Nava Atlas's Blog, page 63

September 19, 2019

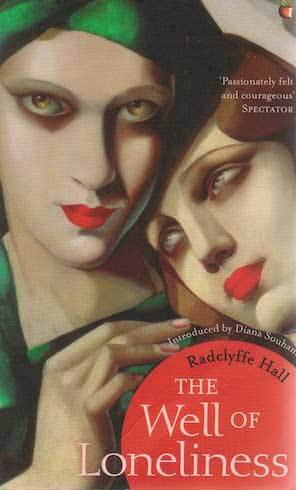

A Jane Austen-Inspired Cocktail from Gin Austen by Colleen Mullaney

Gin Austen: 50 Cocktails to Celebrate the Novels of Jane Austen by Colleen Mullaney is a clever little book celebrating the exquisite novels of Jane Austen with boozy delicacies and attendant wordplay. From the publisher:

In six enduring novels, Jane Austen captured the fancies and foibles of Regency England, and this book celebrates the picnics, luncheons, dinner parties, and glamorous balls of Austen’s world. Learn what she and her characters might have imbibed, and what tools, glasses, ingredients, and skills you simply must possess.

Raise your glass to Sense and Sensibility with a Hot Barton Rum or Elinorange Blossom. Toast Pride and Prejudice with a Salt & Pemberley, Fizzy Miss Lizzie, or Cousin Collins. Brimming with enlightening quotes from the novels and Austen’s letters, beautiful photographs, period design, and a collection of drinking games more exciting that a game of whist, this intoxicating volume is a must-have for any devoted Janeite.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Recipe and text following is from Gin Austen by Colleen Mullaney ©2019, Sterling Epicure, NY, reprinted by permission.

From Chapter II of Gin Austen: Pride and Prejudice

When a wealthy young gentleman by the name of Mr. Bingley moves into Netherfield Park, the grand manor at the end of the lane, the lives of the Bennett sisters change forever. Bingley brings with him his best friend, the dashing and wealthy but also rather disagreeable Mr. Darcy.

Miscommunication, heartache, and of course proposals ensue as all attempt to satisfy the laconic epigram that opens the novel that a rich, single man must by definition be looking to secure a marriage for himself. If you do marry into a superior class, the situation calls for sparkling wine, as does the recipe for Gin & Bennet.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Gin & Bennet

Mrs. Bennet is a prattling gossip of a mother and a constant embarrassment to her daughters. She fails to present herself well, and her children cannot prevent her from trying to marry them all off—the focus of her every waking moment. When Jane goes to visit the Bingleys for dinner, Mrs. Bennet refuses to let her use the carriage—despite anticipated poor weather—secretly hoping that the storm will hold Jane hostage at Netherfield. The rise works only too well.

1 ½ ounces gin

½ ounce crѐme de violette

½ ounce lemon juice

Sparkling wine

Edible blossoms for garnish

In a shaker filled with ice, combine the gin, crѐme de violette, and lemon juice and shake well. Strain into a coupe, and top with sparkling wine. Garnish with edible blossoms, and for heaven’s sake, take the carriage.

. . . . . . . . .

“If I were as rich as Mr. Darcy,” cried a young Lucas … ‘I should not care how proud I was. I would keep a pack of foxhounds, and drink a bottle of wine a day.’

Then you would drink a great deal more than you ought,’ said Mrs. Bennet; ‘and if I were to see you at it, I should take away your bottle directly.’” — Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

. . . . . . . . .

Gin Austen by Colleen Mullaney is available on Barnes&Noble.com,

Amazon, and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post A Jane Austen-Inspired Cocktail from Gin Austen by Colleen Mullaney appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 16, 2019

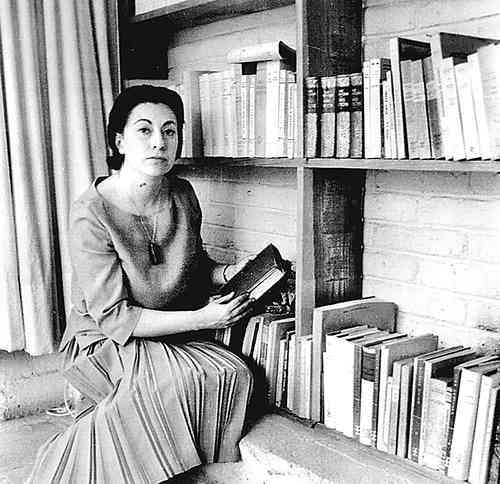

Rosario Castellanos

Rosario Castellanos (born Rosario Castellanos Figueroa; May 25, 1925 – August 7, 1974), author, poet, and diplomat, was one of Mexico’s most influential literary voices of the twentieth century. Her work examined issues of culture and gender in her home country, and went on to influence contemporary Mexican feminist theory and cultural studies.

Castellanos was born in Mexico City and raised near her family’s ranch in Comitán in the southern state of Chiapas near the Guatemalan border. She was quite shy as a child and never completely felt part of her family. A soothsayer once told her mother that one of her two children would die, and she screamed, “Not the boy!”

Her family, who once owned a big portion of land, lost much of it due to land reform and peasant emancipation policy enacted by President Lázaro Cárdenas in 1941. After being negatively impacted by the new land reform, Castellanos moved back to Mexico City with her parents at the age of fifteen. In 1948, both of her parents died within one month, compelling her to fend for herself.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Education

The death of her parents and the poem Endless Death by José Gorostiza marked the start of her writing career and becoming a cultural critic. She enrolled at UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico) to study law, philosophy, and literature.

Castellanos joined the National Indigenous Institute, where she wrote scripts for puppet shows. Coincidentally, the Institute was founded by the very person who took her family’s land away — President Cárdenas.

During this period, she also wrote a weekly column for a newspaper called Excélsior. After leaving UNAM, she transferered to the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters. She also began spending time with Nicaraguans, Guatemalans, and other Mexicans. This group would later become writers who would be known as “The 1950 Generations.” It was in 1950 that she earned her master’s degree in philosophy.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

New Beginnings

In 1958, Castellanos married Ricardo Guerra Tejada, a professor of philosophy. Together they had a son named Gabriel Guerra Castellanos (currently a political scientist), born in 1961. Before the birth of her son, she suffered from depression after having numerous miscarriages. Gabriel’s birth was monumental and gave her a new outlook on life.

Her marriage to Guerra ended after thirteen years as a result of his unfaithfulness. By this time, she had experienced an immense amount of heartbreak and depression, but didn’t allow anything to hinder her work. She dedicated much effort to defending women’s rights, which would eventually earn her a place as an important symbol of Latin American feminism.

In addition to her writing endeavors, Castellanos held many governmental posts and was appointed ambassador of Mexico to Israel in 1971. After her divorce, she yearned for a change for her and her son, and welcomed the position.

While in Tel Aviv, Israel, she also taught Latin American Literature at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and published several essays, short stories, and even wrote a play.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Themes in Rosario Castellanos’ writing

Castellanos’ poetry is deeply Catholic. She admired the work of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, the Mexican nun-poet of the seventeenth century, and Saint Teresa of Ávila, the Spanish sixteenth-century religious activist and author. Her poetry expresses social injustices and admiration for the creator of nature and is considered both powerful and authentic. Identity and the spirit of her home state of Chiapas are themes of her poetry, and she wrote of the women’s rights movement in Mexico.

Though all of Castellanos’ works are powerful and original, her most famous novel, Oficio de tinieblas (The Book of Lamentations) published in 1962, is regarded as her most moving piece. The novel re-creates an Indian rebellion that happened in the city of San Cristobal de las Casas in the nineteenth century. Castellanos sets the story in the 1930s, the period in which her family suffered from reforms at the start of the Mexican Revolution.

. . . . . . . . . .

Rosario Castellanos page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

Awards and Honors; the legacy of Rosario Castellanos

In 1958, Castellanos received the Chiapas Award for her novel Balún Canán.

