Nava Atlas's Blog, page 59

February 11, 2020

Ariel by Sylvia Plath — a review and analysis

Ariel was the second published collection by Sylvia Plath (1932 – 1963). It came out two years after she took her own life at age thirty. Following is an analysis of Ariel by Sylvia Plath as well as a review, both from 1965, the year in which it was first published.

Plath’s poetry, considered part of the “confessional movement,” was influenced by Robert Lowell as well as by her friend, the poet Anne Sexton, who also explored dark themes and death in her work (and who, like Plath, committed suicide). Depression had been a constant companion, leading to a life of struggle that was reflected in her work.

Once Plath started to publish, her star quickly rose in the world of poetry. Her first collection, The Colossus, was published in 1960. Its poems were intense, personal, and delicately crafted. In Ariel, the beauty of craft remains even as it reveals the fissures growing in the poet’s psyche. According to the Penguin Companion to American Literature:

“The Colossus (1960) and the posthumous Ariel (1965) show a remarkable development. The first is a largely personal poetry, intense and delicately rendered, usually dealing with the relationship of the poet and a perceived object from which she seeks illumination, ‘that rare, random descent.’

It is controlled, serious verse but her later work shows new strains and pressures at work and becomes a poetry of anguished confession.”

The 1965 edition revealed the heavy hand of Ted Hughes. He had omitted twelve poems that Plath had earmarked for the collection, and included twelve others of his own choosing. In 2004, a restored edition of Ariel was published.

Following are two reviews of Ariel from 1965, the first of which is by A. Alvarez, a longtime champion of Plath and her poetry, and a poet in his own right.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Sylvia Plath

. . . . . . . . . . .

Poetry in Extremis — an analysis of Ariel

From the original review in The Observer, March 14, 1965, written by A. Alvarez: It is over two years now since Sylvia Plath died at the age of thirty, and in that time a myth has been gathering around her work.

It has to do with her extraordinary outburst of creative energy in the months before her death, culminating in the last few weeks when, as she herself wrote, she was at work every morning between four and seven, producing two sometimes three poems a day.

All of these last verses were intensely personal, nearly all were about dying. So when her death finally came it was prepared for and, in some degree, understood.

However wanton it seemed, it was also, in a way, inevitable, even justified, like some final unwritten poem.

The last works were something quite new in poetry. I wrote at the time in The Observer that Plath was “systematically probing that narrow, violent areas between the viable and the impossible, between experience which can be transmuted into poetry and that which is overwhelming.”

In order to tap knowingly the deep reservoirs of feeling that are released usually only in breakdown she was deliberately cutting her way through poetic conventions, shedding her old life, old emotions, old forms. Yet she underwent this process as an artist.

If the poems are despairing, vengeful, and destructive, they are at the same time tender, open, and also unusually clever, sardonic, hard minded:

Dying

Is an art, like everything else.

I do it exceptionally well.

I do it so it feels like hell.

I do it so it feels real.

I guess you could say I’ve a call.

The myth, then, is a diversion from the objective achievement. For the very reason that it has an originality that keeps it apart from any poetic fads. It is too concentrated and detached and ironic for “confessional” verse, with all hat implies of self-indulgent cashing-in on misfortunes; and it is violent without any deliberate exploitation of horrors and petty nastiness.

If these last poems could never have been predicted from her first collection, The Colossus, this is not simply because such a leap is always unforeseeable, but because her earlier absorption with style would, in the the usual order of things, have made it doubly hard for her to bore through the crust of mere craftsmanship and release the lava below.

Technically, the basic difference between the earlier and later poems is that the first were written for the eye, and the last for the ear. They need to be read aloud; they are original because she discovered in them her own speaking voice, her own identity.

So the poems run with an inner rhythm which alters with the pressure of feeling and allows the images, which came crowding in with an incredible fertility and accuracy, to shift into one another, define and modify one another, and rub off colors each on the next.

To take a straightforward example from “The Arrival of the Bee Box”:

I put my eye on the grid.

It is dark, dark.

With the swarm feeling of African hands

Minute and shrunk for export.

Black on black, angrily clambering.

How can I let them out?

It is the noise that appeals me most of all,

The unintelligible syllables.

It is like a Roman mob,

Small, taken one by one, but my god,

together!

I lay my ear to furious Latin,

I am not Caesar.

I have simply ordered a box of maniacs.

They can be sent back.

They can die, I need feed them nothing, I

am the owner.

It starts as simple narrative description; but as “dark” is repeated it is somehow made to reverberate inwardly, crystallizing into a metaphor which voices her underlying sense of threat.

That menace carries over into the next bit of description (of the noise) and shift, though another image, into wry helplessness (“I am not Caesar”); at which point a sense of proportion reasserts itself: “They can die … I am the am the owner.”

So a trivial incident gathers into a whole complicated nexus of feelings about the way her life is getting out of control. It is a brilliant balancing act between colloquial sanity and images which echo down and open up the depths.

Many of the poems are more difficult than that, rawer, more extreme. But all have that combination of exploratory invention, violent, threatened personal involvement and a quizzical edge of detachment. The poems are casual yet concentrated, slangy yet utterly unexpected.

They are works of great artistic purity and despite all the nihilism, great generosity.

Ariel is only a selection from a mass of work Plath left. Some of the other pomes have been printed here and there, some have been recorded, some exist only in manuscript. It is to be hoped that all this remaining verse will soon be published. As it is, this book is a major literary event.

. . . . . . . . . . .

10 of Sylvia Plath’s Best-Loved Poems

. . . . . . . . . . .

A 1965 review of Ariel by Sylvia Plath

From the original review in The Age, Melbourne, Australia, July 10, 1965: Sylvia Plath was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1932. In 1956, while studying on a Fulbright grant, she met and married the poet Ted Hughes. In 1960 her first book of poems appeared, and in 1963, she committed suicide.

The poems written in the last three years of her life have been gathered in a volume titled Ariel.

They are difficult, uncertain poems, some extremely obscure and all primarily dependent on central images. Formal rhythm and the logic of rational statement are both dispensed with, the main principle of organization being a free-association technique.

How does a doomed poetess in her late twenties see death? Sylvia Plath was, in poetry at least, a stubbornly brave young woman, determined to face reality objectively, but at the same time neither to posture nor to cant.

The poems witness to a singularly pure sense of reality, a personality capable of many responses and of sustaining an attitude effectively. At one extreme she celebrates the ritual murder of her subconscious father-image in jangling staccato phrases parodying the clichés of agony column verse, and culminating in a Walpurgisnacht frenzy.

At the other she writes bitterly of her ability to survive:

It’s the theatrical

Comeback in broad day

To the same place, the same face, the same brute

Amused shout:

“A miracle!”

That knocks me out.

Some of her images take on forceful private meanings. Poppies are associated with violence and with the malignant blood cells of hemophilia, the Medusa head with the reality of death, bees with the life of the soul after death.

The last of the is a traditional usage, the other two subjective and personal. Such associations and identifications when they occur are almost always oblique and contribute to the enigmatic texture of the poetry.

Her achievement raises issues concerning the value of literature and its relation to life. The last poem suggests that words are dubious allies in the struggle to maintain a sense of reality. They are solid and fixed and resonant, abut as circumstances alter, they become emptied of meaning.

Years later I

Encounter them on the road —

Words dry and riderless,

The indefatigable hoof-taps

While

From the bottom of the pool, fixed

stars

Govern a life.

Nevertheless, her own work affirms the abiding value of literary creation, for poet and reader alike. It is no mean feat to have recorded an enduring attitude to death that embraces a sense of life in the face of suffering and weakness.

Plath’s poems are a tribute to the resourcefulness of the creative imagination and its capacity to render meaningful the hazardous course of an individual life.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Ariel by Sylvia Plath (the restored edition) on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . . .

More about Ariel by Sylvia Plath

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Sylvia Plath’s Joy (The New Yorker)

A Close Reading of Ariel — The British Library

. . . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Ariel by Sylvia Plath — a review and analysis appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Ariel by Sylvia Plath — a review and analyisis

Ariel was the second published collection by Sylvia Plath (1932 – 1963). It came out two years after she took her own life at age thirty. Depression had been a constant companion, leading to a life of struggle that was reflected in her work. Following is an analysis of Ariel by Sylvia Plath as well as a review, both from 1965, the year in which it was first published.

