Nava Atlas's Blog, page 76

November 28, 2018

Laura Ingalls Wilder

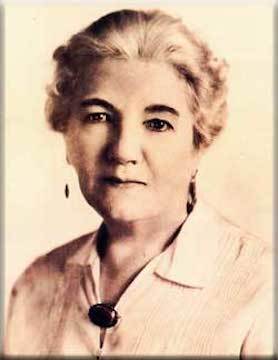

Laura Ingalls Wilder (February 7, 1867 – February 10, 1957) gained renown for her autobiographical writings about growing up as an American pioneer. Particularly beloved are her Little House series of books for young readers. Born in a log cabin on the edge of an area called “Big Woods” in Pepin, Wisconsin, her life was the inspiration for her novels and richly informed her memoirs.

The Ingalls family traveled by covered wagon through Kansas and Minnesota with all that they owned, until finally settling in De Smet, Dakota Territory. The family loved the open spaces of the prairie, where they farmed and raised animals.

The Ingalls moved around quite a bit, and though it wasn’t an easy life, it gave Laura a rich trove of memories and experiences to draw upon when she began writing. It may be comforting to aspiring writers of all ages that her first book wasn’t published until she was sixty-five!

Another long journey

Though Laura wasn’t conventionally educated, she managed to get her teaching certificate at the age of fifteen. Three years later, she married Almonzo Wilder, and helped her husband work the farm that they lived on. In 1894, The couple and their seven-year-old daughter, Rose, made the journey from their drought-stricken farm in De Smet to a new farm in Mansfield, Missouri, where they settled permanently. She told of this journey in diary entries that were later published in On the Way Home.

A brief glimpse of Laura

Prairie Fires:The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder, the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography by Caroline Fraser, opens with a compelling portrait of Laura in adulthood. Here she is, portrayed at age fifty-seven, shortly after her mother’s death:

“At fifty seven, Wilder was still far from becoming the emblematic figure of pioneer history. The woman whose life would become synonymous with the settlement of the West had spent most of her adult life living in the American South. She was not yet famous, had not yet written a book; the only writing she had published was her farm paper column. Anxious, she suffered from nerves and had a recurrent nightmare of walking down a “long, dark road” into obscure woods, the path of poverty.

… She had a sharp temper and a dry humor … Judgmental of others, she could be humble, even self-excoriating. She was parsimonious to a fault, but when she went into town she dressed elegantly in full skirts, lace collars, and hats garlanded with feathers or flowers. She favored long, dangling earrings, fastening her blouses with a cameo brooch. She loved velvet.

She was not an intellectual, but she had an intellect. She had never graduated from high school, but had studied with passion and vigor the Independent Fifth Reader. She knew a song for every occasion and passages of Shakespeare, Longfellow, Tennyson, Scott, Swinburne, and the Brownings. Books took pride of place in her living room, on custom-built shelves beside a stone hearth.

As her fifties drew to a close, she stood at a turning point. The first act of her life was long over. Her childhood had been packed with incident: Indian encounters, prairie fires, blizzards, a virtual compendium of American frontier life … She married at eighteen and was a mother a year later.

By age of twenty-one, she know that everything she had ever had, no matter how hard-won, held the capacity to be lost. After a series of disasters, she and her husband left the Dakotas to rebuild seven hundred miles south, a long climb out of poverty constituting her life’s second act.”

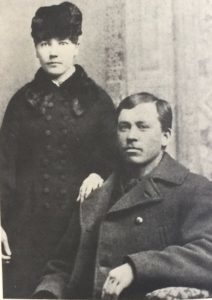

Laura and Almonzo at about the time they married

The Little House books

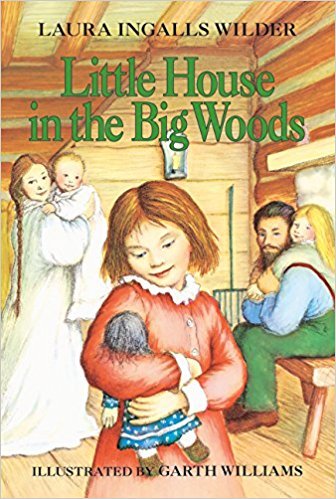

Drought, crop failure, and Almonzo’s illness put the Wilders in a precarious position. Finally, in the 1920s, Laura got encouragement from her daughter Rose as well as the time that she needed to start writing. The first of the autobiographical Little House books, Little House in the Big Woods, was published in 1931; Laura was well into her sixties at the time. The best known volume of the series, Little House on the Prairie, was published soon after.

The family depicted in the stories was an idealized version of the one she grew up in. The Little House books tell of a family, not unlike her own, pioneering the Great Plains in the mid-1800s. Life was simple but good, yet of course, had its challenges. Little House in the Big Woods begins when the eponymous Laura is five years old; the family is headed by Ma and Pa, and rounded out by two sisters, Mary and Carrie.

Laura Ingalls Wilder page on Amazon

The series continues with By the Shores of Silver Lake and The Long Winter. In Little House on the Prairie, perhaps the best known in the series, Laura comes of age and becomes a teacher. Next comes These Happy Golden Years, in which Laura marries Almonzo and they move to their own home.

Laura Ingalls Wilder’s tales immediately appealed to readers of all ages — nine in the Little House series in all. The books were an immediate critical and popular success, winning numerous awards and making their way into the hearts of generations of readers with their message of endurance, simple living, and love of family. Though presented as fiction, the author insisted, “I lived everything I wrote.”

You might also like: Comforting Quotes by Laura Ingalls Wilder

Husband Almonzo and daughter Rose

She enjoyed a 64-year marriage with her husband Almonzo. Rose, their only daughter, was said to have played a fairly substantial role in making Laura’s books the eminently readable works of children’s literature that they became. Some have been less kind about Rose’s role in her mother’s writing career, and there have been numerous controversies around this issue.

The Wilder family, who had lost nearly everything in the early years of the Depression, became very wealthy indeed upon the publication of the Little House books. But in the end what matters is how beloved these books have been for generations of readers.

Laura’s beloved husband Almonzo died in 1949 at the age of 92. She lived for several more years and died in 1957 on her farm in Mansfield, Missouri at the age of 90.

More about Laura Ingalls Wilder on this site

Comforting Quotes by Laura Ingalls Wilder

Laura Ingalls Wilder: Late Blooming Author with a Passion for Nature

Caroline: Little House, Revisited (a novel)

Major Works

Little House on the Prairie Series

Autobiographies and Biographies about Laura Ingalls Wilder

Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Biography by William Anderson

Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Writer’s Life by Pamela Smith Hill

Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography

Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder by Caroline Fraser

On the Way Home: The Diary of a Trip from South Dakota by Laura Ingalls Wilder

West from Home: Letters of Laura Ingalls Wilder, San Francisco, 1915

More Information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s books on Goodreads

10 Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Laura Ingalls Wilder

In Search of Laura: Some Historical Facts

Selected film adaptations of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s books

Little House on the Prairie Complete Series (1974 – 82)

Little House on the Prairie (2005)

Little House on the Prairie – Movie Boxed Set (1983)

Visit Laura Ingalls Wilder’s homes and museums

Laura Ingalls Wilder Historic Home and Museum – Mansfield, MO

Wilder Homestead – Malone, NY

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Laura Ingalls Wilder appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 26, 2018

“The Two Offers” by Frances Watkins Harper – full text

“The Two Offers” by Frances Watkins Harper (1825 – 1922; also known as Frances E.W. Harper) is believed to be the first published short story by an African-American writer. It first appeared in the June and July 1859 issues of the Anglo-African Magazine, a publication based in New York that featured the writings of black authors.

Written in the sentimental, somewhat stilted style of the era, the story is an example of “reform literature,” steeped in the values of Christianity, morality, and domesticity. It’s set in an era in which women of any class or race were basically the property of their fathers and husbands, were they not owned in the bonds of slavery

The story centers on two cousins, Laura Lagrange and Janette Alston. Laura and ponders two offers of marriage. This was about as much choice as many women could exercise at a time when it was considered more important to be “the angel of the house” than the mistress of one’s own life.

Making the choice of who, and less commonly whether, to marry was the biggest decision a woman of that era could make. As fate would have it, Laura marries a man who proves worthless and Janette remains, in the parlance of the day, a spinster. How much of their choice was based on what they really wanted, rather than what society dictated for women? What part of their decision was based on fear, both of the known and unknown?

Harper, though a believer in traditional values, seems to have presented this story as a cautionary tale, warning women not to rely entirely on romantic love and marriage as their goal in life.

