Richard Gilbert's Blog, page 5

May 25, 2016

What has gone missing?

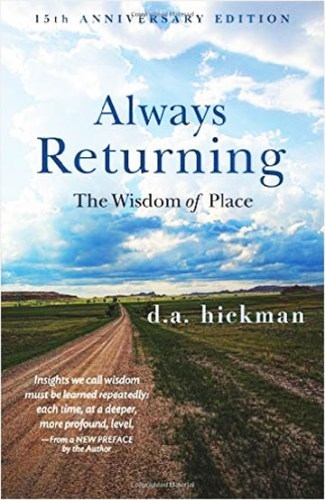

Changing the Subject: Art and Attention in the Internet Age by Sven Birkerts. Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press, $16.00 paperback original (272 pages). Cover art by Gerry Bergstein; cover design by Kimberly Glyder.

The Sorrow Proper: A Novel by . Ann Arbor, MI: Dzanc Books, $14.95 paperback (152 pages). Cover design by Steven Seighman.

Guest Review by Lanie Tankard

. . . the system of selection of information for the screen of consciousness is importantly related to ‘purpose,’ ‘attention,’ and similar phenomena.

—Gregory Bateson, “Effects of Conscious Purpose on Human Adaptation” in Steps to an Ecology of Mind

Serendipity occasionally tosses books together on a reader’s platter, thus multiplying the impact they might have had if encountered separately. If you like to chew on ideas, consuming books in combo can become an art as subtle as the pairing of food and wine.

Two titles from the year past are polar opposites in many ways, yet explore the same underlying idea: What have we jettisoned in our transition to the electronic era? One publication is a collection by an established older essayist on the East Coast and the other is a debut novel by a young emerging writer in the Rockies. Both authors edit literary journals. Each book in its own way addresses the digital conversion of our lives and the consequences of that progress. In their explorations of the Internet Age, both authors establish what has disappeared and then illuminate the ramifications.

Sven Birkerts, editor of AGNI, turns a searchlight on technology’s threat to creativity in his collection of seventeen essays (all previously published individually in a variety of journals). The titles in Changing the Subject: Art and Attention in the Internet Age are intriguing. A sample: “You Are What You Click,” “The Hive Life,” “The Room and the Elephant,” “Notebook: Reading in a Digital Age,” “Idleness,” “Bolaño Summer: A Reading Journal,” and “The Still Point.”

Birkerts examines what has occurred in the twenty-two years since he wrote The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age.

He pitches questions and then marshals quotes from well-known writers to augment his answers, sometimes agreeing with their points of view and sometimes not. As Birkerts converses with their ideas, he presents his own stance while at the same time enlisting the reader’s attention to consider the situation along with him. In this trifecta of discourse arises a wide range of names, such as Abraham Maslow, John Cage, Milan Kundera, Simone Weil, Max Frisch, Bob Stein, Marshall MacLuhan, Jaron Lanier, Michael Aggar, E.M. Forrester, David Lockhead, Rainier Maria Rilke, Edwin Bustillos, Nicholas Carr, Clay Shirkey, John Keats, Paul Cézanne, Marcel Duchamp, Walker Percy, Nicholson Baker, Jorge Luis Borges, Kevin Kelly, Michael Joyce, Vladimir Nabokov, Marilynne Robinson, Wendell Berry, Rebecca Solnit, and Seamus Heany.

Sven Birkerts inspects the electronic transformation process itself, looking for what has become different. For every modification, he focuses not so much on the new item or procedure, but rather on what it’s replaced. That quest remains his concern: Identifying what has been supplanted. Birkerts describes electronic droplets of data cascading into “an enveloping environment.”

Have we actually been narcotized to the point of dysfunction by too much information (TMI) though? Birkerts brings in neuropsychology and social hiving as he pits our increasingly collectivized existence against the solitude required for contemplative reading. He broods about the costs of multitasking, worrying: When a society’s attention becomes scattered and humans begin to lose the ability to become deeply engaged in reading novels, how does creativity adapt? How will our current trajectory affect art in all its forms as our neural pathways are altered and new abilities supersede old ones?

It took me a long time to finish this book, because the author offers vital ideas desperately in need of pondering. Changing the Subject is a far cry from being dry and dull, however, as Birkerts exerts a quiet wit in certain turns of phrase, such as “the whiplash of obsolescence.”

[Birkerts: digital doubter.]

He considers the effect on the overall gestalt of removing one property from the whole. Curious, he’ll play with the question: What have GPS systems eliminated from travel? Hmm, well, certainly getting lost, for one thing. Instead of stopping there though, Birkerts speculates on the implications of that elimination—on what has been given up to assure our perpetual pinpointability on this planet. Could it be the capacity to move into the unknown or encounter the unforeseen…in other words, an adventure? He muses about cell phones and the “expectation of reachability” they’ve placed on us. The “primal solitude” one gives up to carry such a wireless device kept him from owning a cell phone at all—until quite recently.Birkerts sees cloud computing casting a big shadow on Abraham Maslow’s idea of self-actualization as society moves from the individual to the team. If tangible objects are encoded and live in a cloud, his intuition warns him about the price of removing “physical markers of culture from our collective midst.” He discusses with eloquent passion what record stores and bookstores represent in our lives beyond the mere items they sell. Then he spends an entire lovely chapter on “reading,” concluding that imagination—the ability to visualize in the mind’s eye—is under dire threat. If we frame the old order as obsolete, needing it to move out of the way for the new, have we weighed the consequences?

The Internet as “a tool for the harvest of information” does not favor the slow work of contemplation necessary for the imaginings of our thoughts to flourish, Birkerts believes, predicting creativity will suffer at that crossroads. He calls the novel “a meaning-bearing device,” one that’s “an antidote to the Internet” because it’s a field for thinking. Through the deeper nature of fiction, a novel carries a reader into “a fully imagined otherness,” he states.

To move from the essays of Sven Birkerts, then, to the novel of Lindsey Drager is akin to thoroughly enjoying a hearty entrée and then sighing in cozy comfort at the sight of a chocolate truffle sitting next to the brandy snifter of Cognac. The Sorrow Proper is a fine finish on the palette, similar to the ideas sautéed by Birkerts but prepared for after dinner with a different recipe—that of fiction.

Drager stirs two main storylines together in her novel: (1) the lives of five older librarians facing the closure of their public library amidst the digitization of books and (2) the lives of a photographer removing his exhibit from that library and a deaf mathematician he meets there while doing so. The parents of a young girl who died in front of the library make several appearances as well, along with a bartender who recurs as a minor character.

