Nava Atlas's Blog, page 61

November 20, 2019

6 Literary Gift Books for 2019 Holiday Giving and Beyond

For the book-lover in your life, here are a half dozen literary gift books — all related, directly or fancifully — to a few of the beloved literary ladies on this site. These 2019 publications (with the exception of the Brontë collection boxed set, late 2018), offer some fresh takes in homage to (or by) some of our favorite authors.

Here you’ll find a beautiful, full-color book on Emily Dickinson’s affinity for gardens and botany; a new collection of words of wisdom from Toni Morrison; quotes from Agatha Christie’s amateur sleuth Miss Marple; a retelling of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice from the standpoint of Charlotte Lucas; a fun compilation of Austen-inspired cocktails; and a beautiful boxed set of the Brontë sisters most iconic novels.

. . . . . . . . .;

Emily Dickinson’s Gardening Life

by Marta McDowell

From the publisher: “In Emily Dickinson’s Gardening Life (Timber Press, $24.95), Marta McDowell traces the beloved poet’s life as a gardener and reveals the many ways in which her passion for plants is evident in her extensive collection of poems and letters. The book follows Emily Dickinson’s love of nature and plants through an entire year — forced hyacinth bulbs in winter, saved seeds in the summer, and pressed flowers to include in correspondence.

Packed with contemporary and historical photography, botanical illustrations, excerpts from Dickinson’s letters, and some of her most cherished poetry, this revealing book is a must-have keepsake for Dickinson fans.”

Emily Dickinson’s Gardening Life on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

The Measure of Our Lives:

A Gathering of Wisdom by Toni Morrison

The Measure of Our Lives: A Gathering of Wisdom by Toni Morrison, is described by the publisher as: “At once the ideal introduction to Toni Morrison and a lovely and moving keepsake for her devoted readers: a treasury of quotations from her work. With a foreword by Zadie Smith.

This inspirational book juxtaposes quotations, one to a page, drawn from Toni Morrison’s entire body of work, both fiction and nonfiction–from The Bluest Eye to God Help the Child, from Playing in the Dark to The Source of Self-Regard–to tell a story of self-actualization. It aims to evoke the totality of Toni Morrison’s literary vision. The Measure of Our Lives brims with elegance of style and mind and moral authority.”

The Measure of Our Lives on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Murder, She Said: The Quotable Miss Marple

Murder, She Said: The Quotable Miss Marple by Agatha Christie (William Morrow, $16.99) is described by its publisher: “Christie’s witty and wise sleuth, Miss Marple, takes center stage in this stylishly packaged collection just in time for the holidays. The razor-sharp mind of the world’s favorite armchair sleuth is brilliantly revealed in Murder, She Said, an anthology of Miss Marple insights and bon mots, curated from Agatha Christie’s classic novels featuring the delightful amateur detective.

The perfect addition to the Miss Marple mysteries for both aficionados and new fans, this companion volume also includes Agatha Christie’s illuminative essay, ‘Does a Woman’s Instinct Make Her a Good Detective?'”

Murder, She Said on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

The Clergyman’s Wife: A Pride and Prejudice Novel

by Molly Greeley

Retellings of Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen are perennial favorites in the literary world. Most feature the ever‐popular Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy, sometimes set in different time periods or new worlds. The Clergyman’s Wife (William Morrow, $15.99) is the first retelling about Charlotte Lucas, and, with its themes of status, love, and loss, will be sure to attract smart women who read, and will resonate with Pride and Prejudice fans.

Engrossing and charming in its own right, The Clergyman’s Wife is full of sharp observations—heartfelt and occasionally subversive‐‐about one woman’s experience of motherhood, marriage, loss, love, and hope in Jane Austen’s 18th century.

The Clergyman’s Wife on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

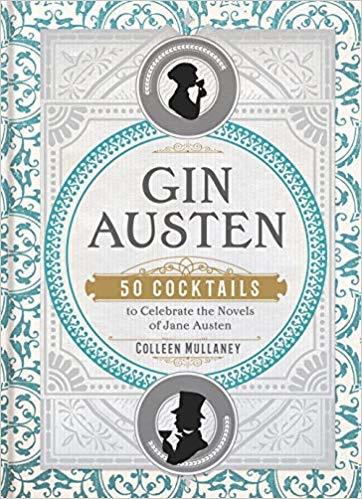

Gin Austen by Colleen Mullaney

Another gift for Janeites, Gin Austen: 50 Cocktails to Celebrate the Novels of Jane Austen by Colleen Mullaney (Sterling Epicure, $16.95) is a clever little book celebrating the exquisite novels of Jane Austen with boozy delicacies and attendant wordplay. From the publisher:

“In six enduring novels, Jane Austen captured the fancies and foibles of Regency England, and this book celebrates the picnics, luncheons, dinner parties, and glamorous balls of Austen’s world. Learn what she and her characters might have imbibed, and what tools, glasses, ingredients, and skills you simply must possess. Sample a cocktail from Gin Austen.”

Gin Austen on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

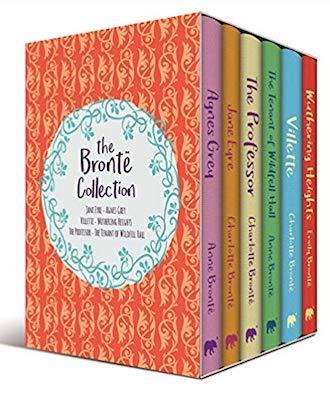

The Brontë Collection Boxed Set

This boxed set features the most iconic works of the Brontë sisters (Arcturus Publishing Limited , $33.49). From the publisher: “Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë were not prolific novelists, but those that they did write have become some of the best-loved works in English literature.

Collected together here are six titles, beautifully bound, that make the perfect introduction to the sisters’ work. They include: Jane Eyre; Agnes Grey; Villette; Wuthering Heights; The Professor, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. Moving from the wilds of Yorkshire to small-town France, these are tales of passion and romance.”

The Brontë Collection Box Set on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 6 Literary Gift Books for 2019 Holiday Giving and Beyond appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 17, 2019

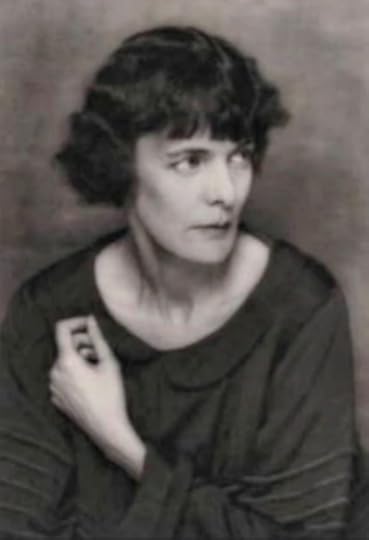

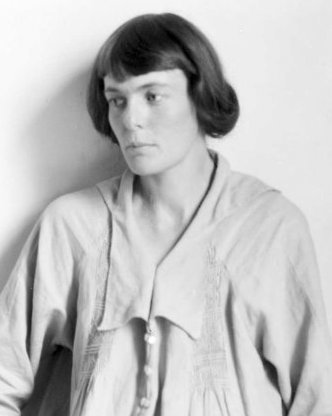

Hilda Doolittle (H.D.)

Hilda Doolittle (September 10, 1886 – September 27, 1961) was an American-born poet, novelist, translator, and essayist who wrote under the pen name H.D. Her work was heavily influenced by the effects of the World War I and the subsequent trends of modernism, psychoanalysis, and feminism.

Her work is often framed within the context of other important modernist writers such as T.S.Eliot, Ezra Pound, Marianne Moore, and William Carlos Williams. Today, she’s best remembered for her innovation and experimental approach in poetry.

Early life

Hilda’s early years were spent in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, in a close-knit Moravian community founded in the 18th century by a small group of strict Protestants. Her father Charles was a professor of astronomy at Lehigh University, while her mother Helen taught music and painting at the Moravian Seminary. Later, when Hilda was nine years old, her father became professor of astronomy at the University of Pennsylvania and the family moved to the Flower Observatory in Upper Darby.

The only surviving daughter in a family of five sons, she was her father’s favorite child and he was ambitious for her to become a scientist like himself. Hilda, however, was more drawn to the arts and struggled to reconcile the two when her father forbade art school and her mother, a traditional wife who bowed to her husband’s opinions and decisions, did not support her ambitions.

