Nava Atlas's Blog, page 68

May 3, 2019

Gloria E. Anzaldúa

Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa (September 26, 1942 – May 15, 2004) was a queer Chicana poet, feminist theorist, and writer. Her writing and poetry discuss the anger that stems from social and cultural marginalization. She herself experienced this growing up in the Mexican-Texas border as the daughter of a Spanish American and Native American.

Anzaldúa was born in Jesús María Ranch in Rio Grande Valley of South Texas as the oldest of four siblings. Throughout her childhood, her parents, Urbano Anzaldúa and Amalia Anzaldúa García, moved their family to various ranches working as migrant farmers.

Anzaldúa worked in the fields and became aware of the Southwest and South Texas landscapes along with the existence of Spanish speakers on the margins in the United States. As a result, she began to gain awareness of social justice issues and started writing about them. After several years of working on ranches, her parents decided to relocate their family to Hargill, Texas.

Education and Teaching Career

Anzaldúa received a B.A. in English, Art, and Secondary Education from the University of Texas-Pan American (now University of Texas Rio Grande Valley) in 1968. Soon after in 1972, she received an M.A. in English and Education from the University of Texas at Austin. During her time in Austin, she joined politically active cultural poets and radical dramatists, such as Ricardo Sanchez and Hedwig Gorski.

After receiving her Bachelor’s in English, she started a job as a preschool and special education teacher. Around this time in the 1970s, she also taught a course at UT-Austin called “La Mujer Chicana”, which she described as a turning point for her as she felt more connected to the queer community, writing, and feminism.

She later enrolled in the University of Texas’ doctoral program for comparative literature but left the program. Soon after, she moved to California in 1977, where she supported herself as an independent scholar.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The Chicana FeministIn California, Anzaldúa devoted herself completely to her writing. During this time, she was supporting herself through her writing, lectures, occasionally teaching sessions about feminism, Chicano studies, creative writing at San Francisco State University, the University of California, Santa Cruz, and more.

She continued taking part in political activism and consciousness-raising keeping in mind her main goal–to find ways to build a multicultural, inclusive feminist movement. To her dismay, she found that there were few writings by or about women of color.

The Prolific 1980sAnzaldúa continued writing, teaching, and traveling to speaking events throughout the 1980s. During this time, she co-edited This Bridge Called My Back: Writing by Radical Women of Color with Cherrie Moraga, which was published in 1981 and won the Before Columbus Foundation American Book Award.

In addition, she wrote the semi-autobiographical Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza which was published in 1987. Making Face Making Soul/Haciendo Caras: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Women of Color was published in 1990 and included writings by famous feminists, such as Audre Lorde. The book includes titles such as “Still Trembles Our Rage in the Face of Racism” and “(De)Colonized Slaves”.

Themes of Anzaldúa’s worksAnzaldúa’s writing included the theme of Nepantla, meaning “in the middle” to describe her experience as a Chicana woman. From this, she created the term “Nepantlera,” meaning a threshold of people that move among multiple conflicting worlds as they refuse to align themselves exclusively with any single individual, group, or belief system.

Spirituality was another common theme as she occasionally described herself as a very spiritual person and stated that she had experienced four out-of-body experienced in her lifetime. She referred to her devotion to la Virgen de Guadalupe and developed concepts of spiritual activism.

Sexuality and feminism are very prominent themes in her writing. She expressed that she possessed a multi-sexuality and even stated that she felt an “intense sexuality” towards her father, animals, and trees. Though she identifies as a lesbian in her writing, she had relationships with both men and women. She also identified as a feminist and some of her major works are associated with Chicana feminism and postcolonial feminism.

Anzaldúa’s writing brings English and Spanish together as a united language, stemming from her theory of “borderlands” identity. Her work emphasizes the connection between language and identity and expresses concern with those who give up on their native language in order to fit in with society.

. . . . . . . . . .

Gloria E. Anzaldúa page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . .

In 1986, she won the Before Columbus Foundation American Book Award for This Bridge Called My Back: Writing by Radical Women of Color.

In 1987, her work Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza was named one of the 38 best books of 1987 by Library Journal and 100 Best Books of the Century by Hungry Mind Review and Utne Reader.

In 1991, Anzaldúa won the Lambda Lesbian Small Book Press Award for Making Face Making Soul/Haciendo Caras: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Women of Color. This year, she was also awarded the Lesbian Rights Award.

In 2012, she was named by Equality Forum as one of their 31 Icons of the LGBT History Month. In 2016, she won the Independent Publisher Book Award for Anthologies in 2016 for This Bridge Called My Back: Writing by Radical Women of Color.

LegacyAround the time of her death, Anzaldúa was very close to completing her book manuscript, Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality, and was planning on submitting it as her dissertation. Unfortunately, she passed away in 2004 in Santa Cruz, California due to complications from diabetes and was unable to complete it. Duke University Press posthumously published it in 2015.

Today, many institutions offer awards in the name of Gloria E. Anzaldúa, such as The Gloria E. Anzaldúa Prize awarded annually and the Gloria E. Anzaldúa Book Prize given by the National Women’s Studies Association.

. . . . . . . . . .

Major works

This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color – 1981Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza – 1987Making Face, Making Soul/Haciendo Caras: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Feminists of Color – 1990Interviews/Entrevistas – 2000This Bridge We Call Home: Radical Visions for Transformation – 2002The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader – 2009Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality – 2015Biographies

Northamerican Silences: History, Identity, and Witness in the Poetry of Gloria Anzaldúa, Cherríe Moraga, and Leslie Marmon Silko by Kate Adams (1994)Gloria Anzaldúa’s Queer Mestizaje by Ian Barnard (1997)More Information

Wikipedia The Poetry Foundation ThoughtCo The Gloria E. Anzaldúa FoundationSkyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Gloria E. Anzaldúa appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 2, 2019

Quotes from A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry

Lorraine Hansberry (1930 – 1965) was an American playwright and author. Her best-known work, A Raisin in the Sun(1959), was the first play by an African-American woman to be staged on Broadway. And at the young age of 29, Hansberry became the youngest American and the first African-American playwright to win the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award for Best Play.

The play details the life of the Youngers, an African-American family living on the South Side of Chicago in the 1950s. It follows their struggles, their commitment to family, and their desire to overcome poverty while remaining a family unit. Here are quotes from Hansberry’s most famous work, A Raisin in the Sun:

. . . . . . . . . .

“Once upon a time freedom used to be life—now it’s money.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I wonder if the quiet was not better than … death and hatred. But … I will not wonder long.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Man say to his woman: I got me a dream. His woman say: Eat your eggs.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Just tell me, what it is you want to be—and you’ll be it. . . . Whatever you want to be—Yessir! You just name it, son . . . and I hand you the world!”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Then isn’t there something wrong in a house—in a world—where all dreams, good or bad, must depend on the death of a man?”

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: To Be Young, Gifted and Black by Lorraine Hansberry

. . . . . . . . . .

“There is always something left to love. And if you ain’t learned that, you ain’t learned nothing.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Son – I come from five generations of people who was slaves and sharecroppers – but ain’t nobody in my family never let nobody pay ‘em no money that was a way of telling us we wasn’t fit to walk the earth. We ain’t never been that poor. We ain’t never been that – dead inside.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Yes – I taught you that. Me and your daddy. But I thought I taught you something else too… I thought I taught you to love him.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“See there, that just goes to show you what women understand about the world. Baby, don’t nothing happen for you in this world ‘less you pay somebody off!”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I guess that’s how come that man finally worked hisself to death like he done. Like he was fighting his own war with this here world that took his baby from him.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Sometimes it’s like I can see the future stretched out in front of me – just plain as day. The future, Mama. Hanging over there at the edge of my days. Just waiting for me – a big, looming blank space – full of nothing. Just waiting for me. But it don’t have to be.”

