Nava Atlas's Blog, page 81

August 25, 2018

6 Early American Women Writers We Should Know More About

In the American colonies or early days of the Republic, for a woman to dare enter public discourse was a radical act of rebellion. To write and be published at a time when women had few legal or economic rights was just short of miraculous. Here’s an introduction to six of the most prominent early American women writers, all of whom deserve to be rediscovered and read.

In 1650, The Tenth Muse, Lately Sprung Up in America, a collection of poems by Anne Bradstreet, was the first publication in the colonies. From then on, women who wrote were criticized for being unwomanly and going against God’s teachings. To avoid censure, some occasionally wrote under pseudonyms, but sometimes used their own names, the consequences be damned!

More women writers than we might think took up the pen in the early days of the American nations. The following early American women writers, all born in the 1700s (with that exception of Anne Bradstreet, born in the early 1600s) wrote prolifically and passionately despite the risks to their reputations.

Anne Bradstreet (1612 – 1672) was one of the most prominent early American poets and the first writer in the American colonies to be published. Being from a wealthy family and getting a good education from her father was to her advantage. She produced a copious body of poetry at a time when it wasn’t acceptable for women to write. Anne encountered a great deal of criticism but didn’t accept the notion of women’s inferiority.

Anne wrote of her love for her family, but also expressed her struggles as a woman and as a mother in her work. She was fortunate to have had a supportive spouse, demonstrated in “To My Dear and Loving Husband,” one of her best-known poems. Read it in full among five poems by Anne Bradstreet. And read more about Anne Bradstreet.

Judith Sargent Murray (1751 – 1820) was quite possibly America’s first feminist essayist. “On the Equality of the Sexes” (1791), perhaps her best-known essay, was published a year before A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft, and yet, the former is rarely discussed. Murray was far ahead of her time, as an advocate of equal rights for women, including controlling their own earnings, and having access to education.

She lived a full literary life and made a living by her pen, something quite rare for a woman of her time. Occasionally she adopted male pen names, as she did for her column in Massachusetts Magazine. Writing as”The Gleaner,” she was read by prominent political figures of her era, including George Washington and John Adams. Also a playwright, she wrote The Medium (1795), arguably the first play staged in the young American nation. Read more about Judith Sargent Murray.

Susanna Rowson (ca. 1762 – 1824) was an American-British author and actress, best known for Charlotte Temple (1790), America’s first bestselling novel. In fact, it was the bestselling American novel until Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) replaced it with that distinction. With the classic theme of seduction and remorse, Charlotte Temple sparked a great deal of controversy in its time. Despite its heavy-handed moralizing and overwrought characterizations, it has endured as an example of early American literature.

An incredibly prolific writer, she produced numerous novels, plays, operas, and volumes of poetry. She also worked as a stage actress, opened a school for girls in Boston, and was an editor of a Boston-based periodical. Read more about Susanna Rowson.

Catharine Maria Sedgwick (1789 – 1867) wrote prolifically and was most active from the 1820s to the 1850s. She made a handsome living writing short stories for popular periodicals and helped popularize what we now call domestic literature. Sedgwick was a well known and highly respected New England literary figure in her time. She wrote six novels, eight works for children, several novellas, two biographies, and more than one hundred works of short prose.

Her work is recognized as part of a distinctive American literature in a league with Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper, and William Cullen Bryant. However, while these men are still read and studied, Sedgwick is all but forgotten. Perhaps it’s time to start reviving her reputation. Read more about Catharine Maria Sedgwick.

Mercy Otis Warren (1728 – 1814) was a poet, satirist, and playwright active during the Revolutionary War period. In an era when women’s political views didn’t count, she raised her pen and voice — often and loudly. Her pre-Revolutionary War plays were highly political and satirical, critiquing British rule.

Warren was considered one of the leading intellectuals of the time, and one of America’s first historians. She documented the Revolutionary period and published History of the Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution in 1805. It was one of the first nonfiction books by an American woman. She kept her focus on politics for most of her career, and even when she produced plays and poems through the Revolutionary and post-Revolution era, it was with an eye toward commentary. Read more about Mercy Otis Warren.

Phillis Wheatley (ca 1753 – 1784) was America’s first African-American poet and one of the first women to be published in colonial America. Kidnapped from Senegal/Gambia as part of the slave trade, she was bought by John Wheatley as a house slave for his wife. Phillis quickly mastered reading and writing, usually forbidden to slaves, and was recognized as a prodigy. Phillis began writing verse as she mastered the English language, and when she was between 13 and 14 years old, her first poem was published in The Newport Mercury. Further publication of her poems spread the word of her talent in the colonies. Her work was admired by George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

At age 19, her first book of poetry was published. Titled Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, by Phillis Wheatley, Negro Servant to Mr. John Wheatley of Boston, in New England, an edition was printed in Boston not long after its initial publication in London in 1773. Read more about Phillis Wheatley.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 6 Early American Women Writers We Should Know More About appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 23, 2018

Quotes from Middlemarch by George Eliot

George Eliot, the chosen pen name of Mary Ann Evans (1819 –1880), was an esteemed British author of Victorian-era novels. Her writing was political and inventive, inspired by art, psychology, and current events. The Mill on the Floss, Silas Marner, Romola, and Middlemarch are considered some of the finest and most important literary works in British literature. In addition to these and other novels, George Eliot also wrote poems, short stories, translations, and essays.

Middlemarch (1871) follows the tale of Dorothea Brooke and Tertius Lydgate, two characters destined to enter marriages that are not only unfulfilling, but also conflict with their personal aspirations. George Eliot scrupulously builds a richly textured picture of a provincial Victorian town, populating it with people whose struggles with love, relationships, and their own ambitions are instantly recognizable. Following are some classic quotes from Middlemarch, a novel that remains one of the great works of world literature:

“It is a narrow mind which cannot look at a subject from various points of view.”

“It is always fatal to have music or poetry interrupted.”

“But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

“If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence.”

“And, of course men know best about everything, except what women know better.”

“We mortals, men and women, devour many a disappointment between breakfast and dinner-time; keep back the tears and look a little pale about the lips, and in answer to inquiries say, “Oh, nothing!” Pride helps; and pride is not a bad thing when it only urges us to hide our hurts— not to hurt others.”

“What loneliness is more lonely than distrust?”

“And certainly, the mistakes that we male and female mortals make when we have our own way might fairly raise some wonder that we are so fond of it.”

