Richard Gilbert's Blog, page 7

January 6, 2016

A Mexican bard

Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press, https://www.graywolfpress.org/blogs/looking-ahead-graywolf-fiction-2015 $16.00 paperback (112 pages), November 3, 2015. Translator: Katherine Silver. Book Design: Rachel Holscher.

Guest Review by Lanie Tankard

“…let me be that I am, and seek not to alter me.”—William Shakespeare, Much Ado About Nothing

“I think you have all drunk of Circe’s cup….”—William Shakespeare, The Comedy of Errors

Mexico’s acclaimed writer Daniel Sada, who died in 2011, wrote nine novels in Spanish. One Out of Two is the second to be translated to English, both by Katherine Silver. William Shakespeare would have applauded this story, which can be viewed as a marvelous mashup of two plays: The Comedy of Errors and Much Ado About Nothing.

The Gamal sisters, twin seamstresses, enjoy confusing people about their identities. Their small world in Ocampo, Chihuahua (Mexico), is upended one day when a suitor named Oscar Segura enters the picture—but exactly which sister is he courting, Gloria or Constitución? Using this mixed-up charade as a springboard, Sada spins a yarn that weaves in zingers about love, lust, sex, identity, profession, gender roles, weddings, marriages, funerals, ancestors, truth, deception, forgetting, and the passage of time. Ingenious metaphors explore broader themes: individualism, collectivism, symbiosis, codes of honor, and values. The storyteller’s clear distinctive voice spinning this comical tale is compelling. One can practically visualize the narrator’s arms waving dramatically, eyes rolling in exasperation and widening in anticipation, while the plot advances.

One method Sada used involves unique punctuation such as repeated colons—often two, three, or four in the same sentence—to give the narrator’s delivery an attitude. Sada also applied quite liberally the one-em dash for emphasis and ellipses for pauses. Toying with these marks allows a skilled author to develop an almost audible speech pattern by pushing readers to hear words on the page differently. In a similar vein, Norwegian writer Per Petterson totally shunned question marks in his recent novel I Refuse (reviewed), constructing a particular voice that slowly ratcheted up the tension, impelling readers to listen.

[The late Daniel Sada.]

Daniel Sada’s One Out of Two raconteur steps onstage intermittently, pointing to the storyline: “Herein evolves the drama, the underbelly of the plot” or “Now let’s tell their tale.” The pundit gradually assumes a character role apart from the fiction, reminding audience members they’re being told a story, which creates a direct relationship between reader and author via narrator as in a play integrating Bertolt Brecht techniques. The commentator becomes essential to the performance yet remains outside the action. How this farce finally plays out caps off a perceptively clever comedy drama.Originally published in Spanish as Una de dos in 1994, the work became a 2002 movie directed by the late Marcel Sisniega Campbell, with whom Sada collaborated on the screenplay. Sada’s honors included the 2008 Premio Herralde de Novela from Barcelona publisher Editorial Anagrama. Hours before he died, Sada received the National Prize for Arts and Sciences in Literature from the Government of Mexico.

Seven more novels and a multitude of short stories and poems, all in Spanish, still await translation. There’s a definite treasure trove pending in the literature of Daniel Sada.

Lanie Tankard is a freelance writer and editor in Austin, Texas. She is a former production editor of Contemporary Psychology: A Journal of Reviews, and has also been an editorial writer for the Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville.

The post A Mexican bard appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

December 28, 2015

Top reads of 2015

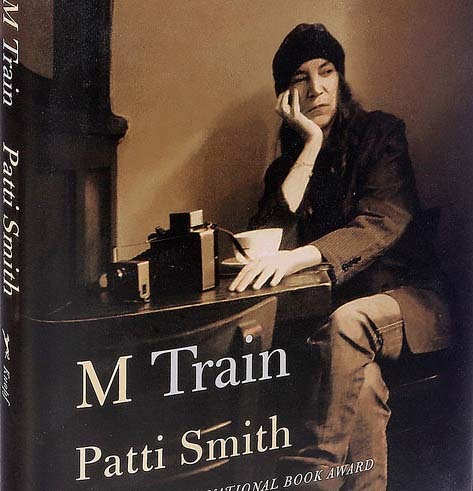

[Smith with her Polaroid camera at cafe Ino, NYC.]

M Train is a portrait of the artist in real time. Patti Smith rambles around New York City, travels overseas to attend a meeting of an odd society devoted to continental drift that suddenly disbands; she writes and muses in a beloved café near her East Village townhouse that one day simply closes. She impulsively buys a Far Rockaway beach shack that Hurricane Sandy promptly submerges. We see her consume much coffee and the odd meal—vegetarian snacks, really, they seem to keep her going. She tends her cats, falls into bed with her clothes on, somehow loses a beloved coat, leaves a special camera on a park bench. Spacey? Truly. Yet paradoxically mindful. She’s always reading, writing, drawing—and charmingly caught up in TV detective series. Her book’s title may refer to memory, where Smith spends many waking hours. Her past and ongoing lives feel deeply processed. A stoic romantic, her globetrotting habits include tending dead poets’ graves.For all this detail, she leaves out a lot. Her focus may be the key to M Train. And you always know where she is in time and space or flashback—reminiscent of Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own (reviewed)—despite scant connective tissue. She never plods in what’s basically a chronologically intercut with penumbras of backstory. There’s almost nothing on her poetry and music careers; Smith’s past lives emerge as resonant memories during her peripatetic foreground narrative. This is a widow’s story. A message from someone in her late sixties living with loss. Her husband, guitarist Fred Sonic Smith, vanished at age 45, slain by a heart attack; her beloved brother who managed her tours fell to a stroke soon after. Smith’s laconic artistry can be seen in her placement of Fred’s spare scenes. No deathbed stuff, however. And her two adult children don’t appear in this slice of life. If sadness suffuses M Train, the book isn’t glum. Shining through is Smith’s sense, lifelong and apparently innate, of divinity.

