Nava Atlas's Blog, page 80

September 24, 2018

9 Facts about Colette, Prolific and Passionate French Author

Colette (1873 – 1954), the French author (born Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette) was as known for her writing as for her scandalous love life in the course of her prolific career. Rejecting society’s rules for female expression and sexuality, she overcame notoriety to be regarded as one of the most treasured authors in the canon of French literature.

Colette was no angel and certainly had her flaws in a full life of great accomplishment as well as of scandal. But from mid-career on, and beyond her lifetime she’s consistently been recognized as one of France’s most notable literary figures. Even today, her rebellion against societal norms for women and owning of her sexuality would be admired as progressive. In her time, she was nothing short of radical!

A 2018 feature film, simply titled Colette, celebrates the author’s life and literature. Before you see this critically acclaimed film, which focuses on her early years as a writer, explore these fascinating facts about Colette to get to know her. Better yet, read her books, many of which have been translated into English. The most widely read include the Claudine series, as well as Gigi, The Vagabond, and Chéri.

Dominic West stars as Willy and Keira Knightley as Colette in Colette, a Bleecker Street release.

Credit: Robert Viglasky / Bleecker Street

Colette stars Keira Knightly as the author and features Dominic West as her nefarious first husband, Willy. It premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January of 2018 and was released in the U.S. in September 2018. It will be in wide release in the U.S. on October 12, and in the U.K. in January 2019.

The BBC said of this film: “She might have been born in the late 19th Century, but Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette is a heroine for our times: a fearless, creative woman who challenged the patriarchy in stuffy Parisian society, in supposedly liberal artistic circles, and in her own bedroom.” Watch the trailer here.

Her husband took credit for her early fiction

In 1900, Colette began publishing the semi-autobiographical series of Claudine stories that defined the era’s teenage girl, exploring her sexuality and unconventional ways. The problem: her first husband, the nefarious Willy (Henry Gauthier-Villars), took the credit as well as the earnings for these popular stories.

Claudine at School (1900) was the first of the efforts to be published and was an immediate success. More Claudine books followed. When Colette resisted Willy’s control, he locked her in a room and compelled her to write until she had produced enough pages for his liking.

Colette in her music hall years

She worked as a music hall performer

When Colette finally broke free of Willy in 1906, she had no access to the substantial earnings of the Claudine books, because her debauched husband held the copyrights. She struggled to make a living as music hall performer, all the while continuing to write fiction.

This was also the period in which she conducted a series of affairs with women. In 1907 she shared an onstage kiss with Mathilde de Morny (known as Missy), with whom she was in a relationship. The scene caused a near-riot, and though they continued their relationship for several years longer, they had to conduct it on the quiet.

She was a neglectful mother

Colette had her first and only child, a daughter, at age forty. The girl was named Colette but acquired the odd nickname Bel-Gazou (“beautiful babbling/chirping”). It has been widely acknowledged that Colette was an abominable, neglectful mother. She married her daughter’s father, Henry de Jouvenel, a journalist and politician, a union that faltered quickly.

She seduced her teenage stepson

At age forty-seven, Colette seduced her 16-year-old stepson Bertrand de Juvenel, which led to the 1924 divorce from his father. Though it has been conjectured that the affair was the basis of the novel Chéri, this wasn’t the case; rather, it inspired the novel Le Blé en Herbe (Green Wheat)

Interestingly, some years later Bertrand de Jouvenel had an affair with American war correspondent Martha Gellhorn from 1930 to 1934. It is believed that they would have married, but de Jouvenel’s wife refused to grant him a divorce.

Colette page on Amazon

Her work inspired two Hollywood films

The 1944 novel Gigi is a story of a French girl training to be a courtesan who falls in love with a wealthy gentleman. The stage play starred newcomer Audrey Hepburn and was adapted by Colette’s American friend and colleague Anita Loos. It was also made into a popular 1958 film with Leslie Caron in the title role. Chéri, the story of the love affair between a young gigolo and an older woman, inspired the 2009 film starring Michelle Pfeiffer.

You might also enjoy:

Classic Women Authors in Men’s Clothing

She was inspired by fellow French woman of letters George Sand

In many ways, Colette followed the footsteps of her fellow Frenchwoman, George Sand, whom she admired. Like Sand, Colette’s work addressed the vagaries of love, with its joys, complications, heartaches, and sensual pleasures. Colette was incredibly prolific, yet reflected on her countrywoman with envy and awe:

“How the devil did George Sand manage? That sturdy woman of letters found it possible to finish one novel and start another in the same hour. And she did not thereby lose either a lover or a puff of the narghile [hookah], not to mention a Story of My Life in twenty volumes…”

Like George Sand, Colette was adept at self-criticism: “Writing is often wasteful. If I counted the pages I’ve torn up, of how many volumes am I the author?” And like her literary predecessor, Colette enjoyed posing in men’s clothing.

Short and Sweet Quotes by Colette

She found true love at age fifty-two

At fifty-two, Colette embarked on a torrid affair with Maurice Goudeket, sixteen years her junior. Against all odds, their love blossomed into an enduring and affectionate relationship, the likes of which she had always longed for. Goudeket became Colette’s third husband.

When France fell to Nazi Germany during World War II, Goudeket, who was Jewish, was arrested in 1941 by the Gestapo. Through Colette’s intervention, he was released after a few months, but the prospect of another arrest (which incredibly, didn’t come to pass) caused her a great deal of anguish.

She was given a state funeral upon her death

In her later years, Colette suffered from arthritis and rarely left her Paris apartment. She was cared for by her husband, Maurice Goudeket. Upon her death in 1954, Colette was one of the world’s most renowned women of letters and was given a state funeral, the first for a woman in France.

Maison de Colette, Jardin. Photo: Nicolas Castets

Colette’s childhood home is now a museum

Colette moved residences at least 14 times in her lifetime, but the one for which she seemed to have the fondest memories for was her childhood home. There she was born to Sido, the strong and possessive mother who so inspired her. The house remained a vivid and much longed-for symbol of a lost paradise. Maison de Colette, located in the village of St.-Sauveur-en-Puisaye in northwest Burgundy, has been open to the public since May 2016.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 9 Facts about Colette, Prolific and Passionate French Author appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 20, 2018

Quotes from Emma by Jane Austen

Emma by Jane Austen (1775 – 1817) was first published in December 1815. Before she began the novel, Austen wrote, “I am going to take a heroine whom no one but myself will much like.” In the first sentence she introduces the main character as “Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich.” Emma is privileged and headstrong, greatly overestimating her matchmaking abilities, her imagination often leading her astray.

Emma was the last novel to be completed and published during Jane Austen’s life, as Persuasion, the last novel Austen wrote, was published posthumously. Emma has been adapted for several films, many television series, multiple stage plays, and has been the inspiration for several novels. Following are a collection of quotes from Emma, a novel that has been said to have “changed the face of fiction”:

“Silly things do cease to be silly if they are done by sensible people in an impudent way.”

“I may have lost my heart, but not my self-control. ”

“Business, you know, may bring money, but friendship hardly ever does.”

“Why not seize the pleasure at once? — How often is happiness destroyed by preparation, foolish preparation!”

“I am going to take a heroine whom no one but myself will much like.”

“Surprises are foolish things. The pleasure is not enhanced, and the inconvenience is often considerable.”

“Full many a flower is born to blush unseen,

And waste it’s fragrance on the desert air.”

“Nobody, who has not been in the interior of a family, can say what the difficulties of any individual of that family may be.”

You may also enjoy: The Biggest Myth About Jane Austen’s Writing Life

“The most incomprehensible thing in the world to a man, is a woman who rejects his offer of marriage!”

“Evil to some is always good to others.”

“Time will generally lessen the interest of every attachment not within the daily circle.”

“I would much rather have been merry than wise.”

“If things are going untowardly one month, they are sure to mend the next.”

“It is very difficult for the prosperous to be humble.”

“Were I to fall in love, indeed, it would be a different thing! but I have never been in love; it is not my way, or my nature; and I do not think I ever shall. And, without love, I am sure I should be a fool to change such a situation as mine.”

“Where the waters do agree, it is quite wonderful the relief they give.”

“I don’t approve of surprises. The pleasure is never enhanced and the inconvenience is considerable.”

“A man always imagines a woman to be ready for anybody who asks her.”

“A very narrow income has a tendency to contract the mind, and sour the temper. Those who can barely live, and who live perforce in a very small, and generally very inferior, society, may well be illiberal and cross.”

Emma by Jane Austen on Amazon

“Where the wound had been given, there must the cure be found, if any where.”

