Nava Atlas's Blog, page 85

May 9, 2018

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Edna St. Vincent Millay (February 22, 1892 – October 19, 1950) was an American poet regarded as a major twentieth-century figure in the genre. She and her sisters were raised near coastal Maine by their single mother, who taught them to value their independence and appreciate literature, visual art, and music. Her middle name really was an homage to the New York City’s St. Vincent’s hospital, where the life of an uncle was saved before she was born.

After her parents were divorced, there was minimal contact with their father. Her mother, Cora, was frequently away from home, on the road as a visiting nurse and itinerant hairdresser. Edna and her sisters Norma and Kathleen were often left to their own devices. They made the best of the situation, turning their tasks into games. Edna’s forays into make-believe turned into a penchant for acting, which she did often and enthusiastically from childhood through her college years.

Voracious reader and precocious poet

Encouraged by her mother, Edna (who was more often called “Vincent” in her youth) immersed herself in great works of literature from an early age. She read Shakespeare, Keats, Longfellow, Shelley, and Wordsworth. At age of sixteen she compiled a dozen or so poems into a copybook and presented them to her mother as “Poetical Works of Vincent Millay.” The poems were mainly sonnets, a form that she would favor throughout her life as a poet.

In 1912, encouraged by her mother, 19-year-old Edna sent her poem, “Renascence” to The Lyric Year, a magazine that held a yearly poetry contest and published winning entries. The narrator of the poem writes from a mountaintop from which she observes the broad vista. Its lines consider human suffering and death, and after a refreshing rain, the narrator is once again able to experience joy and a rebirth of life — thus the title, “Renascence.”

The poem was accepted and included in the collection. Though it took only fourth place (causing quite a scandal), it caught the attention not only of readers who felt Edna was robbed of the top prize, but of Caroline Dow, a wealthy patron of the arts. Taken with Edna’s passion for poetry, Dow arranged to pay her tuition to attend Vassar College. Edna would otherwise not have been able to afford college.

Vassar College and Greenwich Village

Edna entered college at age 21, and soon became aware of her power to attract, and used this to her advantage. According to J.D. McClatchley, editor of Edna St. Vincent Millay: Selected Poems (2002):

“‘People fall in love with me … and annoy me and distress me and flatter me and excite me.’ And she responded in kind; there were torrid affairs with girls at school, adding to her campus notoriety, and tepid flings with older men who might help her career. Throughout her life, she did what she felt she must do in order to create the conditions necessary to accomplish her work.

After Vassar, she became the Circe of Greenwich Village. She was soon the talk of the town. She drank and partied and had affairs, and thereby was the envy of all, and to young women in particular she was the free spirit that American Babbitry had stifled.

Her affairs were sometimes of the heart, and sometimes more practical. The writers she took as lovers (and invariably kept as friends afterward) … were in a position to both teach and help her. And she had always been a quick study. The poems she wrote then — wild, cool, elusive — intoxicated the Jazz Babies. She had found the pulse of the new generation.”

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends —

It gives a lovely light!

An outpouring of poems; a feminist slant

A Few Figs from Thistles, her first major collection (1921), explored, among other themes, female sexuality. Second April (also 1921) dealt with heartbreak, nature, and death — the latter being a topic she explored often.

It’s rare for a poet to attain what we now call superstar status, but that’s just what Edna achieved. Throughout the 1920s — call them Roaring or the Jazz Age — she recited to enthusiastic, sold-out crowds during her many reading tours at home and abroad. Interspersed were head-spinning numbers of love affairs with both men and women. Edna was open about her bisexuality, which was unusual for the time.

In Europe, she posed for surrealist photographer Man Ray and dined with the artist Constantin Brancusi. It was a heady time indeed, and the candle she burned at both ends was still glowing.

Pulitzer Prize and an unconventional marriage

In 1923, Edna won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry for her fourth volume of poems, The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver. She was only the second person to receive a Pulitzer for poetry, and the first woman to win the prize.

That year, Edna also embarked on an unconventional marriage with Eugen Jan Boissevain. The handsome Dutch importer was a kindhearted man twelve years her senior, and Edna married him when, as her erstwhile lover Edmund Wilson saw it, “she was tired of breaking hearts and spreading havoc.”

Boissevain provided the support and stability Edna needed for her writing. But she wasn’t one to settle down, after all. Both she and her husband took other lovers throughout their marriage. He completely supported her career, even taking on many domestic duties and organizing their social life at the country home they purchased together, a 700-acre farm called Steepletop in Austerlitz, NY.

Protest

Edna didn’t shy away from political causes. Her New York Times obituary describes her protest against the famed Sacco and Vanzetti affair:

“In the summer of 1927 the time drew near for the execution of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Boston Italians whose trial and conviction of murder became one of the most celebrated labor causes of the United States. Only recently recovered from a nervous breakdown, Miss Millay flung herself into the fight for their lives.

A poem which had wide circulation at the time, ‘Justice Denied in Massachusetts,’ was her contribution to the fund raised for the defense campaign. Miss Millay also made a personal appeal to Governor Fuller.

In August she was arrested as one of the “death watch” demonstrators before the Boston State House … ‘I went to Boston fully expecting to be arrested — arrested by a polizia created by a government that my ancestors rebelled to establish,’ she said, when back in New York. ‘Some of us have been thinking and talking too long without doing anything. Poems are perfect; picketing, sometimes, is better.’”

Writing prolifically while wreaking havoc

Edna continued to push boundaries in her writing and her personal life. Her anti-war play Aria da Capo was performed to sell-out crowds on Cape Cod by the Provincetown Players. Her obsession with the shy young poet, George Dillon, who was gay, inspired one of her finest volumes of poetry, Fatal Interview. Published in 1931, it sold a stunning 50,000 copies in the first months of publication, a rarity for a book of poems, and during the Great Depression, at that.

Edna seemed to need to create chaos to thrive. According to J.D. McClatchley: “Millay spared no one — least of all herself — in her drive to create the kind of ‘havoc’ her poems feed on, and then to surround herself with the solitude to work that chaos into shimmering lines … Scandal, of course, only enhanced her celebrity … For women, she made complicated passion real; for men, she made it alluring.”

Life had becoming more fraught for the free-spirited poet as she reached middle age. While in Florida on working vacation with her husband, she was completing a manuscript for a new collection, Conversations at Midnight. Their hotel burned down and the manuscript was destroyed. In 1936, she was involved in a car accident that left her in such chronic pain that she became dependent on painkillers.

She was crushed when Eugen Boissevain died suddenly in 1949. The next year, she sat alone in their home, Steepletop, with a bottle of wine at the top of a staircase. She tumbled down the stairs, broke her neck, and died. It has been speculated that this may have been precipitated by a heart attack. Edna St. Vincent Millay was 58 years old and left a body of work that included some fifteen poetry collections, several plays, and many political writings.

Steepletop and the Millay Colony

A number of years after her death, the state of New York acquired a great portion of the acreage of Steepletop, and the funds were used to establish The Millay Colony for the Arts.

Today, this center offers residencies for writers and other creative artists, and has a museum dedicated to Millay’s life and work, as well as garden trails and her gravesite.

Edna St. Vincent Millay page on Amazon

More about Edna St. Vincent Millay on this site

Quotes by Edna St. Vincent Millay

Renascence by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1912)

Major Works

Renascence and Other Poems

First Figs and Other Poems

Second April

The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver

Aria da Capo, a Play in One Act

Collected Sonnets

Biographies about Edna St. Vincent Millay

Savage Beauty: The Life of Edna St. Vincent Millay by Nancy Milford

What Lips My Lips Have Kissed: The Loves and Love Poems

of Edna St. Vincent Millay by Daniel Mark Epstein

More Information

Wikipedia

Edna St. Vincent Millay Society at Steepletop

Reader discussion of Millay’s works on Goodreads

Visit

Steepletop – Austerlitz, NY

Millay Colony for the Arts – Austerlitz, NY

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Edna St. Vincent Millay appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Miles Franklin

Miles Franklin (October 14, 1879 – September 19, 1954) was an Australian author of novels and nonfiction, born Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin. Her best-known novel, My Brilliant Career, is the story of a teenage girl growing up in the Australian bush who longs to break free as her own person.

