Nava Atlas's Blog, page 65

July 27, 2019

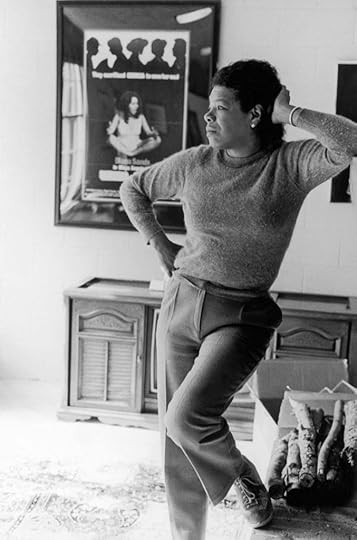

Ntozake Shange

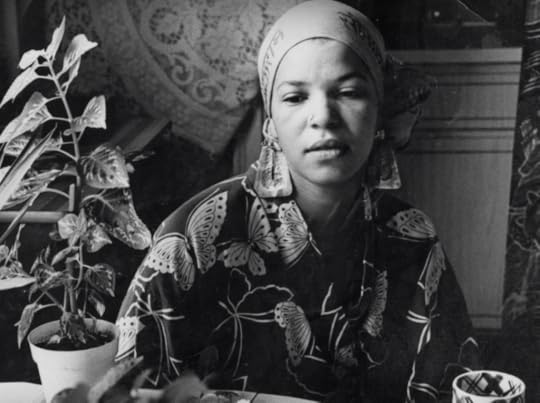

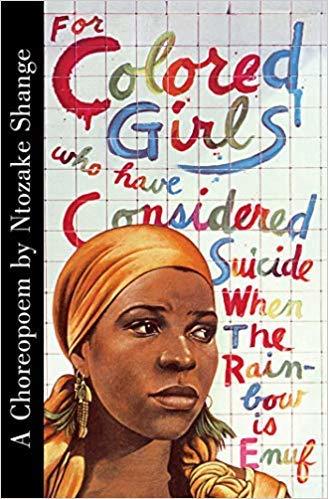

Ntozake Shange, born Paulette Linda Williams (October 18, 1948 – October 27, 2018), was an African American playwright, poet, and feminist. As a Black feminist, her work often shed light on issues relating to Black power, race, and gender. Among her many powerful works, she’s best known for the Obie Award-winning play, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf.

Born in Trenton, New Jersey, she was the oldest of four children in an upper-middle-class family. Her father, Paul T. Williams, was an Air Force surgeon, and her mother, Eloise Williams, was a psychiatric social worker and an educator. By the age of eight, her family left Trenton and moved to St. Louis, Missouri. In 1956, it was a racially segregated city that would later become one of the major influences in her work.

A Love for PoetryDue to the Brown v. Board of Education court decision, the young Paulette Williams attended a white school where she was horrifically exposed to racial attacks in exchange for a “quality” education. Though life at school was challenging, her family pushed her to find her artistic outlet, as they all had a strong interest in the arts.

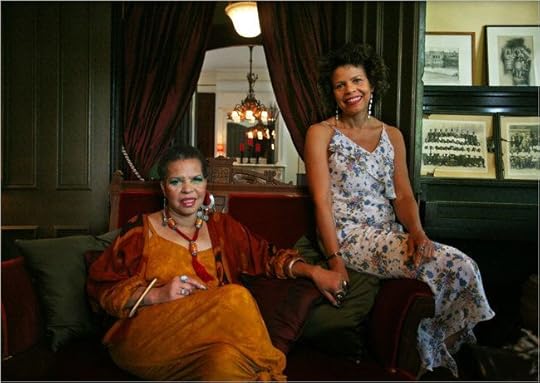

The Williams family had many admirable guests visit their home, including Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Chuck Berry, and W.E.B Du Bois. Ultimately, Paulette decided that she loved poetry. While still living in Trenton, she would attend poetry readings with her younger sister, Wanda, who is currently known as the playwright Ifa Bayeza. These poetry readings allowed the sisters to develop an interest in the South and the loss it represented for the Black youth who were forced to migrate to the North with their parents.

. . . . . . . . . .

Ntozake Shange (left) and her sister, Ifa Bayeza (right)

. . . . . . . . . .

She returned to Lawrence Township, Mercer County, New Jersey when she was thirteen and graduated from Lawrence High School. After graduating high school, she enrolled at Barnard College in 1966 where she met Thulani Davis, a fellow Barnard student, and would-be poet. The two would then go on to collaborate on numerous works soon after.

In 1970, she graduated cum laude with a degree in American Studies. She continued her education and went on to earn her master’s degree in the same field from the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Although she was very successful in her studies, she struggled emotionally in her personal life.

Ntozake Shange comes into beingShe married during her first year of college but the marriage did not last long. She was depressed over her divorce and developed feelings of bitterness and even alienated herself from others. At one point, things got so bad that she even tried to attempt suicide.

She started coming to terms with her feelings of alienation and depression in 1971, pushing her to change her name to Ntozake Shange. In Zulu, a Bantu language of the Zulus from South Africa, Ntozake means “she who comes with her things” and Shange means “who walks like a lion.”

She told Allan Wallach in Newsday that the reason for her name change was due to her belief that she was “living a lie,” saying, “[I was] living in a world that defied reality as most black people, or most white people, understood it–in other words, feeling that there was something that I could do, and then realizing that nobody was expecting me to do anything because I was colored and I was also a female, which was not very easy to deal with.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The start of a brilliant careerAfter earning her master’s degree, Shange moved back to New York City in 1975 and was acknowledged for being a founding poet of the Nuyorican Poets Cafe. That year, she also produced what would remain her best-known play, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow is Enuf. The play was first produced Off-Broadway and eventually moved to the Booth Theater on Broadway where it won multiple awards, including the AUDELCO Award, Outer Critics Circle Award, and the Obie Award.

For Colored Girls ... is a twenty-part choreopoem — a term that Shange coined to describe the groundbreaking and drama-filled play that combined multiple art forms, including poetry, dance, music, and song. The choreopoem was used to portray the harsh reality of the lives of women of color in America.

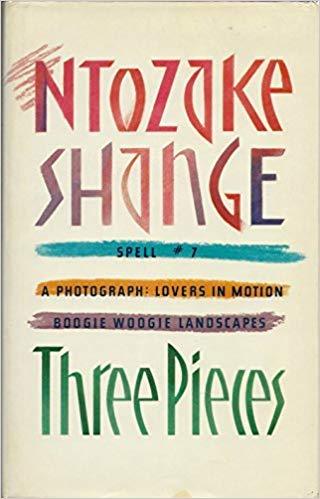

For Colored Girls ... was published in book form in 1977. That same year, she married musician David Murray, with whom she had a daughter, Savannah Thulani Eloisa, in 1981. The play later went on to be adapted into a film by Tyler Perry in 2010 called For Colored Girls, though it’s quite different than the staged version. Shange wrote other successful plays, such as Spell No. 7 (1979), another choreopoem that delves into the Black experience, and an adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage and Her Children. This work earned her another Obie Award.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Productive yearsIn addition to creating numerous successful choreopoems, Shange became an associate of the Women’s Institute for Freedom of the Press (WIFP) in 1978, an American nonprofit publishing organization that works to increase the communication between women and the public with women-based media.

She taught at the University of Houston in the Creative Writing Program from 1984 to 1986. While there, she wrote the ekphrastic poetry collection called Ridin’ the Moon in Texas: Word Paintings, and was the thesis advisor for poet and playwright Annie Finch. In 2003 she wrote and oversaw the production of Lavender Lizards and Lilac Landmines: Layla’s Dream while also serving as a visiting artist at the University of Florida, Gainesville.

Shange also wrote many individual poems, essays, and short stories that were published in various magazines and anthologies, including The Black Scholar, Ms. Essence Magazine, The Chicago Tribune, VIBE, Yardbird, and others.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The Black Arts MovementThe Black Arts Movement, known as BAM, is a subset of the Black Power Movement and has been described as the “radical reordering of the western cultural aesthetic” by Larry Neal. BAM’s key concepts are a “separate symbolism, mythology, critique, and iconology” along with the African American’s need for “self-determination and nationhood.” Many actors, actresses, choreographers, musicians, novelists, artists, and other public figures took part in BAM. Some of the most notable women who participated included Gwendolyn Brooks, Lorraine Hansberry, and Sonia Sanchez.

