Nava Atlas's Blog, page 69

April 22, 2019

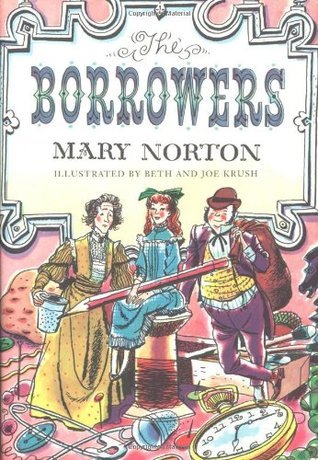

Mary Norton

Mary Norton (December 10, 1903 – August 29, 1992) was a British children’s book author best known for The Borrowers series. Born Kathleen Mary Pearson in London, she grew up in a manor house in the town of Leighton Buzzard, Bedfordshire, England, and attended a convent school.

In 1925, in her early twenties, Mary became an actress with the Old Vic theatre company. In 1926, she married Robert Norton. She and her husband moved to Portugal, close to his relatives, and lived there from 1927 until the outbreak of World War II twelve years later. The couple had four children — two sons and two daughters.

Wartime Life and the Launch of a Writing CareerWhen World War II began, Robert Norton joined the Navy, and Mary took their four children and moved to America. There she published her first novel, The Magic Bed-Knob; Or, How to Become a Witch in Ten Easy Lessons, in 1943. It was published in England two years later and well-received in both markets. At the same time, she worked for the British Purchasing Commission.

This book, and its sequel, Bonfires and Broomsticks, were very popular, and were eventually adapted into the film Bedknobs and Broomsticks, which was released in 1971 and won an Oscar for best special visual effects.

The Borrowers

Post-World War II, Mary Norton and her family moved back to England, where Bonfires and Broomsticks was published and where she wrote her most famous series, The Borrowers.

The series follows the Clocks, a family of the Borrower race. They are only six inches tall and occupy nooks and crannies in a human house based on the manor where Norton grew up. They “borrow” small items from their unknowing human hosts to set up their little homes in corners and under floorboards, where they enjoy mostly quiet lives, sometimes interrupted by adventure. Central characters are Pod, Homily, and their teenage daughter Arrietty.

As a very nearsighted child, Mary had been “an inveterate gazer into banks and hedgerows . . . a rapt investigator of shallow pools,” according to her obituary in The Independent. Young Mary wondered what it would be like to live as a tiny human among the small creatures that she saw there. What might it be like, she wondered, for a very tiny person to see what to them would be an extremely giant and fearsome buzzard circling in the sky? These little creatures and their lives developed and formed themselves in the back of her imagination until she published The Borrowers in 1952.

This book earned her a well deserved place in the pantheon of great children’s authors and was followed by titles The Borrowers Afield, Afloat, Aloft, and Avenged, as well as the short story “Poor Stainless.” These stories about tiny people making their way in a great big world captivated the hearts and minds of parents and children alike in the 1950s and on, and they continue to resonate with readers of all ages today.

The first book won the British Carnegie Medal from the Library Association in 1952, recognizing it as the year’s outstanding children’s book by a British author.

. . . . . . . . . .

Later, Bed-Knob and Broomstick became a combined edition of

The Magic Bed-Knob and Bonfires and Broomsticks

. . . . . . . . . .

After her initial Borrowers success, Norton continued to write. Between Borrowers sequels, she began thinking about where fairy tale creatures go after their tales are over. This led her to pen the quirky, lesser-known Are All the Giants Dead, which is a charming story about a young English boy, a princess, and a lot of retired fairy tale heroes.

Mary divorced Robert Norton and in 1970 was married to Lionel Bonsley until he passed away in 1989. She died three years later from a stroke on August 29, 1992 in Hartland, North Devon, England.

. . . . . . . . . .

Mary Norton page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

It’s difficult to overstate the far-reaching impact of Mary Norton’s books. They are both utterly realistic and utterly fantastic, taking very ordinary heroes and placing them into extraordinary circumstances.

This is a familiar feature of a lot of successful children’s fantasy, as evidenced by authors like C.S. Lewis and J.K. Rowling. In Lewis and Rowling’s cases, it is magic that makes the settings extraordinary. But for Norton’s little heroes, it was the sheer, overwhelming bigness of the world. This is what sets her apart and makes the Clock family so very relatable.

Real children may be more than six inches tall, but everyone knows what it is like to sometimes feel like a very small person in a very big, overwhelming, and sometimes scary world. Norton’s books teach that problems which (like buzzards and cats) may be very small to one person might seem huge and terrifying to another person, but that with a little determination and creativity, even the smallest person can find his or her way out of any predicament.

Mary Norton’s books, already literary classics, will continue to excite and teach children and adults for generations to come.

More about Mary Norton

Major Works

The Magic Bed-Knob (1945)Bonfires and Broomsticks (1947)Are All the Giants Dead? (1975; unconnected with any series)

The Borrowers series:

The Borrowers (1952) The Borrowers Afield (1955)The Borrowers Afloat (1959)The Borrowers Aloft (1961)Poor Stainless: A New Story About the Borrowers (1966)The Borrowers Avenged (Viking Kestrel, 1982)The Complete Borrowers Stories (1983) — omnibus, excluding Poor StainlessMore information

Wikipedia Discussion of Mary Norton’s books on Goodreads Mary Norton’s obituary in The Independent, UKFilm and TV adaptations

The Magic Bed Knob; or, How to Become a Witch in Ten Easy Lessons and Bonfires and Broomsticks were combined and adapted into Bedknobs and Broomsticks, a 1971 Disney film starring Angela Lansbury and David Tomlinson.The Borrowers was a 1997 film with a British and American cast The Borrowers: a 2011 British filmThe Secret World ofArrietty is a 2012 Japanese Anime film inspired by The Borrowers , with an almost perfect score on RottenTomatoes from both viewers and reviewers

There have been numerous theatrical adaptations of The Borrowers and several adaptations of The Borrowers for television, including:

The Borrowers: a 1973 American made-for-TV movie.The Borrowers andThe Return of the Borrowers, BBC series that ran in 1992 and 1993Visit

Mary Norton’s grave is located on the property of St. Nectan’s Church, the parish church of Hartland, Devon. The inscription on her headstone reads:

Do not stand at my grave and weep,

I am not there. I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow.

I am the diamond glints on snow.

I am the sunlight on ripened grain.

I am the gentle autumnal rain.

Do not stand at my grave and cry;

I am not there. I did not die.

(Portion of a poem by American poet Mary Elizabeth Frye, 1905 – 2004)

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Mary Norton appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Bluestockings — A Radical Bookstore Treasure in NYC’s Lower East Side

ctiDo you remember feminist bookstores (for those of you old enough to remember, that is)? Oh, and do you remember independent bookstores in Manhattan? As of this writing, there are only 13 feminist bookstores in North America, down from about 120 in the mid-nineties. And there are only a handful of indie bookstores left in Manhattan, though mercifully, there are a bunch in Brooklyn and Queens (see this great listing).

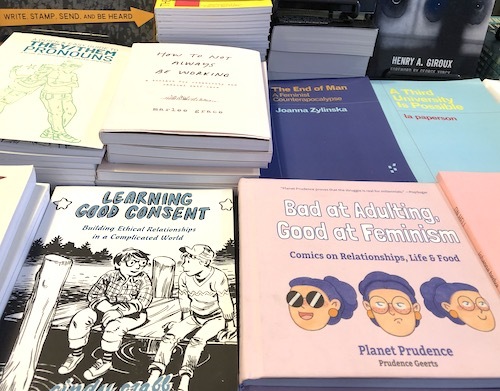

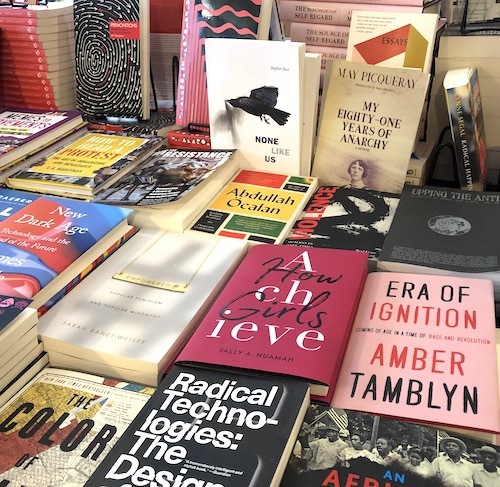

One of Manhattan’s few independent bookstores (and only feminist bookstore) is one of my favorite places, Bluestockings, located in the lively Lower East Side.

