Richard Gilbert's Blog, page 6

March 23, 2016

Thinking and feeling

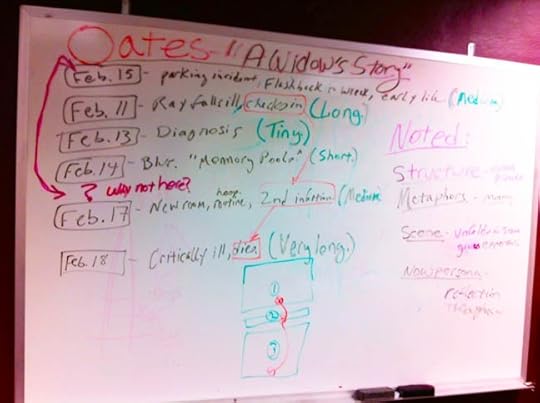

[My class whiteboard outlines Joyce Carol Oates’s essay “A Widow’s Story.”]

Messy essays & eternal truths: the work under writing’s surface.

Trust yourself, you know more than you think you do.—Benjamin Spock

1. Writing is thinking

“Writing is thinking! Writing is feeling!” enthused one of my students near the end of Spring term. This was at Virginia Tech, where I have been teaching in the Lifelong Learning Institute this academic year.

I’ll call her Helen. At the start of class, Helen had seemed confident of her thinking ability—she’d spent a distinguished career reasoning and writing. But she’d seemed not so sure she could emote for readers. Or ask them for an emotional response, let alone provoke it. Helen’s comment took me back to 2005, when I started writing my memoir. I enjoyed building that narrative, but it was work. Writing is concentrated thought, I marveled. That’s why it’s hard. Most of us seldom think about one thing for hours on end. But there’s a huge compensation, I came to see.

“I think what makes writing addictive is that it doesn’t just capture thought, it creates thought,” I told my class one afternoon. “You write a sentence, make a claim. And then you write another. And then you look at those two sentences and write down what you didn’t know you knew. Because you didn’t. Writing doesn’t only capture thought, it creates it.”

Now I didn’t pause to credit the sources who helped me describe this quality. So here I will. Surely writing theorist Peter Elbow influenced my thinking (See my post “Writing’s ‘dangerous method.’ ”) But Donald M. Murray, who nails writing’s rewards in The Craft of Revision (Fifth Edition), lent me the words:

Writing is not reported thought. Writing is more important than that. It is thinking itself. . . . And it is fun because I keep finding I know more than I expected, feel more than I expected, remember more, and have a stronger opinion than I expected. [See “Revise, then polish.”]

This is what I found, and I think what Helen experienced.

2. Writing is feeling

[1972: Joyce Carol Oates & Raymond Smith. @BernardGotfryd.]

Maybe Helen was thinking of my statement: “Art is made from emotion, is about emotion, and asks for an emotional response.”What does that mean? Was I going to ask her to emote all over the page? That wasn’t her style!

Well, on that score, everyone’s mileage varies. As a writing teacher once told me, “No one tells everything.” Indeed they don’t. As in life, we must prepare a face to meet the faces that we meet. And our mask is influenced by temperament and mood and the nature of the piece.

Helen wrote about her early years, a young Yankee professional woman who found herself starting out in the Appalachian south. She encountered a gracious but sexist, patronizing, and clannish culture. What she discovered in writing a memoir essay in my class was what she hadn’t before consciously articulated: after decades of becoming localized, as a success, she sensed yet another layer of exclusion. A deeper boundary. She hadn’t glimpsed this wall before, and now was just starting to try to articulate its nature.

What “writing is feeling” meant to Helen, I think—and what maybe it does mean, after all—embodies such discovery. Not writing emotionally, as such. But seeing clearly how you felt and conveying it. How did you feel then? How do you feel now?

Don Murray again:

The writer who writes for revision does not wait for a final draft but works through a series of discovery, development, and clarification drafts until a significant meaning is found and made clear to the reader.

3. Writing is craft

The shortest essay I ever wrote, maybe the shortest essay anyone has ever written, was “Little Essay on Form.” It went like this: “We build the corral as we reinvent the horse.” Later, I added: “Craft is what nails the gate, helps formalize the space, and keeps the horse shit out of the picture. It leaves us with the necessary.” —Stephen Dunn in his Georgia Review essay, “Forms and Structures.”

After I showed my memoir class how James Baldwin punctuated his great essay “Notes of a Native Son,” Helen raised her hand.

“Do you think he did that on purpose?” she asked.

“Oh, yes,” I said. “I’m certain of it. For one thing, he was a genius. For another, varying sentence rhythm is what professionals do.” I followed up by showing them how Ernest Hemingway did the same thing. (See my recent post “Sentence, substance & comma joy.”)

“Art announces itself in form,” I added. “That includes sentence and paragraph length; punctuation; the rhythm of sentences, paragraphs, passages, and the entire piece. All aspects of form must be considered and intentional.”

For all the attention we give it, of course, craft isn’t the most important part of writing—far from it. That would be who you are and your intent. (See “Between self and story.”) But craft is what we can talk about and work with. Craft not only signifies art, it’s what releases art.

Early in the term, I told my memoir class one afternoon how writers emphasize at the end: the last word in a sentence, the last sentence in a paragraph, the last paragraph in a passage, the last passage in an essay or chapter. I tried to show how creative writers use space breaks, not just as transitions from one time frame or location to another but also to spike emphasis—like hitting a gong. And to provide a resting places for readers. As I wrote in “That sweet white space,” “White space is a dramatic transition and a resonant pause filled with meaning and its own kind of content, a space pregnant with time’s passage and unstated events. This is what visual artists call negative space, the resonant blankness around the main image.”

Helen wasn’t so sure about space breaks. “They seem like cheating,” she said.

“I can remember feeling that way,” I said. “When I was a journalist, I was proud of my worded transitions. And editors wouldn’t let us use space breaks anyway—they took up too much room.”

But look at the breaks that demarcate Baldwin’s classical three-act structure in “Notes of a Native Son.” Consider how heavily Scott Sanders segmented his flowing, celebrated essay about his father’s alcoholism, “Under the Influence.”

And you know what? I got Helen to try space breaks! A teacher’s joy. Along with hearing her excited statement. Writing is thinking! Writing is feeling! What a great class. Helen’s doubt made me work harder. Helen’s doubt launched not a thousand ships but influenced several lesson plans. My students’ work in this class taught me, again, how words shaped by craft reveal someone’s soul. We may all walk around stuck in our own heads, but we go to literature to share another’s subjective experience and meaning.

Yet in art, every time out is a beginning for the maker. As Jo Ann Beard told Michael Gardner in an interview for Mary:

Frankly, I thought I knew how to write, but it turned out I didn’t, and I don’t. I don’t. I get to learn it over and over and over. It isn’t supposed to be easy. It is supposed to be hard and the process of making art and the product is worth all the energy that you put into it. It is what matters. It is a noble goal. Even if you never attain it, which is true for most of us, it’s life-enhancing to try.

[“Readers like a variety of rhetorical moves”: quiz = students yelled out craft tools.]

The post Thinking and feeling appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

March 16, 2016

Mystery & manners at the brink

[Writer and editor Dorothea Brande’s Wake Up and Live (reviewed)—the movie.]

A writer’s eternal questions amidst America’s ugly political blip

Standing in my father’s library as a teenager, I opened Dorothea Brande’s slender 1934 book Becoming a Writer. I read:

Do you believe in God? Under what aspect (Hardy’s “President of the Immortals,” Wells’s “emerging God”?)

Do you believe in free will or are you a determinist? . . .

Do you think the comment “It will all be the same in a hundred years” is profound, shallow, true or false?

Suffice it to say, these and other questions in her quaint quiz stumped me as a kid. And not just because her examples were, even then, dated. But Brande (1893–1948) gave me the sense that knowing or groping toward Truth is pretty much writers’ job description. This starts as personal truth, offered to all to test against theirs. Trying to figure out bedrock truths appears to be simply a human task.