Hilda was an intelligent child and did well at school. In 1905 she enrolled at Bryn Mawr instead of the art college that she would have preferred, but withdrew less than two years later after achieving poor results in both maths and English. She longed instead for a stimulating artistic community in which to share ideas and her love of books and poetry, and felt like “a disappointment to her father, an odd duckling to her mother, an importunate overgrown, unincarnated entity that had no place here.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Intertwined relationships

Rather than in conventional education, Hilda found the stimulation she craved in her personal relationships. She had met Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams around 1901 when both men were studying at the University of Pennsylvania (where her father taught). Both were already passionate about literature and regularly visited Hilda at the Flower Observatory to share their love of books and poetry. By the time Hilda started at Bryn Mawr, she and Pound were lovers.

Pound was Hilda’s first love, an intense one, and the one she often returned to in later writings. Her father’s disapproval did not halt their engagement, but Hilda became increasingly disillusioned with the idea of marriage as their relationship progressed. She had dreamed of a bohemian, free life with Pound, but felt that the longer they were together the more conventional their relationship became. He, it seemed, was the writer, and she, like so many before her, merely his muse.

This disenchantment paralleled her deepening involvement with Frances Josepha Gregg, whom she met through a college friend in around 1910. Their affair was a troubled and stormy one; while Hilda found some of the freedom she craved and the inspiration to write, she was devastated when Gregg had a short liaison with Pound. Loving both, Hilda felt torn, and the pull of her bisexuality remained one of the central themes in her life and writing.

Expatriate life and marriage

In 1911 Hilda set off for a short visit to Europe with Frances. Pound was already in Europe and had spent time there in previous years, and through him, she found an almost ready-made literary circle that gave her the artistic and creative stimulation she had been seeking.

Although their romantic relationship was over, Pound introduced her to many of the writers and artists who would form her community — Richard Aldington, T.S.Eliot, John Gould Fletcher, and Ford Madox Ford.

Unwilling to return to the US, Hilda eventually persuaded her parents to let her stay in London but was hurt once more when Frances refused to stay with her. Frances’ return to the US and her subsequent marriage marked the end of the short but intense affair between the two women, although they stayed in touch periodically until 1939.

Now settled in London, Hilda began to spend more time expanding her circle and working on her writing. She spent increasing amounts of time with Richard Aldington, with whom she shared poetry and worked on translations from Greek. It was the first time she had felt like an artistic equal in a relationship, and after trips to Italy and Paris, they married on October 1913. Apart from short trips much later in life, she would never again return to the U.S.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Imagist poetry and a nom de plume

Hilda’s writing career was already well underway by the time she married. She had a strong reputation as one of the best of the new ‘Imagist’ poets — a short-lived but influential movement in poetry that favored hardness, clarity, and intensity in words.

In September 1912, in the tea room at the British Museum, HD gave Pound three new poems, Epigram, Hermes of the Ways, and Priapus (later renamed Orchard). Later, in her memoir End to Torment, Hilda would recall how Pound said, “but this is poetry!” After some impromtu editing, he said that he would send them to Harriet Monroe of Poetry magazine, and at the bottom of the page he scrawled ‘H.D., Imagiste.’

Hilda accepted the new name, and the loss of her surname, presumably with enthusiasm (although recent commentators have pointed out that Pound’s power and autonomy in this renaming suggest an ominous undertone to his support — something that she would later explore in her roman à clef HERmione).

She certainly enjoyed the ambiguity that the initials created, and in 1917 was furious when Amy Lowell published an author photo without her permission in Tendencies in Modern American Poetry, saying that “the initials … had no identity attached; they could have been pure spirit. But with this I’m embodied.”

Monroe published the new poems in the January 1913 edition of Poetry under the name ‘H.D., Imagiste,’ and more poems rapidly followed with the ‘Imagiste’ signature. An ‘Imagist’ anthology was published in 1914, which included poems by not only H.D. but also Richard Aldington, F.S.Flint, and Pound, and which was financed by Amy Lowell. After the publication of three more anthologies, the group effectively disbanded at the end of WW1.

H.D’s first book of poetry, Sea Garden, was published in 1916 towards the end of the Imagist years and marked the beginning of her use of the natural world and its symbolism to explore ideas of consciousness and spirituality. She was expanding her interest in the classics, and together with Aldington started the Poets’ Translation Series of pamphlets which highlighted translation from Latin and Greek.

She also became assistant editor of the magazine The Egoist (effectively replacing her husband who had enlisted in the army to avoid conscription), and won awards from Poetry magazine and from the Little Review for her work.

A Post-war breakdown

While her literary and artistic career was flourishing, H.D.’s personal relationship with Aldington was deteriorating. Their only child was stillborn in 1915, and Aldington subsequently had several affairs, including one with H.D.’s close friend Brigit Patmore. When her brother Gilbert was killed in action in 1918, H.D. retreated to Cornwall to stay with the composer Cecil Gray, whom she had met through their mutual friend D.H.Lawrence.

With her husband’s full knowledge, H.D. embarked on an affair with Gray which resulted in another pregnancy. While this upset Aldington, she refused to either abort the child or marry Gray, and Aldington promised to care for both her and the child despite the effective end of their marriage.

Her daughter Frances Perdita Aldington (known as Perdita) was born in March 1919, but the trauma of the war and a serious bout of influenza just before she was due to give birth left H.D. shattered. In her memoirs, she would refer to March 1919 as a “psychic death” from which she didn’t really recover until World War II. The result was her own personal “war phobia” — for years afterwards, the threat or reality of war triggered associations of personal and societal breakdown.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Bryher and the inter-war years

Towards the end of the war, H.D. met Annie Winifred Ellerman, known as Bryher. Also a writer, Bryher came from a wealthy family and was the daughter of shipping magnate Sir John Ellerman. The two became lovers and would remain intimate for the rest of H.D.’s life, supporting and sustaining each other and sharing the responsibility of parenting H.D.’s daughter Perdita.

However, theirs was not an exclusive partnership. Both took other lovers, and in 1921 Bryher entered into a marriage of convenience with the American writer and publisher Robert McAlmon.

This arrangement enabled Bryher to keep her traditional family at arm’s length, and allowed McAlmon to use her wealth to set up his own press, Contact Editions. When they divorced in 1927, Bryher went on to marry H.D.’s friend and lover Kenneth Macpherson. Macpherson and Bryher later formally adopted Perdita to avoid any parental challenges from Aldington.

The relationship between Bryher and H.D. was never an easy one. H.D. still struggled with the effects of trauma from the war, while Bryher grappled with gender and sexual identities and with suicidal depressions. However, their travels from 1919 through 1923 — to England, Greece, New York, Paris, and Switzerland, sometimes with McAlmon in tow as well — gave H.D. renewed inspiration and impetus to write.

She started three projected cycles of novels: the first, Magna Graeca, consisted of Palimpsest (1921) and Hedylus (1928) which were heavily inspired by Greece and the classics; the second, Madrigal, consisted of HERmione, Bid Me To Live, Paint It Today and Asphodel, all of which were mostly autobiographical, and focused both on women as artists and the tension between heterosexual and lesbian desire.

The third cycle, Borderline, included the novellas Kora and Ka and The Usual Star, dealing with different psychic states and their relationship to reality. H.D. also published four full-length volumes of poetry and one verse drama, many of which were inspired by her trips to Greece and Egypt and which reinterpret the classical myths and the role of women in them. Heavily influenced during this period by Sappho, she published translations of Sappho’s work as well as an essay.

H.D. wrote constantly, and in a letter to her American friend Viola Jordan said, “I sit at my typewriter until I drop. I have in some way, to justify my existence, and then it is also a pure ‘trade’ with me now. It is my ‘job’.”

She suffered a period of severe writer’s block during the 1930s but continued to maintain and expand her circle of avant-garde literary and artistic friends that now included Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, Nancy Cunard, Man Ray, Berenice Abbott, Sylvia Beach, and Marianne Moore.

Hilda maintained an unusual family life, living together with Bryher, Macpherson, and Perdita in Switzerland. Their common passions were literature and cinema. In 1927 Bryher and Macpherson established the film journal Close Up, to which H.D. contributed several reviews.

She also acted in three films directed by Macpherson: Wing Beat (1927), Foothills (1928) and Borderline (1930). At one point she thought seriously about becoming an actor; however the rise of fascism in Berlin had a heavy impact on the European film industry and Close Up folded in 1933.

Psychoanalysis, Freud, and World War II

Just as important to H.D.’s creativity and direction was the science of psychoanalysis. She met Sigmund Freud in 1927 and began analysis with Hanns Sachs in 1928, largely funded by Bryher (who at one point planned on becoming an analyst herself).