In an elegantly parsimonious display of precise prose, Drager dissects the impending End of Print through the conversations of her small band of older librarians who meet daily after work at a nearby bar to consider their future. Her characters discuss their functions since the rise of the computer, determined to find meaning in a life that cares for books.

Transposed against this tableau is a photographer removing his pictures from the library’s walls while a deaf mathematician watches.

They become lovers. Their individual professions add philosophical depth to the evolving story. The photographer thinks about what develops in the dark. The deaf mathematician deliberates what the photographer does, taking into account all that he has recorded on film—and all that he has not. She pushes the significance of a “train of thought” as far as the tracks will go.

Death looms as a metaphorical cloud in this novel. Like Birkerts in his essays, Drager searches for what is no longer there—that which has been left out. The mathematician thinks about all the times we die before our actual deaths. The librarians start to view their library as a grave. The photographer realizes there are some worlds in which he and the mathematician have never met. Deftly Drager enlarges her story with the Many Worlds theory of quantum physics: Do our lives follow a singular, linear path?

[Drager: Elegant, precise prose.]

The librarians hash over what takes place during the act of reading a book. Meanwhile, the deaf mathematician asks her lover the thesis of photography. Later, he wonders how to quantify loss. She tells him math is a language. The librarians, too, discuss language and what the word “library” denotes in the Electronic Age. Everything echoes. The ending is poignant.Reading Birkerts and Drager together is a powerful experience, as the two books chorus related thoughts from parallel universes. It’s as if Dutch artist M.C. Escher had created a transformation print of books while they passed from one state to another—page becoming screen. Spellbound by the protuberant images, a viewer might blink and suddenly notice receding regions—all at once paying delayed attention to the in-between spaces, belatedly comprehending with escalating chagrin everything that was abandoned during the conversion, ultimately understanding all that once was.

Lanie Tankard is a freelance writer and editor in Austin, Texas. She is a former production editor of Contemporary Psychology: A Journal of Reviews, and has also been an editorial writer for the Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville.

The post What has gone missing? appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

May 18, 2016

Rhythm and blues

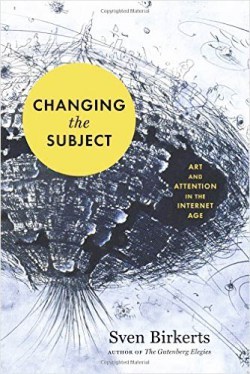

The Long Goodbye: A Memoir by Meghan O’Rourke. Riverhead Books, 297 pages

In the year after Barbara O’Rourke was diagnosed with advanced colorectal cancer, in her early fifties, her 32-year-old daughter, Meghan, became engaged, got married, and then separated. She changed jobs, divorced, started dating a man on the opposite coast, numbed out, and melted down.

Meghan O’Rourke portrays this siege of anticipatory grief in her celebrated memoir, The Long Goodbye. The title refers to the fact that she was granted time with her beloved mother. Diagnosed in May 2006, Barbara died on Christmas of 2008. But it also refers to the fact that Meghan’s goodbye to her mother will never end. Living without her remains like “waking up in a world without sky.”

Barbara and her husband both worked for many years for a private school in Brooklyn, before Barbara became a headmaster in Connecticut. As Meghan and her two younger brothers were growing up, the family spent summers at friends’ forest cabins and rural retreats. In O’Rourke’s portrait, Barbara enjoyed motherhood and fostered independence, creativity, and healthy self-esteem in her children; she exuded serenity and yet was wry and feisty. Barbara gave her daughter a blank journal when she was five that helped turn her toward writing. Now an accomplished poet, O’Rourke evokes life’s hardest passage precisely. At the same time, she muses on its meaning and recalls the past, including the many bone-deep gifts of love that fueled her pain.

She writes:

When we are learning the world, we know things we cannot say how we know. When we are relearning the world in the aftermath of a loss, we feel things we had almost forgotten, old things, beneath the seat of reason. . . .

When we talk about love, we go back to the start, to pinpoint the moment of free fall. But this story is the story of an ending, of death, and it has no beginning. A mother is beyond any notion of a beginning. That’s what makes her a mother: you cannot start the story.

But, oh hell, you keep trying.

When Barbara’s time came, at age 55, after protracted medical ordeals, the family gratefully called hospice. While praising hospice as a balm in her mother’s passing, O’Rourke shows that’s also a relative measure—because nothing’s great when your mother is dying. Barbara herself seems to achieve the hardest task, of letting go:

[R]esearchers now think that some people are inherently primed to accept their own death with “integrity” (their word, not mine), while others are primed for “despair.” Most of us, though, are somewhere in the middle, and one question researchers are now focusing on is: How might more of those in the middle learn to accept their deaths?

[Meghan O’Rourke, photo by Sarah Shatz.]

Although both her parents, ex-Catholics, were atheists, O’Rourke nonetheless grew up with “an intuition of God.” After her mother’s death, she yearns for mourning rituals and for the ancient recognition of grief she senses might linger in a church community. Her friends and coworkers scarcely know how to speak with her. O’Rourke conveys her loneliness and, more surprising to her, how lost she felt.“What is grief?” she wonders. This sends her into literature and out to interview experts. She learns that almost 90 percent of people experience “normal” grief, as she did, while “complicated” grief may require therapy. The book includes five pages of recommended reading. For O’Rourke, two texts became touchstones. Shakespeare’s Hamlet, often seen as being about a young man’s dithering over contingency, reveals itself as a portrait of his devastating grief. Another key book was C.S. Lewis’s memoir A Grief Observed.

The Long Goodbye is that rare book that made me think, soon after starting it, I want to read this again. O’Rourke has a sure sense of sentences, from simple declarations to lyrical descriptions, often with arresting turns of phrase. As Barbara actively dies that last Christmas, she makes “a madrigal of quiet sounds, as if to indicate that she was with us.” As well, O’Rourke tunes her sentences’ and passages’ collective rhythms. The book’s three-part structuring of its diverse content guides the reader. This story of personal loss becomes a window into death’s universal magnitude.

[O’Rourke wrote her memoir while working as an editor and writer at Slate, and nine core essays remain available there.]

The post Rhythm and blues appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

May 11, 2016

Writers on our political rhubarb

[Andrew Sullivan explains. Photo from Big Think.]