A friend, recalling my rookie reporter apprenticeship under his wing 36 years ago, called bullshit on such assertions.

“It’s so you,” he said, after reading a draft of this post. “It reminds me of several conversations we had, with you tortured by the Meaning of Life and humanity’s Big Questions and my saying why should it have meaning? I was more concerned about whether the fish were biting or whether there was good barbecue or beer somewhere.”

Okay, I’ve got an itch, hard to scratch. Yet I know my mentor’s method is to exaggerate his way to truth. I’m a lot older now, and, while still puzzled, do finally know one or two things for sure.

A comfort of aging? Maybe, given a recent realization: older folks own the world, on paper, but it really belongs to the young. Those starting out, coming up, in love. I was proud of that bit of wisdom until, on reflection, it sounded like I stole it from 1931’s bittersweet song “As Time Goes By.”

C’est la vie. The fundamental things do apply. What are they?

Community vs. the clan in 2016’s presidential primaries

Modernity versus tribalism. That’s what this has come down to. Already the conflict roiling swaths of the world, it’s what has turned this campaign season vulgar and violent.

Modernity’s ideals include diversity and tolerance. Tribalism fears differences, and its hallmark response toward the Other is kneejerk rejection. Modernity is not overtly religious, though I sense in its belief in human nature and human progress a spiritual seed. Politics and religion, at their core, share a concern with community. And of course, like free societies, all major religions—including Islam—preach tolerance. A pagan, in contrast, is anyone or any group that will not grant you their God. It’s true that when the Jews discovered God some 3,000 years ago, God was theirs and theirs alone—an angry parent sore angry at his stiff-necked offspring. But by removing God from a particular shrine or mountaintop and lofting him into the sky, they effectively made their God available to all.

As humans gradually threw off despotic leaders who sought to usurp religion’s power, religion itself moved steadily inward. In my view, it draws ever closer to to the animating mystery at its core: human goodness. What explains it? How can we nurture it?

Surely this conundrum explains religion’s reliance on metaphor. Surely it explains Judaism’s emphasis on learning. And Donald Trump is Exhibit A for why humans must grow. Learning—maybe along with some sort of spiritual practice that disciplines the ego—fosters wider, humane values. Knowledge gives you a place to stand and a means of testing rhetoric against history and literature and your sense of reality. For writers, who in one way or another profess or portray their take on human nature, learning what they believe and why seems especially essential. But, as I say, that’s just going pro with humans’ basic task.

Sober, humble leaders help people, en masse, achieve wisdom, or act on theirs. Maybe that’s because great leaders receive the group’s collective wisdom. The leader as signal receiver and servant. Does this model describe Donald Trump and his ilk?

Donald Trump’s angry cry for love

We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory will swell when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

—the close of Abraham Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address

Though he seems an intellectual and emotional mess, how well Trump understands our primate substrate. Very old, very deep, buried by more evolved emotions, under great stress the Machiavellian, clannish, pagan ape within us emerges.

Even with his short fingers, Trump can reach and punch that small, deep vestige. He’s unsound intellectually, and a craven liar, but he’s not stupid. Contrast Trump’s sly, cynical approach to politics with Abraham Lincoln’s. Lincoln was a tough politician, a fierce campaigner, but his knowledge of people and our republic still resonates. At any rate, he rose in office. In his ultimate test, fueled and fed by Shakespearean and biblical wisdom and by Enlightenment ideals, Lincoln led America through its greatest test by appealing to our better nature.

The Enlightenment gave rise to America’s still-revolutionary Constitution. What massive irony in seeing Trump and others, each the spawn of immigrants, attack immigrants in our nation of immigrants. When cheap and illegal immigrant labor forms the base of Trump’s own gaudy enterprises. When immigrants are not just part of our community, they are our community. Perhaps excepting Native Americans, immigrants are America. This attack has worked, to an extent, because so many Americans are suffering economically. They’re angry and scared. By appealing to and stoking that, a politician unleashes primitive, violent, tribal forces.

One of the perplexing issues raised by Trump’s rise has been whether it matters that his rhetoric inflames our worst qualities because he doesn’t mean what he says. Many think he’ll be different if elected. He has admitted that, for him, lying to get elected defines politics. And certainly his record, before the current campaign, resembles that of a pragmatic political moderate—maybe even one with a mildly progressive bent. Neither his businesses nor his current policies withstand scrutiny, however, except as evidence of Trump as a needy, egotistical self-serving man. He’s made a fortune, of course, in dens of gambling that exploit other humans’ vanity.

In the end what surely will inoculate America against Trump and other runts are Lincoln’s angels—humans’ bone-deep, bred-in values of morality and justice. At least Trump’s got us talking about the beliefs that bind us. Beliefs sensed in our nature, nurtured in study, tested in conflict. These ideals form the face of modernity. They’re what already make America great.

[Louis Armstrong & Nat King Cole perform “As Time Goes By”—a classic version.]

It’s still the same old story

A fight for love and glory

A case of do or die.

The world will always welcome lovers

As time goes by.

—“As Time Goes By,” words and lyrics by Herman Hupfeld, made famous in Casablanca.

The post Mystery & manners at the brink appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

March 9, 2016

Booking passage out

![[Ta-Nehisi Coates pictured in The New Yorker. Photo by Stephen Voss/Redux.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1457609409i/18379372._SX540_.jpg)

[Ta-Nehisi Coates pictured in The New Yorker. Photo by Stephen Voss/Redux.]

Ta-Nehisi Coates explains race to his son, trying to grasp it himself.

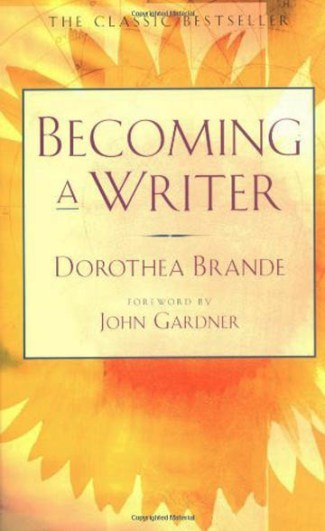

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates. New York: Spiegel & Grau, $24.00 hardcover (176 pages), July 14, 2015. Also available as ebook, CD, and audiobook.

Guest Review by Lanie Tankard

“When I discover who I am,

I’ll be free.”

—Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

Between the World and Me has reaped a lot of well-deserved attention since it came out last year. It’s a heartfelt letter from Ta-Nehisi Coates to his son, Samori. Toward the end of this slim volume, Coates poses a question to the world at large: “Is that what we wish civilization to be?”

In the 130 pages leading up to this beseeching question, Coates points out the barriers Samori will encounter because of his skin’s darker color. He attempts to define racism in various ways—personal experience, observation, examples from the news, the linguistics behind “naming,” and memories.

Throughout, Coates uses lines drawn from two black writers as a refrain. They become staccato drumbeats to hammer home his leitmotif. The watchwords act as Velcro to which observations adhere, thus pulling disparate impressions together into a distinct thought. The first phrase emanates from a poem by Richard Wright (“Between the World and Me,” found in White Man Listen!). The second is from a letter by James Baldwin to his nephew (“because they think they are white,” found in The Fire Next Time). The first, also used as the book’s title, is a placeholder for the obstacles Coates encounters in his own life, while the second mocks the absurdity of those boundaries.

It’s easy to see why Between the World and Me has garnered honors. In his acceptance speech for the 2015 National Book Award for Nonfiction, Coates explained the motivation for his manuscript. He began writing it when his friend Prince Jones “was killed because he was mistaken for a criminal” by a police officer due to the “presumption that black people somehow have a predisposition to criminality.” When Prince Jones died, Coates noted, “there were no cameras.” He went on to say: “I’m a black man in America….I can’t secure the safety of my son. What I do have the power to do is to say you won’t enroll me in this lie, you won’t make me part of it. That was what we did with Between the World and Me.” In his book, Coates explains nuances such as how loud rudeness in young black men affords them a feeling of “security and power among people with the authority to destroy your body.” He draws on other poetic voices from time to time, such as Sonia Sanchez and Amiri Baraka.

