Richard Gilbert's Blog, page 11

October 19, 2014

Novel as waking dream

[Jean-Antoine Watteau’s Pilgrimage to Cythera expresses a similar nostalgia.]

Haruki Murakami constructs human drama on a railway platform.

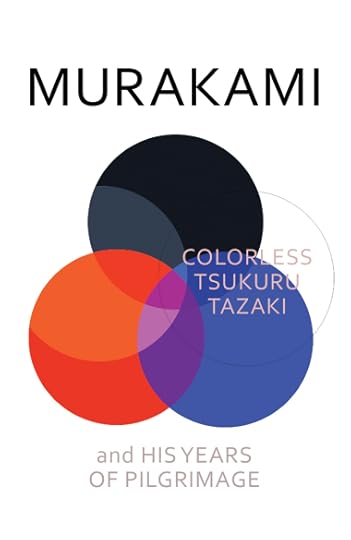

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage by Haruki Murakami

New York: Alfred A. Knopf (Borzoi), $25.95 (400 pages).

Translator: Philip Gabriel. Jacket and Binding Design by Chip Kidd

Guest Review by Lanie Tankard

You believe happiness to be derived from the place

in which once you have been happy,

but in truth it is centered in ourselves.

[Chip Kidd created the novel’s striking design .]

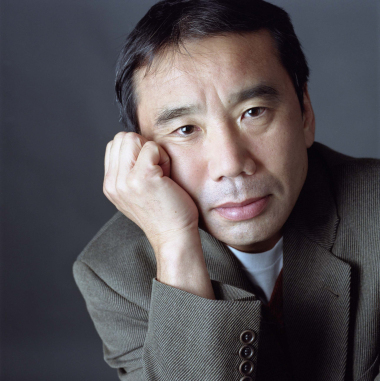

Where do ideas begin? How are they spread? Researchers at GDI, an independent think tank in Zurich, consider such questions. They study significant creative intellectuals in our world. Seven novelists made their most recent list of Top 100 Global Thought Leaders. Japanese writer Haruki Murakami was one of them, at Number 47 for his most notable idea: the “utopia of love.”Murakami continues to explore aspects of the idea of love in his latest book released in English this past August: Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, which is considerably easier to tote around than his last one—if you like tactility in your tomes. The story of Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki spans a mere 400 pages, whereas Murakami’s previous novel, 1Q84, clocked in around 1,000. Tazaki is also more compact, making it a delight to hold.

I have a Kindle version as well, but I kept returning to the hardback—partly due to Chip Kidd’s masterful design. In his 2012 TED talk, Kidd said he considers what stories look like when he gives form to content: “A book cover is a distillation—a haiku, if you will, of the story.” He also designed 1Q84, in which Murakami played with ideas about the moon and love in parallel universes. One dictionary definition of the word moonstruck is “in another world,” which certainly fits the themes of 1Q84—almost as if they arose from a line by Ovid writing of love in his narrative poem Metamorphoses: “It’s not as though the moon had interposed its own pallor between the earth and you.”

Which makes it all the more interesting, then, to find Murakami’s book that followed 1Q84, the recent Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, segueing so neatly into Ovid’s very next line in Metamorphoses: “Love is the force that leaves you colorless.”

Who is Tsukuru Tazaki and why is he colorless? He is an engineer in Tokyo who designs railway stations. A woman has brought a spot of color into Tazaki’s life but she notices something missing. She suggests he needs to solve the mystery of an event that occurred in his younger years among his tight-knit group of friends, an incident that has weighed him down ever since. He has lost touch with them, but she assists Tazaki in procuring the information he’ll need to track down the four friends. Then she leaves him to his task. Readers travel with Tazaki between past and present, at times wondering if it’s all just a waking dream. Slowly, through his search, he attains the peace of knowing with certainty just who he is in the present moment.

Readers are not the only people provoked to think as they make their way through novels. Writing is a particularly enlightening art for the one placing the words down, as an author plumbs personal experience and lays the tracks of a plot while designing the platform. Is Murakami consciously plumbing the depths of his life as he writes? Or are his fascinating novels purely imagination, unfueled by self-analysis? Murakami can be read on so many levels beyond the mere storyline in his books, as he steadfastly sprinkles his unique style with philosophical, musical, artistic, cultural, sexual, psychological, romantic, and other types of thoughts. His genre-spanning tales are intellectually nuanced with brilliant metaphors every which way you look.

[Haruki Murakami: ranked a "top global thinker."]

Murakami noted how he employs music in his writing during a 2004 interview for the Paris Review: “Writing a book is just like playing music: first I play the theme, then I improvise, then there is a conclusion, of a kind.” The musical score Murakami selected as a leitmotif for Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage is part of a Franz Liszt piano composition, Years of Pilgrimage, called “Le mal du pays” (homesickness). In the novel, pianist Lazar Berman plays one character’s preferred version. Tazaki’s melancholy longing for earlier contented times with his hometown friends becomes a homesick refrain throughout the book.Composer Franz Schubert expressed that idea in the quote I included at the beginning of this review. An interesting artistic representation of the thought might be found in a painting by Jean-Antoine Watteau titled Pilgrimage to Cythera, in which one art expert at the Louvre notes a young woman “looking back in nostalgia at the place where she has spent so many happy hours.”

In Murakami’s Tsukuru Tazaki, there’s still a touch of the little child in the man, who developed a passion for trains at an early age not unlike those felt by current young aficionados of Thomas the Tank Engine. Tsukuru Tazaki became one of the lucky people able to translate a longstanding fascination into a profession. Or perhaps it was simply destiny, as the name “Tsukuru” chosen by his father means “to make or build.”

The novel is a mix of magic realism, societal commentary, and Bildungsroman as Murakami explores Tazaki’s formative years—not unlike the Goethe classic Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship.

And in a nod to Goethe’s sequel, Wilhelm Meister’s Journeyman Years, a journeyman apprentice follows Tazaki around at one point in Murakami’s novel.

The bulk of Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki takes place in Japan, but a section is set in Finland. Reading Murakami always takes your mind to new realms. In this book, he blends observations on such diverse topics as wristwatches, lung cancer, online information, personal development seminars, Lexus cars, dominant genes, decimal systems, polydactylism, swimming, and happiness—to name but a few.

Occasionally stilted conversations and what seem like odd translation glitches do pop up, but these minor blips can’t mar the joy of coming across lovely visual sentences like this one: “She led him down the hallway with long strides, heels clicking hard and precise like the sounds a faithful blacksmith makes early in the morning.”

To establish the social function of railway stations in Japan, Murakami crafts portions of this novel in the maze of Shinjuku, the world’s busiest railway station with over three million passengers each day. In an elegant ending, the last train of the night pulls away as if it were a curtain coming down on a play’s final act.

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage lists thirteen other works of fiction by Murakami, plus a nonfiction book and a memoir. Murakami’s next novel, The Strange Library, will be released December 2. Get ready for a tale of a young boy’s outlandish day at the public library.

Lanie Tankard is a freelance writer and editor in Austin, Texas. A member of the National Book Critics Circle and former production editor of Contemporary Psychology: A Journal of Reviews, she has also been an editorial writer for the Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville.

[Murakami selected part of a Franz Liszt piano composition, Years of Pilgrimage, called “Le mal du pays,” as a leitmotif for Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage.]

September 18, 2014

Hinterlands man

If I had to sum up my “career” in one word, it would be gratitude. I get to write and tell stories all around the country, then come home to be with my family and hang out at the local feed mill complaining about the price of feeder hogs. It’s a good life and I’m lucky to have it.—from Michael Perry’s bio on his website.

[Humorist, musician, bone-crushing writer.]

Michael Perry is what so many people are trying to be. Not a writer, though he’s that—many times over—too. He’s a local. A local boy who went off and came back and made it big by putting down roots and celebrating his people and his place. But he’s not exactly your garden-variety local because he writes. And because his work has high literary merit and aspirations.Perry self-published four books before he got an agent. Then, writing about his hometown through the lens of his work as a first-responder, he found his deepest material. Swinging for the fence, he produced Population: 485: Meeting Your Neighbors One Siren at a Time, published first in hardback in 2002.

“You have to write something every day, even if it’s junk, to keep those gears turning,” said Perry, now the author of nine trade books, to a group I’m affiliated with, Hospice of Central Ohio. He was the keynote speaker last Thursday for our annual conference, held in the depressed middling-size Ohio city of Newark.

In Population: 485, here’s how Perry says he tells aspiring writers the secret of his success:

Stubbornness and blind luck, I want to say, but they’re looking for something tangible, so I tell them I discovered the secret years ago while cleaning my father’s calf pens. That is, you just keep shoveling until you’ve got a pile so big, someone has to notice.

To tweak the metaphor: while building his own ladder—career as a cottage industry—he kept a signup sheet handy, asking for buyers’ names and addresses everywhere he sold books. His 1991 effort was called How to Hypnotize a Chicken. When that New York agent noticed an article he’d written, his third and fourth self-published books constituted his resume that landed her representation.