Donald Trump’s political success has provoked in recent months some fine commentary, much of it from moderates and progressives. I’ve especially enjoyed the New York Times’s crew. Even Thomas Friedman, whom I’ve boycotted since his disgusting promotion of the Iraq war, rose, once, to an unexpectedly eloquent height. Republicans have seemed mostly inarticulate with rage over their primary’s winner, given that Trump’s record is of a pragmatic moderate. At last, however, the likable Andrew Sullivan has expressed the intellectually conservative view.Published in the May 2 issue of New York Magazine, his searching essay “America has Never Been So Ripe for Tyranny,” has gone viral. In this classical essay he’s fighting for—with every persuasive tool he’s got—what he calls “America’s near unique and stabilizing blend of democracy and elite responsibility.” Speaking as it does to America’s worrying climate of factional resentment, I found the passage below intensely resonant:

For the white working class, having had their morals roundly mocked, their religion deemed primitive, and their economic prospects decimated, now find their very gender and race, indeed the very way they talk about reality, described as a kind of problem for the nation to overcome. This is just one aspect of what Trump has masterfully signaled as “political correctness” run amok, or what might be better described as the newly rigid progressive passion for racial and sexual equality of outcome, rather than the liberal aspiration to mere equality of opportunity.

Much of the newly energized left has come to see the white working class not as allies but primarily as bigots, misogynists, racists, and homophobes, thereby condemning those often at the near bottom rung of the economy to the bottom rung of the culture as well. A struggling white man in the heartland is now told to “check his privilege” by students at Ivy League colleges. Even if you agree that the privilege exists, it’s hard not to empathize with the object of this disdain. These working class communities, already alienated, hear — how can they not? — the glib and easy dismissals of “white straight men” as the ultimate source of all our woes. They smell the condescension and the broad generalizations about them — all of which would be repellent if directed at racial minorities — and see themselves, in Hoffer’s words, “disinherited and injured by an unjust order of things.”

Though Sullivan draws on a lifetime of experience, he notably cites Plato’s Republic, Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel It Can’t Happen Here, and Eric Hoffer’s 1951 tract The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements. Sullivan has come to critique our increasingly democratic (but perhaps less stable) political system that frightens him. He calls the Republicans’ fight to hold open a Supreme Court vacancy “another massive hyperdemocratic breach in our constitutional defenses.” And: “The vital and valid lesson of the Trump phenomenon is that if the elites cannot govern by compromise, someone outside will eventually try to govern by popular passion and brute force.”

As a man of good sense, Sullivan cannot help but cheer Barack Obama’s attainments. As a student of history who is by temperament a conservative, he cannot help but furrow his brow at the implications of such outsider politicians. Did Obama lead to Trump? Has our increasingly freewheeling democracy, inflamed by the internet and by growing economic inequality, led to both?

I understand his view but probably part ways with him over his conviction that we’re endangered by too much freedom. At the same time, America’s federal government has worked so well because of its brilliantly established checks and balances. What are they other than a way to curtail the “freedom” of elites’ greed, of mass unchecked resentments, of ideologues’ narrow isolating convictions?

Sullivan, of course, expresses joyous wonder that things have not already flown apart. He’s an interesting Republican: learned, gay, deeply religious, temperamentally conservative. Maybe it’s such an interesting essay because he’s trying to resolve so many inherently irresolvable things. And yet, its worth continually circles back to whether you can accept the statement he cites with the lightest caution from Plato’s Republic:

Democracies end when they are too democratic.

Have Trump and Bernie Sanders, whom Sullivan calls a similar demagogue, arisen to relive us at last from “democracy’s endless choices and insecurities”? That fear seems the underlying force uniting many Democrats and Republicans at this hour. The inflamed mob scares everyone.

Sullivan is right to examine why America’s electorate, if given a sudden economic downturn or a devastating domestic terrorist attack, could usher Trump into office. What would that be like? Consider Vladimir Putin, a thuggish leader Trump admires. God save our republic.

The post Writers on our political rhubarb appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

May 3, 2016

Annie Dillard surfaces

[President Obama awards a National Humanities Medal to Dillard in 2015]

Saint Annie grants a rare interview & reveals why she retired

New Yorker editor David Remnick has scored a coup, or at least a scoop, by interviewing the reclusive Annie Dillard for the magazine’s radio show. The occasion is Dillard’s retrospective essay collection, The Abundance: Narrative Essays Old and New. The book has spurred a flurry of speculation in the literary world about Dillard’s retirement, notably a strained essay, “Where Have You Gone, Annie Dillard?”, by William Deresiewicz in The Atlantic positing that Dillard somehow boxed herself in with her mystical interests.

So the key question Remnick asked was why did she retire from writing, some years ago now, to spend her days painting? She wrote by hand, she told him, and one day couldn’t remember where she was going with the start of a promising sentence she’d left the previous day on her legal pad. Short-term memory loss, in short, is her explanation for her retirement from writing. Dillard, now 71, does not sound, in this rare interview, to be a victim of Alzheimer’s, as has been rumored. She sounds sharp as a double-headed tack.

Of her books, she prizes most my favorite: For the Time Being (reviewed). She marvels, “Writers adore that book,” but then she’s always been a writer’s writer. In it, she said, she bites off a big chunk of her preoccupation with human existence. All I can say is it’s in my pantheon as one of the greatest books I’ve ever read. Remnick questions her about her spooky essay “Total Eclipse,” which she reads from and analyzes. She explains her goal was to invoke the experience of the eclipse in readers. But the challenge was keeping them reading—dense description of the long event and Dillard’s reaction would lose them, she felt. Hence her decision to keep returning to the eclipse, repeating, each time at a deeper level, her experience of the power and primeval horror of the light’s loss.

The Abundance at first strikes me as redundant, the “new” in the subtitle a marketing ploy, but then again it collects stray essays like “Total Eclipse,” which appeared as part of Teaching a Stone to Talk but has taken on a life of its own in collections and in pdf form in classrooms. A nice surprise heading the collection is the eloquent Introduction by Geoff Dyer—tied with Anthony Lane as my favorite sardonic Brit—author of the hilarious Out of Sheer Rage: Wrestling with D.H. Lawrence and the delightful essay collection Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It.

In his introductory essay, which appeared on Lithub, clearly the postmodern appeal of Dillard’s genre-defying nonfiction drew Dyer to Dillard:

Genre-resistant non-fiction may be a recognized genre these days but Dillard awoke to its possibilities—and attendant difficulties—back in the early 1970s when she was writing what became Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. “After all,” she noted in a journal, “we’ve had the nonfiction novel—it’s time for the novelized book of nonfiction.” Easier said than done, of course. As she puts it in The Writing Life, “Writing every book, the writer must solve two problems: Can it be done? And, Can I do it?” . . .

“What kind of book is this?” she asked herself of Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, a question that will continue to be asked for as long as the book is read. We read it, in part, to find the answer and, after we have read it—this is the great thing—are still not sure.

[Dyer: tart Brit a total fanboy.]