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy: Quotes by Lorraine Hansberry

. . . . . . . . . .

“And where does it end?… An end to misery! To stupidity! Don’t you see there isn’t any real progress, Asagai, there is only one large circle that we march in, around and around, each of us with our own little picture in front of us – our own little mirage that we think is the future.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Asagai, while I was sleeping in that bed in there, people went out and took the future right out of my hands! And nobody asked me, nobody consulted me – they just went out and changed my life! “

. . . . . . . . . .

“You making something inside me cry, son. Some awful pain inside me.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Well – we are dead now. All the talk about dreams and sunlight that goes on in this house. It’s all dead now.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Child, when do you think is the time to love somebody the most? When they done good and made things easy for everybody? Well then, you ain’t through learning – because that ain’t the time at all. It’s when he’s at his lowest and can’t believe in hisself ‘cause the world done whipped him so! When you starts measuring somebody, measure him right, child, measure him right. Make sure you done taken into account what hills and valleys he come through before he got to wherever he is.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I guess I always think things have more emphasis if they are big, somehow.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Lorraine Hansberry page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

“What’s the matter with you all! I didn’t make this world! It was give to me this way! Hell, yes, I want me some yachts someday! Yes, I want to hang some real pearls ‘round my wife’s neck. Ain’t she supposed to wear no pearls? Somebody tell me – tell me, who decides which women is suppose to wear pearls in this world. I tell you I am a man – and I think my wife should wear some pearls in this world!”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It’s dangerous, son…When a man goes outside his home to look for peace.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“That is just what is wrong with the colored woman in this world…Don’t understand about building their men up and making ‘em feel like they somebody. Like they can do something. “

. . . . . . . . . .

“Who the hell told you you had to be a doctor? If you so crazy ‘bout messing ‘round with sick people – then go be a nurse like other women – or just get married and be quiet…”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It’s just that every American girl I have known has said that to me. White – black – in this you are all the same. And the same speech, too!…It’s how you can be sure that the world’s most liberated women are not liberated at all. You all talk about it too much!”

. . . . . . . . . .

“When the world gets ugly enough – a woman will do anything for her family. “

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“It ain’t much, but it’s all I got in the world and I’m putting it in your hands. I’m telling you to be the head of this family from now on like you supposed to be.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Larrisa Pope is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in International Business and Public Relations. She is passionate about keeping the legacies of iconic female authors alive.

. . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Quotes from My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier

My Cousin Rachel is a novel by British author Daphne du Maurier (1907 – 1989), first published in the U.K. in 1951 and in the U.S. in 1952. Echoing du Maurier’s 1938 masterwork Rebecca, My Cousin Rachel is a romantic thriller. It’s set primarily on a large estate in Cornwall, England, where du Maurier drew real-life inspiration. She saw a portrait of a woman named Rachel Carew at an estate, and the creative spark was lit. Read on for quotes from My Cousin Rachel, which will give you the flavor of this iconic novel.

Multiple television and film adaptations of this novel have been produced. My Cousin Rachel was adapted into a 1983 BBC miniseries, and as a 2011 radio play, also by the BBC. Most recently, a film adaptation was released in 2017 starring the aptly named Rachel Weisz in the title role.

The story is told by Phillip Kendall, a conscience-stricken, unhappy young man As seen through his eyes, the novel is a mystery to the very end.

Is Rachel Ashley is guilty of the murder of her elderly English husband in her Florentine villa, and is she equally guilty of an attempt to poison his young cousin and heir in the old family home in Cornwall? Rachel, like du Maurier’s iconic Rebecca character, remains a puzzle to the end. Is Rachel a devil or an angel? It’s up to the reader to decide.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier

. . . . . . . . . .

“Truth was something intangible, unseen, which sometimes we stumbled upon and did not recognize, but was found, and held, and understood only by old people near their death, or sometimes by the very pure, the very young.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“He was like someone sleeping who woke suddenly and found the world…all the beauty of it, and the sadness too. The hunger and the thirst. Everything he had never thought about or known was there before him, and magnified into one person who by chance, or fate — call it what you will — happened to be me.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She had contemplated life so long it had become indifferent to her.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“People who mattered could not take the humdrum world. But this was not the world, it was enchantment; and all of it was mine.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I wondered how it could be that two people who had loved could yet have such a misconception of each other and, with a common grief, grow far apart. There must be something in the nature of love between a man and a woman that drove them to torment and suspicion.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“… A lonely man is an unnatural man, and soon comes to perplexity. From perplexity to fantasy. From fantasy to madness.”

. . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy Quotes from Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

. . . . . . . . . .

“… I believe there is nothing so self-destroying, and no emotion quite so despicable, as jealousy.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If we killed women for their tongues all men would be murderers.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A man’s jealousy is like a child’s, fitful and foolish, without depth. A woman’s jealousy is adult, which is very different.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A woman of feeling does not easily give way. You may call it pride, or tenacity, call it what you will. In spite of all the evidence to the contrary, their emotions are more primitive than ours. They hold to the thing they want, and never surrender.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“We were dreamers, both of us, unpractical, reserved, full of great theories never put to test, and like all dreamers, asleep to the waking world.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There is no going back in life, no return, no second chance. I cannot call back the spoken word or the accomplished deed.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“There are some women … good women very possibly, who through no fault of their own impel disaster. Whatever they touch, somehow turns to tragedy.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“How soft and gentle her name sounds when I whisper it. It lingers on the tongue, insidious and slow, almost like poison, which is apt indeed. It passes from the tongue to the parched lips, and from the lips back to the heart. And the heart controls the body, and the mind also. Shall I be free of it one day?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I love the stillness of a room after a party. The chairs are moved, the cushions disarranged, everything is there to show that people enjoyed themselves; and one comes back to the empty room happy that it’s over, happy to relax and say, ‘Now we are alone again.’ Ambrose used to say to me in Florence that it was worth the tedium of visitors to experience the pleasure of their going. He was so right.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The point is, life has to be endured, and lived. But how to live it is the problem.”

. . . . . . . . . .

My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 1, 2019

A House with Four Rooms by Rumer Godden (1989)

A House with Four Rooms (1989) is the second part of a two-part autobiography by Rumer Godden (1907 – 1998). A noted and prolific novelist and memoirist born in Eastbourne, Sussex (England), her early years and youth were spent in India at the height of British colonial rule. Though her life was not without its share of struggles, it was often as dramatic and colorful as the stories she so skillfully created.

Interestingly, she based the title — A House With Four Rooms —on an Indian proverb, which says: “Everyone is a house with four rooms, a physical, a mental, an emotional and a spiritual. Most of us tend to live in one room most of the time but, unless we go into every room, every day, even if only to keep it aired, we are not a complete person.”

While the first part of Rumer’s autobiography, A Time to Dance, No Time to Weep (1987), is more absorbing and speaks of her years in India, this one should also appeal to the author’s fans, as it provides insights into the mind of a brilliant writer, who seems to appeal to generations, beyond her time.

The book starts with Rumer’s permanent return to England, forced upon her by an unfortunate incident in India. Also on the verge of a divorce, with two little girls to take care of, this book is all about the rebuilding of Godden’s life, most importantly her writing one.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: A Time to Dance, No Time to Weep

. . . . . . . . . .

Rumer touches upon the caste system of India in those days, which resulted in the bifurcation of work done by domestic help and her learning to depend on them, from her childhood years. She is frank enough to admit to her lack of skills in the housekeeping department and quickly evolves a convenient philosophy, “Never do anything that someone else around you can do better than you can.”

