Teaching memoir, ver. 3.0

[James Baldwin, author of America’s greatest essay, “Notes of a Native Son.”]

Structuring a memoir-writing class by focusing on essay structures.

I blogged last year about teaching memoir by emphasizing the essentials of persona, scene, and structure. Except now I list and teach scene first because students get the macro aspects of voice faster—essentially persona, the writer now, talking to us about the past—but many need help understanding how and why to dramatize, to make scenes. So SPS: scene, persona, structure. From the start, this gives us a shared vocabulary. To understand scene, you must understand summary—and often students who have written vivid summary think they’ve written scene.

That’s the thing about teaching writing: you must teach so much at once. You hope that by providing good models, students will emulate more than the stated focus. And they do. Nothing teaches the teacher, however, like teaching. Last year, my college juniors and seniors in “Writing Life Stories: The Power of Narrative” said they wished that I’d emphasized structures earlier. So this time I have.

Structure, the shaped mode of presentation, excites students. They see how it can help them crack open their material. They grasp that it can cut plodding “and then” or unnecessary backstory. Halfway through the semester, already I’ve shown them: braiding (Jo Ann Beard’s “The Fourth State of Matter” always amazes everyone); framing (a favorite new essay is Kelly Sundberg’s “The Sharp Point in the Middle”); collage (“Documents” by Charles D’Ambrosio); and Hermit Crabs, among them Pir Rothenberg’s funny “Woman Told,” made from women’s OkCupid dating profiles, which also shows the closeness of nonfiction and poetry.

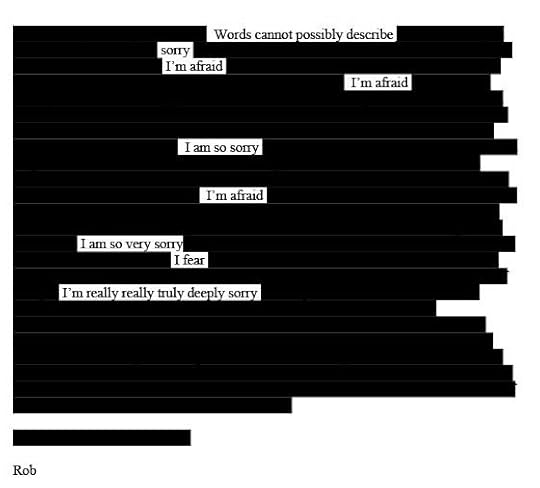

There’s an amazing, disquieting new Hermit Crab at Diagram, Brooke Juliet Wonders’s “Self Erasure,” which redacts her lover’s suicide note:

[A page of Brooke Juliet Wonders’s essay “Self Erasure.”]

Next we’re looking at segmentation, probably reading Jonathan Lethem’s “The Beards,” Lee Martin’s “All Those Father’s That Night,” and Dinty W. Moore’s “Son of Mr. Green Jeans,” the latter a Hermit Crab as well, taking as it does an alphabetical list for its structure.Emphasizing essay structures has caused me to realize that I can organize my entire class by examining different writing structures. After a month or so focusing on the Big Three of scene, persona, and structure, we can examine a structure a week. Then we can turn, say, to a theme that allows me to have them read more great essays. Under the “The Pains and Joys of Others” we can read: the greatest American essay, James Baldwin’s immortal “Notes of a Native Son,” which also allows us to revisit the framed structure; and Brian Doyle’s powerful flash essay “Leap,” about 9/11; and Ryan Van Meter’s “If You Knew Then What I Know Now,” which is also an instance of second-person address.

We could finish the semester with something like “You in Real Time,” which might include Moore’s witty essay about his name, “Mick on the Make,” Jill Christman’s deft “Family Portrait,” which as a bonus is in third person, and Elizabeth Kavitsky’s twentysomething self-portrait “Winter Just Melted.” I could have them read Brenda Miller’s flash essay “Swerve” as well. (I must figure out whether to consider separately flash essays, which intrigue students almost as much as structure does.)

Matching stated weekly themes with example essays can be crazy-making. But what inclines me to try it is how the stated theme plus examples can support my weekly writing prompt. Under “The Pains and Joys of Others,” I could give them a standby, a prompt to write about an odd person they’ve known; for “You in Real Time” I could ask them to write about “Me, Now,” as in Kavitsky’s essay about her post-college drift into ordinary adulthood and her lesbian sexuality. Or have them write an apology to someone, whether sincere or, as in “Swerve,” facetious and dripping with scorn. (Most undergraduates take the latter option, which is fun—and makes the heartfelt exception doubly affecting.)

To appreciate my breakthrough, it might help to know that my “Writing Life Stories” class meets in person once a week and that the syllabus lists a different theme for each week. For instance, Week 11 is titled “Dramatic tension, foreshadowing cont.,” and Week 12 is listed as “Language, Tone, Style, Humor.” At the time I slapped such headings on the syllabus I suppose I thought that so saying meant so doing. But, in practice, those categories are at once too weighty and too vague for me. Or maybe it’s just that they don’t work as organizing principles, to me too recipe-ish—“stir in some foreshadowing and add a pinch of humor”—when I tend to underscore the overall container for a story, its structure, and then turn to elements of its content.

As in writing, in teaching there’s what you plan and what you find yourself doing.

Maybe it boils down simply to this: I can’t wait to share certain essays with students. By categorizing such essays—according to structure, from chronological to collage, and by shared themes—I form the spine of the class and space my favorite readings throughout the semester.

Of course this plan will, in some sense, fail. But it will help the course and me as a teacher to evolve.