Frances Watkins Harper, in addition to a being prolific writer of poetry and prose, was a social reformer, suffragist, lecturer, and abolitionist. Freeborn in Baltimore, Maryland, her first collection of poetry was published in 1845, when she was twenty. Much later, the novel Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted (1892) was another critical and commercial success.

“The Two Offers” is reprinted below in full. Some of the very long paragraphs of the original text have been broken up for easier readability. Originally published in the Anglo-African Magazine (June and July, 1859), it is in the public domain. The source of this text is HistoryTool.org.

“The Two Offers” by Frances Elizabeth Watkins Harper

“What is the matter with you, Laura, this morning? I have been watching you this hour, and in that time you have commenced a half dozen letters and torn them all up. What matter of such grave moment is puzzling your dear little head, that you do not know how to decide?”

“Well, it is an important matter: I have two offers for marriage, and I do not know which to choose.”

“I should accept neither, or to say the least, not at present.”

“Why not?”

“Because I think a woman who is undecided between two offers, has not love enough for either to make a choice; and in that very hesitation, indecision, she has a reason to pause and seriously reflect, lest her marriage, instead of being an affinity of souls or a union of hearts, should only be a mere matter of bargain and sale, or an affair of convenience and selfish interest.”

“But I consider them both very good offers, just such as many a girl would gladly receive. But to tell you the truth, I do not think that I regard either as a woman should the man she chooses for her husband. But then if I refuse, there is the risk of being an old maid, and that is not to be thought of.”

“Well, suppose there is, is that the most dreadful fate that can befall a woman? Is there not more intense wretchedness in an ill-assorted marriage—more utter loneliness in a loveless home, than in the lot of the old maid who accepts her earthly mission as a gift from God, and strives to walk the path of life with earnest and unfaltering steps?”

“Oh! what a little preacher you are. I really believe that you were cut out for an old maid; that when nature formed you, she put in a double portion of intellect to make up for a deficiency of love; and yet you are kind and affectionate. But I do not think that you know anything of the grand, over-mastering passion, or the deep necessity of woman’s heart for loving.”

You might also enjoy:

6 Fascinating African-American Women Writers of the 19th Century

“Do you think so?” resumed the first speaker; and bending over her work she quietly applied herself to the knitting that had lain neglected by her side, during this brief conversation; but as she did so, a shadow flitted over her pale and intellectual brow, a mist gathered in her eyes, and a slight quivering of the lips, revealed a depth of feeling to which her companion was a stranger.

But before I proceed with my story, let me give you a slight history of the speakers. They were cousins, who had met life under different auspices. Laura Lagrange, was the only daughter of rich and indulgent parents, who had spared no pains to make her an accomplished lady. Her cousin, Janette Alston, was the child of parents, rich only in goodness and affection. Her father had been unfortunate in business, and dying before he could retrieve his fortunes, left his business in an embarrassed state. His widow was unacquainted with his business affairs, and when the estate was settled, hungry creditors had brought their claims and the lawyers had received their fees, she found herself homeless and almost penniless, and she who had been sheltered in the warm clasp of loving arms, found them too powerless to shield her from the pitiless pelting storms of adversity.

Year after year she struggled with poverty and wrestled with want, till her toil-worn hands became too feeble to hold the shattered chords of existence, and her tear-dimmed eyes grew heavy with the slumber of death. Her daughter had watched over her with untiring devotion, had closed her eyes in death, and gone out into the busy, restless world, missing a precious tone from the voices of earth, a beloved step from the paths of life.

Too self reliant to depend on the charity of relations, she endeavored to support herself by her own exertions, and she had succeeded. Her path for a while was marked with struggle and trial, but instead of uselessly repining, she met them bravely, and her life became not a thing of ease and indulgence, but of conquest, victory, and accomplishments.

At the time when this conversation took place, the deep trials of her life had passed away. The achievements of her genius had won her a position in the literary world, where she shone as one of its bright particular stars. And with her fame came a competence of worldly means, which gave her leisure for improvement, and the riper development of her rare talents.

And she, that pale intellectual woman, whose genius gave life and vivacity to the social circle, and whose presence threw a halo of beauty and grace around the charmed atmosphere in which she moved, had at one period of her life, known the mystic and solemn strength of an all-absorbing love. Years faded into the misty past, had seen the kindling of her eye, the quick flushing of her cheek, and the wild throbbing of her heart, at tones of a voice long since hushed to the stillness of death.

Deeply, wildly, passionately, she had loved. Her whole life seemed like the pouring out of rich, warm and gushing affections. This love quickened her talents, inspired her genius, and threw over her life a tender and spiritual earnestness. And then came a fearful shock, a mournful waking from that “dream of beauty and delight.”

A shadow fell around her path; it came between her and the object of her heart’s worship; first a few cold words, estrangement, and then a painful separation; the old story of woman’s pride—digging the sepulchre of her happiness, and then a new-made grave, and her path over it to the spirit world; and thus faded out from that young heart her bright, brief and saddened dream of life.

Faint and spirit-broken, she turned from the scenes associated with the memory of the loved and lost. She tried to break the chain of sad associations that bound her to the mournful past; and so, pressing back the bitter sobs from her almost breaking heart, like the dying dolphin, whose beauty is born of its death anguish, her genius gathered strength from suffering and wondrous power and brilliancy from the agony she hid within the desolate chambers of her soul.

Men hailed her as one of earth’s strangely gifted children, and wreathed the garlands of fame for her brow, when it was throbbing with a wild and fearful unrest. They breathed her name with applause, when through the lonely halls of her stricken spirit, was an earnest cry for peace, a deep yearning for sympathy and heart-support.

But life, with its stern realities, met her; its solemn responsibilities confronted her, and turning, with an earnest and shattered spirit, to life’s duties and trials, she found a calmness and strength that she had only imagined in her dreams of poetry and song.

We will now pass over a period of ten years, and the cousins have met again. In that calm and lovely woman, in whose eyes is a depth of tenderness, tempering the flashes of her genius, whose looks and tones are full of sympathy and love, we recognize the once smitten and stricken Janette Alston. The bloom of her girlhood had given way to a higher type of spiritual beauty, as if some unseen hand had been polishing and refining the temple in which her lovely spirit found its habitation; and this had been the fact. Her inner life had grown beautiful, and it was this that was constantly developing the outer.

Never, in the early flush of womanhood, when an absorbing love had lit up her eyes and glowed in her life, had she appeared so interesting as when, with a countenance which seemed overshadowed with a spiritual light, she bent over the death-bed of a young woman, just lingering at the shadowy gates of the unseen land.

“Has he come?” faintly but eagerly exclaimed the dying woman. “Oh! how I have longed for his coming, and even in death he forgets me.”

“Oh, do not say so, dear Laura, some accident may have detained him,” said Janette to her cousin; for on that bed, from whence she will never rise, lies the once-beautiful and lighthearted Laura Lagrange, the brightness of whose eyes has long since been dimmed with tears, and whose voice had become like a harp whose every chord is turned to sadness—whose faintest thrill and loudest vibrations are but the variations of agony.

A heavy hand was laid upon her once warm and bounding heart, and a voice came whispering through her soul, that she must die. But, to her, the tidings was a message of deliverance—a voice, hushing her wild sorrows to the calmness of resignation and hope. Life had grown so weary upon her head— the future looked so hopeless—she had no wish to tread again the track where thorns had pierced her feet, and clouds overcast her sky; and she hailed the coming of death’s angel as the footsteps of a welcome friend.

And yet, earth had one object so very dear to her weary heart. It was her absent and 4 recreant husband; for, since that conversation, she had accepted one of her offers, and become a wife. But, before she married, she learned that great lesson of human experience and woman’s life, to love the man who bowed at her shrine, a willing worshipper. He had a pleasing address, raven hair, flashing eyes, a voice of thrilling sweetness, and lips of persuasive eloquence; and being well versed in the ways of the world, he won his way to her heart, and she became his bride, and he was proud of his prize.

Vain and superficial in his character, he looked upon marriage not as a divine sacrament for the soul’s development and human progression, but as the title-deed that gave him possession of the woman he thought he loved. But alas for her, the laxity of his principles had rendered him unworthy of the deep and undying devotion of a pure-hearted woman; but, for awhile, he hid from her his true character, and she blindly loved him, and for a short period was happy in the consciousness of being beloved; though sometimes a vague unrest would fill her soul, when, overflowing with a sense of the good, the beautiful, and the true, she would turn to him, but find no response to the deep yearnings of her soul—no appreciation of life’s highest realities—its solemn grandeur and significant importance.