In 1933, she began sessions with Freud himself, starting what would become a lifelong studentship. Daily sessions in Vienna were cut short by the rise of Nazism, but she continued less intensive analysis and her memoir Tribute to Freud was published in 1956.

The late 1930s were difficult years. The rise of fascism triggered H.D.’s “war phobia,” which she didn’t feel that she could discuss with Freud because he was Jewish, and she ultimately cut all ties to her former lover Ezra Pound because of his pro-Fascist position.

Bryher, meanwhile, assisted over 100 refugees, mostly Jewish, in escaping Germany between 1933 and 1939. When war broke out in 1939, H.D. and Bryher moved to London.

Far from providing a retreat, living in London confronted H.D. with the worst of the war. She sought to find some meaning in the catastrophe by delving deep into hermetic tradition, finding there a larger pattern that pointed to regeneration amidst the rubble.

Like Eliot’s journey through the wasteland, H.D.’s journey through London in the war took her through a “city of ruin” and into an almost religious epiphany that appears in the form, not of the established church, but of a woman who was “Love, the Creator.”

H.D. had a resurgence of creativity in her writing, and during the 1940s wrote Bid Me To Live (published in 1960), The Gift (her memoir of her childhood and family life in Pennsylvania, published in 1980), and Trilogy (1942 –1944), consisting of The Walls do not Fall, Tribute to the Angels and The Flowering of the Rod. Her new work was praised highly by other writers, friends and reviewers, including Marianne Moore and Edith Sitwell.

. . . . . . . . . .

Hilda Doolittle (H.D.) page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Post-war writing and later years

H.D. took great comfort in spirituality throughout the war and often attended spiritualist circles and seances. Bryher, however, was not a believer, and tensions grew between them as H.D. became more and more involved. In addition, history appeared to be repeating itself as, at the end of the war, H.D. suffered a severe breakdown triggered by news of the atomic bomb, and exacerbated by severe anemia and a bout of meningitis.

As news from Japan filtered through to the West, and as she attended more and more seances and spiritualist meetings, H.D. believed that World War Three had begun. Unable to persuade her otherwise, Bryher eventually took her to a clinic in Switzerland in May 1946. While daily letters and regular visits attest to their continued intimacy, the two would never live together again.

H.D. recovered within 6 months, and once again emerged to another period of intense creativity. Her last years saw her produce an extraordinary amount of poetry, most notably Helen in Egypt, Sagesse, Winter Love and Hermetic Definition. Living alone, mostly in Switzerland and Italy and with visits to the US to see her grandchildren, H.D. was able to concentrate on her writing. She was the recipient of the poetry award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1960.

After a brief illness and subsequent stroke, H.D. died in Zurich on September 27, 1961 and her ashes were taken back to Bethlehem, PA. Fittingly, her epitaph is a poem:

So I may say,

“I died of living,

having lived one hour”;

So they may say,

“she died soliciting

illicit fervour,”

So you may say,

“Greek flower; Greek ecstasy

reclaims for ever

one who died

following

intricate song’s lost measure.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is an author, poet and artist with a serious case of wanderlust. She is originally from the UK, but has spent time abroad in Europe, the United States and the Bahamas. When not traveling or working on her current projects — a chapbook of poetry, “The Cabinet of Lost Things,” and a novel based on the life of modernist writer and illustrator Djuna Barnes — she can be found with her nose in a book, daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Visit her on the web at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Hilda Doolittle (H.D.)

Major Works

Poetry collections

Sea Garden (1916)

The God (1917)

Choruses from Iphigenia in Aulis (1919)

Translations (1920)

Hymen (1921)

Heliodora and Other Poems (1924)

Hippolytus Temporizes (1927)

Red Roses for Bronze (1932)

Euripides’ Ion (1937)

The Walls Do Not Fall (1944)

Tribute to the Angels (1945)

Trilogy (1946)

The Flowering of the Rod (1946)

By Avon River (1949)

Helen in Egypt (1961)

Prose

works

Notes on Thought and Vision (1919)

Palimpsest (1926)

Kora and Ka (1930)

Nights (1935)

The Hedgehog (1936)

Tribute to Freud (1956)

Bid Me to Live (1960)

Autobiography

Bid Me to Live (1960)

End to Torment: A Memoir of Ezra Pound (posthumous, 1979)

Biography and Letters

Herself Defined: The Poet HD and Her World by Barbara Guest (1984)

Richard Aldington & H. D.: The Early Years in Letter, ed. by Caroline Zilboorg (1995)

Analyzing Freud: The Letters of H.D., Bryher and Their Circle (2002)

Posthumously published works

HERmione, New Directions (1981)

The Gift, New Directions (1982)

Paint it Today (1921;, published 1992)

Asphodel (1921–22; published 1992)

Pilate’s Wife (1929-1934; published 2000)

The Sword Went Out to Sea (1946–47; published 2007)

Majic Ring (1943–44; published 2009)

White Rose and the Red (1948; published 2009)

The Mystery (written 1948–51; published 2009)

Vale Ave. (2013)

More information and sources

H.D. International Society

Representative Poetry Online (University of Toronto)

Teaching H.D.: Curriculum and Resources

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of H.D.’s works on Goodreads

Poetry Foundation

Academy of American Poets

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Hilda Doolittle (H.D.) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 13, 2019

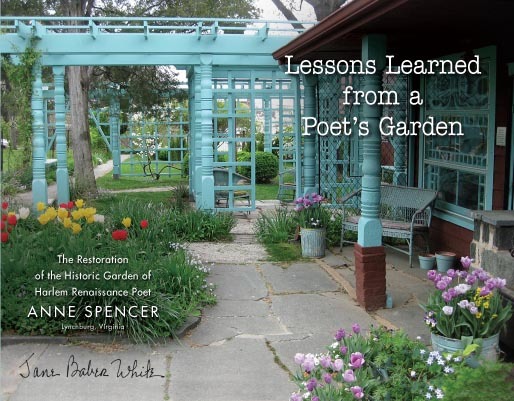

Anne Spencer

Anne Spencer (born Annie Bethel Bannister; February 6, 1882 – July 27, 1975) was an American poet, teacher, librarian, gardener, and civil rights activist. She’s best known for being an important figure of the Harlem Renaissance and the second African American poet to be included in the Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry.

Anne was born in Henry County, Virginia, to Joel Cephus Bannister and Sarah Louise Scales. Both parents were part of the first generation of African Americans born into bondage whose childhood followed the end of slavery. As an only child, she was the center of her parent’s lives and they were determined to make a better life for her.

Early years

Soon after Anne’s birth, the family moved to Martinsville, where her father opened a saloon. Within a few years, her parents started to have disagreements in the way they should raise her, which ultimately led to the end of their relationship.

After her parents’ separation, Anne moved with her mother to West Virginia and settled in Bramwell, a town that was somewhat averse to accepting African Americans and immigrants. Her mother also changed Anne’s name to Annie Scales, her own maiden name.

Her mother worked hard as a cook at a local inn to support their new life in Bramwell. While she worked, William and Willie Belle Dixie, a prominent Black couple, cared for Anne in their home along with their own five children. In the Dixie household, Anne didn’t have any responsibilities, including chores or school, unlike the Dixie children, who attended school daily and completed household chores. Anne’s mother remained dedicated to her and believed that local schools were not beneficial for her.

With all the freedom that Anne was given, she was able to discover her love for poetry and had time to develop her skills through the solitude she found in the Dixie’s outhouse, the only private place that she had. In this outhouse, she would look through the Sears and Roebuck catalog and imagine herself as a reader.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Education

Although Anne’s parents were separated, they remained in contact concerning their daughter. Joel was upset with Sarah’s decision to withhold their daughter from school. He gave her an ultimatum that Anne must attend school or he would take her to live with him. With this in mind, Sarah enrolled her daughter at the Virginia University of Lynchburg (previously known as the Virginia Theological Seminary and College) in 1893 when she was eleven years old.

Despite having no formal education, Anne excelled academically and even delivered the valedictory address when she graduated six years later in 1899. During her school breaks and over the summer, Anne would return to Bramwell. After graduating, she taught school in Elkhorn and Maybeury, West Virginia from 1899 to 1901.