Coates bears witness by channeling his experiences through words on a page via a strong authentic voice. Although the prevailing focus in this book is race, Coates also probes class and gender within that unifying idea. His capacity to dig beneath the dominant subject and touch that preciously thin membrane between belts/books, violence/nonviolence, ignorance/education, and revolution/accord drives this book by examining the edge where such polar opposites meet. That threshold is where hope for change exists. By painting the brinks of those borders, Coates has brought us to the verge of something crucial: how to recognize what exists and alter it.

The solution for Coates resided in libraries, by which he booked passage out of the ghetto quicksand pulling down so many of his contemporaries. He talks of “how to survive the neighborhoods and shield my body.” Underpinning everything is the way in which books and education can knock down fences and change a person’s life.

Between the World and Me is a slim volume, barely over 150 pages, with black-and-white photos throughout and a rounded spine that makes it a tactile delight to clasp. It stands alone as an effective statement but is clarified by reading the earlier 2008 memoir written by Coates, The Beautiful Struggle. From that book, we learn about both the father and grandfather of Ta-Nehisi Coates, and the childhoods of all three men. When viewed together, with the addition of Samori in Between the World and Me, these two books paint a four-generation portrait of race in America.

The father of Ta-Nehisi Coates, a librarian, was a Black Panther. He beat his son but also taught him to love reading. “Thick books were hurled at us from across the room,” Coates wrote, also detailing how his grandfather raised his father, about whom Coates comments: “…once he’d been like me—from the street but not of it.”

The writing in Between the World and Me is smoother, more polished, than in the earlier book by Coates. His mother taught him to read when he was four years old, and she also taught him to write, presenting “the craft of writing as the art of thinking.” Schools did not draw Coates in, but once he discovered writing he found his strength. He emphasizes the importance of libraries and the pursuit of knowing, as well as his “deep belief that we could somehow read our way out.” Coates began working for an alternative newspaper after college, meeting the first white people he ever got to know on a personal level: editors—who were not what he expected. His description of how they gave him “the art of journalism” is moving.

Coates uses the psychology and linguistics of naming to examine verbal behavior regarding race. Historian Jacqueline Jones, in her 2013 book A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama’s America, has posited the thought that race is an obsolete method of cataloguing the homo sapiens who inhabit this planet, in an effort to focus on our commonalities.

Even though the events Coates describes occurred in the United States, his all-encompassing theme spans the globe. Over a century ago, in 1893, Cuban writer José Martí published an article titled “My Race” in Patria, a newspaper he founded. “To insist on racial divisions,” Martí wrote, “on radical differences, in an already divided people, is to place obstacles in the way of public and individual happiness, which can only be obtained by bringing people together as a nation.”

Ta-Nehisi Coates ends Between the World and Me with a powerful last sentence about rain. Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie ended her first novel Purple Hibiscus, with a similar image: “The new rains will come down soon.”

Is rain perhaps a universal metaphor for tears?

Lanie Tankard is a freelance writer and editor in Austin, Texas. She is a former production editor of Contemporary Psychology: A Journal of Reviews, and has also been an editorial writer for the Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville.

The post Booking passage out appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

March 2, 2016

Shining prose, timeless insights

[The ancient Mississippi trail where the story is set. National Park Service site.]

Welty’s “A Worn Path” an exemplar of empathy & implication.

[Welty about when she wrote the story, age 31.]

Eudora Welty’s short story “A Worn Path” depicts an aged African American woman, Phoenix Jackson, making an arduous journey through woods and fields along the Natchez Trace, an ancient trail, to the small city of Natchez, Mississippi. She’s challenged by the terrain and menaced by a stray dog and by a white quail hunter. Reading “The Worn Path” again, for the first time since I was an undergraduate, summoned its effect on me at twenty. Then, I marveled at why she went to town, revealed near the end, as if her motive was a trick Welty planted. This time, I marveled at how Welty got her there.What sent me to this masterpiece of empathy and imagination again was that last week I stumbled across Lee Smith’s essay in Garden & Gun magazine about how James Still and Welty influenced her. In their work, Smith recognized her own subject—her people, as they say in the South. What happened is that Welty came to Hollins College to read, and 19-year-old Smith watched and listened, transfixed. Welty read “A Worn Path,” Smith writes, in “her fast light voice that seemed to sing along with the words of the story.”

Here are some of the short story’s resonant sentences depicting Phoenix’s heroic journey toward town:

Putting her right foot out, she mounted the log and shut her eyes. Lifting her skirt, leveling her cane fiercely before her, like a festival figure in some parade, she began to march across. Then she opened her eyes and she was safe on the other side.

“I wasn’t as old as I thought,” she said. . . .

So she left that tree, and had to go through a barbed-wire fence. There she had to creep and crawl, spreading her knees and stretching her fingers like a baby trying to climb the steps. But she talked loudly to herself: she could not let her dress be torn now, so late in the day, and she could not pay for having her arm or her leg sawed off if she got caught fast where she was.

She kicked her foot over the furrow, and with mouth drawn down, shook her head once or twice in a little strutting way. . . . .

Then she went on, parting her way from side to side with the cane, through the whispering [corn]field. At last she came to the end, to a wagon track where the silver grass blew between the red ruts. The quail were walking around like pullets, seeming all dainty and unseen. . . .

Deep, deep the road went down between the high green-colored banks. Overhead the live-oaks met, and it was as dark as a cave. . . .

Over she went in the ditch, like a little puff of milkweed. . . .

He patted the stuffed bag he carried, and there hung down a little closed claw. It was one of the bob-whites, with its beak hooked bitterly to show it was dead. . . .

Her fingers slid down and along the ground under the piece of money with the grace and care they would have in lifting an egg from under a setting hen.

There’s the magic of her “little strutting way,” though it may help if you love poultry. I imprinted on chickens about the time I walked. So I can testify to the perfection of quail “walking around like pullets,” but what’s thrilling is how such comparisons arise from Phoenix’s old-time country consciousness. Pick any metaphor above that you can test. As a new grandpa, I rejoice in “stretching her fingers like a baby trying to climb the steps” too. Welty looked, and she saw. But maybe you don’t have to know babies or setting hens, because if an image is perfect, imagination engages.

By the time the hero of “The Worn Path” meets the white bully and some clueless city folks in town, we know her well. And as she tries to get help in town, the story’s full implication blossoms. Having given life to an old lady in a hard situation, Welty achieved one of narrative’s highest arts—associated with fiction but possible in nonfiction—of giving readers an experience and letting them add two and two for themselves.

Welty’s comment, in her fine memoir One Writer’s Beginnings, applies:

Greater than scene, I came to see, is situation. Greater than situation is implication. Greater than all of these is a single, entire human being, who will never be confined in any frame.

“A Worn Path” appeared in Welty’s first collection, in 1941, A Curtain of Green. The book includes two other often-anthologized stories, the comedic masterpieces “Why I Live at the P.O.” and “Petrified Man.” Welty was 32. Marianne Hauser raved in her review for the New York Times:

To explain just why these stories impress one so appears as difficult as to define why an ordinary face, encountered by chance in the street, might suddenly reveal miraculous beauty, through a smile perhaps, or through an unexpected expression of sadness.

Many of the stories are dark, weird and often unspeakably sad in mood, yet there is no trace of personal frustration in them, neither harshness nor sentimental resignation; but an alert, constant awareness of life as a whole, and that profound, intuitive understanding of life which enables the artist to accept it.

Welty’s writing, fiction and memoir, brings us the kind of stories we urgently tell loved ones, or simply turn over in our minds for a lifetime. They brim with human life and tug at us with that selfsame mystery.

The post Shining prose, timeless insights appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

February 24, 2016

Sentence, substance & comma joy

There’s only two kinds of truth.

Let’s get it straight from the start.