It’s more than than a repository for feminist thought; their shelves are filled with a beautifully curated selection of more than 6,000 titles on queer and gender studies, resistance/liberation, capitalism, climate, race, and a selection of rad children’s books. Also on the shelves are zines, journals, and poetry collections.

How about this tag line? “Bluestockings tag line is 98% radical, 100 volunteer-powered, 2% glitter.” It’s a community-oriented venue, and to that end, the store hosts events nearly every evening, including readings, workshops, films, and performances.

Bluestockings was founded in 1999 and is collectively owned and volunteer run. About the collective philosophy: “Bluestockings strives to empower our volunteer workers through non-hierarchy, cooperation, and collective-based decision making, providing an example of the society we are working toward.”

The first time I visited the store, I came to hear a reading from a recently-published book of sci-fi short stories by trans writers — Meanwhile, Elsewhere. And ever since, I’ve stopped to browse and buy, and to rest my weary feet, because there’s no better way to explore the Lower East Side. Bluestockings has a small café with organic, vegan, and fair trade coffee and goodies, and a few tables where you can sit and sip and read.

First of all, where did this name come from? It harks back to The Blue Stockings Society, a political movement and literary discussion group that promoted female authorship and readership in mid-18th century England. Today, the definition of a bluestocking is “an intellectual or literary woman.” Yeah, I’ll wear that mantle proudly!

The store was founded as Bluestockings Women’s Bookstore by Kathryn Welsh, then only twenty-three. With a silent partner and a group of volunteers, the store opened in 1999.

Then a new and used bookstore, its selection focused on feminism and was collectively run. After 9/11, the business declined and was set to close down in 2003 when an angel named Brooke Lehman bought the business. She put together a six-person collective and the store was saved. The updated mission statement reads as follows:

Bluestockings is an independent bookstore, café, and activist resource center, located in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Through words, art, food, activism, education, and community, we strive to create a space that welcomes and empowers all people.

We actively support movements that challenge hierarchy and all systems of oppression, including but not limited to patriarchy, heterosexism, the gender binary, white supremacy and classism, within society as well as our own movements.

We seek to make our space and resources available to such movements for meetings, events, and research. Additionally, we offer educational programming that promotes centered, strategic, and visionary thinking, towards the realization of a society that is infinitely creative, truly democratic, equitable, ecological, and free.

With Bluestockings’ rebirth, the vision was enlarged from feminism to a broader spectrum of progressive and activist books and activities. The store also nearly doubled its space.

Bluestockings is conveniently located at 172 Allen St., New York, NY 10002, just a couple of blocks from the F train at Second Avenue and E. Houston. Open 11 am – 11 pm daily.

While you’re in the neighborhood, other highlights of the Lower East Side include the nearby Tenement Museum, The Museum at Eldridge Street (historic synagogue), and the Lower East Side art galleries.

The post Bluestockings — A Radical Bookstore Treasure in NYC’s Lower East Side appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 20, 2019

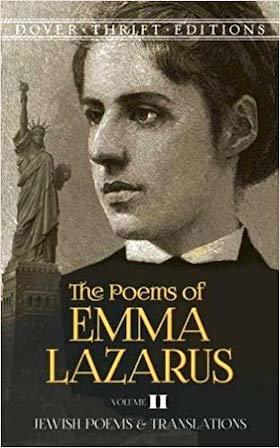

12 Poems by Emma Lazarus, creator of “The New Colossus”

Emma Lazarus (1849 – 1887) was an American poet, translator, and activist. She’s best remembered for “The New Colossus,” an 1883 sonnet that contains the iconic “lines of world-wide welcome” inscribed at the base of the Statue of Liberty:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

It would be a pity if this were her only legacy, as she was an incredibly accomplished woman, made all the more impressive by the fact that she died at the age of thirty-eight. Lazarus was one of the first Jewish American authors to achieve national stature.

She was still in her teens when she started to write and translate poetry; her translations of German poems were published in the 1860s. Her first collection, Poems and Translations, was published in 1867 and caught the attention of Ralph Waldo Emerson.

From that time on, she published regularly and took up causes dear to her heart, both as a writer and activist: the persecution of Russian Jews, the struggles of American Jews, and the argument for a Jewish homeland, well before the concept of Zionism became widely known. Her book, Songs of a Semite, was the first collection of poetry to explore Jewish-American identity and common struggles.

Lazarus spent some time in Europe, and when she returned to New York, she was commissioned to write a poem for the purpose of raising funds for a pedestal for the Statue of Liberty. At first she resisted, but then wrote the sonnet that would seal her legacy, “The New Colossus,” in 1883. Its lines were engraved on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty in 1903, some sixteen years after her untimely death.

Here is a sampling of poems by Emma Lazarus, an American poet who deserves to be read and remembered. Many of her best-known poems were written in the 1880s.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The New ColossusNot like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

The New Year

Rosh-Hashanah, 5643

Not while the snow-shroud round dead earth is rolled,

And naked branches point to frozen skies.—

When orchards burn their lamps of fiery gold,

The grape glows like a jewel, and the corn

A sea of beauty and abundance lies,

Then the new year is born.

Look where the mother of the months uplifts

In the green clearness of the unsunned West,

Her ivory horn of plenty, dropping gifts,

Cool, harvest-feeding dews, fine-winnowed light;

Tired labor with fruition, joy and rest

Profusely to requite.

Blow, Israel, the sacred cornet! Call

Back to thy courts whatever faint heart throb

With thine ancestral blood, thy need craves all.

The red, dark year is dead, the year just born

Leads on from anguish wrought by priest and mob,

what undreamed-of morn?

For never yet, since on the holy height,

The Temple’s marble walls of white and green

Carved like the sea-waves, fell, and the world’s light

Went out in darkness,—never was the year

Greater with portent and with promise seen,

Than this eve now and here.

Even as the Prophet promised, so your tent

Hath been enlarged unto earth’s farthest rim.

To snow-capped Sierras from vast steppes ye went,

Through fire and blood and tempest-tossing wave,

For freedom to proclaim and worship Him,

Mighty to slay and save.

High above flood and fire ye held the scroll,

Out of the depths ye published still the Word.

No bodily pang had power to swerve your soul:

Ye, in a cynic age of crumbling faiths,

Lived to bear witness to the living Lord,

Or died a thousand deaths.

In two divided streams the exiles part,

One rolling homeward to its ancient source,

One rushing sunward with fresh will, new heart.

By each the truth is spread, the law unfurled,

Each separate soul contains the nation’s force,

And both embrace the world.

Kindle the silver candle’s seven rays,

Offer the first fruits of the clustered bowers,

The garnered spoil of bees. With prayer and praise

Rejoice that once more tried, once more we prove

How strength of supreme suffering still is ours

For Truth and Law and Love.

Critic and Poet

An Apologue

No man had ever heard a nightingale,

When once a keen-eyed naturalist was stirred

To study and define—what is a bird,

To classify by rote and book, nor fail

To mark its structure and to note the scale

Whereon its song might possibly be heard.

Thus far, no farther;—so he spake the word.

When of a sudden,—hark, the nightingale!

Oh deeper, higher than he could divine

That all-unearthly, untaught strain! He saw

The plain, brown warbler, unabashed. “Not mine”

(He cried) “the error of this fatal flaw.

No bird is this, it soars beyond my line,

Were it a bird, ‘twould answer to my law.”

