Nava Atlas's Blog, page 73

February 15, 2019

Harriet Ann Jacobs

Harriet Ann Jacobs (February 11, 1813 – March 7, 1897) was an African-American writer who was widely known for her brave escape from slavery, and for her role as an abolitionist, speaker, and reformer. She is alternately referred to as Harriet A. Jacobs or simply Harriet Jacobs.

Raised in Edenton, North Carolina, Harriet and her brother John were born into slavery under the principle of partus sequitur ventrem (that which is brought forth follows the womb). This meant they were born into slavery because their mother was already enslaved. However, it wasn’t until Harriet turned six that she even learned she was a slave.

“Though we were all slaves, I was so fondly shielded that I never dreamed I was a piece of merchandise, trusted to them for safe keeping…”

When Harriet was six her mother died, sending her and her brother to live with her mother’s owner and mistress, Margaret Horniblow, where Harriet was graciously welcomed. Here she learned to read, write, and sew, and had a relatively happy life until her owner’s death in 1825.

In her owner’s will, it was said that Harriet was bequeathed to her three-year-old niece, Mary Matilda. Since Mary was too young, Harriet went under the rule of Mary’s father, Dr. James Norcom.

Escape to freedom

After years of unwanted sexual advances from Dr. Norcom, and the copious amounts of jealousy from his wife, Mrs. Norcom, Harriet found love with a white lawyer in town, with whom she had two children with. In an act of retaliation for the birth of her children, Dr. Norcom sent Harriet to one of his plantations where she worked as a field slave for the first time in her life.

In fear that Norcom would send her children to the plantation with her, Harriet escaped and went into hiding before he had the chance. She hid in a small space in her grandmother’s front porch roof, between 1835 and 1842. For seven years she tried to reunite with her children by trying to trick Norcom into selling them, something that unfortunately never happened.

In 1842 Harriet escaped from her grandmother’s home and traveled to Edenton, which eventually led to New York. Here she worked as a nursemaid for the family of abolitionist Nathaniel Parker Willis and his wife Cornelia Grinnell Willis. She remained hidden in order to escape capture by Dr. Norcom who continuously tried to re-enslave her until her freedom was bought in 1852.

After the Willis family bought Harriet’s freedom, the journey to reunite with her children began. Traveling between New York and Boston over the next few years finally gave her that reunion she had been dreaming of for years.

. . . . . . . . . .

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet A. Jacobs

. . . . . . . . . .

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

During her years traveling between Boston and New York, Harriet became very active in a group of anti-slavery feminists. Here is where she met Amy Post, who would, along with Marry Willis, encourage Harriet to write the story of her life. This is where the idea for Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl was born.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl was one of the first books that addressed the fight for freedom by female slaves, that documented their struggles with sexual abuse and harassment, and that showcased their effort to protect everything they stand for as mothers and women.

In her novel, Harriet insisted on showing that black slaves were women and mothers too, and that they valued much of the same things as any white woman would.

After repeated rejections, Harriet decided to publish the book herself, an impressive feat for any woman of that era, let alone one that had spent years as a fugitive slave.

Though Incidents is an autobiography, it reads like a novel, with a narrator named Linda Brent. But Jacobs wanted to make sure that readers understood that the book was wholly based on her own experiences. In the Preface to the book she wrote:

“Reader, be assured this narrative is no fiction. I am aware that some of my adventures may seem incredible; but they are, nevertheless, strictly true. I have not exaggerated the wrongs inflicted by Slavery; on the contrary, my descriptions fall far short of the facts. I have concealed the names of places, and given persons fictitious names. I had no motive for secrecy on my own account, but I deemed it kind and considerate towards others to pursue this course …”

Lydia Maria Child, the well-known author and social reformer, donated her services as an editor and vouched for the narrative’s veracity.

When the book was finally published in 1861, Jacobs’ account of the years of sexual abuse she faced by her owner shocked the American public. This was the first time any slave had ever documented that they were raped by their white owners. In the Preface she wrote:

“I want to add my testimony to that of abler pens to convince the people of the Free States what Slavery really is. Only by experience can any one realize how deep and dark, and foul is that pit of abominations. May the blessing of God rest on this imperfect effort in behalf of my persecuted people!”

Although it initially received favorable reviews, it was quickly forgotten once the Civil War started. After it ended, readers were confused as to who the actual author was due to the fact that Harriet published the novel using a pseudonym. This resulted in many people assuming it was fictitious.

The identity of the true author wasn’t revealed until nearly a century later, when Jean Fagan Yellin would re-publish her edition of the book in 1987.

. . . . . . . . . .

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

Later years

Through the years during the Civil War, Harriet lived in Washington D.C., where she assisted contrabands (refugee slaves), nursed black troops back to health, and taught freedmen how to read and write with her daughter Louisa. She helped organize, feed, and shelter refugees from slavery while trying to recruit more relief workers.

Harriet went on to set up schools run by the community, which eventually led to one being named in her honor as “The Jacobs Free School.” She also contributed to organizing African American communities, building churches, hospitals, and homes for newly freed people.

Harriet became less active in her later years but continued to support her daughter in the fight for African American education. She died in 1897 in Washington, D.C., where she was buried next to her brother.

More about Harriet A. Jacobs on this site

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: An Introduction

Biographies

Harriet Jacobs: A Life by Jean Fagan Yellin

More Information

Wikipedia

Harriet Jacobs

NB Historical Society

Reader discussion of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl on Goodreads

Harriet Ann Jacobs: The First Silence Breaker

Read and Listen

Harriet Jacobs on Project Gutenberg

Harriet Jacobs on LibriVox

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Harriet Ann Jacobs appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 11, 2019

Quotes from Persuasion by Jane Austen

Persuasion (1817) is the last novel that beloved British author Jane Austen completed. It was published six months after her death. It may well be Austen’s most romantic story, and yet, as with her other works, it’s far from frivolous, exploring themes of lost love, missed opportunity, heartbreak, and becoming one’s own person.

Anne Elliot, who is twenty-seven when the story begins, is a member of a family who suffers the indignity of having to lower their status as a way to get out of debt. At twenty-seven, a woman of that time would have been considered far from the bloom of youth.

As a result of the Elliots having to rent out their home, Anne re-encounters a Navy captain, Frederick Wentworth, to whom she was engaged some years before. Their reconnection is central to a plot filled with pathos, humor, social satire, and many touching scenes. Here is a sampling of quotes from Persuasion, a touching and engaging novel by the beloved Jane Austen:

. . . . . . . . . .

“I hate to hear you talk about all women as if they were fine ladies instead of rational creatures. None of us want to be in calm waters all our lives.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I do not think I ever opened a book in my life which had not something to say upon woman’s inconstancy. Songs and proverbs, all talk of woman’s fickleness. But perhaps you will say, these were all written by men.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Perhaps I shall. Yes, yes, if you please, no reference to examples in books. Men have had every advantage of us in telling their own story. Education has been theirs in so much higher a degree; the pen has been in their hands. I will not allow books to prove anything.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Dare not say that man forgets sooner than woman, that his love has an earlier death.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Memorable Jane Austen Quotes from Her Novels and Letters

. . . . . . . . . .

“There could have never been two hearts so open, no tastes so similar, no feelings so in unison, no countenances so beloved. Now they were as strangers; nay, worse than strangers, for they could never become acquainted. It was a perpetual estrangement.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Thus much indeed he was obliged to acknowledge – that he had been constant unconsciously, nay unintentionally; that he had meant to forget her, and believed it to be done. He had imagined himself indifferent, when he had only been angry; and he had been unjust to her merits, because he had been a sufferer from them.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Nor could she help feeling, on more serious reflection, that, like many other great moralists and preachers, she had been eloquent on a point in which her own conduct would ill bear examination.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If there is any thing disagreeable going on, men are always sure to get out of it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“How quick come the reasons for approving what we like.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“All the privilege I claim for my own sex (it is not a very enviable one: you need not covet it), is that of loving longest, when existence or when hope is gone!”

