Nava Atlas's Blog, page 58

March 7, 2020

Selma Lagerlöf

Selma Lagerlöf (November 20, 1858 – March 16, 1940) was a Swedish author who has the distinction of being the first woman ever to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, and the first Swede to win the award.

She was also an active teacher throughout her professional life and in 1914 became the first female admitted to the Swedish Academy.

Once, when asked for her favorite color, Swedish author, Selma Lagerlöf answered, “Sunset.” A suitable answer for a woman who more often chose the thrill of a good story over personal adventure, romanticism over realism, and the pleasures of home over traveling afar.

. . . . . . . . .

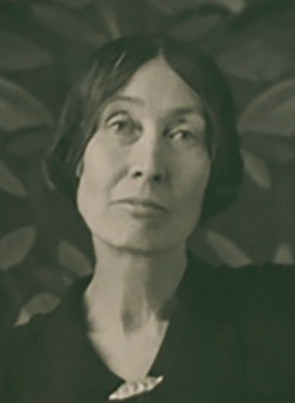

Selma in 1881

. . . . . . . . . .

Childhood and early life

Selma Ottilia Lovisa Lagerlöf was born in Värmland, Sweden, in a single-story red house with a tile roof, called Mårbacka. She describes her early years in this “little homestead, with low buildings overshadowed by giant trees” in The Story of a Story (1902) and Memories of My Childhood (1934).

Her father, Erik Gustav, was a retired army officer, who devoted himself to the life of a gentleman farmer, with progressive ideals that were often unrealized. Her mother, Lovisa Elisabeth, was the daughter of a wealthy merchant and mine owner.

When she was three years old, Selma was diagnosed with paralysis. Her parents took her to the seaside town of Strömstad the following summer, on Sweden’s west coast, in hopes of restoring her health.

She continued to improve, and after a winter’s treatment at Orthopedic Institute in Stockholm, when she was nine years old, she could walk more easily. Still, one hip would remain weakened throughout her life.

One of her remarkable experiences in the city was attending the play “My Rose of the Forest” at the Royal Dramatic Theatre. After she returned home to Mårbacka, the children in the family played theatre, building a wall with beds, bureaus, tables and chairs and covering it with blanket and quilts, to create a stage backdrop.

A great reader

Selma read plays, novels, and poetry throughout her younger years; stories were always important to her. Both her grandmother and her Aunt Ottiliana told her stories and, when Selma was old enough, she read aloud to her mother. Her Aunt Lovisa always had a book hidden in her sewing basket.

In the evenings, after knitting and handicrafts were set aside, the family sometimes read aloud Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales, One Thousand and One Nights, Esaias Tegnér’s Frithiof’s Saga (1825) or Johan Ludvig Runeberg’s Fänrik Ståls sägner (1848).

While she was staying in Stockholm, Selma read her way through Walter Scott’s fiction, before her tenth birthday.

Her mother and her governess did not allow her to read indiscriminately, however; they withdrew Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White (1859) at the most exciting part. And, when she was studying for her first communion, The Barber-Surgeon’s Tales (1853-67) by Zacharias Topelius was declared too “worldly” (although it was acceptable afterwards).

Selma did single out one book from her childhood, however: “For me acquaintance with this Indian story (Osceola) had a decisive effect on my whole life. It awoke in me a deep, powerful desire to produce something as fine. Thanks to this book, I knew as a child that later I should above all love to write novels.”

The novel in question is Osceola the Seminole, or, The Red Fawn of the Flower Land (1858) by Thomas Mayne Reid.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Becoming a teacher

Selma’s governess, Aline, had believed that she might have a talent for storytelling, so she encouraged Selma’s aspirations. When Aline’s older sister, Elin, took over the tutoring, however, she did not recognize any exceptional talent in Selma, so she steered her attention elsewhere.

At twenty, Selma took the examination to attend teachers’ college. Harry Edward Maule, in his 1917 biography, Selma Lagerlöf; The Woman, her Work, her Message, described her anxiety. There were forty applicants and only twenty-five opportunities available for study at the Women’s Superior Training College – Selma’s bid was successful.

After her three-year program, 1882 to 1885, at Högre lärarinneseminariet in Stockholm, Selma was appointed to the Grammar School for Girls in Kandskrona, Skane. She worked there for ten years.

One of her pupils, Anna Clara (later Fru Dr Romanus-Alfven), observed that Selma taught everything from Darwinism to Socialism to Utilitarianism and, as Anna Clara, continues, she “never turned us away with the excuse that we were too young to understand.”

Even while absorbed in teaching, Selma intended to write. She was influenced by works in the college library, including Heroes and Hero Worship by Thomas Carlyle (1841), which she first read in the spring 1884, and reread often, admiring its “direct and fine” prose.

Beginning to write

“Before Aline had advised me not to write, I had felt only a vague, intangible longing, but now this longing has become a fixed determination,” Selma wrote in her memoir.

Carlyle’s prose was an inspiration: “I had the distinct feeling, that I also could write such prose – the ability to write thus straight from the heart, to deal freely and unhindered with the reader, to express irony, love and wisdom in imaginative and brilliant language appealed to me as exquisite.”

When she later discovered his History of the French Revolution (1837), she felt the “same feeling of inner kinship.”

She began writing short stories in 1881 and when her father’s health deteriorated as he approached death, Selma wrote to escape her pain. Much of this work found its way into the five chapters she submitted to a writing contest sponsored by the women’s paper Idun in the spring of 1890.

When Selma won first prize, she requested a year’s leave from teaching to complete her novel and, with the tangible support of friends and colleagues, she undertook the project.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Becoming a published author

In August 1891, Selma finished what would become her best-known novel, The Saga of Gösta Berling, the story of a demoted minister who comes to stay at a manor in Ekeby. His adventures – and those of the other pensioners and residents there – were published at Christmas (also by Idun) and launched a long and impressive career.

Selma had tremendous confidence in her work, as expressed in a letter written to her mother, April 23, 1891 (translated by Anna Nordlund in a 2004 article in Scandinavian Studies (76.2):

“You see, mother, I have a terribly strong belief in the genius inside me; how else could I write and publish anything? I believe that this is the best book yet in Swedish, and I cannot understand when people talk about its deficiencies and how I will improve.”

. . . . . . . .

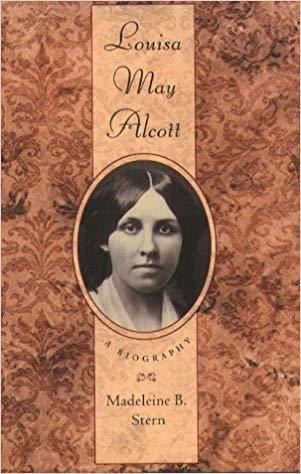

Selma Lagerlöf page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

A prolific career

Her confidence was warranted. Over the course of her career, she would publish more than thirty works. And Värmland would become synonymous with “Gösta Berling” land — travelers from all over the world would be drawn to visit this part of the continent, intrigued by her fiction.

Walter A. Berendsohn’s 1927 biography, Selma Lagerlöf: Her Life and Work notes that Gösta’s action unfolds between two Christmas Eves and “flows on like a river which here and there expands into a quiet lake.”

The background to all of the adventures is Lake Löven (Värmland’s fictionalized Lake Fryken) and while there’s “no exact parallel” in English literature, “there burns in it the same passionate intensity which glows through the pages of Jane Eyre.”

Selma wrote The Wonderful Adventures of Nils (1906) in response to a request from the Swedish school board. Her second volume of stories about a young boy flying over the countryside on a goose would be published five years later.

When the volumes were translated into other languages, the focus was shifted away from the Swedish geographical details to the stories about the natural world, maintaining their simplicity and charm.

Her trio of novels detailing the life and history of a Swedish family was also very popular. It had been published in three volumes – The General’s Ring (1925), Charlotte Löwensköld (1925), and Anna Svärd (1928) – and, later, would be combined into The Ring of the Löwenskölds (1931).

In a 1931 preface to Berendsohn’s biographical work, Vita Sackville-West describes Selma as “a poet writing in prose,” whose “realism is deliberate, whereas her romanticism (with a vengeance) is instinctive.”