Two years after receiving the Chiapas Award, she was awarded the Xavier Villaurrutia Award for Ciudad Real in 1960.

In 1962, Castellanos was awarded the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Award.

In 1967, she was awarded the Carlos Trouyet Award of Letters.

In 1972, Castellanos was given the Elias Sourasky Award of Letters.

In Mexico City, a park and a public library are named after her in the A park located in the borough Cuajimalpa de Morelos.

In UNAM, the library of the Center of Research and Gender Studies is named after her. Also, one of the gardens of the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters is named after her as well.

In Colonia Condesa, Mexico City, the headquarters of the Economic Culture Fund bears her name.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

An unexpected death

On August 7, 1974, Castellanos died in Tel Aviv at the young age of forty-nine. Though her death was determined to be an accident, some, including Mexican writer Martha Cerda, believe her death was a suicide.

Cerda wrote to journalist Lucian Kathmann, “I believe she committed suicide, though she already felt she was dead for some time.” There is no evidence to support the theory of suicide.

. . . . . . . . . .

Major works

Balún-Canán Fondo de Cultura Economica (1957; 2008)

Poemas (1953–1955)

Ciudad Real: Cuentos (1960)

Oficio de tinieblas (1962)

Álbum de familia (1971)

Poesía no eres tú; Obra poética (1948–1971)

Mujer que sabe latín . . . (1973)

El eterno femenino: Farsa (1973) (1964)

Bella dama sin piedad y otros poemas (1984)

Los convidados de agosto (1964)

Declaración de fe (2012)

Cartas a Ricardo (1994)

Rito de iniciación ( 1996)

Sobre cultura femenina (2005)

Biographies

Remembering Rosario: a Personal Glimpse into the Life and Works of Rosario Castellanos

by Oscar Bonifaz Caballero, and Myralyn Frizzelle Allgood (1990)

A Rosario Castellanos Reader by Rosario Castellanos, Maureen Ahern (Translator) (2010)

More information and sources

Wikipedia

Britannica

LifePersona

Isinsight

Feminize Your Canon: Rosario Castellanos

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Rosario Castellanos appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 13, 2019

Quotes from Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand

Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand (1905 – 1982) is a 1957 novel by the controversial author known for her Objectivist philosophy. Atlas Shrugged was her fourth and longest novel, her last major work of fiction, and the one she considered her magnum opus. She went on to focus on nonfiction after its publication. Here we’ll explore a selection of quotes from Atlas Shrugged that give a taste of its style and substance.

The novel takes place in a version of the United States where private businesses are suffering due to harsh regulations and laws. Lovers Dagny Taggart and Hank Reardon struggle to fight against looters who are aiming to profit from their productivity.

In their struggle to protect their business, they discover that a strange man named John Galt is attempting to persuade other business owners to leave their companies as a strike against the looters. Towards the end of the novel, the strikers use Galt’s philosophy of reason and individualism to create a new capitalist society.

Though reviewers have always been mixed on the book’s literary merits, Atlas Shrugged was rated No. 1 by Modern Library’s 1998 online poll and number twenty out of one hundred novels in 2018 by PBS Great American Read television series.

Rand used this novel to share her ideas on free enterprise, competition, money and love. Though it did receive a large number of negative and rather sarcastic reviews after being published, it also earned lasting popularity and had ongoing sales in the following years. Today, the novel is still making appearances in the classroom as the Ayn Rand Institute donates four-hundred thousand copies to high school students each year.

. . . . . . . . . .

An original 1957 review of Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand

. . . . . . . . . .

“Do not let your fire go out, spark by irreplaceable spark in the hopeless swamps of the not-quite, the not-yet, and the not-at-all. Do not let the hero in your soul perish in lonely frustration for the life you deserved and have never been able to reach. The world you desire can be won. It exists … it is real … it is possible … it’s yours.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If you don’t know, the thing to do is not to get scared, but to learn.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“We are on strike against martyrdom—and against the moral code that demands it. We are on strike against those who believe that one man must exist for the sake of another. We are on strike against the morality of cannibals, be it practiced in body or in spirit. We will not deal with men on any terms but ours—and our terms are a moral code which holds that man is an end in himself and not the means to any end of others.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“To the extent to which a man is rational, life is the premise directing his actions. To the extent to which he is irrational, the premise directing his actions is death.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“People think that a liar gains a victory over his victim. What I’ve learned is that a lie is an act of self-abdication, because one surrenders one’s reality to the person to whom one lies, making that person one’s master, condemning oneself from then on to faking the sort of reality that person’s view requires to be faked …The man who lies to the world, is the world’s slave from then on …There are no white lies, there is only the blackest of destruction, and a white lie is the blackest of all.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I swear by my life and my love of it that I will never live for the sake of another man, nor ask another man to live for mine.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I started my life with a single absolute: that the world was mine to shape in the image of my highest values and never to be given up to a lesser standard, no matter how long or hard the struggle.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“All that which is proper to the life of a rational being is the good; all that which destroys it is the evil.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A man’s sexual choice is the result and the sum of his fundamental convictions … He will always be attracted to the woman who reflects his deepest vision of himself, the woman whose surrender permits him to experience a sense of self-esteem. The man who is proudly certain of his own value, will want the highest type of woman he can find, the woman he admires, the strongest, the hardest to conquer — because only the possession of a heroine will give him the sense of an achievement.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Never think of pain or danger or enemies a moment longer than is necessary to fight them.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Devotion to the truth is the hallmark of morality; there is no greater, nobler, more heroic form of devotion than the act of a man who assumes the responsibility of thinking.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Let me give you a tip on a clue to men’s characters: the man who damns money has obtained it dishonorably; the man who respects it has earned it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She did not know the nature of her loneliness. The only words that named it were: This is not the world I expected.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I never found beauty in longing for the impossible and never found the possible to be beyond my reach.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“What greater wealth is there than to own your life and to spend it on growing? Every living thing must grow. It can’t stand still. It must grow or perish.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“He was seeing a long line of men stretched through the centuries from Plato onward, whose heir and final product was an incompetent little professor with the appearance of a gigolo and the soul of a thug.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The only proper purpose of a government is to protect man’s rights, which means: to protect him from physical violence. The only proper functions of a government are: the police, to protect you from criminals; the army, to protect you from foreign invaders; and the courts, to protect your property and contracts from breach or fraud by others, to settle disputes by rational rules, according to objective law.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“But he still thought it self-evident that one had to do what was right; he had never learned how people could want to do otherwise; he had learned only that they did.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Existence is Identity, Consciousness is Identification.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Logic rests on the axiom that existence exists. Logic is the art of non-contradictory identification.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

“Since life requires a specific course of action, any other course will destroy it. A being who does not hold his own life as the motive and goal of his actions, is acting on the motive and standard of death.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“By the grace of reality and the nature of life, man—every man—is an end in himself, he exists for his own sake, and the achievement of his own happiness is his highest moral purpose.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The moral is the chosen, not the forced; the understood, not the obeyed. The moral is the rational, and reason accepts no commandments.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Reality is that which exists; the unreal does not exist; the unreal is merely that negation of existence which is the content of a human consciousness when it attempts to abandon reason. Truth is the recognition of reality; reason, man’s only means of knowledge, is his only standard of truth.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A process of reason is a process of constant choice in answer to the question: True or False? — Right or Wrong?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“That which you call your soul or spirit is your consciousness, and that which you call ‘free will’ is your mind’s freedom to think or not, the only will you have, your only freedom, the choice that controls all the choices you make and determines your life and your character.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“This, in every hour and every issue, is your basic moral choice: thinking or non-thinking, existence or non-existence, A or non-A, entity or zero.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“All that which is proper to the life of a rational being is the good; all that which destroys it is the evil.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“To exist is to be something, as distinguished from the nothing of non-existence, it is to be an entity of a specific nature made of specific attributes.”