She masterfully crafts a persona even as her self-presentation appears incidental and even accidental. But make no mistake. She’s “just herself” in the same way her haunting black-and-white Polaroids that illustrate M Train are just snapshots. Sometimes humanly cranky, as when someone takes her favorite café seat, Smith mostly seems contemplative in her solitude. She warns at the outset M Train is a story about “nothing,” but it’s hardly that. While this quiet memoir is inseparable from her attainment and celebrity, it stands alone. From shards of her history and sketches of her daily life, Smith has fashioned literature. I admired Just Kids, her portrait of coming of age with her friend the late Robert Mapplethorpe, but I found M Train moving and exciting.

Other great reads of 2015

[Susan Griffin.]

• Susan Griffin’s A Chorus of Stones: The Hidden Life of War (discussed) is a mesmerizing mosaic of different but reappearing elements, including: snippets on cell biology and missile technology; WWII’s savage war on civilians; the secrets people carry about emotional and other abuse; and the Nazis, especially Heinrich Himmler, chief architect of the Holocaust, and his strict, self-denying childhood.The long essay “Our Secret,” a chapter in A Chorus of Stones, is increasingly read and assigned to students. It is an astonishing meditation on the soul-destroying price of conforming to false selves that have been brutalized by others, mentally or physically or both, or by themselves in committing acts of violence and emotional cruelty.

An extended inquiry into secret suffering, A Chorus of Stones shows how private woe can spread and erupt in the mass violence of war. Griffin offers a profound vision of human pain in this brilliant, inspired masterpiece.

• Vivian Gornick’s The Odd Woman and the City (reviewed). In August I fell under the spell of Gornick’s new memoir, really a long essay. I immediately read it again, something I haven’t yet done with Patti Smith’s, which it resembles. Gornick’s is about friendship, especially in New York City, walking in the city, and encounters with strangers in the city.

Her stories are interesting, as is her brutally honest truth-speaking voice and the funny anecdotes she tells on herself. She’s aware that, well, she’s odd. The latter is literally a reference to her feminism—she takes the term from George Gissing about feminists of an earlier era—but it alludes as well to her feeling of being broken. Like all writers (and people) she generalizes from her personal truths. This is why we read her but it’s also sometimes why I want to argue with her about her conclusions. As if she’s a friend.

• David Sedaris’s When You Are Engulfed in Flames. I listened to a good chunk of this essay collection as an audio book while driving from Ohio to Virginia and back last winter, and then I bought the book and read it. Sedaris is a superb reader of his own work, as everyone knows, which can make reading essays in the wake of that a slight letdown at first. But he’s funny, so funny, a master of persona and phrasing.

Sedaris’s prose is somehow both elegant and colloquial. He deploys his foibles with wry discernment and without self hatred. His long essay on trying to quit smoking while on an extended stay in Japan was amusing and also inspiring to me as a writer, since one could see him working his life for material almost as it happened. His best essays, however, are those about his early life and those that focus on the oddballs who roll into his orbit. After this collection I read Me Talk Pretty One Day and found it likewise entertaining and poignant.

• Natalie Kusz’s Road Song: A Memoir depicts her loving, eccentric family, their life in Alaska, and the accident that maimed her face. One of the things that sets Road Song apart is that the latter, a truly horrific event early in the story, is just one of the book’s compelling threads, an important one but not its focus. The title tells you that, in large part, this is a book about a joyous family.

What Kusz focuses on is always different and unexpected—there are so many surprises in this book. For instance, the nature of her adolescent rebellion and her family’s response. Her muscular prose, her reflective bent, and her interest in other people and in deeper meanings lend her memoir profundity. Yet it is lighthearted for a tale of so much struggle, truly loving and life-affirming. A strong, unusual memoir.

• Dinty W. Moore’s Dear Mister Essay Writer Guy (review and interview) features pervasive exaggeration, deft timing, absurd queries, addled answers, and wry follow-up essays. This sustained comedic performance also glimmers with wisdom.

Borrowing a structure, that of the advice columnist—many now call this the “hermit crab” method, after Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola in Tell it Slant—within Moore’s mega hermit crab are baby ones: essays presented as lists; as a Googlemaps essay; and as jottings on a cocktail napkin. The book’s structure is a clever container for well-crafted concise essays. I may not be as objective as some, because I know Dinty, but I was charmed and inspired by Dear Mister Essay Writer Guy. Charmed by its lighthearted spirit and inspired by how he used his writing practice and his sensibility to craft art in prose.

[Then: Macdonald with Mabel, ca. 2008.]

• Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk (reviewed) depicts her getting a goshawk to train, a challenge despite Macdonald’s birdy girlhood and prior falconry experience; this occurs as a way of coping with her father’s death, and we get glimpses of him and more of her grief and disordered state; a strong third element is her explication of novelist T.H. White’s own harrowing attempt to train a goshawk and her insights into White’s deeply damaged psyche.Macdonald’s braiding of her story refreshes, and her sentences and diction utterly delight. Here’s a morning in a few deft strokes:

Last night the forecast was bad. A storm surge threatened to inundate East Anglia. All night I kept waking, listening to the rain, fearing for the caravans along the coast, their frail silver backs against the rain and rising seas. But the storm surge held back at the brink, and the morning dawned blue and shiny as a puddle.

• Ron Rash’s Something Rich and Strange consists of fine, diverse short stories set in Appalachia. Their timeline extends from the Civil War to today. Several portray rural America’s meth problem in chilling detail.

[Patti Smith, at ease.]

The post Top reads of 2015 appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

December 16, 2015

The power of a metaphor

In The Cider House Rules, gruff yet kindly Dr. Wilbur Larch runs an orphanage in remotest 1930s Maine, where he also performs illegal abortions for desperate women. He gives them an abortion or an orphan, as they wish. His protégé Homer Wells, an orphan he retained, cannot bring himself to end fetal life. Wells takes leave to explore the world and ends up working at a coastal orchard; he becomes a bridge between its owners and the migrant workers who arrive every fall to harvest apples.

I decided finally to read John Irving’s 1985 novel because, loving the 1999 movie made from it, I’ve so thoroughly adopted Irving’s great metaphor. Cider house rules are strictures imposed by an unknowing majority on a minority group; it works for bitter corporate cubicle dwellers, farmers, and any class in between. In the novel, almost none of the pickers who live in the orchard’s bunkhouse, where they also press cider, can even read the typed rules Homer annually posts. Anyway, they have their own rules, they tell him. Soon Homer’s personal distaste for abortion will be tested by their need. And his love for a girl causes him to break other rules concerning marriage and fidelity.

