Richard Gilbert's Blog, page 4

August 10, 2016

A dying writer’s memoir

Write as if you were dying. At the same time, assume you write for an audience consisting solely of terminal patients. That is, after all, the case. What would you begin writing if you knew you would die soon? What could you say to a dying person that would not enrage by its triviality?— Annie Dillard, The Writing Life (reviewed)

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi. Random House, 228 pp.

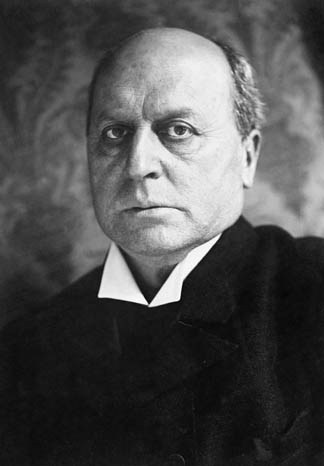

Paul Kalanithi had his life mapped out: 20 years of medical practice followed by 20 years of writing. Amidst that span, marriage and children, vacations and celebrations—plenty of time to repair the strains in his marriage caused by his tenacious pursuit of medical excellence. Found riddled with cancer late in his surgical residency, already a gifted neurosurgeon at age 36, he soldiered on for a time. While terminal himself, he operated on others.

Finally lacking the endurance for surgery, he concentrated on writing When Breath Becomes Air. In just under two years left to him, he wrote about his cancer treatments, about medicine as a high calling, about his past and ongoing life. He also became a father, nine months before he died, at age 37.

His cancer responded well to initial treatment, but returned. He explains his reaction to seeing those scans, which told him his end was coming fast:

I was neither angry nor scared. It simply was. It was a fact about the world, like the distance from the sun to the earth. I drove home and told Lucy.

His widow, Dr. Lucy Kalanithi, who wrote his book’s epilogue, elaborated for an interviewer (video below) about their complex reaction:

We’d seen it happen to so many people and witnessed and helped people through it. The reaction wasn’t so much “Why me?” We sort of felt, “Now it’s our turn to face this.” The best and worst part was that knowledge.

Few have been more prepared than Kalanithi to make sense of mortality. Growing up in Arizona, the son of a cardiologist, he’d planned to be a writer partly because of how hard his father worked. The price of medicine seemed too high. His mother, trying to overcome poor local schools, inadvertently kindled his literary ambitions when she found a college prep reading list. She made him read George Orwell’s novel 1984 at age ten. At Stanford University, he earned undergraduate and master’s degrees in English, along with an undergraduate degree in human biology. Afterward, at the University of Cambridge, he added a master’s in the history and philosophy of science and medicine. He then attended medical school at Yale—and picked perhaps the most demanding medical specialty, neurosurgery, returning to Stanford for his residency and a postdoctoral fellowship in neuroscience. He’d work as a surgeon and professor.

Weaving stories of surgeries he performed or treatments he witnessed with his own experiences as a patient, Kalinithi reveals himself not only as intelligent but as deeply empathetic to patients. Like the rest of us, as a patient himself he had fine doctors and fair—and one awful resident who almost killed him, it seemed as much from ego and lack of empathy as from inadequate experience. When Breath Becomes Air might be assigned in medical schools to address what seems a vexing nub: always building technical expertise while blending that skill with one’s humanity. He writes:

Doctors in highly charged fields met patients at inflected moments, the most authentic moments, where life and identity were under threat; their duty included learning what made that particular patient’s life worth living, and planning to save those things if possible—or to allow the peace of death if not. Such power required deep responsibility, sharing in guilt and recrimination. . . . The secret is to know that the deck is stacked, that you will lose, that your hands or judgment will slip, and yet still struggle to win for your patients.

One of his medical school friends killed himself after losing a patient in surgery. In a case Kalinithi witnesses, an adorable eight-year-old boy with a brain tumor is saved, only to return at age twelve, a violent monster—his hypothalamus had been slightly injured in the procedure. Few surgeons could have succeeded: one millimeter had made the difference between his living a normal existence and having to be institutionalized.

[Lucy, Paul, and Cady Kalanithi]

And what of Kalanithi himself? He wrote this book, every word and line, facing death. Trained to fight death, he fought, but paradoxically at the same time had to accept. He’s like a jet pilot who has lost his engines and is trying to glide for as long as he can, while trying to avoid causing harm below in his inevitable crash, while seeing for the last time life’s ordinary and extraordinary beauty. A lesser writer might have exhorted his readers, but Kalanithi focuses on his experience and on rendering it precisely. This is the gift. The person, the writer, who can do this is exhortation enough.But as well as portraying, he reflects, as he clearly did in life, and possesses the means to do so. He’d already moved from a long sojourn in “ironclad atheism” to an awareness that science cannot explain the central aspects of human life: “hope, fear, love, hate, beauty, envy, honor, weakness, striving, suffering, virtue.” These emotions and emotional qualities are encoded, of course, in religion, which seeks to ascertain human truths. Today’s militant atheists seem speciously drawn to the obvious absence of a physical God, without awareness that the Bible itself documents an evolution in understanding and encouraging what’s holy within humans. As Kalanithi tries to explain:

Yet I returned to the central values of Christianity—sacrifice, redemption, forgiveness—because I found them so compelling. There is a tension in the Bible between justice and mercy, between the Old Testament and the New Testament. And the New Testament says you can never be good enough: goodness is the thing, and you can never live up to it. The main message of Jesus, I believed, is that mercy trumps justice every time.

One is tempted to lament the body of work—the saved lives, the brilliant articles, the profound books—Kalanithi would’ve produced. And he himself reflects on this. But here it is. Here is what he got, and what he was able to give us. A distillate. Here is profundity with a light touch, philosophical gravity lightened by living breath, prose of spare beauty.

This exquisite book centers you. Likewise its lesson for writers is quite simple and quite sobering: be as funny as you can, be as experimental as you desire, be as traditional as you wish, but never be trivial.

You that seek what life is in death,

Now find it air that once was breath.

New names unknown, old names gone:

Till time end bodies, but souls none.

Reader! then make time, while you be,

But steps to your eternity.

—”Caelica 83″ by Baron Brooke Fulke Greville (1614–1621)

[An excellent excerpt, with photos, video, and voice recording is Paul Kalanithi’s Spring 2015 essay in Stanford Medicine “Before I Go.” Other essays are linked off his web site, url above.]

The post A dying writer’s memoir appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

August 3, 2016

The common touch

. . . the old verities and truths of the heart, the old universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed . . . —William Faulkner’s Nobel Prize banquet speech

Late One Night by Lee Martin. Dzanc Books, 313 pp.

Ronnie Black is a real hothead—everyone knows it—and he’s unfaithful. When his estranged wife and three of her seven children die one night in a fire that engulfs their trailer home, suspicions point to Ronnie. The fire and a subsequent custody battle roil the small rural town, especially when the cause of the fire is ruled to be arson. Lee Martin’s new novel shines a light on human failings, such as gossip and lack of compassion, as well as on quiet daily heroism and the way mistakes and coincidences can combine to produce tragedy.

Reading Late One Night, I was struck by Martin’s compassion for his characters. Especially for those who, despite themselves, end up doing wrong. Having read his nonfiction, including his fine memoirs From Our House (reviewed) and Such a Life (reviewed) and his helpful ongoing craft blog, “The Least You Need to Know,” it’s clear he’s one of them. One of those farm and working folk from the hinterlands, from America’s faded provincial towns and threadbare rural backwaters.

One of them, that is, who left. Who took a different path, got out. Who got himself tons of education and made himself a writer, who turned himself into an artist. Whose subject, here, is so much them, those he left behind—yet hasn’t. The effect of Martin’s steady compassion grows throughout Late One Night until, as mysteries are revealed—as the true story of the fatal fire is finally told—the novel becomes deeply, surprisingly moving.

Maybe it’s that his characters, in turn, finally express compassion for each other. That rings true or at least possible. These are broken people, many of them, or guiltily carrying burdens, and their effort to forgive others in the face of their own failures feels heroic. A murder mystery on the surface, Late One Night is really about forgiveness and the flickering hope of redemption.