“The youth and cheerfulness of morning are in happy analogy, and of powerful operation; and if the distress be not poignant enough to keep the eyes unclosed, they will be sure to open to sensations of softened pain and brighter hope.”

“I do not know whether it ought to be so, but certainly silly things do cease to be silly if they are done by sensible people in an impudent way. Wickedness is always wickedness, but folly is not always folly.”

“Do not deceive yourself; do not be run away with by gratitude and compassion.”

“Every thing was to take its natural course, however, neither impelled nor assisted.”

“What is passable in youth is detestable in later age.”

“I must tell you what you will not ask, though I may wish it unsaid the next moment.”

“Letters are no matter of indifference; they are generally a very positive curse.”

“Fine dancing, I believe, like virtue, must be its own reward.”

“Vanity working on a weak head, produces every sort of mischief.”

“Time, you may be sure, will make one or the other of us think differently; and, in the meanwhile, we need not talk much on the subject.”

“Men never know when things are dirty or not.”

“The removal of one solicitude generally makes way for another.”

You may also enjoy: Memorable Jane Austen Quotes

“There are people who, the more you do for them, the less they will do for themselves.”

“You have another long walk before you.”

“It was impossible to quarrel with words, whose tremulous inequality showed indisposition so plainly.”

“The I examined my own heart. And there you were. Never, I fear, to be removed.”

“She had been a friend and companion such as few possessed: intelligent, well-informed, useful, gentle, knowing all the ways of the family, interested in all its concerns, and peculiarly interested in herself, in every pleasure, every scheme of hers–one to whom she could speak every thought as it arose, and who had such an affection for her as could never find fault.”

“Whenever you are transplanted, like me, you will understand how very delightful it is to meet with anything at all like what one has left behind.”

“Seldom, very seldom does complete truth belong to any human disclosure; seldom can it happen that something is not a little disguised, or a little mistaken; but where, as in this case, though the conduct is mistaken, the feelings are not, it may not be very material.”

“That is the case with us all, papa. One half of the world cannot understand the pleasures of the other.”

See also: Jane Austen Postage Stamps: 2013 & 1975

“I have observed…in the course of my life, that if things are going outwardly one month, they are sure to mend the next.”

“It may be possible to do without dancing entirely. Instances have been known of young people passing many, many months successively, without being at any ball of any description, and no material injury accrue either to body or mind.”

“Seldom, very seldom, does complete truth belong to any human disclosure; seldom can it happen that something is not a little disguised, or a little mistaken.”

“I always deserve the best treatment, because I never put up with any other.”

“It is very unfair to judge of any body’s conduct, without an intimate knowledge of their situation.”

“Where there is a wish to please, one ought to overlook, and one does overlook a great deal.”

“I always take the part of my own sex. I do indeed. I give you notice—You will find me a formidable antagonist on that point. I always stand up for women.”

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from Emma by Jane Austen appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 19, 2018

It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200 at The Morgan Library & Museum

It’s with great excitement that Literary Ladies Guide is helping to spread the news of a forthcoming exhibition at The Morgan Library & Museum (NYC): It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200, on display from October 12, 2018 to January 27, 2019. It’s hard to overstate the impact of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein on literature as well as popular culture. This exhibit celebrates the 200th anniversary of the 1818 classic, published when its author was barely twenty-one.

If you’re planning a trip to New York City this fall or early winter, we urge you to take the opportunity to see this exhibit as well as get to know The Morgan Library & Museum, a beautiful oasis in the heart of the city, located at 225 Madison Avenue. Learn more about the exhibit here, and note some of the programs and events, including films and gallery talks.

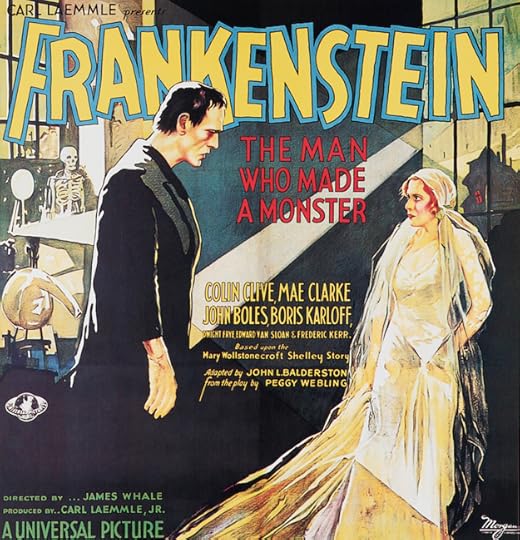

Image at upper right: Frankenstein, or, the Modern Prometheus, New York: Grosset and Dunlap, [1931]. Courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum and Universal Studios Licensing LLC, © 1931 Universal Pictures Company, Inc. Photograph by Janny Chiu.

The following information was provided by The Morgan Library and is reprinted with permission:

It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200

A classic of world literature, a masterpiece of horror, and a forerunner of science fiction, Frankenstein by Mary Shelley is the subject of a new exhibition at the Morgan. Organized in collaboration with the New York Public Library, It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200 traces the origins and impact of the novel whose monster has become both a meme and a metaphor for forbidden science, unintended consequences, and ghastly combinations of the human and the inhuman.

Portions of the original manuscript will be on display along with historic scientific instruments and iconic artwork such as Henry Fuseli’s Nightmare and the definitive portrait of Mary Shelley. The story’s astonishingly versatile role in art and culture over the course of two hundred years helps explain why the monster permeates the popular imagination to this day.

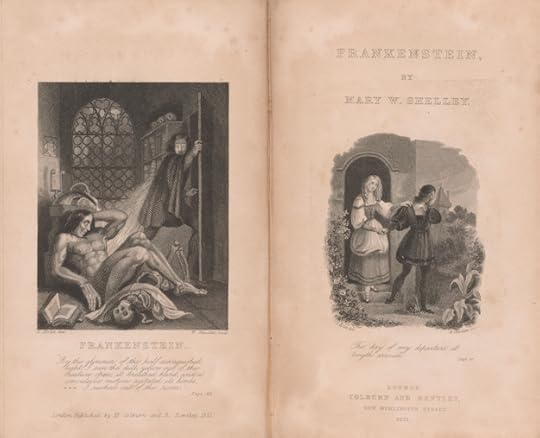

Frankenstein, or, The Modern Prometheus. London:

Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, 1831 edition.

Courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum. Photograph by Janny Chiu.

Co-curated by John Bidwell, the Astor Curator and Department Head of the Morgan’s Printed Books and Bindings Department, and Elizabeth Denlinger, Curator of the Carl H. Pforzheimer Press, this exhibition presents a diverse array of books, manuscripts, posters, prints, and paintings illustrating the long cultural tradition that shaped and was shaped by Mary Shelley’s myth. A large number of these works come from both the Morgan and the New York Public Library’s collections.

Only eighteen years old when she embarked on the novel, Shelley invented the archetype of the mad scientist who dares to flout the laws of nature. She created an iconic monster who spoke out against injustice and begged for sympathy while performing acts of shocking violence. The monster’s fame can be attributed to the novel’s theatrical and film adaptations. Comic books, film posters, publicity stills, and movie memorabilia reveal a different side to the story of Frankenstein, as reinterpreted in spinoffs, sequels, mashups, and parodies.

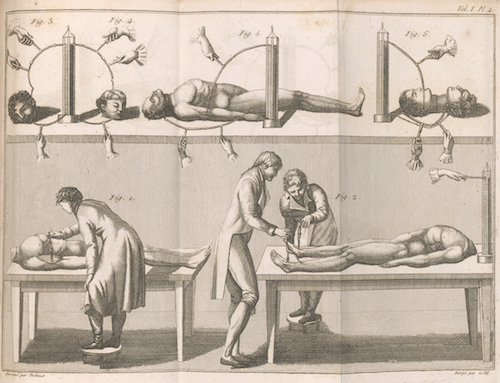

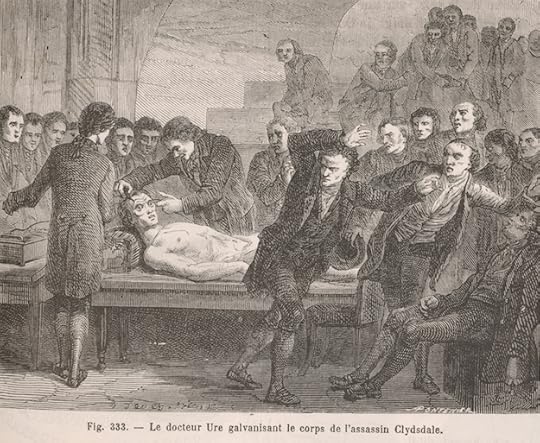

Benoît Pecheux, plate no. 4 in Giovanni Aldini, Essai théorique et expérimental sur le galvanisme,

Paris:

De l’imprimerie de Fournier Fils, 1804.

Courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum. Photograph by Janny Chiu.

“The Morgan is in an excellent position to tell the rich story of Mary Shelley’s life and of Frankenstein’s evolution in popular culture,” said director of the museum, Colin B. Bailey. “Pierpont Morgan was fascinated by the creative process, and one of the artifacts he acquired was a first edition Frankenstein annotated by the author. The collection of works by the Shelleys, both at the Morgan and the New York Public Library, has only grown since then. We are very pleased to collaborate with the NYPL in presenting the full version of this extraordinary tale and how it lives on in the most resilient and timely of ways.”

The exhibition occupies two galleries: one documenting the life of Mary Shelley and the composition of her book, the other showing how the story evolved in the theater, cinema, and popular culture.

Carl Laemmle Presents Frankenstein: the Man who Made a Monster, lithograph poster, 1931.

Collection of Stephen Fishler, comicconnect.com, Courtesy of Universal Studios Licensing LLC, © 1931

Universal Pictures Company, Inc.

The Influence of the Gothic Style and Enlightenment Science

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus sprang from both a passion for Gothic style that pervaded British culture long before the author’s birth in 1797 and the influence of the discoveries of European Enlightenment science. Audiences loved the supernatural in all its formulations—ghosts, graveyards, mysterious strangers, secret warnings, lost wills, hidden pictures, and more.

While novels were the primary vehicle for the Gothic, it was also popular with artists of paintings and prints, which were sometimes satirical —the Gothic was parodied as soon as it was taken seriously. The exhibition opens with the greatest horror painting of the eighteenth century, The Nightmare, painted in 1781 by the Swiss immigrant artist Henry Fuseli. Mary Shelley knew about this iconic image and may have used it in writing the climactic scene in Frankenstein.

Shelley was also influenced by the scientific endeavors of the time. She had been born into an age of scientific and technological discovery in Britain, when institutions like the Royal Society began fostering exploration and experimentation. Across Britain spread a thriving circuit of lectures and science demonstrations for the public.

A few of these experiments have become part of the Frankenstein legend. While writing the novel, Shelley had been reading Humphry Davy’s Elements of Chemical Philosophy, and she knew about anatomical dissections, contemporary debates about the origins of life, and electrical experiments on corpses. She lends this fascination to Victor Frankenstein, who makes a monster from corpses in his “workshop of filthy creation.”

Benoît Pecheux, plate no. 4 in Giovanni Aldini, Essai théorique et expérimental sur le galvanisme,

Paris: De l’imprimerie de Fournier Fils, 1804. Courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum.

Photography by Janny Chiu.

Publication

A copiously illustrated companion volume, It’s Alive! A Visual History of Frankenstein, provides a vivid account of the artistic and literary legacy of the novel along with detailed descriptions of the highlights in the exhibition, while a new online curriculum offers high school teachers resources for the classroom.

It’s Alive! A Visual History of Frankenstein delves into the artistic and literary legacy of the novel and provides detailed descriptions of the highlights in the exhibition. It introduces readers to portrayals of the creature — from his early days dancing across a stage, to Boris Karloff’s lurching pathos, to the wide variety of modern-day comic book versions — and of Victor Frankenstein, from brainy college kid to bad scientist, and grounds them in historical context. In addition, it provides full introductions to Mary Shelley’s life before and after the novel and to the pioneering scientific work of her day.

A full chapter displays the Gothic paintings and graphic art that inspired Shelley’s work. The contextual chapters will make it useful to the student and the general reader. Author: Elizabeth Campbell Denlinger Publisher: The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; D Giles Limited, London. 333 pages.

Read the rest of the exhibition notes, including a listing of events and public programs, here.

Jean-François Vilain,Théâtre de la Porte St. Martin, Le monstre, acte premier, scène dernière, ca. 1826,

color lithograph.

Département des Arts du spectacle—Bibliothèque nationale de France.

More information on Mary Shelley and Frankenstein

Brief biography of Mary Shelley

A 19th-Century view and synopsis of Frankenstein

How Mary Shelley Came to Write Frankenstein (1818)

The post It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200 at The Morgan Library & Museum appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 15, 2018

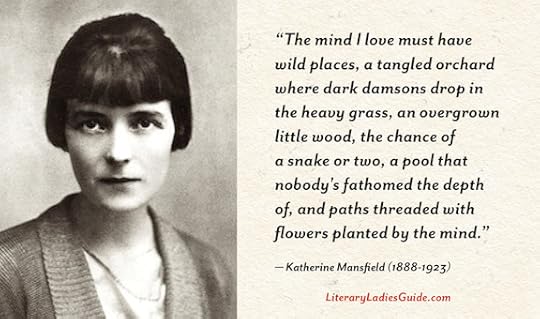

Katherine Mansfield

Katherine Mansfield (October 14, 1888 – January 9, 1923), best known for her mastery of the short story form, was born in Wellington, New Zealand as Katherine Mansfield Beauchamp. She’s recognized for revolutionizing the modern English short story.

She enjoyed a comfortable childhood as part of a well-to-do family. A serious student of the cello, she first expected that music would be her career. Still, she found the colonial Edwardian atmosphere stifling and was inspired by rebels like Oscar Wilde. According to her biography, Katherine Mansfield: A Life by Antony Alpers, “she gave early evidence of the impulsiveness, the intensity, the impatience with convention which she would pour into her later life.”

Her pretention of grandeur are reflected in this odd quote: “I like to appear in any society – entirely at my ease – conscious of my own importance, which in my estimation is unlimited, affable and very receptive. I like to appear slightly condescending, very much of le grand monde.“

A new life in Europe

Rejecting her bourgeois background, she moved to London in 1903 to attend Queens College. There, influenced by the heady literary scenes of the emerging Bloomsbury circle and others, she began writing in earnest, determined to make a name for herself.

New Zealand felt alienating to her upon returning from her studies. Reflecting on that time she later wrote to a friend in a 1922 letter:

“I am a ‘Colonial.’ I was born in New Zealand, I came to Europe to ‘complete my education’ and when my parents thought that tremendous task was over I went back to New Zealand. I hated it. It seemed to me a small petty world; I longed for ‘my’ kind of people and larger interests and so on. And after a struggle I did get out of the nest finally and came to London, at eighteen, never to return, said my disgusted heart.”

Exploring the short story form

In 1908, firmly ensconced in the bohemian life in London, she began writing short stories. Her first collection was published in 1911 and reflected a certain disillusionment with her native country. Titled In a German Pension, it received favorable reviews and was praised for “acute insight” and “unquenchable humour.”

She went on to contribute stories to Rhythm, an avant-garde literary publication. with her partner and husband-to-be, literary critic John Middleton Murray.

Mansfield’s younger brother Leslie, a World War I soldier, was killed in 1915. This devastated her. She found some solace in redirecting her grief into a kind of emotional debt to his memory, and to the shared experiences in their native land of New Zealand. The short stories in Prelude (1918) that evoked these memories tenderly.

The 1920 collection Bliss and Other Stories (1920) followed by The Garden Party and Other Stories (1922) sealed her reputation as a master of the short story form. The Dove’s Nest and Other Stories (1923) and Something Childish (1924) were published after Mansfield’s untimely death.

Some of her most highly regarded stories include “At the Bay,” “The Voyage,” “The Stranger,” and “Daughters of the Late Colonel.”

See also 7 Gutsy Quotes by Katherine Mansfield

Many lovers and tortured relationships

In her brief life, Mansfield had a great many lovers, both male and female; her bisexuality was known to her from adolescence. Her relationship with a childhood friend, Garnet Trowell, when both were twenty, resulted in a pregnancy that she miscarried.

Mansfield had a somewhat tormented friendship with fellow author D.H. Lawrence, who used her as the model for Gudrun in Women in Love. Famously, she had a disastrous one-day marriage to George Bowden.

Her most tumultuous relationship was with the man with whom she had a long love affair and then married, John Middleton Murry, whom she met in his capacity as an editor of a magazine to which she submitted work. Though their relationship began in 1912, she was unable to marry him until 1918, when she finally obtained a divorce from her first husband.