. . . . . . . . . .

More on the life of Ayn Rand

. . . . . . . . . .

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 10, 2019

Women’s Weird: Strange Stories by Women, 1890 – 1940

Just in time for settling in with a good book in front of the fireplace (or wood stove, or what the heck, even your radiator) on a stormy night, Handheld Press Ltd., based in Bath, England (onetime home of Jane Austen) will be publishing Women’s Weird: Strange Stories by Women, 1890 – 1940. This deliciously thrilling collection will be released, appropriately, on Halloween, October 31, 2019.

Edited by Melissa Edmundson, this compilation of strange tales by women authors — including some lesser-known gems by some of the classic authors on this site — will be of great interest to readers of literary ghosts stories, the supernatural, and other kinds of thrillers. From the publisher:

“Early Weird fiction embraces the supernatural, horror, science fiction, fantasy and the Gothic, and was explored with enthusiasm by many women writers in the United Kingdom and in the U.S. Melissa Edmundson has brought together a compelling collection of the best Weird short stories by women from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, to thrill new readers and delight these authors’ fans.”

Among the authors in this collection who are featured on this site are:

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, author of ‘The Yellow Wallpaper,’ with her story of a haunted New England house, ‘The Giant Wistaria’ (1891).

Edith Nesbit, best known for her children’s fiction as E. Nesbit, her horror story ‘The Shadow’ (1910) is about the dangers of telling a ghost story after the excitement of a ball.

Edith Wharton, the chronicler of New World societal fracture and change by new money tells an alarming story of Breton dogs and a jealous husband, ‘Kerfol’ (1916).

. . . . . . . .

Women’s Weird will be published by Handheld Press on October 31, 2019.

It’s currently available for order on the publisher’s website, and will be available

in Kindle and Kobo editions in the near future. Watch for an update!

. . . . . . . .

Then, there are also a number of authors that merit further exploration:

May Sinclair, the Edwardian feminist novelist tells the story of ‘Where Their Fire Is Not Quenched’ (1927), about a love that will never, ever die.

Mary Butts, modernist poet and novelist, wrote ‘With and Without Buttons’ (1938), a story of some very haunted gloves.

D K Broster, best known for her historical novels, tells an unholy story of a mistress’s feathery revenge, ‘Crouching At The Door’ (1942).

Rounding out the collection are stories by Francis Stevens, Elinor Mordaunt, Margery Lawrence, Eleanor Scott, and Margaret Irwin.

What is weird fiction?

In her Introduction to Women’s Weird, Melissa Edmundson, the editor of this collection, explains that “The darker side of human nature and its own revenants – jealousy, greed, ambition, morbid curiosity, and prejudice – are at the heart of these narratives.” and elaborates:

“ … Scholars have debated over what Weird fiction actually is and which writers should be credited with writing it. Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, in their collection The Weird (2011), continue in the tradition of Lovecraft, Scott, and Butts, remarking, ‘The Weird acknowledges that our search for understanding about worlds beyond our own cannot always be found in science or religion and thus becomes an alternative path for exploration of the numinous.’

… The VanderMeers provide one of best summations of the Weird, precisely by focusing on the indefinability of the term: ‘The Weird is as much a sensation as it is a mode of writing, the most keenly attuned amongst us will say ‘i know it when i see it’, by which they mean ‘i know it when i feel it’. every fan of the Weird does indeed know this feeling – the feeling of something being ‘off,’ not quite right.”

When I read this last statement, it brought to mind the work of Shirley Jackson. The women in this collection are those upon whose shoulders she stood, much as Jackson subsequently influenced a new generation of writers in related genres. Edmundson elaborates about the themes, issues, and anxieties related specifically to Weird literature by women:

“The stories included in Women’s Weird showcase a wide variety of themes and represent the various ways women interpret the Weird in their writing. some themes are connected to real world social concerns that become even more frightening when placed in a Weird context. Claustrophobic spaces, nightmarish worlds, and otherworldly entities come to represent traumatic pasts that are impossible to escape.

Other stories reach beyond specific cultural issues to take on universal human fears and the dark inner selves that we try to overcome and keep hidden. The shadow in the corner, the possessed object, the almost-human creature: all these manifestations lay bare our shared fears and anxieties.”

. . . . . . . .

One of the entries in Women’s Weird is “The Giant Wistaria;”

here’s an analysis of this story by Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Women’s Weird: Strange Stories by Women, 1890 – 1940 appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 8, 2019

The Sundial by Shirley Jackson (1958)

The Sundial by Shirley Jackson (1916 – 1965) was this prolific American author’s fourth novel, published in 1958. It was generally well received, though she had not reached the peak as a novelist. She was, though, already famous for her iconic short story, “The Lottery,” and her amusing memoirs of prettied-up domestic life.

After the publication of her masterpiece novels, The Haunting of Hill House (1959) and We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962) Jackson struggled with writer’s block and agoraphobia, as well as a host of physical ailments. She died at age 48, a victim of poor health and habits.

A 1958 Chicago Tribune review called The Sundial “entertaining, absorbing, and disturbing,” and encapsulated the plot succinctly:

An oddly assorted group dwells in the Halloran mansion, on a vast, walled estate. It is dominated ruthlessly by Mrs. Halloran, wife of the sickly heir of the founder, who may have murdered her own son to assure her control. Assorted relatives, a governess, and a young man of vague duties are the original entourage to which some random members are added.

To spinsterish Aunt Fanny, the founder’s daughter, a revelation is vouchsafed from her deceased father. The dreadful, fiery end of the world is imminent. All those in the safety of the father’s house will survive, to emerge to a new world.

Through successive revelations, the truth of this apocalypse impresses itself on all the group. The novel follows their preparations for the majestic even as the hour draws near. The suspense becomes great, the events are surprising, but how Miss Jackson plays out her end game is classified information.

A 1958 review of The Sundial by Shirley Jackson

From the original review by Robert Kirsch in The Los Angeles Times, February 21, 1958: Shirley Jackson’s The Sundial is bound to puzzle a great many readers and arouse some controversy as to its meaning. But this is to be expected from one of the great writers of parable of our time.

What most readers will appreciate, I fancy, is that she has turned from the Good Housekeeping type of humorous family chronicles Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons. Miss Jackson has too much talent and too much depth for these child-rearing adventures.

The Sundial suggests the technique and quality of Miss Jackson’s best-known short story, The Lottery. It is out of time and out of place, filled with mysterious hints, suggestions, and symbolism — and open to almost every kind of interpretation.

The story concerns a dozen residents of the Halloran mansion, built on a small rise of ground, its lands ringed by a stone wall. It was the property of Mr. Halloran, lately dead, “a man who in the astonishment of finding himself extremely wealthy, could think of nothing better to do with his money than set up his own world.”

He wanted the house endlessly decorated and adorned, the grounds meticulously cared for. “His belief about the the house, only very dimly conveyed to the architect, the decorators and landscapers and masons and hod carriers who put it together, was that it should contain everything.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson

. . . . . . . . . .

The other world, the one the Hallorans were leaving behind, was to be plundered ruthlessly for objects of beauty to go in and around Mr. Halloran’s house; infinite were the delights to be prepared for its inhabitants.

In the garden, “an inevitable focus was the sundial, set badly off center and reading WHAT IS THIS WORLD? In black gothic letters over the arched window on the landing was painted WHEN SHALL WE LIVE IF NOT NOW?

If the late Mr. Halloran could create the furnishings and design of his mansion world, he was somewhat less capable of determining the character of its population. The rule of it had gone to his thoroughly vicious daughter-in-law who was so jealous of her position that she is believed to have pushed her own son, Lionel, down the stairs to his death.

Lionel’s wife Maryjane is convinced that the old woman did it because “she couldn’t stand it if the house belonged to anyone else.” Lionel’s father is wheelchair-ridden and senile. He asks, “Is it Lionel who died?”