Martin’s feeling for ordinary people and the ones among them who go disastrously astray comes from deep inside the writer, I believe. But one can see in his technical choices how he expressed it, how he tried to make his readers feel it. Late One Night is written in close third-person that gives us omniscient access into someone’s inner thoughts and feelings—but he alternates this with a communal voice and point of view. For instance:

No one said a word. Everyone was sitting at the cafeteria tables, where only moments before they’d been talking about crop prices, and Lord couldn’t we use some rain, and hell yes it was hot. Too hot for September. That was damn sure. . . . He’d left her stranded in Goldengate one night when they got in a snort and a holler because she wanted to buy a doll baby for their littlest girl and he said there wasn’t money enough for something like that.

This has such an interesting effect, making the omniscient narrator, for one thing, possibly an outsider channeling a local, a local himself, or a chorus of locals. Of course this supports the private conversations and inner heartaches Martin makes us privy to. A character sums it up, speaking in utter simplicity to her lover late in the book:

What I’ve decided is maybe we’re all that close to doing things we’d regret. The right chain of circumstances, and there we are.

Her mate answers her in a reply to the entire town:

We need to help one another. We need to forgive. That’s what I aim to do. In my heart of hearts, I hope you’ll do the same.

Old truths, it’s true. But as the novel ends, with a snowfall reminiscent of James Joyce’s that famously closes his short story “The Dead,” Martin makes them live. Set within tragic circumstances, among ordinary lives that have become real to us, Late One Night makes the old verities new and touching.

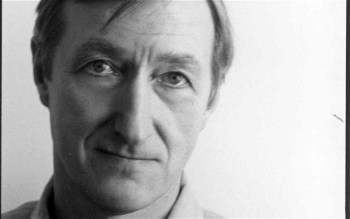

Lee Martin answered some questions by email.

[Martin: “working my way toward knowing.”]

Q. You’ve said the incident that led to Late One night was a disastrous rural trailer fire you read about. I understand you sometimes conduct research for your novels, and wonder how much research you did for this one beyond that initial newspaper account?

I went to the site of the fire and looked at the ruins. I cataloged the small details, the ones like a child’s purple glove with a silver star on it. Those concrete details suggested lives to me and led me inside the characters I invented. Those details invited me to imagine those characters’ stories.

Q. Why did that incident resonate for you? Put another way, how did it resonate as a possible novel? Is such an impulse or hunch different from the feeling that tells you something’s an essay?

I took the fact from the news and started playing the “what if?” game. What if the husband were living outside the home at the time of the fire? What if the fire turned out to be the result of arson? What if small-town gossip began to cast suspicion on that husband? What if it wasn’t exactly clear if he was guilty? And where did guilt begin and end? And what about responsibility? Responsibility to family, to love, to everyone around us?

In that way, the impulse to write a novel is similar for me to the one that leads me to an essay. Both begin with questions. Both begin with what I don’t know. Each becomes a way of working my way toward knowing, or else to a deepening of the questions, or perhaps a different set of questions. The difference is that with a novel I immediately see a dramatic frame upon which to hang a story. With an essay, I want to see what I think about something. There is no frame, and perhaps no story, as I begin to write, although one may emerge during the process.

Q. Late One Night is a murder mystery, yet not a typical one, based as it is on a relatively small incident in a rural backwater and set among blue-collar people. I’m struck by your steady focus on this fatal arson and how it affected those whose lives are seldom chronicled. Was any writerly redress at work? What reaction have you gotten from such places, including from folks in your home region of southern Illinois?

I want my work to come from the people and the places I know best, and that happens to be the blue-collar world of the rural Midwest. The people there are often overlooked in our contemporary culture. I want to tell their stories, and I want to honor their complexity and their dignity. Their lives are splendid and rich because they’re human, and if I can give a voice to them that people will listen to, then I’m glad. I bristle when readers dismiss characters because of their economic status, or because they think they make poor decisions. This is snobbery of the worst order. We all make poor decisions. We stumble along the way, and we do our best to regain our footing.

Ronnie Black, in Late One Night makes a decision he’ll regret the rest of his life, but does that mean he’s incapable of love? Does it mean he doesn’t know what it is to protect his family? Does it mean we should stand in judgment of him? I do my best to understand the sources of my characters’ behaviors, and those behaviors are often tied to what it is to live a particular life in a particular place. My place, as I’ve said, is the rural Midwest. I hear from a number of folks there who enjoy my books. At the same time, I’m aware that I’ve stepped outside the custom of that culture to not speak of one’s troubles and secrets.

Q. I’m familiar with your use and skill at the communal point of view from some of your essays where you do the same thing. I’m interested which came first—is this something fictional practice has brought to your nonfiction, or vice versa? What is your aim in using it?

That’s a great question, Richard. I’m not really sure, but I think I may have tried expressing a communal voice first in nonfiction. I’m thinking of my essay published by Brevity, “Dumber Than.” Then, of course, I used it in my novel, The Bright Forever.

When I use it, my aim is to give a voice to the community within which my main characters have their own voices. We’re always acting in accordance with a community or in resistance to it. I like to find the communal voice that represents the cultural norms of the place to give a texture to the voices of my characters.

Q. Some of your novel’s chapters are very short, about three pages, while others are longer. This variation was striking in some cases. I wonder how you worked out chapter length?

I often think a chapter should focus on a single dramatic event or a major shift in the character relationships. Sometimes it takes a number of pages to fully dramatize something, but sometimes I like to do a quick cut, the sound of which I hope will resonate in contrast to a longer chapter. Resonance can come from a variety of sources in a novel, but one of them is the sound the book makes from the length and arrangement of its chapters.

Q. I’ve written a lot here about writing’s exciting and rewarding aspects. But writing has a heartbreaking side, as when you work for months or even years on something and conclude—or are persuaded—that it doesn’t work. How do you deal with or think about such setbacks or discouragement?

I try to choose my material wisely. I want to be so excited about the work ahead of me that I can’t help but succeed. I rarely give up on a project, but the few times that I have, I’ve been able to let it go because the next exciting thing is calling to me. I’m still convinced that, should the time come, I’d be able to go back to those abandoned projects and make them work.

[Martin guest lectures, Otterbein University.]

Q. You must have known talented writers over the years who have quit, maybe while you were a student or among your own students. Why do you think some are able to continue writing, even in the face of steady rejection? Maybe this is a personal question, as I believe you’ve said it took you a long time before things clicked for you.

When I was a student, there were others who were much more talented than I, but for whatever reasons they stopped. I’ve had my own students who should have gone on to stellar careers, but they stopped writing. It wouldn’t be fair of me to speculate on what it is that keeps some of us going while others surrender, though I suspect it has something to do with being extremely driven and with using disappointment for motivation and for a certain thickening of the skin that this writing business demands of us.

Q. You publish both fiction and creative nonfiction, and teach both. Are there key differences in the genres writers must learn or distinctive leaps they must make? For instance, fiction’s “what if” quality seems to take a different mindset than is associated with nonfiction. By the same token, the emphasis on and creation of a reflective writer’s persona in nonfiction seems different than fiction’s omniscience or its creation of a first-person narrator.

I do think there’s one major difference for those who write fiction and for those who write nonfiction. Usually the fiction writer who’s uncomfortable with nonfiction is the writer who can’t bear to put him or herself on the page. That writer can do amazing things with story and character, but that thinking, meaning-making voice doesn’t come naturally to him or her. The persona of the reflective writer is only comfortable in the guise of a first-person narrator in a piece of fiction—a person who doesn’t announce how similar or dissimilar he or she is from the writer.

[See also my post “Lee Martin: the artist must risk failure.” ]

The post The common touch appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

July 27, 2016

Writer, know thy own demon

[Full of chipper wisdom here, E.B. White was laid low by allergies, like me.]

On illness, hard emotions, and giving readers a high vibration.

Illness is the night-side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.

—Susan Sontag, “Illness as Metaphor”

Writing takes energy. The hot weather system lying across America has sapped mine. Or maybe it’s allergies—an early ragweed bloom. Like an old timer of yore, I find my body casts its own vote via joints and sinuses. My former doctor, a great technician, used to scoff about complaints regarding intangibles like atmospheric pressure—he’d actually laugh in my face—but I knew what I felt. Writing this post took two medicinal pots of coffee.