Plath’s poetry, considered part of the “confessional movement,” was influenced by Robert Lowell as well as by her friend, the poet Anne Sexton, who also explored dark themes and death in her work (and who, like Plath, committed suicide).

Once Plath started to publish, her star quickly rose in the world of poetry. Her first collection, The Colossus, was published in 1960. Its poems were intense, personal, and delicately crafted. In Ariel, the beauty of craft remains even as it reveals the fissures growing in the poet’s psyche. According to the Penguin Companion to American Literature:

“The Colossus (1960) and the posthumous Ariel (1965) show a remarkable development. The first is a largely personal poetry, intense and delicately rendered, usually dealing with the relationship of the poet and a perceived object from which she seeks illumination, ‘that rare, random descent.’

It is controlled, serious verse but her later work shows new strains and pressures at work and becomes a poetry of anguished confession.”

The 1965 edition revealed the heavy hand of Ted Hughes. He had omitted twelve poems that Plath had earmarked for the collection, and included twelve others of his own choosing. In 2004, a restored edition of Ariel was published.

Following are two reviews of Ariel from 1965, the first of which is by A. Alvarez, a longtime champion of Plath and her poetry, and a poet in his own right.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Sylvia Plath

. . . . . . . . . . .

Poetry in Extremis — an analysis of Ariel

From the original review in The Observer, March 14, 1965, written by A. Alvarez: It is over two years now since Sylvia Plath died at the age of thirty, and in that time a myth has been gathering around her work.

It has to do with her extraordinary outburst of creative energy in the months before her death, culminating in the last few weeks when, as she herself wrote, she was at work every morning between four and seven, producing two sometimes three poems a day.

All of these last verses were intensely personal, nearly all were about dying. So when her death finally came it was prepared for and, in some degree, understood.

However wanton it seemed, it was also, in a way, inevitable, even justified, like some final unwritten poem.

The last works were something quite new in poetry. I wrote at the time in The Observer that Plath was “systematically probing that narrow, violent areas between the viable and the impossible, between experience which can be transmuted into poetry and that which is overwhelming.”

In order to tap knowingly the deep reservoirs of feeling that are released usually only in breakdown she was deliberately cutting her way through poetic conventions, shedding her old life, old emotions, old forms. Yet she underwent this process as an artist.

If the poems are despairing, vengeful, and destructive, they are at the same time tender, open, and also unusually clever, sardonic, hard minded:

Dying

Is an art, like everything else.

I do it exceptionally well.

I do it so it feels like hell.

I do it so it feels real.

I guess you could say I’ve a call.

The myth, then, is a diversion from the objective achievement. For the very has an originality that keeps it apart from any poetic fads. It is too concentrated and detached and ironic for “confessional” verse, with all hat implies of self-indulgent cashing-in on misfortunes; and it is violent without any deliberate exploitation of horrors and petty nastiness.

If these last poems could never have been predicted from her first collection, The Colossus, this is not simply because such a leap is always unforeseeable, but because her earlier absorption with style would, in the the usual order of things, have made it doubly hard for her to bore through the crust of mere craftsmanship and release the lava below.

Technically, the basic difference between the earlier and later poems is that the first were written for the eye, and the last for the ear. They need to be read aloud; they are original because she discovered in them her own speaking voice, her own identity.

So the poems run with an inner rhythm which alters with the pressure of feeling and allows the images, which came crowding in with an incredible fertility and accuracy, to shift into one another, define and modify one another, and rub off colors each on the next.

To take a straightforward example from “The Arrival of the Bee Box”:

I put my eye on the grid.

It is dark, dark.

With the swarm feeling of African hands

Minute and shrunk for export.

Black on black, angrily clambering.

How can I let them out?

It is the noise that appeals me most of all,

The unintelligible syllables.

It is like a Roman mob,

Small, taken one by one, but my god,

together!

I lay my ear to furious Latin,

I am not Caesar.

I have simply ordered a box of maniacs.

They can be sent back.

They can die, I need feed them nothing, I

am the owner.

It starts as simple narrative description; but as “dark” is repeated it is somehow made to reverberate inwardly, crystallizing into a metaphor which voices her underlying sense of threat.

That menace carries over into the next bit of description (of the noise) and shift, though another image, into wry helplessness (“I am not Caesar”); at which point a sense of proportion reasserts itself: “They can die … I am the am the owner.”

So a trivial incident gathers into a whole complicated nexus of feelings about the way her life is getting out of control. It is a brilliant balancing act between colloquial sanity and images which echo down and open up the depths.

Many of the poems are more difficult than that, rawer, more extreme. But all have that combination of exploratory invention, violent, threatened personal involvement and a quizzical edge of detachment. The poems are casual yet concentrated, slangy yet utterly unexpected.

They are works of great artistic purity and despite all the nihilism, great generosity.

Ariel is only a selection from a mass of work Plath left. Some of the other pomes have been printed here and there, some have been recorded, some exist only in manuscript. It is to be hoped that all this remaining verse will soon be published. As it is, this book is a major literary event.

. . . . . . . . . . .

10 of Sylvia Plath’s Best-Loved Poems

. . . . . . . . . . .

A 1965 review of Ariel by Sylvia Plath

From the original review in The Age, Melbourne, Australia, July 10, 1965: Sylvia Plath was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1932. In 1956, while studying on a Fulbright grant, she met and married the poet Ted Hughes. In 1960 her first book of poems appeared, and in 1963, she committed suicide.

The poems written in the last three years of her life have been gathered in a volume titled Ariel.

They are difficult, uncertain poems, some extremely obscure and all primarily dependent on central images. Formal rhythm and the logic of rational statement are both dispensed with, the main principle of organization being a free-association technique.

How does a doomed poetess in her late twenties see death? Sylvia Plath was, in poetry at least, a stubbornly brave young woman, determined to face reality objectively, but at the same time neither to posture nor to cant.

The poems witness to a singularly pure sense of reality, a personality capable of many responses and of sustaining an attitude effectively. At one extreme she celebrates the ritual murder of her subconscious father-image in jangling staccato phrases parodying the clichés of agony column verse, and culminating in a Walpurgisnacht frenzy.

At the other she writes bitterly of her ability to survive:

It’s the theatrical

Comeback in broad day

To the same place, the same face, the same brute

Amused shout:

“A miracle!”

That knocks me out.

Some of her images take on forceful private meanings. Poppies are associated with violence and with the malignant blood cells of hemophilia, the Medusa head with the reality of death, bees with the life of the soul after death.

The last of the is a traditional usage, the other two subjective and personal. Such associations and identifications when they occur are almost always oblique and contribute to the enigmatic texture of the poetry.

Her achievement raises issues concerning the value of literature and its relation to life. The last poem suggests that words are dubious allies in the struggle to maintain a sense of reality. They are solid and fixed and resonant, abut as circumstances alter, they become emptied of meaning.

Years later I

Encounter them on the road —

Words dry and riderless,

The indefatigable hoof-taps

While

From the bottom of the pool, fixed

stars

Govern a life.

Nevertheless, her own work affirms the abiding value of literary creation, for poet and reader alike. It is no mean feat to have recorded an enduring attitude to death that embraces a sense of life in the face of suffering and weakness.

Plath’s poems are a tribute to the resourcefulness of the creative imagination and its capacity to render meaningful the hazardous course of an individual life.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Ariel by Sylvia Plath (the restored edition) on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . . .

More about Ariel by Sylvia Plath

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Sylvia Plath’s Joy (The New Yorker)

A Close Reading of Ariel — The British Library

. . . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Ariel by Sylvia Plath — a review and analyisis appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 6, 2020

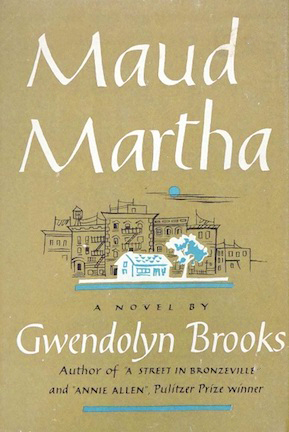

A Street in Bronzeville by Gwendolyn Brooks (1945) — Two Reviews

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917 – 2000) was just twenty-eight years old when her first book, A Street In Bronzeville, was published in 1945. Following are two original reviews from 1945 of A Street in Bronzeville, which are typical of the universal praise it received.