A defiantly old-fashioned storyteller, Irving employs intricate plots that impress and often reward. I found The Cider House Rules a slog at times, wading through so much summary and so many years in its 560 pages; I could see why the movie, in reducing its narrative timeline from 15 years to 15 months, feels so lightfooted in comparison. But the book’s gravitas enables Irving’s patient working of his dominant metaphor.

[Irving nabs Oscar for the screenplay.]

To Irving, more is better. His doorstopper yarns explode like a brick heaved into a plate glass bookstore window; his fans await them and adore them. Maybe that’s because of his novels’ delightful heightening, a fabulist quality. This may flow from Charles Dickens’s melodramatic influence on Irving—who considers himself a realist, by the way. And actually once I accept Irving’s odd situations, what occurs in them doesn’t harm his spell. His characters, if broadly drawn, act believably, though their inner lives often go missing in action. Irving possesses imagination, so I presume this is an instance of how event sequence seems hostile to lingering, to interiority. Paradoxically this novel of wacky people and situations offers a feast of ideas.While I’m now afraid to reread The World According to Garp, which intoxicated me in my immersion back in June 1978, for fear it will feel similarly ponderous, I do plan to reread A Prayer for Owen Meany. It shares with The Cider House Rules a concern with human goodness in conflict with tyranny. A tyranny driven by extremists who sway or attack the majority. Yet Irving gives abortion opponents their fair due in Cider House‘s pro-choice narrative. Ending any life isn’t trivial, and Irving examines this dilemma from several angles.

A brave book, honest and therefore inescapably political, The Cider House Rules shines with humane truths. And having at last read it, I can use Irving’s metaphor about unfair rules with a clearer conscience.

[Irving explained his literary aesthetic and working method in a fascinating interview with The Paris Review.]

[Tobey Maguire and Charlize Theron frolick on the movie poster.]

The post The power of a metaphor appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

December 3, 2015

Sign me, Bemused

If you wish to read a wide variety of texts (e.g., novels, newspapers, blog entries) and recognize 98 percent of the words in the texts (98 out of 100 words), you’ll have to know around 8,000 to 9,000 word families (or around 35,000 individual words).—from grammarly blog: “How Many Words Should You Know To Read Books and Watch Movies in English?”

I.

[Amused . . . or just drunk as a lord?]

Back in graduate school, I wrote a paper on the misuse of forte. It means a person’s strong suit when pronounced “fort” but refers to a loud musical passage when pronounced as its spelling indicates, for-tey. Or once it did. The distinction has almost been lost partly because people who knew better began mispronouncing forte to fit in.Which I think is what interested me, that cognitive dissonance. Everyone wants to belong, to be admired by her or his chosen group. So I was upset when I realized recently that I’d misused the word “bemused” several times in my book, Shepherd: A Memoir. The memorable one to me involves our ewe Big Mama and her sardonic attitude toward me. I said she was bemused by me.

But bemused does not mean “extra amused”; it means bewildered or confused; a secondary meaning is lost in thought. The word is so rampantly misused that its meaning may be changing. And even when used correctly, its meaning often is unclear.

Here’s Mary Karr, describing her father as her storytelling model, in The Art of Memoir:

He had a talent for physical detail and a bemused attention to the human comedy.

Karr is a best-selling memoirist and a respected poet, so we must assume she’s using the word correctly here. Or must we? I think so. Yet Karr intends praise, and it’s more flattering to her father to picture him as amused by the human comedy than confused by it. Maybe he’s just a bit puzzled like everyone else in this comedy of errors we call life. You can see the lack of clarity flowing from this slippery word.

Here’s an example from Maureen Dodd’s column after Hillary Clinton’s recent grilling before the house committee on Benghazi:

Hillary acted bemused, barely masking her contempt at their condescension. She was no doubt amazed at what an amateur job they were doing at character assassination.

Was she confused or was she amused? This example, which seems to be using bemused to mean derisively amused, epitomizes the problem with this word. So often, the correct or the erroneous usage could apply equally.

From a recent New Yorker article on Justin Bieber:

Bieber’s public, once devoted, or at least bemused, was no longer charmed by his youthful petulance, a quality that can be delightful in small doses but toxic in larger ones (particularly when the perpetrator is both twenty years old and very, very wealthy).

How in the world does anything but the incorrect “amused” meaning for bemused apply here? Were Bieber’s fans once either devoted or confused? Wait, in this case the writer is clearly using it correctly.

It’s the New Yorker, so it’s gotta be correct. Right? Call me a heretic, but I’m calling foul. (Calling fowl would be incorrect, reflecting, um, paltry erudition.)

II.

[Patti Smith in Italy in 2013.]

Writing in the New York Times “After Deadline” blog, Philip B. Corbett broached the bemused issue:As The Times’s stylebook says, in careful, traditional use, “bemused” means “bewildered,” “confused” or even “stupefied.” An extended meaning is “preoccupied, lost in thought.”

But the similarity in sound to “amused” leads many writers to merge the meaning of the two words, using “bemused” to suggest a sort of detached amusement. A few dictionaries have started to accept this as an alternate sense.

Such shifts in meaning based on an initial misunderstanding are common as the language evolves. Sometimes the derived use becomes so widespread and accepted that it’s pedantic and pointless to insist on only the original sense. For instance, not long ago we dropped our stylebook’s longtime admonition against using “careen” — rather than “career” — in the sense of “lurch along wildly at high speed.” The original distinction had eroded so completely that there was little to gain in clinging to it.

But there’s a reason to go slowly on such changes. Preserving the original sense of a word like “bemused” gives the careful writer an additional, precise tool. When its meaning starts to blur or merge with another word’s, the result, at least for a while, is confusion and a loss of variety.

So let’s try to hold the line on “bemused.”

One more example. In her lovely National Book Award-winning memoir Just Kids, Patti Smith uses bemused five times. The first usages, I gave her a pass. She’s a rock poet goddess! And because, with such a perilous word, sometimes you just don’t know how to read the writer’s intent (per Mary Karr, above).