Age and Death

Come closer, kind, white, long-familiar friend,

Embrace me, fold me to thy broad, soft breast.

Life has grown strange and cold, but thou dost bend

Mild eyes of blessing wooing to my rest.

So often hast thou come, and from my side

So many hast thou lured, I only bide

Thy beck, to follow glad thy steps divine.

Thy world is peopled for me; this world’s bare.

Through all these years my couch thou didst prepare.

Thou art supreme Love—kiss me—I am thine!

Venus of the Louvre

Down the long hall she glistens like a star,

The foam-born mother of Love, transfixed to stone,

Yet none the less immortal, breathing on.

Time’s brutal hand hath maimed but could not mar.

When first the enthralled enchantress from afar

Dazzled mine eyes, I saw not her alone,

Serenely poised on her world-worshipped throne,

As when she guided once her dove-drawn car,—

But at her feet a pale, death-stricken Jew,

Her life adorer, sobbed farewell to love.

Here Heine wept! Here still he weeps anew,

Nor ever shall his shadow lift or move,

While mourns one ardent heart, one poet-brain,

For vanished Hellas and Hebraic pain.

Echoes

Late-born and woman-souled I dare not hope,

The freshness of the elder lays, the might

Of manly, modern passion shall alight

Upon my Muse’s lips, nor may I cope

(Who veiled and screened by womanhood must grope)

With the world’s strong-armed warriors and recite

The dangers, wounds, and triumphs of the fight;

Twanging the full-stringed lyre through all its scope.

But if thou ever in some lake-floored cave

O’erbrowed by rocks, a wild voice wooed and heard,

Answering at once from heaven and earth and wave,

Lending elf-music to thy harshest word,

Misprize thou not these echoes that belong

To one in love with solitude and song.

Night, and beneath star-blazoned summer skies

Behold the Spirit of the musky South,

A creole with still-burning, languid eyes,

Voluptuous limbs and incense-breathing mouth:

Swathed in spun gauze is she,

From fibres of her own anana tree.

Within these sumptuous woods she lies at ease,

By rich night-breezes, dewy cool, caressed:

‘Twixt cypresses and slim palmetto trees,

Like to the golden oriole’s hanging nest,

Her airy hammock swings,

And through the dark her mocking-bird yet sings.

How beautiful she is! A tulip-wreath

Twines round her shadowy, free-floating hair:

Young, weary, passionate, and sad as death,

Dark visions haunt for her the vacant air,

While noiselessly she lies

With lithe, lax, folded hands and heavy eyes.

Full well knows she how wide and fair extend

Her groves bright flowered, her tangled everglades,

Majestic streams that indolently wend

Through lush savanna or dense forest shades,

Where the brown buzzard flies

To broad bayous ’neath hazy-golden skies.

Hers is the savage splendor of the swamp,

With pomp of scarlet and of purple bloom,

Where blow warm, furtive breezes faint and damp,

Strange insects whir, and stalking bitterns boom—

Where from stale waters dead

Oft looms the great jawed alligator’s head.

Her wealth, her beauty, and the blight on these,—

Of all she is aware: luxuriant woods,

Fresh, living, sunlit, in her dream she sees;

And ever midst those verdant solitudes

The soldier’s wooden cross,

O’ergrown by creeping tendrils and rank moss.

Was hers a dream of empire? was it sin?

And is it well that all was borne in vain?

She knows no more than one who slow doth win,

After fierce fever, conscious life again,

Too tired, too weak, too sad,

By the new light to be or stirred or glad.

From rich sea-islands fringing her green shore,

From broad plantations where swart freemen bend

Bronzed backs in willing labor, from her store

Of golden fruit, from stream, from town, ascend

Life-currents of pure health:

Her aims shall be subserved with boundless wealth.

Yet now how listless and how still she lies,

Like some half-savage, dusky Indian queen,

Rocked in her hammock ’neath her native skies,

With the pathetic, passive, broken mien

Of one who, sorely proved,

Great-souled, hath suffered much and much hath loved!

But look! along the wide-branched, dewy glade

Glimmers the dawn: the light palmetto trees

And cypresses reissue from the shade,

And she hath wakened. Through clear air she sees

The pledge, the brightening ray,

And leaps from dreams to hail the coming day.

In Exile

“Since that day till now our life is one unbroken paradise. We live a true brotherly life. Every evening after supper we take a seat under the mighty oak and sing our songs.”—Extract from a letter of a Russian refugee in Texas.

Twilight is here, soft breezes bow the grass,

Day’s sounds of various toil break slowly off.

The yoke-freed oxen low, the patient ass

Dips his dry nostril in the cool, deep trough.

Up from the prairie the tanned herdsmen pass

With frothy pails, guiding with voices rough

Their udder-lightened kine. Fresh smells of earth,

The rich, black furrows of the glebe send forth.

After the Southern day of heavy toil,

How good to lie, with limbs relaxed, brows bare

To evening’s fan, and watch the smoke-wreaths coil

Up from one’s pipe-stem through the rayless air.

So deem these unused tillers of the soil,

Who stretched beneath the shadowing oak tree, stare

Peacefully on the star-unfolding skies,

And name their life unbroken paradise.

The hounded stag that has escaped the pack,

And pants at ease within a thick-leaved dell;

The unimprisoned bird that finds the track

Through sun-bathed space, to where his fellows dwell;

The martyr, granted respite from the rack,

The death-doomed victim pardoned from his cell,—

Such only know the joy these exiles gain,—

nLife’s sharpest rapture is surcease of pain.

Strange faces theirs, wherethrough the Orient sun

Gleams from the eyes and glows athwart the skin.

Grave lines of studious thought and purpose run

From curl-crowned forehead to dark-bearded chin.

And over all the seal is stamped thereon

Of anguish branded by a world of sin,

In fire and blood through ages on their name,

Their seal of glory and the Gentiles’ shame.

Freedom to love the law that Moses brought,

To sing the songs of David, and to think

The thoughts Gabirol to Spinoza taught,

Freedom to dig the common earth, to drink

The universal air—for this they sought

Refuge o’er wave and continent, to link

Egypt with Texas in their mystic chain,

And truth’s perpetual lamp forbid to wane.

Hark! through the quiet evening air, their song

Floats forth with wild sweet rhythm and glad refrain.

They sing the conquest of the spirit strong,

The soul that wrests the victory from pain;

The noble joys of manhood that belong

To comrades and to brothers. In their strain

Rustle of palms and Eastern streams one hears,

And the broad prairie melts in mist of tears.

. . . . . . . . . .

Emma Lazarus page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

I see it as it looked one afternoon

In August,— by a fresh soft breeze o’erblown.

The swiftness of the tide, the light thereon,

A far-off sail, white as a crescent moon.

The shining waters with pale currents strewn,

The quiet fishing-smacks, the Eastern cove,

The semi-circle of its dark, green grove.

The luminous grasses, and the merry sun

In the grave sky; the sparkle far and wide,

Laughter of unseen children, cheerful chirp

Of crickets, and low lisp of rippling tide,

Light summer clouds fantastical as sleep

Changing unnoted while I gazed thereon.

All these fair sounds and sights I made my own.

Work

Yet life is not a vision nor a prayer,

But stubborn work; she may not shun her task.

After the first compassion, none will spare

Her portion and her work achieved, to ask.

She pleads for respite,—she will come ere long

When, resting by the roadside, she is strong.

Nay, for the hurrying throng of passers-by

Will crush her with their onward-rolling stream.

Much must be done before the brief light die;

She may not loiter, rapt in the vain dream.

With unused trembling hands, and faltering feet,

She staggers forth, her lot assigned to meet.

But when she fills her days with duties done,

Strange vigor comes, she is restored to health.

New aims, new interests rise with each new sun,

And life still holds for her unbounded wealth.

All that seemed hard and toilsome now proves small,

And naught may daunt her,—she hath strength for all.

In the Jewish Synagogue at Newport (1871)

Here, where the noises of the busy town,

The ocean’s plunge and roar can enter not,

We stand and gaze around with tearful awe,

And muse upon the consecrated spot.

