Nava Atlas's Blog, page 77

November 5, 2018

Quotes from O Pioneers! by Willa Cather

The 1913 novel O Pioneers! by Willa Cather is written in the spare yet lyrical prose that came to define her style. One of her earliest novel, and one of the most successful on many levels, it explores themes of fate, love, perseverance, family ties, and community. The novel’s central character, Alexandra Bergson, is the daughter of Swedish immigrants who pioneer the harsh, unforgiving land of the Nebraska prairie.

In an unusual move, Alexandra’s father tasks her, in his dying wish, with taking the lead on managing the family farm. He tells his sons to honor the decisions of their sister. Of course, a novel doesn’t move along without conflict, but Cather delivers it without the sentimentality and overwrought prose characteristic of novels of that era.

More than one hundred years after its publication, O Pioneers! still resonates, speaking to the virtues of dignity, hard work, sacrifice, and loyalty. It’s only right and fitting that Alexandra Bergson, a feminist heroine for the ages, finds a route to happiness and contentment. Here are quotes from O Pioneers! that demonstrate the gentle wisdom of this novel.

“Freedom so often means that one isn’t needed anywhere.”

“I like trees because they seem more resigned to the way they have to live than other things do. I feel as if this tree knows everything I ever think of when I sit here. When I come back to it, I never have to remind it of anything; I begin just where I left off.”

Learn more about O Pioneers! by Willa Cather

“I’ve seen it before. There are women who spread ruin through no fault of theirs, just by being too beautiful, too ful of life and love. They can’t help it. People come to them as people go to a warm fire in winter.”

“People have to snatch at happiness when they can, in this world. It is always easier to lose than to find.”

“There are only two or three human stories, and they go on repeating themselves as fiercely as if they had never happened before; like the larks in this country, that have been singing the same five notes over for thousands of years.”

“It’s awfully easy to rush into a profession you don’t really like, and awfully hard to get out of it.”

O Pioneers! on Amazon

“I might as well try to will the sunset over there to my brother’s children. We come and go, but the land is always here. And the people who love it and understand it are the people who own it — for a little while.”

“There is often a good deal of the child left in people who have had to grow up too soon.”

“It’s queer what things one remembers and what things one forgets.”

“Everywhere the grain stood ripe and the hot afternoon was full of the smell of the ripe wheat, like the smell of bread baking in an oven. The breath of the wheat and the sweet clover passed him like pleasant things in a dream.”

“He had got into the habit of seeing himself always in desperate straits. His unhappy temperament was like a cage; he could never get out of it; and he felt that other people, his wife in particular, must have put him there. It had never more than dimly occurred to Frank that he made his own unhappiness.”

“I’ve found it sometimes pays to mend other people’s fences”

“… he felt that men were too weak to make any mark here, that the land wanted to be let alone, to preserve its own fierce strength, its peculiar, savage kind of beauty, its uninterrupted mournfulness.”

“The years seemed to stretch before her like the land; spring, summer, autumn, winter, spring; always the same patient fields, the patient little trees, the patient lives; always the same yearning, the same pulling at the chain—until the instinct to live had torn itself and bled and weakened for the last time, until the chain secured a dead woman, who might cautiously be released.”

“It was to him a very strange and perplexing place, where people wore fine clothes and had hard hearts.”

“Above Marie and Emil, two white butterflies from Frank’s alfalfa field were fluttering in and out among the interlacing shadows; diving and soaring, now close together, now far apart; and in the long grass by the fence the last wild roses of the year opened their pink hearts to die.”

You might enjoy knowing more about Willa Cather

“There is something frank and joyous and young in the open face of the country. It gives itself ungrudgingly to the moods of the season, holding nothing back. Like the plains of Lombardy, it seems to rise a little to meet the sun. The air and the earth are curiously mated and intermingled, as if the one were the breath of the other. You feel in the atmosphere the same tonic, puissant quality that is in the tilth, the same strength and resoluteness.”

“Yes, there would be a dirty way out of life, if one chose to take it. But she did not want to die. She wanted to live and dream — a hundred years, forever! As long as this sweetness welled up in her heart, as long as her breast could hold this treasure of pain!”

“How many times we have walked this path together, Carl. How many times we will walk it again! Does it seem to you like coming back to your own place? Do you feel at peace with the world here?”

“I think we shall be very happy. I haven’t any fears. I think when friends marry, they are safe. We don’t suffer like — those young ones.”

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from O Pioneers! by Willa Cather appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 4, 2018

O Pioneers! by Willa Cather (1913)

O Pioneers! by Willa Cather is one of this esteemed American author’s most iconic novels. One of her earliest full-length works, it was published in 1913. Written in the kind of spare, lyric prose that would become her trademark, the story explores themes of destiny, chance, love, and perseverance. It honors the ideas of community, family ties, and the dignity of work. Never sentimental or verbose, Cather delivers her plots with gentle forward motion. Her characters may be flawed, but they’re rarely weak.

The novel’s central character, Alexandra Bergson, is her parents’ only daughter and oldest child. The Bergsons are Swedish immigrants working the Nebraska prairie land. The Bergsons encounter hardship, naturally. The unforgiving land is difficult to farm, the climate is harsh, and their neighbors, an amalgam of European immigrants, don’t always live harmoniously.

Putting the daughter in charge

When Alexandra’s father John dies, he conveys his desire clearly to his offspring —Alexandra is to run the farm, and her brothers are to follow her lead. They are all to take care of their mother. His final instructions are conveyed from the deathbed:

“Boys,” said the father wearily, “I want you to keep the land together and to be guided by your sister. I have talked to her since I have been sick, and she knows all my wishes. I want no quarrels among my children, and so long as there is one hose there must be one head. Alexandra is the oldest, and she knows my wishes … If she makes mistakes, she will not make so many as I have made. When you marry, and want a house of your own, the land will be divided fairly, according to the courts. But for the next few years you will have it hard, and you must all keep together. Alexandra will manage the best she can.”

It’s difficult to know whether this action of John Bergson reflected anything of real life in those times — remember, this was published in 1913. It seems that a father putting his daughter in charge of the land he did battle with yet loved, when there are a number of sons as well, is quite a feminist statement.

You might also enjoy: Quotes from O Pioneers! by Willa Cather

Success comes with sacrifice

Alexandra did more than just manage. She proved her mettle at managing the business of farming and household management to become one of the most prosperous landowners in the region. This success came with the sacrifice; Alexandra had to forgo the joys of youth and young adulthood. And human nature being what it is, the enterprise wasn’t without conflict with her brothers.

It is the youngest brother, Emil who gets to set foot in the wider world and pursue a college education. Though this is due to the fruits of his family’s hard work, his brothers resent him for it and grow to hate Alexandra for creating such a seismic shift in the family dynamic. Emil’s story, told alongside Alexandra’s, is central to the plot and involves his love interest, Marie, a married woman from the town’s French community.

As in all of Cather’s prairie novels and stories, the land itself becomes a character of sorts, a symbol of a way of life that tested the endurance of the pioneers who lived it. More than one hundred years after its publication, O Pioneers! still resonates, speaking to the virtues of dignity, hard work, sacrifice, and loyalty. It’s only right and fitting that Alexandra Bergson, a feminist heroine for the ages, finds a way to happiness and contentment in the end.

A 1913 Review of O Pioneers!

A Novel Without A Hero: O Pioneers! by Willa Cather from the original review in the New York Times, September, 1913: The hero of the American novel very often starts on the farm, but he seldom stays there; instead he uses it as a spring-board form which to plunge into the mysteries of politics or finance.

Probably the novel reflects a national tendency. To be sure, after we have carefully separated ourselves from the soil, we are apt to talk a lot about the advantages of a return to it, but in most cases it ends there. The average American does not have any deep instinct for the land, or vital consciousness of the dignity and value of the life that may be lived upon it.

The struggle with the untamed land

O Pioneers! is filled with this instinct and this consciousness. It is a tale of the old wood-and-field worshipping races, Swedes and Bohemians, transplanted to Nebraskan uplands, of their struggle with the untamed soil, and their final conquest of it. Miss Cather has written a good story, we hasten to assure the reader who cares for good stories, but she has achieved something finer.