Their souls never met, and soon she found a void in her bosom, that his earth-born love could not fill. He did not satisfy the wants of her mental and moral nature—between him and her there was no affinity of minds, no intercommunion of souls.

Talk as you will of woman’s deep capacity for loving, of the strength of her affectional nature. I do not deny it; but will the mere possession of any human love, fully satisfy all the demands of her whole being? You may paint her in poetry or fiction, as a frail vine, clinging to her brother man for support, and dying when deprived of it; and all this may sound well enough to please the imaginations of school-girls, or love-lorn maidens.

But woman—the true woman—if you would render her happy, it needs more than the mere development of her affectional nature. Her conscience should be enlightened, her faith in the true and right established, scope given to her Heaven-endowed and God-given faculties. The true aim of female education should be not a development of one or two, but all the faculties of the human soul, because no perfect womanhood is developed by imperfect culture. Intense love is often akin to intense suffering, and to trust the whole wealth of a woman’s nature on the frail bark of human love, may often be like trusting a cargo of gold and precious gems, to a bark that has never battled with the storm, or buffeted the waves.

Is it any wonder, then, that so many life-barks go down, paving the ocean of time with precious hearts and wasted hopes? that so many float around us, shattered and dismasted wrecks? that so many are stranded on the shoals of existence, mournful beacons and solemn warnings for the thoughtless, to whom marriage is a careless and hasty rushing together of the affections? Alas that an institution so fraught with good for humanity should be so perverted, and that state of life, which should be filled with happiness, become so replete with misery.

And this was the fate of Laura Lagrange. For a brief period after her marriage her life seemed like a bright and beautiful dream, full of hope and radiant with joy. And then there came a change—he found other attractions that lay beyond the pale of home influences. The gambling saloon had power to win him from her side, he had lived in an element of unhealthy and unhallowed excitements, and the society of a loving wife, the pleasures of a well-regulated home, were enjoyments too tame for one who had vitiated his tastes by the pleasures of sin. There were charmed houses of vice, built upon dead men’s loves, where, amid the flow of song, laughter, wine, and careless mirth, he would spend hour after hour, forgetting the cheek that was paling through his neglect, heedless of the tear-dimmed eyes, peering anxiously into the darkness, waiting, or watching his return.

The influence of old associations was upon him. In early life, home had been to him a place of ceilings and walls, not a true home, built upon goodness, love and truth. It was a place where velvet carpets hushed its tread, where images of loveliness and beauty invoked into being by painter’s art and sculptor’s skill, pleased the eye and gratified the taste, where magnificence surrounded his way and costly clothing adorned his person; but it was not the place for the true culture and right development of his soul.

His father had been too much engrossed in making money, and his mother in spending it, in striving to maintain a fashionable position in society, and shining in the eyes of the world, to give the proper direction to the character of their wayward and impulsive son. His mother put beautiful robes upon his body, but left ugly scars upon his soul; she pampered his appetite, but starved his spirit. Every mother should be a true artist, who knows how to weave into her child’s life images of grace and beauty, the true poet capable of writing on the soul of childhood the harmony of love and truth, and teaching it how to produce the grandest of all poems—the poetry of a true and noble life.

But in his home, a love for the good, the true and right, had been sacrificed at the shrine of frivolity and fashion. That parental authority which should have been preserved as a string of precious pearls, unbroken and unscattered, was simply the administration of chance. At one time obedience was enforced by authority, at another time by flattery and promises, and just as often it was not enforced at all. His early associations were formed as chance directed, and from his want of home-training, his character received a bias, his life a shade, which ran through every avenue of his existence, and darkened all his future hours.

Oh, if we would trace the history of all the crimes that have o’ershadowed this sin-shrouded and sorrow-darkened world of ours, how many might be seen arising from the wrong home influences, or the weakening of the home ties. Home should always be the best school for the affections, the birthplace of high resolves, and the altar upon which lofty aspirations are kindled, from whence the soul may go forth strengthened, to act its part aright in the great drama of life with conscience enlightened, affections cultivated, and reason and judgment dominant.

But alas for the young wife. Her husband had not been blessed with such a home. When he entered the arena of life, the voices from home did not linger around his path as angels of guidance about his steps; they were not like so many messages to invite him to deeds of high and holy worth. The memory of no sainted mother arose between him and deeds of darkness; the earnest prayers of no father arrested him in his downward course: and before a year of his married life had waned, his young wife had learned to wait and mourn his frequent and uncalled-for absence.

More than once had she seen him come home from his midnight haunts, the bright intelligence of his eye displaced by the drunkard’s stare, and his manly gait changed to the inebriate’s stagger; and she was beginning to know the bitter agony that is compressed in the mournful words, a drunkard’s wife.

And then there came a bright but brief episode in her experience; the angel of life gave to her existence a deeper meaning and loftier significance; she sheltered in the warm clasp of her loving arms, a dear babe, a precious child, whose love filled every chamber of her heart, and felt the fount of maternal love gushing so new within her soul. That child was hers. How overshadowing was the love with which she bent over its helplessness, how much it helped to fill the void and chasms in her soul. How many lonely hours were beguiled by its winsome ways, its answering smiles and fond caresses. How exquisite and solemn was the feeling that thrilled her heart when she clasped the tiny hands together and taught her dear child to call God “Our Father.”

What a blessing was that child. The father paused in his headlong career, awed by the strange beauty and precocious intellect of his child; and the mother’s life had a better expression through her ministrations of love. And then there came hours of bitter anguish, shading the sunlight of her home and hushing the music of her heart. The angel of death bent over the couch of her child and beaconed it away. Closer and closer the mother strained her child to her wildly heaving breast, and struggled with the heavy hand that lay upon its heart. Love and agony contended with death, and the language of the mother’s heart was,

“Oh, Death, away! that innocent is mine;

I cannot spare him from my arms

To lay him, Death, in thine.

I am a mother, Death; I gave that darling birth

I could not bear his lifeless limbs

Should moulder in the earth.”

But death was stronger than love and mightier than agony and won the child for the land of crystal founts and deathless flowers, and the poor, stricken mother sat down beneath the shadow of her mighty grief, feeling as if a great light had gone out from her soul, and that the sunshine had suddenly faded around her path. She turned in her deep anguish to the father of her child, the loved and cherished dead.

For awhile his words were kind and tender, his heart seemed subdued, and his tenderness fell upon her worn and weary heart like rain on perishing flowers, or cooling waters to lips all parched with thirst and scorched with fever; but the change was evanescent, the influence of unhallowed associations and evil habits had vitiated and poisoned the springs of his existence. They had bound him in their meshes, and he lacked the moral strength to break his fetters, and stand erect in all the strength and dignity of a true manhood, making life’s highest excellence his ideal, and striving to gain it.

And yet moments of deep contrition would sweep over him, when he would resolve to abandon the wine-cup forever, when he was ready to forswear the handling of another card, and he would try to break away from the associations that he felt were working his ruin; but when the hour of temptation came his strength was weakness, his earnest purposes were cobwebs, his well meant resolutions ropes of sand, and thus passed year after year of the married life of Laura Lagrange.

She tried to hide her agony from the public gaze, to smile when her heart was almost breaking. But year after year her voice grew fainter and sadder, her once light and bounding step grew slower and faltering. Year after year she wrestled with agony, and strove with despair, till the quick eyes of her brother read, in the paling of her cheek and the dimming eye, the secret anguish of her worn and weary spirit. On that wan, sad face, he saw the death-tokens, and he knew the dark wing of the mystic angel swept coldly around her path.

“Laura,” said her brother to her one day, “you are not well, and I think you need our mother’s tender care and nursing. You are daily losing strength, and if you will go I will accompany you.” At first, she hesitated, she shrank almost instinctively from presenting that pale sad face to the loved ones at home. That face was such a telltale; it told of heart-sickness, of hope deferred, and the mournful story of unrequited love.

But then a deep yearning for home sympathy woke within her a passionate longing for love’s kind words, for tenderness and heart support, and she resolved to seek the home of her childhood and lay her weary head upon her mother’s bosom, to be folded again in her loving arms, to lay that poor, bruised and aching heart where it might beat and throb closely to the loved ones at home.

A kind welcome awaited her. All that love and tenderness could devise was done to bring the bloom to her cheek and the light to her eye; but it was all in vain; her’s was a disease that no medicine could cure, no earthly balm would heal. It was a slow wasting of the vital forces, the sickness of the soul. The unkindness and neglect of her husband, lay like a leaden weight upon her heart, and slowly oozed way its life-drops. And where was he that had won her love, and then cast it aside as a useless thing, who rifled her heart of its wealth and spread bitter ashes upon its broken altars? He was lingering away from her when the death-damps were gathering on her brow, when his name was trembling on her lips! lingering away! when she was watching his coming, though the death films were gathering before her eyes, and earthly things were fading from her vision.