No signs of life are here: the very prayers

Inscribed around are in a language dead;

The light of the “perpetual lamp” is spent

That an undying radiance was to shed.

What prayers were in this temple offered up,

Wrung from sad hearts that knew no joy on earth,

By these lone exiles of a thousand years,

From the fair sunrise land that gave them birth!

How as we gaze, in this new world of light,

Upon this relic of the days of old,

The present vanishes, and tropic bloom

And Eastern towns and temples we behold.

Again we see the patriarch with his flocks,

The purple seas, the hot blue sky o’erhead,

The slaves of Egypt,—omens, mysteries,—

Dark fleeing hosts by flaming angels led.

A wondrous light upon a sky-kissed mount,

A man who reads Jehovah’s written law,

‘Midst blinding glory and effulgence rare,

Unto a people prone with reverent awe.

The pride of luxury’s barbaric pomp,

In the rich court of royal Solomon—

Alas! we wake: one scene alone remains,—

The exiles by the streams of Babylon.

Our softened voices send us back again

But mournful echoes through the empty hall:

Our footsteps have a strange unnatural sound,

And with unwonted gentleness they fall.

The weary ones, the sad, the suffering,

All found their comfort in the holy place,

And children’s gladness and men’s gratitude

‘Took voice and mingled in the chant of praise.

The funeral and the marriage, now, alas!

We know not which is sadder to recall;

For youth and happiness have followed age,

And green grass lieth gently over all.

Nathless the sacred shrine is holy yet,

With its lone floors where reverent feet once trod.

Take off your shoes as by the burning bush,

Before the mystery of death and God.

1492

Thou two-faced year, Mother of Change and Fate,

Didst weep when Spain cast forth with flaming sword,

The children of the prophets of the Lord,

Prince, priest, and people, spurned by zealot hate.

Hounded from sea to sea, from state to state,

The West refused them, and the East abhorred.

No anchorage the known world could afford,

Close-locked was every port, barred every gate.

Then smiling, thou unveil’dst, O two-faced year,

A virgin world where doors of sunset part,

Saying, “Ho, all who weary, enter here!

There falls each ancient barrier that the art

Of race or creed or rank devised, to rear

Grim bulwarked hatred between heart and heart!”

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 12 Poems by Emma Lazarus, creator of “The New Colossus” appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 15, 2019

Quotes from My Ántonia, Willa Cather’s Masterpiece

My Ántonia (1918) by American author, Willa Cather (1873 — 1947), was considered Cather’s first masterpiece. My Ántonia is the last book of her “prairie trilogy” of novels, preceded by O Pioneers! and The Song of the Lark.

The novel takes place in 19th-century Nebraska and tells the stories of an orphan boy from Virginia, Jim Burden, and the eldest daughter in an immigrant family from Bohemia, Ántonia Shimerda, who were each brought to be pioneers. There in the lifeless prairie, Ántonia makes friends and improves the condition of the land.

The first year in the prairie leaves lifelong impressions in both children, a theme that’s explored throughout the novel. Cather was highly praised for My Ántonia, giving life to the American West and making it fascinating to readers.

There is no question that Cather has written a book of singular beauty and simplicity, in which her power of giving the essence of a community is united with an immense capacity for character creation. Here are quotes from My Ántonia, an enduring classic novel by the prolific Willa Cather:

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“Some memories are realities and are better than anything that can ever happen to one again.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If there were no girls like them in the world, there would be no poetry.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I was something that lay under the sun and felt it, like the pumpkins, and I did not want to be anything more. I was entirely happy. Perhaps we feel like that when we die and become a part of something entire, whether it is sun and air, or goodness and knowledge. At any rate, that is happiness; to be dissolved into something complete and great. When it comes to one, it comes as naturally as sleep.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The country girls were considered a menace to the social order. Their beauty shone out too boldly against a conventional background.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The sky was growing pale, and that forgotten plow had sunk back to its own littleness somewhere in the prairie.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Now I understood that the same road was to bring us together again. Whatever we had missed, we possessed together the precious, the incommunicable past.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She’d always believe him. That’s Ántonia’s failing, you know; if she once likes people, she won’t hear anything against them.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Willa Cather on the Art of Fiction

. . . . . . . . . .

“The idea of you is part of my mind … you really are a part of me.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I was convinced that man’s strongest antagonist is the cold.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“This is reality, whether you like it or not — all those frivolities of summer, the light and shadow, the living mask of green that trembled over everything, they were lies, and this is what was underneath. This is the truth.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Whatever we had missed, we possessed together the precious, the incommunicable past.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“That is happiness; to be dissolved into something complete and great. When it comes to one, it comes as naturally as sleep.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There seemed to be nothing to see; no fences, no creeks or trees, no hills or fields. If there was a road, I could not make it out in the faint starlight. There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The prayers of all good people are good.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“As I went back alone over that familiar road, I could almost believe that a boy and girl ran along beside me, as our shadows used to do, laughing and whispering to each other in the grass.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“This was enough for Ántonia. She liked me better from that time on, and she never took a supercilious air with me again. I had killed a big snake – I was now a big fellow.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“More than any other person we remembered, this girl seemed to mean to us the country, the conditions, the whole adventure of our childhood.”

. . . . . . . . . .

My Ántonia by Willa Cather on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

“There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The eyes peering anxiously at me were—simply Ántonia’s eyes … She was there, in the full vigor of her personality, battered but not diminished.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Ántonia came up to me and held out her hand coaxingly. In a moment we were running up the steep draw side together.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I was thinking, as I watched her, how little it mattered– about her teeth, for instance. I know so many women who have kept all the things that she had lost, but whose inner glow has faded. Whatever else was gone, Antonia had not lost the fire of life.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I knew that I should never be a scholar. I could never lose myself for long among impersonal things. Mental excitement was apt to send me with a rush back to my own naked land and the figures scattered upon it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I knew it was homesickness that had killed Mr. Shimerda, and I wondered whether his released spirit would not … find its way back to his … country.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Things will be easy for you. But they will be hard for us.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I’ve seen a good deal of married life, and I don’t care for it. I want to … not have to ask lief of anybody.”

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1918 review of My Ántonia

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from My Ántonia, Willa Cather’s Masterpiece appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Dear Literary Ladies, Part One: Writing Advice From Classic Women Authors

Wouldn’t it be great to get writing advice from women authors — some of the most iconic voices in literature — even (or especially) those who are no longer with us? Here’s your chance! In this first of a multi-part series of roundups we call “Dear Literary Ladies” We’ve “asked” classic women authors some of the universal questions about writing and the writer’s life, and found the answers in their first-person musings.

Peering through the lens of the past is an intriguing way to examine issues and questions that linger into the present. It’s now easier and more acceptable for women to write both for pleasure as well as profit, to be sure. However, it’s still challenging to find the will and focus to do so while raising children, to get that first work published, to make a living by writing, and above all, to have courage to send one’s words into the world.

It’s still painful to face rejection, and daunting to experience writer’s block. Self-doubt is part of the creative process, no matter what the era. There are no hard and fast rules. Louisa May Alcott responded to many of her readers’ letters asking for advice on writing. To these she responded with variations on “Each person’s method is no rule for another. Each must work in [her] own way, and the only drill needed is to keep writing…”

Dear Literary Ladies, Part One Don't you wish you could get writing advice from your favorite women authors, especially those who have created great classics? Here's your chance! We've "asked" some of our classic women authors the burning questions about the writer's life and tools of the trade, and found the answers in their first-person musings. What's your best advice for beginning writers?

What's your best advice for beginning writers?What's your best advice for beginning writers, or really, anyone who’s trying to write regularly? Octavia Butler answers ...

Continue Reading Continue Reading How can a writer balance solitude and camaraderie?

How can a writer balance solitude and camaraderie?When I’m alone working, I feel the need for feedback; and when I’m in the company of other writers and talk about my work, I feel I’m seeking too much outside validation. How can a writer balance the need for quiet and solitude, with the desire for camaraderie? Sarah Orne Jewett answers ...