Middlemarch by George Eliot on Amazon

“People are almost always better than their neighbors think they are.”

“But what we call our despair is often only the painful eagerness of unfed hope.”

“One can begin so many things with a new person! — even begin to be a better man.”

“To be a poet is to have a soul so quick to discern, that no shade of quality escapes it, and so quick to feel, that discernment is but a hand playing with finely-ordered variety on the chords of emotion–a soul in which knowledge passes instantaneously into feeling, and feeling flashes back as a new organ of knowledge.”

“Confound you handsome young fellows! You think of having it all your own way in the world. You don’t understand women. They don’t admire you half so much as you admire yourselves.”

See also: The Literary Friendship of George Eliot and Harriet Beecher Stowe

“Our deeds still travel with us from afar/And what we have been makes us what we are.

“We are all humiliated by the sudden discovery of a fact which has existed very comfortably and perhaps been staring at us in private while we have been making up our world entirely without it.”

“If youth is the season of hope, it is often so only in the sense that our elders are hopeful about us; for no age is so apt as youth to think its emotions, partings, and resolves are the last of their kind. Each crisis seems final, simply because it is new. We are told that the oldest inhabitants in Peru do not cease to be agitated by the earthquakes, but they probably see beyond each shock, and reflect that there are plenty more to come.”

“For pain must enter into its glorified life of memory before it can turn into compassion.”

“Sane people did what their neighbors did, so that if any lunatics were at large, one might know and avoid them.”

“The troublesome ones in a family are usually either the wits or the idiots.”

“It is an uneasy lot at best, to be what we call highly taught and yet not to enjoy: to be present at this great spectacle of life and never to be liberated from a small hungry shivering self—never to be fully possessed by the glory we behold, never to have our consciousness rapturously transformed into the vividness of a thought, the ardor of a passion, the energy of an action, but always to be scholarly and uninspired, ambitious and timid, scrupulous and dim-sighted.”

You may also enjoy: Silly Novels by Lady Novelists: An Essay by George Eliot (1856)

“That element of tragedy which lies in the very fact of frequency, has not yet wrought itself into the coarse emotion of mankind; and perhaps our frames could hardly bear much of it. If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence. As it is, the quickest of us walk about well wadded with stupidity.”

“Blameless people are always the most exasperating.”

“When a man has seen the woman whom he would have chosen if he had intended to marry speedily, his remaining a bachelor will usually depend on her resolution rather than on his.”

“After all, the true seeing is within.”

“Pride helps us; and pride is not a bad thing when it only urges us to hide our own hurts—not to hurt others.”

“Certainly the determining acts of her life were not ideally beautiful. They were the mixed result of young and novel impulse struggling amidst the conditions of an imperfect social state, in which great feelings will often take the aspect of error, and great faith the aspect of illusion.”

“Character is not cut in marble – it is not something solid and unalterable. It is something living and changing, and may become diseased as our bodies do.”

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from Middlemarch by George Eliot appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 20, 2018

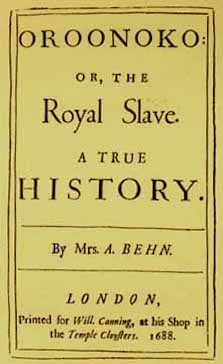

Aphra Behn and the Beginnings of a Female Narrative Voice

Aphra Behn (1640 – 1689) is a forerunner in English literary history in more ways than one; she is not only the first professional woman writer, she is also an important innovator in the form of the novel. Using the epistolary form of Lettres Portugaises as a model and combining it with elements of the drama, with Love Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister she created the first true epistolary novel. In Oroonoko she used a narrative voice that combined proximity to her readers with an unusual wealth of detail, while the plot itself involves one of the first examples of the concept of the “noble savage” in literature.

In her search for a prose form appropriate to stories with contemporary rather than purely heroic settings and themes, Behn wrote her novels in a conversational tone strewn with personal references such as “I have already said…” or “I forgot to ask how…” making the narrative resemble an ongoing conversation with her readers and lending her tales a more everyday tone than was usually the case in earlier prose forms.

The presence of the narrator

In addition, the presence of the narrator as the interpreter of the story makes her a part of the narrative herself. In Behn’s works, this presence goes beyond that of an authorial narrative strategy, however; the narrator frequently takes part in the story as well. Behn’s narrative strategy is the predecessor of the omniscient narrative voice such as that used by Henry Fielding, Jane Austen, and George Eliot. On the other hand, Behn’s narrator is more intrusive and relates events in such a way to emphasize the narrating voice.

Despite Behn’s important innovations in prose narrative, her literary reputation lags far behind her accomplishments. The sixth edition of the Norton Anthology of English Literature, published in 1990, still did not contain a single work by Behn, and as Anglo-American literary critics are well aware, the two heavy volumes of the Norton Anthology are the physical incarnation of the literary canon in English.

Since the publication of the Behn biographies* from Maureen Duffy (The Passionate Shepherdess,1979) and Angeline Goreau (Reconstructing Aphra, 1980), research on Behn has experienced a renaissance, particularly among feminist critics, Love Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister (1684 – 87) has been reprinted by Virago Press, and five of her plays in paperback by Methuen, making these works more readily available. Fortunately, the feminist interest in Behn is not letting up; unfortunately, it still seems to be primarily of feminist interest.

Chameleon in a Mirror on Amazon:

A time travel novel about Aphra Behn by Ruth Nestvold

The female voice and the rise of the novel

Numerous feminist disciplines have shown that the interests of women in a patriarchal society are rarely taken into account. The traditional view of history, for example, is that it is the story of great political events; by contrast, feminist historians have tried to uncover evidence of women in this chronicle of great events and looked into the circumstances of women’s lives through the centuries.

Now “everyday life” is becoming a more prominent concern of mainstream historians as well. The situation in the history of the novel is quite different, however. Several women authors at the end of the seventeenth and the beginning of the eighteenth century made important contributions to the development of the English novel, and the genre has always shown a concern for and an interest in domestic arrangements. As opposed to history, the protagonists of the novel have been women as often as they have been men, and the story of the woman trapped in social constraints became a particularly novelistic subject …

The English novel was a product of several differing literary traditions, among them the French romance, the Spanish picaresque tale and novella, and such earlier prose models in English as John Lyly’s Euphues (1579), Sir Philip Sidney’s Arcadia (1590) and John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1684). The authors of these works collectively helped pave the way for the form of the novel as it is known today.

