Richard Gilbert's Blog, page 10

March 27, 2015

Perils of persona 2.0

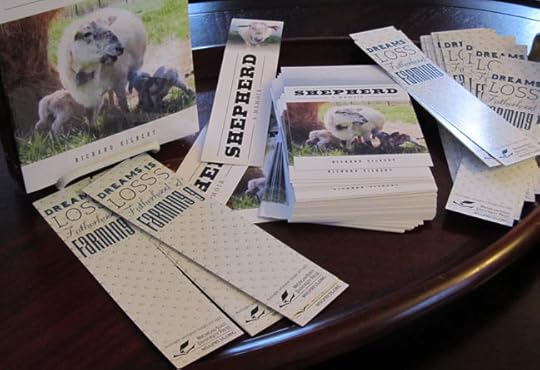

[A book group in Binghamton, New York, and I discuss Shepherd: A Memoir via Skype.]

Portraying yourself and family in memoir & creative nonfiction.

There will be time, there will be time

To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet;

—T.S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

1. When readers dislike the memoirist as a character

[Freckles, then . . . ]

In life we present ourselves to others amidst their constant feedback. Body language, words, eyes that twinkle or harden. Our micro adjustments to emotional currents are constant. We’re bred to send and receive signals. On the page, though, how do you know how you’re coming across?I’ve been pondering this, as I do when I teach or write. But also because of recent events. In the first, I Skyped with Jane’s Book Group that had read my memoir. They gathered at RiverRead Books, a fine independent bookstore in downtown Binghamton, New York.

I got the sense—maybe a memoirist’s paranoia—that, like most book groups, they read mostly fiction. Which may partly explain one nice lady’s keen frustration with me as a character in the book. And look: Here’s that obtuse character in the flesh. Or at least on the computer screen. A reckoning was in order. She wanted to know how I could have done it, ignored good sense and my wife and torn down a charming little cabin on our farm? All because I didn’t want to use farmland to build a house? When we didn’t even build the house after all?

Facing this sweet, smiling, frustrated woman, I was speechless. Her issue with me then felt so personal now. My thoughts raced. I created your love for that cabin. I created that dork who tore it down. I wanted you to be frustrated with me then.

As the Bible says, humans are “born to trouble as surely as sparks fly upward.” Literature is about trouble. You can play trouble for comedy or drama, but baby you play it.

For her, it appeared, I had failed to bring off memoir’s signature quality, the dual persona. There’s the character in the midst of the action then and there’s the writer now, making sense of it and reflecting. The now aspect can be very overt: “Now I see what a stubborn ass I was.” Or it can be much more subtle, a change in voice, a shift in tone, the use of softer cues like “remembering those days.” One of the reasons that persona is such a central issue for memoirists is that readers judge memoirists, in a way they don’t novelists. Somehow the memoirist must anticipate readers’ likely response to his past and address their judgments.

An explosive reaction to Brandon Schrand’s memoir Works Cited

[Schrand: then or now?]

I’ve just fielded an explosion over persona in my freshman honors class at Otterbein University. The book in question was Works Cited: An Alphabetical Odyssey of Mayhem and Misbehavior (reviewed) by Brandon R. Schrand. He structures his story by listing alphabetically the authors he was reading as he came to manhood, from youth and high school through graduate school, in the form of an MLA Works Cited list. He presents himself as a mess who took seven years to earn his undergraduate degree. And yet, wow, quite the reader. Even in jail.Schrand’s younger self was promiscuous, had a drinking problem, sponged off his partner while lusting after other women, and had an almost-physical emotional affair even when he was married and a father. I doubt a memoirist’s persona ever works for everyone, but these seemed trip wires for my students. We also noted what a shadowy figure his wife is in comparison to women he bedded or chased. Maybe she wanted it that way?

I had felt that Schrand did address his past implicitly by portraying his younger self as a bozo. But seeing his persona through my students’ eyes made me less certain. And it made me wonder whether his innovative structure, which is why I love and why I taught the book, queered his mea culpa as it fractured (otherwise pleasingly) the portrayal of his own redemptive narrative arc. My students read Schrand at a point in the semester when they felt confident and more likely to criticize. Works Cited provoked teachable moments regarding persona, and it inspired students’ own experiments with borrowed structures (“Hermit crabs”) and segmented ones, and for that I took comfort.

Then they further surprised me by urging me to have future classes read Works Cited.

“I still like Schrand’s book,” said a guy appalled by Schrand’s “sexist attitudes” toward women.

“I know people like that,” said a girl who also rose to the book’s defense. “He’s a jerk but he’s honest. I think it’s good to read a writer we don’t like.”

In their interpretation, Schrand hadn’t failed to bring off a retrospective persona to limn his younger self—he’d accurately portrayed himself then and now as a clod. I don’t know the man, so I can’t say what he’s like. But I admire his honesty in Works Cited, and I believe he changed—this memoir being Exhibit A. The only way to test my theory that his somewhat implicit dual persona succeeds (for adults) is to have a class of returning students or a gimlet-eyed book group read it and see what other geezers say. In that case, my hypothesis is that how he’s interpreted will depend largely on how many of the women readers once dated their own boy Schrands.

It’s about the honesty, stupid

[Exquisite—except for teens?]

Eighteen-year-olds are a tough, somewhat unpredictable crowd. It’s always a challenge to come up with a slate of memoirs that both they and I will adore. There’s a difference between teen/twentysomething taste and middle-aged taste. I’ve found there’s even a gap between memoirs freshmen and upperclassmen prefer.And I’ve noticed that these freshmen, sensitized to persona by my harping on it, are apt to resent a writer for trying too hard to sell his interpretation of his past self. Though their fondness for any particular memoir has varied, the most popular so far have been Alison Smith’s Name All the Animals () and Darin Strauss’s Half a Life (reviewed). They loved Name All the Animals not only because they could relate to its same-age heroine but because of her very subtle “now” persona. Hers is the classic “reads like a novel” memoir. In contrast, Strauss employs a dominant “now” stance, but the plight of his younger self—who accidentally killed a high school classmate—makes that distance seem necessary as well as rendering the horror more palatable. At least he’s together enough now to write about it.

My biggest disappointment this semester hasn’t been Works Cited, which at least woke up students, but their lukewarm reaction to Monica Wood’s exquisite When We Were the Kennedys: A Memoir from Mexico, Maine. Although she portrays herself as a child, in the wake of her father’s death and then after the Kennedy assassination, her dominant persona, the writer looking back, may be too middle-aged for eighteen year olds. And I’ve seen this blah reaction before with a boomer-era memoir; students seemingly can’t relate to those times—or are sick of boomer nostalgia. Persona is complex and subtle yet has a big effect in all this.