Thus she resolves to stick to whatever she has a gift for — “teaching children perhaps, and amusing them; bringing up Pekingese, and writing.” But conscious of her own shortcomings, she does make sure that her daughters get the training, not to be found wanting in domestic skills.

A substantial portion of this book covers her adventures with her various publishers and agents including Spencer Curtis Brown, who after reading her manuscript, The River tells her, “You need have no doubts that Robert Lusty will publish this. I particularly like the names of the four frog children,” which gives Rumer an idea of Spencer’s thorough perusal of her manuscript.

The River and working with Jean Renoir

How The River attracts the attention of Jean Renoir, “simply one of the finest film directors in the world,” in the words of Spencer, makes for an absorbing part of this autobiography. Like his other contemporaries, Renoir had also made the shift to Hollywood from Europe, and felt that Hollywood would expect him to make films similar to what he was doing earlier.

In Renoir’s words, “I had to find a new style which would fit with the new person I had become and with the new life I had found. The day I read Rumer Godden’s novel, The River, I knew I had found it.”

Thus begins a new life for Rumer, as she is persuaded to write the script for the film, and is again catapulted into another life that includes a stay in India for the casting and shooting of the film.

. . . . . . . . . .

A House with Four Rooms on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

Savoring successIn her autobiography, Rumer speaks unabashedly about her stepping foot into the life of luxury that only the very well-known writers can dream of. She writes:

“With Macmillan as my publisher, I seemed to enter into a new dimension. Eventually it was not only lunches at Boulestin’s, and its like or in the boardroom, it was dinner in private houses or at the Garrick, of having cars sent for me, or escorts to publicity interviews, radio and television…” and so on.

This book has mention of the many houses that Rumer opts to live in and do up, as she has a great fondness for bric-a-brac and a desire to make any house “into a home.” There are also details about travails with the different kinds of domestic help, and in deciding on the right kind of schools for her daughters, Jane and Paula.

A new husband and a spiritual search

The book heralds the arrival of James Haynes-Dixon, who worms his way into Rumer’s life and heart, finally winding up as her second husband. From her descriptions, he is clearly the opposite of what her first husband has been and seems to be the man for all seasons for Rumer and her two girls.

Rumer also speaks of her inner spiritual search, which she discovers in the religion that she was born into, Christianity.

Interspersed with black and white pictures of the author, with family and friends, the book does provide delightful glimpses of all the four rooms that Rumer Godden occupied. One can’t help wondering though, whether there was a fifth one that she held back from her readers.

. . . . . . . . .

Melanie P. Kumar is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Rumer Godden

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post A House with Four Rooms by Rumer Godden (1989) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 30, 2019

The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson (1959)

The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson is a 1959 novel in the gothic horror genre, though it might be more accurately described as a literary ghost story. A finalist for the National Book Award, it’s a masterful story of psychological terror.

Hill House is a mansion built by Hugh Crain, who has been long passed away. Dr. John Montague, an investigator of the supernatural, wishes to conduct a study there to find existence of spirits. With him are three young companions including the young heir to the mysterious house, and two young women.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like: We Have Always Lived in the Castle

. . . . . . . . . .

In the 2006 Penguin re-issue edition of The Haunting of Hill House, Laura Miller provides detailed insight on the novel and its complicated, often troubled author. I highly recommend linking through to Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House: An Introduction for fascinating insights, not only on this particular work, but the genre. Here’s an excerpt:

The true antecedents of The Haunting of Hill House are not the traditional English ghost stories of M.R. James or Sheridan LeFanu, or even the gothic fiction of Edgar Allan Poe, but the ghostly tales of Henry James. The Turn of the Screw, another short novel about a lonely, imaginative young woman in a big isolated house, is a probable influence, and so, perhaps, is “The Jolly Corner,” the story of a middle-aged aesthete who roams the empty rooms of his childhood home, haunted by the specter of the man he would have been if he had lived his life differently.

The ghost story is a small genre to begin with, but its subgenre, the psychological ghost story, the category to which The Haunting of Hill House and Henry James’ tales belong, is tinier still. The literary effect we call horror turns on the dissolution of boundaries, between the living and the dead, of course, but also, at the crudest level, between the outside of the body and everything that ought to stay inside. In the psychological ghost story, the dissolving boundary is the one between the mind and the exterior world.

During the third major manifestation at Hill House, as Eleanor’s resistance begins to buckle, she thinks, “how can these others hear the noise when it is coming from inside my head?”

The psychological ghost story is as much about the puzzle of identity as it is about madness. The governess in The Turn of the Screw yearns to be a heroine, to do something brave and noble, and to attract the attention of the dashing employer whose sole directive is that she never, ever bother him. She wants to be someone else. Without the mission of protecting her two young charges from mortal danger, she’s merely a woman squandering her youth in the middle of nowhere, taking care of children who will only grow up to leave her behind.

Is the house she presides over haunted by the ghost of brutish Peter Quint and his lover, her predecessor, the sexually degraded Miss Jessel? Or is it haunted by some half-formed, half-desired alternate version of the nameless governess herself? Eleanor may be the target of The Haunting of Hill House, or she may be the one doing the haunting. After all, Dr. Montague invited her to participate in the project because of a poltergeist incident during her childhood.

(Excerpted from “Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House: An Introduction” by Laura Miller ©2006, reprinted by permission)

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

. . . . . . . . . .

The Haunting of Hill House was well received 1959. Here’s a typical review, giving a glimpse into the plot and characters of this classic work of psychological terror that bears Shirley Jackson’s the unique stamp.

From the original 1959 review by H.G. Rogers from The Literary Guideposts syndicated column, November, 1959: Way off in the hills at the end of a lonely road behind a locked gate stands Hill House. Eighty years old, the sprawling place with a tower, countless rooms, and doors upon doors upon doors, has been the scene of several deaths. The scared people in the nearby village avoid it like a nighttime graveyard.

Dr. Montague, student of ghosts and their goings-on, rents the building, invites a young man and two girls to stay with him and try to catch a spook. They are Luke, heir to the property, and Theodora and Eleanor, both with some psychic experiences. They will be joined by Mrs. Montague and a friend who works a planchette in anticipation of messages from the spirit world.

A surly pair of caretakers gets this odd house party off to a creepy start, and then in the quiet of the night the gremlins come banging down, thumping deafeningly on the walls and then softly, murderously feeling along with them with their fingertips. Doors close with no one to close them, deadly cold drafts blow with no lace to blow from, mysterious presences flutter by unseen.

Miss Jackson isn’t saying right out that she believes in ghosts, but she does say: People who are bound to see ghosts see them, and what they think they see can hurt them.

As between her children, about whom she has written, and her ghosts, I prefer, literally, the ghosts, and the loudest and most terrifying “boo” utter in contemporary fiction was sounded in her short story, “The Lottery.” This novel gives you some queasy moments, but the climax is not one of them.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

Though The Haunting of Hill House is no longer widely read, it has lingered in the imagination through film and theater, having been adapted into two feature films and a stage play. Most recently, it was much expanded into a multipart 2018 Netflix series. Critical reaction has been mixed, as in this review in The Atlantic, and it’s probably safe to describe it as inspired by Shirley Jackson’s novel rather than adapted from it, as it departs markedly from the original.

Circling back to Laura Miller’s insights:

Jackson’s ghost story, published in 1959 was a hit; it became a bestseller, the critics praised it, and the movie rights sold for a goodly sum. The incipient madness of Eleanor Vance seemed to affect her creator, though — or perhaps it was the other way around.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle is narrated by girl who is even more disturbed; at one point, she sets the house on fire to scare off her sister’s suitor. Jackson, a mercurial personality at best and aggravated by the prescription amphetamines she took like aspirin, experienced her own psychic disintegration not long after finishing “Castle,” a breakdown triggered when one in her husband’s many affairs with Bennington students took an uncharacteristically serious turn.