She observes “that she writes always as a woman: not one of her books could have been written by a man. Her art is essentially feminine, not masculine, yet without the slightest consciousness of sex.”

. . . . . . . . . .

14 Women Who Won the Nobel Prize in Literature

. . . . . . . . . .

Recognition and awards, including the Nobel Prize

Selma’s peers were not the only admirers of her work. Following the success of The Saga of Gösta Berling, King Oskar and Prince Eugen gave Selma a traveling scholarship in 1895, to free her from the demands of teaching. She traveled on the continent and in the Near East, and her journeys in Italy, with her friend and companion Sophie Elkan, were particularly influential.

In 1909, Selma became the first Swede and the first woman to receive the Nobel Prize for literature. She would also be the first woman, in 1914, to be elected to the prestigious group of eighteen authors and scholars which comprised the Swedish Academy.

Many of her works were made into films after 1919, including a version of her debut novel in 1924 Sweden, Gösta Berling’s Saga, directed by Mauritz Stiller. It starred the young actress Greta Garbo as the Countess Elizabeth and Lars Hanson as Gösta Berling. In 1925, an opera by Riccardo Zandonai would also be produced based on this popular story.

Selma Lagerlöf’s legacy

In her memoir about her childhood in Mårbacka, Selma writes: “When I grow up, I want to live in a house that is painted white and has an upper story and a slate roof; and I would like to have a grand salon where we can dance when we have parties.”

In fact, as soon as she was able to do so, in 1907, she repurchased Mårbacka, which had been sold following her father’s death. With the aid of her Nobel Prize winnings, she was able to finally secure the property in 1910, when she was fifty-one years old.

Thereafter, she wintered in Falun, Dalarna; she spent the rest of the year living on and managing the estate, with its dozens of tenants and a hundred cultivated acres. The homestead now operates as a museum.

In 1911, she addressed the international congress on suffrage in Sweden: “Have we done nothing which entitles us to equal rights with man? Our time on earth has been long – as long as his.” As a young reader, she was moved by stories “about those who have struggled against great odds and who, in the end, have attained success.”

Although her position on suffrage and women’s rights was considered conventional by some, she did recognized social and political injustice and often worked towards change for individuals in need. For instance, the proceeds from the Gösta Berling film were devoted to a “Gösta Berling Fund” dispensed to needy and elderly authoresses.

A documentary film on Selma Lagerlöf was produced by Suntower Entertainment Group (2014), in Swedish, with glimpses of the homestead museum and footage of the author in her later life.

In the same questionnaire, in which she was asked about her favourite colour, Selma was asked to define her favorite quality in a man and in a woman (her answer was the same for both: “Depth and earnestness”) and about her favorite occupation. Her reply – “The study of character” – is still evident in her published works today.

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

More about Selma Lagerlöf

Major works

Selma Lagerlöf was incredibly prolific, and her works are too numerous to list here. For a complete list of her works, denoting which have been translated into English, see this listing on Wikipedia.

Selected Biographies

Selma Lagerlöf: The Woman, her Work, her Message by Harry Edward Maule (1917)

Selma Lagerlöf: Her Life and Work by Walter A. Berendsohn (1931)

Selma Lagerlöf I (1942) and Selma Lagerlöf II by Elin Wägner (1943)

The Critical Reception of Selma Lagerlöf in France by Anne Theodora Nelson (1962)

Selma Lagerlöf by Vivi Edström (1984)

More information

Selma Lagerlöf: A Nobel Mind

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Selma Lagerlöf on the Nobel Prize site

Fourteen-minute video biography in Swedish, including many photographs, and cover images of some of her published works

Read and listen online

Project Gutenberg

Librivox

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Selma Lagerlöf appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 4, 2020

3 Trailblazing Women Sports Journalists: Ina Louise Young, Mary Garber, and Anita Martini

The story of women in American journalism has a common thread: From Colonial times on, women have fought for the right to report. That was (and still remains) especially true for women sports journalists, including this trio of trailblazers: Ina Louise Young, Mary Garber (at right), and Anita Martini.

Sports journalism seems like the final frontier because there have been more women reporting from the battlefield than from the playing field. Consider that during World War II, there were about 140 accredited female war correspondents. That’s not a huge number, but still eclipses the handful of female sports reporters working at the time.

Bias against women sports journalists, past and present

There are more female sports journalists today than ever, but they still face significant bias. And disturbingly but not surprisingly, they’re subject to sexual harassment, a common occurrence in the field of journalism toward women in general.

Do a search on sexism and female journalists and you’ll come across tons of articles like Female Sports Journalists Still Face Rampant Sexism on the Job.

And that’s even setting aside an implicit bias toward covering women athletes and sporting events, but that’s another matter altogether.

Rediscovering pioneering female journalists from the past isn’t particularly difficult, even though they were in a vast minority. But female sports journalists of the past haven’t merely been forgotten; hardly any even existed. That’s what makes the work and lives of determined women like the ones following especially exciting to discover.

To use a fitting cliché, it’s still not an even playing field. Sports journalism is a rough-and-tumble field that might only get easier if there’s strength in numbers — more women stepping up to the plate, so to speak, and getting the respect they deserve.

. . . . . . . . . .

Ina Eloise Young

Ina Eloise Young (1881 – 1947) was America’s first female sports editor. She adored playing sports as well as writing about them.

In high school and her two years at the University of Colorado at Boulder, she was on the basketball and fencing teams. Her favorite sport was baseball, though as a female, she wasn’t allowed to play, only to watch.

Returning to her home town of Trinidad, Colorado, she worked as a general reporter for the local newspaper, the Chronicle-News.

When the 1905 baseball season started, she learned that none of her male colleagues knew how to keep a baseball scorecard. They grudgingly allowed her to report on baseball games until they could find a new man for the job.

But within a few weeks, Ina proved that she was right where she belonged. The following year, the newspaper promoted her to sports editor.

It was quite a novelty for a woman to cover baseball’s national World Series, but that’s just what Ina did starting in 1908. She wrote of her life as a sports reporter and editor:

“I wouldn’t change my place with any woman I know … I’m as happy and independent as a lark, they give me a big salary, six weeks vacation, my expenses paid all over with the ball team, and courteous, considerate treatment. Instinctively they know how to treat a woman. I ask no better society than that of sporting men.”

In that way, Ina Eloise Young was luckier than the rare female sports writers and editors who came after her, like Mary Garber, and many who work in the field today.

More: Society for American Baseball Research

. . . . . . . . .

Mary Garber

Photo: Digital Forsyth

Mary Garber (1916 – 2008) was a sports-crazy girl growing up in 1920s North Carolina who dreamed of becoming an athlete. But topping out at five feet tall and ninety pounds as a teen put an end to her ambition.

After graduating from college in the late 1930s, Mary returned home to Winston-Salem, where she worked as a general reporter for the local newspaper. When the sports stringer joined the Navy during World War II, Mary was given his assignments and fell in love with the job.

Mary was returned — quite unhappily — to general reporting after the war and badgered her editor for a whole year to put her back on the sports beat.

As a female, Mary was often barred from press boxes, locker rooms, and journalism associations. Seeing herself as an underdog, she developed empathy for black athletes and related to their struggle for respect. She was the first white reporter in her segregated state to report on games at black high schools and colleges — stories that no one else would cover.

Mary took courage from her hero, Jackie Robinson. His dignity and attitude gave her courage when, as she recalled, “people would step on me and hurt my feelings.”

Mary was elected president of the Atlantic Coast Conference Sportswriters Association in the late 1970s. The honor was especially sweet because she hadn’t been allowed to join that very group in the 1950s. Mary became a major inspiration to aspiring female sportswriters. A Mary Garber Pioneer Award is given each year to an outstanding woman in sports media.

Just before Mary Garber died in 2008, she was inducted into the Hall of Fame of the National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Association.

More: A Look Back at Pioneering Sports Writer Mary Garber

. . . . . . . .

Anita Martini

Anita Martini (1939–1993) was Texas-based sports journalist who worked in radio and television. A native of Galveston, she began her career on radio in 1965, where she did interviews from the Astrodome stands.