. . . . . . . . . .

“One man’s ways may be as good as another’s, but we all like our own best.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I can listen no longer in silence. I must speak to you by such means as are within my reach. You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope. Tell me not that I am too late, that such precious feelings are gone for ever. I offer myself to you again with a heart even more your own than when you almost broke it, eight years and a half ago.”

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like:

Quotes from Mansfield Park, Jane Austen’s Most Controversial Novel

. . . . . . . . . .

“Let us never underestimate the power of a well-written letter.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The last few hours were certainly very painful,” replied Anne: “but when pain is over, the remembrance of it often becomes a pleasure. One does not love a place the less for having suffered in it, unless it has been all suffering, nothing but suffering.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She hoped to be wise and reasonable in time; but alas! Alas! She must confess to herself that she was not wise yet.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I do think that men can forget a lost love quickly. I know that women would find it much harder.”

. . . . . . . . . .

[image error]

Persuasion by Jane Austen on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

“When any two young people take it into their heads to marry, they are pretty sure by perseverance to carry their point, be they ever so poor, or ever so imprudent, or ever so little likely to be necessary to each other’s ultimate comfort.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I will not allow books to prove any thing.”

“But how shall we prove any thing?”

“We never shall.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If I was wrong in yielding to persuasion once, remember that it was to persuasion exerted on the side of safety, not of risk.”

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from Persuasion by Jane Austen appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Gabriela Mistral

Born in Vicuña, Chile and raised in the small Andean village of Montegrande, her family was rather poor. Her father, Juan Gerónimo Godoy Villanueva, abandoned the family less than three years after she was born. Though he abandoned them and left her mother to support the family, he did pass down his gift for teaching.

At nine years old, Mistral attended a primary school that was taught by her older sister, Emelina Molina, but only attended for three years. By fifteen years old she was taking on the responsibility of supporting herself and her sick mother, Petronila Alcayaga, as a teacher’s aide.

She started writing poetry during her time as an educator, which is when she started using her pen pal name, Gabriela Mistral. Some of these were published in local and national magazines and newspapers years later.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Poetry as a way to heal

At seventeen years old, Mistral met a young railway worker named Romeo Ureta and fell in love. Sadly, in 1909 he committed suicide. The only thing found in his possession was a postcard from Mistral. This horrific moment is one that would scar her for the rest of her life. There was more tragedy to come when a nephew also committed suicide. Soon after, Mistral started writing poetry that characterized her painful emotions.

The sad death of her lover influenced her to write “Sonetos de la muerte,” three of which would go on to get published and earn her a national prize for poetry in 1914.

Teaching career and recognition

After she established a poetic reputation and received her diploma in 1912, Mistral was allowed to teach secondary school and got a teaching position near Santiago. Eventually, In 1918 she became head of a secondary school for girls in Punta Arenas, which later became the inspiration for a series of poems named Paisajes de Patagonia (Patagonian Landscapes).

Growing up around poverty, she was sympathetic to the poor and was eager to help when it came to education. In 1922, she gladly accepted Jose Vasconcelos’, the Mexican minister of education, invitation to create educational programs for the poor in Mexico. As a result, she brought mobile libraries into rural areas to make literature accessible to more people. She rarely ever took a break as she went right into editing her book, Readings for Women, and traveling to other countries to study their teaching methods.

All of her hard work rightfully earned her the title “Teacher of the Nation” in 1923 by her own government.

. . . . . . . . . .

Gabriela Mistral page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

Rise to fame and the Nobel Prize

As Mistral was rising to fame, she was asked to attend numerous conferences and give speeches. She eventually became Chile’s representative abroad for almost twenty years, which included the League of Nations, the United Nations, and more. After much traveling, Mistral decided she would settle down so she became a college professor. She taught classes at Middlebury and Barnard colleges and the University of Puerto Rico.

She became an icon for the Latin community in 1945 when she won the Nobel Prize for Literature on behalf of Latin America, making her the first Latina to do so. A year later, the United Nations turned to her in 1946 asking her to create the first worldwide appeal for funds for poor children, which is when UNICEF came to be.

Themes

Much of Mistral’s poems are written with intense emotion and direct language influenced by the modernist movement. Reoccurring themes include love, deceit, sorrow, nature, travel, and love for children as she uses her writing to tell her readers how she felt during certain points in her life.

All of these emotions create a constant internal battle that she can only express it through poetry. Her lyrical voices represent various aspects of her own personality that readers can interpret as autobiographical voices of a woman who has been hurt and betrayed numerous times.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Awards and Honors

In 1914, Mistral won a national prize in poetry for Sonetos de la muerte. She was inspired to create this collection of poems as a reflection of her deep sadness after her first lover committed suicide.

In 1923, Mistral was awarded the title “Teacher of the Nation” by her own government after studying different methods of teaching all over the world. She also assisted in educating the poor by providing them with books through mobile libraries.

In 1945, Mistral was the first Latinx writer to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, which she accepted on behalf of Latin America.

Unfortunately, in 1957 Mistral died at age sixty-seven in Hempstead, New York. Her body was laid to rest back in the small Andean village of Montegrande. Today, her poetry is translated into other foreign languages and is talked about internationally.

Major works

Sonetos de la muerte (“Sonnets of Death”) – 1914

Desolación (“Despair”), including “Decalogo del artista” – 1922

Lecturas para Mujeres (“Readings for Women”) – 1923

Ternura: canciones de niños – 1924

Nubes Blancas y Breve Descripción de Chile – 1934

Tala (“Harvesting”) -1938

1941: Antología: Selección de Gabriela Mistral – 1941

Los sonetos de la muerte y otros poemas elegíacos -1952

Lagar – 1954

Recados: Contando a Chile – 1957

Poesías completas – 1958

Poema de Chile (“Poem of Chile”) -1967

Lagar II – 1992

Biographies

Gabriela Mistral’s Struggle with God and Man by Martin C. Taylor (2012)

Queer Mother for the Nation by Licia Fiol – Matta (2002)

More Information

Wikipedia

Gabriela Mistral Foundation

The Famous People

Distinguished Women

Discussion of Gabriela Mistral’s works on Goodreads

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Gabriela Mistral appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 6, 2019

Shirley Jackson

Shirley Jackson (December 14, 1916 – August 8, 1965) was an American author whose works influenced a generation of genre writers who came after her. Two areas of writing put her on the literary map — wryly humorous accounts of family life, and disturbing tales of psychological terror. It might come as no surprise to those who have read her work that Jackson was fascinated with witchcraft and Satanism while growing up.

Jackson’s stories and novels have disturbed and fascinated readers and critics alike with their unabashed exploration of the dark side of human nature. Yet, there’s a sense that she hasn’t received her due — In A Jury of Her Peers, Elaine Showalter wrote, “One of the most sophisticated crafters of fiction … with work compared during her lifetime to Poe and James, she has long been neglected by most critics of American literature.”

Portrayals of family life were for effect

Shirley Jackson’s cheerful if messy portrayals of family life in a rambling Vermont home painted a false portrait. As she settled into middle age, she became morbidly obese, addicted to alcohol and tranquilizers, and so agoraphobic that she rarely left her house.

Predating that decline was her 1940 marriage to Stanley Edgar Hyman, a literary critic and professor. Hyman was chronically unfaithful, controlling, and belittling. They met when Jackson was an undergraduate at Syracuse University. A story she wrote about suicide caught his attention, and the relationship grew from there. Both of their families disapproved of their marrying, but softened up once grandchildren came along.