Friend and rival of Virginia Woolf

An odd rivalry percolated between her and Virginia Woolf, who said of Mansfield, “I was jealous of her writing. The only writing I have ever been jealous of.” On the other hand Woolf wrote, “The more she is praised, the more I am convinced she is bad.” However, though Mansfield and Woolf have long been painted as bitter rivals, they were actually quite close as friends and as writing colleagues.

You might also like Bliss by Katherine Mansfield (1918) – full text

An untimely death

Katherine Mansfield was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1917 but continued to write on a daily basis until she could no longer do so by 1922. Fighting mightily to combat her illness, she entered the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man in France.

Sadly she died there three months later, in 1923, at the age of 34. Before her tragic death from tuberculosis in 1923. Toward the end of her life, she searched for truth in the “spiritual discipline” teachings of the Russian mystic G. I. Gurdjieff.

Legacy

Even though her career was cut short at a young age, it’s widely accepted that Mansfield revolutionized the English short story. According to The Penguin Companion to English Literature:

“The quiet clarity of detail, the symbolic use of objects and incidents presented with extraordinary physical accuracy, the cunning distillation of atmosphere, are the outstanding features of her stories, which have something in common with those of Chekhov.”

Her legacy is summed up on the official Katherine Mansfield site: “She was a writer of short stories, poetry, letters, journals, and reviews, and changed the way the short story was written in the English language. She was a rebel and a modernist who lived her short life of 34 years to the full. Her life spanned a time when gender roles for women underwent a radical change. Katherine Mansfield was among an emerging female professional class and saw herself as a writer first, a woman second.”

In the late 1920s, her husband John Middleton Murry edited collections from her journals and letters.

Katherine Mansfield page on Amazon

More about Katherine Mansfield on this site

7 Gutsy Quotes on Life’s Challenges

Courageous Quotes by Katherine Mansfield

Bliss by Katherine Mansfield (1918) – full text

Major Works

In a German Pension

Something Childish But Very Natural

The Garden Party & Other Stories

Mansfield Notebooks: Complete Edition

The Collected Stories

Bliss and Other Stories

Biographies about Katherine Mansfield

Katherine Mansfield: A Darker View by Jeffrey Myers

Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life by Claire Tomalin

Katherine Mansfield: The Story-teller by Kathleen Jones

Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf by Angela Smith

More Information

Wikipedia

The Katherine Mansfield Society

New Zealand Cook Council

Adventures in Feministory

Visit

Katherine Mansfield House and Garden – Wellington, New Zealand

Inventory of the Mansfield Papers 1903-1942 –

The Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Katherine Mansfield appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 14, 2018

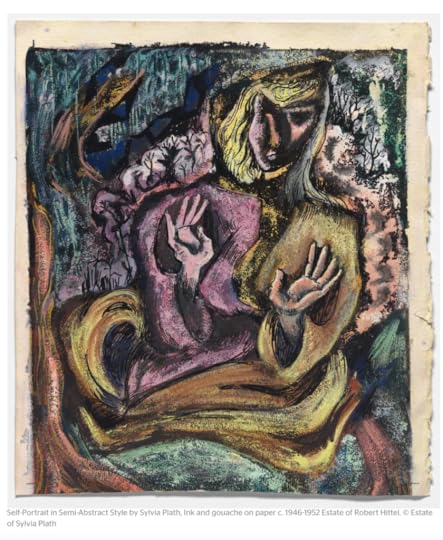

10 Poems by Anne Sexton, Confessional Poet

Anne Sexton (1928 – 1974) proclaimed that she was “the only confessional poet” some time before committing suicide at the age of forty-five. Her good friend Sylvia Plath, whose poetry stands squarely in the realm of the confessional movement, might have taken issue with that. But it’s undoubtedly true that from the time she started writing poetry as a way to recover from a mental breakdown, her writing and her inner life were joined.

From that synergy emerged a period of wild creativity that resulted in more than a dozen collections and a Pulitzer Prize. Here’s a sampling of 10 poems by Anne Sexton, a woman who was as complex and talented an artist and woman as they come.

45 Mercy Street

In my dream,

drilling into the marrow

of my entire bone,

my real dream,

I’m walking up and down Beacon Hill

searching for a street sign –

namely MERCY STREET.

Not there.

I try the Back Bay.

Not there.

Not there.

And yet I know the number.

45 Mercy Street.

I know the stained-glass window

of the foyer,

the three flights of the house

with its parquet floors.

I know the furniture and

mother, grandmother, great-grandmother,

the servants.

I know the cupboard of Spode

the boat of ice, solid silver,

where the butter sits in neat squares

like strange giant’s teeth

on the big mahogany table.

I know it well.

Not there.

Where did you go?

45 Mercy Street,

with great-grandmother

kneeling in her whale-bone corset

and praying gently but fiercely

to the wash basin,

at five A.M.

at noon

dozing in her wiggy rocker,

grandfather taking a nap in the pantry,

grandmother pushing the bell for the downstairs maid,

and Nana rocking Mother with an oversized flower

on her forehead to cover the curl

of when she was good and when she was…

And where she was begat

and in a generation

the third she will beget,

me,

with the stranger’s seed blooming

into the flower called Horrid.

I walk in a yellow dress

and a white pocketbook stuffed with cigarettes,

enough pills, my wallet, my keys,

and being twenty-eight, or is it forty-five?

I walk. I walk.

I hold matches at street signs

for it is dark,

as dark as the leathery dead

and I have lost my green Ford,

my house in the suburbs,

two little kids

sucked up like pollen by the bee in me

and a husband

who has wiped off his eyes

in order not to see my inside out

and I am walking and looking

and this is no dream

just my oily life

where the people are alibis

and the street is unfindable for an

entire lifetime.

Pull the shades down –

I don’t care!

Bolt the door, mercy,

erase the number,

rip down the street sign,

what can it matter,

what can it matter to this cheapskate

who wants to own the past

that went out on a dead ship

and left me only with paper?

Not there.

I open my pocketbook,

as women do,

and fish swim back and forth

between the dollars and the lipstick.

I pick them out,

one by one

and throw them at the street signs,

and shoot my pocketbook

into the Charles River.

Next I pull the dream off

and slam into the cement wall

of the clumsy calendar

I live in,

my life,

and its hauled up

notebooks.

A Cruse Against Elegies

Oh, love, why do we argue like this?

I am tired of all your pious talk.

Also, I am tired of all the dead.

They refuse to listen,

so leave them alone.

Take your foot out of the graveyard,

they are busy being dead.

Everyone was always to blame:

the last empty fifth of booze,

the rusty nails and chicken feathers

that stuck in the mud on the back doorstep,

the worms that lived under the cat’s ear

and the thin-lipped preacher

who refused to call

except once on a flea-ridden day

when he came scuffing in through the yard

looking for a scapegoat.

I hid in the kitchen under the ragbag.

I refuse to remember the dead.

And the dead are bored with the whole thing.

But you – you go ahead,

go on, go on back down

into the graveyard,

lie down where you think their faces are;

talk back to your old bad dreams.

Anne Sexton page on Amazon

Again And Again And Again

You said the anger would come back

just as the love did.

I have a black look I do not

like. It is a mask I try on.

I migrate toward it and its frog

sits on my lips and defecates.

It is old. It is also a pauper.

I have tried to keep it on a diet.

I give it no unction.

There is a good look that I wear

like a blood clot. I have

sewn it over my left breast.

I have made a vocation of it.

Lust has taken plant in it

and I have placed you and your

child at its milk tip.

Oh the blackness is murderous

and the milk tip is brimming

and each machine is working

and I will kiss you when

I cut up one dozen new men

and you will die somewhat,

again and again.

Menstruation at Forty

I was thinking of a son.

The womb is not a clock

nor a bell tolling,

but in the eleventh month of its life

I feel the November

of the body as well as of the calendar.

In two days it will be my birthday

and as always the earth is done with its harvest.

This time I hunt for death,

the night I lean toward,

the night I want.

Well then–

It was in the womb all along.

I was thinking of a son …

You! The never acquired,

the never seeded or unfastened,

you of the genitals I feared,

the stalk and the puppy’s breath.

Will I give you my eyes or his?

Will you be the David or the Susan?

(Those two names I picked and listened for.)

Can you be the man your fathers are–

the leg muscles from Michelangelo,

hands from Yugoslavia

somewhere the peasant, Slavic and determined,

somewhere the survivor bulging with life–

and could it still be possible,

all this with Susan’s eyes?

All this without you–

two days gone in blood.

I myself will die without baptism,

a third daughter they didn’t bother.

My death will come on my name day.

What’s wrong with the name day?

It’s only an angel of the sun.

Woman,

weaving a web over your own,

a thin and tangled poison.

