Nava Atlas's Blog, page 92

February 22, 2018

10 Fascinating Facts About Maya Angelou

Maya Angelou (1928 – 2014) was an American author, actress, screenwriter, dancer, poet and civil rights activist. Best known for her 1969 memoir, I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings, the inspiring, trail-blazing African-American woman led a vibrant life, full of accomplishments. While she may be remembered for numerous speeches, plays, memoirs, and performances, here are ten fascinating facts about Maya Angelou that give even more insight into her multifaceted life:

Childhood years spent mute

Angelou has publicly spoken about the trauma that resulted in her going mute for five years, but there is so much to be discussed about these crucial years. After being raped by her mother’s boyfriend at the age of seven, the abuser was only jailed for one day. After telling her family about the horrific incident, a day after his release he was murdered. Angelou believed this to be her fault for opening her mouth and said “I thought my voice killed him; I killed that man because I told his name. And then I thought I would never speak again because my voice would kill anyone…” Angelou also credits her brother to be one of the people to bring her out of this time of muteness.

Inspiring grandmother

When Angelou was 3 years old, she and her older brother, Bailey Jr., were sent to Stamps, Arkansas to live with her paternal grandmother. Her grandmother, Annie Henderson (whom Angelou referred to as “momma”) was a child to a former slave, and the only black person in Stamps to own a general store in town.

Her grandmother is also with whom Angelou credits her ability to read; Annie Henderson would bring back books from the local all-white schools, and taught Angelou and her brother how to read.

First black female streetcar conductor

There doesn’t seem to be a hat she hasn’t worn. When Angelou was in high school, she sought out a job as a streetcar conductor. After initially being denied several times based on the color of her skin, her perseverance won in the end. She became the first black streetcar conductor, female no less. “I loved the uniforms,” Angelou said.

Female pimp and prostitute

Angelou was always forthcoming and open about sexuality and her personal history with sex work. She spoke about it in interviews (but publications often omitted it later) and wrote about it in her second autobiography, Gather Together In My Name.

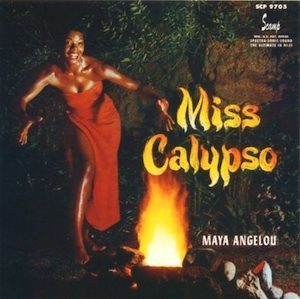

Although short-lived, she made a bundle. After working as a dancer at the Hi Hat Club in San Diego, going by the working name Ms. Calypso, she turned to pimping and soon quit after three months– but only after she bought her first car, a 1939 pale-green Chrysler convertible.

Her friend Martin Luther King, Jr. died on her birthday

Angelou had a multitude of prominent friendships over the course of her life, including Malcolm X and Oprah. She had a close friendship with Martin Luther King Jr. When Angelou returned to the United States after having spent time living abroad, she was about to help organize a march for Martin Luther King Jr., but on her 40th birthday, April 4th, 1968, he was assassinated.

Grammy winner

Angelou won three Grammys in her lifetime: the first one was for a poem she wrote and recited at President Bill Clinton’s inauguration in 1993. She was the first black poet to present at a presidential inauguration. It was called “On The Pulse of Morning” and won the Best Spoken Word award. She continued on to win two more, in 1996 for Best Spoken Word Album, and again in 2003.

Received a letter from Tupac’s mother

Angelou agreed to be a part of John Singleton’s iconic 1993 film “Poetic Justice” featuring rapper Tupac Shakur and singer Janet Jackson. The rapper was in the middle of a raging cursing spree, and although having no idea who he was, Angelou promptly pulled him aside and had a heart-to-heart with the artist. It’s been said that she moved him to tears with her empowering story about black individuals in America, and of his importance to the culture.

Tupac’s mother, Afeni Shakur, later wrote a letter to Angelou expressing her deepest gratitude towards Angelou for giving advice to her son and teaching him such a valuable lesson.

You might also enjoy: Maya Angelou Quotes To Live By

Writer of Hallmark greeting cards

Despite the disapproval of her Random House editor, Angelou wrote words for a line of cards, bookends, and pillows for Hallmark. She said “If I’m America’s poet, or one of them, then I want to be in people’s hands… people who would never buy a book.”

Cookbook author

If you couldn’t tell by now, Angelou always kept busy. She authored the cookbooks Great Food, All Day Long and Hallelujah! The Welcome Table. She believed that people wouldn’t overeat if they ate what they wanted, when they felt like it … such as “fried rice for breakfast,” she said.

Maya Angelou was also…

A guest star on Sesame Street, watched Law & Order, loved Uggs, and listened to country music.

Was there anything she didn’t do?

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 10 Fascinating Facts About Maya Angelou appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 21, 2018

“Flowering Judas” by Katherine Anne Porter: an analysis

Taking a cue from Judas who revealed Christ’s identity to his persecutors with a kiss, “Flowering Judas” by Katherine Anne Porter, a short story published in 1930, revolves around themes of betrayal. Laura, an adventurous young woman from the southwest U.S. has an identity crisis, questioning her own values and her involvement in the Mexican revolution of 1910 – 1920. At age twenty-two, she resembles Katherine Anne Porter herself, who traveled often to Mexico in her thirties, after the war ended.

Characteristic of Porter’s heroines, Laura is one for whom personal choices have serious political implications. Despite her distaste for the powerful leader Braggioni, she endures his oppressive, off-key serenades. Her inauthentic denial of self and her complicity in Eugenio’s death lead her to rethink her own status as savior or betrayer.

Laura’s self-betrayal

“It may be true,” she thinks, “I am as corrupt … as Braggioni.” Her way of living, she decides, betrays her sense of what life should be. Risking her safety for a dream of social justice, she notes flaws in an international enterprise that operates by means of deception and exploitation. The dreamy, highly abstracted conclusion of the story suggests no pat interpretation, but complicates Laura’s decision to involve herself in a faraway conflict and her denial of human connection: “She is not at home in the world.”

The gringa Laura is an unlikely player in the Mexican revolution. Her little betrayals of the Socialist cause seem fairly insignificant. She insists on handmade lace rather than products of the worshipped machine. A Roman Catholic convent graduate, like the author, she pauses now and then in a church to indulge her religious tendencies, also forbidden by the revolutionaries.

Laura’s real transgressions concern her betrayal of self, her rejection of “knowledge and kinship,” and the fact that she has lost a sense of wonder as she looks about her “without amazement.” As her illusions of heroic social transformation crumble, she understands: “it is monstrous to confuse love with revolution.”

Teaching children English in Xochimilco by day, smuggling secret messages and sleeping pills to prisoners by night, she appears brave and daring, yet exhibits fear in many forms. Rather than thrilling to the sustaining pulse of life about her, “she is gradually perfecting herself in the stoicism she strives to cultivate against that disaster she fears, though she cannot name it.”

The anxiety Laura lives by reveals the lack of faith she feels in her project and manifests itself most clearly in the nightmarish scene at the end of the story. The clear betrayal, when she fails to save or even connect with the martyred Eugenio, manifests her inability to live fully in the world, in the service of a genuine, human cause, including that of her own fulfillment.

RELATED POSTS

Katherine Anne Porter biography

6 Quick Writing Tips from Katherine Anne Porter

Katherine Anne Porter at Work

Forthright Quotes by Katherine Anne Porter

Ship of Fools

Laura’s hardening, Braggioni’s heartlessness

Laura has hardened herself in a way different from her employer Braggioni’s heartlessness. Sexually repressed in her long, tight sleeves and high collar, she is unmoved by suitors, and in Braggioni’s eyes, “notorious[ly]” virginal. Does she deny her womanhood or rather take measures necessary for one dealing in a “man’s world” of political intrigue? The appealing appearance of her body, “great round breasts” and “invaluably beautiful legs” under long skirts serve as a decoy for danger in a patriarchal system. True peril lies in her would-be suitors.

Nevertheless, her body itself strives to protect her, as Porter writes in the style of literary naturalism: “the very cells of her flesh reject knowledge and kinship in one monotonous word. No. No. No.” Her adaptation to and survival in these circumstances depends on such rejection of human connection, and her instincts direct her actions: “No repeats this firm unchanging voice of her blood.”