This week as I read their own second memoir essays of the semester, the persona issue dropped into further context for me. Their memoirs varied greatly in subject and in treatment, comic or dramatic, but shared the quality of feeling emotionally honest. And that honesty seemed so brave. I could not help but admire it. And I felt surprisingly moved—once again—by their life stories.

When you are emotionally honest you make yourself vulnerable. Readers notice. My students’ work in the wake of our readings underscored this signature aspect of memoir: its demand that the writer be and seem honest in telling his story. Whether the writer “now” is implicit or overt, imperative to the genre is the truth-telling narrator. And maybe the larger point is that authenticity is an imperative for our species, a key value embedded in our DNA.

We expect emotional honesty from our partners and closest friends. When a writer, making art from her experience, is emotionally honest with unknown readers, she’s offering a gift to the world.

[Next: 2. When memoirists worry about portraying family members.]

March 11, 2015

Teaching memoir, ver. 3.0

[James Baldwin, author of America’s greatest essay, “Notes of a Native Son.”]

Structuring a memoir-writing class by focusing on essay structures.

I blogged last year about teaching memoir by emphasizing the essentials of persona, scene, and structure. Except now I list and teach scene first because students get the macro aspects of voice faster—essentially persona, the writer now, talking to us about the past—but many need help understanding how and why to dramatize, to make scenes. So SPS: scene, persona, structure. From the start, this gives us a shared vocabulary. To understand scene, you must understand summary—and often students who have written vivid summary think they’ve written scene.

That’s the thing about teaching writing: you must teach so much at once. You hope that by providing good models, students will emulate more than the stated focus. And they do. Nothing teaches the teacher, however, like teaching. Last year, my college juniors and seniors in “Writing Life Stories: The Power of Narrative” said they wished that I’d emphasized structures earlier. So this time I have.

Structure, the shaped mode of presentation, excites students. They see how it can help them crack open their material. They grasp that it can cut plodding “and then” or unnecessary backstory. Halfway through the semester, already I’ve shown them: braiding (Jo Ann Beard’s “The Fourth State of Matter” always amazes everyone); framing (a favorite new essay is Kelly Sundberg’s “The Sharp Point in the Middle”); collage (“Documents” by Charles D’Ambrosio); and Hermit Crabs, among them Pir Rothenberg’s funny “Woman Told,” made from women’s OkCupid dating profiles, which also shows the closeness of nonfiction and poetry.

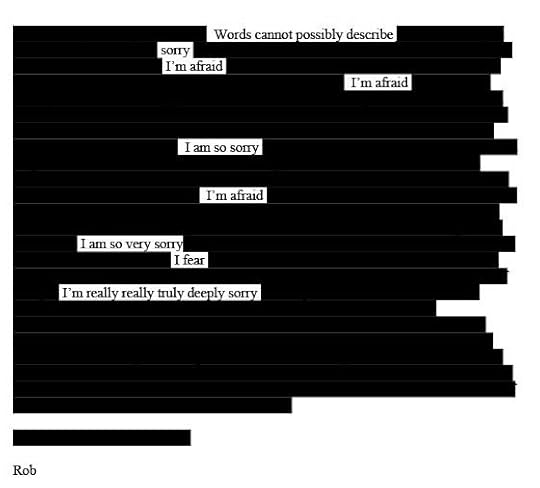

There’s an amazing, disquieting new Hermit Crab at Diagram, Brooke Juliet Wonders’s “Self Erasure,” which redacts her lover’s suicide note:

[A page of Brooke Juliet Wonders’s essay “Self Erasure.”]

Next we’re looking at segmentation, probably reading Jonathan Lethem’s “The Beards,” Lee Martin’s “All Those Father’s That Night,” and Dinty W. Moore’s “Son of Mr. Green Jeans,” the latter a Hermit Crab as well, taking as it does an alphabetical list for its structure.Emphasizing essay structures has caused me to realize that I can organize my entire class by examining different writing structures. After a month or so focusing on the Big Three of scene, persona, and structure, we can examine a structure a week. Then we can turn, say, to a theme that allows me to have them read more great essays. Under the “The Pains and Joys of Others” we can read: the greatest American essay, James Baldwin’s immortal “Notes of a Native Son,” which also allows us to revisit the framed structure; and Brian Doyle’s powerful flash essay “Leap,” about 9/11; and Ryan Van Meter’s “If You Knew Then What I Know Now,” which is also an instance of second-person address.

We could finish the semester with something like “You in Real Time,” which might include Moore’s witty essay about his name, “Mick on the Make,” Jill Christman’s deft “Family Portrait,” which as a bonus is in third person, and Elizabeth Kavitsky’s twentysomething self-portrait “Winter Just Melted.” I could have them read Brenda Miller’s flash essay “Swerve” as well. (I must figure out whether to consider separately flash essays, which intrigue students almost as much as structure does.)

Matching stated weekly themes with example essays can be crazy-making. But what inclines me to try it is how the stated theme plus examples can support my weekly writing prompt. Under “The Pains and Joys of Others,” I could give them a standby, a prompt to write about an odd person they’ve known; for “You in Real Time” I could ask them to write about “Me, Now,” as in Kavitsky’s essay about her post-college drift into ordinary adulthood and her lesbian sexuality. Or have them write an apology to someone, whether sincere or, as in “Swerve,” facetious and dripping with scorn. (Most undergraduates take the latter option, which is fun—and makes the heartfelt exception doubly affecting.)

To appreciate my breakthrough, it might help to know that my “Writing Life Stories” class meets in person once a week and that the syllabus lists a different theme for each week. For instance, Week 11 is titled “Dramatic tension, foreshadowing cont.,” and Week 12 is listed as “Language, Tone, Style, Humor.” At the time I slapped such headings on the syllabus I suppose I thought that so saying meant so doing. But, in practice, those categories are at once too weighty and too vague for me. Or maybe it’s just that they don’t work as organizing principles, to me too recipe-ish—“stir in some foreshadowing and add a pinch of humor”—when I tend to underscore the overall container for a story, its structure, and then turn to elements of its content.

As in writing, in teaching there’s what you plan and what you find yourself doing.

Maybe it boils down simply to this: I can’t wait to share certain essays with students. By categorizing such essays—according to structure, from chronological to collage, and by shared themes—I form the spine of the class and space my favorite readings throughout the semester.

Of course this plan will, in some sense, fail. But it will help the course and me as a teacher to evolve.

February 16, 2015

Excavating the margins

[Getty Images-Peter Macdiarmid.]