So . . . to the damning sentence. In portraying rockstar Johnny Winter’s manager, a “charismatic entrepreneur” whom she probably charmed at least as much as he charmed her in their encounters in the Chelsea Hotel, where he had installed Winter in a suite while negotiating a recording contract, Smith writes of him:

Dressed in blue velvet and perpetually bemused, he was a bit of Oscar Wilde, a bit of the Cheshire Cat.

Patti, that cat was perpetually amused. She misuses it a final time, late in the book, in a brief scene portraying her friend Robert Mapplethorpe reacting to her sudden success as a performer:

He exhaled a perfect stream of smoke, and spoke in a tone he only used with me—a bemused scolding—admiration without envy, our brother-sister language.

Patti Smith, a poet in every fiber of her being, riffs with words, goes with her and their feeling. This seems at odds with the spirit that sends a craftswoman to the Oxford English Dictionary. As portrayed in Just Kids, Smith’s formal education is scant and her self-education embodied saturation in poetry, music, and art. Deeply personal, her quest rested on actualization, intuition, and folk music in every sense of folk and music.

Honor craft but beware its enshrinement. This has become one of this blog’s themes, explicated in such posts as “Art, craft and the elusive self,” “Craft, self & rolling resistance,” and “Between self and story.”

As writing theorist Peter Elbow says in Writing with Power:

[S]ome people who write fluently and perhaps even clearly—they say just what they mean in adequate, errorless words—are really hopelessly boring to read. There is no resistance in their words; you cannot feel any force being overcome, any orneriness. No surprises. The language is too abjectly obedient. When writing is really good, on the other hand, the words themselves lend some of their energy to the writer. The writer is controlling words he can’t turn his back on without danger of being scratched or bitten.

III.

[Bruce’s wild castoff from Darkness became Smith’s hit.]

How well I remember pleading with a professor that “battened” was indeed the word I wanted, in approximately this sentence:The small building was battened behind tall shrubs.

“Batten” commonly means to thrive, feed glutinously, or fatten—Annie Dillard loves it in the latter usage. So my remonstrance only provoked my teacher’s bemused expression and a slow shaking of his head. But somewhere in the fevered recesses of my twenty-year-old brain, I must’ve been influenced by the nautical definition—as in, “Batten down the hatches, matey!”

Here’s an instance showing how the wooly self and its evocative, emotional associations might clasp hands with dry, seemingly linear craft. Using the dictionary to explore my notion, I might have tried this startling usage:

The small building was fastened behind tall shrubs.

Maybe too odd. But playing off all things oceanic:

Marooned on the edge of campus, the small building seemed fastened there by overgrown shrubs that lapped at its eves.

Not quite there, but promising. Self, meet craft.

People dislike pedants even more than they disdain unruly poets, whose egotism seems transparent and therefore more pardonable. I admit that some of the Beatles and even Dylan’s rhymes grate on me. But there’s something to the notion of going with emotional truth, with feeling over mere correctness. As Marvin Bell wrote in “Three Propositions: Hooey, Dewey, and Loony”:

Graduates of what we call our “educational system” and the academics thereof whose professional standing depends on research into what can only be called, with gross naïvete, the “facts” of literature often make a poor audience for the poetry in poems. They want to find out what a poem means rather than how to follow and experience it. They have been schooled in getting to the gist of things and moving on, so they approach poetry as if it were content covered up by words.

To edge back from the lip of chaos here, the first problem with lambasting diction or grammar errors is that someone always knows more than you do. New York Times readers responding to the column on bemused made grammatical errors in airing their own crotchets. Airing their crotchets? That sounds nasty! And crotchet means “an odd fancy or whimsical notion,” I see. So perhaps they were venting pet-peeves (or maybe loosing bugbears?).

Anyway I’ve got my own new bugaboo to brood upon. Forever, apparently. Bemusing to say the least.

[Below, in 1978 Patti Smith sings her impressionistic hit “Because the Night,” written using the chorus and melody of a song given to her by Bruce Springsteen.]

The post Sign me, Bemused appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

November 27, 2015

Great digestive tidings

[Belle, temporarily at ease.]

Mom’s turkey & mine, an adorable grandchild & a neurotic dog.

If they leave you once, they’ll leave you twice. If they leave you twice, they’ll leave you thrice.—Belle’s lament

[Little Kathy gives thanks.]

Two weeks ago Kathy and I fixed Thanksgiving dinner for our daughter Claire, son-in-law David, and adorable 11-month-old granddaughter, Little Kathy, in Virginia. How is it possible that we got the cutest, sweetest, smartest grandchild on earth!?I actually asked this of the continuing studies students in my memoir-writing class, grossly abusing my teacher’s mantle. Said with a wink, it was, sort of. They laughed, most of them grandparents themselves and getting the joke, even a woman with great-grandchildren.

Over the years, my Mom’s habit of slinging a quick roux of butter and flour over the bird has devolved into my practice. On Mom’s turkeys, little dough blisters erupted here and there on the golden skin. My logic that led to my practice is that roux is a sealant, keeping the meat moist. Thus my rouxing too often and too well. At Claire and David’s, before it was over I’d used 1.5 pounds of butter, with flour as needed, and seasoned with salt, pepper, and sage. I basted every thirty minutes, the crust deepening with each application. Our turkey resembled a crunchy blob. The drippings, plus leftover roux, make killer gravy. Literally. You can feel the arteries in your temples seize.

So baby’s first Thanksgiving was a success.

And as the titular day itself approached earlier this week, text messages flew from the fields of northwestern Ohio and the shores of Lake Tahoe to our residence in suburban Columbus, Ohio. At Tahoe, my sister her husband were hosting our son Tom and one of their nieces. And Tom was in charge of the turkey—and the gravy. Guess whose example he followed? Whose he tried to outdo? Meanwhile, back at the farm where Big Kathy grew up, it was decided that I’d be in charge of the turkey and gravy.

Early Thanksgiving morning we drove two hours west, toward Ohio’s flatlands that once hosted the Great Black Swamp, and gathered at Cissy and Don’s homestead. They cook their turkeys in plastic bags—no fuss, no mess—but tolerated my preparations. In their new oven. Again, I used 1.5 pounds of butter and flour to suit. Recipe alert: that was just it! After the meal, Kathy and I visited brother-in-law Dan’s antique shop. Cissy said while we were gone our dog Belle froze morosely on the couch. In the swirl of so many human bodies, she hadn’t noticed us leave, and soon discovered she’d been abandoned.

