Richard Gilbert's Blog, page 15

October 29, 2013

Illogical and emotional

Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat: Why It’s So Hard to Think Straight About Animals by Hal Herzog. Harper Perennial, 279 pp.

As a dog owner, an “animal lover,” and a former farmer, I largely enjoyed Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat. Author Hal Herzog’s message is simple and clear: humans’ relationship with animals is illogical and emotional. My bona fides didn’t make me a logical-minded reader. I got emotional reading some of the stories.

But there were unforgettable passages, such as his outlining the strong animal rights stance of Nazi Germany. This created great difficulties for the Reich because it had to dispose humanely of so many pets that had belonged to the Jews they were mass murdering.

My view of the book is complicated by the fact that I read it as a member of my university’s screening committee for possible common books. A common book, which is read by every entering freshman, must have two qualities: a strong story and a strong social issue; Herzog’s book is more of a collection but explores a strong social issue. And our students would find it interesting, I think, at least initially.

I was concerned they might wonder why they were reading the same message repeatedly—that there’s no sense in how we treat animals of different species—and might bog down. And then my own biases came into play.

For instance, Chapter Six, comparing the relative cruelty of cockfighting and meat chicken production, points out that gamecocks live like princes for about two years before they are fought, while broilers live for only six to eight weeks in nightmarish factory-farm conditions before they are brutally slaughtered. While condemning cockfighting, Herzog concludes that it is less cruel than mainstream agriculture’s production of chicken protein. I happen to agree, but wanted him to bore in. Why have growing numbers of people in developed nations increasingly found blood sports repugnant while, until recently, have turned a blind eye to the cruelties of industrialized agriculture? What’s the moral difference between fighting naturally combative roosters and killing for food helpless, abused broiler chicks? Where is the line between enjoying seeing two roosters fight, and at least one die, and horse racing in which horses are often drugged, are raced with painful injuries, and in which many are destroyed?

I thought I was being logical but may just have gotten my buttons punched.

[Hal Herzog, snake.]

Herzog is an affable guide, however, and Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat is enlivened by his persona. Beyond a strong story and a strong social issue, a successful common book must have a living author who is willing to come to campus. And he must be able to win the attention of easily bored eighteen-year-olds. A tall order. I think there will be less complicated candidates this year, which in a way proves his point, but I could live with Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat.October 22, 2013

Choosing love, as person & writer

[Shirley Showalter: Embracing her blush.]

In my recent review of Blush: A Mennonite Girl Meets a Glittering World I noted how author Shirley Hershey Showalter wrote interestingly about her happy childhood for a wide audience, though she grew up in the specific, narrow, and intertwined agrarian and religious world of Mennonite rural Pennsylvania in the 1950s and ‘60s.Her parents’ firstborn, she was heir not only to their accomplishments but also to their unrealized ambitions. Obviously a smart, positive, and attractive child, she had her own gifts and desires to express as well. The result, set against the backdrop of the changes sweeping America and her church, provides more than enough tension for a good story.

Showalter explains in a short video about the book:

The book’s title—Blush—refers to my discomfort in that place between the church and the world. It also means that I tried so hard to be sophisticated. It took me a long time to discover that God made me a feisty, curious, plain Mennonite farm girl for a reason. When I am vulnerable and wholehearted, I am much more aware of God and my community can come in and support me, even in times of conflict and pain and doubt.

I’m no longer plain on the outside, but I would love to be plain on the inside. Being plain is not simple. True simplicity requires us to drop our pretenses, let go of our ego and learn to embrace the blush, rather than to fight it. This wisdom is ancient. It’s as true for you as it is for me. And the place where it leads is home.

I know Shirley Showalter as a virtual friend, having become a fan of her blog some years ago. She answered some questions by email.

Why did you write Blush?

I have no single reason, but that doesn’t mean I had no purpose. In fact, I wrote it for all of the following: to leave a legacy to children and grandchildren, to “bring the muse into my country” (following Virgil and Willa Cather), to describe a rural and religious world that no longer exists, to place my childhood inside the context of the larger cultural changes happening in America, and to inspire others who may feel caught between worlds or who grieve or who are facing conflict between the generations.

Though a true memoir about your first eighteen years, with its diverse subjects, photos, footnotes, glossary, and recipes Blush contains elements of history, scholarship, and traditional autobiography. How in the world did you manage to pull so many threads through the story?