Braggioni, a powerful, flawed figurehead, leads the Socialist insurrection under Pascual Ortiz Rubio in his region of Mexico City. A complicated character, he seems a buffoon at times, a manipulator, an apocalyptic visionary, and an indiscriminate user of women. Empathetic yet deeply critical, Laura understands his sensitivity, the way his cruelty rests on “the vast cureless wound of his self-esteem.” His “gluttonous bulk” is a symbol of her disillusion, for she had mythologized a revolutionist as “lean, animated by heroic faith, a vessel of abstract virtues.”

Images of total destruction

Near the end of the story, Braggioni glorifies images of total destruction: “Some day this world, now seemingly composed and eternal, to the edges of every sea shall be merely a tangle of gaping trenches, of crashing walls and broken bodies. Everything must be torn from its accustomed place where it has rotted for centuries …” What has young Laura gotten herself into?

If Braggioni fails to fit the bill of a true revolutionist, so does Laura. The author plays up the surprising similarities between the young seeker and the coarse commander by drawing parallels between the two. Laura’s twenty identical hand-made lace collars, echoed pathetically in the dropped drawers of the priest figurine, also parallel Braggioni’s yellow silk handkerchief scented with Jockey Club cologne from New York.

Such affectations and indulgences seem out of place in a cause that proclaims freedom for the peasants and for political prisoners in tortuous conditions. Whereas Laura’s “knees cling together under sound blue serge,” Braggioni “balanc[es] his paunch between his spread knees.” Later, he lays his laden ammunition belt across Laura’s knees to solidify his dominance and their connection. The author’s subtle artistry and figurative patterning enables Laura’s self-knowledge as she declares herself “corrupt, callous… and incomplete” as Braggioni.

Katherine Anne Porter page on Amazon

The shattering of illusions

The illusions Laura had about joining a great revolutionary movement to better society prove false. Braggioni, the supposed great leader, is a gluttonous sham. His definition of freedom is a travesty of his wife’s trust. He confides to Laura, “One woman is really as good as another for me, in the dark. I prefer them all.”Laura strokes his ego because he provides her entrée into the inner workings of the movement.

“She cannot help feeling that she has been betrayed irreparably by the disunion between her way of living and her feeling of what life should be, and at times she is almost contented to rest in this sense of grievance as a private store of consolation.” Her temptation to trade feelings of self-pity for action proves dangerous, especially because many of the activities she does carry out seem hardly worthy of lofty ideals of political improvement. For example, she moves money between the Romanian and Polish agitators, both of whom are being shamelessly used by the Mayan-Italian Braggioni.

A false martyr

After a month’s abandonment, Braggioni returns lovingly to his oft-betrayed wife and she humbly washes his feet in the manner of Christ bathing his disciples. Despite his hard-hearted dismissal of Eugenio, he seems quite moved by the loss after all. So he is at once a brute symbol of violent revolution, and a more ironically rounded, human figure, a false martyr to balance the true sacrifice to despair, Eugenio.

In the final dream-scene, a skeletal Eugenio calls Laura a murderer, and beckons her to a new country, to death. Laura experiences a deeply sensual capitulation to the great feeling behind her paradoxically daring and timid revolutionary activity. Denied his guiding hand, Laura devours the lush blossoms of the Judas tree he feeds her. Her literal hunger and thirst signal further corruption rather than spiritual communion.

The physicality of her gesture, reminiscent of both Christian sacrament and Braggioni’s appalling gluttony, turns all into a false ritual, and again links her to her antagonist. In the presence of an un-resurrected Eugenio, Laura can no longer repress her human need for connection, nor her affective responses of wonder and compassion. Yet she remains confused, fragmented, and alienated, as she wakes trembling with a cry.

A beautifully crafted tale

Various critics report that this beautifully crafted tale that secured Porter’s literary reputation was written in a single evening of December, 1929. Porter typically started her stories by writing the final line first and this example pulls inexorably towards its surrealist end. The story’s conclusion provides an overflow of repressed emotion for both Braggioni and Laura.

— Contributed by Sarah Wyman, Associate Professor of English, SUNY-New Paltz, ©2018

More about “Flowering Judas” by Katherine Anne Porter

This Day in History: “Flowering Judas” is published

Untoward Stories: “Flowering Judas”

Reader discussion of Flowering Judas and Other Stories on Goodreads

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post “Flowering Judas” by Katherine Anne Porter: an analysis appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

February 20, 2018

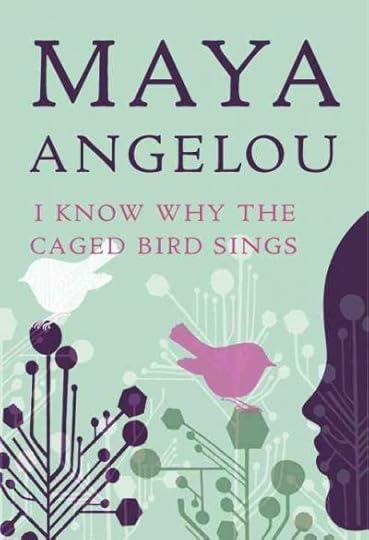

Maya Angelou

Marguerite Annie Johnson Angelou (April 4, 1928 – May 28, 2014), widely known as Maya Angelou, was an American author, actress, screenwriter, dancer, poet, and civil rights activist. This celebrated, inspiring, and prolific woman is best known for a multitude of accomplishments. Her 1969 memoir, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, made literary history for being the first nonfiction best-seller by an African-American woman.

During her lifetime, she published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, and several books of poetry. Her autobiography series chronicled her childhood, youth, and early adult experiences. Maya Angelou is also credited with writing a list of plays, movies, and television shows spanning more than 50 years. She received dozens of awards and more than thirty honorary doctoral degrees.

Traumatic Early Years

Maya and her older brother, Bailey Jr., were born to Vivian (Baxter) Johnson, a nurse. Their father, Bailey Johnson, worked as a doorman and navy dietitian. When Maya (so nicknamed by her brother) was three, her parents divorced and sent her and her brother to live with her grandparents in Stamps, Arkansas.

Four years later, Maya and her brother were shuttled back to live with her mother. At age eight, she was raped by her mother’s boyfriend, a man named Freeman. Jailed for only a day, Freeman was murdered four days after his release. Maya retreated into solitude out of guilt, believing she was the reason he was murdered, and became mute for five years. Later she wrote, “I thought my voice killed him; I killed that man, because I told his name. And then I thought I would never speak again, because my voice would kill anyone …”

It has been said that during these years of silence is when Maya developed her extraordinary memory, cultivated her passion and love for books and writing, and developed her outstanding ability to observe and listen to the world around her.

Shortly after Freeman’s murder, Maya and her brother returned once again to their grandparents home in Stamps, Arkansas. She credits her relationships with her brother, Bailey, and a friend of the family, Bertha Flowers, with helping her to start speaking again. Mrs. Flowers introduced Maya to a world of great authors who would influence and inspire her, including Charles Dickens, William Shakespeare, Frances Harper, and Jessie Fauset.

Wearer of Many Hats

At age 14, Maya and her brother moved back in with their mother, who was then living in Oakland, California. Ever the groundbreaker, Maya became the first black female streetcar conductor in San Francisco. At age 17, a few weeks after graduating from the California Labor School, Maya gave birth to her son Clyde (who later changed his name to Guy).

In 1950, despite the scrutiny of interracial relationships and the disapproval of her mother, Maya was briefly married to Tosh Angelos, a Greek sailor. It was then that she explored artistic and creative performance. In early 1952, she adopted the surname Angelou.

She dived into a career in theatre, performing in Porgy and Bess and several Broadway plays such as Cabaret for Freedom, which she wrote with Godfrey Cambridge. In 1961, Maya performed in an off-Broadway production of The Black’s, with James Earl Jones, Lou Gossett, Jr., and Cicely Tyson.

In the early 1960’s, Maya developed a relationship with South African freedom fighter Vusumzi Make, with whom she and her son, Guy, moved to Egypt. After they split in 1962, she and Guy moved to Ghana so that he could attend college, but he was severely injured in a car accident. They remained in Ghana until he completed his recovery in 1965.

In Ghana, Maya Angelou worked as an administrator at the University of Ghana, became an editor for The African Review, freelanced for the Ghanaian Times, and wrote and broadcast for Radio Ghana. She even worked and performed for Ghana’s National Theatre. A true wearer of many, many hats.