[The Virginia bird, warty with roux.]

To Belle, it must’ve looked like It Finally Happened Again. We got her six years ago, at age six, from a shelter. How had no one snapped up this cute dog!? We soon learned of her furtive, neurotic nature. She’d been adopted out twice and brought back, in one case for fighting with a their first dog, and in the second probably because her separation anxiety had been triggered for all time. She spends her hours with us worrying we’re going to leave her, monitoring our every move. And then running and jumping in a forbidden bed to worry when we do leave for work or whatever.At the end of the day, photos of Tom’s heavily-basted bird confirmed that he’d laid it on uber thick. It looked kind of like a coconut cruller donut. Ah, the excesses of youth!

Having cooked two turkeys ourselves, today, Friday, Kathy and I enjoyed our own turkey, stuffing, gravy, peas, and cranberries. Well, we cooked a turkey breast. Which I didn’t roux—we were flat out of butter.

The post Great digestive tidings appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

November 20, 2015

Practice, said the maestro

[Seymour Bernstein and actor Ethan Hawke celebrate Seymour: An Introduction.]

Pianist lauds love of art, human nature’s “spiritual reservoir” in Ethan Hawke’s new documentary on practice & commitment.

The classical pianist Seymour Bernstein says he didn’t feel comfortable on stage for most of his career. Terror and horror swept him, he fought blocks, felt inadequate. He increased his practicing from four hours daily to eight. This “integrated” him as a person and artist. As a result, at last he felt fine on stage, at age 50. He secretly arranged a farewell concert. Held at the 92nd Street YMCA in New York City, his last concert was in 1969. It was hailed as a triumph, and he exited public performance for good. He kept playing, practicing, and teaching. He simply quit the strain of the stage, and poured himself into his students.

This is the paradox and the man, now in his late eighties, explored in actor Ethan Hawke’s new documentary, Seymour: An Introduction. I streamed it on Netflix. In taking the title of a J.D. Salinger novella, Hawke alludes to Salinger’s decision to stop publishing, though Salinger lived on for fifty years as a recluse in a fenced compound. Bernstein has lived quietly but socially for 57 years in the same one-room apartment on the upper west side of Manhattan, sleeping in a hideaway bed. Like Salinger, Bernstein separates the practice of art from its public airing. There’s a lesson here for writers, loathe as most are to view any composition as mere practice or for its own sake. Publication is the thing!

Hawke, suffering a five-year bout of stage fright and a general artistic malaise, met Bernstein at a dinner party and adopted him as a mentor. “I have been struggling recently with finding why it is that I do what I do,” Hawke explains. “I knew that the superficial things—material wealth, the world thinking you are a big-shot—I kind of knew that that was phony. That that was inauthentic to build a career on. But I didn’t know what was authentic.”

His dilemma of why to make art and how to make one’s work authentic is, ultimately, any artist’s. When I began to ask those questions about writing, they continued for years. What justifies this? Is it just ego? No, I decided at last. The desire to practice an art begins in love for that particular art. In Bernstein’s case, at age six he begged his mother for music lessons—in a home where music was never played—and someone gave the family an old upright piano. Early one Sunday morning, he opened his new music book to Schubert’s “Serenade.” His puzzled mother found him weeping. “Oh, it’s the most beautiful piece I ever heard,” he explained. About age 15, he noticed that if practice went well, so did life, but, if not, he felt out of sorts. He explains:

I concluded that the real essence of who we are resides in our talent. In whatever talent there is. Motivated by a love of music and possessed of a clear understanding of the reasons for practicing, you can establish so deep an accord between your musical self and your personal self that eventually music and life will interact in a never-ending cycle of fulfillment.

That didn’t seem to work for him, actually, without extraordinary effort, and he ended his career. But he never quit playing, and cautions against pursuing artistic success—or even a career:

I’m not sure a major career is a healthy thing to embark upon. I see my colleagues with major careers suffer horribly. . . The contrast between the unbelievable attainment of art and the unpredictability of the social world is so great, the contrast is so great, that it makes them [artists] neurotic. They can’t equate this. . . . I [aspire] to be like amateur musicians, namely to do it for love and not just for commercial purposes.

Late in the film, seen strolling down his leafy Manhattan street followed by Hawke’s camera, Bernstein drifts inevitably into the spiritual realm. He honors an internal force—“I call it a spiritual reservoir; I don’t call it God.” Of course, everyone must decide such matters for herself, but defining this inherent force—Carl Jung called it the collective unconscious—seems a basic, ancient, and urgent human task.

“Most people don’t tap that resource of the God within,” Bernstein adds. “What upsets me about religion is the answers always seem apart from us, in the form of a deity. And we depend upon the deity for salvation. But I firmly believe that it’s within us.”

[Below, Seymour Bernstein explains his love for Schubert’s “Serenade.”]

The post Practice, said the maestro appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

November 5, 2015

Space cadets

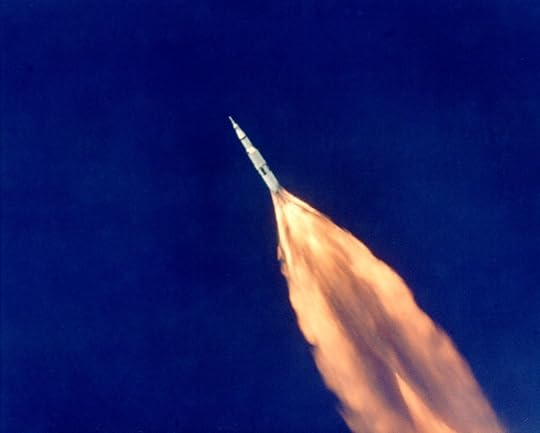

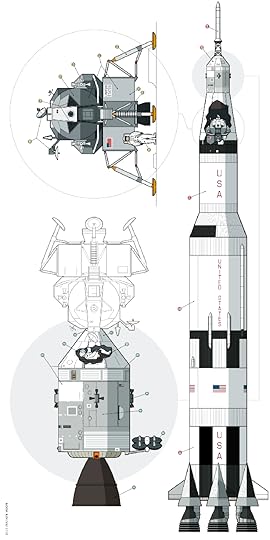

[Into the wild blue yonder: the historic Apollo moonshot, 1969.]