I started with about seven or eight stories that had been written for other publications. I outlined other subjects from a timeline I created early in the writing process. Then I created a narrative arc diagram and made three other diagrams to help me layer the themes of blush and simplicity on the yonder side of complexity. This concept of second naivete (Paul Ricoeur) or second simplicity (Richard Rohr) has been identified by many philosophers and poets over time. I first encountered it years ago in the writings of Quaker mystic Thomas Kelly. Blushing became the metaphor I was looking for to connect the “me then” of childhood with the “me now” of late middle age/early elderhood. In adolescence, I blushed when I encountered complexity in the world outside the church. I blushed when my inner desires erupted in ways I couldn’t control.

From the vantage point of 65 years, however, I could see, for example, in my happy, sectarian, childhood, the seeds of a much more universal approach to life and faith. The simplicity enforced by bishops in my youth became the simplicity I myself chose after having lived a life of complexity in middle age. In the book trailer, I describe myself as no longer being plain on the outside but desiring to be plain on the inside. That’s what I mean by a second naivete: choosing to endorse the principles that lie underneath the old rules, especially the principle of love.

Placing stories in their historical context comes naturally to me, since I was trained in American Studies. I tried to create the kind of book I myself enjoy reading. I love old photos. I knew that some readers would need explanations of the more exotic practices of my faith (hence, some footnotes and glossary), and recipes—well they were just the icing on the cake. I had to remember to let the narrative lead and offer the other elements as complementary, not essential.

Many writers benefit from developmental editors. In your book’s Acknowledgments you credit freelance editor Dave Malone (Malone Consulting) for helping you get your manuscript into final shape before you submitted it. Could you discuss his shaping or what he helped you see?

[Dave Malone]

[Darrelyn Saloom]

First, I have to credit Darrelyn Saloom, who became an instant friend after having been an online friend. Darrelyn volunteered to read my manuscript, which had already been submitted to my publisher. When she told me that it wasn’t ready, my heart sank, but I also recognized the ring of truth in her words. She connected me to her editor friend Dave Malone, and he and I together gave the manuscript one more complete revision. The biggest changes? We cut 20,000 nonessential words (one whole chapter and numerous interesting digressions) from the manuscript. Dave also helped me to tighten the narrative focus within stories, reserving the “punchline” for the ending, for example. Those are the two most valuable changes from this final revision. I worked for three solid weeks, taking suggestions and rewriting. I’m glad I did it. This last-minute push was one more example of the value of growing up on a farm. As Daddy always said, “Every thing worth doing is worth doing right.” And “you gotta make hay while the sun shines.” :-)

[Cynthia Newberry Martin has featured Malone on her blog, in a self-interview about himself as a writer.]

What did you learn about yourself in writing Blush?

A lot! Mostly, I learned how much my parents still live inside me. I recognized things like the irony that I was “plainer” than either my mother or my grandmother at age 17; I was the third generation of “only daughters” on my mother’s side; my grandfather’s conflict with his brothers paralleled his conflict with my father. All these are things I saw in new ways through reflection, conversations and interviews, and by sitting still for a long time and gazing at old photos a long time.

Did writing the book help you to see more clearly oppositional aspects of your life, which are epitomized in your very name (Shirley means “bright meadow,” but she was named after Shirley Temple)? For example, modesty versus ambition; the virtues of a tight, counter-cultural faith community versus the opportunities of the diverse secular world (or even versus mainstream religious denominations that would seem to accept lesser commitment).

Oh yes. Thanks for picking up on the irony and opposition in my name. The first few sentences of the memoir about wanting to be big plunged me into opposition right away. Pride v. humility. Large v. small. Church v. world. When I wrote them (at the end, not the beginning of the process), I knew I had “hit the home pasture,” to quote Willa Cather.

What do you hope your memoir provides for general readers, for scholars, and for Mennonites? For your family?

I have a different dream for each type of reader. But here’s the way I envision the way this memoir might serve the needs of all four groups, reversing the order above:

I start with my family. The memoir will ground my grandchildren in one fourth of their genetic pool, and it will implicitly pass along values that I consider important. My siblings and cousins have expressed appreciation for it, and my mother is ecstatic. I also hope other Mennonites will have their stories told. Many Mennonite readers have already said, “this book puts into words feelings and experiences I too had.”

If Mennonite readers resonate, I hope they will tell their friends and share the book with people who are curious about Mennonites and Amish, perhaps because of media coverage or because of reading other books or traveling to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.