Eventually, Jackson pulled herself together with the help of a psychiatrist, but the burden of so many years worth of bad habits proved to be harder to conquer. She died in her sleep, of cardiac arrest, at age 48.

The Haunting of Hill House, after “The Lottery,” is the work most often associated with Jackson, but she is no longer widely read. This isn’t necessarily surprising; the successful novelists of one generation often evaporate from the awareness of the next, and it probably didn’t help her reputation in literary circles that she sometimes wrote as a kind of thinking-woman’s Erma Bombeck. (Then even more than now, the domestic realm was viewed as insufficiently serious.)

Still, Jackson’s clean, terse style and her tough-mindedness ought to appeal to the kind of readers who keep Patricia Highsmith and James M. Cain in print today. In a way, Jackson was a kindred spirit to the hard-boiled genre novelists of her time. She also depicted the cruel jokes of fate and chance unfolding in an amoral universe. It’s just that instead of doing it with men and guns, she chose to write about mad, lonely girls and big, sinister houses.

(Excerpted from “Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House: An Introduction” by Laura Miller ©2006, reprinted by permission. Special thanks to Laura Miller for her insights. Laura is currently books and culture columnist at Slate. In 1995, she co-founded Salon.com and worked there as an editor and staff writer for 20 years. Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, Harper’s, The Guardian, Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, and many other publications, including the New York Times Book Review, where she wrote the Last Word column for two years. She is the editor of the Salon.com Reader’s Guide to Contemporary Authors (Penguin, 2000).

. . . . . . . . . .

Watch the series adaptation of The Haunting of Hill House on Netflix

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from The Haunting of Hill House

“To learn what we fear is to learn who we are. Horror defies our boundaries and illuminates our souls.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Fear and guilt are sisters.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Fear,” the doctor said, “is the relinquishment of logic, the willing relinquishing of reasonable patterns. We yield to it or we fight it, but we cannot meet it halfway.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She had taken to wondering lately, during these swift-counted years, what had been done with all those wasted summer days; how could she have spent them so wantonly?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I have spent an all but sleepless night, I have told lies and made a fool of myself, and the very air tastes like wine. I have been frightened half out of my foolish wits, but I have somehow earned this joy; I have been waiting for it for so long.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Am I walking toward something I should be running away from?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Eleanor looked up, surprised; the little girl was sliding back in her chair, sullenly refusing her milk, while her father frowned and her brother giggled and her mother said calmly, ‘She wants her cup of stars.’

Indeed yes, Eleanor thought; indeed, so do I; a cup of stars, of course.

‘Her little cup,’ the mother was explaining, smiling apologetically at the waitress, who was thunderstruck at the thought that the mill’s good country milk was not rich enough for the little girl. ‘It has stars in the bottom, and she always drinks her milk from it at home. She calls it her cup of stars because she can see the stars while she drinks her milk.’ The waitress nodded, unconvinced, and the mother told the little girl, ‘You’ll have your milk from your cup of stars tonight when we get home. But just for now, just to be a very good little girl, will you take a little milk from this glass?’

Don’t do it, Eleanor told the little girl; insist on your cup of stars; once they have trapped you into being like everyone else you will never see your cup of stars again; don’t do it; and the little girl glanced at her, and smiled a little subtle, dimpling, wholly comprehending smile, and shook her head stubbornly at the glass. Brave girl, Eleanor thought; wise, brave girl.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It was a house without kindness, never meant to be lived in, not a fit place for people or for love or for hope. Exorcism cannot alter the countenance of a house; Hill House would stay as it was until it was destroyed.”

. . . . . . . . . .

More about The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson

Wikipedia Reader discussion on Goodreads Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House: An Introduction. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson (1959) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 27, 2019

12 Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay

Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892 – 1950) has long been regarded as a major twentieth-century figure in the genre of poetry. Edna immersed herself in great works of literature from an early age. She read Shakespeare, Keats, Longfellow, Shelley, and Wordsworth.

At age of sixteen she compiled a dozen or so poems into a copybook and presented them to her mother as “Poetical Works of Vincent Millay.” In 1912, encouraged by her mother, Edna, then 19, sent her poem, “Renascence” to The Lyric Year, a magazine that held a yearly poetry contest and published winning entries. Though she didn’t win, the poem gained her a great deal of attention and launched her writing career.

A Few Figs from Thistles (1921), her first major collection, explored female sexuality, among other themes. Second April (also 1921) dealt with heartbreak, nature, and death. In 1923, Edna’s fourth volume of poems, The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver, won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. She was the first woman to win a Pulitzer, and only the second person to receive the prize for poetry.

Edna achieved the status of superstar status, something that was — and still is — rare for a poet. Throughout the 1920s, she recited to enthusiastic, sold-out crowds during her many reading tours at home and abroad. Perhaps she did burn her candle at both ends, as described in one of her most famous poems, First Fig, as she didn’t live long past the age of fifty. Here is a selection of 12 poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay from some of her earlier collections.

TavernI'll keep a little tavernBelow the high hill's crest,

Wherein all grey-eyed people

May set them down and rest.

There shall be plates a-plenty,

And mugs to melt the chill

Of all the grey-eyed people

Who happen up the hill.

There sound will sleep the traveller,

And dream his journey's end,

But I will rouse at midnight

The falling fire to tend.

Aye, 'tis a curious fancy—

But all the good I know

Was taught me out of two grey eyes

A long time ago.

SorrowSorrow like a ceaseless rain

Beats upon my heart.

People twist and scream in pain,—

Dawn will find them still again;

This has neither wax nor wane,

Neither stop nor start.

People dress and go to town;

I sit in my chair.

All my thoughts are slow and brown:

Standing up or sitting down

Little matters, or what gown

Or what shoes I wear.

Ashes of LifeLove has gone and left me and the days are all alike;

Eat I must, and sleep I will, — and would that night were here!

But ah! — to lie awake and hear the slow hours strike!

Would that it were day again! — with twilight near!

Love has gone and left me and I don't know what to do;

This or that or what you will is all the same to me;

But all the things that I begin I leave before I'm through, —

There's little use in anything as far as I can see.

Love has gone and left me, — and the neighbors knock and borrow,

And life goes on forever like the gnawing of a mouse, —

And to-morrow and to-morrow and to-morrow and to-morrow

There's this little street and this little house.

First FigMy candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—

It gives a lovely light!

EbbI know what my heart is like

Since your love died:

It is like a hollow ledge

Holding a little pool

Left there by the tide,

A little tepid pool,

Drying inward from the edge.

Song of a Second AprilApril this year, not otherwise

Than April of a year ago,

Is full of whispers, full of sighs,

Of dazzling mud and dingy snow;

Hepaticas that pleased you so

Are here again, and butterflies.

There rings a hammering all day,

And shingles lie about the doors;

In orchards near and far away

The grey wood-pecker taps and bores;

The men are merry at their chores,

And children earnest at their play.

The larger streams run still and deep,

Noisy and swift the small brooks run

Among the mullein stalks the sheep

Go up the hillside in the sun,

Pensively,—only you are gone,

You that alone I cared to keep.

What Lips My Lips Have KissedWhat lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why,

I have forgotten, and what arms have lain

Under my head till morning; but the rain

Is full of ghosts tonight, that tap and sigh

Upon the glass and listen for reply,

And in my heart there stirs a quiet pain

For unremembered lads that not again

Will turn to me at midnight with a cry.

Thus in winter stands the lonely tree,

Nor knows what birds have vanished one by one,

Yet knows its boughs more silent than before:

I cannot say what loves have come and gone,

I only know that summer sang in me

A little while, that in me sings no more.