[ Why you won’t read his space book but should.]

Once I met a woman who blurted after I’d given a reading, “Writers . . . They’re known to be egotistical.” She peered into my face. I was speechless. She’s a professor of literature! Plenty of untutored laymen share her impression.I say this while immersed in Of a Fire on the Moon, the account of the Apollo 11 mission to the moon in 1969 by a man who fueled that stereotype, legendary egotist Norman Mailer. Reading it because of another book I’m reviewing, I find Mailer’s stance may imply at first blush I’m smarter and feel more, which gives me the right to be this self-referential. But I can’t help but think as well of the burden of such a claim. To be smarter and more empathetic. You can see, too, that he isn’t just winging it—his language and insights reveal he’s deeply immersed. His idiosyncratic impressions of the astronauts are interesting and, let it be said, funny.

Here’s a snippet of his portrayal of Neil Armstrong at a pre-launch press conference in Houston:

When Armstrong paused and looked for the next phrase he sometimes made a sound like the open crackling of static on a pilot’s voiceband with the control tower. One did not have the impression that the static came from him so much as that he had listened to so much static in his life, suffered so much of it, that his flesh, his cells, like it or not, were impregnated with the very cracklings of static.

And I can’t resist quoting from Mailer’s impressions of Buzz Aldrin (who in 2002 at age 72 went viral on YouTube for punching out a moon-landing denier). Here Aldrin painfully tries to address journalists’ appalling prying about his feelings:

He spoke glumly, probably thinking at this moment neither of his family nor himself—rather whether his ability to anticipate and interpret had been correctly employed in the cathexis-loaded dynamic shift vector area of changed field domestic situations (which translates as: attractive wife and kids playing second fiddle to boss astronaut number two sometimes blow group stack). Aldrin was a man of such powerful potentialities and iron disciplines that the dull weight of appropriately massed jargon was no mean gift to him. He obviously liked it to work. It kept explosives in their package. When his laboriously acquired speech failed to mop up the discharge of a question, he got as glum as a fastidious housewife who cannot keep the shine on her floor.

[Oriana Fallaci: brave, blazing talent.]

In other research for my upcoming review, I perused Oriana Fallaci’s account of the mid-1960s space program in her critically acclaimed but now hard-to-find book, If the Sun Dies. Published in 1967, three years ahead of Mailer’s, Fallaci’s reflects greater access. In what seemed a less intense period, she hung out with and interviewed, astronauts. They clearly liked her. And she scored a sit-down in Alabama with rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, who was the Nazis’ before he was ours. This for me was the high point of If the Sun Dies—Fallaci had been a young resistance fighter in Italy in WWII, and loathed von Braun; she intercut their interview with her memories of occupying German soldiers. Her later work obscures this one’s brilliance. Fallacii (1929–2006) was a brave, blazing talent.Mailer had to content himself with attending a press conference with von Braun and later his speech at a Titusville, Florida, country club. Mailer cast lots of shade von Braun’s way, per the wizard’s massive Teutonic chin, small voice, and past affiliation. But Mailer’s animus really stems from his romantic sensibility threatened by and hostile toward technology and technicians. Rocketry: merely emblematic. Technology is why you won’t read Of a Fire on the Moon and why you should. Through the moon mission, Mailer attempts a national portrait.

As a college student, I lost myself in his account of participating in the 1967 antiwar march on the Pentagon, The Armies of the Night, which won a Pulitzer. “Creative nonfiction” didn’t yet exist, and New Journalism was a rumor, but it showed me how a writer could use the self to transcend the self. It showed me personal writing’s power and importance in helping readers understand phenomena by filtering them through an individual’s sensibility. I was amazed again in 1980 by Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song, about Gary Gilmore’s life, crimes, and execution. Using Lawrence Schiller’s exhaustive research and interviews, Mailer spun stringently impersonal prose for this “novel,” for which he won his second Pulitzer. If Mailer’s fiction seemed lesser than his contemporaries’ to me, his reality-based narratives were something else. As Charles McGrath wrote in his obituary for the New York Times:

Along the way, he transformed American journalism by introducing to nonfiction writing some of the techniques of the novelist and by placing at the center of his reporting a brilliant, flawed and larger-than-life character who was none other than Norman Mailer himself.

Mailer’s writing in 1970’s Of a Fire on the Moon makes me think it held lessons for Tom Wolfe, who came along with The Right Stuff almost a decade later, in 1979. Maybe it’s just Mailer’s freely used exclamation points. But unlike Wolfe, who wrote his entertaining account in a distanced third person, Mailer, writing of himself in third person, at least doesn’t make everyone bray like jackasses. Wolfe beat the hell out of becoming privy to test pilot’s secret macho code, whereas Mailer—give the devil his due—angled for gravity. He had briefly studied aeronautical engineering when at Harvard, a piquant fact given his avowed anxiety about all that spaceflight represents.

Mailer’s writing ability is so fearsome, reminiscent of David Foster Wallace’s, that you stop questioning the accuracy of his perceptions—what would that mean? subjectivity’s the point— and instead marvel at their nature and quantity. As when he observes Armstrong give a successful TV interview and muses on “that intolerable mixture of bland agreeability and dissolved salt which characterized all performers who appeared in public each day for years and prospered.”

Say what?

Then again, ponder for yourself dissolved salt. Mailer fields startling metaphors. Through it all, our perceptive stand-in strains to master a quintessentially human striving and to convey it. I had written off Mailer because of his behavior, but my project that sent me to his work again showed me how impressive he could be as a writer. Trying in Of a Fire on the Moon to grasp and pull together everything makes his work feel exciting and risky. Traveling the “unmapped continent of America’s undetermined heart,” he conjures America’s intractable demons and its impossible ideals.

[In 2014, on the eve of the 45th anniversary of the moon expedition, Geoff Dyer wrote about Mailer’s book in the Guardian as an exemplar of New Journalism.]

[Below: Apollo 11 atop the humongous Saturn V rocket.]

The post Space cadets appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

October 28, 2015

Why write?!

1.