I’ve also been building a community (you interviewed me about this effort—Ubuntu) among readers of my blog, newsletter recipients, and Facebook author page. Some of my most enthusiastic readers are not Mennonites. I hope that this book “crosses over” to the wider audience of those who love memoir. I find that many readers resonate with the “blush” theme. The encouragement to “embrace your blush” can apply to nearly everyone.

Scholars will probably have less interest in this book than in other kinds of analysis and well-documented artifacts. I’m glad narratives can contribute to the historical record, and to that extent this book may count as scholarship. I tried to be careful with the facts.

Previously: My review of Blush.

October 17, 2013

Shirley Showalter’s ‘Blush’

Blush: A Mennonite Girl Meets a Glittering World by Shirley Hershey Showalter. Herald Press, 271 pp.

The sheltered life can be a daring life as well. For all serious daring starts from within.— the epigraph for Blush, taken from Eudora Welty’s One Writer’s Beginnings

Though Shirley means “bright meadow,” fitting for a “plain” (Mennonite) girl growing up in the 1950s and ’60s on a Pennsylvania dairy farm, Shirley Hershey Showalter was actually named after Shirley Temple. The divided roots of her first name epitomize the tensions that animate her memoir, Blush: A Mennonite Girl Meets a Glittering World.

Showalter’s faith community both nurtured and frustrated her as she sought to reconcile its conservative values with her desire for gaudier self-expression. Caught between her plain church and the glittering world, in her discomfort Showalter often blushed. The depiction in the life of a fortunate Mennonite girl of this everlasting human conflict, essentially between communal obligation and individual desire, is what makes her story both universal and timeless.

Showalter has said her riskiest words in Blush are its first:

Ever since I was little, I wanted to be big. Not just big as in tall, but big as in important, successful, influential. I wanted to be seen and listened to. I wanted to make a splash in the world.

Indeed she has. Although it covers her first eighteen years, Blush indicates how Showalter has been able to live anchored in her Mennonite faith while navigating as an adult in the wider world—including earning a PhD in American civilization, becoming an English professor, the president of a Mennonite college, and a foundation executive.

Mennonites arose as the followers of Menno Simmons (1496–1561), a Dutch priest who joined the Anabaptist movement. Anabaptists, or rebaptizers, started as a group “who withdrew from both the Roman Catholic Church and the newly Protestant churches,” explains Showalter in her memoir’s glossary. “The practice of rebaptizing adults and of refusal to baptize children was seen as both a threat to the established church and the state.”

The rigorous twin pillars of the Mennonite faith, as Showalter experienced it near Lancaster, Pennsylvania, were nonconformity and nonresistance. As well, she was trained to be a “beacon of kindness” for others.

Showalter’s mother, Barbara, also grew up on a Mennonite farm, surrounded by brothers. In lieu of a sister, she yearned for a Shirley Temple doll. In high school she was attractive, a buoyant singer, actress, and aspiring writer. She was late, at age 19, to assume her faith’s outward symbols, plain dress and, for women, a prayer covering. Though she would raise her daughter in the church, and affirmed farm life as her best and only life, she’d been a bold and ambitious young woman; her unrealized early ambitions “would incubate a yearning” in her daughter. For the chapter on her parents’ marriage, Showalter takes an epigraph from Carl Jung: “The greatest force in the life of any child is the unlived lives of their parents.”

Showalter’s father, Richard, tall and handsome, was the son of a farmer and likewise became a farmer. But his father had been harsh, and buying his family’s farm worsened his pain, for his father became his landlord. Richard loved farming, however, and indulged in a taste, shared by some others in his congregation, for fancy cars. When his daughter was in high school he bought her a sporty used Studebaker convertible—though it was black, which was “the kind of joke he liked.” She writes of him:

Daddy had no greater goal, after years of dating and driving eye-catching cars, than to become as successful a farmer as his father had been. There was a little spite, a little competition, and a lot of neediness in his yearning. He also wanted to hold his place in the unbroken Mennonite line of Hersheys who had always served the church.

I am heir of all these desires.

Forty families in her church knew her and the particulars of her young life. She basked in this attention, and sometimes shed a joyous tear when singing hymns. But she also loved pretty dresses, jewelry, and fancy hairstyles; joining the church was a choice she would make, but it wasn’t trivial. Immersed in a wholesome, loving, and idealistic community, she could not fail to notice its feet of clay. Its obsession with sinful pride might stifle the individual; its nonconformity to the world might mask within-sect conformity; its patriarchal and sex-segregated structure could devolve into simple sexism.