Described as a “post-Black artist,” Shange’s work was seen as feminist. Concerning the idea that BAM’s art was a “radical reordering of the western cultural aesthetic,” she described her work by saying “A play has a form that has to be finished. A performance piece has an organic form, but it can even flow. And there doesn’t have to be some ultimate climax in it. And there does not have to be a denouement.”

Shange set her writing apart from the usual writing style of the Black Arts Movement by creating a “special aesthetic” for black women “to an extent,” claiming that “the same rhetoric that is used to establish the Black Aesthetic, we must use to establish a women’s aesthetic.” She also went on to say that “the cycles of our lives that have been ignored for centuries in all castes and classes of our people, are to be dealt with now.”

Themes in Ntozake Shange’s work

Shange’s work incorporates a number of genres that address injustice, violence, and oppression. She used African American dialect and has been both criticized and admired for her unique writing style. She has also been applauded for her religious feminism and her stand on race and gender issues.

Her choreopoems, consisting of poetry, drama, and autobiography, have at times been criticized as one-sided attacks on black men. Though her work has received some backlash, it is also valued for its flair and lyricism.

. . . . . . . . . .

Ntozake Shange page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . . .

Awards and Honors; the legacy of Ntozake ShangeIn 1977, Shange was awarded the Off-Broadway Award, Outer Critics Circle Award, Audience Development Committee Award, Village Voice, Mademoiselle Award, and Antoinette Perry, Grammy, and Academy award nominations all for For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow is Enuf.

In 1978, Shange was awarded the Frank Silvera Writers’ Workshop Award. In 1981, The Los Angeles Times Book Prize was awarded to Shange for her Three Pieces. This year, she also won an Off-Broadway Award for Mother Courage and Her Children.

In 1992, Shange was awarded the Paul Robeson Achievement Award, the Arts and Cultural Achievement Award, and the National Coalition of 100 Black Women, Inc., Pennsylvania chapter.

. . . . . . . . . .

Photo: Marian Curtis/Shutterstock

. . . . . . . . . .

On the night of October 27, 2018, Shange died in her sleep at the age of seventy in an assisted living facility in Bowie, Maryland. Though she was ill and and had suffered strokes in 2004, she was still creating new work and giving readings.

Her sister, Ifa Bayeza, was quoted saying: “It’s a huge loss for the world. I don’t think there’s a day on the planet when there’s not a young woman who discovers herself through the words of my sister.”

. . . . . . . . . .

On this site

The Enduring Power of For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide /When the Rainbow is Enuf by Ntozake Shange

Major Works

For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/ When the Rainbow is Enuf (1975)A Photograph: Lovers-in-Motion (1977)Where the Mississippi Meets the Amazon (1977)A Photograph: A Study of Cruelty (1977)Boogie Woogie Landscapes (1979)Spell #7 (1979)Mother Courage and Her Children (1980)Sassafras, Cypress, & Indigo (1982)Three for a Full Moon (1982)Bocas (1982)From Okra to Greens/A Different Kinda Love Story (1983)Betsey Brown (1985)Three views of Mt. Fuji (1987)Daddy Says (1989)Liliane (1994)Whitewash (1994)Some Sing, Some Cry (2010; with Ifa Bayeza)Wild Beauty: New and Selected PoemsIf I Can Cook / You Know God Can (2019; posthumous)More Information and sources

Wikipedia The Poetry Foundation Official Ntozake Shange site Browse Biography Obituary in The New York TimesSkyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Ntozake Shange appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 26, 2019

Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Her Daughter Mary Shelley

It seems fortuitous that 260th birthdate of Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 – 1797) in 2019 dovetailed closely with the 200th anniversary in 2018 of Mary Shelley’s 1818 masterpiece Frankenstein. There’s a profound connection between these two famous authors; they were, of course, mother and daughter. A book well worth reading about these women is the remarkable biography, Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley by Charlotte Gordon.

Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley were physically part of each other’s lives only for a few days as Mary Wollstonecraft died ten days after giving birth to Mary due to an infection. Yet the space they filled in each other’s lives was much wider.

All her adult life, Mary Wollstonecraft worked relentlessly to improve the lives of girls and women through her writing (in particular Thoughts On The Education Of Daughters: With Reflections On Female Conduct, In The More Important Duties Of Life and A Vindication Of The Rights Of Woman: With Strictures On Political And Moral Subjects). For a period of time, she ran a school for girls. Furthermore, she tried to secure a future for her sisters.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Mary Wollstonecraft

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Her daughter came into her life when she had opened a new, happier chapter. She had an established position as a writer and was financially independent. She had just entered into a marriage with a man who fully appreciated her as a person and an equal partner. The newly born daughter was part of her hopes for happiness.

Much of Mary Shelley’s life was shaped by her mother’s legacy. She knew of all her mother’s works and wanted to be equally audacious and authentic in her writing as well as personal life. It is to her mother she dedicated her novel Frankenstein: “The memory of my mother has always been the pride and delight of my life.” Charlotte Gordon’s book weaves both of their life stories into one. She finds a way to reconstruct the threads of their relationship, while not losing the uniqueness of their stories.

Both lived in times of great change of their society – Mary Wollstonecraft in the times of American and French Revolution, Mary Shelley of the emerging Romanticism. They were engaged in the most vivid debates of their times and fought for the right of women to shape their destiny.

As a historian and literature researcher, Charlotte Gordon provides a comprehensive background of the period. However, she goes beyond facts and uses her craft as a writer to forge an intimate bond between the reader and the two protagonists. She dives into their writing and letters to understand their motivations. This is especially important to understand their complex relationships with the men in their lives.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Romantic Outlaws by Charlotte Gordon on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . . . .

First of all, there was the father of Mary Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft’s husband — William Godwin. He and Mary Wollstonecraft found each other later in life and had to learn to appreciate one another’s qualities. Mary Wollstonecraft had experienced a major disappointment in love and was learning to trust a man again.

As for his daughter, he influenced young Mary’s education and encouraged her to write. However, Mary Shelley experienced a significant estrangement with her father, as he did not accept her choice to elope with a married man — the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, who was ironically a follower of his. For a long time, he also hinted that her writing wasn’t what he expected and that she could do better.

Mary Shelley’s husband, Percy Shelley, was a profound admirer of Mary Wollstonecraft’s work. Their first “date” took place at the most sacred place for Mary Shelley – her mother’s grave. He valued Mary as a person and writer. At the same time, his constant desire to lead a radical and adventuresome life would jeopardize the stability and safety of the young family.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Mary Shelley

. . . . . . . . . . . .

The family relationships were marked by grief. Mary Wollstonecraft was at the peak of her womanhood when she died. She was confident about being a mother and well prepared for birth. Her death was sudden and unexpected.

Mary Shelley lived with a constant burden of guilt that she had been the reason for her mother’s death. Subsequently, she didn’t grow up in a happy household, with conflicting feelings toward her stepmother and her father’s strong expectations. In a sense, she lost both of her parents. Her father pushed her away and after she chose to be with Shelley, and didn’t respond to her attempts at reconciliation. This was perhaps reflected in Frankenstein, whose emotional theme is a cry for love and pain of rejection.

Nevertheless, along with grief, there’s a stream of love and connection which flows between the two women. Mary Shelley drew inspiration and hope from her mother throughout all her life. She was confident that she knew who her mother was and that they shared common values. Both of them believed in education and learning.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

How Mary Shelley Came to Write Frankenstein

How Mary Shelley Came to Write Frankenstein

. . . . . . . . . . . .

They chose to be courageous and didn’t run away from the consequences of their choices. They wanted to make the world better. Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley set very high standards for their writings, but were also forced to struggle and comprise in the publishing world.

Despite the mixed feelings towards marriage as an institution which carried the stigma of oppressing women, they believed in fidelity in love. Finally, they awaited the birth of their children with joy.

The achievement of contemporary herstory is bringing to light not just women that have been forgotten, but also the relationships between them. Thanks to Charlotte Gordon’s work, we can learn from the relationship between the amazing mother and daughter.