Scorpio,

bad spider–

die!

My death from the wrists,

two name tags,

blood worn like a corsage

to bloom

one on the left and one on the right–

It’s a warm room,

the place of the blood.

Leave the door open on its hinges!

Two days for your death

and two days until mine.

Love! That red disease–

year after year, David, you would make me wild!

David! Susan! David! David!

full and disheveled, hissing into the night,

never growing old,

waiting always for you on the porch …

year after year,

my carrot, my cabbage,

I would have possessed you before all women,

calling your name,

calling you mine.

Love Letter Written In A Burning Building

I am in a crate, the crate that was ours,

full of white shirts and salad greens,

the icebox knocking at our delectable knocks,

and I wore movies in my eyes,

and you wore eggs in your tunnel,

and we played sheets, sheets, sheets

all day, even in the bathtub like lunatics.

But today I set the bed afire

and smoke is filling the room,

it is getting hot enough for the walls to melt,

and the icebox, a gluey white tooth.

I have on a mask in order to write my last words,

and they are just for you, and I will place them

in the icebox saved for vodka and tomatoes,

and perhaps they will last.

The dog will not. Her spots will fall off.

The old letters will melt into a black bee.

The night gowns are already shredding

into paper, the yellow, the red, the purple.

The bed — well, the sheets have turned to gold —

hard, hard gold, and the mattress

is being kissed into a stone.

As for me, my dearest Foxxy,

my poems to you may or may not reach the icebox

and its hopeful eternity,

for isn’t yours enough?

The one where you name

my name right out in P.R.?

If my toes weren’t yielding to pitch

I’d tell the whole story —

not just the sheet story

but the belly-button story,

the pried-eyelid story,

the whiskey-sour-of-the-nipple story —

and shovel back our love where it belonged.

Despite my asbestos gloves,

the cough is filling me with black and a red powder seeps through my

veins,

our little crate goes down so publicly

and without meaning it, you see, meaning a solo act,

a cremation of the love,

but instead we seem to be going down right in the middle of a Russian

street,

the flames making the sound of

the horse being beaten and beaten,

the whip is adoring its human triumph

while the flies wait, blow by blow,

straight from United Fruit, Inc.

More Than Myself

Not that it was beautiful,

but that, in the end, there was

a certain sense of order there;

something worth learning

in that narrow diary of my mind,

in the commonplaces of the asylum

where the cracked mirror

or my own selfish death

outstared me . . .

I tapped my own head;

it was glass, an inverted bowl.

It’s small thing

to rage inside your own bowl.

At first it was private.

Then it was more than myself.

The Fury Of Sunsets

Something

cold is in the air,

an aura of ice

and phlegm.

All day I’ve built

a lifetime and now

the sun sinks to

undo it.

The horizon bleeds

and sucks its thumb.

The little red thumb

goes out of sight.

And I wonder about

this lifetime with myself,

this dream I’m living.

I could eat the sky

like an apple

but I’d rather

ask the first star:

why am I here?

why do I live in this house?

who’s responsible?

eh?

Cinderella

You always read about it:

the plumber with twelve children

who wins the Irish Sweepstakes.

From toilets to riches.

That story.

Or the nursemaid,

some luscious sweet from Denmark

who captures the oldest son’s heart.

From diapers to Dior.

That story.

Or a milkman who serves the wealthy,

eggs, cream, butter, yogurt, milk,

the white truck like an ambulance

who goes into real estate

and makes a pile.

From homogenized to martinis at lunch.

Or the charwoman

who is on the bus when it cracks up

and collects enough from the insurance.

From mops to Bonwit Teller.

That story.

Once

the wife of a rich man was on her deathbed

and she said to her daughter Cinderella:

Be devout. Be good. Then I will smile

down from heaven in the seam of a cloud.

The man took another wife who had

two daughters, pretty enough

but with hearts like blackjacks.

Cinderella was their maid.

She slept on the sooty hearth each night

and walked around looking like Al Jolson.

Her father brought presents home from town,

jewels and gowns for the other women

but the twig of a tree for Cinderella.

She planted that twig on her mother’s grave

and it grew to a tree where a white dove sat.

Whenever she wished for anything the dove

would drop it like an egg upon the ground.

The bird is important, my dears, so heed him.

Next came the ball, as you all know.

It was a marriage market.

The prince was looking for a wife.

All but Cinderella were preparing

and gussying up for the big event.

Cinderella begged to go too.

Her stepmother threw a dish of lentils

into the cinders and said: Pick them

up in an hour and you shall go.

The white dove brought all his friends;

all the warm wings of the fatherland came,

and picked up the lentils in a jiffy.

No, Cinderella, said the stepmother,

you have no clothes and cannot dance.

That’s the way with stepmothers.

Cinderella went to the tree at the grave

and cried forth like a gospel singer:

Mama! Mama! My turtledove,

send me to the prince’s ball!

The bird dropped down a golden dress

and delicate little gold slippers.

Rather a large package for a simple bird.

So she went. Which is no surprise.

Her stepmother and sisters didn’t

recognize her without her cinder face

and the prince took her hand on the spot

and danced with no other the whole day.

As nightfall came she thought she’d better

get home. The prince walked her home

and she disappeared into the pigeon house

and although the prince took an axe and broke

it open she was gone. Back to her cinders.

These events repeated themselves for three days.

However on the third day the prince

covered the palace steps with cobbler’s wax

and Cinderella’s gold shoe stuck upon it.

Now he would find whom the shoe fit

and find his strange dancing girl for keeps.

He went to their house and the two sisters

were delighted because they had lovely feet.

The eldest went into a room to try the slipper on

but her big toe got in the way so she simply

sliced it off and put on the slipper.

The prince rode away with her until the white dove

told him to look at the blood pouring forth.

That is the way with amputations.

The don’t just heal up like a wish.

The other sister cut off her heel

but the blood told as blood will.

The prince was getting tired.

He began to feel like a shoe salesman.

But he gave it one last try.

This time Cinderella fit into the shoe

like a love letter into its envelope.

At the wedding ceremony

the two sisters came to curry favor

and the white dove pecked their eyes out.

Two hollow spots were left

like soup spoons.

Cinderella and the prince

lived, they say, happily ever after,

like two dolls in a museum case

never bothered by diapers or dust,

never arguing over the timing of an egg,

never telling the same story twice,

never getting a middle-aged spread,

their darling smiles pasted on for eternity.

Regular Bobbsey Twins.

That story.

Barefoot

Loving me with my shoes off

means loving my long brown legs,

sweet dears, as good as spoons;

and my feet, those two children

let out to play naked. Intricate nubs,

my toes. No longer bound.

And what’s more, see toenails and

all ten stages, root by root.

All spirited and wild, this little

piggy went to market and this little piggy

stayed. Long brown legs and long brown toes.

Further up, my darling, the woman

is calling her secrets, little houses,

little tongues that tell you.

There is no one else but us

in this house on the land spit.

The sea wears a bell in its navel.

And I’m your barefoot wench for a

whole week. Do you care for salami?

No. You’d rather not have a scotch?

No. You don’t really drink. You do

drink me. The gulls kill fish,

crying out like three-year-olds.

The surf’s a narcotic, calling out,

I am, I am, I am

all night long. Barefoot,

I drum up and down your back.

In the morning I run from door to door

of the cabin playing chase me.

Now you grab me by the ankles.

Now you work your way up the legs

and come to pierce me at my hunger mark.

Red Roses

Tommy is three and when he’s bad

his mother dances with him.

She puts on the record,

“Red Roses for a Blue Lady”

and throws him across the room.

Mind you,

she never laid a hand on him.

He gets red roses in different places,

the head, that time he was as sleepy as a river,

the back, that time he was a broken scarecrow,

the arm like a diamond had bitten it,

the leg, twisted like a licorice stick,

all the dance they did together,

Blue Lady and Tommy.

You fell, she said, just remember you fell.

I fell, is all he told the doctors

in the big hospital. A nice lady came

and asked him questions but because

he didn’t want to be sent away he said, I fell.

He never said anything else although he could talk fine.

He never told about the music

or how she’d sing and shout

holding him up and throwing him.

He pretends he is her ball.

He tries to fold up and bounce

but he squashes like fruit.

For he loves Blue Lady and the spots

of red roses he gives her.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 10 Poems by Anne Sexton, Confessional Poet appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 13, 2018

How Betty Smith Came to Write A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, in Her Own Words

How many of us have read and re-read and re-read A Tree Grows in Brooklyn? It’s one of those books that can be revisited at various stages in life and seen from a different perspective each time. Granted, none of Smith’s other three novels achieved quite the same success as A Tree, but they share the unifying themes of struggles in an urban setting, and above all, family bonds. It’s always fascinating to learn how an author came to write a book that has become a beloved classic, especially in their own words, and in the 1943 essay that follows describes how Betty Smith came to write A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.