The couple had four children, whose antics were prettied up in her memoirs. She famously used her children as inspiration — not always flattering — in her fiction and nonfiction. Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons were early “momoirs” that inspired the likes of Jean Kerr and Erma Bombeck. The Hyman-Jackson family life wasn’t quite as fun as the glossy, funny portraits she painted in her pages.

Hyman was a respected figure in the literary community, even as he was widely considered arrogant and combative. With his wife, he was nothing short of a tyrannical bully, going so far as putting her on a strict writing schedule. In some ways, though, she benefitted from the rigor he enforced and his literary connections. He even bought a dishwasher with her royalties so she’d have more time to write!

. . . . . . . . . .

““The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson

. . . . . . . . . .

The Lottery

Jackson’s short story “The Lottery” catapulted her to fame in 1948, and it seemed to happen in a flash. She wrote it only three weeks before its publication in the The New Yorker, “on a bright summer morning as I was pushing my daughter up the hill in her stroller.”

“The Lottery” is the story of a fictional small town that hosts a ghastly annual stoning ritual. Elaine Showalter describes it in A Jury of Her Peers:

“Set in a small New England town like North Bennington [where the Jackson-Hyman family lived], ‘The Lottery’ is about ritual sacrifice and scapegoating. One person in the community is selected by lot each summer to be publicly stoned to death. Jackson made readers uncomfortable not only through the matter-of-fact violence of the story — even the victim’s little son has his pebbles ready — but also through implicitly questioning American innocence after the war: Would we too be ‘good Germans,’ going along with atrocity?”

The story earned rave reviews from editors and critics though readers weren’t as pleased. Quickly becoming the most controversial story ever published by The New Yorker, readers not only canceled subscriptions but sent hate mail to the author via the magazine. “Millions of people, and my mother had taken a pronounced dislike to me,” Jackson claimed.

Still, “The Lottery” soon became a staple in high school English curricula and is one of the most anthologized short stories of twentieth-century American literature. The Lottery and Other Stories was Jackson’s first collection, published in 1949.

. . . . . . . . .

Shirley Jackson page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . .

The ups and downs of the writing life

After “The Lottery” put her on the literary map, her output continued at a fast clip. That same year, 1948, saw the publication of her first novel, The Road Through the Wall. In all, there would be six novels, four children’s books, the two memoirs, and dozens of short stories — all throughout the years of raising her family.

According to Elaine Showalter, “Jackson’s novels of the 1950s were all in the genre of female gothic, and dealt with themes of matrophobia, madness, lesbianism, and murderous rage.” Ushering the decade were Hangsaman (1951), the story of Natalie, a suicidal college student with psychic powers. The Haunting of Hill House (1959) is one of Jackson’s best-known works, part ghost story, part psychological thriller.

Many critics consider We Have Always Lived in the Castle to be Jackson’s finest work. To quote Showalter once again: “Long overlooked, the novel has been rediscovered in the twenty-first century by writers including Stephen King and Jonathan Lethem, and by feminist critics who read it as a perfectly constructed and haunting example of the female gothic.”

The following observations by Jackson on the writing life is from the 1968 collection Come Along with Me:

“One of the most terrifying aspects of publishing stories and books is the realization that they are going to be read, and read by strangers. I had never fully realized this before, although I had of course in my imagination dwelt lovingly upon the thought of the millions and millions of people who were going to be uplifted and enriched and delighted by the stories I wrote.

It had simply never occurred to me that these the millions and millions of people might be so far from being uplifted that they would sit down and write me letters I was downright scared to open; of the three-hundred-odd letters that I received that summer I can count only thirteen that spoke kindly to me, and they were mostly from friends.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Quotes by Shirley Jackson on Writing and Life

. . . . . . . . . . .

Accolades and adaptations

Jackson’s novel, We Have Always Lived in the Castle was made one of Time Magazine’s “Ten Best Novels” in 1961. She consistently intrigued readers with her thrilling tales. Many of her works have been adapted to film, theater, and television.

As a master of literary creepiness, Jackson has been cited as a major influence on Stephen King, as mentioned earlier, as well as Neil Gaiman, Joanne Harris, and others. The Shirley Jackson Awards were launched in 2007, recognizing the contributions, and

In 2007, the Shirley Jackson Awards were established with the blessing of the Jackson estate. They recognize her legacy in literature, and in turn, give awards in the genres of horror and psychological suspense. North Bennington, Vermont, the town where the Jackson-Hyman family lived, celebrates Shirley Jackson Day on June 27, the date when the story “The Lottery” takes place.

Jackson was a heavy smoker, overweight, and, due to extreme anxiety, possibly addicted to unsafe prescription barbiturates. She also took amphetamines for weight loss, leading to a cycle of drug abuse. By the end of her life she was extremely agoraphobic, rarely leaving her house. She was only 48 when she died of heart failure in her sleep in 1965.

More about Shirley Jackson on this site

Shirley Jackson on Motherhood, Experience, and Fiction Writing

Quotes by Shirley Jackson on Writing and Life

Major works

In addition to these book-length works, Jackson wrote scores of short stories. Find her complete bibliography here.

The Road Through the Wall (1948)

The Lottery and Other Stories (1949)

Hangsaman (1951)

The Haunting of Hill House (1959)

We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962)

Come Along With Me (1968)

Just an Ordinary Day: Uncollected Stories (1995)

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings (2015)

Children’s Books

The Witchcraft of Salem Village (1956)

The Bad Children: A Play in One Act for Bad Children (1959)

Nine Magic Wishes (1963)

Famous Sally (1966)

Autobiographies and Biographies

Life Among the Savages (1953)

Raising Demons (1957)

Private Demons: The Life of Shirley Jackson by Judy Oppenheimer

More Information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Shirley Jackson’s work on Goodreads

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Shirley Jackson appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 4, 2019

Quotes from Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen

Northanger Abbey was actually the first novel that Jane Austen completed with the hopes of publication, in 1803. It was first titled Susan and she sold the copyright to a London publisher for a pittance. The publisher held on to it without going to print. It was tied up until 1816 when Jane’s brother Henry managed to buy it back.

Jane spent some time revising the original, renaming her heroine Catherine, but by the time it was published in 1817, she died. That year, another of her novels, Persuasion, was published as well. Northanger Abbey is considered a coming-of-age novel in which Catherine Morland, the young and rather naïve heroine, learns the ways of the world.

In this, as she does in her other novels, Jane Austen critiques young women who put too much stock in appearances, wealth, and social acceptance through the character of Catherine, who values happiness but not at the cost of compromising one’s values and morals.

Set in Bath, England, the fashionable resort city where the Austens lived for a time, Northanger Abbey has been called “the most joyous of Jane Austen’s novels and is an early work conceived as a pastiche of the melodramatic excesses of the Gothic novel … the result makes the social and romantic trials of Catherine Morland a delight to follow.”

The following quotes reflect the fun Jane Austen had with her characters, though as always, it’s not just frivolous. She manages to imbue insightful commentary into every delightful line of text and dialog.

. . . . . . . . . .

“There is nothing I would not do for those who are really my friends. I have no notion of loving people by halves, it is not my nature.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A mother would have been always present. A mother would have been a constant friend; her influence would have been beyond all other. ”

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy:

Memorable Jane Austen Quotes from Her Novels and Letters

. . . . . . . . . .

“It is only a novel … or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If adventures will not befall a young lady in her own village, she must seek them abroad.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Everybody allows that the talent of writing agreeable letters is peculiarly female. Nature may have done something, but I am sure it must be essentially assisted by the practice of keeping a journal.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“No man is offended by another man’s admiration of the woman he loves; it is the woman only who can make it a torment.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I assure you. I have no notion of treating men with such respect. That is the way to spoil them.”