Contributed by Magdalena Macinska.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Her Daughter Mary Shelley appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 22, 2019

“Brass Ankles Speaks”: Alice-Dunbar Nelson on Growing up Multiracial

Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1875 – 1935) used her poetry, essays, and short stories to confront complex issues of being a multiracial woman in America. Active in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, she grappled with the feeling of non-belonging to one racial community nor the other. “Brass Ankles Speaks” is an essay she wrote, undated, presumably in the early 1900s. It was never published during her lifetime.

Despite her personal struggles, Alice Dunbar-Nelson devoted her life to fighting for social and racial justice and women’s equality not only through her writing, but as an activist and speaker.

In an analysis of this controversial piece writing, Bridget Maguire wrote:

Alice Dunbar-Nelson clearly grapples with the complexity of her multiracial appearance in her essay “Brass Ankles Speaks,” a frank and likely controversial essay she never published during her lifetime. Not only does she wrestle with her ability to pass as white, but she also confirms her inability to control how some black people viewed her. Due to the light shade of her skin, other blacks sometimes perceived her as an elitist. Dunbar-Nelson exposes the complicated colorist system within the black community.

In the beginning of the essay, Dunbar-Nelson proclaims, “I am of the latter class, what E. C. Adams in ‘Nigger to Nigger’ immortalizes in the poem, ‘Brass Ankles.’ White enough to pass for white, but with a darker family background, a real love for the mother race, and no desire to be numbered among the white race”. Her longing to be perceived as a member of the African American race is hindered by her rejection by some blacks who see her ability to pass and lighter skin color as an indication of conscious, pretentious distinction …

As a child, she faced this impossible acceptance in school where darker classmates bullied her for her lighter, “whiter” appearance … When Dunbar-Nelson began her teaching career in New Orleans, she experienced these same colorist problems and found, to her dissatisfaction, their replication in the Northern cities that she later moved to.

. . . . . . . . .

“Brass Ankles Speaks” by Alice Dunbar-NelsonThe “Race” question is paramount. A cloud of books, articles and pronunciamentos on the subject of the white man or girl who “passes” over to the other side of the racial fence, and either entirely forsakes his or her own race, to live in terror or misery all their days, or else come crawling back to do uplift work among their own people, hovers on the literary horizon.

On the other hand, there is an increasing interest and sentimentality concerning the poor, pitiful black girl, whose life is a torment among her own people, because of their “blue vein” proclivities. It seems but fair and just now for some of the neglected light-skinned colored people, who have not “passed” to rise and speak a word in self-defense.

I am of the latter class, what E. C. Adams in “Nigger to Nigger” immortalizes in the poem, “Brass Ankles.” White enough to pass for white, but with a darker family background, a real love for the mother race, and no desire to be numbered among the white race.

My earliest recollections are miserable ones. I was born in a far Southern city , where complexion did, in a manner of speaking, determine one’s social status. However, the family being poor, I was sent to the public school. It was a heterogeneous mass of children which greeted my frightened eyes on that fateful morning in September, when I timidly took my place in the first grade.

There were not enough seats for all the squirming mass of little ones, so the harassed young, teacher—I have reason to believe now that this was her first school—put me on the platform at her feet. I was so little and scared and homesick that it made no impression on me at the time. But at the luncheon hour I was assailed with shouts of derision—”Yah! Teacher’s pet! Yah! Just cause she’s yaller!” Thus at once was I initiated into the class of the disgraced, which has haunted and tormented my whole life— “Light nigger, with straight hair!”

. . . . . . . .

See also: A Selection of Poems by Alice Dunbar-Nelson

. . . . . . . . .

This was the beginning of what was for nearly six years a life of terror, horror and torment. For in this monster public school, which daily disgorged about 2500 children, there were all shades and tints and degrees of complexions from velvet black to blonde white. And the line of demarcation was rigidly drawn—not by the fairer children, but by the darker ones.

I had no color sense. In my family we never spoke of it. Indian browns and cafe au laits, were mingled with pale bronze and blonde yellows all in one group of cousins and uncles and aunts and brothers and sisters. For so peculiarly does the Mendelian law work in mixed bloods, that four children of two parents may show four different degrees of mixture, brown, yellow, tan, blonde.

In the school, therefore, I felt at first the same freedom concerning color. So I essayed friendship with Esther. Esther was velvet dark, with great liquid eyes. She could sing, knew lots of forbidden lore, and brought lovely cakes for luncheon.

Therefore I loved Esther, and would have been an intimate friend of hers. But she repulsed me with ribald laughter—”Half white nigger! Go on wid ya kind!”, and drew up a solid phalanx of little dark girls, who thumbed noses at me and chased me away from their ring game on the school playground.

Bitter recollections of hair ribbons jerked off and trampled in the mud. Painful memories of curls yanked back into the ink bottle of the desk behind me, and dripping ink down my carefully washed print frocks. That alone was a tragedy, for clothes came hard, and a dress ruined by ink-dripping curls meant privation for the mother at home.

How I hated those curls! Charlie, the neighbor-boy and I were of an age, a complexion and the same taffy-colored curls. So bitter were his experiences that his mother had his curls cut off. But I was a girl and must wear curls. I wept in envy of Charles, the shorn one. However, long before it was the natural time for curls to be discarded, my mother, for sheer pity, braided my hair in a long heavy plait down my back. Alas! It, too, was ink-soaked, pulled, yanked and twisted.

I was a timid, scared, rabbit sort of a child, but out of desperation I learned to fight. My sister, a few years older, was in an upper grade, through those six, fearsome years. She had learned early to defend herself with well-aimed rocks, ink bottles and a scientific use of sharp finger-nails. She taught me some valuable lessons, and came to my rescue when my nerve had given out. She had something of the spirit of an organizer, too, and had a gang of “yellow niggers” that could do valiant service in the organized warfare between the dark ones and the light ones.

I used to watch the principal of the school, and her fellow teachers with considerable interest as I grew older and the situation unfolded itself to me. As far as I can remember now, they were all mulattoes or very light brown. If their sympathies were with the little fair children, who were so bitterly persecuted, they never gave any evidence.

The principal punished the belligerents with an impartiality that was heart-breaking. Years afterward, I learned that she had told my mother and the mothers of other girls of our class and complexion that she understood and appreciated our sorrows and troubles, but if she gave any evidence of sympathy, or in any way placed the punishment where she knew it rightfully belonged, the parents of the darker children would march in a body to the Board of Education, and protest against her as being unfit for the job.

Time went on, and a long spell of illness took me out of the school. That too, was due to color prejudice. There wasn’t a small-pox scare, and the Board of Health ordered one of those wholesale vaccinations that are sometimes worse than the disease.

My mother sent a note to the principal asking her not to have me vaccinate. on the day selected, but that she would take me to the family physician that night, and send the certificate to school in the morning. The principal read the note, shook her head, looked at me sorrowfully, “You should have stayed at home today, ” was her terse comment.

So I was dragged, screaming and protesting to have my arm scratched with a scalpel instead of a vaccine point. Terror and rage helped the infection which followed, and for a long while my life was despaired of. It seemed certain that I would lose my arm. Somehow, I did not, and when I was well enough, about eighteen months later, to think of education, my mother sent me to a private school.

The bitterness that had been ingrained in me through those six fateful years, from six to twelve years of age, stayed. The new school was one of those American Missionary Schools founded shortly after the war, as an experiment in Negro education. Later, these same schools became the aristocratic educational institutions of the race.

Though the fee was only a nominal one, it was successful in keeping out many a proletariat. Thus gradually, all over the South these very schools which were founded in a missionary spirit by the descendants of abolitionists for the hordes of knowledge-seeking freedmen, became in the second and third generations, the exclusive stamping grounds of the descendants of those who were never slaves, or of the aristocrats among freedmen.

And because here I found boys and girls like myself, fair, light brown, with educated parents, descendants of office holders under the reconstruction regime or of free antebellum Negroes, with traditions—therefore was I happy until the end of my high and normal school career.

Except for Eddie. I loved Eddie. He represented to me the unattainable, for he was in the college department, and he won prizes in oratory and debate and one day smiled at me understandingly when I was only a high school freshman. I walked on air for days. But Eddie was of a deep darkness, and refused to allow me to love him. With stern dignity he checked my fluttering advances. He would not demean himself by walking with a mere golden butterfly; far rather would he walk alone, he told me. It broke my heart for nearly a month.