His mailing list paid off for Population: 485, which got a push by his publisher, Harper, only after its marketing department saw “something happening” in the hinterlands. It was Perry’s humble postcard campaign. Now he compiles both an email and a snail-mail list of book buyers. (And for those who purchase from him CDs of his music, too.) But he still controls the names he collects, as keeper of his own database, even as his publisher now foots the bill for mailings to it.

He runs hard, still writes a weekly newspaper column. He told us that even with Harper asking him for books after Population: 485, its editors “rejected the next two.” It was unclear if those were proposals or actual books. Because in 2005, only three years later, he followed up with a collection of essays, Off Main Street: Barnstormers, Prophets, and Gatemouth’s Gator.

Our hospice branch probably couldn’t have gotten Perry, except he was on book tour for his latest, a young adult novel called The Scavengers. (His next book is an adult novel called The Jesus Cow, about a Holstein with a Christ-like image on its side.) He was an inspired choice as a speaker for hospice because he’s a nurse by training—he renews his certification every two years, he told us—and because Population: 485 is grounded in his work as a paramedic in his hometown of New Auburn, Wisconsin. His mother is a nurse, and he took EMT training with her and a brother in 1988.

He grew up on a small dairy farm, but the mainstream images that conjures get adjusted by specifics. As when he tells us, “I was raised in an obscure fundamentalist Christian sect.” With perfect timing he adds, “I like to tell people that to scare them. It was very gentle.” He’s a farm boy in the way Bruce Springsteen is just a kid from blue-collar New Jersey. Yes, plus . . . He’s a bone-crushingly good writer. In Population: 485 Perry alludes to the death of a brother and a sister in childhood. He’s very quiet about such matters, though his restrained depiction of a sister-in-law’s tragic death is a centerpiece of the book.

One of my favorite stories in the memoir concerns an ambulance run made by Perry’s brother. A poor, ill, elderly woman has summoned emergency help, by pressing the button on the LifeLine monitor she wears, because her aged goose has collapsed—maybe from sunstroke. As the paramedics get the bird under shade, the police reprimand its master for sounding such an alarm over a mere goose. Later she writes an apology letter to the medics. The story is very funny and very sad. When I told Perry how much I admired it, he said a woman in a wheelchair came to one of his appearances and said, “I’m the goose lady.”

You want to say about Perry that he had the wisdom to stay put and mine his material. Except that he’s got a touch of wanderlust—and whatever difference it is that makes someone an artist. The one who chronicles stands somewhat apart. His time away from New Auburn before he returned and joined the fire department is murky. That’s the half-in-shade side of Mike Perry, the aesthete who loves obscure words and who calls poetry “my first love.” Hence the bookish high school football player came back pale, with long hair and soft hands.

Growing up, he says, television was banned in his home, but his mother was a voracious reader. He taught himself to read at age four, and in third grade read All Quiet on the Western Front. He also inhaled the western novels of Louis L’Amour. Perry is a compact man, and despite his hardy EMT work and outdoorsy pursuits there’s a physical delicacy and an elfin quality about him. With his expressive dark eyes and ready smile, he exudes warmth. It was easy to picture him as a child in one story he told about himself learning to read.

His mother, with her own book from the library, would read a chapter of hers and then read aloud a chapter of his. While she bent over her chapter, little Mike held his book beside her. Sitting quietly and patiently with a story in his hands, he awaited the full revelation of its promise and its mystery. And began to pick out words. In this image—of a tiny boy in a big chair, holding a book beside his reading mother—literature is indistinguishable from love.

August 13, 2014

Lepucki’s post-apocalypse novel

California by Edan Lepucki. Little, Brown and Company (Hachette Book Group), 393 pp., $26.00.

Guest Review by Lanie Tankard

“The threat to the planet is us.”

The plot of Edan Lepucki’s debut novel California is quite absorbing, but the story about her book is pretty engrossing as well. First a recap—then a review. You can click on any highlighted words for more information.

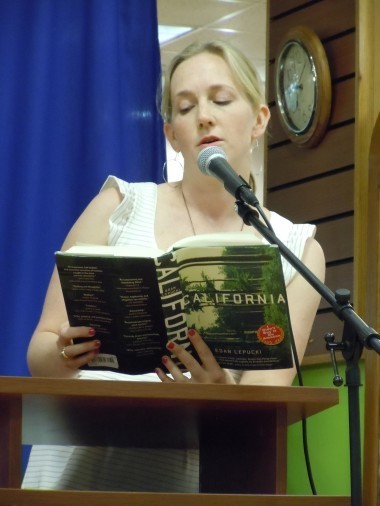

Award-winning author Sherman Alexie was a guest on ’s television show, The Colbert Report, June 4 to discuss the dispute between Amazon and Hachette Book Group. Books by both Alexie and Colbert are part of the Hachette Group, as is Lepucki’s novel. Colbert had asked Alexie to recommend a forthcoming Hachette book that he liked. Alexie picked California. Colbert held up a copy of the book and implored his viewers, “the Colbert Nation,” to preorder California (but not from Amazon) to demonstrate their power. Powell’s Books in Portland, Oregon, agreed to handle the process. Before long, Lepucki found herself signing over 10,000 copies in just three days to meet those preorders. California was published July 8. Then, on July 21, Lepucki herself was a guest on The Colbert Show. Her book tour included a talk on July 30 at BookPeople in Austin, Texas, which I caught.

“I didn’t realize how much power Colbert had,” Lepucki told the audience. Someone asked how the unexpected event had changed her life.

“I’m in a different city every day. I know how hotels work now,” she replied. “It’s no stage. I’m on this publicity machine that is like a real monster. I figure it’ll end by September. I’m still a good ol’ girl.”

Does she feel comfortable in her role against Amazon?

[Lepucki photo by Lanie Tankard.]

Lepucki is a staff writer at The Millions. “I’ve worked at a bookstore,” she explained. “I’ve bought only one book from Amazon in my life. I believe a diverse book market is a better book market. My husband works for Goodreads.” California is dedicated to Patrick Brown, director of author marketing at Goodreads—which is now owned by Amazon. (And there’s actually a bit of a dispute going on there, too, amongst readers.)What books does Lepucki herself recommend? She left some suggestions at BookPeople.

That’s the news brief for the book California—but what of Lepucki’s actual novel?

In her story, she creates a dystopia, defined as “an imaginary place where people are unhappy and usually afraid because they are not treated fairly.” This dystopia follows an apocalypse, any universal or widespread destruction or disaster that could spell eventual doom pointing to the end of the world. Lepucki’s California apocalypse has already occurred when the first chapter begins.

The author places a young married couple into an isolated spot and offers them alternating chapters to present their individual perspectives. Through their dialogue and thoughts, Frida and Cal gradually reveal the barebones backstory of the forces that drove them to flee Los Angeles. In slow but sure fashion, Lepucki sprinkles enough crumbs of information to create a hazy scenario of the forces that intersected: natural disasters like earthquakes, rampant crime, economic and digital divides, and severe weather that ran amuck in such forms as extreme snowstorms. Frida and Cal traveled as far as a lone can of gas would take their car, and then abandoned the vehicle to walk deep into a forest to begin a new life. Lepucki details their day-to-day activities and delves into their relationship. Frida becomes pregnant and they begin to encounter other people. Her brother, Micah, was Cal’s college roommate and is the third protagonist. To reveal much more would be unfair to potential readers.

What drew Lepucki to this theme?

“I don’t think too hard about why I’m writing,” she said in Austin. “I heard the phrase post-apocalyptic domestic drama and thought it sounded pretty cool. I was stopped at a red light in LA and all the lights went out. That was eerie. I thought about it a lot. I wanted the book to be about a marriage, so I made it both intimate and larger.” She actually examines a number of relationships—between couples, siblings, close friends, and group members.

Lepucki says her favorite aspect of the writing process is “the daydreaming part, before you put anything down on the page—just living with the characters and doing mental marinating. I love to write sentences.” And the hardest facet of writing? “Every part is both totally frustrating and totally exhilarating.” She had been writing in first person, “so it was cool to shift to close third” for the novel.

She credits her editor, Allie Sommer at Little, Brown, for a lot of assistance in the world-building process.

“I was her first book. She’s quite young. She gave it her all. She didn’t let me get away with anything.It was three years before I sold her my third draft, so it was about four years for the project.”

Within the eroded despoiled world Lepucki created, she calls attention to disparity between various classes: rich/poor, male/female, educated/uneducated, parent/childless. Leaders attempt to placate the lower divisions to make them happy with their status, a feat difficult to accomplish amidst totalitarian rule by fear. The plot probes the ideas of marriage, motherhood, and elimination of the family unit. Lepucki told her Austin listeners she was writing California with her newborn baby.

“Giving birth shows up in post-apocalyptic narrative a lot,” she noted, “as in The Children of Men.”

Social, economic, and political indicators in California point to a failed state, one larger than the actual California. Little wonder then that mind and population control in the novel combine with mass surveillance and result in conspiracies to overthrow various leaders.