That might sound pretty cool, but it wasn’t — female reporters weren’t allowed on the field. It took seven more years until she could report from the Astrodome’s press box.

Anita’s firsts: Anita achieved a number of firsts for women in sports journalism: In 1973, she became the first female journalist to cover a major league all-star game. The following year, she was the first woman reporter allowed into the locker room of a major-league team. She was also the first woman to co-host a sports talk show in a major radio market (1972 – 1979).

Anita often said that she didn’t become a sports reporter so that she could be the first woman to do this or that. She loved sports, especially baseball, and wanted to be the best at whatever she did.

Though her life was cut short by illness, she was an inspiration for female sports journalists who followed in her footsteps.

In 2007, some years after her death, Anita Martini was inducted into the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame. By 2011, when the Hall presented an exhibit on women in baseball, she was completely left out. This caused a huge outcry from people who had worked with her, and proves how easy it is to forget the trailblazers if their stories aren’t kept alive!

More: Celebrating Women in Baseball While Forgetting Anita Martini

More trailblazing female sports journalists to explore:

Phyllis George

Jayne Kennedy

Leslie Visser

Gayle Gardner

Robin Roberts

Anne Doyle

Christine Brennan

And see more about trailblazing women journalists here on Literary Ladies Guide.

The post 3 Trailblazing Women Sports Journalists: Ina Louise Young, Mary Garber, and Anita Martini appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 3, 2020

The Years by Virginia Woolf (1937) — views from the past and present

The Years by Virginia Woolf (1937) was the last novel she had published in her lifetime. Spanning some fifty years, it covers the trajectory of the respectable Pargiter family from the 1880s to the 1930s.

One of its overarching themes is the passage of time, and it does so by detailing small, mostly private moments of the characters lives. Still, it moves away from the stream of consciousness style that she’s best known for, and into a more traditional narrative.

The novel is less internal than most of Virginia Woolf’s books, and traces the lives of the Pargiter family and the dailyness of their existence. From the Penguin Modern Classics edition:

“The most popular of Virginia Woolf’s novels during her lifetime, The Years is a savage indictment of British society at the turn of the century, edited with an introduction and notes by Jeri Johnson in Penguin Modern Classics.

The Years is the story of three generations of the Pargiter family — their intimacies and estrangements, anxieties and triumphs — mapped out against the bustling rhythms of London’s streets during the first decades of the twentieth century.

Growing up in a typically Victorian household, the Pargiter children must learn to find their footing in an alternative world, where the rules of etiquette have shifted from the drawing-room to the air-raid shelter.

A work of fluid and dazzling lucidity, The Years eschews a simple line of development in favour of a varied and constantly changing style, emphasizes the radical discontinuity of personal experiences and historical events.

Virginia Woolf’s penultimate novel celebrates the resilience of the individual self and, in her dazzlingly fluid and distinctive voice, she confidently paints a broad canvas across time, generation and class.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Virginia Woolf

. . . . . . . . . .

An unusual family saga

The sections of the novel takes place on a single day of a specific year. The year is further defined by the cycle of seasons. For example, the opening year, 1880, has Colonel Abel Pargiter visiting his mistress, Mira, in a dingy suburb. and opens with “It was an uncertain spring.” At home, his wife is dying.

As the novel progresses, we encounter the Colonel’s children. As described by in an essay on the novel by Nuala Casey in London Fictions, they are: “Selfless Eleanor, barrister Maurice, homely Milly, romantic Delia, academic Edward, feminist Rose and free-spirited Martin.” Further, writes Casey:

“At first glance, The Years appears to be a family saga worthy of Galsworthy, a radical departure from Woolf’s modernist masterpieces such as Mrs. Dalloway and The Waves but as you read on it becomes apparent that the author is doing something very interesting and very different here. This is Woolf’s, possibly subconscious, swan song, where she bids farewell to the present through a dreamlike journey through her past.”

The Years was a success on both sides of the Atlantic, and in fact, made it onto several best seller lists in North America despite its very British flavor. It was, by many accounts, the most popular of her novels during her lifetime. Here’s a typically laudatory review from 1937, the year in which it was published:

Virginia Woolf Illuminates the Falling Drops of Time

From the original review in the Montreal Gazette, April 3, 1937: It is six years since Virginia Woolf has given us a novel — and six years is a long time to wait for Virginia Woolf. Especially after such a book as The Waves.

After The Waves, so beautiful, so significant, but so utterly strange in form as to baffle many readers, where was Mrs. Woolf going, what was to be the next step?

The Years is the answer. The monologues have been abandoned. This is natural: they were for the one book; the author has not pressed on to the remote inaccessible reaches of style The Waves might have foreshadowed.

Nor has Mrs. Woolf retreated to the ordinary straightforward narrative of Night and Day and The Voyage out. She is far beyond the earl method; it is too rigid and machine-like for her Ariel spirit, for her philosophy of Time.

The Years belongs with Orlando, Mrs. Dalloway, Jacob’s Room, and To the Lighthouse. If The Waves was a peculiar intensification, The Years is an enlargement of the essential Virginia Woolf.

With the exception of Orlando, which begins in the days of Elizabeth and follows the changing course of English history to the era of Queen Victoria, the new novel covers a greater span of time than any of them — nearly sixty years.

Nothing happens but the passage of Time

Because of its range, someone has spoken of it with the term “epic,” but you have only to compare it with the rolling grandeur of a War and Peace to realize that epic is not the word.

The Years is certainly not dramatic. Parnell dies. King Edward dies. Some of the other characters die. But, except forMrs. Pargiter, whose death opens the book, the deaths are off-stage, or rather off-page. The people simply sink down under the rising tide of Time; they are engulfed change.

The Great War [World War I] comes in, but it, too, is only an incident in the endless flux. There is an air-raid scene, but the bombs fall on far-away streets; the noise is like a disturbance in a dream.

Nothing happens but the passage of Time, slowly, stealthily, working its change. The leaves fall. Mrs. Pargiter dies. The raindrops fall — “One sliding met another and together in on drop they rolled to the bottom of the windowpane.”

Made up of moments and symbols

The word is lyric. In The Years, as always, Mrs. Woolf writes with an uncanny omnipresence, but her way is not to attempt the telling of all, but to dwell on a detail here and a detail there, to illuminate the moment.

But now much more she reveals by telling less. The Years, like life itself, is made up of moment and symbols. A recurring phrase, a gesture, a snatch of a tune, a fallen tree, the cooing of pigeons, they bind all things together.

“All passes, all changes,” thought Kitty, returning to the country from London. But is there a pattern? wondered Eleanor at the family reunion which closes the book.

“Does everything then come over again a little differently? she thought. If so, is there a pattern; a theme, recurring, like music; half remembered, half forseen? … a gigantic pattern, momentarily perceptible?”

And yet — “Directly something got together, it broke. She had a feeling of desolation. And then you have to pick up the pieces, and make something new, sometimes different.”

. . . . . . . . .

The Years by Virginia Woolf on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

All things must pass

Style and philosophy are inseparable. Virginia Woolf writes in moments, the most trivial moments, because that’s the way she gets at life. Life is not a grand structure but a series — no, not even a series, perhaps: a collection — of moments. Is there a pattern? Who knows? Everything changes, everything passes. What is continuity?

Kitty realizes that the land doesn’t belong to her, but to her children. Does it actually belong to them? No; they too, pass.

Abercorn Terrace belonged to the Colonel Abel Pargiter. It was sold. The Colonel lived on and on, after his wife died, while his children grew up. But at last he disappeared. Abercorn Terrace passed away from the Pargiters.

Continuity and change and time — these are the themes the Virginia Woolf explores, as much in The Years as in To the Lighthouse or Jacob’s Room.

The riddle of personality — who are we?

And the riddle of the personality figures largely as well. Who are we? How can we now others if we do not know ourselves? Can people be whole and free?

“There must be another life, here and now,” thought Eleanor. “This is too short, too broken. We know nothing, even about ourselves. We’re only just beginning, she thought, to understand here and there …”

These absorbing philosophical questions go deeper than the surface changes of history. But The Years moves on more than one plane. Almost imperceptibly, we become aware of changing habits, changing manners, the sinking of one generation, and the rising of another.

