Nava Atlas's Blog, page 79

October 9, 2018

“Désirée’s Baby” — a Short Story by Kate Chopin (1893)

“Désirée’s Baby” is an 1893 short story by Kate Chopin. As its theme, the bold and unconventional American author best know for the classic novella The Awakening explores the hypocrisy, racism, and sexism in upper crust Creole Louisiana. First published in the January 1893 issue of Vogue magazine as “The Father of Désirée’s Baby,” it was included in Bayou Folk, a short story collection by Chopin published the following year.

In this fairly brief short story, Chopin explored themes that ran through her works, including women’s struggle for equality and the vagaries of identity. Abandoned as a baby, Désirée is the adopted daughter of Monsieur and Madame Valmondé, wealthy French Creoles. When she reaches young womanhood she marries Armand, the son of another wealthy French Creole family.

When the couple have a baby, it’s apparent that he’s mixed race, with the coloring of what was then called a “quadroon” — a person that is one-quarter black. Because Désirée’s parentage is not known, Armand assumes that she’s part black and rejects both her and his baby son, compelling them to leave the estate. She does so, taking the baby, and walks off into the bayou. It’s not clear whether she has run off, or takes her own life and that of her baby.

Armand soon discovers in a letter from his mother to his father that it is actually he who is part black, but it’s too late. With the hypocrisy revealed, his identity shaken, he has forever lost his wife and child.

Full text of “Désirée’s Baby”

As the day was pleasant, Madame Valmondé drove over to L’Abri to see Désirée and the baby.

It made her laugh to think of Désirée with a baby. Why, it seemed but yesterday that Désirée was little more than a baby herself; when Monsieur in riding through the gateway of Valmondé had found her lying asleep in the shadow of the big stone pillar.

The little one awoke in his arms and began to cry for “Dada.” That was as much as she could do or say. Some people thought she might have strayed there of her own accord, for she was of the toddling age. The prevailing belief was that she had been purposely left by a party of Texans, whose canvas-covered wagon, late in the day, had crossed the ferry that Coton Maïs kept, just below the plantation. In time Madame Valmondé abandoned every speculation but the one that Désirée had been sent to her by a beneficent Providence to be the child of her affection, seeing that she was without child of the flesh. For the girl grew to be beautiful and gentle, affectionate and sincere—the idol of Valmondé.

It was no wonder, when she stood one day against the stone pillar in whose shadow she had lain asleep, eighteen years before, that Armand Aubigny riding by and seeing her there, had fallen in love with her. That was the way all the Aubignys fell in love, as if struck by a pistol shot. The wonder was that he had not loved her before; for he had known her since his father brought him home from Paris, a boy of eight, after his mother died there. The passion that awoke in him that day, when he saw her at the gate, swept along like an avalanche, or like a prairie fire, or like anything that drives headlong over all obstacles.

Monsieur Valmondé grew practical and wanted things well considered: that is, the girl’s obscure origin. Armand looked into her eyes and did not care. He was reminded that she was nameless. What did it matter about a name when he could give her one of the oldest and proudest in Louisiana? He ordered the corbeille from Paris, and contained himself with what patience he could until it arrived; then they were married.

Madame Valmondé had not seen Désirée and the baby for four weeks. When she reached L’Abri she shuddered at the first sight of it, as she always did. It was a sad looking place, which for many years had not known the gentle presence of a mistress, old Monsieur Aubigny having married and buried his wife in France, and she having loved her own land too well ever to leave it. The roof came down steep and black like a cowl, reaching out beyond the wide galleries that encircled the yellow stuccoed house. Big, solemn oaks grew close to it, and their thick-leaved, far-reaching branches shadowed it like a pall. Young Aubigny’s rule was a strict one, too, and under it his negroes had forgotten how to be gay, as they had been during the old master’s easy-going and indulgent lifetime.

You might also enjoy:

Full text of The Awakening (1899) by Kate Chopin

The young mother was recovering slowly, and lay full length, in her soft white muslins and laces, upon a couch. The baby was beside her, upon her arm, where he had fallen asleep, at her breast. The yellow nurse woman sat beside a window fanning herself.

Madame Valmondé bent her portly figure over Désirée and kissed her, holding her an instant tenderly in her arms. Then she turned to the child.

“This is not the baby!” she exclaimed, in startled tones. French was the language spoken at Valmondé in those days.

“I knew you would be astonished,” laughed Désirée, “at the way he has grown. The little cochon de lait! Look at his legs, mamma, and his hands and finger-nails —real finger-nails. Zandrine had to cut them this morning. Isn’t it true, Zandrine?”

The woman bowed her turbaned head majestically, “Mais si, Madame.”

“And the way he cries,” went on Désirée, “is deafening. Armand heard him the other day as far away as La Blanche’s cabin.”

Madame Valmondé had never removed her eyes from the child. She lifted it and walked with it over to the window that was lightest. She scanned the baby narrowly, then looked as searchingly at Zandrine, whose face was burned to gaze across the fields.

“Yes, the child has grown, has changed;” said Madame Valmondé, slowly, as she replaced it beside its mother. “What does Armand say?”

Désirée’s face became suffused with a glow that was happiness itself.

“Oh, Armand is the proudest father in the parish, I believe, chiefly because it is a boy, to bear his name; though he says not — that he would have loved a girl as well. But I know it isn’t true. I know he says that to please me. And mamma,” she added, drawing Madame Valmondé’s head down to her, and speaking in a whisper, “he hasn’t punished one of them — not one of them — since baby is born. Even Négrillon, who pretended to have burnt his leg that he might rest from work — he only, laughed, and said Négrillon was a great scamp. Oh, mamma, I’m so happy; it frightens me.”

What Désirée said was true. Marriage, and later the birth of his son, had softened Armand Aubigny’s imperious and exacting nature greatly. This was what made the gentle Désirée so happy, for she loved him desperately. When he frowned she trembled, but loved him. When he smiled, she asked no greater blessing of God. But Armand’s dark, handsome face had not often been disfigured by frowns since the day he fell in love with her.

When the baby was about three months old, Désirée awoke one day to the conviction that there was something in the air menacing her peace. It was at first too subtle to grasp. It had only been a disquieting suggestion; an air of mystery among the blacks; unexpected visits from far-off neighbors who could hardly account for their coming. Then a strange, an awful change in her husband’s manner, which she dared not ask him to explain. When he spoke to her, it was with averted eyes, from which the old love-light seemed to have gone out. He absented himself from home; and when there, avoided her presence and that of her child, without excuse. And the very spirit of Satan seemed suddenly to take hold of him in his dealings with the slaves. Désirée was miserable enough to die.

She sat in her room, one hot afternoon, in her peignoir, listlessly drawing through her fingers the strands of her long, silky brown hair that hung about her shoulders. The baby, half naked, lay asleep upon her own great mahogany bed, that was like a sumptuous throne, with its satin-lined half-canopy. One of La Blanche’s little quadroon boys—half naked too—stood fanning the child slowly with a fan of peacock feathers. Désirée’s eyes had been fixed absently and sadly upon the baby, while she was striving to penetrate the threatening mist that she felt closing about her. She looked from her child to the boy who stood beside him, and back again; over and over. “Ah!” It was a cry that she could not help; which she was not conscious of having uttered. The blood turned like ice in her veins, and a clammy moisture gathered upon her face.

She tried to speak to the little quadroon boy; but no sound would come, at first. When he heard his name uttered, he looked up, and his mistress was pointing to the door. He laid aside the great, soft fan, and obediently stole away, over the polished floor, on his bare tiptoes.

She stayed motionless, with gaze riveted upon her child, and her face the picture of fright.

Presently her husband entered the room, and without noticing her, went to a table and began to search among some papers which covered it.