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: Quotes from Emma by Jane Austen

. . . . . . . . . .

“You think me foolish to call instruction a torment, but if you had been as much used as myself to hear poor little children first learning their letters and then learning to spell, if you had ever seen how stupid they can be for a whole morning together, and how tired my poor mother is at the end of it, as I am in the habit of seeing almost every day of my life at home, you would allow that to torment and to instruct might sometimes be used as synonymous words.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“To come with a well-informed mind is to come with an inability of administering to the vanity of others, which a sensible person would always wish to avoid. A woman especially, if she have the misfortune of knowing anything, should conceal it as well as she can.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It requires uncommon steadiness of reason to resist the attraction of being called the most charming girl in the world.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“To look almost pretty is an acquisition of higher delight to a girl who has been looking plain the first fifteen years of her life than a beauty from her cradle can ever receive.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Friendship is certainly the finest balm for the pangs of disappointed love.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“What one means one day, you know, one may not mean the next. Circumstances change, opinions alter.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If I could not be persuaded into doing what I thought wrong, I will never be tricked into it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The advantages of natural folly in a beautiful girl have been already set forth by the capital pen of a sister author; and to her treatment of the subject I will only add, in justice to men, that though to the larger and more trifling part of the sex, imbecility in females is a great enhancement of their personal charms, there is a portion of them too reasonable and too well informed themselves to desire anything more in woman than ignorance.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

“Catherine hoped at least to pass uncensured through the crowd. As for admiration, it was always very welcome when it came, but she did not depend on it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“You men have none of you any hearts.”

‘If we have not hearts, we have eyes; and they give us torment enough.”

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 31, 2019

Quotes from Mansfield Park, Jane Austen’s Most Controversial Novel

Mansfield Park by Jane Austen (1814) is the third published novel by the esteemed British author. It’s the story of Fanny Price, who is sent by her impoverished family to be raised in the household of a wealthy aunt and uncle. The narrative follows her into adulthood and comments on class, family ties, marriage, the status of women, and even British colonialism.

The novel went through two editions before Austen’s death in 1817, but didn’t receive any public reviews until 1821. Critical reception for this novel, from that time forward, has been the most mixed among Austen’s works, and it’s considered her most controversial.

In an introduction to a contemporary edition, Kathryn Sutherland portrays Mansfield Park as a darker work than Austen’s other novels, because it challenges “the very values (of tradition, stability, retirement and faithfulness) it appears to endorse.” Here are some quotes by Jane Austen that illuminate Mansfield Park, a novel very much worth savoring:

. . . . . . . . . .

“Good-humoured, unaffected girls, will not do for a man who has been used to sensible women. They are two distinct orders of being.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I am very strong. Nothing ever fatigues me, but doing what I do not like.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Give a girl an education, and introduce her properly into the world, and ten to one but she has the means of settling well, without farther expense to anybody.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There will be little rubs and disappointments everywhere, and we are all apt to expect too much; but then, if one scheme of happiness fails, human nature turns to another; if the first calculation is wrong, we make a second better: we find comfort somewhere.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Family squabbling is the greatest evil of all.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Memorable Jane Austen Quotes From Her Novels and Letters

. . . . . . . . . .

“Selfishness must always be forgiven you know, because there is no hope of a cure.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“You have qualities which I had not before supposed to exist in such a degree in any human creature. You have some touches of the angel in you beyond what—not merely beyond what one sees, because one never sees anything like it—but beyond what one fancies might be.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“We have all a better guide in ourselves, if we would attend to it, than any other person can be.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Here’s harmony!” said she; “here’s repose! Here’s what may leave all painting and all music behind, and what poetry only can attempt to describe! Here’s what may tranquilize every care, and lift the heart to rapture! When I look out on such a night as this, I feel as if there could be neither wickedness nor sorrow in the world; and there certainly would be less of both if the sublimity of Nature were more attended to, and people were carried more out of themselves by contemplating such a scene.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“To know him in bits and scraps is common enough; to know him pretty thoroughly is, perhaps, not uncommon; but to read him well aloud is no everyday talent.”

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like:

10 Memorable Quotes from Pride and Prejudice

. . . . . . . . . .

“Selfishness must always be forgiven you know, because there is no hope of a cure.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“… He recommended the books which charmed her leisure hours, he encouraged her taste, and corrected her judgment; he made reading useful by talking to her of what she read, and heightened its attraction by judicious praise.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Life seems but a quick succession of busy nothings.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Oh! Do not attack me with your watch. A watch is always too fast or too slow. I cannot be dictated to by a watch.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Of course I love her, but there are as many forms of love as there are moments in time.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Let us have the luxury of silence.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I cannot think well of a man who sports with any woman’s feelings; and there may often be a great deal more suffered than a stander-by can judge of.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I am worn out with civility. I have been talking incessantly all night with nothing to say.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If any one faculty of our nature may be called more wonderful than the rest, I do think it is memory … The memory is sometimes so retentive, so serviceable, so obedient; at others, so bewildered and so weak; and at others again, so tyrannic, so beyond control! We are, to be sure, a miracle every way; but our powers of recollecting and of forgetting do seem peculiarly past finding out.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Mansfield Park by Jane Austen on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

“Human nature needs more lessons than a weekly sermon can convey.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She was not often invited to join in the conversation of the others, nor did she desire it. Her own thoughts and reflections were habitually her best companions.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She was of course only too good for him. But as nobody minds having what is too good for them, he was very steadily earnest in the pursuit of the blessing.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“So long divided and so differently situated, the ties of blood were little more than nothing.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A fondness for reading, properly directed, must be an education in itself.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A large income is the best recipe for happiness I ever heard of.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There is nothing like employment, active indispensable employment, for relieving sorrow.”

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from Mansfield Park, Jane Austen’s Most Controversial Novel appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 29, 2019

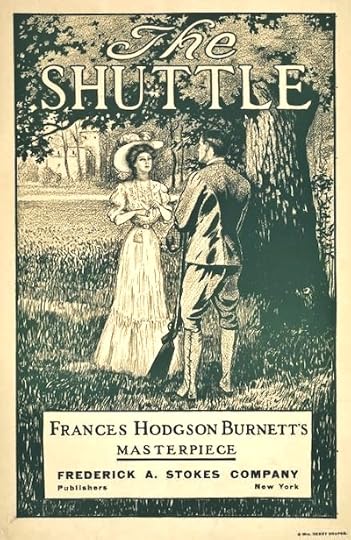

Lady of the Manor: Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Shuttle (1907)

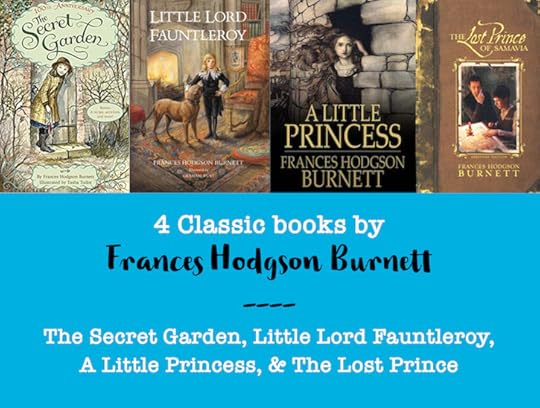

When The Shuttle by Frances Hodgson Burnett was published in 1907, she was already the successful author of Little Lord Fauntleroy, The Making of a Marchioness, A Little Princess, and some two dozen other books for children and adults. In the course of her career, she produced some fifty novels. Of these, few but the children’s classics just mentioned, plus A Secret Garden, published in 1911, are still widely read.

