Richard Gilbert's Blog, page 8

October 7, 2015

Memoir’s blazing psychic struggle

![[Mary Karr worships at the altar of reading and writing: “I give a rat’s ass, and my sole job is to help students fall in love with what I already worship . . .”]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1444366575i/16491105._SX540_.gif)

[Karr serves at the altar of reading and writing: “I give a rat’s ass, and my sole job is to help students fall in love with what I already worship . . .”]

Mary Karr nods to structure & obsesses over honesty in events, perspective, persona. She sees inner conflict as any story’s driver.

[T]he human heart in conflict with itself . . . alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.—William Faulkner, in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech

The Art of Memoir by Mary Karr. Harper, 229 pp.

Mary Karr’s credibility as an author of three memoirs and her devotion as a reader to the genre make The Art of Memoir absorbing. And sometimes surprising. Given how much writers discuss and obsess over structure, it’s striking that Karr devotes scant pages directly to it: one chapter of under two pages. Yet “On Book Structure and the Order of Information” is helpful and clarifying:

In terms of basic book shape, I’ve used the same approach in all three of mine: I start with a flash forward that shows what’s at stake emotionally for me over the course of the book, then tell the story in straightforward linear time.

So begins Karr, and you realize this is the template, at least for trade press memoirs. To take two current mega-bestselling examples: Jeannette Walls’s The Glass Castle (discussed) and Cheryl Strayed’s Wild (analyzed). Of course the two books showcase different strengths. I plundered Wild for ways to enhance my own book’s structure. Karr tells students to explore theirs by telling their stories to friends. Another tip is to write the little stories, which in time reveal the Big Story. For it’s your perspective that determines in the first place the story you structure:

Usually the big story seems simple: They were assholes. I was a saint. If you look at it ruthlessly, you may find the story was more like: I richly provoked them, and they became assholes; or, They were mostly assholes, but could be a lot of fun to be with; or, They were so sick and sad, they couldn’t help being assholes, the poor bastards; or, We took turns being assholes.

Thus Karr reiterates her own obsession: honesty. She’s been criticized in the past for protesting a bit much about memoirists not fabricating. Her practice of sharing pages with those mentioned seems unassailable, except on reflection. The revelation in The Art of Memoir is how she unites her factual concern with the thrilling imperative to find an authentic perspective/voice/persona. As she puts it:

Each great memoir lives or dies based 100 percent on voice. . . . The goal of a voice is to speak not with objective authority but with subjective curiosity.

Maybe that sounds easy. Just talk; be yourself. Karr tells how she broke the delete key on her computer and discarded 1,200 finished pages of her last memoir, the bestseller Lit (reviewed). All this because she couldn’t get right the perspective—and thus the portrayal—of her ex-husband (who refused to read drafts). In despair, she dreamed of him and herself when they were young and in love, and the key turned. She makes a powerful point here beyond the sturdy advice of employing a “dual persona”—presenting the perspective of you “now” and you “then.” Look, Karr says, the “now” you writing the story can forget without even realizing it who the “then” you actually was. How she loved, feared, yearned. This embodies the mysterious nature of memory, upon which memoir (and much of adult life) rests.

Karr admits to another fault that seems as intrinsic to writing. Which is wanting to seem somehow elevated—maybe smarter, classier, more artistic or virtuous than you feel or actually live. Now, she’s a celebrated poet and memoirist, a literary arts high priestess; but she’s also a sawed-off, scabby-kneed kid who grew in the ringworm belt. She’s gritty, a survivor. She can’t scrub her Texas twang from the page without harm. Yet her truth also includes being wicked smart, obscenely well read, a celebrated English professor, a deeply devout convert to Catholicism. Freeing her inner and past kid from the shadows of those adult attainments involves finding her again.

For Karr, as for me, this means first writing like we remember the sentences of smart, hyper-literary folk made us feel. Or of anyone who impressed us at an impressionable stage. But the power and beauty of the voices we recall probably isn’t the same as ours. Thus Karr circles back to her everlasting concern, authenticity. And how to find a suitable prose style for it. She dives through the past’s layers by locating what she calls “carnal” details—sensory impressions, often smells or textures—that bypass thought.

Maybe finding our own authentic perspective—our fair truth—is why we honor personal writing, if we do. Maybe this subset of literature is, in its beauty and failure, a scale model of the larger struggle to be awake and human. Karr’s implication throughout is that anyone’s inner conflict is her memoir’s real driving force:

The split self or inner conflict must manifest on the first pages and form the book’s thrust or through line—some journey toward the self’s overhaul by book’s end. However random or episodic a book seems, a blazing psychic struggle holds it together . . .

Although Karr’s family was epically dysfunctional, and therefore uniquely scarring, doesn’t any human endure profound inner rifts? Karr believes so: “We’re doomed to drama.” And whether we succeed or fail in memoir’s task of portraying our urge to connect, we cannot help but reveal ourselves in personal writing. Even (or especially) when we’re writing about others. Here’s Karr discussing Michael Herr’s self-portrait in Dispatches, a memoir that arose from Herr’s Vietnam reportage for Esquire:

The carnage, of course, sparks a natural urge toward moral outrage, a position that demands somebody be blamed. But blame makes deep compassion impossible, and in spiritual terms—which is what Herr grows into by book’s end, when he becomes a Buddhist—only compassion can bring about deep healing.

I found The Art of Memoir steadily interesting and Karr’s analysis of a few memoirs pleasantly quirky. Of course there’s that rascal Vladimir Nabokov’s classic Speak, Memory (reviewed)—thankfully with a touch of Karr Vinegar for his swollen ego. Near the end of the book, Karr offers three principles from other accomplished writers she has hounded:

Writing is painful, fun only for beginners or hacks.

With rare exceptions, good work comes only from revision.

The best revisers read books published before the current age.

There are other useful, less ouchy tips scattered amidst her analysis. But Karr has written not so much a how-to book as a companionable guide for kindred souls.

The post Memoir’s blazing psychic struggle appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

September 30, 2015

Mister Essay Guy

Dear Mister Essay Writer Guy: Advice and Confessions on Writing, Love, and Cannibals by Dinty W. Moore. Ten Speed Press,193 pp.

Dear Mister Essay Writer Guy,

Is there anything you won’t write about? Anything too private? (Would you admit it if there were?)

Dinah Lenny, Los Angeles, California

In Dear Mister Essay Writer Guy, Dinty W. Moore plays both straight man and humorist. He answers prominent creative nonfiction questioners—who pose ridiculous or book-length conundrums—and then he presents his more-or-less illustrative essay. Out of the absurd queries flow pervasive exaggeration, deft timing, addled answers, and wry storytelling. This sustained comedic performance glimmers with wisdom concerning life and the creation of art.