Through a direct, human tale of love and struggle and attainment, a tale that is American in the best sense of the word, there runs a thread of symbolism. It is practically a novel without a hero. There are men in it, but the interest centers in two women — not rivals, but friends, and more especially in the splendid farm-woman, Alexandra.

O Pioneers! by Willa Cather on Amazon

The great feminine

In this new mythology, which is the old, the goddess of fertility once more subdues the barren and stubborn earth. Possibly some might call it a feminist novel, for the who heroines are stronger, cleverer, and better balanced than their husbands and brothers — but we are sure Miss Cather had nothing so inartistic in mind. It is a natural growth, feminine because it is only an expansion of the very essence of femininity.

Instead of calling O Pioneers! a novel without a hero it might be more accurate to call it a novel with three heroines — Alexandra, the harvest-goddess, Marie, poor little spirit of love and youth snatched untimely former poppy-fields, and the Earth itself, patient and bountiful source of all things.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post O Pioneers! by Willa Cather (1913) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 3, 2018

All My Pretty Ones by Anne Sexton (1962)

Anne Sexton (1928 – 1974) was an American poet considered one of the pioneers of modern confessional poetry, though her artistry reached far beyond that genre. Her first collection, To Bedlam and Part Way Back, was published in 1960 to critical and public praise. It was followed by All My Pretty Ones in 1962.

During this period, Anne was receiving not only critical praise but prestigious awards as well. These included the Frost Fellowship, the Shelley Memorial Prize, a Ford Foundation grant, and many others. Sexton struggled mightily with mental illness during this fertile time in her creative life.

By the time she won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1966, she had been hospitalized and attempted suicide several times. Her poetry resonated as much with readers as it did with critics. Following is a review of All My Pretty Ones from its time of publication:

From the original review of All My Pretty Ones by Anne Sexton in the El Paso Herald-Post, October 20, 1962: “A work of art may be a revelation. The higher consciousness of the great artist is evidenced not only by his capacity of ordering his experience but also of having the experience,” Robert Shaw once remarked. And All My Pretty Ones by Anne Sexton brings a poignant assurance that these human capacities are as vital as they ever have been.

Her poetic genius has enabled her to take this language of ours, this same language that so much of our contemporary life uses to make our being — the chatter at a cocktail party, the TV commercial — and create poems that reawaken our wonder at the human capacity for awareness and insight into “the infrared and ultra-violet” of man’s life.

See also: 10 Poems by Anne Sexton, Confessional Poet

All My Pretty Ones follow Sexton’s first volume, To Bedlam and Part Way Back. The thirty-three poem speak with directness and concreteness of a woman’s life that she accepts the pain, the conflict that are a part of life as a “sign and seal of a deep bond with being.” And with her art, Sexton puts some order to doubt, terror and death, and out of the agony glimpses the reality of love.

This world we live in, a world of hydrogen bombs, cold wars, and revolutions, is a world so mobile we can forget our roots are in the soil. It brings pain and darkness to each of us. The poets of our age have reminded us of this over and over, but none has been more immediate, intense, and personal in the full meaning than Anne Sexton

These poems in this rich art of hers give us hope, for as Eric Bently once said, “… no poet lives through anything isolated. What he lives through all his countrymen live through with him.” This world of the same stars Van Gogh once saw will not let you off easy. But the dimensions of your life will be deepened and enriched by them. — Elizabeth D. Campbell

The Complete Poems of Anne Sexton on Amazon

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post All My Pretty Ones by Anne Sexton (1962) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 1, 2018

Jane Austen, the Secret Radical: How She Would Have Liked to Be Read

In Jane Austen, the Secret Radical, author Helena Kelly looks past the grand houses, drawing room dramas, and witty dialogue that have long been the hallmarks of Jane Austen‘s work to bring to light the serious, ambitious, subversive concerns of this beloved writer. Kelly illuminates the radical views — on such subjects as slavery, poverty, feminism, marriage, and the church — that Austen deftly and carefully explored in her six novels, at a time when open criticism was considered treason.

Kelly shows us that Austen was fully aware of what was going on in the world during the turbulent times she lived in, and sure of what she thought of it. Above all, Austen understood that the novel — until then dismissed as mindless and frivolous — could be a meaningful art form, one that in her hands reached unprecedented heights of greatness.

The following is excerpted from Jane Austen, the Secret Radical © 2016 by Helena Kelly. Reprinted by permission with Vintage Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Reading Jane Austen as she would have preferred

Jane talks in one letter about wanting readers who have “a great deal of ingenuity,” who will read her carefully. In wartime, in a totalitarian regime, and in a culture that took the written word far more seriously than we do, she could have expected to find them. Jane expected to be read slowly — perhaps aloud, in the evenings, or over a period of weeks as each volume was borrowed in turn from the circulating library. She expected that her readers would think about what she wrote, would even discuss it with each other.

She never expected to be read the way we read her, gulped down as escapist historical fiction, fodder for romantic fantasies. Yes, she wanted to be enjoyed; she wanted people to feel as strongly about her characters as she did herself. But for Jane a story about love and marriage wasn’t ever a light and frothy confection.

Marriage wasn’t all that romantic

Generally speaking, we view sex as an enjoyable recreational activity; we have access to reliable contraception; we have very low rates of maternal and infant mortality. None of these things were true for the society in which Jane lived. The four of her brothers who became fathers produced, between them, thirty-three children. Three of those brothers lost a wife to complications of pregnancy and childbirth. Another of Jane’s sisters-in-law collapsed and died suddenly at the age of thirty-six; it sounds very much as if the cause might have been the rupturing of an ectopic pregnancy, which was, then, impossible to treat.

Marriage as Jane knew it involved a woman giving up everything to her husband — her money, her body, her very existence as a legal adult. Husbands could beat their wives, rape them, imprison them, take their children away, all within the bounds of the law. Avowedly feminist writers such as Mary Wollstonecraft and the novelist Charlotte Smith were beginning to explore these injustices during Jane’s lifetime. Understand what a serious subject marriage was then, how important it was, and all of a sudden courtship plots start to seem like a more suitable vehicle for discussing other serious things.

No more than a handful of the marriages Jane depicts in her novels are happy ones. And with the possible exception of Pride and Prejudice, even the relationships between Jane’s central characters are less than ideal — certainly not love’s young dream. Marriage mattered because it was the defining action of a woman’s life; to accept or refuse a proposal was almost the only decision that a woman could make for herself, the only sort of control she could exert in a world that must very often have seemed as if it were spiraling into turmoil. Jane’s novels aren’t romantic. But it’s become increasingly difficult for readers to see this.

Jane Austen, the Secret Radical by Helena Kelly on Amazon

A skewed view of Jane Austen’s novels

For readers today opening one of Jane’s novels, there’s an enormous amount standing between them and the text. There’s the passage of two hundred years, for a start, and then there’s everything else — biographies and biopics, the lies and half-truths of the family memoirs, the adaptations and sequels, rewritings and reimaginings.

When it comes to Jane, so many images have been danced before us, so rich, so vivid, so prettily presented. They’ve been seared onto our retinas in the sweaty darkness of a cinema, and the aftereffect remains, a shadow on top of everything we look at subsequently.

It’s hard; it requires an effort for most readers to blink those images away, to be able to see Edward Ferrars cutting up a scissor case (a scene that arguably carries a strong suggestion of sexual violence) rather than the 1990s heartthrob Hugh Grant nervously rearranging the china ornaments on the mantelpiece. By the time you’ve seen Colin-Firth-as-Mr.-Darcy poised to dive into a lake fifty times, it’s made a synaptic pathway in your brain. Indeed, I’d question whether we can get away from that, certainly how we do.

Why has Mr. Darcy Been Attractive to Generations of Women?