Characters in the story repurpose things as they craft their new habitats. They fashion tall spires called the Spikes out of cast-off items wired together. Reminiscent of the Watts Towers in LA, the Spikes serve as a barrier, much like a moat does for a castle. Lepucki utilizes the Spikes as a trenchant metaphor about materialistic excess and waste, offering a silent commentary on the built world. Look around today and you see assorted structures made with repurposed objets trouvés (found objects), running the gamut all the way from shipping container architecture to the Cathedral of Junk in Austin, Texas.

One Austin reader asked Lepucki if California was “a statement about anything,” pointing out that “there are undertones of different social issues happening in the world now.”

“No,” she declared. “I’m a feminist. It’s set in the future. There’s smaller-scale sexism. I was interested in exploring this in a relationship like a marriage. I had no timetable, no storyline. I work almost entirely by intuition. I’m usually a couple chapters ahead of myself. I have an image but don’t know where I’m going. If I have an outline, it’s no fun for me.” She feels “a writer’s relationship to the world he or she lives in” is less important. “Writers should just wholly inhabit the characters they’re writing about. That act alone seems political in and of itself. If I set forth ideas about what we should do, it would be too…” (and she trailed off).

While Lepucki’s tale is not prescriptive, it does encode a warning by the very nature of the author’s societal observations. Doris Lessing touched on this idea once in an interview published in The Paris Review:

“I think a writer’s job is to provoke questions. I like to think that if someone’s read a book of mine, they’ve had—I don’t know what—the literary equivalent of a shower. Something that would start them thinking in a slightly different way perhaps. That’s what I think writers are for. This is what our function is. We spend all our time thinking about how things work, why things happen, which means that we are more sensitive to what’s going on.”

[Lepucki photo by Lanie Tankard.]

Just as Lepucki was surprised by the power of Colbert, she may be equally startled to discover the influence her book could have in prompting questions about current issues. For example, here are some of the questions that one thread in California provoked for me: What is a gate? Why do we build them? Do gates keep something out, or do they keep something in? By putting up barriers, do we hope to keep everything hunky-dory on our side while blotting out our view of all that is not on the other side? Are gates always physical, or do we erect them in our minds as well by cordoning off our thinking? How do we find points of access through gates, or better yet—dismantle them?Simply by designing an imaginary post-apocalyptic setting formed of contemporary societal problems, Lepucki pursues in various ways the traditions of books such as Lessing’s Memoirs of a Survivor, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed, The Hunger Games (Suzanne Collins) and Divergent (Veronica Roth) trilogies (as well as the Orange County trilogy, also known as The Three Californias, by Kim Stanley Robinson), A Clockwork Orange (Anthony Burgess), Peter Heller’s The Dog Stars, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale.

Indeed, Lepucki told her Austin audience that Atwood’s novel about futuristic control of women’s bodies “is my favorite of that genre.” And there is a certain type of bond between Lepucki’s Frida and Atwood’s Offred, perhaps what Ursula K. Le Guin called “the Sisterhood of Woman.” But what to call this entire type of novel?

Atwood has discussed the nomenclature of what she terms speculative fiction with Ursula K. Le Guin, who had argued for the term science fiction in a Guardian review of Atwood’s book The Year of the Flood. Le Guin said one of the things science fiction does is to “extrapolate imaginatively from current trends and events to a near-future that’s half prediction, half satire.” Lepucki seems to pursue a trifecta of sociology, satire, and speculation in California. When she builds a treehouse as a retreat for one of the main protagonists, it feels like a nod to Italo Calvino’s Cosimo from The Baron in the Trees.

Then there’s the term social science fiction used by Isaac Asimov. Sociology-oriented science fiction takes current problems and plays them out to possible future scenarios, offering readers a chance to consider the consequences of allowing situations to continue unchecked—and thereby the opportunity to decide whether action should be taken to halt them. Christopher Leslie has explained: “The social science fiction after World War 2 is supposed to work on the principle of ‘what if.’ According to practitioners like [Arthur C.] Clarke, John Campbell, Isaac Asimov, and Robert Heinlein, the technique of science fiction should be akin to speculation. The presentation of a definite and knowable space as a representation of a knowable future does not create room for speculation. If the future is set, then speculation cannot happen.”

Lepucki is definitely speculating in California. She’s also satirizing as she imaginatively predicts. Her book is not so much an end-times Armageddon as it is a heads up. I happened to be reading The Star Thrower by Loren Eiseley when I wrote this review, and ran across a sentence that nailed Lepucki’s California for me: “There was something in the desperate nature of the world that had to be reversed.”

The gentrification effect is certainly real. Climate change is here. Difficulties in marital communication exist. Sexism? Take a look at the Everyday Sexism Project started by Laura Bates. Roving gangs, suicide bombers, terrorist cells, debates about birth/motherhood/families and religion…the list goes on.

Lepucki’s thoughtfully constructed world felt authentic, but it was not without glitches. Several threads, such as the weather, didn’t play out fully. Occasional weak dialogue undercut the impact of some scenes. Even so, this novel kept me reading. Perhaps it comes down to the writerly question Atwood once posed: Will readers “find the story compelling and plausible enough to go along for the ride”?

Rather than using war or an epidemic, Lepucki employs the allegory of gated communities that keep out those who are different. City infrastructures collapse as the economy self-destructs. She uses group dynamics to examine the erection of hierarchies. She shapes a scenario that scrutinizes the process by which people get to belong—or not. Lepucki may not have planned her book this way, but California could become an editorial cautionary tale evaluating current trends and challenging readers to reflect deeply.

Lepucki leaves open for discussion the ultimate hero of her story. Is it Frida or Cal? She parses the I-Thou communication in their marriage relationship to great effect, and leaves enough seeds by the end of the novel that could develop into later troubles. Will there be a sequel? Perhaps another trilogy? Not soon.

“I’m working on another book,” Lepucki said in Austin. “I don’t talk about a book I’m working on, but I’ll say it takes place in contemporary times and is about ladies with problems. I may return to the world I created in California at some point, but right now I’m glad to be working in the present time.”

Meanwhile, California delivers a clarion call. The realm Edan Lepucki imagines in California is where we could all be headed—unless, of course, we’re already there.

Lanie Tankard is a freelance writer and editor in Austin, Texas. A member of the National Book Critics Circle and former production editor of Contemporary Psychology: A Journal of Reviews, she has also been an editorial writer for the Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville.

August 6, 2014

Hampl’s ‘Blue Arabesque’

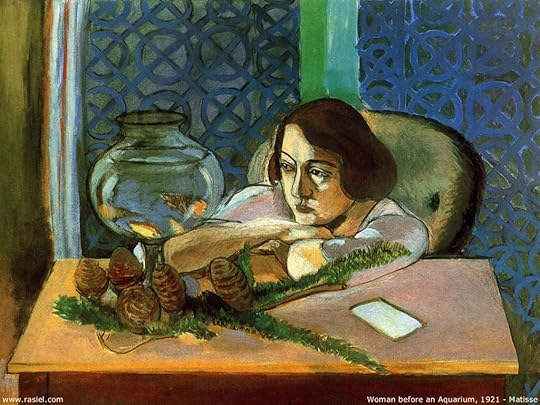

[Matisse’s woman dwells “in an ancient lyrical relation to the world.”]

A memoir of leisure, looking, and artistic expression.

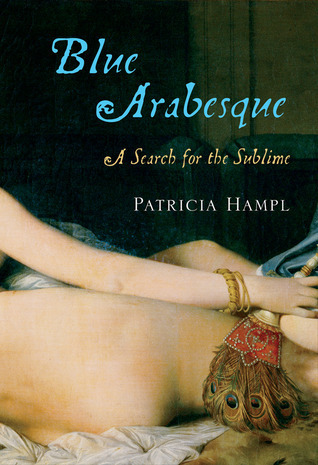

Blue Arabesque: A Search for the Sublime by Patricia Hampl. Harcourt, 215 pp.

Blue Arabesque opens with Patricia Hampl’s discovery in the Chicago Art Institute of a painting by Henri Matisse, Woman Before an Aquarium. Hampl was a recent college graduate writing fiction and poetry, but she knew little about art when the painting transfixed her as she rushed to meet a friend in the museum’s cafeteria. Her friend told her it was a lesser painting. Yet it spoke to Hampl: “Looking and musing were the job description I sought.”

Blue Arabesque opens with Patricia Hampl’s discovery in the Chicago Art Institute of a painting by Henri Matisse, Woman Before an Aquarium. Hampl was a recent college graduate writing fiction and poetry, but she knew little about art when the painting transfixed her as she rushed to meet a friend in the museum’s cafeteria. Her friend told her it was a lesser painting. Yet it spoke to Hampl: “Looking and musing were the job description I sought.”

Who is the mysterious woman in Woman Before an Aquarium and what does she mean? She with her almond eyes mirroring the goldfish? Hampl figures she’s a writer—see the notebook—and she’s posed before a Moroccan screen, which “hints at a mysterious aqua beyond,” that Matisse fetched back from North Africa. Of equal import, Who is the bookish girl captivated by the gazing woman? We’ll learn more of her, in time, and of her deep, defiant affinity for Matisse’s “decorative instinct.”