In 2007 Persephone books republished The Shuttle, an entertaining story of American heiresses who marry English aristocrats. From the Persephone catalog:

“The Shuttle, which is five hundred pages long and a page-turner for every one of them, is about far more than the process by which an English country house can be brought back to life with the injection of transatlantic money (there is some particularly interesting detail about the new life breathed into the garden) …

Above all it is about Bettina Vanderpoel. She is the reason why this is such a successful, entertaining and interesting novel – one could almost say that she is one of the great heroines, on a par with Elizabeth Bennett, Becky Sharp, and Isabel Archer.

This is because she is so intelligent and so enterprising – she has the normal feminine qualities but a strong business sense, inherited from her father, and instinctive management skills (as we would now call them).” Read the rest of the synopsis and history of The Shuttle at Persephone Books.

. . . . . . . . . .

The following excerpt is excerpted and adapted from “Lady of the Manor” by Angelica Shirley Carpenter, chapter seven of the book In the Garden: Essays in Honor of Frances Hodgson Burnett, edited by Angelica Shirley Carpenter, published by The Scarecrow Press, Inc. © 2006.

In 1898 Frances Hodgson Burnett leased a country house in Kent. “It is a charming place,” she wrote to her son Vivian, who was a senior at Harvard, “with a nicely timbered park and a beautiful old walled kitchen garden.”

At Maytham Hall Frances got her first chance to live a lifestyle she had long idealized, as lady of the manor, and her first opportunity to create a garden of her own. Her experiences at Maytham, good and bad, inspired several books.

When she came to Maytham, the famous author was forty-eight years old and newly divorced. Her rouge and her dyed hair, described as hennaed or golden, were shocking for the time, as was her habit of smoking cigarettes, but her blue eyes and animated manner of talking were considered attractive.

Frances was accompanied by Stephen Townesend, a handsome British doctor ten years her junior. Frances and Stephen had lived together on and off for a decade, as he gave up medicine to become her business manager and partner for many projects.

“Uncle Stephen takes care of my business,” Frances had written to Vivian in 1891, “. . . but as for the rest, I feel as if I was the one who had to take care of him. He is so delicate and nervous and irritable, poor boy.”

Frances recalled her arrival in Kent in The Shuttle, a novel begun at Maytham in 1900. In this book a young American bride travels by carriage from the train station to her husband’s country home in England:

“Sometimes she saw the sweet wooded, rolling lands made lovelier by the homely farmhouses and cottages enclosed and sheltered by thick hedges and trees; once or twice they drove past a park enfolding a great house guarded by its huge sentinel oaks and beeches; once the carriage passed through an adorable little village, where children played on the green and a square-towered grey church seemed to watch over the steep-roofed cottages and creeper-covered vicarage.”

. . . . . . . . . .

In the Garden: Essays in Honor of Frances Hodgson Burnett on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

“The house is excellent — “ Frances wrote to Vivian, “paneled, square hall, library, billiard room, morning room, stables, two entrance lodges, and a square tower on the roof, from which we can see the English Channel.”

In The Shuttle, Frances described how Maytham’s walled garden looked when she arrived, in the spring: “Paths and beds were alike overgrown with weeds, but some strong, early-blooming things were fighting for life, refusing to be strangled.

Against the beautiful old red walls, over which age had stolen with a wonderful grey bloom, venerable fruit trees were spread and nailed, and here and there showed their bloom.”

Frances had the garden cleared and then planted. Though she employed gardeners, she enjoyed doing some of the work herself. “The calm here is good for me,” she wrote to Vivian at summer’s end. As winter approached, she studied seed catalogues.

In her second spring at Maytham she planted roses to grow up walls and tree trunks. In The Secret Garden, we see her vision realized as Mary first enters the garden:

“There were . . . trees in the garden, and one of the things which made the place look strangest and loveliest was that climbing roses had run all over them and swung down long tendrils which made light swaying curtains, and here and there they had caught at each other or at a far-reaching branch and had crept from one tree to another and made lovely bridges of themselves.”

But Frances’ delight in country life was overshadowed by her growing unhappiness. “Stephen was proving exceedingly hard to handle,” Vivian wrote later. “He was taking a position with regard to their association that had in it a suggestion of domineering ownership she did not understand. It frightened her.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The title The Shuttle refers to steamships that sail back and forth across the Atlantic, weaving American and British cultures together. The novel tells of an unhappy marriage between a rich, innocent American girl and a nasty, older, impoverished British lord.

Though Frances was older than Stephen and hardly innocent, the book offers many insights into their relationship.

The book begins in New York, where Sir Nigel behaves himself just long enough to win the hand of young Rosalie Vanderpoel. As their ship steams away from the dock, he reveals his true colors. “‘What a deuce of a row Americans make,’ he said. “It will be a positive rest to be in a country where the women do not cackle and shriek with laughter.'”

Rosalie soon realizes that her marriage is a mistake. “Her self-reproach was as great as her terror,” Frances wrote.

The Shuttle describes “a manor house reigning over an old English village.” Rosalie helps the poor villagers, who are her husband’s tenants. “I suppose it gratifies your vanity to play the Lady Bountiful,” sneers Sir Nigel, but Rosalie’s good deeds console her, and in real life, Frances took pride in the same work. She held fêtes for the children and visited poor families, offering help.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: 4 Classic Books by Frances Hodgson Burnett

. . . . . . . . . .

Like Sir Nigel, Stephen was moody and demanding. He behaved better in the presence of company and Frances’ house parties became famous. Her guests took tea on the lawn, strolled under parasols through the gardens, sang and danced, dressed in fancy costumes, played cards and other games, and took afternoon rides in the Victoria.

In 1900 Frances married Stephen, making headlines on both sides of the Atlantic. Soon she wrote to her sister Edith that Stephen “scarcely seems sane half the time. . . . He will work up scenes. He will not let things alone.”

“You will do as I order you,” Sir Nigel tells Rosalie in The Shuttle, “and learn to behave yourself as a decent married woman should. You will learn to obey your husband and respect his wishes and control your devilish American temper.”

Frances wrote to Edith about Stephen: “He talks about my ‘duties as a wife’ as if I had married him of my own accord — as if I had not been forced and blackguarded and blackmailed into it. It is my duty to end my acquaintance with all such people as he suspects of not admiring him … It is my duty to make my property over to him … It is my duty to work very hard and above all to love him very much and insist on his writing plays with me.”

In The Shuttle Frances described a husband’s blackmail. Sir Nigel knows that women are “trained to give in to anything rather than be bullied in public, to accede in the end to any demand rather than endure the shame of a certain kind of scene made before servants, and a certain kind of insolence used to relatives and guests.” Stephen used the same techniques, raving in front of her butler and making scenes before her maid.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Shuttle by Frances Hodgson Burnett on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

All the classic signs of abuse, not so well known in Frances’ lifetime, are catalogued in The Shuttle. Sir Nigel isolates Rosalie from her family and friends, refusing to let her parents see her when they travel to England. Stephen tried to do this with Frances, too.

In The Shuttle, after twelve terrible years, Rosalie’s younger sister comes from America to England to rescue her. It must have satisfied Frances to show the courageous Betty standing up to her villainous brother-in-law. “All your life,” she tells him, “you have counted upon getting your own way because you saw that people–especially women–have a horror of public scenes, and will submit to almost anything to avoid them …

That is true very often, but not always … I, for instance, would let you make a scene with me anywhere you chose–in Bond Street–in Piccadilly–on the steps of Buckingham Palace … and you would gain nothing you wanted by it—nothing.”