What we’ve gotten wrong

And this ought to concern us, because a lot of the images—like the images on the banknote—are simplistic, and some of them are plain wrong. Pemberley isn’t on the scale of the great ducal mansion at Chatsworth; Captain Wentworth doesn’t buy Kellynch Hall for Anne as a wedding present at the end of Persuasion; the environs of Highbury, the setting for Emma, aren’t a golden pastoral idyll. We have, really, very little reason to believe that Jane was in love with Tom Lefroy. But each image colors our understanding in some way or another, from Henry Austen’s careful portrait of his sister as an accidental author to Curtis Sittenfeld’s updated Pride and Prejudice, set in suburban Cincinnati.

The effect of all of them together is to make us read novels that aren’t actually there … I would suggest that when dealing with someone like Jane Austen, we could add another, and more dangerous, class of knowledge; what might be termed the unknown knowns—things we don’t actually know but think we do.

How to take Jane seriously

If we want to be the best readers of Jane’s novels that we can be, the readers that she hoped for, then we have to take her seriously. We can’t make the mistake that the publisher Crosby made and let our eyes slide over what doesn’t seem to be important. We can’t shrug off apparent contradictions or look only for confirmation of what we think we already know. We have to read, and we have to read carefully, because Jane had to write carefully, because she was a woman and because she was living through a time when ideas both scared and excited people.

And once we read like this, we start to see her novels in an entirely new light. Not an undifferentiated procession of witty, ironical stories about romance and drawing rooms, but books in which an authoress reflects back to her readers their world as it really is — complicated, messy, filled with error and injustice.

This is a world in which parents and guardians can be stupid and selfish; in which the Church ignores the needs of the faithful; in which landowners and magistrates — the people with local power — are eager to enrich themselves even when that means driving the poorest into criminality. Jane’s novels, in truth, are as revolutionary, at their heart, as anything that Wollstonecraft or Tom Paine wrote. But by and large, they’re so cleverly crafted that unless readers are looking in the right places — reading them in the right way — they simply won’t understand.

The Biggest Myth About Jane Austen’s Writing Life

An artist, if not a genius

Jane wasn’t a genius — inspired, unthinking; she was an artist. She compared herself to a miniature painter; in her work every stroke of the brush, every word, every character name and every line of poetry quoted, every location, matters.

It’s here, in the novels, that we find Jane — what there is of her to find, after all these years, after all her family’s efforts at concealment. It’s here we find a clever woman, clear-sighted, a woman “of information,” who knew what was going on in the world and what she thought about it. An authoress who knew that the novel, until then widely seen as mindless “trash,” could be a great art form and who did a lot — perhaps more than any other writer — to make it into one.

We’ve grown too accustomed to the other Janes—to Henry’s perfect sister and James-Edward’s maiden aunt; to the romantic, reckless girl in Becoming Jane and the woman on the banknote. I’ll try hard to shake these Janes off. In Jane Austen, Secret Radical, I offer flashes of an imaginary Jane Austen, sometimes in ordinary life, sometimes in the places she revisited in her books, but always primarily as a writer.

They’re intended as glimpses of what the authoress might have been thinking, of how real events and locations, and people, might have made their way into her novels. I don’t claim these as biography; even though they stay close to Jane’s manuscript correspondence, and to her own writing, they’re fiction.

Fiction offers deeper truths

Jane wouldn’t, I think, have disapproved of this approach. Northanger Abbey contains a lengthy passage about history, about its blend of fact and fiction. The naïve heroine, Catherine Morland, states an undoubted truth, that “a great deal” of history is made up: “The speeches that are put into the heroes’ mouths, their thoughts and designs—the chief of all this must be invention.” The older and more intelligent Eleanor Tilney, who reads history chiefly for pleasure, expresses herself “very well contented to take the false with the true.”

For Jane herself, though, fiction isn’t simply an enjoyable embellishment. It can offer deeper truths than fact. It’s in fiction, Jane says, that we should look for “the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties.”

The “truthful fictions” in Jane Austen, the Secret Radical, the glimpses of an unfamiliar woman, should help to prepare readers for novels that will also become suddenly unfamiliar. Each chapter is devoted to one book and suggests how, by forgetting what we think we know, and focusing instead on the historical background, and on the texts themselves, we can make an attempt at reading as Jane intended us to.

You might also enjoy Jane on the Brain: Jane Austen and Empathy

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Jane Austen, the Secret Radical: How She Would Have Liked to Be Read appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 31, 2018

Anne Sexton

Anne Sexton (November 9, 1928 – October 4, 1974), born Anne Gray Harvey, was an American poet and playwright. Though she was considered one of the pioneers of modern confessional poetry, her artistry reached far beyond that genre. Born in Newton, MA, she grew up in a middle-class home in Weston, MA.

Her dysfunctional family life set the stage for her lifelong struggles with mental illness. Her father was an alcoholic, and her mother, a housewife with frustrated literary aspirations. Anne’s later writings reflect an upbringing of abuse and hostility.

A tumultuous young adulthood

In addition to her tumultuous relationship with her parents, Anne had difficulty with school. She was oppositional and often had trouble concentrating. At a boarding high school, she discovered acting and poetry. An attractive young woman with a sense of adventure, she was on the receiving end of much male attention. By age nineteen, she eloped with Alfred “Kayo” Sexton II, even while engaged to another.

When Kayo was serving in Korea, Anne embarked on a modeling career and a series of extramarital affairs. Around the years of giving birth to their daughters in 1953 and 1955, Anne became severely depressed. She had her first manic episode in 1954 and attempted suicide on several occasions.

Struggles with mental illness and the start of a writing career

Anne likely suffered from what’s now referred to as bipolar disorder, then called manic depression. It was during these first, destabilizing years, that her therapist suggested that she begin to write.

Joining some Boston-area writing groups proved fruitful. Anne connected with established poets like Maxine Kumin, who became a lifelong friend. The two women regularly critiqued one another’s poetry and wrote four children’s books together. Anne also studied with Robert Lowell at the same time as Sylvia Plath (with whom she was also good friends) and George Starbuck.

Anne felt a great deal of kinship with Sylvia Plath, and like her, often expressed a death wish in her poems, as in “Wanting to Die“. When she learned of Plath’s death by suicide, she seemed almost envious.

In 1959, both of her parents died, and though her relationship with them had been fraught, to say the least, the trauma led to more mental breakdowns.

Her first collection, To Bedlam and Part Way Back, was published in 1960 to critical and public praise. It was followed by All My Pretty Ones in 1962. Anne was receiving not only critical praise but prestigious awards as well. These included the Frost Fellowship, the Shelley Memorial Prize, a Ford Foundation grant, and many others.

You might also like: 10 Poems by Anne Sexton, Confessional Poet

Pulitzer Prize for Live or Die

In 1967, Anne received the Pulitzer Prize for poetry for Live or Die (1966). Despite her immense list of accomplishments, the press often referred bizarrely to her as a “housewife” when covering her receipt of this honor. The Associated Press coverage from May, 1967 reads in part:

“Mrs. Anne Sexton, housewife winner of the 1967 Pulitzer Prize for poetry, says, ‘My topic is my family, my life. It’s corny, but I try to write the truth.’ Mrs. Sexton, 38-year-old mother of two daughters, won the $500 prize for Live or Die, published last year.

‘It’s a book of instruction. Live or die. Make up your mind. If you’re going to hang around don’t ruin everything. Don’t poison the world … The poem will tell me if I’ve found the truth. Some poems don’t, and they’re failures. Usually I think I’ve found the truth. But a poem owns its own truth. Some break you up or hurt.'”

Live or Die is contains some semi-autobiographical accounts of her recovery, or attempted recovery, from mental illness. The collection is far from the musings of a suburban housewife, even though coverage of the prize attempted to portray her in such a light

Productive, destructive years

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Anne spread her wings. Her play, Mercy Street was staged off-Broadway in 1969. She wrote prose-poems with a feminist bent in the collection titled Transformations (1972). But all the accomplishment and accolades couldn’t stave off her deteriorating mental health. During this time, she continued to attempt suicide and became dependent on alcohol and medications.

Anne’s tumultuous marriage to Kayo came to an end in 1973, and though it had long been unhappy, she was left unmoored. Depression led to self-isolation. On October 4, 1974, she had a working lunch with her close friend Maxine Kumin. She committed suicide by asphyxiation by carbon monoxide in her garage. She was not quite 46 years old.