“Armand,” she called to him, in a voice which must have stabbed him, if he was human. But he did not notice. “Armand,” she said again. Then she rose and tottered towards him. “Armand,” she panted once more, clutching his arm, “look at our child. What does it mean? tell me.”

He coldly but gently loosened her fingers from about his arm and thrust the hand away from him. “Tell me what it means!” she cried despairingly.

“It means,” he answered lightly, “that the child is not white; it means that you are not white.”

A quick conception of all that this accusation meant for her nerved her with unwonted courage to deny it. “It is a lie; it is not true, I am white! Look at my hair, it is brown; and my eyes are gray, Armand, you know they are gray. And my skin is fair,” seizing his wrist. “Look at my hand; whiter than yours, Armand,” she laughed hysterically.

“As white as La Blanche’s,” he returned cruelly; and went away leaving her alone with their child.

When she could hold a pen in her hand, she sent a despairing letter to Madame Valmondé.

“My mother, they tell me I am not white. Armand has told me I am not white. For God’s sake tell them it is not true. You must know it is not true. I shall die. I must die. I cannot be so unhappy, and live.”

The answer that came was as brief:

“My own Désirée: Come home to Valmondé; back to your mother who loves you. Come with your child.”

When the letter reached Désirée she went with it to her husband’s study, and laid it open upon the desk before which he sat. She was like a stone image: silent, white, motionless after she placed it there.

In silence he ran his cold eyes over the written words. He said nothing. “Shall I go, Armand?” she asked in tones sharp with agonized suspense.

“Yes, go.”

“Do you want me to go?”

“Yes, I want you to go.”

He thought Almighty God had dealt cruelly and unjustly with him; and felt, somehow, that he was paying Him back in kind when he stabbed thus into his wife’s soul. Moreover he no longer loved her, because of the unconscious injury she had brought upon his home and his name.

She turned away like one stunned by a blow, and walked slowly towards the door, hoping he would call her back.

“Good-by, Armand,” she moaned.

He did not answer her. That was his last blow at fate.

Désirée went in search of her child. Zandrine was pacing the sombre gallery with it. She took the little one from the nurse’s arms with no word of explanation, and descending the steps, walked away, under the live-oak branches.

It was an October afternoon; the sun was just sinking. Out in the still fields the negroes were picking cotton.

Bayou Folk on Amazon

Désirée had not changed the thin white garment nor the slippers which she wore. Her hair was uncovered and the sun’s rays brought a golden gleam from its brown meshes. She did not take the broad, beaten road which led to the far-off plantation of Valmondé. She walked across a deserted field, where the stubble bruised her tender feet, so delicately shod, and tore her thin gown to shreds.

She disappeared among the reeds and willows that grew thick along the banks of the deep, sluggish bayou; and she did not come back again.

Some weeks later there was a curious scene enacted at L’Abri. In the centre of the smoothly swept back yard was a great bonfire. Armand Aubigny sat in the wide hall-way that commanded a view of the spectacle; and it was he who dealt out to a half dozen negroes the material which kept this fire ablaze.

A graceful cradle of willow, with all its dainty furbishings, was laid upon the pyre, which had already been fed with the richness of a priceless layette. Then there were silk gowns, and velvet and satin ones added to these; laces, too, and embroideries; bonnets and gloves; for the corbeille had been of rare quality.

The last thing to go was a tiny bundle of letters; innocent little scribblings that Désirée had sent to him during the days of their espousal. There was the remnant of one back in the drawer from which he took them. But it was not Désirée’s; it was part of an old letter from his mother to his father. He read it. She was thanking God for the blessing of her husband’s love:

“But, above all,” she wrote, “night and day, I thank the good God for having so arranged our lives that our dear Armand will never know that his mother, who adores him, belongs to the race that is cursed with the brand of slavery.”

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post “Désirée’s Baby” — a Short Story by Kate Chopin (1893) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 7, 2018

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Ann Jacobs: An Introduction

In 1857, Harriet Ann Jacobs (February 11, 1813 – March 7, 1897) was completing a manuscript for a fictionalized account of her life as a slave, and of her struggle to free herself and her children. After all she’d been through, no publisher would take the book on. After repeated rejections, Harriet decided to publish the book herself, an impressive feat for any woman of that era, let alone one that had spent years as a fugitive slave. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself, was published in 1861.

Though Incidents is autobiography, it reads like a novel, with a narrator named Linda Brent. But Jacobs wanted to make sure that readers understood that the book was wholly based on her own experiences. In the Preface to the book she wrote:

“Reader, be assured this narrative is no fiction. I am aware that some of my adventures may seem incredible; but they are, nevertheless, strictly true. I have not exaggerated the wrongs inflicted by Slavery; on the contrary, my descriptions fall far short of the facts. I have concealed the names of places, and given persons fictitious names. I had no motive for secrecy on my own account, but I deemed it kind and considerate towards others to pursue this course …”

What compelled Jacobs to write the book

Jacobs sums up her motivation to write Incidents in her author’s Preface:

“I have not written my experiences in order to attract attention to myself; on the contrary, it would have been more pleasant to me to have been silent about my own history. Neither do I care to excite sympathy for my own sufferings. But I do earnestly desire to arouse the women of the North to a realizing sense of the condition of two million women at the South, still in bondage, suffering what I suffered, and most of them far worse …

I want to add my testimony to that of abler pens to convince the people of the Free States what Slavery really is. Only by experience can any one realize how deep and dark, and foul is that pit of abominations. May the blessing of God rest on this imperfect effort in behalf of my persecuted people!”

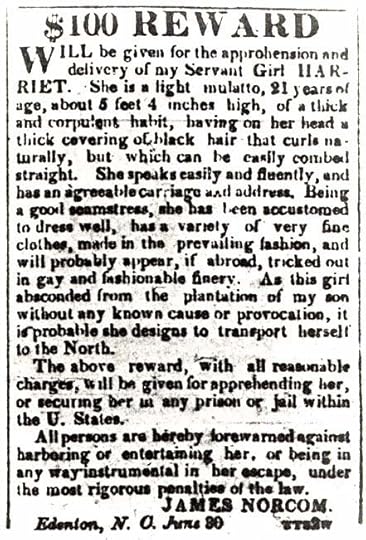

Runaway slave advertisement for Harriet

A brief summary of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is encapsulated in the 1987 Harvard University Press edition:

Harriet A. Jacobs was born a slave in North Carolina in 1813 and became a fugitive in the 1830s She recorded her triumphant struggle for freedom in an autobiography that was published pseudonymously in 1861.

As Linda Brent the book’s heroine and narrator, Jacobs recounts the history of her family: a remarkable grandmother who hid her from her master for seven years; a brother who escaped and spoke out for abolition; her two children, whom she rescued and sent north.

She recalls the degradation of slavery and the special sexual oppression she found as a slave woman: the master who was determined to make her his concubine, his jealous wife, the future congressman who fathered her children but broke his promise to set them free, and sympathetic whites: a slave mistress who sheltered her; the northern woman who employed her, helped her avoid capture, and eventually bought her freedom; the abolitionist-feminism friend who encouraged her to write her autobiography; and Lydia Maria Child, the well-known writer who donated her services as an editor.

Incidents is the major antebellum autobiography of a black woman. With Frederick Douglass’s account of his life, it is one of the two archetypes in the genre of the slave narrative.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl on Amazon

The original editor’s note

Lydia Maria Child wrote in her introduction to Incidents:

“I believe those who know her will not be disposed to doubt her veracity, though some incidents in the story are more romantic than fiction. At her request, I have revised her manuscript; but such changes as I have made have been mainly for purposes of condensation and orderly arrangement. I have not added any thing to the incidents, or changed the import of her very pertinent remarks. With trifling exceptions, both the ideas and the language are her own.”