Full text of Oroonoko (1688)

The true pioneers of the novel form, however, were the women writers pursuing their craft in opposition to the classically refined precepts of the writers defining the Augustan Age.

Particularly influential were Aphra Behn’s travel narrative Oroonoko (1688) and her erotic epistolary novel Love Letters Between a Nobleman and his Sister (1683). In Oroonoko, Behn provides numerous details of day to day life and a conversational narrative voice, while with Love Letters she pioneered the epistolary form for a longer work of fiction, over fifty years before Richardson.

A few women authors influenced by Aphra Behn

The political prose satires of Delariviere Manley were racy exposés of high-society scandals written in the tradition of Love Letters, Behn’s erotic roman à clef. Manley’s novels The Secret History of Queen Zarah and the Zaraians (1705) and The New Atalantis (1709) were widely popular in their day and helped create an audience for prose narratives that was large enough to support the new breed of the professional novelist.

Eliza Haywood also began her career writing erotic tales with an ostensibly political or high society background. Her first novel, Love in Excess (1719) went through four editions in as many years. In the thirties, her writing underwent a transformation suitable to the growing moral concerns of the era, and her later novels show the influence of her male contemporaries Richardson and Fielding (this despite the fact that she may have been the author of Anti-Pamela (1741), an early attack on Richardson’s first novel).

Haywood’s The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless (1751) in particular belongs in a more realistic tradition of writing, bringing the action from high society into the realm of the middle class, and abandoning the description of erotic encounters.

Particularly interesting among the work of early women novelists is that of Jane Barker. Her novel Loves Intrigues: Or, The History of the Amours of Bosvil and Galesia (1713) tells in first-person narrative the psychologically realistic tale of a heroine who doesn’t get her man. The portrayal of Galesia’s emotional dilemma, caught in a web of modesty, social circumstances and the hero’s uncertainty and indecisiveness, captures intriguing facets of psychological puzzles without providing easy answers for the readers. Galesia retreats from marriage, hardly knowing why she does so or how the situation came about, and the reader is no smarter.

Contributed © by Ruth Nestvold. Read the rest of the post by Ruth Nestvold here.

Ruth Nestvold has published widely in science fiction and fantasy, her fiction appearing in such markets as Asimov’s, F&SF, Baen’s Universe, Strange Horizons, Realms of Fantasy, and Gardner Dozois’s Year’s Best Science Fiction. Her work has been nominated for the Nebula, Tiptree, and Sturgeon Awards. In 2007, the Italian translation of her novella “Looking Through Lace” won the “Premio Italia” award for best international work.

Since 2012, she’s been concentrating her efforts on self-publishing rather than traditional publishing, although she does still occasionally sell a story the old-fashioned way. She maintains a web site at http://www.ruthnestvold.com and blogs at https://ruthnestvold.wordpress.com.

Aphra Behn page on Amazon

*Two more recent biographies

Aphra Behn: A Secret Life by Janet Todd (2017)

Aphra Behn: The English Sappho by George Woodcock (1996)

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Aphra Behn and the Beginnings of a Female Narrative Voice appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 19, 2018

5 Poems by Anne Bradstreet, Colonial American Poet

Anne Bradstreet (1612 – 1672) was one of the most prominent early American poets, and the first writer in the American colonies to be published. At a time when it was considered unacceptable for women to write, Anne rejected the prevailing ideas of women’s inferiority. She endured criticism, not for the quality of her work, but that she, a woman, dared to write. Following are five poems by Anne Bradstreet, most written in the 1650s and 1660s.

The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America (1650) was her first volume of poetry, first published in London and favorably received. Published under the pseudonym “A Gentlewoman from Those Parts,” this collection, like Anne Bradstreet’s subsequent work, reflected the duties of a Puritan woman to God, home, and family. She did so skillfully, and occasionally allowed notes of cynicism to creep in — perhaps the only form of rebellion possible for a woman of her time. For example: “I am obnoxious to each carping tongue / That says my hand a needle better fits.”

To My Dear and Loving Husband

If ever two were one, then surely we.

If ever man were lov’d by wife, then thee;

If ever wife was happy in a man,

Compare with me ye women if you can.

I prize thy love more than whole Mines of Gold,

Or all the riches that the East doth hold.

My love is such that Rivers cannot quench,

Nor ought but love from thee, give recompense.

Thy love is such I can no way repay,

The heavens reward thee manifold I pray.

Then while we live, in love lets so persevere,

That when we live no more, we may live ever.

The Author to Her Book

Thou ill-formed offspring of my feeble brain,

Who after birth did’st by my side remain,

Till snatched from thence by friends, less wise than true,

Who thee abroad, exposed to public view,

Made thee in rags, halting to th’ press to trudge,

Where errors were not lessened (all may judge).

At thy return my blushing was not small,

My rambling brat (in print) should mother call.

I cast thee by as one unfit for light,

Thy visage was so irksome in my sight;

Yet being mine own, at length affection would

Thy blemishes amend, if so I could:

I washed thy face, but more defects I saw,

And rubbing off a spot still made a flaw.

I stretched thy joints to make thee even feet,

Yet still thou run’st more hobbling than is meet;

In better dress to trim thee was my mind,

But nought save homespun cloth, i’ th’ house I find.

In this array ‘mongst Vulgars may’st thou roam.

In critic’s hands beware thou dost not come,

And take thy way where yet thou art not known;

If for thy Father asked, say thou hadst none;

And for thy Mother, she alas is poor,

Which caused her thus to send thee out of door.

The only existent portrait of Anne Bradstreet

Before the Birth of One of Her Children

All things within this fading world hath end,

Adversity doth still our joys attend;

No ties so strong, no friends so dear and sweet,

But with death’s parting blow is sure to meet.

The sentence past is most irrevocable,

A common thing, yet oh, inevitable.

How soon, my Dear, death may my steps attend.

How soon’t may be thy lot to lose thy friend,

We both are ignorant, yet love bids me

These farewell lines to recommend to thee,

That when that knot’s untied that made us one,

I may seem thine, who in effect am none.

And if I see not half my days that’s due,

What nature would, God grant to yours and you;

The many faults that well you know

I have Let be interred in my oblivious grave;

If any worth or virtue were in me,

Let that live freshly in thy memory

And when thou feel’st no grief, as I no harms,

Yet love thy dead, who long lay in thine arms.

And when thy loss shall be repaid with gains

Look to my little babes, my dear remains.

And if thou love thyself, or loved’st me,

These O protect from step-dame’s injury.