Anne Sexton: A Biography by Diane Wood Middlebrook is a portrait of a talented yet deeply troubled woman. She’s described as bewitching, complex, exasperating, and self-destructive:

“From the day Sexton began writing in 1956, her poetry and inner life worked in tandem to give her eighteen years of wild productivity, which produced nearly a dozen books. Among her achievements were a Pulitzer Prize, professorships, stardom in a performing musical group called Anne Sexton and Her Kind, attempts to write for theater, and a hectic emotional life, which severely strained her husband, her daughters, and her lovers and friends … In her later years, she reached desperately toward religious belief.”

Anne Sexton page on Amazon

Posthumous works and legacy

One of Anne’s daughters, Linda Gray Sexton, edited the posthumous collections of her poems. These included 45 Mercy Street (1976) and Words for Dr. Y: Uncollected Poems with Three Stories (1978).

Anne Sexton was considered a master at the craft of poetry. To pigeonhole her as a confessional poet undervalues the breadth of her talent. Though many of her poems speak to her personal experience with depression, suicide attempts, and fraught family relationships, a great deal of her work wasn’t at all autobiographical. Her life might have been a trial, but her writing was artful and is firmly established in the canon of American poetry.

More about Anne Sexton on this site

10 Poems by Anne Sexton, Confessional Poet

Major Works

To Bedlam and Part Way Back

Live or Die

The Death Notebooks

Love Poems

All My Pretty Ones

The Awful Rowing Toward God

Transformations

45 Mercy Street

Words for Dr. Y

The Complete Works of Anne Sexton

More information

Wikipedia

Modern American Poetry

Poetry Foundation

Poem Hunter

Biographies

Anne Sexton: A Biography by Diane Wood Middlebrook

Anne Sexton: A Portrait in Letters edited by Linda Gray Sexton

Research

Anne Sexton papers at the Harry Ransom Center

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing

The post Anne Sexton appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 30, 2018

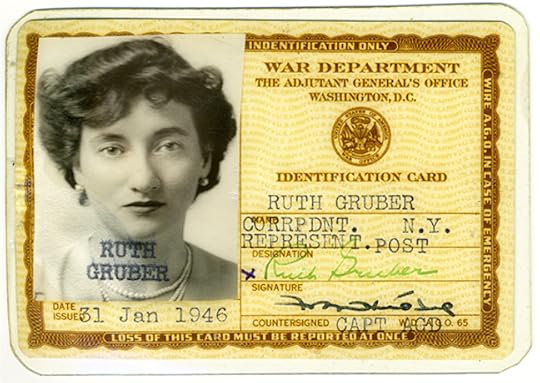

Ruth Gruber: Journalist, Documentary Photographer, Humanitarian

Ruth Gruber (1911 – 2016) led a life that was so incredible, it could have been a movie. And in fact, just one of the many courageous episodes in her 105-year life was made into a film. Ruth’s multi-faceted career as a journalist and documentary photographer has been somewhat forgotten, and as with many women who were ahead of their time, should be revisited and celebrated.

The daughter of Russian-Jewish immigrants, Ruth was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. She was a brilliant student with a passion for Jewish culture, and always loved to write. At age fifteen she started college, and was only twenty when she completed her doctorate in 1931 at the University of Cologne in Germany. That made her the world’s youngest Ph.D at the time.

Being a young Jewish woman in Germany in the early 1930s was risky — the Nazis were coming into power. But risk wasn’t something Ruth avoided. She even went to Nazi rallies, getting a close view of Hitler at one of them. She later recalled that the sound of his twisted, hate-filled voice was one she could never forget. With her first-hand look at the rise of Nazism, Ruth returned to the U.S. and began writing for the New York Herald Tribune. Her first major series was about women’s lives under fascism.

“General” Ruth Gruber

At the start of World War II, Ruth worked as Special Assistant to Harold Ickes, one of President Roosevelt’s cabinet members. In 1944, he assigned her a secret mission — to help rescue Jewish refugees from nineteen Nazi-occupied countries and escort them to the U.S. on a military ship. Numbering nearly one thousand, they were invited as the president’s “guests” — the only attempt by the U.S. to shelter Jews during the war.

“You’re going to be given the rank of simulated general,” Ickes told her. “If you’re shot down and the Nazis capture you as a civilian, they can kill you as a spy. But as a general, according to the Geneva Convention, they have to give you food and shelter and keep you alive.”

Ruth escorted the refugees on a perilous ocean journey, only to have the U.S. refuse them, locking them behind barbed-wire in an Ontario fort. Ruth continued to lobby for them until they were finally given asylum in 1946. This dramatic experience inspired the 2001 film Haven, with Natasha Richardson in the role of Ruth Gruber.

British actress Natasha Richardson looked nothing like Ruth Gruber,

but Haven (2001) was a decent film about Ruth’s rescue of nearly 1,000 Jewish refugees

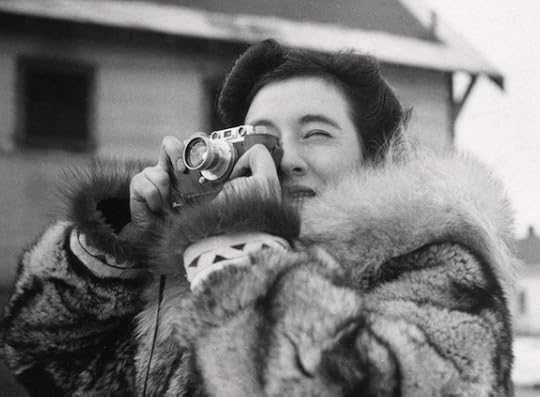

The ship Exodus

After the war, Ruth left her government post and return to journalism. Covering the story of the ship Exodus in 1947 was another dramatic episode in her career. As the ship carrying more than 4,500 Holocaust survivors to what was then Palestine neared the port of Haifa, the British navy intercepted it. The passengers were forced into the already overcrowded refugee camps in Cyprus. As a correspondent for the New York Herald, Ruth documented the barbaric conditions with her camera as well as her pen.

The book she wrote about the experience, Exodus 1947, inspired Leon Uris’s famous book and screenplay, Exodus, which helped turn public sentiment in favor of a Jewish homeland.

In the 1950s, Ruth married and had two children. She slowed down, but not for long. Even getting older didn’t stop her. “Whenever I saw that Jews were in danger,” she declared, “I covered that story.” In 1985, already in her mid-seventies, she did extensive coverage of the rescue of Ethiopian Jews. She continued traveling widely well into her nineties, lecturing about her experiences as a journalist and a witness to history in the making.

Ruth Gruber with Jewish Refugees, 1946 (Ruth is 4th from left in the back row)

Ruth Gruber’s legacy

Ruth Gruber was not only a witness to history as it unfolded, but helped shape historic events, concerning the plight of displaced Jews. She received numerous awards for her work as a journalist and human rights advocate, two sides of her work that often overlapped.

In addition to the television film Haven mentioned above, Ruth’s autobiography’s Ahead of Time: My Early Years as a Foreign Correspondent (1991) was the basis of a documentary. Titled Ahead of Time, this film is quite hard to come by, unfortunately.

“I had two tools to fight injustice — words and images, my typewriter and my camera,” she said. “I just felt that I had to fight evil, and I’ve felt like that since I was 20 years old. And I’ve never been an observer. I have to live a story to write it.”

In addition to the many newspapers she contributed to, Ruth was also the author of nineteen books that detailed her experiences around the globe. Some of her titles in addition to those mentioned earlier include Haven, Raquela, Inside of Time, and Rescue.

Many of Ruth Gruber’s documentary photographs are archived at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. Her life and achievements were celebrated in this appreciation and obituary in the New York Times.

A few quotes by Ruth Gruber

“Everyone can look inside his or her soul and decide what he or she can do to make a world at peace, to end this fighting that goes on every day around the world.”

“I had two tools to fight injustice — my typewriter and my camera.”

“You should have dreams, you should have visions. Never let any obstacle stop you.”