To state the obvious: Dear Mister Essay Writer Guy employs the structure of an advice column. Many now call such a borrowed structure a “hermit crab,” a term coined by Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola in Tell it Slant. Within Moore’s clever container, this mega hermit crab, are baby ones, such as essays presented as lists, and one on a cocktail napkin.

And then there’s his playful, celebrated experiment in form, “Mr. Plimpton’s Revenge,” a Google Maps essay on his encounters as a bumbling college student charged with escorting the befuddled literary lion. A personal favorite Moore works in is “Pulling Teeth, or Twenty Reasons Why My Daughter’s Turning Twenty Can’t Come Soon Enough”; he explains in his preceding answer that it’s all he could salvage from a failed book project on adolescent girls that consumed five years of hard labor (discussed previously).

In “Have You Learned Your Lesson, Amigo?” Moore appreciatively dissects the craft of two con artists who fleeced him on the street. This is reminiscent of his essay “The Comfortable Chair: Using Humor in Creative Nonfiction,” in Writing Creative Nonfiction, edited by Carolyn Forche and Philip Gerrard, which profiles an unctuous but irrepressible furniture salesman named Howie. Moore so admires professional competence that he’s amused by Howie and less than outraged by the latter pair of larcenous fellow travelers.

I may not be as objective as some, because I know Dinty Moore, but I was charmed and inspired by Dear Mister Essay Writer Guy. Charmed by its lighthearted spirit and inspired by how he used his writing practice and his sensibility to craft art in prose.

Moore answered a few questions by email about his new book:

[He abides: Dinty W. Moore.]

Question:

Once you had the idea for your approach did you feel you “had the book”? That sounds too reductive even as I ask it, but I wonder where in the process, here and elsewhere, that structure tends to appear for you? I sense it occurs initially for many writers, and then they refine it or alter it. Isn’t at least a fleeting conception of structure necessary to even begin writing something? Naturally this has implications for teaching.

The moment that I “get the book,” or see clearly what the external shape and inner gears might look like, has been different for every book I’ve written. Dear Mister Essay Writer Guy fell together more quickly than most, because the idea of an advice columnist approach, with individual questions from fellow essayists, pretty much determined how each chapter would play out. Beyond that, though, I still had to search for what I hope is – in the end — a graceful overall narrative arc, and I still had to fiddle around for months to see what essays might appear in which order.

A more common experience for me, both at the book level and the essay level, is to write pages and pages of material with no idea how the final shape might present itself, and then to only begin to discover my overall structure in draft six or ten.

Question:

Since we’re on craft here, I’ve always loved your sentences. Like buttah! They are so fluent and perfectly punctuated. You have said you struggle with first drafts but love revision and put essays through 20, 30, or even 50 drafts. I wonder what that means—in this age of computers writers can lose track. What do you call a draft? And most of all, What is happening in your own process of revision?

Thanks for the compliment. And you are correct that drafts are hard to count in the digital age. I can’t claim to have a perfectly accurate way of keeping track, but, for instance, when knocking out what might eventually become a twelve page essay, I will start with three or four pages, comb over those ten or fifteen times as I add another page, and another, and another, and when I’m starting to believe in the solidity of those earlier pages, I comb over the newer pages ten or fifteen times. And by combing over, I don’t mean correcting spelling and grammar, but rather pushing around sentences, drafting new sentences, adding and removing chunks of material, reordering thoughts. When I’ve reached the end of the essay, or what I imagine is in fact the proper end, I will start back at the beginning and go through from front to back, usually reading aloud to myself every page, still tightening, adding, subtracting, and reordering. That may constitute another ten or fifteen drafts, spread out over weeks. And then there are the final three or four drafts, where I am questioning each and every sentence for both musicality and meaning. Sometimes a sentence sounds good but in the end says little. Sometimes a sentence is important but refuses to sound good. I’ll chase those little devils to the end of the Earth.

Question:

You founded and edit Brevity, devoted to concise or flash essays of 750 words or fewer. Although you have admitted being challenged by this level of brevity yourself, your essays and books are nonetheless distinguished by a graceful less-is-more approach. To me, this has many virtues, including letting the fullness of implication bloom. What advice can you give those of us who have the tendency always to go long?

Going long is natural in early drafts. It takes sometimes sixteen sentences before you hit on the best way to say something. Allow yourself that freedom, but when you arrive at the right wording, the best image, the precise diction, go back and erase those fifteen sentences that led you there.

Question:

I laughed out loud reading Dear Mister Essay Writer Guy. Of course humor runs through your work—The Accidental Buddhist is funny too, as well as poignant and informative as you undertake a spiritual quest as our hapless stand-in and fellow baggage-carrying adult. Is humor a default setting for you, or do you sometimes start out very soberly and then see the humor? Although you seem to have a gift for humor, how have you honed it? Are there humorous writers you return to, enjoy, and learn from?

[Robert Benchley]

Oddly, my boyhood writing hero was the humorist Robert Benchley, a member of the Algonquin round table (along with Harpo Marx, Dorothy Parker, and Alexander Woollcott) back in the 1920s. I say “oddly” because not many people were still reading Benchley in the 1960s and 1970s, but I stumbled into his work at my public library and fell immediately in love with his whimsical riffs and curious formality. So I think he influences me still, as does Kurt Vonnegut.

Comedy is all about timing, and anticipation, so I spend a lot of time reading my drafts out loud and trying to “hear” how the humor plays, and I think deliberately about what one sentence might lead a reader to expect and how to perhaps up-end that expectation.

The truth is, I hate my voice on the page when I’m not being funny, or at least slightly wry. To my own ear, I sound sanctimonious, insincere, and whiney. Thus, a joke, always a joke. It drives my wife crazy.

Question:

Finally, and we may need to hear from Mister Essay Writer Guy here—because he seems smarter than you and certainly than me. What the heck is a lyric essay? To what extent are poet-voice and tambourines involved? Inquiring minds want to know. And don’t spare the horses, Guy.

A lyric essay is any essay written in French by a poet. This is different from the loric essay, which is an essay scratched in the dirt by a slow loris. The latter, you might imagine, take a long time to complete. And since lorises are nocturnal, meaning they are scratching out their essays in the total darkness of the Sri Lankan forest, the loric essay can be very hard to read. (My evidence: there are only two loric essays listed as “Notable” in this year’s Best American Essays.) Did you know, by the way, that female lorises bathe their young with allergenic saliva, a form of spit that is mildly toxic and discourages predators? This is true, and it is also a metaphor for the lyric essay, which, as Montaigne famously said, “can make one’s head spin so vigorously that one loses one’s stomach.” As for tambourines, Bob Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man” is a classic example of the lyric essay, because it uses the words “jingle jangle morning” and “magic swirlin’ ship.” Most lyric essays use these words, so in that way, they are easy to identify.