Dyer says D.H. Lawrence and Rebecca West were two of the writers who prepared him for Dillard. Though Dyer and Dillard have both written novels, it was her nonfiction that galvanized him. She showed him how a writer can go deep in her work, he writes, “by stripping it of a lot of the clutter—the furniture of character—required by the novel but the physicality of story-telling has to remain strong, has to be doubly strong, in fact.”Dyer’s authorial persona is of a slacker, a stoner, a failure, but that’s in comedic tension with his own work, which belies that, and the Oxford man leaves evidence, in stray lines, of his own spiritual interests. He may overstate when he calls Dillard a comedic writer, suffused by the “comedy of rapture.” She’s got a goofy sense of humor, no doubt—Dyer calls her “pretty much a fruitcake”—but in my reading she takes her altered mental states seriously or at least hungers for them.

He’s on firmer ground when he makes connection with her as a nature writer—he is too, covertly. In the midst of a riff during one of his aimless comedic journeys he sometimes meditates upon or describes nature in the most arresting way.

So no wonder—and so neat—to discover he too is a Dillard fanboy.

[Found at Write to Done: http://writetodone.com/inspiration-fo...]

The post Annie Dillard surfaces appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

Annie Dillard emerges

[President Obama awards a National Humanities Medal to Dillard in 2015]

Saint Annie grants a rare interview & reveals why she retired

![[Mystical, tough, genre-defying]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1462417094i/18994465.jpg)

[Mystical, tough, genre-defying]

New Yorker editor David Remnick has scored a coup, or at least a scoop, by interviewing the reclusive Annie Dillard for the magazine’s radio show. The occasion is Dillard’s retrospective essay collection, The Abundance: Narrative Essays Old and New. The book has spurred a flurry of speculation in the literary world about Dillard’s retirement, notably a strained essay, “Where Have You Gone, Annie Dillard?”, by William Deresiewicz in The Atlantic positing that Dillard somehow boxed herself in with her mystical interests.So the key question Remnick asked was why did she retire from writing, some years ago now, to spend her days painting? She wrote by hand, she told him, and one day couldn’t remember where she was going with the start of a promising sentence she’d left the previous day on her legal pad. Short-term memory loss, in short, is her explanation for her retirement from writing. Dillard, now 71, does not sound, in this rare interview, to be a victim of Alzheimer’s, as has been rumored. She sounds sharp as a double-headed tack.

Of her books, she prizes most my favorite: For the Time Being (reviewed). She marvels, “Writers adore that book,” but then she’s always been a writer’s writer. In it, she said, she bites off a big chunk of her preoccupation with human existence. All I can say is it’s in my pantheon as one of the greatest books I’ve ever read. Remnick questions her about her spooky essay “Total Eclipse,” which she reads from and analyzes. She explains her goal was to invoke the experience of the eclipse in readers. But the challenge was keeping them reading—dense description of the long event and Dillard’s reaction would lose them, she felt. Hence her decision to keep returning to the eclipse, repeating, each time at a deeper level, her experience of the power and primeval horror of the light’s loss.

The Abundance at first strikes me as redundant, the “new” in the subtitle a marketing ploy, but then again it collects stray essays like “Total Eclipse,” which appeared as part of Teaching a Stone to Talk but has taken on a life of its own in collections and in pdf form in classrooms. A nice surprise heading the collection is the eloquent Introduction by Geoff Dyer—tied with Anthony Lane as my favorite sardonic Brit—author of the hilarious Out of Sheer Rage: Wrestling with D.H. Lawrence and the delightful essay collection Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It.

In his introductory essay, which appeared on Lithub, clearly the postmodern appeal of Dillard’s genre-defying nonfiction drew Dyer to Dillard:

Genre-resistant non-fiction may be a recognized genre these days but Dillard awoke to its possibilities—and attendant difficulties—back in the early 1970s when she was writing what became Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. “After all,” she noted in a journal, “we’ve had the nonfiction novel—it’s time for the novelized book of nonfiction.” Easier said than done, of course. As she puts it in The Writing Life, “Writing every book, the writer must solve two problems: Can it be done? And, Can I do it?” . . .

“What kind of book is this?” she asked herself of Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, a question that will continue to be asked for as long as the book is read. We read it, in part, to find the answer and, after we have read it—this is the great thing—are still not sure.

[Dyer: tart Brit a total fanboy.]

Dyer says D.H. Lawrence and Rebecca West were two of the writers who prepared him for Dillard. Though Dyer and Dillard have both written novels, it was her nonfiction that galvanized him. She showed him how a writer can go deep in her work, he writes, “by stripping it of a lot of the clutter—the furniture of character—required by the novel but the physicality of story-telling has to remain strong, has to be doubly strong, in fact.”Dyer’s authorial persona is of a slacker, a stoner, a failure, but that’s in comedic tension with his own work, which belies that, and the Oxford man leaves evidence, in stray lines, of his own spiritual interests. He may overstate when he calls Dillard a comedic writer, suffused by the “comedy of rapture.” She’s got a goofy sense of humor, no doubt—Dyer calls her “pretty much a fruitcake”—but in my reading she takes her altered mental states seriously or at least hungers for them.

He’s on firmer ground when he makes connection with her as a nature writer—he is too, covertly. In the midst of a riff during one of his aimless comedic journeys he sometimes meditates upon or describes nature in the most arresting way.

So no wonder—and so neat—to discover he too is a Dillard fanboy.

The post Annie Dillard emerges appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

April 22, 2016

Doubt confronts faith

Trials of the Monkey: An Accidental Memoir by Matthew Chapman. Picador, 367 pp.

Some of us miss the personal dimension in nonfiction that deals relentlessly with its main subject—who is writing this thing and why? Others find memoir claustrophobic—where’s the larger world, other people, everyday life? The practice of telling both stories in the same work is ancient, but such books were a harder sell for all concerned until publishers could slap “memoir” on quirky personal narratives. Labels can matter. In an interesting talk at the 2013 River Teeth Nonfiction Conference, writer Michelle Herman called “stealth memoir” a bogus genre she made up. Like calling a borrowed structure a “hermit crab,” however, stealth memoir is a discerning and useful phrase. It may be helping shape a subgenre by focusing and encouraging writers to include themselves while inquiring into a larger external subject.

Three of my favorite stealth memoirs are Out of Sheer Rage: Wrestling with D.H. Lawrence by Geoff Dyer; Works Cited: An Alphabetical Odyssey of Mayhem and Misbehavior (reviewed) by Brandon Schrand; and The Pat Boone Fan Club: My Life as a White Anglo-Saxon Jew by Sue William Silverman.