The title of this poetry collection, whose title was a reference to Chicago’s South Side where the poet grew up, was very well reviewed and led to her winning a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Gwendolyn Brooks’ poetic work included sonnets, ballads, and blues rhythm in free verse. She also created lengthy lyrical poems, some of which were book-length. Each poem is an exquisitely crafted portrait of fictionalized (but true-to-life) characters and landmarks of the community.

From Bronzeville forward, Brooks’ poetry work revealed thoughtful, honest, and sometimes harsh reflections of urban African American life of the mid-twentieth century. Though her lens focused on black America, many of the themes of her poetry were universal, hence its broad appeal, and the respect it earned.

Poetry was how Gwendolyn Brook made her unique, singular life. In 1968, she was named Poet Laureate for the state of Illinois, and from 1985 to 1986, she served as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. Later in her life, she taught at a number of prestigious colleges and universities.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Gwendolyn Brooks

. . . . . . . . . . .

Chicago Can Take Pride in New, Young Voice in Poetry

From the original review of A Street in Bronzeville in the Chicago Tribune, August 26, 1945, review by Paul Engle: The publication of A Street in Bronzeville is an exceptional event in the literary life of Chicago, for it is the first book of a solidly Chicago person.

Miss Brooks attended Englewood High School and Wilson Junior College. I hope they know it and are proud. But it is also an event of national importance, for Miss Brooks is the first Negro poet to write wholly out of a deep and imaginative talent.

Here is the story of a day on the South Side; it has the marvelous title of “The Sundays of Satin Legs Smith,” itself a poem. In it, Miss Brooks shows that she has a vigorous mind and uses it cunningly with slow concentration of word.

There are many poems about people and they’re all accurately human, alert, and moving. Miss Brooks goes through Chicago with her eyes wide open, taking the reader right inside the reality observed. There are keen notes on our mortal frailty, such as the amorous gentleman who, seeing an attractive woman, “wonders as his stomach breaks up in to fire and lights …”

How long it will be

Before he can, with reasonably

slight risk of rebuke, put

his hand on her knee.

There are poems which bear the immediate sense of the personal life strongly lived out:

It was quite a time for loving.

It was midnight. It was May.

But in the crowding darkness

Not a word did they say.

There is the quick observation of the shame and sorrow behind performance, as in “Queen of the Blues”:

Mame was singing

At the Midnight club.

And the place was red

With blues.

She could shake her body

Across the floor.

For what did she have

To lose?

The longest piece in the book is a sequence of poems about the soldier, called “Gay Chaps at the Bar.” They are the most controlled, the most intense poems in the book.

And they can be read for what they are and not, as the publishers want us to believe, as Negro poems. For they should no more be called Negro poetry than the poems of Robert Frost should be called white poetry. They’re poems for all readers who want warmth and softness, a quick hand and slow voice.

. . . . . . . . . .

11 Iconic Poems by Gwendolyn Brooks

. . . . . . . . . .

Poignant Music

From the original review in the Hartford Courant, November 11, 1945: It’s an encouraging sign when any good poetry is published today, and even more encouraging when such poetry is by a gifted, unusual voice bespeaking Negro genius.

We have had the fine mastery and sense for the classic form of Countee Cullen, the poignant realism of Langston Hughes, and more recently, the powerful prose of Richard Wright. That the quality of rhythmic song is innate to the black pen has been persistently demonstrated by the work of these and other writers.

Now comes Gwendolyn Brooks, displaying all the old, ready aptitude for idiomatic music, but with a great deal of depth, original thinking, and expression.

Here is a fearlessly eloquent poet who can handle any mood or meter equally well, any subject and form, and at the same time give us poetry of ideas, not merely cerebral, which goes far beyond the bitterness against the “the White Race.” The bitterness is there, but it’s not the exclusively motivating factor.

Gwendolyn Brooks writes good satirical sketches, comic verse, love poems, acid sketches of Negro life and manners, poetry of the tenderest emotion and compassion, and verses about the the war that stab the conscience.

In a good deal of her work she prefers the use of consonance to rhyme, and somehow this manner seems curiously fitted to her purpose.

Illustrative of the poet’s depth of perception and trenchant expression, is the following poem:

The White Troops Had Their Order But the Negroes Looked Like Men

They had supposed their formula was fixed.

They had obeyed instructions to devise

A type of cold, a type of hooded gaze.

But when the Negroes came they were perplexed.

These Negroes looked like men. Besides, it taxed

Time and the temper to remember those

Congenital iniquities that cause

Disfavor of the darkness. Such as boxed

Their feelings properly, complete to tags —

A box for dark men and a box for Other —

Would often find the contents had been scrambled.

Or even switched. Who really gave two figs?

Neither the earth nor heaven ever trembled.

And there was nothing startling in the weather.

[read an analysis of this poem, “Gwendolyn Brooks and Positive Integration”]

If this is her first book, in the years to come we may certainly expect great poetry form Gwendolyn Brooks. All the promise and the poignant music are here.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Gwendolyn Brooks page on Amazon*

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post A Street in Bronzeville by Gwendolyn Brooks (1945) — Two Reviews appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 1, 2020

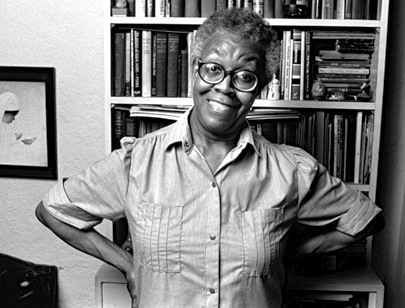

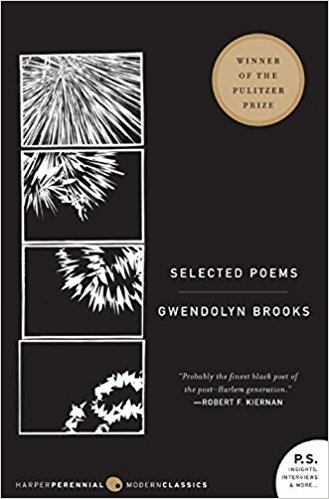

11 Iconic Poems by Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917 – 2000) sustained a decades-long career as a poet, and was recognized with many awards and honors during her lifetime. Following is a sampling of poems by Gwendolyn Brooks, with links to analyses following each one.

This selection doesn’t claim to be the most iconic of her poems, as that would be a tough call — so much of her work is a worthy part of the American literary canon. Brooks’s poetic work included sonnets, ballads, and blues rhythm in free verse. She also created lyrical poems, some of which were book-length.

Much of her poetry reflected on urban African-American life, though its themes were universal to the human experience. Her output was impressive, encompassing more than twenty books, including children’s books.

Brooks broke into book publishing in 1945 with A Street In Bronzeville, referring to an area in the Chicago’s South Side. It was an auspicious beginning, as this poetry collection led to her winning a Guggenheim Fellowship.

The epic, book-length poem Annie Allen (1949) earned Brooks a Pulitzer Prize in 1950, making her the first African-American to win this award.

In her storied career, Brooks was Poet Laureate for the state of Illinois, Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, and taught at several prominent universities. But what she’s remembered for most was this skill with which she used her poetic voice to spread tolerance and understanding the black experience in America.

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Gwendolyn Brooks

. . . . . . . . . .

The Children of the Poor

1

People who have no children can be hard:

Attain a mail of ice and insolence:

Need not pause in the fire, and in no sense

Hesitate in the hurricane to guard.

And when wide world is bitten and bewarred

They perish purely, waving their spirits hence

Without a trace of grace or of offense

To laugh or fail, diffident, wonder-starred.

While through a throttling dark we others hear

The little lifting helplessness, the queer

Whimper-whine; whose unridiculous

Lost softness softly makes a trap for us.

And makes a curse. And makes a sugar of

The malocclusions, the inconditions of love.

2

What shall I give my children? who are poor,

Who are adjudged the leastwise of the land,

Who are my sweetest lepers, who demand

No velvet and no velvety velour;

But who have begged me for a brisk contour,

Crying that they are quasi, contraband

Because unfinished, graven by a hand

Less than angelic, admirable or sure.

My hand is stuffed with mode, design, device.