Marriage and family

While attending Virginia Seminary, Spencer met Charles Edward Spencer, a fellow student. The two got married on May 15, 1901, at Dixie’s home and permanently moved to Lynchburg in 1903. Here, they built a home at 1313 Pierce Street and raised three children together, two daughters, Alroy and Bethel, and a son, Chauncey Spencer. Years later, Anne’s children produced ten grandchildren, and she expanded her home to accommodate their frequent visits.

Chauncey continued his mother’s legacy of activism and had a major role in his military service during World War II. Chauncey’s actions and determination led to the formation of the Tuskegee Airmen. He became a noted member of the group at a time when African Americans were refused military service as pilots in the the segregated armed forces.

Before Anne began her career as a writer, she worked at Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, an all-Black local high school. There she worked as a librarian for more than twenty years. The library had a small collection, so she donated books from her own collection to add to its holdings.

. . . . . . . . . .

Books and films by and about Anne Spencer

. . . . . . . . . .

Start of a literary career

Anne Spencer’s literary career began while she was a student in Virginia Seminary. There she wrote her first poem called “The Skeptic,” which is now lost. She continued writing poetry throughout her life and used any scrap of paper she could find to write down her thoughts.

It was some time later that she planned on opening a chapter of the NAACP in Lynchburg. In an effort to do so, she hosted James Weldon Johnson, then the organization’s traveling representative, in her home. It was during this visit that Johnson discovered Anne’s poetry. Her first published poem, “Feast at Shushan,” appeared in the February 1920 issue of The Crisis, the NAACP’s literary magazine. By the time her first poem was published, Anne was forty years old.

The Harlem Renaissance

Many of Anne Spencer’s works were published during the 1920s, in the Harlem Renaissance era. During her lifetime, she published more than thirty poems. Her work was featured in Alain Locke’s famous 1925 anthology, The New Negro: An Interpretation, connecting her to the literary heart of the Harlem Renaissance.

Her poems were also included in The Book of American Negro Poetry, which was edited by James Weldon Johnson, a prominent figure of the Harlem Renaissance. In addition, she earned a spot in the esteemed Norton Anthology of American Poetry for her writing, making her the second African American to be featured in this work.

Themes in Anne Spencer’s work

Anne Spencer’s work drew respect for its exploration of the themes of race, nature, and feminism. Some critics interpret her poem “White Things” to be a comparison of the subjugation endured by the Black race with the destruction of nature.

She maintained a strong belief in individual liberty and freedom to convey and uphold one’s personal ideals. She also displayed strong objections to various beliefs that interfered with her own ideals. In addition, she had a life-long admiration for poets and paid tribute to Chatterton, Shelley, and Keats in her poem, “Dunbar.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Anne Spencer’s home in Lynchburg, Virginia

. . . . . . . . . .

Awards and honors

In 2016, the Library of Virginia and Dominion Power honored Anne Spencer as one of their Strong Men and Women in Virginia History.

The home in Lynchburg where she resided and worked is now a museum, known as the Anne Spencer House and Garden Museum. The museum is dedicated to preserving the beloved poet’s legacy and connection to the Harlem Renaissance.

Her papers and books from her library are at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia. Some of her correspondence with James Weldon Johnson, specifically selected by her, are part of the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection at the Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscripts Library at Yale University.

In 2019, the United States Postal Service announced that Anne Spencer will be featured in a 2020 Forever stamp honoring figures of the Harlem Renaissance.

Legacy of Anne Spencer

Anne Spencer passed away at the age of ninety-three on July 27, 1975. She is buried alongside her husband Edward, who died in 1964, in the family plot at Forest Hill’s Cemetery in Lynchburg.

After her death, much of her work was published in Time’s Unfading Garden: Anne Spencer’s Life and Poetry. She was later featured in Shadowed Dreams: Women’s Poetry of the Harlem Renaissance.

Some of her lost work was found and published by other famous poets in the later half of the twentieth century.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Anne Spencer

Major works (poetry)

The Poems (1977)

Before the Feast at Shushan (1920)

Dunbar (1920)

White Things (1923)

Lady, Lady (1925)

Lines to a Nasturtium: A Lover Muses (1926)

Rime for the Christmas Baby (1927)

Grapes: Still-Life (1929)

Requiem (1931)

Biographies

Anne Spencer : Poet of the Harlem Renaissance by Brucella Jordan (2016)

Half My World: The Garden of Anne Spencer, A History and Guide

by Rebecca T. Frischkorn and Reuben M. Rainey (2003)

More information and sources

Wikipedia

Anne Spencer Museum

Poetry Foundation

Poets.org

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Anne Spencer appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 9, 2019

Books by Zora Neale Hurston: Fiction, Folklore, and More

Zora Neale Hurston (1891 – 1960), the African-American author and anthropologist, was a natural storyteller. Her love of story resulted in an array of novels and short stories as well as collections gathered from the oral traditions of the Black cultures of the American South and the Caribbean. Presented here is a survey of books by Zora Neale Hurston’s — fiction, ethnographical collections, and other writings.

Zora made a name for herself during the Harlem Renaissance movement of the 1920s, when she began producing novels, short stories, plays, essays, and a modest output of poetry. Upon graduating from Barnard College in 1928, she embarked on a parallel career as an anthropologist.

Though her literary works sold fairly well and gained many admirers, they had their share of detractors. Some Black writers objected to her use of dialect. Other contemporaries were troubled by her political conservatism.

Today, it may be surprising to learn that in the course of her lifetime, Zora’s reputation began to decline. By the time she died in 1960, forgotten and alone, most of her works were out of print. Fortunately for contemporary readers, that situation has been remedied. Her work is now back in print, readily available, and widely studied.

. . . . . . . . . .

Jonah’s Gourd Vine (1934)

Jonah’s Gourd Vine was Zora’s first novel, published in 1934. It’s the story of a Black plantation worker, John Buddy Pearson, who aspires to be a preacher. Once he achieves his goal, he devotes Sundays to giving powerful sermons, and the rest of the week, he indulges in extramarital dallying with the women of his congregation. According to the publisher of the edition reissued in 2008:

“In this sympathetic portrait of a man and his community, Zora Neale Hurston shows that faith, tolerance, and good intentions cannot resolve the tension between the spiritual and the physical. That she makes this age-old dilemma come so alive is a tribute to her understanding of the vagaries of human nature.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Mules and Men (1935)

Mules and Men is an ethnographical collection of stories in the oral tradition that Zora collected on two trips — one in Florida, including Eatonville (the town in which she was raised) and Polk County, and the other in New Orleans. In Florida, she documented some seventy folktales, while in New Orleans, she documented voodoo traditions and other stories. In The Journal of American Folklore (summer, 1996), Susan Meisenhelder wrote of this book:

“While Mules and Men seems (and was, in fact, read by most of her contemporary reviewers as) a straightforward depiction of the humor and “exoticism” of African American folk culture, Zora Neale Hurston carefully arranged her folktales and meticulously delineated the contexts in which they were narrated to reveal complex relationships between race and gender in Black life.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937)

Their Eyes Were Watching God Zora’s third published book and second novel is her best-known work, and has become something of a feminist classic. Janie, the story’s heroine, searches for independence, identity, love, and happiness over the course of twenty-five years and several relationships. This story is not unlike Zora’s own, though it could be argued that she never found true happiness.

Though always somewhat controversial, the book was generally well-received upon initial publication. A 1937 review stated:

“Their Eyes Were Watching God is a moving story, told with humor and great understanding. Miss Hurston has a sense of the dramatic which lifts and speeds her novel. There is a tendency to write preciously and with an intoxication with words, both of which tend to clutter a bit the simple story. On the other hand there is skillful writing and really magnificently handled dialog.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Tell My Horse (1938)

Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica (1938) is based on Zora’s firsthand research of Voodoo practices in Haiti and Jamaica. In 1936, Zora received a Guggenheim fellowship, which allowed her to delve even more deeply into her research. She traveled to Jamaica and Haiti to collect stories and collecting material on African rituals and voodoo. Her research resulted in two nonfiction collections about the culture and language of the people she researched — Mules and Men (1935), and this one.

For these collections, Zora traveled to Jamaica and Haiti. While in the two island nations in the late thirties, Zora participated as an initiate, not just an observer. Tell My Horse peers into the mysteries of Voodoo and paints a unique portrait of its rituals, beliefs, ceremonies, customs, and superstitions.

. . . . . . . . . .

