’s Court : Letters from Grace King’s New England Sojourns

Grace King’s life (1852 – 1932) spanned two wars, various epidemics, disruptive politics, and fluctuating economics. Her literary career began in 1885 when two northern editors came to New Orleans to write up the south and find local writers at the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition.

Richard Watson Gilder of Century Magazine challenged King to write her first short story, and Charles Dudley Warner placed it and then mentored her into the publishing world.

Over almost five decades, King wrote short stories and novellas, biographies and histories, genealogy, and a memoir. Her path reflected the shifting changes in taste. As with other women writers whose works disappeared from the literary canon, she is again receiving attention for her sensitivity and knowledge of a particular time and place.

Her subjects were post-reconstruction New Orleanians, especially women, forced to reinvent themselves after a great loss for which they were ill prepared.

King’s father had been a successful attorney; she and six siblings were well educated in French Creole schools. At an impressionable ten years old when Union troops captured New Orleans, she and her family left the city until after the Civil War.

She never fully recovered from having expected a genteel life but inheriting a struggling one, especially after her father’s death in 1881. She and two sisters and a brother remained unmarried until their deaths.

Her determination to regain family status drove her literary career and genre choices. As a historian, researcher, genealogist, and independent businessperson, she was a woman before her time. As a writer of sensuous, ironic, and illuminating fiction, she fashioned stories that can reward readers who seek them out.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Grace King in 1887

Grace King in 1887

. . . . . . . . . . .

A New Orleans Author in Mark Twain’s Court

In A New Orleans Author in Mark Twain’s Court (LSU Press, November 2019), Grace King’s life is illuminated through her letters. Edited by Miki Pfeffer, A New Orleans Author in Mark Twain’s Court paints a fascinating picture of the northern literary personalities who caused King’s budding career to blossom.

Shortly after Grace King wrote her first stories in post-Reconstruction New Orleans, she entered a world of famous figures and literary giants greater than she could ever have imagined. Notable writers and publishers of the Northeast bolstered her career, and she began a decades-long friendship with Mark Twain and his family that was as unlikely as it was remarkable.

Beginning in 1887, King paid long visits to the homes of friends and associates in New England and benefited from their extended circles. She interacted with her mentor, Charles Dudley Warner; writers Harriet Beecher Stowe and William Dean Howells; painter Frederic E. Church; suffragist Isabella Beecher Hooker; Chaucer scholar Thomas Lounsbury; impresario Augustin Daly; actor Will Gillette; cleric Joseph Twichell; and other stars of the era.

As compelling as a novel, this audacious story of King’s northern ties unfolds in eloquent letters. They hint at the fictional themes that would end up in her own art; they trace her development from literary novice to sophisticated businesswoman who leverages her own independence and success.

Through excerpts from scores of new transcriptions, as well as contextualizing narrative and annotations, Miki Pfeffer weaves a cultural tapestry that includes King’s volatile southern family as it struggles to reclaim antebellum status and a Gilded Age northern community that ignores inevitable change.

King’s correspondence with the Clemens family reveals incomparable affection. As a regular guest in their household, she quickly distinguished “Mark,” the rowdy public persona, from “Mr. Clemens,” the loving husband of Livy and father of Susy, Clara, and Jean, all of whom King came to know intimately.

Their unguarded, casual revelations of heartbreaks and joys tell something more than the usual Twain lore, and they bring King into sharper focus. All of their existing letters are gathered here, many published for the first time.

Miki Pfeffer is a visiting scholar at Nicholls State University and the author of the award-winning Southern Ladies and Suffragists: Julia Ward Howe and Women’s Rights at the 1884 New Orleans World’s Fair.

. . . . . . . . . .

A New Orleans Author in Mark Twain’s Court on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

From the prologue of A New Orleans Author in Mark Twain’s Court

At the age of thirty-three, Grace King had little reason to expect to begin a literary career or to be welcomed into a circle of famous writers and respected publishers. In 1885, she was simply a disgruntled eldest sister with an urge for freedom but few prospects to achieve it, a relative drudge who spent her energies managing the house for an eccentric family and yearning to escape their incessant rebellions.

The center of the seven Kings was their mother, Mimi, whom Grace publicly called “a charming raconteuse, witty, and inexhaustible in speech” who “turned every episode of her life into a good and colorful story” but privately termed her “an ambitious woman, determined to surpass every one, & succeeding.”

Grace most often bemoaned her life en famille in uninhibited letters to her intime May, the only sister who escaped the erratic household when she married in early 1884 and moved to North Carolina. She labeled older brothers Fred and Branch unsympathetic, demanding, and disagreeable; and unmarried sisters Nan and Nina, lackadaisical and argumentative, “like unreliable watches, always running down or stopping and never giving the correct time of day.”

Nan she pictured as “utterly ignoring any social or domestic duties,” and Nina as “lying in bed with malaria — half the day — doing fancy work the other half.” Lastly, she saw her youngest brother, Will, as unrealistic and grandiose rather than responsible and contributing.

Exacerbating the turmoil, money was always scarce and penny-pinching was commonplace as the older brothers tried to provide for the genteel family, as expected (their father had died in 1881). Grace craved a life apart.

More about Grace King

Selected works

Monsieur Motte (1888)

Tales of a Time and Place (1892)

Balcony Stories (1893)

New Orleans: The Place and the People (1895)

Stories from Louisiana History (1905)

The Pleasant Ways of St. Médard (1916)

La Dame de Sainte Hermine (1924)

Memories of a Southern Woman of Letters (1932)

More information

Wikipedia

Grace King on Librivox

Reader discussion of King’s works on Goodreads

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post A New Orleans Author in Mark Twain’s Court : Letters from Grace King’s New England Sojourns appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 24, 2020

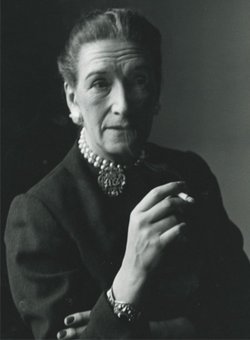

Elizabeth Bowen

Elizabeth Bowen (June 7, 1899 – February 22, 1973) was an Irish-British novelist and short-story writer best known for fictional works that focused on life in wartime London and relationships among the upper-middle class.