Yet its values also provided seventh-grader Shirley with the willpower to support John F. Kennedy as president in 1960—breaking with almost everyone she knew—and gave 17-year-old Shirley the courage to protest a new bishop’s stricter dress code for teenage girls. The older women of the church were also appalled by the man one Sunday when he refused communion to a girl whose dress or hairstyle offended him. Showalter watched the women “start to breathe in rhythm, their eyes wide” at the cruelty of his haughty act:

Without knowing it, we were participating in a crisis of leadership larger than our own congregation. The church’s visual separation from the world had been slowly eroding over decades as the culture around us became harder to resist. What had been taking place in an evolutionary manner for a long time only became obvious because of many who wanted to reverse the trend.

If the bishop could refuse the cup of communion to a baptized member of the church, what would come next?

What happened was that the reactionary bishop wasn’t happy, either, and moved on. (What happened eventually was that Showalter’s branch of the Mennonite Church relaxed its strictures regarding plain dress and prayer coverings.) Showalter’s outsider’s perspective, and her desire to find an authentic self within her religious tradition, grew as she moved through the mainstream school system; by high school, she was one of only three Mennonite girls among the 144 students in her graduating class. On the one hand a typical teenager, feisty and full of life, her Mennonite prohibitions included dancing, television, and movies. She sat out her gym class’s unit on dancing, watching with one other plain girl from wooden bleachers, feeling lonely.

Yet the complex threads of her upbringing met her own gifts to kindle perceptiveness and a scholarly bent:

I began to see that identity formation always includes an “us” and a “them.” It’s easy to see all sweetness in “us” and all sour in “them.”

Blush is rich in metaphor and works this sweet-sour one well—including in two chapters on food (and there are recipes in the back)—and is informed by deft use of historical context and enlivened by family photographs. Showalter even acknowledges Native Americans, those who lived on the land before her ancestors and whose stories were largely lost along with their villages, cleared with the forest to make space for settlers and their farms. Showalter explains in a blog post that all proceeds from the sale of Blush will go to support the Longhouse Project, the construction of a Native American dwelling by the Hans Herr Museum in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.

If I have emphasized the tensions in Showalter’s account of a happy childhood, it’s because Blush shows how such pressures forged her as a person and as a leader—and because she deploys them so artfully as a writer. For all its impressive facets, Blush also achieves the virtues of a true memoir, conveying Showalter’s lived experience in the wisdom of her singular voice.

Next: An interview about Blush with Shirley Hershey Showalter.

October 9, 2013

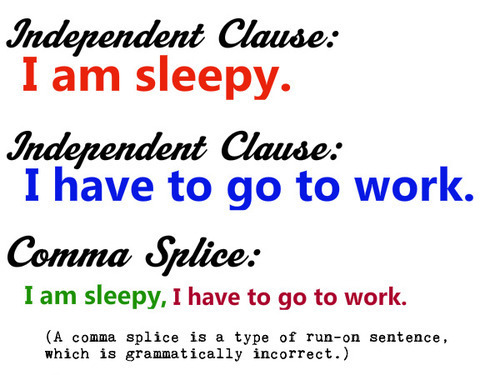

Combating the comma splice

[Warning: This memoir contains comma splices!]

Right now in the semester, I’m buried in student essays. Hour after hour goes into grading—sometimes over six hours at a stretch, and then there’s reading and class prep. And then more essays, a constant backlog, from busy young writers and revisers. I give them work, and it boomerangs right back. Yet if I suck after sympathy I recall an academic acquaintance’s rejoinder: “That’s a self-inflicted wound.”Sure. But it’s my job. And as a fellow teacher once remarked, “Reading some of them is like getting hit in the forehead with a hammer with each sentence.” Yes, and again, that’s what we’re paid for. And I get to sit on my couch and listen to the Beatles while I grade.

Comma splices are the bane of my existence. Actually they’re how I justify my existence. I tell myself, I’m giving them practice writing and teaching them that comma splices are bad. Showing them all the good punctuation options. Not to mention cluing a few of them to the utter ignominy of the run-on.

I remember so vividly my own dawning awareness of original sin, as an undergraduate, when a professor circled my comma splice. In my memory it’s actually in a blue book—though why even an English professor would bother to correct a comma splice in a handwritten exam flummoxes me. “Don’t use comma splices,” he wrote. I marched right up and asked him what that meant. He explained that a comma wasn’t sufficient to join two independent clauses.