Moses, Man of the Mountain (1939)

Moses, Man of the Mountain demonstrates Zora’s strength as a writer through character development and use of narration. This novel tells the story of Moses and the Book of Exodus from an African-American perspective. The Zora Neale Hurston Digital archive describes the book:

“Moses, Man of the Mountain is Zora Neale Hurston’s attempt at re-writing (or re-righting) the Bible from an Afro-American perspective. She retells the story of the Exodus, which is the triumphant tale of Moses and the Israelites’ escape from Egyptian slavery.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Dust Tracks on a Road (1942)

Dust Tracks on a Road, Zora’s 1942 autobiography, has confounded readers and scholars since its publication. Some critics have even argued that this book might have damaged her reputation. Is it a true memoir or partially apocryphal? Was the story of her life, as she told it, impressionistic rather than realistic? In her foreword to the 2006 edition, Maya Angelou wrote:

“Zora Neale Hurston chose to write her own version of life in Dust Tracks on a Road. Through her imagery one soon learns that the author was born to roam, to listen, and to tell a variety of stories …

In this autobiography, Hurston describes herself as obstinate, intelligent, and pugnacious. the story she tells of her life could never have been told believably by a non-Black American, and the details even in her own hands and words offer enough confusions, contusions, and contradictions to confound even the most sympathetic researcher.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Seraph on the Suwanee (1948)

Seraph on the Suwanee, Zora’s last full-length work of fiction, featuring white main characters — a departure for her. It has not been well received by African-American critics. From the publisher of the 2008 edition:

“Alive with the same passion and understanding of the human heart that made Their Eyes Were Watching God a classic, Hurston’s Seraph on the Suwanee masterfully explores the evolution of a marriage and the conflicting desires of an unforgettable young woman in search of herself and her place in the world.

Hurston explores new territory with her novel Seraph on the Suwanee, a story of two people at once deeply in love and deeply at odds, set among the community of ‘Florida Crackers’ at the turn of the twentieth century. Full of insights into the nature of love, attraction, faith, and loyalty.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Posthumous collections

I Love Myself When I Am Laughing … (1979)

I Love Myself: When I am Laughing … and Then Again When I am Looking Mean and Impressive is an anthology of Zora Neale Hurston‘s work, including essays as well as portions of her novels and memoirs. This collection demonstrates how fortunate it is for new generations of readers that Alice Walker (who served as its editor) revived Zora’s work and reputation.

It pays tribute to Hurston’s role in black literature of the early twentieth century, including famous essays like “How it Feels to Be Colored Me” and “Crazy for This Democracy;” full short stories like “The Gilded Six-Bits;” and portions from her autobiography Dust Tracks on a Road, as well as her ethnographic studies, notably Tell My Horse. This collection is a nice introduction for those just starting to gain an appreciation of Zora Neale Hurston.

. . . . . . . . . .

Every Tongue Got to Confess (2001)

Every Tongue Got to Confess collects a selection of Zora’s ethnographic writings. According to the publisher of this 2001 publication:

“These hilarious, bittersweet, often saucy folk-tales — some of which date back to the Civil War — provide a fascinating, verdant slice of African-American Life in the rural South at the turn of the twentieth century. Arranged according to subject — from God Tales, Preacher Tales, and Devil Tales to Heaven Tales — they reveal attitudes about slavery, faith, race relations, family, and romance that have been passed on for generations. They capture the heart and soul of the vital, independent, and creative community that so inspired Zora Neale Hurston.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Barracoon (2018)

Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” caused quite a bit of literary excitement when it was published for the very first time in 2018. From the publisher: “In 1927, Zora Neale Hurston traveled to Plateau, Alabama, to visit eighty-six-year-old Cudjo Lewis, a survivor of the Clotilda the last slaver known to have made the transatlantic journey. Illegally brought to the United States, Cudjo was enslaved fifty years after the slave trade was outlawed.

Barracoon employs Hurston’s skills as both an anthropologist and a writer, and brings to life Cudjo’s singular voice, in his vernacular, in a poignant, powerful tribute to the disremembered and the unaccounted. This profound work is an invaluable contribution to our history and culture.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Hitting a Straight Lick With a Crooked Stick (2020)

Hitting a Straight Lick With a Crooked Stick, a newly discovered collection of Zora’s works, will surely be as much cause for excitement as was the discovery of Barracoon. From the publisher:

“Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick is an outstanding collection of stories about love and migration, gender and class, racism and sexism that proudly reflect African American folk culture. Brought together for the first time in one volume, they include eight of Hurston’s ‘lost’ Harlem stories, which were found in forgotten periodicals and archives.

These stories challenge conceptions of Hurston as an author of rural fiction and include gems that flash with her biting, satiric humor, as well as more serious tales reflective of the cultural currents of Hurston’s world. All are timeless classics that enrich our understanding and appreciation of this exceptional writer’s voice and her contributions to America’s literary traditions.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Short Stories by Zora Neale Hurston

Some of Zora’s short stories have become well known and are still read and studied. They were collected in The Complete Stories in 2008. A few that are covered here on Literary Ladies:

“Spunk” (full text; 1925)

“Sweat” (1926; read an analysis here )

“The Gilded Six-Bits” (1933; read an analysis here )

. . . . . . . . . .

Books by Zora Neale Hurston on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Books by Zora Neale Hurston: Fiction, Folklore, and More appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 5, 2019

Candace Wheeler, American Design Trailblazer

Despite having published seven books in her long lifetime, Candace Wheeler (1827–1923) might not be classified as a “literary lady,” let alone a classic author. She was one of the first American women to practice as an interior and textile designer, and opened the profession to other women who followed in her footsteps.

Born Candace Thurber, her father was a Puritan abolitionist so severe that he would not allow the family to use sugar or cotton, and he applied similarly stringent standards to his children’s reading habits, decreeing that they read nothing more fanciful than the Bible and Pilgrim’s Progress.

Yet, she evolved into a superlative aestheticist and the godmother of many female artists, writers, and designers. Often referred to as “the mother of interior design,” she was the actual mother of the accomplished artist and book illustrator Dora Wheeler Keith.

Moving away from Puritan traditionalism

The tension between the traditionalism of Wheeler’s Puritan upbringing and her inarguably glittering artistic career was not uncommon in the biographies of many of the educated, accomplished, and socially conscious ladies of the 19th century. A contemporary feminist may have difficulty with Wheeler’s continued stress on her obedience to her husband, as she solicited his permission for every step in a career that was extraordinary in its independent feminism.

Her husband, Thomas Wheeler, a self-made financier, is not an unappealing figure, albeit a bit of a cipher in comparison to his vivid wife. Perhaps the most telling anecdote about him is his comment when he bought a townhouse as a home for his wife’s newly formed Associated Artists, an independent corporation of female artists:

“Well, at least that will make it up to her for not having the vote.” Mr. Wheeler did not live long enough to see women’s suffrage passed, but Candace did.

Indeed, the first twenty-five years of Candace Wheeler’s marriage offered little suggestion that she would prove to be anything other than a conventional, if socially and culturally well-connected, wife and mother.

Early years in New York society

Her early life in New York City reads like a name-check of anyone in the arts, finance, or politics of early 19th-century American society: The Coopers (of Cooperstown, the Cooper Union and Natty Bumppo fame), James Russell Lowell, and Charlotte Cushman, the celebrated Shakespearean, are just a few of those casually mentioned in Wheeler’s social notes.

But what can feel like Knickerbockian name-checking is also a good reminder of how small a world New York, and with it, America, was in the 1840s. Everybody who was anybody really did know everybody. Even when the Wheelers departed for an extended stay in Europe just after the Civil War, the same circle was there to greet them and perform the appropriate introductions.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A turning point, post-Civil War

Although Wheeler never states it explicitly, the American Civil War and the numerous genteel widows it left behind, seems to mark the turning point in Wheeler’s life. Inspired by the unfortunately-named English Society for Decayed Gentlewomen, she immediately joined forces with several other charitably-minded society ladies to adopt its purposes to the aftermath of the war in America – though she wisely chose to change the name to the Society of Decorative Arts.

Following the model of the British society, which had been championed by such titans of Arts and Crafts movement as the illustrator Walter Crane, Wheeler’s newly-formed Society provided instruction, easily reproducible patterns, and remunerative outlets for handiwork such as embroidery and china painting, which were the few skills possessed by impoverished widows and spinsters – including the Society’s first paid secretary, Elizabeth Custer, the General’s widow.

Two years later, Mrs. Choate, a more forward-thinking philanthropist, invited Wheeler to turn her efforts into the Women’s Exchanges, an organization that similarly encouraged and marketed working women’s domestic skills, such as cooking, baking, sewing, and knitting. (The Women’s Exchanges are an extremely worthy organization that exists to this day. Don’t believe me? Check them out at Federation of Women’s Exchanges or visit the location where I bought handcrafted dollhouse furniture that I could afford when I was at kid at Brooklyn Women’s Exchange.