The post Mister Essay Guy appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

September 23, 2015

Guides to craft & style

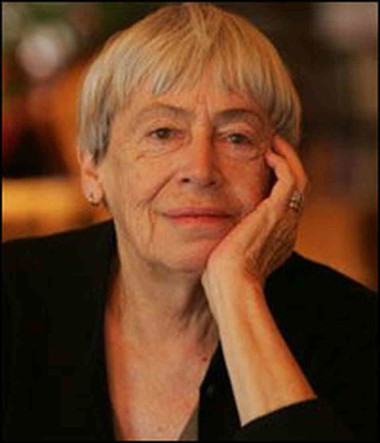

Steering the Craft, 2nd ed. A 21st-Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story by Ursula K. Le Guin. Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. First Mariner Books Edition 2015. 141 pp., $14.95 paperback. September 1, 2015.

The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century by Steven Pinker. Penguin Random House. 368 pp., $17.00 paperback. September 22, 2015.

Guest Review by Lanie Tankard

Writing has laws of perspective, of light and shade just as painting does, or music. If you are born knowing them, fine. If not, learn them. Then rearrange the rules to suit yourself.—Truman Capote, The Paris Review (interview)

[The classic usage guide.]

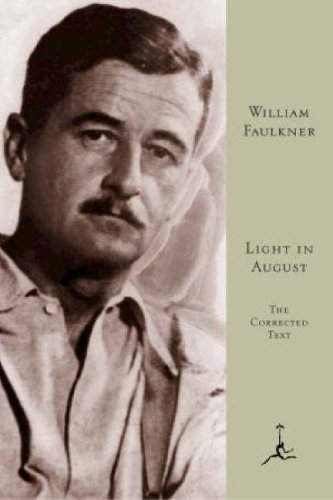

Autumn is a good time to put pen to paper, when one season restructures itself into another. Several respected writing guides have also emerged in altered forms this month. What both have in common is a recognized concept, outlined so clearly by Truman Capote in the quote above: Learn the rules before you break them.The most well-known rules have been found in Strunk & White’s classic, The Elements of Style. The fourth edition came out in 1999. Maira Kalman also illustrated a lovely version.

Ursula K. Le Guin and Steven Pinker compose words at far ends of the spectrum in their individual work, but both do it extremely well. In their guides discussed here, they each refer to Strunk & White. Le Guin says it’s the grammar manual she uses, calling it “honest, clear, funny, and useful,” but notes “an opposition movement” has arisen due to Strunk & White’s “implacable” views. Pinker claims a sense of “unease” and “discomfort” with such “immortal” rules that won’t bend, while acknowledging that much of Strunk & White is “as timeless as it is charming.”

The new second edition of Le Guin’s Steering the Craft embodies Strunk & White’s well-known maxim of omitting needless words. She completes this voyage in approximately 150 pages, trimming at least thirty from the first edition while shrinking the page size as well. It’s lighter, too, by seven ounces, and also available for Kindles.

What else is different from the 1998 book? The subtitle, for one thing. Before, it was: Exercises and Discussions on Story Writing for the Lone Navigator or the Mutinous Crew.

Now it’s: A 21st-Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story, foreshadowing the seventeen-year modernization found within.

In fact, it’s not the same book at all, as UKL completely revised and rewrote it “from stem to stern.” And fitting the motif, the publisher is now Mariner Books instead of Eighth Mountain Press.

[Ursula K. Le Guin.]

UKL stresses from the get-go: “it is not a book for beginners.” She addresses both fiction and nonfiction storytellers—and how to correct your course if you’ve run aground.Ten chapters cover topics such as the sound of writing, punctuation, grammar, sentence length, complex syntax, repetition, point of view, and voice. Each chapter ends with an intriguingly titled exercise. “Am I Saramago” assigns an activity sans punctuation. She addresses in an appendix how to set up a peer group workshop. A glossary includes terms like armature, dingbat, and pathetic fallacy.

UKL is widely known for her beloved science fiction, but she’s also written poetry and essays—not to mention a dynamite acceptance speech for the National Book Foundation’s 2014 Distinguished Contribution to American Letters award. I’ve long admired UKL’s thoughts on creativity expressed in her collection titled The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination.

Far more than a mere guidebook redux, the new Steering the Craft offers readers a visit with UKL herself and her lifetime of experience with words. The introduction alone is one of the purest examples of how excellent writing does not have to be wordy, for in its succinctness we hear her clear, calm voice in all its wisdom and wit.

Steering the Craft, 2nd ed., is a valuable sea chart for dedicated word crafters—call it Maker Faire for language. It’s brief. It’s brilliant. It’s UKL. I wish I could write like that.

[Steven Pinker.]

Steven Pinker’s new paperback edition of The Sense of Style, which first came out in hardback a year ago, is more than twice as long as UKL’s style guide but also contains artwork and cartoons. His six chapter titles range from “Good Writing” to “Telling Right from Wrong,” with several intriguing ones in between: “The Curse of Knowledge” and “The Arc of Coherence.” He includes a glossary, notes, and references at the end.Pinker writes from the perspective of experimental psychology, cognitive science, linguistics, and popular science. He is also chair of the Usage Panel of the American Heritage Dictionary. Here’s how the dictionary describes the assemblage: “The Usage Panel is a group of nearly 200 prominent scholars, creative writers, journalists, diplomats, and others in occupations requiring mastery of language. The Panelists are surveyed annually to gauge the acceptability of particular usage and grammatical constructions.” It’s fascinating to see the wide variety of wordsmiths included in this cluster.

In his prologue to The Sense of Style, Pinker stresses the idea that language “changes over time,” and pushes back against classic manuals such as Strunk & White’s in a forceful way. Yet he also advocates “reading more than one style guide.” Pinker concentrates on nonfiction, but notes “the explanations should be useful for fiction writers as well.”

This past summer, Pinker spoke about the future of writing in conversation with The Writer magazine. He pointed out, “There’s a lot of English that doesn’t follow rules.”

In an entertaining lecture last year sponsored by Skeptic Magazine, Pinker discussed his book, The Sense of Style, at length.

Channeling thoughts for others requires the use of language. Pausing to consider the craft can sharpen a writer’s pencil. Words have been my life as an editor. I tweak them for other people in various genres. Many books on the writing process line my shelves, along with a number of style manuals. Strunk & White has always been front and center. These two new volumes just earned space on my shelves as well.

Lanie Tankard is a freelance writer and editor in Austin, Texas. A member of the National Book Critics Circle and former production editor of Contemporary Psychology: A Journal of Reviews, she has also been an editorial writer for the Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville.

The post Guides to craft & style appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

September 2, 2015

Atoka Gold, Dad’s bull

[My father bred and registered this young bull; the photo was taken about 1954, a year before my birth on the ranch.]