My latest enjoyable discovery in this realm is Matthew Chapman’s Trials of the Monkey: An Accidental Memoir. Funny and personally poignant, it’s also an interestingly reported foray into the Bible Belt by a doubting English descendant of Charles Darwin. I admire the way Chapman writes honestly about himself even as he laughs at others, especially evangelical Bible thumpers, but always with a compassionate wink. He both discerns and forgives others’ crutches and foibles, having racked up so many disasters himself. He talks at length, often in brave encounters, with people who are stunningly different from himself. These folks range from scary barflies to sweet, complexly human, true-believing students from a fundamentalist college.

[Matthew Chapman.]

Though the surface story concerns Chapman’s attempt to cover the reenactment of the Scopes Monkey Trial in Dayton, Tennessee, it’s ultimately as much about Chapman’s perspective, from weary middle age, on his own delinquent youth—which by work, willpower, and talent he redeemed. Chapman, now based in New York, found success as a Hollywood screenwriter and director. But he’s the monkey of his book’s title—a workaholic, alcoholic fellow who adores his daughter and loves his wife but whose own life is rather messy.His memoir is long and at times dense, but along with Chapman’s appealing voice and compelling stories it offers a refreshing structure. It’s braided, alternating between Chapman’s road trips into the American south and tales of his chaotic boarding school days and dreadful early jobs. He’s haunted by his mother, a depressive who smoked and drank herself to death in the Darwin family tradition.

Chapman cannot accept facile literalist religion, but I admired the fair hearings he gave such pilgrims. He made an impressive immersion journalist. And I found true and moving his yearning for spiritual solace.

The post Doubt confronts faith appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

Facticity crashes into faith

The Trials of the Monkey: An Accidental Memoir by Matthew Chapman. Picador, 367 pp.

Some of us miss the personal dimension in nonfiction that deals relentlessly with its main subject—who is writing this thing and why? Others find memoir claustrophobic—where’s the larger world, other people, everyday life? The practice of telling both stories in the same work is ancient, but such books were a harder sell for all concerned until publishers could slap “memoir” on quirky personal narratives. Labels can matter. In an interesting talk at the 2013 River Teeth Nonfiction Conference, writer Michelle Herman called “stealth memoir” a bogus genre she made up. Like calling a borrowed structure a “hermit crab,” however, stealth memoir is a discerning and useful phrase. It may be helping shape a subgenre by focusing and encouraging writers to include themselves while inquiring into a larger external subject.

Three of my favorite stealth memoirs are Out of Sheer Rage: Wrestling with D.H. Lawrence by Geoff Dyer; Works Cited: An Alphabetical Odyssey of Mayhem and Misbehavior (reviewed) by Brandon Schrand; and The Pat Boone Fan Club: My Life as a White Anglo-Saxon Jew by Sue William Silverman.

My latest enjoyable discovery in this realm is Matthew Chapman’s Trials of the Monkey: An Accidental Memoir. Funny and personally poignant, it’s also an interestingly reported foray into the Bible Belt by a doubting English descendant of Charles Darwin. I admire the way Chapman writes honestly about himself even as he skewers others, especially Bible thumpers, but always with a compassionate wink. He both discerns and forgives others’ crutches and foibles, having racked up so many disasters himself. He talks at length, often in brave encounters, with people who are stunningly different from himself. These folks range from scary barflies to sweet true-believing students from a fundamentalist college.

[Matthew Chapman.]

Though the surface story concerns Chapman’s attempt to cover the reenactment of the Scopes Monkey Trial in Dayton, Tennessee, it’s ultimately as much about Chapman’s perspective, from weary middle age, on his own oversexed, misspent youth—which by work, willpower, and talent he redeemed. Chapman, now based in New York, found success as a Hollywood screenwriter and director. His memoir is long and at times dense, but along with Chapman’s appealing voice and compelling stories it offers a refreshing structure. It’s braided, alternating between Chapman’s road trips into the American south and tales of his chaotic boarding school days and dreadful early jobs. He’s haunted by his mother, a depressive who smoked and drank herself to death in the Darwin family tradition.Chapman cannot accept facile literalist religion, but I admired the fair hearings he gave such pilgrims. And I found true and moving his yearning for spiritual solace.

The post Facticity crashes into faith appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

April 13, 2016

‘We need memoir’

Eventually it occurred to me that life is more than an ending. That despite the trauma of my son’s loss and everything leading up to it, there IS something more. I will always be a dedicated student of society looking for the essential story, the universal message: a path with less suffering, deeper awareness.—D.A. Hickman, The Silence of Morning

I met D. A. “Daisy” Hickman, a poet and prose author, through her blog focused on writing, memoir, and spirituality, SunnyRoomStudio, a “creative, sunny space for kindred spirits.” The author of a trade-published book on the American prairie, she founded Capturing Morning Press, which reissued that book and has recently published The Silence of Morning: A Memoir of Time Undone. This new memoir tells the story of her son, who struggled with substance abuse and took his own life, and recounts her grief and healing.

When I read The Silence of Morning, I was struck by Hickman’s response to her grief, which she calls “the world’s teacher in disguise.” Such a phrase is distillate. It comes from her wide perspective, which was slowly earned in the magnitude of her suffering and through her enlightened actions: reading widely and reflecting on society, herself, and her son, Matthew. These seem unusual acts, perhaps because they’re simply private. Or maybe it’s simply that a serious writer took time to convey them.

Anyone who grieves or is touched by death or illness cannot fail to notice the world’s steady preference: mindlessness. And America seems to want suffering out of sight, its impatience palpable with the sick and dying. Amidst Hickman’s inquiry into this indifference, she gives us glimpses of Matthew—the boy with the fishing pole and paper route, the struggling young man devouring books while incarcerated, the hopeful farm hand in jeans and scuffed boots seeking a fresh start.

Hickman holds a master’s degree in sociology from Iowa State University, and earned her bachelor’s degree in legal studies at Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri. A member of the Academy of American Poets and South Dakota State Poetry Society, she’s at work on her first poetry collection. Previously, she worked with nonprofits in the areas of organizational development, fund development, management, and strategic planning.

She answered some questions for Draft No. 4.

[D.A. Hickman]

• You have long been a spiritual writer and blogger. Someone concerned with spiritual insight and discipline. Are there spiritual traditions that you find more useful than others in helping those grieving?Interesting question. In the introduction to my memoir, I delved into some basic philosophies around the Zen tradition but, ultimately, I explore many spiritual threads throughout the book. The key, in any challenging life situation, is to look for spiritual insight in any and all directions. Something will resonate. But too often we are locked in old beliefs and values, so some teachings are overlooked or disregarded without exploration. From the book: “We don’t know what we need to know until we know it; we don’t know what is missing until we find it.”