Ander Monson’s library ephemera spur provocative literary essays.

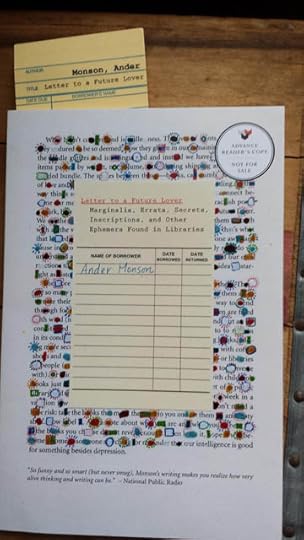

Letter to a Future Lover: Marginalia, Errata, Secrets, Inscriptions, and Other Ephemera Found in Libraries by Ander Monson. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Graywolf Press, $22.00 hardcover (176 pages).

Guest Review by Lanie Tankard

“Pardon the egg salad stains, but I’m in love.”

[An advance copy. Photo by Donna Seaman.]

Ander Monson has written a book that’s still got me contemplating. He’s an intriguing thinker and he displays his pondering prowess to good effect in his latest work, Letters to a Future Lover: Marginalia, Errata, Secrets, Inscriptions, and Other Ephemera Found in Libraries.In this collection of literary essays, Monson frames books as repositories of both past and future history—not via their printed content but rather through the traces of former readers and librarians left within when they interacted with the volumes. Much like an excited archaeologist embarking on a dig, Monson gleefully examines even the most minute scribblings and materials deposited by past lovers of the books he encounters in various libraries.

As he inspects, he uses each occasion as a springboard for his thoughts—one minute he’s deep into a soliloquy about a note he found written in a book margin and before you know it, he’s segued almost imperceptibly into human loss of a heartbreaking magnitude. Monson fuses Vladimir Nabokov, Walter Benjamin, Italo Calvino, Virginia Woolf, or Julio Cortázar into his musings with the same ease as he brings in gaming consoles such as Atari Jaguar, TI–99/4A, or Vectrex Arcade System.

The novel People of the Book by Geraldine Brooks was based on a true story involving age-old smidgens left behind in an ancient volume, but Letter to a Future Lover is not fiction. Monson weaves in his own memories throughout to form a unique style of meandering memoir that embellishes the main recurring theme of reader/book interface. During his reminiscences, he digresses on various tangents such as the difference between actual memories (perhaps residing in the coffee rings and chipped wood on that old table in your grandmother’s attic) contrasted with artificial memories (such as those created in a factory on a “distressed” table sold in an upscale home-furnishings store).

[Ander Monson.]

Monson has also written a novel (Other Electricities), two books of poetry (Vacationland and The Available World), and two other collections of essays (Neck Deep and Other Predicaments and Vanishing Point: Not a Memoir). I reviewed Vanishing Point, a finalist for the 2010 National Book Critics Circle Award in criticism, for the 100 Memoirs blog.I suppose you could read Letter to a Future Lover quickly, but I don’t recommend that approach. I like to savor ideas myself. And leaving no stone unturned, Monson delves into such topics as libraries, reading, sentences, pixels, codex, myth, tweets, writing, cataloguing, stamp and coin collections, structure, Words with Friends, and archives—wrapping them in classy metaphors brimming at times with such brilliance they forced me to pause and allow the notions he tossed out to play around for a while in my mind. I chuckled while Monson went to town with literary devices like synecdoche and metonymy.

Do you read with pen in hand, making marginal notes as if talking to the author? Are you fervently attracted to every single little facet of books as a concept? Have you ever been curious about palimpsest? If you enter a library archive with the same awe you reserve for Notre Dame Cathedral Paris…then oh my, will Ander Monson’s Letter to a Future Lover reel you in.

The slim volume certainly has me sitting here deliberating how a future book lover a thousand years hence might view my egg salad stains.

Lanie Tankard is a freelance writer and editor in Austin, Texas. A member of the National Book Critics Circle and former production editor of Contemporary Psychology: A Journal of Reviews, she has also been an editorial writer for the Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville.

[“Reading Lesson” by Sandra Kuck.]

February 4, 2015

The wiser narrator

![[Otterbein University’s iconic Towers Hall. My room this winter is on the ground floor, just right of center.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1423363743i/13612538._SX540_.jpg)

[Towers Hall, Otterbein. My room is on the ground floor, just right of center.]

The retrospective view, in life as in Alison Smith’s great memoir

I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve read Name All the Animals, by Alison Smith, one of my favorite memoirs. I four years ago, and this semester I’m teaching it to a class of honors freshmen students under a coming-of-age memoirs theme. At the time of my review, one of the story’s most striking aspects to me was its scenic quality. I wrote, “There isn’t much authorial distance: narrated by a bereft girl, with scant mature perspective, the story has a poignant immediacy.”

How I disagree now with my (slightly) younger self! Though Smith is a scenic and subtle writer whose story breathes on the page, and is deeply embedded in her teenage life, there’s no pretense that a high school girl wrote this. Smith’s voice palpably changes at times (as when she fills us in on her parents’ early lives), and there are even more overt cues, including the standby “writer-at-her-desk now” move, “I remember.”

Why did I not see this? I suppose I got lost in the story, plus at the time I was trying to enhance the scenic quality of my own Shepherd: A Memoir. One’s response to a book is, to a large degree, a selfie. You, now. Which is why and how I learned not to teach certain great memoirs to undergraduates. They have to find a book’s characters relatable. Maybe one of the few advantages of age is that we can relate to a wider swath of humanity.

On Tuesday, when my freshmen and I had our first talk about Name All the Animals, with a class of juniors and seniors I discussed Jo Ann Beard’s astonishing essay “The Fourth State of Matter.” Now there’s a memoir essay that seems to flagrantly violate the aesthetic principle that, in literary memoir, the writer must not merely present the story as it happened then but must reflect on its meaning for her now.

In their own work, I’ve urged my upper-classmen to work in the middle of the scene-to-exposition/reflection continuum. So, in a sense, Beard’s essay seemed a risky model. I read to them a passage of Sven Birkerts tying himself in knots in The Art of Time in Memoir (reviewed) over Beard’s essay:

Missing almost entirely from Beard’s rendered scenes and situations is the reflective voice that I have suggested is the sine qua non of the genre, vital for establishing the crucial tension of perspective. But Beard’s mode of presentation compensates, for this; she makes up the deficit through her structural artifice of juxtaposing two or more distinct time lines to create a comparable tension of “then and now” or “then and then.”

If you’ve read and re-read Beard’s braided narrative, you’ll agree with Birkerts’ explanation, and momentarily you’ll almost be able to understand it.