Maya Angelou page on Amazon

Prominent Friendships Met With Obstacles

The company Maya kept included other intelligent, trailblazing individuals that influenced her own brilliance. While in Ghana, she became close with Malcolm X, and after she returned to the United States in 1965, she helped him build the Organization of Afro-American Unity.

Devastated after Malcom X’s assassination, Maya bounced around between a variety of jobs and roles — she acted, wrote plays. In 1986 Martin Luther King Jr. asked her to organize a march. King was assassinated on her 40th birthday on April 4th, 1968.

Slipping further into depression after the loss of another heroic friend, Maya was lifted out of her downward spiral by another close friend, James Baldwin. Not long after, she once again tapped into her creative genius and stepped out of her comfort zone. She wrote, produced, and narrated Blacks, Blues, Black!, a ten-part series of documentaries about the connection between blues music and African heritage.

Maya’s first autobiography, I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings, was published in 1969. The book’s immediate succeess brought her international recognition.

A Tremendous Life of Many “Firsts”

In 1972, Maya wrote Georgia, Georgia, becoming the first black woman to have a screenplay produced. Over the course of the next ten years, she accomplished more than most people achieve in a lifetime. In 1973, she moved to Paris and married Paul du Feu, where she composed movie scores, wrote TV series, articles, poetry, short stories, and autobiographies, produced plays, and gave talks at universities and colleges.

In the late 1970’s, Maya met and befriended Oprah Winfrey, and the two become close friends.

After divorcing du Feu in 1981, Maya returned from Paris to the United States. Despite having no Bachelor’s degree, she accepted a job at Wake Forest University in North Carolina, becoming the first Reynolds Professor of American Studies. She was one of few full-time professors. Maya began to consider herself “a teacher who writes.”

In 1993, she became the first poet since Robert Frost to recite an original poem at a presidential inauguration. She recited her poem “On The Pulse Of Morning” at President Bill Clinton’s inauguration. In 1995, Maya was praised for her two-year streak for remaining on The New York Times‘ paperback nonfiction best-seller list. This was the longest-running record in the chart’s history.

Awards and Honors

Setting the bar high, Maya Angelou had a goal to direct a feature film, and achieved this 1996 when she directed Down in the Delta. It won the Chicago International Film Festival’s 1998 Audience Choice Award, and was recognized by the Acapulco Black Film Festival in 1999.

She also won two NAACP Image Awards in the Outstanding Literary Work (nonfiction) category.

She passed away on May 28th, 2014, at her home in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The news spread quickly and was mourned by many. Prominent public figures issued statements in memory of Maya Angelou, including President Barack Obamawho stated Angelou was “a brilliant writer, a fierce friend, and a truly phenomenal woman.”

Major Works (selected)

Maya Angelou’s body of writing was immense. Here’s a selection of some of her best known works.

Memoir and nonfiction

I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings (1969)

Gather Together In My Name (1974)

The Heart of A Woman (1981)

Wouldn’t Take Nothing For My Journey Now (1993)

All God’s Children Need Traveling Shoes (1986)

Even The Stars Look Lonesome (1997)

A Song Flung Up to Heaven (2002)

Letter to My Daughter (2009)

Mom & Me & Mom (2013)

Poetry

Just Give Me A Cool Drink Of Water ‘fore I Diiie (1971)

On The Pulse Of Morning (the inaugural poem, 1993)

Life Doesn’t Frighten Me (1993)

And Still I Rise (1978)

Phenomenal Woman (2011)

The Complete Poetry (2015)

Plays

Cabaret for Freedom (1960)

The Least of These (1966)

The Best of These (1966)

Gettin’ up Stayed on My Mind (1967)

And Still I Rise (1976)

Films

Blacks, Blues, Black! (1968)

Georgia, Georgia (1972)

Assignment America (1975)

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1979)

Sister, Sister (1982)

Brewster Place (1990)

Down in the Delta (1998)

The Black Candle (2012)

More information

Wikipedia

Official website of Maya Angelou

Reader discussion of Maya Angelou’s books on goodreads

Articles, news, etc

Obituary

The Paris Review interview

Oprah Interview

NYT on Maya Angelou

10 Questions With Maya Angelou

Why Maya Angelou Disliked Modesty

Maya Angelou’s Final Words

Smithsonian interview

Honoraries and awards

List of Honors by Maya Angelou

Caged Bird Legacy

Maya Angelou Poetry Foundation

Medal of Freedom 2010

Academy of Achievement

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Maya Angelou appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

Grammarly is a Writer’s Tool You Can’t Do Without!

Dorothy Parker famously said, “I can’t write five words but that I change seven.” The young Anaïs Nin complained that her works lacked concentration and clearness. “I drift into vague visions and abstract forms and above all superfluities.”

While it’s true that there are few things that make one a better writer than the practice of writing itself, there’s at least one way to improve the craft and correctness of one’s writing that’s almost like having a live-in copy editor cleaning up your prose as you go along. Grammarly is a writer’s tool you can’t do without — and I honestly can’t believe I’ve been doing without it for these many years!

Grammarly is super-easy to use. Once you sign in, you can test-drive the free option, which in itself is incredibly powerful. All you do is copy your document, say, a blog post, article, or chapter of a book, and paste it into the space provided on your personal page in the program. It then analyzes your document and points out your basic grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors. I’ll admit, I’m big on overusing commas. The program calls me out on that, and any other inadvertent sloppiness and I simply go back into my original doc to correct it. Then, it’s good to go.

If I had all the time in the world, I’d go back and check the hundreds of posts already on the Literary Ladies site. I’ve occasionally spotted embarrassing typos after the fact, but now, nothing new goes up before a Grammarly review.

True grammar nerds can join the Grammarly Facebook community, which is filled with fun grammar tips and discussions. Not surprisingly, Grammarly is used by hundreds of business and universities in addition to the millions of individual writers and students who have fallen in love with this great tool.

Free vs. premium plan

The free plan also includes an extension you can install for the major browsers, so that your writing gets checked wherever you post — for example, on social media. The premium version might be tempting for those with advanced writing needs. For example, it has a plagiarism feature that compares your writing against a library of over 8 billion web pages. If you’ve ever worried that you’ve unintentionally borrowed content, that would be flagged for you.

The premium version also offers vocabulary enhancement, more advanced context-related grammar checking, genre-specific writing suggestions, and a lot more. Both in the free and premium versions, the program keeps tabs on how well you’re doing with the writing you upload. Since I’m in the 96th percentile (“What?” says my dear departed mom, “Why not 100%?”), I think I’m pretty content with the free plan for now, but if my writing pursuits scale up enough, I might be tempted.

Before posting this, I’m going to go into my account to check. Stand by … OK, just two tiny errors. Not bad. But zero errors is better.

You might also like:

How to Stop Procrastinating and Start Writing

Affiliate disclosure: I’m so taken with Grammarly that I joined their affiliate program. All the views expressed here are sincere and my own. If the purchase of a premium account is made through the links in this review, Literary Ladies gets a small commission, which helps us maintain the site and keep it growing!

The post Grammarly is a Writer’s Tool You Can’t Do Without! appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

February 19, 2018

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys (1966)

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys is the last novel by this Dominican-British author. It’s considered a prequel and response to Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë, told from the perspective of Antoinette Conway, the sensual Creole heiress who wound up as the “madwoman in the attic.”

When Wide Sargasso Sea was published in 1966, Rhys had all but disappeared from the literary scene; her previous novel, Good Morning, Midnight, was published in 1939. Wide Sargasso Sea became her most successful novel, praised for its spare yet evocative language and its exploration of the power imbalance between men in women, between patriarchal colonizers and the original inhabitants of the Caribbean in the 1830s. It was the novel that rescued Rhys’s flagging reputation.

How Antoinette Cosway became Bertha Rochester

In Wide Sargasso Sea, Antoinette Cosway was the daughter of a white Creoles who were slave owners until the abolition of slavery in Dominica and Jamaica in 1833, after which they lost their fortune. As the W.W. Norton edition describes it:

“She is sold into marriage to the coldhearted and prideful Rochester, succumbs to his need for money and his lust. Yet he will make her pay for her ancestors’ sins of slaveholding, excessive drinking, and nihilistic despair by enslaving her as a prisoner in his bleak British home. Jean Rhys’s reputation was made upon the publication of this passionate and heartbreaking novel, in which she brings into the light one of fiction’s most mysterious characters: the madwoman in the attic from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.