Some have referred to her as the “grande dame” of the modern novel, her work characterized by a conscious, concise style.

Bowen’s work reflects her great interest in “life with the lid on and what happens when the lid comes off.” It examines the innocence of orderly life and irrepressible forces that transforms one’s experience. In her stories and novels, she examines the betrayal and secrets beneath the veneer of respectability.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Early life and education

Elizabeth Dorothea Cole Bowen was born at 15 Herbert Place in Dublin to Florence Bowen and Henry Charles Cole Bowen. She was baptized in the nearby St. Stephen’s Church on Upper Mount Street and spent summers as a young girl at Bowen’s Court, a historic country house near Kildorrery, County Cork.

She lived in Ireland until the age of seven. After her father’s mental illness became acute in 1907, she and her mother relocated Hythe in England.

After her mother passed away in 1912, Bowen’s aunts became her guardians. They sent her to Downe House School, a selective girl’s boarding school, to receive an education. After attending art school in London, she decided to focus her attention on writing.

Bowen became associated with the Bloomsbury Group. She developed a good friendship with English writer Rose Macaulay, who assisted her in finding a publisher for her first book, Encounters (1923), a collection of short stories.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Love and literature

The same year that Bowen published Encounters (1923) she married Alan Cameron, an educational administrator. Their marriage was never consummated and was described as a “sexless but contented union.”

Although she was with Cameron, she had numerous relationships outside of her marriage. She was in a relationship with Charles Ritchie, a Canadian diplomat seven years her junior, for over thirty years. In addition, she had an affair with Irish writer Seán Ó Faoláin and American poet May Sarton.

Bowen and Cameron lived near Oxford where she regularly socialized with English scholar Maurice Bowra, Scottish novelist John Buchan, and British writer Susan Buchan.

The Last September (1929), one of her most notable works, discussed life in Danielstown, Cork at the time of the Irish War of Independence.

After the publication To the North (1932) was her next novel, Bowen and her husband moved to the Regent’s Park section of London. Here, she wrote The House in Paris (1935) and The Death of the Heart (1938). Between publishing these works, she became a member of the Irish Academy of Letters.

. . . . . . . . . .

Bowen’s Court

. . . . . . . . . .

Dealing with success

In 1930, Bowen inherited Bowen’s Court, becoming the first and only woman to do so. In the 1930s and onwards, Bowen had numerous notable visitors come to her home, including Virginia Woolf, Iris Murdoch, and Eudora Welty. On the eve of World War II, she began working for the British Ministry of Information in 1939 and reported on issues of neutrality and Irish opinion.

Bowen’s political views leaned towards Burkean conservatism during the wartime. During and after the war, Bowen arguably wrote one of the greatest expressions of what life was like in wartime London with novels such as The Demon Lover and Other Stories (1945).

For her contribution to literature, she was awarded the CBE (The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) in 1948.

In 1952, her husband retired and the couple settled in Bowen’s Court. He passed away a just a few months later. After his death, Bowen found it difficult to keep up with her household as she was constantly traveling to the United States to earn money by lecturing.

In 1958, Bowen traveled to Italy to research and prepare for her 1960 novel, A Time in Rome. A year later, she was forced to sell Bowen’s Court. After she sold her beloved home, it was demolished. Bowen spent the next few years without a stable home before she settled in Carbery, Church Hill, Hythe, in 1965.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Themes in Bowen’s work

Bowen explained that she preferred to write in the mornings when she was “cold, energetic, candid, and rational” as opposed to the evenings when her brain worked “fast but feverishly and with poorer quality.”

When she was working on a novel, she kept “office hours” strictly to standard business hours. She was slow and deliberate in her writing, and as a result, her novels were on the shorter side.

She highly admired the medium of film, and was influenced by filmmaking techniques that were popular in her time. Her most famous novel, The Heat of the Day (1948), is considered the best representation of London during the bombing raids of World War II.

In addition to her highly respected works on the realities of life, Bowen is also noted for her ghost stories. Robert Aickman, a supernatural fiction writer, describes Elizabeth Bowen as “the most distinguished living practitioner” of ghost stories.

. . . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Bowen page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Awards and honors; the legacy of Elizabeth Bowen

Elizabeth Bowen was awarded the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for her final novel, Eva Trout, or Changing Scenes (1968). In 1970, she was shortlisted for the Booker Prize for her work on Eva Trout (1968), her final novel about a young woman raised by her millionaire father.

In 1977, the first biography of Elizabeth Bowen was published by Victoria Glendinning. In 2009, Glendinning published a book focusing on the relationship between Charles Ritchie and Bowen based on letters and diaries.

In 2012, English Heritage marked Bowen’s Regent’s Park home at Clarence Terrace with a blue plaque. The plaque was unveiled on October 19, 2014 in commemoration of her residence at the Coach House, The Croft, Headington from 1925-1935.

Four of Bowen’s novels were adapted for British television of films: The Last September, The Death of the Heart, The Heat of the Day, and The House in Paris.

In a 2005 review of Elizabeth Bowen: The Enforced Return by Neil Corcoran, Stacey D’Erasmo summed up this writer’s legacy, noting that she was often compared to Virginia Wolfe and Henry James:

“Elizabeth Bowen is a great writer. To this sentence is usually appended a phrase like: ‘though widely underappreciated’ or ‘though not much read’ or ‘of the Anglo-Irish experience between the wars.’ These are the sorts of phrases that give the impression that Bowen must be read through a special instrument, such as a telescope.