A cane prods me to conjure Dad’s ranch days in a memoir essay.

Essays and stories and poems are built from leaps in thought and emotion and incident. They must unfold like a dream in which anything is possible.—Lee Martin, in his recent post on revision

And the reason he writes is to explain it all to himself, and the less he understands to begin with, the more he probably writes. And he takes his ununderstanding, whatever it is — the face of wealth, the collapse of his father’s pride, the misuses of love, hopeless poverty — he simply never gets over it.—Grace Paley, Just as I Thought

[My father, Charles C. Gilbert, began ranching after WWII.]

All summer I’ve been writing about cattle. My father’s bull Atoka Gold is a character, one of the purebred Herefords Dad raised during the early 1950s in California. What got me drafting a memoir essay was that in early June, when I brought my wife home from having surgery on her foot, I found a stockman’s cane among the umbrellas in our foyer.I dimly recalled receiving the cane when I was four. This was about 1959. We had resettled by then in southwestern Georgia, and Dad bought a bull from a nearby farmer, R.W. Jones Jr. Walter Jones was a prominent breeder of polled (naturally hornless) Herefords who has since become legendary. He gave me the cane. Finding it again sent me into our basement, where I found Dad’s framed color photograph of Atoka Gold.

[Lifesaver: knee scooter.]

I wove my memories of what surrounded the cane, me, Dad, and Atoka Gold together with my research into Mr. Jones and polled Herefords. I braided in my wife’s recuperation this summer. There’s always so much to explain, but good writing concerns more than one thing—so, great. Except my essay grew at one point to 27 pages. Rather long!In my mind from the start, the piece really illuminated the nature of memory, imagination, and story. But early readers wanted more about my relationship with my father. I resisted, having written so much before.

Here’s a few typical passages from Shepherd: A Memoir:

I wished I could tell Dad, gone ten years now, about all I was learning, about the advances in grass farming—new theories, forage species, tools—since he’d been a pioneer in pastoral agriculture in California and Georgia. He’d used weak, clunky electrical fences that constantly shorted out. Hence his desire to feed his cows efficiently on silage he made. His vision of paradise became vast hay and forage fields that surrounded a feedlot where his cattle awaited his deliveries. . . .

Growing up in Satellite Beach I watched him charm outsiders, clients he had to entertain for work or distant relatives, unaware of his solitary nature, who were passing through. His blue eyes sparkled with humor and a smile lit his face. The current of warmth that flowed from him at such times was palpable, the way the Gulf Stream off our beach coursed in a warm vein through the Atlantic’s murky coastal chop. Always he commanded respect, a natural leader, and when he dropped his sober mask he could be as charismatic as a movie star.

[R.W. “Walter” Jones, in the wheelchair, shakes the hand of a Coloradan making a historic purchase of Georgia cattle for the western range in 1965.]

I’d never written about the cane or our day at the Jones’s farm. Getting the first and subsequent drafts was an intense experience of trying to find the deeper story. Meanwhile in researching my essay I read a thick history of polled Herefords in America, talked to librarians in Georgia, questioned cattle experts. I learned what became of Mr. Jones, his son, and their famous linebred herd. I was shocked to see a photo of Walter Jones in a wheelchair—he’d been disabled by muscular dystrophy only a year after our visit.As always, I was schooled in the joys and pains of writing. Managing the herky-jerky composition process challenges me. There’s the excitement of the first draft, a blend of anxiety and pleasure as you break ground and turn up glittering arrowheads amid the clay gumbo. Then there’s seeing something in a present-day scene, and working in a new thread to realize its promise. Then there are second thoughts and additions. Then there’s a whole new version. Then someone points out the essay’s true organizing principle—hello latest new version. And finally you cut that whole present-day thread that took weeks of work.

Always I re-learn truisms. You do improve, yet writing isn’t easier. Maybe harder in all respects. What a paradox. What a struggle. I think you must enjoy making sentences—and in my case, complaining about it. My new essay, labored over for three months, still isn’t fit for the front pasture. But I see its potential. And it won’t be long before I look back and realize yet again that the process was the gift.

[A 1935 photo. In Georgia, my father bought Hereford bulls from R.W. Jones, of Leslie, who perpetuated the Victor Domino line. Dad bought a descendant of this bull from Mr. Jones.]

The post Atoka Gold, Dad’s bull appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

August 26, 2015

Odd woman

[Vivian Gornick, now 80, has just released her new memoir.]

Vivian Gornick’s new memoir charms via scenes, voice, anecdotes.

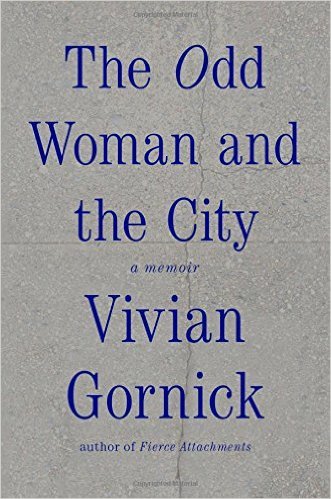

The Odd Woman and the City: A Memoir by Vivian Gornick. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 175 pp.

After I read The Odd Woman in the City, Vivian Gornick’s engaging new memoir, I turned back to the first page and began to read it again. How does it work so well? I wondered. A short book, at 175 pages, it is one long essay. Just series of short and flash essays, separated by space breaks, yet it moves.

Halfway through my second reading I saw the key. It was obvious, except I had read it so quickly before. So many scenes. Of course there’s her famous truth-telling persona, giving the low-down on herself and others. The text doesn’t rely on her opinions and confidences, on her attitude, however, but on her meeting and portraying others in dramatized action. If she’s not showing events unfold, she’s telling stories about herself, her circle, or some past denizen of the Big Apple. One vivid scene, pithy vignette, or juicy anecdote after another. Life before our eyes, as lived and perceived by this peppery child of the city. Though highly segmented, The Odd Woman and the City embodies the old-fashioned storytelling aesthetic Gornick recommends in The Situation and the Story (discussed).

Here her themes include friendship, especially in New York City, walking in the city, and encounters with strangers in the city. These are the confrontations of a lonely, solitary soul. A key thread in the book is her talks and walks with her gay friend Leonard. She portrays him as equally uncomfortable in his own skin, as similarly pessimistic, as another bleakly negative—yet captivating—personality. They can’t stand each other’s company more than once a week, but that meeting’s vital to them both. Her outrageous mother, whom she portrayed at length in her classic memoir Fierce Attachments (reviewed) also appears.