But I lack access to my proper stone.

And plenitude of plan shall not suffice

Nor grief nor love shall be enough alone

To ratify my little halves who bear

Across an autumn freezing everywhere.

3

And shall I prime my children, pray, to pray?

Mites, come invade most frugal vestibules

Spectered with crusts of penitents’ renewals

And all hysterics arrogant for a day.

Instruct yourselves here is no devil to pay.

Children, confine your lights in jellied rules;

Resemble graves; be metaphysical mules.

Learn Lord will not distort nor leave the fray.

Behind the scurryings of your neat motif

I shall wait, if you wish: revise the psalm

If that should frighten you: sew up belief

If that should tear: turn, singularly calm

At forehead and at fingers rather wise,

Holding the bandage ready for your eyes.

(from Annie Allen, 1949)

Analysis of Children of the Poor

. . . . . . . . . .

The Mother

Abortions will not let you forget.

You remember the children you got that you did not get,

The damp small pulps with a little or with no hair,

The singers and workers that never handled the air.

You will never neglect or beat

Them, or silence or buy with a sweet.

You will never wind up the sucking-thumb

Or scuttle off ghosts that come.

You will never leave them, controlling your luscious sigh,

Return for a snack of them, with gobbling mother-eye.

I have heard in the voices of the wind the voices of my dim killed

children.

I have contracted. I have eased

My dim dears at the breasts they could never suck.

I have said, Sweets, if I sinned, if I seized

Your luck

And your lives from your unfinished reach,

If I stole your births and your names,

Your straight baby tears and your games,

Your stilted or lovely loves, your tumults, your marriages, aches,

and your deaths,

If I poisoned the beginnings of your breaths,

Believe that even in my deliberateness I was not deliberate.

Though why should I whine,

Whine that the crime was other than mine?—

Since anyhow you are dead.

Or rather, or instead,

You were never made.

But that too, I am afraid,

Is faulty: oh, what shall I say, how is the truth to be said?

You were born, you had body, you died.

It is just that you never giggled or planned or cried.

Believe me, I loved you all.

Believe me, I knew you, though faintly, and I loved, I loved you

All.

(from Blacks, 1987)

Analysis of The Mother

. . . . . . . . . .

We Real Cool

The Pool Players.

Seven at the Golden Shovel.

We real cool. We

Left school. We

Lurk late. We

Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We

Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We

Die soon.

(from The Bean Eaters, 1960)

Analysis of We Real Cool

. . . . . . . . . . .

To Be in Love

To be in love

Is to touch with a lighter hand.

In yourself you stretch, you are well.

You look at things

Through his eyes.

A cardinal is red.

A sky is blue.

Suddenly you know he knows too.

He is not there but

You know you are tasting together

The winter, or a light spring weather.

His hand to take your hand is overmuch.

Too much to bear.

You cannot look in his eyes

Because your pulse must not say

What must not be said.

When he

Shuts a door —

Is not there—

Your arms are water.

And you are free

With a ghastly freedom.

You are the beautiful half

Of a golden hurt.

You remember and covet his mouth

To touch, to whisper on.

Oh when to declare

Is certain Death!

Oh when to apprize

Is to mesmerize,

To see fall down, the Column of Gold,

Into the commonest ash.

. . . . . . . . . .

Poetic Quotes from Maud Martha by Gwendolyn Brooks

. . . . . . . . . .

Sadie and Maud

Maud went to college.

Sadie stayed home.

Sadie scraped life

With a fine toothed comb.

She didn’t leave a tangle in

Her comb found every strand.

Sadie was one of the livingest chicks

In all the land.

Sadie bore two babies

Under her maiden name.

Maud and Ma and Papa

Nearly died of shame.

When Sadie said her last so-long

Her girls struck out from home.

(Sadie left as heritage

Her fine-toothed comb.)

Maud, who went to college,

Is a thin brown mouse.

She is living all alone

In this old house.

(from Selected Poems , Harper & Row, 1963)

Analysis of Sadie and Maud

. . . . . . . . . . .

A Sunset of the City

Already I am no longer looked at with lechery or love.

My daughters and sons have put me away with marbles and dolls,

Are gone from the house.

My husband and lovers are pleasant or somewhat polite

And night is night.

It is a real chill out,

The genuine thing.

I am not deceived, I do not think it is still summer

Because sun stays and birds continue to sing.

It is summer-gone that I see, it is summer-gone.

The sweet flowers indrying and dying down,

The grasses forgetting their blaze and consenting to brown.

It is a real chill out. The fall crisp comes.

I am aware there is winter to heed.

There is no warm house

That is fitted with my need.

I am cold in this cold house this house

Whose washed echoes are tremulous down lost halls.

I am a woman, and dusty, standing among new affairs.

I am a woman who hurries through her prayers.

Tin intimations of a quiet core to be my

Desert and my dear relief

Come: there shall be such islanding from grief,

And small communion with the master shore.

Twang they. And I incline this ear to tin,

Consult a dual dilemma. Whether to dry

In humming pallor or to leap and die.

Somebody muffed it? Somebody wanted to joke.

(from Selected Poems , Harper & Row, 1963)

Analysis of Sunset of the City

. . . . . . . . . .

Boy Breaking Glass

Whose broken window is a cry of art

(success, that winks aware

as elegance, as a treasonable faith)

is raw: is sonic: is old-eyed première.

Our beautiful flaw and terrible ornament.

Our barbarous and metal little man.

“I shall create! If not a note, a hole.

If not an overture, a desecration.”

Full of pepper and light

and Salt and night and cargoes.

“Don’t go down the plank

if you see there’s no extension.

Each to his grief, each to

his loneliness and fidgety revenge.

Nobody knew where I was and now I am no longer there.”

The only sanity is a cup of tea.

The music is in minors.

Each one other

is having different weather.

“It was you, it was you who threw away my name!

And this is everything I have for me.”

Who has not Congress, lobster, love, luau,

the Regency Room, the Statue of Liberty,

runs. A sloppy amalgamation.

A mistake.

A cliff.

A hymn, a snare, and an exceeding sun.

(from Blacks, Third World Press, 1987)

Analysis of A Boy Breaking Glass

. . . . . . . . . . . .

The Bean Eaters

They eat beans mostly, this old yellow pair.

Dinner is a casual affair.

Plain chipware on a plain and creaking wood,

Tin flatware.

Two who are Mostly Good.

Two who have lived their day,

But keep on putting on their clothes

And putting things away.

And remembering . . .

Remembering, with twinklings and twinges,

As they lean over the beans in their rented back room that

is full of beads and receipts and dolls and cloths,

tobacco crumbs, vases and fringes.

(from The Bean Eaters, 1960)

Analysis of The Bean Eaters

. . . . . . . . . . .

Gwendolyn Brooks Quotes on Writing and Life

. . . . . . . . . . .

Jessie Mitchell’s Mother

Into her mother’s bedroom to wash the ballooning body.

“My mother is jelly-hearted and she has a brain of jelly:

Sweet, quiver-soft, irrelevant. Not essential.

Only a habit would cry if she should die.

A pleasant sort of fool without the least iron. . . .

Are you better, mother, do you think it will come today?

The stretched yellow rag that was Jessie Mitchell’s mother

Reviewed her. Young, and so thin, and so straight.

So straight! as if nothing could ever bend her.

But poor men would bend her, and doing things with poor men,

Being much in bed, and babies would bend her over,

And the rest of things in life that were for poor women,

Coming to them grinning and pretty with intent to bend and to kill.

Comparisons shattered her heart, ate at her bulwarks:

The shabby and the bright: she, almost hating her daughter,

Crept into an old sly refuge: “Jessie’s black

And her way will be black, and jerkier even than mine.

Mine, in fact, because I was lovely, had flowers

Tucked in the jerks, flowers were here and there . . .”

She revived for the moment settled and dried-up triumphs,

Forced perfume into old petals, pulled up the droop,

Refueled

Triumphant long-exhaled breaths.

Her exquisite yellow youth . . .

(from Selected Poems, Harper & Row, 1963)

Analysis of Jessie Mitchell’s Mother

. . . . . . . . . . .

A Song In The Front Yard

I’ve stayed in the front yard all my life.

I want a peek at the back

Where it’s rough and untended and hungry weed grows.

A girl gets sick of a rose.