When my book appeared two years ago, my blog took a hit—all circuits were busy. Maybe that’s just focus—but focus is, or bespeaks, a form of energy. The other thing I know for sure is a writer embeds energy in prose or poetry. I’ve always said readers go to writing to experience another’s emotional reality, but if they don’t find energy there, they leave. You can feel it, the energy in words and sentences.

Major illness is one thing, but how annoying when something like pollen pulls your plug. E.B. White wrote about the debilitating effect of allergies. The malaise they cause. Periodically, and when ragweed blooms in late summer, sometimes I exist in a stupor, dosing myself with Claratin, Alka-Seltzer, chocolate, caffeine.

However bad I feel, I’m always grateful when I realize the cause is physical. Because lack of energy mimics depression. The body is literally depressed, when flooded with histamines. So that’s the feeling the mind experiences. Regardless of cause, it’s hard enough to exist in peace, let alone to run a startup donut chain or write a novel when you lack physical or psychic energy. Dorothea Brande’s classic Becoming a Writer (on this blog here: lengthy discussion and short review and in a post on persona) is really about how to nurture and manage yourself as a person and writer so you can steadily work.

Of course, Brande’s advice concerns not illness but mental or emotional blockages. In that realm, what roils my moods is fear. Where it comes from, I don’t know. But when the writing is especially hard and discouraging, I’ve learned to suspect that old foe. Naming my own demon, having that self-knowledge, brings me some comfort. And accepting what’s arisen also lessens the pain. Not that the cause goes away or the symptoms end—ultimately we each walk a lonesome valley.

Once I visited an elderly man who was declining, in his last stage of life, and he was suffering—not from pain, but from loneliness and fear of death. I didn’t feel qualified to give him advice! How could I possibly help him? I felt so helpless and useless. Yet here was a man in such need. Finally in desperation I drew on this principle of acceptance, learned from Buddhism, though I suppose it’s intrinsic to any religion or inherent to prayer. I said:

“This helps me. When I’m hurting and can’t seem to end it, I say, ‘I accept this suffering.’ It doesn’t mean I don’t try to end it, or that I like it. But accepting the feeling seems to lessen its power. It seems that some of my pain comes from trying to avoid and deny and suppress the painful feeling I already have and don’t want.”

“Thanks,” he said. “I’ll try that.”

I’m not sure how acceptance worked for him; he had memory issues and didn’t share the next time I saw him. He wasn’t desperate, at least, in that subsequent moment. Acceptance seems to work better, for me, for emotional pain than for illness. I can hardly remember to think, let alone bring myself to say,” I accept this lassitude; please pass the Benadryl.”

Amidst my second week on the ropes, I’m grateful for a recent fruitful spell. I’m hoping for a good rain. One of these days, I’ll be able to write what’s now calling to me. Next I’ll stagger to my bookshelves, having abandoned what I’ve been reading, and cast about. I’ll look for something that makes me feel like writing. Something spare or snappy. Something tender and true. Something that emits energy.

All of these lines across my face

Tell you the story of who I am

So many stories of where I’ve been

And how I got to where I am

—Brandi Carlile, “The Story”

The post Writer, know thy own demon appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

July 20, 2016

Two titans of prose

[Lincoln and Darwin: “They matter because they wrote so well.”]

Adam Gropnik sees Abraham Lincoln & Charles Darwin as writers.

Angels and Ages: A Short Book about Darwin, Lincoln, and Modern Life by Adam Gropnik. Vintage, 235 pp.

Abraham Lincoln and Charles Darwin, born on the same day in 1809, changed the world with their actions and their ideas. That they continue to influence our lives and perspectives today proves their historic and even evolutionary importance. And it actually all rests on their writing ability, argues Adam Gropnik: “They matter because they wrote so well.”

In Angels and Ages, an engrossing history and analysis of Lincoln and Darwin as writers, Gropnik calls Darwin’s On the Origin of Species “a long argument meant for amateur readers.” But the book is “so well written,” he adds, “that we don’t think of it as well written, just as Lincoln’s speeches are so well made that they seem to us as natural as pebbles on a beach.”

Both loners, Lincoln and Darwin cut through the cant of their day with original thought expressed in compelling sentences. This impels Gropnik to define strong prose, maybe nailing its definition, at least for idea-driven nonfiction:

Writing well isn’t just a question of winsome expression, but of having found something big and true to say and having found the right words to say it in, of having seen something large and having found the right words to say it small, small enough to enter an individual mind so that the strong ideas of what the words are saying sound like sweet reason.

We also get to know Lincoln and Darwin as men whose identities seem inseparable from their efforts to communicate. The shrewd Lincoln, who had a “tragic sense of responsibility,” was an unbeliever who evolved during the Civil War toward an “agonized intuitive spirituality.” The hypersensitive Darwin possessed a “calm domestic stoicism,” his own private code, but worried about the effect of his ideas on the faithful—especially on his beloved wife, who was grieving their loss of their daughter.

Lincoln served as an avenging angel who loosed a bloody sword, but his puzzled spirituality in response seems a distilled expression of our species’ very essence—as does the transcendent goal of his tragic bloodletting, justice for all, black and white alike. Darwin also is emblematic, an avatar of our species’ restless spirit to know itself. Darwin’s genius cracked the foundation of the church, as he feared it would. Yet his insights did not destroy religion, broadly defined. He actually deepened religion’s animating mystery, human nature: what is it? where did it come from? why are we mostly good? why does evil exist?

Gropnik fulfills his subtitle’s “about modern life” promise with his own stimulating, hard-won insights about human nature. Take this aside:

Marriages are made of lust, laughter, and loyalty, and though the degree of the compound alters over time, none can survive without a bit of each one. We can usually infer the presence of all three from the presence of one; people are loyal to each other because of remembered pleasures, and they remember social pleasures because they remember sexual ones. All good marriages are different, but they are all alike in having the three elements in some kind of functioning, self-regulating balance.

[Adam Gropnik: author, essayist, journalist]

Well, who’d care to argue?I knew Gropnik previously only through his New Yorker essays on diverse topics. Angels and Ages and his recent fierce essays on Trump, such as “The Dangerous Acceptance of Donald Trump,” have cemented my admiration of him as a writer, a thinker, and a passionate citizen of our troubled republic. Speaking of which, I’ve lately become a fan, as well, of Amy Davidson, who also contributes brilliantly to the magazine’s election coverage on its web site. Gropnik and Davidson have joined New Yorker film critic Anthony Lane on my short list of favorite nonfiction writers now working. Lane has informed and amused me for years, and though his wit is hard to emulate, his parenthetical asides influence my own syntax.

In its own casual, learned asides, Angels and Ages is evidence of the benefits of lifelong reading that stocks one’s mind and feeds one’s intellect. What remains is what you learned—and what you end up saying or writing. Gropnik’s book also models deep inquiry for the project at hand. And also of just trying to figure out life for oneself from experience. A modest enough task in the wake of Lincoln and Darwin, it’s a task inescapably and essentially human.

[Gropnik excerpted Angels and Ages in an essay for Smithsonian.]

Responding to a question on Charlie Rose’s “Green Room” show, Adam Gropnik listed his five desert island books:

• James Boswell’s Life of Johnson because it’s the “most entertaining biography in the language.”

• Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations because it’s the “most perfect work of art of any novel in the language.”

• J.D. Salinger’s Nine Stories because they are the “most perfectly formed of American stories.”

• James Thurber’s The Thurber Carnival, his anthology of his writing because “it’s the first book I loved, at the age of seven, and it continues to illuminate and inform what I try to do.”

• And the works of Shakespeare because “if you have all of Shakespeare you have all of life.”

The post Two titans of prose appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

July 13, 2016

My editor speaks

[Cheri Lucas Rowlands’s tiny house in California. Photo: Cheri Lucas Rowlands]

Cheri Lucas Rowlands on life & writing in the real & digital worlds.