In this best-selling novel, Rhys portrays a society so driven by hatred, so skewed in its sexual relations, that it can literally drive a woman out of her mind.”

Though the slim novel is a response to Jane Eyre, and quite sympathetic to Antoinette (who Rochester begins to call “Bertha,” after her mentally ill mother). Wide Sargasso Sea isn’t “fan fiction” in the modern sense, since it can stand alone as a reading experience. Nonetheless, for devotees of Jane Eyre, it imaginatively portrays the character of Mrs. Rochester, or Bertha, for whom readers might find fearsome, even monstrous.

This novel makes us understand how Bertha Rochester / Antoinette Cosway got to be who she was. Anyone who has felt uncomfortable about the first wife locked up in the attic in Charlotte Brontë’s classic novel will find Wide Sargasso Sea a cathartic experience, though the end result doesn’t change. The point of view in the novel alternates between Antoinette and Rochester, though more from hers than his. Here, her thoughts from the attic in which her husband has imprisoned her:

“In this room I wake early and lie shivering for it is very cold. At last Grace Poole, the woman who looks after me, lights a fire with paper and sticks and lumps of coal. She kneels to blow it with bellows. The paper shrivels, the sticks crackle and spit, the coal shoulders and glowers. In the end flames shoot up and they are beautiful. I get out of bed and go close to watch them and to wonder why I have been brought her. For what reason? There must be a reason. What is it that I must do?”

Insights from Rhys’s literary executor

The 1966 edition of Wide Sargasso Sea is introduced by Francis Wyndham, who was, until his own death, Rhys’s literary executor. Here, he offers further insight:

For many years, Jean Rhys has been haunted by the figure of the first Mrs. Rochester — the mad wife in Jane Eyre. The present novel — completed after much revision and agonized rejections of earlier versions — is her story. Not, of course, literally so: it is in no sense a pastiche of Charlotte Brontë and exists in its own right, quite independent of Jane Eyre.

But the Brontë book provided the initial inspiration for an imaginative feat almost uncanny in its vivid intensity. From her personal knowledge of the West Indies, and her reading of their history, Miss Rhys know about the made Creole heiress in the early 19th century, whose dowries were only an additional burden to them: products of an inbred, decadent, expatriate society, resented by the recently freed slaves whose superstitions they shared, they languished uneasily in the oppressive beauty of their tropical surroundings, ripe for exploitation.

Wide Sargasso Sea on Amazon

The novel is divided into three parts. The first is told in the heroine’s own words. In the second, the young Mr. Rochester describes his arrival in the West Indies, his marriage to Antoinette Cosway and its disastrous result. The last part is once more narrated by his wife, but the scene is now England, and she writes from the attic room in Thornfield Hall, the gloomy manse that we know from the story of Jane Eyre.

Jean Rhys’s books have shared a modern, urban background: Montparnasse cafés, cheap Left Bank hotels, Bloomsbury boarding-houses, furnished rooms near Notting Hill Gate area evoked with a bitter poetry that is entirely her own. Only the West Indian flashbacks in Voyage in the Dark and some episodes of The Left Bank strike a different note — one of regret for innocent sensuality in a lush, beguiling land.

In Wide Sargasso Sea, which is set in Jamaica and Dominica in the 1830s, she returns to that spiritual country as a distant dream: and discovers it, for all its beauty (and she conjures up the beauty with haunting perfection) to have been a nightmare.

More about Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

1993 film version of Wide Sargasso Sea

Wide Sargasso Sea revisited, on Paris Review

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys (1966) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

February 18, 2018

Margaret Mitchell

Margaret Mitchell (November 8, 1900 – August 16, 1949) is best known as the author of Gone With The Wind, one of the best selling novels in American literature. It was published in over 40 countries, and adapted into the famed movie of the same name. It has been said that she herself was the model for Scarlett O’Hara, one of the most complex and charismatic of literary heroines.

Her father was Eugene M. Mitchell, an attorney and an authority on Georgia history. Her mother was the late Maybelle Stephens Mitchell, and she had one brother, Stephens Mitchell, who became an attorney and history buff like his father.

Margaret, or Peggy, as she was called by those close to her, attended the Atlanta public schools, then attended Smith College in Massachusetts. After her first year she left due to her mother’s death, but didn’t return. At age twenty-two, in 1922, she began working for The Atlanta Journal Sunday Magazine. Three years later she married John R. Marsh, and the following year, 1926, she left her position at the newspaper due to an ankle injury. while convalescing, she began writing Gone With the Wind.

The agony of creating Gone With the Wind

Steeped in the mythology of the south, Margaret claimed that she didn’t realize that the Confederacy didn’t win the Civil War until she was 10 years old. She grew up hearing stories about the Civil War, the burning of Atlanta, and Reconstruction. A story began to take shape, though writing it was agonizing to the fledgling writer. Legend has it that she had trouble framing opening sentences as a reporter, and so for the book, she started with the last chapter and worked backwards.

For nine frustrating years she worked and reworked the massive story, sometimes typing, sometimes scribbling by hand. The manuscript piled up here and there, on desks, in drawers, on closet shelves. She showed friends bits and pieces, but never the entire work.

Finally, in the fall of 1935, H.S. Latham a representative of the Macmillan Company, a New York publisher, was traveling throughout the South looking for new talent. A former colleague of Peggy Mitchell mentioned to him that she was working on a book. When he contacted her, she told him she couldn’t show it, since it was still unfinished. Truthfully, she wasn’t confident in it. However, by evening, she changed her mind, met him, and handed him the manuscript, now well over 1,000 pages.

A publishing phenomenon

Several days later, Peggy Mitchell got news by wire that Gone With the Wind had been accepted for publication. contingent upon some revision. After nine years of working on the project, there was but a few more months of revising and editing.

The book went on sale on June 30, 1936. The person most surprised by the book’s immediate success was the author herself, a writer completely unknown to the public.

Mitchell was hoping that GWTW , clocking in at 1,037 pages, would sell 5,000 copies so that the publisher didn’t lose money on the enterprise. It sold 50,000 copies in one day shortly after its publication, 176,000 copies within the first three weeks, and 1 million copies within the first six months. This was all the more remarkable considering that the book industry was still trying to recover from the worst of the Depression.

Even as the book became a massive publishing phenomenon, reviews were mixed. It was compared with Vanity Fair and War and Peace. Yet other reviewers felt it romanticized the the plantation life, built on a foundation of slavery, and that it sympathized with the Confederacy.

The 1937 Pulitzer Prize and the loss of a private life

After GWTW won the Pulitzer Prize in 1937, Mitchell received an honorary degree from Smith College, as well as all manner of other awards and accolades. She was inundated with requests for interviews and besieged with requests for her autograph. Often, she was asked whether she intended to write another book. Her answer was that she was too busy being the author of GWTW to have the time and privacy to sit and write. This remained true for pretty much the rest of her life.

Some years later, the governor of Georgia wanted to appoint her to the state’s Board of Education, and she replied,

“My time is not my own. It has not been my own since Gone With the Wind was published. The very fact that since 1936 I have never had the time to sit down to my typewriter and write — or try to write — another book will give you some indication of what I mean … Being the author of Gone With the Wind is a full-time job, and most days it is an overtime job filling engagements and meeting visitors.”

Movie rights and a phenomenally successful film

David O. Selznick paid Mitchell $50,000 for the film rights to GWTW. The casting of the film was followed with breathless interest by the public, with the most interest in who would play Scarlett O’Hara. Selznick conceived the idea of conducting a worldwide search for the right person to play Scarlett O’Hara. The campaign, directed by Selznick’s publicity chief, helped occupy the public mind during the long months before filming began. As it turned out, the film began shooting before a suitable Scarlett could be cast. Read more about the search for Scarlett O’Hara.

GWTW won for Best Picture of 1939, among other award categories. Vivien Leigh, a British stage actress, seemed born to portray the complicated Scarlett O’Hara. She won Best Actress, as did Hattie McDaniel for her portrayal of Mammie. Other major cast members nominated were Clark Gable (Rhett Butler) and Olivia de Havilland (Melanie Wilkes).