In fact, the opposite is true. Bowen, the author of some twenty-eight books, who lived from 1899 to 1973, had a genius for conveying the reader straight into the most powerful and complex regions of the heart.

On that terrain, she was bold, empathic and merciless. She wrote about the aftermath of wars, about affairs and about childhood with equally piercing insight and a thorough comprehension of the consequences of politics and desire.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Final years

In 1972, Bowen spent Christmas with her friends in Kinsale, County Cork. Soon after returning home, she was hospitalized. She had developed lung cancer, and passed away in University College Hospital on February 22, 1973 at the age of seventy-three.

Elizabeth Bowen was buried alongside her husband in Farahy, County Cork churchyard, near Bowen’s Court’s gates. A commemoration of her life is celebrated annually at the entrance to St. Colman’s Church.

. . . . . . . . . .

More on Elizabeth Bowen

Major works (short stories)

Encounters (1923)

Ann Lee’s and Other Stories (1926)

Joining Charles and Other Stories (1929)

The Cat Jumps and Other Stories (1934)

Look At All Those Roses (1941)

The Demon Lover and Other Stories (1945)

Ivy Gripped the Steps and Other Stories (1946)

Stories by Elizabeth Bowen (1959)

A Day in the Dark and Other Stories (1965)

The Good Tiger (1965)

Elizabeth Bowen’s Irish Stories (1978)

The Collected Stories of Elizabeth Bowen (1980)

Novels

The Hotel (1927)

The Last September (1929)

Friends and Relations (1931)

To the North (1932)

The House in Paris (1935)

The Death of the Heart (1938)

The Heat of the Day (1949)

A World of Love (1955)

The Little Girls (1964)

Eva Trout (1968)

Biographies and critical studies

Elizabeth Bowen: A Biography by Victoria Glendinning (2006)

Love’s Civil War: Elizabeth Bowen and Charles Ritchie – Letters and Diaries 1941-1973, ed. by Victoria Glendinning with Judith Robertson (2009)

Elizabeth Bowen: A Literary Life by Patricia Laurence (2019)

In addition, there are numerous critical studies and critical essays on Bowen’s works.

More information and sources

Britannica

Oxford Bibliographies

Encyclopedia

Reader discussion of Bowen’s works on Goodreads

Collected Stories by Elizabeth Bowen — Ghosts, Comedy, and a Touch of Spark

Elizabeth Bowen archive at the Harry Ransome Center

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Elizabeth Bowen appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter: Revisiting the Eternal Optimist

Most everyone knows what defines a “Pollyanna” — someone who looks at the bright side of things no matter how dire, or who paints an overly optimistic picture of any situation. The 1913 novel Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter is perhaps less familiar now than the lasting expression that grew from its sentimental story.

Pollyanna, subtitled “The glad book,” was incredibly successful from the start, and inspired many adaptations in other media. Though intended as a children’s novel, it appealed to all ages.

Eleven-year-old Pollyanna Whittier, one of a legion of literary orphans, is sent to live with her aunt Polly, an icy spinster. This follows on the trope of another ebullient orphan of that era, Anne Shirley, better known as Anne of Green Gables (1908), who melts the heart of the stereotypical spinster who adopts her.

Introducing the “glad game”

Pollyanna and her departed father had devised a “glad game,” wherein they would try to find the silver lining in any situation, no matter how dire. So when Pollyanna got a pair of crutches for Christmas instead of the doll she longed for, she decided to be glad that she didn’t need the crutches.

Once she is living with her stern aunt, she is punished for being late for dinner and is relegated to eating bread and milk in the kitchen with the servant. No problem for her — she determines to enjoy the bread and milk and to like the servant.

In this essay, Jurrian Kamp muses on Pollyanna’s approach to life:

“The glad game shields her from her aunt’s stern attitude: when Aunt Polly puts her in an ugly attic room with no pictures, rugs or mirrors, she is glad for it.

If she had a nice bedroom, she probably wouldn’t notice the beautiful trees outside her window. Had her aunt given her a mirror, she would have to look at her freckles.”

Soon, Pollyanna is spreading her glad game to the resident of the dour Vermont town in which she now lives, transforming it into a joyous place to live.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

A comforting message on the eve of a world war

Sentimental, and occasional corny as the book can be, its comforting, positive message evidently resonated as the rumblings of World War I were being heard.

Indeed, the book was an instant bestseller. Newspapers reported that soon after its publication that the book sold more than 150,000 copies, and that the author, “Mrs. Eleanor H. Porter of Cambridge, Mass., is being overwhelmed with letters of appreciation and gratitude.”

Building on the enthusiasm for the original, Pollyanna Grows Up was published in 1915.

There are limits to optimism

More than a century after its publication, I still see this expression crop up surprisingly often, and it’s never a compliment. “Such a Pollyanna” is a critical response to someone who is unrealistically optimistic.

Jurrian Kamp argues that there are limits to optimism and that even Pollyanna, in the end, learned not to be so completely a blind optimist:

“Eventually, however, even Pollyanna’s robust optimism is put to the test when she is hit by a car and her legs become paralyzed. Her response, for once, seems realistic.

She is grief-stricken and recognizes that it is easier to tell others to feel good about their plight than to tell oneself the same thing. She admits that the game is not fun if it is really hard to play.

Still, she is determined to find a reason to feel good about her plight. She decides she is glad that she cannot walk because her accident has caused her stern aunt to soften up.

The novel ends happily: the aunt marries her former lover and Pollyanna is sent to a hospital where she learns to walk again, able to appreciate the use of her legs far more as a result of being temporarily disabled.”

. . . . . . . . . .