The more open we can stay to various teachings, the greater the odds of actualizing meaningful growth and finding inspiration. And, eventually, when a commitment to discovery is made and sustained, prior traditions can be released, because we find our own way, create our own discipline or spiritual path. Spiritual actualization is difficult to describe but, for me, it has felt like learning to live from an innate sense of “knowing” that is beyond intellectual understanding, lived experience, and anything I could have imagined beforehand.

• I’ll ask the expected question that people often put to memoirists. Did writing about this painful matter “help you”? That is, aid you in processing loss or being able better to deal with it?

Yes, a common question, an even more predictable assumption. Curiously, there is the misconception that writing memoir is all about authors—how we “survive” a riveting sadness. While this could be true for some, from my perspective, a memoir is a gift of self . . . more than anything. Suffering is best met by reaching out one way or another, and that implies an acceptance of the inherently painful aspects of the mortal journey, while remembering everyone is suffering . . . one way or another.

Extending empathy and compassion via memoir is also a good way to explore the vagaries of the human condition, but I don’t really buy into the “healing” notion that is found in a great deal of the literature. Overworked, generic, increasingly meaningless.

“The notion, in fact,” I wrote, “is somewhat misleading, suggesting a linear path, a terminal destination created by a world dominated by time, and its heavy, misdirected expectations.”

Also, from the Afterword: “When looking at the big picture—the yin, the yang, of things—grief and loss are, more precisely, about finding the courage and the determination to come to a more complete understanding of life in its glorious yet, utterly baffling, entirety.”

![[Matt Hickman]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1460631814i/18767662.jpg)

[Daisy Hickman’s son, Matt McCartney]

McCartney• What did you learn about grief in looking back on and portraying it? Is that knowledge a gift you hope to give with the book? Or do you feel that simply being open about grieving in our death-denying culture is itself the gift?

If we are to better understand the reality of the human condition . . . we need memoir. Breaking news headlines, quick-and-fast snippets from popularized media outlets and various social networks, the artificial nature of our celebrity culture, and the long-term tendency of a society to reject what isn’t trendy, fun, or familiar, too often produce useless streams of “information” geared to mainstream consumption.

None of this takes us inside the realities of profound challenge. None of this helps us understand human suffering: widespread and, seemingly, increasing.

I hear about another youthful suicide nearly every week. And yet we don’t look closely at the collective energy behind it. We feel safer focusing on individuals, their troubles or problems, to the exclusion of the insidious impact of our seriously disturbed global environment . . . the human condition that we all are born into. Ultimately, individuals are merely a reflection of the world around us, nearby or featured on the nightly news.So in my memoir I made an effort to highlight the sociology of grief, loss, addiction (we are a world addicted to everything and anything), and suicide. Addicts did not create addiction, for instance, nor can they cure it, singlehandedly. That will take systemic change that flows from the very origins of our species, from the fabric of society and societies.

It seems both aspects of your question are true, Richard. Being open about the human condition—my son’s death from suicide in the riveting context of daily life—and, yes, the hard-earned knowledge that somehow emerged from those years, are both relevant to the national conversation around these daunting and commonplace issues. A staid conversation, I might add, that is largely unproductive.

But my memoir also offers awareness and compassion to anyone contending more immediately, more directly, with loss, grief, and the deeper mysteries of existence. I wrote, for instance, about my unexpected confrontation with a vast unknown. The trepidation I felt, the longing for understanding.

• Speaking of portraying, after learning of your son’s death you are reeling but must travel to Missouri for the funeral and burial. You delay, for some time, many of the details around that experience. This seems to embody your book’s larger point about the “conditioned mind,” which grief derails. Could you discuss your memoir’s structure, the risk you took in thwarting readers’ narrative expectations?

We are all controlled by time—calendars, clocks, expectations around certain dates, deadlines—more than we realize. One of my personal revelations in the book was learning to look through the veil of time for a more timeless dimension that is often overlooked during this curious mortal race to the grave. Time seems to spin a limiting, often painful, web around and in our lives, so when it came to book structure, I wanted to downplay this dynamic. Instead, I sought the deeper story, one that had nothing to do with “what happened when” or the chronological impact of grief.

For one thing, grief itself is a nonlinear experience; it defies all “rules” of time and space. In many ways, grief is a curious door to all things beyond time, and once opened, cannot easily be closed. It is also an invitation—powerful, ubiquitous, almost obvious—to explore life without traditional expectations of any kind. Too often we are locked in sequential thought patterns; too often we fail to see the deeper story, which is always there when we let go of our cookie-cutter conditioning (family, friends, society) and seek liberation from suffering.

I hope the narrative challenges readers (we all need a challenge!), because it is a memoir that only truly reveals itself on the last page. I also wrote, intentionally, a “slow read” . . . why?

Because we rush around with time as our merciless master and miss the nuance and grace in our own lives. A book about so many weighty topics needed ample artistic space to fully evolve and, hopefully, readers will sense this at the start . . . instead of pushing themselves to race through it in a few days.

It’s not a thriller.

This is a life and death story that belongs to everyone.

We are on the same path, the same journey, and readers who take this book and try to see how aspects of it pertain to their own lives will value the slower pace, the deeper look, the universal message. In my wildest dreams, some readers may even want to read it more than once!

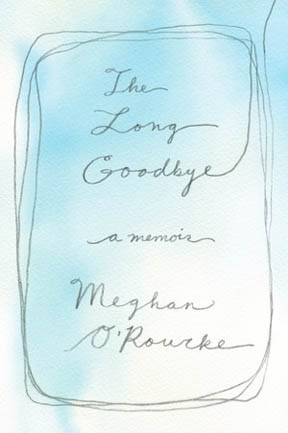

[Hickman’s first book.]

• The Silence of Morning is self-published under your authorial imprint (Capturing Morning Press), which makes you part of the boom and renaissance in publishing. You also published with a trade press, however, with your nonfiction book about the power of place, Where the Heart Resides: Timeless Wisdom of the American Prairie (William Morrow), updating and editing that book in 2014 for a 15th anniversary edition newly titled Always Returning: The Wisdom of Place. Could you discuss the benefits, the tradeoffs of each path?Author-publishing is something I gravitated to for many reasons. It seems tremendous time and energy is wasted by writers seeking traditional publishing—too often a political, inherently biased process beset by monetary values and marketing priorities. Also an extremely slow and tedious process, this path can easily interfere with the creative quality of literature and the original inspiration of the artist/writer. In the end, it is a system of power and control that largely generates “more of the same.” Yes, there are exceptions to all of this, but it is my impression that our “celebrity culture” is increasingly dominating the book industry. Name recognition equals instant (and easy) book marketing, right?