“I think I hear him now,” said the dying woman, “surely that is his step;” but the sound died away in the distance. Again she started from an uneasy slumber, “that is his voice! I am so glad he has come.”

Tears gathered in the eyes of the sad watchers by that dying bed, for they knew that she was deceived. He had not returned. For her sake they wished his coming. Slowly the hours waned away, and then came the sad, soul-sickening thought that she was forgotten, forgotten in the last hour of human need, forgotten when the spirit, about to be dissolved, paused for the last time on the threshold of existence, a weary watcher at the gates of death.

“He has forgotten me,” again she faintly murmured, and the last tears she would ever shed on earth sprung to her mournful eyes, and clasping her hands together in silent anguish, a few broken sentences issued from her pale and quivering lips. They were prayers for strength and earnest pleading for him who had desolated her young life, by turning its sunshine to shadows, its smiles to tears.

“He has forgotten me,” she murmured again, “but I can bear it, the bitterness of death is passed, and soon I hope to exchange the shadows of death for the brightness of eternity, the rugged paths of life for the golden streets of glory, and the care and turmoils of earth for the peace and rest of heaven.” Her voice grew fainter and fainter, they saw the shadows that never deceive flit over her pale and faded face, and knew that the death angel waited to soothe their weary one to rest, to calm the throbbing of her bosom and cool the fever of her brain.

And amid the silent hush of their grief the freed spirit, refined through suffering, and brought into divine harmony through the spirit of the living Christ, passed over the dark waters of death as on a bridge of light, over whose radiant arches hovering angels bent. They parted the dark locks from her marble brow, closed the waxen lids over the once bright and laughing eye, and left her to the dreamless slumber of the grave.

Her cousin turned from that death-bed a sadder and wiser woman. She resolved more earnestly than ever to make the world better by her example, gladder by her presence, and to kindle the fires of her genius on the altars of universal love and truth. She had a higher and better object in all her writings than the mere acquisition of gold, or acquirement of fame. She felt that she had a high and holy mission on the battle-field of existence, that life was not given her to be frittered away in nonsense, or wasted away in trifling pursuits. She would willingly espouse an unpopular cause but not an unrighteous one. In her the down-trodden slave found an earnest advocate; the flying fugitive remembered her kindness as he stepped cautiously through our Republic, to gain his freedom in a monarchial land, having broken the chains on which the rust of centuries had gathered.

Little children learned to name her with affection, the poor called her blessed, as she broke her bread to the pale lips of hunger. Her life was like a beautiful story, only it was clothed with the dignity of reality and invested with the sublimity of truth. True, she was an old maid. No husband brightened her life with his love, or shaded it with his neglect. No children nestling lovingly in her arms called her mother. No one appended Mrs. to her name; she was indeed an old maid, not vainly striving to keep up an appearance of girlishness, when departed was written on her youth.

Not vainly pining at her loneliness and isolation: the world was full of warm, loving hearts, and her own beat in unison with them. Neither was she always sentimentally sighing for something to love, objects of affection were all around her, and the world was not so wealthy in love that it had no use for her’s; in blessing others she made a life and benediction, and as old age descended peacefully and gently upon her, she had learned one of life’s most precious lessons, that true happiness consists not so much in the fruition of our wishes as in the regulation of desires and the full development and right culture of our whole statures.

The post “The Two Offers” by Frances Watkins Harper – full text appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 25, 2018

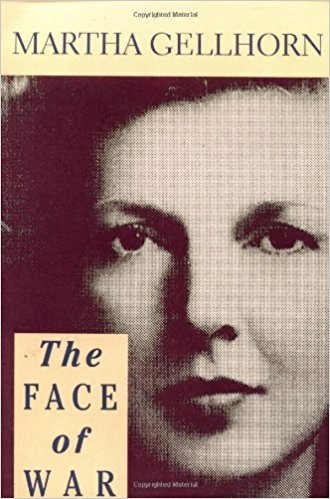

Liana by Martha Gellhorn (1944)

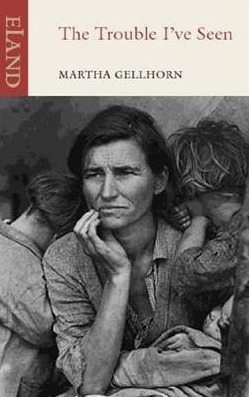

Martha Gellhorn was married to Ernest Hemingway when Liana, her fifth novel, was published in 1944. She had already made quite a name for herself as a war correspondent by that point and it rankled her to be described as “Mrs. Ernest Hemingway” in reviews of her books. Though her fiction varied in its quality and critical acclaim, her set of linked stories, The Trouble I’ve Seen (1936), based on her actual observations as a journalist during the Depression, earned her a great deal of respect.

Her brief marriage to Hemingway was already in jeopardy the year that Liana appeared. In her capacity as a war correspondent, Gellhorn wanted to cover the action, wherever it happened to be. In June of 1944 she sought to cover the landing of the Allied troops at Normandy, and was sabotaged from getting official press credentials by Hemingway, who resented her long absences. Undaunted, she forged ahead, employing her characteristic daring and subterfuge. She was the only female journalist at Normandy on D-Day.

When the novel was released early in 1944, World War II was coming to a peak and its author was otherwise preoccupied. It may not have received the kind of notice it might have, had it been published after the war.

An inauspicious marriage

The New York Times review of Liana from January 16, 1944 begins:

“With this new novel, Martha Gellhorn (Mrs. Ernest Hemingway) establishes herself as an honest and intelligent writer who has something to say and knows how to say it well. Liana has certain agreeable qualities of maturity and emotional understanding which are not always to be found in even the best modern art, still a predominantly male affair.

The story centers on Liana, who is described as a mulatto, or what we now call mixed-race. She marries Marc Royer, a wealthy white man on a fictional French Caribbean island called Saint Boniface. For his part, he marries her mainly to spite another woman, and so, Liana is marked by a kind of tragedy in this sense, becoming a prisoner in his home, and a partner to a man who doesn’t fully love her.

You might also enjoy: The Trouble I’ve Seen by Martha Gellhorn

An odd love triangle

As a way to mold her into a “white wife,” Marc engages a French intellectual named Pierre to tutor her. Predictably, Liana and Pierre fall in love, but Gellhorn is too skilled a writer to let the story devolve into love triangle cliché.

Marc, in fact, seems more sympathetic to Pierre than to his wife, but seen through Liana’s perspective, neither are to be completely trusted. She sees two white men conspiring against her. Things take a complicated turn when Pierre wants to join the war effort, comforted by the notion that in his absence Marc will care for her. Marc’s wealth makes him impervious to reproach, but in tying her fortunes to his, Liana has alienated herself from the black race that’s part of her heritage.

To quote again from the New York Times review:

“Pierre, the intellectual, is an old friend; you will find him, better drawn perhaps but recognizable, in a dozen modern novels. He is The Moral Man of E.M. Forester, The Natural Man of D.H. Lawrence … he is even, in some ways, Hemingway’s Man of Courage. If you are as tired of seeing this character defended, extolled, and exalted in all his aggressively masculine virtue, you will appreciate Miss Gellhorn’s attempt to show what he looks like to a woman.”

The quibble that this review has with the book is that Gellhorn writes too much from the mind and too little from the heart, and that as an artist, she should have done a more thorough job of capturing “the mysteries of personality.”

Learn more about Martha Gellhorn

Another 1944 review

Here’s another contemporaneous review of Liana:

From the original review by Pearl Allred of Liana by Martha Gellhorn in The Ogden Standard-Examiner, February 27, 1944: Martha Gellhorn has managed to avoid stereotype in this tale concerning the two men and a woman on the little French island of Saint Boniface in the Caribbean.

The fact that the woman — Liana — is a Mulatto complicates the situation, but does not, certainly, give it any special degree of freshness. Writers long before the period of Madame Butterfly and beyond the time of Wingless Victory have been preoccupied with the plight of the beautiful woman of color who, through no fault of her own, becomes the victim of a society to which she feels she doesn’t belong.

She is obligated to learn painfully not merely the fact that this is a man’s world, but that it is a white man’s world.

Liana, as the wife of Marc, the richest man on the island, is not happy, even though she has escaped from the existence she would have known among her own people. It is only when Pierre, the young French intellectual who has been engaged by Marc to tutor his wife, comes into her life that she knows what happiness can mean.