Ruth Gruber page on Amazon

More about Ruth Gruber

Wikipedia

Interview on the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum website

Ahead of Time (film): The Extraordinary Journey of Ruth Gruber

Jewish Women’s Archive

Obituary in the Washington Post

You might also enjoy: 6 Female Journalist of the World War II Era

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Ruth Gruber: Journalist, Documentary Photographer, Humanitarian appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 29, 2018

Women’s Writing Conferences and Retreats in the U.S.

Why should you consider attending women’s writing conferences and retreats (including, of course, women-identified writers)? Pretty much the same reason a lot of us enjoy women-only reading groups. Dudes just bring a different energy to the room, and sometimes we just need to be in a setting where our voices are sure to be heard, where we feel supported and valued.

There are lots of benefits to attending writer’s conferences, not the least of which is networking. You’ll meet writers in all stages of their careers; learn to pitch yourself and your work efficiently, hone your skills, get constructive critiques, and more. It’s a rare attendee that doesn’t leave a conference feeling energized and inspired.

Many conferences offer a direct route to meeting agents and editors, as well. This listing of women’s writing conferences and retreats in the U.S. is by no means exhaustive, so if you know of any others we should list, please contact us. We’re planning a listing of global women’s writing conferences soon, so please check back!

Anne LaBastille Women’s Writing Weekend

When: July of each year

Where: Adirondacks, New York State

Learn more: ALWWW

From the website: “Join a group of like-minded women for a reading and writing retreat. Activities will include writing workshops, reflective paddling, arts-based activities, technical writing and experiential learning, and Adirondack-based readings to contemplate the role of sense of place in nature writing.”

BinderCon: The Conference & Community For Women And Gender Variant Writers

When: Last one held in 2017; subscribe at site below for updates

Where: New York City and Los Angeles

Learn more: BinderCon

From the website: “BinderCon is a writing conference and community for women and gender variant writers. Born out of a community of over 37,000 writers, our conference is a uniquely powerful, supportive, and career-changing event.”

C.D. Wright Women Writers Conference

When: November of each year

Where: University of Central Arkansas in Conway

Learn more: C.D. Wright Women Writers Conference

From the website: “The mission of the C.D. Wright Women Writers Conference is to recognize, promote, and encourage women-identifying writers with special emphasis given to writing inspired by or written in the south.”

Festival of Women Writers at Hobart Book Village

When: Early September of each year

Where: Hobart, New York

Learn more: Festival of Women Writers

From the website: “Since its inception, the Festival has created space for established and emerging women writers to share their insights and skills through a variety of writing activities and public readings with audiences throughout Delaware County, the state of New York, and beyond.”

Hedgebrook Women Playwrights Festival

When: June of each year

Where: Langley & Seattle, WA

Learn more: WPF

From the website: “Hedgebrook offers a variety of opportunities for writers to hone their craft. For over twenty years, the Hedgebrook Women Playwrights Festival has proudly supported the creation and development of hundreds of new theatrical works by some of the most exciting playwrights of our time—who have gone on to become Pulitzer Prize, Tony, Obie, Emmy and Golden Globe award winners, as well as McArthur Genius Fellows.”

International Women’s Writing Guild Summer Conference

When: July of each year

Where: Allentown, PA

Learn more: IWWG Summer Conference

From the website: “Over two dozen workshops ranging from three to six days in length and spanning fiction, poetry, memoir, creative nonfiction, screenwriting, playwriting, writing as performance, social justice, multi-genre, and mixed media.”

Jennifer Louden Retreats and Writing Intensives

When: Several times throughout the year

Where: Taos, NM, Mexico, and other locations

Learn more: Jennifer Louden Retreats and Writing Intensives

From the website: “The retreats I create are among the best on the planet. Wow, that’s a bold claim. Okay, I can’t know that for a fact, but what I do know is hundreds of women over the course of 20+ years have told me, ‘I have been to so many retreats and yours are the best.’”

Kentucky Women’s Writers Conference

When: September of each year

Where: Lexington, KY

Learn more: Kentucky Women’s Writers Conference

From the website: “Kentucky Women Writers is the longest running literary festival of women in the nation, launched by UK in 1979 to showcase the talents and issues unique to female writers.”

Literary Women

When: March of each year

Where: Long Beach, CA

Learn more: Literary Women

From the website: “The committee that organizes the Festival is comprised of twenty-five volunteers. They believe in the continuing need to provide the Long Beach community with a cultural forum which reflects its diversity of literary interests. As succeeding generations of women continue to support the event, it is apparent the intentions of the original committee were well-founded and continue to be relevant today.”

Story Circle Network: For Women with Stories to Tell

When: July of each year

Where: Austin, TX

Learn more: SCN

From the website:“Stories from the Heart IX will bring women from around the country to celebrate our stories and our lives. Through writing, reading, listening, and sharing, we will discover how personal narrative is a healing art, how we can gather our memories, how we can tell our stories. We welcome readers, writers, storytellers, and any woman with a past, present, and future.”

Women Fiction Writer’s Annual Retreat

When: September of each year

Where: Albuquerque

Learn More: WFWA Retreat

From the website: “The WFWA Retreat is a craft and networking event. It’s an opportunity to talk about women’s fiction – both the writing and marketing aspects – with like-minded writers in a relaxed atmosphere.”

Women Reading Aloud

When: April of each year

Where: Sea Girt, NJ

Learn more: WomenReadingAloud.org

From the website: “WOMEN READING ALOUD will host its 9th Writer’s Weekend Retreat in NJ devoted to women writers who are looking for time to write in a nurturing environment … Begin the day with a walk on the beach. Discover your authentic voice through writing workshops modeled after the Amherst Writers and Artists Method. This method allows writers to flourish at every stage of the creative journey.”

Women Writing the West

When: October of each year

Where: Walla Walla, WA

Learn more: WWTW

From the website: “In 2018, Women Writing the West head to the Pacific Northwest for the 24th Annual Conference.” The conference covers many areas of the craft of writing, for women who use the American West as inspiration.

Workshop for Women Writers of Color

When: November of each year

Where: Pendle Hill, Wallingford, PA

Learn more: Workshop for Women Writers of Color

From the website: “Welcome women of color writers! We can often find it a lonely and daunting experience as we seek to make our contributions in fields dominated by white men, whether in academia or other genres of fiction or non-fiction. Let us come together as women of color to share our writing work in progress, celebrate our diverse voices, confront our common barriers, and build a sisterly community of support for the challenges ahead.”

Young Women Writers Workshop

When: April of each year

Where: Colorado Springs, CO

Learn more: YWWW

From the website: “As a young woman between the ages of 18 and 30-ish, you’re a unique kind of writer. Your needs and aspirations are different from those of writers who are either of a different generation or are, well, male. You aspire to write about the issues and challenges that face your contemporaries, your world. That means finding forms and structures that are different from what has come before. If that resonates, this retreat is for you.”

Young Women’s Writing Workshop

When: July of each year

Where: Smith College, MA

Learn more: YWWW

From the website: “With so few writing programs that cater exclusively to high school girls, Smith’s Young Women’s Writing Workshop allows you to explore your writing in a creative and supportive environment that fosters your love of writing in a variety of mediums.”

Plus …

If you’re looking for something a little more of a writing vacation, you might enjoy perusing this list of international retreats — some specifically for women.

And finally, there’s the AWP Conference, which is for writers of all genders, but we list it here because it’s kind of the grand dame of writers conferences — four jam-packed days of readings, workshops, and panels. Probably an amazing networking event. As their site says, “Everyone should go to AWP at least once.”

When: Spring; usually March or April

Where: Location changes each year

Learn more: AWP Conference

From the website: “The Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP) is one of the largest and most popular writing conferences in the world. With more than 15,000 annual participants and 800 exhibitors, it’s more than a conference or book fair – it’s an event. AWP is an essential experience for writers, students, teachers and academics alike.”