Out in life, I found myself confronted, as did most of my friends and associates, with the same problems which had confronted the principal of that public school. I became a public school teacher. There were little dark children in my school.

I had to watch them tormenting the little fair children, and not lift my hand to protect them, at the risk of a severe reprimand from my principal or supervisor, induced by complaints from parents. I had to endure in hot, shamed silence the innuendos constantly printed in the weekly colored newspaper—a sort of local Smart Set—against the fair teachers, every time one was seen with a new coat or hat. How could they afford to dress so well? was the constant query.

Light colored girls, it was well known, were the legitimate prey of white men. Were not the members of the Board of Education helping out the meagre salaries of the better looking teachers? What price shame? Protest? The editor was a black man and owed allegiance to no proprietary, His daughter had failed to pass the teachers’ examination; she had failed in the normal school; she had failed in the high school. She was really stupid. But her father would not believe it. There were some darker girls who had made brilliant records in in school; were brilliant teachers. He shut his eyes to their prowess and vented his spleen upon the light ones who had succeeded.

After teaching a year or two, I had saved enough to embark upon my cherished ambition—to go to college, and so I came North. Here I found a condition just as bitter, but more subtle. You come up against a dead wall of hate and prejudice and misunderstanding, and you cannot tell what causes it.

During the summer session I had lived with a colored family in the town. The room was uncomfortable, the food not good, and the prices as high as in the school. Therefore, when I decided to return for the winter, I applied for and secured a place in one of the college cottages. This branded me at once among the colored students.

I was said to be “passing,” though nothing was further from my mind—especially as there were no race restrictions in the dormitories. I tried to make friends among the colored girl students—all of whom that year were brown. Success came only after the hardest kind of hard work, and it was only a truce. I had to batter down a wall, which had doubtless been erected by my erstwhile dark-skinned landlady.

I had registered from my own religious creed. The rector of the white church in town called at once, made me welcome, and asked me to connect myself with his church. I waited three weeks for the colored minister to make a like overture. I would have preferred the colored church, for I had always taken an active part in our little church at home among my own people.

But no gesture was made, so I went to the white church. Then an entertainment was given at the colored church. I saw a flier for the first time on the day of the affair, with my name down for a recitation. Naturally, I did not go on such slight notice, and forever afterwards was branded among the colored townspeople as a “half white strainer, with no love for the Race.”

And yet, in spite of all the tragedy of my childhood and young womanhood, I had not been able to develop that color sense. When I say this to my darker friends, they simply laugh at me. They may like me personally; they may even become my very good friends; but there is always a barrier, a veil—nay, rather a vitrified glass wall, which I can neither break down, batter down, nor pierce. I have to see dear friends turn from a talk with me, to exchange a glance of comprehension and understanding one with another which I, nor anyone of my complexion, can ever hope to share.

In the course of my peregrinations, after college days, I came to teach in a small city on the Middle Atlantic Seaboard. A little city where hate is a refined art, where bitterness is rife, and where prejudice is a thing so vital and potent that it makes all other emotions seem pale and insignificant.

I shall never forget the day that I was introduced by the principal to the faculty of the high school where I was to teach. There were two other faces like mine in the group of thirty. The two who looked like me, exchanged glances of pity—the others measured me with cold contempt and grim derision. A sweat broke out on me. I knew what I was up against and an icy hand clutched my heart. I felt I could never break this down; this unreasoning prejudice against my mere personal appearance.

With the children it was the same. The day I walked into my classroom, I head a whisper run through the aisles, “Half white nigger!” For a moment I was transplanted to that first day at school twenty odd years ago.

The agony of that first semester! The nerve-racking terror of never knowing where there would be an outbreak of unreasoning prejudice among those dark children, venting itself in a spiteful remark, and undoing in a moment what I had spent weeks to create.

The heart-breaking rebuffs when I tried to be cordial with my fellow-teachers; the curt refusals to walk home with me, or to go to church or places of amusement. The scathing denunciations of irate parents when their children did not get the undeserved marks they wanted. I was accused of everything except infanticide. Mine had been the experiences of the other two teachers, I was told.

The principal protected as far as he could, but what can a busy man do against a whole community? If I had a dollar for every bitter, scalding, hopeless tear that I shed that first school year, I should be independently wealthy. It was only sheer grit and determination not to be beaten that kept me from throwing up the job and going back home.

Small wonder, then, that the few lighter persons in the community drew together; we were literally thrown upon each other, whether we liked or not. But when we began going about together and spending our time in each other’s society, a howl went up. We were organizing a “blue vein” society. We were mistresses of white men. We were Lesbians. We hated black folk and plotted against them. As a matter of fact, we had no other recourse but to cling together.

Much water has passed under the bridge since those days, and I have lived in many other communities. Save for size, virulence, and local conditions, the situation duplicates itself. Once I planned a pageant in one community. “You’ll never put it over,” my friends adjured me; “You haven’t enough pull with the darker people.”

But I planned my committees always to be headed up by black or brown men or women, who in turn selected their aides, thus relieving me of all responsibility. It went over big, in spite of misfits on committees. But had I actually placed thereon men and women of real ability, who could have handled the situation more efficiently, the whole thing would have fallen to the ground if they were light in color.

I have served on boards and committees of schools, institutions, projects. I have seen the chairmen, or those with appointing power, look at me apologetically, and name someone whom they knew and I knew was unfit for a place, where I could have best helped and worked. But they did not dare be accused of partiality on account of color.

I have had my offers of help in charity affairs refused, or if accepted grudgingly, credit withheld or services forgotten. I have been turned down by my own race far more often than many a brown-skinned person has been similarly treated by the white race. I have been snubbed and ostracized with subtle cruelties that I am safe to assert have hardly been duplicated by the experiences of dark people in their dealings with Caucasians. I say more cruel, for I have been foolishly optimistic enough to expect sympathy, understanding and help from my own people—and that I receive rarely outside of individuals of my own or allied complexion.

As if there is not enough stupid cruelty among my own, I have had to suffer at the hands of white people because of my likeness to them. On two occasions when I was seeking a position, I was rejected because I was “too white,” and not typically racial enough for the particular job.

Once when I was employed in a traveling position during the war, I came into headquarters from a particularly exhausting trip through the South. There I had twice been put off Jim Crow cars, because the conductor insisted that I was a white woman, and three times refused food in the dining-car, because the colored waiters, “tipped off” the white stewards. When I reached headquarters I found three of my best so-called brown skinned friends protesting against sending me out to work among my own people because I looked too much like white.

Once I “passed” and got a job in a department store in a large city. But one of the colored employees “spotted” me, for we always know each other, and reported that I was colored, and I was fired in the middle of the day. The joke was that I had applied for a job in the stock room where all the employees are colored, and the head of the placing bureau told me that was no place for me—”Only colored girls work there,” so he placed me in the book department, and then fired me because I had “deceived” him.

I have had my friends meet me downtown in city streets and turn their heads away, so positive that I do not want to speak to them. Sometimes I have to go out of my way and pluck at their sleeves to force them to speak. If I do not, then it is reported around that I “pass” when I am downtown—and sad is my case among my own kind then.

There are a thousand subtleties of refined cruelty which every fair colored person must suffer at the hands of his or her own people. And every fair colored woman or man, girl or boy who reads this knows that I have not exaggerated. If it be true that thousands of us pass over into the white group each year, it is due not only to the wish for economic ease and convenience, but often to the bitterness of one’s own kind. It is not to be wondered at that lighter skinned Negroes cling together in their respective communities. It is not so much that they dislike the darker brethren, but the darker brethren DO NOT LIKE THEM.

So I raise my tiny voice in all this hub-bub of “Race” clamor; all this wishy-washy sentimentalism about the persecuted black ones of the race, and their inability to get on with their own kind. As in Haiti, as in Africa, the bitterness and prejudice have always come from the blacks to the yellows. They have been the greatest sufferers, because they have had, perforce, to suffer in silence. To complain would be only to bring upon themselves another storm of abuse and fury.

The “yaller niggers,” the “Brass Ankles” must bear the hatred of their own and the prejudice of the white race. If they do not choose to go over to the other side—and tens of thousands feel, like myself, that there is no gain socially in so doing, though there may be some economic convenience—then they are forced to draw together in a common cause against their blood brothers who visit upon them hatred and persecution.