I start with nothing, except of course, everything I’ve read, seen and felt. It takes me a tortured while to write what I know. It’s a battle to trust what’s right there in front of me. Language feels inadequate to the skepticism that skips about in my head. . . . How do I cut through to the other side where expression is also something I own? The simple answer is, I read. I return to the world and do the thing I love to do: listen. For me, reading is listening. It’s the act of turning to another life or idea.—Claudia Rankine

[Claudia Rankine. Photo by John Lucas.]

There you have it. Writing as discovery, listening, love, and gift-giving over discipline and suffering. Mary Karr’s concise comment likening writing to hardship—fun only for neophytes and hacks—in The Art of Memoir (reviewed), has served as a magnet to attract to me emendations and counter-arguments. Like poet Claudia Rankine’s. In her recent essay for the Washington Post she admits to struggle. But the point of writing for Rankine seems to be its rewards, including sending her to read books.There’s loving reading. There’s liking making sentences. There’s the discovery and attempted perfection of your truth. Isaac Asimov supposedly said, “Writing, to me, is simply thinking through my fingers.” Yes, writing is concentrated thought, which makes it hard, though saying it that way that misses the emotional component that Rankine alludes to. I too pull books from the shelves—just to see how a brilliant book is made of many great and ordinary sentences. In moments of doubt, I revisit old friends, like the late Donald M. Murray, who nails writing’s rewards in The Craft of Revision:

Writing is not reported thought. Writing is more important than that. It is thinking itself. . . . And it is fun because I keep finding I know more than I expected, feel more than I expected, remember more, and have a stronger opinion than I expected.

11.

In maybe the best short video on writing ever, Ta-Nehisi Coates discusses “practicing,” getting stressed by going for greatness, being courageous in continuing, and breaking through to become better than he’d dared hope.

The desire or need to make anything, such as a successful car wash, must overcome, at some point, resistance. The activity cannot be fueled by mere egotism. I think the hardness of writing disciplines the ego. The why to do something so hard for an audience becomes paradoxically using the self to transcend the self.

Two fine books about writing, Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird and Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life, emphasize its struggle. In my memory, Lamott focuses on the difficulty of filling blank pages. Dillard focuses on the gap between the stubborn words and the writer’s soaring aims. She addresses the Then why do it aspect obliquely yet thoroughly. For Dillard, writing is about making oneself more than the mere self. It’s about becoming an inspired vessel of truth. That’s why.

So passion, not pathology, best fuels the enterprise. I like the notion of any worthy, consuming work being based on love, rather than discipline. Here’s Dillard’s famous view in her essay “To Fashion a Text,” collected by the late William Zinsser in Inventing the Truth:

Writing a book is like rearing children—willpower has very little to do with it. If you have a little baby crying in the middle of the night, and if you depend only on willpower to get you out of bed to feed the baby, that baby will starve. You do it out of love. Willpower is a weak idea; love is strong. You don’t have to scourge yourself with the cat-o’-nine-tails to go to the baby. You go to the baby out of love for that particular baby. That’s the same way you go to your desk. There’s nothing freakish about it. Caring passionately about something isn’t against nature, and it isn’t against human nature. It’s what we’re here to do.

Literature’s demands and ideals militate against mere egotism. Writers speak for and to the mute Other and the muted populace. If those imperatives seem passé in the age of social media, print culture won’t let them pass. Reading and writing epitomize interpersonal connection and personal transcendence.

111.

Pharrell Williams’s hit “Happy” embodies Joseph Campbell’s truth:

If you can do something that you love to do without fear of criticism, you will move. You will find joy in it. You do not have to move more than an inch to feel the joy.

These days I watch my granddaughter, crawling everywhere and pulling up on everything, busy as all get-out at ten months. It’s play and work, a constant output of effort to explore and master her world. After so many hours, she rubs her eyes, crashes and cries.

She’s right back at it after a nice nap. As I hold her and look into her brown eyes, I think, Oh, the places you’ll go . . .

[David Knight with Kathy Knight-Gilbert in the pumpkin patch. Why did I get the sweetest, smartest, cutest grandchild on Earth?]

The post Why write?! appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

October 21, 2015

Ode to joy

[Don Draper: happy at last.]

The dark Mad Men ends: narrative drive, musical bliss & a smile.

I’d like to build the world a home

and furnish it with love,

grow apple trees and honey bees

and snow-white turtle doves.

I’d like to teach the world to sing

in perfect harmony.

I’d like to hold it in my arms

and keep it company.

—“I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing,” which originated as a jingle, “Buy the World a Coke,” for Coke’s iconic “Hilltop” commercial.

For Meg. (Spoiler alerts!)

Mad Men captured the excesses and brio of the late 1959s, the 1960s, and the early 1970s. As I explained in 2012 when I drifted away, its fitting climax seemed to be when its main characters formed their own Madison Avenue advertising agency. That’s when a respectable novel would’ve ended. But I drifted back, partly because Don Draper and his times reminded me of my father. Now I’ve watched the rest, and binged on the seventh and final season. I found the show’s last year riveting—especially once the principal players of Sterling Cooper Partners were absorbed by the mother ship, sent to McCann Erickson, which had since bought a majority interest in the scrappy underdog.

Even by the sexist standards of the time, McCann Erickson is a dreadful place for the women, and controlling and soulless for everyone. But the Sterling Cooper partners will become millionaires if they can hang on for four years and fulfill the basic terms of their contract. Can they? One by one, the answer is, basically, no. As they choose their fates, I was reminded of the famous ending of Six Feet Under, which flashed forward to the characters’ deaths. For these Madison Avenue men and women, however, they get another chance. How satisfying to see Pete Campbell, head of accounts, who’d been humbled by his own meanness, insecurity, and egotism reconcile with his wife and fly off to a spiffy new career with Lear Jet. Instantly I remembered him at his worst, when he tried to destroy Don by revealing Don’s tawdry past and assumed identity. This in turn emphasized how the two later became allies and even friends in the show’s long arc.