Choate persuaded Wheeler to transfer her allegiance to the working women’s organization, a move seen as a betrayal by such Board members of the Society for Decorative Arts as Mrs. J. J. Astor (for surely, neither the skills nor the female artisans of such different classes could be expected to rub elbows comfortably).

Becoming a professional practitioner

The year of Wheeler’s resignation from the Board of the Society of Decorative Arts, 1879, was also the year that marked Wheeler’s transformation from patron of the decorative arts to professional practitioner, when she was invited by Louis Comfort Tiffany to join him as an equal partner in the decorating firm that bore both their names (an agreement that was once again subject to her husband’s approval).

The partnership won such commissions as the curtain for the Madison Square Theatre, the Seventh Regiment Armory, and the Union League Club. Wheeler’s association with Tiffany lasted until 1883 when she formed her own textile firm, Associated Artists, which involved only women – and occasioned her tolerant husband’s philosophical observation on suffrage when he purchased the townhouse on 23rd street to house her fledgling company.

. . . . . . . . . .

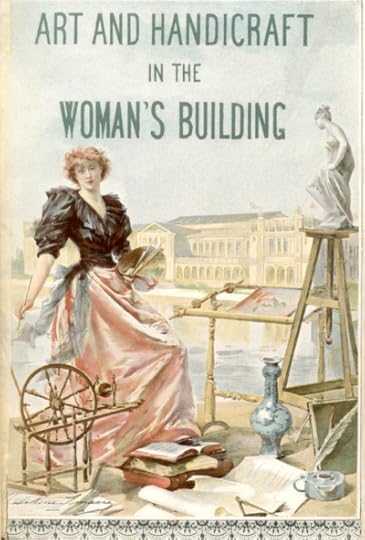

Chicago World’s Fair Women’s Building-Lemaire poster, 1893

. . . . . . . . . .

The Women’s Pavilion at the Chicago World’s Fair

Perhaps the culmination of Candace Wheeler’s career was her being invited, at what was then an advanced age of 66, to take charge of interior design the Women’s Pavilion at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, as well as organizing the State of New York’s applied arts exhibition there.

The building, designed by architect Sophia Hayden, was filled with exhibitions of women’s fine arts, crafts, industrial products and regional and ethnic specialties from around the world. The Central Hall featured busts of notable women from history – many of them carved by women.

1893 Chicago World’s Fair Women’s Building-(closeup) designed by Sophia Hayden

Wheeler’s interior featured murals commemorating the progress of women by such renowned female artists as Mary Cassatt, as well as a ceiling designed Wheeler’s own daughter, the talented artist Dora Wheeler (Keith). Alas, many of these murals have vanished, although some pictures of them remain.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Onteora Colony in recent times

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Onteora Arts Colony

Arguably no less spectacular – and equally quixotic – an endeavor was Wheeler’s Onteora, an arts colony located in the Catskills that hosted such luminaries as Mary Mapes Dodge, Mark Twain, and Maude Adams, the American actress for whom the role of Peter Pan was written by J.M. Barrie.

In her Annals of Onteora, Wheeler describes how she and her brother selected the site based purely on the artistic vista – despite the local farmers’ queries whether they wouldn’t like to look at the water supplies first. It is an amusingly self-deprecating anecdote; however, Wheeler’s description of her relationship with these self-same Onteora locals reminds us of how careful we must be when attempting to judge the attitudes of the past by our own standards.

Evident classism, yet unexpected tolerance

Her classism is evident, even when she is describing her neighbors with admiration. And her memoir admittedly contains (mercifully very few) outright racist passages that contrast the eagerness to please of recently emancipated Southern black workers against the attitudes of the recalcitrant Northern workers who insist on being paid what they’re worth.

Several of Wheeler’s comments about living in Brooklyn also contain off-handed descriptions of the “Irish type” or the “German type” that were polluting the classical “American profile” – as if such a thing could logically exist.

On the other hand, within their narrow social circle, Wheeler’s views could be unexpectedly tolerant. Charlotte Cushman, “America’s greatest living tragic actress,” was renowned for her breeches roles and for having served as the model for the female sculptor Emma Stebbins’ The Angel of the Waters atop the Bethesda Fountain in Central Park. She also had openly tempestuous relationships with a series of other female artists (at least one of which led to a court case), but was still casually accepted as a member of the Hunt Club – as well as received at the White House by Abraham Lincoln.

. . . . . . . . . .

Books by and about Candace Wheeler on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

A balance between conventionality and rebellion

Candace Wheeler’s career and feminism strike a similar balance between the conventions enforced by her upbringing and her social station and a strong woman forging a rebellious path in a world whose restrictiveness modern American woman can hardly imagine. What’s fascinating about Wheeler is how she triumphed by turning those restrictions to her advantage. Every aspect of her career path is rooted in appropriate domesticity, from designing textiles to decorating the women’s pavilion.

Similarly, the Society of Decorative Arts and the Women’s Exchanges sought not to break the barriers preventing them from participating in “men’s work,” but instead championed the value of that domestic work which was considered to be women’s “natural sphere.”

There is much about Candace Wheeler’s career that can seem alien to those of us schooled to look for “kick-ass,” “bad-ass” heroines. But a respectful consideration of her accomplishments also shows us how genuinely “rad” a woman can be, even as she played completely by the rules.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Erica Obey. Erica is the author of The Horseman’s Word, as well as three other historical and paranormal novels, including the award-winning The Curse of the Braddock Brides, which Publishers Weekly called a “smoothly unfolding, satisfyingly twisty tale of lurid legends, deadly blackmail, hidden identities, international spycraft, and practical romance.” See the Erica Obey page on Amazon*.

She holds a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature and pursued an academic career specializing in the women folklorists of the nineteenth century, before she decided she’d rather be writing the stories herself. There are three places you can find Erica when she’s not writing: on a hiking trail, in her garden, or taking tea at a nearby stately home – all in the name of research, of course! Visit her at Erica Obey.

. . . . . . . . . .

1893 Chicago World’s Fair Women’s Pavilion:

Officers of Board of Lady Managers

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Candace Wheeler, American Design Trailblazer appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 4, 2019

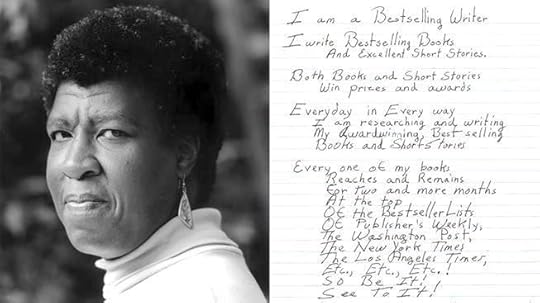

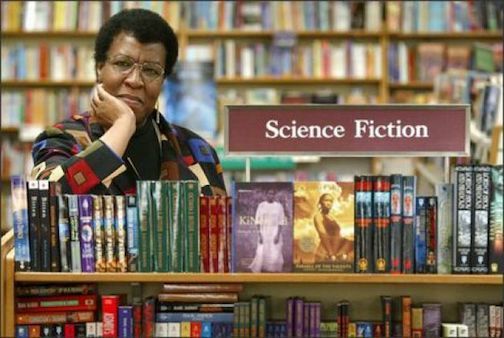

Octavia Butler’s Rules for Writers: Wisdom for Every Stage of Practice

Octavia E. Butler (1947 – 2006), the esteemed American author of science fiction broke ground in the white male-dominated world of science fiction. She was not only one of the first successful women writing in the genre, but one of the first African-American to break through at a time when precious few black science fiction writers were being published. Here we’ll explore Octavia Butler’s rules for writers, with wisdom for every wordsmith no matter where you are on the journey.

To succeed in a the genre of sci-fi, where she would have to blaze her own trail, Butler was rigorously self-disciplined in her writing practice. She stuck to a strict schedule, sometimes rising at 2:00 am to write for several hours before heading out to whatever odd job she held int the days before becoming a full-time author.