Franklin’s literary career was long but uneven, with occasional great gaps between almost feverish output. A need to support herself compelled her to work in a number of odd careers, though she often made use of her experiences in her storytelling. Critical reception of her work was also quite variable, and apparently quite sensitive to criticism, she occasionally used pseudonyms.

Early life and My Brilliant Career

Franklin was descended from Australian pioneers. She was born on her grandmother’s land near Talbingo Station and grew up on a small cattle farm owned by her father near Tumut. Later, the family moved to to Goulburn to farm dairy cattle. Originally, Franklin wished to study music, but that proved impractical, so she turned to writing. Some of the experiences of monotony and frustration that defined her girlhood on a farm made their way into her first novel, My Brilliant Career. She was only 18 years old when she finished writing it in 1899, and it was published in 1901 by Blackwoods of Edinburgh.

My Brilliant Career tells the story of Sybylla Melvyn, a high-strung, imaginative girl from the Australian countryside. When her parents fall on hard times, they send her to live with her grandmother in another part of the country. There she meets Harold Beecham. Convinced that she’s ugly and useless, Sybilla is surprised when the wealthy young man proposes marriage, but declines. Sybilla is then farmed out to be a domestic servant for a family to whom her father owes money. Despondent, she has a breakdown and returns to her parents’ home.

Beacham tracks her down and reiterates his proposal. Sybilla, determined to become a writer, once again refuses him and vows never to marry. Readers are left to ponder the possibility for themselves, for the story is open-ended.

My Brilliant Career was an immediate success, though the consequences for its author were mixed. Some of the novel’s fictional characters were only thinly veiled, causing a bit of uproar in Goulburn. Some saw the book as an attack on rural life. Most critics praised the book, however, including one who described it as “a warm embodiment of Australian life,” and “a book full of sunlight.”

Life in the U.S. and England

Franklin set off in 1906 to make her way through life in America. Settling in Chicago, she’d all but given up on the idea of becoming a writer, and began doing secretarial work for the National Women’s Trade Union League of America. Though at the time she fervently rejected labeling herself as a feminist, her work with the trade union brought her into contact with members of the feminist movement who were campaigning for women’s suffrage and agitating for better working conditions for women. One of those was Alice Henry, a fellow Australian who was in the U.S. to help further the suffrage movement. She and Franklin became close lifelong friends.

Her brief stint as a domestic servant served as the basis for her subsequent book, Everyday Folk and Dawn (1909). In the interim years, she wrote a sequel to My Brilliant Career titled My Career Goes Bung, but it proved too far ahead of its time and wasn’t published until some forty years later, in 1946.

In 1915, Franklin moved to England. Like a few of her fellow female authors who contributed to World War I efforts, she did her share. First working in slum nurseries, she later joined the Scottish Women’s Hospital Unit. Under their auspices she became an ambulance driver and served as a cook in a 200-bed tent hospital in Macedonia.

Books by “Brent of Bin Bin”

In the 1920s, Franklin traveled back and forth from Britain to Australia, always by way of the U.S. During this period, she wrote a set of historical novels set in the Australian bush and published them under the odd pseudonym “Brent of Bin Bin.” She worried that nothing she did would ever live up to the success of her freshman effort, My Brilliant Career, and may have also felt that an assumed name would shield her from negative reviews.

Under this pseudonym, Up the Country (1928), Ten Creeks Run (1929), and Back to Bool Bool (1931) came out in quick succession. This suite of Brent of Bin Bin novels would grow to six volumes, but the remaining three wouldn’t appear until the 1950s.

See also: Quotes by Miles Franklin

Return to Australia

Franklin returned to live permanently Australia in 1932, and began writing under her own name once again. All That Swagger, considered her best-known work second only to My Brilliant Career, was published in 1936.

Once she had settled back into her home country, Franklin became deeply involved in the Australian literary community. Residing in Carlton, NSW, she became a member of the Fellowship of Australian Writers, and supported literary journals such as Southerly. She was a mentor to young writers and entertained other authors in her home. She also engaged in a number of literary collaborations including a 1939 novel, Pioneers on Parade, co-written with fellow Australian writer Dymphna Cusack. She published a trio of non-fiction works, though none became as well known as her novels.

Though Franklin had a number suitors throughout her young adulthood, she never married nor had any children. In 1937, she was nominated as Officer of the Order of the British Empire, an honor she declined.

Death and legacy

Miles Franklin died in September, 1954 in New South Wales, Australia, of a coronary occlusion at the age of 75. In her obituary in the Melbourne Age, she was described as follows:

“In her lifetime, petite, slim Miles Franklin of the ready smile and quick, bright eyes always carefully parried inquiries. She is quoted as having remarked to a friend on one occasion, ‘I have always enjoyed a little mystery.’

In a recent study of Miles Franklin, Henrietta Drake-Brockman said of her, “There are no half measures about Miles Franklin. Her heart is as wide as her country’s ‘back paddocks,’ her pride as tough as a well-tanned hide, and her honesty of conviction as bright and clarifying as sunlight.”

Indeed, she seemed to like to remain a bit inscrutable. A friend who donated some of her papers to the Melbourne Library said of her: She hated humbug. She was a good friend, who did good by stealth.”

She bequeathed her estate to fund the Miles Franklin Literary Award, given annually to “a novel which is of the highest literary merit and presents Australian life in any of its phases” In 2016, the award was valued at approximately $60,000 in U.S. dollars. The first award was given in 1957.

A charming Australian film version of My Brilliant Career was released in 1979, reviving interest in Franklin’s life and works.

A novel titled On Dearborn Street was published in 1981. A love story peppered with plenty of American slang, it reflects Franklin’s years in the U.S.

More about Miles Franklin on this site

Quotes by Miles Franklin

Major works

My Brilliant Career (1901)

Some Everyday Folk and Dawn (1909)

Old Blastus of Bandicoot (1931)

All That Swagger (1936)

Pioneers on Parade (1939)

Up the Country

My Career Goes Bung (1946)

Biographies

Her Brilliant Career: The Life of Stella Miles Franklin by Jill Roe

More information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Franklin’s books on Goodreads

Film adaptation

My Brilliant Career (1979 film)

Visit

Miles Franklin Goulburn: A Self-guided Walking Tour – Goulburn, Australia

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Miles Franklin appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 8, 2018

Kate Chopin

Kate Chopin (February 8, 1850 – August 22, 1904) was an American author who made her mark writing fiction, and was best known for the novella The Awakening (1899), a work quite controversial in its time.

She was born Kate O’Flaherty in St. Louis, descended on her mother’s side from the old French families of that city. Her father was Captain Thomas O’Flaherty, a wealthy merchant active in local affairs. Kate was raised in the French and Irish traditions of Catholicism, and educated at Sacred Heart convent.

Her father died when she was around five years old, after which she developed a strong bond with her maternal lineage — her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother. Kate was an avid reader, devouring contemporary novels, fairy tales, poetry, and religious dramas.

Marriage, family, and widowhood

With her beauty and charm, Kate was considered one of the “belles of St. Louis.” Shortly after her introduction to society, she married Oscar Chopin of Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana in 1870. The couple moved to New Orleans, then lived on his Natcihtoches plantation and other parts of Louisiana. Those years found her immersed in the Creole and Cajun cultures that figured so prominently in her writing. She had six children in quick succession, from 1871 to 1879.