The frankness of Jacobs’ description of the sexual abuse and rape of female slaves were rare indeed for that time period, and Mrs. Child frames it diplomatically:

“I am well aware that many will accuse me of indecorum for presenting these pages to the public; for the experiences of this intelligent and much-injured woman belong to a class which some call delicate subjects; and others indelicate. This peculiar phase of Slavery has generally been kept veiled; but the public ought to be made acquainted with its monstrous features and I willingly take the responsibility of presenting them with the veil withdrawn.”

A contemporary introduction

Here, a portion from the introduction to the 1987 edition (Harvard University Press) by Jean Fagan Yellin:

“Like all slave narratives, Incidents was shaped by the empowering impulse that created the American Renaissance. Jacobs’ book expressed democratic ideals and embodied a dual critique of nineteenth-century America: it challenged the institution of chattel slavery with its supporting ideology of white racism, as well as traditional patriarchal institutions and ideologies.

Jacobs’ achievement was the transformation of herself into a literary subject throughout the creation of her narrator, Linda Brent. This narrator tells a double tale, dramatizing the triumph of her efforts to prevent her master from raping her, to arrange for her children’s rescue from him, to hide, to escaped and finally to achieve freedom; and simultaneously presenting her failure to adhere to sexual standards in which she believed.

Unmarried, she entered into a sexual liaison, became pregnant, was condemned by her grandmother, and suffered terrible guilt. She writes that still, in middle age, she feels her youthful distress. But she also questions the condemnation of her behavior, reaching toward an alternative judgment, she suggested that the sexual standards mandated for free women were not relevant to women held in slavery

Further, by balancing her grandmother’s rejection with her daughter’s acceptance, she shows black women overcoming the divisive sexual ideology of the white patriarchy and establishing unit across the generations.”

Harriet Jacobs: A Life by Jean Fagan Yellin on Amazon

More about Harriet Ann Jacobs

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl on Goodreads

Harriet Ann Jacobs: The First Silence Breaker

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Ann Jacobs: An Introduction appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 6, 2018

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier (1938)

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier is surely the most iconic of the British author’s novels. During the British author’s lifetime, critics frequently dismissed her work because it was popular with the public, readable, and riveting. That view has since been revised.

As Rebecca celebrates its eightieth birthday in 2018, and moves onward, it has never been out of print. When it was first published, it was an immediate bestseller, immediately selling more than a million copies in hardcover. It has been reprinted countless times, and translated into a number of languages.

In 1940, just two years after its publication, it was adapted into an Academy Award-winning film directed by Alfred Hitchcock. Appropriately creepy and intense, yet oddly romantic, the screen version starring Joan Fontaine and Laurence Olivier captured the emotional tenor of the book. But it left out one key detail (which we won’t go into here), which makes the book a must-read before you even consider seeing the film. At least two fine mini-series have been made from the novel since — but the novel is still best!

Inspired by Jane Eyre

Du Maurier was something of an expert on the Brontë family. So the hypothesis that Rebecca was inspired by Charlotte Brontë‘s Jane Eyre rings true. The gothic atmosphere of a castle-like estate and a brooding, secretive husband with a troubled first marriage are elements that the two books have in common. But they diverge in important ways.

The character of Jane Eyre is feisty and independent, but the nameless narrator in Rebecca is shy and diffident. The story is cleverly told in the first person by this shy and awkward young bride of the older, mysterious Maxim de Winter. He is, like the other inhabitants of Manderley castle, haunted by the shadow by her husband’s deceased first wife, Rebecca.

You might also like: Rebecca — 1940 Movie

Mixed reviews give way to praise

Though the book initially received many accolades upon initial publication, many reviews, like the one in the The Times of London Literary Supplement in August of 1938:

“‘Rebecca’ is a lowbrow story with a middlebrow finish. As such it squares with a formula for novel-writing that yields handsome results several times in the year. If one chooses to read the book in a critical fashion – but only a tiresome reviewer is likely to do that – it becomes an obligation to take off one’s hat to Miss du Maurier for the skill and assurance with which she sustains a highly improbable fiction. Whatever else she may lack, it is not the story-teller’s flow of fancy. All things considered, this is an ingenious, exciting and engagingly romantic tale.”

Other reviewers dismissed it as “women’s fiction,” or mere gothic romance. But with the benefit of decades of perspective, Rebecca is acknowledged as a masterpiece psychological thriller. In a 2017 article in The Telegraph, Tammy Cohen encapsulated why du Maurier has been such an influence on those who came after her. On Rebecca, she writes:

“Only on re-reading some years later did I pick up on the subtler joys of the book: the compelling, dreamlike writing, the brooding sense of place, the growing menace which creeps up on you so slowly it’s like looking up from an engrossing book to find the sky outside has darkened and the radiator long since grown cold … in many ways Daphne du Maurier was the architect of modern domestic noir.”

From its iconic first line — “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again” — to its last suspenseful twist, Rebecca has kept readers riveted for decades. It’s a window into the best and worst of human nature, and a complex portrait of love and jealousy, leaving the reader to wonder: what would we do, and how would we feel in the nameless narrator’s place?

Following is a deservedly kind review from the time of the book’s publication that is careful not to give anything away:

A 1938 review of Rebecca

A review of Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier, originally published in The Lincoln (NE) Daily Star, December 1938: Jane Eyre will be the first and inevitable comparison of those who read this thick, rich, fast, and lively melodrama of a heroine whose name is never given, who considers herself unattractive, but who never becomes more definite about that beauty or lack of it, of sensational incidents that cumulate in two climaxes without the slightest letdown, and which chafes the imagination with hints for well over 300 pages, but never comes through with facts.

Illness of the vulgar Mrs. Van Hopper left the self-conscious, shy, diffident, and lonely child who was her companion temporarily adrift in Monte Carlo. She was amazed when Maxim de Winter, twice her age, carrying a tragic history in the recent death of his wife Rebecca, fleeing from the memories of the beautiful Manderley, asked her to marry him. The girl, perhaps in love with dreams of the noted Cornwall estate and the romance surrounding de Winter, unhappy in distasteful surroundings, is married to him, returns to Manderley with him.

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier on Amazon

Miss du Maurier writes of her people with a lavish hand, and they come to life beneath her gestures. Dead some months, the most potent person at Manderley is Rebecca, kept alive by the demon who is Mrs. Danvers, as excruciatingly a wicked soul as you’ll find anywhere, and by de Winter in his remoteness and repressions.

The girl whom Mrs. Danvers, as housekeeper, scarcely recognizes as Mrs. De Winter, but rather as an interloper and intruder, can not cope with the hideous forces at work in the Manderley that was to have been so pleasant, where she would walk in the garden with her husband and plan a new future within old walls.

Rebecca ruled from her grave, ruled through the things and the persons she has left behind. She was more real to the newcomer’s enemies, and those who would be her friends, than the lonely girl who lived with them.

It’s the sort of book in which anything might happen, and anything does, even murder. There are scenes of sharp play of wits, of high tragedy, of intense reconciliation, of fervidly restrained drama.

Du Maurier’s Rebecca: A Worthy “Eyre” Apparent

More about Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Daphne du Maurier’s inspiration for Rebecca

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier (1938) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 4, 2018

Quotes from The Awakening by Kate Chopin

The Awakening (1899) by Kate Chopin (1850 – 1904) is one of the first American novels to focus on the struggle against societal expectations for women in their roles as wives and mothers. It was met with mixed reactions to this somewhat taboo subject matter. The novella follows the story of Edna Pontellier, a woman with unfulfilled sexual desires who questions the sanctity of motherhood. The theme of marital infidelity is approached from the unique perspective of the wife.