On a very pragmatic level, it behooves authors to retain the rights to their work. Companies of all kinds, including traditional publishing houses, merge and shift nearly overnight, and a book can be lost in the shuffle. Also, in working closely with a book designer (in my case, 1106 Design, Phoenix), I participate in the process from start to finish. I choose the cover art (worked with the incredible Missouri artist, Paul C. Jackson) in this regard, and then react to various cover designs, until we find just the right image and message. The same process happens for the interior design. Something unique can be born this way; my books don’t have to look like every other book out there. Lots of work but, overall, fun and rewarding.

Working with William Morrow was a tremendous learning experience (how not to do it, as much as how to do it), but the worlds of publishing and technology are in serious flux—the latest promising frontier quickly outdated. So why would I want to be the last person through the golden gates of innovation? The learning curve was worth it. Literary perfection has never been my goal (life is too short for that), but I have felt compelled to delve into the more mysterious aspects of life.

When I wrote The Silence of Morning, I wanted to respect the divine proclivities of grief itself. I also felt deeply committed to sharing my son’s story in a way that honored his journey, and mine. A commercial publisher may not have agreed with my priorities, so I simply trusted my intuition . . . went from there.

In the end, as I shared on the book’s back cover: I will always be a dedicated student of society looking for the essential story, the universal message: a path with less suffering, deeper awareness.

[Hickman’s self-reissue.]

Thank you so much, Richard, for the opportunity to share a few thoughts about how tragedy and spiritual curiosity pushed me to evolve in unexpected ways. Now I better understand the curious twining of life and loss. How we all benefit when we are roused from our sleep. At the start of my memoir, I wondered what was left to be said after a sudden death—when everyone departs and you are frightened and alone like never before. It turned out that a great deal was left to be said; I discovered that as each chapter began to take shape.

Also meaningful in this context are the poetic words of Tagore, Stray Birds: “Your voice, my friend, wanders in my heart like the muffled sound of the sea among listening pines.” And, yes, Matthew’s voice, silenced now for some nine years, still rings in my soul like a distant bell—one that chimes from a place that feels known, yet unseen.

[For author updates or to subscribe to Hickman’s blog, visit her website or follow SunnyRoomStudio on Facebook and Twitter @dhsunwriter.]

The post ‘We need memoir’ appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

April 6, 2016

Reading as writers

[Sunrise over Melbourne Beach, Florida. March 2016.]

Teaching shorter versions of Baldwin’s & Lethem’s narrative essays.

Gay Talese’s essay in the current New Yorker, “The Voyeur’s Motel,” makes me wish I were still teaching journalism. It’s about a man who bought a motel near Denver in the late 1960s so he could spy on guests, which he did for decades. It’s creepy and horrifying, his behavior and Talese’s tale, but you can’t look away. Or stop thinking about the man and what he saw with his wife, including their aim, sex, but also lots of disquieting behavior, including a murder. Talese’s pleasurable but ethically problematic account is over 30 pages. Yet students would gobble it up like candy.

Reading this page-turner narrative essay coincided with my recent brooding about reading. This involves mine and the reading I assign to students. Most people seem to read largely to seek pleasure. Do we grow by tackling more difficult work? Probably—but so what, for casual readers? For students, must I stick with something that’s genius but to them not very enjoyable? Since I read largely as a writer now, I’ve agreed to the harder path, but most students haven’t.

After my share of classroom disasters, I’ve learned to meet students where they are. Which partly means assigning books, essays, and stories that they’ll at least tolerate . I also must admire the works, of course. Tobias Wolff’s This Boy’s Life is genius and so is Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory. Which do you think a class of eighteen year olds would actually read? Most undergraduates, even many writing majors, cannot yet appreciate certain works.

For one thing, they aren’t yet old enough to identify readily with older folks and certain situations. For another, they lack endurance, especially for dense exposition.

///

[Native Son: Baldwin was only 31.]

Teaching senior citizens this year in continuing studies classes, I expected a big difference. Indeed they could identify with a wider range of ages. But they were beginning writers, too, and they balked at demanding nonfiction. Such as James Baldwin’s classic essay “Notes of a Native Son,” which depicts his and his father’s cruel suffering caused by racism. These older students seemed to respect it, but most of them didn’t seem to enjoy it. Baldwin’s prose, to me, is delicious, his story compelling, his ideas profound. But “Notes of a Native Son” is dense, with long, unbroken expository paragraphs. And only two space breaks, which demarcate the essay’s numbered sections, emphasizing its classical three-act structure. Just two slender spaces where readers can regroup.From now on, for beginning writers—and probably for everyone except graduate students—I’ll probably assign the shorter version of “Native Son” that first appeared as “Me and My House” in Harper’s Magazine (it is available to subscribers as a pdf download; nonsubscribers must purchase the entire issue, on Harper’s website, for $6.99). This publication came in November 1955, when Baldwin was 31, and it’s a page and a half shorter than what appeared that same year in Baldwin’s collection Notes of a Native Son as its title essay. Whether Baldwin cut it himself to fit the magazine’s space, or whether an editor pared down his essay, it’s a brilliant editing job.

Probably worth studying in their own right, the truncated essay’s deletions are oddly unnoticeable—a few orotund clauses clipped on this page, an elaborating sentence shaved on the next. You’re aware only of the essay feeling crisper and reading more quickly. The editor, or Baldwin, also added seven space breaks within the essay’s numbered sections—three in the long first part, one in the second, and three in the third—where readers can rest and reflect.

The essay’s first cut is one of its most severe. Here’s the original paragraph about Baldwin’s father:

He had been born in New Orleans and had been a quiet young man there during the time that Louis Armstrong, a boy, was running errands for the dives and honky-tonks of what was always presented to me as one of the most wicked of cities. My father never mentioned Louis Armstrong, except to forbid us to play his records, but there was a picture of him on our wall for a long time. One of my father’s strong-willed female relatives had placed it there and forbade my father to take it down. He never did, but he eventually maneuvered her out of the house and when, some years later, she was in trouble and near death, he refused to do anything to help her.

Here’s the shortened version, which moves quickly away from the Louis Armstrong digression into the famous following passage in which Baldwin analyzes his father’s psyche:

He had been born in New Orleans and had been a [quiet] young man there during the time that Louis Armstrong, a boy, was running errands for the dives and hanky-tanks of what was always presented to me as one of the most wicked of cities. He was, I think, very handsome. Handsome, proud, and ingrown, “like a toenail,” somebody said. But he looked to me, as I grew older, like pictures I had seen of African tribal chieftains: he really should have been naked, with warpaint on and barbaric mementos, standing among spears. He could be chilling in the pulpit and indescribably cruel in his personal life and he was certainly the most bitter man I have ever met; yet it must be said that there was something else buried in him, which lent him his tremendous power and, even, a rather crushing charm. It had something to do with his blackness, I think—he was very black—and his beauty, and the fact that he knew that he was black but did not know he was beautiful.