Originally published on Modern American Poetry.

The post “Brass Ankles Speaks”: Alice-Dunbar Nelson on Growing up Multiracial appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 20, 2019

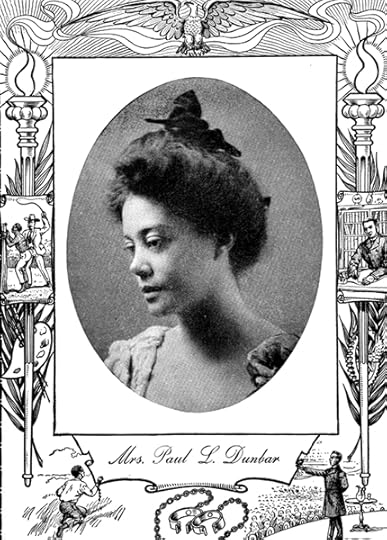

Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Alice Dunbar-Nelson (July 19, 1875 – September 18, 1935) was an American poet, essayist, short story writer, journalist, activist, and teacher. Sometimes known as Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson, she advocated for the rights of women and African-Americans and was considered one of the premier poets of the Harlem Renaissance era.

Born Alice Ruth Moore in New Orleans, she was of Creole heritage, blending African-American, Creole, European, and Native American roots. Her mixed ancestry would give her a broad perspective on race as she matured, while she personally struggled with the issue of belonging.

Her father, Joseph Moore, a freed slave, was a merchant marine, and her mother, Patrica Wright, was a seamstress. Her family was considered middle class, so she was able to benefit from growing up in a diverse city, fairly free from the constraints of Jim Crow laws.

Alice graduated from Straight University (now Dillard University) in 1892. This was notable for its time, as less than 1% of all Americans were college graduates, let alone women and people of color. Her first job was as a teacher in New Orleans’ public school system. Subsequently, she worked in a variety of occupations, most notably in journalism as an editor and columnist.

Early publications

Violets and Other Tales, her first book, was a collection of poetry, essays, and short stories. Just twenty at the time of its publication in 1895, Alice’s writings were already flavored with feminism and social justice.

The noted poet Paul Laurence Dunbar began writing to Alice after seeing a photo of her with a poem she had published in an issue of Monthly Review in 1897. They conducted their relationship mainly via correspondence and married secretly in 1898 in New York City. The couple then moved to Washington, D.C.

Critics have noted the uneven quality of the writings, though some of the pieces showed her promise as a writer. She wasn’t easy to pigeonhole, which made publishing her work a challenge. Sheila Smith McCoy wrote:

Dunbar-Nelson continued to write and, in 1899, published The Goodness of St. Rocque and Other Stories, which included a revision of “Titee” (one with a happier ending), “Little Miss Sophie,” and “A Carnival Jangle.” Aside from the ending of “Titee,” the revisions of these stories heralded the problems that she faced with later manuscripts.

Publishers, eager for dialect stories such as those that made Paul Laurence Dunbar famous, opted for versions of these stories in which the characters spoke with pronounced creole dialects. Dunbar-Nelson’s published fiction dealt exclusively with creole and anglicized characters; difference was characterized not in terms of race, but ethnicity.

Many of her manuscripts and typescripts, both short stories and dramas, were rejected when Dunbar-Nelson explored the themes of racism, the color line, and oppression. This, coupled with the fact that Violets and St. Rocque, published so early in her career, were, until recently, the only published collections of her work, have made it difficult for both readers and critics to access Dunbar-Nelson’s work.

. . . . . . . . .

A selection of Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s poetry

. . . . . . . . .

What began as a romantic liaison with Paul Dunbar soon turned into a disastrous marriage. Dunbar was in poor health, an alcoholic, and suffered from a form of tuberculosis. He physically abused Alice and nearly beat her to death in 1902, after which she left him. Alice was bisexual, and it has been posited by Lillian Fadiman, author of Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America, among others, that Dunbar was angered by her affairs.

After their parting, Alice moved to Wilmington, Delaware. She never saw Paul again, and despite the acrimonious ending, never formally divorced him and continued to publish under the name Alice Dunbar. There, she resumed her career in education, teaching in a high school as well as at the State College for Colored Students (Delaware State College) and Howard University. Paul Dunbar died in 1906.

Alice married Henry Arthur Callis, a physician, in 1910. This marriage, too, was short-lived. In 1916, she married Robert J. Nelson, a civil rights activist, who may have been the catalyst, at least in part, for her increasing involvement with social justice issues, primarily racial equality and women’s rights. This marriage endured, and Alice continued to have intimate relationships with women as well.

Alice, like her husband, became politically active, and in the early 1920s, campaigned for the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill (which was ultimately unsuccessful, because of a racist congress). She also helped establish several schools for African-American girls.

. . . . . . . . .

Books by and about Alice Dunbar-Nelson on Amazon

. . . . . . . . .

While teaching in Wilmington, Alice continued to publish poetry and essays and served as an editor for African-American periodicals and anthologies. Her poems were widely published in The Crisis (NAACP), Ebony, Topaz, and Opportunity (Urban League) in the late ‘teens and through the 1920s.

This was a remarkably productive period. Alice was right in the thick of the creative flowering of the Harlem Renaissance era, though she didn’t live in New York City, where much of the action was taking place.

Alice was also committed to journalism in the 1920s, contributing highly regarded columns, articles, and essays to several prominent Black newspapers as well as magazines and academic journals. She was also, during this time, a sought-after lecturer and speaker. While she achieved an unusual degree of success in journalism, it was no easy path for a woman of color, and she wrote honestly the obstacles she faced.

In her searingly honest essays in which she also recounted the challenges of growing up mixed-race in Louisiana. She explored these themes along with the varied and complex issues faced by women of color in both her essays and in her body of short stories. In “Brass Ankles Speaks,” for example, she wrote about multiracial people bearing “the hatred of their own and the prejudice of the white race.”

As her reputation grew, she continued to explore sexism, racism, work, sexuality, and family in the various genres in which she wrote.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Gloria T. Hull, editor of The Works of Alice Dunbar-Nelson (Oxford University Press, 1988), wrote of her subject:

“One senses in practically everything that Alice Dunbar-Nelson wrote a driving desire to pull together the multiple strands of her complex personality and poetics …

What she was able to achieve in prose outweighs her poetic accomplishments although, ironically, being taken as a poet has helped immensely to keep her reputation alive. Dunbar-Nelson was not driven to write poems and did not focus on the genre …

By and large, Dunbar-Nelson’s poetry is what it appears to be—competent treatments of conventional lyric themes in traditional forms and styles. Her signature poem, “Violets,” is the apogee of this type. A few others stand out for various reasons. “I Sit and Sew,” wherein a woman chafes at her domestic role during wartime, seems feminist in spirit.

“You! Inez!” appears to be a rare eruption in verse of Dunbar-Nelson’s lesbian feelings. “Communion” and “Music” were probably (like “Violets”) selections in a no longer extant Dream Book commemorating her illicit affair with Emmett J. Scott, Jr. “To Madame Curie” and “Cano—I Sing” are strikingly well-executed … “The Proletariat Speaks” reminds one of her consciousness about difference and class contrasts.

Dunbar-Nelson, in her way, helped to create a black short-story tradition for a reading public conditioned to expect only plantation and minstrel stereotypes. Her strategy for escaping these odious expectations was to eschew black characters and culture and to write, instead, charming Creole sketches that solidified her in the then-popular, ‘female-suitable’ local color mode.”

Later in life, Alice moved to Philadelphia with her husband when he went to work for the Pennsylvania Athletic Commission. Her health began to decline, and she died in a Philadelphia hospital on September 18, 1935, at the age of sixty.