After years of struggling to be a successful writer (she had already achieved a measure of success as a playwright), Betty Smith struck literary gold with A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.

This coming of age novel set in early 1900s Brooklyn is seen from the perspective of Francie Nolan, a down-to-earth girl who’s neither the kind of genius or beautiful heroine that are favored in novels. She possesses a more relatable kind of awkwardness, but her quiet courage in the face of poverty and other obstacles can’t be overlooked. Members of Francie’s immediate and extended family populate this novel with complex, sympathetic characterizations. About the tree that inspired the title:

“For Betty Wehner … the tree that grew outside her bedroom window was much more than merely a sight for sore eyes. It was an ailanthus, a hardy variety of Chinese sumac renowned for its tenacity. It flourishes best, a New York poet once remarked, amid ‘dead vine leaves, a cigarette butt, and a paper clip.’ Young Betty, herself a budding poet, sa the tree as a symbol of survival, a living reminder of her own struggle to escape the pain and poverty of Williamsburg.” (from the introduction to the 1989 edition)

The following essay was adapted from “How the Tree Grew” by Betty Smith, © 1943:

Explaining over pale tea

When people ask me how I came to write A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, my answer depends on the kind of refreshment I’m having at the moment. If the place is a crowded living room filled with hatted and gloved ladies and I’m holding a cup of pale tea in one hand and trying to hold a baby sandwich, napkin, petit four, and a cigarette in the other hand, I reply this way:

“I read so many stories and novels whose locale is claimed as Brooklyn. All were disappointing because they were about a city I didn’t recognize — a place whose inhabitants were too glibly characterized by their penchant for saying ‘skoit,’ ‘goil,’ and ‘erl boiner.’ It came to me that Brooklyn is not a city. It is a faith. You have to be born a Brooklynite; you cannot become one.

Brooklyn is town of dark mystery and violent passes and gentle ways. There are astonishing customs and rituals of living hidden away from the outsider. Well, I am a Brooklynite. I know of these hidden things. One day I went out and bought a ream of paper and started to write a novel about my city.” That’s my story over teacups.

In a college drugstore over milkshakes

Crowded in a student-filled booth in Chapel Hill’s college drugstore, drinking a chocolate milkshake out of a jumbo paper cup, and taking part in the violent pro and con talk about the merits of the writing of Carolina’s most famous literary alumnus, Thomas Wolfe, I answer the question this way:

“I wrote this novel because I’m a Tom Wolfe in reverse. You see, he was born in North Carolina, was a member of the Carolina Playmakers, studied playwriting with George P. Baker, and finally went to live in Brooklyn to write a novel about North Carolina. Now I was born in Brooklyn. I studied playwriting with George P. Baker, I became a member of the Carolina Playmakers, and finally went to North Carolina to write a novel about Brooklyn.” That’s my milkshake version.

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith on Amazon

Over coffee with Mama

I remember a further back origin when I sit with my mother in the cool kitchen of her Brooklyn home and we share a pot of midnight coffee together.

“It started when I was eight years old. I was playing in one of those Brooklyn streets one sunny afternoon and I saw a group of right-minded housewives throw stones at a mother who wasn’t married. I grew up wanting to protest in some way against intolerance. So you see, Mama, the beginning of this novel really started when, as a child, I began to notice the world of Brooklyn around me.”

And so it has been with me in all the years since I went away from Brooklyn. The pictures kept coming, tumbling over each other like eager acrobats, and they made a staggering pyramid of remembrances that grew higher with the years and threatened to topple over and bury me alive if I didn’t get them written down. And in the writing of the book my great problem was not what to set down but which of the myriad things to leave out.

And that’s how this novel grew to be written.

You might also like: Memorable Quotes from A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

More about A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

Betty Smith’s “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn” on the Screen

Books by Betty Smith: A Tree Grows in Brooklyn and More

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (article on 1945 film)

The Tree Still Grows in Brooklyn (1999 New York Times article)

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post How Betty Smith Came to Write A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, in Her Own Words appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 9, 2018

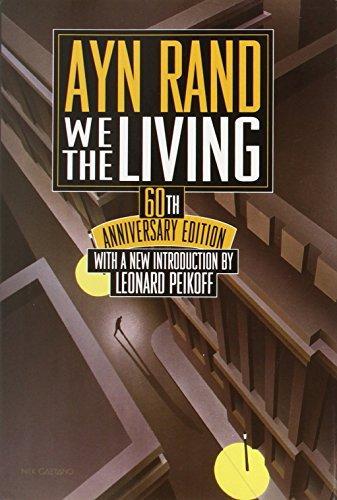

We the Living by Ayn Rand (1936)

We the Living (1936) was the first published novel by Ayn Rand, the ever-controversial Russian-American novelist. Set in post-revolutionary Russia, it reflected Rand’s opposition to communism and totalitarianism. It was, in her own estimation, her most semi-autobiographical. Though the reviews the book received upon its initial publication were mixed, it became a bestseller. This set the stage for the popularity of her subsequent novels, especially The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, which sold like gangbusters — even though critics were even less kind to them.

Many reviews of We the Living appreciated the direct look at the effects of Soviet policies on society, but felt the writing was heavy-handed. As the New York Times put it, the book seemed “slavishly warped to the dictates of propaganda.”

A new author just becoming known

When We the Living was published, Rand was already becoming known in certain quarters. Her play, Night of January 16th, had opened on Broadway the previous year. Like the books she would subsequently write, it was a critique of social conformity and a paean to individualism.

We the Living is the story of an aristocratic Russian family who returns to Petrograd in 1920, now under the Soviet regime, and their efforts to adapt to conditions of revolutionary society. Kira Agunova wishes to fight for keeping her individuality in tandem with this quest, takes two very different men as lovers. Intrigue, jealousy, and a critical look at Soviet politics keep the story moving along.

According to the Ayn Rand institute: “Ayn Rand’s theme in We the Living is the supreme value of an individual life, and the evil of a state that claims the right to take and sacrifice that life.

Rand held that each individual has a moral right to live for his own sake, to pursue his own personal happiness. Although they each passionately want to live, Kira and Leo cannot live a human life because they are trapped in a society that refuses to recognize or respect that right by leaving them free … Stated more simply, then, the main theme of We the Living is: the Individual against the State.

Here’s a generally objective review of We the Living that appeared when the book first came out in 1936:

Passionate, Powerful Novel About Russia

From the original review of We the Living by Ayn Rand in the Charleston Daily Mail, April 26, 1936: The story of We the Living by Ayn Rand has come out of Soviet Russia. It could have been written only by one who had lived intimately the life of the communist regime. It could have been published only after an escape from that life had made it possible for the author to write as she pleased.

The book is primarily a wild cry for the right of the individual to “live for what he wants to live for.” And secondarily, an indictment of the Soviets. It is wholly credible on the first score — somewhat less so, on the second. “We’re working for humanity,” cries one side. “The individual doesn’t matter.”

“If you must work for humanity,” cries the other, “that’s your business. I want to live for myself — for the something sacred and untouchable within me that makes me myself. Who gave you the right to forbid it?”

Miss Rand presents a question in terms of a dramatic novel, whose almost six hundred pages you’re likely to devour at a gulp. “Are you prepared to give up all the pleasures of modern Western culture … to work for the welfare of other people’s grandchildren in a world you will never see?”

“Decidedly no,” he answered. He could choose for himself. Kira Argunova couldn’t.

We the Living by Ayn Rand on Amazon

A return to Petrograd

In 1922, when the struggle between the Whites and Reds had ended, Kira returned to Petrograd from Crimea, where her family had fled four years earlier to wait for the brief annoyance of the Revolution to blow over. Her father, mother, and elder sister Lydia were returning in a state of apathetic resignation.

Revolution, poverty, hunger, had no effect on the flame that burned within Kira, age eighteen, with her passion for truth and life — her own life. She was going to be an engineer, because “it’s the only profession where I don’t have to learn a single lie.” She was going to build — not for the Red State, but because she wanted to build. All she asked was to be allowed to study.

Yet something happened, not to dim, but to divert her purpose. She fell in love with Leo and brought to her love all the ardor and constancy of her spirit. Nothing mattered in the face of the needs of the bitter, imperious man who became for her the center of existence. To him she sacrificed her work, her integrity, and her friend, Andrei Taganov, a far finer person.