It’s all what you believe

in your head and your heart.—Van Morrison, “Little Village”

[James Baldwin: master of style & substance.]

Thankfully teaching impels me to reread and study great literature. I’ve just reread, for a class I’m teaching, “Notes of a Native Son,” America’s greatest essay—greatest because its content deals with our nation’s great topic, race, and because of its artistry—and seen something new in James Baldwin’s famous prose style.Of course his sentences work within a framed structure, opening with his father’s funeral and returning to it to close, and the essay is classically broken into three acts as well. Then there’s Baldwin’s thundering Old Testament condemnation of racism. He shows and explains his own bewildering, maddening experiences with discrimination in the 1950s. And he sees at last how the racism of America’s long apartheid era warped his father. But Baldwin, then 19, has returned too late to his father’s deathbed for them to talk, let alone to discuss how to live with this burden of bitterness.

The essay’s rounded sentences, gravid with clauses and commas, convey a deep and subtle mind groping toward personal and universal truths. Baldwin’s prose itself ruminates. He can be as halting as Henry James. At the same time, conversely, he speeds up his orotund sentences. The combination of lingering and racing ahead creates an interesting rhythm, which is part of the essay’s powerful effect. In both content and style, “Notes of a Native Son” is at once chewy and flowing.

This time through, I saw clearer why that is. Many of the commas that truncate the essay’s sentences are unnecessary, strictly speaking, but lend the essay its thoughtful air. Yet Baldwin usually omits commas at a key juncture. He consistently breaks the rule-of-thumb that commas should assist conjunctions when joining independent clauses. Here’s how I show students this guideline:

The brown dog barked, and the black cat ran.

Without the comma, the “and” seems to set up another action by the dog. Maybe it barked and bit. Without a comma’s cue to slow up, the reader can stumble into that cat. I follow the comma-with-conjunction rule obediently myself, sometimes daring to delete a few commas later. Breaking this convention, however, has a distinguished history. Ernest Hemingway famously linked successive independent clauses only with “and.” Such writers make us to do the work of mentally inserting the commas that traditionally demarcate such clauses, teaching us finally to let go and savor the lilt of sentences without them. Cormac McCarthy loves to omit even more commas, and trains us to his rhythm.

As for Baldwin, he appears to eschew commas with conjunctions in order to impart urgency to otherwise leisurely prose. Note in the example below from “Notes of a Native Son” how, in the first sentence, he omits the called-for comma and then uses a highly optional one, a New Yorker comma, as I think of it. In the second sentence, he declines to set off the introductory clause with a comma but then uses another New Yorker comma. The third sentence restores Baldwin’s thoughtful self-interrupting rhythm. I’ve inserted in brackets where the missing commas might go in the first and second sentences:

When planning a birthday celebration one naturally does not expect that it will be up against competition from a funeral [,] and this girl had anticipated take me out that night, for a big dinner and nightclub afterwards. Sometime during the course of that long day [,] we decided that we would go out anyway, when my father’s funeral service was over. I imagine I decided it, since, as the funeral hour approached, it became clearer and clearer to me that I would not know what to do with myself when it was over.

Here’s another example in which Baldwin eschews the called-for comma-with-conjunction three times in a row. The first sentence in this scene, at his father’s funeral, simply declines the comma. The second declines the comma twice and then employs two commas at the close.

The casket now was opened [,] and the mourners were being led up the aisle to look for the last time on the deceased. The assumption was that the family was too overcome with grief to be allowed to make this journey alone [,] and I watched while my aunt was led to the casket [,] and, muffled in black, and shaking, led back to her seat.

Note how after three rushing independent clauses, Baldwin makes us tap our brakes at the end of the last clause by using two commas. The second of those commas seems, again, very optional, a poet’s usage—most would’ve written “muffled in black and shaking”—but thereby Baldwin makes us see his elderly aunt’s helpless grief for his fractious father. Here again, Baldwin’s doing two things at once, achieving a reasoning manner alongside expressing the raw truth of his heart.

Art, as it will, announces itself first in form in Baldwin’s eloquent memoir essay. But what ultimately makes “Notes of a Native Son” great literature is what it shares with almost all great literature—its illumination of the everlasting and apparently innate human hunger for justice.

The post Sentence, substance & comma joy appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

February 10, 2016

Making old stories new

[New Yorker writer Adam Gropnik: the hip-hop musical Hamilton may be “the great work of art, so far, of the twenty-first century.” Image @New York Times]

Auditing inner & outer narratives amidst the 2016 political fray.

He was born a penniless orphan in St. Croix, of illegitimate birth, became George Washington’s right-hand man, became treasury secretary, caught beef with every other founding father, and all on the strength of his writing.

I think he embodies the word’s ability to make a difference.

— Lin-Manuel Miranda introducing his musical Hamilton, how a huge hit, in a 2009 preview at the White House.

Like everyone, I’m trying to distill meaning from the deluge of our presidential campaign season. What stories about themselves—and America—are candidates selling? How will the competing truths of those left standing square with mine? What vision will voters pick for the title of Overarching Narrative?

My reflexive analysis occurs while I’m completing an essay about how memory, imagination, and story intertwine. The surprising byproduct of my work has been a radical rethinking of some of my long-unexamined inner narratives. This has been positive personally, and powerful for my essay. Meanwhile, as events, stories, and spin erupt on the national stage, I can only hope our republic’s story emerges from its test similarly affirmed.

Politically, I sway between brilliant writers’ truths. For a day, I fell under the spell of Charles M. Blow’s deft essay in the New York Times, “White America’s ‘Broken Heart.’” Blow lauds Bill Clinton’s “clear rhetorical framing” of the current narrative as being about white America’s anxiety in sharing a new demographic future. Then I leapt to an even more subtle accounting, R.R. Reno’s New York Times essay “How Both Parties Lost the White Middle Class.” Reno calls the racial theory a “huge distraction” from the real issue: those flourishing in the global economy and those foundering.

Reno’s interpretation better fits my sense of simple human self-interest. And it squares with my grand narrative of America as an exceptional but-of-course-flawed child of the Enlightenment. A recent peak of which is that we elected Barack Obama—twice—with votes from members of each party and all races. Reno observes that extreme narratives from both sides blame, in ultimate effect, the white middle class for its own pain. Those stories stoke anger, stir resentment, and worsen a sense of crisis. Then there are simply hateful candidates, such as Donald Trump and Ted Cruz with their rage, egotism, and guile. How mistaken their notions of human history and human nature; how meager their own ideas. In colonial times, invitations to meet with pistols at twenty paces greeted less annoying fools.

II.

The question clearly being asked in an exemplary memoir is ‘Who am I?’ Who exactly is this ‘I’ upon whom turns the significance of this story-taken-directly-from-life? On that question the writer of memoir must deliver. Not with an answer but with depth of inquiry.—Vivian Gornick, The Situation and the Story

In my own life, I’ve grown suspicious of stories that omit my own nature and agency. Maybe that’s middle-aged wisdom, or just a drop in testosterone. But compassion and humor now seem most characteristic of truth. (Adios Papa Hemingway, bitterly stoic sage of my youth.) Under the influence of work on my essay, which puts a childhood memory of a trip with my father under a microscope, I’m learning to ask questions such as What else? and What if?

What if I’d been good at math? Like my Mom or her father, a math teacher, instead of barely able to add two and two? I might be living a different story, having made different choices. My concerned mother’s story was that I fell between the cracks in the national switch to New Math. My big sister dubbed my innumeracy a “mental block.” My own suspicion is that my disability involved fear or some kind of daydreamer’s rebellion. Or both. The point is, it’s hard to solve for X: the irreducible you. And yet a fair memoir pivots on X. Writing can actually help in finding it, at least if the goal is art, and therefore truth, instead of a tired narrative’s reinforcement. We can’t escape the human mind’s operating system—stories—so getting better at telling them might make us happier.