More about Alice Dunbar-NelsonOn this site

A Selection of Poems by Alice Dunbar-NelsonMajor works

Violets and Other Tales (1895)The Goodness of St. Rocque and Other Stories (1899)Masterpieces of Negro Eloquence (1914; in the capacity of editor)Mine Eyes Have Seen, (1918; one-act play)“From a Woman’s Point of View” (later, ”Une Femme Dit”; column for the Pittsburgh Courier , 1926)“I Sit and I Sew,” “Snow in October,” and “Sonnet,” in Caroling Dusk:An Anthology of Verse by Negro Poets (1927)“As in a Looking Glass” (1926–1930; column for Washington Eagle newspaper)”So It Seems to Alice Dunbar-Nelson” (1930; column for the Pittsburgh Courier)

Biographies and critical anthologies

Give Us Each Day: The Diary of Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Gloria T. Hull, editor (1984)The Works of Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Gloria T. Hull, editor (1988)More information and sources

Wikipedia Poetry Foundation Modern American Poetry Alice Ruth Moore Dunbar-Nelson on BlackPast Biography of Alice Dunbar-Nelson on ThoughtCo.. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Alice Dunbar-Nelson appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 14, 2019

How to Write a Romance by the editors of Avon Books

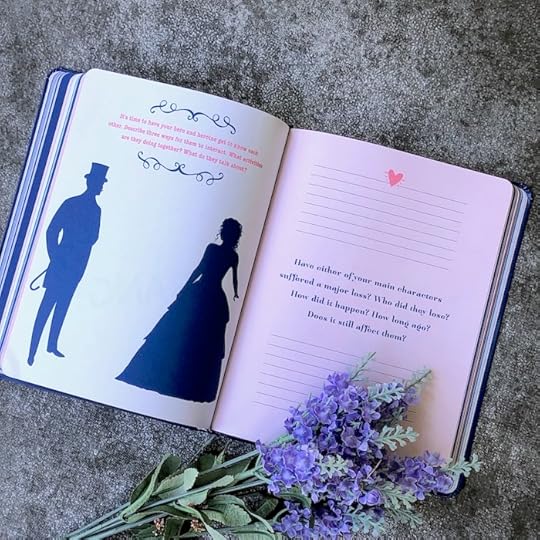

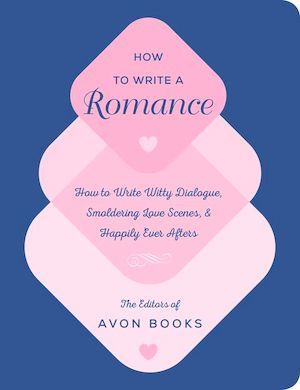

Are you in the mood for romance? Most of us are, at least some of the time. Are you in the mood to write a romance novel? Now, that’s a more specific desire, but if you’ve ever fancied giving it a try, the editors of Avon Books, one of the leading publishers of romance books, have produced How to Write a Romance: Or How to Write Witty Dialogue, Smoldering Love Scenes, and Happily Ever Afters (Morrow Gift, July 2019).

It’s a cleverly designed guided journal that just might get you going, and a perfect gift for the aspiring romance writer in your life.

Many of the most beloved novels of all time are incredibly romantic, and perhaps the literary predecessors of contemporary romances. Classic plot lines often feature a plucky heroine who wants to be her own person, while at the same time, yearns for the love of a brooding, mysterious man.

Think of Elizabeth Bennett and Mr. Darcy of Pride and Prejudice; Catherine and Heathcliff of Wuthering Heights; the eponymous Jane Eyre and Edward Rochester; the nameless narrator of Rebecca and her inscrutable husband, Maxim de Winter.

. . . . . . . . . .

What do you consider the most romantic classic novel?

Many literature nerds would choose Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

. . . . . . . . . .

Today’s romance novels go far and wide in terms of character types and are no longer confined to bodice-ripping or predictable will-they-or-won’t-they plots. If you’re ready to take the next step with your own writing, How to Write a Romance might be just the inspiration you’ve been looking for. Here’s what the editors of Avon Books have to say:

Romance novels are in the mainstream. No longer are they relegated to the back of the bookstore; they are front and center with colorful covers, boast a diverse readership, and are covered by national media.

As romantic comedies are coming back in a big way, they are influenced and often based on bestselling romance novels. Beyond that, romance novel reading and writing is its own subculture; just check your twitter timeline for when #Romanclandia trends; the readers are voracious, tireless and passionate.

There are few who know the romance landscape better than the incomparable editors at Avon Books. Their list spans several decades of bestselling romance, from the 1970s cult classic The Flame and the Flower by Kathleen Woodiwiss to the incomparable Night Song by Beverly Jenkins in the 1990s, and through the early 2000s with Julia Quinn’s Bridgerton series, soon to be a Netflix original series. Today, Avon publishes these authors and more, setting a standard for the industry.

For romance writers and readers alike, How to Write a Romance is a sleek, inventive journal that will inspire you to create love stories that stir the heart, tease the imagination, and touch the soul. Inside this handy diary, you’ll find an introduction and tip sheet compiled by the editors fo Avon Books.

Sharing their wisdom and expertise, the Avon Books editors guide you journals through the basic construction of a romance novel and highlight the most common pitfalls to avoid. The pages that follow include 180 prompts touching on every aspect of romance writing: dialogue, character development, scene descriptions, situational entries, and more. These include:

Describe your heroine without her having to look in the mirrorMake a list of 5 to 10 of your hero’s characteristics — be sure to include both good and bad qualities to help clarify how he will react in different situations.Write a scene between two females characters discussing something unrelated to the heroWrite a meet cute in a library.

In addition, renowned bestselling Avon authors such as Eloisa James, Beverly Jenkins, Lisa Klaypas, Julia Quinn, Sarah McClean, Jennifer Ryand, Lori Wilde, and more, share their own insights and offer work of encouragement, sprinkled throughout the journal in hand-lettered text.

A beautiful keepsake and practical tool that embodies the essence of romance fiction, How to Write a Romance will enflame your passionate and creative spirit!

. . . . . . . . . .

How to Write a Romance is available on Amazon

and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post How to Write a Romance by the editors of Avon Books appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 11, 2019

Quotes from I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou (1928–2014) is a 1969 autobiography by the beloved writer and poet written in 1969 covering her upbringing and youth. The book is the first in a seven-volume series. It delves into Angelou’s journey, one in which she experiences and overcomes racism and trauma and develops the strength of character and a love of literature.

The book starts with her as a three-year-old being sent to Stamos, Arkansas, to live with their grandmother along with her older brother. By the end of the book, Angelou is sixteen years old and becomes a mother. Throughout the course of the book, Maya overcomes racism and transforms into an unbreakable woman as she is able to effectively respond to the ignorance of prejudice.

Angelou created her autobiography as a way to explore identity, rape, literacy, and racism. She also gives readers a new perspective about the lives of women in a society that is male-dominated, earning her praise as “a symbolic character for every black girl growing up in America.”

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings was nominated for a National Book Award in 1970. In addition, it has remained on The New York Times paperback bestseller list for two years. The book has made its debut in high school and university classrooms, though some institutions and libraries have banned Caged Bird due to its explicit depiction of childhood rape, racism, and sexuality.

Though it has stirred some controversy, the book continues to be commended for having created new literary avenues for the American memoir. Here is a selection of quotes from I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, the raw and inspiring autobiography about the early life of Maya Angelou.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“Life is going to give you just what you put in it. Put your whole heart in everything you do, and pray, then you can wait.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Hoping for the best, prepared for the worst, and unsurprised by anything in between.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Words mean more than what is set down on paper. It takes the human voice to infuse them with shades of deeper meaning.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Anything that works against you can also work for you once you understand the Principle of Reverse.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Instead, pursue the things you love doing, and then do them so well that people can’t take their eyes off you.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The caged bird sings with a fearful trill,

of things unknown, but longed for still,

and his tune is heard on the distant hill,

for the caged bird sings of freedom.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“To be left alone on the tightrope of youthful unknowing is to experience the excruciating beauty of full freedom and the threat of eternal indecision. Few, if any, survive their teens. Most surrender to the vague but murderous pressure of adult conformity. It becomes easier to die and avoid conflict than to maintain a constant battle with the superior forces of maturity.”

. . . . . . . . . .

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

“I believe most plain girls are virtuous because of the scarcity of opportunity to be otherwise.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If you’re for the right thing, you do it without thinking.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Ritie, don’t worry ’cause you ain’t pretty. Plenty pretty women I seen digging ditches or worse. You smart. I swear to God, I rather you have a good mind than a cute behind.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The Black female is assaulted in her tender years by all those common forces of nature at the same time that she is caught in the tripartite crossfire of masculine prejudice, white illogical hate and Black lack of power.