One despairs of doing justice to this long novel in a review. One cannot even grasp its full significance in one reading. Not this year, not for many a year, will English literature bring forth a novel more beautiful, more profound.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy this review of Mrs. Dalloway

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from The Years

“There must be another life, she thought, sinking back into her chair, exasperated. Not in dreams; but here and now, in this room, with living people.”

“She felt as if she were standing on the edge of a precipice with her hair blown back; she was about to grasp something that just evaded her. There must be another life, here and now, she repeated. This is too short, too broken. We know nothing, even about ourselves.”

“When shall we be free? When shall we live adventurously, wholly, not like cripples in a cave?”

“Love ought to stop on both sides, don’t you think, simultaneously?’ He spoke without any stress on the words, so as not to wake the sleepers. ‘But it won’t — that’s the devil,’ he added in the same undertone.”

“Thinking was torment; why not give up thinking, and drift and dream?”

“Millions of things came back to her. Atoms danced apart and massed themselves. But how did they compose what people called a life?”

“She felt as if things were moving past her as she lay stretched on the bed under the single sheet. But it’s not landscape any longer, she thought; it’s people’s lives, their changing lives.”

“Old age must have endless avenues, stretching away and away down its darkness, she supposed, and now one door opened and then another.”

“But why do I notice everything? She thought. Why must I think? She did not want to think. She wanted to force her mind to become a blank and lie back, and accept quietly, tolerantly, whatever came.”

More about The Years by Virginia Woolf

The Years study guide

The Years on Book Snob

Reader discussion on Goodreads

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Years by Virginia Woolf (1937) — views from the past and present appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 1, 2020

Victoria Woodhull: Rabble Rousing Suffragist and First American Woman to Run for President

Shirley Chisholm may have been the first woman to seek the presidential nomination from one of the two major political parties — that was in 1972 — but exactly one hundred years before that, Victoria Woodhull (1838 – 1927) was the first woman to launch a national presidential campaign. She did so under the banner of the Equal Rights Party.

And running for president long before women even had the right to vote was just one chapter in an incredibly colorful, yet largely forgotten American life.

Victoria was a suffragist, publisher, stockbroker, orator, and agitator. She was also accused at various points of being a bigamist, prostitute, spiritual charlatan, and adulteress.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A controversial figure in a tumultuous time

Imagine this scenario to see why the life of a rabble-rouser like Victoria Woodhull is still relevant today:

A woman is running for president.

The institution of marriage is being redefined, as are sexual standards.

A culture war is raging between organized religion and secular beliefs.

The rights and economic fortunes of women and immigrants are in flux.

Popular spiritual and political leaders are caught in webs of hypocrisy.

A nationwide financial collapse is followed by a resurgence of wealth that benefits the already super-wealthy in a competitive, aggressive era.

No, this isn’t a capsule of 21st-century America. It’s post-Civil War New York City — the late 1860s and early 1870s, to be exact. The issues and struggles are eerily similar, but the players are different — and far more dramatic and flamboyant than those in the public arena today.

Though nearly always mired in controversy, Victoria fought for what she believed in — equal rights for women, labor reform, and “free love” — the 19th-century term for granting women the opportunity to marry, have children, divorce, and take lovers without the interference of government and society.

In one of her many public speeches, she famously declared:

“Yes, I am a free lover! I have an inalienable, constitutional, and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or as short a period as I can, to change that love every day if I please, and with that right neither you nor any law you can frame have any right to interfere.”

With a large, squalid family never far from her side, Victoria and her equally colorful sister, Tennessee (Tennie) Claflin, shocked and challenged a post-Civil War society that was grappling with new ideas about class, religion, sexuality, and the role of women.

“The most famous woman in America”

Victoria and Tennessee, the sibling with whom she was closest, lived the classic rags-to-riches tale twice over, and crossed paths (often with dramatic consequences) with some of the most renowned and influential people of their time:

Cornelius Vanderbilt, Henry Ward Beecher and his sisters (Harriet Beecher Stowe and Isabella Beecher Hooker, and suffragists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were among those who were friends and enemies of Victoria.

Though not as well remembered as some of her famous contemporaries today, Victoria was for a time called “the most famous woman in America.” She was always a divisive figure who inspired admiration and respect by some; loathing and fear by others.

. . . . . . . . . . .

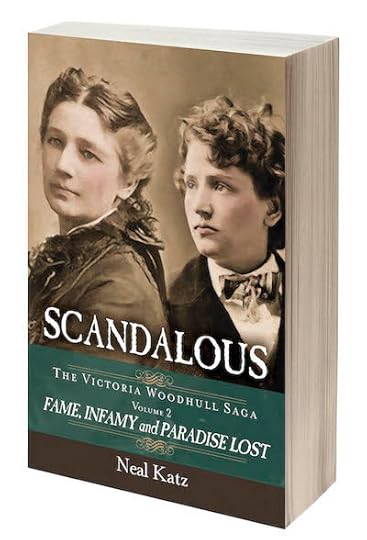

Books about Victoria Woodhull on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Clairvoyant sisters and a family of charlatans

From the time they were young, the sisters were the star attractions of the Claflin family’s traveling medicine and clairvoyance show, taking full advantage of the public hunger for magnetic healing, magical elixirs, and spirit channeling in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Victoria possessed a distinctive aquiline beauty and carried herself with a regal air. Tennessee’s wily intelligence was masked by a bubbly, coquettish demeanor and an uninhibited spirit.

Spiritualism was a powerful cultural force in the post-Civil War years, a time when those who lost loved once in the devastating conflict looked for ways to communicate with the dead. Victoria and Tennessee became skilled at convincing those who were grieving that they could do just that.

The sisters’ earnings became the main support of their unscrupulous parents, a pair of uneducated, conniving rubes, and their large brood of siblings.

Chased from one town to another, the eccentric Buck and Roxanna Claflin were purveyors of quackery and fraud, and the attractive daughters raised suspicions of selling sex along with their magical cures and messages from the dead.

A forced teenage marriage to a dissipated alcoholic

The truly dramatic portion of Victoria’s life began when she was in her late twenties. She and the family had temporarily settled in St. Louis after wandering from one Midwestern city to another dispensing their snake oil and doing spiritual readings.

The family, minus a few siblings who had grown and broken away, now included Canning Woodhull, a dissipated alcoholic and failed doctor. Victoria’s parents had married her off to Woodhull when she was barely fifteen.

Though she was repulsed by him from the start, the couple managed to have two children — Byron, a boy of limited mental capacity, and Zula Maud, a daughter who was Victoria’s joy.

A life-changing second husband

At a meeting of the St. Louis Spiritualists Society, where she made an impromptu speech, Victoria caught the eye of Colonel James Blood.

A Civil War veteran and ostensibly an upstanding citizen, Blood harbored radical views on social issues for the time, including those on sexuality and women’s rights. He helped give voice and order to Victoria and Tennie’s vague notions and helped shape their predilection for controversial causes.

After divorcing Woodhull and taking Blood for her husband, Victoria led her family to New York City in 1868, following a directive from Demosthenes, her longtime spirit guide. Demosthenes even conveyed to Victoria the exact address of the building on Great Jones Street where the family was to take residency, or so she claimed.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Becoming the “lady stockbrokers”

Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt, the railroad magnate (and one of the 19th century’s “robber barons”) was at the time in his twilight years and considered the richest man in America.

He scorned clergymen and physicians, instead taking comfort from spiritual mediums and healers of all sorts. The sisters wasted no time in making their way into his life once they became aware of his predilections.

Victoria brought Vanderbilt messages from his favorite son, who had died in the Civil War, and Tennie eased his pains with her healing hands. Soon she attended to Vanderbilt’s other physical needs by becoming his mistress. Vanderbilt may have chosen Tennie for his bedmate, but he admired Victoria’s intelligence.

Victoria took heed of Vanderbilt’s stock market tips and made a tidy sum in the aftermath of the 1869 Black Friday collapse of the gold market. Acquiring a taste for finance, Victoria and Tennie prevailed upon Vanderbilt to back them as they opened their own Wall Street brokerage firm.