DepartureIt's little I care what path I take,

And where it leads it's little I care,

But out of this house, lest my heart break,

I must go, and off somewhere!

It's little I know what's in my heart,

What's in my mind it's little I know,

But there's that in me must up and start,

And it's little I care where my feet go!

I wish I could walk for a day and a night,

And find me at dawn in a desolate place,

With never the rut of a road in sight,

Or the roof of a house, or the eyes of a face.

I wish I could walk till my blood should spout,

And drop me, never to stir again,

On a shore that is wide, for the tide is out,

And the weedy rocks are bare to the rain.

But dump or dock, where the path I take

Brings up, it's little enough I care,

And it's little I'd mind the fuss they'll make,

Huddled dead in a ditch somewhere.

"Is something the matter, dear," she said,

"That you sit at your work so silently?"

"No, mother, no—'twas a knot in my thread.

There goes the kettle—I'll make the tea."

The BetrothalOh, come, my lad, or go, my lad,

And love me if you like!

I hardly hear the door shut

Or the knocker strike.

Oh, bring me gifts or beg me gifts,

And wed me if you will!

I'd make a man a good wife,

Sensible and still.

And why should I be cold, my lad,

And why should you repine,

Because I love a dark head

That never will be mine?

I might as well be easing you

As lie alone in bed

And waste the night in wanting

A cruel dark head!

You might as well be calling yours

What never will be his,

And one of us be happy;

There's few enough as is.Dirge Without MusicI am not resigned to the shutting away of loving hearts in the hard ground.

So it is, and so it will be, for so it has been, time out of mind:

Into the darkness they go, the wise and the lovely. Crowned

With lilies and with laurel they go; but I am not resigned.

Lovers and thinkers, into the earth with you.

Be one with the dull, the indiscriminate dust.

A fragment of what you felt, of what you knew,

A formula, a phrase remains,—but the best is lost.

The answers quick and keen, the honest look, the laughter, the love,—

They are gone. They are gone to feed the roses. Elegant and curled

Is the blossom. Fragrant is the blossom. I know. But I do not approve.

More precious was the light in your eyes than all the roses in the world.

Down, down, down into the darkness of the grave

Gently they go, the beautiful, the tender, the kind;

Quietly they go, the intelligent, the witty, the brave.

I know. But I do not approve. And I am not resigned.Love is Not AllLove is not all: it is not meat nor drink

Nor slumber nor a roof against the rain;

Nor yet a floating spar to men that sink

And rise and sink and rise and sink again;

Love can not fill the thickened lung with breath,

Nor clean the blood, nor set the fractured bone;

Yet many a man is making friends with death

Even as I speak, for lack of love alone.

It well may be that in a difficult hour,

Pinned down by pain and moaning for release,

Or nagged by want past resolution's power,

I might be driven to sell your love for peace,

Or trade the memory of this night for food.

It well may be. I do not think I would.

The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver“Son,” said my mother,

When I was knee-high,

“You’ve need of clothes to cover you,

And not a rag have I.

“There’s nothing in the house

To make a boy breeches,

Nor shears to cut a cloth with

Nor thread to take stitches.

“There’s nothing in the house

But a loaf-end of rye,

And a harp with a woman’s head

Nobody will buy,”

And she began to cry.

That was in the early fall.

When came the late fall,

“Son,” she said, “the sight of you

Makes your mother’s blood crawl,—

“Little skinny shoulder-blades

Sticking through your clothes!

And where you’ll get a jacket from

God above knows.

“It’s lucky for me, lad,

Your daddy’s in the ground,

And can’t see the way I let

His son go around!”

And she made a queer sound.

That was in the late fall.

When the winter came,

I’d not a pair of breeches

Nor a shirt to my name.

I couldn’t go to school,

Or out of doors to play.

And all the other little boys

Passed our way.

“Son,” said my mother,

“Come, climb into my lap,

And I’ll chafe your little bones

While you take a nap.”

And, oh, but we were silly

For half an hour or more,

Me with my long legs

Dragging on the floor,

A-rock-rock-rocking

To a mother-goose rhyme!

Oh, but we were happy

For half an hour’s time!

But there was I, a great boy,

And what would folks say

To hear my mother singing me

To sleep all day,

In such a daft way?

Men say the winter

Was bad that year;

Fuel was scarce,

And food was dear.

A wind with a wolf’s head

Howled about our door,

And we burned up the chairs

And sat on the floor.

All that was left us

Was a chair we couldn’t break,

And the harp with a woman’s head

Nobody would take,

For song or pity’s sake.

The night before Christmas

I cried with the cold,

I cried myself to sleep

Like a two-year-old.

And in the deep night

I felt my mother rise,

And stare down upon me

With love in her eyes.

I saw my mother sitting

On the one good chair,

A light falling on her

From I couldn’t tell where,

Looking nineteen,

And not a day older,

And the harp with a woman’s head

Leaned against her shoulder.

Her thin fingers, moving

In the thin, tall strings,

Were weav-weav-weaving

Wonderful things.

Many bright threads,

From where I couldn’t see,

Were running through the harp-strings

Rapidly,

And gold threads whistling

Through my mother’s hand.

I saw the web grow,

And the pattern expand.

She wove a child’s jacket,

And when it was done

She laid it on the floor

And wove another one.

She wove a red cloak

So regal to see,

“She’s made it for a king’s son,”

I said, “and not for me.”

But I knew it was for me.

She wove a pair of breeches

Quicker than that!

She wove a pair of boots

And a little cocked hat.

She wove a pair of mittens,

She wove a little blouse,

She wove all night

In the still, cold house.

She sang as she worked,

And the harp-strings spoke;

Her voice never faltered,

And the thread never broke.

And when I awoke,—

There sat my mother

With the harp against her shoulder

Looking nineteen

And not a day older,

A smile about her lips,

And a light about her head,

And her hands in the harp-strings

Frozen dead.

And piled up beside her

And toppling to the skies,

Were the clothes of a king’s son,

Just my size.

The post 12 Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 26, 2019

My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier (1951)

My Cousin Rachel is a novel by British author Daphne du Maurier, first published in the U.K. in 1951 and in the U.S. in 1952. Echoing du Maurier’s masterwork, Rebecca, My Cousin Rachel is a romantic thriller. It’s set primarily on a large estate in Cornwall, where du Maurier took real-life inspiration at Antony House. There she saw a portrait of a woman named Rachel Carew, and the creative spark was lit.

So highly anticipated was My Cousin Rachel’s publication that the film rights were fought over even before it was published. David O. Selznick’s 1940 film adaptation of Rebecca had been hugely successful, giving him plenty of confidence inMy Cousin Rachel’s prospects. In 1951, the year the novel was published in the U.K., Selznick sought the film rights.

But his rival, Darryl Zanuck of 20th Century-Fox, had apparently secured the rights to the film just twenty minutes before Selznick was set to make his bid. The 1952 film starred Olivia de Haviland in the title role, with Richard Burton co-starring.

You know a story has touched a nerve when multiple television and film adaptations continue to be produced. My Cousin Rachel was aired by the BBC as a mini-series in 1983, and as a modern-day radio play, also by the BBC in 2011. Most recently, a film adaptation was released in 2017 starring the aptly named Rachel Weisz in the title role.

. . . . . . . . . . .

See also: Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

. . . . . . . . . . .

It’s worth seeing both the 1952 and 2017 film versions, but it’s always best to read the book first! My Cousin Rachel was quite well received on both sides of the Atlantic. Here are two views from its initial publication by American reviewers highlighting the intriguingly ambiguous plot and character of its antiheroine:

The Golden Du Maurier Touch

From the original review by Harrison Smith of My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier in The Berkshire Review, February 9, 1952:

Some prominent English families have a way of inheriting talent for several generations. The du Mauriers are an example of this trait. Beginning at age 24, Daphne, its youngest member, had published in the course of five years three literary novels, a notable book about her distinguished actor-father Gerald, and the resoundingly successful romance Jamaica Inn.