The post Women’s Writing Conferences and Retreats in the U.S. appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Jane on the Brain: Jane Austen and Empathy

Jane on the Brain: Exploring the Science of Social Intelligence with Jane Austen by Wendy Jones (Pegasus Books, © 2017) is an exploration of how Jane Austen was able to capture human psychology via relatable characters in compelling stories. Following is an excerpt from the book introducing the role of empathy in Austen’s novels, but first, a few words from the publisher:

“Why is Jane Austen so phenomenally popular? Why do we read Pride and Prejudice again and again? Why do we delight in Emma’s mischievous schemes? Why do we care about the suffering of Anne Elliot in Persuasion?

We care because it is our biological destiny to be interested in people and their stories — the human brain is a social brain. And Austen’s characters are so believable that, for many of us, they are not just imaginary beings, but friends whom we know and love. And thanks to Austen’s ability to capture the breadth and depth of human psychology so richly, we feel that she empathizes with us, her readers.

… An Austen scholar and practicing therapist, Wendy Jones explores the many facets of social intelligence and juxtaposes them with the Austen canon. Brilliantly original and insightful, this fusion of literature, psychology, and neuroscience provides a heightened understanding of one of our most beloved cultural institutions — and our own minds.”

The following excerpt is from Jane on the Brain: Exploring the Science of Social Intelligence with Jane Austen, © 2017 by Wendy Jones (Pegasus Books). Reprinted with permission. All other rights reserved.

Jane Austen’s stories: Mirroring, identification and empathy

Jane Austen’s stories not only convey empathy through mirroring and identification, but they’re about empathy as well — who has it, who lacks it, and how some of her characters deepen their capacity for this important quality. Her novels get us to focus on the experience of empathy (neuroscientists would say they prime us to think about it) by showing its value repeatedly.

So we find ourselves reflected in novels that are all about the value of being able to find yourself reflected in other minds and hearts. Yet we’re not fascinated by empathy because it’s brought to our attentions, but rather we pay attention because empathy is essential to our well-being. And this is yet another reason we’re drawn to Austen — she understands this about us.

Perhaps it seems strange to characterize Austen’s novels as being about empathy. After all, Austen’s great subject is love: its different varieties, its frustrations, its nuances, and, above all, its satisfactions. And not just love between couples, but also between friends, parents and children, siblings. Austen certainly understood this most precious of human emotional resources.

Jane on the Brain by Wendy Jones

is available in all formats on Amazon

and wherever books are sold

Placing empathy front and center

But there’s no contradiction here. Austen’s novels show again and again that the most complete and satisfying relationships rely on perspective taking, understanding, and emotional resonance. Whatever its other features—gratitude, esteem, passion, nurturing—at its core, true love is empathy. Think about all of Austen’s happy couples and you’ll see that this is the case. Anne of Persuasion might be more intuitive and passionate than Elizabeth of Pride and Prejudice, but sensitivity and understanding lead to happy endings for both of them.

In placing empathy front and center, Austen knew what she was doing. For Austen is no mere copyist of nature, but a deeply thoughtful novelist who explores the morality as well as the psychology of the social brain, those aspects of the mind-brain that imbue our relationships.

This was brought home to me recently when I tried to read the novelist Georgette Heyer, a twentieth-century writer who emulated Austen. Here were all the window dressings of Austen’s fiction, the Masterpiece Theatre costumes, plots, and themes, but hollowed out, not only of Austen’s distinctively brilliant style, but also of her philosophical and psychological depth. With apologies to all the Austen fans who cut their teeth on Heyer, I found her unreadable. In the humble guise of the novel of manners, a genre that focuses on social conduct, Austen’s works draw out the moral implications of being human: What do we owe one another ethically, and how do we go about fulfilling this obligation?

The simple answer: We owe one another the kinds of consideration and treatment that help all of us not only to satisfy our basic needs, but to achieve well-being and self-esteem. And this depends on empathy, the key to understanding another person’s needs. And so Emma caters to her needy, hypochondriacal, and often ridiculous father in Emma. So Edmund becomes young Fanny’s friend and advocate in Mansfield Park. So Elizabeth in Pride and Prejudice tolerates the more absurd members of her family with calm consideration.

In that last family, we might note that it’s with regard to this fundamental ethical obligation that Mr. Bennet fails so completely. Rather than helping his foolish wife to develop whatever potential she might have, he retreats to sarcasm to console himself for having to endure her company. As a result, she remains as silly as ever, learning only to ignore a husband she can’t understand and who doesn’t empathize with her.

You might also enjoy: The Biggest Myth About Jane Austen’s Writing Life

Sympathizing with others’ points of view

When Austen’s characters demonstrate kindness and tolerance, it’s because they’re able to imagine and sympathize with life from the point of view others. Emma indulges her father’s many absurdities because she can see that his worries are real to him. Edmund imagines what it’s like to be young, lonely, and intimidated in a new place, and so he’s kind to Fanny. Elizabeth knows that she might not be able to change her mother, but that failing to show her respect would be hurtful and accomplish nothing.

Austen’s best heroine, Anne Elliot of Persuasion, owes her goodness and capability to her capacity for empathy. She can see from others’ perspectives, and this guides her feelings and behavior. As Wentworth, the man she loves, eventually realizes, there is “no one so proper, so capable, as Anne.”

Empathy is the core quality of all moral action

For Austen, empathy is the core quality of all moral action. Here, Austen agrees with the philosopher David Hume, a near contemporary. In our own day, similar conclusions have been advanced by Simon Baron-Cohen, a neuroscientist who equates evil with a lack of empathy, and Frans de Waal, a philosopher and primatologist who views our capacity for moral action as grounded in empathy, which we find in less developed forms in other primates.

Above and beyond the kindness and understanding that empathy creates, it’s valuable because it unlocks the prison house of cosmic loneliness that threatens each of us with a life sentence of solitary confinement. Anglo-European politics, philosophy, and psychology have emphasized our separateness, condemned us without a trial, insisting that we’re stuck in a container, the body, looking out through windows, the eyes. We’re born alone and we die alone, even if other people are near us for these two defining events in the life cycle of every human.

But the latest work in social intelligence tells us that we’re profoundly interconnected in terms of brain, body, and mind. This has been a key insight of the literary imagination all along, that fund of wisdom and observation found in literature. In terms of understanding our connections with one another, no author is greater than Austen. And she shows that such connections depend on empathy, on being able to enter into the thoughts and feelings of others. Through such exchanges, people find meaning and purpose in their lives.

Learn more about Wendy Jones:

Facebook.com/WendyJonesAuthor

Instagram.com/WendyJonesAuthor

Twitter.com/JaneBrainBook

Goodreads.com/author/show/17563171.Wendy_Jones

See also: On First Reading Pride and Prejudice

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Jane on the Brain: Jane Austen and Empathy appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 26, 2018

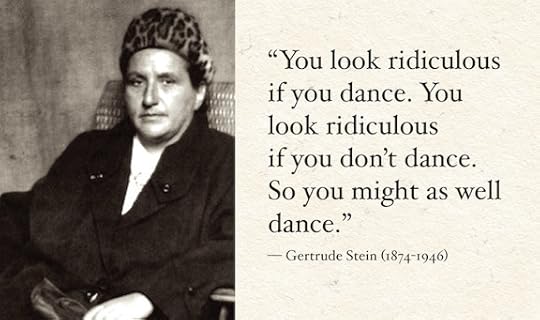

“Objects” from Tender Buttons by Gertrude Stein (1914)

One of Gertrude Stein’s earliest published works, Tender Buttons (1914) is this delightfully perplexing author’s attempt to “create a word relationship between the word and the things seen.”

Especially in the first years since its publication, critics have been divided between praising Tender Buttons as a masterwork of of experimental cubist literature, or trashing it as pure nonsense. Contemporary interpretations tend to find it praiseworthy. Whatever camp you find yourself in, it’s hard to dismiss the fact that this slim volume of prose poetry is entertaining, if more than occasionally head-scratching. You can read two original reviews from the time of its 1914 publication here.

Tender Buttons is divided into more or less equal parts: “Objects,” “Food,” and “Rooms.” Following is the portion “Objects” in its entirety; you can read the rest of the book on Project Gutenberg, as it is in the public domain, but there is such pleasure in reading it as a book in hand rather than on a screen. Tender Buttons is in the public domain.