[Cheri Lucas Rowlands: story wrangler]

In a slightly earlier era, Cheri Lucas Rowlands might have written for newspapers or magazines. She’s got a similar but more fluid job, one not nearly so place-bound. She works remotely: when she’s not at home in Sonoma County, California, she travels the world, writing, editing, and taking photographs for herself and for the internet publishers who employ her.Rowlands is a “story wrangler” and editor for San Francisco-based Automattic, the parent company of WordPress.com and Longreads.com (among other products). WordPress is the world’s most popular web and blogging software, and currently powers over 60 million sites on the internet. This very website runs on WordPress software, though when I launched it—eight years ago this month—I started on the hosted version, WordPress.com.

I met Rowlands when we were classmates in Goucher College’s MFA program in creative nonfiction, 2005-2007; in fact, she may have been one of the twenty-somethings I asked back then about which blogging platform to use and was told “go with WordPress without a doubt,” which turned out to be solid gold advice. Knowing Rowlands gave me confidence recently to pitch her my essay “Why I Hate My Dog,” which she liked and passed along to the editor-in-chief of Longreads, who gave it the green light and returned it to Rowlands for editing.

As I explained in my last post, after working with me on my essay, she agreed to answer some questions about editing writers, online publishing, blogging, Longreads, Automattic, and her career in the digital world of writing and publishing.

Q. Longreads is such an interesting mix of nonfiction. There are famous writers, newsy stories, and now, apparently, quirky essays like mine from left field. What are the goals of your burgeoning site? Why should writers pitch Longreads instead of, or as well as, a site like Slate?

I admired Longreads from afar, before it joined Automattic in 2014. I liked discovering writing that was recommended by fellow readers, and loved that all of this happened on Twitter—that I could broaden my reading experience simply by following a hashtag (#longreads). So when Longreads joined Automattic, I was thrilled. Longreads has grown to publish exclusive and original reader-funded storytelling, from both established and emerging writers. It’s great to see how it has published a mix of in-depth journalism and high-impact stories in a short time.

Mark Armstrong, who founded Longreads in 2009, has shared his insights on the whys behind Longreads. In his post about being a better editor, he wrote about the advantages that we can offer our writers: establishing deep, lasting relationships with writers; helping them to produce the highest-quality work; and promoting stories to a strong, loyal following of publishers and readers. On Longreads’ seventh birthday this past April, he also talked about our continued dedication to produce original longform stories.

Personally, I’m eager to work on stories that introduce me to new ideas and topics; I knew nothing about Jorge Luis Borges before I worked on “Borges and $,” for example, and it was a bit intimidating at first, but ultimately a wonderful way to stretch myself—and get to know Borges and his work. Building both an editor-to-writer and writer-to-writer relationship is also important to me. I continue to grow as a writer, and I’m interested in working on stories that push me as a writer as much as an editor.

[Cheri Lucas Rowlands works remotely and took this while traveling in Lisbon.]

Q. How do you see your role as an editor?

I’ve worked in editorial in some form for 20 years—as a high school reporter, newspaper book reviewer, magazine fact checker, marketing proofreader, freelance travel and education writer . . . But it’s only since being an editor at a blogging company that I’ve felt truly comfortable as an editor. Over the past four years, I’ve become more adaptable.

Automattic is the first tech company I’ve worked for. It’s been a learning experience working in an environment in which the majority of people are not writers, but developers, data scientists, and others with more technical backgrounds. Externally, I’m also engaging with bloggers every day from around the world, all with different needs, interests, voices, and computer skill levels. I continue to adapt on both fronts, doing a variety of tasks and working with all kinds of content —copy inside an app, in your blog’s dashboard, on a technical support page, across official social media profiles, but also publishing author interviews, company announcements, and now longform pieces for Longreads. My job title—story wrangler—reflects most of my day-to-day work quite well: I herd words and stories.

Working on and editing for Longreads is different. It’s less about multi-tasking and dipping in here and there, and more about slowing down and going deeper into a project. I’m reminded of our MFA years at Goucher College: reading, writing, and thinking about writing all the time and losing myself in others’ worlds.

[Rowlands’s laptop in blogging mode.]

Q. You’re also a popular blogger! How is your blogging evolving? What about the blogging genre itself?

Like you, I started my site eight years ago, and I’ve experienced growing pains since, and especially after evolving into somewhat of a public face for the WP.com platform. I’m not sure how many times I’ve retreated into myself, turning away from the readership I’ve amassed on my blog, afraid to publish something that’s not perfect or unhappy because I now write less for myself and conflate writing with publishing.

I like to try other platforms, like posting on Medium, creating photo essays on Exposure, or experimenting on now-defunct spaces like Hi and Maptia. Nothing else ever sticks. Other services feel like rented space, and I always come back to WordPress.com, which I consider my online home. But I certainly get restless—periodically changing cherilucasrowlands.com from a blog to a static website and back to a blog, switching themes several times a year—which is a natural response, I think, like renovating a physical home. I’m reminded of Frank Chimero’s piece on digital homesteading: “I want a unified place for myself—the internet version of a quiet, cluttered cottage in the country.”

I’ll read the “blogging is dead!” proclamations from time to time, but I generally tune out the noise. Whatever you want to call it: blogging, online journaling, writing in real time for an audience—that fundamental human urge to express yourself won’t go away.

Q. What’s the relationship of your blogging and your other writing?

[Rowlands in London train station: Paris-bound.]

I recently excavated bits of my graduate manuscript and put it out there (my blog’s “1997” category), which was very much a personal thing, as I needed to close that door. During my time at Goucher, some of us may have had blogs, and I’m sure I could have found classmates on MySpace or whatever I was using those days. But I was too focused on writing. I can’t imagine doing an MFA today and blogging and (social) sharing my way through it. I’d be too distracted!Dani Shapiro once wrote a lovely New Yorker piece on memoir in the age of social media: “I worry that we’re confusing the small, sorry details—the ones that we post and read every day—for the work of memoir itself.” If I was blogging while writing my manuscript, it would have been a different experience.

But I revisited and published parts of my memoir on my blog because I was also trying to get excited about writing again. Being on a blogging platform all day, every day, has made it more challenging to write just to write. Posts, instead, have become social media updates: declarations, documented highs or lows of my life. So I’m happy I’m now editing longform pieces at Longreads—diving into that shared space with another writer, rediscovering the process of writing. Ultimately, I like this balance in my work: the ability to face outward into a glowing screen and connect with bloggers from all walks of life, but also the opportunity to retreat inward, in that more intimate space I’ve neglected since my MFA.

Both modes are important. And even though blogging consistently and confidently isn’t easy, I value being able to publish to an immediate audience, and to contribute to conversations happening now.

Q. Your career seems uber cool, and I wonder what life and educational experiences have led you to it?

All of my internships, jobs, and travel experiences have led me to my position at Automattic. I’ve always enjoyed writing, even when I was a little girl, so I sensed I’d hone that skill no matter what I did, and whether or not a job directly involved writing. That was the case when I was a teaching assistant in a sixth grade language arts classroom—I wasn’t writing, but I was reading and grading papers, talking to kids about their essays, and chatting about literature in small groups. And when I was a proofreader at a women’s college, proofing ads, admission brochures, and course catalogs, I wasn’t really writing then either, but I was working with words, and continuing to build a very broad skillset.

I caught the travel bug early, especially after a visit to Paris when I was thirteen, and traveling frequently has prepared me for writing and editing on the web, arguably as much as my editorial jobs. You have to be pretty nimble and aware of what’s going on in the world, especially while working for a global platform like WordPress.com, on which you’re potentially reaching millions of readers. I’ve learned to be more open, flexible, and empathetic from my time studying, living, and working abroad. These experiences have been invaluable and have helped me shape a perspective that makes my work better.

[In Macau, an autonomous territory beside China. Photo: Cheri Lucas Rowlands]

Q. It’s hard for me to picture what must be a fast-evolving, fluid work environment in the online realm. Are you able to travel and work remotely?

Yes, I can I work from anywhere I can connect to the internet! Automattic is a distributed company, so its nearly 500 employees can work from any location they choose. We work from home, in coworking spaces, from RVs or tiny houses (that was me for the past year!), or are completely nomadic. We have a physical office in San Francisco, but the majority of the company is scattered across 45 countries.