The romantic streak in the family is further illustrated by her grandfather, George du Maurier, who was not only an artist but the author of two immensely successful books, Trilby and Peter Ibbetson.

A worthy successor to Rebecca

The best-remembered of all of du Maurier’s books is Rebecca, the classic story of a young and devoted second wife who arrived at Maxim de Winter’s historic country house to discover much that was unexpected, sinister, and mysterious.

My Cousin Rachel may prove equally successful, though to many, the story may not be as appealing. This is for the simple reason that Rachel is years older than Rebecca and is a beautiful but enigmatic, devious woman, half-Italian by birth.

The novel is actually a mystery story to the end, for the reader never knows whether Rachel Ashley is guilty of the murder of her elderly English husband in her Florentine villa, or whether she is equally guilty of an attempt to poison his young cousin and heir in the old family home in Cornwall.

There can be no argument that the fascination of My Cousin Rachel makes it difficult to take time out for eating or sleeping. But the evidence of Rachel’s innocence or guilt will be argued for a long time and will be a subject for the film version as well.

The case against and in defense of Rachel

For the prosecution, this beautiful and fascinating woman can be accused of having led a riotous life with her first husband, an Italian count, and of having married the elder Ashley for his more and then poisoned him.

There is a mysterious Italian who follows her to young Philip Ashleys Cornwall home who was likely her lover. The symptoms of the malady that nearly kill this young man, who had never loved another, duplicate the fatal illness of the elder Ashley. There can be no doubt that Rachel was a skillful seducer of the inexperienced young man of 24, who became so enamored with her that he gave her the family jewels and made a will surrendering his fortune to her upon his death.

The defense can only prove that there is no actual evidence of her guilt, and the final decision will depend on whether the reader falls in love with her, and thus becomes her defender, or loathes her as he or she would a poisonous snake.

Is she guilty or innocent?

This reviewer believes that Daphne Du Maurier has weighted the evidence heavily against the heroine, but is still left in doubt of the author’s own opinion of her guilt or innocence. At any rate, this story once again proves that the author is the most entrancing of living romantic novelists and the ablest constructor of complex and absorbing plots.

. . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy: Jamaica Inn by Daphne du Maurier

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review of My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier in Council Bluffs Nonpareil, February 1952: My Cousin Rachel is reminiscent of Daphne Du Maurier’s best seller Rebecca. Because Rachel, like Rebecca, remains a puzzle to the end. Devil or angel? The reader must decide.

The story is told by Phillip Kendall, a very conscience-stricken and unhappy young man. Phillip has been raised to be a young Devonshire squire by a doting bachelor uncle, Ambrose Ashley.

One winter Ambrose takes off for Italy’s warmer clime, leaving his heir, Phillip, to take care of his properties. In Italy Uncle Ambrose does a startling thing for a man of his advancing years. He meets the beautiful Contessa Sangaletti. She is also, writes Ambrose, a widow and an Englishwoman and a distant cousin of the Devonshire Ashleys.

They are married and settle in Rachel’s villa in Florence. The tone of Ambrose’s letters changes. They hint at dark deeds, mention Ambrose’s failing health, and a sinister Signor Rinaldi, devoted friend of Rachel.

Phillip hastens to Italy only to learn of his uncle’s death, also shrouded in mystery. And Rachel has disappeared. The youth returns to Devonshire and shortly thereafter he has a beautiful and charming house guest — Rachel.

Despite his growing distrust and suspicions, the worldly and experienced Rachel soon has Phillip enraptured — and snared. Phillip becomes suddenly and dangerously ill. His suspicions of Rachel, backed by those of his childhood playmate Louise Kendall, grow. What Phillip does or does not do about his suspicions is the twist at the end of the tale.

. . . . . . . . . . .

My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about My Cousin Rachel

Wikipedia Reader discussion on Goodreads 2017 film version of My Cousin Rachel. . . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier (1951) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 24, 2019

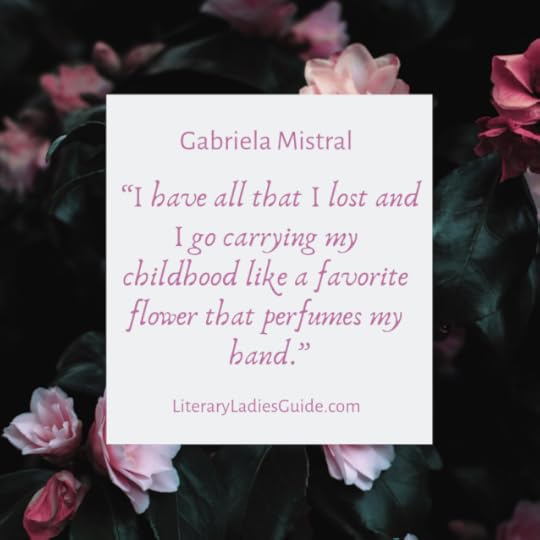

Endearing Quotes by Gabriela Mistral, Latina Nobel Prize Winner

Gabriela Mistral, born Lucila Godoy Alcayaga (April 7, 1889 – January 10, 1957), was a Chilean poet, educator, diplomat, and feminist. She was also best known for being the first Latin American woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Born in Vicuña, Chile she was raised in the small Andean village of Montegrande where her family was rather poor. She attended a primary school taught by her older sister, Emelina Molina, at the age of nine but only attended for three years.

Though she stopped formally attending school at the age of twelve, she became an educator just three years later. During her time as an educator, she began writing poetry and using her pen pal name, Gabriela Mistral.

Since then, Mistral’s poetry was fueled by heartbreak and life experiences. You might enjoy these 10 poems by Gabriela Mistral. Here are quotes by the talented and intellectual Nobel Prize in Literature recipient, Gabriela Mistral:

. . . . . . . . . .

“Let the earth look at me, and bless me, for now I am fecund and sacred, like the palms and the furrows.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Gabriela Mistral

. . . . . . . . . .

“I have all that I lost and I go carrying my childhood like a favorite flower that perfumes my hand.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I have a faithful joy and a joy that is lost. One is like a rose, the other, a thorn. The one that was stolen I have not lost.” – “Selected poems of Gabriela Mistral”, 1971

. . . . . . . . . .

“All night I have suffered; all night my flesh has trembled to bring forth its gift. The sweat of death is on my forehead; but it is not death, it is life!”

. . . . . . . . . .

“We are guilty of many errors and many faults, But our worst crime is abandoning the children, Neglecting the fountain of life. Many of the things we need can wait. The child cannot. Right now is the time his bones are being formed, His blood is being made, And his senses are being developed. To him we cannot answer ‘Tomorrow.’ His name is ‘Today.’” – “His Name Is Today”, mid 1900s

. . . . . . . . . .

“For me, religiosity is … the constant remembrance of the presence of the soul.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“At this moment, by an undeserved stroke of fortune, I am the direct voice of the poets of my race and the indirect voice for the noble Spanish and Portuguese tongues.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Many things we need can wait. The child cannot. Now is the time his bones are formed, his mind developed. To him we cannot say tomorrow, his name is today.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“You saw her a hundred times, but not once did you look at her.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“In the secret of night, my prayer climbs like the liana, My prayer is, and I am not. It grows, and I perish. I have only my hard breath, my reason and my madness. I cling to the vine of my prayer. I tend it at the root of the stalk of night.” – “Selected poems of Gabriela Mistral”, 1971

. . . . . . . . . .

“You shall create beauty not to excite the senses but to give sustenance to the soul. ”

. . . . . . . . . .