Oscar Chopin died in 1882, leaving her not only widowed with six young children to raise, but in extreme debt of $42,0000 — in today’s dollars equal to hundreds of thousands. She tried to make good on the plantation and general store he owned, but her mother prevailed upon her to move back to St. Louis, and she sold the businesses.

Kate Chopin’s children settled well into her bustling home city, but a year after she moved back, her mother died. Compounding the earlier stress of losing her husband and livelihood, she struggled with depression. Her family physician suggested she take up writing as an outlet. This was fortunate and somewhat surprising, for it was right around this same time that Charlotte Perkins Gilman, suffering from postpartum depression, was forbidden by her doctor to write or have any sort of creative outlet. Chopin did indeed find writing to be the therapeutic outlet she needed.

The start of a literary career

By the early 1890s, Chopin forged a successful writing career, contributing short stories and articles to local publications and literary journals. Her work found further favor in national magazines like Vogue and Atlantic Monthly. She addressed themes in women’s lives that weren’t often confronted in literature. Though she didn’t identify as a feminist, she was influenced by the strong women who raised her. In her works, women were a force to be reckoned with, and conveyed her belief that women could claim their identities apart from men.

In her writings, she was a realist and represented the world as it was in her time, avoiding the sentimentality of popular fiction. She wasn’t afraid to confront harsh themes, as she did with the issues of racism and hypocrisy in her 1893 short story “Désirée’s Baby.”

Read the full text of The Awakening (1899)

Influence of Guy de Maupessant

Kate Chopin’s major literary influence was Guy de Maupessant, A French author from Normandy best known for short stories. In his time, some of the themes he explored in his writing were sexuality, depression, and loneliness. Elements of the human condition expressed print were often taboo — and in effect, he was often considered immoral as a result. Chopin described how moved she felt after she read de Maupessant’s work:

“… I read his stories and marveled at them. Here was life, not fiction; for where were the plots, the old fashioned mechanism and stage trapping that in a vague, unthinkable way I had fancied were essential to the art of story making. Here was a man who had escaped from tradition and authority, who had entered into himself and looked out upon life through his own being and with his own eyes; and who, in a direct and simple way, told us what he saw…”

Kate Chopin page on Amazon

Literary accomplishments and The Awakening

Kate Chopin wrote short stories and short novels rather than tomes, and set most of them in Creole culture. At Fault (1890), a novel about a young widow and the sexual constraints of women, foreshadows The Awakening (1899). Bayou Folk (1894), a collection of picutesque stories of Creole life on Louisiana plantation, was told with an exquisite eye to detail. It was the first of her works to gain national attention, and was followed by another collection of short stories, A Night in Acadie (1897). Her fiction was an outlet for her observations of late 19th-century Southern American society, especially, as mentioned above, the Creole and Cajun cultures she had lived with in Louisiana.

Her most mature and best-known work remains The Awakening. It was controversial in its time, garnering more negative reviews than positive, including one by her contemporary, Willa Cather, who offered up a rather harsh assessment.

The female characters in The Awakening didn’t adhere to the standards of what was acceptable behavior of the time. Edna Pontillier, the main character, has sexual urges and questions the sanctity of motherhood. Above all, there’s the theme of marital infidelity from the perspective of a wife. The book was widely banned, and even fell out of print for several decades before being rediscovered in the 1970s. It’s now considered a classic of feminist fiction. You can read the full text of The Awakening on this site.

Perhaps the poor reception of The Awakening discouraged Chopin, as her output slowed considerably after its publication. She published a few short stories, but wasn’t able to replicate the kind of early success she’d had in the early 1890s with her contributions to magazines and journals. Mostly, she lived on the inheritance she had received from her mother. All told, the period of prolific literary output didn’t last much more than a dozen or so years.

You might also like this 1899 review of The Awakening

A foremother of feminist literature

Chopin is admired as one of the foremothers of 20th century feminist literature. She may not have considered herself a feminist as such; she simply thought that women’s desires and ambitions were just as valid as men’s. As such, in her fiction, she focused on women’s constant struggles to forge an identity of their own, especially within the rigid constraints of Southern culture.

Though Chopin’s body of work is primarily fiction, her stories presented profound and very real observations. She allowed the range of human experience she viewed in everyday life to come through in her writing.

Kate Chopin died rather suddenly of a brain hemorrhage. She returned from a visit to the World’s Fair taking place in St. Louis on an August evening in 1904, complaining of severe pain in her head. She called one of her sons to come to her, but by the time he arrived, she was unconscious. Her other children rushed to her side, and though she briefly regained consciousness, she died the next day. She was 54 years old and was survived by all six of her children.

On Certain Bright, Brisk Days: Kate Chopin on her writing life

More about Kate Chopin on this site

Review by Willa Cather of The Awakening

The Awakening: An Analysis

On Certain Brisk, Bright Days

The Awakening (1899) – full text

Influential Quotes by Kate Chopin

Major Works

At Fault (1890)

Bayou Folk (1894)

A Night in Acadie (1897)

The Awakening (1899)

Lilacs and Other Stories

Biographies about Kate Chopin

Kate Chopin: A Critical Biography by Per Seyersted

Unveiling Kate Chopin by Emily Toth

Kate Chopin’s Private Papers Emily Toth and Per Seyersted

More Information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Chopin’s books on Goodreads

Read and Listen online

Chopin on Project Gutenberg

Audio recordings of Chopin’s works on Librivox

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Kate Chopin appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 7, 2018

Elizabeth Gaskell

Elizabeth Gaskell (née Elizabeth Cleghorn Stevenson, September 29, 1810 – November 12, 1865) was a British author known for short stories and novels focusing on social classes. In literary circles and beyond, she was often referred to simply as “Mrs. Gaskell.”

The upheaval of class boundaries, the industrialization of England, and women’s issues in the Victorian era were all themes of her work. So too was religion — her father and husband were both Unitarian ministers.

Elizabeth’s mother died a year or so after giving birth to her. Her father wasn’t able to care for her, so she was sent to live with an aunt. They lived in Cheshire, England, which years later would provide the inspiration for her novel, Cranford. Her aunt encouraged her to read classic books, which fed her love of writing. Her brother, who traveled widely, sent her books from near and far. Elizabeth grew up to be a young woman with a kind heart and gentle personality, and was also known for her beauty.

A match of hearts and minds

She married William Gaskell in 1832. Her husband was a minister of the Unitarian Church, and theirs proved to be a successful and companionable match. He became well known in his profession, and also somewhat esteemed for his literary work. Theirs was a sociable life, with Elizabeth gladly assuming the duties of hostess in her role as a minister’s wife.

Both Elizabeth and her husband were involved in social reform and seeking justice for the poor. “Sketches of the Poor, No. 1,” a series of poems she wrote with her husband, was published in January of 1837 in Blackwood’s Magazine.

A child dies, then a career is born

Her first novel, Mary Barton was written in a time of great grief following the 1844 death of her baby son at age one. More than a decade before, she had given birth to a stillborn girl. Mrs. Gaskell would go on to give birth to four daughters.

Up until that time, she hadn’t written anything of consequence other than the poems she collaborated on with her husband, as noted above, and these tragedies seemed to be the catalyst for her writing endeavors. She was also highly attuned to her experiences and surroundings. Living near Manchester in the early days of her marriage gave her a view of the rise of industrial society; and traveling with her husband to Germany and Belgium before their son was born gave rise to her interest in German literature.