Pierre and Liana, as might be expected, fall in love, but the climax is not the usual and predicable one in a triangle which involves lovers and jealous husbands. The author has brought to her story an understanding of character and an emotional maturity which keeps the reader from feeling he has read the same thing not merely once, but many times before.

Liana, like Gellhorn’s first novel What Mad Pursuit (1934), is hard to come by. It would be fascinating to analyze whether a contemporary reading would feel racist or sexist. Though knowing Gellhorn and her strong feelings about humanity and women’s equality, it would be hard to imagine that she’d knowingly or disingenuously write a book with a biased slant. Copies of Liana are hard to come by. Check your library system, or the library of a college or university.

Martha Gellhorn page on Amazon

More about Liana by Martha Gellhorn

Full New York Times book review (1944)

Reader discussion on Goodreads

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Liana by Martha Gellhorn (1944) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 21, 2018

6 Fascinating African-American Women Writers of the 19th Century

Given the circumstances of the 19th century, both before and after emancipation, African-American women writers who took up the pen to write full books or other substantial bodies of work were rare indeed. It’s worth noting that before the Civil War, it was illegal to teach African-Americans to read in many states, not just in the South. So to write a novel or autobiography was a radical act for a black woman of that era, whether she had been enslaved or free born.

Not surprisingly, many of the books, essays, and poetry produced by African-American women writers dealt with slavery. Most of the autobiographies and thinly veiled novels discussed here were in the genre of slave narrative.

Lest you think we’ve forgotten Phillis Wheatley — the first African-American female poet to be published, and one of the first women of any background to be published in the colonies — we haven’t. She’s not included in this list because she lived and wrote exclusively in the 18th century. Here are six fascinating 19th-century African-American women writers whose talent and daring are ripe for rediscovery.

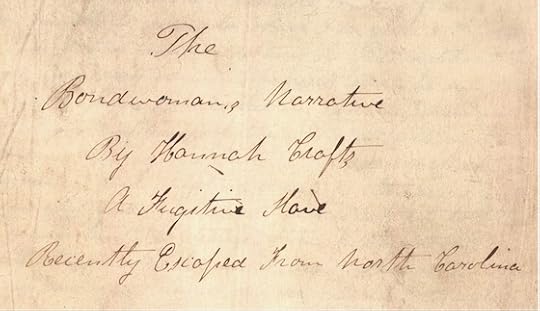

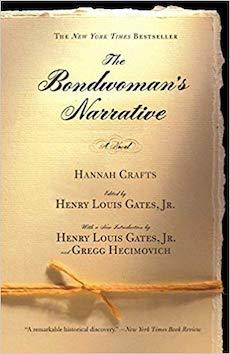

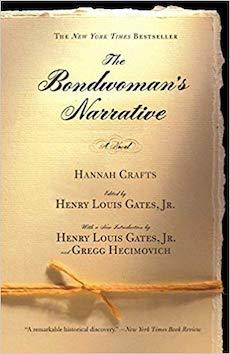

Hannah Bond (aka Hannah Crafts)

Hannah Bond (pen name Hannah Crafts, born 1830s – date of death unknown) escaped slavery around 1857 and settled in New Jersey. Her only known book was The Bondswoman’s Narrative by Hannah Crafts, Fugitive Slave from North Carolina. This autobiographical novel, likely written in the 1850s or 1860s is one of the first novels written by an African-American woman, and uniquely by a fugitive slave.

Not much is known about Hannah’s life, though it has been inferred from details in her novel that she was of mixed race and enslaved in Virginia. The manuscript of The Bondswoman’s Narrative was discovered some one hundred fifty years later by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., authenticated, and published for the first time in 2002. It has been extensively studied and analyzed by professor Gregg Hecimovich of Winthrop University. According to this September 18, 2013 story in the New York Times that uncovered the author’s true identity:

“Beyond simply identifying the author, the professor’s research offers insight into one of the central mysteries of the novel, believed to be semi-autobiographical: how a house slave with limited access to education and books was heavily influenced by the great literature of her time, like Bleak House (Charles Dickens) and Jane Eyre ( Charlotte Brontë ), and how she managed to pull off a daring escape from servitude, disguised as a man.”

Learn more about Hannah Bond / Hannah Crafts and The Bondswoman’s Narrative.

The Bondswoman’s Narrative on Amazon

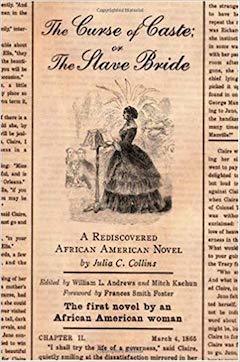

Julia C. Collins

Julia C. Collins (1842 – 1865), believed to have been freeborn, worked as a schoolteacher in Pennsylvania once she reached young adulthood. In 1864, she began to write essays of racial uplift for The Christian Recorder, produced by the African Methodist Episcopal Church. The Curse of Caste, or The Slave Bride was serialized in The Christian Recorder beginning in early 1865. It’s the story of a mixed-race mother and her daughter who encounter barriers to love and opportunity due to slavery and racial bias. Not much is known about Julia Collins’ short life, though apparently, she was well educated.

Unfortunately, she didn’t live to finish her novel, dying of tuberculosis (then called consumption) in late November of 1965. The Curse of Caste, along with Julia’s other writings, were collected and published with analysis and commentary in 2006 by Oxford University Press.

The serialized novel was just reaching its climax as the author lay dying, and was never completed in its own time. The editors of the 2006 volume supplied two alternative endings. Some critics found that to be presumptuous, along with the claim that this was the first published novel by an African-American woman (as it erroneously states on the modern cover, above). Most scholars, including Henry Louis Gates, Jr., agree that Harriet E. Wilson’s Our Nig (1859) and Harriet Ann Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) hold that distinction.

Still, The Curse of Caste is considered a great discovery, a story that in real time explored race and gender issues, interracial love, and oppression in American life. Here’s a review of the 2006 edition in the New York Times.

Read The Curse of Caste online

The Curse of Caste on Amazon

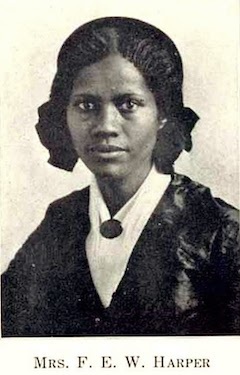

Frances Watkins Harper

Frances Watkins Harper (1825 – 1911) was an ardent suffragist, social reformer, and abolitionist in addition to her renown as a poet and author. She wrote prolifically from the time she published her first collection of poetry in 1845, at the age of twenty. Freeborn in Baltimore, Maryland, she was also known as Frances E. W. Harper and by her full name of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper.

Erlene Stetson, in her 1981 book Black Sister: Poetry by Black American Women, 1746 – 1980, described Frances Harper’s poetry as “stylistically diverse and reverberated with a creative tension between her polite Victorian style and a sociopolitical content concerned with slavery, temperance, and suffrage.”

Frances became active in anti-slavery societies in the early 1850s and was a conductor on the Underground Railroad. She also began lecturing and was widely praised as a compelling public speaker. Her 1854 collection Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects was one her most successful publications. Much later, the novel Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted (1892) was another critical and commercial success.

Her heartbreaking poem “The Slave Mother” is arguably her best known. Here’s a portion:

He is not hers, although she bore

For him a mother’s pains

He is not hers, although her blood

Is coursing through his veins!

He is not hers, for cruel hands

May rudely tear apart

The only wreath of household love

That binds her breaking heart.

Frances Harper published some eighty poems in her lifetime, which, in consideration with her fiction and nonfiction works, should have earned her a prominent place in American literature. Of all the writers listed in this post, she was the one with the most complete literary career. Learn more about her remarkable life.

Read books by Frances Watkins Harper online

Frances Watkins Harper page on Amazon

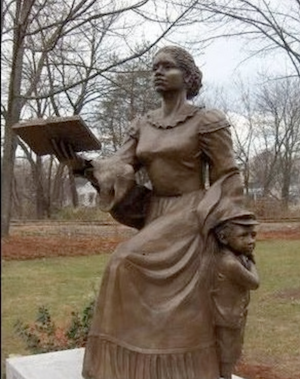

Harriet Ann Jacobs

Harriet Ann Jacobs in 1894

Harriet Ann Jacobs (1813 – 1897) was known for Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself (1861). After repeated rejection, Harriet decided to self-publish the book, an impressive feat for any woman of that era, let alone one that had spent years as a fugitive slave.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is an autobiography, though it reads like a novel. According to the 1987 Harvard University Press edition: “Harriet A. Jacobs was born a slave in North Carolina in 1813 and became a fugitive in the 1830s. She recorded her triumphant struggle for freedom in an autobiography that was published pseudonymously in 1861 … Incidents is the major antebellum autobiography of a black woman. Along with Frederick Douglass’s account of his life, it is one of the two archetypes in the genre of the slave narrative.”