A true introvert, whatever external encouragement she may have lacked, Butler gave to herself. In her notebook, she wrote: “I shall be a bestselling writer. I will find the way to do this. So be it! See to it!”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

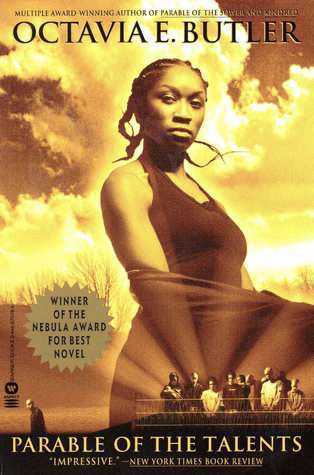

Kindred (1979) was the book that cemented literary reputation. It tells the story of Dana, a contemporary African-American woman who travels back in time to save an ancestor who happens to be a white slave owner. By saving him in his time, she ensures her own survival in the future.

Other highly-regarded books by Butler include the Xenogenesis trilogy — Dawn (1987), Adulthood Rites,(1988), and Imago (1989). The two-part Parable series — Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998) are also among her best-known works. She is credited as one of those who inspired the Afro-futurism movement.

For Octavia Butler, science fiction wasn’t merely a vehicle for escaping into fantasy, but a means to explore universal issues that face humanity. Her deep and abiding interest in and observation of human nature within dystopian or fantastical realms — is what makes her work so compelling. She’s a natural storyteller as well, as evidenced by her tightly plotted page-turning novels.

Butler’s New York Times obituary, described her as “an internationally acclaimed science fiction writer whose evocative, often troubling novels explore far-reaching issues of race, sex, power, and ultimately, what it meant to be human.”

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like: Octavia Butler Quotes on Writing and Human Nature

. . . . . . . . . .

And now, let’s get to Octavia E. Butler’s rules for writers, 9 of them — adapted and condensed from “Furor Scribendi,” an essay that appeared in Bloodchild and Other Stories. Here they are, in her own words:

Writing for publication may be both the easiest and the hardest thing you’ll ever do. Learning the rules — if they can be called rules — is the easy part. Following them, turning them into regular habits, is an ongoing struggle. Here are the rules:

Read. Read about the art, the craft, and the business of writing. Read kind of work you’d like to write. Read good literature and bad, Fiction and fact. Read every day and learn from what you read. If you commute to work or if you spent part of your day doing relatively mindless work, listening to books on tape.

Take classes and go to writers’ workshops. Writing is communication. You need other people to let you know whether you’re communicating what you think you are and whether you’re doing it in ways that are not only accessible and entertaining, what as you can make them … Learn from the comments, questions, and suggestions of both the teacher and the class. Please relatives strangers are more likely to tell you the truth about your work than are your friends and family who may not want to hurt or offended you.

Write. Write every day. Right what do you feel like writing or not. Choose a time of day. Perhaps you can get up an hour earlier, stay up an hour later, give up an hour of recreation, or even give up your lunch hour. If you can’t think of anything in your chosen genre, keep a journal. You should be keeping one anyway Journal writing helps you to be more observant of your world, and the journal is a good place to store story ideas for later projects..

Revise your writing until it’s as good as you can make it. All the reading, writing, and classes should help you do this check your writing, your research (never neglect your research), in the physical appearance of your manuscript. Let nothing substandard slip through.

Submit your work for publication. First research the markets that interest you. Seek out and study the books or magazines of publishers to whom you want to sell. Then submit your work. If the idea of doing this scares you, fine. Go ahead and be afraid. But send your work out anyway. If it’s rejected, send it out again, and again. Rejections are painful, but inevitable. They’re very writer’s rite of passage.

Forget inspiration. Habit is more dependable. Have it will sustain you whether you’re inspired or not. Have it will hope you finish and polish your stories. Inspiration won’t. Habit is persistence and practice.

Forget talent. If you have it, fine. Use it. If you don’t have it, it doesn’t matter. As habit is more dependable than inspiration, continue learning is more dependable than talent. Never let pride or laziness prevent you from learning, improving your work, changing its direction when necessary. Persistence is essential to any writer — the persistence to finish your work, to keep writing in spite of rejection, to keep reading, studying, submitting work for sale.

Finally, don’t worry about imagination. You have all the imagination you need, and all the reading, journaling writing, and learning you will be doing stimulated. Play with your ideas. Have fun with them. Don’t worry about being silly or outrageous or wrong.

Persist.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Octavia Butler page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Octavia Butler’s Rules for Writers: Wisdom for Every Stage of Practice appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 3, 2019

Margaret Ayer Barnes

Margaret Ayer Barnes (April 8, 1886 – October 25, 1967) was an American novelist, playwright, short-story writer, best known for her Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Years of Grace (1930).

Born and raised in Chicago, Illinois, Margaret Ayer was the youngest of four siblings. From an early age, she was quite competitive and regularly had debates with her two older brothers and sisters. Intelligent and curious, she had an interest in theater and was an avid reader.

These interests led her to befriend Edward Sheldon, a playwright who would later encourage her to become a writer. Margaret and Sheldon had much in common and enjoyed discussing the literary merits of plays. Years later, Sheldon went on to begin his playwriting career in New York. The two remained friends and would later reconnect as Barnes began her literary career.

Education and family life

Margaret attended the Pennsylvania campus of Bryn Mawr College and was an outstanding member of her class. She graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in English and Philosophy in 1907. During her years at Bryn Mawr College, she was inspired to write about contemporary feminism due to a challenge from Carey Thomas.

Three years after receiving her first degree, she married Cecil Barnes, a prominent Chicago attorney, on May 21, 1910. The couple had three sons, Cecil Jr., Edward Larrabee, and Benjamin Ayer. Even as a mother and wife, she never let her domestic responsibilities take over her life.

When her sons grew up and attended boarding school, and later Harvard, she took up outdoor activities, including swimming and hiking. She also became more involved with theater.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Returning to Bryn Mawr College

Margaret returned to Bryn Mawr College in 1920, this time to work, serving as alumnae director for three years. The position led to numerous speaking opportunities, and she used her platform in part to help organize the Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers in Industry.

The school served as an alternative educational program for women workers and mainly served young, single, immigrant women with little to no educational background. The program, which offered courses in progressive education, liberal arts, and economics, helped build women’s confidence as speakers, writers, and leaders in the workplace.

. . . . . . . . . .

Margaret Ayer Barnes page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

Stepping into theater while recovering from injury

In 1926, at the age of forty, Margaret’s life changed irrevocably. While vacationing in France, she was a passenger in a limousine that collided head-on with another car. She suffered a fractured skull, back, and three ribs.

Doctors predicted that she would be bedridden for the remainder of her life due to the multiple injuries, but she fought to resume the life she feared she may have lost. To keep herself occupied as she was healing, she started writing and developed a special interest in short stories.

While enduring a painful path to recovery, Margaret and Edward Sheldon’s paths crossed again. By this time, he was completely disabled with arthritis and on the brink of losing his eyesight. He still believed in her. With the encouragement of her long-time friend, she realized her passion for theater and playwriting. They worked as a team to dramatize Edith Wharton’s novel The Age of Innocence (1920). The play was an instant success after it was produced in 1928.

Between the years of 1926 and 1930, she created many short stories and three plays. Together with Sheldon, she worked on a comedy titled Jenny and Dishonored Lady. The Age of Innocence and Jenny were performed more than a hundred times on Broadway, but Dishonored Lady was never staged.

Lawsuit against MGM

That same year, there was a lawsuit against Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for copyright infringement. The lawsuit claimed that the script MGM used for the motion picture Letty Lynton (1932) plagiarized material from the play Dishonored Lady by Edward Sheldon and Barnes.

Seven years later, the lawsuit was settled favorably for Barnes and Sheldon. As a result of the lawsuit, the film has remained unavailable.

. . . . . . . . . .

1947 movie poster for Dishonored Lady

. . . . . . . . . .

Themes in Margaret Ayer Barnes’ works

Margaret used a fictional approach to potray the social history of the upper-middle class during the Spanish-American War through the Great Depression. She illustrated places and people with great accuracy and tended towards conservative beliefs.

Years of Grace (1930) is a novel that reflects her views on economics. It allows readers to admire the benefits of having lived a dull, secure life and meeting old age with a sufficient money in the bank account and a beautifully furnished home. William J. Stuckey argued that it’s difficult to view Margaret Ayer Barnes as someone who pushes for conservatism when she writes on themes of feminism in all of her fiction works.

In 1931, she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Years of Grace.

Film adaptations

Westward Passage (1931) was made into a 1932 movie of the same name.

Margaret Ayer Barnes’ 1928 dramatization of Edith Wharton’s beloved novel, The Age of Innocence, was made into a 1934 movie.