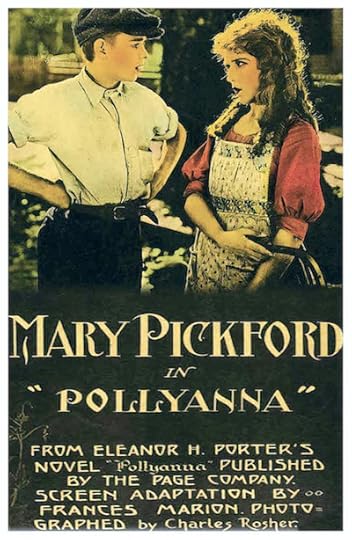

Poster for the first film adaptation of Pollyanna (1920)

. . . . . . . . . .

Sequels and adaptations

Pollyanna’s success led to a sequel, Pollyanna Grows Up, published in 1915. Pollyanna books became a kind of early franchise, with a number of sequels written by authors other than Porter. One even came out as late as 1997: Pollyanna Plays the Game by Colleen L. Reece.

Pollyanna was adapted first for the stage as a comedy called Pollyanna: The Glad Girl. Met with critical and commercial success upon its Philadelphia debut, it toured the U.S. through 1819.

The first film adaptation appeared in 1920 with Mary Pickford in the title role, her first in a storied silent film career. The film, like the play and the book before it, was a smash success.

The 1960 Disney adaptation is the best known. Hayley Mills won a special Oscar for her portrayal of Pollyanna. The film departs in some significant ways from the book; still, it was a major success.

In 1973, the BBC aired the story as a six-part series. In 1989, Disney produced a made-for-television musical version with an African-American cast. In 2018, Brazilian telenovela presented a Spanish language version titled Poliana.

And this is just a partial listing of adaptations. Apparently, something about Pollyanna resonates. Perhaps it appeals to our better natures, the part of us that wants to stay optimistic even in the face of dire situations and the everyday challenges of life.

. . . . . . . . . .

The 1960 film adaptation starring Hayley Mills

. . . . . . . . .

How the Pollyanna begins: A synopsis from serialization

Pollyanna was so popular that many newspapers serialized it the year after it appeared. The Baltimore Sun, April 30, 1914, introduced the first installment as follows:

Miss Polly Harrington, a wealthy spinster of forty has led a lonely life for many years in her house in Beldingville, Vermont. She receives the unwelcome news that, by the death of Reverend John Wittier, a poor home missionary and the widower of her late sister, his only child, Pollyanna, has been left an orphan.

Much as she dislikes the idea, Miss Polly considers it her duty to care for her niece. After she has swept the bare little attic room which has been earmarked for Pollyanna, the maid Nancy is sent to meet the small stranger, much to her chagrin.

Miss Polly, now Aunt Polly, receives the impulsive greeting of Pollyanna with icy coldness and the child is moved to tears when she sees the forlorn, hot little room where she must live.

But she meets the situation bravely, telling Nancy about the “glad game” she used to play with her father. It was a game that taught her to find something to be glad about in any trouble no matter how hard to bear.

There are no screens in Pollyanna’s attic room windows, so Aunt Polly won’t allow her to open them for fear of flies. And so, the little girl, who can’t sleep in the stifling heat, tiptoes about and makes her bed on the roof for the night.

Aunt Polly hears the unfamiliar sounds, and calls for Tom and Timothy, the servants, thinking there is a burglar on the roof. She is enraged when the “burglar” proves to bePollyanna, and as a punishment, condemns her niece to spend the rest of the night with her in her bed.

But Pollyanna’s glad game turns the punishment into a reward to the amazement and indignation of her aunt.

During her walks about the town, Pollyanna often meets “The Man.” He looks so lonely that she ventures to speak to him on several occasions and tells him her name. But this only seems to increase his confusion, and he turns and walks away in haste.

With an offering of jelly, Pollyanna is sent to the house of an invalid whose chief business in life is complaining. The little girl wins the cross woman over by combing her curly black hair in a fascinating fashion and persuading her to look at her pretty face for the first time in years.

Pollyanna tries the glad game on the invalid and undertakes to discover for her what there is to be glad about in spending all the long days flat on her back in bed.

. . . . . . . . .

Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

The author has the last word

In A 2013 essay in The Atlantic marking the book’s centenary, Ruth Graham wrote:

“Pollyanna’s ‘glad game’ goes beyond simple positive thinking. Pollyanna isn’t always cheerful; she cries over disappointments large and small, and initially refuses to play the game when she suffers a major tragedy. It’s not that she’s naturally the world’s greatest optimist; rather, optimism is a tool she uses to make herself happy.

Her gladness is Gladwellian: It’s not a state of mind, but rather a skill that becomes stronger with practice. As the freckled little guru herself put it, ‘When you’re hunting for the glad things, you sort of forget the other kind.’ Welcome to the 21st century, Pollyanna. You’ll fit right in.”

Despite the book’s incredible success and staying power, Eleanor H. Porter was often roundly criticized for unleashing this cheerful-to-a-fault heroine. In an interview, she explained:

“You know I have been made to suffer from the Pollyanna books. I have been placed often in a false light. People have thought that Pollyanna chirped that she was ‘glad’ at everything. I have never believed that we ought to deny discomfort and pain and evil; I have merely thought that it is far better to ‘greet the unknown with a cheer.'”

More about Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Pollyanna – 1960 film

Read Pollyanna online at Project Gutenberg

Listen to Pollyanna on Librivox

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter: Revisiting the Eternal Optimist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 19, 2020

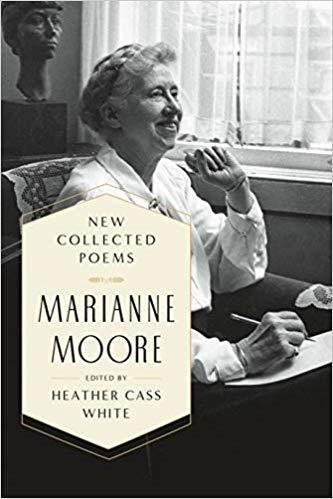

Marianne Moore

Marianne Moore (November 15, 1887 – February 5, 1972) was a poet who belonged to the American Modernist movement. Her poetry was notable for its wit, irony, and use of syllabic verse. She was also a respected translator.