Writing pseudonymously as “Linda Brent,” the book’s narrator, Jacobs recounts the history of her family: a remarkable grandmother who hid her for seven years; a brother who escaped and spoke out for abolition; her two children, who she rescued and sent north. Incidents is also notable for its brutal honesty about the sexual abuse of female slaves. Learn more about Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl and about the remarkable life of Harriet Ann Jacobs.

Read Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl online

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl on Amazon

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley (1818 – 1907), who was born into slavery and later emancipated, became a successful seamstress and social reformer before writing Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House (1868). This autobiography traces her journey from slavery in Virginia and North Carolina to become the seamstress of Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of Abraham Lincoln, during her years as First Lady.

Shortly after she bought her own freedom and that of her son in 1860, she moved to Washington, D.C. and built an impressive dressmaking business, serving the wives of the capital’s elite. Not only did she sew Mrs. Lincoln’s clothing, she also became her close confidante.

Behind the Scenes is an amalgam of first-person slave narrative and tell-all. Elizabeth’s portrait of the First Family sparked a bit of controversy since it broke some rules of privacy. Still, her warm and intimate friendship with Mrs. Lincoln endured. Interestingly, George Saunders’ 2016 novel Lincoln in the Bardo quotes passages from Behind the Scenes.

Elizabeth Keckley may not have been a literary figure per se, but the importance of Behind the Scenes, coupled with her successful dressmaking business as a newly minted member of the black middle class, made her a notable figure worth reconsidering.

Read Behind the Scenes online

Behind the Scenes on Amazon

Harriet E. Wilson

Photo: The Root

Harriet E. Wilson (1825 – 1900) is another figure in the small group of pioneering female African-American female novelists. Born free as Harriet E. Adams in Milford, New Hampshire, she was the mixed-race daughter of an Irish washerwoman and an African-American barrel-hooper. She was orphaned early and worked for several years as an indentured servant. Released from servitude at age eighteen, she struggled to make a living. She married twice, was widowed, and endured many hardships.

Her novel Our Nig, or Sketches from the Life of a Free Black was published anonymously in 1859 by a Boston publisher. Her motivation for writing the novel was to raise money to care for her young son, who was ill. This battle was lost, as little George died in the poorhouse in which she had boarded him, at age seven.

Our Nig didn’t make a splash when first published, and remained obscure until it was rediscovered by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. in 1982. It’s considered one of the first novels published by an African-American author. It remained Harriet Wilson’s only novel. After her child’s death, she went on the public lecture circuit to speak about her life. Gates called Our Nig “a complex response to Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

Read Our Nig on Project Gutenberg

Our Nig by Harriet E. Wilson on Amazon

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 6 Fascinating African-American Women Writers of the 19th Century appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

6 Fascinating African-American Women Writers of the 19th-Century

Given the circumstances of African-American life in the 19th century both before and after emancipation, women of color who took up the pen to write full books were rare indeed. It’s worth noting that before the Civil War, it was illegal to teach African-Americans to read in many states, not just in the South.

Not surprisingly, most of the books, essays, and poetry they produced by African-American women writers dealt with slavery. For a black woman to produce a novel or autobiography was a rare and radical act. Most of the autobiographies and thinly veiled novels discussed here were in the genre of slave narrative.

Lest you think we’ve forgotten Phillis Wheatley — the first African-American female poet to be published, and one of the first women of any background to be published in the colonies — we haven’t. She’s not included in this list because she lived and wrote exclusively in the 18th century. Here are six fascinating 19th-century African-American women writers whose talent and daring are ripe for rediscovery.

Hannah Bond (aka Hannah Crafts)

Hannah Bond (pen name Hannah Crafts, born 1830s – date of death unknown) escaped slavery around 1857 and settled in New Jersey. Her only known book wasThe Bondswoman’s Narrative by Hannah Crafts, Fugitive Slave from North Carolina. This autobiographical novel, likely written in the 1850s or 1860s is one of the first novels written by an African-American woman, and uniquely by a fugitive slave.

Not much is known about Hannah’s life, though it has been inferred from details in her novel that she was of mixed race and enslaved in Virginia. The manuscript of The Bondswoman’s Narrative was discovered some one hundred fifty years later by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., authenticated, and published for the first time in 2002. It has been extensively studied and analyzed by professor Gregg Hecimovich of Winthrop University. According to this September 18, 2013 story in the New York Times that uncovered the author’s true identity:

“Beyond simply identifying the author, the professor’s research offers insight into one of the central mysteries of the novel, believed to be semi-autobiographical: how a house slave with limited access to education and books was heavily influenced by the great literature of her time, like Bleak House (Charles Dickens) and Jane Eyre ( Charlotte Brontë ), and how she managed to pull off a daring escape from servitude, disguised as a man.”

Learn more about Hannah Bond / Hannah Crafts and The Bondswoman’s Narrative.

The Bondswoman’s Narrative on Amazon

Julia C. Collins

Julia C. Collins (1842 – 1865), believed to have been freeborn, worked as a schoolteacher in Pennsylvania once she reached young adulthood. In 1864, she began to write essays of racial uplift for The Christian Recorder, produced by the African Methodist Episcopal Church. The Curse of Caste, or The Slave Bride was serialized in The Christian Recorder beginning in early 1865. It’s the story of a mixed-race mother and her daughter who encounter barriers to love and opportunity due to slavery and racial bias. Not much is known about Julia Collins’ short life, though apparently, she was well educated.

Unfortunately, she didn’t live to finish her novel, dying of tuberculosis (then called consumption) in late November of 1965. The Curse of Caste, along with Julia’s other writings, were collected and published with analysis and commentary in 2006 by Oxford University Press.

The serialized novel was just reaching its climax as the author lay dying, and was never completed in its own time. The editors of the 2006 volume supplied two alternative endings. Some critics found that to be presumptuous, along with the claim that this was the first published novel by an African-American woman (as it erroneously states on the modern cover, above). Most scholars, including Henry Louis Gates, Jr., agree that Harriet E. Wilson’s Our Nig (1859) and Harriet Ann Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) hold that distinction.

Still, The Curse of Caste is considered a great discovery, a story that in real time explored race and gender issues, interracial love, and oppression in American life. Here’s a review of the 2006 edition in the New York Times.

Read The Curse of Caste online

The Curse of Caste on Amazon

Frances Watkins Harper

Frances Watkins Harper (1825 – 1911) was an ardent suffragist, social reformer, and abolitionist in addition to her renown as a poet and author. She wrote prolifically from the time she published her first collection of poetry in 1845, at the age of twenty. Freeborn in Baltimore, Maryland, she was also known as Frances E. W. Harper and by her full name of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper.

Erlene Stetson, in her 1981 book Black Sister: Poetry by Black American Women, 1746 – 1980, described Frances Harper’s poetry as “stylistically diverse and reverberated with a creative tension between her polite Victorian style and a sociopolitical content concerned with slavery, temperance, and suffrage.”

Frances became active in anti-slavery societies in the early 1850s and was a conductor on the Underground Railroad. She also began lecturing and was widely praised as a compelling public speaker. Her 1854 collection Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects was one her most successful publications. Much later, the novel Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted (1892) was another critical and commercial success.

Her heartbreaking poem “The Slave Mother” is arguably her best known. Here’s a portion:

He is not hers, although she bore

For him a mother’s pains

He is not hers, although her blood

Is coursing through his veins!

He is not hers, for cruel hands

May rudely tear apart

The only wreath of household love

That binds her breaking heart.

Frances Harper published some eighty poems in her lifetime, which, in consideration with her fiction and nonfiction works, should have earned her a prominent place in American literature. Of all the writers listed in this post, she was the one with the most complete literary career. Learn more about her remarkable life.

Read books by Frances Watkins Harper online

Frances Watkins Harper page on Amazon

Harriet Ann Jacobs

Harriet Ann Jacobs in 1894

Harriet Ann Jacobs (1813 – 1897) was known for Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself (1861). After repeated rejection, Harriet decided to self-publish the book, an impressive feat for any woman of that era, let alone one that had spent years as a fugitive slave.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is an autobiography, though it reads like a novel. According to the 1987 Harvard University Press edition: “Harriet A. Jacobs was born a slave in North Carolina in 1813 and became a fugitive in the 1830s. She recorded her triumphant struggle for freedom in an autobiography that was published pseudonymously in 1861 … Incidents is the major antebellum autobiography of a black woman. Along with Frederick Douglass’s account of his life, it is one of the two archetypes in the genre of the slave narrative.”