I admire writers I wouldn’t cross the street to hear speak, but I’d make an effort to see Gornick. She’s honest and unpretentious, though stuffed with art and culture, and full of news about her and others’ experience in the world. She could almost make you want to move to New York City, she so captures its gritty romance. Gornick and her own paradoxical nature hold the book together. Though she’s now 80, The Odd Woman and the City is set when she’s in her late fifties to early sixties. A realization she has about herself at age 60, and a mental change she undergoes as a result, is the book’s climax by virtue of placement and impact. This typically concise passage, some 800 words, was excerpted in its entirety by the New York Times.

Though that episode is weirdly unsettling, Gornick tells many funny stories on herself. And she is aware that, well, she’s odd. The latter is literally a reference to her feminism—she takes the term from George Gissing about feminists of an earlier era—but it alludes as well to her feeling of being broken. Like all writers (and people) she generalizes from her personal truths. This is why we read her but it’s also sometimes why I want to argue with her about her conclusions. As if she’s a friend.

[I liked Dwight Garner’s review in The New York Times; Gornick’s interview with Elaine Blaire for The Paris Review, “The Art of Memoir No. 2,” is riveting.]

The post Odd woman appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

August 19, 2015

Wrong word!

[Orderly & perfect: “Bookshelf #8” by Eli Helman.]

John McPhee’s “Draft No. 4” & my penance for misusing a word.

You cannot cross the narrow bridge of art carrying all its tools in your hands. Some you must leave behind …—Virginia Woolf, “The Narrow Bridge of Art,” Granite and Rainbow

But a writer had better take words. And fair command of them. I’ll never forget the day in high school when my English teacher accused me of plagiarism because of a word. I was 16 or 17 and had shown off by using “belies” in an essay. Since I was disrespectful to him, and acted like a simpering idiot in his class, he had good reason to suspect and dislike me. True to form, I laughed in his face. But that was long before the internet, which has made plagiarism—and catching it—easy. So he couldn’t do much except glare.

I’m sorry Mr. X!

I was just showing off, using a new word I’d learned. Partly I was flattered that he thought I had taken a professional’s work. Wow, though. Really just one word had tipped the balance. Diction does give us away. But I catch plagiarism these days because a student who slams together bald syntax suddenly turns in flowing, clause-laden, prose. Cheaters have the sense to change words they don’t understand.

Teachers’ and writers’ occasional admonitions against thesaurus use have always struck me as odd. They fear a student or rookie is going to use an overblown, polysyllabic word. One he doesn’t understand and that stands out from his mundane diction. I suppose that has happened once or twice. What using the thesaurus does for me, in contrast, is to remind me of old, plain, short words.

Counting syllables and picking the simplest word

Late in the years of working on my book, one day I noticed that I’d begun counting syllables. I’d pick the word, all else being equal, that had fewer. How this happened, I don’t know. It wasn’t as if I had just read an essay advising it. More like years of reading and writing had finally sunk in. In the first draft of my book, there had been plenty of fat words—“moreovers,” “neverthelesses,” and “howevers.” The latter isn’t disgusting but it’s not very colloquial, so there are only a couple left and many buts.

Recently I revisited John McPhee’s fine essay about diction, “Draft No. 4,” in the New Yorker. As I wrote here previously, one Thursday night in April of 2013, I told my wife about my notion of calling my blog The Fourth Draft. At that point I was well into my fifth year of blogging, and was tired of its name, Narrative. Also, my book’s fourth draft was its transforming draft. The only thing was, The Fourth Draft sounded like a minor-league baseball team or a microbrewery.

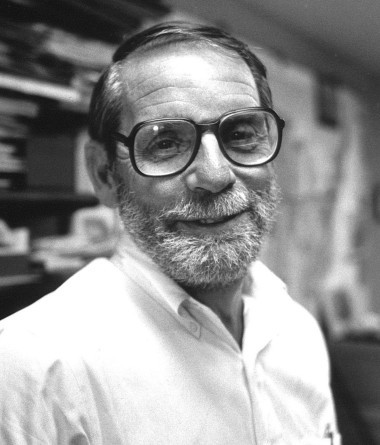

[John McPhee, master wordsmith.]

Then Friday morning, I sat down with my oatmeal and opened my new New Yorker to John McPhee’s “Draft No. 4.” So that’s what I renamed my blog. There was more poetry in his arrangement, plus it sounded like a small-batch bourbon.That was his essay’s legacy to me—I merely noted his practice, in his final draft, of drawing boxes around distinctive adjectives, nouns, and verbs. Then he goes through the dictionary, and then the thesaurus, confirming and checking options. In the tradition, he’s kind of weird about the thesaurus, though.

I wish I’d had the sense to adopt his word-boxing practice then. Probably there was time to do it for my book’s final draft—at least the book was a full year from publication then. My thesaurus work had involved mostly newer work in the book. I was hit or miss on words that I had written so many years before that they were almost invisible to me. Which of course is an implicit point of McPhee’s boxes.

I pick the wrong word: on the mortification of misuse

After Shepherd: A Memoir came out, a reader named Sarah Buchanan mentioned in a nice review for Goodreads that I had misused a word. Though she didn’t name the word, I knew instantly which one it was. So I must’ve known at some level that I had misused it! This is the most mortifying experience I have had as an author, which is saying something, given my babbling at one book event.

[“The Gravel Page” is collected here.]

Using the wrong word feels more undermining to my authority as an author than any other error I can think of. Even grammatical errors seem less damning because they can be chalked up to haste. Authors are in the larger sense poets, and what poet uses the wrong word? They don’t because they’re talented but also because they look up words. It’s part of a writer’s craft, which sets professionals apart from duffers. I can barely stand to think about my error. Humiliating. Totally.But amazingly, a few weeks ago I got the chance to fix it. What happened is that Barnes and Noble Booksellers placed an order for 266 copies. That brings the stock of the first printing low enough that, given anticipated reorders, my publisher is planning a reprint. And my editor has kindly let me correct my text for the new run.

Now you probably think it’s time for me to reveal the word. You have got to be kidding. As we used to say as kids, Wild horses couldn’t drag it out of me. I’m a fairly open person, and I reveal things in print that give some friends and loved ones the vapors, but of that I’m too ashamed. Read my book, and if you can find it, let me know and I’ll give you credit here. I may even reveal the word.

But don’t count on it.

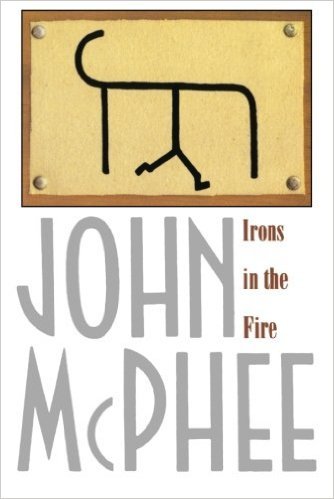

Read or download John McPhee’s famous “The Gravel Page Essay”

Speaking of John McPhee, you can read or download his essay about geological crime forensics, “The Gravel Page,” collected in his 1998 book Irons in the Fire. The New Yorker, where the essay first appeared, makes it available only to subscribers, but someone from North Dakota State University has uploaded a copy from the book, which of course we all should buy.