As Sterling Cooper’s brilliant creative director, Don is McCann Erickson’s big prize and great hope. He’s been handed their Coke account! At first he plays along, but then takes a road trip and disappears. Is this one of his periodic battery-recharging hegiras or is he finally self-destructing for good? Wandering America, he’s stranded by car trouble and beaten by members of a backwater VFW post who’d tried to make him their improbable buddy; he ends up test-driving racecars on the Utah salt flats with a much younger, hairier crew. This all sounds ridiculous as I write it, but was somewhat believable in context. Don was both haunted and uber cool and competent. Of course he ends up, as always, in California. This time he lands in the bosom of its burgeoning early 1970s self-actualizing culture. He seems deeply depressed, maybe shattered, teetering on the brink.

The two following scenes floored me. There’s Don in a lotus pose atop a surf-smashed cliff, and then Coke’s all-time iconic commercial, 1971’s “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke.” As the implication of cutting from Don suddenly smiling to the Coke commercial dawned on me, I felt delight in creator Matthew Weiner’s deft storytelling. Don was first and foremost an ad man, not a tortured filmmaker or writer or hardware shop proprietor. It was perfection that he’d return and forge his life experiences, emotional restoration, and instinct for the zeitgeist into a legendary TV commercial. He survived after all, thank goodness. And boy did he prosper.

The ending underscored that Mad Men was always about growth—and burning your baggage for fuel if necessary. How fitting it came to rest on redemption.

[Coke’s famous 1971 “hilltop” commercial that “Don wrote.”]

The post Ode to joy appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

October 14, 2015

Structure & style

Published writers always say revision is the sin qua non of effective prose. Dinty W. Moore just affirmed it in here my interview with him—he claims to produce weak first drafts, which become strong as they undergo up to 50 revisions. In her new The Art of Memoir, just reviewed, Mary Karr says one of her poems might take 60 versions. “I am not much of a writer,” she says, “but I am a stubborn little bulldog of a reviser.”

I used to think I was a great reviser myself. Probably because I edit and polish as I go, and then polish some more. Recently I’ve seen that two factors that impair my revising also seem to afflict some other writers.

The first issue involves resistance to complete structural overhauls. I saw this in my book. I put it through six versions, which embodied two excellent, hired developmental edits; one free problematic one; a paid whole-book copy edit; and countless piecemeal edits from friends and fellow writers. After all that, I resisted—because I feared—the mere idea of soliciting one more opinion. I was scared that someone would show me clearly that I needed a whole new approach that would send me back to the blank screen.

[Cheryl Strayed’s Wild taught me structure.]

I’ve seen this resistance in other writers, and it’s a problem if the writer has stopped too soon—no matter how many years s/he’s labored. Ironically, and thankfully, while reading Cheryl Strayed’s Wild at the eleventh hour, I saw a key structural move I needed. And a new template for my prologue. I’ve written about this breakthrough, which I saw only because of years of work, including the advice I had been receptive to. After learning how to use backstory from Strayed, and writing a new prologue that like hers showcases a dramatic moment, I knew my book was ready.It gives me chills to recall that an editor had actually suggested, at the very start of my writing, the restructuring I took from Wild—but I’d forgotten his advice. At the time, I didn’t understand why it would be better to scatter memories of my father throughout the book, rather than corral him in one chapter. Strayed’s artful deployment of her own backstory turned on the light.

Using a prose revision process: Richard Lanham’s method

Recently it was painful to follow advice and strip an entire thread from a long essay (discussed) I drafted over the summer. My test readers said it didn’t work within the overall story. At first, I tried to ignore them. I’d had such hopes for it, and it was so much work to write.

The essay flows from my finding an old cane; its contested element concerned my wife’s recuperation from foot surgery—why I found the cane in the first place. “But she really grounds the essay,” I protested. Inwardly I agreed that I hadn’t managed to link the tale of her foot to the essay’s larger themes. When one reader pointed out my essay’s true organizing principle, it helped me push off stage my sore-footed wife—she was thrilled to be cut—and to shine the spotlight elsewhere.

Then an awful, humbling problem materialized. “The essay is flat,” said my friend Beth. The recovery thread had been scenic and lively, which obscured that my syntax in the main threads got turgid. I was trying hard to be reflective—too hard. Too many prepositions, too much passivity, to many “is” and “was”—the old “to be” issue—and lots of clauses. These are galling first-draft problems. An example of the “is problem”:

It was rewarding vs. It felt rewarding.

The first is a godlike but bland statement of “fact” that obscures the person doing the feeling and loses subjectivity’s honest idiosyncratic appeal. Focused on whipping up a new dish, I had dropped a trusty old casserole dish on my toe.

Beth is a scholar, and her essays on writers are clear and graceful. “What I do,” she said, “is follow Richard Lanham’s steps in Revising Prose. I circle the prepositions, rework some ‘is’ forms, make everything active. I look for dangling modifiers because that’s a problem for me.” I knew of Lanham but hadn’t thought I needed him. Or, rather, hadn’t thought I needed any systematic process—because “I rewrite.”

I looked up Lanham’s new, fifth edition of Revising Prose on Amazon found a stunning textbook price: $50 for its 176 pages. Instead, I ordered the $5.50 fourth edition. There’s a fine review of the new edition, by C. J. Singh, of Berkeley, California, which explains Lanham’s core principles.

An excerpt of Singh’s review:

In each of the five editions of “Revising Prose,” Lanham added fresh examples and exercises to its core content: the Paramedic Method comprising eight steps as follows.

1. Circle the prepositions;

2. Circle the “is” forms;

3. Find the action;

4. Put this action in a simple (not compound) active verb;

5. Start fast – no slow windups;

6. Read the passage aloud with emphasis and feeling;

7. Write out each sentence on a blank screen or sheet of paper and mark off its basic rhythmic units with a “/”;

8. Mark off sentence length with a “/.”

Basically, Lanham’s Paramedic Method advises you to delete prepositional phrases and “is” forms and replace them with active verbs.

To foster diversity in my diction and to avoid misusing words, recently I adopted John McPhee’s practice of drawing boxes around distinctive or mundane nouns, verbs, adjectives in his final draft. Then you look up the words, consider alternatives. Now I’m going to try Lanham’s process.

For years, my most effective revision standby has been reading my last draft aloud. Maybe it’s my trying new writing approaches—thus experiencing the dreaded learning-curve effect—or maybe it’s just my age, but it appears I need to add to my revision toolkit.

What methods are effective for you in revision?

The post Structure & style appeared first on Richard Gilbert.