At right, a 1957 photo of Marianne Moore by the noted photographer Imogen Cunningham.

Politically, Marianne was heavily involved in the women’s suffrage movement in the United States, often supporting the movement anonymously through her writing. She was viewed as a celebrity throughout much of her life, and she received numerous honorary degrees and awards for her works, including the Pulitzer Prize and the National Medal for Literature.

Early life

Marianne was born in Kirkwood, Missouri, on November 15, 1887. Her mother and father separated before she was born, and she was raised by her mother, Mary Moore. She lived with her mother and her brother in St. Louis until the age of 16, and her grandfather, a Presbyterian minister, was a highly influential figure in her life.

After her grandfather’s death in 1894, Marianne and her family lived with relatives. In 1896, Marianne moved with her mother and brother to Pennsylvania, where her mother worked as an English teacher at a private school.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

College education and beyond

In 1905, Marianne enrolled at Bryn Mawr College, majoring in history, political science, and economics. Hilda Doolittle (“H.D.”), another future poet, was Marianne’s classmate during her freshman year.

As a student, Marianne began writing short stories for the college literary magazine, and this experience inspired her to become a professional writer. Ms. Moore graduated from Bryn Mawr College with her bachelor’s degree in 1909, and she then studied typing at Carlisle Commercial College.

From 1911 through 1915, Moore worked as a teacher at Carlisle Indian School. She moved with her mother to New York City in 1918 and became an assistant at the New York Public Library in 1921.

She was introduced to many poets, including Wallace Stevens and William Carlos Williams, and began to write for the Dial, a literary magazine. From 1925 to 1929, Marianne served as acting editor of the magazine.

Early publications

Marianne’s poetry was first published in spring 1915 in The Egoist and Poetry magazines. Poetry, her first book of poems, was published in 1921 by her former classmate, Hilda Doolittle, without Marianne’s knowledge. Observations, her second book of poetry, was published in 1924 and won the Dial Award that same year.

“The Octopus,” an exploration of Mt. Rainier that is now regarded as one of Marianne’s finest poems, was included in that publication. The volume also included “Marriage,” a poem written in free verse that featured quotations.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Marianne Moore page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Major works and awards

The 1930s and 40s were to be Marianne’s most productive years. Her next book of poems, Selected Poems, was published in 1935. It included poems that had been published in Observations and other poems that were published from 1932 to 1934. This was followed in 1941 after a gap of a few years by The Pangolin and Other Verse in 1936 and What Are Years?

Her subsequent work, Nevertheless, was published in 1944 and included an anti-war poem entitled “In Distrust of Merits.” W.H. Auden remarked that the poem was one of the best pieces of poetry from the World War II period.

Collected Poems was published in 1951, and won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. In 1953, Marianne also won the Bollingen Prize. Other works from the 1950s and 60s include Like a Bulwark (1956), O to Be a Dragon (1959), and Tell Me, Tell Me: Granite, Steel, and Other Topics (1966).

Poetic style and revision

For Marianne Moore, heartfelt and precise expression was the most important aspect of the written word. Most of her poems were written in syllabic verse.

She used stanzas that had a predetermined number of syllables to structure her poetry, and she enjoyed borrowing fragments and quotations from other writers in her works. About her own work, she commented “I tend to write in a patterned arrangement, with rhymes … to secure an effect of flowing continuity … there is a great amount of poetry in unconscious/fastidiousness.”

She had a special fondness for animals, and her poems frequently featured imagery from nature. Her friend William Carlos Williams once described her early works as evoking “the vastness of the particular.” He stated that when Marianne wrote even of a seemingly small object, the reader could feel “the swirl of great events.”

The Achievement of Marianne Moore: A Biography by Eugene P. Sheehy and Kenneth A. Lohf describes her work:

“Her line is long, gathering in its wake a host of observed detail and sharply drawn images, which she leaves to stir their own unaided ripples in the reader’s imagination. Her mood is at once elegant and ironic, conversational yet restrained, the starting point of her mediations often being rare or fabulous animals.”

In her later years, Marianne revised many of her earlier poems. In The Complete Poems of Marianne Moore (1967), she reduced “Poetry,” one of her most highly regarded poems, from its original thirty-one lines to just three lines. Although her revisions generated significant controversy, she maintained that the omissions were not accidental.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

The legacy of Marianne Moore

After a series of strokes in her later life, Marianne passed away in New York City on February 5, 1972. She established a fund in her will to protect the Camperdown Elm tree in Prospect Park in New York City; she had previously written a poem about that particular tree.

After her death, Marianne was inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame in 1996. She was inducted into the New York State Writers Hall of Fame in 2012. The Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia preserved her living room in its original layout, and visitors today can view her entire library, including poetry drafts, photos, letters, and a baseball signed by Mickey Mantle.

More about Marianne Moore

On this site

12 Poems by Marianne Moore, Influential Modernist Poet

“Marriage” — A Modernist Poem by Marianne Moore (1923)

Selected works (poetry)

Poems, 1921

Observations, 1924

Selected Poems, 1935

The Pangolin and Other Verse, 1936

What Are Years, 1941

Nevertheless, 1944

A Face, 1949

Collected Poems, 1951

Like a Bulwark, 1956

Idiosyncrasy and Technique, 1958

O to Be a Dragon, 1959

Dress and Kindred Subjects (1965)

Tell Me, Tell Me: Granite, Steel and Other Topics (1966)

The Complete Poems of Marianne Moore (1967)

The Accented Syllable (1969)

The Complete Poems (1982)

Complete Poems (1994)

Becoming Marianne Moore: The Early Poems, 1907 –1 924 (2002)

Poems of Marianne Moore, ed by Grace Schulman (2003)

Selected Works (prose)

The Complete Prose of Marianne Moore (1986)