“There are no rules in art,” I told the upperclassmen. “Only rules of thumb.”

•

[Alison and Roy Smith.]

Tonight’s forecast is for snow and a low of 11 degrees.“It’s the depth of winter,” I told my freshmen the other day, “but by the time the term ends, it’ll be spring.”

“Yeah,” one girl said, “but it’ll still be cold.”

“We’ll have warm days—some days will feel like it’s already summer.”

This is it, the wisdom of age, the retrospective view? The promise that warmth will return? They take winter far less personally than I do. Maybe inane reassurances are part and parcel of what I’ve come to offer.

I think of my students as kids, but I call them guys. “Okay, guys, let’s look . . .” On Tuesdays and Thursdays, as we ponder our tales of dangerous youth in iconic Towers Hall, second-semester freshmen faces look back at me. Thirteen girls and one boy. Their various editions of Name All the Animals bristle with sticky notes.

Last Thursday an icy rain fell too late to cancel school, and between about 8 and 10 o’clock walking was treacherous. One member of our honors seminar fell climbing the steps to her first class and hit her head. I crept as if on eggshells, going to the library at 9, but I almost went down six times.

Yet already there’s been a palpable change. Though we’ve just passed through a frigid period, the ground forever icy and snowy, you can feel the solar energy gathering its power. On Tuesday, a couple of students and I struggled to get the room’s blinds down, jamming ourselves into arched gothic window frames to subdue crooked louvers, so I could show a film clip related to Name All the Animals.

At home as at school, rooms fill newly with light. It always happens—this I know—yet always it seems news worth noting, this yearly planetary miracle. Here comes the sun.

[Alison Smith reading a short story or maybe a concise essay.]

December 24, 2014

Tidings & sightings

[Bear? Wild hog? This black creature lurks near our grandbaby’s abode in Virginia.]

Upon the birth of our grandchild, a menacing Beast emerges.

I.

[Kathy Jane Knight-Gilbert.]

A child’s birth ushers into being a new, wondrous, and blessedly humbling era. Which my wife Kathy and I seem more consciously aware of as we celebrate the arrival of our first grandchild, Kathy Jane Knight-Gilbert. “We named her for two strong women,” our daughter announced from her hospital bed. Claire and David honored Kathy—surprise!—and his grandmother. Kathy Jane was born Monday, December 15. Adding to the merriment, within days she received a letter provisionally admitting her to my and Kathy’s place of employment, Otterbein University, Class of 2032.And then a mysterious, ugly, and clearly wicked Creature appeared from the woods nearby.

Kathy Jane’s namesake spied the beast first. Just after first light, returning from a foraging expedition to WalMart, Granny Kathy saw “It” quartering across a clearing near the house. She telephoned me, but I was in the shower. So she snapped a few pictures with her iPhone and burst into the house. I got a quick glimpse of the beast before it disappeared into the woods.

“I think it’s a bear,” David declared, looking at the blurry photo. He’d seen a bruin crossing the road, a few miles away, the previous weekend.

“I think it’s a hog,” I opined, pointing to the rather long snout and rather skinny legs.

“WTF?” our son texted, on his way to us in old Virginia from his garret in California.

“It looks like what I saw go onto our neighbor’s deck,” David added.

“That sounds more like a bear,” I conceded. Picturing a hog climbing steps was difficult, throwing the weight of available evidence toward a bear.

Little did we know, Kathy and I would soon encounter the creature in broad daylight on a roadside hardly a stone’s throw away from the babe in her crib. But if there’s one thing I’ve learned this week from watching antediluvian sitcom reruns on antenna-only MeTV in the guest quarters, it’s that plot is a red herring.

Stuff happens when you throw a group of people together in a situation: in a hapless North Carolina mountain town; in a hotel at a sleepy mostly female railroad stop; on a ranch peopled solely by bachelors beside Lake Tahoe; on the New Mexico frontier, where a widower was uncommonly attached to his lever-action rifle. It’s basically the same stuff happening over and over; it’s the different players who lend interest and relevance.

Plot exits to reveal character. The question for us at the time, vis-a-vis the Creature, was, Is this a sitcom or a drama in which we find ourselves?

II.

Actually the only question in my and Kathy’s minds as we held Little Kathy was, Who are you? Because there has never been a cuter or more inscrutable child. Her expressions range from Picasso pensive to Winston Churchill profound to Chaplin slapstick joyous. Since she is largely silent and sleeping, she’s ripe for projection.

“I want her to major in musical theatre at Otterbein,” I declared.

“You want to major in musical theatre at Otterbein,” Kathy corrected.

Fair enough. But I’ll have to reincarnate, because I can’t sing or dance. Whereas Little Kathy needs only: to receive lots of dance lessons from her parents; to inherit a voice from her father’s side of the family; and to take piano lessons to go with her long, elegant fingers.

Her mother raised an eyebrow. She herself had promptly quit dance lessons at a tender age, declaring, “I don’t want to be dancing a flower!” At that age Claire had bigger ambitions anyway: to become the first woman president.

“She can still become president,” I wheedled. “By then we will have had a female president, but not one who was a musical theatre major.”

“I’m not sure I want her going into politics,” Claire ruled.

“David,” I appealed to her father, “look at these fingers!”

To sing and dance your way through college, practicing art at a high level at age 18, what could be better? Plus she could minor in physics, write poetry, and be a fierce little soccer star too.

III.

[Smokey Lonesome in Fried Green Tomatoes.]

In WalMart, Kathy had spotted a man wearing a shirt emblazoned with “Someone special calls me Peepaw.”For some reason, I had not anticipated being asked to pick my grandparent name. I thought you were Grandfather or Grandmother, and the kid butchered it into something pronounceable and cute.

But no.

While I dithered, Kathy had pounced. Referencing an Italian folk tale about a woman named Strega Nona she’d read to our kids, plus Claire’s first sentence and command to her mother—“No monie no!”—Kathy picked Nona.

Awakening a few mornings before we left for Virginia, my grandparent name floated into my cerebral cortex. Smokey Lonesome. He’s a character in the novel and movie Fried Green Tomatoes, though why I wanted to be named after an alcoholic hobo mystified everyone.

In the fullness of time, Little Kathy will learn old Moke’s literary provenance. And, being a brilliant musical theatre major, she will grasp that Smokey Lonesome, who got bashed on the noggin trying to protect Miss Ruth’s baby from evil, represented pure love.

So when Nona and Mokie saw the Creature lurking nigh yet again, Mokie braced himself for battle. Then they saw it was only a stray dog—ugly, oddly shaped, and furtive. But harmless. So they laughed.