It’s such an interesting setup that works, and I now can’t imagine working any other way. The bulk of our interactions are text-based: we communicate and interact on Slack and on internal team and project blogs called p2s, where conversations are transparent and searchable. We have occasional video hangouts. We rarely use email. There are spaces for high-level discussions, project updates, and watercooler-like chats about everything from our company culture, the tech industry, our passions, and our lives. And so, much of my world unfolds on this very screen, where I type these words.

Before Automattic, I juggled part-time jobs with freelance work for a newspaper and several websites, so I’m used to bouncing around and working from home. I’m also pretty introverted and self-directed, so this setup works well for me. But I know working remotely isn’t for everyone.

Q. Besides Longreads and blogs on WordPress, what are you reading these days that excites you, online or off?

I can’t say I’m loyal to any publication nor have any favorites. But broadly, I enjoy reading about home and identity (I’m reminded of this piece from Guernica), and writing about living with technology that isn’t too academic (I occasionally come upon essays in The New Inquiry, and have read a few pieces in the fairly new Real Life mag, but otherwise, I welcome recommendations for more literary nonfiction about life in our tech and social media age). While I don’t do any long distance running anymore, I’m interested in fitness, running, and ultrarunning stories, and writing about outdoor adventures and national parks (I tend to enjoy the features at Outside).

Interestingly, I’ve become fascinated with, umm, poop. For the past year, my husband and I have been using a simple bucket toilet and composting our waste, which has been a surprisingly great, eye-opening experience. As a society, we use so much clean water to flush away our waste. I suppose my (tiny) living situation over the past year has opened my eyes to a lot of things, so I also like to read about minimalism, people’s relationship to space and stuff, and alternative energy.

Interestingly, I’ve become fascinated with, umm, poop. For the past year, my husband and I have been using a simple bucket toilet and composting our waste, which has been a surprisingly great, eye-opening experience. As a society, we use so much clean water to flush away our waste. I suppose my (tiny) living situation over the past year has opened my eyes to a lot of things, so I also like to read about minimalism, people’s relationship to space and stuff, and alternative energy.

[My last post told the story behind my essay Rowlands edited, “Why I Hate My Dog.”]

![[Belle at the beach, January 2014.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1468489506i/19711752._SX540_.jpg)

[Belle in Florida, a photo Rowlands chose for “Why I Hate My Dog” on Longreads.]

The post My editor speaks appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

July 6, 2016

My dog tale published

[Sure Belle looks cute here, but you have no idea the mayhem she causes.]

Writing about our crazy canine teaches me (again) about essaying.

At last I’ve documented our family dog’s epic weirdness—and, well, mine. My essay “Why I Hate My Dog” explains on Longreads. Bottom line and fair warning to the rescue-minded: every adult pound dog I’ve known or heard about has suffered from scorching separation anxiety. Belle’s is far from the worst—at least she doesn’t tear apart the house—but plenty bad. Her suffering, plus some truly odd behavior, affects her humans.

Especially me. Hence my wife’s suggestion that I write about Belle. “Your essays are getting too dark,” Kathy said. “Writing about Belle would be fun.” She was right. And I did try to channel David Sedaris, which helped me forefront the humor of living with Belle’s quirks. Of course dark notes crept in—well, serious ones. Because I can’t help but think ill sometimes about Belle’s previous owners. And because there’s poignancy in living with dogs, or almost any pet, that shares one’s emotional life but whose own life ends so much sooner than ours.

In Shepherd: A Memoir, I wrote about Belle’s predecessor terrier, Jack, whom I revisit here. Happy Jack looks great in comparison to neurotic Belle, though that’s relative. Once, for instance, he hopped on our dining table and consumed a large triple-anchovy pizza. That’s a new story about him in “Why I Hate My Dog.”

But Belle’s the focus. Here’s a snippet depicting her emotional fragility:

I pretend I can’t see her crouched amidst our bedclothes where she isn’t permitted, because she’s so ostentatiously suffering. Radiating tension, her head up and rigid, her face narrows, the taut line of her black lips forming a rictus of agony, much like the death grimace on the face of Jack’s possum; her paws grip our down comforter as if tornadic winds are clawing at her. She’s capable of spending an entire day like this, suffering an eventual human exit, especially when we vacation.

And one about mine:

Yet just last night—actually in the wee hours of this morning, at the ungodly time of two o’clock—she again performed her lone, great, silent service: keeping me company. I’d come wide awake, twitchy with vague anxieties, which soon attached to recent fears and old regrets. When my feet hit the floor, Belle stood in her warm bed beside ours. She trotted downstairs with me. In the light of day, I can take for granted Belle’s shadowing me from room to room; her steady presence seems to reflect her own insecurity, and I can ignore or mock her. At night, stranded in the darkness, I can’t. So I had felt grateful to Belle. I worried that she’d climb the stairs, nestle into her cozy nest, abandon me. She didn’t; she never does.

[Daughter Claire with Belle.]

The latter passage epitomizes what I love about writing, the way in making meaning it leads to new insight. And getting there is what frustrates me too. “Why I Hate My Dog’ began as a comedic riff on our needy dog. My realization about my dependence on Belle came very late. The draft had been “done” for weeks, and actually had been accepted by Longreads—I was getting ready to email it for editing.But the longer I lived with my account of Belle, the more I could hold her portrait in my mind. And then I saw that our sharing the dregs of the night was central to conveying our relationship and our emotional connection. It showed her loyalty and her awareness of my need, showed the reciprocity of her companionship. Similar late breakthroughs occurred this summer in another allegedly finished essay.

It would be wishing too much for writing to get easier, I know. But in each case, sweet insight fell into my lap only after months of work on these medium-length essays. I hope I’m learning better to sense when a piece isn’t quite done! But it seems I must accept that harvesting only low-hanging fruit isn’t enough. Getting donked on the head by high-hanging fruit is probably part of the writing process. When I think about it, I realize this usually happens, to one degree or another, when I write.

Formal pre-publication editorial tweaking of “Why I Hate My Dog” was accomplished via back-and-forth communication between me and my Longreads editor using Google doc. I knew of it, but hadn’t used it. I liked it. Familiar with trading Word-markup files by email, once I got used to Google doc I enjoyed its shared-meeting-space feel. Somehow less pressure—we’re just talkin’ here! A neat collaborative back and forth. Plus whenever I see my work in a new format or even in a changed display, new stuff jumps out. Ideas and diction fixes arise. And they did, again.

[One halloween: She has never forgiven us.]

Briefly this essay has made me more tolerant of others’ bad dogs. This morning, Kathy and I passed a man on our walk being dragged along by a snarling dog. We sometimes see him, and I dread it. Though I hold that hound against him, Kathy greeted him. His response was slow and a tad sullen—we’d disturbed his peace, too, even though his canine was the one wanting to kill Belle and maybe us. Then we ran into him again on our loop. He was friendlier, saying by way of possibly ironic apology for his dog, “He loves everybody.”“I guess he’s trying to be funny,” I said when he was out of earshot.

“I don’t think so.”

“Maybe that dog was his kid’s, who died,” I offered. “The kid kept it in his room, never socialized it. And now dad’s stuck with it.”

“Maybe it’s a rescue he got to keep himself company in his old age,” Kathy said, more realistically.

By definition, almost everyone is doing his best, right? Sometimes that’s pretty pathetic. But it goes for me and Belle, too.

[Next: an interview with my Longreads editor, Cheri Lucas Rowlands, about working with writers and her career in the digital world.]

The post My dog tale published appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

June 29, 2016

The joy of style

![[I took this photo somewhere in the British Isles, summer 2012.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1467353713i/19582135._SY540_.jpg)

[I took this photo somewhere in the British Isles, summer 2012. @richardgilbert]

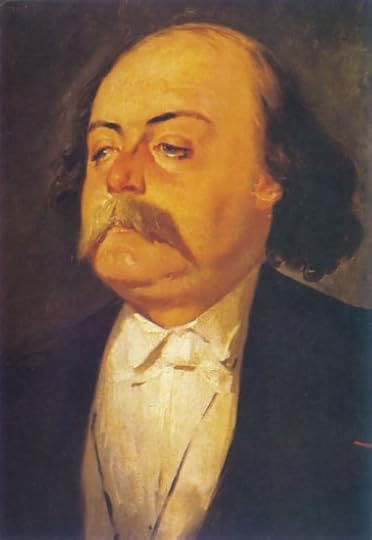

How Fiction Works unveils narrative craft—including memoir’s.