Right! I was studying writing on my own, so I saw it right quick. Today comma splices sometimes bother me even when a professional writer uses them intentionally. Or even when I do. Except when the clauses are real short—but I take note of them. I can’t help it. Okay, buddy. I guess so. Might’ve used a nice semicolon there, though. And if it’s mine, I usually change it. Whereas I love sentence fragments. Usually.

Memoirist Mark Richard’s use of comma splices

[Mark Richard: comma splicer.]

Here’s a comma splice from a skillful writer, Mark Richard, from his memoir House of Prayer No. 2: A Writer’s Journey Home:Most of them have been up all night tying tobacco sticks, their hands are stained black with nicotine.

Now, I’d cut the “are” in the second clause so that it becomes a dependent clause and the comma correct. Thing is, he may have wanted the strength of “are”—and no semicolon, though he uses them elsewhere. So there you are, a splice. Yes, it works. I don’t favor it.

House of Prayer No. 2 is written with a very unusual point of view for a memoir: it starts in third person and switches to second. Here is another of Richard’s spliced sentences, which also showcases his use of second person and present tense:

At home the Christmas tree is up, your mother cooks shrimp Creole for you.

This one bothers me more, since the two clauses have different subjects. The theory I’m working on for why Richard uses the occasional splice is that they’re a way of strengthening the second-person voice of his young narrator (himself). I say that partly because there’s nary a dash in the whole book. Dashes would heighten the sense of the author at his desk, manipulating the story, I believe.

As it is, however, Richard seems to hover outside his narrative in some “now” beyond the story, even though he uses present tense (which very much emphasizes the action “then”); this is because although second-person point of view would seem to distance him from the narrative, in an odd way it emphasizes that there’s an author behind the scenes. Plus, he sometimes writes from others’ points of view, as when he imagines his father’s, and that emphasizes the writer at work and his shaping, retrospective view.

While few beginning writers fall into complex sentence patterns, subordinate clauses and the like, many naturally pitch headlong into comma splices. Maybe humans think or talk that way. I’ve heard comma splices are accepted in German prose. I have two classes of freshmen reading Richard’s exciting memoir, but none will notice his splices unless I point them out. So I don’t think it will worsen the fault. In fact, the more a student has read the less likely he is to splice and the faster he will correct the fault once it’s flagged.

My wife, an administrator, chastises me for my obsession with a minor error that hardly hurts meaning.

Then she teaches her one freshman seminar a year. And starts complaining about comma splices.

Examples of options for fixing comma splices

During my annual academic-year battle against the humble comma splice, I show students this example:

The brown dog barked, the black cat ran.

Now, yes, it works, this sentence—it’s mine. Theirs are worse. And where will it end if I cave? Despite my fixation, I sometimes pause before I circle the splice, because most students barely use commas as it is.

“That’s a comma splice,” I say, and explain, as it was told to me so long ago. I’ve also developed a page-long sheet, which shows the sinner all the great punctuation he’s leaving on the ground.

The options include:

The brown dog barked; the black cat ran.

The brown dog barked—the black cat ran.

The brown dog barked, and the black cat ran.

“See the differences in tone?” I say. “Even in shades of meaning? Isn’t that neat? All the options?”

Every so often, by doing this, I convince a kid that commas are bad. He cuts every comma he can. He writes:

The brown dog barked the black cat ran.

And just like that, I’ve turned a mere comma splicer into a run-on fiend. Someone who doesn’t even tap his brakes at the intersection but who shoots his car right through. Someone who bloodies his reader’s nose as he lurches him from one clause and smashes him into another.

I’m on record elsewhere with my despair. A biologist friend who teaches, and who calls comma splices “comma faults,” once tried to comfort me with this nugget: “You can’t hurt the good ones, and you can’t help the bad ones.”

A bitter little pill, that one. But I’ll take it. As the Beatles’ rivals sang, “It’s only rock and roll.” (And their music pretty much was only that, good as it was—sorry Stones fans.)

When I retire from teaching in a few years, surely I won’t miss my foe the comma splice. But I’ll sure miss grading along with the Beatles.

There’s a judicious post at Sentence first about comma splices.

October 4, 2013

Grading essays to the Beatles

[Playfully creative upbeat tunes: astonishing productivity and musical sophistication.]

That is you can't, you know, tune in

But it's all right

That is I think it's not too bad

—“Strawberry Fields Forever”

[Magical days: the Beatles' Mystery Tour photo.]