The film’s legacy, like the book’s, has been mixed. The cinematic achievement is weighed against the stereotypical portrayal of blacks and romanticism of the old South.

Gone With the Wind (1939 film)

A secret philanthropist

It wasn’t until the 1990s that a surprising discovery was made: Margaret Mitchell secretly funded the educations of dozens of African-American medical students at the historically black Morehouse College in Atlanta with the wealth she earned from GWTW book sales and film rights. These anonymous grants were made by Mitchell throughout the 1940s.

It started when Mitchell discovered how difficult it was to get good medical treatment for her domestic help, who were black women, as was common in that time. Gradually, she developed a correspondence with Benjamin E. Mays, the president of Morehouse College, which led to her anonymously funding of the medical students. More about this incredible story can be found in The Atlanta Magazine’s article on the subject.

Untimely death

Mitchell was only 48 when a motorist struck and killed her (she was on foot) in her native Atlanta, some twelve years after the publication of her blockbuster. She was with her husband, John Marsh, when she was struck by the car of the speeding, drunken driver, and sustained a fracture to her skull.

Her only other work known is a novella called Lost Laysen, written when she was only fifteen. It was discovered and published many years after her death. Margaret Mitchell will always be remembered for Gone with the Wind, still one of the most popular and influential novels in American publishing history.

More about Margaret Mitchell on this site

6 Reasons to Love Margaret Mitchell

Quotes from Gone With the Wind and Others

Original 1936 Review of Gone With the Wind in the New York Times

Original 1949 obituary from the New York Times

Gone With The Wind: Echoing Through the Ages

Gone With the Wind (1939 film)

Gone With the Wind: A Publishing Phenomenon

The Search for Scarlett O’Hara

Lost Laysen (1916): A Lost Novella Rediscovered

4 Prequels and Sequels to Gone With the Wind

Major Works

Gone With The Wind

Biographies about Margaret Mitchell

Southern Daughter: The Life of Margaret Mitchell by Darden Asbury Pyron

Margaret Mitchell and John Marsh: The Love Story

Behind Gone With the Wind by Marianne Walker

Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind: A Bestseller’s Odyssey

from Atlanta to Hollywood by Ellen F. Brown and John Wiley

More Information

Margaret Mitchell on Wikipedia

Margaret Mitchell: American Rebel (PBS documentary)

Margaret Mitchell: Atlanta History Center

Reader discussion of works by or about Margaret Mitchell on Goodreads

Margaret Mitchell page on Amazon

Articles, News, Etc.

Mitchell Tops Poll of Put-Downs

Texas woman opens ‘Gone with the Wind’ Museum

10 Things You Might not Know About Gone with the Wind

Visit Margaret Mitchell’s Home

Margaret Mitchell House – Atlanta, Georgia

You might also like: 6 Reasons to Love Margaret Mitchell

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Margaret Mitchell appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

February 16, 2018

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë: A late 19th-century analysis

This introduction to and analysis of Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (1847) is excerpted from Life and Works of the Sisters Brontë by Mary A. Ward, a 19th-century British novelist and literary critic. Though much was written about this novel, before and since, this excerpt abbreviated from Ward’s 1899 book about the Brontës is a critical yet insightful analysis of the beloved novel.

Ward doesn’t hold back on what she feels are the inconsistencies and even the absurdities of the plot and characters. Seriously — locking a mentally ill wife in an attic? But in the end, she overlooks what generations of readers have also looked past, and acknowledged that this novel is one of the greats because the author’s personality and talent shine through.

From an unknown to a secure literary legacy

Jane Eyre was first published in October 1847. Half a century—since this tale of the North by an unknown writer stole upon London, and, in the very midst of the serial publication of Vanity Fair, took the town by storm, obtaining for its author in the course of a few weeks a success which, as the creator of Becky Sharp (Thackeray) afterwards said to her, a little sadly and sharply, “it took me the work of ten years to achieve.”

… Judging by the books that have been written and read in recent years, by the common verdict as to the Brontë sisters, their story, and their work, which prevails, almost without exception, in the literary criticism of the present day; by the tone of personal tenderness, even of passionate homage, in which many writers speak of Charlotte and of Emily; and by the increasing recognition which their books have obtained abroad, one may say with some confidence that the name and memory of the Brontës were never more alive than now, that “Honour and Fame have got about their graves” for good and all, and that Charlotte and Emily Brontë are no less secure, at any rate, than Jane Austen or George Eliot or Mrs. Browning of literary recollection in the time to come.

A brief summary of plot

Jane Eyre, to run through a summary of the plot is the story of an orphan girl, reared at a Charity School amid many hardships, going out into the world as a governess, and falling in love with her employer, Mr. Rochester. She yields herself to her own passion and to his masterful love-making with an eager, an over-eager abandonment.

The wedding-day is fixed; the small marriage party assembles. But in the very church, and at the moment of the ceremony, it is revealed to Jane Eyre that Mr. Rochester has a wife living, a frenzied lunatic who has been confined for months in a corner of the same house where she and Rochester have had their daily dwelling; that Rochester has deliberately entrapped her, and that she stands on the edge of an abyss.

The marriage party breaks up in confusion, and Rochester’s next endeavor is to persuade the stunned and miserable Jane to scout law and convention, and fly with him to love and foreign parts. He shows her the lunatic, in all the odious horror of her state, and Jane forgives him on the spot, having never indeed, so far as appears, felt any deep resentment of his conduct. Nevertheless, she summons up the courage to leave him.

She steals away by night, and, after days of wandering and starvation, she finds a home with the Rivers family, who ultimately turn out to be her cousins. St. John Rivers, the brother of the family, an Evangelical clergyman possessed with a fanatical enthusiasm for missionary life, observes the girl’s strong and energetic nature, and makes up his mind to marry her, not in the least because he loves her, but because he thinks her fitted to be a missionary’s wife.

Her will is on the point of yielding to his when she hears a mysterious midnight call from Rochester; she hurries back to her master, to find him blinded and maimed by the fire which has destroyed his house and his mad wife together; and of course, the end is happiness.

A plot abounding in absurdities and inconsistencies

Now certainly there never was a plot, which pretended to be a plot, of looser texture than that of Jane Eyre. It abounds with absurdities and inconsistencies. The critics of Charlotte Brontë’s time had no difficulty in pointing them out; they are, indeed, on the surface for all to see.

That such incidents should have happened to Jane Eyre in Mr. Rochester’s house as did happen, without awakening her suspicions; that the existence of a lunatic should have been commonly known to all the servants of the house, yet wholly concealed from the governess; that Mr. Rochester should have been a man of honor and generosity, a man with whom not only Jane Eyre, but clearly the writer herself, is in love, and yet capable of deliberately betraying and deceiving a girl of twenty placed in a singularly helpless position; these are the fundamental puzzles of the story.

Mrs. Fairfax is a mystery throughout. How, knowing what she did, did she not inevitably know more? What was her real relation to Rochester? To Jane Eyre? These are questions that no one can answer out of the four corners of the book. The country-house party is a tissue of extravagance throughout; the sarcasms and brutalities of the beautiful Miss Ingram are no more credible than the manners assumed by the aristocratic Rochester from the beginning towards his ward’s governess, or the amazing freedom with which he pours into the ears of the same governess a virtuous girl of twenty, who has been no more than a few weeks under his roof the story of his relations with Adele’s mother.

You might also like: Quotes from Jane Eyre

Early scene between Jane and Rochester

Turn to the early scenes, for instance, between Jane and Rochester. They have been “several days” under the same roof; it is Jane’s second interview with her employer. Mr. Rochester, in Sultan fashion, sends for her and her pupil after dinner. He sits silent, while Jane’s quick eye takes note of him. Suddenly he turns upon her.

“You examine me, Miss Eyre,’ said he; “do you think me handsome?”

Jane, taken by surprise, delivers a stout negative, whereupon her employer, in caprice or pique, pursues the subject further:

“Criticize me: does my forehead not please you?”

He lifted up the sable waves of hair which lay horizontally over his brow and showed a solid enough mass of intellectual organs, but an abrupt deficiency where the suave sign of benevolence should have risen.