Continue Reading Continue Reading Should writers draw characters and plots from real life?

Should writers draw characters and plots from real life?How much should real life supply a writer with characters and plots? Should we be looking for people to base our fictional characters on, and stories upon which to model our plots? Ivy Compton-Burnett answers ...

Continue Reading Continue Reading Should you write for an audience, or to please yourself?

Should you write for an audience, or to please yourself?Do you write for an audience or market as a work is in progress, or does that ultimately make for a less desirable outcome? Is it better to write to please yourself? Edna Ferber answers ...

Continue Reading Continue Reading How do you develop the discipline to write?

How do you develop the discipline to write?If the words don’t flow right away, I’ll get up and find some fine excuse not to stick with it. How do you develop the discipline to just sit down and write? Madeleine L'Engle answers ...

Continue Reading Continue Reading Do I have enough wisdom to be a good writer?

Do I have enough wisdom to be a good writer?Sometimes I feel that I don’t have enough life experience to be a good writer. Should I wait until I’ve lived more fully, and gain some wisdom, before I bare my soul to the public in writing, or should I just plow ahead? Zora Neale Hurston answers ...

Continue Reading Continue Reading Is it better to be a modest success than to risk failure?

Is it better to be a modest success than to risk failure?I admit that I’m afraid to fail— and then look foolish to myself and others. Do you think it’s better to stick with what you do best, rather than stick your neck out and possibly fail? Vita Sackville-West answers ...

Continue Reading Continue Reading Any quick tips for plot and character development?

Any quick tips for plot and character development?Can you share some quick insights on how you developed plots and characters? Louisa May Alcott answers ...

Continue Reading Continue Reading What goes through your mind when you feel blocked?

What goes through your mind when you feel blocked?You seem like such a prolific author, but like the rest of us who live by our pen, you likely feel blocked from time to time. How does this uncomfortable and sometimes scary feeling play out in your mind? Fannie Hurst answers ...

Continue Reading Continue Reading Does one need connections to get published?

Does one need connections to get published?I’ve often heard it said that “it’s who you know that matters.” Well, I don’t know anyone in the publishing world. Does that mean my work doesn’t stand a chance of being looked at seriously? Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings answers ...

Continue Reading Continue Reading How can I develop a distinctive writing style?

How can I develop a distinctive writing style?How do I go about developing a distinctive writing style—one that will catch editors' attention, and that readers everywhere will recognize as my unique voice? Katherine Anne Porter answers ...

Continue Reading Continue Reading See more in our Writing Advice from Classic Authors categoryThe post Dear Literary Ladies, Part One: Writing Advice From Classic Women Authors appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 14, 2019

The Member of the Wedding by Carson McCullers (1946)

The Member of the Wedding (1946) was Carson McCullers’ third novel, published when she she was just twenty-eight. It followed the incredibly successful The Heart is a Loney Hunter (1940), published when McCullers was just twenty-three.

The story centers on a lonely twelve-year-old girl, Frankie Addams, who prefers to be known as F. Jasmine. Her mother has died, and her father, a jeweler, treats her with benign neglect. The story takes place during a hot summer in a small Georgia town, finding Frankie consumed with worry that she doesn’t belong anywhere or with anyone.

For company, Frankie has her six-year-old cousin, John Henry West, and Berenice Sadie Brown, the African-American cook employed by her father. Her dull existence is shaken up when her older brother Jarvis, an army veteran, announces that he is to be married to Janice Evans.

Frankie’s daydreams become ever more vivid and emotionally charged as she imagines that she might not only be a member of the wedding, but that she will be invited to go on the honeymoon with her brother and his bride. She now wants to be called “F. Jasmine,” to share the first two letters of the names of Jarvis and Janice.

The slim novel is a portrait of the interior workings of F. Jasmine’s adolescent mind as she fixates on the wedding and contends with the insular small town that she inhabits.

The Detroit Free Press, in its 1946 concluded, “This is a marvelous study of the agony of adolescence, the fierce desire which breeds fierce denial, the inner loneliness which expresses itself perversely in violence.”

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Carson McCullers

. . . . . . . . .

For a more contemporary perspective, in a 2012 installment of The Guardian series, Overlooked American Classics, Tom Cox wrote,

“It’s an innocent, twinkling kind of backstory to accompany what could, from a distance, seem like an innocent, twinkling kind of book. Close inspection reveals it most definitely isn’t. With its portrait of pre-teen awkwardness and self-delusion, The Member Of The Wedding has attracted youthful fans … Much of the activity is interior – either inside Frankie’s head, or in the kitchen, where she tells her family’s black cook, Berenice, of her plans to leave town with Janice and Jarvis. When something that might be construed as ‘action’ does finally occur, it’s shockingly dark: an incident involving a soldier who mistakenly believes Frankie to be much older than she is.”

Here are two reviews from the many that this book received upon its publication in the spring of 1946:

Growing pains

From the original review of The Member of the Wedding by Carson McCullers in Council Bluffs Nonpareil, March 1946: Carson McCullers’ third novel, The Member of the Wedding, is the story of Frankie, a girl on the dizzy edges of becoming a young woman.

The scene is a small Georgia town. Besides Frankie, or F. Jasmine as she later becomes, or Frances as she is named grandly a few weeks later when the novel of which she is the heroine closes, there are also young John Henry West; and Berenice Sadie Brown, who speaks out of the wisdom which can only come to a woman who has had four husbands; Frankie’s father; her brother and his bride.

Frankie is almost five feet and a half tall in the “green and crazy summer” when this story takes place. Shooting up like a beanstalk, adding four inches almost overnight, she is worried.

Being 12 years and 10 months old, she is worried too, about what she has done with Barney; about the way the other girls had suddenly abandoned her to form a club of their own so that practically the only thing left in the whole world for her to be a member of is her brother’s wedding.

Though recent writers have devoted more time to the adolescent than the so-called modern parent is ever credited with doing, this is a different kind of story. A knife is thrown, a pistol stolen out of a father’s dresser, a fellow’s head bashed in.

And there’s a macabre touch; it isn’t only what happens that thrills you, but even more, what incessantly threatens to happen. A sword of Damocles, 12-year-old size, hands over this tale from start to finish.

. . . . . . . . .

The Member of the Wedding by Carson McCullers on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

The awkwardness and violent emotions of adolescenceFrom the original review in The Palm Beach Post, April 7, 1946: Carson McCullers’ first novel, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter , and her second, Reflections in a Golden Eye ,won great critical acclaim. Their appeal, or lack thereof, was similar to the question of one’s tase for ultra modern trends in art.

For this reader, at least, The Member of the Wedding seems much more readable. There is little action, the characters few and eccentric, but the author definitely evokes a mood and creates an atmosphere. Adolescence is a favored subject, and seldom has an author captured more poignancy the emotional ups and downs of a neglected child, standing at the brink of her teens, unsure of herself, fearful of unpopularity, subject to the unhappiness and despair that comes from lack of perspective by which to judge, and common sense by which to be guided.

Twelve-year-old Frankie is the main character. This is the story of one summer in her life. Her father was away all day, she was at outs with the girls her own age, excluded from their secrets and their clubs, thrown back for companionship on her curious little six-year-old cousin, John Henry, and Berenice, her family’s African-American cook.

The high point of excitement the dull, dreary summer offered was the approaching marriage of her brother, who had been with the Army in Alaska, to an unknown girl in a nearby town. Frankie’s father is taking her to the wedding, and with childish intensity she latches on to this one happening as a great climax in her life. In her imagination she identifies herself has part of the wedding party, determines that she will ask her brother to take her with them on the honeymoon, persuades herself that he will do so.

The great part of the story centers around her preparations for the wedding, her preoccupation with her daydreams, her emergence into the reality of the kitchen with Berenice and John Henry, her despair after the wedding did not turn out as she had made herself believe.