And if chance to thine eyes shall bring this verse,

With some sad sighs honour my absent hearse;

And kiss this paper for thy love’s dear sake,

Who with salt tears this last farewell did take.

Anne Bradstreet page on Amazon

In Memory of My Dear Grandchild Elizabeth Bradstreet,

Who Deceased August, 1665 Being a Year and a Half Old

Farewell dear babe, my heart’s too much content,

Farewell sweet babe, the pleasure of mine eye,

Farewell fair flower that for a space was lent,

Then ta’en away unto eternity.

Blest babe why should I once bewail thy fate,

Or sigh the days so soon were terminate;

Sith thou art settled in an everlasting state.

By nature trees do rot when they are grown.

And plums and apples thoroughly ripe do fall,

And corn and grass are in their season mown,

And time brings down what is both strong and tall.

But plants new set to be eradicate,

And buds new blown, to have so short a date,

Is by His hand alone that guides nature and fate.

In Reference to Her Children, 23 June 1659

I had eight birds hatched in one nest,

Four cocks there were, and hens the rest.

I nursed them up with pain and care,

Nor cost, nor labour did I spare,

Till at the last they felt their wing,

Mounted the trees, and learned to sing;

Chief of the brood then took his flight

To regions far and left me quite.

My mournful chirps I after send,

Till he return, or I do end:

Leave not thy nest, thy dam and sire,

Fly back and sing amidst this choir.

My second bird did take her flight,

And with her mate flew out of sight;

Southward they both their course did bend,

And seasons twain they there did spend,

Till after blown by southern gales,

They norward steered with filled sails.

A prettier bird was no where seen,

Along the beach among the treen.

I have a third of colour white,

On whom I placed no small delight;

Coupled with mate loving and true,

Hath also bid her dam adieu;

And where Aurora first appears,

She now hath perched to spend her years.

One to the academy flew

To chat among that learned crew;

Ambition moves still in his breast

That he might chant above the rest

Striving for more than to do well,

That nightingales he might excel.

My fifth, whose down is yet scarce gone,

Is ‘mongst the shrubs and bushes flown,

And as his wings increase in strength,

On higher boughs he’ll perch at length.

My other three still with me nest,

Until they’re grown, then as the rest,

Or here or there they’ll take their flight,

As is ordained, so shall they light.

If birds could weep, then would my tears

Let others know what are my fears

Lest this my brood some harm should catch,

And be surprised for want of watch,

Whilst pecking corn and void of care,

They fall un’wares in fowler’s snare,

Or whilst on trees they sit and sing,

Some untoward boy at them do fling,

Or whilst allured with bell and glass,

The net be spread, and caught, alas.

Or lest by lime-twigs they be foiled,

Or by some greedy hawks be spoiled.

O would my young, ye saw my breast,

And knew what thoughts there sadly rest,

Great was my pain when I you fed,

Long did I keep you soft and warm,

And with my wings kept off all harm,

My cares are more and fears than ever,

My throbs such now as ‘fore were never.

Alas, my birds, you wisdom want,

Of perils you are ignorant;

Oft times in grass, on trees, in flight,

Sore accidents on you may light.

O to your safety have an eye,

So happy may you live and die.

Meanwhile my days in tunes I’ll spend,

Till my weak lays with me shall end.

In shady woods I’ll sit and sing,

And things that past to mind I’ll bring.

Once young and pleasant, as are you,

But former toys (no joys) adieu.

My age I will not once lament,

But sing, my time so near is spent.

And from the top bough take my flight

Into a country beyond sight,

Where old ones instantly grow young,

And there with seraphims set song;

No seasons cold, nor storms they see;

But spring lasts to eternity.

When each of you shall in your nest

Among your young ones take your rest,

In chirping language, oft them tell,

You had a dam that loved you well,

That did what could be done for young,

And nursed you up till you were strong,

And ‘fore she once would let you fly,

She showed you joy and misery;

Taught what was good, and what was ill,

What would save life, and what would kill.

Thus gone, amongst you I may live,

And dead, yet speak, and counsel give:

Farewell, my birds, farewell adieu,

I happy am, if well with you.

Anne Bradstreet, as much later imagined in an 1898 book

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 5 Poems by Anne Bradstreet, Colonial American Poet appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 18, 2018

Mary Shelley

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (August 30, 1797 – February 1, 1851) born Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, was born in London, England and is best known for her classic thriller, Frankenstein. Born to philosopher and political writer William Godwin and famed feminist Mary Wollstonecraft (author of The Vindication of the Rights of Woman), she and her half-sister, Fanny Imlay, (Wollstonecraft’s daughter from an affair she had with a soldier) were raised mainly by her father after her mother passed away ten days after giving birth to Mary.

Mary Shelley’s work crossed several genres (essays, biographies, short stories, and dramas) and often contained autobiographical elements.

Early life

After Mary’s father remarried to Mary Jane Clairmont in 1901, the family dynamic changed. Clairmont brought her own two children into the household, and she later had a son with Mary’s father. Mary never got along with her stepmother, who favored her own children over Mary and her step-sister, sending them away to school and neglecting to educate the others.

Mary gravitated towards writing as a creative outlet. According to The Life and Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft, she once explained that “As a child, I scribbled; and my favourite pastime, during the hours given me for recreation, was to ‘write stories.'” She published her first poem, “Mounseer Nongtongpaw,” in 1807, through her father’s company.

Marriage to Percy Shelley

In 1814, Mary began a relationship with poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. A devoted student of her father, Percy Shelley soon focused his attention on Mary. Still married to his first wife, he and the teenaged Mary fled to travel Europe together, and eventually returned to England, despite her father’s deep disapproval of the union. Ostracized from the family and sinking into debt, Mary became pregnant in 1815. The couple lost the baby a few days after her birth.

Later that year, Mary suffered the loss of her half-sister Fanny who committed suicide. A short time after, Percy’s wife committed suicide. Now able to wed, in December 1816 Mary and Percy married. Soon after she published a travelogue of their escape to Europe, History of a Six Weeks’ Tour (1817) while continuing to work on her soon-to-be-famous Frankenstein.