See also Atlas Shrugged: Two Snarky Reviews

Andrei’s flame — dedicated to the cause of Communism — burned as purely as her own. The result for all three — Leo, who was too contemptuous to fight Andrei, who fought until betrayal robbed life of its meaning, and Kira, who kept on fighting to the end — was inevitably tragic.

The story moves at a swift pace in a series of graphic vignettes and is told with a kind of subdued fire and intensity that breaks into a blaze toward the end. Kira flings her defiance of Andrei and all he represents into his face. People and places come to life. Moods and sensations and atmosphere are evoked, so that you feel the gnawing of hunger, the agony of standing endlessly in line for the chance of a few scraps of food, the sick revulsion against life without privacy or cleanliness, the haunting dread of spies, the frenzied instances to fight free of the net closing in, the rebellion that beats its head out against stone walls and ends in lethargy or compromise or corruption or death.

More about We the Living by Ayn Rand

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

We the Living film adaptation

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post We the Living by Ayn Rand (1936) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 3, 2018

Bliss by Katherine Mansfield (1918) – Full Text

Bliss (1918) is a short story by Katherine Mansfield (1888 – 1923), the New Zealand-born British author recognized for revolutionizing the modern English short story form. Bliss is one of the works that put her on the literary map. Bertha Young, the main character, is a happy yet somewhat naïve young wife. The story takes place during a dinner party she hosts with her husband Harry.

One of the story’s themes is the classic one self-knowledge. But it was more of a rarity to explore queer themes in early twentieth-century literature. Mansfield herself was bisexual, and perhaps that was subtly alluded to with the character of Pearl Fulton, a guest to whom Bertha is drawn. However, Bertha is shaken out of her blissful state when she learns that her husband is having an affair with Pearl. Indeed, ignorance is bliss. This short story, which is in the public domain, is reprinted here in full.

Courageous Quotes by Katherine Mansfield

Bliss by Katherine Mansfield

Although Bertha Young was thirty she still had moments like this when she wanted to run instead of walk, to take dancing steps on and off the pavement, to bowl a hoop, to throw something up in the air and catch it again, or to stand still and laugh at — nothing —at nothing, simply.

What can you do if you are thirty and, turning the corner of your own street, you are overcome, suddenly by a feeling of bliss —absolute bliss! — as though you’d suddenly swallowed a bright piece of that late afternoon sun and it burned in your bosom, sending out a little shower of sparks into every particle, into every finger and toe? …

Oh, is there no way you can express it without being “drunk and disorderly”? How idiotic civilisation is! Why be given a body if you have to keep it shut up in a case like a rare, rare fiddle?

“No, that about the fiddle is not quite what I mean,” she thought, running up the steps and feeling in her bag for the key–she’d forgotten it, as usual–and rattling the letter-box. “It’s not what I mean, because — Thank you, Mary” — she went into the hall. “Is nurse back?”

“Yes, M’m.”

“And has the fruit come?”

“Yes, M’m. Everything’s come.”

“Bring the fruit up to the dining-room, will you? I’ll arrange it before I go upstairs.”

It was dusky in the dining-room and quite chilly. But all the same Bertha threw off her coat; she could not bear the tight clasp of it another moment, and the cold air fell on her arms.

But in her bosom there was still that bright glowing place–that shower of little sparks coming from it. It was almost unbearable. She hardly dared to breathe for fear of fanning it higher, and yet she breathed deeply, deeply. She hardly dared to look into the cold mirror–but she did look, and it gave her back a woman, radiant, with smiling, trembling lips, with big, dark eyes and an air of listening, waiting for something … divine to happen … that she knew must happen … infallibly.

Mary brought in the fruit on a tray and with it a glass bowl, and a blue dish, very lovely, with a strange sheen on it as though it had been dipped in milk.

“Shall I turn on the light, M’m?”

“No, thank you. I can see quite well.”

There were tangerines and apples stained with strawberry pink. Some yellow pears, smooth as silk, some white grapes covered with a silver bloom and a big cluster of purple ones. These last she had bought to tone in with the new dining-room carpet. Yes, that did sound rather farfetched and absurd, but it was really why she had bought them. She had thought in the shop: “I must have some purple ones to bring the carpet up to the table.” And it had seemed quite sensible at the time.

When she had finished with them and had made two pyramids of these bright round shapes, she stood away from the table to get the effect — and it really was most curious. For the dark table seemed to melt into the dusky light and the glass dish and the blue bowl to float in the air. This, of course, in her present mood, was so incredibly beautiful … She began to laugh.

“No, no. I’m getting hysterical.” And she seized her bag and coat and ran upstairs to the nursery.

Nurse sat at a low table giving Little B her supper after her bath. The baby had on a white flannel gown and a blue woolen jacket, and her dark, fine hair was brushed up into a funny little peak. She looked up when she saw her mother and began to jump.

“Now, my lovey, eat it up like a good girl,” said nurse, setting her lips in a way that Bertha knew, and that meant she had come into the nursery at another wrong moment.

“Has she been good, Nanny?”

“She’s been a little sweet all the afternoon,” whispered Nanny. “We went to the park and I sat down on a chair and took her out of the pram and a big dog came along and put its head on my knee and she clutched its ear, tugged it. Oh, you should have seen her.”

Bertha wanted to ask if it wasn’t rather dangerous to let her clutch at a strange dog’s ear. But she did not dare to. She stood watching them, her hands by her side, like the poor little girl in front of the rich girl with the doll.

The baby looked up at her again, stared, and then smiled so charmingly that Bertha couldn’t help crying:

“Oh, Nanny, do let me finish giving her her supper while you put the bath things away.

“Well, M’m, she oughtn’t to be changed hands while she’s eating,” said Nanny, still whispering. “It unsettles her; it’s very likely to upset her.”

How absurd it was. Why have a baby if it has to be kept–not in a case like a rare, rare fiddle–but in another woman’s arms?

“Oh, I must!” said she.

Very offended, Nanny handed her over.

“Now, don’t excite her after her supper. You know you do, M’m. And I have such a time with her after!”

Thank heaven! Nanny went out of the room with the bath towels.

“Now I’ve got you to myself, my little precious,” said Bertha, as the baby leaned against her.

She ate delightfully, holding up her lips for the spoon and then waving her hands. Sometimes she wouldn’t let the spoon go; and sometimes, just as Bertha had filled it, she waved it away to the four winds.

When the soup was finished Bertha turned round to the fire. “You’re nice — you’re very nice!” said she, kissing her warm baby. “I’m fond of you. I like you.”

And indeed, she loved Little B so much–her neck as she bent forward, her exquisite toes as they shone transparent in the firelight — that all her feeling of bliss came back again, and again she didn’t know how to express it–what to do with it.

“You’re wanted on the telephone,” said Nanny, coming back in triumph and seizing her Little B.

Down she flew. It was Harry.

“Oh, is that you, Ber? Look here. I’ll be late. I’ll take a taxi and come along as quickly as I can, but get dinner put back ten minutes — will you? All right?”

“Yes, perfectly. Oh, Harry!”

“Yes?”

What had she to say? She’d nothing to say. She only wanted to get in touch with him for a moment. She couldn’t absurdly cry: “Hasn’t it been a divine day!”

“What is it?” rapped out the little voice.

“Nothing. Entendu,” said Bertha, and hung up the receiver, thinking how much more than idiotic civilisation was.

They had people coming to dinner. The Norman Knights — a very sound couple — he was about to start a theatre, and she was awfully keen on interior decoration, a young man, Eddie Warren, who had just published a little book of poems and whom everybody was asking to dine, and a “find” of Bertha’s called Pearl Fulton. What Miss Fulton did, Bertha didn’t know. They had met at the club and Bertha had fallen in love with her, as she always did fall in love with beautiful women who had something strange about them.

The provoking thing was that, though they had been about together and met a number of times and really talked, Bertha couldn’t make her out. Up to a certain point Miss Fulton was rarely, wonderfully frank, but the certain point was there, and beyond that she would not go.

Was there anything beyond it? Harry said “No.” Voted her dullish, and “cold like all blonde women, with a touch, perhaps, of anaemia of the brain.” But Bertha wouldn’t agree with him; not yet, at any rate.

“No, the way she has of sitting with her head a little on one side, and smiling, has something behind it, Harry, and I must find out what that something is.”

“Most likely it’s a good stomach,” answered Harry.