A Marianne Moore Reader (1961)

Predilections: Literary Essays (1955)

Biographies, letters, and literary criticism

The Achievement of Marianne Moore: A Biography by Eugene P. Sheehy and Kenneth A. Lohf

Marianne Moore: A Collection of Critical Essays, ed. by Charles Tomlinson (1969)

Marianne Moore, Subversive Modernist by Taffy Martin (1986)

The Poetry of Marianne Moore: A Study in Voice and Value by Margaret Holley (1987)

Marianne Moore: A Literary Life by Charles Molesworth (1990)

Marianne Moore: The Art of a Modernist, ed. by Joseph Parisi (1990)

Marianne Moore: Questions of Authority by Cristanne Miller (1995)

The Selected Letters of Marianne Moore (1997)

More information and sources

Poem Hunter

Poetry Foundation

Poets.org

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Marianne Moore appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 18, 2020

10 Celebrated Poems by Maya Angelou

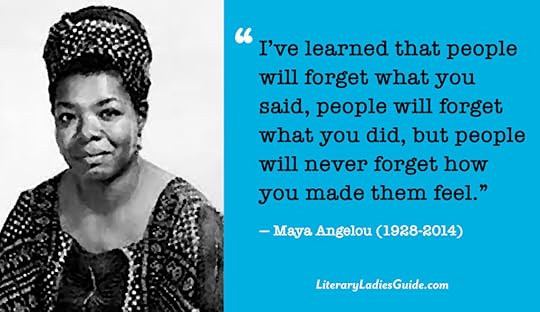

Maya Angelou (1928 – 2014) was a multitalented American author, actress, screenwriter, and civil rights activist. She was also a prolific poet, publishing collections throughout her writing career. This selection of 10 celebrated poems by Maya Angelou is a sampling spanning nearly three decades of her prolific output.

Angelou is perhaps best known for her 1969 memoir, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. It made literary history as the first nonfiction best-seller by an African-American woman. But her poetry has also broken through academic circles, with poems like “Still I Rise” and “Phenomenal Woman” as part of American literary consciousness.

Her poetry speaks to personal power, female identity, and courage. Find links to analyses following the end of each poem.

Collections of Maya Angelou’s poetry include:

Just Give Me A Cool Drink Of Water ‘fore I Diiie (1971)

Oh Pray My Wings Are Gonna Fit Me Well (1975)

And Still I Rise (1978)

On The Pulse Of Morning (the inaugural poem, 1993)

Life Doesn’t Frighten Me (1993)

Phenomenal Woman (2011)

The Complete Poetry (2015)

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Maya Angelou

. . . . . . . . . .

When I Think About Myself (1971)

When I think about myself,

I almost laugh myself to death,

My life has been one great big joke,

A dance that’s walked

A song that’s spoke,

I laugh so hard I almost choke

When I think about myself.

Sixty years in these folks’ world

The child I works for calls me girl

I say “Yes ma’am” for working’s sake.

Too proud to bend

Too poor to break,

I laugh until my stomach ache,

When I think about myself.

My folks can make me split my side,

I laughed so hard I nearly died,

The tales they tell, sound just like lying,

They grow the fruit,

But eat the rind,

I laugh until I start to crying,

When I think about my folks.

(From Just Give Me A Cool Drink Of Water ‘fore I Diiie, 1971)

Analysis of “When I Think About Myself”

. . . . . . . . . .

Alone (1975)

Lying, thinking

Last night

How to find my soul a home

Where water is not thirsty

And bread loaf is not stone

I came up with one thing

And I don’t believe I’m wrong

That nobody,

But nobody

Can make it out here alone.

Alone, all alone

Nobody, but nobody

Can make it out here alone.

There are some millionaires

With money they can’t use

Their wives run round like banshees

Their children sing the blues

They’ve got expensive doctors

To cure their hearts of stone.

But nobody

No, nobody

Can make it out here alone.

Alone, all alone

Nobody, but nobody

Can make it out here alone.

Now if you listen closely

I’ll tell you what I know

Storm clouds are gathering

The wind is gonna blow

The race of man is suffering

And I can hear the moan,

‘Cause nobody,

But nobody

Can make it out here alone.

Alone, all alone

Nobody, but nobody

Can make it out here alone.

(From Oh Pray My Wings Are Gonna Fit Me Well ©1975)

Analysis of “Alone”

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

. . . . . . . . . .

Still I Rise (1978)

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

Does my sassiness upset you?

Why are you beset with gloom?

’Cause I walk like I’ve got oil wells

Pumping in my living room.

Just like moons and like suns,

With the certainty of tides,

Just like hopes springing high,

Still I’ll rise.

Did you want to see me broken?

Bowed head and lowered eyes?

Shoulders falling down like teardrops,

Weakened by my soulful cries?

Does my haughtiness offend you?

Don’t you take it awful hard

’Cause I laugh like I’ve got gold mines

Diggin’ in my own backyard.

You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.

Does my sexiness upset you?

Does it come as a surprise

That I dance like I’ve got diamonds

At the meeting of my thighs?

Out of the huts of history’s shame

I rise

Up from a past that’s rooted in pain

I rise

I’m a black ocean, leaping and wide,

Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.

(from And Still I Rise: A Book of Poems ©1978)

Analysis of “Still I Rise”

. . . . . . . . . .

Phenomenal Woman (1978)

Pretty women wonder where my secret lies.

I’m not cute or built to suit a fashion model’s size

But when I start to tell them,

They think I’m telling lies.

I say,

It’s in the reach of my arms

The span of my hips,

The stride of my step,

The curl of my lips.

I’m a woman

Phenomenally.

Phenomenal woman,

That’s me.

I walk into a room

Just as cool as you please,

And to a man,

The fellows stand or

Fall down on their knees.

Then they swarm around me,

A hive of honey bees.