I want to go in the back yard now

And maybe down the alley,

To where the charity children play.

I want a good time today.

They do some wonderful things.

They have some wonderful fun.

My mother sneers, but I say it’s fine

How they don’t have to go in at quarter to nine.

My mother, she tells me that Johnnie Mae

Will grow up to be a bad woman.

That George’ll be taken to Jail soon or late

(On account of last winter he sold our back gate).

But I say it’s fine. Honest, I do.

And I’d like to be a bad woman, too,

And wear the brave stockings of night-black lace

And strut down the streets with paint on my face.

(from Selected Poems, 1963)

Analysis of A Song In The Front Yard

. . . . . . . . . . .

kitchenette building

We are things of dry hours and the involuntary plan,

Grayed in, and gray. “Dream” makes a giddy sound, not strong

Like “rent,” “feeding a wife,” “satisfying a man.”

But could a dream send up through onion fumes

Its white and violet, fight with fried potatoes

And yesterday’s garbage ripening in the hall,

Flutter, or sing an aria down these rooms

Even if we were willing to let it in,

Had time to warm it, keep it very clean,

Anticipate a message, let it begin?

We wonder. But not well! not for a minute!

Since Number Five is out of the bathroom now,

We think of lukewarm water, hope to get in it.

(from Selected Poems, Harper & Row, 1963)

Analysis of kitchenette building

. . . . . . . . . . .

Gwendolyn Brooks page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 11 Iconic Poems by Gwendolyn Brooks appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 30, 2020

Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain (1933)

Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain (1893– 1970) has endured as this British author’s best known work. A memoir on how her life, and that of her generation, were forever marked by the losses endured as a result of World War I, it is indeed a touching testament.

Her brother, Edward, and her fiancé, Ronald Leighton were both killed during the war, and she never fully recovered from these tragic losses and placed them poignantly in the context of the horrors of the war.

As a result of the these losses, and the suffering she personally witnessed as a volunteer nurse during the war, led her to become a pacifist. She remained a dedicated member of the peace movement for the rest of her life.

Testament of Youth is now recognized as one of the most iconic memoirs of the twentieth century. Written with the perspective of time, Vera was a published author as well as a wife and mother when she began the book. She attempted to fictionalize the narrative at first, but it wasn’t working. In a 2013 homage to Testament of Youth on its eighty year anniversary, The Guardian (U.K.) wrote:

“It was only when she decided to write as herself that her authorial voice seemed to flow and the events she had endured were given a poignant immediacy to which readers could relate. In Testament of Youth, the words seemed to pour out of her, a potent mixture of rage and loss, underpinned by lively intelligence and fervent pacifist beliefs.”

The book was an instant success, with all 3,000 printed copies selling out on publication day. Over the next six years, the book sold more than 120,000 copies and earned praise from many writers, including Virginia Woolf, who wrote in her journal that she stayed up all night to finish reading it.

In the U.S., Testament of Youth was a critical and commercial success as well, praised as “heartbreakingly beautiful.” Here is a review from the time of its publication, capturing the flavor of the book and the important story and lessons in its pages.

In recent years, Testament of Youth has been brought back to life a number of television and film adaptations.

. . . . . . . . . . .

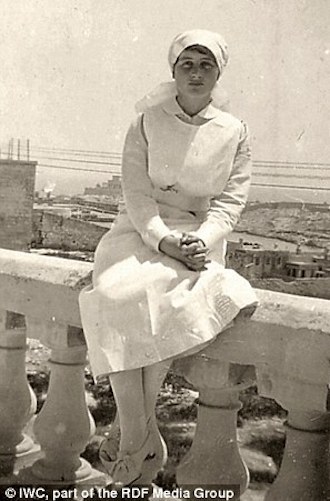

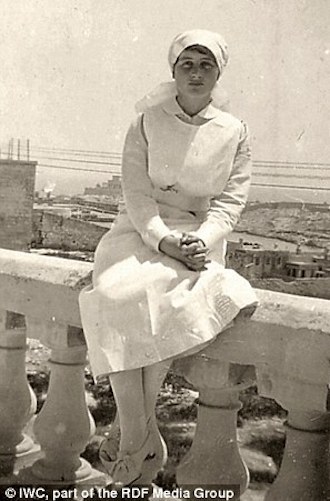

Vera Brittain as a World War I V.A.D. nurse

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1933 review of Testament of Youth

From the original review of Testament of Youth in the Salt Lake Tribune, November 12, 1933, by E.E. Hollis:

An autobiographical story of the war generation of England — moving, beautiful, and tragic

Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain is a book whose deep significance can hardly be overestimated. Of importance in its historical aspect, it is also a spiritual record of impelling power. Dealing with the war period, it is unlike any other story of those years.

Vera Brittain was of that generation to whom the war came to interrupt its preparation for life, to blight its budding hopes, and to put a new and ugly face upon its whole world. Her autobiography is a testament to what English youth suffered and lost during the World War I years.

Her story covers the first quarter of the twentieth century and makes startlingly clear the extraordinary changes wrought, in manners and morals, in society and politics. Her childhood as the daughter of the middle class is described briefly.

When the first rumbles of war were heard, Miss Brittain had succeeded, after much difficulty, in overcoming her father’s opposition to college for his “little girl.” She sought to be released from the boredom of “provincial young ladyhood” and was preparing for entrance to Oxford.

Life was opening joyfully; her bent for literature was to be satisfied and also dreams of love were stirring. She had found a most congenial companion in her brother Edward’s school intimate, Ronald Leighton, a brilliant young man.

Miss Brittain went to Oxford, but Edward and Ronald, who were to have started at the same time, were now in uniform. All she had worked so hard to achieve now seemed empty.

Joining the V.A.D.

By the spring of 1915 Miss Brittain had become a V.A.D. (Voluntary Aid Detachment — women who tended to wounded soldiers, of whom it was said later, “no one less than God Almighty could give a correct definition of the job of a V.A.D”), doing unpleasant tasks cheerfully, feeling that in a measure she shared the hardships her lover was enduring in France. She also lived on letters from the front.

. . . . . . . . . .

Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain on Amazon*

Losing a brother and a lover

At Christmas 1915 Ronald was to have his leave. On leave at home she waited with great anticipation fro his message, but the message was from his sister Clare, to say that Ronald had died of wounds at a Casualty Clearing station on the eve of his return.

Battling through her “individual hell,” she carried on at the London hospital, and was able to nurse her dearly loved brother, returning with convoys flowing back to the hospital from the battle on the Somme. Months later, Edward was killed in action on the Italian front.

Miss Brittain was sent on foreign service in Malta, in whose glamorous, sunlit beauty her heart wounds found some solace and healing. Later, she learned of the horrors of the general hospital at Etaples, through with passed a ceaseless storm of Tommies during the somber days when the German offensive rolled forward.

Here, too, she watched “the United States physically entering the war … our deliverers at last, marching; a formidable bulwark against the peril looming.”

The agony and falsity of war

All of these strenuous, anguishing experiences make engrossing, if painful, pages; it is through the letters of Ronald, Edward, and Miss Brittain herself, that one realizes the fierce agonies of their generation. It is not intended to minimize them, for this testament of youth is a challenge to forgetting, to the succeeding generation that they shall know what war means.

Miss Brittain insists, “The causes of war are always falsely represented; its honour is dishonest and its glory meretricious.” There is, too, comment on the injustices and follies in the conduct of war, resulting from mature reflection and understanding.

The record carries on through the post-war years, in which a maimed generation of youth struggled gallantly to gather up the broken pieces and rebuild life.

A return to Oxford, and to life

In 1919, the year “dominated by a thoroughly nasty Peace,” Vera Brittain returned to Oxford, accepted yet not welcomed as one of those “immoral” V.A.D.s. The story of her rise and activities as a journalist, lecturer, author, and internationalist, is scarcely less moving and important than the earlier chapters.

Testament of Youth is not one to read for pleasurable pastime, but one that insists on being read. It is alt once beautiful, terrible, and tragic, and written with courage and honesty.