My math example may seem trivial, but to me it resonates with implication. How hard it is to see one’s own history and agency anew. I recall in graduate school a fellow student’s memoir about her awful ex. He did seem dreadful. But none of us in workshop knew how or whether to ask our burning question: Why did you stay with him for ten years? She’d gotten halfway. He was the situation. She was the story.

III.

Artistic growth is, more than anything else, a refining of a sense of truthfulness. The stupid believe that to be truthful is easy; only the artist, the great artist knows how difficult it is.—Willa Cather

One of the milder counter-narratives to my sunny view of Obama’s meaning: “Yeah, we gave our nation to the black guy—after the white guy totally, criminally fubar-ed it.” At least that story is halfway funny. Using my compassion-or-humor test, maybe there’s a truth there. But I see Obama as such an emblem of America’s ideals and as such palpable evidence of our human destiny that I give us more credit. I hope that, in our collective wisdom, we’ll rise again beyond stories that, from whichever side, trash the better angels of our nature.

[Miranda: writer, actor, alchemist. @Matthew Murphy]

New stories take work; they require insight and imagination. But boy do they wallop. See how writer Lin-Manuel Miranda slashed bone-deep, unveiling in Hamilton, which opened on Broadway last August, the grandeur of new possibilities and emerging realities. Metaphor and implication do heavy lifting. The founding fathers as rapping rebels: brilliant. Hip-hop upstarts as foundational players: genius. Miranda read Ron Chernow’s 2005 biography of Alexander Hamilton and—glory be—inspiration arced between those pages of history and Miranda’s own life and times. Soon America’s narrative awoke in the footlights in new colors.Adam Gropnik’s fine New Yorker essay on the musical says it asks “what it means to be a progressive hero in the age of Obama.” In tune with our transformative president, it offers a “stunning,” “astonishing” transformative vision, showing “previously marginalized people taking on the responsibility and burden of American history.” Gropnik quotes a friend: Hamilton is “the great work of art, so far, of the twenty-first century.” Then he tells a story of Miranda performing an early version of the musical at the White House for an audience that included Obama:

When he explains his purpose—Hamilton as hip-hop hero!—everyone laughs. Then you see Obama quietly smiling as he listens: he gets it.

Here’s Obama, student of history and historic figure himself, who, among other things, may be the best writer we’ve ever elected president. What does Obama get? What does he see? What might we?

[Magic below: Miranda’s charming performance for Obama.]

The post Making old stories new appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

February 4, 2016

The complexity of purity

[Taken at the Guiness brewery, Dublin, Ireland, @Richard Gilbert.]

Purity by Jonathan FranzenNew York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, $28.00 hardcover (September 1, 2015, 576 pages); also available as ebook, CD, large type, and digital audio. US trade paperback edition due out September 6, 2016, from Picador.

Guest Review by Lanie Tankard

Purity is the power to contemplate defilement.

Extreme purity can contemplate both the pure and the impure; impurity can do neither: the pure frightens it, the impure absorbs it. It has to have a mixture.

—Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace

[Does Jonathan Franzen’s latest surpass Freedom?]

The question is not whether to read Jonathan Franzen’s novel Purity if you haven’t by now. Rather, the question is when. This latest novel from one of America’s finest writers appeared September 1, 2015. Now we’re at the midpoint between last fall’s published hardback and this fall’s anticipated paper, which won’t come out until September 6. And that creates a small dilemma—which version to select? Grab what’s available now and delve right in? Or hold back another six months and snag the US trade paperback edition with a yet-to-be-revealed mystery cover?Franzen’s an artist who mixes an era’s most salient ideas on his palette to paint the spirit of the times in the novels on his easel. I’ve reviewed an earlier book, Freedom (Part 1 and Part 2). In this novel, he’s opened himself up in far more personal and vulnerable ways, which is rare for a writer. The chapter titles alone are intriguing:

Purity in Oakland

The Republic of Bad Taste

Too Much Information

Moonglow Dairy

[le1o9n8a0rd]

The Killer

The Rain Comes

With certain characters, Franzen creates a fictional pastiche of actual people. The tension buildup in several sections made my heart race. His timing is impeccable. I noticed I was holding my breath as I read lines such as “Everyone thinks they have strict limits…until they cross them.” Franzen subtly primes his canvas with a layer of deep questions as if he were applying gesso, building it up in a leisurely manner with wit and wisdom combined. Readers hardly realize the plotline they’re following is tossing out reflections: Is madness inherited? Can we be sure there’s not a god? They anchor the surrounding action.

So much spot-on social observation takes place. One finds inside jokes from the literary world about other writers. There are thoughts about fame and its loneliness shared by someone who is famous. We encounter male-dominated Silicon Valley and the paucity of girls writing code. Then, along come Peyton Manning and the Denver Broncos—side by side with Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Proust, and Dickens. The settings roam the world.

The overlooked humor in Franzen’s writing

[Jonathan Franzen sees himself as a comic writer.]

Franzen delves, in occasionally hilarious ways, into practically every academic discipline across any university campus. He explores such ideas as “moral hazard” from economics, renewable energy, interventions used in attempts to change norms (“Quite a few of your neighbors have expressed strong interest in…”), branding, transparency, privacy, eye contact, TMI, the British versus American pronunciation of “a,” thermodynamics contrasted with integral calculus, individualism and collectivism . . . the list goes on.Here’s what Franzen himself had to say about his book a couple weeks after it was released. I caught him in a full house at BookPeople in Austin, Texas, on September 19, 2015. He walked out attired in dark tones: black jeans, brown shoes, black frame glasses, and gray shirt—with shirtsleeves rolled halfway up to his elbows.

“Hottest it’s ever been since I’ve been coming here,” he noted, toting a water bottle. “I see a lot of people standing, but I’m comforting myself by realizing I’m standing, too.”

And standing before me was a far more jovial, relaxed, and bantering Jonathan Franzen than the one I had heard in the very same spot five years earlier on his book tour for Freedom. He began by reading from Purity, playing to the Texas locale with one selection. In a paragraph about a thermonuclear warhead in Amarillo, he totally cracked himself up over the author’s humor when he spoke a certain line (“Why would you do that?”). He took a minute to regain his composure, perhaps underscoring a self-observation he made in a 2010 interview in The Paris Review. The question had been: “What are people missing or overlooking in your work?” Franzen replied: “…what seems to me most often overlooked is that I consider myself essentially a comic writer.”

Still, one student in the Austin audience wanted to know: “My professor said it’s good when writing stories to get at universal truths. Do you agree? What are your goals?” Franzen pondered before saying, “I do know about Universal Truths, but trying to arrive at one is perhaps not the best way to get there.”

How Franzen distills his ideas into an overriding concern

The epigraph Franzen used in Purity is:

…Die stets das Böse will und stets das Gute schafft

[Purity‘s Faust connection: Does evil do the good?]

It’s a line in Goethe’s German play Faust from a conversation between Heinrich Faust (a scholar) and Mephistopheles (the devil, also called Mephisto). Faust asks, “Well, who are you?” Mephistopheles answers with Franzen’s epigraph, which can be cryptically translated as: “A part of that power, The Evil ever do, and ever does the good.” The riddle addresses human nature’s duality, or the fight between good and evil. Does darkness give birth to light or does light give birth to darkness? Is it a cyclical process? In Purity, Franzen delves into principles that Hegel believed ran the world’s history.I asked Franzen if he had rewritten the Faust legend in Purity to capture the zeitgeist of this century.

“Hmmm, not consciously,” he said. “I like Goethe’s Faust so much, but it was all done after the fact. I was having fun with it.” Franzen later noted that Purity was “strict realism, about an embittered novelist who had once been somebody and now was nothing.”

Another audience member wondered whether Franzen had been trying to honor the character of Tyrone Slothrop from Thomas Pynchon’s novel, Gravity’s Rainbow, but Franzen denied it.

“I don’t really do homage,” he responded. “Pynchon was not the first person to notice what rockets look like.”

Franzen’s research process?

“It does not merit the dignity of a word like ‘process.’ I love reading but I hate research,” he stated. “You don’t want to let facts stand in the way of what you’re making up.”