Poor Jane gets out of the dilemma as best she can, and gradually this astonishing gentleman thaws, becoming conversational and kind. And this is how he puts the little governess at her ease:

“You look very much puzzled, Miss Eyre; and though you are not pretty, any more than I am handsome, yet a puzzled air becomes you; besides, it is convenient, for it keeps those searching eyes of yours away from my physiognomy, and busies them with the worsted flowers of the rug; so puzzle on. Young lady, I am disposed to be gregarious and communicative to-night.”

Other weaknesses in plot

… As to the other weaknesses of plot and conception, they are very obvious and very simple. The “arrangements” by which Jane Eyre is led to find a home in the Rivers household, and becomes at once her uncle’s heiress, and the good angel of her newly discovered cousins; the device of the phantom voice that recalls her to Rochester’s side; the fire that destroys the mad wife, and delivers into Jane’s hands a subdued and helpless Rochester; all these belong to that more mechanical and external sort of plot-making, which the modern novelist of feeling and passion as distinguished from the novelist of adventure prides himself on renouncing …

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë on Amazon

Courage is the true subject of Jane Eyre

The true subject of Jane Eyre is the courage with which a friendless and loving girl confronts her own passion, and, in the interest of some strange social instinct which she knows as “duty,” which she cannot explain and can only obey, tramples her love underfoot, and goes out miserable into the world.

Beside this wrestle of the human will, everything else is trivial or vulgar. The various expedient legacies, uncles, fires, and coincidences by which Jane Eyre is ultimately brought to happiness, cheapen and degrade the book without convincing the reader … Jane Eyre is on the one side a rather poor novel of incident, planned on the conventional pattern, and full of clumsy execution; on another side it is a picture of passion and of ideas, for which in truth the writer had no sufficient equipment; she moves imprisoned … in “a narrow circle of thoughts.”

The personality of the author overcomes the book’s defects

If you press it, the psychology of the book is really childish; Rochester is absurd, Jane Eyre, in spite of the stir that she makes, only half-realized and half-conscious. Still, as a study of feeling, adapted to some extent to modern realist demands, the novel came at a happy moment. It is one of the signs, no doubt, that mark the transition from the old novel to the new, from the old novel of plot and coincidence to the new novel of psychology and character.

But, given the defects of the book, how is it possible to assign it a high place in the history of that great modern art which has commanded the knowledge of a Tolstoy, and the mind of a Turgenev, which is the subtle interpreter and not the vulgar stage-manager of nature, which shrinks from the merely obvious and vigorous, and is ever pressing forward toward that more delicate, more complex, more elusive expression, satisfying in proportion to its incompleteness, which is the highest response of human genius to this unintelligible world?’

… Yet, in spite of it all, Jane Eyre persists, and Charlotte Brontë is with the immortals … There are books where the writer seems to be everything, the material employed, the environment, almost nothing. The main secret of the charm that clings to Charlotte Brontë’s books is, and will always be, the contact which they give us with her own fresh, indomitable, surprising personality — surprising, above all.

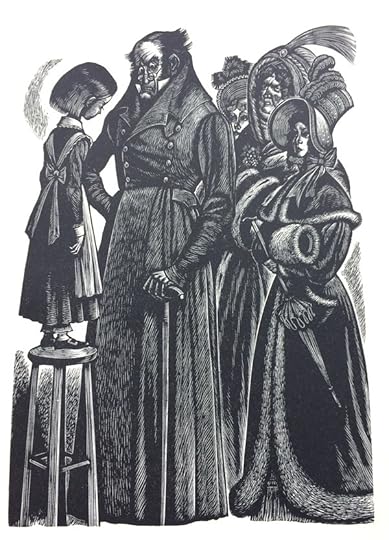

Illustration by Fritz Eichenberg from Jane Eyre, from an 1943 edition

The magic of the unexpected

In spite of its conventionalities of scheme, Jane Eyre has, in detail, in conversation, in the painting of character, that perpetual magic of the unexpected which overrides a thousand faults and keeps the mood of the reader happy and alert. The expedients of the plot may irritate or chill the artistic sense; the voice of the story-teller, in its inflections of passion, or feeling or reverie, charms and holds the ear, almost from first to last.

The general plan may be commonplace, the ideas even of no great profundity; but the book is original. How often in the early scenes of childhood or school-life does one instinctively expect the conventional solution, the conventional softening, the conventional prettiness or quaintness, that so many other storytellers, of undoubted talent, could not have resisted! And it never comes.

Hammer-like, the blows of a passionate realism descend. Jane Eyre, the little helpless child, is never comforted; Mrs. Reid, the cruel aunt, is never sorry for her cruelties; Bessie, the kind nurse, is not very kind, she does not break the impression, she satisfies no instinct of poetic compensation, she only just makes the story credible, the reader’s assent possible.

So, at Lowood, Helen Burns is not a suffering angel; there is nothing consciously pretty or touching in the wonderful picture of her; reality, with its discords, its infinite novelties, lends word and magic to the passion of Charlotte’s memory of her dead sister; all is varied, living, poignant, full of the inexhaustible savor of truth, and warm with the fire of the heart. So that at last, when pure pathos comes, when Helen sleeps herself to death in Jane’s arms, when the struggle is over, and room is made for softness, for pity, the mind of the reader yields itself wholly, without reserve, to the working of an artist so masterful, so self-contained, so rightly frugal as to the great words and great emotions of her art.

Read the full analysis on Wikisource.

More about Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Why Villette is Better than Jane Eyre

How Charlotte Brontë Came to Write Jane Eyre

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë: A late 19th-century analysis appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

February 15, 2018

Transcendental Wild Oats by Louisa May Alcott (1973) – full text

Transcendental Wild Oats by Louisa May Alcott is a satire, somewhere in length between a short story and novella, about her family’s misadventures as part of the Fruitlands community in the 1840s. It was first published in a New York newspaper in 1873.

Alcott thinly disguised the members of the Transcendentalist community. Her father, Amos Bronson Alcott was a co-founder of the community. In the fictional version he became “Abel Lamb.” Her mother, Abigail May Alcott, is presented as “Sister Hope.” Louis makes no attempt to soften the truth in her satire, portraying Abel Lamb is an impractical dreamer; Sister Hope actually feels hopeless —overworked and frustrated by the hapless men.

An impending storm threatens to ruin the grain crop at harvest time. Sister Hope rallies the children, three small girls and a boy, to save the crop. It’s not enough to save the community, though; Abel Lamb and his co-leader, “Timon Lion” (modeled after real-life Charles Lane) are crushed that their experiment fails. Louisa May Alcott published Work: A Story of Experience the same year that this story came out. Both examine how female members of families are exploited for their industriousness and victimized by a patriarchal system.

Here is the text of Transcendental Wild Oats in full:

On the first day of June, 184-, a large wagon, drawn by a small horse and containing a motley load, went lumbering over certain New England hills, with the pleasing accompaniments of wind, rain, and hail. A serene man with a serene child upon his knee was driving, or rather being driven, for the small horse had it all his own way. A brown boy with a William Penn style of countenance sat beside him, firmly embracing a bust of Socrates. Behind them was an energetic-looking woman, with a benevolent brow, satirical mouth, and eyes brimful of hope and courage

A baby reposed upon her lap, a mirror leaned against her knee, and a basket of provisions xdanced about at her feet, as she struggled with a large, unruly umbrella. Two blue-eyed little girls, with hands full of childish treasures, sat under one old shawl, chatting happily together.

In front of this lively party stalked a tall, sharp-featured man, in a long blue cloak; and a fourth small girl trudged along beside him through the mud as if she rather enjoyed it.

The wind whistled over the bleak hills; the rain fell in a despondent drizzle, and twilight began to fall. But the calm man gazed as tranquilly into the fog as if he beheld a radiant bow of promise spanning the gray sky. The cheery woman tried to cover every one but herself with the big umbrella. The brown boy pillowed his head on the bald pate of Socrates and slumbered peacefully. The little girls sang lullabies to their dolls in soft, maternal murmurs. The sharp-nosed pedestrian marched steadily on, with the blue cloak streaming out behind him like a banner; and the lively infant splashed through the puddles with a ducklike satisfaction pleasant to behold.

Thus these modern pilgrims journeyed hopefully out of the old world, to found a new one in the wilderness.