I say,

It’s the fire in my eyes,

And the flash of my teeth,

The swing in my waist,

And the joy in my feet.

I’m a woman

Phenomenally.

Phenomenal woman,

That’s me.

Men themselves have wondered

What they see in me.

They try so much

But they can’t touch

My inner mystery.

When I try to show them

They say they still can’t see.

I say,

It’s in the arch of my back,

The sun of my smile,

The ride of my breasts,

The grace of my style.

I’m a woman

Phenomenally.

Phenomenal woman,

That’s me.

Now you understand

Just why my head’s not bowed.

I don’t shout or jump about

Or have to talk real loud.

When you see me passing

It ought to make you proud.

I say,

It’s in the click of my heels,

The bend of my hair,

the palm of my hand,

The need of my care,

‘Cause I’m a woman

Phenomenally.

Phenomenal woman,

That’s me.

(From And Still I Rise © 1978)

Analysis of “Phenomenal Woman”

. . . . . . . . . .

Woman Work (1978)

I’ve got the children to tend

The clothes to mend

The floor to mop

The food to shop

Then the chicken to fry

The baby to dry

I got company to feed

The garden to weed

I’ve got shirts to press

The tots to dress

The can to be cut

I gotta clean up this hut

Then see about the sick

And the cotton to pick.

Shine on me, sunshine

Rain on me, rain

Fall softly, dewdrops

And cool my brow again.

Storm, blow me from here

With your fiercest wind

Let me float across the sky

‘Til I can rest again.

Fall gently, snowflakes

Cover me with white

Cold icy kisses and

Let me rest tonight.

Sun, rain, curving sky

Mountain, oceans, leaf and stone

Star shine, moon glow

You’re all that I can call my own.

(From And Still I Rise, 1978)

Analysis of “Woman Work”

. . . . . . . . .

Caged Bird (1983)

A free bird leaps

on the back of the wind

and floats downstream

till the current ends

and dips his wing

in the orange sun rays

and dares to claim the sky.

But a bird that stalks

down his narrow cage

can seldom see through

his bars of rage

his wings are clipped and

his feet are tied

so he opens his throat to sing.

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

The free bird thinks of another breeze

and the trade winds soft through the sighing trees

and the fat worms waiting on a dawn bright lawn

and he names the sky his own

But a caged bird stands on the grave of dreams

his shadow shouts on a nightmare scream

his wings are clipped and his feet are tied

so he opens his throat to sing.

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

(From Shaker, Why Don’t You Sing? © 1983)

Analysis of “Caged Bird”

. . . . . . . . .

Maya Angelou Quotes to Live By

. . . . . . . . . .

Life Doesn’t Frighten Me (1993)

Shadows on the wall

Noises down the hall

Life doesn’t frighten me at all

Bad dogs barking loud

Big ghosts in a cloud

Life doesn’t frighten me at all

Mean old Mother Goose

Lions on the loose

They don’t frighten me at all

Dragons breathing flame

On my counterpane

That doesn’t frighten me at all.

I go boo

Make them shoo

I make fun

Way they run

I won’t cry

So they fly

I just smile

They go wild

Life doesn’t frighten me at all.

Tough guys fight

All alone at night

Life doesn’t frighten me at all.

Panthers in the park

Strangers in the dark

No, they don’t frighten me at all.

That new classroom where

Boys all pull my hair

(Kissy little girls

With their hair in curls)

They don’t frighten me at all.

Don’t show me frogs and snakes

And listen for my scream,

If I’m afraid at all

It’s only in my dreams.

I’ve got a magic charm

That I keep up my sleeve

I can walk the ocean floor

And never have to breathe.

Life doesn’t frighten me at all

Not at all

Not at all.

Life doesn’t frighten me at all.

(From a children’s book of the same title, 1993)

Analysis of “Life Doesn’t Frighten Me”

. . . . . . . . .

On the Pulse of Morning (1993)

A Rock, A River, A Tree

Hosts to species long since departed,

Marked the mastodon,

The dinosaur, who left dried tokens

Of their sojourn here

On our planet floor,

Any broad alarm of their hastening doom

Is lost in the gloom of dust and ages.

But today, the Rock cries out to us, clearly, forcefully,

Come, you may stand upon my

Back and face your distant destiny,

But seek no haven in my shadow,

I will give you no hiding place down here.

You, created only a little lower than

The angels, have crouched too long in

The bruising darkness

Have lain too long

Facedown in ignorance,

Your mouths spilling words

Armed for slaughter.

The Rock cries out to us today,

You may stand upon me,

But do not hide your face.

(From On the Pulse of Morning,© 1993)

Analysis of “On the Pulse of the Morning”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Maya Angelou page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Touched by An Angel (1995)

We, unaccustomed to courage

exiles from delight

live coiled in shells of loneliness

until love leaves its high holy temple

and comes into our sight

to liberate us into life.

Love arrives

and in its train come ecstasies

old memories of pleasure

ancient histories of pain.

Yet if we are bold,

love strikes away the chains of fear

from our souls.

We are weaned from our timidity

In the flush of love’s light

we dare be brave

And suddenly we see

that love costs all we are

and will ever be.

Yet it is only love

which sets us free.

. . . . . . . . .