8 Fascinating Facts About Gabriela Mistral, Latina Nobel Prize Winner

. . . . . . . . . .

“Love that stammers, that stutters, is apt to be the love that loves best.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“We are guilty of many errors and many faults, but our worst crime is abandoning the children, neglecting the fountain of life. Many of the things we need can wait. The child cannot. Right now is the time his bones are being formed, his blood is being made, and his senses are being developed. To him we cannot answer ‘Tomorrow,’ his name is today.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Love beauty; it is the shadow of God on the universe.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I write poetry because I can’t disobey the impulse; it would be like blocking a spring that surges up in my throat. For a long time I’ve been the servant of the song that comes, that appears and can’t be buried away. How to seal myself up now?…It no longer matters to me who receives what I submit. What I carry out is, in that respect, greater and deeper than I, I am merely the channel.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Many things we need can wait. The child cannot. Now is the time his bones are formed, his mind developed. To him we cannot say tomorrow, his name is today.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Now what mattered to me no longer matters.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Everyone left and we have remained on a path that goes on without us.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She talks with an accent of savage seas. Her breathing is the breath of the wilderness, she has loved with a passion that makes her blanch, which she never mentions and which would be like the map of another star if she told us.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She loved only her lover and Iphigenia in the narrowness of her cold breast.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The night itself is riddled with her, wide with her, and alive with her.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Writing tends to cheer me; it always soothes my spirit and blesses me with the gift of an innocent, tender, childlike day. It is the sensation of having spent a few hours in my homeland, with my customs, free whims, my total freedom.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Gabriela Mistral page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

“I write poetry because I can’t disobey the impulse; it would be like blocking a spring that surges up in my throat. For a long time I’ve been the servant of the song that comes, that appears and can’t be buried away. How to seal myself up now?…It no longer matters to me who receives what I submit. What I carry out is, in that respect, greater and deeper than I, I am merely the channel.” – Madwomen, 2009

. . . . . . . . . .

The post Endearing Quotes by Gabriela Mistral, Latina Nobel Prize Winner appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Renaissance House: A Retreat for Writers and Artists

RENAISSANCE HOUSE RETREAT FOR WRITERS AND ARTISTS IN OAK BLUFFS RECEIVES A GRANT FROM SUSTAINABLE ARTS FOUNDATION AS IT ENTERS 20TH YEAR

Renaissance House: A Retreat for Writers and Artists has received a grant from The Sustainable Arts Foundation to fund a full scholarship to a resident and their child. The resident will be able to complete the program while the child goes to day camp or some other activity.

Applications are now being accepted for the 2019 season as well as for the scholarship.

“The retreat provides the time in which to create new works or finish existing ones. Renaissance House is one of the few retreats designed for issue-oriented writers, writers of color and writers of social justice,” explained Abigail McGrath, founder and director of Renaissance House, daughter of poet Helene Johnson and niece of Dorothy West. “The program is offered to artists who do not have the luxury of time.”

In order to write, a writer must have to just look out the window and stare,” Helene Johnson. “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction,” Virginia Woolf famously wrote. Renaissance House is not able to give money, but they do offer a room of your own with a window to look out and stare.

. . . . . . . . . .

Portrait of Helene Johnson, a respected poet of the Harlem Renaissance era,

Portrait of Helene Johnson, a respected poet of the Harlem Renaissance era,

and mother of Renaissance founder Abigail McGrath. The photo is inscribed

to her cousin, fellow writer Dorothy West, and dated 12/22/31

. . . . . . . . . .

Helene Johnson was a poet and summer Martha’s Vineyard resident who had to stop writing in order to support her family. Her cousin, novelist and short story writer Dorothy West, was a year-round Martha’s Vineyard island resident who worked at Harbor Side Restaurant until Jacqueline Kennedy spotted her writing in the MV Gazette and gave her the opportunity to simply “stare at the trees and do nothing.”

This enabled West to write The Wedding, a best-selling novel inspired by the interracial marriage of Abigail and Tony McGrath. The Wedding was also produced as a television mini-series by Oprah Winfrey and starred Halle Berry.

About this special grant from the Sustainable Arts Foundation: “Renaissance House is committed to helping parents gain access to the resources, community, and, most importantly, the creative time that they offer. The ripple effect of this commitment is powerful, as it helps to normalize the still-radical idea of a parent artist, and makes the road a little less lonely for each one.

We are glad to partner with Renaissance House to provide not just a short-term creative opportunity, but a reminder to each resident that their work is vital, and that there are people and organizations committed to helping them make it. Finally, they are sending a clear message to non-parents that a creative life with family is possible.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Renaissance House on Martha’s Vineyard is located in charming Oak Bluffs

. . . . . . . . . .

The Renaissance House program includes formal sit-down dinners and salons by local residents, such as: Jill Nelson, Jessica Harris, Kate Feiffer, Susan Kline, Robert Hayden, Marty Nadler, Nat Benjamin, Shirley Craig, Brooks Robards, Janet Hill, Elisabeth Benedict, Justen Ahern, Daniel Waters, Mike West, and on and on.

“Renaissance House admits writers to the program who span different stages in their careers—from emerging writers to notable award winners,” explained McGrath, who founded the retreat in 1999. “The point of the program is to give artists ‘alone’ time, away from their families and their jobs and the everyday chores that make up a life.

Our residents are: a hotel maid who writes poetry during her lunch hour, a single mother filmmaker, a factory worker who learned Mandarin in order to write poetry in that language, a bestselling author of note who needed a safe place to take chances, a journalist looking for the truth, a PhD candidate doing her best not to ‘write formulaic for the PhD.” And in general, it is for artists who need “a room of their own.”

Renaissance House also has locations in Napanoch, NY and Palm Springs.

For more information, visit the website: Renaissance House or contact Renaissancehse@aol.com | (917) 747-0367

Abigail McGrath

P.O. Box 4776

Vineyard Haven, MA 02568

. . . . . . . . . .

Dorothy West at her home in Martha’s Vineyard, 1998

. . . . . . . . . .

This history of Renaissance House and its mission is from Abigail McGrath:

”I was raised by my mother, Helene Johnson, the Harlem Renaissance Poet, and Dorothy West, the Harlem Renaissance novelist. They were cousins who were born within the same year and died a few years apart. People asked me what I was going to do to celebrate their lives. My first thought was to offer a scholarship to women whose lives closely paralleled theirs. But, there already were such scholarships.

Then I remembered how difficult it was for them to find time to write. Both of them had to have pedantic, time consuming jobs just to be able to survive; time to write became more and more of a luxury. So, I created Renaissance House as a tribute to them both. It is located in the former home of Helene Johnson which is next door to the home of Dorothy West.

They were both prodigies of a sort and both writers of such substance that they helped create the Harlem Renaissance, a period in the arts which has not been rivaled since. When the two teenage girls arrived in New York City, they were beset with issues unknown to them in their native Boston. The reality of everyday, urban life, of working at a job and supporting a family took them away from their writing.

When asked why she stopped her major flow of writing at such a young age, Helene Johnson said: “In order to create, a person needs time in which to do nothing, to simply stare out a window and let thoughts come to them.”

That is the essence of Renaissance House. A place to muster up one’s energy and burst forward with works that may have had to take a back seat in one’s everyday world. Renaissance House is a program of the Helene Johnson and Dorothy West Foundation For Artists In Need. The foundation funds specific needs for all artists especially in the fields of residency.”