Her novel, Edna, His Wife (1935), was adapted into a play by American author and actress Cornelia Otis Skinner in 1937.

Her 1930 play written with Sheldon, Dishonored Lady, was made into a 1947 movie starring Hedy Lamarr, released by United Artists.

Legacy of Margaret Ayer Barnes

Margaret Ayer Barnes received an honorary degree in Doctor of Letters from Oglethorpe University in 1936.

She spent the remainder of her life in Cambridge, Massachusetts and died there on October 26, 1967. She once said that “the story of a life may be poignantly told in five thousand words, if the proper facts emphasized and suppressed.”

Her son, Edward Larrabee Barnes (1915–2004) is remembered as a noted architect. Her older sister, Janet Ayer Fairbank (1878–1951), was a suffragette, a member of militant women’s organizations in the early twentieth century who fought for the right to vote in public elections. A niece, Janet Fairbank (1903–1947), was a well-known operatic singer.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Margaret Ayer Barnes

Major works

Prevailing Winds (1928)

Jenny (1929)

Dishonored Lady (1930)

Years of Grace (1930)

Westward Passage (1931)

Within This Present (1933)

Edna, His Wife (1935)

Wisdom’s Gate (1938)

Biographies

Margaret Ayer Barnes by Lloyd C. Taylor, Jr. (1974)

The Essential Writer’s Guide : Spotlight on Margaret Ayer Barnes,

Including Her Education, Personal Life, Analysis of Her Best Sellers … by Gaby Alez (2012)

More information and sources

Wikipedia

Pennsylvania Center for the Book

Reader discussion of Barnes’ works on Goodreads

Enacademic

Margaret Ayer Barnes papers at Bryn Mawr College

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Margaret Ayer Barnes appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 31, 2019

Drinking from the Spring: On Rereading Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt

The last day of October marks Samhain, the end of harvest season and the beginning of winter. This Gaelic festival opens the door to the darker part of the year, and it’s also the anniversary of author Natalie Babbitt’s death in 2016. What better time to consider Babbitt’s remarkable novel about mortality, Tuck Everlasting (1975), a story that rewards young and adult readers alike.

When I first reread Tuck, I was in my thirties. It was never one of my school texts: when I was a girl, it hadn’t yet achieved its iconic status. But the timing for me to rediscover this story, about how “dying’s part of the wheel, right there next to being born” was perfect.

I returned to it when I was staying with an older relative who was living with a terminal disease. Most of the care-giving duties fell to more experienced family members, but between more demanding weeks filled with appointments and treatments, I moved into the spare bedroom and managed the household shopping and chores.

Removed from my everyday life, I had a lot of time to read; I visited the public library nearly every day, browsing the adult fiction but borrowing favorite children’s stories. For entertainment. And for comfort. One of these was Tuck.

Literature and unanswerable questions

I had no idea that, when Tuck Everlasting was new, Michele Landsberg had heralded Babbitt’s explanation of death as “one of the most vivid and deeply felt passages in American children’s literature.”

I suspect an editor believed it was accurate to specify ‘children’s’ literature, but Babbitt herself believed that the best stories were the ones “with unanswerable questions remaining unanswered, retaining their mystery and their wonder,” and that these questions existed for all human beings.

The novel grew directly out of a question, in fact. Babbitt describes the origins of the story in an interview celebrating the 40th anniversary of Tuck Everlasting, with NPR’s Melissa Block for All Things Considered:

“Well, it’s not entirely a kids’ book. But it came into my mind — I have three children and my youngest is my daughter. One day she had trouble sleeping, woke up crying from a nap. And we looked into it together, as well as you can with a 4-year-old, and she was very scared with the idea of dying. And it seemed to me that that was the kind of thing you could be scared of for the rest of your life, and so I wanted to make sure that she would understand what it was more. And it seemed to me that I could write a story about how it’s something that everybody has to do and it’s not a bad thing.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Tuck Everlasting was adapted into a 2002 film

. . . . . . . . . . .

Fiction, reality, and mythology

Everything in the story “comes from actually living it,” Babbitt explains in a 2015 interview with Publishers Weekly. While their children were young, the family spent weekends and holidays near Forestport, on a “little house on a pond” in the Adirondacks of upper New York state.

The house serves as the cover image for Tuck Everlasting and even small details, like the mouse in the drawer, were drawn from her family’s experiences there.

There was, however, another significant influence on her writing. In 1972, Babbitt read The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) by Joseph Campbell, which she considered a “densely scholarly work.” (And so influential that she returned to it in later years as well.) She observes the impact of its psychological and mythological content in the archetypes of Tuck’s babbling spring, dark forest, great tree, and herald/carrier toad.

She later specifically outlines the archetypal roles of two female characters in a 2000 interview with Betsy Hearne in Horn Book Magazine, how the older one, Mae, is an “ancient kind of heroine” — “an Earth Mother figure if there ever was one, while the younger, Winnie, is a “new kind of heroine,” and how Mae is “protecting Winnie, her young, but she’s also protecting the young of the world.”

How Tuck Everlasting begins

The novel begins slowly, with the kind of sentences that I can imagine having skipped as an impatient young reader. The kind of sentences I love as an adult. Since that first rereading, I’ve reread this book several times in high summer. In every encounter, Tuck’s opening passage pleases me anew: “The first week in August hangs at the very top of summer, the top of the live-long year, like the highest seat of a Ferris wheel when it pauses in its turning.”

Babbitt recognizes, however, that the opening does not suit every reader. She describes to Hearne the elements of the writing process that complicate readers’ immersion into the story:

“One of the reasons why it takes so long to get into the story is that Tuck has three first chapters. I would start and I would be going along and then I would think, ‘Well no, you have to say something before you come to this,’ so I’d put another chapter at the beginning of that one. Kids are troubled by this; they think it starts very slowly, and for them I think it does. In my generation we are quite used to books that take you gradually into themselves.”

Writing about dilemmas (spoiler alert!)

Not only is there more than one entry point into a complex subject, but Babbitt is drawn to the challenge of writing about dilemmas. Some of these are resolved more quickly than others, as illustrated in the passage below.

Note: The resolution of one of these dilemmas is promptly revealed in Babbitt’s remark so, if you prefer to avoid plot spoilers, jump to the “Writing and editing” heading and resume reading.

When students wrote to Babbitt about plot points, some dilemmas are debated and others are flatly accepted:

“Curiously, no child has ever written to me about whether or not Mae Tuck should have killed the man in the yellow suit. They always write about whether or not Winnie Foster should have drunk the spring water and gone off with the fascinating Jess Tuck. They seem to feel that the man in the yellow suit, like the Wicked Witch of the West, needed killing, and so it’s all right.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Natalie Babbitt

. . . . . . . . . .

Telling truthful stories

Willing acceptance on the part of readers does not necessarily align with a writer’s sense of purpose but, in this case, Babbitt saw no alternative. She viewed this plot point as inevitable and truthful:

“I don’t like violence in any form, but I got right up to the point when the man in the yellow suit was dragging Winnie Foster away, and I knew what I would have done if I’d been Mae Tuck.

I knew that if someone had broken into my house and had tried to drag one of my children away, I’d have grabbed anything that came to hand and bashed him as hard as I could. I wouldn’t have paused to think it over. And neither would any other female, two legs or four, in all of the natural world. This is the simple truth. And when you write it for children, the truth is vital.”

Babbitt’s commitment to truth-telling is admirable. She was fortunate to find support and encouragement in her editorial partnership with Michael di Capua, with whom she worked on her first publication and continued to work throughout her career.

On writing and editing Tuck Everlasting

Di Capua did not view the quality of Babbitt’s work in Tuck any differently from her other work. It was “the same old, same old: yet another brilliant performance from her.”

In terms of her writing process, Babbitt did not view Tuck any differently either. It was consistent with her established process as she describes it to Hearne, and she, in turn, compliments di Capua’s editorial performance:

“As far as drafts are concerned, the way I’ve always worked is different from some of my colleagues who go from A all the way to Z and then start all over again to do their rewriting. That’s a perfectly good way, but I rewrite each sentence when I come to it until it’s just the way I want it. So in that sense Tuck didn’t take any longer to write than any of my other books, about a year–nine months to a year, something like that. My editor, Michael di Capua, did some editing on it, but he did more boosting than anything else. He’s very good at that.”

Di Capua did, however, recognize one key difference with this work of Babbitt’s: that “the theme of Tuck – ‘would eternal life be a good thing?’ – was a much grander theme than those of her previous books.”

. . . . . . . . . . .