After working on the book for three years, it was ready to be sent out to publishers, and like the Brontë sisters before her, Mrs. Gaskell found it difficult to get the attention of publishers. After languishing at Chapman & Hall for a year, she made an inquiry. The manuscript hadn’t been read at all, but once prompted, the publisher immediately accepted it and it was printed shortly thereafter. Mary Barton was published in 1848.

During the period in which she worked on Mary Barton, Mrs. Gaskell also wrote a small number of short stories, published pseudonymously.

Though Mary Barton was also published under an assumed name, it didn’t take long for the author’s true identity to be revealed. The novel was an immediate success, selling thousands of copies and setting the stage for a series of novels that were hugely admired and respected by critics and literary peers alike. One of her greatest admirers was Charles Dickens.

Some of her other well-known novels include Cranford (1851–53), Ruth (1853), North and South (1854–55), Sylvia’s Lovers (1863), and Wives and Daughters (1865).

During this period of great productivity, she also perfected the role of devoted wife and mother, endearing her to Victorian society — one which often frowned upon writing women. Friendly and charming, she was also cherished by friends and relatives.

You might also like: Quotes from Elizabeth Gaskell’s Novels

Life of Charlotte Brontë

After making a name for herself, she forged warm friendships with many well-known writers, including Charlotte Brontë and her sisters Emily and Anne. After Charlotte’s death, her father, Patrick Brontë asked Mrs.Gaskell to write her biography. Life of Charlotte Brontë was published in 1857, and helped secure the literary reputation of both author and subject.

By the time of Mrs. Gaskell’s own death in 1865, Life of Charlotte Brontë was still considered one of the best, most readable biographies in the English language, arguably comparable to the best of her novels.

Elizabeth Gaskell page on Amazon

Legacy

Despite the stellar reputation she had during her lifetime and shortly beyond, most of Mrs. Gaskell’s novels gradually fell out of favor and into obscurity. In the first half of the twentieth century, she was considered a minor writer of the feminine variety. She was unfairly criticized has lacking the “masculinity” to portray social problems.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Mrs. Gaskell’s work was re-evaluated and praised for its vision in presenting burgeoning industrial society and the social problems of the classes. North and South, for example, was a pioneering novel in its presentation of the conflicts between workers and their employers.

Mrs. Gaskell is now considered a master of Victorian literature, and is praised for her visionary use of storytelling to bring to life the rapid changes that she observed during her lifetime. In the words of the Elizabeth Gaskell Society:

“Despite her occasional tendency towards melodrama, Elizabeth had a natural gift for storytelling and Dickens referred to her as his ‘dear Scheherazade’. She originally published anonymously but, according to Victorian conventions, her readers came to know her as ‘Mrs Gaskell’ a name which made her sound matronly and safe.

Elizabeth Gaskell (as we prefer to call her) was actually courageous and progressive in her style and subject matter, and often framed her stories as critiques of Victorian attitudes (particularly those towards women). She braved the opprobrium of her husband’s Unitarian congregation, in part for her depiction of prostitution and illegitimacy, particularly in her novel Ruth, and also for her challenge to the traditional view of women’s role in society.”

Elizabeth Gaskell died in 1865, at age 65.

More about Elizabeth Gaskell on this site

Quotes from Elizabeth Gaskell’s Novels

Major Works

North and South

Cranford

Gothic Tales

Wives and Daughters: An Everyday Story

Life of Charlotte Brontë

Mary Barton

Ruth

Biographies about Elizabeth Gaskell

Elizabeth Gaskell: A Habit of Stories by Jenny Uglow

Elizabeth Gaskell: A Portrait in Letters by Chapple and Sharps

Elizabeth Gaskell: The Early Years by John Chapple

Elizabeth Gaskell: A Biography by Winifred Gerin

More Information

Wikipedia

The Gaskell Society

Reader discussion of Gaskell’s books on Goodreads

Read and listen online

Gaskell’s books on Project Gutenberg

Audio recordings of Gaskell’s works on Librivox

Visit and research

Elizabeth Gaskell’s Home , Manchester, England

Gaskell Manuscript & Letters Archive ,

University of Manchester, John Rylands University Library

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Elizabeth Gaskell appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 4, 2018

Sweet Lorraine — James Baldwin’s Tribute to Lorraine Hansberry

“Sweet Lorraine” is a love letter and tribute to Lorraine Hansberry by her friend and colleague, James Baldwin. It opens her posthumous book of collected writings, To Be Young, Gifted and Black (1969). Both were relatively young artists when they first met in the winter of 1958. Lorraine, then 28, came to the Actors’ Studio where the stage version of Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room was being workshopped. He was then 34.

Both were aware of one another’s work, and Lorraine would soon go on to defend her new friend Jimmy’s charge to introduce theater audiences to black and queer themes. Broadway producers, not surprisingly for the time, were uncomfortable with the content of Giovanni’s Room. As she would throughout her brief but blazingly brilliant career, Lorraine believed that the artist’s voice in whatever medium was to be as an agent for social change. The two bonded, for Lorraine was developing her own black, feminist, and queer politics.

“I loved her, she was my sister,” wrote Baldwin, “and my comrade … We had that respect of each other which perhaps is only felt by people on the same side of the barricades …” Alas, their friendship would be intense but short-lived, since Lorraine was to live just six years longer. She died of pancreatic cancer at age 34. Her reputation would already by sealed by the time of her death as the award-winning playwright of A Raisin in the Sun and, to a lesser degree, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window.

See also: To Be Young, Gifted and Black by Lorraine Hansberry

Here is a portion of James Baldwin’s “Sweet Lorraine, from the introductory pages of To Be Young, Gifted and Black (Prentice-Hall, © 1969):

An excerpt from “Sweet Lorraine” by James Baldwin

The first time I ever saw Lorraine was at the Actors’ Studio, in the winter of ’57-’58. She was there as an observer of the Workshop Production of Giovanni’s Room. She sat way up in the bleachers, taking on some of the biggest names in the American theatre because she had liked the play and they, in the main, hadn’t.

I was enormously grateful to her, she seemed to speak for me; and afterwards she talked to me with a gentleness and generosity never to be forgotten. A small, shy, determined person, with that strength dictated by absolutely impersonal ambitions: she was not trying to “make it” — she was trying to keep the faith.

We really met, however, in Philadelphia, in 1959, when A Raisin in the Sun was at the beginning of its amazing career. Much has been written about the play; I personally feel that it will demand a far less guilty and constricted people than the present-day Americans to be able to assess it at all; as an historical achievement, anyway, no one can gainsay its importance.

What is relevant here is that I had never in my life seen so many black people in the theater. And the reason was that before, in the entire history of the American theater, had so much of the truth of black people’s lives been seen on the stage. Black people ignored the theater because the theater had always ignored them.

But, in Raisin, black people recognized that house and all the people in it — the mother, the son, the daughter and the daughter-in-law, and supplied the play with an interpretive element which could not be present in the minds of white people: a kind of claustrophobic terror, created not only by their knowledge of the house but by their knowledge of the streets. And when the curtain came down, Lorraine and I found ourselves in the backstage alley, where she was immediately mobbed.

I produced a pen and Lorraine handed me her hardback and began signing autographs. “It only happens once,” she said. I stood there and watched. I watched the people, who loved Lorraine for what she had brought to them; and watched Lorraine, who loved the people for what they had brought to her. It was not, for her, a matter of being admired. She was being corroborated and confirmed. She was wise enough and honest enough to recognize that black American artists area very special case. One is not merely an artist and one is not judged merely as an artist: the black people crowding around Lorraine, whether or not they consider her an artist, assuredly consider her a witness …

Much of the strain under which Lorraine worked was produced by her knowledge of this reality, and her determined refusal to be destroyed by it She was a very young woman, with an overpowering vision, and fame had come to her early — she must certainly have wished, often enough, that fame had seen fit to drag its feet a little.