The post Wrong word! appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

August 13, 2015

A seer of art

In the best works of art, be they visual or verbal, the artist’s relationship to the subject matter is passionate and complex. All the artist’s skill and technique is focused by that passion and complexity.—Rachel Howard

[Sister Wendy Beckett, seer of art.]

Almost everyone consumes art in some form—it’s hard not to. Which means almost everyone has an opinion. Then there’s Sister Wendy. A nun who spends her days in silent, ego-less contemplation and prayer, the former English major emerges to take in the occasional art gallery. She has a gift, it turns out, for seeing deeply into paintings and their painters.A seer of art, Sister Wendy illuminates the role of the critic in educating and inspiring others. And in serving as an artistic partner, effectively a co-creator.

In the YouTube clip above, Wendy discusses “Stanley Spencer, Self portrait with Patricia Preece,” 1936. She comments that the woman’s hair is “unconvincing” though her pubic hair is “lovely and fluffy.” So the novelty effect here is high, but Wendy is no joke. She focuses on how “his art understands—he doesn’t understand,” and she leaves “Feeling vaguely unsatisfied, though I’m not sure why I should be.”

Wendy intuits and appreciates the artist’s effort. At the same time, she is so sensitive that she senses and analyzes where he may have in some way failed. She is positive even in this. What she is saying is Art is a handmade thing and never perfect. I think we love any work of art for its perfection but also for its heightened quality, its attempt at perfection. Art is handmade and there will be flaws. Perhaps the critic must help her audience see places that might be uneven, especially if they’re either a fault of soul or the dark side of a virtue.

I love sister Wendy. She shows how creative criticism can be. Her ability to receive and to feel is amazing and inspiring. Watch the video above!

Ernest Hemingway’s Green Hills of Africa seen anew

Speaking of insight into art, there’s a thrilling retrospective consideration of Ernest Hemingway’s Green Hills of Africa memoir in the current New Yorker, “Hemingway as the Godfather of Long Form,” by Richard Brody. I read everything by and about Hemingway when I was a teenager, really studied him and his aesthetic. In middle age, I turned against him for the egomaniac blowhard he became, and which I feel hurt his art. Yet there was perfection in his early stories. And the first chapter of A Farewell to Arms—only two pages—is heartbreakingly lovely.

Brody’s piece helps me separate some of the distressing content in Green Hills of Africa from what he was trying to do in terms of advanced literary technique. So here is another instance where a critic can help an audience see and reconsider an artist.

I thought another recent masterpiece of critical insight in the New Yorker was Adam Gropnik’s review of Harper Lee’s new novel, Go Set a Watchman.

Walker Percy on estrangement

[Clarity is hard—”Signpost #2″ by Eli Helman.]

And speaking of insightful Catholics, one of my favorite writers is Walker Percy. Walter Isaacson discusses him brilliantly in “Walker Percy’s Theory of Hurricanes,” part of the recent New York Times Sunday Book Review’s reconsideration of Hurricane Katrina and its effects. The upshot appears to be that people who went through the harrowing experience of Katrinia in New Orleans remain closer, or at least less estranged from each other.Isaacson writes about Percy’s observation that most people become happy when a hurricane threatens. Here Isaacson explores Percy’s portrayal of it in one of my favorite novels, The Last Gentleman (discussed), in which protagonist Will Barrett weathers a hurricane with a girl named Midge:

Driving through Connecticut, they are caught in a Northeastern hurricane and seek shelter at a diner. When the wind breaks a window, they help the counter attendant board it up. “Midge and the counterman,” Percy writes, “were very happy. The hurricane blew away the sad, noxious particles which befoul the sorrowful old Eastern sky and Midge no longer felt obliged to keep her face stiff. They were able to talk. It was best of all when the hurricane’s eye came with its so-called ominous stillness. It was not ominous. Everything was yellow and still and charged up with value.

Percy is so good on this matter of estrangement—man from himself and from others. I am not sure he ever got completely at the cause of the malaise. But he accurately diagnosed the condition and implied the cure: connection. A true conundrum of the egoistic self vs. the group. Since I see religion as about community and God as arising in connection, his work always resonates for me.

There’s that feature in The New York Times Book Review where they ask writers what three literary heroes they’d like to resurrect for dinner-table talk. Walker Percy is on my list—he’d be kinder and more fun than his Catholic compatriot Flannery O’Connor for sure. Virginia Woolf has to be there—Lord what a sensibility. And probably William Faulkner—veiled though he might be. On second thought, Eudora Welty? She’s so warm and recognizably normal.

Anyway, the South would be well represented. America’s Ireland, after all, that likewise hurt plenty into poetry. Speaking of that, W.B. Yeats and James Joyce are obvious options for my list, but I fear they’d just come off bat-shit crazy.

William Faulkner on connection

Might as well drag in Bill Faulkner. In my favorite Faulkner novel, the almost-endless Light in August, he portrays the disgraced Rev. Gail Hightower listening to nearby music emanating from his former church:

Sunday evening prayer meeting. It seemed to him always that at that hour man approaches nearest of all to God, nearer than at any other hour of all the seven days. Then alone, of all church gatherings, is there something of that peace which is the promise and the end of the church. The mind and the heart purged then, if it is ever to be; the week and its whatever disasters finished and summed and expiated by the stern and formal fury of the morning service; the next week and its whatever disasters not yet born, the heart quiet now for a little while beneath the cool soft blowing of faith and hope.

[“Stanley Spencer, Self portrait with Patricia Preece,” 1936.]

The post A seer of art appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

July 1, 2015

Memoir or personal essay?

[Stealth memoir: subject reveals self.]

When I first started teaching essay writing I was a reflexive splitter or at least a classifier. In practice this means one who strains to distinguish between a personal essay and a memoir essay. Of course, the memoir is a personal essay. But for students, I felt compelled to distinguish between them in the way Sue Silverman does in “The Meandering River: An Overview of the Subgenres of Creative Nonfiction.”As Silverman says, “Instead of the memoirist’s thorough examination of self, soul, or psyche, the personal essayist usually explores one facet of the self within a larger social context.” Drawing such distinctions in the varied nonfiction genre can be important for teachers, depending on the class, and especially for college freshmen. Teachers had better be clear about what they want. As an editor, too, I sometimes find that pinning down an essay’s lineage can be helpful. For instance, the personal essayist does employ a persona—and who is telling the story and why is important—but she or he isn’t the main point. Whereas in memoir, s/he is.

But drawing such distinctions can also be crazy-making.