The Awakening was widely banned, and even fell out of print for several decades before being rediscovered in the 1970s. It’s now considered a classic of feminist fiction. In her analysis of this novella on this site, Sarah Wyman writes that it “came under immediate attack when published and was banned from bookstores and libraries. The author died virtually forgotten, yet The Awakening has been rediscovered and holds a secure and prominent position as a watershed text in U.S. literature and feminist studies.”

You can read the full text of The Awakening on this site. Following are a collection of quotes from The Awakening by Kate Chopin:

“The voice of the sea is seductive, never ceasing, whispering, clamoring, murmuring, inviting the soul to wander in abysses of solitude.”

“She was becoming herself and daily casting aside that fictitious self which we assume like a garment with which to appear before the world.”

“I would give up the unessential; I would give up my money, I would give up my life for my children; but I wouldn’t give myself. I can’t make it more clear; it’s only something I am beginning to comprehend, which is revealing itself to me.”

“He could see plainly that she was not herself. That is, he could not see that she was becoming herself and daily casting aside that fictitious self which we assume like a garment with which to appear before the world.”

“The voice of the sea is seductive; never ceasing, whispering, clamoring, murmuring, inviting the soul to wander for a spell in abysses of solitude; to lose itself in mazes of inward contemplation. The voice of the sea speaks to the soul. The touch of the sea is sensuous, enfolding the body in its soft, close embrace.”

You might also like: Willa Cather’s Review of The Awakening

“A certain light was beginning to dawn dimly within her — the light which, showing the way, forbids it.”

“Who can tell what metals the gods use in forging the subtle bond which we call sympathy, which we might as well call love.”

“To be an artist includes much; one must possess many gifts — absolute gifts — which have not been acquired by one’s effort. And, moreover, to succeed, the artist must possess the courageous soul.”

“I don’t mind walking. I always feel so sorry for women who don’t like to walk; they miss so much — so many rare little glimpses of life; and we women learn so little of life on the whole.”

“There are some people who leave impressions not so lasting as the imprint of an oar upon the water.”

“She had all her life long been accustomed to harbor thoughts and emotions which never voiced themselves.”

“One of these days,” she said, “I’m going to pull myself together for a while and think – try to determine what character of a woman I am, for, candidly, I do not know. By all the codes which I am acquainted with, I am a devilishly wicked specimen of the sex. But some way I can’t convince myself that I am. I must think about it.”

“And, moreover, to succeed, the artist much possess the courageous soul.”

“Perhaps it is better to wake up after all, even to suffer, rather than to remain a dupe to illusions all one’s life.”

The Awakening by Kate Chopin on Amazon

“She reminded him of some beautiful, sleek animal waking up in the sun.”

“She felt as if a mist had been lifted from her eyes, enabling her to look upon and comprehend the significance of life, that monster made up of beauty and brutality.”

“It was going to be a beautiful morning, I remember thinking, as I left the house; soft and close, bursting with whispered promises, as only a daybreak in early summer can be.”

“She was seeking herself and finding herself in just such sweet, half-darkness which met her moods. But the voices were not soothing that came to her from the darkness and the sky above and the stars. They jeered and sounded mournful notes without promise, devoid even of hope.”

Kate Chopin on her writing life: On Certain Brisk, Bright Days

“Sometimes I feel this summer as if I were walking through the green meadow again, idly, aimlessly, unthinking and unguided.”

“It is bizarre to treat all differences as oppositions,”

“There was with her a feeling of having descended in the social scale, with a corresponding sense of having risen in the spiritual.

“It seems to me if I were young and in love I should never deem a man of ordinary caliber worthy of my devotion.”

“She was happy to be alive and breathing, when her whole being seemed to be one with the sunlight, the color, the odors, the luxuriant warmth of some perfect Southern day.”

“Don’t stir all the warmth out of your coffee; drink it.”

“And Nature takes no account of moral consequences, of arbitrary conditions which we create, and which we feel obliged to maintain at any cost.”

“She felt no interest in anything about her. The street, the children, the fruit vender, the flowers growing there under her eyes, were all part and parcel of an alien world which had suddenly become antagonistic.”

“Then the candor of the woman’s whole existence, which every one might read, and which formed so striking a contrast to her own habitual reserve—this might have furnished a link. Who can tell what metals the gods use in forging the subtle bond which we call sympathy, which we might as well call love.”

“She was becoming too familiar for her own comfort and peace of mind. It was not despair; but it seemed to her like life was passing her by, leaving its promise broken and unfulfilled.”

“But the beginning of things, of a world especially, is necessarily vague, tangled, chaotic, and exceedingly disturbing.”

“She says a wedding is one of the most lamentable spectacles on earth.”

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from The Awakening by Kate Chopin appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 3, 2018

Alice Dunnigan, Trailblazing African-American Journalist

Alice Dunnigan (April 27, 1906 –May 6,1983), born Alice Allison, was the first black female correspondent to receive White House credentials, and was also the first black female member of the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives press galleries. She covered Harry Truman’s 1948 presidential campaign, another first for an African-American female journalist. A true trailblazer, she was known for her tough, forthright questions. Her gutsy approach led her from journalism into a position that spanned the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. It’s exciting news that the Newseum in Washington, D.C. will have a life-size statue of her in honor of her contributions to American journalism.

As a girl growing up in Russellville, a rural Kentucky town, Alice dreamed of traveling the world as a reporter. By age thirteen, she had her sights set. For the daughter of a sharecropper and laundress in 1919, it was a daring ambition.

A top student and a dedicated teacher

Alice was so hungry for education that she walked miles to and from the segregated schoolhouse, and was always a top student. When it came time for college, she found that few doors were open to her as a black student in the 1920s. When she came upon a rare chance to get into a teacher’s college, she jumped at it.

In the segregated classroom where she wound up teaching, Alice passed along pride in the accomplishments of black Kentuckians to her students. With her own funds, she printed and distributed pamphlets on the subject to her students. She taught for nearly two decades, was briefly married (becoming Alice Dunnigan), had a son, and divorced. Pay for black teachers was meager, so she did laundry, cleaning, cooking — anything to make ends meet.

Though Alice loved teaching, she never forgot her original ambition of becoming a journalist. She wrote for newspapers on the side, publishing articles and stories in various Kentucky newspapers.

Starting anew in Washington, D.C.

As the U.S. entered World War II in the early 1940s, there was an increased need for government workers. Alice moved to Washington D.C. and was hired as a clerk-typist. She worked by day and took courses in journalism at Howard University at night.

After the war, Alice’s first job was as Washington correspondent for the Chicago Defender, a leading black newspaper. She gained press access to the Senate and House of Representatives to cover politics and civil rights for the paper. While she wrote about the segregation laws plaguing African-Americans in the 1940s and 1950s, she often faced discrimination herself. She wasn’t allowed into certain buildings to report on President Eisenhower, and when President Taft died, she was forced to sit with servants while covering his funeral.

Despite those frustrations, by the late 1940s, Alice had achieved her girlhood dream of seeing the world through her work as a journalist. She traveled all over North and South America, the Caribbean, Africa, and the Middle East. Still, in her quest to be an excellent journalist, she struggled financially. Her jobs didn’t always pay well, and she was sometimes even compelled to fund her own travels. Still, she prevailed, with the belief that the work she did as a reporter and correspondent was worthy and important.

President Harry S. Truman speaks with Alice Dunnigan

Eisenhower refused to call on her

For black reporters accredited to the White House, it was a good opportunity to raise questions and get a direct reply on civil rights issues. It worked fairly well with Truman, with whose campaign she had traveled in 1948. He’d either say “no comment” or give a concise answer. Not so when Eisenhower became president in 1952. Not particularly friendly to anti-discrimination legislation, he became quite annoyed, and increasingly irate, when she raised such issues.