[David Knight introduces Kathy to The Goats.]

December 22, 2014

Icy Nordic memories

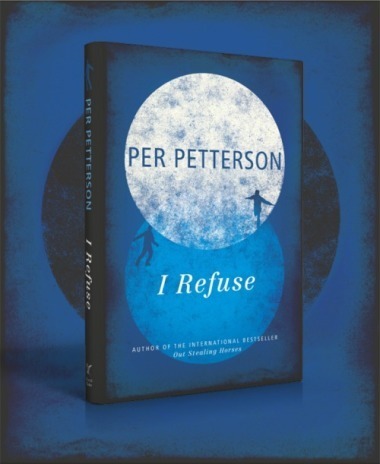

I Refuse by Per Petterson. Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press, $24.00 hardcover (296 pages), April 7, 2015. Translator: Don Bartlett. Cover Design: Kyle G. Hunter

Guest Review by Lanie Tankard

But that’s life. That’s what you learn from; when things happen.

—Per Petterson, Out Stealing Horses

Per Petterson, long loved by Norwegian readers, has become well respected outside the Scandinavian region as his books are rendered in other tongues. The prize-winning 2007 novel Out Stealing Horses was tagged one of that year’s Top Ten by both the New York Times and TIME Magazine, and has been translated into forty-nine languages. He’s written other fiction, but it’s been several years since the last book.

Until now. Number Nine, I Refuse, is due out in April—and it’s a gem.

The concise title symbolizes Petterson’s latest work. It’s short, as is the novel at less than 300 pages. The two-word label is clean, almost Spartan, conveying details through brevity—like most of the sentences found within. Yet one still encounters protracted sentences that reverberate like a drum, steadily provoking a sense of dread. One such powerful linguistic unit containing 156 words focuses on memory.

Rights to the novel have been sold in sixteen countries. For the American edition, designer Kyle G. Hunter used a single row of black leafless trees ringing a frozen pond to slash the utterly white cover in half. One must look closely to find two dark silhouettes trudging toward one another on its surface. Or, are they? The title’s succinct words appear in red against this cold backdrop, almost as a semaphore to signal the reader about what’s inside this lean Nordic tale.

And what’s there is urgently subtle, as a childhood incident on an icy pond races through the neural pathways of the two main characters, Jim and Tom, after a chance meeting as adults. Per Petterson melts away that memory, lodged in the ice crystals of their minds for several decades, in unhurried fashion. He nudges synapses and tweaks neurotransmitters for the protagonists, allowing their retained impressions of troubled childhoods to bubble forth. It’s almost as if Petterson were conducting a musical composition, employing his pen as a baton.

What the author begins as a duet, then, gently broadens. A minor third emerges—the voice of Tom’s sister, Siri. Next an oratorio develops as various parental figures with individual chapters create a chorus. The theme “I refuse” starts to appear in variations.

[His “sentences reverberate like a drum, steadily provoking a sense of dread.”]

To anticipate a totally somber presentation of the serious events in this novel, however, is to miscalculate Petterson’s control of his fictional world. More than once I found myself unexpectedly laughing out loud as he displayed wry brilliant humor in the depiction of certain scenes, such as a doctor in a hospital or tension á la Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde.Fishing analogies appear, conveying equivalence between independent parts. “White frozen sheets” hanging out to dry resemble flags of surrender.

Petterson has chosen each word in this story for a reason. Needless ones have been whittled away. When the author’s voice reaches the reader’s mind, it has been honed to an invisible sharpness that compels listening. The fact that he eschews question marks somehow enhances this sensation.

I Refuse contemplates the passage of time, the power of memories, the mystery of disappearances, and the residue of encounters long past. How many things can a person refuse to do? What are the repercussions of refusal? Jean-Paul Sartre wrote in The Devil and the Good Lord: “I am no longer sure of anything. If I satiate my desires, I sin but I deliver myself from them; if I refuse to satisfy them, they infect the whole soul.”

Refusal can indicate unwillingness, not accepting something, or denial. Petterson’s title almost evokes the succinct “J’accuse!” heading of Émile Zola’s open newspaper letter to French authorities. Both terse designations bear the sound of outrage and accusation against someone more powerful—Zola’s in a loud way and Petterson’s in a soft way.

“I refuse” is jeg nekter in Norwegian. It’s me niego in Spanish. In German, it becomes three words, ich weigere mich, as it does in Mongolian: bi khog khayagdal. And yet, no matter how that idea is uttered, a refuser balks, stopping a forward trajectory.

Per Petterson, in his own inimitable and minimalistic manner, quietly examines the long-lasting effects of childhood events in adult lives and the different paths people choose when they refuse to be victims. I Refuse is bound to be one of 2015’s fiction jewels.

Don Bartlett translated I Refuse from the Norwegian. He also did a 2012 translation of Petterson’s 1992 novel It’s Fine By Me. And his recent translation of Petterson’s 1987 debut, a short-story collection called Ashes in My Mouth, Sand in My Shoes, is due out from Graywolf the same day as I Refuse.

Lanie Tankard is a freelance writer and editor in Austin, Texas. A member of the National Book Critics Circle and former production editor of Contemporary Psychology: A Journal of Reviews, she has also been an editorial writer for the Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville.

November 17, 2014

DFW on CNF

. . . personal essays and memoirs, profiles, nature and travel writing, narrative essays, observational or descriptive essays, general-interest technical writing, argumentative or idea-based essays, general-interest criticism, literary journalism, and so on.—David Foster Wallace’s syllabus definition of creative nonfiction

Protean [proh-tee-uh n] adjective: 1.readily assuming different forms or characters; extremely variable.—Dictionary.com

As a teacher and writer of nonfiction, I devoured the late David Foster Wallace’s recently released creative nonfiction syllabus. Salon, which published it, called the document “mind-blowing,” evidently referring to its tough-love language.

In this blueprint for a night class he taught at Pomona College once a week in Spring 2008—so roughly six months before his death, presumably when he was already suffering from deep depression—Wallace prosecutes a rigorous, distilled aesthetic. He builds toward it in his opening “Description of Class,” which notes that “nonfiction” means it corresponds to real affairs but that creative “signifies that some goal(s) other than sheer truthfulness motivates the writer and informs her work.”