Would he ever write a historical novel? “No,” but acknowledged several authors he felt had done an excellent job with them: Jane Smiley and Penelope Fitzgerald.

“In The Blue Flower,” he said, “Fitzgerald drew such a totally believable historical period she totally forgot about it and was immersed in the era she’d created.”

Franzen confided he’d sprinkled throughout Purity what he called “love poems” to various entities like journalism and birds, and mentioned he’d indulged his fondness for birds while on his current book tour: “I try to multitask, so I went to Hornsby Bend [a bird observatory near Austin] this morning, past the sewage ponds. Why did I do that? I fell in love with birds.”

Franzen confessed he’d approached the publication of Purity with a sense of dread. “I’m shocked it’s been well reviewed….I felt so beat up when I finished. Writing books has become a personal matter.”

How do you feel when you notice people reading your books?

“There’s no author in the world who doesn’t look at the bookshelves when they go to someone’s home, to see if their books are there.”

Is Purity on your bookshelf? It’s not a quick beach read. It’s long and thought provoking, but also funny—possibly one of the best investments of a reader’s attention to come along in decades. So many books; so little time. Decisions, decisions. Hardback or paperback? Now or later? Your choice, but don’t miss Purity.

Lanie Tankard is a freelance writer and editor in Austin, Texas. She is a former production editor of Contemporary Psychology: A Journal of Reviews, and has also been an editorial writer for the Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville.

The post The complexity of purity appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

January 20, 2016

The power to charm

[David Bowie scared some of us in the 1970s as he shifted global consciousness. His sly 1972 performance above of “Starman” catches a young lycra-clad Bowie’s expressiveness. Throwing his arm companionably around guitarist Mick Ronsons’s shoulders stirred a ruckus. Liver cancer took them both. The performance from which this photo is taken is must-watching on YouTube.]

Anthony Lane’s essay loves on Bowie best—I love both performers for their wit, emotional expressiveness & poetic panache.

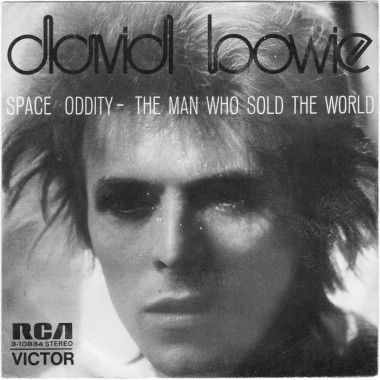

[Bowie broke out in 1969 with “Space Oddity.]

Anthony Lane’s irreverent reviews for the New Yorker of Hollywood blockbusters make me laugh. He’s fun, quite cheeky. But I’m always pleased when he casts his wit and his elegant sentences toward what he admires. Such as his recent appreciation of Todd Haynes’s film Carol about forbidden love between two women in 1952 America. Less than 20 years after that repressed era, David Bowie, with his androgyny and his openness about his bisexuality, helped usher the shift in consciousness that has culminated in America in marriage equality. Among last week’s many tributes to Bowie, surely there wasn’t a finer one than Lane’s for his fellow Brit, “David Bowie in the Movies.”For a brief essay, Lane’s reflects deep processing and manages a thrilling range of considerations. Like Bowie’s work, Lane’s delights in its own performance but hits you with unexpected emotional force.

If genius is brilliance plus output, Bowie certainly qualifies as one. Even among superstar performers, that rarified group, he seemed one in a million. In an ultimately soaring appreciation, Lane takes a measured view of Bowie’s film work. Most of Bowie’s roles were in minor films, Lane says. He doesn’t crown Bowie as a great movie actor, while noting his performance instinct and impact:

To listen to some of the tributes paid over the past couple of days, you might think that Bowie had spent most of his earthly span in a jumpsuit of many colors, or in other varieties of extraterrestrial garb, whereas the sobering fact is that the Ziggy Stardust tour lasted a mere eighteen months. Questioned, early on, about his quicksilver style, Bowie said, “It’s like looking at an actor’s films, and taking clippings from the films, and saying, ‘Here he is.’ ” Notice the stress on the clip. Well before the advent of the music video (another short form that he mastered), and decades before YouTube, Bowie foresaw that our taste, and our impatient appetites, would beckon us toward the fragmentary. He had the courage of his own brevity, being not just canny enough to leave his fans aching for more but wise enough to know that the incandescent glow of a look is all the more enduring, on the public retina, for being snuffed out. Then he paused, relit himself as something else, and carried on.

[1972: The durable Ziggy Stardust alien persona.]

Bowie was frustrated, as Lane implies, by how his comparatively brief Ziggy persona clung to him. Yet Bowie’s adoption of the space waif motif, as astronaut or alien, ran through his career from first to last. A year after Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, and just five days before America’s Apollo 11 manned mission to the moon in July 1969, Bowie launched his first hit, the wistful, wittily titled, and perfectly timed “Space Oddity.” This song, which both humanized space exploration and underscored its lonely outreach, came bundled with Bowie’s otherworldly panache and epicene beauty.His steady output proves he was more than these personal qualities, or just someone milking a great metaphor. For evidence see his amusing 2013 music video of “The Stars (Are Out Tonight)”—with Tilda Swinton as his wife—or the ultimate proof, Blackstar, his creative response to a diagnosis of terminal cancer, released on his 69th birthday, just days before his death, and his haunting performance of its title track.

![[1980: Back to Major Tom in “Ashes to Ashes.”]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1453383215i/17819743.jpg)

[1980: Back to stranded astronaut Major Tom.]

We turn to a performer’s youth to remind us what hooked us and to see the dawning of his gift. In 1969, and for some time after, Bowie could shock. His pretty painted face, his glitzy getups. He sure scared me, as the southern and surf-town boy I was, despite my feeling the tug of melancholy narratives like “Space Oddity” or the joy of Picasso-esque mashups like “Suffragette City.” There was a divide I wasn’t fully aware of between British rockers’ theatricality and their American counterparts clad in jeans. Indeed Bowie and his friend Iggy Pop thought of themselves as directly taking on this blue-collar or tie-dyed hippie aesthetic. It’s all performance, Bowie said. Yet as an American I’m hardwired to respond to denim semiotics. As Bowie once said, Bruce Springsteen must wear that costume to sing his American anthems. British performers’ admission of artifice and their frank love of glamor was, and remains, a corrective to Yank naivete and piety.As he aged, Bowie learned he could “use the Internet to slip in and out of our consciousness, like a guest or an amicable ghost,” Lane writes. His songs arrived embedded in striking music videos and short films on YouTube. Lane:

2013 was not a bad year for the cinema, what with films such as “12 Years a Slave,” “The Great Beauty,” and “Blue is the Warmest Color,” but none of them, I think, had the sudden impact that was made by Bowie’s “Where Are We Now?”—the song that fell to earth, unheralded and unhyped, on January 8th. “Just walking the dead,” he sang, without fanfare or ado, like a man out walking his dog. Stories were told of grown men switching on their radios, hearing that new cry from a familiar voice, and being stirred to the brink of tears. . . .

Nobody, nowadays, recalls much of “Absolute Beginners” (1986), and rightly so, but the whole enterprise was worth it for the title song that Bowie provided—for the single chord, to be honest, that strikes between the first and second lines of the verse: “I’ve nothing much to offer / There’s nothing much to take.” But why are we struck so? What is it in the echo of that strum that refuses to go away? In a word, surprise. Time and again, whether in the symphonic flourishes of his dress-sense or in the choice of one note, Bowie perceived our expectations and swerved aside. He grew weary, it is alleged, of the “Serious Moonlight” tour, in 1983, and perplexed by the pitch of fame that it brought, but I cannot forget the Shakespearean shock of hearing that adjective for the first time, on “Let’s Dance.” Moonlight had always been gentle, or flattering, or soft; it was the stuff of sonatas and serenades. But who knew that it could be serious, like an ailment or an affair of state?