Since this represents one of the few sustained cuts, it’s useful for debating whether the shorter version is better or lesser. To me, Baldwin elsewhere sufficiently depicts his father’s prickly nature and vindictiveness. A writer whose aesthetic judgment I usually respect, however, gave me grief when I first pondered teaching the Harper’s version. Granted, “Notes of a Native Son” is iconic. I call it America’s greatest essay because it’s about America’s great topic, race, and because of its memoiristic and structural brilliance.

Most people, like my writer friend, aren’t aware that “Notes of a Native Son” initially appeared in slightly more slender form. I say ”Me and My House” is better or lesser than the canonical version depending on its audience. I’d rather have students read it than zone out, or not be exposed at all, to Baldwin’s ideas, artistry, and moving story.

///

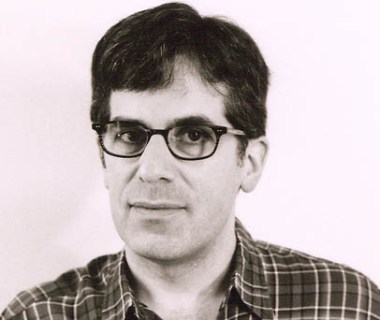

[Jonathan Lethem.]

What finally cemented my conviction was my experience this semester teaching another masterpiece, Jonathan Lethem’s thrilling postmodern essay about influence and loss, “The Beards.” It’s from his 2005 collection The Disappointment Artist. I’ve often taught Lethem’s in conjunction with “Notes of a Native Son,” which is how I first studied them myself, in an MFA seminar at Goucher College taught by Leslie Rubinkowski. Though both essays are very long, they helpfully demonstrate strikingly different approaches to writing about a parent’s death.Lethem’s account of his geeky, art-saturated adolescence occurs during and in the wake of his mother’s early death, from cancer, when he was 14. It’s a heavily segmented essay, with each segment dated according to his mother’s status (stage of illness or length of time dead). His disorientation, devastation, and ongoing sense of loss are mirrored in the essay’s disjointed structure, most obviously by the fact that the segments appear in non-chronological order. His grief from her death is ongoing, ever-present, endless.

As depicted in “The Beards,” Lethem’s intense saturation in cerebral rock music, foreign films, and countless classic and cult novels is awe-inspiring. Along with being a portrait of the sort of obsessions that can forge an artist, Lethem’s art-absorption is inseparable from his point about the particular nature of his loss. His mother, who gave young Jonathan a typewriter shortly before her death, emerges in the writer’s cool, elliptical way as loving and artistic. She was and remains his muse and his subject.

But Lethem’s arts analysis in “The Beards” also forms a hurdle for novice readers. My continuing studies students bounced right off it. “What was that? All that stuff about music?” asked a talented novice writer, a fan of segmentation, who’d stopped reading it early on. Thus I recalled that “The Beards” tends to exhaust and bewilder my undergraduates as well. For one thing, it challenges almost anyone’s own artistic depth. For another, it’s difficult for most readers to absorb stories about art they’re utterly unfamiliar with. I know it’s the teacher’s job to expose students to classics and help them through them. In practice, and partly because of time constraints, I think you must pick your battles.

Imagine my surprise when, after my latest disappointing performance in teaching “The Beards,” I went looking and found the version that the New Yorker originally published, in 2005, as an excerpt from The Disappointment Artist. Wow—way shorter. So far, I haven’t been able to quantify the full difference, but the magazine version includes 10 segments over seven and a half double-column pages while the book’s version features 11 segments over some 24 book-pages. Guess which version I’ll assign to freshmen composition students and novice writers? The other I’ll reserve for more experienced and ambitious readers and writers.

How do you get good at judging wine? You drink lots of wine! How do you develop your taste as a reader? You read a lot! You challenge yourself. But look, everyone starts with training wheels. And sometimes everyone needs to dismount into a warm bath. Even a teacher.

Sunrise near Frederick, Maryland. Easter 2016.]

The post Reading as writers appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

March 31, 2016

Living with racism

Citizen: An American Lyric by Claudia Rankine. Graywolf Press, 160 pp.

How well I remember asking my friend Mike a stupid question. We were young reporters together. But there our similarity ended, for Mike’s skin was brown. He was the only person of color who worked at that newspaper. In fact, the entire town lacked racial diversity. One day I got marveling at Mike’s situation, imaging myself surrounded by and working only with members of another race.

“That’s got to be so weird,” I said. “Does it feel strange, Mike?”

I expected props for seeing his plight, but Mike gave me the most withering look I’d ever received. I was surprised, too, because at parties he mocked racial stereotypes by bringing fried chicken or lugging in watermelons. I was trying to be sensitive and insightful, but I put him on the spot with my cluelessness.

I thought of Mike reading Citizen: An American Lyric, Claudia Rankine’s short book, a long segmented essay-poem, on her experience as a person of color making her way in realms still mostly white. Citizen, Winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award in Poetry, proves that great literature doesn’t have to be hard reading. Except, in this case, emotionally. Rankine challenges white readers as she conveys the cognitive dissonance she lives with as an African American. For example, when her white friends slip and reveal their unconscious prejudice toward her or another member of her race. Or when she witnesses the barriers faced by tennis star Serena Williams. Or when she hears of a black person harmed by cops. Consider, when even people with white skin feel wary in dealings with police, what a cruiser’s appearance must feel like to black people.

[Claudia Rankine. Photo by John Lucas.]

In this politicized moment, I couldn’t help but think, as well, of America’s public schools, which get attacked but remain crucial in fostering a happier diversity. If a person of color makes it to the corporate ladder, executives try to ensure her or his climb, realizing as a matter of common-sense policy that everyone who excels should get a shot at middle- or upper-middle-class success. Given that, I cannot understand many Republicans’ consistent antipathy toward public schools. On the one hand, they steadily undermine public schools, minorities’ proven path to success; on the other hand, many business leaders, probably mostly Republicans, reach out a hand to those few who somehow claw their way inside America’s skyscrapers.Rankine has white friends, among them some who’ve trespassed, but is at the cutting edge herself—still—of the racial integration of America’s mainstream. Rankine knows the lie of racism and the truth of community. She knows the falsehood of superficial differences and the strength of diversity. She shows this in Citizen: An American Lyric through her experiences. Rankine’s uneasy emotional reality is conveyed by a wise, wry, and stoic persona. That’s quite an accomplishment in the face of human idiocy and structural injustice.

The post Living with racism appeared first on Richard Gilbert.