For fame and recognition are not synonymous, especially not here, and her fame caused her to be criticized very harshly, very loudly, and very often by both black and white people who were unable to believe, apparently, that a really serious intention could be contained in so glamorous a frame …

When so bright a light goes out so early, when so gifted an artist goes so soon, we are left with a sorrow and wonder which speculation cannot assuage. One is filled for a long time with a sense of injustice as futile as it is powerful … Sometimes, very briefly, one hears the exact inflection of the voice, the exact timbre of the laugh — as I have, when watching this dramatic presentation, To Be Young, Gifted and Black, and in reading through these pages. But I do not have the heart to presume to assess her work, for all of it, for me, was suffused with the light which was Lorraine.

It’s well worth reading not only the remainder of Balwin’s tribute,

but also the various writings of Lorraine Hansberry in To Be Young, Gifted and Black

To Be Young, Gifted and Black on Amazon

More about the friendship of Lorraine Hansberry and James Baldwin

Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood by Lynnée Denise Bonner

James Baldwin and Lorraine Hansberry: Two Revolutionaries, One Heart, One Mind

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Sweet Lorraine — James Baldwin’s Tribute to Lorraine Hansberry appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 2, 2018

Anna Sewell

Anna Sewell (March 30, 1820 – April 25, 1878) was a British novelist who had only one published book — Black Beauty — to her name. She was born in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk in England, into a family that was devoutly Quaker. Anna’s mother, Mary Wright Sewell (who outlived her daughter by a few years) was herself an author of poetry and children’s books. Her father was a shopkeeper and bank clerk whose unstable income created great hardship for the family.

Anna and her brother Phillip were mainly educated at home by their mother. The family’s precarious financial situation compelled the children to stay with their grandparents from time to time, and they moved around the country frequently.

Permanent injury

At age 12, Anna began going to school for the first time after the family moved to Stoke Newington. Two years later, she fell while walking home from school and broke both of her ankles. The treatment was shoddy, and she never fully recovered. For the rest of her life she was unable to stand or walk for very long, and endured a great deal of pain.

Anna’s declining health, in tandem with the family’s declining fortunes, compelled them to keep moving from place to place. In 1936, when she was 16, her father took a job in Brighton, hoping that its warmer climate would have a positive effect on her health. Anna followed her mother’s lead in leaving the Quaker community in favor of the Church of England.

Mary Sewall wrote a a series of children’s books with evangelical themes, and Anna helped edit them. She also worked with her mother on other social issues including abolition and temperance. Anna’s mother had long been a guiding force in her life. One of Mrs. Sewell’s books was Talks with Mamma, a collection of motherly advice she shared with Anna and her brother, Philip.

The family moved to Lancing in 1845. Anna’s health didn’t improve, so she travelled to Europe to continue to seek treatment. When she returned, she continued to follow her parents from one place to another, including Wick and Bath.

Quotes from Black Beauty by Anna Sewell

Black Beauty

Having become dependent on horse-drawn carriages to get around, Anna developed an empathy for horses. She grew to love them and cared deeply about their treatment, as well as that of all of animals. The inhumane treatment of horses she observed inspired her to write Black Beauty. She worked it between the years of 1871 and 1877, already in her fifties. By then she was in such poor health that she was hardly able to leave her bed. She had such difficulty writing that she was compelled to dictate it to her mother.

Anna hadn’t intended Black Beauty as a children’s book; rather, she wrote it for those who owned or worked with horses, “to induce kindness, sympathy, and an understanding treatment …” The story especially denounced the use of the bearing-rein and was warmly recommended by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Going beyond its original purpose, the book also conveyed practical insight into humane training practices for colts, stable management, and animal husbandry. A unique feature of the story is that it’s told from the horse’s perspective; it was originally subtitled The Autobiography of a Horse. It begins in a charming fashion:

The first place that I can well remember was a large pleasant meadow with a pond of clear water in it. Some shady trees leaned over it, and rushes and water-lilies grew at the deep end. Over the hedge on one side we looked into a plowed field, and on the other we looked over a gate at our master’s house, which stood by the roadside; at the top of the meadow was a grove of fir trees, and at the bottom a running brook overhung by a steep bank.

While I was young I lived upon my mother’s milk, as I could not eat grass. In the daytime I ran by her side, and at night I lay down close by her. When it was hot we used to stand by the pond in the shade of the trees, and when it was cold we had a nice warm shed near the grove.

Black Beauty is now considered a children’s classic, and as such, it long remained one of the top ten bestselling children’s books of all time. Millions of copies have been sold, and it has been translated into a multitude of languages.

The book was published when she was 57 years old, in 1877. In the last year of her life, she was completely bedridden and often in extreme pain. Anna Sewell died five months after the publication of Black Beauty, either of hepatitis or phthisis. She was able, at least, to see the warm reception of her only book in the first few months after publication in England.

Black Beauty in America

Black Beauty was published in America in 1890, and as it did in its native land, received much attention and laudatory reviews. At a time when horses were still very much depended on for transportation and labor, this deceptively simple tale served to create greater empathy for the beautiful animals. An August, 1890 article in an Indiana newspaper was typical in its praise:

“Since the recent publication of the work by Anna Sewall, entitled Black Beauty, attention has been called more and more to the cruelties practiced on the horse, man’s most faithful and useful servant. We require use of this animal more than of any other, and either from want of though or ignorance we forget that the horse is a very fine and delicate animal, sensitive as man to pain and hardships and almost human in its sense of hearing and understanding.

A horse lacks words with which to express its feelings, but who shall say it lacks a sense of man’s cruelty when he urges it beyond its utmost strength with blows and curses.”

Many other reviews, similarly, saw through a horse’s eyes and got under its skin, so to speak, for the first time. Another 1890 review in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle states that Anna’s first mention of writing the book was in a note to a friend in 1871, and that “her love of animals was so great that they seemed to understand her every word. When driving her father’s horses she guided them more by talking to them than by the use of the reins, addressed them by the Quaker ‘thou’ and ‘thee,’ just as she did in conversation with people.”

Anna Sewell in 1840, at about age 10

More about Anna Sewell on this site

Quotes from Black Beauty by Anna Sewell

Major Works

Black Beauty (1877)

Biographies

Dark Horse: A Life of Anna Sewell by Adrienne E. Gavin

Anna Sewell: The Woman Who Wrote Black Beauty by Susan Chitty

More Information

Anna Sewell on Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Black Beauty on Goodreads

Articles, News, Etc.

Black Beauty Author Anna Sewell Letters Discovered

Read and listen online

Black Beauty on Project Gutenberg

Audio of Black Beauty on Librivox

Visit

The Anna Sewell Birthplace and Childhood Home –

Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, England

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Anna Sewell appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 30, 2018

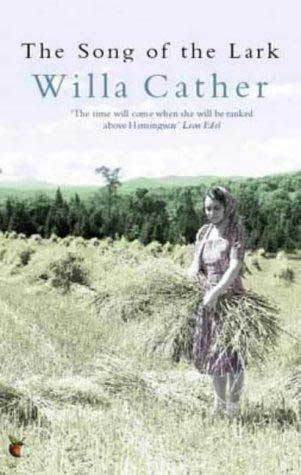

Willa Cather’s Inspiration for The Song of the Lark, Olive Fremstad

The Song of the Lark is a 1915 novel by Willa Cather, telling the story of Thea Kronborg and her desire to be a world-class singer. Born into the family of a Swedish Methodist minister in a Colorado village, she has a voice, an ambition, and a native sense of the true and fine — qualities all in contrast with the cheapness and tawdriness she perceives around her.