Throughout it all she passes virtually in a daze with the drama of a small Southern city, its tragedies and its daily life, leaving her virtually untouched. At the end with the formation of one tangible friendship, Frankie gains new interests, and shows some signs of reverting to normalcy.

Though the story could hardly be termed typical, Carson McCullers has managed to convey the sensitivity of an exceptional chid, with all the violence of emotion and awkwardness of this age.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: The Ballad of the Sad Café by Carson McCullers

. . . . . . . . . .

It happened that green and crazy summer when Frankie was twelve years old. This was the summer when for a long time she had not been a member. She belonged to no club and was a member of nothing in the world. Frankie had become an unjoined person who hung around in doorways, and she was afraid.

In June the trees were bright dizzy green, but later the leaves darkened, and the town turned black and shrunken under the glare of the sun. At first Frankie walked around doing one thing and another. The sidewalks of the town were gray in the early morning and at night, but the noon sun put a glaze on them, so that the cement burned and glittered like glass.

The sidewalks finally became too hot for Frankie’s feet, and also she got herself in trouble. She was in so much secret trouble that she thought it was better to stay at home—and at home there was only Berenice Sadie Brown and John Henry West.

The three of them sat at the kitchen table, saying the same things over and over, so that by August the words began to rhyme with each other and sound strange. The world seemed to die each afternoon and nothing moved any longer. At last the summer was like a green sick dream, or like a silent crazy jungle under glass. And then, on the last Friday of August, all this was changed: it was so sudden that Frankie puzzled the whole blank afternoon, and still she did not understand …

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers

. . . . . . . . . .

“You have a name and one thing after another happens to you, and you behave in various ways and do things, so that soon the name begins to have a meaning. Things have accumulated around your name.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She was afraid of these things that made her suddenly wonder who she was, and what she was going to be in the world, and why she was standing at that minute, seeing a light, or listening, or staring up into the sky: alone.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There are all these people here I don’t know by sight or by name. And we pass alongside each other and don’t have any connection. And they don’t know me and I don’t know them. And now I’m leaving town and there are all these people I will never know.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The trouble with me is that for a long time I have just been an I person. All people belong to a We except me. Not to belong to a We makes you too lonesome.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It was better to be in a jail where you could bang the walls than in a jail you could not see.”

. . . . . . . . . .

More about The Member of the Wedding

Wikipedia Reader discussion on Goodreads Film version of The Member of the Wedding. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Member of the Wedding by Carson McCullers (1946) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 11, 2019

The Life of Charlotte Brontë by Elizabeth Gaskell (1857)

Charlotte Brontë (1816 – 1855) outlived all five of her siblings, including her literary sisters, Emily and Anne. The grief at losing her sisters at ages thirty and twenty-nine, respectively, may have been easing with the happiness she found as the wife of Arthur Bell Nichols, and the widespread recognition of her talents as a writer.

Jane Eyre, Shirley, and Villette had all been published, and Charlotte was recognized as a major talent. Her books sold well, too. And though she was still known as “Currer Bell,” the male pseudonym she’d use to break into the publishing world, her true identity had been established.

But it was not to last. When Charlotte died of complications due to pregnancy in 1855, she had nearly reached her thirty-ninth birthday. Two years after her death, The Professor, the first novel Charlotte had written, but which remained unpublished in her lifetime first novel, was published. The Life of Charlotte Brontë by Elizabeth Gaskell was also published that same year (1857), helping to seal her legacy and reputation. Mrs. Gaskell, as she was known, was at the time also a respected novelist, having published Mary Barton and Ruth.

The project was approved by Charlotte’s father, Patrick Brontë, a curate, who had by that time outlived all of his six children. He, in fact, made the first overture to Mrs. Gaskell barely three months after Charlotte died. The first edition of The Life of Charlotte Brontë was published by Charlotte’s publisher, Smith, Elder, & Co. Mrs. Gaskell drew much of the material from Charlotte’s letters to her dear friend, Ellen Nussey.

. . . . . . . . . .

Charlotte, in a portrait by George Richmond, 1850

. . . . . . . . . .

Though the biography is considered quite credible and fairly thorough, there were some matters that needed to be downplayed. Notably, one was Charlotte’s years-long one-sided romantic obsession with Constantin Héger. He was the headmaster of the school she had attended in Brussels to train as a teacher while already a young adult, and the inspiration for her first novel, The Professor. To have gone overboard in describing Charlotte’s obsession with this married man would have been considered unseemly for its time.

As recently as 2017, The Life of Charlotte Brontë was listed in The Guardian (UK) as one of the 100 best nonfiction books of all time! Charlotte was a literary star on both sides of the Atlantic, so it was exciting to find this 1857 review published in a Washington, D.C., newspaper:

An 1857 review of The Life of Charlotte Brontë

An original review dated June 4, 1857, The National Era, Washington, D.C.: A sadder book than this we have never read. The very volumes which gave to Charlotte Brontë her brilliant reputation are less sad, less gloomy than this — the true story of her life. It is only through this sorrowful tale that her books can be understood — it is only after reading it, that we can do her justice.

The early years of Charlotte Brontë were spent in one of the bleakest portions of Yorkshire Around her were wide stretches of moors.Her home was an old, cheerless parsonage, fronting a gloomy graveyard. In the home, no mother’s gentle voice was heard, for she died when the children were young.

And the father, Patrick Brontë, though possessed of many good qualities, was stern, unapproachable, and unsocial. The house was not a home, as this word is understood. Three sisters and a brother grew up together [two other sisters, who had been the eldest, died around their respective tenth birthdays], isolated from the outside world, with strange views and feelings, and with intellects diseased by their singular mode of life. This was the result of their narrow income and position, and the pure choice of the father.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Brontë Sisters’ Path to Publication

. . . . . . . . . .

The only son, Branwell, grew up without the means to perfect his education, and was seduced from the paths of virtue by a married woman twice his age. He become dissipated at an early age, filling the inebriate’s grave.

Charlotte and her sisters Emily and Anne were subjected to close contact with this ruined young man, and saw him hasten day by day to his horrible end. From the father and brother, the sisters drew their ideas of men, for they saw few others.

In their poverty, the sisters resorted to the occupation of teaching in private families, and experienced all that was cruel, cutting, and degrading, in that sphere of labor. The exertions of such a profession sowed the seeds of consumption in her sisters, who, one after the other, fell into untimely graves — not, however, till each had written a story, as full of gloom and shadows as their own lives had been.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Professor by Charlotte Brontë

. . . . . . . . . .

The first story Charlotte wrote, The Professor, was rejected by six publishers. Jane Eyre first burst upon the world, and, like Byron, Charlotte woke up one morning and found herself famous. But fame did not give her happiness. It was only the last year of her life, when, at the age of nearly thirty-nine, she was married to a man she truly loved, that she was happy. It was her first happiness on earth — and it was quickly taken away.

To read The Life of Charlotte Brontë is to unfold the realities of her novels; for her life was incorporated into her stories. If they were terrible, so was her life. If her characters were in some respects repulsive and shocking, so were the real characters of her life. No one can read these volumes without acknowledging that he or she has been gazing at the lineaments of a strange and wonderful genius.

. . . . . . . . . .

Jane Eyre: A 19th-Century Analysis

. . . . . . . . . .

A woman of heroic character

Charlotte Brontë was a woman of heroic character, of great nobility of heart. Sorrows which would have crushed others, or driven them made, seemed by to sadden her, and add gloom to her soul. Not for a moment did she give way, but continued her steady work, her life of unremitting industry.

The life, so far as its author, Mrs. Gaskell, is concerned, is admirably done. Her style is at once beautiful and concise. With the utmost delicacy, she has told every fact necessary to a just appreciation of the character of the subject of the memoir. The book will take its place among the very best biographies, and will live, with Jane Eyre and Villette, of the English language.