In theory I love the personal essay that focuses more on the Bigger Topic—as in The New Yorker’s essayistic reportage or in Leslie Jamison’s hot new collection The Empathy Exams. But in practice, when I buy books I favor memoirs or memoiristic essay collections. Editors of literary journals say they want more personal essays, but like everyone else they end up wanting also to know more about the writer.

Maybe partly because I was an “objective” journalist for so long, and felt my writerly hands were tied, I am drawn to memoir as a reader and writer. And also because I spent seven years writing a memoir and spinning off from it, as adaptations or outtakes, mostly memoiristic essays. Recently I enjoyed Sue Silverman’s stealth memoir, The Pat Boone Fan Club: My Life as a White Anglo-Saxon Jew, about her lifelong obsession with Pat Boone. I find thrilling the way her life is refracted through the odd prism of Mr. Boone.

Two flash essays, one memoir & one personal

[Grace Paley.]

Grace Paley’s “Mother” feels perfect as a flash essay of only 420 words—a memoir flash essay. Though like Amy Hempel’s “In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson is Buried,” it was published it as a short story, in The Collected Stories, it is sometimes taught as nonfiction because it feels so autobiographical and hews to her known biography. Of course, if it were dragged out we’d want to know more about the writer—in that family crucible and “now, as she makes sense and reflects—but its perfection is that it isn’t dragged out.What a beautiful little story/essay. As Dylan sang, “Behind everything beautiful there’s been some kind of pain.” But an artist who can use her pain, as Paley seems to have done here, has made something more of it: art. Its echo of “Then she died” is heartbreaking and also a precise instrument of revelation: the perfect, stunned, everlasting reality of grief. Her mother is gone forever except in the writer’s endless loop of guilt and memory. Maybe all the writer can do is accept her loss, whether she can or not. But that mystery underscores how much she’s doing by implication—Verlyn Klinkenborg makes a key point in A Few Short Sentences About Writing (reviewed) about how powerful implication is. But it’s also a little essay that moves readers all around in time, and plays with time, as it also shifts persona from then to now.

I share my admiration for “Mother” with another concise gem, Ian Frazer’s flash essay “Crazy Horse”—361 words spun-off from Great Plains into a personal essay. I have heard great things about that book and now want to read it just to see how or if he develops his persona. Who is this amusing guy, so passionate about a Native American tragic hero? “Crazy Horse” is stamped with something that seems to typify more the personal essay than the memoir: it is told very much from the writer’s “now”; we don’t see him as a little boy, at least here, with prints of plains Indians pinned to his bedroom wall. Or whatever.

An essay collection on the memoiristic end of the scale that I love and have taught several times is Such a Life, by Lee Martin (reviewed). He writes about himself as a kid, as a troubled teen, and as an adult. He grew up on a poor southern Illinois farm, in a suburb of Chicago, and then back in farm country but living in a hick town—with a father maimed and rageful from a farming accident. Lee got—and often provoked—the brunt of his wrath. As a novelist, he is a master at writing in scenes, but in their midst he’ll step in from the present to reflect, giving his essay two voices, experiences, and perspectives. It’s richly layered.

Recently I binged on a favorite personal essayist, David Sedaris, reading two of his collections after listening on CD to him read one of them. He is so funny and strikes such a great balance between self and topic. Some of his essays are very memoiristic, but many are topical—recountings of his experiences and observations—made interesting by his quirky persona and hilarious responses and odd behavior. I would love to emulate the way he uses his sensibility, much in the way poets do, to write his way through life. Everything is material. The past and the present are interwoven. Like Frazier’s essay, his main stance is in the writer’s now, regaling us. He asks for our laughter at his past self, not pity, and his own eyes are amused unto mocking.

[Baldwin: good luck classifying his great essay.]

For my money—and back to the classification dilemma—the greatest American essay is “Notes of a Native Son,” by James Baldwin (discussed on this blog before), title essay of his book by that name. For one thing, it deals with American’s greatest topic, race. And it portrays race and, more to the point, racism, vividly in Baldwin’s lived experience. It’s also a mesmerizing portrait of his seemingly immortal but suddenly dead father, an Old Testament prophet of a preacher warped by racism. And Baldwin now sees that the old man—“ingrown, like a toenail”—has passed his burden onto him but without a clue how to prevent his bitterness from becoming Baldwin’s.I’m not the only teacher driven half mad trying to decide whether to tell students “Notes of a Native Son” is a personal essay or a memoir. Well, it’s both. Or neither. Artists, or at least works of art, transcend classification. Which is why I like Rachel Howard’s generous and forgiving lumping for an online class I’m taking this summer through Stanford: “We will define the personal essay broadly, as any shorter piece of nonfiction writing that investigates personal experience in order to arrive at new insight.”

The post Memoir or personal essay? appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

June 22, 2015

Poetry of Light in August

William Faulkner’s prose—stamped with his poetic lineage—shines.

I’m a failed poet. Maybe every novelist wants to write poetry first, finds he can’t and then tries the short story which is the most demanding form after poetry. And failing at that, only then does he take up novel writing. —William Faulkner to The Paris Review

William Faulkner began as a poet, and it shows. He adores words. His sentences shine as well in Light in August, sometimes referred to as his greatest novel. Sometimes it’s also called his most accessible great one, the last bead on his string of masterpieces between 1929 and 1932: Sartoris, The Sound and the Fury, As I Lay Dying, Sanctuary. I remember Light in August fondly from college. I wrote mostly poetry then, and realized only recently that I had based a character, in an epic poem I was slaving over at night, upon the novel’s immortal Lena Grove.

Rereading it this summer, I’m struck by how sure a writer Faulkner was. His sentences thrill and inspire. Then again, there are enough of those Faulkneresque doozies to keep you on your toes. The story is simple. Lena Grove, poor and naïve, very pregnant but indomitable, a girl from nowhere Alabama, tracks her feckless beau to Mississippi. He works as a sawdust shoveler at a sawmill with a fellow named Joe Christmas, a bootlegger, soon-to-be murderer, and all-around tortured soul. Suffice it to say, troubles ensue.

His great sentences, whether poetic or plain, arise from Faulkner’s own observations, from his immersion in his fictive story, and from his channeling of some characters’ thoughts. They include these:

Nothing can look quite as lonely as a big man going along an empty street.

Even a mare horse is a kind of man.

Lying in the single blanket upon the loosely planked floor of the sagging and gloomy cavern acrid with the thin dust of departed hay and faintly ammoniac with that breathless desertion of old stables, he could see through the shutterless window in the eastern wall the primrose sky and the high, pale morning star full of summer.

Two punctuation idiosyncrasies (which do have a logic): he uses nary an apostrophe in contractions, so can’t is cant; he runs together compound modifiers that normally would be hyphenated—though he’s inconsistent, neither correctly hyphenating nor oddly conjoining “back street restaurant,” and eventually he forgets the mannerism altogether.