“Damn her!” Sir Nigel cries out later. “If I had hung her up and cut her into strips she would have died staring at me with her big eyes–without uttering a sound” In the book’s climax, Betty hides in a hedge as he hunts her, to rape her or kill her or both. Frances lets the reader imagine his exact plan.

In 1902, Frances fled to New York, checking herself into a sanitarium. Stephen soon followed, but in this refuge Frances finally found the courage to tell him that the marriage was over. Probably she paid him off.

With Stephen gone, Frances returned to Kent. Elegantly attired in white gowns and hats, she spent summers writing in her rose garden. The only disturbance came from a robin. It perched on her hat, she said, and took crumbs from her hand.

Frances had to leave Maytham in 1908 when her landlord put it up for sale. She could not afford to buy it, but she soon built a home of her own, at Plandome, on Long Island. The Shuttle, that painful and most difficult novel, paid for the whole place. The New York house had a wonderful garden, but nothing would ever compare to her rose garden at Maytham. So she recreated it for herself and her readers in The Secret Garden.

Sources for this essay may be found in the book, In the Garden: Essays in Honor of Frances Hodgson Burnett, edited by Angelica Shirley Carpenter.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy

Born Criminal: Matilda Joslyn Gage, Radical Suffragist by Angelica Shirley Carpenter

. . . . . . . . . .

Angelica Shirley Carpenter has master’s degrees from the University of Illinois in education and library science. Curator emerita of the Arne Nixon Center for the Study of Children’s Literature at California State University, Fresno, she lives in Fresno.

She has published five previous books about authors: Frances Hodgson Burnett (two books), Robert Louis Stevenson, Lewis Carroll, and L. Frank Baum, who was Matilda’s son-in-law. A past president of the International Wizard of Oz Club, she is active in the Lewis Carroll Society of North America and the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. Find out more about her at angelicacarpenter.com.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Lady of the Manor: Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Shuttle (1907) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 28, 2019

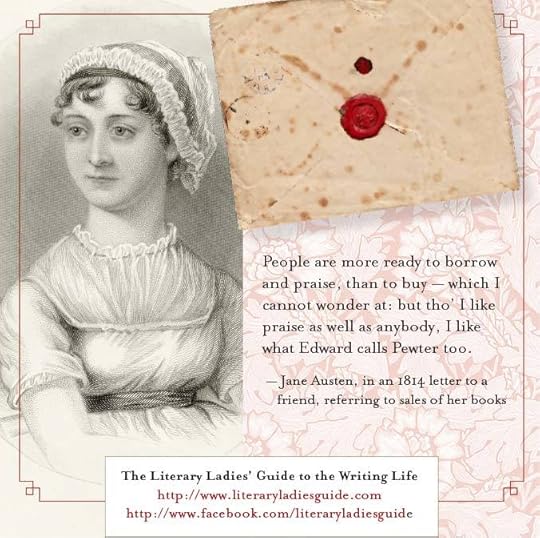

Memorable Jane Austen Quotes From Her Novels and Letters

Jane Austen (1775 – 1817), the beloved British author, was deeply invested in her craft as a wordsmith. Her talent was recognized early on and valued by her family.

Jane’s father, a country rector, and her brothers played key roles in getting her works published at a time when it was considered unseemly for women to put themselves forth in business.

She longed to see her work in print, regardless of whether or not it would gain her fame or fortune — but getting it published was important to her, contrary to the myth about her extreme modesty.

Many memorable quotes emerged from her six published books and surviving letters. Here are some of our favorite Jane Austen quotes.

. . . . . . . . . .

Sense and Sensibility (1811)

More quotes from Sense and Sensibility

“People always live forever when there is an annuity to be paid them.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Know your own happiness. You want nothing but patience— or give it a more fascinating name, call it hope.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It isn’t what we say or think that defines us, but what we do.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“The more I know of the world, the more I am convinced that I shall never see a man whom I can really love. I require so much!”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Know your own happiness. You want nothing but patience — or give it a more fascinating name, call it hope.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It is not time or opportunity that is to determine intimacy;—it is disposition alone. Seven years would be insufficient to make some people acquainted with each other, and seven days are more than enough for others.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I wish, as well as everybody else, to be perfectly happy; but, like everybody else, it must be in my own way.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Pride and Prejudice (1813)

More quotes from Pride and Prejudice

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading! How much sooner one tires of any thing than of a book! When I have a house of my own, I shall be miserable if I have not an excellent library.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A lady’s imagination is very rapid; it jumps from admiration to love, from love to matrimony in a moment.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There are few people whom I really love, and still fewer of whom I think well. The more I see of the world, the more am I dissatisfied with it; and every day confirms my belief of the inconsistency of all human characters, and of the little dependence that can be placed on the appearance of merit or sense.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I must learn to be content with being happier than I deserve.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Vanity and pride are different things, though the words are often used synonymously. A person may be proud without being vain. Pride relates more to our opinion of ourselves, vanity to what we would have others think of us.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“An unhappy alternative is before you, Elizabeth. From this day you must be a stranger to one of your parents. Your mother will never see you again if you do not marry Mr. Collins, and I will never see you again if you do.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I dearly love a laugh… I hope I never ridicule what is wise or good. Follies and nonsense, whims and inconsistencies do divert me, I own, and I laugh at them whenever I can.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Mansfield Park (1814)

“Good-humoured, unaffected girls, will not do for a man who has been used to sensible women. They are two distinct orders of being.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Nothing ever fatigues me, but doing what I do not like.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There will be little rubs and disappointments everywhere, and we are all apt to expect too much; but then, if one scheme of happiness fails, human nature turns to another; if the first calculation is wrong, we make a second better: we find comfort somewhere.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“We have all a better guide in ourselves, if we would attend to it, than any other person can be.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Selfishness must always be forgiven you know, because there is no hope of a cure.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Life seems but a quick succession of busy nothings.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Oh! Do not attack me with your watch. A watch is always too fast or too slow. I cannot be dictated to by a watch.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Emma (1815)

More quotes from Emma

“There is no charm equal to tenderness of heart,’ said she afterwards to herself. ‘There is nothing to be compared to it. Warmth and tenderness of heart, with an affectionate, open manner, will beat all the clearness of head in the world, for attraction: I am sure it will.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I always deserve the best treatment because I never put up with any other.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Why not seize the pleasure at once, how often is happiness destroyed by preparation, foolish preparations.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It is very difficult for the prosperous to be humble.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Seldom, very seldom, does complete truth belong to any human disclosure; seldom can it happen that something is not a little disguised or a little mistaken.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Were I to fall in love, indeed, it would be a different thing! but I have never been in love; it is not my way, or my nature; and I do not think I ever shall. And, without love, I am sure I should be a fool to change such a situation as mine.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Northanger Abbey (1817)

“There is nothing I would not do for those who are really my friends. I have no notion of loving people by halves, it is not my nature.”

“The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It is only a novel … or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“No man is offended by another man’s admiration of the woman he loves; it is the woman only who can make it a torment.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A woman, especially, if she have the misfortune of knowing anything, should conceal it as well as she can.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“To look almost pretty is an acquisition of higher delight to a girl who has been looking plain the first fifteen years of her life than a beauty from her cradle can ever receive.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Friendship is certainly the finest balm for the pangs of disappointed love.”

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like: Jane Austen’s Literary Ambitions

. . . . . . . . . .

From Jane Austen’s letters

“I do not want people to be agreeable, as it saves me the trouble of liking them.” (from a letter to her sister Cassandra, 1798)

. . . . . . . . . .

“An artist cannot do anything slovenly.” (From a letter to her sister Cassandra, 1798)

. . . . . . . . . .