It was not alone to satisfy curiosity or to amuse the book-reading world that it was written, but to justify the character of the gifted woman, who has been so severely criticized in some quarters. Let he or she who has lived without the joys of home, who never saw a mother’s face, who has trod upon the fiery coals of anguish because of ruin and disgrace in the home circle — who has buried, one by one, all but one of a household — who has, through all of this, rarely uttered a word of complaint — be the first to criticize Charlotte Brontë or her works.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Life of Charlotte Brontë by Elizabeth Gaskell is available on Amazon,

or can be read online at Project Gutenberg and other sources

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Life of Charlotte Brontë by Elizabeth Gaskell (1857) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 9, 2019

The Mandarins by Simone de Beauvoir

The Mandarins by Simone de Beauvoir is a semi-autobiographical novel published in her native French in 1954, and in English translation in 1956. The same year it was published in France, it won the prestigious literary prize, the Prix Goncourt. When it was published outside of France, de Beauvoir was best known (as she is still today, perhaps) for her 1949 nonfiction book, The Second Sex, a feminist classic.

The Mandarins encompasses many of de Beauvoir’s favored themes, including existentialism, feminism, political structures (including communism), and morality.

The novel portrays a group of a close-knit group of friends who call themselves “the Mandarins” — referring to the scholar-bureaucrats of imperial China. The core group of characters identify as intellectuals, and grapple with what kind of role they might play in post World-War II Europe.

One of the couples portrayed in the book, Anne and Robert Dubreuilh, are supposedly based on de Beauvoir herself and her longtime partner, Jean-Paul Sartre. The fictional couple is married, whereas their real-life counterparts had a long-term open relationship. Not surprisingly, the novel explores the shifting love affairs of its main characters.

The Mandarins received much critical acclaim from major publications like the New York Times (“Much more than a roman a clef … a moving and engrossing novel …”) as well as minor ones like the one following, published upon the book’s American debut:

On the Left Bank, celebrating post-war freedom

From the review by Melva Chernoff of The Mandarins by Simone de Beauvoir in the Argus-Leader, Sioux Falls, SD, July 1, 1956:

It was with her monumental The Second Sex that Simone de Beauvoir achieved the recognition in the U.S. she had already received in Europe. Here, as there, it was hailed as a classic study of what it means to be a woman. With the U.S. publication of She Came to Stay in 1954, de Beauvoir enlarged her reputation as a novelist of the first rank, capturing the praise and acclaim of critics throughout America.

It begins in Paris, Christmas Eve, 1944. In an apartment on the Left Bank are gathered a group of friends who are free again, as Paris is free after World War II, to celebrate, sing, and talk — and to dream and plan a future which will bring them happiness and which will create a fuller, finer world.

Unwilling to leave the fate of France in the hands of politicians and struggling against the lure of communism, these characters bring a new interpretation of post-liberation France to the American who is only casually aware of the political scene.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir

. . . . . . . . . .

This is an exciting novel, with characters as exciting as they come alive in all their strengths and weaknesses: Henri Perron, successful novelist and journalist, hero of the Resistance, and owner and editor of L’Espoir, and independent newspaper he has founded. Then there is the beautiful Paula, for whom loving Henri is life enough. Finally, there is Robert Dubreuilh, a philosopher and writer, and his psychoanalyst wife, Anne, their daughter Nadine, and those who touch and change their lives.

Remember the story of the blind men who were asked to describe an elephant? As one felt the trunk he termed the elephant a snake. Another man reached around one leg of the beast and said, “Surely, this is a great tree.” The third blind man was sure he was facing a wall as his hands felt along the elephant’s side. So The Mandarins will be many different books to different people coming to it with their personal perspectives.

This is a love story. This is many love stories. Here are tired, waning passions and selfish, youthful love. Anne discovers that middle age is no barrier to a dramatic and moving love affair. This passion alone, described with great frankness and understanding, would make a novel in itself. Of love and what passes in its name, The Mandarins has plenty.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Mandarins by Simone de Beauvoir on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

This is also a novel of philosophical conflicts. Mlle. de Beauvoir makes a strong argument for the necessity of compromise. American readers may not fully appreciate the compromises that are made, but they seem inevitable from the viewpoint of the French “mandarins.”

These intellectuals find communism the only solution to their political situation. They must, as the Existentialists say, “engage” themselves with responsibility and action. The idea of turning to America is presented as a possibility by only the weak and questionable characters.

France cannot stand alone. Therefore she must turn to communism as a lesser evil, according to some of the characters in the story. In that manner we have in The Mandarins a novel of political interest as well.

A word about the characters: They are real, vivid, and human. You will find in them parts of yourself. And you may find yourself coming back to this powerful novel, in thought and in re-reading — whether you read it as a love story, a political novel, or an intellectual experience.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir

. . . . . . . . . .

“I could see no reason for being sad. It´s just that it makes me unhappy not to feel happy.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“All the opportunities you let slip by! The idea, the inspiration just doesn´t come fast enough. Instead of being open, you´re closed up tight. That´s the worst sin of all — the sin of omission.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She was ready to deny the existence of space and time rather than admit that love might not be eternal.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Surviving one’s own life, living on the other side of it like a spectator, is quite comfortable after all. You no longer expect anything, no longer fear anything, and every hour is like a memory.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“He formed his sentences hesitantly and then threw them at me with such force that I felt as if I were receiving a present each time”

. . . . . . . . . .

More about The Mandarins

Wikipedia Reader discussion on Goodreads An original review translated from French. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing

The post The Mandarins by Simone de Beauvoir appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 8, 2019

The 1994 Film Adaptation of Little Women, Louisa May Alcott’s Timeless Classic

Little Women, the beloved 1868 novel by Louisa May Alcott (1832 – 1888), follows the lives of the four March sisters — Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy. The 1994 film adaptation of Little Women highlighted the coming of age of strong-willed, tomboyish Jo, who was as much of its standout character as she was in the novel.

With a screenplay by Robin Swicord, and directed by Gillian Armstrong (also the director of the wonderful 1979 film version of My Brilliant Career) , this was the fifth feature film adaptation of Alcott’s classic Little Women. It followed silent versions released in 1917 and 1918; director George Cukor’s 1933 film; and a 1949 adaptation by Mervyn LeRoy. The film was released nationwide on Christmas Day of 1994 by Columbia Pictures.

The focus of the film is on the March sisters, growing up in Concord, Massachusetts during and after the American Civil War. As their father is away fighting in the war, the girls struggle with both major and minor problems under the watch of their firm yet loving mother, Marmee. The girls perform romantic plays written by Jo in their attic theater to escape their humdrum reality.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like:

10 Writers Who Were Inspired by Jo March of Little Women

. . . . . . . . . .

“Some books are so familiar, reading them is like being home again.” Though Jo March was talking about Shakespeare, we’re all aware that Little Women is a nostalgic novel that gives viewers the same warm feeling.

In the film review “The Gold Standard Girlhood Across America,” by Janet Maslin in The New York Times, December 1994:

“Ladies, get out your hand-hemmed handkerchiefs for the loveliest Little Women ever on screen. Armstrong’s film is enchantingly pretty and so potent that from the start of the opening frame, it prompts a rush of recognition. She clearly demonstrates that she mastered the essence of the book’s sweetness and chose young vibrant actresses who were absolutely right for their famous roles.

The effect of the film on its viewers is magical and for all its unimaginable innocence, the film has a touching naturalness this time.”

Maslin was pleasantly surprised as she said that the film is “sentimental without being saccharine.” She claims that the filmmaker is “too savvy to tell this story in a cultural and historical vacuum.”

. . . . . . . . . .

How Louisa May Alcott Came to Write Little Women

. . . . . . . . . .

Once the March sisters made their introductory embraces, the personalities of their four familiar March sisters emerge. As the film progresses, the audience gradually gets to know their personalities and how they relate to one another.

Winona Ryder plays the tomboy Jo exceptionally well as she performs with spark and confidence. She is the self-proclaimed “man of the family” with just a perfect touch of perseverance. Her presence in the film adds an appealing and refreshing linchpin to the classic film.

The perfect contrast to Jo is scene-steaming Amy, played by Kirsten Dunst. Her character is vain and mischievous, fitting for an 11-year-old rather than the grown-up Joan Bennett from the 1933 movie version of the novel.