As Lane’s eloquent take on Bowie builds, he addresses my intractable qualms about movies being a lesser form of art beside literature: “Movies are the bedmates of poetry, as Bowie knew, and to treat them as a sort of illustrated novel is to load them with a burden they were scarcely designed to bear.” Noted, sir. Since I respond to Bowie’s elliptical touch, his riveting quickness, his warm presence amidst a polished demeanor, all the better if he brought that flash to Zoolander.

///

After a space break, Lane considers the use of Bowie’s music in movies, and his essay rises to an unusual emotional peak. He appropriates two of Bowie’s rhyming lines, from “Life on Mars,” in his riff on how The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou permitted Wes Anderson to “pour forth his devotion” to Bowie:

[W]e realize that Anderson is doing what millions of others have done before: he is handing over his feelings to David Bowie, and letting a song do all the work of the heart. Why write dialogue when the wild exclamations of another artist, recorded in 1971, will give vent to everything that you want your characters to say—or, rather, what they cannot say because it is all too much? Such is the yearning that beats throughout this scene. You can see it ten times or more. It is never a saddening bore.

But isn’t that what we do, entrust our feelings to artists, who paint them across the sky? It’s hard to imagine Bowie not being an artist, though he once said the happier existence seemed to him an ordinary workaday life with evenings spent in the warm bosom of a provided-for family. To spur his writing, Bowie was known to exile himself to places he hated, such as Los Angeles, or that made him feel the utter alien, like Japan. He set his own path early, and trained for the job of emotional expression. In youth he studied painting, music, graphic design, dance, and mime. And then “Space Oddity” arose, when Bowie was about 23, out of a long apprenticeship in bands. For all his admitted personal excesses, he was hard-working man.

Bowie defined himself as disciplined because he completed his ideas, however tedious the process of realizing them might become for him. And clearly he enjoyed himself with others under the spotlight, whether in performance (see his exuberant dancing with Mick Jagger to “Dancing in the Street”) or on countless TV talk shows. I’ve always been a fan above all of Bob Dylan, such a Shakespeare of our time, yet feel rueful watching Dylan’s unwelcoming introverted-unto-isolated demeanor. What a grace that Bowie could regard us with delight.

![[1983: “Modern Love”: Modern Love gets me to the Church on Time / Church on Time terrifies me / Church on Time makes me party / Church on Time puts my trust in God and Man]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1453383215i/17819744.jpg)

[1983: “Modern Love”: Modern Love gets me to the Church on Time / Church on Time terrifies me / Church on Time makes me party / Church on Time puts my trust in God and Man]

The Russian acting theorist Konstantin Stanislavsky said that beyond talent and craft was a gift he called “stage charm.” Blessed are the few performers who possess it, not all of them handsome leading ladies and gentlemen. Bowie exuded this concentrated likability. Lane explains Bowie’s charisma by touching on his joyous hit “Modern Love,” which features Bowie’s seeming self-assessment, “It’s not really work / It’s just the power to charm”:One thing to be wary of, with Bowie as with the Beatles, is the grave danger of forgetting how funny he was, and how easily amused. Mingled with the freak show was a generous stock of common sense, plus a measure of companionable cheer, and that Martian glare was readily supplanted by a grin. Behind him stood the music hall, and the garrulous double-act of Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, and other staples of popular diversion; one band he joined in the sixties, the Lower Third, used to perform “Chim Chim Cher-ee,” from “Mary Poppins,” and “Modern Love” is not so modern that it can’t afford to glance back, in the exhortation “Get me to the church on time,” to “My Fair Lady.” The octave between the two syllables of “Starman,” in Bowie’s song of that name, is lifted from the interval between “Some” and “where” in “Somewhere over the Rainbow.”

![[2016: Bowie exits with “Blackstar.”]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1453383215i/17819745.png)

[2016: Bowie exits with “Blackstar.”]

Art is made of emotion and it’s about emotion. Lane’s essay showcases perhaps the highest role of the critic, to be emotionally responsive in turn. Which challenges his audience to do likewise. Of course the critic must appreciate without becoming slavish, must show how the artist is pushing our buttons—and teach us that appreciation too. In his New Yorker essay, Lane, like Bowie, is working out a delicate calculus between heart and head. He explains what we had in Bowie, someone who made art with such care and offered it so freely. But though gone himself, Bowie’s work isn’t lost. Not anymore, not in the techno-jangled world that provoked his lifelong and defiantly celebratory reply.I’m eager to see The Life Aquatic again and experience with Lane’s help the scenes with Bowie’s music. Meantime, Bowie’s hits are on autoplay on my soundtrack. Indeed rock ‘n roll never forgets: works of art are messages sealed in bottles. But the notion arises that if you miss the art of your time, in its time, you just might miss your time. Maybe it takes a professional appreciator like Anthony Lane, so often the funny-but-frosty Cambridge man, to sound that warning. I take Lane’s implication from what’s there and what’s not. The bones are plain to see. He made emotion into an essay, and used that shapely vessel to pour forth his love.

[Bowie was an avid reader—see his list of 100 favorite books in The Guardian, which also ran an interesting review of his effectively posthumous album Blackstar that helps put his career in perspective. The photo below is from another must-see performance in 2000 of his 1980 hit “Ashes to Ashes,” which updated his 1969 breakout song “Space Oddity.”]

Do you remember a guy that’s been / In such an early song / I’ve heard a rumour from Ground Control / Oh no, don’t say it’s true . . .

Ashes to ashes, funk to funky / We know Major Tom’s a junkie / Strung out in heaven’s high / Hitting an all-time low

Time and again I tell myself / I’ll stay clean tonight / But the little green wheels keep following me / Oh, no, not again

—“Ashes to Ashes”

The post The power to charm appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

January 13, 2016

Honesty in memoir, ver. 4.0

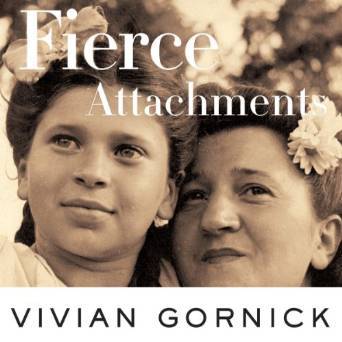

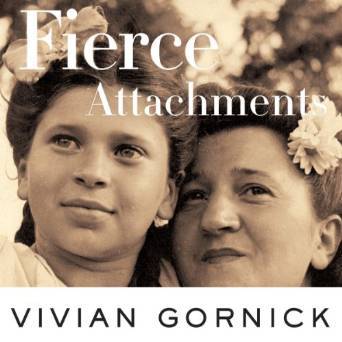

[Vivian as a girl with her Ma.]

What’s the difference, in reading experience, between fiction and nonfiction? Between reading a novel and reading a memoir?I thought about this during the past week as I reread one of my all-time favorite memoirs, Fierce Attachments. In it, Vivian Gornick braids her story, alternating between the writer’s childhood past, her adult relationship with her mother as they talk or walk around New York, and continuing into her adult experience with men. Gornick both discusses and dramatizes these realms. She is a master of the reflective persona and also of bringing her experience to life in scene.

I’d read the book three or four times before. But this time I had just slogged through a traditional chronological plotted novel, a traditional plotted and chronological memoir that verged on autobiography, and was trying to read another traditional plotted novel. These books, in stark contrast to Gornick’s, were heavy going. Her thinking and writing—at the sentence and structural level—excited me as before.

But would I be loving Fierce Attachments if it were fiction? If it had been written and sold as a novel? How much does my enjoyment owe to its labeling as nonfiction?

Let’s get something out of the way. Gornick once mentioned to a roomful of journalists that she invented in Fierce Attachments a street encounter she and her mother experienced. The reporters were soon baying at her, and the flap spread online. I can’t endorse what she did, but it hasn’t bothered me as her reader because her goal seems only to fully and honestly portray herself and mother. She might have handled her imagination differently, such as cued the reader, but instead she embroidered.

