Jessie Redmon Fauset

Jessie Redmon Fauset (April 27, 1882 – April 30, 1961) was an American editor, poet, essayist, and novelist who was deeply involved with the Harlem Renaissance literary movement. Born in Camden County, New Jersey, and raised in Philadelphia, she was the daughter of a Methodist Episcopal minister. Her mother died when she was quite young.

Bright and studious, Jessie Fauset was the first African-American to graduate from the Philadelphia High School for Girls. A stellar student, she wished to continue her studies at Bryn Mawr College, but the institution got around admitting a black student by securing a scholarship for her at Cornell University. There she studied classical languages, and later earned a Master’s degree in French from the University of Pennsylvania.

After graduating in 1905, she wanted to teach in Philadelphia, but found the schools once again unwelcoming to an African-American woman.She taught French in Baltimore and Washington, D.C. schools.

Literary editor of The Crisis

In 1912, Fauset began to submit poems, stories, and essays to the NAACP’s magazine,The Crisis. The magazine’s chief editor, the eminent scholar W.E.B. Du Bois, must have been quite impressed with her work, as he wasn’t easy to please. She was still teaching at the time, but he convinced her to move to New York City and work as the magazine’s literary editor. She accepted and began this new chapter in her life in 1919.

She quickly proved to have a keen eye for talent, introducing readers to Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Jean Toomer, Claude McKay, and other notable authors and poets of the era. Fauset also oversaw the African-American children’s magazine Brownies’ Book, which was also under the auspices of the NAACP and Du Bois. Published monthly from 1920 to 1921, it aimed to instill pride in African-American children about their history and heritage.

She also contributed her own writings — editorials, poetry, short stories, translations from the French of writings by black authors from Europe and Africa, as well as accounts of her worldwide travels. Such was her influence that Fauset has long been considered one of the “midwives” of the Harlem Renaissance literary movement.

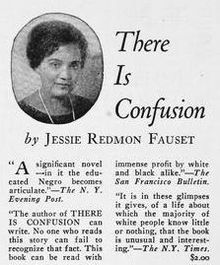

Fauset’s first novel, There is Confusion, was published in 1924, coming in the midst of her years as literary editor of The Crisis.

You might also like: 6 Poems by Jessie Redmon Fauset

A prolific poet and essayist

Fauset had the opportunity to publish her own work during her tenure atThe Crisis, which included editorials, stories, and poetry, all of which were appreciated by readers and literary critics. She edited and published the work of many noted Harlem Renaissance figures during her tenure at The Crisis; such was her influence that she’s considered one of the “midwives” of the Harlem Renaissance literary movement.

Some of the subject matter of her poetry was dark and rather grim, which can be sampled in 6 Poems by Jessie Redmon Fauset. “Oblivion” tells of a desire to lie in a deserted, neglected grave far from everyone and everything. Others, like “Dead Fires” and “La Vie C’est la Vie” seem rather fatalistic. It can be argued that the poems were an outlet for the frustration that this talented and capable woman had to endure because of race, but they allude to thwarted love and loneliness as well.

See also Literary Midwife: Jessie Redmon Fauset

More novels, and a return to teaching

After leaving The Crisis in 1926, Fauset wanted to work in publishing. Despite her experience and expertise, she was unable to find work because she was black. She even offered to work from home, but that didn’t help. She returned to teaching, and over the next several years wrote three more novels.

After 1924’s There is Confusion came Plum Bun (1928), The Chinaberry Tree (1931), and Comedy, American Style (1933). Up until the early 1920s, African-Americans were portrayed in stereotypical fashion by white authors in fiction. This inspired Fauset to write a novel portrayed black Americans in a middle-class settings. This was quite revolutionary at the time.

The educated, middle class characters in Fauset’s novels still experienced their share of prejudice, and like many works by black authors of the period, deal with themes of identity and passing.

Her novels received mixed reviews from African-American critics and colleagues. Some praised her for depictiing an aspect of black life that often didn’t see the light of print; others criticized her for an overly bourgeoise point of view. The Chinaberry Tree and Comedy: American Style were published in the depths of the Depression and weren’t as successful as her others. Her prolific pace of writing slowed considerably, and she virtually disappeared from literary circles.

Leaving the literary life to teach

Jessie Fauset seemed to have abandoned the literary life to pursue a teaching career. After her eight years at The Crisis, Fauset began to teach French at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx. She remained at the same school until her retirement in 1944.

You might also like Quotes by Jessie Redmon Fauset

A later-life marriage and legacy

Going back to 1929, Fauset was 47 years old when she married Herbert Harris, an insurance broker, in 1929. They remained together until his death in 1958. In her later years, she moved back to Philadelphia, where she died at age 79 in 1961.

A 2017 article in The New Yorker, The Forgotten Work of Jessie Redmon Fauset, quotes Cheryl A. Wall, author of Women of the Harlem Renaissance as saying, “I think we lose a bit of our literary history if we do not acknowledge the contributions of Jessie Fauset.” There’s ample evidence that Fauset felt the lack of appreciation for her contributions. Further, the article goes on to state, David Levering Lewis wrote of Fauset in When Harlem Was in Vogue: “There is no telling what she would have done had she been a man, given her first-rate mind and formidable efficiency at any task.”

Though she dropped out of the literary scene in the early 1930s, Jessie Fauset should be appreciated for her eye for talent, and supporting emerging voices from the Harlem Renaissance, many of whom are still read today. Though she may not have become as well known as some of those she nurtured and supported, it’s indisputable that she was one of the most important figures of the Harlem Renaissance.

More about Jessie Fauset on this site

6 Poems by Jessie Redmon Fauset

Literary Midwife: Jessie Redmon Fauset

Quotes by Jessie Redmon Fauset

Major works (novels)

There Is Confusion (1924)

Plum Bun: A Novel Without a Moral (1928)

The Chinaberry Tree (1931)

Comedy, American Style (1933)

Short stories, and essays (very select – her output of short works was enormous)

“Emmy” (1912):

“My House and a Glimpse of My Life Therein,” (1914)

“Double Trouble,” (1923)

“Impressions of the Second Pan-African Congress” (1921)

“What Europe Thought of the Pan-African Congress.” (1921)

More information

Wikipedia

Jessie Redmon Fauset entry at Perspectives in American Literature

Reader discussion of Fauset’s works on Goodreads

Jessie Redmon Fauset page on amazon.com

Articles, news, etc.

Fauset portrait by Laura Wheeler Waring at National Portrait Gallery

Jessie Fauset tells how to face despair

The Forgotten Work of Jessie Redmon Fauset

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Jessie Redmon Fauset appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.