From her girlhood, when her ambition takes hold, to her triumph as a prima donna at thirty, Thea’s whole life is focused around her supreme desire for artistic perfection. Willa Cather had already outlined this novel, having had an interest in opera. Fortuitously, she crossed paths with the real-life opera singer Olive Fremstad during this time, which helped her make Thea Kronborg an even more vivid character. The following excerpt is from Willa: The Life of Willa Cather by Phyllis C. Robinson, © 1983:

Discovering Olive Fremstad

Sometime during the winter of 1913 a new enthusiasm entered Willa’s life. She had been assigned an article for McClure’s [magazine] on three American opera singers, Louise Homer, Geraldine Farrar, and Olive Fremstad. She enjoyed the interviews with Homer and Farrar but it was Fremstad who excited her imagination. To find a new kind of human creature, to get inside a new skin was like discovering a new country, only even more exhilarating.

Fremstad’s colleagues may have found the singer overbearing and difficult to get along with —she was famous for insisting on being paid in cash before each performance at the Metropolitan — but Willa declined to be put off by Fremstad’s temperament.

Olive Fremstad (1871 – 1951)

What she discerned in the dramatic soprano from Minnesota who had been born in Stockholm were the very qualities she had first seen in the fearless women she admired on the Divide. To Willa, Fremstad was like those pioneers, suspicious, defiant, far-seeing. Her physical presence alone might have been intimidating. Unpolished and untamed, she had a way of sweeping things before her, of dismissing people and objects that bored her.

The fierce concentration when she was working took all the energy she possessed and she had no interest in anything but music except when she was at her home in Maine. Then she cooked and gardened and chopped wood like the farm woman Willa always said she was.

Willa already had the outline of her next book in mind when she and Fremstad met. She had long planned to write about an opera singer and now she studied Fremstad, trying to discover what it was that transformed the stolid Swede into an artist. In her personal life Fremstad was intelligent but unimaginative … and yet she was a woman of supreme musical gifts, a brilliant Kundry, a magnificent Isolde, and an unforgettable Elizabeth. Willa and Edith Lewis went to the Metropolitan opera again and again to hear her sing.

Song of the Lark by Willa Cather on Amazon

A surprising performance

One performance in particular made a lasting impression on Willa. It was the day on which she went to interview Fremstad for the first time. Appearing at the appointment at four-thirty, she found the singer arriving late from a motor trip. Fremstad was exhausted, barely able to speak above a whisper, and so pale and wan she looked like an old woman.

Feeling sorry for the poor soul, Willa suggested it might be better to postpone the interview. Fremstad did not argue and Willa left the apartment, in time to join Edith and Isabelle McClung, who was visiting, at the opera for a performance of Tales of Hoffman. Before the second act began the manager came out with the announcement that the soprano had been taken ill but that Mme. Olive Fremstad had consented to sing in her place. Edith Lewis described the experience:

“The curtain went up — and there, before our astonished eyes, was Fremstad — whom Willa had left only an hour before — now a vision of dazzling youth and beauty. She sang that night in a voice so opulent, so effortless, that it seemed as if she were dreaming the music, not singing it. ‘But it’s impossible,’ Willa Cather kept saying. ‘It’s impossible.’”

Another time Willa saw Fremstad just after a performance as she was getting into her car. Willa was about to greet her but something stopped her and she merely bowed to Fremstad’s secretary. The singer’s eyes were empty glass, said Willa; she had simply spent her charge. Her personality renewed itself each night upon the stage, but the experience was draining, and when the curtain fell she could not sustain the illusion that she had created.

Willa was to use that strange duality of the creative artist which she observed in Fremstad in the heroine of The Song of the Lark, Thea Kronborg. (— Phyllis C. Robinson)

Olive Fremstad as Carmen

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Willa Cather’s Inspiration for The Song of the Lark, Olive Fremstad appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 26, 2018

Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn (December 14, 1640 –April 16, 1689) was a playwright, poet, and novelist known for being the first British woman to earn her living by her writing. She born in Wye, Kent, England. As a child, she was taken to Surinam (presumably by her parents), then an English possession.

While there, Aphra discovered the legend of the African prince Oroonoko and his beloved Imoinda. This later inspired what became her best-known novel, Oroonoko. She also has the distinction of being the first British woman to earn her living by her writing.

A return to England

Aphra returned to England some time between 1658 and 1664, having come of age. Shortly after her supposed return to England from Surinam, Behn may have married Johan (also written as Johann or John) Behn. Very little is known about him, other than that he was German or Dutch and possibly a merchant The marriage was brief, though it’s unknown whether it was due to widowhood or separation, but Aphra continued to use “Mrs Behn” as her professional name.

Aphra’s wit and charm somehow brought her into the court of Charles II, and the king sent her on secret service as a political spy in Antwerp during the second Anglo-Dutch war. She used the code name Astrea, which she later used as a nom de plume for some of her writings. Though she successfully accomplished the objects of her mission, legend had it that she was never paid for her spy services. Returning to England penniless, it’s often reported that she went to debtors’ prison, though this part of the story may or may not be true.

A prolific dramatist

Her history came into sharper focus and was verifiable by fact when she started her career as a writer. She’d had her fill of politics (though she continued to criticized the whigs). From the 1670s to the 1680s, she was one of the most prolific playwrights in Britain. It was from this time onward that she supported herself by her writings. Among her plays were The Forced Marriage, or the Jealous Bridegroom (1671); The Amorous Prince (1671); The Town Fop (1677); and The Rover, or the Banished Cavalier (in two parts, 1677 and 1681), The Debauchee, (1677), The Counterfeit Bridegroom, (1677), and The Roundheads (1682).

The Rover (1677) was arguably her most successful play, and remains one of her best known. King Charles II’s mistress, Nell Gwyn was a famous actress who came out of retirement to play the role of the whore, Angelica Bianca.

Behn was severely criticized by some for writing in a “coarse” or “masculine” style, which is to say that she included themes of sexual desire in her works. Occasionally, she wrote of love between women. Her work was considered risqué, even shocking and scandalous. On the other hand, she had many supporters and admirers of her work, including esteemed male authors of her time.

Aphra was immensely prolific, creating and staging nineteen plays, contributed to others, and became the first renowned female dramatist in Britain. Her dramas showed a thorough comprehension of stagecraft, and her wit always shone through.

One of Aphra’s last plays, Like Father, Like Son (1682) was such a flop that it wasn’t preserved in print, as were many of her other plays. The merging of the theatre companies for which she wrote made the writing of plays less profitable for her, and though she wrote a small number of plays after this one, she focused more on other forms of writing.

Aphra Behn page on Amazon

Poetry and prose

Though Aphra became renowned for her dramatic work, in her heart, she wished to be remembered as a poet. Like her plays, her poetry spoke of love, longing, and sexual themes. One of her best known is “The Disappointment,” a description of a sexual encounter from a woman’s perspective. The “disappointment” in the poem has often been interpreted as alluding to male impotence.

Aphra’s first collection of poetry, Poems Upon Several Occasions, was published in 1684. That same year, Love Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister was published, becoming an early example of the epistolary novel, that is, one told entirely in letters. These two 1864 books were quite successful, quickly going through several printings. Love Letters was spun into two sequels: Love Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister, Second Part (1685), and The Amours of Philander and Silvia (1687).

In 1688 Oroonoko was published. The story of a noble slave and his tragic love, as mentioned earlier, may have been based on legends Aphra heard during her youth in Surinam. Notably, it was the first English novel to express empathy for slaves. Like the works that came just before it, Oroonoko was quite successful, and was adapted for the stage in 1695 (though the author by then had been dead for several years). It continues to be her best known work.

Later years

Despite the success of her novels and poetry, Aphra Behn’s last years brought her ill health and debt. She had difficulty using her hands, but continued to write until the end, and was a celebrated literary figure.