Causing a sensation as “the lady brokers,” the sisters were the first American women to enter into the profession.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

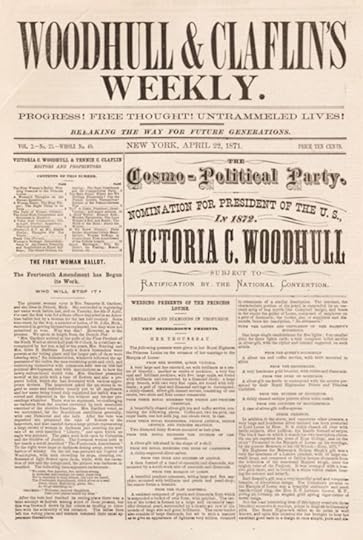

Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly; a presidential run

With the behind-the-scenes assistance of Blood as well as the radical intellectual Stephen Pearl Andrews, the sisters’ newfound wealth gave them the means to launch Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly.

It was a lively newsprint journal that served as a platform for their views on social issues, women’s rights (including ownership of their own bodies), marriage and divorce, and sexual freedom. It was particularly concerned with exposing political and moral hypocrisy.

The first issue also announced Victoria’s candidacy for president of the United States, another first for American women. This was radical indeed, given that women would not be granted the right to vote until some fifty years later. And never mind that she was also a bit under the constitutional age to become president.

Victoria named as her running mate Frederick Douglass. The famed African-American abolitionist and orator never agreed to the nomination, and never campaigned with her.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

A minister’s seductions — the Henry Ward Beecher scandal

Victoria’s nascent friendship with Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and other women’s movement leaders made her privy to a secret: Henry Ward Beecher, the beloved and nationally famed minister of Brooklyn’s Plymouth Church, had seduced Elizabeth Tilton, the wife of his best friend, Theodore Tilton.

Spreading among Victoria’s influential circle of contemporaries were whispers that the affair was but one in a long series of seductions by Beecher of married women in his parish.

Far from being shocked, Victoria viewed Beecher as a man who secretly practiced the sexual freedom that she openly preached. For some time, she explored a way to expose his hypocrisy that would be to her benefit.

In the midst of an intensive and lengthy cover-up, Theodore Tilton became the surprising emissary sent to placate Victoria. Elizabeth’s moody and obsessive wronged husband instead fell victim to Victoria’s charms, resulting in a brief, passionate affair.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Victoria speaking before the House Judiciary Committee along with a group of suffragists on January 11, 1871

. . . . . . . . . . .

Ascending in the women’s rights movement

Upon presenting an argument before the House Judiciary Committee in the nation’s capital for women’s right to vote under the protection of the 14th amendment, Victoria was embraced as a leader for the cause by the National Women Suffrage Association.

Yet Victoria’s alliance with the suffrage movement was always uneasy. She was too untethered and eccentric for the ladies, who were, for the most part, prim and proper. And, as history would later show, rather racist.

Though increasingly spurned by the members of the women’s rights movement, Victoria’s most loyal friends invited her to participate in the winter National Woman Suffrage Association convention.

There, she rallied the women to form their own political party, at the top of which was her own bid for the presidency of the United States. This would be, she proclaimed, a way to gain attention for the cause of suffrage.

At the May 1871 speech to the Woman’s Suffrage Convention, Victoria gave what would become one of her most famous speeches, “A Lecture on Constitutional Equality,” now known as “The Great Secession Speech.” In part, she said:

“If Congress refuses to listen to and grant what women ask, there is but one course left then to pursue. Women have no government. Men have organized a government, and they maintain it to the utter exclusion of women….

Under such glaring inconsistencies, such unwarrantable tyranny, such unscrupulous despotism, what is there left for women to do but to become the mothers of the future government?

There is one alternative left, and we have resolved on that. This convention is for the purpose of this declaration. As surely as one year passes from this day, and this right is not fully, frankly and unequivocally considered, we shall proceed to call another convention expressly to frame a new constitution and to erect a new government, complete in all its parts and to take measures to maintain it as effectually as men do theirs.

We mean treason; we mean secession, and on a thousand times grander scale than was that of the south. We are plotting revolution; we will overslough this bogus republic and plant a government of righteousness in its stead, which shall not only profess to derive its power from consent of the governed, but shall do so in reality.”

No one could deny Victoria’s power to stir up a crowd like very few others, male or female, could. Her speeches, with their drama and hints of scandal, were extremely popular and often drew thousands.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Depicting Victoria, “Get thee behind me, (Mrs.) Satan!” was a well-known 1872 cartoon by Thomas Nast

. . . . . . . . . . .

Exposing the Beecher-Tilton affair

As Victoria became more of a public figure, she was reviled for her views, especially when it came to free love. This was the Victorian era, during which the ideal of womanhood was to be “the angel in the house.” In the public eye, Victoria was Mrs. Satan — the polar opposite of an angel.

Pushed to her limits by a double standard that was destroying her reputation, Victoria seethed as she observed her critics thriving. The public taunts by none other than Beecher’s sisters, Catherine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe proved to be the last straw.

Victoria exposed the Beecher-Tilton affair, first in a speech, then in the Weekly, declaring that she refused to be made a martyr for her views.

Theodore Tilton, independent of Victoria’s actions, had pressed charges against Beecher for “criminal seduction,” culminating in what was to become the most sensational trial of the nineteenth century, one that was a national obsession for months.

In prison on election day

Anthony Comstock, a self-righteous battler against all that he deemed immoral, took a copy of the scandal issue of The Weekly to the Federal authorities. He had proof that it had been sent through the mails, and sending obscenity through the mails was a Federal offense.

Victoria and Tennie had just left the office of the Weekly with a fresh bundle of papers and were riding home in a carriage when U.S. Marshalls stopped them with a warrant for their arrest. The sisters were taken to Circuit Court and questioned.

On Election Day, presidential candidate Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee were held the Ludlow Street jail.

The plight of Victoria and Tennie on such obviously trumped-up charges brought them a new wave of sympathizers and supporters. Their jail cell was crowded with visitors and there was no lack of gentlemen willing to pay their court costs and attorneys fees.

Days later, Victoria and Tennie appeared before a Grand Jury in a packed courthouse. The newspapers howled at the blatant invasion of freedom of the press.

The brief boost to the Weekly’s circulation was a temporary salve for its declining fortunes, but her ordeals left Victoria exhausted and dispirited. Abandoned by even her staunchest allies and friends, Victoria’s frustration and anguish drove her to divorce Blood.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Losing Cornelius Vanderbilt’s support

Victoria’s reputation as an orator, businesswoman, muckraking journalist, and advocate for women’s suffrage grew, even as the advice and moral and financial support of Cornelius Vanderbilt was waning.

His new, younger wife, plucked from the cream of society, was a more appropriate choice for him than Tennie Claflin, in the estimation of the elderly Commodore’s grown sons and daughters.

Vanderbilt’s new bride lured him back to traditional religion and proper medical doctors. Vanderbilt’s abrupt withdrawal from their lives was compounded by the depressed economy following another market crash.

A downward spiral for the Woodhull and Claflin clan

The national mood seemed to be swinging back to more conservative views. The radical stances espoused by Victoria and Tennessee experienced profound pushback, and they themselves felt increasingly ostracized and marginalized.

The Woodhull and Claflin clan were forced to give up their 38th St. mansion. They fought to keep the Weekly alive at all costs, but it soon grew impossible to do so.

Victoria embarked on a grueling lecture tour to support the publication and the family. By this time, she had taken in her first husband, Canning Woodhull, now addicted to morphine as well as alcohol. Outraged society charged Victoria with “living with two husbands.”

The sisters’ fortunes were quicly waned and their brokerage slipped into debt. Victoria was suffering from nervous exhaustion, and the future was bleak.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

A disputed will saves the day

When all hope seemed lost and the Woodhull and Claflin clan was clearly in crisis mode, the Vanderbilt fortune returned in the form of a disputed will. The old Commodore, having just died, left nearly his entire fortune to his son William in hopes of keeping his railroad empire intact.

His remaining children, outraged by their token bequests, went to court to contest the will, charging that their father had been of unsound mind when he had last updated it. Portraying him as a nutcase unduly influenced by bogus healers and spirit mediums, they devised a plan to call Victoria and Tennessee as witnesses.