A Brave and Startling Truth (1995)

We, this people, on a small and lonely planet

Traveling through casual space

Past aloof stars, across the way of indifferent suns

To a destination where all signs tell us

It is possible and imperative that we learn

A brave and startling truth

And when we come to it

To the day of peacemaking

When we release our fingers

From fists of hostility

And allow the pure air to cool our palms

When we come to it

When the curtain falls on the minstrel show of hate

And faces sooted with scorn are scrubbed clean

When battlefields and coliseum

No longer rake our unique and particular sons and daughters

Up with the bruised and bloody grass

To lie in identical plots in foreign soil

When the rapacious storming of the churches

The screaming racket in the temples have ceased

When the pennants are waving gaily

When the banners of the world tremble

Stoutly in the good, clean breeze

When we come to it

When we let the rifles fall from our shoulders

And children dress their dolls in flags of truce

When land mines of death have been removed

And the aged can walk into evenings of peace

When religious ritual is not perfumed

By the incense of burning flesh

And childhood dreams are not kicked awake

By nightmares of abuse

When we come to it

Then we will confess that not the Pyramids

With their stones set in mysterious perfection

Nor the Gardens of Babylon

Hanging as eternal beauty

In our collective memory

Not the Grand Canyon

Kindled into delicious color

By Western sunsets

Nor the Danube, flowing its blue soul into Europe

Not the sacred peak of Mount Fuji

Stretching to the Rising Sun

Neither Father Amazon nor Mother Mississippi who, without favor,

Nurture all creatures in the depths and on the shores

These are not the only wonders of the world

When we come to it

We, this people, on this minuscule and kithless globe

Who reach daily for the bomb, the blade and the dagger

Yet who petition in the dark for tokens of peace

We, this people on this mote of matter

In whose mouths abide cankerous words

Which challenge our very existence

Yet out of those same mouths

Come songs of such exquisite sweetness

That the heart falters in its labor

And the body is quieted into awe

We, this people, on this small and drifting planet

Whose hands can strike with such abandon

That in a twinkling, life is sapped from the living

Yet those same hands can touch with such healing, irresistible tenderness

That the haughty neck is happy to bow

And the proud back is glad to bend

Out of such chaos, of such contradiction

We learn that we are neither devils nor divines

When we come to it

We, this people, on this wayward, floating body

Created on this earth, of this earth

Have the power to fashion for this earth

A climate where every man and every woman

Can live freely without sanctimonious piety

Without crippling fear

When we come to it

We must confess that we are the possible

We are the miraculous, the true wonder of this world

That is when, and only when

We come to it.

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 10 Celebrated Poems by Maya Angelou appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 16, 2020

4 Intrepid American Female Newspaper Publishers of the 1800s

For a small number of American female journalist-reformers of the 1800s, starting their own newspapers became a matter of necessity. Refused the opportunity to report on matters of importance by male-dominated mainstream newspapers, they took matters into their own hands.

Launching their own newspapers became platforms for raising awareness of the justice issues they fought for.

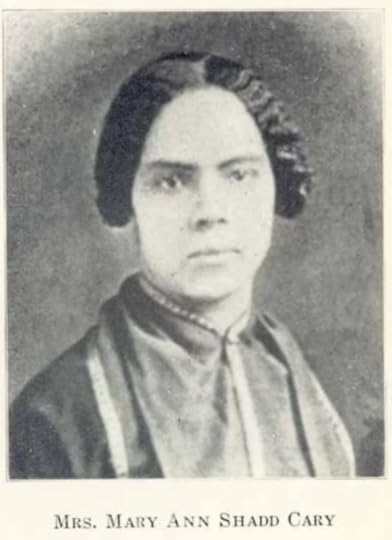

Anne Newport Royall, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, and Jovita Idár are no longer familiar names; Ida B. Wells (pictured above right) might be better known to those interested in African-American history. But all deserve to be better known and deserve a place of honor as publisher-reformers in an era when women’s voices were more often silenced than heard.

Fighting for the right to report

Even before women began fighting for the right to vote, they fought for the right to report. Women journalists wore their independence proudly, often refusing to conform to gender roles and society’s random limits for women.

In the 1800s, the few women who managed to step inside the world of newspaper work at all were often steered to writing about society, fashion, and domestic topics.

Those who wanted to report on hard news and social justice issues were usually thwarted. For a few undaunted women, there was just one remedy —to publish newspapers of their own.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

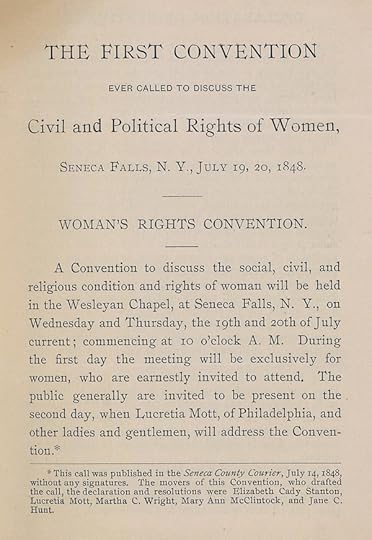

Seneca Falls Convention, 1848 — a turning point

The Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 proved to be something of a national turning point for American women. It was the first national event devoted to waking women up to their second-class citizenship.

Husbands and fathers controlled the lives of wives and daughters; females couldn’t own property or sign contracts; and of course, they couldn’t vote. Job prospects were mainly limited to poorly paid service and domestic work or teaching.

At the same time, the issue of slavery was tearing the country apart. Many of the same people (both male and female) involved with women’s rights were also involved in the abolition movement. Journalists often crossed paths and pens working for these causes and writing for anti-slavery and pro-women newspapers.

Reform-minded journalists

Following the Civil War, the slavery question may have been legally settled, but life for African-Americans continued to be challenging, if not downright dreadful. The women’s rights movement was in full force, but progress was painfully slow.

Reform-minded journalists weren’t willing to wait for permission to report on the injustice woven into every aspect of American life — civil rights, women’s rights, labor, immigration, education, and more.

Though women who started newspapers were few and far between, the listing that follows is by no means a complete overview. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, for example, started and ran the women’s suffrage newspaper, The Revolution, from 1868 to 1872. But their names live on in the American consciousness. And you can read about Victoria Woodhull and The Weekly, a radical reform newspaper she launched with her husband and sister.

Here we focus on four women newspaper publishers who aren’t as well known today. Their lives and the spirit of the work they did deserve to be remembered and honored today, as they blazed trails for today’s female journalists and publishers.

. . . . . . . . .

Anne Newport Royall (1769 – 1854)