She died on April 1689 at 48 years of age, and is buried in the East Cloister of Westminster Abbey. The inscription on her tombstone reads: “Here lies a Proof that Wit can never be Defence enough against Mortality.” She was quoted as stating that she had led a “life dedicated to pleasure and poetry.”

She is considered a highly influential dramatist of the Restoration era, and her prose work has been important to the development of English fiction that came after. She also did a substantial amount of work as a translator, mostly into French.

Aphra Behn not only broke new ground as a woman author who lived by her pen and didn’t limit the scope of her subject matter. She became a literary role model for many generations of women authors who came after her, and as such, inspired these lines by Virginia Woolf:

All women together ought to let flowers fall upon

the tomb of Aphra Behn, … for it was she who earned

them the right to speak their minds.

Major Works

Aphra Behn’s output was immense. This is a small selection of some of her best-known and preserved works.

The Forc’d Marriage (1670)

The Amorous Prince (1671)

The Dutch Lover (1673)

The Town Fop (1676)

The Rover, Part 1 (1677) and Part 2 (1681)

Sir Patient Fancy (1678)

The Feigned Courtesans (1679)

The Roundheads (1681)

The City Heiress (1682)

Like Father, Like Son (1682)

The Emperor of the Moon (1687)

Novels

The Fair Jilt

Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister

Oroonoko

Poetry collections

Poems upon Several Occasions, with A Voyage to the Island of Love (1684)

Lycidus; or, The Lover in Fashion (1688)

More information

Wikipedia

Biography of Aphra Behn on Luminarium

Poetry Foundation

Behn on Writers Inspire

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Biographies

Aphra Behn: A Secret Life by Janet Todd (2017)

Aphra Behn: The English Sappho by George Woodcock (1996)

Read and listen online

Aphra Behn’s works on Project Gutenberg

Audio versions on Librivox

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Aphra Behn appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 25, 2018

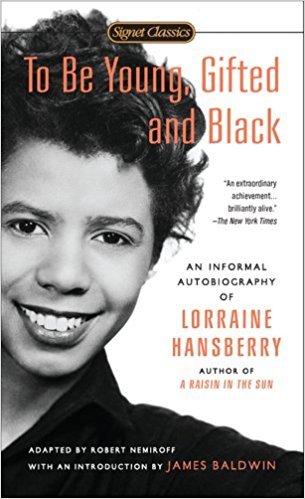

To Be Young, Gifted and Black by Lorraine Hansberry (1969)

To Be Young, Gifted and Black: Lorraine Hansberry in her Own Words is a 1969 collection of autobiographical writings by the playwright and author best known for A Raisin in the Sun. It was the first play to be written by an African-American woman to be staged on Broadway.

Lorraine Hansberry‘s ex-husband and friend, the songwriter and poet Robert Nemiroff, became her literary executor after her death in 1965. He gathered her unpublished writings and first adapted them into a stage play of the same name, which ran off Broadway from 1968 to 1969. The acclaimed play was one of the most successful of that season. It continues to be performed around the world.

In 1969, the collection of autobiographical writings by Hansberry that formed the basis of the play — letters, journals, and interviews — were gathered and published as a book of the same title. It takes the reader from Hansberry’s early life in a Chicago ghetto, though her college days, and beyond into the creation of A Raisin in the Sun, which she wrote while still in her twenties. It also touches on her marriage, her commitment to race and gender issues, and ends with her battle with terminal cancer. When she died, she was only thirty-four.

This 1969 review of To Be Young, Gifted and Black presents a typically laudatory view of not only the book, but of the talented woman behind the words.

To Be Young, Gifted and Black

Original review by Gordon Young of To Be Young, Gifted and Black: Lorraine Hansberry in Her Own Words, adapted by Robert Nemiroff (Fresno Bee, December 28, 1969): Lorraine Hansberry is best known for her play, A Raisin in the Sun, about a Southside Chicago black family’s decision to move to a white suburb.

The play opened on Broadway in 1959 to critical acclaim and later was made into an award-winning movie starring Sidney Poitier. A second play, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, closed in 1965 on the day that Miss Hansberry died of cancer at age thirty-four.

A life cut short, a body of work unfulfilled

At the time of her death, Miss Hansberry was working on other dramas and had left behind a sizable body of reviews, letters, and speeches which form the basis of this book. Among her manuscripts was a play titled Les Blancs [produced on Broadway in 1970]. A second forthcoming volume will contain three shorter plays.

In addition, this book is an expansion of the script of a play by the same title which was staged in New York shortly before its publication and enjoyed a successful run. Clearly, Lorraine Hansberry deserves recognition for more than A Raisin in the Sun.

Robert Nemiroff’s role

The task of marshaling that recognition has been taken up by her husband and literary executor, Robert Nemiroff, who adapted the material in this book. In the foreword he explains that he came across this undated note among her papers:

“If anything should happen — before ’tis done — may I trust that all commas and periods will be placed and someone will complete my thoughts.”

Nemiroff has placed the commas and periods with skill and taste. What emerges is a portrait of the artist as a young woman starting with a middle-class childhood in Chicago through two years at the University of Wisconsin and then on to Greenwich Village where, after the success of “Raisin,” and before her death, Miss Hansberry worked on her other writing and became increasingly associated with the civil rights movement of the early 1960s.

To Be Young, Gifted and Black on Amazon

An advocate for her race

She was an eloquent spokesperson for her race. She didn’t attempt to disassociate herself from being black. A well-meaning critic once described her as “a writer who happens to be a Negro.” But Miss Hansberry scoffed at such comments since the characters in her plays reflected the crucial dilemma of being both inescapably black while striving to attempt full status as human beings.

She was convinced that slavery had so eroded the dignity of African-American that no amount of white, liberal patronizing would ever effect a lasting improvement until black people achieved their own renaissance. Some of her more ideological essays and reviews are prophetic of what has developed as a separatist, militant movement.

The universality of Hansberry’s writing

Nevertheless, there remains a universality about much of her writing. There was no existential revelation that life contains the seeds of tragedy — she had known that all along.

On the other hand, her writing does not dips the cynicism and hopelessness so common in theater of her time. There is anger in her plays, but it is justified, specifically human, and directed not at hating but at affirming the ties that bind. Her style is compassionate, restrained, and finely honed, which makes it ever more impactful.

Early in her career, Miss Hansberry summarized her credo: “I wish to live because life has within it that which is good, that which is beautiful, and that which is love. Therefore, sine I have known all these things I have found them reason enough — and I wish to live.”

In the summer of 1964, Miss Hansberry wrote in her journal, “I think when I get my health back I shall go into the South to find out what kind of revolutionary I am.”

She never did, of course, but this book and her plays will make readers want to test the depth of their own commitment to the principles of humanism and understanding of which Lorraine Hansberry was such a brief but brilliant example.

You might also like: Quotes by Lorraine Hansberry

More about To Be Young, Gifted and Black by Lorraine Hansberry

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Wikipedia (play)

Reader’s Guide at Random House

To Be Young, Gifted and Black (1972 made-for-TV film)

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post To Be Young, Gifted and Black by Lorraine Hansberry (1969) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 23, 2018

Renascence by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1912)

“Renascence” by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892 – 1950) is the 1912 poem that put this iconic American poet on the literary map. Though it was published when she was just nineteen, it held up as one of the best poems in her canon. You can find an excellent analysis of it on Poetry Foundation.

The 214-line lyric poem consists of rhymed couplets. The overarching theme is the connection of the individual to nature. The narrator of the poem is writing from a mountaintop from which she observes the broad vista. Observation turn into a mystical experience. The poem was written on the summit of Mt. Battle in Camden, Maine, which now has a plaque in the spot that inspired it.

The poem considers human suffering and death, and after a refreshing rain, the narrator is once again able to experience joy, the rebirth of life — thus the title, “Renascence.”