More about Testament of Youth

My Mother Never Got Over the Loss of her Lover

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Testament of Youth: Book of a Lifetime

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain (1933) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 29, 2020

The Power of Her Pen: The Story of Groundbreaking Journalist Ethel L. Payne by Lesa Cline-Ransome

The story of Ethel L. Payne (1911 – 1991), the American journalist and correspondent, is a portrait of persistence, passion, and determination. Award-winning author Lesa Cline-Ransome has told her story in an inspiring book for younger readers. We’ll get to that after a brief introduction to Ethel Payne’s life and work.

Ethel grew up in a working-class African-American family in Chicago. She was a diligent student and avid reader, and showed an early interest in writing.

Pursuing the dream of becoming a reporter was no small feat for a black woman of Ethel’s era. A trailblazer from the start, she set her own path, which began in Washington, D.C. during World War II and in post-war Japan. Her experiences in both places shaped her as a journalist and activist.

Later in life, she said of her storied career: “I’ve been an eyewitness to so many profound things and so many changes … I’ve had a box seat on history, and that’s a rare thing.”

Ethel’s groundbreaking journey paralleled that of Alice Dunnigan, her contemporary and colleague. Like Alice, she was a correspondent for the Chicago Defender and worked as a White House correspondent.

And like Alice, Ethel angered president Eisenhower simply by asking direct questions about civil rights issues. Some newsmen thought that the two women competed for who could ask the toughest questions, but both were just trying to do their jobs well.

. . . . . . . . .

Photo: Washington Post

. . . . . . . . .

After being confronted with questions he didn’t care to answer, Eisenhower made a practice of ignoring both Ethel and Alice, looking past them to call on the mostly white, mostly male press corps. But the two women remained steadfast and true to their mission as journalists, and went on to achieve effective, award-winning careers.

Ethel was often called the “First Lady of the Black Press” for her stance as a civil rights journalist. But the best was yet to come when CBS hired her in 1972, making her the first female African-American political commentator on a national television network.

In an interview conducted late in her life and career, Ethel Payne summed up her life’s mission: “I stick to my firm, unshakeable belief that the black press is an advocacy press, and that I, as a part of that press, can’t afford the luxury of being unbiased … when it come to issues that really affect my people, and I plead guilty, because I think that I am an instrument of change.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Power of Her Pen by Lesa Cline-Ransome

More about The Power of Her Pen on Simon & Schuster

The Power of Her Pen by Lesa Cline-Ransome on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

Lesa Cline-Ransome tells the story of Ethel Payne in a full-color book with lively illustrations by John Parra. Intended for young readers (though it can be enjoyed by all ages), it’s a wonderful introduction to Ethel’s life and work as one of a small group of African-American women journalists who broke through in the mid-twentieth century.

In a postscript, the author writes that pursuing journalism takes “a certain kind of grit and fearlessness.” She goes on to say that when the mainstream white press ignored stories of importance to the black community, “Ethel used her pen and her voice to report on the Montgomery Bus boycott, Rosa Parks, the plight of unwed mothers, race relations,” and more.

Through words and images, The Power of Her Pen follows Ethel through the challenges — as well as the joys — of being a bright and ambitious black female who sets her sights on journalism. What young reader with similar ambitions wouldn’t be struck by this passage:

“Ethel spend her school days daydreaming of life far beyond her neighborhood — except when she was in English class. There, her teacher, Miss Dixon, encouraged her writing. Her mother encouraged her at home. Ethel wrote during the day, and she read her stories to her family at night. The school wouldn’t let a black student work on the school newspaper, but, after reading Ethel’s writing, it did publish her very first story.”

Ethel came of age during the Great Depression, and after her father died while she was in her teens, money was tighter than ever. Determined to find a path to her dreams, she took writing classes at a local college that offered free tuition.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Ms. Cline-Ransome guides the reader through Ethel’s rise in reporting, from covering black troops overseas during World War II to circling back to her home city to report for The Chicago Defender. Ethel covered civil rights in the wake of the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling, and was able to triumph after being snubbed by President Eisenhower.

Ethel went on to effectively question presidents Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, and Carter on civil rights matters (and to actually receive answers). We also learn that she marched with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, AL, to protest for voting rights.

The book sums up Ethel Payne’s legacy, and indeed, conveys the importance of journalism in presenting the truth in order to affect change, particularly, in her case, as it pertained to the lives and struggles of African Americans:

“Her reporting highlighted their struggle for justice, equal pay, housing, and education. And, in he role of informing her readers, Ethel created awareness and activism in the fight for people across the globe.”

Lesa Cline-Ransome is the author of many award-winning and critically acclaimed nonfiction books for young readers, including Game Changers: The Story of Venus and Serena Williams; My Story, My Dance: Robert Battle’s Journey to Alvin Ailey; and Before She Was Harriet. She is also the author of the novel Finding Langston, which received a Coretta Scott King Honor Award and five starred reviews. She lives in the Hudson Valley region of New York. Learn more at LesaClineRansome.com.

See also: 10 Pioneering African-American Women Journalists

More about Ethel Payne

Ethel Payne, “First Lady of the Black Press,” Asked Questions No One Else Would”

If This Trailblazing Journalist Hadn’t Been a Black Woman, You Would Know Her Name

Wikipedia

Women’s History

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Power of Her Pen: The Story of Groundbreaking Journalist Ethel L. Payne by Lesa Cline-Ransome appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 26, 2020

The Sea, The Sea by Iris Murdoch (1978)

The Sea, the Sea by Iris Murdoch (1919 – 1999) was the prolific British author’s nineteenth novel. Following is a review and analysis from 1978, the year in which it was published.

The story of Charles Arrowby, a self-involved and egotistical retired theater director begins as he is setting about to write his memoir. To focus on this task, he secludes himself in a house, not surprisingly, near the sea. He muses:

“Then I felt too that I might take this opportunity to tie up a few loose ends, only of course loose ends can never be properly tied, one is always producing new ones. Time, like the sea, unties all knots. Judgements on people are never final, they emerge from summings up which at once suggest the need of a reconsideration. Human arrangements are nothing but loose ends and hazy reckoning, whatever art may otherwise pretend in order to console us.”

As he looks back over his life, he encounters his first, adolescent love, now much older and hardly recognizable. This upends his quiet plans as he grows obsessed with her, and sets off some farcical situations.

The Sea, The Sea was critically acclaimed and won the 1978 Booker Prize.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Iris Murdoch

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1978 Review of The Sea, The Sea by Iris Murdoch

From the original review of The Sea, The Sea by Iris Murdoch by Lorna Sage in the Observer Sun, London, August 27, 1978:

“Those who want to be saved,” wrote Iris Murdoch in her book on Plato, “should look at the stars and talk philosophy, not write or go to the theatre.”

It’s a fair summary of the plot of this novel. Not the message, of course. She is adept as ever at keeping her philosophy and her fiction in their separate realms, and The Sea, The Sea is inventive, gossipy, and fantastic, not at all preachy.

Nonetheless she has lumbered her characters with some of the more choice (i.e. insoluble, fascinating, humiliating) problems her philosophical alter ego has been exploring lately.

Charles Arrowby, renowned theatre director

The hero, Charles Arrowby, is a retired and celebrated theatre director and, it goes almost without saying, a sentimental cynic and a monster of egotism.

He sets out to write his memoirs from his seaside retreat with a cozy reminiscent sense of achievement — modestly comparing himself to Prospero, abjuring the old magic, etc. — only to be stopped in his tracks by a dreadful and spectacular haunting he has not, for once, engineered.

The life he’d foreseen — the windy, wave-beaten promontory, the sketchy “nature study,” the small gourmet treats (Iris Murdoch does wonders of sneaky characterization by having him gloat over his solitary, greedy, unappetizing menus), the lighthearted pleasure of torturing infatuated ex-mistresses — all begins to disintegrate, as people and nameless things from the past crowd into his field of vision.

A first love reappears

The most embarrassing of his apparitions is a Loch Ness-style sea monster fainting in coils; the most unlikely his first and lost love, now a shy, lumpy 60-year-old who turns out to be living in a twee bungalow round the corner with her equally substantial husband.

Shaken but undefeated (indeed, rather roused by the challenges — this is where the real fun starts), Charles takes them all on, and tries mightily to fashion them into an Arrowby production.

Hartley, the lost love, he casts in the role of an aging Andromeda; himself, of course, as Perseus. Her husband, Ben, is obviously the sea beast, though he can’t swim.