Review continued of How Fiction Works by James Wood. Picador, 248 pp.

Part 2. James Wood’s 2nd principle concerns prose built upon details

[I]n life as in literature, we navigate via the stars of detail. We use detail to focus, to fix an impression, to recall. We snag on it.—How Fiction Works

[Gustave Flaubert, portrait by Eugène Giraud]

If free indirect style (close third-person narration) epitomizes the novel’s history, according to James Wood in How Fiction Works, so does what he calls “the rise of detail.” Details allow us to “enter a character” but refuse to explain him, giving readers the pleasure of mystery and of co-creation. Wood credits French novelist Gustave Flaubert (1821–1880) with uniting details, stylishness, and close third-person narration to launch the realist novel that has persisted. The modern novel “all begins with him,” says Wood. Its hallmark is an approach that stamps its prose:We hardly remark of good prose that it favors the telling and brilliant detail; that it privileges a high degree of visual noticing; that it maintains an unsentimental composure and knows how to withdraw, like a good valet, from superfluous commentary; that it judges good and bad neutrally; that it seeks out the truth, even at the cost of repelling us; and that the author’s fingerprints on all this are, paradoxically, traceable but not visible. You can find some of this in Defoe or Austen or Balzac, but not all of it until Flaubert.

Style begins with what the writer notices—or notices on behalf of her characters—and uses for calculated effect. And yet, in its particulars and overall effect, narrative art retains mystery. A pleasure of How Fiction Works for me was Wood’s joyous riff on one of Virginia Woolf’s lines from The Waves:

The day waves yellow with all its crops.

“I am consumed by this sentence,” Wood admits, “partly because I cannot explain why it moves me so much.” While Woolf’s diction and syntax are simple here, her brilliance resides in having the day wave instead of the crops, he says, and “the effect is suddenly that the day itself, the very fabric and temporality of the day, seems saturated in yellow.” But how can a day wave yellow? That’s the thing, Wood notes: yellowness has taken over even our verbs, has “conquered our agency.”

How style and narrative point of view fuse

[James Wood explains the novel]

So according to How Fiction Works, fiction works via point of view (see my first post) and style built on details. That’s it? Pretty much, yes, that broad point and all its subtlety, according to Wood’s little red book. Including of course how perspective and style are inextricably bound. This occurs because the novelist is always working with at least three languages, Wood says:There is the author’s own language, style, perceptual equipment, and so on; there is the character’s presumed language, style, perceptual equipment, and so on; and there is what we would call the language of the world—the language that fiction inherits before it gets to turn it into novelistic style, the language of daily speech, of newspapers, of offices, of advertising, of the blogosphere and text messaging.

Contemporary novelists especially feel this pressure of tripleness, Wood says, because the language of the world has so thoroughly “invaded our subjectivity, our intimacy . . .” The tension just between a novelist and her point-of-view character is constant. (Of course characters are built of details, and they notice details that further reveal their “minds.”) How challenging to render layers of perspective, perhaps explaining novelists’ delightfully pungent essays where they can just be themselves.

Take David Foster Wallace, so talented and exuberant a stylist, who in order to do his fictive job well became a master, in Wood’s view, of “the whole of boredom.” Novelists, perhaps especially including Wallace, often dominate their characters—“write over” them, in Wood’s phrase. But to shirk the world’s dross entirely, to fail to get one’s hands dirty in another consciousness, risks imaginative failure: “the cold breath of an alienation over the text.”

There’s not much on structure in How Fiction Works, giving an odd relief from that obsession. With his steady focus on point of view and style, Wood illuminates fiction, and implicitly memoir, in its deepest core principles and finest subtleties. Such criticism enhances appreciation of narrative artistry for readers and practitioners alike.

[Part 1 of this review dealt with Wood’s consideration of point of view.]

The post The joy of style appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

June 22, 2016

Got perspective?

How Fiction Works by James Wood. Picador, 248 pp.

Part 1. The nuances of point of view in storytelling

In any long fiction, Henry James remarked, use of the first-person point of view is barbaric. James may go too far, but his point is worth considering. First person locks us in one character’s mind, locks us to one kind of diction throughout, locks out possibilities of going deeply into various characters’ minds, and so forth.—John Gardner, The Art of Fiction

In an essay for Prime Number, writer Buzz Mauro wryly reports his effort to track down Henry James’s supposed slur, as codified rather astringently by John Gardner—a noted third-person man:

I can find no actual instance of James describing first person as “barbaric,” but he did call it, in the preface to The Ambassadors, “the darkest abyss of romance … when enjoyed on the grand scale” and added that “the first person, in the long piece, is a form foredoomed to looseness.”(3) Not quite “barbaric,” but quite a condemnation.

Indeed. Ah, lovers’ quarrels.

In How Fiction Works, James Woods argues for omniscience. He first contrasts the alleged barbarity of first-person against W.G. Sebald’s disgust for omniscient narration. Whereas the “uncertainty of the narrator himself” lends credence to first-person, Sebald believes, history has shattered the myth of cohesive worlds and all-seeing authors. To Sebald, omniscient third-person narration is a “kind of cheat,” Wood writes.

Not to Wood. How Fiction Works is a brief for, and a subtle analysis of, omniscience in fiction. Though ostensibly a godlike, distancing method, in practice third-person narration tends to “bend itself around” a point-of-view character.” Wood loves such “free indirect style,” also called close third-person, in which characters’ thoughts have been freed of “authorial flagging,” such as “he said to himself” or “he wondered.” The narrative, seemingly less mediated, becomes suffused with a point-of-view character instead of the novelist.

At the same time, this particularized outlook and diction blend with that of the “complicated presence of the author” to achieve a nuanced layering. Simply put, we enter a character’s head, savoring his thoughts and impressions, while also admiring the writer’s skill—and noting her “own” words or phrases. We enjoy signals of writerly perspective and commentary embedded among characters’ feelings. Sometimes we’re not entirely sure who owns a word, Wood points out, and we try to discern, say, whether the author is being sharp or kind toward a character. In any case, we’re aware of the gap between writer and character. And into that created and creative space, irony, the driest humor, flows.

Fittingly, Wood’s great example of free indirect style pinpoints a sentence by Henry James. In What Maisie Knew, James writes about an unloved girl torn between two selfish, divorcing parents. Here Maisie muses on her comforting, vulgar governess, Mrs. Wix, and her lost child, Clara Matilda:

Mrs. Wix was as safe as Clara Matilda, who was in heaven and yet, embarrassingly, also in Kensal Green, where they had been together to see her little huddled grave.

Wood notes that in James’s sentence “genius gathers in one word: ‘embarrassingly’ ”:

The addition of the single adverb takes us deep in Maisie’s confusion, and at that moment we become her—that adverb is passed from James to Maisie, is given to Maisie. We merge with her. Yet, within the same sentence, having briefly merged, we are drawn back: “her little huddled grave.” “Embarrassingly” is a word that Maisie might have used but “huddled” is not. It is Henry James’s word. The sentence pulsates, moves in and out, toward the character and away from her—when we reach “huddled” we are reminded that an author allowed us to merge with his character, that the author’s magniloquent style is the envelope in which this generous contract is carried.

[POV Master: novelist Henry James]

Such layering of perspectives fosters a similar, if usually much more overt, reflective dimension in a memoir or essay. A dual point of view—you then, living; you now, writing—is considered a sin qua non of literary nonfiction. This aspect of narrative seems more subtle in fiction, until I recall Tobias Wolff’s This Boy’s Life and Alison Smith’s Name All the Animals (). In those exquisite memoirs, authorial distance is signaled through sparing, subtle changes in voice instead of through outright commentary (none in Smith’s case; rare in Wolff’s).While a strongly dual persona is an aesthetically approved choice in nonfiction—and prudent for any number of other reasons—master writers will break such a “rule.” They’ll get away with it, if only by substituting subtlety in execution for prescriptive heavy-handedness.