Her now-lengthy inquiry yields this core insight about the relationship among art, craft, and self:

A painting must depict the act of seeing, not the object seen. Even if that object represents an entire exotic world, it must pass through the veil of the self to be realized—to be art. For it is the artist’s fully engaged sensibility—mind/heart/soul—that is really at stake for modernity. For all the critical complaint about the narcissism of modern artists, the twentieth century demanded self-absorption of its great ones: Don’t give us your skills, give us your attitude.

Hampl’s narrative, moving chronologically through her life of consuming art, is diffuse. This risks losing readers, but you come to see and to savor her journey. And to appreciate the slow, indirect, and subtle self-portrait that emerges. Classed by its publisher as a memoir, it isn’t exactly. More like a book-length essay (nicely divided into seven chapters) that’s deeply and intrinsically personal and obliquely memoiristic. A meditation on the arts, on looking, and on the “leisure of great private endeavor” needed to make art, Blue Arabesque moves from story to story—about paintings and their creators, especially Matisse, but also Hampl’s “pagan saint,” writer Katherine Mansfield, and an obscure filmmaker from Hampl’s hometown.

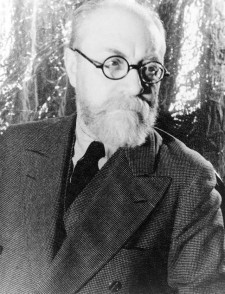

[Henri Matisse, 1869–1954.]

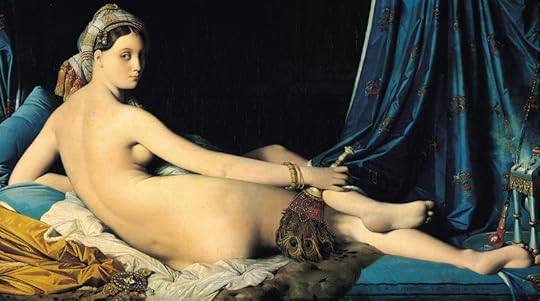

Motifs in Blue Arabesque include North Africa—whose mythical odalisques (concubines) captivated Matisse and some fellow painters and sent them across the Mediterranean to see—and the French Riviera, where Matisse and other aficionados of languid women did much of their work. It’s where the odd filmmaker moved from frigid St. Paul, where Mansfield wrote some of her most famous stories. And where Hampl, having paid a call in Turkey two chapters before, visits to write in middle age. Wrapping up the book, she’s as well a humble, foot-sore, loafing tourist. She pays a call to Matisse’s late creation, a chapel near Cassis, where she meets his last muse, now elderly and a nun.Not everyone is a reader or a simple looker and “it’s been smashed—the long reign of slowness.” But if you’re too busy to consume art, might you miss life itself? Or is ample loafing and looking enough? As for those who labor to make, Hampl makes clear it’s idle travel that undergirds “the hunting-and-gathering civilization that is artistic endeavor.”

She writes late in the book:

I’ve been here off season, which makes Cassis and all the towns I’ve visited along the Riviera these past months seem old fashioned because empty, the social world slow enough for conversation, for banter, for the sitting-and-staring that is the core of living: the just looking of the artist life. . . .

Sitting here, a person without any employment except to look. I have an uncanny sense that all things here in this light, the world itself and all its haphazard parts, have a way of coming together to form something—the sun, the lick of the morning air off the sea, shopkeepers leaning on big brooms, gulls sweeping the sky, the ruined medieval chateau on the crown of the bluff across the harbor almost effaced in the light, insubstantial but enduring like the past as it recedes and enriches itself in the mind.

That lovely final sentence of 82 words shows as well as anything how rich Blue Arabesque is in implication. Which lends it an ineffable painterly quality, this unified work of art about one writer’s love of artistic expression. With a deft touch, Hampl has created a book as beautiful as its title.

[Kathryn Harrison reviewed Blue Arabesque in the New York Times Sunday Book Review. Anne Lamott has a new essay at Sunset about making time to dwell in beauty, arguing that today's manic forms of connectivity are hostile to this, saying "creative expression, whether that means writing, dancing, bird-watching, or cooking, can give a person almost everything that he or she has been searching for: enlivenment, peace, meaning, and the incalculable wealth of time spent quietly in beauty."]

[Concubine queen with a “cello back”: Grande Odalisque, Jean Ingres, 1814.]

July 30, 2014

Three fine online essays

[Eunice Tiptree @ Writers for Dinner.]

The blogsite Writers for Dinner offers Eunice Tiptree’s artful micro essay “The Boy and the Corn Stalk”—only 653 words—which is a boyhood story that flashes forward to an adulthood realization. I adore it. This essay, employing an unusual third-person point of view, possesses the strangeness of art.Here’s the Gertrude Stein-ish sing-song once-upon-a-time opening:

Once there was a little boy, just one little boy even though this was the late 1950s and there were lots of little boys and little girls too. There were lots, but this little boy lived far away from them in a place he though the center of the world, a place of fields filled with rows of shrubs, a nursery filled with plants with Latin names. This was the 1950s and the little boy loved to sit on his daddy’s lap in the big chair as his father napped on Sunday afternoons, the only time the work paused.

A mythic tone suffuses “The Boy and the Cornstalk,” which is haunting—yet it’s a commonplace story of childhood. It concentrates childhood. Which makes the simple story, one about an apparently trivial early loss, poignant. Tiptree accomplishes so much with implication. Then she makes a huge leap forward in time to the character’s adult insight—also commonplace on the surface yet rare in portraying a resonant inner moment. I think this realization packs a punch because yet again she captures something deeply personal that’s at the same time a universal experience.

You might wonder how this can be an essay since it’s about a boy yet the writer’s name is Eunice. Her bio, at the end, explains.

“The Empathy Exams” by Leslie Jamison

[Leslie Jamison.]

I find it difficult to believe that The Believer still offers online to anyone Leslie Jamison’s sophisticated essay “The Empathy Exams,” which is the title essay of her hot new book, a compilation of her essayistic and journalistic inquiries into her own and others’ pain. The New York Times Book Review called the collection “extraordinary”:This is an approach fraught with dangers, which necessitates walking an ethical tightrope between voyeurism and narcissism, between an unnatural interest in the woes of others and an unattractive obsession with the wounds of the self.

Jamison’s focus on empathy is interesting in itself, and she makes an impressive number of rhetorical moves in the title essay. Strong exposition? Check. Vivid, dramatic scenes? Check. Braids or multiple story lines? Check. “Hermit Crab” or stolen structure? Check. Inquiry via imagination into others’ subjective worlds? Check. An essay of virtuoso technique, powerful content, and stunning length (my single-spaced download is 24 pages), “The Empathy Exams” even incorporates scientific research and quotes Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments.

Jamison launches her foreground story gracefully. Working as a “medical actor,” someone employed to help medical students hone their diagnostic and empathetic skills, she becomes curious about empathy—and its de facto student. Often she portrays a woman named Stephanie Phillips, who sometimes suffers from a seizure disorder caused by sorrow over the death of her brother. Jamison and her fellow actors are a motley crew, and they play a motley crew of ailing, grieving, and delusional patients:

We gather in clusters: old men in crinkling blue robes, MFA graduates in boots too cool for our paper gowns, local teenagers in ponchos and sweatpants. We help each other strap pillows around our waists. We hand off infant dolls. Little pneumatic Baby Doug, swaddled in a cheap cotton blanket, is passed from girl to girl like a relay baton. Our ranks are full of community-theater actors and undergrad drama majors seeking stages, high-school kids earning booze money, retired folks with spare time. . . .

Between encounters, we are given water, fruit, granola bars, and an endless supply of mints. We aren’t supposed to exhaust the students with our bad breath and growling stomachs, the side effects of our actual bodies.

And then, having hooked you into this compelling underworld, Jamison adopts the format of her work’s medical-actor scripts to reveal her accidental pregnancy and her desire to terminate it. Backstory follows, along with Jamison’s struggle with the emotional distance between her boyfriend and herself. And then the trifecta: she needs heart surgery to repair a defect. This new personal medical thread—dramatic, distressing, and ironic all at once—also offers mordant humor because her female cardiologist has the bedside manner of Godzilla.

Deeply and appealingly personal, “The Empathy Exams” achieves as well a reflective distance as Jamison explicitly looks back in time at herself and implicitly through her structuring, especially her Hermit Crab passages. Those medical-actor scripts she adopts for parts of her pregnancy and heart crisis narratives deepen the pleasure of seeing someone shape her experiences into art.

While “The Empathy Exams” is itself a master class in essay technique for those who care to study it, Publishers Weekly offers Jamison’s “How to Write a Personal Essay.” Condensed and philosophical, it’s rich fodder for students and writers struggling with the form. I can’t imagine that many others will have a clue what she’s talking about:

When I talk about writing essays that resonate beyond the personal, I don’t mean that personal material isn’t sufficient. Of course it is. Or, it can be. If you honor the complexity of your own life—if you grant us entry into moments that hold shame or hurt or heat, and if you’re willing to follow that heat, to feel out where all the small fires burn, then your readers will trust you. They’ll find flashes of themselves.

“Brazil’s Secret History of Southern Hospitality” by Stephen Bloom

[Stephen G. Bloom @ Cedar Rapids Gazette.]