There are, in addition to the Hallorans, a select group of eccentrics. Most interesting and most eccentric is Aunt Fanny, the late Mr. Halloran’s daughter who is in touch with her father’s spirit and receives the message that the world outside the mansion is to be destroyed “from the sky and from the ground and from the sea … There will be a black fire and red water and the earth turning and screaming: this will come.”

To those in the house, the father’s message is: Tell them … that they will be saved. Do not let them leave the house; say to them: Do not fear, the father will guard the children.”

This is the first of the mysterious events, signs and omens which come upon the Halloran mansion: a snake, shining and full of light, appears in the living room; a guest comes to blackmail Mrs. Halloran; a rhinestone stickpin is jammed through her photograph in a voodoo touch.

If in outline the story appears unbelievable or too confusing, in Miss Jackson’s telling this is never an issue. She achieves Coleridge’s “willing suspension of disbelief” for the most grotesque, the most macabre elements. While you read, you believe.

After the entertainment you may try to puzzle out the meaning. Is it a political fable on internationalism vs isolationism? Is it a parable of the decay of an aristocracy? The answer is bound to vary. A novel such as this is a kind of literary Rorschach test. The right answer is the one which you provide for yourself.

. . . . . . . . .

The Sundial by Shirley Jackson on Amazon

. . . . . . . . .

The Sundial is reissued in 2014

Thank goodness Shirley Jackson’s works continue to be read and studied, so that her work isn’t relegated to the ash heap of forgotten midcentury literature. The Sundial was reissued in a Penguin Classics edition in 2014, along with another early novel by Jackson, The Bird’s Nest. In a review in The National Post (Toronto, Canada), March 1, 2014, Naben Ruthnum wrote:

“The Sundial belongs to the pre-apocalyptic genre, a small grouping of texts that lacks the bleak glamour and heroism of its post-apocalyptic cousin. In Jackson’s book, a baseless prophecy of the imminent end allows for the creation of a miniature world of belief, manipulation, and a gently ruthless struggle for power on the walled-in grounds of the Halloran mansion. The generations of women in the house are unwilling to leave the place they consider their birthright, and are equally unwilling to surrender control to each other.”

The reviewer goes on to comment on the sexual frustration demonstrated by the female protagonists as well as their mental fragility, a foreshadowing of Eleanor, the fragile heroine of The Haunting of Hill House. Ruthnum concludes:

“The characters in [Jackson’s] short stories and novels usually inhabit small towns in the eastern states, tiny communities with a mansion or two looming over little houses, all dredged in the Waspishness of the Vermont and Connecticut towns where Jackson lived with her children, pets, and her husband, the Jewish academic Stanley Hyman.

The family was rarely popular with their neighbors, who pulled charming pranks such as soaping swastikas onto the windows. The unease of a remarkable woman in the community that surrounds and despises or fears her, along with her own inability to leave a home and life she has become inextricably attached to — this is an abiding theme of Jackson’s life and work, the one that haunts these books.”

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Sundial by Shirley Jackson (1958) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 31, 2019

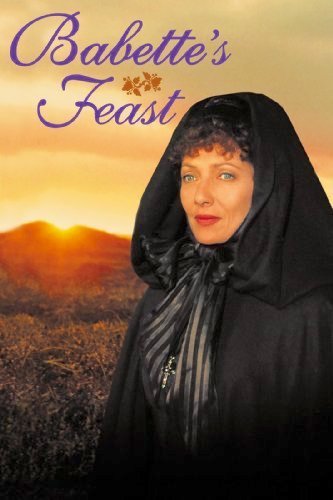

Babette’s Feast: The 1958 Short Story by Isak Dinesen, and the 1987 film

It may be fair to say that the acclaimed 1987 film, Babette’s Feast, is better known than the short story by Isak Dinesen upon which it’s based. In fact, it’s possible that fans of the film aren’t aware that it’s based on a short story by Dinesen, nor even anything about the author. So let’s say a few words about her first.

Isak Dinesen (1885 – 1962) was the nom de plume of the Danish author best known for her 1937 memoir Out of Africa, detailing her life as the owner of a coffee plantation in Kenya. Born Karen Christenze Dinesen into a family of aristocrats, merchants, and landed gentry, she was later known after marriage as Karen von Blixen-Finecke. The marriage, through which she became a Baroness, didn’t last, but it left her with the lifelong effects of syphilis.

Dinesen eventually had to give up the coffee plantation. She was above all else a storyteller, and her first book, Seven Gothic Tales (1934), was published soon after she returned to Denmark from Africa, broke, and alone. This collection of short stories was a surprise hit both in the U.S. and Europe. Short form fiction remained Dinesen’s mainstay throughout her writing career.

“Babette’s Feast” was originally published in the 1958 collection titled Anecdotes of Destiny. The other stories in the book are “The Diver,” “Tempests,” “The Immortal Story,” and “The Ring.” A typical review in the Wisconsin State Journal summed up the book’s charms, praising Dinesen’s skill in the short story genre:

“In a world where nothing is new, she thinks up new plots. In a world where styles merge and flatten out, hers maintains its unmistakable flavor. In a world where facts rules, she deals with fancy.” Indeed, it takes a consummate storyteller like Dinesen to dream up a tale like “Babette’s Feast.”

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Isak Dinesen

. . . . . . . . . .

A plot summary of “Babette’s Feast”

The film is extraordinarily true to the story, so this summary applies to both. The story takes place in a tiny, remote fictional town called Berlevaag, which sits at the base of a fjord in Norway. It looks “like a child’s toy-town of little wooden pieces painted gray, yellow, pink, and many other colors.”

Central to the story are two sisters, Martine and Philipa, the daughters of a Dean, the town’s religious leader, who founded a pious ecclesiastic party. At the start of the story we meet the two sisters, already aged, living in the house left to them by their father, and learn that they have “a French maid-of-all-work, Babette,” who “had come to that door twelve years ago as a friendless fugitive, almost mad with grief and fear.”

We then travel back in time to when Martine and Phillipa were extraordinarily beautiful young women, circa 1854. A young army officer named Lorens Loewenhielm had been sent by his angry father to stay with his aunt in Berlevaag, to straighten out his wayward habits and gambling debts. While there, he spotted Martine in the marketplace and fell in love immediately. For reasons he couldn’t quite understand, he was unable to communicate his feelings to her, and resolved to mend his ways and devote himself to building a stellar military career.

A year later, a great singer from Paris, Achille Papin, happened to be passing through Berlevaag. When he heard Philippa sing in church with the voice of an angel, he offered her father, free of charge, to allow him to give her singing lessons, secretly planning to introduce her to the world of opera in the wider world.

In the course of acting out Mozart’s opera, Don Giovanni, with Philippa, he kissed her. Awakened, perhaps, to a desire she didn’t want to face, she went to her father and told him that she no longer wanted singing lessons. Achille Papin, demoralized and regretful, took the first boat from Berlevaag.

Fifteen years after this incident, on a rainy night in June of 1871, “the mistresses of the house opened the door to a massive, dark, deadly pale woman …” who was, of course, Babette (the Dean had already passed away by this time). With this strange woman was a letter written in French, by Philippa’s would-be suitor, Achille Papin, explaining that Babette’s husband and son had been shot in violence of the Civil war taking place in France and she was also in mortal danger.

Papin implored them to take her in. The sisters, whose father had since died, lived simply and piously, and told her they couldn’t afford to employ her. Babette insisted that she would work for free, for “If they sent her away she must die.”

Babette, at first bewildered and forlorn, soon settled in and became a trusted figure, not only in the sisters’ little household, but among the townspeople. Twelve years passed in harmony, and Babette rarely referred to her life in France.

One day, though, Babette mentioned that she held a French lottery ticket that a friend had been renewing for her each year, hoping that one day she might win the grand prix of ten thousand francs.