“Objects” from Tender Buttons by Gertrude Stein

A CARAFE, THAT IS A BLIND GLASS.

A kind in glass and a cousin, a spectacle and nothing strange a single hurt color and an arrangement in a system to pointing. All this and not ordinary, not unordered in not resembling. The difference is spreading.

GLAZED GLITTER.

Nickel, what is nickel, it is originally rid of a cover.

The change in that is that red weakens an hour. The change has come. There is no search. But there is, there is that hope and that interpretation and sometime, surely any is unwelcome, sometime there is breath and there will be a sinecure and charming very charming is that clean and cleansing. Certainly glittering is handsome and convincing.

There is no gratitude in mercy and in medicine. There can be breakages in Japanese. That is no programme. That is no color chosen. It was chosen yesterday, that showed spitting and perhaps washing and polishing. It certainly showed no obligation and perhaps if borrowing is not natural there is some use in giving.

A SUBSTANCE IN A CUSHION.

The change of color is likely and a difference a very little difference is prepared. Sugar is not a vegetable.

Callous is something that hardening leaves behind what will be soft if there is a genuine interest in there being present as many girls as men. Does this change. It shows that dirt is clean when there is a volume.

A cushion has that cover. Supposing you do not like to change, supposing it is very clean that there is no change in appearance, supposing that there is regularity and a costume is that any the worse than an oyster and an exchange. Come to season that is there any extreme use in feather and cotton. Is there not much more joy in a table and more chairs and very likely roundness and a place to put them.

A circle of fine card board and a chance to see a tassel.

What is the use of a violent kind of delightfulness if there is no pleasure in not getting tired of it. The question does not come before there is a quotation. In any kind of place there is a top to covering and it is a pleasure at any rate there is some venturing in refusing to believe nonsense. It shows what use there is in a whole piece if one uses it and it is extreme and very likely the little things could be dearer but in any case there is a bargain and if there is the best thing to do is to take it away and wear it and then be reckless be reckless and resolved on returning gratitude.

Light blue and the same red with purple makes a change. It shows that there is no mistake. Any pink shows that and very likely it is reasonable. Very likely there should not be a finer fancy present. Some increase means a calamity and this is the best preparation for three and more being together. A little calm is so ordinary and in any case there is sweetness and some of that.

A seal and matches and a swan and ivy and a suit.

A closet, a closet does not connect under the bed. The band if it is white and black, the band has a green string. A sight a whole sight and a little groan grinding makes a trimming such a sweet singing trimming and a red thing not a round thing but a white thing, a red thing and a white thing.

The disgrace is not in carelessness nor even in sewing it comes out out of the way.

What is the sash like. The sash is not like anything mustard it is not like a same thing that has stripes, it is not even more hurt than that, it has a little top.

Tender Buttons: Objects by Gertrude Stein

presents the first third of the book only, with illustrations by Lisa Congdon

Available on Amazon

A BOX.

Out of kindness comes redness and out of rudeness comes rapid same question, out of an eye comes research, out of selection comes painful cattle. So then the order is that a white way of being round is something suggesting a pin and is it disappointing, it is not, it is so rudimentary to be analysed and see a fine substance strangely, it is so earnest to have a green point not to red but to point again.

A PIECE OF COFFEE.

More of double.

A place in no new table.

A single image is not splendor. Dirty is yellow. A sign of more in not mentioned. A piece of coffee is not a detainer. The resemblance to yellow is dirtier and distincter. The clean mixture is whiter and not coal color, never more coal color than altogether.

The sight of a reason, the same sight slighter, the sight of a simpler negative answer, the same sore sounder, the intention to wishing, the same splendor, the same furniture.

The time to show a message is when too late and later there is no hanging in a blight.

A not torn rose-wood color. If it is not dangerous then a pleasure and more than any other if it is cheap is not cheaper. The amusing side is that the sooner there are no fewer the more certain is the necessity dwindled. Supposing that the case contained rose-wood and a color. Supposing that there was no reason for a distress and more likely for a number, supposing that there was no astonishment, is it not necessary to mingle astonishment.

The settling of stationing cleaning is one way not to shatter scatter and scattering. The one way to use custom is to use soap and silk for cleaning. The one way to see cotton is to have a design concentrating the illusion and the illustration. The perfect way is to accustom the thing to have a lining and the shape of a ribbon and to be solid, quite solid in standing and to use heaviness in morning. It is light enough in that. It has that shape nicely. Very nicely may not be exaggerating. Very strongly may be sincerely fainting. May be strangely flattering. May not be strange in everything. May not be strange to.

DIRT AND NOT COPPER.

Dirt and not copper makes a color darker. It makes the shape so heavy and makes no melody harder.

It makes mercy and relaxation and even a strength to spread a table fuller. There are more places not empty. They see cover.

Tender Buttons by Gertrude Stein (the centennial edition) on Amazon

NOTHING ELEGANT.

A charm a single charm is doubtful. If the red is rose and there is a gate surrounding it, if inside is let in and there places change then certainly something is upright. It is earnest.

MILDRED’S UMBRELLA.

A cause and no curve, a cause and loud enough, a cause and extra a loud clash and an extra wagon, a sign of extra, a sac a small sac and an established color and cunning, a slender grey and no ribbon, this means a loss a great loss a restitution.

A METHOD OF A CLOAK.

A single climb to a line, a straight exchange to a cane, a desperate adventure and courage and a clock, all this which is a system, which has feeling, which has resignation and success, all makes an attractive black silver.

A RED STAMP.

If lilies are lily white if they exhaust noise and distance and even dust, if they dusty will dirt a surface that has no extreme grace, if they do this and it is not necessary it is not at all necessary if they do this they need a catalogue.

A BOX.

A large box is handily made of what is necessary to replace any substance. Suppose an example is necessary, the plainer it is made the more reason there is for some outward recognition that there is a result.

A box is made sometimes and them to see to see to it neatly and to have the holes stopped up makes it necessary to use paper.

A custom which is necessary when a box is used and taken is that a large part of the time there are three which have different connections. The one is on the table. The two are on the table. The three are on the table. The one, one is the same length as is shown by the cover being longer. The other is different there is more cover that shows it. The other is different and that makes the corners have the same shade the eight are in singular arrangement to make four necessary.

Lax, to have corners, to be lighter than some weight, to indicate a wedding journey, to last brown and not curious, to be wealthy, cigarettes are established by length and by doubling.

Left open, to be left pounded, to be left closed, to be circulating in summer and winter, and sick color that is grey that is not dusty and red shows, to be sure cigarettes do measure an empty length sooner than a choice in color.

Winged, to be winged means that white is yellow and pieces pieces that are brown are dust color if dust is washed off, then it is choice that is to say it is fitting cigarettes sooner than paper.

An increase why is an increase idle, why is silver cloister, why is the spark brighter, if it is brighter is there any result, hardly more than ever.

You might also like: 16 Slightly Absurd Quotes by Gertrude Stein

A PLATE.

An occasion for a plate, an occasional resource is in buying and how soon does washing enable a selection of the same thing neater. If the party is small a clever song is in order.

Plates and a dinner set of colored china. Pack together a string and enough with it to protect the centre, cause a considerable haste and gather more as it is cooling, collect more trembling and not any even trembling, cause a whole thing to be a church.

A sad size a size that is not sad is blue as every bit of blue is precocious. A kind of green a game in green and nothing flat nothing quite flat and more round, nothing a particular color strangely, nothing breaking the losing of no little piece.

A splendid address a really splendid address is not shown by giving a flower freely, it is not shown by a mark or by wetting.

Cut cut in white, cut in white so lately. Cut more than any other and show it. Show it in the stem and in starting and in evening coming complication.

A lamp is not the only sign of glass. The lamp and the cake are not the only sign of stone. The lamp and the cake and the cover are not the only necessity altogether.

A plan a hearty plan, a compressed disease and no coffee, not even a card or a change to incline each way, a plan that has that excess and that break is the one that shows filling.

A SELTZER BOTTLE.