The fact that the adult American Negro female emerges a formidable character is often met with amazement, distaste and even belligerence. It is seldom accepted as an inevitable outcome of the struggle won by survivors and deserves respect if not enthusiastic acceptance.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“To be left alone on the tightrope of youthful unknowing is to experience the excruciating beauty of full freedom and the threat of eternal indecision.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Without willing it, I had gone from being ignorant of being ignorant to being aware of being aware. And the worst part of my awareness was that I didn’t know what I was aware of. I knew I knew very little, but I was certain that the things I had yet to learn wouldn’t be taught to me at George Washington High School. ”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The quality of strength lined with tenderness is an unbeatable combination, as are intelligence and necessity when unblunted by formal education. ”

. . . . . . . . . .

“At fifteen life had taught me undeniably that surrender, in its place, was as honorable as resistance, especially if one had no choice.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She comprehended the perversity of life, that in the struggle lies the joy.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Maya Angelou Quotes to Live By

. . . . . . . . . .

“A story went the rounds about a San Franciscan white matron who refused to sit beside a Negro civilian on the streetcar, even after he made room for her on the seat. Her explanation was that she would not sit beside a draft dodger who was a Negro as well. She added that the least he could do was fight for his country the way her son was fighting on Iwo Jima. The story said that the man pulled his body away from the window to show an armless sleeve. He said quietly and with great dignity, “Then ask your son to look around for my arm, which I left over there.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If growing up is painful for the Southern Black girl, being aware of her displacement is the rust on the razor that threatens the throat. It is an unnecessary insult.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Women been gittin’ pregnant ever since Eve ate that apple.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It was awful to be Negro and have no control over my life. It was brutal to be young and already trained to sit quietly and listen to charges brought against my color with no chance of defense. We should all be dead. I thought I should like to see us all dead, one on top of the other. A pyramid of flesh with the whitefolks on the bottom, as the broad base, then the Indians with their silly tomahawks and teepees and wigwams and treaties, the Negroes with their mops and recipes and cotton sacks and spirituals sticking out of their mouths. The Dutch children should all stumble in their wooden shoes and break their necks. The French should choke to death on the Louisiana Purchase (1803) while silkworms ate all the Chinese with their stupid pigtails. As a species, we were an abomination. All of us.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The world had taken a deep breath and was having doubts about continuing to revolve.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“When things were very bad his soul just crawled behind his heart and curled up and went to sleep”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I had given up some youth for knowledge, but my gain was more valuable than the loss”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The intensity with which young people live demands that they “blank out” as often as possible.”

. . . . . . . . . .

10 Fascinating Facts About Maya Angelou

. . . . . . . . . .

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 8, 2019

Shirley by Charlotte Brontë (1849): A plot summary

Shirley was the second published novel by Charlotte Brontë. Published in 1849 under the pseudonym Currer Bell, the author had already become famous with the success of Jane Eyre (1847). While Charlotte was at work on this book, her remaining siblings died. The first to go was her troubled brother Branwell, followed by sisters Emily and Anne, who would also come to be celebrated for their literary accomplishments.

The lengthy novel has two female protagonists — the eponymous Shirley Keeldar, as well as Caroline Helstone. Set in Charlotte’s native Yorkshire, it takes place against the background of the textile industry’s Luddite uprisings of 1811 and 1812.

Shirley: A Tale, as it was originally titled, is considered an example of the mid-19th century “social novel.” The social novels that emerged from that period were works of fiction dealing with themes like labor injustice, bias against women, and poverty.

Charlotte supposedly told Elizabeth Gaskell (who, not long after the former’s death would become her first biographer) that the character of Shirley was how she imagined Emily might have turned out if she’d had the benefits of wealth and privilege. Like Shirley, Emily was always accompanied by a “rather large, strong, and fierce-looking dog, very ugly, being of a breed between a mastiff and a bulldog.”

Following is a lengthy plot summary of Shirley by Charlotte Brontë from 1910, befitting a very long and detailed novel. In the early 1900s, interest in the Brontë sisters was still going strong on both sides of the Atlantic, evidenced by the frequency with which their life stories and analyses of their novels showed up in newspapers.

. . . . . . . . . .

Shirley by Charlotte Brontë on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original article in the Boston Globe, March 13, 1910:

Shirley was Charlotte Brontë’s second novel. While it was hardly as popular as Jane Eyre, it was a success from the date of its appearance and has long remained a favorite.

In many respects, it is a much more finished and artistic production than Jane Eyre and is free from many of the crudities and absurdities that are in that first book of “Currer Bell’s.” Of course, Jane Eyre will always exceed Shirley in popularity. But, from an artistic and literary point of view, Shirley is much the better story.

In Shirley, Charlotte Brontë drew her characters from real life, used people with whom she was associated, her own family and her dearest friends as models for her fiction people, and did it with as little faltering and as frankly as did Dickens, who did not hesitate to portray the weaknesses of his own father and mother to advance his literary fame and his worldly fortunes.

Shirley, it will be seen when reading the story, was rather inclined to be “strong-minded.” So was Jane Eyre, it will be remembered, so are most of Charlotte Brontë’s stories.

Perilous times

When Robert Gerald Moore came to the West Riding of Yorkshire and leased Hollow’s mill, the people of the neighborhood regarded him, not as a countryman returned to them, but as a semi-foreigner. And foreigners at that time, whether of the whole or semi-variety, were not popular in England.

Neither were cloth manufacturers who persisted in introducing into their mills those new-fangled machines, one of which did the work of half a dozen hands and thereby deprived working people, honest or dishonest, of the chance of making a living.

Times were hard enough, anyway, without machinery coming to make them harder, for it was at about the darkest hour of that great struggle which a determined stolid nation was waging against the power and splendor of a world-compelling genius.

Napoleon and England had engaged in a struggle. The rest of the nations were pawns on the chessboard of a mighty game. In response to Napoleon’s Milan and Berlin decrees, the British government prohibited all commercial intercourse with nations which accepted the Napoleonic decrees.

The harvest of discontent

America, irritated, declared an embargo. The commerce of the world stood still. The European market had long been practically lost to the manufacturers of England and now the American market, upon which they mainly relied, was closed to them. Their warehouses were piled high with unstable goods. Mill owners shut down or ran their establishments with reduced hands.

Hunger was in the cottage of the operative and bankruptcy in the counting-house of the mill owner. Then came the machinery to make matters worse, as the working people thought: as a straw to clutch at, the owners thought. Improved machinery means less demand for labor, said the operative. Improved machinery means a lessened cost for production, said the owner.

Workmen went about destroying the new inventions. It was a time of harvest for the agitator, the worthless being who lives by the sweat of other men’s brows and wafts himself to ease and power upon the breath of popular discontent; who craftily plays upon ignorance and amuses himself with fanning the flames of evil discord. And the agitators took advantage of the opportunity.

Obsessed with an idea

This was the condition of affairs in commercial England which supervened soon after Robert Moore had set to work at Hollow’s mill with a fixed determination to carry out a purpose which he felt sacred–the purpose of making enough money to pay off the debts of his father and reestablish the name of the once great firm of Gerard & Moore above the gloom of the bankruptcy into which it had fallen.

His mother had been a native of Antwerp and his father of one of the oldest families of Yorkshire. The principal office of the house of Gerard & Moore had been in Antwerp and there his father had married his mother – there Robert had been born and where he had spent much of his youth, though some of it had been passed with his grandfather, who ran the Yorkshire end of the business.

Those great continental wars which swept away nations and thrones also swept away mercantile houses and among them that of Gerard & Moore. There are a proud lot, those mercantile families of long descent, as proud as if they had “all the blood of all the Howards” and the credit of their name is dear to them.

When Robert came back to Yorkshire, the one idea of reestablishing the name of the house obsessed him. Neither love nor mercy should stand in his way. Then he found himself confronted by the situation stated.

The mystery surrounding Caroline

Briarfields was the nearest village to Hollow’s mill, and the rector of Briarfields was a sort of relative by marriage of Robert. His brother had married the half-sister of Robert’s father, and living with Rev Heistone, the rector, was Caroline Helstone, the only offspring of this marriage.