[Next: In Part II about How Fiction Works, I’ll consider Wood’s second major narrative element: style and its relationship to point of view.]

The post Got perspective? appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

June 15, 2016

Poetry & prose

As an artist you are not merely concerned with getting your meaning across, or you would just write expository prose. You want to generate interest and involvement with the language as well as with what it says.—Judson Jereome, The Poet’s Handbook

Compass and Clock by David Sanders. Swallow Press, 72 pp.

I wonder how many prose writers unconsciously draw on the rhythms and content of the poems they read as children? The longer I write, mostly nonfiction in my case, the more poetry I read. Poetry’s distilled wisdom feeds me as a person, and its precise diction and careful phrasing nurture me as a writer. Poetry grows your literary intelligence and seeps into your sentences.

Formalist poetry—which employs meter and sometimes rhyme schemes—enchanted me during my nine years as book publicist and then marketing manager for Ohio University Press/Swallow Press. David Sanders was the director then, a poet and a publisher of poets who launched the Press’s esteemed Hollis Summers Poetry Prize. We didn’t publish only formalists, and poetry collections of any kind constituted a handful of our annual publications, but they were among our most interesting. I moved on, and later so did Sanders, but our old Press, now led by Gillian Berchowitz, has just published a new collection of his poetry, Compass and Clock. In it, Sanders mixes free-verse poems with those that employ formal elements. The book was elegantly designed in-house by Beth Pratt, using Jeff Kallet’s collage “Sunrise” as the cover’s striking image.

I’ve read Compass and Clock twice. There’s the strangeness of true art in odd little poems like “He Was Once,” about a man who drives a widow to a mountaintop to watch an incoming storm. She’s alarmed when the man compares himself “to the quiet air”:

calling it yellow, volatile but unshaken.

Beyond the pass, they saw as they sat there

the clouds massing. And she asked, as if from another

life, as he sat gazing out, to be taken home.

Such a great, weird moment, resonant, full of mystery. The kind of thing you might remember forever but not understand. Sanders made it up, he told me. He sketched the opening portrait of the man—maybe young and sensitive, maybe odd, maybe just literary—who was once “amazed by simple things,” based on Sanders’s own experience of seeing his shadow on a lawn in the moonlight. The spooky rest, he imagined.

Along with his witty wordplay and his poetry showcasing, as poetry does, the power of metaphor, I was struck by Sanders’s spare, precise descriptions. The “thin curtains” in one poem seemed so perfect, telling, and sad. One of my favorite narrative poems in Compass and Clock, “The Mummy’s Curse,” is about a man returning to his hometown to bury his father. Stopping at an orchard’s roadside stand, he sees a woman he once knew but doesn’t recognize. She’d stayed in that smaller world, and she recognized him instantly. Whereas he, who’d traveled and seen so much more, just saw another person—until she broke the spell of his blinkered drifting. Such a deft way to express the adult truth of feeling like a ghost in old haunts. Despite his worldliness, he sees, the “change was theirs”: having grown in place, they looked different to him, whereas time for him had stopped, as if by death, having left his roots.

In such story poems, I like to mentally remove their line breaks and see how they’d function as flash essays. (Sometimes nicely, as in this poem; sometimes you can hear an editor’s cry for the person to reveal “what’s at stake,” reveal why this story, why now?) Narrative, to me, salves some of the inherent melancholy of poetry. But I think because of that quality, poetry seems mature to me, like adults of a certain age. Maybe literature itself is inherently elegiac because it’s at last about memory, and therefore about loss, our fleeting lives set against the ongoing ruination of time. Many of Sanders’s poems deal with memory, and therefore with vastly separated time frames, with adulthood’s losses.

The formal poems and riffs on form in Compass and Clock intrigued me. There’s plenty satisfying “blank verse,” iambic pentameter’s classic five-beat line. I wondered if Sanders had snuck in a classic structure to boot, such as a sonnet, and sure enough counted 14 lines in the two stanzas of “Here, Now,” on a page I’d dog-eared. In the first eight lines, a man watches a group of restless young punk rockers loitering on a summer evening and feels his separation from them; in the final six lines, he remembers his own garage-band youth in Ohio “without imagining it would come to this.” It’s a loose sonnet, the rhymes random rather than regular, though true to its form with that distinct turn after the octave, as the man goes inward and pensive.

What surprise lurks in form for poet, I imagine, and certainly for reader. This is allied with what I envy as a writer about poetry: its employment of an ongoing sensibility instead of only experience, autobiography. Though I suppose we never run out of memory—there’s always yesterday!—the big stuff of the past gets used, or tiresome. And yet there you still stand.

Sanders, the founding editor of Poetry News in Review, hosted online by Prairie Schooner, has published his poems and translations in journals and anthologies, and in two limited-edition collections, Nearer to Town and Time in Transit. He now teaches English at Ohio University and remains associated with its Press, serving as general editor of the Hollis Summers Poetry Prize. We met to discuss Compass and Clock, over a long lunch at a barbeque restaurant in Logan, Ohio, and then traded emails, in which he tackled the questions below in bold.

Q. There have always been holdout “formalist” poets, but for decades, free verse poems displaced those with meter and/or rhyme, at least in terms of number. Lately there seems to have been a resurgence, or maybe it’s an absorption, of more formal elements in the mainstream. Though not all your poems employ a metrical or rhyming scheme, many do—and your various combinations are exciting: “The Fossil-Finder” is free verse yet rhymed. What do meter and rhyme add to poetry? Why does subtle blank verse, iambic pentameter, still feel so right? Are Shakespeare’s soliloquies in our blood, or did something earlier put iambic pentameter in our marrow?

DS: Rhyme and meter are matters of craft and history as much as anything else. As a reader, I do have a physical response to rhythmic patterns, of which iambic pentameter is the predominant one in English verse. The response is one of anticipation and gratification. But it doesn’t have to be iambic pentameter. In the poem you mentioned, “The Fossil-Finder,” there is a recognizable though irregular beat in the first four lines:

Leaving the house far behind,

while his friends, two lovers, quarreled,

he studied the ground at his feet to find

a proffered world.

[Sanders: seeking “subtle fulfillment.”]

My hope as a writer is that the reader can discern the modulation even if it isn’t a regular rhythm, and that the play of the rhythm in concert with the natural syntactical phrasing of the language provides the reader something familiar and physical riding beneath the words. The same holds true of the rhyme. Whether it’s end-stopped (coming at the end of a phrase) or internal (buried within the syntactical unit) the similarity of sounds resonates to varying degrees. When it’s done well, the effect is one of subtle fulfillment.But I use these devices for a more pragmatic reason too. They allow me to go places I would not necessarily go if left on my own, so to speak. The path I take by employing these devices is usually more interesting, indirect, and surprising to me than the path I would take if I just wrote down the first thing that came to me. In a sense they act as obstacles in my path, forcing me to think differently about what I think I want to say, and taking the poem in unexpected directions.

Although I have heard for decades the argument that there is a connection with the heartbeat and the iambic pentameter line, I do not believe that is the case. The simple reason is that there are other cultures for which the parallel of the ta-dum of the iamb and the ta-dum of the heartbeat isn’t present because the idea of the iamb doesn’t exist in some cultures. Japanese poetry, for example, is built on a syllable-like structure, not on a cadence like English meter. On the other hand, I think we, as humans, regardless of our culture, do have a primal sense of rhythm or rhythmic patterns. It manifests itself in everyday activities such as walking, running, washing our hands, or tapping our fingers on the tabletop while we wait for our drinks to arrive. It is even more evident in dance and music and song, the temporal arts, regardless of culture—though the rhythms themselves might be different. Verse straddles prose and song. It is the lyric after the lyre has been put down. As heightened speech, it wants to retain that rhythmic undertow without leaving its home on the page or as spoken word.