Another thing that makes reading Light in August interesting is that, since reading it decades ago, I revisit periodically Annie Dillard’s Living by Fiction (reviewed). Dillard, patron saint of this blog, also started as a poet—maybe helpful in pegging Faulkner. She places him as a modernist who employs “fine” rather than “plain” prose. The latter is spare and visual, while fine prose celebrates the beauty of language, strewing about metaphors and adjectives, even adverbs, Dillard says, and “traffics in parallel structures and repetitions.”

Dillard deconstructs each style’s strengths and weaknesses. Among especially “fine-style” sentences in Light in August, here he’s writing about a Civil-War-haunted (because his grandfather died in the conflict) defrocked preacher, Gail Hightower:

The house, the study, is dark behind him, and he is waiting for that instant when all light has failed out of the sky and it would be night save for that faint light which daygrainaried leaf and grass blade reluctant suspire, making still a little light on earth though night itself has come.

Wow, but, well. Daygranaried leaf? I know what a leaf is and a granary—and day. So this is a leaf that drifted into a grain storage facility? The phrase’s brilliant, odd, specific gravity daygranaries the mind. I actually picture the yellow-mottled desiccated and warty leaf in an old whitewashed corncrib I knew. Then there’s “grass blade reluctant suspire.” Suspire means to sigh, or breathe. So a blade of grass sighed, albeit reluctantly.

. . . I can’t even. I recall how, when I was a kid, I used to call him “a purely rhetorical writer,” meaning he conjures with smoke and mirrors and clanking chains. Yet he feels his world so deeply that by dint of effort he wills it lopsidedly into being.

I love and brood upon Dillard’s theories. For instance, there’s the irony of the “submissive” plain style being practiced by Faulkner’s macho rival, the personally overbearing Ernest Hemingway whose prose can be so window-pane clear and lovely. The more “dominating” fine style was employed by Faulkner, a reticent man.

Though his style was showy, to me Faulkner seems to submit to and channel, prostrate before it, the South’s tragic history and its rotten-at-the-core lost dreams of grandeur. Maybe his artistic submission to his region gave him the courage to conjure and dominate it in prose.

[There is a decent short biography of Faulkner on the Ole Miss web site. His Nobel Prize banquet speech is always worth re-reading; there’s even a recorded snippet of his rushed and almost indecipherable delivery.]

The post Poetry of Light in August appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

Light in August

William Faulkner’s prose—stamped with his poetic lineage—shines.

I’m a failed poet. Maybe every novelist wants to write poetry first, finds he can’t and then tries the short story which is the most demanding form after poetry. And failing at that, only then does he take up novel writing. —William Faulkner to The Paris Review

William Faulkner began as a poet, and it shows. He adores words. His sentences shine as well in Light in August, sometimes referred to as his greatest novel. Sometimes it’s also called his most accessible great one, the last bead on his string of masterpieces between 1929 and 1932: Sartoris, The Sound and the Fury, As I Lay Dying, Sanctuary. I remember Light in August fondly from college. I wrote mostly poetry then, and realized only recently that I had based a character, in an epic poem I was slaving over at night, after the novel’s immortal Lena Grove.

Rereading it this summer, I’m struck by how sure a writer Faulkner was. His sentences thrill and inspire. Then again, there are enough of those Faulkneresque doozies to keep you on your toes. The story is simple. Lena Grove, poor and naïve, very pregnant but indomitable, a girl from nowhere Alabama, tracks her feckless beau to Mississippi. He works as a sawdust shoveler at a sawmill with a fellow named Joe Christmas, a bootlegger, soon-to-be murderer, and all-around tortured soul. Suffice it to say, troubles ensue.

Great sentences, some seemingly based on Faulkner’s observations, others seemingly arising from his immersion in his fictive story, include these:

Nothing can look quite as lonely as a big man going along an empty street.

Even a mare horse is a kind of man.

Lying in the single blanket upon the loosely planked floor of the sagging and gloomy cavern acrid with the thin dust of departed hay and faintly ammoniac with that breathless desertion of old stables, he could see through the shutterless window in the eastern wall the primrose sky and the high, pale morning star full of summer.

Two punctuation idiosyncrasies (which do have a logic): he uses nary an apostrophe in contractions, so can’t is cant; he runs together compound modifiers that normally would be hyphenated—though he’s inconsistent, neither correctly hyphenating nor oddly conjoining “back street restaurant,” and eventually he forgets the mannerism altogether.

Another thing that makes reading Light in August interesting is that, since reading it decades ago, I revisit periodically Annie Dillard’s Living by Fiction (reviewed). Dillard, patron saint of this blog, also started as a poet—maybe helpful in pegging Faulkner. She places him as a modernist who employs “fine” rather than “plain” prose. The latter is spare and visual, while fine prose celebrates the beauty of language, strewing about metaphors and adjectives, even adverbs, Dillard says, and “traffics in parallel structures and repetitions.”

Dillard deconstructs each style’s strengths and weaknesses. Among especially “fine-style” sentences in Light in August, here he’s writing about a Civil-War-haunted (because his grandfather died in the conflict) defrocked preacher, Gail Hightower:

The house, the study, is dark behind him, and he is waiting for that instant when all light has failed out of the sky and it would be night save for that faint light which daygrainaried leaf and grass blade reluctant suspire, making still a little light on earth though night itself has come.

Wow, but, well. Daygranaried leaf? I know what a leaf is and a granary—and day. So this is a leaf that drifted into a grain storage facility? The phrase’s brilliant, odd, specific gravity daygranaries the mind. I actually picture the yellow-mottled desiccated and warty leaf in an old whitewashed corncrib I knew. Then there’s “grass blade reluctant suspire.” Suspire means to sigh, or breathe. So a blade of grass sighed, albeit reluctantly.

. . . I can’t even. I recall how, when I was a kid, I used to call him “a purely rhetorical writer,” meaning he conjures with smoke and mirrors and clanking chains. Yet he feels his world so deeply that by dint of effort he wills it lopsidedly into being.

I love and brood upon Dillard’s theories. For instance, there’s the irony of the “submissive” plain style being practiced by Faulkner’s macho rival, the personally overbearing Ernest Hemingway whose prose can be so window-pane clear and lovely. The more “dominating” fine style was employed by Faulkner, a reticent man.

Though his style was showy, to me Faulkner seems to submit to and channel, prostrate before it, the South’s tragic history and its rotten-at-the-core lost dreams of grandeur. Maybe his artistic submission to his region gave him the courage to conjure and dominate in prose.

[There is a decent biography of Faulkner on the Ole Miss web site. His Nobel Prize banquet speech is always worth re-reading; there’s even a recorded snippet of his rushed and almost indecipherable delivery.]

The post Light in August appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

![[Steven Pinker.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1443183666i/16330716.jpg)