Any neglect of many particles to a cracking, any neglect of this makes around it what is lead in color and certainly discolor in silver. The use of this is manifold. Supposing a certain time selected is assured, suppose it is even necessary, suppose no other extract is permitted and no more handling is needed, suppose the rest of the message is mixed with a very long slender needle and even if it could be any black border, supposing all this altogether made a dress and suppose it was actual, suppose the mean way to state it was occasional, if you suppose this in August and even more melodiously, if you suppose this even in the necessary incident of there certainly being no middle in summer and winter, suppose this and an elegant settlement a very elegant settlement is more than of consequence, it is not final and sufficient and substituted. This which was so kindly a present was constant.

A LONG DRESS.

What is the current that makes machinery, that makes it crackle, what is the current that presents a long line and a necessary waist. What is this current.

What is the wind, what is it.

Where is the serene length, it is there and a dark place is not a dark place, only a white and red are black, only a yellow and green are blue, a pink is scarlet, a bow is every color. A line distinguishes it. A line just distinguishes it.

A RED HAT.

A dark grey, a very dark grey, a quite dark grey is monstrous ordinarily, it is so monstrous because there is no red in it. If red is in everything it is not necessary. Is that not an argument for any use of it and even so is there any place that is better, is there any place that has so much stretched out.

A BLUE COAT.

A blue coat is guided guided away, guided and guided away, that is the particular color that is used for that length and not any width not even more than a shadow.

A PIANO.

If the speed is open, if the color is careless, if the selection of a strong scent is not awkward, if the button holder is held by all the waving color and there is no color, not any color. If there is no dirt in a pin and there can be none scarcely, if there is not then the place is the same as up standing.

This is no dark custom and it even is not acted in any such a way that a restraint is not spread. That is spread, it shuts and it lifts and awkwardly not awkwardly the centre is in standing.

A CHAIR.

A widow in a wise veil and more garments shows that shadows are even. It addresses no more, it shadows the stage and learning. A regular arrangement, the severest and the most preserved is that which has the arrangement not more than always authorised.

A suitable establishment, well housed, practical, patient and staring, a suitable bedding, very suitable and not more particularly than complaining, anything suitable is so necessary.

A fact is that when the direction is just like that, no more, longer, sudden and at the same time not any sofa, the main action is that without a blaming there is no custody.

Practice measurement, practice the sign that means that really means a necessary betrayal, in showing that there is wearing.

Hope, what is a spectacle, a spectacle is the resemblance between the circular side place and nothing else, nothing else.

To choose it is ended, it is actual and more than that it has it certainly has the same treat, and a seat all that is practiced and more easily much more easily ordinarily.

Pick a barn, a whole barn, and bend more slender accents than have ever been necessary, shine in the darkness necessarily. Actually not aching, actually not aching, a stubborn bloom is so artificial and even more than that, it is a spectacle, it is a binding accident, it is animosity and accentuation.

If the chance to dirty diminishing is necessary, if it is why is there no complexion, why is there no rubbing, why is there no special protection.

A FRIGHTFUL RELEASE.

A bag which was left and not only taken but turned away was not found. The place was shown to be very like the last time. A piece was not exchanged, not a bit of it, a piece was left over. The rest was mismanaged.

A PURSE.

A purse was not green, it was not straw color, it was hardly seen and it had a use a long use and the chain, the chain was never missing, it was not misplaced, it showed that it was open, that is all that it showed.

A MOUNTED UMBRELLA.

What was the use of not leaving it there where it would hang what was the use if there was no chance of ever seeing it come there and show that it was handsome and right in the way it showed it. The lesson is to learn that it does show it, that it shows it and that nothing, that there is nothing, that there is no more to do about it and just so much more is there plenty of reason for making an exchange.

A CLOTH.

Enough cloth is plenty and more, more is almost enough for that and besides if there is no more spreading is there plenty of room for it. Any occasion shows the best way.

MORE.

An elegant use of foliage and grace and a little piece of white cloth and oil.

Wondering so winningly in several kinds of oceans is the reason that makes red so regular and enthusiastic. The reason that there is more snips are the same shining very colored rid of no round color.

A NEW CUP AND SAUCER.

Enthusiastically hurting a clouded yellow bud and saucer, enthusiastically so is the bite in the ribbon.

OBJECTS.

Within, within the cut and slender joint alone, with sudden equals and no more than three, two in the centre make two one side.

If the elbow is long and it is filled so then the best example is all together.

The kind of show is made by squeezing.

Gertrude Stein Quotes to Perplex and Delight

EYE GLASSES.

A color in shaving, a saloon is well placed in the centre of an alley.

CUTLET.

A blind agitation is manly and uttermost.

CARELESS WATER.

No cup is broken in more places and mended, that is to say a plate is broken and mending does do that it shows that culture is Japanese. It shows the whole element of angels and orders. It does more to choosing and it does more to that ministering counting. It does, it does change in more water.

Supposing a single piece is a hair supposing more of them are orderly, does that show that strength, does that show that joint, does that show that balloon famously. Does it.

A PAPER.

A courteous occasion makes a paper show no such occasion and this makes readiness and eyesight and likeness and a stool.

A DRAWING.

The meaning of this is entirely and best to say the mark, best to say it best to show sudden places, best to make bitter, best to make the length tall and nothing broader, anything between the half.

WATER RAINING.

Water astonishing and difficult altogether makes a meadow and a stroke.

COLD CLIMATE.

A season in yellow sold extra strings makes lying places.

MALACHITE.

The sudden spoon is the same in no size. The sudden spoon is the wound in the decision.

AN UMBRELLA.

Coloring high means that the strange reason is in front not more in front behind. Not more in front in peace of the dot.

A PETTICOAT.

A light white, a disgrace, an ink spot, a rosy charm.

A WAIST.

A star glide, a single frantic sullenness, a single financial grass greediness.

Object that is in wood. Hold the pine, hold the dark, hold in the rush, make the bottom.

A piece of crystal. A change, in a change that is remarkable there is no reason to say that there was a time.

A woolen object gilded. A country climb is the best disgrace, a couple of practices any of them in order is so left.

A TIME TO EAT.

A pleasant simple habitual and tyrannical and authorised and educated and resumed and articulate separation. This is not tardy.

A LITTLE BIT OF A TUMBLER.

A shining indication of yellow consists in there having been more of the same color than could have been expected when all four were bought. This was the hope which made the six and seven have no use for any more places and this necessarily spread into nothing. Spread into nothing.

A FIRE.

What was the use of a whole time to send and not send if there was to be the kind of thing that made that come in. A letter was nicely sent.

A HANDKERCHIEF.

A winning of all the blessings, a sample not a sample because there is no worry.

RED ROSES.

A cool red rose and a pink cut pink, a collapse and a sold hole, a little less hot.

IN BETWEEN.

In between a place and candy is a narrow foot-path that shows more mounting than anything, so much really that a calling meaning a bolster measured a whole thing with that. A virgin a whole virgin is judged made and so between curves and outlines and real seasons and more out glasses and a perfectly unprecedented arrangement between old ladies and mild colds there is no satin wood shining.

COLORED HATS.

Colored hats are necessary to show that curls are worn by an addition of blank spaces, this makes the difference between single lines and broad stomachs, the least thing is lightening, the least thing means a little flower and a big delay a big delay that makes more nurses than little women really little women. So clean is a light that nearly all of it shows pearls and little ways. A large hat is tall and me and all custard whole.

A FEATHER.

A feather is trimmed, it is trimmed by the light and the bug and the post, it is trimmed by little leaning and by all sorts of mounted reserves and loud volumes. It is surely cohesive.

A BROWN.

A brown which is not liquid not more so is relaxed and yet there is a change, a news is pressing.

A LITTLE CALLED PAULINE.

A little called anything shows shudders.

Come and say what prints all day. A whole few watermelon. There is no pope.

No cut in pennies and little dressing and choose wide soles and little spats really little spices.

A little lace makes boils. This is not true.

Gracious of gracious and a stamp a blue green white bow a blue green lean, lean on the top.

If it is absurd then it is leadish and nearly set in where there is a tight head.

A peaceful life to arise her, noon and moon and moon. A letter a cold sleeve a blanket a shaving house and nearly the best and regular window.