This threat propelled William to quick action. Noting the financial distress of the Claflin family, he offered to pay the sisters off with a tidy sum if they’d leave the country before they could be called to the witness stand.

Victoria and Tennessee haggled with William, getting him to agree to an amount that was a small fortune for any ordinary American family not in the league of the Vanderbilts.

Finding refuge in England

Victoria and her children, Tennie, and Buck and Roxana Claflin were suddenly comfortable again thanks to the Vanderbilt payoff, and boarded a ship bound for England.

When Victoria set sail with her two children, with Tennessee and their parents still in tow, she vowed to return as soon as she could to resume her fight for her beliefs, and to vindicate herself against those who had tried to destroy her.

After having been mired in controversy for nearly all their lives, the sisters now craved respectability. Victoria captured the fancy of a wealthy young banker, John Biddulph Martin, while lecturing to a curious British audience. Eventually, over the objections of his family, the two were married.

Tennessee married an even more fabulously wealthy baronet. The sisters fought as hard to gain social standing as they had previously done to earn notoriety.

Unable to completely rest on their laurels, the sisters continued to promote for favored causes, though in a much quieter manner.

The sisters remained in England for the rest of their lives, enjoying a relatively peaceful existence and doing good works, careful to steer clear of controversy — at least, most of the time.

Victoria Woodhull died on June 9, 1927 at Norton Park in Bredon’s Norton, Worcestershire, England.

Victoria Woodhull’s complicated legacy

Though many of Victoria’s views on social issues and women’s rights were quite progressive, her stances on other issues were surprisingly regressive.

Despite her belief that women should have domain over their own bodies, she was virulently anti-abortion. She also ascribed to eugenics and supported forced sterilization of those she deemed unfit to breed.

Though she had chosen Frederick Douglass, an African-American, as her unwitting running mate, there’s also evidence that she, like a number of other white suffragists of her time, was racist.

Victoria was recognized as a powerful extemporaneous speaker, though scholars almost uniformly believe that her writings and more polished speeches were heavily edited by her second husband, James Blood, and fellow radical Stephen Pearl Andrews. This no doubt is due to her lack of formal education.

Yet despite her muddled legacy and lifetime of being embroiled in controversy and scandal, Victoria Woodhull is recognized as a fearless advocate for women’s freedom and for the bold statement of running for president at a time when women didn’t even have the right to vote.

Here are just a few ways that Victoria has been recognized over the years:

A historical marker was erected outside the Homer Public Library in Licking County, Ohio (where the Claflin clan resided for some years. It honors Victoria as the “First Woman Candidate For President of the United States.”

1980: The Broadway musical Onward Victoria was inspired by her life. It wasn’t very well received, but still …

2001: Victoria Woodhull was belatedly inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame .

2003: The Woodhull Freedom Foundation is an advocacy organization for sexual freedom in a human rights context.

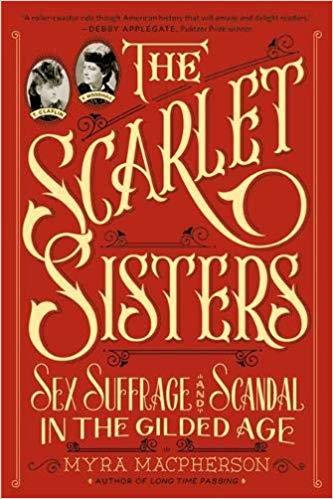

There have been numerous full-scale biographies of Victoria in recent years, including Other Powers by Barbara Goldsmith, Notorious Victoria by Mary Gabriel, The Scarlett Sisters by Myra Macpherson, and others.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Victoria Woodhull

Wikipedia

The Strange Tale of the First American Woman to Run for President (Politico)

9 Things You Should Know About Victoria Woodhull

Biography of Victoria Woodhull by Theodore Tilton (1871)

Selected Writings of Victoria Woodhull

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Victoria Woodhull: Rabble Rousing Suffragist and First American Woman to Run for President appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 24, 2020

Fanny Burney

Fanny Burney (June 13, 1752 – January 6, 1840), born Frances Burney, was a British novelist, diarist, and playwright best remembered for her first novel, Evelina (1778).

Born in Lynn Regis, now known as King’s Lynn, her father, Dr. Charles Burney, was a musician of note. Her mother, Esther Sleepe Burney, died when Fanny was ten, and this marked the time when she began writing in earnest.

Fanny’s literary output included four novels eight plays, a biography, and some twenty-five volumes of journals and letters. She was an influence on novelists of manner and satire who came a bit later, notably, Jane Austen and William Makepeace Thackeray.

Themes and literary reputation

Fanny’s fictional work touched on the lives of the English aristocracy, subtly (and sometimes not so subtly) satirizing their pretensions. She also delved into issues of women’s place in society.

Evelina and Cecelia were especially popular in their time, but her plays were not performed. Her father feared that his daughter’s reputation would be damaged. The one play that was performed wasn’t well-received, and closed after one performance.

It was considered scandalous for a woman to write and publish, and the fact that Fanny was admired rather than reviled for being a novelist was an exception.

Fanny Burney’s reputation as a novelist declined after her death. Critics and biographers gravitated to her posthumous diaries as a more fascinating source on life in the eighteenth century, though in Fanny’s case, a privileged one.

Contemporary scholars have taken a renewed interest in her work, especially when it addresses the issues and struggles in the lives of women, and as a critique of social mores of the time.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Austin Dobson’s View of Fanny Burney’s life and work

The following brief biography of Fanny Burney’s life and work was published in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 2, 1904, contributed to that publication by Austin Dobson upon the publication of an edition he edited titled The Diary and Letters of Madame D’Arblay (Fanny Burney’s eventual married title). It’s presented here with minor edits, though leaving the rather old-fashioned language intact.

Fanny Burney, an Eighteenth-Century Novelist Whose Work is Almost Forgotten Today

It’s doubtful if many readers today, even those who consider themselves fairly well versed in the history of British literature, could name offhand the author of Evelina. And yet in her day, Fanny Burney was one of the distinguished names in literary England, considered one of the brilliant novelists of the period.

Frances Burney was the daughter of a well-known musician and composer of the middle period of the eighteenth century, a man who was widely known and who held a prominent place in the musical world of the time. Charles Burney was the son of a portrait painter. The artistic strain showed itself in Charles’ taste for music.

His career was successful, and he even wrote a History of Music which was well received. It’s apparent, then, that Fanny had a literary and artistic background for her own development.

Fanny was born at King’s Lynn, where her father lived, engaged in his profession. In 1760 Burney removed to London, where his wife died shortly after. A good portion of Fanny’s girlhood was passed under the care of a stepmother, who seems to have done her whole duty by her.

Charles Burney was intimate with the artistic and literary circles of the capital; his children were reared in an atmosphere of culture and good taste. Fanny has been described as a demure and reserved little person, but full of humor and life when in the comfort of the domestic circle.

Becoming a diarist, growing into young womanhood

When Fanny was twelve, she began the keeping of a diary, which she prefaced with a whimsical introduction, “Addressed to a Certain Nobody.”

This record, to which she confided her innermost thoughts and opinions, her preferences and likings, her accounts and characterizations of the people she met, as well as her daily personal and family history, was kept up for years.

Aside from its quaint comments and self-revealing qualities, the diary is interesting in showing something of the young woman’s intellectual life, training, and aspirations. That she was an omnivorous reader of the literature of the time is apparent from the list of books she records.

She wrote of going to see Oliver Goldsmith’s new play, She Stoops to Conquer, in 1773 and describes it as “laughable and comic” but says that all diversions are insipid to her except the opera.

As she came into young womanhood she was busily engaged as her father’s secretary in assisting him in the preparation of his History of Music, a work that engaged his attention for several years, and which was regarded at the time as an important work. Fanny’s diary, which was steadily kept up, is especially interesting for the glimpses it gives of the literary celebrities of the time.

During her girlhood days, and because of her passion for writing, Fanny Burney had written a complete work of fiction which she had titled The History of Caroline Evelyn. But she burned the manuscript later and all that’s known about it is what she herself told.