Still, try to read Fierce Attachments as a novel. Would I find it as absorbing? I kept asking

Some fiction asks me to suspend too much disbelief

Living beside a college with an impressive drama program, I watch many plays. Gradually it dawned that much fiction is driven by portraying conflicts that actually never happen in most lives. I mean family fights or blowups with friends in which longstanding resentments are aired, lanced, and resolved. I know, it’s drama. The theatre could scarcely exist without this convention.

Of course people do disagree and even fight, sure. They yell and sometimes throw things, I understand. But more often, people sublimate or seethe. Aren’t fights, when they happen, quick, a few words? Often harsh only in retrospect? And then years follow when nothing is fixed. But neither is anything fatally broken—as in a verbal brawl. The truth is, we’re a civilized species, with key defaults of repression and depression. We swallow pain to avoid worse pain.

You wouldn’t know this from many plays, movies, short stories, and novels. I imagine that this conflict flows from the fictionist’s inciting question, What if? Maybe s/he broods upon buried feelings to turn a human wish for healing into literary art. The result is what might happen if people would do what in fact they wisely avoid: use rage in pursuit of transcendence.

But people do rage in Gornick’s memoir!

![[Vivian Gornick.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1452798986i/17745439.jpg)

[Vivian Gornick.]

Boy, is this an irony. Gornick and her mother are stereotypes of an immigrant Jewish or perhaps Yiddish culture in which people pick at each other. At least her mother does. In response, mother and daughter often shout and even scream. As a repressed WASP, I envy the emotional venting. But not the obvious pain and insecurity the constant criticism creates. Oy vey!All the same, the ferocity in Fierce Attachments is different from fiction’s. It’s more intimate, more real. It’s less clear what it’s about, and the outcome is much less healing.

Most fiction isn’t Anna Karenina. It’s some guy wondering, What would’ve happened if Mama had poured a bottle of wine over Daddy’s head? I’m generalizing about fiction here. And not bashing it—my top ten books list might include eight novels. But as emotionally extreme as Gornick’s upbringing apparently was, her world is subtle compared with popular fiction’s.

I decided, quite reluctantly, that much of the appeal of Fierce Attachments is due to it being nonfiction. It probably wouldn’t be exciting enough as a novel, except maybe in the most rarified literary form. But as a memoir depicting the forces and especially the mother that forged the writer? Wow.

Memoir’s peculiar appeal

Hewing as much as possible to nonfiction’s promise to be nonfiction is important because that promise embodies a crucial aspect of nonfiction’s appeal. Someone like you or me is working hard to understand and convey her life. Since some of us are walking around doing that in our heads, it’s compelling to read someone’s shaped but real and real-time account of this task.

Memoir isn’t allowed to be boring just because “it happened.” And it won’t be, however quiet its surface events, if it is fulfilling its role as an instrument of inquiry and understanding. Those virtues also remove the taint of voyeurism in memoirs that depict trauma and severe dysfunction.

Memoir’s peculiar appeal lies not in its label of truth but the effort we sense someone making to arrive at deeply personal truth and honest self-portrayal. That’s the honesty in memoir—subjective truth and unsparing self-portrayal. I have thrown down a memoir in disgust for their lack. I honor Gornick’s for their presence.

Take my 2016 memoir challenge. Take your favorite memoir and try to read it as fiction. Very instructive.

The post Honesty in memoir, ver. 4.0 appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

Honesty in memoir 4.0

[Vivian as a girl with her Ma.]

What’s the difference, in reading experience, between fiction and nonfiction? Between reading a novel and reading a memoir?I thought about this during the past week as I reread one of my all-time favorite memoirs, Fierce Attachments. In it, Vivian Gornick braids her story, alternating between the writer’s childhood past, her adult relationship with her mother as they talk or walk around New York, and continuing into her adult experience with men. Gornick both discusses and dramatizes these realms. She is a master of the reflective persona and also of bringing her experience to life in scene.

I’d read the book three or four times before. But this time I had just slogged through a traditional chronological plotted novel, a traditional plotted and chronological memoir that verged on autobiography, and was trying to read another traditional plotted novel. These books, in stark contrast to Gornick’s, were heavy going. Her thinking and writing—at the sentence and structural level—excited me as before.

But would I be loving Fierce Attachments if it were fiction? If it had been written and sold as a novel? How much does my enjoyment owe to its labeling as nonfiction?

Let’s get something out of the way. Gornick once mentioned to a roomful of journalists that she invented in Fierce Attachments a street encounter she and her mother experienced. The reporters were soon baying at her, and the flap spread online. I can’t endorse what she did, but it hasn’t bothered me as her reader because her goal seems only to fully and honestly portray herself and mother. She might have handled her imagination differently, such as cued the reader, but instead she embroidered.

Still, try to read Fierce Attachments as a novel. Would I find it as absorbing? I kept asking

Some fiction asks me to suspend too much disbelief

Living beside a college with an impressive drama program, I watch many plays. Gradually it dawned that much fiction is driven by portraying conflicts that actually never happen in most lives. I mean family fights or blowups with friends in which longstanding resentments are aired, lanced, and resolved. I know, it’s drama. The theatre could scarcely exist without this convention.

Of course people do disagree and even fight, sure. They yell and sometimes throw things, I understand. But more often, people sublimate or seethe. Aren’t fights, when they happen, quick, a few words? Often harsh only in retrospect? And then years follow when nothing is fixed. But neither is anything fatally broken—as in a verbal brawl. The truth is, we’re a civilized species, with key defaults of repression and depression. We swallow pain to avoid worse pain.

You wouldn’t know this from many plays, movies, short stories, and novels. I imagine that this conflict flows from the fictionist’s inciting question, What if? Maybe s/he broods upon buried feelings to turn a human wish for healing into literary art. The result is what might happen if people would do what in fact they wisely avoid: use rage in pursuit of transcendence.

But people do rage in Gornick’s memoir!

![[Vivian Gornick.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1452798986i/17745439.jpg)

[Vivian Gornick.]

Boy, is this an irony. Gornick and her mother are stereotypes of an immigrant Jewish or perhaps Yiddish culture in which people pick at each other. At least her mother does. In response, mother and daughter often shout and even scream. As a repressed WASP, I envy the emotional venting. But not the obvious pain and insecurity the constant criticism creates. Oy vey!All the same, the ferocity in Fierce Attachments is different from fiction’s. It’s more intimate, more real. It’s less clear what it’s about, and the outcome is much less healing.

Most fiction isn’t Anna Karenina. It’s some guy wondering, What would’ve happened if Mama had poured a bottle of wine over Daddy’s head? I’m generalizing about fiction here. And not bashing it—my top ten books list might include eight novels. But as emotionally extreme as Gornick’s upbringing apparently was, her world is subtle compared with popular fiction’s.

I decided, quite reluctantly, that much of the appeal of Fierce Attachments is due to it being nonfiction. It probably wouldn’t be exciting enough as a novel, except maybe in the most rarified literary form. But as a memoir depicting the forces and especially the mother that forged the writer? Wow.

Memoir’s peculiar appeal

Hewing as much as possible to nonfiction’s promise to be nonfiction is important because that promise embodies a crucial aspect of nonfiction’s appeal. Someone like you or me is working hard to understand and convey her life. Since some of us are walking around doing that in our heads, it’s compelling to read someone’s shaped but real and real-time account of this task.

Memoir isn’t allowed to be boring just because “it happened.” And it won’t be, however quiet its surface events, if it is fulfilling its role as an instrument of inquiry and understanding. Those virtues also remove the taint of voyeurism in memoirs that depict trauma and severe dysfunction.

Memoir’s peculiar appeal lies not in its label of truth but the effort we sense someone making to arrive at deeply personal truth and honest self-portrayal. That’s the honesty in memoir—subjective truth and unsparing self-portrayal. I have thrown down a memoir in disgust for their lack. I honor Gornick’s for their presence.

Take my 2016 memoir challenge. Take your favorite memoir and try to read it as fiction. Very instructive.

The post Honesty in memoir 4.0 appeared first on Richard Gilbert.