“The pleasures of friendship, of unreserved conversation, of similarity and taste and opinions will make good amends for orange wine.” (From a letter to her sister Cassandra, 1808)

. . . . . . . . . .

“I begin already to weigh my words and sentences more than I did, and am looking about for a sentiment, an illustration or a metaphor in every corner of the room. Could my Ideas flow as fast as the rain in the Store closet it would be charming.” (from a letter to her sister Cassandra, 1809)

. . . . . . . . . .

“The work [Pride and Prejudice] is rather too light and bright and sparking; it wants shade; it wants to be stretched out here and there with a long chapter — of senses if it could be had; if not, of solemn specious nonsense — about something unconnected with the story… anything that would form a contrast, and bring the reader with increased delight to the playfulness and epigrammatism of the general style.” (From a letter to her sister Cassandra, 1813)

. . . . . . . . . .

“I must make use of this opportunity to thank you, dear Sir, for the very high praise you bestow on my other novels. I am too vain to wish to convince you that you have praised them beyond their merits. My greatest anxiety at present is that this fourth work should not disgrace what was good in the others.” (From a letter to a librarian, 1815)

. . . . . . . . . .

“I think I may boast myself to be, with all possible Vanity, the most unlearned, & uninformed Female who ever dared to be an Authoress.” (from a letter to James Stainer, 1815)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Wisdom is better than wit, and in the long run will certainly have the laugh on her side.” (From a letter to her niece, 1814)

. . . . . . . . . .

Jane Austen page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Memorable Jane Austen Quotes From Her Novels and Letters appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 26, 2019

Learning to See: A Novel of Dorothea Lange by Elise Hooper

Dorothea Lange‘s influential photography has been collected and displayed in museums and institutions everywhere, yet few know the story of how Dorothea Nutzhorn became Dorothea Lange, social justice activist and pioneering photojournalist. In Elise Hooper’s much anticipated second novel, Learning to See (William Morrow, 2019), Dorothea Lange and her legacy is reimagined in a riveting new light.

In 1918, a fearless 22-year-old arrives in San Francisco with nothing but a friend, her camera, and determination to make her own way as an independent woman. In no time, Dorothea goes from camera shop assistant to celebrated owner of the city’s most prestigious and stylish portrait studio.

At a time when women were supposed to keep the home fires burning, Dorothea was forging her own path and gaining popularity while doing it.

Shortly after finding her own success, she meets the talented but volatile painter, Maynard Dixon, and becomes his wife. Their early days are colored by their blissful Bohemian lifestyle and mutual artistic inspiration. But by the early 1930s their marriage mirrors the collapse of the American economy and Dorothea must find ways to support her two young sons single-handedly.

As her personal life implodes, she becomes more determined than ever to expose the horrific conditions of the nation’s poor. Taking to the road with her camera, Dorothea creates images that would go on to inspire, reform, and define the era.

Then, when the United States enters World War II, Dorothea chooses to confront the incarceration of thousands of innocent Japanese Americans.

Her ambition and refusal to turn away from the injustices of the world shape her entire catalogue of work, and Learning to See spans the decades of this tumultuous era of American History. Elise Hooper provides a gripping account of the unwavering woman behind the camera who risked everything for art, activism, and love, even when her choices came at a steep price. (— from the publisher)

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy:

A Conversation with Elise Hooper, Author of The Other Alcott

. . . . . . . . . .

Q: Why did you decide to write about Dorothea Lange?

A: After I finished writing The Other Alcott, I decided to be practical and find a new story set closer to home. I’d always found Oregon-born Imogen Cunningham’s abstracted flower photographs to be beautiful and wanted to learn more about her. During my research, I discovered that her best friend, Dorothea Lange, had also been a pioneering photographer, although the women had very different views on the purpose of art and photography.

When I learned Lange had photographed the internment of Japanese Americans and that these photos had been impounded due to their subversive points of view, I decided to shift my focus from Cunningham to her best friend, Lange.

In the Pacific Northwest where I live, the internment’s legacy is particularly relevant since many of Seattle’s residents were forced to leave their homes and businesses after FDR issued Executive Order 9066. I wanted to know more about this woman who dared to believe the government was making an unconscionable mistake at a time when some Americans actively participated in discrimination against Japanese Americans or looked the other way.

Midway through writing this novel, the political climate of the United States shifted with the results of the 2016 presidential election. Women took to the streets in January 2017 to express many grievances over the direction of the nation’s policies and values.

This energy and rising political consciousness made me believe Dorothea Lange was more relevant than ever since she was a woman who had experienced a political awakening in her late thirties and acted on it.

As a result of the worsening economic conditions in California and the breadlines threading down the sidewalk underneath her studio window in the 1930s, she became an activist for democratic values and social justice.

Though she sometimes denied any political angle to her art, she often spoke about her desire for her work to prompt conversations about labor, social class, race, and the environment. Her awakening as an activist breathed new life into this project for me and made me more excited than ever to tell her story.

. . . . . . . . .

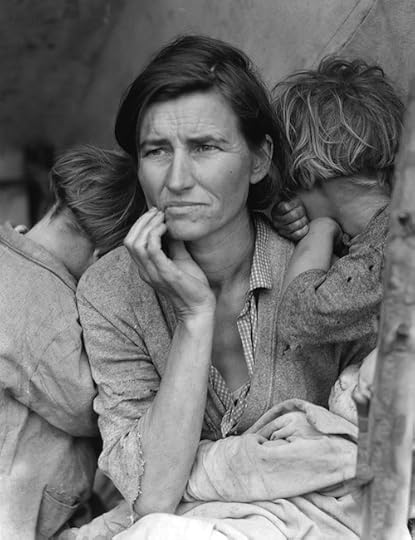

Migrant Mother (1936) is Dorothea Lange’s most iconic photograph

. . . . . . . . .

Q: It’s interesting that a woman who is best known for taking such poignant images of women and children had such a conflicted family life.

A: Dorothea’s complex and seemingly contradictory feelings about motherhood fascinated me. Her own father abandoned her family when she was twelve, and this left her with a powerful sense of rejection. So deep was her hurt that she rarely spoke of it to anyone. In fact, it wasn’t until after her death that Paul Taylor learned the truth of her father’s absence in her life.

Yet despite the anguish that her father’s abandonment caused her, she fostered her own sons out during the Great Depression, a choice for which her children never forgave her.

No one faulted Maynard and Paul for not attending to their children, but people questioned Dorothea’s choices and this criticism stung her. Her ambitions and talents put her at odds with many of the norms of the time when few women were the breadwinners in their families.

So, although she sometimes felt guilty and selfish, she persevered with work she believed was necessary and important. This tension between ambition and parental duty drew me into her story.

While I wrote this story, there were times when I struggled to make sense of Dorothea’s choices to foster her children out to strangers, especially after she married Paul Taylor, but I had to remember that in the early 1900s commonly accepted ideas about child-rearing and child development differed from today.

People tended to emphasize the resilience of children and overlook their emotional needs. In some ways Dorothea reminded me of another woman from the same era who is celebrated for her humanitarian work: Eleanor Roosevelt.

Like Lange, Roosevelt had a fraught relationship with her children stemming largely from her active political career outside the home. The fact is that women who chose to pursue careers in the early 1900s lacked role models, mentors, affordable childcare options, and other supports that are now widely accepted to be critical to balancing motherhood with work outside the home.

. . . . . . . . . .

Dorothea Lange in the 1930s

. . . . . . . . . .

Q: Given that Lange carried such psychic scars surrounding her own father’s abandonment, how did she justify her choices?

A: To be clear, there were some major differences between Dorothea’s father’s departure and her decision to entrust her boys to someone else’s care. She didn’t fully understand the causes for her father’s departure until years later when her mother provided more context.