Q. There seems an affinity between nonfiction and poetry, perhaps because they both ultimately point to the writer’s own sensibility. But however much a particular poem “might work” as an essay, there feels a difference, something subtle. Maybe more of a mysterious moment caught in a poem, rather than an essay’s “clear point.” What does poetry try to do that’s, if not unique, distinctive to the genre? What do you try to do and like to see done?

DS: I think you’re right that there is an affinity between short nonfiction and poetry. The propensity for the lyrical moment is one common point. The deflection of the didactic urge is another, I think. But there are differences that are significant. Paul Valery said something to the effect that the difference between prose and poetry is the difference between walking and dancing. I like to think that the difference is that the point of prose is to be so well-made as to be transparent: we are seeing into the writer’s mind, the way it is working, and following the course of the thoughts. Poetry, on the other hand, always makes you aware of itself as it takes you on its journey. It risks the stark clarity of the unencumbered view for the rose window.

That awareness is accomplished in part through the devices described earlier of rhyme and rhythm, although good prose certainly enlists rhythmical energy to drive the rhetoric.

But more to the point, poetry, more so than prose, is likely to use tropes —figurative language—not merely to illuminate an image or idea but also to take the reader on the scenic route, wherein the metaphor might be the basis for the poetic dramatic situation or as a measure of the poem’s emotional weight. Think of the words trope, verse, and volta. Trope is a turn of phrase; verse has as its origin the image of the plow in the field turning to the next row, which is the picture of what happens in the lines of a poem; and volta, the Italian word for turn, is the rhetorical place in the poem, most widely used in reference to sonnets, where the meaning of the poem turns.

To the extent that both poetry and nonfiction are a sort of meditation on a subject, there is a commonality. But I sense that nonfiction is more apt to try to home in on the understanding of a thing, whereas poetry prefers to let it keep slowly turning, sometimes just out of reach. That is a pretty broad statement, which might not bear up under scrutiny.

Q. When an essayist says he puts an essay through 30 to 50 drafts, we basically know he works on it for one to two months, on average—each day writing, reworking, or polishing is a “draft.” I realize you must work on some poems for years, in the sense that you put them away at a certain point. But when you’re actively working on a poem—getting a solid draft, as it were—how long does that take? What’s your record for one that took long gestation?

DS: It’s hard to say. For the poems in this book, I would estimate that the average number of drafts was ten to fifteen per poem, and I normally spent two to three weeks on getting a working version of it.

There are some for which decades later I changed a few key words, completely altering the original meaning (For example, one poem I wrote in 1982 was revised last year in preparation for the publication of the book. I think it was an improvement.). But there are others, which, over years, have been collapsed and then re-purposed as parts of other poems. One that went through several violent revisions is a poem titled “River Where the Lovers Wait.” The title takes its name from a place in Thailand where my neighbor, working on his doctorate, studied bat viruses. I remember going home one summer and standing under the streetlight throwing pebbles in the air, taunting the local bats. I wrote a poem based on those two details, my action and his experience in Thailand—40 lines or so—as a dramatic monologue, then let it simmer for a few months till it reduced itself to seven lines:

Bats come here at dusk to hunt,

following the insects’ paths that loop

above the water. From the shore,

I toss a handful of stones in the air

and watch the bats dive then veer

from that wrong, unfamiliar pattern:

they, in their way, know better.

As I read the poem again now, I see that the only element from the dramatic monologue that was retained was the mention of a shore. There was no shore at the end of my parents’ very long driveway, just Ohio cornfields.

Q. I share my work-in-progress with other writers, and their questions and edits are helpful. At the same time, it’s humbling to see my dumb errors, gaps, and infelicities—sometimes in a fairly polished draft. Could you discuss your revision process, including whether you share draft poems with other poets?

DS: There are a very few people with whom I share my poems as I write them. They have different aesthetics from each other, so it’s informative for me to get their responses. I generally wait until I come to a point where I think the poem is finished or nearly so, or conversely where I have no idea if it is “working” or not. I’m less interested in editing per se, than in finding out if I’m on the right track. Just making it public (even if it’s a public of one other) is often enough to make me reconsider my choices. Most of the process is private.

The hardest draft is the first—going from the idea or image or phrase that triggers the poem and putting it down so that it has a chance to incubate. And I usually need to find a rhetorical entry point, a first line that gives voice to the poem: “Faced with going home again, / where you grew up and all of that” or “These days the chatter turns to friends / who’ve quit responding to our letters” or “This is the shower / that every day settles the dust.” For better or for worse, once that cadence has purchase it’s much easier for the rest to follow, even if only to be changed later. If the idea for the poem incubates solely in my head, there’s a good chance it will get lost for good, which might be for the best.

After I have committed it to paper, I will often try to recast it in a way that’s memorable to me, that is in a voice that is near my own, with a rhythm and phrasing that I can commit to memory and repeat to myself. I use that memorization to find the soft spots in the poem. If I continue to forget a passage, it usually means there’s a problem with it. As I mentioned, I will often use formal devices to generate a direction for the poem that is not in alignment with the original draft. That process gives me the opportunity not just to work out problem passages but also to let the poem turn itself over in the back of my head while I’m working out the smaller details. At least that’s what I imagine is going on. From time to time, I will print out large-scale versions of the poem and hang them in my room and just leave them there so I can reassess them from time to time as they catch my eye. I’m in no hurry.

Q. Poetry has a passionate audience. But of course some readers have found poetry too challenging. Who are some classic poets who are more accessible than we remember from high school English? How can prose writers benefit from reading such poetry? Who are some modern masters, including formalists, we ought to read?

DS: Not to be contrary, but I think poetry is meant to be at least a little challenging. Emily Dickinson and Robert Frost are challenging if you spend any time with them. The question is whether or not you are rewarded for accepting the challenge and investing the time and energy. With Dickinson and Frost and more recent poets like Seamus Heaney and Richard Wilbur and Elizabeth Bishop, the answer is “yes.” Accessibility in discussing poetry is almost a trigger word for me, akin to relatable. Eliot said that “genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood.” There is something to that. Still, I think most people would be able to appreciate the work of poets as removed from one another as Pablo Neruda and Philip Larkin, without much trouble.

A very small sample of some of my favorite contemporary poets includes Lucia Perillo, Timothy Steele, Joshua Mehigan, and the late Nobel laureate Wisława Szymborska. Each is very different from the other, but each is interested in telling the truth but telling it slant, to paraphrase Emily Dickinson.

I think nonfiction writers might benefit from looking at work by the names I just mentioned if only to see the choices made in approaching the subject matter. Look at how these poets set up a dramatic situation and how the voices they adopt suit the poems. Consider how they skew our version of the world: making the ordinary strange and fresh, and the strange less so but also fresh. I think all good writing does that, but poetry makes greater allowances for accomplishing that than prose. For example, here is the beginning of a poem by Lucia Perillo titled “Blacktail”:

Like tent caterpillars, we cover the landscape with mesh

because of the deer, the ravenous deer.

They enter the yard with the footwork

of cartoon thieves—the stags wear preposterous

inverse chandeliers, the does bearing fetuses

visibly kicking inside of their cage. . . .

Listen how the repetition of deer rhymes with chandeliers and stags resonates with cage and how the description of antlers as “preposterous inverse chandeliers” is both an accurate description and comical. It’s comical to pronounce too—preposterous inverse chandeliers— that’s a mouthful and the humor is set up with the image of cartoon thieves. However, the comic element is cut by the idea of the deer starving and by the image of the fetuses kicking inside their cage, isn’t it? The juxtaposition of sounds and images is disquieting. Reading it aloud, with its line breaks and its many starts and stops, forces you to slow down the process of comprehension almost to the point of hovering over the individual lines.

This is a luxury that most nonfiction cannot afford. Still there surely must be something to glean from that. But I have to admit, writing nonfiction is a much more mysterious enterprise to me.

Q. Why do you say that?

At its heart prose is, I think, about telling stories. And I can’t tell stories. I remember when I lived in Arkansas, I would hear friends tell wonderful shaggy-dog stories, that would go on for twenty, thirty minutes, with little or no point—it was all in the telling. In my retelling of the same story I’d manage to boil it down to two or three minutes. So not only did it not have a point, there was no story there either.