This purpose may be “to interest readers, or to instruct them, or to entertain them, to move or persuade, to edify, to redeem, to amuse, to get readers to look more closely at or think more deeply about something that’s worth their attention. . . or some combination(s) of these.’’ He continues, going deeper:

Creative also suggests that this kind of nonfiction tends to bear traces of its own artificing; the essay’s author usually wants us to see and understand her as the text’s maker. This does not, however, mean that an essayist’s main goal is simply to “share” or “express herself” or whatever feel-good term you might have got taught in high school. In the grown-up world, creative nonfiction is not expressive writing but rather communicative writing. And an axiom of communicative writing is that the reader does not automatically care about you (the writer), nor does she find you fascinating as a person, nor does she feel a deep natural interest in the same things that interest you. The reader, in fact, will feel about you, your subject, and your essay only what your written words themselves induce her to feel.

The apparent acid that Salon responded to in “whatever feel-good term you might have got taught in high school,” I read, instead, as an attempt to emphasize his own hard-won understanding. It’s not just that along the line Wallace got his ears bored off by some undergraduates’ essays, though there’s a whiff of that. In the recent Quack This Way: David Foster Wallace and Bryan A. Garner Talk Language and Writing, Wallace discusses how in college he “snapped to it perhaps late,” thanks to his teachers, that the world “doesn’t care about you. You want it to? Make it. Make it care” (33-34).

Also he’s trying to woo his students by inviting them into his world’s inner sanctum. We will learn what only the pros know. His brief for art over experience is a key aesthetic principle of literary nonfiction. Since such prose is often initially motivated by deeply personal experiences and feelings, which often it also does express, it can be a revelation to writers to learn that that’s not enough.

As I read it, Wallace is not forbidding heartfelt personal writing but simply saying that the fact that the experience was personal or cathartic for the writer isn’t sufficient. High levels of craft, which themselves bespeak authorial distance and shaping, must be brought to bear. Attention must be paid . . . to the reader.

As he explains:

Part of the grades you receive on written work in this course will depend on each document’s presentation. Presentation here means evidence of care, of facility in written English, and of empathy for your readers. The essays you submit for group discussion need to be carefully proofread and edited for typos, misspellings, garbled constructions, and basic errors in usage and/or punctuation. “Creative” or not, E183D is an upper-division writing class, and work that appears sloppy or semiliterate will not be accepted for credit: you’ll have to redo the piece and turn it back in, and there will be a grade penalty — a really severe one if it happens more than once.

David Foster Wallace’s list of essays for student reading

For a class session early in the semester his students were to read Jo Ann Beard’s “Werner,” Stephen Elliott’s “Where I Slept,” George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language,” and Donna Steiner’s “Cold.” For the next class they were to read David Gessner’s “Learning to Surf,” Kathryn Harrison’s “The Forest of Memory,” Hester Kaplan’s “The Private Life of Skin,” and George Saunders’s “The Braindead Megaphone.”

If this seems light reading for a semester’s writing class, recall that, because his English 183 class is small, he’s running it as one big workshop group. Each student must read, edit, and write about several classmate essays per workshop session. As far as I can tell, after the introductory class and two on these readings—so after about three weeks to get the students writing—the class’s three-hour weekly sessions were spent discussing student work.

By having them read these essays at the start, he was both giving his students sophisticated models and filling in until their essays came rolling in. In the same way that he asked them to respond to their classmates later, he gave his students this assignment for each group of essays:

Pick one of these essays, pretend that it’s been written and distributed by an E183D colleague, and write a practice letter of response to it, being as specific and helpful as possible in detailing your impressions and reactions and suggestions for how the essay might be improved.

The genius writer as yeoman teacher

Wallace’s syllabus also interested me for how it reveals the brilliant novelist and essayist as a beleaguered teacher of undergraduates. This class was limited to—praise the Lord!—twelve students. At most institutions, I imagine, the cap would be 16. As writing classes edge above 16 and reach 20 or more students, things get much less personal for everyone. Some students feel they can hide. Instructors simply cannot give each writer as much attention.

So, in prepping his artisanal class, it is amusing to see Wallace practicing the jiu-jitsu common to all teachers who author syllabi. It’s a loss of innocence, what you learn you must include. But it’s also good and necessary housekeeping. Here’s his statement on attendance:

For obvious reasons, you’re required to attend every class. An absence will be excused only under extraordinary circumstances. Having more than one excused absence, and any unexcused ones at all, will result in a lowered final grade. After the first two weeks, chronic or flagrant tardiness will count as an unexcused absence.

That Wallace had to write the next line is rather heartbreaking but it proves he did teach undergraduates:

All assigned work needs to be totally completed by the time class starts.

I can’t remember students in my day using broken typewriter ribbons as excuses, though surely some did; I vaguely recall faded type from frayed ribbons. Now the technological aspect of writing is vast. Especially if work is shared electronically, but there’s also more formatting—the old typesetter’s job—even for hard copies. For both student and teacher, much more knowledge and tools are required. I spend a huge amount of time teaching things like proper formatting in Microsoft Word, including telling students repeatedly to notice and override Word’s annoying default of putting extra space between paragraphs. (Fine for the web, but . . . )

Students have many more real and convenient excuses for late work, including trying to use a web-browsing device as their workhorse computer, lacking compatible software, or composing essays on thumb drives. Periodically I’m asked by students to email them essays because they can’t find drafts in their computers or have lost the thumb drives they trusted them to. And always, real but foreseeable (to an adult) printer pitfalls—including dry ink cartridges and empty paper trays—crossbreed with immaturity and procrastination. Technology both permits sharing and provides excuses that drive teachers half mad.

Here is Wallace’s valiant, doomed effort to head off the latter:

There are no “extensions” in workshop-type classes; your deadlines are obligations to [12] other adults. Finish editing and revising far enough ahead of time that you can accommodate computer or printer snafus.

Each of his students was allotted three workshops. Except some, he knew, would want one fewer or need one more. Here he tries to engage students in the logistical aspects of workshopping—as if they’ll remember or care that he’ll have to juggle like a demon to accommodate custom experiences:

This is not impossible, but it makes for tricky scheduling — you need to confer with me individually (and soon) if you wish to submit something other than the normal three pieces.

Although a teacher labors to plug the holes and scare the hardened criminals, he learns repeatedly that he’s fair game. And that even good students don’t know the impact of their messy lives on a teacher with dozens of other students to tend and hundreds of pages to grade. Sometimes he imagines good students puzzling over syllabus invective spurred by the sins of their unknown miscreant forebears. As Dave says, it’s tricky.

One of the ways Wallace handles these paradoxes of the teacher’s role is with humor. He’s spoofing his authority even as he establishes it. It’s clear he’s no ogre. Telling his students “you’re insane” if you don’t own a good dictionary and a usage dictionary makes the serious ones feel special—they’ll buy one or both. By all accounts, he was uncommonly attentive and kind to students.

Any student with half a brain got the humor and smelled the fudge factor here:

Attendance, Quality & Quantity of Participation, Effort, Improvement, Alacrity of Carriage, Etc. = 20%.