The hundredth centenary of the Dean’s birth was approaching and the sisters wished to do something in honor of their father’s memory. They wished to include the townspeople who had been among his small flock of congregants. Ever fewer in number, aging, cranky, and harboring old grudges amongst themselves, the prospect was daunting:

“The sins of old Brothers and Sisters came, with late piercing repentance like a toothache, and the since of others against them came back with bitter resentment, like a poisoning of the blood.”

As their father’s hundredth birthday grew closer, Babette received a letter from France, the first she’d received in all the time she had lived in Berlevaag. She had won the ten thousand francs from the lottery ticket she had so long held out hope for.

The news spread, and all the townspeople were convinced that Babette would return to France. “Birds will return to their nests and human beings to the country of their birth.” The entire town lamented what they feared would be Babette’s imminent departure, for they had grown fond of her. The sisters dreaded the prospect most of all and wondered if Babette would at least remain with them through the fifteenth of December, the date of their father’s birthday.

On a September evening, Babette approached the sisters for a favor, imploring them to allow her to cook a dinner to celebrate the Dean’s birthday. The sisters, not having intended to serve more than a plain dinner with coffee, were taken aback. But they relented. There was just one more detail, though — Babette wished to pay for the dinner out of her lottery winnings. The sisters protested but Babette insisted, saying that in all the twelve years she had served them, she’d never asked for any other favor. And so, consent was given.

In November, Babette embarked on a journey, telling her mistresses that she needed a leave of a week to ten days to make preparations and buy goods for the celebration. In due time, she returned, and shortly thereafter, the goods she had purchased arrived in Berlevaag.

Wheelbarrow-loads of wine began to arrive at the little house, along with an enormous tortoise destined to become soup. There are details in this story that are gross for vegans like myself; there’s one gross-out detail that will disturb non-vegans as well. and in the film version, I had to shield my eyes during some of the food preparation scenes.

. . . . . . . . . .

Anecdotes of Destiny by Isak Dinesen on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

The day of the feast finally arrives, and with it, a steady snowfall. The guests, some dozen of them, began to arrive. Old Mrs. Lowenhielm, now ancient and deaf, was bringing her nephew, he who had so admired Martine, and was now a general and the husband of a lady-in-waiting in Queen Sophia’s court.

The table, covered in linen and laden with polished plates and multiple glasses, greeted the elderly Brothers and Sisters, as they were referred to, who had been followers of the Dean. A young redheaded lad assisted Babette, bringing forth one course after another of the most exquisitely prepared dishes. Wines were decanted, glasses kept full. The elderly celebrants, who usually spurned anything but the simplest of foods, were largely silent, eating and drinking everything that was put before them, course after abundant course.

But rather than grow heavy, “the convives grew lighter in weight and lighter of heart the more they ate and drank … It was, they realized, when man has not only altogether forgotten but has firmly renounced all ideas of food and drink that he eats and drinks in the right spirit.”

As the evening progressed, old grudges were forgiven, rifts were healed, and “time itself had merged into eternity.” The Dean’s daughters and the townspeople of Berlevaag experienced something that words were inadequate to describe. Babette’s feast was not only an incredible success, but something of a miracle.

And what of Babette? Was she going to return to her native France, as all feared and suspected? To say more would be something of a spoiler, but if you’ve read this far, you may as well know that the answer is no. However, there’s more to it than that, and that’s the miracle of this rich story, which in just over forty pages nearly achieves the depth of a novel.

. . . . . . . . . .

Watch Babette’s Feast (1987 film) on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

Babette’s Feast, the 1987 film

I have to admit that, much as I’d heard about the film, I’d not seen it until recently. I watched it just after reading the story, which, for me, was the perfect way to go. It’s often a disappointment to see a film interpretation after enjoying the original book version, but that wasn’t the case at all. The movie was the written story brought to life, amplifying it beautifully. And after seeing the film, I went back and read the story once again, now picturing the characters and settings more vividly and with greater understanding.

Out of Africa, the film based on Dinesen’s memoir, and starring Meryl Streep and Robert Redford, was an American production that came out in 1985. Babette’s Feast was the first of Isak Dinesen’s books to be produced in Denmark, and the first Danish film to win the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film (1987). The cast consisted of Danish, Swedish, and French actors.

The role of Babette was originally offered to renowned French actress Catherine Deneuve, but when she hesitated, the role went to another French actress, Stéphane Audran. The role of the sisters and their erstwhile suitors were performed by actors highly regarded in their native lands, yet virtually unknown to American audiences.

In addition to the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, Babette’s Feast won major awards in In Denmark, received a Cannes Film Festival special prize, and won several other awards. It’s a quiet, contemplative film that’s perfect for a winter evening. As mentioned earlier, pairing it with a reading of the story, either before or after, makes for a wonderful book-to-film (or film-to-book) experience.

Scene from Babette’s Feast, the 1987 film

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Babette’s Feast: The 1958 Short Story by Isak Dinesen, and the 1987 film appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 30, 2019

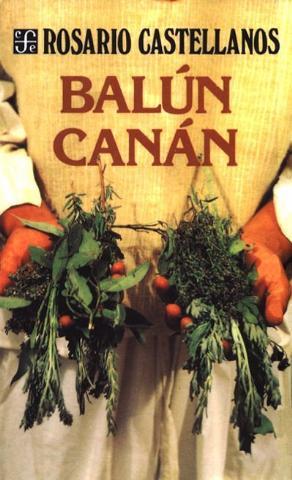

Radclyffe Hall

Radclyffe Hall (August 12, 1880 – October 7, 1943), British novelist and poet, is remembered as the author of groundbreaking lesbian literature. Her most enduring work is the controversial 1928 novel The Well of Loneliness. Hall’s struggles with love and identity worked their way into her fiction and contributed to a complicated, often unhappy life.

Born in Bournemouth, Hampshire, Marguerite Radclyffe Hall’s father was a wealthy Englishman with the unusual moniker Radclyffe Radclyffe-Hall, and her mother, Mary Jane Diehl, was American. Her parents’ marriage fell apart when she was quite young due to her father’s continuous philandering and her mother’s mental instability. Her mother’s remarriage to a professor of singing was also fraught with conflict, and young Marguerite was largely ignored.

Hall described herself as a “congenital introvert,” referring to an innate characteristic. The term comes from early 20th-century sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing and refers to a type of inborn gender reversal where women could be born with a masculine soul and vice versa. Though at the time the term referred more to homosexuality, the concept seems very much akin to what today is referred to as transgender.

Hall’s gender identity and love life informed her literary work. Given what we now know, it seems almost disrespectful to use the pronouns “her” and “she,” but since Hall has long been known in female terms, it would also seem odd to switch to masculine pronouns and perhaps confusing, in this context to use the more neutral “they” and “them.” So it is with apologies to the memory of Radclyffe Hall that we continue with the feminine pronouns.

Education and early works

Hall attended King’s College in London and afterward attended school in Germany. It was during these years that she began writing verses, which went on to be collected into five volumes of poetry in the first two decades of the 1900s. Twixt Earth and Stars (1906) and A Sheaf of Verses: Poems (1908) were among the first. One of her best-known poems, The Blind Ploughman, was set to music by Coningsby Clarke.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Love affairs

In 1907, Hall met Mabel Batten in a spa in Germany. At the time, Hall was twenty-seven and Batten was fifty-one, with a husband, daughter, and grandchildren. They fell in love, and after the death of Batten’s husband, the two committed to each other. During their relationship, Batten gave Hall the nickname John. She preferred this name for the remainder of her life.

In 1915, she fell in love with Batten’s cousin, Una Troubridge, a sculptor and wife of Vice-Admiral Ernest Troubridge. Within a year, Batten had passed away. Hall had her corpse embalmed with a silver crucifix on it that was blessed by the pope. She then moved in with Troubridge, despite the Church’s views on same-sex relationships. They lived in Kensington, London, and stayed together until Hall’s death.