And this is only one of many ingenious ploys; ‘resting’ actor friends who visit out of curiosity, and stay out of malice, get fitted in, too, like sad Gilbert, who thinks he’s in the Tempest plot, and saws wood in great quantities to prove it.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Sea, The Sea by Iris Murdoch on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

A change of tone from funny to strange

So far, the book is very funny, and exactly conveys the tone and feel of a theatre world where people become, as it were, addicts of illusion, accustomed to manipulate or be manipulated.

When Charles steps decisively over into reality, though, and kidnaps Hartley, the tone changes: he comes up against a level of living, of sheer, mysterious ordinariness he knows nothing about. Her marriage may be stuffy, changeless, tasteless, even unhappy, but it’s real, and Charles can only eavesdrop on it, obscenely, like a Peeping Tom.

At this point, he starts to get the queasy feeling Iris Murdoch’s egotistical characters all dread: “I had lost control of my life and of the lives with which I was meddling … I had awakened some sleeping demon, set going some deadly machine.”

A breathless climax and an epiphany

His personal sorcery suddenly fails to work, the forces of necessity (chaos, the amorphous surrounding sea) take over, in one of those manic, violent, coincidental climaxes that leave the characters (and the reader) breathless. Death, along with marriage, is an inevitable touchstone of reality for Murdoch.

Charles sees for perhaps the first time in his life round the edge of his own fantasizing ego, beyond the picturesque intrigues and passionate delusions that have been the stuff of his personal and professional life. He learns, in short, to look at the stars and talk philosophy.

And this is where Murdoch’s Platonic dialog with herself comes to the foreground. What fascinates her and irritates her more than anything is the wasteful paradox of self-knowledge — the fact that we can truly know ourselves only by the crashing messily not the limits of our freedom.

A melding of fiction and philosophy

This book has a saint, in the unlikely person of Charles’s cousin James, an ex-Army man who discovered Buddhism while engaged in Tibet, and who performs several startling miracles to rescue the others from their nightmare. James, though, is thankfully a minor character, a mere catalyst.

Charles is the hero because his theatrical memoir-scribbling existence is the best (i.e. most problematic) metaphor for how most of us function. By the end, of course, he has mostly mislaid his momentary vision, and is back playing games.

I suppose this is what Iris Murdoch means when she distinguishes between philosophy and fiction — that what the novel does superlatively is mirror our continuing confusion and muddle.

The Sea, The Sea, certainly manages an exhilarating, and occasionally dreadful anarchy. Her habit of inventing golden boys, for instance, and then killing them off as symbols of lost dreams (Beautiful Joe in Henry and Cato; equally beautiful and doomed Titus in this book) is getting to be worrisome in a way that I don’t think has much to do with Plato.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from The Sea, The Sea

“The theatre is certainly a place for learning about the brevity of human glory: oh all those wonderful glittering absolutely vanished pantomimes.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I’ve felt as if I didn’t exist, as if I were invisible, miles away from the world, miles away. You can’t imagine how much alone I’ve been all my life.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There was something factitious and brittle and thereby utterly feminine about her charm which made me want to crush her, even to crunch her. She had a slight cast in one eye which gives her gaze a strange concentrated intensity. Her eyes sparkle, almost as if they were actually emitting sparks. She is electric. And she could run faster in very high-heeled shoes than any girl I ever met.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I felt a deep grief that crouched and stayed still as if it was afraid to move.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I ate and drank slowly as one should (cook fast, eat slowly) and without distractions such as (thank heavens) conversation or reading. Indeed eating is so pleasant one should even try to suppress thought. Of course reading and thinking are important but, my God, food is important too.

How fortunate we are to be food-consuming animals. Every meal should be a treat and one ought to bless every day which brings with it a good digestion and the precious gift of hunger.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“What a queer gamble our existence is. We decide to do A instead of B and then the two roads diverge utterly and may lead in the end to heaven and to hell. Only later one sees how much and how awfully the fates differ. Yet what were the reasons for the choice? They may have been forgotten. Did one know what one was choosing? Certainly not.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“However life, unlike art, has an irritating way of bumping and limping on, undoing conversions, casting doubt on solutions, and generally illustrating the impossibility of living happily or virtuously ever after.”

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Sea, The Sea by Iris Murdoch (1978) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 23, 2020

Vera Brittain

Vera Brittain (December 29, 1893– March 29, 1970) was a British memoirist, poet, essayist, and novelist whose work and life were forever marked by the losses she endured as a result of World War I. She’s best remembered for her classic memoir, Testament of Youth (1933).

As a young wartime nurse, she tended to wounded soldiers in several countries. Her brother and her fiancé were killed during the war. Brittain never fully recovered from the tragic loss, and the horrors of the war are poignantly depicted in her writings.

The suffering she witnessed inspired her to become a pacifist after the war, and she was an active, dedicated member of the peace movement for the rest of her life.

Early Life and Education

Vera Brittain was born in the Staffordshire town of Newcastle-under-Lyme. Her parents, Thomas and Edith Brittain, owned paper mills in the towns of Hadley and Cheddleton.

The family moved to Macclesfield in the Cheshire area when Vera was 18 months of age, and they lived in Buxton, a spa town, when Vera was aged 11 to 13. At the age of 13, Vera attended St. Monica’s, a boarding school in Surrey.

Against her father’s wishes, she majored in English literature at Oxford University, entering at the age of twenty.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

World War I service and tragic losses

While she was an Oxford student in 1915, the university granted her leave to serve as a nurse for those wounded in the war. She was one of the first female students to be granted this type of leave.

Serving as a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse, she cared for soldiers in Buxton and London before being sent to tend to the wounded in Malta and France.

Brittain’s fiance, Roland Leighton, was tragically killed shortly before Christmas in 1915. While repairing barbed wire in a no-man’s land late one night, he was shot by a German sniper.

Vera’s brother, Edward, was killed in action while serving in Italy in the summer of 1918. Her brother’s close friends, Geoffrey Thurlow and Victor Richardson, also lost their lives during the war. These losses profoundly impacted Brittain, and she would eventually use writing as a vehicle to express her pain.

In a 1916 letter to Edward, Vera wrote, “If the war spares me, it will be my one aim to immortalise in a book the story of us four.” She would go on to do just that, and the book, Testament of Youth, became a British classic.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

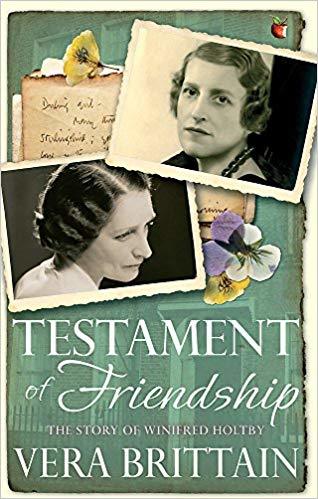

Friendship with Winifred Holtby

After the war, Vera Brittain returned to Oxford University and changed her major to history. She formed a close friendship with Winifred Holtby and had aspirations of becoming an established author in London. This deep friendship, cut short by Holtby’s untimely death at age 37, was described in this 2013 homage to Brittain and Holtby’s friendship in The Telegraph (U.K.)

“As writers they were the most decisive influences on each other’s work. It was a relationship, above all, that made significant contributions to the writing of two bestselling masterpieces, which have stood the test of time: Brittain’s memoir of the cataclysmic effect of the First World War on her generation, Testament of Youth, and Holtby’s South Riding, her novel about a Yorkshire community struggling in the grip of the Great Depression of the Thirties.

After Holtby’s death, Brittain memorialized their friendship in a biography of Winifred which, she hoped, would remind people ‘of the glowing, radiant generous, golden creature whom we have lost.’ This friendship has achieved iconic status, as an example of an emotionally and intellectually supportive relationship between two women, of a kind rarely recorded in literature.”

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

First publications

In August 1919, Brittain’s first book of poetry was published. Entitled Verses of a V.A.D., it included a poem dedicated to Edward.

The Dark Tide, her first novel, followed in 1923. The work detailed life at Oxford University and was controversial for its discussion of sexism at the institution. Another novel, Anderby Wold, was published that same year.

Marriage and family

Vera married the political scientist George Catlin in 1925. The couple had two children. Their son, John, was born in 1927 and became an artist with whom Vera reportedly had a difficult relationship. Shirley, the couple’s daughter, was born in 1930 and became a member of the British parliament.