A secret first novel

Just when she began working on Evelina, her first and greatest novel, is not clear from the record, but evidently, she had been at work on it for some time prior to 1776 when she first began to think of publishing. For fear that her handwriting might be recognized, she copied it out in a feigned hand.

It was written as an epistolary novel, that is, in the form of letters, a style that was popular at the time. Fanny’s only confidants were her sister and her eldest brother, James. The publisher was not aware of the identity of the author and his letters were directed to a “Mr. Grafton.” James posed as the book’s author.

The novel finally appeared in 1778, a period when, according to the literary critic Mr. Dobson, English fiction seemed to be suffering from “a kind of sleeping sickness.” A level of mediocrity prevailed in fiction writing.

The great masters who had followed Samuel Richardson’s success with Pamela (1740) were gone — as was Richardson himself. Henry Fielding, whose last novel, Amelia, appeared in 1751, was still read, and both Laurence Stern’s Tristram Shandy and The Vicar of Wakefield had been a considerable time before the public.

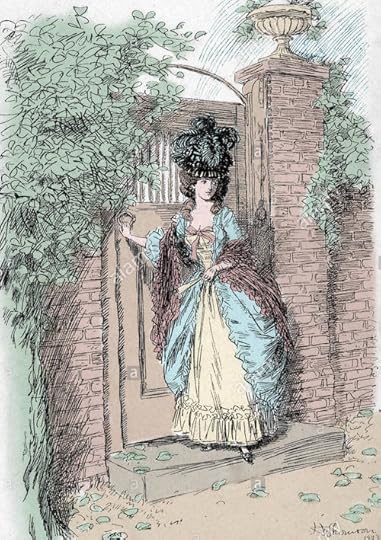

. . . . . . . . .

Illustration by Hugh Thompson from a later edition of Evelina

. . . . . . . . .

The author’s true identity emerges

Evelina: Or, The History of a Young Lady’s Entrance into the World came forth, almost unheralded, in the early part of 1778. The secret of authorship was well kept, the book made steady progress, and in two or three months, it began to gain serious attention.

It wasn’t until June of that year that Dr. Burney, the author’s father, read the book. He had read reviews of it without realizing that the author was his daughter. For a woman, and one so young, at that, to publish a novel was quite a radical act, and Fanny feared her beloved father’s reaction.

However, he was impressed with the novel and pleased by the favorable reactions to it by the public and critics, once he realized that it was by his daughter. He was happy for the recognition and praise that Fanny was receiving.

Fanny’s joy was complete when Dr. (Samuel) Johnson gave it the stamp of his hearty approval. She received from the publisher thirty pounds sterling for the novel. Its success made her an esteemed figure in London literary society.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

A second novel — Cecelia

In 1782, she published her second novel, Cecelia, or the Memoirs of an Heiress, and received 250 pounds for the copyright.

The story of a beautiful, smart young woman, Cecelia Beverly, the novel presents a marriage plot, albeit a somewhat unusual one. The book was well-received, though some critics thought it was a bit weighed down by the author’s awareness that she was writing for an audience — not just for herself as she had done with Evelina.

At thirty years of age, Fanny had, with two published novels, achieved a measure of success as a novelist that attracted the attention of Queen Caroline and King George III. They brought her into the court with an appointment in the royal household as “dresser” to the queen from 1786 to 1790.

The post interfered with her literary work, and after Cecelia, she wrote little that had an element of permanency about it.

It was at the end of 1792 that she met Alexandre D’Arbley, a French artillery officer and refugee, whom she married. The union was a happy one, and after the end of the French Revolution, she lived with her husband in France until the downfall of Napoleon. They had one son, Alexander, born in 1794.

. . . . . . . . .

Frances d’Arblay (Fanny Burney) by Edward Francisco Burney

. . . . . . . . .

Later years

Remarkably, Fanny had a mastectomy in 1810 — without anesthesia. She created the first detailed account of this type of operation, having been awake for its entirety. It hasn’t been established whether she had breast cancer or some other sort of disease of the breast tissue.

Along with her husband and son, she returned to England and lived in Bath until General D’Arbley died there in 1818.

Fanny’s last novel, The Wanderer (1814) was a work of incisive social criticism, but it wasn’t met with enthusiasm by her reading public, and wasn’t reprinted after its first edition. Fanny published Memoirs of Charles Burney in three volumes in 1832. She had remained close with her father until his death.

At one point, she moved to London to be closer to her son while he studied at University. Alexandre, who died in 1837, predeceased her. Fanny Burney died in Bath in 1840; she, her husband, and son are buried in a family plot.

. . . . . . . . . .

Fanny Burney page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Fanny Burney’s legacy

Fanny Burney’s novels included Evelina, Cecelia, Camilla, and The Wanderer. In addition, she wrote eight dramatic pieces, a tragedy and a comedy, all of which have been forgotten. Her Diaries and Letters was published about two years after her death.

It is often accepted that Fanny Burney’s legacy as a novelist rest on Evelina and Cecelia. A critic of note wrote that he doubts “if the piety of the enthusiast could ever revive — or rather, create — the slightest interest in The Wanderer, or that any but the fanatics of the out-of-date, or the student of manners, could struggle through Camilla.

Evelina marked a definite deviation in the progress of the English national fiction. Leaving Fielding’s breezy and bustling highway, leaving the analytical hothouse of Richardson, it carries the novel of manners into domestic life, and prepare the way for Maria Edgeworth and the exquisite parlor pieces of Jane Austen.

More about Fanny Burney

Novels

Evelina: Or The History of A Young Lady’s Entrance into the World ( 1778)

Cecilia: Or, Memoirs of an Heiress (1782)

Camilla: Or, A Picture of Youth (1796, revised 1802)

The Wanderer: Or, Female Difficulties (1814)

Journals and letters (selected editions)

The Early Diary of Frances Burney 1768–1778 (1889)

The Diary and Letters of Madame D’Arblay, Austin Dobson, ed. (1904)

The Diary of Fanny Burney, Lewis Gibbs, ed. (1971)

Dr. Johnson & Fanny Burney, Chauncy Brewster Tinker, ed. (1912)

The Early Journals and Letters of Fanny Burney, 1768–1786

The Court Journals and Letters of Frances Burney

The Journals and Letters of Fanny Burney (Madame D’Arblay) 1791–1840

Plays

The Witlings (1779)

Edwy and Elgiva (1790)

Hubert de Vere (1791)

The Siege of Pevensey (1791)

Elberta (1791)

Love and Fashion (1799)

The Woman Hater, (1801)

A Busy Day (1801)

Biography

Fanny Burney: A Biography by Claire Harman (2001)

More information and sources

British Library

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Fanny Burney’s books on Goodreads

Burney Society at McGill University

Read and listen online

Audio recordings on Librivox

Fanny Burney’s works on Project Gutenberg

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Fanny Burney appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 20, 2020

A Girl of the Limberlost by Gene Stratton-Porter (1909)

A Girl of the Limberlost by Gene Stratton-Porter (1863 – 1924) was the author’s third novel, published in 1909 as a sequel to Freckles (1905), both of which are stories for “children of all ages.”

Gene was enchanted by the great outdoors from an early age, and was encouraged by her parents to explore her surroundings. Her love of nature served as the foundation for her career as a naturalist, photographer, and writer.

In the course of her early explorations, Gene came upon the Limberlost Swamp near her home in rural Indiana. There she discovered birds, butterflies, and wildflowers that captured her imagination.

Though she did eventually marry and have a daughter, Gene disdained the domestic life that was expected of young women of her time. She was determined to enjoy a life of creativity and exploration as a way of expressing her love for the natural world.

. . . . . . . . . .

The 1945 film was one of several film adaptations

. . . . . . . . . .

Many of Gene’s novels were adapted to film, especially in the 1920s. She even founded a production company, Gene Stratton-Porter Productions, to produce silent films based on her novels, and even directed some of them.

Another film iteration of The Girl of the Limberlost came out in 1945, and the most recent adaptation of A Girl of the Limberlost was released in 1990.