Throughout Troubridge and Hall’s relationship, there were many other love affairs. For one, she fell in love with Evguenia Souline, a Russian émigrée, and had a long-term affair with her. Troubridge was aware of this affair and tolerated it, though not without pain.

. . . . . . . . . .

Una Troubridge and Radclyffe Hall

. . . . . . . . . .

First successes and a major literary prize

Much of Radclyffe Hall’s literary reputation rests on her best known novel, The Well of Loneliness, but her earlier books enjoyed a slew of successes in the years just preceding its publication. These included the novels The Forge, The Unlit Lamp, Adam’s Breed,

Following, a story in an American publication called the Independent Record (February 4, 1927) announces her winning a major literary prize called the Femina Prize, and outlines some of her background:

“This year’s award of the famous Femina Vie Heureuse prize, which is given each year by the leading French women’s magazine to the woman author of the best English novel published during the past twelve months, is of special interest to Americans.

The winner, Miss Radclyffe Hall, whose novel, Adam’s Breed, was published by Doubleday, Page and Company in 1926, is half American. Her book was entered in competition with Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes and Liam O’Flaherty’s The Informer.

Radclyffe Hall is the daughter of an English father and an American mother. While she has always made her home in England, she has spent much time in the U.S. Adam’s Breed, the novel which received this distinguished recognition in France, was her first to be published in America. It was her fourth to appear in England.

She received her first encouragement from the late William Heinemann, whose firm became her publishers. He was so interested in her early stories that he urged her to write a novel and promised to consider it for publication. Although he didn’t live to see his prophecy fulfilled, it was her wish to justify his faith in her. That kept her at work for three years on a first novel, The Unlit Lamp, which won her some reputation in London.

The tall, rather sever, exquisitely tailored Hall, with her hair cut close and brushed smoothly back from a face of almost Greek perfection in outline, looks anything but a sentimentalist. And her books will amply justify her appearance. But she confesses with amusement that at the tender age of three, she was a rank sentimentalist, bursting into lyrics before she knew how to spell.”

The Well of Loneliness

Hall’s most famous work, The Well of Loneliness (1928), features a lesbian from an upper class family in England. The main character, Stephen Gordon, lives in isolation with her partner Mary Llewellyn. They journey through a homosexual relationship during an era that rejected this expression of sexuality poses the setting and plot of the novel.

Receiving pushback from critics for her “sexually deviant” novel, Hall was swept into legal battles. Though at first widely banned, its notoriety helped push the narratives of lesbians in Western literature to the forefront. Hall made it clear to her publisher that she wanted the original text published, declaring:

“I have put my pen at the service of some of the most persecuted and misunderstood people in the world … So far as I know nothing of the kind has ever been attempted before in fiction.”

Surprisingly, The Well of Loneliness received more liberal treatment in American courts than it did in England. Justices dismissed charges of violation of Section 1141 of the Penal Law against Covici-Freide, Inc., American publishers of the book. The Court said:

“The book in question deals with a delicate social problem, which in itself cannot be said to be in violation of the law unless it is written in such a manner as to make it obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, or indecent, and tends to deprave and corrupt minds open to immoral influences.”

After Hall’s death in 1943, the ban on The Well of Loneliness was eventually overturned on appeal. Although she was vindicated by the American verdict, she steered clear of equal controversy in her subsequent literary works.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Quotes by Radclyffe Hall

. . . . . . . . . . .

Gender identity

Although Hall has long been described as a lesbian, it’s possible that she would have identified a trans man if that concept had been known during her time. She continued to call herself “John” after being given the nickname by her early lover, Mabel Batten. Hall nearly always dressed in suits and other men’s attire and used masculine notions to self-describe.

The Well of Loneliness is considered a trailblazing work of LGBTQ literature, though it has been criticized in some circles for portraying lesbian relationships as a rather heteronormative light. Still, it’s considered a classic. One can assume that Hall was using the protagonist to portray her sexuality and gender identity as she writes about wearing masculine clothing, having a masculine physique, and displaying masculine body language.

Other Awards and Honors

Hall was given the Gold Medal of the Eichelberger Humane Award in 1930. She was listed at number sixteen in the top 500 lesbian and gay heroes in The Pink Paper.

In 1930, Hall received the Gold Medal of the Eichenberger Humane Award. She was a member of the PEN club, the Council of the Society of Psychical Research, and a fellow of the Zoological Society.

Radclyffe Hall died of colon cancer in England at the age of 63 in the tiny town of Rye, East Sussex. She is buried at Highgate Cemetery in North London in the chamber of the Batten family, which includes Mabel, one of Hall’s early lovers.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Radclyffe Hall page on Amazon

More about Radclyffe Hall

On this site

The Well of Loneliness: Banned and on Trial for Obscenity

Quotes by Radclyffe Hall

Major Works

Novels

The Forge (1924)

The Unlit Lamp (1924)

A Saturday Life (1925)

Adam’s Breed (1926)

Miss Ogilvy Finds Herself (1926)

The Well of Loneliness (1928)

The Master of the House (1932)

The Sixth Beatitude (1936)

Poetry

Twixt Earth and Stars (1906)

A Sheaf of Verses: Poems (1908)

Poems of the Past & Present (1910)

Songs of Three Counties and Other Poems (1913)

The Forgotten Island (1915)

Rhymes and Rhythms (1948)

Biographies

Trials of Radclyffe Hall by Diana Souhami

Radclyffe Hall: A Life in the Writing by Richard Dellamora

Your John: The Love Letters of Radclyffe Hall by Joanne Glasgow

Radclyffe Hall: A Woman Called John by Sally Cline

Your John: The Love Letters of Radclyffe Hall by Joanne Glasgow

Radclyffe Hall at The Well of Loneliness: A Sapphic Chronicle by Lovat Dickson

Our Three Selves: The Life of Radclyffe Hall by Michael Baker

Noël Coward & Radclyffe Hall: Kindred Spirits by Terry Castle

More Information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Radclyffe Hall’s books on Goodreads

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Radclyffe Hall appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 25, 2019

10 Interesting Facts about the Brontë Sisters

It would be easy enough to compile interesting facts about the Brontë sisters each in her own right, but here we’ll look at the three together, since their lives were so intertwined. Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë, acknowledged literary geniuses, were close in age and with few exceptions, preferred one another’s company above anyone else’s.

The three Brontë sisters all cherished literary ambitions from an early age, and despite lives that were cut short by illness, secured a prominent place in the English literary canon.

The children of Maria Branwell Brontë and Reverend Patrick Brontë, the sisters were born in the West Yorkshire village of Thornton, England. They subsequently moved to Haworth, where they grew up along with their brother Branwell. Their mother died while the children were still very young, and their aunt Branwell moved in to help take care of them.

The young sisters were sent away to school with dire consequences

In 1824, Charlotte and her sisters Maria (their departed mother’s namesake), Elizabeth, and Emily were sent away from the Parsonage where they lived with their father and an aunt, to a school for daughters of the clergy in Cowan’s Bridge. Maria and Elizabeth fell ill while there and died of tuberculosis; Charlotte and Emily returned home.

It’s widely accepted that Charlotte modeled the Lowood school setting at the beginning of Jane Eyre on her experiences. She blamed the deaths of her sisters on the poor conditions at the school.

. . . . . . . . . .

Charlotte Brontë’s Quotes on Her Writing Life

. . . . . . . . . .

The Brontë siblings created imaginary worlds together

Charlotte, Emily, and Anne received little formal education after the Cowan’s Bridge school disaster. They, along with their brother Branwell, grew up creating an imaginary world called Angria. They put on plays, told stories, and created journals and magazines about the make-believe realm.