Some time in 1954, Alice posed a question on discrimination at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. She asked the president if he planned to take any steps recommended by the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC). Eisenhower was infuriated. A conservative columnist wrote a critical analysis of the questions raised by Alice and her colleague, Ethel Payne, writing, “the two gal reporters are hell-bent on competing with each other to see which one can ask President Eisenhower the longest questions.”

Eisenhower seemed to make up his mind never to call on Alice again. She went to every press conference and jumped to her feet between every question, just like all the reports. But the president just ignored her. This went on for a year, then another, until other news outlets started to notice.

The New York Post, ANP (Associated Negro Press, a syndicate of black newspapers), and The Daily Worker picked up the story, and it spread around the nation.

Recognized by Kennedy

The presidential boycott of Alice Dunnigan ended with the Eisenhower years. When she was called on by President Kennedy at his first live press conference on January 5, 1961, the headline in Jet magazine read, “Kennedy In, Negro Reporter Gets First Answer in Two Years.”

The story read: “… at his first nationally televised press conference, President John F. Kennedy “quietly scrapped a longstanding White House policy” which was to “ignore veteran correspondent Alice Dunnigan at press conferences.”

After that, she received letters and telegrams from people who had seen her on television, congratulating her for being the first black reporter to ask the new president a question, as well as the first female reporter to do so.

With controversy behind her, Alice said, “I continued my normal routine of covering White House press conferences.” Alice was an avid proponent of a vibrant black press:

“Without black writers, the world would perhaps never have known of the chicanery, shenanigans, and buffoonery employed by those in high places to keep the black man in his (proverbial) place by relegating him to second-class citizenship.”

A presidential appointment

Soon after, she left journalism to embark on her third act. President Kennedy was so impressed with her that he appointed her as an educational consultant on an important committee, making her the first black woman to be appointed to the new administration. She served on the new President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity as an educational consultant. She continued that work with the next First Lady, Mrs. Johnson, touring the country with her to visit schools and report on their progress. She logged many miles in that position, but it was somewhat easier than the roads she’d paved as a journalist.

In 1970, after serving nine years on that committee as well as the President’s Council on Youth Opportunity, she “walked out of the federal government, out of the political arena, out of journalism, out of that mad, mad, world of work, and into the serenity of a quiet, comfortable home life where there is peace, contentment, and happiness.”

Alone Atop the Hill by Alice Dunnigan on Amazon

Legacy

After Alice retired, she wrote her life story, A Black Woman’s Experience: From Schoolhouse to the White House (1974). A newer version of the book now called Alone Atop the Hill, came out in 2015. Her hope for her legacy was this:

“It is my fondest hope that the story of my life and work will by interpretation, investigation, information, and inspiration, encourage more young writers to use their talents as a moving force in the forward march progress and that their efforts will soon result in giving Americans the kind of nation that those of my generation so long hoped and worked for.”

With her steely determination and love of learning, Alice Allison Dunnigan was always willing to fight for race and gender equality. She said, “I hope to live to see an ordinary woman go as far as an ordinary man. A woman has to work twice as hard.” And this, too: “Race and sex were twin strikes against me. I’m not sure which was the hardest to break down,”

Alice Allison Dunnigan won more than 50 awards for her work in journalism. In 1985, two years after she died, she was inducted into the Black Journalist Hall of Fame. She died in Washington, D.C., in 1983.

Alice Dunnigan’s firsts

Alice Dunnigan was the first black woman …

… to gain press credentials to the White House.

… to travel with the US president (Truman) on a campaign.

…to get press access to the House and Senate galleries, Department of State, and the Supreme Court.

…to be voted into the White House Newswomen’s Association and The National Women’s Press Club.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Alice Dunnigan, Trailblazing African-American Journalist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 2, 2018

Rebecca West

Rebecca West (December 21, 1892 – March 15, 1983), British novelist, journalist, and essayist, was born Cicely Isabel Fairfield in County Kerry, Ireland. Her mother was a pianist; her father, a would-be journalist and ne’er-do-well, abandoned his family when West was eight years old, after which they moved to Edinburgh, Scotland. There she was educated at George Watson’s Ladies College, though contrary to its name, was a secondary school.

At age 14, she survived tuberculosis, and had to end her education at age 16, due to lack of finances. Some time later she studied drama at a London academy. With an unhappy childhood behind her, she assumed the name Rebecca West after a strong-willed woman in Rosmersholm, a play by Ibsen.

West was a woman of many trades and talents early on: she studied as an actress, started working as a journalist in 1911 at The Freewoman, and was active in the woman’s suffrage movement. In her work as a journalist, she wrote essays and reviews for publications like New York Herald Tribune, The Daily Telegraph, The New Republic and New York American. Her first book, Henry James: A Critical Biography, was published in 1916.

Rebecca West Quotes on Art, Experience, and Human Nature

Scathing review of H.G. Wells leads to a love affair

After writing a scathing review of H.G. Wells’ Marriage in 1912, calling him “the Old Maid among novelists,” the two met. The following year they become lovers and had a ten year long affair, which produced a son, Anthony West. Her relationship with both father and son were stormy. Her son resented her absences from him during his childhood, yet never blamed his father for even more prolonged absences. He rather idolized his father, and grew up to be a talented writer. In a thinly veiled autobiographical novel (Heritage, 1955) he portrayed his mother in a very unflattering light, for which she never forgave him.

Among her other lovers were Charlie Chaplin and Lord Beaverbrook, a newspaper tycoon. As a witty and beautiful woman, men were drawn to her wherever she went on her far-flung travels. In 1930 she married Henry Maxwell Andrews, a banker, and they remained together, though spending much time apart, until his death in 1968.

Novels and non-fiction

In 1918 The Return of the Soldier was published. This, her first novel, was a study of what was then called shell-shock (now more often called PTSD). Her subsequent novels, all considered extremely fine yet undervalued by critics, included Harriet Hume (1929), The Thinking Reed (1936), The Fountain Overflows (1957), and The Birds Fall Down (1966).

The Birds Fall Down by Rebecca West

Travels and politics

Rebecca West loved travel and politics, both of which figured significantly in her writing. Traveling to countries such as Mexico, Yugoslavia, and South Africa influenced her works, notably Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941), considered a classic of literature that spans the genres of travel, culture, and politics.

Other works of nonfiction included The Meaning of Treason (1949), about the role of the intellectual, scientist, and traitor in society; A Train of Powder (1955), which included reports of criminal trials; and The Court and the Castle (1958), which examines how political and religious ideas interact in literature.

In addition to her books, West wrote countless articles and essays for a number of publications on both sides of the Atlantic, including The New Yorker.

A life against tyranny and prejudice

As described in Rebecca West: A Life by Carl Rollyson, “West’s restless, ferocious intelligence took her into every corner of the world in every conceivable genre, and her ability to astonish with what she found there was seemingly never-ceasing. But if her gifts were protean, here agenda was immutable, to make of her life a campaign against tyranny and prejudice.

“A novelist, critic, biographer, travel writer, and investigative journalist, West had a keen eye for conflict, and a razor tongue for battle. Called ‘George Bernard Shaw in skirts’ by pundits, she was a woman both feted for her achievements and feared for her cunning wit — ‘with malice toward all’ was her motto, and her barbs are legend.”

Doris Lessing said of West that she had not been given her due for her vast accomplishments: “She was the best woman journalist of her time, playing an important role in informing public opinion about extremist politics, both communist and fascist. She wrote one of the most remarkable books of the century, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, about traveling in the Balkans … but it is much more than that, a meditation about the nature of the human animal.”