The Beatles’ playfully creative upbeat tunes buoy my spirits as I grade student essays. Mostly I play late albums, usually Abbey Road or Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Sometimes The Beatles (aka The White Album) or Magical Mystery Tour. Since I’m a boomer, this choice is freighted with nostalgia. One of these days, I’ll burst into tears. I’m getting choked up right now, listening to John Lennon’s surreal reminiscence, “Strawberry Fields Forever.” Oh, that tender musical intro by Paul McCartney . . . his Mellotron keyboard a ghostly calliope.And how is it possible that McCartney follows “Strawberry Fields” on Magical Mystery Tour with his own masterpiece musical memoir, “Penny Lane”?

It’s not possible. But there it is.

So mostly my listening experience is characterized by my amazement of the band’s artistry and output. They became such sophisticated musicians (a nod here to their great teammate, producer George Martin), and as they grew they created songs of delicious musical complexity and thematic richness.

With the Internet at my fingertips as I grade (students’ longer essays are in digital form, so I’m using my laptop), I can look up lyrics. Or more often, I peruse the songs’ composition histories and recording accounts on Wikipedia. I grew up listening to the Beatles and other great music of the 1960s and ’70s, and so it seems to me now that I couldn’t have known how great they were. They just were. There. In the air.

Yet I recall how special they were to us. I wrote once here about listening to their first albums in my big sister’s bedroom and feeling a portal to adolescence and art open. With age and Wikipedia, my admiration of the Beatles is, if nothing else, more informed.

And I have a new, embarrassing admission. Having written a book, I feel my appreciation for their constant creation is deeper than it used to be. One book—though seven years of endless writing—and I identify with them. With their use of stray bits, stuff grabbed from the news, their passing moods and odd encounters. Their lives.

The word for them, I believe, is protean. Me, maybe not so much. Yet my memoir, all six versions, one glitch fixed after another, was my own Magical Mystery tour into my past.

~ ~ ~

Penny Lane is in my ears and in my eyes

There beneath the blue suburban skies

—“Penny Lane”

[Turning pensive: the Beatles' White Album portraits.]

Bill Roorbach pointed out in a recent post, “Art is the solving of problems.” And boy, were the Beatles always solving problems in their decade together. Like 67 takes to get a song right (George Harrison’s “Long, Long, Long” in the White Album sessions). Always trying stuff, they were. More cowbell! Handclaps? Sure.In their wild messy crucible, the only constant was constant work. They were working hard, when they were. And they were loose too, getting each other in the mood, goading each other on.

McCartney was incredibly prolific, and I think he helped Lennon by pressuring him to produce. Of course their talents were complementary. McCartney’s seem more diligently worked, and recognizably draw on various traditions; Lennon’s appear more artistically intuitive, and more often their result is abstract, elusive. The prime example being “Strawberry Fields” vs. “Penny Lane.” I’m drawn constantly to the mazy former song, though probably I love more of McCartney’s songs than Lennon’s.

After their intense recording sessions, Lennon suffered creator’s remorse. In later years he’d accuse McCartney of being careless with his songs—and even of sabotaging them (including, incredibly, given McCartney’s sensitive playing on it, “Strawberry Fields Forever”; Rolling Stone ranks it number three on its list of 100 greatest Beatles songs, so Paul didn’t hurt it too badly). Now, I doubt I’d like either genius Beatle as a person—my hypothetical personal affection goes to George and Ringo—but Lennon and McCartney were too much the pros for such nonsense. They sang together, for a time, when they were hardly speaking.

Here’s a discussion, from Wikipedia, about Lennon’s waffling over his great song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” inspired by his son Julian’s drawing:

In later interviews, Lennon expressed disappointment with the Beatles’ arrangement of the recording, complaining that inadequate time was taken to fully develop his initial idea for the song. He also said that he had not sung it very well.

In the end, the work you make transcends the effort you make. If you are lucky. Anyway, what you got when you were trying hard is what you got. Whether it takes seven years to write a book or 67 takes for one song. Lennon couldn’t accept that. And maybe to a degree anyone who creates feels that way.

Perfection is not only elusive, it’s impossible. Art is a handmade, human thing.

Or so I think today, grading these essays, one Beatles tune at a time. Gettin’ by with a little help from my old friends.

[image error]

[Wikipedia: The gatepost to Strawberry Field, now a Liverpool tourist attraction.]

![[Hal Herzog, snake.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1386361142i/7347603.jpg)

![[This great memoir contains comma splices!]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1386361142i/7347608.jpg)

![[Magical days: Mystery Tour photo.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1386361143i/7347612.jpg)

![[Turning pensive: White Album portraits.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1386361143i/7347613.jpg)