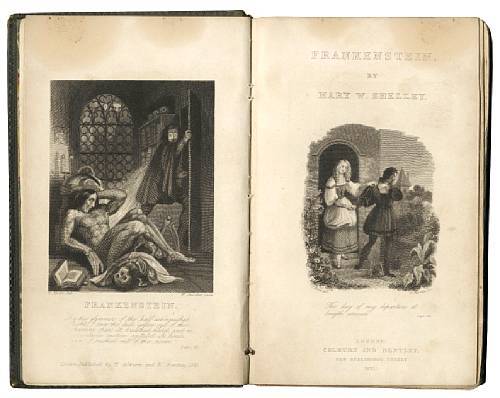

In 1818, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus debuted as a new novel from an anonymous author. Many thought that Percy Bysshe Shelley had written it since he penned its introduction. Needless to say, the book was a huge success.

See also: How Mary Shelley Came to Write Frankenstein

Frankenstein — her lasting legacy

In the midst of her tumultuous, tragic, and romantic youth, Mary created Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, one of the most memorable stories of all time. While in Switzerland with Shelley and Lord Byron in 1816, it was proposed that the members of the literary group each write a tale with supernatural elements. Mary herself tells of how she came to write Frankenstein. This, her first and most iconic novel was published in 1818 when she was barely twenty-one is still widely read and studied.

Frankenstein has been referenced and reworked in numerous formats, though the Hollywood versions bare scant resemblance to the original. A novel filled with universal themes like creation, maternal instinct, and death, it’s a pioneer in the tradition of the Gothic novel. The struggle between good and evil lies at the root of the story.

Tragic turns

Mary’s own story took even more tragic turns. She and Percy had five children in total, three of whom died before age three. In 1822, on an ocean voyage, Percy Shelley’s craft was lost at sea; his body was recovered days later. The loss was devastating.

In an 1824 journal entry, she wrote: “At the age of twenty-six I am in the condition of an aged person — all my old friends are gone … & my heart fails when I think by how few ties I hold to the world…”

Quotes from Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

Other works

Mary Shelley’s reputation is so bound with her first novel that it often goes unacknowledged that she was quite prolific. Following Frankenstein were the novels Valperga, or the Life and Adventures of Castruccio, Prince of Lucca (1823), a historic tale; The Last Man (1826), a rather dystopian novel about the spread of pestilence on humanity (the main character of this tale, Adrian, is thought to be based on Shelley); The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck (1830); Lodore (1835); and Falkner (1837).

Nonfiction works include Journal of a Six Weeks Tour (which covers the flight to Europe by the couple in 1814), and Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840–1842–1843.

Later years

Mary returned to London in 1823, the year after her husband died. She lived out her life with their one surviving son, Percy Florence Shelley. She and Percy Florence were quite close and devoted to one another.

She continued to eke out a living as a writer. After some time, Sir Timothy Shelley, her father-in-law, gave her an allowance on the condition that she refrain from writing a full biography of her husband. However, in 1838, she edited Shelley’s works and provided much valuable insight on his life and work. She also managed to put their son Percy through Harrow, and Cambridge University.

Perhaps she lived by the words in her novel, The Last Man (1826):

“A truce to philosophy! — Life is before me, and I rush into possession. Hope, glory, love, and blameless ambition are my guides, and my soul knows no dread. What has been, though sweet, is gone; the present is good only because it is about to change … ”

Mary Shelley died from a brain tumor in London in 1850, at age 53. Her other novels and writings have received renewed interest, especially since the 1970s.

More about Mary Shelley on this site

How Mary Shelley Came to Write Frankenstein (1818)

Quotes from Frankenstein (1818) by Mary Shelley

Major Works

Frankenstein

Falkner

Valperga

The Last Man

Maurice

More Information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Mary Shelley’s books on Goodreads

Read and listen online

Mary Shelley on Project Gutenberg

Mary Shelley on Librivox

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Mary Shelley appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 15, 2018

Maud Hart Lovelace

Maud Hart Lovelace (April 26, 1892 – March 11, 1980) was an American author best known for the Betsy-Tacy series of books for girls. Born and raised in Mankato, Minnesota, she enjoyed a happy childhood filled with friends, culture, and a loving family. She was the middle of three children born to Thomas and Stella (Palmer) Hart. As soon as she could hold a pencil, she began writing stories and poems.

Maud Hart started her college studies at the University of Minnesota but shortly thereafter had to withdraw when she came diagnosed with appendicitis. More than willing to take a break from her studies and continue her recuperation at her maternal grandmother’s home, she escaped to the sun and warmth of California to rest and recover.

She preferred writing to college

After an uncle loaned her a typewriter, she soon wrote her first story, Number Eight. Only 18 years old at the time, she sold it to the Los Angeles Times Sunday Magazine for ten dollars. This stroke of good fortune paved the way for her writing ambitions.

Once recuperated and back to her studies, Maud continued to write and sell stories. College soon seemed less of a draw. She dropped out for good and instead she traveled solo to Europe to gather inspiration for her writing.

During her inspiring year in Europe in 1914, Maud met Paolo Conte, an Italian musician, who later inspired the character Marco in Betsy and the Great World.

See also: Quotes from Maud Hart Lovelace’s Betsy Novels

Returned home to find great love

Maud returned to Minneapolis at the outbreak of World War I and began working for a fundraising program headed by Mrs. Harry B. Wakefield, the wife of the city editor of the Minneapolis Tribune. It was the spring of 1917 and the Wakefield Publicity Bureau offered Maud a steady day job. She was hired to replace Delos Lovelace, a young writer who was headed off for First Officers Training Camp. At a dinner hosted to hand off the position, the two hit it off and were married before the year was out when Maud was 25 years old. The couple lived apart until 1919, due to Delos’ military service.

They returned to live in Minnesota a few years later and Maud began writing historical novels. Her first novel, The Black Angels, was published in 1926. Several more novels followed over the next decade, including three written with Delos.

Later, the couple divided their time between Minneapolis and New York for several years. After 1928, they lived in New York permanently until their retirement in Claremont, California.

The couple had one daughter, Merian (born in 1931) who was named after Delos’s friend Merian C. Cooper.

A fortuitous match in many ways, Maud Hart and Delos Lovelace collaborated on several books while she continued to write and sell short stories. The author’s own childhood inspired the bedtime stories she told their young daughter and eventually, she set them down in writing.

Betsy, Tacy, and Deep Valley

Not relying only on memory, Maud drew from the copious diaries and scrapbooks she’d kept growing up. Betsy was modeled after herself; Tacy after her best friend, Bick Kenney. Their town of Mankato became “Deep Valley.” Betsy-Tacy, the first of the series, was published in 1940 to immediate and resounding success.