The post Renaissance House: A Retreat for Writers and Artists appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

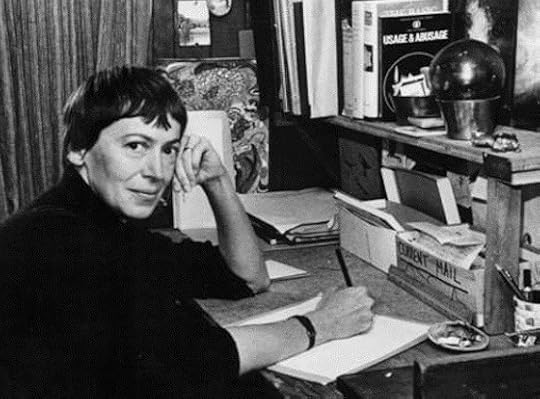

Ursula K. Le Guin

Ursula K. Le Guin (1929 – 2018), born Ursula Krober, was known primarily as a masterful writer of science fiction and fantasy, though she wrote across many genres. The imaginary worlds she created were commentaries on our real world, with all the complexities of human nature. She also produced children’s books, short stories, essays, and poetry.

Her lifelong interest in mythology influenced her mastery of the fantastic in her writings. With an immensely prolific and respected career to her credit, she is perhaps best remembered for The Left Hand of Darkness and the Earthsea series. Lavinia (2008) also made quite a splash. Some of the themes explored in her speculative works include gender and sexuality, freedom, political systems, and morality.

Background and family lifeUrsula was born in Berkeley, California. Her father, Alfred L. Kroeber, was a respected anthropologist; her mother, Theodora Kroeber, was an author engaged in Native American matters. Ursula’s childhood was intellectually and artistically rich, with a large family and academic community.

She studied at Radcliffe College and Columbia University, earning her Master’s degree in French and Italian Renaissance literature by the age of twenty-two, in 1952. While on a steamer sailing to France in 1953, she met Charles Le Guin, and the two married just a few months later. They settled in Portland, Oregon, where they brought up their three children, and where Charles, a historian, was a professor of history at Portland State University.

Ursula derived comfort and inspiration from the Eastern spiritual traditions of Taoism and Buddhism. She was quoted as saying: “Taoism gave me a handle on how to look at life and how to lead it when I was an adolescent hunting for ways to make sense of the world without going off into the God business.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Ursula in 1973. Photo: NY Public Library

. . . . . . . . . .

When Ursula began writing science fiction in the 1960s, the genre was largely written by and for white men. The books and magazine stories being published were largely space adventures with men of science as their heroes. While striving to become a published writer, Ursula collected many rejections over a number of years.

Ursula’s first novel, Rocannon’s World (1966), adhered to that trope, but a major change was on the horizon. According to a 2013 interview with Ursula Le Guin in The Paris Review :

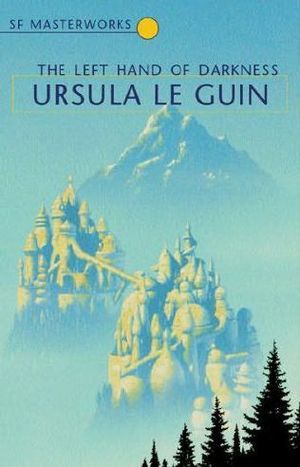

“No single work did more to upend the genre’s conventions than The Left Hand of Darkness (1969). In this novel, her fourth, Le Guin imagined a world whose human inhabitants have no fixed gender: their sexual roles are determined by context and express themselves only once every month. The form of the book is a mosaic of primary sources, an interstellar ethnographer’s notebook, ranging from matter-of-fact journal entries to fragments of alien myth.

Writers as diverse as Zadie Smith and Algis Budrys have cited The Left Hand of Darkness as an influence, and Harold Bloom included it in The Western Canon. In the decades that followed, Le Guin continued to broaden both her range and her readership, writing the fantasy series she has perhaps become best known for, Earthsea, as well as the anarchist utopian allegory The Dispossessed, to name just a few books among dozens.” (— John Wray)

. . . . . . . . . .

Life, Love, Freedom, and Dragons: Quotes by Ursula K. Le Guin

. . . . . . . . . .

The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) was actually the fourth book in a series called the Hainish Cycle. It followed Planet of Exile (1966) and City of Illusions (1967). Yet it was The Left Hand of Darkness that became one of her most visionary novels, and indeed, a groundbreaking work in the genre of science fiction. It describes the Gethenians, an alien race with no fixed gender characteristics until it’s time to mate. The book won the prestigious Nebula and Hugo awards.

A publisher encouraged Ursula to try her hand at young adult fiction, and this resulted in the publication of A Wizard of Earthsea in 1968. Some have speculated that this series was a kind of quiet predecessor of Harry Potter, being the story of a student wizard named Sparrowhawk.

Followed by The Tombs of Atuan (1970), The Farthest Shore (1972) and Tehanu (1990), Tales From Earthsea (2001) and The Other Wind (2001), the series became known simply as Earthsea. Though originally intended for the young adult market, readers of all ages have embraced this series, as evidenced by worldwide sales in the millions.

. . . . . . . . . .

Ursula K. Le Guin page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

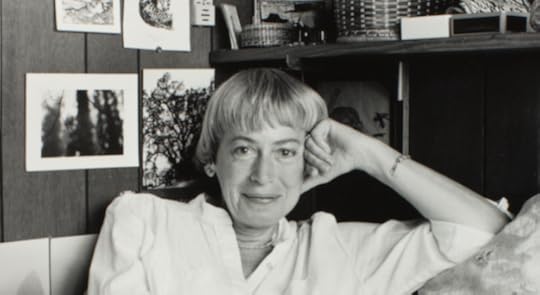

Ursula Le Guin instilled cultural exploration as a vital part to the genre of science fiction. Her characters vibrantly bursting from the page as scientists, anthropologists, diplomats, and travelers. She was described as “fiery” and with having “immense energy” by those who knew her best.

She also spoke eloquently about the art and craft of writing and considered storytelling as a cornerstone of human experience. Generously, she nurtured the dreams of aspiring writers on her website, dispensing advice in her Book View Café. She also wrote essays on feminist issues. A slew of honors came her way during her lifetime, including the Living Legend Medal awarded by the Library of Congress. She won the National Book Award, the Kafka Prize, a number of Nebula and Hugo awards, and many others.

Ursula Le Guin died at her home in Portland, Oregon, on January 22, 2018, at age 88. Stephen King summed up her legacy with a brief tweet: “Ursula K. LeGuin, one of the greats, has passed. Not just a science fiction writer; a literary icon. Godspeed into the galaxy.”

More about Ursula Le Guin on this site

Quotes by Ursula K. Le Guin on Reading, Writing, and Storytelling Life, Love, Freedom, and Dragons: Quotes by Ursula K. Le GuinMajor Works

Ursula Le Guin’s body of work is too vast to list here. See her complete bibliography on Wikipedia.

Hainish Cycle

Rocannon’s World (1966)Planet of Exile (1966)City of Illusions (1967)The Left Hand of Darkness (1969)…and there are many other short stories from the Hainish CycleEarthsea

A Wizard of Earthsea (1968)The Tombs of Atman (1971)The Farthest Shore (1972)Tehanu (1990)Tales from Earthsea (2001)The Other Wind (2001)Orsinia (a cycle of stories and novels from 1961 – 1979, culminating in two omnibus collections, 2016 & 2017)

Catwings (children’s novels)

Catwings (1988)Catwings’ Return (1989)Wonderful Alexander and Catwings(1994)Jane on Her Own (1999)… and numerous other short stories, novels, and novellas, including

Lavinia (2008) “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” (1973)More information

Ursula K. Le Guin official site

Wikipedia Reader discussion of Ursula K. Le Guin’s books on Goodreads Biography.com The Essential Novels of Ursula K. Le Guin. . . . . . . . .

Photo: LitHub

Quotes by Ursula Le Guin on Writing, Reading, and Storytelling

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Ursula K. Le Guin appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.