An original thinker

Rebecca West is considered one of the great minds of the twentieth century. She looked at the human condition with the dispassionate eye of a journalist and the heart of a feminist. For example, from a 1928 speech to the Fabian Society:

“There is one common condition for the lot of women in Western civilization and all other civilizations that we know about for certain, and that is, woman as a sex is disliked and persecuted, while as an individual she is liked, loved, and even, with reasonable luck, sometimes worshipped.”

7 Thought-Provoking Views by Rebecca West

Honors and legacy

In 1949 she was named a Commander of the Order of the British Empire and ten years later became a Dame Commander of the Order, hence her oft-used title, Dame Rebecca West. West’s writing won her the Women’s Press Club Award for Journalism in 1948 in the United States. In 1982, her first novel, Return of the Soldier, was made into major film. She was friends and colleagues with numerous other literary, artistic, and political figures of her time.

Dame Rebecca West became increasingly frail and lost eyesight in her last years. She basically died of old age in 1983, at the age of 90, still bemoaning the fraught relationship with her son on her deathbed.

William Shawn, then the editor-in-chief of The New Yorker, wrote upon learning of her death: “Rebecca West was one of the giants and will have a lasting place in English literature. No on in this century wrote more dazzling prose, or had more wit, or looked at the intricacies of human character and the ways of the world more intelligently.” All that said, along with the many accolades she received in her lifetime, is her legacy secure? Is she still as widely read as she deserves to be?

More about Rebecca West on this site

Rebecca West Quotes on Art, Experience, and Human Nature

7 Thought-Provoking Views by Rebecca West

Major works

West produced a vast body of work, both fiction and nonfiction. This is but a small sampling of her most enduring.

The Return of the Soldier (1918)

The Judge (1922)

The Thinking Reed (1936)

Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941)

A Train of Powder (1955)

The Fountain Overflows (1956)

The Birds Fall Down (1966)

Biographies about Rebecca West

Dangerous Ambition: Rebecca West and Dorothy Thompson by Susan Hertog

Rebecca West by Victoria Glendinning

Rebecca West: A Life by Carl Rollyson

More Information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of West’s books on Goodreads

Rebecca West’s obituary in the New York Times

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Rebecca West appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 30, 2018

7 Later Novels by Willa Cather

Willa Cather (1873 – 1947), it could be argued, wrote several Great American Novels, characterized by their stark beauty and economy of language. Her earlier novels include several that have remained classics, notably, O Pioneers!, The Song of the Lark, and My Ántonia — all of which came out in quick succession in the nineteen-teens. Several novels, all well received, came out in the twenties. One of Ours (1922) received a Pulitzer Prize the following year. Here we take a brief look at the seven later novels of Willa Cather, beginning with A Lost Lady (1923).

In the post World War I years, Cather was distressed by the growth of materialism and the loss of the pioneering spirit of the country that had informed so many of her most successful works. Cather is described in the Library of America omnibus collecting her later works as “among the most accomplished American writers of the twentieth century, are at once intensely lyrical and highly controlled. Their formal perception and expansiveness of feeling are an expression of Cather’s dedications both to art and to the open spaces of America.”

The following descriptions of the later novels of Willa Cather, with the exception of My Mortal Enemy, are from the 1990 Library of America edition of Cather: Later Novels, published by Library Classics of the United States.

A Lost Lady

A Lost Lady (1923) exemplifies Willa Cather’s principle of conciseness. It concerns a lady of uncommon loveliness and grace who lends an aura of sophistication to a frontier town, and explores the hidden passions and desires that confuse those who idealize her. The recurrent conflict in Cather’s work, between frontier culture and an encroaching commercialism, is nowhere more powerfully articulated.

More about A Lost Lady

A Lost Lady on Amazon

The Professor’s House

The Professor’s House (1925) encapsulates a story within a story. In the framing narrative, Professor St. Peter, a prize-winning historian of the early Spanish explorers, finds himself disillusioned with family, career, even the house that reflects his success Within this story is another, of St. Peter’s friend Tom Outland, whose brief but adventurous life still shadows those he loved.

More about The Professor’s House

The Professor’s House on Amazon

Death Comes for the Archbishop

Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927) tells the story of the first bishop of New Mexico in a series of tableaux modeled on the medieval lives of the saints. Cather affectionately portrays the refined French Bishop Later and his more earthy assistant within the harsh and beautiful landscape of the Southwest and among the Mexicans, Indians, and settlers they were sent to serve.

More about Death Comes for the Archbishop

Death Comes for the Archbishop on Amazon

My Mortal Enemy

My Mortal Enemy (1928) From the very first sentence to the very last of My Mortal Enemy, Cather holds the interest of the reader by telling the story, not of an incident, but of a life. In just some 120 pages, the tragic story of a great artist is told. Has the author tried to undo her A Lost Lady? There is a definite mark of similarity between the two books, but one feels that she has not come up to her earlier mark, though she has done so admirably.

More about My Mortal Enemy

My Mortal Enemy on Amazon

Shadows on the Rock

Shadows on the Rock (1931), though its setting and subject are unusual for Cather, expresses her fascination with the “curious endurance of a kind of culture, narrow but definite.” It is a re-creation of 17th-century Quebec as it appears to the apothecary Auclaire and his daughter Cécile: the town’s narrow streets, the supplies ships on its great river, its merchants, profligates, explorers, and missionaries, and towering personalities like Frontenac and Laval, all parts of a colony struggling to survive.

More about Shadows on the Rock

Shadows on the Rock on Amazon

Lucy Gayheart

Lucy Gayheart (1935) returns to the themes of Cather’s easier writings, in a more somber key. Lucy, talented, spontaneous, and eager to explore the possibilities of life, leaves her prairie home to pursue a career in music. After a happy interval, her life takes an increasingly disastrous turn.

More about Lucy Gayheart

Lucy Gayheart on Amazon

Sapphire and the Slave Girl

Sapphira and the Slave Girl (1940) marks a conclusion to Cather’s career as a novelist. Set in Virginia five years before the Civil War, the story shows the effects of slaveholding on Sapphira Colbert, a woman of spirit and common sense who is frighteningly capricious in dealing with people she “owns,” and on her husband, who hates slavery even while he conforms to the social order that permits it. When, through kindness, he refuses to sell a slave, Sapphira’s jealous reaction precipitates a sequence of events that registers a conflict of cultural as well as personal values.

More about Sapphira and the Slave Girl

Sapphira and the Slave Girl on Amazon

Willa Cather: Later Novels on Amazon

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 7 Later Novels by Willa Cather appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 28, 2018

The Wine of Astonishment by Martha Gellhorn (1948)

Martha Gellhorn (1908 – 1998) covered nearly every global conflict, from the Spanish Civil War to Vietnam. She reported on virtually every major world conflict that took place during her 60-year career, and is considered one of the greatest war correspondent of the twentieth century. It’s a fitting legacy, but she also produced a body of fine fiction. The Wine of Astonishment (1948) is directly inspired by her first-hand experiences as a World War II correspondent.

The protagonist of the novel, Jacob Levy, witnessed the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp, and the shock of the experience changes everything. The novel examines the horrors of war and the issues of personal responsibility that still resonate today. When the The Wine of Astonishment was first published, it was a New York Times bestseller. It was long out of print, and was reissued in 2016 as The Point of No Return in paperback and as an e-book.

A 1948 review of The Wine of Astonishment

The Feminine View on War, a review of The Wine of Astonishment by Martha Gellhorn in The Daily Oklahoman, November 7, 1948: Until World War II, women were generally denied the experience for writing intimately and authentically of men in battle. That this is no longer true is shown in Martha Gellhorn’s novel about soldiers during the Battle of the Bulge and the Allied drive into Germany.