A pleasing amalgam of journalism and personal essay with memoiristic touches, Stephen G. Bloom’s “Brazil’s Secret History of Southern Hospitality” at Narratively tells a wonderfully weird story. It seems that some 7,000 alienated southerners moved to Brazil after the Civil War, and Bloom traveled to Americana, a city near Sao Paulo, back in 1979 to meet a few elderly remnants.Bloom was just out of college, the fledgling editor of an English-language newspaper. He recalls:

On the front porch that afternoon thirty-five years ago, facing this grinning man, what I remember most wasn’t just the words that floated from his mouth, but how they sounded. As they hung in the moist air between us, nothing quite computed. The man spoke an American English that, while wholly fluent, sounded nothing like I had ever heard before. There was the cadence, a slow molasses drawl, but there was more. The words sounded like they came from deep within the bowels of Georgia, maybe just north of Macon, where the gnat line begins. . . .

My eyes must have betrayed me, because when I told Jim that I hadn’t read much about this Southern Shangri-La, he looked at me kind of pitifully, then put his hands out, palms up. The reason for my ig-nor-ance, as Jim put it, was plain and simple. “It’s becuse ya his-to-ry buks don’t whant ya Yan-keys ta know what hour brave Con-fed-a-rit ancestahs dahd. Dat’s dah reason. Doze ah Yan-keys who wroht doze buks—dint ya know dhat, Stephen?“

This story captivated Bloom, who says he returned to the colony three times—presumably hoping there was a book there. His funny and skillfully dramatized essay may have to suffice.

Bloom is the author of several books, including Inside the Writer’s Mind: Writing Narrative Journalism and Tears of the Mermaid: The Secret Story of Pearls. His writing has sometimes been controversial, especially “Observations From 20 Years of Iowa Life,” which was published in December 2011 in the Atlantic, just before the Iowa Caucuses. A professor of journalism at the University of Iowa, Blooms calls his adopted state “schizophrenic, economically-depressed, and some say, culturally-challenged.” He mentions Barack Obama’s unguarded comments in San Francisco about people clinging to guns and religion in the depressed Midwest. He continues:

It’s no surprise then, really, that the most popular place for suicide in America isn’t New York or Los Angeles, but the rural Middle, where guns, unemployment, alcoholism and machismo reign. Suicides in Iowa’s rural counties are 13.55 per 100,000 residents; New York’s suicide rate is 5.4 residents per 100,000. Hunting accidents are common, perhaps spurred by the elixir of alcohol, which seems to be the drink of choice whenever a man suits up in camo or orange overalls.

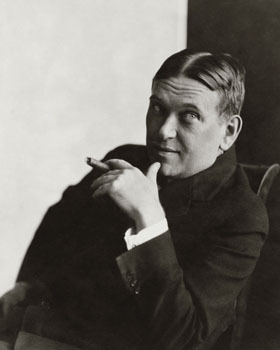

[H.L. Mencken, provocateur.]

In response howls of outrage by Iowans and some of his university colleagues, Bloom called his essay a satire. It does read as if he’s having good mean fun rubbing noses in the “heartbreaking real version” of America’s mythologized and sentimentalized rural heartland. Though his essay might have used a tweak in its snark-to-affection-to generalization ratio—this seems the polar opposite of empathetic—I was impressed by his knowledge. And you wonder if America could stand Mark Twain’s fierce wit today. Actually the literary precursor and probable influence here is journalist and satirist H.L. Mencken, who relished heaping scorn on intellectual bozos, Southerners, and places he considered ridiculous, such as Oklahoma. Consider Mencken as you read Bloom’s punchy (though less orotund) sentences here, just before he accuses Iowans of being inbred:Almost every Iowa house has a mudroom, so you don’t track mud or pig shit into the kitchen or living room, even though the aroma of pig shit is absolutely venerated in Iowa: It’s known to one and all here as “the smell of money.”

Bloom’s comments about Obama apply to his own piece:

Obama might have been wrong for telling the truth, which seldom happens in politics, but the future president was 100-percent accurate when he let slip his comments on the absolute and utter desperation in America’s hollowed-out middle, in particular in the state where I live.

July 23, 2014

6 years of unused blog posts

Good and bad, I define these terms

Quite clear, no doubt, somehow—Bob Dylan, “My Back Pages”

Among 66 aborted uploads: Franzen & Smiley on art & suffering.

I’ll probably be blogging a year from now, but whether this particular blog will achieve the ripe age of four, or the senescence that is five, is unclear.—my reflections upon the blog’s second birthday

[Philoctetes fans his suppurating foot.]

After six years of blogging, I count 66 items in my “To Be Posted” folder. Duds. Unused quotes, started essays, finished posts. Stuff I forgot or abandoned. Yet I’ve run with many a notion and hated it. Or uploaded flops.No need to pick scabs here. Well, maybe one—my February 2014 post “Art and Suffering,” in part concerning Philip Seymour Hoffman, which helped me decide I disagree with its implication. I doubt his tough roles contributed to his emotional burden and thus his death from a heroin overdose. Writing can be clarifying if only in that way. State something and see if you agree with it.

Yet I can’t abandon completely the sense that there’s often some relationship between troubles and talent. (What about the sensitivity that made Hoffman an actor in the first place? What about all his money and his acres of down time?) All the same, I heard a writer say this recently about a poet who took her own life:

Writers don’t kill themselves. People kill themselves. Writing is what kept her from killing herself for years.

My conflict about this old issue, explored at book-length in Edmund “Bunny” Wilson’s classic The Wound and the Bow—the title refers to the gifted Greek archer Philoctetes, who suffered from an unhealed wound—caused me to abort a similar effort after the Hoffman post because it depressed me too much. And I figured readers would hate it. (For what it’s worth, Wilson considered suffering an “attendant circumstance of talent, not the cause,” in the words of Janet Groth, who introduced my edition.)

Here’s that held post, more or less.

Jonathan Franzen’s “Two Ponies” essay

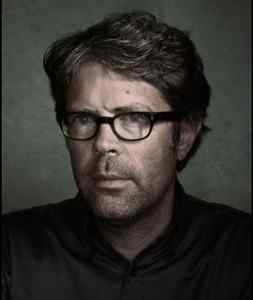

[Grizzled: Jonathan Franzen.]

I’m sort of obsessed with Jonathan Franzen’s essay depicting a turbulent period in his family’s life when he, as a boy, was immersed in the cartoons of Charles Schulz. For starters, I love the braided structure it employs; second, it’s an unusual hybrid of personal and memoir essay form. Then there’s its compelling and vexing content.“The Comfort Zone” ran in the New Yorker on November 29, 2004 (it’s still available on line); it appears with some significant additions (or maybe with cuts made by the New Yorker restored) as “Two Ponies” in his 2007 memoir of linked essays The Discomfort Zone: A Personal History.

The book’s version is much darker—and better, I think. In it, Franzen alleges that Schulz was an overly sensitive kid who managed to scar himself despite having two loving parents. Schulz obsessed over the fact that someone always had to lose, and was ostracized in high school, or felt he was, as a hick. (Another blow: his charismatic older brother drowned as a young man.)

Then in “Two Ponies,” Franzen addresses why the phenomenally successful Schulz spent a “withdrawn and emotionally turbulent” adulthood:

Was Schulz’s comic genius the product of his psychic wounds? Certainly the middle-aged artist was a mass of resentments and phobias that seemed attributable, in turn, to early traumas. He was increasingly prone to attacks of depression and bitter loneliness (“Just the mention of a hotel makes me turn cold,” he told his biographer), and when he finally broke away from his native Minnesota he set about replicating its comforts in California, building himself an ice rink where the snack bar was called “Warm Puppy.” By the 1970s, he was reluctant to even get on an airplane unless someone from his family was with him. This would seem to be a classic instance of the pathology that produces great art: wounded in his adolescence, our hero took permanent refuge in the childhood world of “Peanuts.”

And then—there it comes!—is Franzen’s breathtaking assessment of the perils of full-time art-making:

Schulz wasn’t an artist because he suffered. He suffered because he was an artist. To keep choosing art over the comforts of a normal life—to grind out a strip every day for fifty years; to pay the very steep psychic price for this—is the opposite of damaged. It’s the sort of choice that only a tower of strength and sanity can make. The reason that Schulz’s early sorrows look like “sources” of his later brilliance is that he had the talent and resilience to find humor in them. Almost every young person experiences sorrows. What’s distinctive about Schulz’s childhood is not his suffering but the fact that he loved comics from an early age, was gifted at drawing, and had the undivided attention of two loving parents.

He suffered because he was an artist.

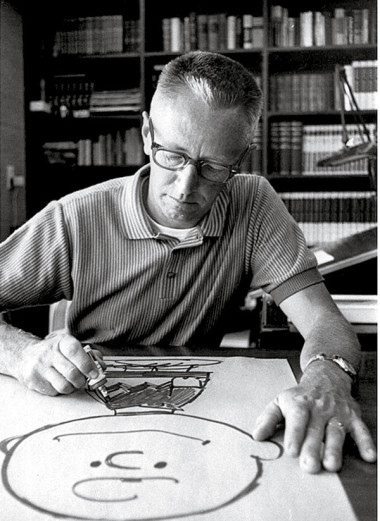

[Charles Schulz draws Charlie Brown.]