Katherine Mansfield page on Amazon

He made a point of catching Bertha’s heels with replies of that kind … “liver frozen, my dear girl,” or “pure flatulence,” or “kidney disease,” … and so on. For some strange reason Bertha liked this, and almost admired it in him very much.

She went into the drawing-room and lighted the fire; then, picking up the cushions, one by one, that Mary had disposed so carefully, she threw them back on to the chairs and the couches. That made all the difference; the room came alive at once. As she was about to throw the last one she surprised herself by suddenly hugging it to her, passionately, passionately. But it did not put out the fire in her bosom. Oh, on the contrary!

The windows of the drawing-room opened on to a balcony overlooking the garden. At the far end, against the wall, there was a tall, slender pear tree in fullest, richest bloom; it stood perfect, as though becalmed against the jade-green sky. Bertha couldn’t help feeling, even from this distance, that it had not a single bud or a faded petal. Down below, in the garden beds, the red and yellow tulips, heavy with flowers, seemed to lean upon the dusk. A grey cat, dragging its belly, crept across the lawn, and a black one, its shadow, trailed after. The sight of them, so intent and so quick, gave Bertha a curious shiver.

“What creepy things cats are!” she stammered, and she turned away from the window and began walking up and down… .

How strong the jonquils smelled in the warm room. Too strong? Oh, no. And yet, as though overcome, she flung down on a couch and pressed her hands to her eyes.

“I’m too happy — too happy!” she murmured.

And she seemed to see on her eyelids the lovely pear tree with its wide open blossoms as a symbol of her own life.

Really — really — she had everything. She was young. Harry and she were as much in love as ever, and they got on together splendidly and were really good pals. She had an adorable baby. They didn’t have to worry about money. They had this absolutely satisfactory house and garden. And friends — modern, thrilling friends, writers and painters and poets or people keen on social questions–just the kind of friends they wanted. And then there were books, and there was music, and she had found a wonderful little dressmaker, and they were going abroad in the summer, and their new cook made the most superb omelettes… .

“I’m absurd. Absurd!” She sat up; but she felt quite dizzy, quite drunk. It must have been the spring.

Yes, it was the spring. Now she was so tired she could not drag herself upstairs to dress.

A white dress, a string of jade beads, green shoes and stockings. It wasn’t intentional. She had thought of this scheme hours before she stood at the drawing-room window.

Her petals rustled softly into the hall, and she kissed Mrs. Norman Knight, who was taking off the most amusing orange coat with a procession of black monkeys round the hem and up the fronts.

” … Why! Why! Why is the middle-class so stodgy–so utterly without a sense of humour! My dear, it’s only by a fluke that I am here at all–Norman being the protective fluke. For my darling monkeys so upset the train that it rose to a man and simply ate me with its eyes. Didn’t laugh–wasn’t amused — that I should have loved. No, just stared–and bored me through and through.”

“But the cream of it was,” said Norman, pressing a large tortoiseshell-rimmed monocle into his eye, “you don’t mind me telling this, Face, do you?” (In their home and among their friends they called each other Face and Mug.) “The cream of it was when she, being full fed, turned to the woman beside her and said: ‘Haven’t you ever seen a monkey before?'”

“Oh, yes!” Mrs. Norman Knight joined in the laughter. “Wasn’t that too absolutely creamy?”

And a funnier thing still was that now her coat was off she did look like a very intelligent monkey — who had even made that yellow silk dress out of scraped banana skins. And her amber ear-rings: they were like little dangling nuts.

“This is a sad, sad fall!” said Mug, pausing in front of Little B’s perambulator. “When the perambulator comes into the hall — ” and he waved the rest of the quotation away.

The bell rang. It was lean, pale Eddie Warren (as usual) in a state of acute distress.

“It is the right house, isn’t it?” he pleaded.

“Oh, I think so — I hope so,” said Bertha brightly.

“I have had such a dreadful experience with a taxi-man; he was most sinister. I couldn’t get him to stop. The more I knocked and called the faster he went. And in the moonlight this bizarre figure with the flattened head crouching over the little wheel … “

He shuddered, taking off an immense white silk scarf. Bertha noticed that his socks were white, too — most charming.

“But how dreadful!” she cried.

“Yes, it really was,” said Eddie, following her into the drawing-room. “I saw myself driving through Eternity in a timeless taxi.”

He knew the Norman Knights. In fact, he was going to write a play for N.K. when the theatre scheme came off.

“Well, Warren, how’s the play?” said Norman Knight, dropping his monocle and giving his eye a moment in which to rise to the surface before it was screwed down again.

And Mrs. Norman Knight: “Oh, Mr. Warren, what happy socks?”

“I am so glad you like them,” said he, staring at his feet. “They seem to have got so much whiter since the moon rose.” And he turned his lean sorrowful young face to Bertha. “There is a moon, you know.”

She wanted to cry: “I am sure there is–often–often!”

He really was a most attractive person. But so was Face, crouched before the fire in her banana skins, and so was Mug, smoking a cigarette and saying as he flicked the ash: “Why doth the bridegroom tarry?”

“There he is, now.”

Bang went the front door open and shut. Harry shouted: “Hullo, you people. Down in five minutes.” And they heard him swarm up the stairs. Bertha couldn’t help smiling; she knew how he loved doing things at high pressure. What, after all, did an extra five minutes matter? But he would pretend to himself that they mattered beyond measure. And then he would make a great point of coming into the drawing-room, extravagantly cool and collected.

Harry had such a zest for life. Oh, how she appreciated it in him. And his passion for fighting–for seeking in everything that came up against him another test of his power and of his courage — that, too, she understood. Even when it made him just occasionally, to other people, who didn’t know him well, a little ridiculous perhaps… . For there were moments when he rushed into battle where no battle was … She talked and laughed and positively forgot until he had come in (just as she had imagined) that Pearl Fulton had not turned up.

“I wonder if Miss Fulton has forgotten?”

“I expect so,” said Harry. “Is she on the ‘phone?”

“Ah! There’s a taxi, now.” And Bertha smiled with that little air of proprietorship that she always assumed while her women finds were new and mysterious. “She lives in taxis.”

“She’ll run to fat if she does,” said Harry coolly, ringing the bell for dinner. “Frightful danger for blonde women.”

“Harry–don’t!” warned Bertha, laughing up at him.

Came another tiny moment, while they waited, laughing and talking, just a trifle too much at their ease, a trifle too unaware. And then Miss Fulton, all in silver, with a silver fillet binding her pale blonde hair, came in smiling, her head a little on one side.

“Am I late?”

“No, not at all,” said Bertha. “Come along.” And she took her arm and they moved into the dining-room.

What was there in the touch of that cool arm that could fan–fan–start blazing–blazing–the fire of bliss that Bertha did not know what to do with?

Miss Fulton did not look at her; but then she seldom did look at people directly. Her heavy eyelids lay upon her eyes and the strange half-smile came and went upon her lips as though she lived by listening rather than seeing. But Bertha knew, suddenly, as if the longest, most intimate look had passed between them–as if they had said to each other: “You too?” — that Pearl Fulton, stirring the beautiful red soup in the grey plate, was feeling just what she was feeling.

And the others? Face and Mug, Eddie and Harry, their spoons rising and falling–dabbing their lips with their napkins, crumbling bread, fiddling with the forks and glasses and talking.

“I met her at the Alpha show–the weirdest little person. She’d not only cut off her hair, but she seemed to have taken a dreadfully good snip off her legs and arms and her neck and her poor little nose as well.”

“Isn’t she very liée with Michael Oat?”

“The man who wrote Love in False Teeth? “

“He wants to write a play for me. One act. One man. Decides to commit suicide. Gives all the reasons why he should and why he shouldn’t. And just as he has made up his mind either to do it or not to do it–curtain. Not half a bad idea.”

“What’s he going to call it — ‘Stomach Trouble’ ?”

“I think I’ve come across the same idea in a little French review, quite unknown in England.”

No, they didn’t share it. They were dears–dears–and she loved having them there, at her table, and giving them delicious food and wine. In fact, she longed to tell them how delightful they were, and what a decorative group they made, how they seemed to set one another off and how they reminded her of a play by Tchekof!

Harry was enjoying his dinner. It was part of his–well, not his nature, exactly, and certainly not his pose–his–something or other–to talk about food and to glory in his “shameless passion for the white flash of the lobster” and “the green of pistachio ices–green and cold like the eyelids of Egyptian dancers.”

When he looked up at her and said: “Bertha, this is a very admirable soufflée! ” she almost could have wept with child-like pleasure.

Oh, why did she feel so tender towards the whole world tonight? Everything was good–was right. All that happened seemed to fill again her brimming cup of bliss.