Testament of Youth

In 1933, Brittain published her memoir, Testament of Youth. Now recognized as one of the most iconic memoirs of the twentieth century, the work tells of the experiences she endured during World War I. Vera’s fiancee, her brother, and her brother’s friends who died are all prominently featured in the book.

Typed on a typewriter in the study at her home in Chelsea, Vera worked on the book for seven hours each day while her young children played. At first she attempted to fictionalize the narrative, but without success. It was only when she let it flow as a memoir that it fell into place.

A 2013 homage to Testament of Youth on its eighty year anniversary, The Guardian (U.K.) wrote:

“It was only when she decided to write as herself that her authorial voice seemed to flow and the events she had endured were given a poignant immediacy to which readers could relate. In Testament of Youth, the words seemed to pour out of her, a potent mixture of rage and loss, underpinned by lively intelligence and fervent pacifist beliefs.”

The book was instantly successful, with all 3,000 printed copies selling out on publication day.

Over the next six years, the book sold more than 120,000 copies and earned praise from writer Virginia Woolf, who wrote in her journal that she stayed up all night to finish reading it. After being published in the United States, Testament of Youth was lauded as “heartbreakingly beautiful.”

Works after 1930

South Riding, was published in 1936. Her 1940 work, Testament of Friendship, was a tribute to Winifred Holtby, who passed away in 1935.

In 1944, she published Seeds of Chaos, a work that spoke out against World War II. Testament of Experience, another memoir published in 1957, chronicles the years between 1925 to 1950.

Brittain was quite a prolific author of nonfiction in addition to her autobiographical series and a smaller number of novels. One of these was a book about Radclyffe Hall‘s trials. A selection of nonfiction works are listed toward the end of this post.

Pacifism

In the 1920s, Brittain was a frequent speaker at events for the League of Nations Union, and she spoke at a peace rally with Dick Sheppard in 1936. In 1937, she joined the Peace Pledge Union and the Anglican Pacifist Fellowship.

In the 1930s, she regularly contributed articles to Peace News, a pacifist magazine. After the outbreak of World War II, she wrote a series entitled Letters to Peacelovers and worked as a fire warden. Brittain later became an editorial board member for Peace News, writing articles against colonialism and apartheid.

Later years and legacy

After being injured in a fall in November 1966, Brittain’s health slowly declined. She passed away in Wimbledon at the age of 76 on March 29, 1970. As requested in her will, Vera’s ashes were scattered over her brother’s grave in Italy.

Brittain’s work helped people of later generations understand World War I through her eyes. To this day, her writings inspire others to work for peace.

Testament of Youth, her most famous literary contribution, was made into a feature film in 2014. Plaques mark the locations of her former homes in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Buxton, and London, and a promenade in Hamburg, Germany is named for her.

. . . . . . . . .

Vera Brittain page on Amazon*

More about Vera Brittain

Major Works

Poetry

Verses of a V.A.D. (1919)

Poems of the War and After (1934)

Memoir

Testament of Youth: An autobiographical study of the years 1900-1925 (1933)

Testament of Experience: An autobiographical story of the years 1925-1950 (1950)

Testament of Friendship: The Story of Winifred Holtby (1940)

Novels

The Dark Tide (1923)

Anderby Wold (1923)

Honourable Estate (1936)

Born 1925: A Novel of Youth (1949)

Nonfiction (highly selected)

Women’s Work in Modern England.(1928)

Halcyon; or, The future of monogamy (1929)

Thrice a Stranger (1938)

Humiliation with Honour (1943)

Seeds of Chaos: What mass bombing really means. (1944)

On Becoming a Writer (1947)

Search after Sunrise. London: Macmillan (1951)

Lady into Woman: A history of women from Victoria to Elizabeth II (1953)

The Women at Oxford: A fragment of history (1960)

The Rebel Passion: A short history of some pioneer peacemakers (1964)

Radclyffe Hall: A case of obscurity (1969)

More information and sources

All Poetry

Reader discussion of Vera Brattain’s works on Goodreads

Wikipedia

Losing Her First Love Haunted My Mother All Her Life

Papers of Vera Brittain at the Bodleian Library, Oxford University

Biographies and letters

Chronicle of Youth: The War Diary, 1913 – 1917, ed. by Alan Bishop with Terry Smart (1981)

Testament of a Generation: The journalism of Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby ,

ed. by Paul Berry & Alan Bishop London (1985)

Vera Brittain by Hilary Bailey (1987)

Letters from a Lost Generation, ed. by Alan Bishop and Mark Bostridge (1998)

Vera Brittain: A Life, by Paul Berry and Mark Bostridge (1995, 1996, 2001, 2008)

Vera Brittain: A Feminist Life, by Deborah Gorham, (2000)

Vera Brittain and the First World War, by Mark Bostridge (2014)

Film adaptations

Testament of Youth (2014)

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Vera Brittain appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 17, 2020

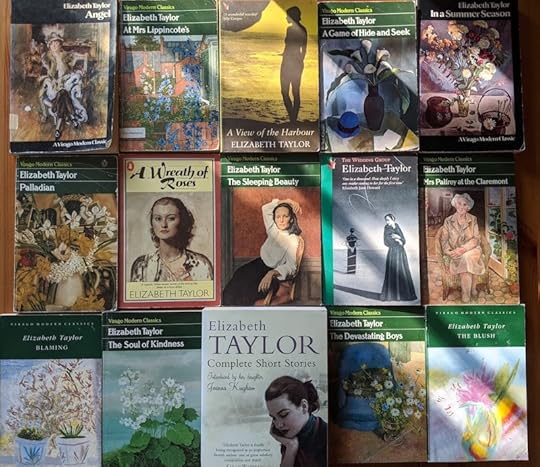

Elizabeth Taylor

Elizabeth Taylor (July 3, 1912 – November 19, 1975) was a British novelist and author of short stories who is generally acknowledged to be underrated — a brilliant writer who deserves to be more widely read. She is not to be confused with the iconic actress with the same name.

Writers as distinct as Antonia Fraser, Barbara Pym and Kingsley Amis admired her work, which are filled with both impassioned and lonely characters.

Upbringing and Education

In 1912, she was born Dorothy Betty Coles in Reading England. She wouldn’t begin to refer to herself as Elizabeth until the early 1930s. As a child, she was very close to her mother, Elsie May Fewtrell. Her father, Oliver, was an insurance inspector.

In September 1923, Betty attended Abbey School, a well-known Christian school. Although she would later become an atheist). She struggled with mathematics but received 99% on an English paper, which was the highest mark ever received by an Abbey School student (the one percent deducted to acknowledge that everyone’s handwriting could stand improvement.

Betty officially completed school in Berkshire in July 1930 but actually had finished before the previous Christmas. Even then, at seventeen, she aspired to write. She would write about this later, in a 1951 issue of The Bookclub Magazine: “I wanted to be a novelist, but it is not easy suddenly to be that at 17. I spent a year trying to write, despairing.”

Early reading and writing

As a child, the first full-length book Betty read was Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (a book which also had a profound impact on American writer Natalie Babbitt).

She also read (and reread) the Bastable books by E. Nesbit and she enjoyed collecting comic versions of classic stories by Victor Hugo, Jules Verne, and Wilkie Collins.

As an older girl, she read Crime and Punishment, and biographer Nicola Beauman notes that Betty’s Commonplace Book, encompassing 1928 through 1936, also includes other specific works, like The Waves and To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf and Persuasion by Jane Austen.

Other authors were also recorded: Katherine Mansfield, Siegfried Sassoon, William Butler Yeats, Edward Thomas, D. H. Lawrence, Thomas Mann, and Richard Church.

As a young woman, Elizabeth often borrowed books from the Boots Libraries and, after briefly working as a governess elsewhere, she worked as a librarian under their auspices, first in Maidenhead, then in High Wycombe.

After her own work had been published, years later, Elizabeth identified specific authors as having been influential for her development as a novelist and short story writer.

The works of Jane Austen, E.M. Forster, Anton Chekhov, and Virginia Woolf were particularly important, along with Samuel Richardson, Henry Fielding, and Ivan Turgenev. Throughout her life, she would reread Jane Austen regularly: her Martin Secker set was faded and worn from frequent use.