The last book in the series, Betsy’s Wedding, was published in 1955. Maud had planned to write Betsy’s Bettina, but she eventually chose not to. It is possible that the miscarriage of her first child, a son, more than ten years before Merian’s birth, influenced her decision. She wrote to a friend that the last lines of Betsy’s Wedding “were a perfect ending for the series”:

“She was in the land of dreams now, Betsy thought. The future and the past seemed to melt together. She could feel the Big Hill looking down as the Crowd danced at Tib’s wedding in the chocolate-colored house.”

By this time, Maud was a seasoned author, having published numerous short stories and historical novels for adults. But it was the Betsy-Tacy series that sealed her legacy. Historical accuracy and detail were the threads that ran through her work, fiction and nonfiction, and her books for younger readers. Generations of readers have responded to the depiction of Betsy and her friends as creative, independent girls who valued friendship and loyalty.

Descriptions of music, books, plays, fashion, architecture, and social customs of the times in which these stories take place add to their immense charm. The books in this series, ten in all, have inspired such devotion that there is to this day a Betsy-Tacy Society that maintains the childhood homes of Maud Hart Lovelace and her friend Bick Kenney in Mankato, Minnesota, as well as protecting the author’s legacy.

Maud Hart Lovelace page on Amazon

Later years

Maud and Delos Lovelace moved from their home of many years in New York City to Claremont, California in 1952 after he retired from newspaper work. They enjoyed the stimulating atmosphere of the college town, founded its first Episcopal Church, and became involved with the Civil Rights movement.

When Delos Lovelace died in 1967 the couple was just shy of their 50th wedding anniversary. Maud Hart Lovelace remained in California, where she died in 1980. She is buried in the Glenwood Cemetery in Mankato, with a monument dedicated to her.

More about Maud Hart Lovelace on this site

Quotes from Maud Hart Lovelace’s Betsy Novels

Major works

The Black Angels (1926)

Early Candlelight (1929)

Petticoat Court (1930)

The Charming Sally (1932)

Carney’s House Party (1949)

Emily of Deep Valley (1950)

Betsy-Tacy series

Betsy-Tacy (1940)

Betsy-Tacy and Tib (1941)

Betsy and Tacy Go Over the Big Hill (1942)

Betsy and Tacy Go Downtown (1943)

Heaven to Betsy (1946)

Betsy in Spite of Herself (1946)

Betsy Was a Junior (1947)

Betsy and Joe (1948)

Betsy and the Great World (1952)

Betsy’s Wedding (1955)

Biographies

The Betsy-Tacy Companion: A Biography of Maud Hart Lovelace

by Sharla Scannell Whalen (1995)

More information

Wikipedia

Maud Hart Lovelace’s Deep Valley

Maud Hart Lovelace Society

Betsy-Tacy’s Deep Valley: All Things Maud Hart Lovelace, etc.

The Betsy-Tacy Society (Mankato, MN)

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Maud Hart Lovelace appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 14, 2018

Tillie Olsen

Tillie Olsen (January 14, 1912 – January 1, 2007) was an American author of fiction and nonfiction whose body of work was small but influential, drawing upon her personal experiences. Her work spoke to the struggles of women and working-class families, placing her in the canon of second-wave feminist literature. While her birth was never recorded officially, it’s been determined she was born in either 1912 or 1913.

Born Tillie Lerner in Omaha, Nebraska, she was the second child of Ida Goldberg and Sam Lerner, Russian-Jewish immigrants. Her father, a laborer, was the Secretary of Nebraska’s Socialist party. Her parents’ socialist views and activism impacted Olsen’s childhood and influenced her later life.

Growing up fast

There was never a time when she was not doing something to help the family out financially. As a 10-year-old she had to work shelling peanuts after school. As the second oldest of six children, Olsen was responsible to take care of her younger siblings from an early age.

Spirited, wild, and rebellious, Tillie gained popularity by producing a humor column in the high school newspaper, writing as “Tillie the Toiler.” She eventually dropped out to begin working to help support her parents and siblings. She worked at various blue-collar jobs including factory work, waitressing, and as a hotel maid.

She became politically active in her mid-teens as a writer for the Young Socialist League. In 1931, at age 18, she joined the Young Communist League. She attended the Party school for several weeks in Kansas City, where she began working in a tie factory. During this time Olsen was jailed for a month for distributing leaflets to packinghouse workers and, while in prison, was beaten up by one inmate for attempting to help another. Already weak from having contracted pleurisy and tuberculosis from the factory work conditions, she became so extremely ill that the Party sent her back to Omaha to recuperate.

While recovering, Olsen started writing her first novel, Yonnondio, which was to be put away for decades to come. That same year, she gave birth to the first of her four daughters.

Challenging times as a wife and mother

Olsen moved to San Francisco in 1933 and continued her pro-labor activism. She was arrested during the 1934 general strike and dispatched reports to The New Republic and The Partisan Review. It was then that she met Jack Olsen, another activist, whom she later married.

The couple married in 1944 and had three more daughters (she would eventually come to have many grandchildren and great-grandchildren). Olsen, working at various jobs to help support the family, found it challenging to be a mother and working to earn a living. She longed for time to write and made no secret of her frustration, which often shaded into bitterness.

Tell Me a Riddle

She didn’t have a book-length work published until 1961 when Tell Me a Riddle appeared. A collection of four short stories, it opened with “I Stand Here Ironing,” a first-person narrative of the frustration of motherhood, isolation, and poverty.

The last piece in the collection, “Tell Me a Riddle,” is arguably her best-known work. It’s the story of a working-class couple that also poignantly explores the author’s favored themes of poverty and gender. The slender short story received much critical acclaim. “Tell Me a Riddle” was adapted into a 1980 movie starring Melvyn Douglas and Lila Kedrova.

Silences

In Silences (1978), a collection of linked essays, Olsen looked at women authors of the past to comment on how societal and financial circumstances affected their creative lives. She also examined how marriage and motherhood impacted output and chances for success. Issues of gender and class were central to these meditations. Margaret Atwood wrote of the book: “It begins with an account, first drafted in 1962, of her own long, circumstantially enforced silence. She did not write for a very simple reason: A day has 24 hours. For 20 years she had no time, no energy and none of the money that would have bought both.”

See also: Silences by Tillie Olsen: On Being a Writer and a Mother

A biographical reckoning

A post in the Jewish Daily Forward —A Brutal Narcissist: The Life of Feminist Icon Tillie Olsen — tells of biographer Panthea Reid’s decade-long journey to research and write Tillie Olsen: One Woman, Many Riddles. The article states that the biographer’s “initial admiration for Olsen disintegrated as time progressed.