The editors of The Transcendental Tripod had received from Messrs. Lion & Lamb (two of the aforesaid pilgrims) a communication from which the following statement is an extract:

“We have made arrangements with the proprietor of an estate of about a hundred acres which liberates this tract from human ownership. Here we shall prosecute our effort to initiate a Family in harmony with the primitive instincts of man.

“Ordinary secular farming is not our object. Fruit, grain, pulse, herbs, flax, and other vegetable products, receiving assiduous attention, will afford ample manual occupation, and chaste supplies for the bodily needs. It is intended to adorn the pastures with orchards, and to supersede the labor of cattle by the spade and the pruning-knife.

“Consecrated to human freedom, the land awaits the sober culture of devoted men. Beginning with small pecuniary means, this enterprise must be rooted in a reliance on the succors of an ever-bounteous Providence, whose vital affinities being secured by this union with uncorrupted field and unworldly persons, the cares and injuries of a life of gain are avoided.

“The inner nature of each member of the Family is at no time neglected. Our plan contemplates all such disciplines, cultures, and habits as evidently conduce to the purifying of the inmates.

“Pledged to the spirit alone, the founders anticipate no hasty or numerous addition to their numbers. The kingdom of peace is entered only through the gates of self-denial; and felicity is the test and the reward of loyalty to the unswerving law of Love.”

This prospective Eden at present consisted of an old red farm-house, a dilapidated barn, many acres of meadow-land, and a grove. Ten ancient apple-trees were all the “chaste supply” which the place offered as yet; but, in the firm belief that plenteous orchards were soon to be evoked from their inner consciousness, these sanguine founders had christened their domain Fruitlands.

Here Timon Lion intended to found a colony of Latter Day Saints, who, under his patriarchal sway, should regenerate the world and glorify his name for ever. Here Abel Lamb, with the devoutest faith in the high ideal which was to him a living truth, desired to plant a Paradise, where Beauty, Virtue, Justice, and Love might live happily together, without the possibility of a serpent entering in. And here his wife, unconverted but faithful to the end, hoped, after many wanderings over the face of the earth, to find rest for herself and a home for her children.

“There is our new abode,” announced the enthusiast, smiling with a satisfaction quite undamped by the drops dripping from his hatbrim, as they turned at length into a cart-path that wound along a steep hillside into a barren looking valley.

“A little difficult of access,” observed his practical wife, as she endeavored to keep her various household gods from going overboard with every lurch of the laden ark.

“Like all good things. But those who earnestly desire and patiently seek will soon find us,” placidly responded the philosopher from the mud, through which he was now endeavoring to pilot the much-enduring horse.

“Truth lies at the bottom of a well, Sister Hope,” said Brother Timon, pausing to detach his small comrade from a gate, whereon she was perched for a clearer gaze into futurity.

“That’s the reason we so seldom get at it, I suppose,” replied Mrs. Hope, making a vain clutch at the mirror, which a sudden jolt sent flying out of her hands.

“We want no false reflections here,” said Timon, with a grim smile, as he crunched the fragments under foot in his onward march.

Sister Hope held her peace, and looked wistfully through the mist at her promised home. The old red house with a hospitable glimmer at its windows cheered her eyes; and, considering the weather, was a fitter refuge than the sylvan bowers some of the more ardent souls might have preferred.

The new-comers were welcomed by one of the elect precious — a regenerate farmer, whose idea of reform consisted chiefly in wearing white cotton raiment and shoes of untanned leather. This costume, with a snowy beard, gave him a venerable, and at the same time a somewhat bridal appearance.

The goods and chattels of the Society not having arrived, the weary family reposed before the fire on blocks of wood, while Brother Moses White regaled them with roasted potatoes, brown bread and water, in two plates, a tin pan, and one mug; his table service being limited. But, having cast the forms and vanities of a depraved world behind them, the elders welcomed hardship with the enthusiasm of new pioneers, and the children heartily enjoyed this foretaste of what they believed was to be a sort of perpetual picnic.

During the progress of this frugal meal, two more brothers appeared. One a dark, melancholy man, clad in homespun, whose peculiar mission was to turn his name hind part before and use as few words as possible. The other was a bland, bearded Englishman, who expected to be saved by eating uncooked food and going without clothes. He had not yet adopted the primitive costume, however; but contented himself with meditatively chewing dry beans out of a basket.

“Every meal should be a sacrament, and the vessels used should be beautiful and symbolical,” observed Brother Lamb, mildly, righting the tin pan slipping about on his knees. “I priced a silver service when in town, but it was too costly; so I got some graceful cups and vases of Britannia ware.”

“Hardest things in the world to keep bright. Will whiting be allowed in the community?” inquired Sister Hope, with a housewife’s interest in labor-saving institutions.

“Such trivial questions will be discussed at a more fitting time,” answered Brother Timon, sharply, as he burnt his fingers with a very hot potato. “Neither sugar, molasses, milk, butter, cheese, nor flesh are to be used among us, for nothing is to be admitted which has caused wrong or death to man or beast.”

“Our garments are to be linen till we learn to raise our own cotton or some substitute for woollen fabrics,” added Brother Abel, blissfully basking in an imaginary future as warm and brilliant as the generous fire before him.

“Haou abaout shoes?” asked Brother Moses, surveying his own with interest.

You might also like

Work: A Story of Experience

“We must yield that point till we can manufacture an innocent substitute for leather. Bark, wood, or some durable fabric will be invented in time. Meanwhile, those who desire to carry out our idea to the fullest extent can go barefooted,” said Lion, who liked extreme measures.

“I never will, nor let my girls,” murmured rebellious Sister Hope, under her breath.

“Haou do you cattle’ate to treat the ten-acre lot? Ef things ain’t ‘tended to right smart, we shan’t hev no crops,” observed the practical patriarch in cotton.

“We shall spade it,” replied Abel, in such perfect good faith that Moses said no more, though he indulged in a shake of the head as he glanced at hands that had held nothing heavier than a pen for years. He was a paternal old soul and regarded the younger men as promising boys on a new sort of lark.

“What shall we do for lamps, if we cannot use any animal substance? I do hope light of some sort is to be thrown upon the enterprise,” said Mrs. Lamb, with anxiety, for in those days kerosene and camphene were not, and gas unknown in the wilderness.

“We shall go without till we have discovered some vegetable oil or wax to serve us,” replied Brother Timon, in a decided tone, which caused Sister Hope to resolve that her private lamp should be always trimmed, if not burning.

“Each member is to perform the work for which experience, strength, and taste best fit him,” continued Dictator Lion. “Thus drudgery and disorder will be avoided and harmony prevail. We shall rise at dawn, begin the day by bathing, followed by music, and then a chaste repast of fruit and bread. Each one finds congenial occupation till the meridian meal; when some deep-searching conversation gives rest to the body and development to the mind. Healthful labor again engages us till the last meal, when we assemble in social communion, prolonged till sunset, when we retire to sweet repose, ready for the next day’s activity.”

“What part of the work do you incline to yourself?” asked Sister Hope, with a humorous glimmer in her keen eyes.

“I shall wait till it is made clear to me. Being in preference to doing is the great aim, and this comes to us rather by a resigned willingness than a wilful activity, which is a check to all divine growth,” responded Brother Timon.

“I thought so.” And Mrs. Lamb sighed audibly, for during the year he had spent in her family Brother Timon had so faithfully carried out his idea of “being, not doing,” that she had found his “divine growth” both an expensive and unsatisfactory process.

Here her husband struck into the conversation, his face shining with the light and joy of the splendid dreams and high ideals hovering before him.

“In these steps of reform, we do not rely so much on scientific reasoning or physiological skill as on the spirit’s dictates. The greater part of man’s duty consists in leaving alone much that he now does. Shall I stimulate with tea, coffee, or wine? No. Shall I consume flesh? Not if I value health. Shall I subjugate cattle? Shall I claim property in any created thing? Shall I trade? Shall I adopt a form of religion? Shall I interest myself in politics? To how many of these questions — could we ask them deeply enough and could they be heard as having relation to our eternal welfare — would the response be ‘Abstain’?”

A mild snore seemed to echo the last word of Abel’s rhapsody, for Brother Moses had succumbed to mundane slumber and sat nodding like a massive ghost. Forest Absalom, the silent man, and John Pease, the English member, now departed to the barn; and Mrs. Lamb led her flock to a temporary fold, leaving the founders of the “Consociate Family” to build castles in the air till the fire went out and the symposium ended in smoke.