I’m surprised only that he didn’t list “deportment,” but surely that’s included under Alacrity of Carriage.

November 10, 2014

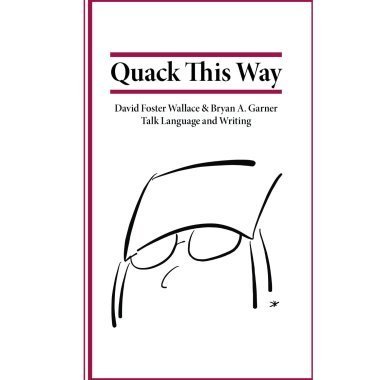

Judith Kitchen’s noticing

Distance and Direction by Judith Kitchen. Coffee House Press, 230 pp.

[Judith Kitchen. Uncredited image at Gwarlingo.]

Hearing on Sunday of Judith Kitchen’s death, I felt a pang of loss. I’ve recently become a fan. Last June I read her Brevity essay “On the Farm,” a consideration of two archival photographs—a girl with chickens, a child with her father in a cornfield—and modeled an essay on it. And I read her celebrated essay “Blue,” a segmented lyric that moves from her father’s, mother’s, and brother’s blue eyes to her children’s to her high school geometry class. Then, in August, I read her essay collection that opens with “Blue,” Distance and Direction. It’s one of my top books of 2014.Kitchen’s essays here verge on poetry. Moments from memory; how memory works. The world’s beauty. Her father’s image and his memory everywhere. And grief, loss, regret. Might you wish for more connective tissue? Maybe. Yet how neat to be given bright shards instead of always the mirror’s entire, dutiful brown frame too. Did Distance and Direction wholly achieve the author’s aim as art. Yes, surely. These essays make you want to be more alive yourself—to notice as much—and to write with such clarity and meaning.

Here’s a paragraph just before a space break in “Displacement”:

If it is going to rain, it will rain the cold, spiraling rain of the seacoast. Blinding rain that will wash in from the sea in a shroud of fog. The day will close down. The streets will be dark with the words of the sea, dark with the blood that has yet to be shed in a time that surely will be.

Note the rhythms, the simple diction, the precision. The passage’s culmination, that mysterious final sentence, soars beyond mortal power—streets “dark with the words of the sea” and rising to the epic grandeur and ominous mystery of those streets “dark with the blood that has yet to be shed in a time that surely will be.”

I’m most challenged by what seems within my range—the first sentence: “If it is going to rain, it will rain the cold, spiraling rain of the seacoast”—because it is made of what she has noticed. What she must have noticed in life to make that sentence. The way she saw the seacoast’s rain spiral. You must fully live, or have lived, in some specific place, to write such a sentence. You must have looked and you must have seen. She was a great noticer, or maybe magnetized, as it were, by her writing.

Here is more of Kitchen’s noticing, from “Direction”:

The train across Germany was old, with a steam engine, and it reminded me of childhood, waiting for my grandmother to come down the little flight of steps, the puff of steam escaping between the giant wheels. The East German landscape was drab, as though it were not late June, but early spring—grass only hinting at green, and everything dull and matted. Matte. That would be a good word for the landscape with its tiny stone houses and its clotted fields and the gunmetal sky that refused to acknowledge the sun. Miles of it. The backsides of towns, the way trains always peel away the privacy of any place they come to.

[The site Gwarlingo, the source of the photograph of Kitchen in the mirror, features one of her poems and a brief biography. There’s a reminiscence at Water-Stone Review.]

November 6, 2014

Lena Dunham’s self-portrait

Not That Kind of Girl: A Young Woman Tells You What She’s “Learned” by Lena Dunham. Random House, 265 pp.

I didn’t expect to enjoy Not That Kind of Girl as much as I did. But Lena Dunham happens to be a terrific writer—funny and surprising, with lots of rhetorical moves.

On the one hand, this is very much a New York trade book: the high concept packaging includes a canny title and cute line drawings; its prose is snappy and dry-eyed for all its introspection; and it is fittingly dedicated to the late Nora Ephron. On the other, Dunham’s turn at one point to second-person point of view and her regular inclusion of segmented essays—numbered lists with neat juxtapositions—bespeaks a writer who imbibed a high creative nonfiction aesthetic in the groves of academe. Not That Kind of Girl exudes a neat hybrid synergy. Kind of like Dunham herself, with her Jewish mother and Protestant father.

Dunham portrays herself as a mess growing up and coming of age, so full of excess emotion and so plagued by phobias that you’re regularly appalled—and steadily entertained. And surprised by her meteoric rise as an actress-director-producer-writer. Except she was graced with enviably tolerant, indulgent, and long-suffering artist parents. She’s a perfect storm of nature and nurture. Her parents raised their difficult, obsessive-compulsive daughter with love, and it shows.

They also got her professional help. Repeatedly. I imagine she’ll get lots of hate for her self-involvement or for being such a neurotic New Yorker, but I admire her inquiry into herself and her emotional honesty. I like to imagine she’s a good friend. I do wonder if it’s still exhausting to be her. At least she seems to channel her energy productively into art. She’s amused by her younger self, who is a gold mine for the writer: mordant, interestingly flawed, creative, and hyper aware.

Here she is on school-days dating:

No guys like me at school. Some ignore me while others are outright cruel, but none want to kiss me. I’m still distraught over a seventh-grade breakup and refuse to attend parties I know my ex will be at. At this point, my heartbreak has lasted twenty-four times as long as our relationship.

Dunham admits to being obsessed by her mother, but mom’s a shadowy figure in the book—her sketches of her easygoing father, however, make him real, and you wouldn’t mind more dad. Her account of therapist-shopping with him is one of the book’s funniest parts.

[Dunham: awkward sex, volatile friendships, surges of hope & despair.]

These memoir essays are grouped into five categories: Love & Sex, Body, Friendship, Work, Big Picture. They blended together on first reading. Including her complete diet in one essay seemed a mistake. Her “worst email ever,” with footnotes, didn’t quite work for me, either. But then, I imagine her core audience is female and younger. I’m old enough to be her father. Yet Not That Kind of Girl offers lessons for anyone writing about himself. (How does her voice work?) And Dunham’s frankness and pleasing turns of phrase are consistently rewarding.Here she is upon returning to her college to give a lecture:

I’ve always had a talent for recognizing when I am in a moment worth being nostalgic for. When I was little, my mother would come home from a party, her hair cool from the wind, her perfume almost gone, and her lips a faded red, and she would coo at me: “You’re still awake! Hiiii.” And I’d think how beautiful she was and how I always wanted to remember her stepping out of the elevator in her pea-green wool coat, thirty-nine years old, just like that. Sixteen, lying on the dock at night with my camp boyfriend, taking tiny sips from a bottle of vodka. But school was so essentially repulsive to me, so characterized by a desire to be done. That’s part of why it hurts so bad to see it again.