Overcoming her resistance to seeing one of her heroines dethroned, Reid paints a harsh portrait of a self-involved and difficult woman who could often be manipulative and deceptive and brutally narcissistic.” The book ultimately paints a portrait of a woman who was self-involved, didn’t finish promised projects, and who could alienate those closest to her.

Olsen loved attention and famously hogged the spotlight at events and literary gatherings.

Later life and legacy

Olsen also worked to restore forgotten, out-of-print women’s writing. She influenced several Feminist Press reprintings, including Rebecca Harding Davis’s Life in The Iron Mills (1972).

Ironically, after longing to write for two frustrating decades, once she did produce a few works, she published almost nothing after Silences. Despite her modest output, Olsen was invited to teach and to be writer-in-residence at a number of colleges and universities, including Stanford, MIT, Amherst College, and Kenyon College.

She received nine honorary degrees, a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, a Guggenheim, and several other prestigious awards.

Olsen’s few works have been a staple in literature and women’s studies courses. She died in Oakland, California in 2007, at the age of 94.

More about Tillie Olsen on this site

Silences: On Being a Writer and a Mother

Quotes by Tillie Olsen

Major Works

Yonnondio: From the Thirties

Tell Me a Riddle

Silences

Mother to Daughter, Daughter to Mother

Biography

Tillie Olsen: One Woman, Many Riddles by Panthea Reid

More information

Wikipedia

Tillie Olsen Interview – The Progressive

Reader discussion of Tillie Olsen’s books on Goodreads

Tillie Olsen, Feminist Writer, Dies at 94

A Brutal Narcissist: The Life of Feminist Icon Tillie Olsen

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Tillie Olsen appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 12, 2018

4 Classic Horse Stories by Women Authors

What is it about horse stories that kids, and dare we say especially girls, love so much? There’s something grounding and down to earth about the bond between the beautiful animals and humans devoted to their welfare when translated to fiction.

Here, we’ll take a quick look at four of the most enduring classic horse stories, the novels Black Beauty by Anna Sewell, National Velvet by Enid Bagnold, My Friend Flicka by Mary O’Hara, and Misty of Chincoteague by Marguerite Henry.

Though they’re now classified as children’s books, they were intended by their authors to be enjoyed by “children of all ages.” Perhaps that’s one of the reasons why they were all adapted to film, reaching wide and appreciative audiences.

Black Beauty by Anna Sewell (1877)

More about Black Beauty

Black Beauty on Amazon

Though Black Beauty by Anna Sewell is one of the best-selling children’s classics of all time, Anna Sewell hadn’t intended as a children’s book. She wrote it for those who owned or worked with horses, “to induce kindness, sympathy, and an understanding treatment of horses.”

The story is told by the horse; it was, after all, subtitled The Autobiography of a Horse. Beauty shares his thoughts and feelings and thoughts as his story unfolds. His idyllic existence as he grows from a colt frolicking in the fields with his mother into a full-grown horse comes to an end. He falls on hard times, in spite of his devotion to his owners and his hard-working ways. Beauty passes through various masters— some kind, some careless, and others quite cruel. This moving story of Black Beauty’s quest for love and kindness, told from his own perspective, had inspired generations of readers to gain more empathy for animals. There have been numerous film adaptations and spinoffs of Black Beauty.

National Velvet by Enid Bagnold (1935)

More about National Velvet

National Velvet on Amazon.com

National Velvet by Enid Bagnold stars 14-year-old Velvet Brown, the daughter of a working-class family in England. She’s so horse-crazy that she imagines herself taking journeys on them, leading them to pastures, and grooming them. Miraculously she wins a piebald horse in the village raffle, and at the same time inherits five other horses from a rich old gentleman.

Velvet and Mi Taylor, her father’s hired man, train the unruly piebald horse to race in the Nationals. However unlikely, the story of overcoming long odds to realize a dream, has captured the imagination of generations of readers. In her breakout role, a young Elizabeth Taylor starred as Velvet Brown in the 1944 film version of National Velvet.

My Friend Flicka by Mary O’Hara (1941)

More about Mary O’Hara

My Friend Flicka on Amazon

My Friend Flicka, the 1941 novel by Mary O’Hara, was this author’s most enduring work. The ranch life and rugged Wyoming backdrop that she actually experienced inspired the novel. It’s the story of Ken McLaughlin, a rancher’s son, and his horse Flicka. Ken’s father, a practical Scotsman, had no patience for his son’s dreaminess, so out of place in the harsh realities of the family’s horse breeding farm. Ken was smitten with a wild colt, who he called Flicka, meaning “little filly.” His devotion to the horse and to taming her grows along with his acceptance of responsibility as a young man.

My Friend Flicka became part of a trilogy, followed by Thunderhead (1943) and Green Grass of Wyoming (1946). My Friend Flicka was the basis of a successful 1943 film starring Roddy MacDowell. It was a 1956-57 television show and was re-run throughout the 1960s.

Misty of Chincoteague by Marguerite Henry

Misty of Chincoteague on Amazon

Misty of Chincoteague by Marguerite Henry (1947) is set in the island town of Chincoteague, Virginia. It’s the story of Paul and Maureen Beebe, orphan siblings, who work to earn enough money to by Phantom, a wild pony mare. The children save Phantom from a cruel fate and raise Misty, her filly born. Misty was inspired by a real-life pony of the same name, and real events and people of Chincoteague.

Marguerite Henry followed the success of this book with a series of sequels about Misty, including one about her own foal, Stormy. A 1961 film titled Misty was based on the book.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 4 Classic Horse Stories by Women Authors appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 5, 2018

12 Lesser-Known Classic Women Novelists Worth Rediscovering

On the subject of classic women novelists worth rediscovering, we could make the argument that ninety percent of the authors on this site are ripe for rediscovery. Some authors are still read and considered, even if only in the academic realm of women’s studies classes. These include Zora Neale Hurston who was indeed rediscovered after falling into obscurity, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman, whose story The Yellow Wallpaper is an iconic work of feminist literature.

A few (not enough!) women authors’ books are still staples in and out of the classroom including To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee and The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck. Then there are the ever-respected Virginia Woolf, and of course, the beloved Jane Austen and the Brontë sisters.