Writing pseudonymously as “Linda Brent,” the book’s narrator, Jacobs recounts the history of her family: a remarkable grandmother who hid her for seven years; a brother who escaped and spoke out for abolition; her two children, who she rescued and sent north. Incidents is also notable for its brutal honesty about the sexual abuse of female slaves. Learn more about Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl and about the remarkable life of Harriet Ann Jacobs.

Read Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl online

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl on Amazon

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley (1818 – 1907), who was born into slavery and later emancipated, became a successful seamstress and social reformer before writing Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House (1868). This autobiography traces her journey from slavery in Virginia and North Carolina to become the seamstress of Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of Abraham Lincoln, during her years as First Lady.

Shortly after she bought her own freedom and that of her son in 1860, she moved to Washington, D.C. and built an impressive dressmaking business, serving the wives of the capital’s elite. Not only did she sew Mrs. Lincoln’s clothing, she also became her close confidante.

Behind the Scenes is an amalgam of first-person slave narrative and tell-all. Elizabeth’s portrait of the First Family sparked a bit of controversy since it broke some rules of privacy. Still, her warm and intimate friendship with Mrs. Lincoln endured. Interestingly, George Saunders’ 2016 novel Lincoln in the Bardo quotes passages from Behind the Scenes.

Elizabeth Keckley may not have been a literary figure per se, but the importance of Behind the Scenes, coupled with her successful dressmaking business as a newly minted member of the black middle class, made her a notable figure worth reconsidering.

Read Behind the Scenes online

Behind the Scenes on Amazon

Harriet E. Wilson

Photo: The Root

Harriet E. Wilson (1825 – 1900) is another figure in the small group of pioneering female African-American female novelists. Born free as Harriet E. Adams in Milford, New Hampshire, she was the mixed-race daughter of an Irish washerwoman and an African-American barrel-hooper. She was orphaned early and worked for several years as an indentured servant. Released from servitude at age eighteen, she struggled to make a living. She married twice, was widowed, and endured many hardships.

Her novel Our Nig, or Sketches from the Life of a Free Black was published anonymously in 1859 by a Boston publisher. Her motivation for writing the novel was to raise money to care for her young son, who was ill. This battle was lost, as little George died in the poorhouse in which she had boarded him, at age seven.

Our Nig didn’t make a splash when first published, and remained obscure until it was rediscovered by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. in 1982. It’s considered one of the first novels published by an African-American author. It remained Harriet Wilson’s only novel. After her child’s death, she went on the public lecture circuit to speak about her life. Gates called Our Nig “a complex response to Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

Read Our Nig on Project Gutenberg

Our Nig by Harriet E. Wilson on Amazon

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 6 Fascinating African-American Women Writers of the 19th-Century appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 17, 2018

A Selection of Poems by Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1875 – 1935; also known as Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson) was a multitalented writer, poet, journalist, and teacher. She used her writings to advocate for the rights of women and African-Americans and was considered one of the premier poets of the Harlem Renaissance.

In addition to her highly regarded poetry, Alice was known for her short stories and searingly honest essays, in which she expressed the challenges of growing up mixed-race in Louisiana. Her heritage of African-American, Creole, European, and Native American gave her a broad perspective on race, which she explored along with the varied and complex issues faced by women of color.

Violets and Other Tales, her first book, was a compilation of poetry, essays, and short stories. She was twenty at the time of its publication in 1895. As her reputation as a writer grew, she wrote of sexism, racism, work, sexuality, and family in the various genres in which she wrote. Here is a selection of poems by Alice Dunbar-Nelson, from Violets and Other Tales as well as publications and anthologies of the early 1920s.

A Plaint

Dear God, ’tis hard, so awful hard to lose

The one we love, and see him go afar,

With scarce one thought of aching hearts behind,

Nor wistful eyes, nor outstretched yearning hands.

Chide not, dear God, if surging thoughts arise.

And bitter questionings of love and fate,

But rather give my weary heart thy rest,

And turn the sad, dark memories into sweet.

Dear God, I fain my loved one were anear,

But since thou will’st that happy thence he’ll be,

I send him forth, and back I’ll choke the grief

Rebellious rises in my lonely heart.

I pray thee, God, my loved one joy to bring;

I dare not hope that joy will be with me,

But ah, dear God, one boon I crave of thee,

That he shall ne’er forget his hours with me.

(from Violets and Other Tales, 1895)

See also: Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance to Rediscover and Read

Amid the Roses

There is tropical warmth and languorous life

Where the roses lie

In a tempting drift

Of pink and red and golden light

Untouched as yet by the pruning knife.

And the still, warm life of the roses fair

That whisper “Come,”

With promises

Of sweet caresses, close and pure

Has a thorny whiff in the perfumed air.

There are thorns and love in the roses’ bed,

And Satan too

Must linger there;

So Satan’s wiles and the conscience stings,

Must now abide—the roses are dead.

(from Violets and Other Tales, 1895)

If I Had Known

If I had known

Two years ago how drear this life should be,

And crowd upon itself all strangely sad,

Mayhap another song would burst from out my lips,

Overflowing with the happiness of future hopes;

Mayhap another throb than that of joy.

Have stirred my soul into its inmost depths,

If I had known.

If I had known,

Two years ago the impotence of love,

The vainness of a kiss, how barren a caress,

Mayhap my soul to higher things have soarn,

Nor clung to earthly loves and tender dreams,

But ever up aloft into the blue empyrean,

And there to master all the world of mind,

If I had known.

(from Violets and Other Tales, 1895)

I Sit and Sew

I sit and sew—a useless task it seems,

The panoply of war, the martial tred of men,

Grim-faced, stern-eyed, gazing beyond the ken

My hands grown tired, my head weighed down with dreams—

Of lesser souls, whose eyes have not seen Death,

Nor learned to hold their lives but as a breath—

But—I must sit and sew.

I sit and sew—my heart aches with desire—

That pageant terrible, that fiercely pouring fire

On wasted fields, and writhing grotesque things

Once men. My soul in pity flings

Appealing cries, yearning only to go

There in that holocaust of hell, those fields of woe—

But—I must sit and sew.

The little useless seam, the idle patch;

Why dream I here beneath my homely thatch,

When there they lie in sodden mud and rain,

Pitifully calling me, the quick ones and the slain?

You need me, Christ! It is no roseate dream

That beckons me—this pretty futile seam,

It stifles me—God, must I sit and sew?

(first published in the AME Church Review in1918, “I Sit and Sew” is one of Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s most anthologized poems.

Here are several analyses of “I Sit and Sew”)

You might also enjoy

Renaissance Women: 12 Women Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

To Madame Curie

Oft have I thrilled at deeds of high emprise,

And yearned to venture into realms unknown,

Thrice blessed she, I deemed, whom God had shown

How to achieve great deeds in woman’s guise.

Yet what discov’ry by expectant eyes

Of foreign shores, could vision half the throne

Full gained by her, whose power fully grown

Exceeds the conquerors of th’ uncharted skies?

So would I be this woman whom the world

Avows its benefactor; nobler far,

Than Sybil, Joan, Sappho, or Egypt’s queen.

In the alembic forged her shafts and hurled

At pain, diseases, waging a humane war;

Greater than this achievement, none, I ween.

(first published in The Philadelphia Public Ledger, August 21, 1921)

You! Inez!

Orange gleams athwart a crimson soul

Lambent flames; purple passion lurks

In your dusk eyes.

Red mouth; flower soft,

Your soul leaps up—and flashes

Star-like, white, flame-hot.

Curving arms, encircling a world of love,

You! Stirring the depths of passionate desire!

(from a Holograph manuscript, February 16, 1921)

Sonnet

I had not thought of violets late,

The wild, shy kind that spring beneath your feet

In wistful April days, when lovers mate

And wander through the fields in raptures sweet.

The thought of violets meant florists’ shops,

And bows and pins, and perfumed papers fine;

And garish lights, and mincing little fops

And cabarets and soaps, and deadening wines.

So far from sweet real things my thoughts had strayed,

I had forgot wide fields; and clear brown streams;

The perfect loveliness that God has made,—

Wild violets shy and Heaven-mounting dreams.

And now—unwittingly, you’ve made me dream

Of violets, and my soul’s forgotten gleam.