Miss Gellhorn’s book is written against a background of nine years observance of war as a correspondent covering the war in Spain, the Russo-Finish war, the Sino-Japanese war before Pearl Harbor, World War II in Europe, and lastly the post-war fighting in Java.

In her account of soldiers, Miss Gellhorn can be as tough minded as the early Dos Passos or Norman Mailer or as tender as Ernest Hemingway in his love story placed in a battle setting in A Farewell to Arms. In fact, Miss Gellhorn merits comparison on the individuality of her characters and in her softly modulated style.

Point of No Return (first published as The Wine of Astonishment)

is now available as an e-book on Amazon

This novel, beginning with the fighting in Belgium, focuses on two soldier-characters — Lieutenant Colonel Smithers, a Georgian who is a battalion commander, and his jeep driver, Jacob Levy, a handsome Jewish boy from St. Louis. In Luxembourg for a two-week rest period. Smithers seeks love and an understanding of the meaning of human existence in an affair with a disillusioned Red Cross girl; and Levy finds what Smithers fails to discover in his love for a gentle and lovely country girl.

The novel reaches a climax in an unreasonable act of violence committed by Levy after a visit to the Dachau crematory, when he first realizes the horror and magnitude of Nazi repudiation of humanity.

Miss Gellhorn’s handling of her interrelated themes is skillful, her characterization is understanding and believable, and her prose style is flexible and perceptive. The Wine of Astonishment is certainly one of the best novels of World War II.

See also: The Trouble I’ve Seen by Martha Gellhorn (1936)

The New York Times’ 1948 review titled “Taut, Tender, Tough” began by doing something that Martha always loathed — comparing her writing with that of Ernest Hemingway, her ex-husband. But it was laudatory on its own terms, concluding:

“Memorable … are her pictures of men at the front, on leave, at parties, in the rubbled towns of Germany and amid its fat, prosperous looking farms. In her scenes of action she achieves those two contradictory parts of the military whole: she pins down the irreducible incident with perfect lucidity at the same time that she conveys an impression of battle-blurring confusion.Miss Gellhorn’s talent were never better exhibited than in this humanly penetrating novel of war.”

Read the New York Times‘ full review of The Wine of Astonishment.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Wine of Astonishment by Martha Gellhorn (1948) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 27, 2018

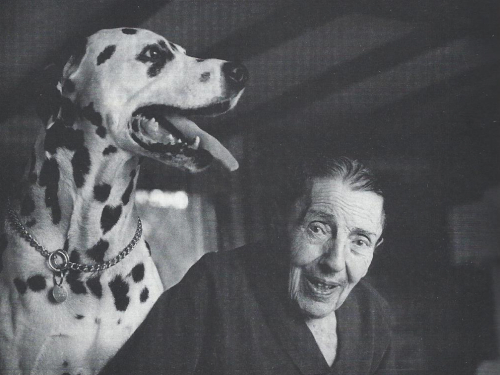

Dodie Smith

Dodie Smith (May 3, 1896 – November 24, 1990) was born Dorothy Gladys Smith in Lancashire, England, and was one of the most successful female dramatists of her generation. The British novelist and playwright is best known for her novel The Hundred and One Dalmatians (later better known as The 101 Dalmatians) and the young adult novel I Capture the Castle.

Dodie Smith came to her love of theatre early, with many of her family members either enthusiasts or amateurs in that realm. She studied at the Academy of Dramatic Art, exploring a short career in acting before becoming a successful playwright and novelist.

Early life

Born as an only child to Ernest and Ella Smith, her father died in 1898 when she was two years old. Dodie and her mother moved in with her grandparents, William and Margaret Furber. She credits her theater-loving grandfather in her autobiography, Look Back with Love (1974), as one of the reasons she became a playwright.

At age ten, Dodie wrote her first play, and she began acting in small roles during her teen years at the Manchester Athenaeum Dramatic Society.

When Dodie was fourteen years old, her mother remarried and they moved to London with her new husband. Dodie attended school at St Paul’s Girls’ School and later at age eighteen, Dodie entered the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. She landed her first acting role in Arthur Wing Pinero’s play, Playgoers.

See also: The Town in Bloom by Dodie Smith (1965)

Success in the theater

Dodie’s acting pursuits led her to land stints with a traveling YMCA company to entertain troops during World War I, as well as touring with the French comedy French Leave. She sold a movie script, Schoolgirl Rebels, under the pen name Charles Henry Percy and wrote a one-act play, British Talent.

In 1931 she wrote her first full-length play, Autumn Crocus, using the pseudonym C.L. Anthony. She need not have hidden behind her nom de plume, as the piece was quite successful. When the true identity was exposed, newspapers called her the “shopgirl playwright” because she had worked in retail stores.

Dodie wrote a string of successful plays that made it to the London stage in the 1930s and 1940s, including the aforementioned Autumn Crocus, as well as Call It A Day (the longest running of all her work), Dear Octopus, and Lovers and Friends.

I Capture the Castle

In 1939 Smith married Alec Beesley, who was a longtime friend and her manager from the furniture shop. The two moved to the U.S. in the 1940s due to his stance as a conscientious objector in Britain. Her homesickness for England inspired her to write I Capture the Castle, her first novel, which was published in 1948. It was an immediate hit and still enjoys a devoted following. It begins with the unforgettable line, “I sit here writing this in the kitchen sink.”

The Forgotten Authors series highlighting Dodie Smith in the U.K.’s Independent encapsulates I Capture the Castle as:

” … both a parallel to and the opposite of The Catcher in the Rye, published three years later. It should surely be regarded as an equal, but whereas Holden Caulfield became an eternal symbol for rebellion, Cassandra Mortmain, Smith’s teenaged heroine, was possibly hampered by her background. She is, after all, a naive, optimistic bohemian trapped in her family’s collapsing castle in the middle of nowhere, while her beloved father, a blocked one-time novelist who keeps the family in penury and isolation, struggles with his demons.”

The 101 Dalmatians

Dodie and Alex returned to England in the early 1950’s, much to Dodie’s delight. Her years in the United States were never completely content, as she suffered from homesickness and guilt at abandoning her country in time of war. During their time in America, the couple became friends with fellow writers, such as Christopher Isherwood and Charles Brackett.

After their return to England, Dodie’s The Hundred and One Dalmatians was published in 1956. Pongo, the four-legged main character, was named after Dodie’s own pet Dalmatian. The novel was adapted by Disney into a 1961 animated film, called One Hundred and One Dalmatians. Dodie wrote a sequel, published in 1967, called The Starlight Barking.

101 Dalmatians (1996 film) on Amazon

Film Adaptations

One Hundred and One Dalmatians was released to theaters in January, 1961 and was an immediate success with audiences. Critics generally liked it as well, though they didn’t put it in the same league as other Disney animated films. “While not as indelibly enchanting or inspired as some of the studio’s most unforgettable animated endeavors,” wrote Variety, “this is nonetheless a painstaking creative effort.”

In 1996, Walt Disney adapted the book into a live-action film, with the streamlined title 101 Dalmatians. The live-action version wasn’t as well received. One critic encapsulated the general response: “Neat performance from Glenn Close aside, 101 Dalmatians is a bland, pointless remake.”

Additionally, a British film adaptation of I Capture The Castle was released in the UK in 2003, and shortly thereafter in the U.S. It’s available for streaming on Amazon.

These were the best known film adaptations from Dodie’s works, though there were others, including: Looking Forward (1933, adapted from Service), Autumn Crocus (1934), Call it a Day (1937), and Dear Octopus (1943). All of these were adapted from plays rather than novels.