Meg has a ladylike composure, which Trini Alvarado captures exceptionally well. Her role as the oldest and most marriageable of the sisters was not only perfect for the 1994 film, but it was also a perfect showcase for her versatility and dramatic ability.

Beth, played by Claire Danes, instantly gains the sympathy of the audience as the sickly one. Throughout the film, Beth is relatively selfless character, and after her somber death, viewers may find themselves reduced to tears.

There may not be much action in the film, but that’s how life typically was for women in the 19th century. They came together and talked endlessly about their hopes, dreams, and mostly, their marital destinies.

. . . . . . . . . .

Little Women: A Book I Come Back to for Comfort and Guidance

. . . . . . . . . .

Robert Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times wrote in his 1994 review that “Little Women grew on me. At first, I was grumpy, thinking it was going to be too sweet and devout. Gradually, I saw that Gillian Armstrong […] was taking it seriously. And then I began to appreciate the ensemble acting, with the five actresses creating the warmth and familiarity of a real family,” said He awarded the film 3 ½ stars, calling it “a surprisingly sharp and intelligent telling of Alcott’s famous story.”

Edward Guthmann of the San Francisco Chronicle claimed that the film was “meticulously crafted and warmly acted.” He observed it as a rare Hollywood studio film that captivated the interest of the audience with effects and easy manipulation.

Awards and Nominations

This 1994 film was nominated for three Academy Awards, including Best Actress for Winona Ryder, Best Costume Design for Colleen Atwood (also nominated for the BAFTA Award in the same category), and Best Original Score for composer Thomas Newman, who also won the BMI Film Music Award.

Winona Ryder was given the title of Best Actress by the Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards. Kirsten Dunst was honored for her performance in both Little Women and Interview With the Vampire by the Boston Film Society of Film Critics. Additionally, she was also given the Young Artist Award.

Screenplay creator Robin Swicord was nominated for the Writers Guild of America Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. Unfortunately, he lost to Eric Roth for Forrest Gump.

Among contemporary critics, Little Women has received an impressive and well-deserved 91% score on Rotten Tomatoes saying, “Thanks to a powerhouse lineup of talented actresses, Gillian Armstrong’s take on Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women proves that a timeless story can succeed no matter how many times it’s told.”

And you don’t have to wait too long for another iteration. A new film version of Little Women will be released in December of 2019. What a cast! It will star Saoirse Ronan as Jo; Emma Watson as Meg; Laura Dern as Marmee; Meryl Streep as Aunt March; Timothée Chalamet as Laurie, and many more talents whose names may not be as well known, but whose faces as the supporting characters in Little Women soon will be.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The 1994 Film Adaptation of Little Women, Louisa May Alcott’s Timeless Classic appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 5, 2019

12 Poems by Christina Rossetti, Victorian Poet

Christina Georgina Rossetti (1830 – 1894) is one of the most enduring and beloved of Victorian poets. Born in London, she was youngest of four artistic and literary siblings, the best known of whom is the pre-Raphaelite poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Her long poem Goblin Market, is perhaps her most famous work. She was praised by her contemporaries, including Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and was considered by some as the natural successor to Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Christina Rossetti’s poetry reflected her devotion, passion, pensiveness, and occasionally, playfulness.

Symbolism and lyricism used in her work expressed earthly love and divine inspiration. Her poetry touched on themes of nature, death, and sexuality. Being deeply religious, she took much inspiration from the Bible and the lives of the saints. Rossetti began writing poetry at a young age; by sixteen she had written more than fifty poems. She wrote prolifically throughout her life, experimenting with various forms such as hymns, sonnets, and ballads.

Though she wrote several works of fiction and nonfiction, it’s for her poetry that Christina Rossetti is best remembered. In her lifetime as well as posthumously she had several collections of poetry published, including:

Following is a sampling of poems by Christina Rossetti, a small taste of her vast body of work:

. . . . . . . . . .

EchoCome to me in the silence of the night;

Come in the speaking silence of a dream;

Come with soft rounded cheeks and eyes as bright

As sunlight on a stream;

Come back in tears,

O memory, hope, love of finished years.

O dream how sweet, too sweet, too bitter sweet,

Whose wakening should have been in Paradise,

Where souls brimfull of love abide and meet;

Where thirsting longing eyes

Watch the slow door

That opening, letting in, lets out no more.

Yet come to me in dreams, that I may live

My very life again though cold in death:

Come back to me in dreams, that I may give

Pulse for pulse, breath for breath:

Speak low, lean low

As long ago, my love, how long ago.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like: Goblin Market by Christina Rossetti

. . . . . . . . . .

Remember me when I am gone away,

Gone far away into the silent land;

When you can no more hold me by the hand,

Nor I half turn to go yet turning stay.

Remember me when no more day by day

You tell me of our future that you plann’d:

Only remember me; you understand

It will be late to counsel then or pray.

Yet if you should forget me for a while

And afterwards remember, do not grieve:

For if the darkness and corruption leave

A vestige of the thoughts that once I had,

Better by far you should forget and smile

Than that you should remember and be sad.

. . . . . . . . . .

Fata MorganaA blue-eyed phantom far before

Is laughing, leaping toward the sun:

Like lead I chase it evermore,

I pant and run.

It breaks the sunlight bound on bound:

Goes singing as it leaps along

To sheep-bells with a dreamy sound

A dreamy song.

I laugh, it is so brisk and gay;

It is so far before, I weep:

I hope I shall lie down some day,

Lie down and sleep.

. . . . . . . . . .

Fluttered WingsThe splendour of the kindling day,

The splendor of the setting sun,

These move my soul to wend its way,

And have done

With all we grasp and toil amongst and say.

The paling roses of a cloud,

The fading bow that arches space,

These woo my fancy toward my shroud,

Toward the place

Of faces veil’d, and heads discrown’d and bow’d.

The nation of the awful stars,

The wandering star whose blaze is brief,

These make me beat against the bars

Of my grief;

My tedious grief, twin to the life it mars.

O fretted heart toss’d to and fro,

So fain to flee, so fain to rest!

All glories that are high or low,

East or west,

Grow dim to thee who art so fain to go.

. . . . . . . . . .

Dream LandWhere sunless rivers weep

Their waves into the deep,

She sleeps a charmed sleep:

Awake her not.

Led by a single star,

She came from very far

To seek where shadows are

Her pleasant lot.

She left the rosy morn,

She left the fields of corn,

For twilight cold and lorn

And water springs.

Through sleep, as through a veil,

She sees the sky look pale,

And hears the nightingale

That sadly sings.

Rest, rest, a perfect rest

Shed over brow and breast;

Her face is toward the west,

The purple land.

She cannot see the grain

Ripening on hill and plain;

She cannot feel the rain

Upon her hand.

Rest, rest, for evermore

Upon a mossy shore;

Rest, rest at the heart’s core

Till time shall cease:

Sleep that no pain shall wake;

Night that no morn shall break

Till joy shall overtake

Her perfect peace.

. . . . . . . . . .

Eve‘While I sit at the door

Sick to gaze within

Mine eye weepeth sore

For sorrow and sin:

As a tree my sin stands

To darken all lands;

Death is the fruit it bore.

‘How have Eden bowers grown

Without Adam to bend them!

How have Eden flowers blown

Squandering their sweet breath

Without me to tend them!

The Tree of Life was ours,

Tree twelvefold-fruited,

Most lofty tree that flowers,

Most deeply rooted:

I chose the tree of death.

‘Hadst thou but said me nay,

Adam, my brother,

I might have pined away;

I, but none other:

God might have let thee stay

Safe in our garden,

By putting me away

Beyond all pardon.

‘I, Eve, sad mother

Of all who must live,

I, not another

Plucked bitterest fruit to give

My friend, husband, lover—

O wanton eyes, run over;

Who but I should grieve?—

Cain hath slain his brother:

Of all who must die mother,

Miserable Eve!’

Thus she sat weeping,

Thus Eve our mother,

Where one lay sleeping