Anne and Emily, who remained closest to one another throughout their brief lives, also created Gondal, another fictional world comprised of four kingdoms. Of all the siblings, Emily had the most reticent and reclusive nature, so it’s not surprising that she took great comfort in creating and retreating to imaginary worlds.

At least two of the three sisters worked as governesses

Anne left home briefly to attend a boarding school while in her teens, and at age nineteen, began working as a governess. Her first novel, Agnes Grey, a young governess, is based on her experiences in this line of work, something she did for several years. The heroine’s story highlights the unrelenting hours, low pay, and accumulated humiliations that defined one of the only professions open to women.

Charlotte had returned to school in her teens, after which she worked as a teacher and then as a governess. Her most famous heroine, Jane Eyre, followed the same path. Emily’s occupation was at one point described as “future occupation, governess,” though it’s unclear that she worked at it for long, if at all. Leaving home for any length of time seemed to literally make her sick.

The sisters loathed the occupation of governess and didn’t relish the prospect of becoming teachers, either. All they had ever wanted was to write, as Charlotte put it, “We had very early cherished the dream of one day becoming authors.”

Charlotte and Emily studied briefly in Brussels

In 1842, Charlotte and Emily left the parsonage for Brussels, Belgium for the Pensionnat Héger. They studied French, German, and literature, thinking that it might prepare them to be teachers or start their own school in the future. While there, Charlotte fell in love with the married head of school, Constantin Héger. She became obsessed with him, in fact, in a rather unhealthy way.

Charlotte’s experiences were used in the thinly disguised first novel, The Professor, which was published only after her death. Her novel Villette was also inspired by this period of her life.

. . . . . . . . .

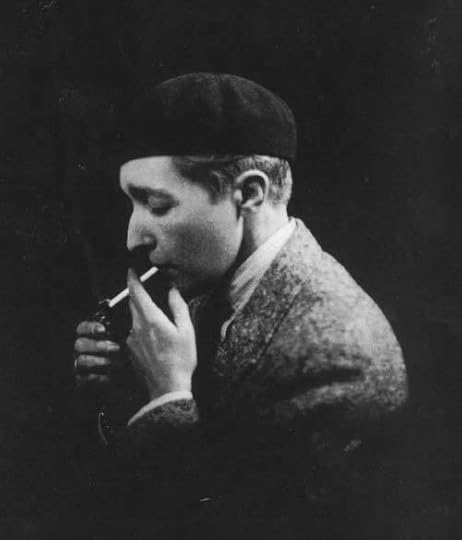

Self portrait by Branwell Brontë

. . . . . . . . .

They struggled with their drug- and alcoholic-addicted brother

Though the sisters cared deeply about their brother Branwell, he was a constant thorn in their side. Alcoholic and possibly addicted to opium, he was a failed poet and had trouble holding down positions. Anne based the antagonist in her novel The Tenant of Wildfell Hall in part on Branwell and his demons.

Branwell was a disappointment to everyone around him, but even more, to himself. He fancied himself an artist and a poet, but his efforts fame to naught. Undoubtedly that sense of perpetual failure drove him to drink and drugs.

The sisters published an unsuccessful book of poems

In the mid-1840s, Charlotte discovered a stash of Emily’s poems and recognized the genius in them. She spearheaded the task of finding a home for a collected book of poems by herself and her two sisters. They took noms de plume Currer, Ellis, and Acton (Charlotte, Emily, and Anne respectively, and shared the faux surname Bell.

The book, dryly titled Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell’s Poems, finally found a publisher willing to take it on. As was customary, the authors were required to front the money for its printing. It was published in 1846 to few (though positive) reviews and humiliating sales totaling two copies.

. . . . . . . . . .

No Coward Soul is Mine: 5 Poems by Emily Brontë

. . . . . . . . . .

Anne and Emily found a publisher before Charlotte did

After the bruising experience of publishing of the poetry book, the sisters resolved to send out manuscripts of their respective novels, also under their pseudonyms — Charlotte’s The Professor, Emily’s Wuthering Heights, and Anne’s Agnes Grey.

At the time — still in the 1840s — manuscripts were written by hand, so they could be submitted to only one publisher at a time. Charlotte’s novel was rejected by at least a half a dozen London publishers, each disappointment was a crushing blow.

Emily and Anne’s novels were both accepted by the same publisher, but not Charlotte’s. Meanwhile, though, she’d been working on Jane Eyre, and when another publisher rejected The Professor but asked to see a longer, more developed work, she had it at the ready. Jane Eyre was quickly sent to press and was an immediate sensation. Learn more about the Brontë sisters’ path to publication.

The three “Bells” were suspected of being the same person

Though Charlotte was the last to find a publisher, her novel, Jane Eyre, was the first to be published. Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey came out several months later. There was a persistent rumor that the authors of Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre were one and the same:

“It was said that this was an earlier and ruder attempt of the same pen which had produced ‘Jane Eyre,’” Charlotte wrote, “Unjust and grievous error! We laughed at it at first, but I deeply lament it now.” Newspaper coverage of the books seemed to reinforce the notion that Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell were the same person.

Charlotte and Anne were forced to travel to London to prove to Charlotte’s publisher that they were not the same person (Emily refused to join them) when Anne’s publisher sold The Tenant of Wildfell Hall to an American publisher under the false understanding that it was by the same author as the hugely successful Jane Eyre. Soon, the reading public accepted that the Bells were indeed three separate people; gradually, the sisters’ true identities came to light.

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from Agnes Grey and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë

. . . . . . . . . .

Charlotte was the only Brontë sibling that married

In 1839, Charlotte Brontë had declined a marriage proposal, writing: “I am not the serious, grave, cool-hearted individual you suppose; you would think me romantic and eccentric.” Anne may have at some point had a suitor that came to naught, but Emily barely wished to leave the parsonage.

Charlotte ultimately married Arthur Bell Nicholls, a curate in 1854. With her siblings all dead the marriage may have allayed the loneliness she must have felt living alone with her father in the parsonage. Her father bitterly opposed the marriage, though he gradually accepted it.

The marriage started happily but was tragically cut short. In 1855, Charlotte died at the age of thirty-eight, just a month shy of her thirty-ninth birthday, of complications due to pregnancy.

All the Brontës died tragically young

Branwell Brontë died at age thirty-one in September 1848, the official cause of death listed as “chronic bronchitis-marasmus,” a form of tuberculosis (then called consumption). His condition was surely aggravated by alcoholism and addiction to laudanum and opium.

Emily, who caught a chill at his funeral, died of tuberculosis barely three months later, at age thirty. Anne died in May of 1849, also of tuberculosis, age twenty-nine. And as mentioned above, Charlotte died several years later, nearly thirty-nine. Their father, Patrick Brontë, outlived all six of his children.

The post 10 Interesting Facts about the Brontë Sisters appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 24, 2019

10 Fascinating Facts About Toni Morrison, Nobel Prize Winner

Toni Morrison, born Chloe Ardelia Wofford (1931 – 2019), was an American novelist, editor, essayist, and professor. Widely remembered for her work and achievements, there’s much more about her eventful life that many readers may not be aware of. We’ll explore 10 fascinating facts about Toni Morrison that may give you a glimpse at what shaped her to become the woman and writer that we’ve come to know and love.

She was born and raised in Lorain, Ohio, in a working-class African-American family that influenced her love and passion for black culture as she grew up hearing folktales, songs, and storytelling.

Her work spoke to many as it was focused on the black American experience and the struggles that they face. After the creation of the notable works including The Bluest Eye (1970), Sula (1974), Song of Solomon (1977), Tar Baby (1981), and Beloved (1987), she received an abundance of awards, including the Nobel Prize in Literature (1993), the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and many more.

. . . . . . . . . .

25 Wise Quotes by Toni Morrison on Writing and Living

. . . . . . . . . .