This from one of America’s esteemed novelists, not someone whose notion of art’s dangers comes from People magazine. Suffering may reflect Franzen’s own experience of spending years in front of a word processor—or is his estimation of what Schulz’s even harder daily art-making deadline meant. Who knows?(Full disclosure. As a kid, for a while I had a dog named Charlie Brown. And as an adult, I had a weird Schulz connection. When my beloved Labrador, Tess, died, back in the early 1990s, I wrote a heartfelt email to my sister, who gave it to my mother, who sent it to my former babysitter in California, who knew Schulz and gave it to him. Lo and behold, a copy of one of Schulz’s cartoon collections arrived at my Indiana home, inscribed by him to me.)

Franzen can be provocative, on purpose and otherwise. He made maddening, fatuous assertions in a muddled April 18, 2011, New Yorker essay, “Farther Away: Robinson Crusoe, David Foster Wallace, and the island of solitude,” about his friend David Foster Wallace in regard to Wallace’s suicide.

In Franzen’s view, Wallace’s problem wasn’t so much severe depression as it was boredom and deciding to end his ennui in a warped career move. By that mythologizing act, a writer’s suicide, he chose “the adulation of strangers over the love of the people closest to him.” Granted, he was your friend, Jon, and you are privy to his widow’s horror over having to find him, hanged on their patio. But jeez Louise.

In “Two Ponies,” Franzen never explains, evidently feeling it’s self-evident, why artists “pay the very steep psychic price” for making art. And he has it both ways, alleging that Schulz poured his psychic wounds into depressive Charlie Brown and other Peanuts characters—“the selfish and sadistic Lucy, the philosophizing oddball Linus, and the obsessive Schroeder”—while actually seeing himself as his creation who is consistently a winner:

But his true alter ego is clearly Snoopy: the protean trickster whose freedom is founded on his confidence that he’s lovable at heart, the quick-change artist who, for the sheer joy of it, can become a helicopter or a hockey player or Head Beagle and then again, in a flash, before his virtuosity has a chance to alienate you or diminish you, be the eager little dog who just wants dinner.

Franzen somehow weaves all this Schulz exposition into an interesting memoir about a 1970 fight between his father and a brother—over his brother’s artistic aspirations—amidst trashed, post-1960s America. Franzen’s thinking about Schulz in “Two Ponies” seems, upon my closer analysis for this post, as muddled as his DFW essay. Even the sublime metaphor Franzen uses in its title, a line borrowed from one of Charlie Brown’s wishes, wavers under scrutiny.

Jane Smiley on the perils of artistic practice

[Not so sunny: Jane Smiley.]

Jane Smiley takes up the subject of art and suffering in her fine analysis of fiction, Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Novel. She contends that novel-writing (and I’d add memoir) is a process that becomes a transformative act: “The first person to experience the effects . . . is the novelist himself.”When Charles Dickens began to fictionalize his childhood, she says, he “became his own psychoanalyst,” and acted successfully upon his diagnosis. Though he did not escape mistakes and pain, he did make decisions that changed his narrative. And happily for him, he always thought each new book was his best—“and therefore the person he was being at the time, was the best ever.”

But Smiley warns:

Novel-writing may not work as therapy, may sink the novelist into a mire of feelings that he or she cannot resolve (it takes as much wisdom to solve a significant problem in a novel as in life), or it may persuade the novelist that some risky course of action is the proper thing to do (divorce, for example) . . .

. . . I think that a good rule of thumb is that novel-writing will make happy a person who can tolerate and enjoy an ever-intensifying experience of himself or herself. Novel-writing forces the novelist to turn inward day after day, year after year. No consolations in the form of praise, fame, money, or importance can compensate for that effort if it is painful. All feelings of unworthiness will be felt over and over again; all self-doubts, all failures of love and self respect, every sense of inadequacy will be re-experienced.

Oh, joy.

Then there’s Philip Roth’s recent bleak view:

[But writing saved me!]

Everybody has a hard job. All real work is hard. My work happened also to be undoable. Morning after morning for 50 years, I faced the next page defenseless and unprepared. Writing for me was a feat of self-preservation. If I did not do it, I would die. So I did it. Obstinacy, not talent, saved my life. It was also my good luck that happiness didn’t matter to me and I had no compassion for myself. Though why such a task should have fallen to me I have no idea. Maybe writing protected me against even worse menace.

This appears in a New York Times Sunday Book Review interview with Roth by Daniel Sandstrom on March 2, 2014. Five years before, Roth had announced his retirement, and he began rereading the 31 books he’d published between 1950 and 2010. Answering Sandstrom’s opinion of his life’s work, Roth, echoing heavyweight boxer Joe Louis, said, “I did the best I could with what I had.” (Roth’s great memoir of his father, Patrimony, if listed on my Favorite CNF page.)

Say what you will about his grim visage, Roth has a sense of humor.

And you’ll notice that in his statement about writing’s necessity, Roth is expressing the exact opposite of Franzen’s apparent point—Roth’s tortured self would have been worse without his art. He sounds as if, contra Smiley as well, his experience of himself was going to be dire even without writing.

The only matters this post have clarified for me are my feelings about “Two Ponies” and Jonathan Franzen. That is, I’m not quite as in love with the essay and I understand those who find its author irritating. Probably this post should have stayed in my “To Be Uploaded” folder, forever only a potential dud.

I was a long way from Tupelo,

A long way from Tupelo

Yeah, I was stranded in a place that nobody knows

I was a long was from Tupelo

—Paul Thorn, “A Long Way From Tupelo”

July 17, 2014

My blog turns six today!

You can hit the ground running like you’re shot from a gun

But going the distance is the hard part, son

Everybody looks good at the starting line

—Paul Thorn, “Everybody Looks Good at the Starting Line”

My six favorite posts from six years of blogging archives.

After my previous post, about quirky personal posts I recall fondly, my blogger friend Shirley Showalter asked me to discuss the benefits and difficulties of blogging in my life. In the past year I’ve struggled for the first time to post—the long energy-producing effort of drafting my memoir over. Plus having to face the What’s next? question. For most people, probably me too, blogging is a phase. For all I know, this is my last post.

So that’s the difficulty part. But the blog has helped me as a writer—kept my prose and my persona down to earth, underscored obsessions, given instant gratification. It has forced me to create something on the fly that turned out to please me and has inspired me to laboriously craft a post that has likewise surprised me. Sometimes I’ve thought, I should have done that for a real publication. But the truth is, without an existing affiliation, like this blog, I wouldn’t have.

The blog made me do it. Paul Thorn, the Mississippi blues-soul-rock musician says it best:

Whatever expression you have in you, instead of thinking about it all the time, do it. Make it tangible, you know? That’s what art is, it’s creativity made tangible.

And the blog has built community, something I’m bad at. Looking at my own book’s reviews on Amazon, it strikes me that of the current 11 reviews, four were posted by people I know only virtually from the blog, readers or nascent friendships cemented through blogging. There’s nothing wrong with promoting your product to an audience you think will like it. But the blog really was an inadvertent way by which I entered the ancient, endless conversation that is literature. It stuns me that blogging has led to my having credibility of sorts in some quarters.

Mostly I must like making sentences and feel the need. And I’m a better person the more I’m writing, more conscious and more grateful. And paradoxically, more outwardly directed. Even if my “real” writing isn’t going anywhere, I have to crank out the blog. It’s writing: it counts, it helps. It signifies my artistic endeavors, even if I’m mostly reading, are going well.

Today is this blog’s sixth birthday, July 17, 2014. Which even a math idiot like me knows means the blog and I are now officially embarking on our seventh year. So I thought I’d pick my six top posts from the blog’s existence. These are ones that I recall without trying, touchstones for me in terms of craft, literature, or my life. Three of them came right after or during vacation travel.

[An auto I saw in Frankfurt, Germany. Doesn’t it make your teeth hurt?]

November 16, 2008

Between self and story

Craft is the conduit to art — but craft mustn’t be enshrined.

Our answer is that writing is . . . not a bundle of skills. Although it is true that an ordinary intellectual activity like writing must lead to skills, and skills inevitably mark the performance, the activity does not come from the skills, nor does it consist of using them.— Francis-Noel Thomas and Mark Turner, Clear and Simple as the Truth: Writing Classic Prose

This is a very early post, from the blog’s first winter, but I was returning to an old concern, working out something, talking to myself. The background is that two decades ago, after I’d been a journalist for a while, I noticed with consternation how low-level were journalists’ discussions about craft at the newspaper conferences I was attending. This was partly because, in retrospect, I’d become a journeyman reporter. And partly because the meetings were sponsored by the Newspaper Industry—may it rest in pieces—and an industry can no more foster artistry than the state can run a farm.