Of her mother Caroline knew nothing. The wild and dissipated career of her husband had been such that when the crisis came and the rector had offered to take charge of the girl the mother, seeing in the face the looks of her father, had abandoned her to the charge of her uncle and had disappeared.

The poor woman shuddered as she looked at the replies in the face of her child of that false, fair face of him who had wrecked her life and abandoned her. No one ever mentioned her mother to Caroline. When she inquired of her she was put off with evasive answers. She saw that her mother had committed some crime–as she thought.

What it really was those of whom she asked felt that the mother had not been true to her trust, that in spite of everything, she should have made herself a part of her daughter’s life.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: A Plot Summary of Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

. . . . . . . . . .

An apostle of authority

Mr. Helstone was a dictatorial, domineering man who thought that authority was the beginning and the end of existence. The orders in council were right because they proceeded from authority. The church was right because it had authority.

He had been twice married and had crushed out the lives of his wives with authority. He was not a bad man; he was a good man, according to his light and went about doing good.

But to him, the crazy king, the solute prince regent, the ministry, the established order of things, in short, were not to be tampered with, come weal to woe.

He was a friend of Moore’s and was prompt to aid him, not only with advice but with physical force when the unemployed workmen, led by demagogues, broke the machines which Moore was transporting to his mills in the Hollow.

All the more was he enlisted on the side of the mill-owner because some self-created preacher of a dissenting denomination had incited the “frame breakers” and had lured people from his parish to listen to his “tub oratory,” as the person called it.

The cottage in the hollow

The rector used to like to have Caroline go to the cottage in the Hollow, where she called Robert and his sister Hortense cousins, and where she took lessons in French from the old maid.

Now and then Robert irritated Mr. Hellstone by being “English.” Why the man would sometimes inveigh against the orders in council! But the times were too exciting, there were too many things to be done to preserve authority, for Mr. Helstone to pay much attention to these heretical opinions of Robert just then. As soon as things quieted down he would reason with him.

In the meantime, the thing to be done was to see that Robert got new machinery in place of that which had been destroyed and that the Moores–to whom Mr. Helstone was proud to be related–were reestablished in their rightful place among the people of Yorkshire.

Intolerant Mr. Yorke

Another of Moore’s neighbors was Mr. Yorke. He was a Yorkshire gentleman, par excellence, in every point. About 50 years old, but looking older because of his white hair, he dwelt in his ancestral house upon his ancestral acres, was intolerant to those above him–kings, nobles, priests, dynasties and parliaments. “All rubbish,” he said, and found no pleasure in them.

He was not irreligious, though a member of no sect; but his religion was that of a man who knows not how to venerate. He believed in God and heaven, but his God and his heaven were those of a man in whom awe and imagination and tenderness were lacking.

He had been a youth once and had traveled and lived in southern Europe. On the wall of his old house were many beautiful and well-selected pictures. He liked to talk about freedom and equality, but at heart, he was a very proud man. He sympathized with all below him but could brook no superior and scarcely an equal.

Yorke and the rector

He hated the rector, not only because they looked at things from different points of view, but also because Mr. Yorke had heard and believed them, and was unforgiving.

Yorke had not been so deeply in love that it had prevented him from marrying afterward a very different sort of woman from the one the rector had taken from him, but he never forgave. Strange to say, he liked Moore, and though he abused him for what he called grinding the face of the poor and roundly abused the rector for taking any part in the quarrel between Moore and the unemployed workmen, he did, in fact, help Moore to keep his mill going and to get in his new machinery.

Perhaps it was Moore’s habit of speaking French with him upon occasions — for Yorke was a fine French scholar, perhaps it was the half-foreign looks and half foreign way of thinking about Moore, which brought back to the Yorkshireman memories of his youthful days on the continent that attracted him.

Walking in a dream

The day after that first lot of machinery which Moore had ordered was destroyed in its passage across the heath by the “frame-breakers,” Caroline Heistone visited the cottage at the Hollow and staid to tea.

She had fallen in love with Robert when he first came, and as the days passed and she saw him in trouble and peril her love increased. “And when people love,” mused Caroline, “the next thing is they marry.”

Robert was very tender to her that day after the breaking of the “frames,” and when Caroline went back to the rectory she walked into a happy dream.

Robert, too, as he went to the mill, had a dream for the moment of the beautiful girl with her statue-like face; but he put it away from him sternly. Love and marriage were not for him – unless love and marriage could help in the rehabilitation of the house of Gerard & Moore.

Yet Robert spoke much of Caroline to his sister Hortense that evening–asked how the girl was getting on with her French, asked many little things about her, what she said and what she thought and how her health was. But he dreamed of machinery and of markets and finances that night, and not of Caroline.

As for Caroline, she lay for a while upon her bed, watching through the windows the shadows of the trees slant down the moonlit sward and then fell into slumbers which were haunted by visions of Robert.

As plainly as she could

So things went on for a while, Caroline finding Robert dearer and dearer to her, and Robert sternly putting out of his mind of all thought of love and matrimony.

As plainly as she could, without violating her native maiden modesty, Caroline intimated to Robert her love for him. Once they were talking about the future, and Caroline said:

“O, I shall probably stay and keep house for my uncle until–”

“Until what?” said Robert, as she paused, “until he dies?”

“No, no,” replied Caroline, blushing a little, “until events, in short, offer some other occupation for me.” She looked at Robert steadily, but he could not, or would not, see.

“I love Robert,” Caroline said to herself that night, “and he ought to see it. I believe he loves me, but will not give in to it. That infatuation of his love for business swallows up all else. My love is dashed against a rock. I will torment myself no more by seeing him.”

But she did see him and when he was a little tender, even when he was kind, hope was renewed in her.

The coming of the heiress

Now into this community, into these affairs, and among these people, came Shirley Keedlar. Mr. Yorke was one of her trustees. The young lady had just come of age, and at Yorke’s request, or rather command, had journeyed down into Yorkshire to live in the ancient house of her father.

For though Miss Keeldar had a masculine name [note — at the time this book was written, Shirley was considered a masculine first name], she was a young lady with all the feminine graces, most beautiful to look upon and with a will of her own not to be disputed by anyone with impunity.

There were many wealthier families in the district, but the Keeldar had lived there, at their place at Fieldhead, for a thousand years, and all the gentry roundabout, titled and untitled, regarded them as a superior clay.

Shirley’s parents had much wished for a boy as the inheritor of their ancient line, and when a girl was born to them they did the best they could with the situation by giving to the girl the name they had selected for the boy who did not appear.

Mrs. Pryor’s greeting

Mr. Helstone, as soon as he heard of the arrival of the heiress of Fieldhead, made his niece put on her bonnet and shawl and accompany him to the mansion house.

In a low-ceilinged, oak-paneled parlor they were received by a woman of matronly form, and though she could not have been more than 45, of no youthful aspect nor, apparently, the wish to assume it, she had a face across which was written as legibly as if in words, “I have seen sorrow.”

It was Mrs. Pryor, formerly the governess of Shirley Keeldar and now her companion. Mrs. Pryor seemed strangely embarrassed when the rector and his niece were announced. Diffident Caroline was delighted to find someone more ill at ease than herself, she began to talk freely with the lady feeling strangely drawn to her.

Mrs. Pryor gazed upon her tenderly yet doubtfully and replied in soft, low tones.

A Jacobin’s confession

Then came in Shirley, fresh and radiant from the garden, through a window opening to the floor, and held in her apron a great mass of flowers which she had just picked. With her was a great dog, half mastiff, half bulldog, which she addressed by the name of Tartar.

Tall, erect, slight, the girl still retaining with her left hand her apron full of flowers, gave her right hand to the rector and said:

“I knew you would come to see me, though you do think Mr. Yorke has made a Jacobin out of me. Good morning.”

“But we will have you no Jacobin,” replied the rector, “they will not steal the flower of

my parish. Now that you are amongst us again you shall by my pupil in politics and religion. I’ll teach you sound doctrine on both points. We are a little Jacobin, for what I know, a confession of faith on the spot.”

He took the two hands of the heiress causing her to let fall her whole cargo of flowers and seated her by him on the sofa.

“Say your creed,” he ordered.

“The Apostles’?”

“Yes.” She said it like a child.

“Now for St. Athanasius’, that’s the test.”