(from The Book of American Negro Poetry, 1922)

An excellent resource is Shadowed Dreams: Women’s Poetry of the Harlem Renaissance,

edited by Maureen Honey (Rutgers University Press, 1989)

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post A Selection of Poems by Alice Dunbar-Nelson appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 14, 2018

4 Book Towns in North America

Whether you call it a Boekenstad, Village du Livres, Bokby or Bókabæirnir, from Canada to Korea and from Iceland to Australia a movement is growing. In hamlets, villages and towns around the world, like-minded booksellers, calligraphers, bookbinders, curators, publishers, and architects are coming together to ensure a future for the printed book, defying the e-book onslaught, and providing a new future for fading communities.

This post is excerpted and adapted from Book Towns: Forty-Five Paradises of the Printed Word by Alex Johnson (© 2018, Quarto Publishing, plc, by permission). It’s the first book to bring all of these towns together, offering a unique history of each one, and encouraging readers to seek them out. By visiting these towns you are not only helping to save the printed book; you are helping to keep communities alive. Above right, Mysteries and More in Hobart, NY, guarded by shop cat Big Red.

Book Towns by Alex Johnson on Amazon

A book town is simply a small town, usually rural and scenic, full of bookshops and book-related industries. The movement started with Richard Booth in Hay-on-Wye in Wales in the 1960s, picked up speed in the 1980s and is continuing to thrive in the new millennium. From the start, the driving force has been to encourage sustainable tourism and help regenerate communities faced with economic collapse and soaring unemployment.

One important reason that almost all book towns are in bucolic locations is that they require cheap property to enable book businesses to open their doors. Many have been subsidized by local authorities to help them get off the ground. While many cities have numerous bookshops, book towns concentrate the outlets in a small area to create a critical mass.

The Gold Cities (Grass Valley and Nevada City)

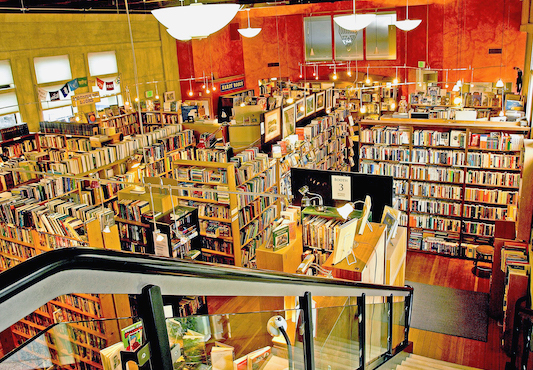

Booktown books, a cooperative bookselling space housed in an old Salvation Army regional office

The Gold Cities in California actually cover two main locations, Grass Valley and (four miles to the north) Nevada City, with satellite sellers in nearby Penn Valley, North San Juan, and Lake of the Pines. In Nevada City, there’s Toad Hall Books (N Pine Street). Hardy Books, open by appointment only, specializes in Western Americana and ‘All Things Californian,’ much of which is not included in its online inventory.

Jenny’s Paper & Ink Books (Joerschke Drive) offers preowned delights in Grass Valley, which is also home to Booktown Books, a co-operative venture established by a group of book dealers in 1998. The project has gradually expanded, and since 2005 has operated from a two-story, 4,000 square foot building. Each bookseller has their own booth space and displays their chosen genres of books – military history, esoteric, graphic novels, or simply general — as well as book ephemera, DVDs, CDs and vinyl records. Bud Plant and Hutchison Books, for example, specializes in fine illustrated and children’s books.

More information: Booktown Books

Hobart Book Village, Hobart, NY

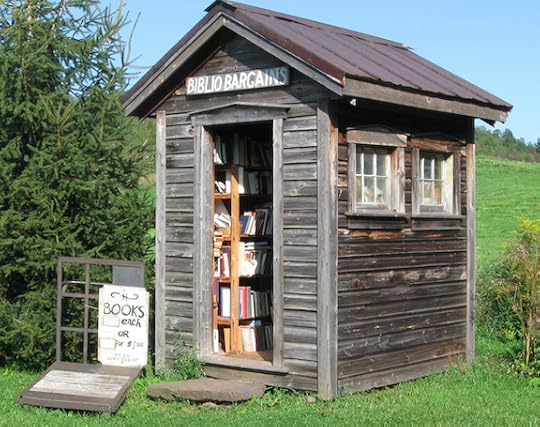

One of the smallest bookshops to be found in any book town | Photo by Mark M. Rogers

Hobart Book Village owes a huge debt to one man. The small town of around 400 residents, in a picturesque rural location in the northern Catskills, now has six bookshops all very close to each other on Main Street, and was awarded the Delaware County Chamber of Commerce Tourism Award in 2016. This is all thanks to musician Don Dales, who in 1999 decided that the many empty shops at the time could provide the raw ingredients to make a thriving book town.

He bought up various premises and offered them to new businesses on tiny rents, sometimes even for free. He was soon joined by Diana and Bill Adams, who run WM. H. Adams Antiquarian Bookshop, specializing in pre-nineteenth-century and classical titles. It spreads over three floors and has an attractive deck overlooking the Delaware river. The bookshop is also the venue for the annual Winter Respite Lecture Series.

Don now runs the Mysteries & More Crime Café in a Greek Revival house dating back to the 1830s with a good stock of mystery, detective, and science fiction titles as well as homemade snacks.

The newest arrival is Kathy and George Duyer’s Creative Corner Books, which concentrates on cookery and craft books but also organizes cookery demonstrations, knitting clinics, and workshops on the premises, as well as stocking locally-produced farm products.

A good example of how things have changed is Liberty Rock Books, which was built in the early 1920s and was formerly an auto garage and propane distributor. Now the 5,000-square-foot space with exposed beams is full of books, including Native American works, plus jazz records and CDs, and vintage postcards. Other bookshops include Butternut Valley Books, which stocks a good range of local and global maps, fine art prints and bookends, as well as books in a variety of languages.

More information: Hobart Book Village

Sidney, Vancouver Island (Canada)

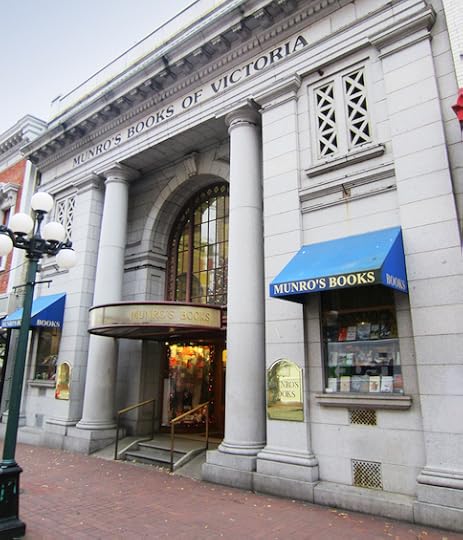

Munro’s Books in Victoria, established by acclaimed short story writer Alice Munro,

is just a short drive from Sidney

Sidney on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, is Canada’s only book town, established in 1996. Its pleasant seaside location makes it very popular with fishermen, and its population of 12,000 has a particularly high percentage of retirees.

Sidney’s half-dozen secondhand bookshops (numbers have halved over the last few years but those that remain are still going strong) are clustered along Beacon Avenue. The street is home to the eponymous Beacon Books which offers a wide general stock as well as modern first editions and antiquarian titles, while a whole room is devoted to ‘country living’ titles. Galleon Books and Antiques is a non-fiction specialist, especially good on regional Canadian history and First Nation titles, as well as selling antiques and other collectibles.

As you would guess, The Military & History Bookshop, just off of Beacon Avenue on Fourth Street, is a military specialist, strong on the two world wars and Churchilliana. The Children’s Bookshop caters for all youngsters from toddlers to young adults.

Tanner’s is where the book town really started, when Clive and Christine Tanner opened their first bookshop here, now selling only new books. It also sells an incredibly wide range of magazines and newspapers from Canada, the USA and the UK, as well as many maps and nautical charts.

The Haunted Bookshop is named after Christopher Morley’s 1919 novel of the same name (a bookshop-themed mystery tale rather than a supernatural whodunnit) and is Vancouver Island’s oldest antiquarian bookshop with appropriately classic bookshelves. Established originally in Victoria in 1947 and run by Odean Long, it has an excellent children’s classics section and also sells book ephemera, maps and prints.

More information: Sidney Book Town

You might also enjoy: Books for Book Lovers

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 4 Book Towns in North America appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 12, 2018

Books for Book Lovers: Bookshops, Libraries, Reading, & Bibliomania

For bibliophiles, it’s not enough to be so obsessed with books that we’re reading four or five works of fiction or nonfiction at any given time. We also love books about books, bookstores, libraries, bookish places, and even books about reading. This might seem eccentric at first glance, but for the devout book lover, it makes perfect sense.