What is between self and story? Craft. It’s the only thing we can really talk about because the self is so vast and its personal and artistic needs so individual. But we fool ourselves if we think that craft is the most important aspect of art. In a blog ostensibly devoted to craft, I needed to remind myself of that truth. I’ve returned to this theme again and again, memorably for me as well in “Art, craft, and the elusive self,” in “Craft, self & rolling resistance,” and in “Writing by the dangerous method,” the latter again invoking and debating with one of my favorite writing theorists, Peter Elbow.

Here’s Elbow in Writing With Power:

To write is to overcome a certain resistance: you are trying to wrestle a steer to the ground, to wrestle a snake into a bottle, to overcome a demon that sits in your head. To succeed in writing or making sense is to overpower that steer, that snake, that demon. But not kill it.

This myth explains why some people who write fluently and perhaps even clearly—they say just what they mean in adequate, errorless words—are really hopelessly boring to read. There is no resistance in their words; you cannot feel any force being overcome, any orneriness. No surprises. The language is too abjectly obedient. When writing is really good, on the other hand, the words themselves lend some of their energy to the writer. The writer is controlling words he can’t turn his back on without danger of being scratched or bitten.

January 26, 2009

Review: For the Time Being

Annie Dillard’s audacious astringent, segmented narrative.

Now if you see Saint Annie

Please tell her thanks a lot

—Bob Dylan, “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”

For the Time Being is challenging, strange, ambitious. It’s formally interesting and perfect. There’s a reason Annie Dillard is this blog’s patron saint. I admire her syntactical precision and her intellectual rigor, always buoyed by her restrained passion and informed by her spiritual quest. All the same, sometimes with Dillard I’m reading against my taste.

For the Time Being is challenging, strange, ambitious. It’s formally interesting and perfect. There’s a reason Annie Dillard is this blog’s patron saint. I admire her syntactical precision and her intellectual rigor, always buoyed by her restrained passion and informed by her spiritual quest. All the same, sometimes with Dillard I’m reading against my taste.

Her elliptical leaps and gnomic utterances can flummox me. Her persona is so restrained it’s astringent. Yet in her famous essay “Total Eclipse,” she’s frankly emotional (good) unto hysterical (not so much) under the hammer-bright surface of her prose. I want to ask, Just tell us what gives? Annie? Well, I guess she does—she loses it in her cheap motel room for the implied reason: her horror of that sudden darkness, a terror which arises from her tapping into the felt, imagined emotional response of our ancient ancestors. Then there’s that demonic clown painting on the motel wall, and it doesn’t help one bit. Nosiree.

There’s a heightened quality to Dillard’s writing; as if inspiration has arisen from layers of deeply compressed thought and feeling. In her segmented essay “Living Like Weasels,” easily found on line, she relays a naturalist’s anecdote about the skull of a weasel being found clinging to the throat of an eagle; she relates her own encounter with a weasel. And she’s off:

. . . The weasel lives in necessity and we live in choice, hating necessity and dying at the last ignobly in its talons. I would like to live as I should, as the weasel lives as he should. And I suspect that for me the way is like the weasel’s: open to time and death painlessly, noticing everything, remembering nothing, choosing the given with a fierce and pointed will.

. . .

. . . We can live any way we want. People take vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience—even of silence—by choice. The thing is to stalk you calling in a certain skilled and supple way, to locate the most tender and live spot and plug into that pulse.

. . .

I think it would be well, and proper, and obedient, and pure, to grasp your one necessity and not let it go, to dangle from it limp wherever it takes you. Then even death, where you’re going no matter how you live, cannot you part.

You want to live a more heightened life so you can write like that.

Dillard can do it at length. For the Time Being soars—a modernist masterpiece. Admittedly one of the reasons I love her work is that, like Virginia Woolf, I discovered her myself, no formal class involved. My most passionate literary affairs seem to have been strictly my own. Which is to say, they’ve arisen from the passions shared by other common readers, from the thin ether exuded by literature itself among its lovers and supplicants.

[Claire, 11, sledding with puppy Jack at our farm Mossy Dell, January 1998.]

April 21, 2010

Jack, our terrier

In memorium: March 20, 1997 – April 17, 2010

[Son Tom with old Jack.]

I profess to hate the literary sin of sentimentality, yet I read every essay I see about somebody’s dog that died. And how can you write about a dead dog without being a tad sentimental? So, fair warning. But I tried. Thing is, I loved Jack. He was sporty, funny, ardent. His brown eyes had olive in them; they were at once warm and feral, as inviting and impersonal as a tiger’s. In his last year, when we spent a lot of time together, sometimes he’d regard me with melting adoration. Which startled me, because it was not a good look for him and because it made me feel unworthy.His secret name—here revealed publicly for the first time—was Gomez, because he was, as well—in his good nature and unselfconscious macho swagger—a sexy devil. He was 13 when he died. A good long life for a dog. But I’d deluded myself into thinking that Jack, being small, might make it to 16 or 17. Plus, we’d moved off the farm, where he’d been marked for death. He arrived in town, age 12, stitched up over one eye—a giant possum he’d just killed in our barnyard had defended itself. Then, that first December in the suburbs, I noticed a swelling in his throat. Lymphoma.

As for the post, I tried to render it in scene to better convey my experience of loss.

July 9, 2010

Annie Dillard’s Living By Fiction

— a review and appreciation

[I took this in Florence, Italy.]

Art historically has given the illusion of being seamless. A perfect flowing utterance. But usually at least at some point there were seams, melded bits—because that’s how it’s made. Moment by moment, working it out. Slowly and sometimes painfully. In different moods, circumstances, contingencies. In joy, maybe—but it’s fear and trembling you can count on. Modernism (or certainly postmodernism) seems so much about this. Recognizing and even heightening fragmentation through segmenting, collage, lists. The old seamless ideal is more often ignored now, or even attacked—at least, the best company considers it suspect. Our world is fractured so shouldn’t our art be?Dillard discusses all this and more, including airing her useful theory regarding “fine” and “plain” prose styles and what they portend. I find her notion especially interesting regarding the ramifications of style for persona. Plain prose—spare, submissive, sharp—has carried the day, making fine efforts stick out like a sore thumb. (I made a fumbling attempt to review Joshua Cody’s fine-style [sic]: A Memoir per Dillard’s theory.)

Incidentally, I love the photograph here, an accidentally blurry snap I took about six weeks before the original post in Florence, Italy, where I’d gone with my son. Hardly anyone ever comments on the blog’s illustrations, almost always my own photos, but I enjoy them. I don’t think I’m a Photographer, but love that blogging as has impelled me to take photos that animate the blog and enrich my life.

[I shot this yew in the ruins of Muckross Abbey, Ireland.]

July 17, 2012

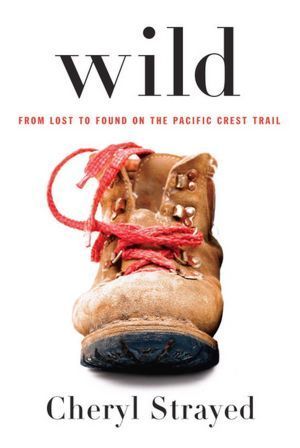

My wild summer

Reading & revising lessons from Cheryl Strayed’s memoir, Wild.

Very late in the process of writing my own memoir I read Wild and certain solutions jumped out at me. These weren’t necessarily fixes I was looking for or knew I needed. So that was exciting. I saw that I’d stupidly corralled my father in one chapter, when he needed to roam throughout—as in my memory, as in my life. So I wrote about those discoveries and also reviewed Cheryl Strayed’s blockbuster memoir.

Three days after that, I posed “Studying Wild for its structure,” about how I took my memoir apart. Four days later, in “Cheryl Strayed’s back pages,” I analyzed yet again exactly how Strayed feathered her compelling backstory into Wild and how I tried to emulate her technique. And four days after that, I uploaded “On hating a memorist,” about the backlash against Strayed and her bestseller. That post seemed hugely popular, probably because of the deeply personal responses so many have had to memoirists.

This energetic book revision and posting about came immediately after my family and I had been traveling in England, Scotland, and Ireland. Chalk one up for the benefits of travel and down time.

January 17, 2013

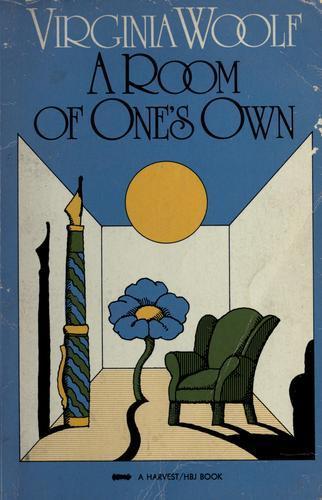

Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own

Storytelling & spirituality in Virginia Woolf’s classic feminist text.

I wrote this while on vacation, and the second headline says it all. I don’t know what I’d expected here from Virginia Woolf, like Dillard a beloved writer I discovered for myself, but probably I feared dense man-hating exposition. It is a little tough to start A Room of One’s Own, knowing if you’re male that she’s going to open a big can of whup-ass on you. But her ideas are so acute and so mordantly funny—and, most importantly, so inclusive, at last—that you join her, cheer her on in her prosecution of the patriarchy.