Much of Gene Stratton-Porter’s work has been forgotten, but Freckles and A Girl of the Limberlost have stood the test of time among her many books.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Gene Stratton-Porter

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1909 review of A Girl of the Limberlost

From the original review of A Girl of the Limberlost by Gene Stratton-Porter in the Stockton Daily Evening Record, August 21, 1909:

Here’s a sweet and tender tale which is a welcome addition to the libraries of our young people, as well as delightful reading for older ones. It is a sympathetic story with the ennobling love of nature as its basic thought.

None but the keenest lover of bird and insect life could have written so vividly of the birds and butterflies, and made the Limberlost come so alive with their songs and flutterings.

While the development of the plot seems strained in places, the action too rapid, and some of the situations too dramatic to be artistic, it’s not altogether for these qualities that the book is read.

Rather, it’s for the unfolding of Elnora Comstock’s tender, sympathetic, strong, and gentle character. And for the part in her character in which the woods and the wild creatures play that we follow with intense interest to the very end.

Wherever the author drops into her intimate descriptions of the life of the forest the book has a beauty all its own, and there must be some who read it that will be enticed into experimenting for themselves to see how much truth lies in the thought that nature holds more of value for us than manmade creations.

In Elnora Comstock, Gene Stratton-Porter has pictured A Girl of the Limberlost as almost too exquisite a creature, and yet she compels an affectionate admiration that makes the reader forget the incongruities.

Perhaps the truest picture of her is that which shows her as a lonely, sensitive child setting out for the first awful day at the City High School, and the resulting pain and confusion of contact with the crowding, jostling, scornful pupils who could see only the external signs of a life foreign to their own: One which was to show them, however, the depth and breadth of character that nature bestows on those who truly love it.

The only way to forgive the attitude of the girl’s mother, Katherine Comstock, toward her only child, is that she is, at least, partially insane and thus worthy of pity. Wholly lovable are the characters of Aunt Margaret and Uncle Wesley Sinton, whose care and watchfulness save Elnora, whom they adore, from many a painful experience.

The love story woven into the last chapters weakens the beauty of the first half of the book, and yet has in it much to stimulate thought. The author presents the reader with the contrasting personalities of A Girl of the Limberlost and Edith Carr, society leader, who is wealthy and magnificently beautiful.

The book will be welcome to all who enjoyed Freckles, for he and the “Swamp Angel” appear again in these pages, as lovable and interesting as ever.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Girl of the Limberlost on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from A Girl of the Limberlost

“To me, it seems the only pleasure in this world worth having is the joy we derive from living for those we love, and those we can help.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I believe the best way to get an answer to prayer is to work for it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The Limberlost is life. Here it is a carefully kept park. You motor, sail and golf, all so secure and fine. But what I like is the excitement of choosing a path carefully, in the fear that the quagmire may reach out and suck me down; I even enjoy seeing an old canny vulture eyeing me as if it were saying, ‘ware the sting of the rattler, lest I pick your bones as I did old Limber’s. I like sufficient danger to put an edge on things. This is all so tame.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“What you are lies with you. If you are lazy, and accept your lot, you may live in it. If you are willing to work, you can write your name anywhere you choose, among the only ones who live beyond the grave in this world, the people who write books that help, make exquisite music, carve statues, paint pictures, and work for others. Never mind the calico dress, and the coarse shoes.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The world is full of happy people, but no one ever hears of them. You must fight and make a scandal to get into the papers. No one knows about all the happy people. I am happy myself, and look how perfectly inconspicuous I am.”

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post A Girl of the Limberlost by Gene Stratton-Porter (1909) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

The Girl of the Limberlost by Gene Stratton-Porter (1909)

The Girl of the Limberlost by Gene Stratton-Porter (1863 – 1924) was the author’s third novel, published in 1909 as a sequel to Freckles (1905), both of which are stories for “children of all ages.”

Gene was enchanted by the great outdoors from an early age, and was encouraged by her parents to explore her surroundings. Her love of nature served as the foundation for her career as a naturalist, photographer, and writer.

In the course of her early explorations, Gene came upon the Limberlost Swamp near her home in rural Indiana. There she discovered birds, butterflies, and wildflowers that captured her imagination.

Though she did eventually marry and have a daughter, Gene disdained the domestic life that was expected of young women of her time. She was determined to enjoy a life of creativity and exploration as a way of expressing her love for the natural world.

. . . . . . . . . .

The 1945 film was one of several film adaptations

. . . . . . . . . .

Many of Gene’s novels were adapted to film, especially in the 1920s. She even founded a production company, Gene Stratton-Porter Productions, to produce silent films based on her novels, and even directed some of them.

Another film iteration of The Girl of the Limberlost came out in 1945, and the most recent adaptation of A Girl of the Limberlost was released in 1990.

Much of Gene Stratton-Porter’s work has been forgotten, but Freckles and The Girl of the Limberlost have stood the test of time among her many books.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Gene Stratton-Porter

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1909 review of The Girl of the Limberlost

From the original review of The Girl of the Limberlost by Gene Stratton-Porter in the Stockton Daily Evening Record, August 21, 1909:

Here’s a sweet and tender tale which is a welcome addition to the libraries of our young people, as well as delightful reading for older ones. It is a sympathetic story with the ennobling love of nature as its basic thought.

None but the keenest lover of bird and insect life could have written so vividly of the birds and butterflies, and made the Limberlost come so alive with their songs and flutterings.

While the development of the plot seems strained in places, the action too rapid, and some of the situations too dramatic to be artistic, it’s not altogether for these qualities that the book is read.

Rather, it’s for the unfolding of Elnora Comstock’s tender, sympathetic, strong, and gentle character. And for the part in her character in which the woods and the wild creatures play that we follow with intense interest to the very end.

Wherever the author drops into her intimate descriptions of the life of the forest the book has a beauty all its own, and there must be some who read it that will be enticed into experimenting for themselves to see how much truth lies in the thought that nature holds more of value for us than manmade creations.

In Elnora Comstock, Gene Stratton-Porter has pictured The Girl of the Limberlost as almost too exquisite a creature, and yet she compels an affectionate admiration that makes the reader forget the incongruities.

Perhaps the truest picture of her is that which shows her as a lonely, sensitive child setting out for the first awful day at the City High School, and the resulting pain and confusion of contact with the crowding, jostling, scornful pupils who could see only the external signs of a life foreign to their own: One which was to show them, however, the depth and breadth of character that nature bestows on those who truly love it.

The only way to forgive the attitude of the girl’s mother, Katherine Comstock, toward her only child, is that she is, at least, partially insane and thus worthy of pity. Wholly lovable are the characters of Aunt Margaret and Uncle Wesley Sinton, whose care and watchfulness save Elnora, whom they adore, from many a painful experience.

The love story woven into the last chapters weakens the beauty of the first half of the book, and yet has in it much to stimulate thought. The author presents the reader with the contrasting personalities of The Girl of the Limberlost and Edith Carr, society leader, who is wealthy and magnificently beautiful.

The book will be welcome to all who enjoyed Freckles, for he and the “Swamp Angel” appear again in these pages, as lovable and interesting as ever.

. . . . . . . . . .

Girl of the Limberlost on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from The Girl of Limberlost

“To me, it seems the only pleasure in this world worth having is the joy we derive from living for those we love, and those we can help.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I believe the best way to get an answer to prayer is to work for it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The Limberlost is life. Here it is a carefully kept park. You motor, sail and golf, all so secure and fine. But what I like is the excitement of choosing a path carefully, in the fear that the quagmire may reach out and suck me down; I even enjoy seeing an old canny vulture eyeing me as if it were saying, ‘ware the sting of the rattler, lest I pick your bones as I did old Limber’s. I like sufficient danger to put an edge on things. This is all so tame.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“What you are lies with you. If you are lazy, and accept your lot, you may live in it. If you are willing to work, you can write your name anywhere you choose, among the only ones who live beyond the grave in this world, the people who write books that help, make exquisite music, carve statues, paint pictures, and work for others. Never mind the calico dress, and the coarse shoes.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The world is full of happy people, but no one ever hears of them. You must fight and make a scandal to get into the papers. No one knows about all the happy people. I am happy myself, and look how perfectly inconspicuous I am.”

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Girl of the Limberlost by Gene Stratton-Porter (1909) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 17, 2020

The Ghetto by Lola Ridge, Radical Poet