Her love for literature started as a child

Morrison’s parents instilled a sense of heritage and language through folktales, ghost stories, and songs traditional to the African-American heritage. As a result, she developed a love for literature and read frequently as a child. She had many favorite authors, including Jane Austen and Leo Tolstoy.

Her childhood influenced her style of writing

Morrison started her writing career as an undergrad with a workshop at Howard University. Growing up, Morrison says that her family was “intimate with the supernatural” and that they frequently used visions and signs to predict the future.

Morrison’s parents made storytelling an important part of their household and was filled with storytelling among the children and the adults. As a result of her childhood, she felt that her writing was influenced by the storytelling in her past.

‘Toni’ was actually a nickname

At the age of 12, Morrison became a Catholic and took on the baptismal name Anthony after Anthony of Padua. Years later when Morrison was a student at Howard University, people had a hard time pronouncing the name Chloe. From then on, she started going by her nickname, Toni, to avoid any further confusion with pronunciation.

She didn’t believe she was a good mother

Morrison married Harold Morrison, an architect she met while studying at Howard University. They had two children but divorced in 1964, leaving her to care for two kids alone. She often felt as though she was not a good mother because she wanted to focus on her writing. “I did it ad hoc, like any working mother does,” she said.

She developed a habit of waking up at four in the morning to write, which led to the completion of her first novel, The Bluest Eye. Here is a recording of a 2015 interview on NPR’s Fresh Air, in which she spoke about the regrets she carried about her personal life.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Toni Morrison

. . . . . . . . . .

She never remarried after her first husband

Though she has never discussed the reason for her divorce, she hinted in the past that he wanted a more subservient wife. She said “he didn’t need me making judgments about him, which I did. A lot.” She never remarried after they parted ways.

Her father witnessed a lynching

Morrison’s father grew up in Cartersville, Georgia. At the age of 15, he witnessed white people lynching two black businessmen who lived on his street. Soon after the lynching, her father moved to Lorain, Ohio, a racially integrated town, in hopes of escaping racism and gain better employment in Ohio’s industrial economy rather than sharecropping.

Upon speaking of her father’s experience with the lynching, Morrison said “He never told us that he’d seen bodies. But he had seen them. And that was too traumatic, I think, for him.”

She was one of the first black editors at Random House

In 1965, Morrison started working as a fiction editor at Random House in Syracuse, New York and was among one of the very few black editors at the company. Few knew much about her extracurricular writing activities until she published The Bluest Eye in 1973.

After the publication of her book, Morrison said others at Random House “read the review in The New York Times.” She then said that “it got a really horrible review in The New York Times Book Review on Sunday, and then it got a very good Daily Review,” making her work known to a wider audience.

. . . . . . . . . .

Morrison receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1993

. . . . . . . . . .

She was the first African-American recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature

Morrison was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1993. She made history as the first African-American woman to receive the honorary prize. It was awarded to Morrison, “who in novels characterized by visionary force and poetic import, gives life to an essential aspect of American reality.”

When giving her Nobel speech, she used the power of storytelling to talk about a blind old black woman who is approached by a group of young people. They ask her, “Is there no context for our lives? No song, no literature, no poem full of vitamins, no history connected to experience that you can pass along to help us start strong?” Morrison then says, “Think of our lives and tell us your particularized world. Make up a story.”

A house fire damaged some of her manuscripts

The same year she was awarded the Nobel Prize (1993), Morrison’s home caught on fire in Grandview, N.Y. According to the Nyack Fire Department Chief Paul Wanamaker, about one hundred and twenty firefighters from two towns responded to a fire that was burning down an old four-story Colonial house. When Morrison went to inspect the damage, Wanamaker said that some of her manuscripts had gotten destroyed in the fire but had no further details.

She was the first African-American to hold a named chair at an Ivy League University

Among her other significant firsts, Morrison was also was the first to hold a named chair at an Ivy League University. In 1987, she was named the Robert F. Goheen Professor in the Council of Humanities at Princeton University in New Jersey.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

The post 10 Fascinating Facts About Toni Morrison, Nobel Prize Winner appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 22, 2019

Come Along with Me by Shirley Jackson (1968)

Come Along with Me is the novel Shirley Jackson (1919 – 1965) was working on at the time of her untimely death in 1965 at the age of forty-eight. This unfinished novel was collected in the book of the same title: Come Along with Me: Part of a novel, sixteen stories, and three lectures, and edited by Stanley Edgar Hyman, her husband at the time of her death.

Known for her stories and novels of psychological terror, including The Haunting of Hill House and We Have Always Lived in the Castle, Jackson didn’t leave behind a huge body of work but what she did produce was hugely influential.

Jackson also published two memoirs of motherhood and family life, Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons, believed to be highly idealized versions of the messy reality of the Jackson-Hyman brood in their ramshackle Vermont home. Nevertheless, these works, too, influenced a tradition of “momoirs” carried on by the likes of Jean Kerr and Erma Bombeck.

Notably, the Come Along with Me collection includes “The Lottery,” the short story that catapulted Jackson to fame (and notoriety), and with it, a transcript of a lecture Jackson gave about it called “Biography of a Story.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Shirley Jackson

. . . . . . . . . .

This description of Come Along with Me is from the 1968 Viking Press edition:

Come Along with Me is the title of the unfinished novel on which Shirley Jackson was working at the time of her death in 1965. A completed draft of the brilliant first section of that novel begins this posthumous collection of Jackson’s fiction and lectures as selected by her husband, Stanley Edgar Hyman, from pieces for the most part previously unpublished in book form.

Mr. Hyman has chosen a representative sampling of Jackson’s short stories, ranging from eerie encounters with the supernatural, as in “The Rock,” (on of five stories in the collection never before published anywhere) to lighthearted descriptions of “raising demons,” as in “Pajama Party.”

With characteristic deftness she pinpoints the idiosyncrasies of young women, repressed and precocious, of old women dreaming in their senility, of the understated but savage battle between country people and city interlopers.

Admirers of We Have Always Lived in the Castle will welcome further investigations into the mysterious effects of houses on people, in such tour de forces as “A Visit” and “The Little House.” The collection concludes with three lectures on the subject of writing, including another story about life in the Hyman ménage with which Jackson used to end her lecture on “Experience and Fiction.” Also included, as the focus for a lecture called “Biography of a Story” is “The Lottery,” perhaps her best known short story.

. . . . . . . . . .

Come Along With Me by Shirley Jackson on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

In his Preface to the 1968 Viking Press edition, Stanley Edgar Hyman wrote:

The fourteen short stories [in this collection] were chosen from about seventy-five not previously collected, as the best, or those best showing the range and variety of her work over three decades …

“Janice” must be one of the shortest short stories on record. Shirley Jackson wrote it as a sophomore at Syracuse University, and it was printed in Threshold, the magazine published by her class in creative writing. My admiration for it led to our meeting. I suppose that I reprint it to some degree out of sentiment, although in its economy and power it is surely prophetic of her later mastery.

The three lectures are those that Shirley delivered at colleges and writers’ conferences in her last years. “The Night We All Had Grippe” is printed after the lecture she used to conclude with a reading of it, although it appears as a section of Life Among the Savages; it gets somewhat lost in that book, and I find it the funniest pieces since James Thurbers’ My Life and Hard Times.

“The Lottery” is printed after the lecture that customarily concluded with it, because of the possibility, however remote, that there are readers unfamiliar with it.

. . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy:

The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson

. . . . . . . . .

The publisher’s description of Come Along With Me concludes: “The adjectives most often applied to Shirley Jackson’s fiction were haunting, eerie, bizarre, cryptic, and magical.” Jackson’s work showed her mastery of the psychological thriller. Today, her work might be deemed less shocking given how popular the genre remains. Her writerly craft was singular, judging by how many contemporary writers, including Stephen King and Neil Gaiman, point to her as an influence.

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Come Along with Me by Shirley Jackson (1968) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.