I mean, what if Shakespeare did have an equally genius sister? What about those endless shelves in London’s greatest library devoted to books by men trying to explain women? And then her book-length essay’s glory, content-wise: Woolf’s plea and brief for artistic androgyny. Because anyone of either sex who creates cannot be a gender chauvinist. (If only in the work, I might add, because we’ve all heard the horror stories of the writer being less than the work.) That’s the spiritual part, for me. If any Brits read this: yeah, I’m aware she called herself an atheist. Which doesn’t prevent me from drawing spiritual sustenance from her work.

Qua narrative, A Room of One’s Own awed me for how Woolf always keeps her readers grounded in time and space even as her subject and her mind move. There are scenic touches and reminders that she’s now pondering at her desk, reaching up for a book, or hying herself off to a dusty archive of male thought. As a great novelist, she’s aware of memory’s essentially fictional nature but also of readers’ intuitive rules and expectations of genre. She gives fair warning and then has her way with us—and always takes us with her.

What I’m trying to say is that A Room of One’s Own is appealing and immortal because Virginia Woolf is doing that dusty, humble thing. She’s telling a story.

Who were you loyal to?

What were you passionate about?

What did you believe in,

Beyond a shadow of a doubt?

Who were your teachers?

Did you have one true friend?

These are things worth knowing,

When the long road ends…

—Paul Thorn, “When the Long Road Ends”

July 9, 2014

Six quirky posts

Reflections as my blog approaches its 7th year.

I saw a black man with a bible and a sparkler in his hand.

He was holding a tent revival and running a firework stand.

He said the end of the world is coming, you better get on your knees.

Today bottle rockets are two for one, but salvation’s free.

—Paul Thorn, “Mission Temple Fireworks Stand”

Of course it was summer, my favorite season, when I started this blog almost six years ago. I was working on the third version of my memoir. As if the world needed another blog about writing—but that’s what excited me. It was July. Within summer, July is my favorite month—the lawns under control, the daylilies in bloom, the gin and tonic flowing. So it wasn’t too surprising that when I picked six favorite posts, to be discussed on the blog’s birthday next Thursday, that two of them were uploaded in July.

Of course it was summer, my favorite season, when I started this blog almost six years ago. I was working on the third version of my memoir. As if the world needed another blog about writing—but that’s what excited me. It was July. Within summer, July is my favorite month—the lawns under control, the daylilies in bloom, the gin and tonic flowing. So it wasn’t too surprising that when I picked six favorite posts, to be discussed on the blog’s birthday next Thursday, that two of them were uploaded in July.

What was surprising was how many of my pets were posted in December or January. Two of my top posts were uploaded in January; four of my six finalists, below, were written in December. I guess December makes me reflective. And January seems the July of winter—the leaf collection over, the Thanksgiving and Christmas frenzies past, the slower winter season still stretching out forever but not yet unpleasantly.

My 12 favorites are just the ones that swam to the surface of my mind, ones I wrote with great pleasure or maybe were about a subject I’ve continued to worry. Frequent themes that have developed include the aesthetics of nonfiction, the use of self in nonfiction, and storytelling structure.

But of the six runners-up below, not one is about writing per se.

September 14, 2008

Behind the barn:

The story of the Krendl family’s Obama barn in northwestern Ohio.

[The Krendls' barn, proud in the soybeans.]

The blog’s first fall, my wife’s sister Kris shared a great photograph she’d taken of the Krendl family’s barn near Spencerville, Ohio. I knew the barn’s and its owners’ history from years of gatherings there, plus having written about the family in my book. I loved the way the Krendl family’s progressive immigrant lineage was expressed in the barn’s history and in its new incarnation as a campaign sign for Barack Obama.At a campaign rally in Dayton, Obama got to meet some family members—also captured by Kris with her camera—whose barn was one of the few in Ohio, and none in its region, a Republican stronghold, to cheer his candidacy from amidst its fields.

Writing history is fun when it’s personal and you’re connecting the dots. In this case between a rebellious Austrian immigrant brewer and farmer named Adolph Krendl and America’s first Hawaiian president.

December 16, 2008

People understand the constraints:

Solstice musings on poetry & nonfiction & Mom’s Christmas letter.

Balancing blogging’s relentless demand to come up with something, you seize moments that might otherwise be lost. Such as this post from the blog’s first winter that immortalizes my wife’s efforts to produce our annual family Christmas letter. Her sweet efforts occurred, in life as in the post, in the face of her husband’s and children’s immature and unhelpful teasing.

What a merry moment on our old farm it brings back. And, I admit, I like my little poem inspired by that evening.

December 23, 2009

Christmas at the coffee shop:

I eavesdrop on two groups, one male and one female, as they talk.

Our first winter after moving to town, I was struck by the differences between an especially combative male coffee klatch and any of several regular female gatherings at the neighborhood Panera. Presented in dialogue and without commentary, this post amused me, even if it fosters gender stereotypes (grimly competitive politicized men, humorous emotionally attuned women).

As with the post discussed previously, it’s something I wouldn’t have done without a blog—or an obsessive writer’s notebook. Hmm . . . There’s a thought: writing stuff down without publishing it, at least not immediately. Old school. Either way possesses virtue: your self and its sensibility encountering the world and its ways.

[Misty morning at the Summer Palace, Beijing. I took this on our visit.]

December 13, 2010

With a song in our hearts:

Touring mainland China with a college choir stirs the spirit.

[Guide Kathie wears Minnie.]

I hadn’t intended on writing anything about my experiences with the Otterbein University concert choir. Too much pressure going in. And, as usual, I hadn’t wanted to travel when it came down to it; and then, as always, I was surprised by travel’s comparative difficulty. I gave up a cozy seat by my fire for an endless flight, jet-lag, and digestive upset? Yes, you did. Though this is the only travel narrative among these posts, at least two that made my upcoming best-posts list came immediately after travel experiences. Travel forces you to slow down, unplug, ponder. Thus artists of various stripes are among those who, historically, do travel.I liked the individual Chinese people I met, was sometimes appalled by their concert manners, and fascinated at their inability—these westernized survivors of an ancient land—to speak of their awful government. But you cannot rub shoulders and break bread and talk with people from another place, another race without seeing how alike we all are. What this led to was a meditation on nations’ and individual’s historic inability to include the Other under the umbrella of their God. This is my definition of a pagan, that he will not grant me access to his God, and it still afflicts some peoples and nations, whether religious or not.

But that is changing. As I conclude in the post, “the trip grew my spirit as it shrank the world.” To me, this enlargement of human spirit as nationalistic barriers fall is the meta-narrative of our time, and China crystallized it. The post’s epigraph came from Annie Dillard’s For the Time Being—in part about her own China trip—and comes close to expressing my hard-won personal definition of God as human goodness welling from our depths:

The consciousness of divinity is divinity itself. The more we wake to holiness, the more of it we give birth to, the more we introduce, expand, and multiply it on earth, the more “God is on the field.”—Annie Dillard, For the Time Being (page 40; reviewed, a top post.)

December 3, 2012

Perchance to sit:

I observe a crucial difference between adults and college students.

Our fourth winter in Westerville, I got tickled by my wife and some college students she invited to our house to mingle for an hour. I’ve had a lot of fun at Kathy’s expense, and also gotten my best material—she’s the most interesting character in my memoir, too, along with our dog Jack and our ewe Freckles. Four of the six posts here are based on Kathy’s history or activities (her job led to our taking the China trip).

Your life does provide your best “material,” so have a good one!

March 31, 2012

Memories of me and Harry Crews . . .

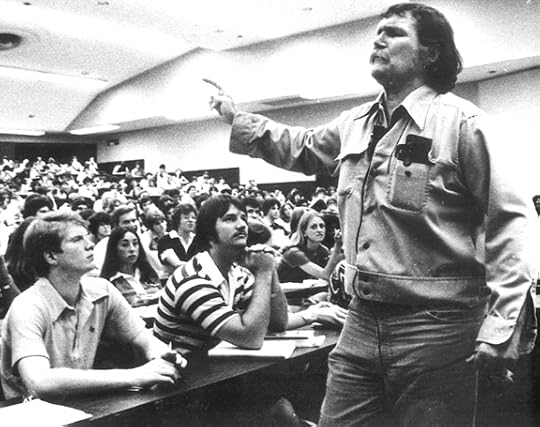

. . . but mostly of me, 1973–1977.

[Harry Crews holds forth.]

l took a long trip down memory lane when writer Harry Crews died. The resulting post made me wonder when and if and how blog posts cross the line into creative nonfiction—and whether they should. Because this post burned through a lot of material. Well, it’s still my stuff, and I can’t regret it. If I ever figure out what it’s part of, I can just paste it into that magnum opus.So many full works, from songs to novels, are made of disparate bits. I think of great Beatles songs like “A Day in the Life” that are collage. In this case, I think what happened is that I had written most of these bits, and when Crews died it galvanized them into an essay. My version of “A Day in the Life.” I heard the news of his death, oh boy, and it took me back.

[Next: I pick my six top posts from the past six years.]

[Fourth of July 2014 at our cabin in Ohio’s Hocking Hills.]

July 2, 2014

A salute to sentences