The furniture arrived next day, and was soon bestowed; for the principal property of the community consisted in books. To this rare library was devoted the best room in the house, and the few busts and pictures that still survived many flittings were added to beautify the sanctuary, for here the family was to meet for amusement, instruction, and worship.

Any housewife can imagine the emotions of Sister Hope, when she took possession of a large, dilapidated kitchen, containing an old stove and the peculiar stores out of which food was to be evolved for her little family of eleven. Cakes of maple sugar, dried peas and beans, barley and hominy, meal of all sorts, potatoes, and dried fruit. No milk, butter, cheese, tea, or meat appeared. Even salt was considered a useless luxury and spice entirely forbidden by these lovers of Spartan simplicity. A ten years’ experience of vegetarian vagaries had been good training for this new freak, and her sense of the ludicrous supported her through many trying scenes.

Unleavened bread, porridge, and water for breakfast; bread, vegetables, and water for dinner; bread, fruit, and water for supper was the bill of fare ordained by the elders. No teapot profaned that sacred stove, no gory steak cried aloud for vengeance from her chaste gridiron; and only a brave woman’s taste, time, and temper were sacrificed on that domestic altar.

The vexed question of light was settled by buying a quantity of bayberry wax for candles; and, on discovering that no one knew how to make them, pine knots were introduced, to be used when absolutely necessary. Being summer, the evenings were not long, and the weary fraternity found it no great hardship to retire with the birds. The inner light was sufficient for most of them. But Mrs. Lamb rebelled. Evening was the only time she had to herself, and while the tired feet rested the skilful hands mended torn frocks and little stockings, or anxious heart forgot its burden in a book.

So “mother’s lamp” burned steadily, while the philosophers built a new heaven and earth by moonlight; and through all the metaphysical mists and philanthropic pyrotechnics of that period Sister Hope played her own little game of “throwing light,” and none but the moths were the worse for it.

Such farming probably was never seen before since Adam delved. The band of brothers began by spading garden and field; but a few days of it lessened their ardor amazingly. Blistered hands and aching backs suggested the expediency of permitting the use of cattle till the workers were better fitted for noble toil by a summer of the new life.

Brother Moses brought a yoke of oxen from his farm — at least, the philosophers thought so till it was discovered that one of the animals was a cow; and Moses confessed that he “must be let down easy, for he couldn’t live on garden sarse entirely.”

Great was Dictator Lion’s indignation at this lapse from virtue. But time pressed, the work must be done; so the meek cow was permitted to wear the yoke and the recreant brother continued to enjoy forbidden draughts in the barn, which dark proceeding caused the children to regard him as one set apart for destruction.

The sowing was equally peculiar, for, owing to some mistake, the three brethren, who devoted themselves to this graceful task, found when about half through the job that each had been sowing a different sort of grain in the same field; a mistake which caused much perplexity, as it could not be remedied; but, after a long consultation and a good deal of laughter, it was decided to say nothing and see what would come of it.

The garden was planted with a generous supply of useful roots and herbs; but, as manure was not allowed to profane the virgin soil, few of these vegetable treasures ever came up. Purslane reigned supreme, and the disappointed planters ate it philosophically, deciding that Nature knew what was best for them, and would generously supply their needs, if they could only learn to digest her “sallets” and wild roots.

The orchard was laid out, a little grafting done, new trees and vines set, regardless of the unfit season and entire ignorance of the husbandmen, who honestly believed that in the autumn they would reap a bounteous harvest.

Slowly things got into order, and rapidly rumors of the new experiment went abroad, causing many strange spirits to flock thither, for in those days communities were the fashion and transcendentalism raged wildly. Some came to look on and laugh, some to be supported in poetic idleness, a few to believe sincerely and work heartily. Each member was allowed to mount his favorite hobby and ride it to his heart’s content. Very queer were some of the riders, and very rampant some of the hobbies.

One youth, believing that language was of little consequence if the spirit was only right, startled new-comers by blandly greeting them with “Good-morning, damn you,” and other remarks of an equally mixed order. A second irrepressible being held that all the emotions of the soul should be freely expressed, and illustrated his theory by antics that would have sent him to a lunatic asylum, if, as an unregenerate wag said, he had not already been in one. When his spirit soared, he climbed trees and shouted; when doubt assailed him, he lay upon the floor and groaned lamentably. At joyful periods, he raced, leaped, and sang; when sad, he wept aloud; and when a great thought burst upon him in the watches of the night, he crowed like a jocund cockerel, to the great delight of the children and the great annoyance of the elders. One musical brother fiddled whenever so moved, sang sentimentally to the four little girls, and put a music-box on the wall when he hoed corn.

Brother Pease ground away at his uncooked food, or browsed over the farm on sorrel, mint, green fruit, and new vegetables. Occasionally he took his walks abroad, airily attired in an unbleached cotton poncho, which was the nearest approach to the primeval costume he was allowed to indulge in. At midsummer he retired to the wilderness, to try his plan where the woodchucks were without prejudices and huckleberrybushes were hospitably full. A sunstroke unfortunately spoilt his plan, and he returned to semi-civilization a sadder and wiser man.

Forest Absalom preserved his Pythagorean silence, cultivated his fine dark locks, and worked like a beaver, setting an excellent example of brotherly love, justice, and fidelity by his upright life. He it was who helped overworked Sister Hope with her heavy washes, kneaded the endless succession of batches of bread, watched over the children, and did the many tasks left undone by the brethren, who were so busy discussing and defining great duties that they forgot to perform the small ones.

Moses White placidly plodded about, “chorin’ raound,” as he called it, looking like an old-time patriarch, with his silver hair and flowing beard, and saving the community from many a mishap by his thrift and Yankee shrewdness.

Brother Lion domineered over the whole concern; for, having put the most money into the speculation, he was resolved to make it pay,-as if anything founded on an ideal basis could be expected to do so by any but enthusiasts.

Abel Lamb simply revelled in the Newness, firmly believing that his dream was to be beautifully realized and in time not only little Fruitlands, but the whole earth, be turned into a Happy Valley. He worked with every muscle of his body, for he was in deadly earnest. He taught with his whole head and heart; planned and sacrificed, preached and prophesied, with a soul full of the purest aspirations, most unselfish purposes, and desires for a life devoted to God and man, too high and tender to bear the rough usage of this world.

It was a little remarkable that only one woman ever joined this community. Mrs. Lamb merely followed wheresoever her husband led, “as ballast for his balloon,” as she said, in her bright way.

Miss Jane Gage was a stout lady of mature years, sentimental, amiable, and lazy. She wrote verses copiously, and had vague yearnings and graspings after the unknown, which led her to believe herself fitted for a higher sphere than any she had yet adorned.

Having been a teacher, she was set to instructing the children in the common branches. Each adult member took a turn at the infants; and, as each taught in his own way, the result was a chronic state of chaos in the minds of these much-afflicted innocents.

Sleep, food, and poetic musings were the desires of dear Jane’s life, and she shirked all duties as clogs upon her spirit’s wings. Any thought of lending a hand with the domestic drudgery never occurred to her; and when to the question, “Are there any beasts of burden on the place?” Mrs. Lamb answered, with a face that told its own tale, “Only one woman!” the buxom Jane took no shame to herself, but laughed at the joke, and let the stout-hearted sister tug on alone.

Unfortunately, the poor lady hankered after the flesh-pots, and endeavored to stay herself with private sips of milk, crackers, and cheese, and on one dire occasion she partook of fish at a neighbor’s table.

One of the children reported this sad lapse from virtue, and poor Jane was publicly reprimanded by Timon.

“I only took a little bit of the tail,” sobbed the penitent poetess.

“Yes, but the whole fish had to be tortured and slain that you might tempt your carnal appetite with that one taste of the tail. Know ye not, consumers of flesh meat, that ye are nourishing the wolf and tiger in your bosoms?”

At this awful question and the peal of laughter which arose from some of the younger brethren, tickled by the ludicrous contrast between the stout sinner, the stern judge, and the naughty satisfaction of the young detective, poor Jane fled from the room to pack her trunk and return to a world where fishes’ tails were not forbidden fruit.