I read Not That Kind of Girl because I’m using it in a “Writing Life Stories” college class I’m teaching this spring, and if the students like it I’ll certainly read it again because I’ll teach it again. There’s no predicting their response. Only in this case I’m pretty sure they’ll keep reading even if they hate Dunham. She captures the awkward sex, volatile friendships, and surges of hope and despair familiar to most twenty-somethings. They’ll enjoy the flashes of vulgarity, which arise from sexual escapades, mostly, and which Dunham doesn’t wallow in.

I’m not very familiar with Dunham’s film work, but gather that her telegenic appeal is that she’s “real.” This seems code for being considered unattractive in body, by filmic standards, and troublesome in soul but blithely undeterred. However you look at it, this book proves she’s got talent to burn.

Not That Kind of Girl brims with the deceptively easy prose of a smart, serious, and almost-always-entertaining literary artist.

October 31, 2014

Book event lessons

![[Sue William Silverman cracks up me & Linda Hundt, Kerrytown Book Festival.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415209475i/11751455._SX540_.jpg)

[Sue William Silverman cracks up me & Linda Hundt, Kerrytown Book Festival, MI.]

What I’ve learned from close-quarters pitching

1. Have an elevator speech

At three book festivals this year—the Ohioana Book Conference in Columbus, the Kerrytown Book Festival in Ann Arbor, and most recently Books by the Banks in Cincinnati—I learned an author needs an elevator pitch.

I already knew this. I had an elevator speech, which I’d used on editors and agents. But the learning curve applies: competency plunges at first in new circumstances. I hadn’t faced prospective readers as an author. So I screwed up and had to re-learn what I knew. Lessons so basic and obvious that they’re mentioned by anyone with a nodding acquaintance with authorial self-promotion.

You need a few crisp phrases. People will ask you what your book is about. “It’s about the ten years my family and I lived on a sheep farm in Appalachia,” I’d say. Thus I learned that farming isn’t a sure-fire sales pitch. No one knows anymore what you mean by that, if anyone ever did. Farming’s become, at best, exotic. At worst it is associated with abuses like erosion, toxic chemicals, and animal cruelty.

People are confused—too many labels flying around—and their eyes dim as they try to slot you. Hard-fisted agribusinessman, crunchy homesteader, one of Joel Salatin’s better-than-organic grass-based acolytes? Pray tell? No, on second thought, don’t. People wonder what you’re going to inflict on them under this rubric. Are you writing about livestock that really were pets—mooning over them and boring my ears off? Or does this story involve animal deaths—because, forget it, I like warm and fuzzy, not bloody—don’t we have enough trauma to deal with as it is?

Fair. Fair enough. So I learned to quickly add the mantra I used in my last year of revision: “It’s a story about dreams, loss, fatherhood, and farming.” I might have said place, too, but maybe farming gets that. Several women told me my book is a love letter to my wife. True. But that hardly seems an adequate pitch. I love my wife! Buy my book! A reader recently told me my book is really about healing. That sounded great to me—and accurate to the extent that the narrative succeeds in showing me grapple with my family’s farming legacy. I tried adding healing to my thematic phrase, but that seemed a word too far. Since three is a magic number, I don’t know why my four-part tag seems to work, but it does.

Then again, in some ways maybe a writer is the last person to know his own book. He tried certain things. But if it soars for a reader, maybe it’s greater than the sum of its consciously intended parts.

2. Give ’em bling at your booth

[Book + postcards and bookmarks.]

At my first book show, it also became clear I needed something to give out with the book’s name on it. (And when I worked in publishing I oversaw book campaigns.) Not everyone wants to buy right there. Maybe they want to ask their librarian to order it. Or they want to think about it—or get the e-version. So I ordered postcards and then bookmarks.Bingo. People love free stuff. And it’s true: you’ve got to cast some bread on the waters. Personally I love physical bookmarks, though they seem only slightly more popular than the postcards—which can be used as bookmarks, after all.

Now, as potential readers’ eyes sweep the stacked copies of Shepherd: A Memoir, maybe sizing up the free goodies too, my elevator pitch holds the cautiously curious for a beat longer. And a “crowd” at your table, which means two or more people—though even one helps—attracts others.

3. Upon disappointing a reader

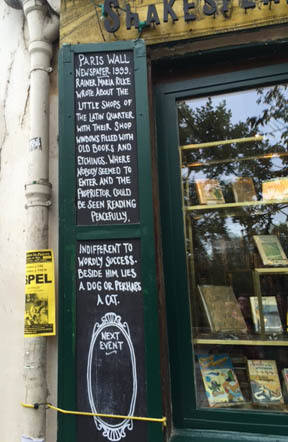

[Promo at Shakespeare & Co., Paris.]

The people I’ve talked to in these quick, intense booth exchanges blur. But I’m sort of haunted by the look one man gave me at a book-related event. Unlike booth visitors, he’d already read my book. The other day, as I read an amusing blog post at Creative Shadows about Jen Campbell’s Weird Things Customers Say in Bookstores, I recalled him.What he said instantly upon meeting me and my wife: “She looks just like I pictured her—but not you.”

It might have been funny. Except he shook his head sharply as he spoke, his face darkened with disapproval: anger’s kissing cousin. And then his severe countenance lifted, his mood reset as if with a brisk clap of the hands. We were left to soldier on as best we could in each other’s company—we got on fine.

But I’d disappointed him—by not looking like my paper portrayal—and I felt like fraud. I’d flunked as a character in my own memoir!

Maybe I hadn’t described myself accurately.

Bald? Check. Bespectacled? Check.

Slight? Well.

I weigh a tad more than the Richard Gilbert depicted in Shepherd. I may still think of myself as a little slip of a thing, but I started growing once I sat down to write and we moved off the farm. And I was even lighter in the loafers in the late 1990s when our story opens. Yet doesn’t the creator (writer, teacher, thinker, baker—parent?—entrepreneur, musician, painter) usually fall short of the image we’ve created reflexively from the artifact? A thinner if not better me, his struggling self refined in the fires of poetry and desire, wrote that book.

While I esteem art and its creators, a wiser part of me suspects that any worthy role offers, to the fully committed, the transcendence for which the human soul hungers.

![[Dunham: awkward sex, volatile friendships, surges of hope & despair.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415458710i/11792864.jpg)