You may also enjoy: Quotes from I Capture the Castle

Later life

Dodie and Alec spent their last years in quiet seclusion in their country cottage in England where Dodie spent time working on her memoirs (starting with the phrase Look Back) and it’s been said Alec devoted his time to gardening. Charley, Dodie’s loyal Dalmatian companion at the time, become incredibly important to her well-being after Alec’s sudden death in 1987.

Dodie died in 1990 in England. She had named Julian Barnes as her literary executor, a job she thought wouldn’t be much work. Barnes writes of the complicated task in his essay “Literary Executions,” revealing among other things how he secured the return of the movie rights to I Capture the Castle, which had been owned by Disney since 1949.

Dodie’s personal papers are archived in Boston University’s Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center, and include manuscripts, photographs, artwork, and her correspondence with esteemed literary friends, such as Christopher Isherwood and John Gielgud.

More about Dodie Smith on this site

Quotes from I Capture the Castle

Major Works

I Capture the Castle (1948)

The Hundred and One Dalmatians (1956)

The New Moon with the Old (1963)

The Town in Bloom (1965)

The Starlight Barking (1967)

It Ends in Revelations (1967)

Autobiographies

Look Back with Love: a Manchester Childhood (1974)

Look Back with Mixed Feelings (1978)

Look Back with Astonishment (1979)

Look Back with Gratitude (1985)

Biography

Dear Dodie by Valerie Grove

Selected Plays

Autumn Crocus (1931)

Service (1932)

Dear Octopus (1938)

More Information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Dodie Smith’s books on Goodreads

Dodie Smith page on Amazon

Film adaptations of Dodie Smith’s works

Looking Forward (1933, adapted from Service)

Autumn Crocus (1934)

Call It a Day (1937)

Dear Octopus (1943)

Animated film version of One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961)

Live action film version of The 101 Dalmatians (1996)

I Capture the Castle (2003)

Visit and research

Dodie Smith’s Home – Dorset Square, London, U.K.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Dodie Smith appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 25, 2018

Giant, the 1956 film based on Edna Ferber’s Epic Novel

Giant, the 1956 film, was based on the epic 1952 novel of the same title by Edna Ferber. The saga of a wealthy Texas ranching family, the film starred Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, and James Dean, with appearances by Chill Wills, Mercedes McCambridge, Carroll Baker, Jane Withers, Dennis Hopper, Sal Mineo, and Rod Taylor. Giant was notable for being James Dean’s final film performance before his tragic death in a car accident. He was nominated posthumously for an Academy Award nomination for his portrayal of Jett Rink, a poor but ambitious ranch hand

When Giant was first published, it received some harsh reviews from Southern critics. Like many of Ferber’s dramatic novels, it wove in themes of race and class. Still, it was a blockbuster bestseller, as Ferber’s books inevitably were. The film version of Giant was as big and sprawling as the book, though some of its more controversial aspects were toned down.

This big story is difficult to boil down to a few plot points, but basically, it’s the story of a wealthy Texas rancher, Jordan “Bick” Benedict Jr., who marries beautiful, strong-willed Leslie. The issues of Mexican workers and the subplot of ranch hand Jett Rink, who becomes an oil tycoon, are woven into the narrative.

Giant was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry in 2005 by the Library of Congress, for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” The film was generally quite well received when it was released. Here’s the official trailer — don’t mind the corny music or narration!

Following are two views of the making of the film, mainly from the perspective of how the director, George Stevens, adapted a novel as big as Texas to the screen.

Mighty “Giant” Comes to the Screen

From the Austin-American, Sunday, November 4, 1956: After more than two years’ of careful preparation and filming, George Stevens is bringing to the screen the film which many feel is his masterpiece. That film is Giant, his mighty movie treatment of Edna Ferber’s controversial but bestselling novel about modern-day Texas.

Filmed on an epic scale worthy of the novel’s Texas locale, producer-director Stevens himself feels that the picture represents one of his best efforts of a career which has included such powerful films as A Place in the Sun and Shane.

But to him, Giant is more than merely a regional story of Texas. He regards it as essentially “a stirring chronicle of three decades of American family life and the profound human emotions generated out of the problems of our changing times.”

To bring such qualities to the screen, Stevens has either softened or done away with completely much of Miss Ferber’s vitriolic approach which made the book such an unpleasant subject among Texans, and, in its place, has added more human elements.

Giant, the 1956 film on Amazon

Both because Miss Ferber’s book was so widely read and because Stevens had given new emphasis to these human qualities, many months were spent in casting the right actors, rather than the obvious one, for each role. The parts were eagerly sought by some important players, but Stevens carefully weighed each part until he had built a cast he felt was ideal.

For the role of Leslie Benedict, the Virginia girl suddenly transported to the barren reaches of an early Texas cattle empire, Stevens selected Elizabeth Taylor, whom he had directed in A Place in the Sun. As Bick Benedict, the strong, confident owner of Reata Ranch, he chose Rock Hudson, a young actor of steadily maturing talent.

The late James Dean, whom Stevens regarded as one of the best young actors of the decade, was chosen to play Jett Rink, the poor ranch hand whose desire to be somebody is partially fulfilled when he strikes oil. Giant marks Dean’s last film appearance after a brief but brilliant career of only three pictures.

Jane Withers, who shattered box office records as a child star, ended an eight-year retirement to play Vashti, and Chill Wills departed from a long series of films to take on the role of Uncle Bawley.

Others starring in top roles include Oscar-winning Mercedes McCambridge as Luz Benedict, Carroll Baker as Luz II, and Dennis Hopper as Jordan Benedict III. Giant was filmed largely on location which brought the film company to Marfa, Texas for some three months of work. The running time of the epic picture is three hours and seventeen minutes.

James Dean and Elizabeth Taylor, two stars in “Giant”

From The Bridgeport Post, Sunday November 25, 1956: George Stevens’ production of Giant, from the novel by Edna Ferber, starring Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson and James Dean, represents a Warner achievement for which some of the most prodigious talents in both cinematic and literary worlds gave three of the best years of their lives.

Since 1952, Stevens has devoted all of his time to making Giant a picture which would match in scope and importance the Edna Ferber novel.

Miss Ferber made her own contributions to the picture in the course of a number of trips to Hollywood prior to and during the filming of Giant. In Hollywood, Miss Ferber held lengthy consultations with George Stevens and co-producer Henry Ginsberg. And she worked with Fred Guiol and Ivan Moffat, the screenwriters, on the screenplay for the film.

Miss Ferber’s excursion to California on behalf of Giant is hardly the first time the author had seen her books translated to the screen. Some other films based on Ferber’s novels include Show Boat, Saratoga Trunk, So Big, and Come and Get It.

See also Show Boat: From Page to Stage to Screen

Before and during the preparations, Stevens, over an eighteen-month period, rounded up his cast. Filming Giant carried Stevens & Company to the scenes envisioned by Miss Ferber in her novel – Virginia and Texas. Stevens began his picture where Miss Ferber began her book – in the lovely Virginia countryside near Charlottesville. Following two weeks of shooting here, the company moved to the vast open spaces near Marfa, Texas for the better part of three months. Interior scenes went before the cameras at Warner Bros. studios in Burbank, California.

Many unusual incidents marked the making of Giant, but two symbolize the magnitude of the entire operation. These involved transporting to Texas a prefabricated three-story Victorian mansion, which required five railroad flat cars, and a dozen imitation oil wells.

Yes, incredible as it may seem, Warners carried oil wells to Texas; for the fact is, there are none in the area around Marfa. One of Warners’ prop wells was even made to pump 2,200 gallons of ersatz oil a minute.

More about Giant, the 1956 film

Wikipedia

Rotten Tomatoes

Review in The Hollywood Reporter

Elizabeth Taylor’s Feisty, Feminist Turn in Giant

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Giant, the 1956 film based on Edna Ferber’s Epic Novel appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.