The backstory of the poem’s publication sets the stage for what would be an eventful and dramatic life. Edna has already been writing — and even publishing — poetry while in her teens. Her mother encouraged her to enter the poem in a contest sponsored by The Lyric Year, an annual volume of poetry. It was accepted and included in the collection.

You might also like: Quotes by Edna St. Vincent Millay

“Renascence” was considered the finest poem in the collection, but ultimately won only fourth place. This resulted in quite a bit of controversy. Even the first and second prize winners felt that Edna’s poem should have won; the runner-up even offered Edna his prize money. The attendant publicity did serve to bring Edna quite a bit of publicity, bringing her and her work to the attention of editors and publishers.

After the publication of The Lyric Year, Edna was reading this poem and playing piano at Whitehall Inn in Camden Maine. One of the audience members was Caroline B. Dow, a wealthy arts patron who offered to fund her education at Vassar College.

Renascence

All I could see from where I stood

Was three long mountains and a wood;

I turned and looked another way,

And saw three islands in a bay.

So with my eyes I traced the line

Of the horizon, thin and fine,

Straight around till I was come

Back to where I’d started from;

And all I saw from where I stood

Was three long mountains and a wood.

Over these things I could not see;

These were the things that bounded me;

And I could touch them with my hand,

Almost, I thought, from where I stand.

And all at once things seemed so small

My breath came short, and scarce at all.

But, sure, the sky is big, I said;

Miles and miles above my head;

So here upon my back I’ll lie

And look my fill into the sky.

And so I looked, and, after all,

The sky was not so very tall.

The sky, I said, must somewhere stop,

And—sure enough!—I see the top!

The sky, I thought, is not so grand;

I ‘most could touch it with my hand!

And reaching up my hand to try,

I screamed to feel it touch the sky.

I screamed, and—lo!—Infinity

Came down and settled over me;

Forced back my scream into my chest,

Bent back my arm upon my breast,

And, pressing of the Undefined

The definition on my mind,

Held up before my eyes a glass

Through which my shrinking sight did pass

Until it seemed I must behold

Immensity made manifold;

Whispered to me a word whose sound

Deafened the air for worlds around,

And brought unmuffled to my ears

The gossiping of friendly spheres,

The creaking of the tented sky,

The ticking of Eternity.

I saw and heard, and knew at last

The How and Why of all things, past,

And present, and forevermore.

The Universe, cleft to the core,

Lay open to my probing sense

That, sick’ning, I would fain pluck thence

But could not,—nay! But needs must suck

At the great wound, and could not pluck

My lips away till I had drawn

All venom out.—Ah, fearful pawn!

For my omniscience paid I toll

In infinite remorse of soul.

All sin was of my sinning, all

Atoning mine, and mine the gall

Of all regret. Mine was the weight

Of every brooded wrong, the hate

That stood behind each envious thrust,

Mine every greed, mine every lust.

And all the while for every grief,

Each suffering, I craved relief

With individual desire,—

Craved all in vain! And felt fierce fire

About a thousand people crawl;

Perished with each,—then mourned for all!

A man was starving in Capri;

He moved his eyes and looked at me;

I felt his gaze, I heard his moan,

And knew his hunger as my own.

I saw at sea a great fog bank

Between two ships that struck and sank;

A thousand screams the heavens smote;

And every scream tore through my throat.

No hurt I did not feel, no death

That was not mine; mine each last breath

That, crying, met an answering cry

From the compassion that was I.

All suffering mine, and mine its rod;

Mine, pity like the pity of God.

Ah, awful weight! Infinity

Pressed down upon the finite Me!

My anguished spirit, like a bird,

Beating against my lips I heard;

Yet lay the weight so close about

There was no room for it without.

And so beneath the weight lay I

And suffered death, but could not die.

Long had I lain thus, craving death,

When quietly the earth beneath

Gave way, and inch by inch, so great

At last had grown the crushing weight,

Into the earth I sank till I

Full six feet under ground did lie,

And sank no more,—there is no weight

Can follow here, however great.

From off my breast I felt it roll,

And as it went my tortured soul

Burst forth and fled in such a gust

That all about me swirled the dust.

Deep in the earth I rested now;

Cool is its hand upon the brow

And soft its breast beneath the head

Of one who is so gladly dead.

And all at once, and over all

The pitying rain began to fall;

I lay and heard each pattering hoof

Upon my lowly, thatched roof,

And seemed to love the sound far more

Than ever I had done before.

For rain it hath a friendly sound

To one who’s six feet underground;

And scarce the friendly voice or face:

A grave is such a quiet place.

The rain, I said, is kind to come

And speak to me in my new home.

I would I were alive again

To kiss the fingers of the rain,

To drink into my eyes the shine

Of every slanting silver line,

To catch the freshened, fragrant breeze

From drenched and dripping apple-trees.

For soon the shower will be done,

And then the broad face of the sun

Will laugh above the rain-soaked earth

Until the world with answering mirth

Shakes joyously, and each round drop

Rolls, twinkling, from its grass-blade top.

How can I bear it; buried here,

While overhead the sky grows clear

And blue again after the storm?

O, multi-colored, multiform,

Beloved beauty over me,

That I shall never, never see

Again! Spring-silver, autumn-gold,

That I shall never more behold!

Sleeping your myriad magics through,

Close-sepulchred away from you!

O God, I cried, give me new birth,

And put me back upon the earth!

Upset each cloud’s gigantic gourd

And let the heavy rain, down-poured

In one big torrent, set me free,

Washing my grave away from me!

I ceased; and through the breathless hush

That answered me, the far-off rush

Of herald wings came whispering

Like music down the vibrant string

Of my ascending prayer, and—crash!

Before the wild wind’s whistling lash

The startled storm-clouds reared on high

And plunged in terror down the sky,

And the big rain in one black wave

Fell from the sky and struck my grave.

I know not how such things can be;

I only know there came to me

A fragrance such as never clings

To aught save happy living things;

A sound as of some joyous elf

Singing sweet songs to please himself,

And, through and over everything,

A sense of glad awakening.

The grass, a-tiptoe at my ear,

Whispering to me I could hear;

I felt the rain’s cool finger-tips

Brushed tenderly across my lips,

Laid gently on my sealed sight,

And all at once the heavy night

Fell from my eyes and I could see,—

A drenched and dripping apple-tree,

A last long line of silver rain,

A sky grown clear and blue again.

And as I looked a quickening gust

Of wind blew up to me and thrust

Into my face a miracle

Of orchard-breath, and with the smell,—

I know not how such things can be!—

I breathed my soul back into me.

Ah! Up then from the ground sprang I

And hailed the earth with such a cry

As is not heard save from a man

Who has been dead, and lives again.

About the trees my arms I wound;

Like one gone mad I hugged the ground;

I raised my quivering arms on high;

I laughed and laughed into the sky,

Till at my throat a strangling sob

Caught fiercely, and a great heart-throb

Sent instant tears into my eyes;

O God, I cried, no dark disguise

Can e’er hereafter hide from me

Thy radiant identity!

Thou canst not move across the grass

But my quick eyes will see Thee pass,

Nor speak, however silently,

But my hushed voice will answer Thee.

I know the path that tells Thy way

Through the cool eve of every day;

God, I can push the grass apart

And lay my finger on Thy heart!

The world stands out on either side

No wider than the heart is wide;

Above the world is stretched the sky,—

No higher than the soul is high.

The heart can push the sea and land

Farther away on either hand;

The soul can split the sky in two,

And let the face of God shine through.

But East and West will pinch the heart

That can not keep them pushed apart;

And he whose soul is flat—the sky

Will cave in on him by and by.

The post Renascence by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1912) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.