Sadly, though, there are quite a number of women who were widely read in their time but have fallen under the literary radar. Here are 12 of them — classic women novelists who whose books deserve to be read and enjoyed just today as much as they were in their time.

Jessie Redmon Fauset (1882 – 1961) was an American editor, poet, essayist, and novelist who was deeply involved with the Harlem Renaissance literary movement. She wrote four novels about race and class, the best known of which was arguably Plum Bun.

Edna Ferber (1885 – 1968), American novelist and playwright, was considered one of the most successful mid-20th-century authors Her sprawling novels each captured a slice of Americana, and several became famous films, including Giant and Show Boat.

Miles Franklin (1879 – 1954) was an Australian author with a feminist bent. Her best-known novel, My Brilliant Career, is the story of a teenage girl growing up in the Australian bush in the late 1800s still seems fresh and relevant today. It was adapted into a charming 1979 film.

Rumer Godden (1907 – 1998), the British-born novelist and memoirist, was raised mainly in India at the height of colonial rule. A mid-20th-century favorite whose novels melded the commercial and literary; nine of them, including In This House of Brede, became films.

Laura Z. Hobson (1900 – 1986) is an author whose name has been eclipsed by her best-known novel, Gentleman’s Agreement. The film version went on to win multiple Academy Awards. Laura wrote a number of other fascinating and readable novels that have fallen into obscurity.

Nella Larsen (1891 – 1964), was an American author associated with the Harlem Renaissance movement. She only wrote two novels — Quicksand (1928) and Passing (1929), both of which are back in print! These exquisite short novels about race and identity are worth enjoying as well as studying.

Ann Petry (1908 – 1997) was the first African-American woman to produce a book (The Street) whose sales topped one million. At its peak, the 1946 novel sold 1.5 million copies and was reissued in 1992. Her three other novels also depicted slices of black life in America.

Jean Rhys (1890 – 1979) is best remembered for Wide Sargasso Sea, considered a prequel to Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. She wrote other novels, but her imagining of how Rochester’s wife came to be “the madwoman in the attic” is her most remarkable.

May Sarton (1912 – 1995), might be better known for her memoir series that began with Plant Dreaming Deep, but she was also a pioneer of modern queer fiction. Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing was pretty radical for 1965 and The Education of Harriet Hatfield could still have been ahead of its time in 1989.

Margery Sharp (1905 – 1991), once a popular British author, wrote in the comic novel genre. Recently some of her novels, including Cluny Brown, were reissued in new editions. She was also known for The Rescuers series for children, two of which were adapted into animated Disney films.

Dodie Smith (1896 – 1990) was a British novelist and playwright. Surely you’ve heard of The Hundred and One Dalmatians (later better known as The 101 Dalmatians), and perhaps even the young adult novel I Capture the Castle. She has other titles to her credit as well, all worth another look.

Elizabeth von Arnim (1866 – 1941), an Australian-born novelist, was best known for The Enchanted April and Elizabeth and her German Garden. Not much is known about this mysterious author, but tales of unhappy marriages told with a dry wit are still a treat to read.

The post 12 Lesser-Known Classic Women Novelists Worth Rediscovering appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 3, 2018

Quotes from A Wrinkle in Time

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle was published in 1962, but not without its share of challenges. “A Wrinkle in Time was almost never published,” Madeleine L’Engle wrote. “You can’t name a major publisher who didn’t reject it. When we’d run through forty-odd publishers, my agent sent it back. We gave up.” Editors found the fantasy novel too dark and complex for children. But the following selection of quotes from A Wrinkle in Time prove that this beloved novel is a timeless work of fiction for all ages.

Eventually, the book found its home. Published in 1962, A Wrinkle in Time is still in print, with millions of copies sold worldwide. Its legacy lives on, as it’s still in print and is the basis of the 2018 film version. It has the distinction of having won some of the most prestigious publishing awards, as well as being one of the most frequently banned books of all time.

“Life, with its rules, its obligations, and its freedoms, is like a sonnet: You’re given the form, but you have to write the sonnet yourself.”

“We can’t take any credit for our talents. It’s how we use them that counts.”

“I do not know everything; still many things I understand.”

“The only way to cope with something deadly serious is to try to treat it a little lightly.”

“Like and equal are not the same thing at all.”

See also: Madeleine L’Engle: “A Wrinkle in Time Was Almost Never Published”

“It seemed to travel with her, to sweep her aloft in the power of song, so that she was moving in glory among the stars, and for a moment she, too, felt that the words Darkness and Light had no meaning, and only this melody was real.”

“If you aren’t unhappy sometimes you don’t know how to be happy.”

“I don’t understand it any more than you do, but one thing I’ve learned is that you don’t have to understand things for them to be.”

“A book, too, can be a star, ‘explosive material, capable of stirring up fresh life endlessly,’ a living fire to lighten the darkness, leading out into the expanding universe.”

“Only a fool is not afraid.”

“The truth is that I hate to think about other people reading my books,” Miranda said. “It’s like watching someone go through the box of private stuff that I keep under my bed.”

“Experiment is the mother of knowledge.”

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle on Amazon

“Silence fell between them, as tangible as the dark tree shadows that fell across their laps and that now seemed to rest upon them as heavily as though they possessed a measurable weight of their own.”

“There’s nothing left except to try.”

“There will no longer be so many pleasant things to look at if responsible people do not do something about the unpleasant ones.”

“To love is to be vulnerable; and it is only in vulnerability and risk—not safety and security—that we overcome darkness.”

“Just because we don’t understand doesn’t mean that the explanation doesn’t exist.”

“Explanations are not easy … about things for which your civilization still has no words.”

“A straight line is not the shortest distance between two points.”

You might also like: A Ring of Endless Light by Madeleine L’Engle

“There’s very little difference in the size of the tiniest microbe and the greatest galaxy.”

“All your great artists. They’ve been lights for us to see by.”

“I am peace and utter rest. I am freedom from all responsibility.”

“Differences create problems.”

“Maybe if you aren’t unhappy sometimes you don’t know how to be happy.”

“We know nothing … We’re children playing with dynamite.”

“We do not know what things look like … We know what things are like.”

“The things which are seen are temporal … the things which are not seen are eternal.”

“You’re given the form, but you have to write the sonnet yourself.”

“Love. That was what she had that IT did not have.”

“It’s my worst trouble, getting fond. If I didn’t get fond I could be happy all the time.”

See also: Quotes by Madeleine L’Engle on Writing and the Writing Life

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from A Wrinkle in Time appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.