He had fled his wife and children in 1907 because he was in trouble with the law as a result of some unsavory business practices. Dorothea’s mother hid it from her children, but she continued to meet with him in secret until they finalized their divorce on the grounds of abandonment in 1919.

Dorothea believed she was keeping her boys safe from a life of poverty that was unfolding around her on San Francisco’s streets and beyond. The 1930s represent an era of hard times that almost defies comprehension to us today. People were desperate to feed their families. Orphanages were packed with children whose mothers and fathers couldn’t support them.

Families disintegrated. It was a period of vulnerability and danger for many children. So, while Dan and John never forgave Dorothea for leaving them with strangers, she felt she was doing the best she could to keep them cared for and safe.

. . . . . . . . .

Learning to See by Elise Hooper is available on Amazon

and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . . .

Q: Why didn’t Maynard or Paul do more to help with the care of their children?

A: The expectations of the time were that women tended to children. It was that simple. Regardless of social class, it never appears to have entered into people’s consideration that men could have played a hands-on role with raising their sons and daughters.

And this trickled down to the children of this generation. Interviews with Dan Dixon when he was an adult reflect that his hurt feelings were aimed mostly at his mother. He never seemed to hold Maynard accountable in the same way that he blamed his mother for leaving him.

Q: What happened to Dorothea’s two closest friends?

A: Fronsie’s life is mostly fictionalized in this novel. After she helped to settle Dorothea in the photography studio on Sutter Street, she mostly disappears from Lange’s biographies with the exception of reappearing as a guest at Dorothea’s wedding to Maynard.

Based on a note by Paul Taylor in the transcript of Dorothea’s oral history with Suzanne Riess, it seems Fronsie ended up living in Los Angeles during the 1960s.

Imogen led a brilliant career as a photographer and lived until 1976, when she died at ninety-three years of age. She produced many books and mentored other photographers, and her work has been exhibited around the world.

. . . . . . . . .

Japanese children pledging allegiance at an internment camp, 1942

. . . . . . . . . .

Q: What happened to Dorothea Lange’s impounded photos of the Japanese American internment?

A: The army impounded the images until after the war and then they were quietly placed in the National Archives. In 1972, Richard Conrat, one of Lange’s assistants, published some of them when he produced Executive Order 9066 for the UCLA Asian American Studies Center. It wasn’t until 2006 when Linda Gordon and Gary Y. Okihiro published their book Impounded that the photos received widespread attention.

In 2017, the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum produced an exhibit entitled Images of Internment: The Incarceration of Japanese Americans During World War II to commemorate the seventy-fifth anniversary of FDR’s infamous Executive Order 9066. I visited the show and viewed photographs by Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams, and others.

Seventy-five years later these photos are still relevant and serve as a powerful reminder of the importance of maintaining civil liberties in our democracy.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Learning to See: A Novel of Dorothea Lange by Elise Hooper appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 25, 2019

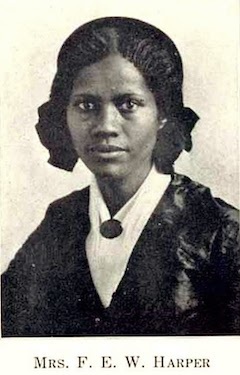

Inspiring Speeches by Frances Watkins Harper, 19th-Century Reformer & Author

Frances Ellen Watkins ( 1825 – 1911), later known as Frances Watkins Harper or Frances E.W. Harper, built her reputation on her various talents, including fiction, essays, poetry, and public speaking. One of America’s first and most successful African-American authors, she was also an active abolitionist, feminist, and conductor on the Underground Railroad.

She launched her writing career in the late 1830s by publishing essays in antislavery journals. At age twenty, her first collection of poems, Autumn Leaves, was published in 1845. She was the first black author to have a short story published (“The Two Offers”) and one of the first to publish a novel (Iola Leroy, 1892).

It was during the 1850s, after the Fugitive Slave Act was passed, that Harper found her voice as a speaker. From that time on, she was in great demand as an orator — hers was a powerful voice promoting African-American and women’s rights. Here are some inspiring excerpts from speeches by Frances Watkins Harper, a 19th-century crusader for justice who shouldn’t be forgotten.

“We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members without receiving the curse in its own soul. You tried that in the case of the Negro…

You white women speak here of rights. I speak of wrongs. I, as a colored woman, have had in this country an education which has made me feel as if I were in the situation of Ishmael, my hand against every man, and every man’s hand against me…

While there exists this brutal element in society which tramples upon the feeble and treads down the weak, I tell you that if there is any class of people who need to be lifted out of their airy nothings and selfishness, it is the white women of America.”

(from a speech at the National Women’s Rights Convention, 1866)

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Frances Watkins Harper

. . . . . . . . . .

“I deem it a privilege to present the Negro, not as a mere dependent asking for Northern sympathy or Southern compassion, but as a member of the body politic who has a claim upon the nation for justice, simple justice, which is the right of every race, upon the government for protection, which is the rightful claim of every citizen, and upon our common Christianity for the best influences which can be exerted for peace on earth and goodwill to man.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There are some rights more precious than the rights of property or the claims of superior intelligence: they are the rights of life and liberty, and to these the poorest and humblest man has just as much right as the richest and most influential man in the country.

Ignorance and poverty are conditions which men outgrow. Since the sealed volume was opened by the crimson hand of war, in spite of entailed ignorance, poverty, opposition, and a heritage of scorn, schools have sprung like wells in the desert dust.

It has been estimated that about two millions have learned to read…. Millions of dollars have flowed into the pockets of the race, and freed people have not only been able to provide for themselves, but reach out their hands to impoverished owners.”

(this and the except above are from a speech before the meeting of the National Council of Women, February 23, 1891, later reprinted in Black Women in Nineteenth-Century American Life: Their Words, Their Thoughts, Their Feelings , edited by Bert James Loewenberg, and Ruth Bogin)

. . . . . . . . . .

8 Poems by Frances Watkins Harper

. . . . . . . . . .

“The tendency of the present age, with its restlessness, religious upheavals, failures, blunders, and crimes, is toward broader freedom, an increase of knowledge, the emancipation of thought, and a recognition of the brotherhood of man; in this movement woman, as the companion of man, must be a sharer …

So close is the bond between man and woman that you can not raise one without lifting the other. The world can not move without woman’s sharing in the movement, and to help give a right impetus to that movement is woman’s highest privilege.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The tendency of the present age, with its restlessness, religious upheavals, failures, blunders, and crimes, is toward broader freedom, an increase of knowledge, the emancipation of thought, and a recognition of the brotherhood of man; in this movement woman, as the companion of man, must be a sharer …

So close is the bond between man and woman that you can not raise one without lifting the other. The world can not move without woman’s sharing in the movement, and to help give a right impetus to that movement is woman’s highest privilege.”

(this and the excerpt above are from a speech titled “Woman’s Political Future,” Columbian Exposition in Chicago, 1893. Published in The World’s Congress of Representative Women, edited by May Sewall, 1894)

. . . . . . . . . .

“The Two Offers” by Frances Watkins Harper

. . . . . . . . . .

“I do not believe in unrestricted and universal suffrage for either men or women. I believe in moral and educational tests. I do not believe that the most ignorant and brutal man is better prepared to add value to the strength and durability of the government than the most cultured, upright, and intelligent woman.

I do not think that willful ignorance should swamp earnest intelligence at the ballot box, nor that educated wickedness, violence, and fraud should cancel the votes of honest men. The unsteady hands of a drunkard can not cast the ballot of a freeman.

The hands of lynchers are too red with blood to determine the political character of the government for even four short years.